Professional Documents

Culture Documents

100 Paganini, The Spectacular Virtuoso

100 Paganini, The Spectacular Virtuoso

Uploaded by

杨飞燕Copyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Fiona Apple-I KnowDocument5 pagesFiona Apple-I KnowZachary Pinkham40% (5)

- The Bass Guitar Resource BookDocument31 pagesThe Bass Guitar Resource Bookaron lay100% (32)

- Conversations With Iannis Xenakis Bálint András Varga PDFDocument266 pagesConversations With Iannis Xenakis Bálint András Varga PDFJean Luc Gehrenbeck100% (2)

- Final Project Advertising Shadow - ENEBDocument11 pagesFinal Project Advertising Shadow - ENEBYarey Sánchez AponteNo ratings yet

- Easy Music Quiz Questions & AnswersDocument2 pagesEasy Music Quiz Questions & Answerstiny6680% (5)

- Tuxedo Junction Brass QuintetDocument4 pagesTuxedo Junction Brass QuintetGabrielSerra60% (5)

- Nicolo Paganini: His Life and WorkFrom EverandNicolo Paganini: His Life and WorkRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Sentimental Medicine PDFDocument8 pagesSentimental Medicine PDF杨飞燕No ratings yet

- Tremolo and Octave Harmonica MethodDocument6 pagesTremolo and Octave Harmonica MethodJJAOsNo ratings yet

- Programa de Concierto Del Pianista Arthur Rubinstein 190Document7 pagesPrograma de Concierto Del Pianista Arthur Rubinstein 190Thai AnhNo ratings yet

- Rossini's The Barber of Seville: A Short Guide to a Great OperaFrom EverandRossini's The Barber of Seville: A Short Guide to a Great OperaNo ratings yet

- The Tales of Haunted Nights (Gothic Horror: Bulwer-Lytton-Series): Zanoni, A Strange Story, The Coming Race, Falkland, Zicci, The House and the Brain & The IncantationFrom EverandThe Tales of Haunted Nights (Gothic Horror: Bulwer-Lytton-Series): Zanoni, A Strange Story, The Coming Race, Falkland, Zicci, The House and the Brain & The IncantationNo ratings yet

- Julian Bream at 80Document4 pagesJulian Bream at 80Juan Pablo Honorato Brugere100% (6)

- The Greatest Gothich Novels of Edward Bulwer-Lytton: Zanoni, A Strange Story, The Coming Race, Falkland, Zicci, The House and the Brain & The IncantationFrom EverandThe Greatest Gothich Novels of Edward Bulwer-Lytton: Zanoni, A Strange Story, The Coming Race, Falkland, Zicci, The House and the Brain & The IncantationNo ratings yet

- Gothic Horror Classics: The Bulwer-Lytton Collection: Zanoni, A Strange Story, The Coming Race, Falkland, Zicci, The House and the Brain & The IncantationFrom EverandGothic Horror Classics: The Bulwer-Lytton Collection: Zanoni, A Strange Story, The Coming Race, Falkland, Zicci, The House and the Brain & The IncantationNo ratings yet

- The Boss of Taroomba: "The little musician had turned upon his tormentor like a knife"From EverandThe Boss of Taroomba: "The little musician had turned upon his tormentor like a knife"No ratings yet

- BeethovenDocument42 pagesBeethovenHlaching Mong Murruy100% (1)

- Chopin and Other Musical Essays by Finck, Henry Theophilus, 1854-1926Document87 pagesChopin and Other Musical Essays by Finck, Henry Theophilus, 1854-1926Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Anna Fedorova: Four FantasiesDocument13 pagesAnna Fedorova: Four FantasiesСапармырат КадыровNo ratings yet

- Franco DonatoniDocument6 pagesFranco DonatoniHermann90No ratings yet

- Hyoung Lok Choi (Booklet)Document10 pagesHyoung Lok Choi (Booklet)ᄋᄋNo ratings yet

- Secret Lives of Great Composers: What Your Teachers Never Told You about the World's Musical MastersFrom EverandSecret Lives of Great Composers: What Your Teachers Never Told You about the World's Musical MastersRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (22)

- Mozart Exsultate JubilateDocument9 pagesMozart Exsultate JubilateAhlfNo ratings yet

- BT Electric Forklift C4e400 450 500v Service Operator Manuals DiagramsDocument22 pagesBT Electric Forklift C4e400 450 500v Service Operator Manuals Diagramsjerrysmith120300tji100% (18)

- Paganini 2Document36 pagesPaganini 2Rodolfo Miguel Luján RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Chambers's Edinburgh Journal, No. 436volume 17, New Series, May 8, 1852 by VariousDocument35 pagesChambers's Edinburgh Journal, No. 436volume 17, New Series, May 8, 1852 by VariousGutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Puccini: The Illustrated Lives of the Great Composers.From EverandPuccini: The Illustrated Lives of the Great Composers.No ratings yet

- Cecile Licad's Chopin, Ms. Picazo's CecileDocument6 pagesCecile Licad's Chopin, Ms. Picazo's CecileClement AcevedoNo ratings yet

- The Spectacle of Nineteenth Century VirtuosityDocument9 pagesThe Spectacle of Nineteenth Century VirtuosityMiguel LópezNo ratings yet

- Soirée Rossiniana Cecilia Bartoli Mezzo-Soprano Sergio Ciomei Piano DonizettiDocument20 pagesSoirée Rossiniana Cecilia Bartoli Mezzo-Soprano Sergio Ciomei Piano DonizettishadowwyNo ratings yet

- Music of Romantic Period - 3rd Quarter (MUSIC 9)Document30 pagesMusic of Romantic Period - 3rd Quarter (MUSIC 9)Neth ManaliliNo ratings yet

- Bellman Chopin and His ImitatorsDocument14 pagesBellman Chopin and His ImitatorsKamila Stępień-Kutera100% (1)

- Discografia - Andrea BocelliDocument8 pagesDiscografia - Andrea BocelliBindea Marian0% (1)

- 106 Liszt, The All-Conquering PianistDocument3 pages106 Liszt, The All-Conquering Pianist杨飞燕No ratings yet

- Trio Khnopff ProgrammeDocument2 pagesTrio Khnopff ProgrammesimoncallaghanNo ratings yet

- St. Louis Symphony Extra - November 8, 2014Document16 pagesSt. Louis Symphony Extra - November 8, 2014St. Louis Public RadioNo ratings yet

- Sociology of OperaDocument10 pagesSociology of OperaMick PolNo ratings yet

- Excerpts From Jan Swafford: Beethoven: Anguish and TriumphDocument4 pagesExcerpts From Jan Swafford: Beethoven: Anguish and TriumphZoltán KovácsNo ratings yet

- Cosme Mcmoon Interview, 1990sDocument4 pagesCosme Mcmoon Interview, 1990sskNo ratings yet

- Paganini 2011Document2 pagesPaganini 2011Cristi AntonNo ratings yet

- Operas Every Child Should Know Descriptions of the Text and Music of Some of the Most Famous MasterpiecesFrom EverandOperas Every Child Should Know Descriptions of the Text and Music of Some of the Most Famous MasterpiecesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Iwona Kaminska-Bowlby, Pianist: in RecitalDocument6 pagesIwona Kaminska-Bowlby, Pianist: in RecitallevernNo ratings yet

- Review - Le Gazhikane Muzikante - Marius Kociejowski - EditedDocument5 pagesReview - Le Gazhikane Muzikante - Marius Kociejowski - Editedapi-293379298No ratings yet

- Art of Noises CentenaryDocument12 pagesArt of Noises CentenaryDean PowellNo ratings yet

- Karl Paulnack To The Boston Conservatory Freshman ClassDocument4 pagesKarl Paulnack To The Boston Conservatory Freshman ClassLiaomiffyNo ratings yet

- Entrevista John CoriglianoDocument12 pagesEntrevista John CoriglianoSaul PuenteNo ratings yet

- 106 Liszt, The All-Conquering PianistDocument3 pages106 Liszt, The All-Conquering Pianist杨飞燕No ratings yet

- RIPM User GuideDocument10 pagesRIPM User Guide杨飞燕No ratings yet

- M501 Music History SyllabusDocument8 pagesM501 Music History Syllabus杨飞燕No ratings yet

- Temple University Wind Symphony: Rehearsal Schedule: Week of September 24Document1 pageTemple University Wind Symphony: Rehearsal Schedule: Week of September 24杨飞燕No ratings yet

- Incontroverti: On A Waltz by Anton Diabelli, Op. 120 To Antonie Von Brentano, His "Immortal Beloved"Document8 pagesIncontroverti: On A Waltz by Anton Diabelli, Op. 120 To Antonie Von Brentano, His "Immortal Beloved"杨飞燕No ratings yet

- Assignment #1Document5 pagesAssignment #1杨飞燕No ratings yet

- High Hopes Chords by Panic! at The DiscoDocument4 pagesHigh Hopes Chords by Panic! at The DiscomilesNo ratings yet

- Picture Book Bill RichardsonDocument3 pagesPicture Book Bill Richardsonapi-508307805No ratings yet

- MECA Training 2Document41 pagesMECA Training 2rikyNo ratings yet

- Wonderful Tonight NewDocument2 pagesWonderful Tonight NewNorberto Vogel IINo ratings yet

- 08.0 PP 152 170 Liszts Piano Concerti A Lost TraditionDocument19 pages08.0 PP 152 170 Liszts Piano Concerti A Lost TraditionCobi AshkenaziNo ratings yet

- List (D) UnreleasedDocument11 pagesList (D) Unreleasedsieba sugul0% (1)

- Charlie Parker Jazz TheoryDocument15 pagesCharlie Parker Jazz Theorykris.ivanov.2004No ratings yet

- Music 10week 1Document17 pagesMusic 10week 1HARLEY L. TANNo ratings yet

- Grade 5 - Mapeh - Validation Examination 2022Document10 pagesGrade 5 - Mapeh - Validation Examination 2022Roselyn GutasNo ratings yet

- ENGL110 Grammar 12-3 - Like & Would LikeDocument16 pagesENGL110 Grammar 12-3 - Like & Would LikeESTEFANIA LOPEZ TORRESNo ratings yet

- Pedal Harp String Guide For Salvi and Lyon and HealyDocument1 pagePedal Harp String Guide For Salvi and Lyon and HealyHeidi DiederichNo ratings yet

- Handout 4 - Rectangle and StackDocument5 pagesHandout 4 - Rectangle and StackFernando AgostoNo ratings yet

- HOW DEEP IS YOUR LOVE CHORDS (Ver 5) by Bee Gees @Document7 pagesHOW DEEP IS YOUR LOVE CHORDS (Ver 5) by Bee Gees @Roberto CastilloNo ratings yet

- DLL - Mapeh 6 - Q3 - W10editDocument6 pagesDLL - Mapeh 6 - Q3 - W10editRiza GusteNo ratings yet

- Don Henley Q&ADocument24 pagesDon Henley Q&ALisa MielkeNo ratings yet

- The Art of Composition Vol 2Document6 pagesThe Art of Composition Vol 2Jan Domènech VayredaNo ratings yet

- Oli Herbert Level 2Document36 pagesOli Herbert Level 2BPG ServiceNo ratings yet

- 1a - Magic Train - Solo GuitarDocument3 pages1a - Magic Train - Solo GuitarЮлія ЧепеленкоNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan 280Document20 pagesLesson Plan 280api-584426874No ratings yet

- Dashing White Sergeant Tune and Chords Concert - pdf899333474Document1 pageDashing White Sergeant Tune and Chords Concert - pdf899333474Phil BruceNo ratings yet

- This Place Hotel Double BassDocument2 pagesThis Place Hotel Double BassJosue Umaña CecilianoNo ratings yet

- Music Theory Grade 4 Sample Paper 200825 PDFDocument11 pagesMusic Theory Grade 4 Sample Paper 200825 PDFjackcan501No ratings yet

- New Headway Preintermediate Unit 7 17527Document3 pagesNew Headway Preintermediate Unit 7 17527Zedd ConstantineNo ratings yet

- Présentation1Document13 pagesPrésentation1alias prkNo ratings yet

100 Paganini, The Spectacular Virtuoso

100 Paganini, The Spectacular Virtuoso

Uploaded by

杨飞燕Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

100 Paganini, The Spectacular Virtuoso

100 Paganini, The Spectacular Virtuoso

Uploaded by

杨飞燕Copyright:

Available Formats

Paganini, the Spectacular Virtuoso 289

replied that he thanked the Princess very much but she was not to bother herself in the

least about him, he was quite used to not being noticed, indeed he was really very glad

of it, as it caused him less embarrassment.

Many people thought, and perhaps still think, that Schubert was a dull fellow with

no feeling, but those who knew him better know how deeply his creations affected him

and that they were conceived in suffering. Anyone who has seen him of a morning

occupied with composition, aglow, with his eyes shining and even his speech changed,

like a sleepwalker, will never forget the impression. And how could he have written

these songs without being stirred to the depths by them! In the afternoon he was

admittedly another person, but he was gentle and deeply sensitive, only he did not like

to show his feelings but preferred to keep them to himself.

Schubert did not get the recognition he deserved in Vienna. The great majority of

people remained, and still remain, uninterested.

Nor are his songs suited to the concert hall or stage. The listener, too, must have a

feeling for the poem and enjoy the lovely song together with it; in a word, the public

must he quite a different one from that which fills the theatres and concert halls.

When publishers told him that people found the accompaniment to his songs too

hard and the keys often so difficult, and that, in his own interest, he ought to pay

attention to this, he always replied that he could not write differently and that anyone

who could not play his compositions should leave them alone, and a person to whom

one key was not as easy as another was, anyhow, not in the least musical.

Schubert’s music must either be performed well or not at all.

His incredible wealth of melody remains a treasure for all time, and musicians yet

unborn will gather spoils from this rich mine. In the span of time he was vouchsafed he

wrote 600 songs, of which no one is like another, so rich was he in melodies.

Schubert was an affectionate son and brother, and a loyal friend. He was a kind,

generous, good man.

May he rest in peace, and thanks be to him for having beautified the lives of his

friends by his creations!

O. E. Deutsch (ed.), Schubert: Memoirs by his Friends (London: A. & C. Black, 1958), 126–27, 127–28, 133,

134, 135, 140–41. Reprinted by permission.

100

Paganini, the Spectacular Virtuoso

A “virtuoso” was, originally, a highly accomplished musician, but by the nineteenth

century the term had become restricted to performers, both vocal and instrumental,

whose technical accomplishments were so pronounced as to dazzle the public.

Virtuoso singers, of course, had been the mainstay of Italian opera almost from its

beginnings. Virtuoso instrumentalists, on the other hand, really came into their own in

the nineteenth century, with the spread of public concerts designed to cater to the vast

new middle-class audiences. Niccolò Paganini (1782–1840), the greatest violin vir-

tuoso of the century, emerged from his native Italy in 1828. Beginning in Vienna,

Copyright 2008 Thomson Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

290 The Later Nineteenth Century

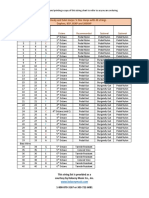

The Debut of Paganini in London. Friday, 3 June 1831, at the King’s Theatre.

(Drawing by D. Maclise.) ©Victoria and Albert Museum / Art Resource, NY.

where he created a sensation, he eventually took all of Europe by storm, leaving his

audiences openmouthed at the unprecedented effects he produced on his instrument.

“Unfortunately,” wrote the Vienna correspondent of The Harmonicon, “the worst

parts of his performance seemed to call forth the loudest applause, such, for instance,

as his imitation of bells, his laborious performance upon a single string, &c., all of

which, in the eyes of the true amateur, savour more of charlatanism than of the

legitimate objects of art.” The demonic command, however, with which Paganini

summoned forth whatever he wished from his violin had an enormous impact on the

Copyright 2008 Thomson Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

Paganini, the Spectacular Virtuoso 291

imagination of some young composers who were soon to make a name for themselves.

“Paganini,” wrote Schumann in 1832, “represents the turning-point of virtuosity.” And

Liszt, in a letter of the same year, exclaimed: “What a man, what a violinist, what an

artist! God, what sufferings, what misery, what tortures in those four strings! And his

expressiveness, his phrasing, his soul!!” Leigh Hunt (see p. 286), writing as theater

critic for The Tatler in London, presents a vivid, admirably balanced picture of a

typical Paganini concert, seen as both a musical and social phenomenon.

June 23, 1831 King’s Theatre

Signor Paganini favoured the public with his “fifth and last concert at this theatre,”

last night, but not, it seems, with his fifth and last appearance; for he is to play this

evening for the benefit of [the bass singer] Lablache, besides the four other perfor-

mances, we suppose, which he is to be prevailed upon to bestow upon us, and the

forty elsewhere. Well: the public are accustomed to these managerial tricks, and

ought to be prepared for them; which does not seem to have been the case with

some persons last night, by their hissing at the commencement of the benefit.

Besides, Paganini is fine enough to make the public wish to hear him again and

again, at some little expence to the perfection of his morale. Whether he would not

be finer still if his proceedings were as straight-forward as his bow is a question of

refinement, which it may be hard to urge in a matter of violin-playing.

Let us not belie the effect however which this extraordinary player had upon us

last night. To begin with the beginning, he had a magnificent house. We thought at

first we were literally going to hear him, without seeing his face; for the house was

crammed at so early an hour that, on entering it, we found ourselves fixed on the

lowest of the pit stairs. It was amusing to see the persons who carne in after us. Some,

as they cast up their eyes, gaped amazement at the huge mass of faces presented in all

quarters of the house; others looked angry; others ashamed and cast a glance around

them to see what was thought of them; some gallantly smiled, and resolved to make

the best of it. One man exclaimed, with unsophisticated astonishment, “Christ

Jesus!” and an Italian whispered in a half execrating tone, “Oh, Dio!”

Meantime we heard some interesting conversation around us. We had been

told, as a striking instance of the effect that Paganini has produced upon the English

musical world, that one eminent musician declared he could not sleep the first night

of his performance for thinking of him, but that he got up and walked about his

room. A gentleman present last night was telling his friends that another celebrated

player swore that he would have given a thousand guineas to keep the Italian out of

the country, he had put everybody at such an immeasurable distance. These candid

confessions, it seems, are made in perfect good-humour, and therefore do honour

to the gentlemen concerned. Envy is lost in admiration.

The performances commenced with Haydn’s beautiful symphony, No. 9 [i.e.,

no. 102], the fine, touching exordium of which, full of a kind of hushing meaning,

appeared admirably adapted to be the harbinger of the evening’s wonder. A duet

between [the singers] Santini and Curioni followed; and then, after a due interval,

came in Signor Paganini, and “brought the house down” with applause.

As it was the first time we had seen the great player, except in the criticisms of

our musical friends, which had rendered us doubly curious, we looked up with

Copyright 2008 Thomson Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

292 The Later Nineteenth Century

interest at him from our abysm in the pit. A lucky interval between a gentleman’s

head and a lady’s bonnet favoured our endeavour, and there we beheld the long, pale

face of the musical marvel, hung, as it were, in the light, and looking as strange as

need be. He made divers uncouth obeisances, and then put himself in a masterly

attitude for his work, his manner being as firm and full of conscious power when he

puts the bow to the instrument as it is otherwise when he is not playing. We thought

he did not look so old as he is said to be; but he is long-faced and haggard, with

strongly-marked prominent features, wears his black hair flowing on his neck like an

enthusiast, has a coat of ancient cut which astonishes Fop’s Alley; in short, is very like

the picture of him in the shops. He is like a great old boy, who has done nothing but

play the violin all his life, and knows as much about that as he does little of conven-

tional manners. His face at the same time has much less expression than might be

looked for. At first it seemed little better than a mask; with a fastidious, dreary

expression, as if inclined to despise his music and go to sleep. And such was his

countenance for a great part of the evening. His fervour was in his hands and bow.

Towards the close of the performances, he waxed more enthusiastic in appearance,

gave way to some uncouth bodily movement from side to side, and seemed to be

getting into his violin. Occasionally also he put back his hair. When he makes his

acknowledgments, he bows like a camel, and grins like a goblin or a mountain-goat.

His playing is indeed marvellous. What other players can do well, he does a

hundred times better. We never heard such playing before; nor had we imagined it.

His bow perfectly talks. It remonstrates, supplicates, answers, holds a dialogue. It

would be the easiest thing in the world to put words to his music. We are sure that

with a given subject, or even without it, Paganini’s best playing could be construed

into discourse by any imaginative person.

Last night he began a composition of his own (very good, by the way)—an

Allegro Maestoso movement (majestically cheerful) with singular force and preci-

sion. Precision is not the proper word; it was a sort of peremptoriness and dash. He

did not put his bow to the strings, nor lay it upon them; he struck them, as you

might imagine a Greek to have done when he used his plectrum, and “smote the

sounding shell.” He then fell into a tender strain, till the strings, when he touched

them, appeared to shiver with pleasure. Then he gave us a sort of minute warbling,

as if half a dozen humming birds were singing at the tops of their voices, the

highest notes sometimes leaping off and shivering like sprinkles of water; then he

descended with wonderful force and gravity into the bass; then he would com-

mence a strain of earnest feeling or entreaty, with notes of the greatest solidity, yet

full of trembling emotion; and then again he would leap to a height beyond all

height, with notes of desperate minuteness, then flash down in a set of headlong

harmonies, sharp and brilliant as the edges of swords; then warble again with incon-

ceivable beauty and remoteness, as if he was a ventriloquizing-bird; and finally,

besides his usual wonderful staccatos in ordinary, he would suddenly throw hand-

fuls, as it were, of staccatoed notes, in distinct and repeated showers over his violin,

small and pungent as the tips of pins.

In a word, we never heard anything like any part of his performance, much less

the least marvel we have been speaking of. The people sit astonished, venting

themselves in whispers of “Wonderful!”—“Good God!”—and other unusual symp-

toms of English amazement; and when the applause comes, some of them take an

opportunity of laughing, out of pure inability to express their feelings otherwise.

Copyright 2008 Thomson Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

The Virtuoso Conductor 293

June 25, 1831

Our wizard’s Allegro Maestoso was succeeded by an “Adagio Flebile con Senti-

mento”—a composition with a very “particular fellow” of a title, by which we are

to understand a strain of pathos amounting to the lachrymose, and disclosing a

deep perception of the delicacy of that matter. If we are inclined to doubt the

perfection of Signor Paganini’s playing it would be upon this point. He has a great

deal more feeling than is usually shewn by players of extreme execution: his

supplication in particular is admirable; he is fervent and imploring; you would

think his violin was on its knees; the very first note he draws, in movements of this

character, is the fullest, the gravest, the most forcible, and the most impassioned we

ever heard; it is wonderfully in earnest. And yet, though there is a feeling of this

kind throughout, and we never heard notes so touching accompanied with such

admirable execution, we cannot help thinking that we miss, both in the style and in

the composition, that perfection of simplicity, and of unconsciousness of every-

thing but the object of its passion or admiration, which is perhaps incompatible

with these exhibitions of art.

Upon the whole, our experience of the playing of this wonderful person has

not only added to our stock of extraordinary and delightful recollections, but it has

done our memories another great good, in opening afresh the world of ancient

Greek music and convincing us of the truth of all that is said of its marvellous effects.

To hear Paganini, and to see him playing on that bit of wood with a bit of catgut, is

to convince us that the Greeks might really have done the wonders attributed to

them with their shells and quills. What if he is but a poor player to the least of them?

For now that we see what such instruments can do, there is no knowing how much

they can do beyond it.

But even after what we have heard, how are we to endure hereafter our old

violins and their players? How can we consent to hear them? How crude they will

sound, how uninformed, how like a cheat! When the Italian goes away, violin-

playing goes with him, unless some disciple of his should arise among us and detain

a semblance of his instrument. As it is, the most masterly performers, hitherto so

accounted, must consent to begin again, and be little boys in his school.

L. H. Houtchens and C. W. Houtchens (eds.), Leigh Hunt’s Dramatic Criticism: 1808–1831 (New York:

Columbia University Press, 1949), 270–74, 275–76.

101

The Virtuoso Conductor

Conditions of orchestral execution, in the early nineteenth century often deplorable

(see pp. 274–75), greatly improved under pressure of the ever-increasing demands

made by composers of complex and colorful Romantic scores. A necessary part of that

improvement was the introduction of orchestral conducting in the modern sense. This

Copyright 2008 Thomson Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

You might also like

- Fiona Apple-I KnowDocument5 pagesFiona Apple-I KnowZachary Pinkham40% (5)

- The Bass Guitar Resource BookDocument31 pagesThe Bass Guitar Resource Bookaron lay100% (32)

- Conversations With Iannis Xenakis Bálint András Varga PDFDocument266 pagesConversations With Iannis Xenakis Bálint András Varga PDFJean Luc Gehrenbeck100% (2)

- Final Project Advertising Shadow - ENEBDocument11 pagesFinal Project Advertising Shadow - ENEBYarey Sánchez AponteNo ratings yet

- Easy Music Quiz Questions & AnswersDocument2 pagesEasy Music Quiz Questions & Answerstiny6680% (5)

- Tuxedo Junction Brass QuintetDocument4 pagesTuxedo Junction Brass QuintetGabrielSerra60% (5)

- Nicolo Paganini: His Life and WorkFrom EverandNicolo Paganini: His Life and WorkRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Sentimental Medicine PDFDocument8 pagesSentimental Medicine PDF杨飞燕No ratings yet

- Tremolo and Octave Harmonica MethodDocument6 pagesTremolo and Octave Harmonica MethodJJAOsNo ratings yet

- Programa de Concierto Del Pianista Arthur Rubinstein 190Document7 pagesPrograma de Concierto Del Pianista Arthur Rubinstein 190Thai AnhNo ratings yet

- Rossini's The Barber of Seville: A Short Guide to a Great OperaFrom EverandRossini's The Barber of Seville: A Short Guide to a Great OperaNo ratings yet

- The Tales of Haunted Nights (Gothic Horror: Bulwer-Lytton-Series): Zanoni, A Strange Story, The Coming Race, Falkland, Zicci, The House and the Brain & The IncantationFrom EverandThe Tales of Haunted Nights (Gothic Horror: Bulwer-Lytton-Series): Zanoni, A Strange Story, The Coming Race, Falkland, Zicci, The House and the Brain & The IncantationNo ratings yet

- Julian Bream at 80Document4 pagesJulian Bream at 80Juan Pablo Honorato Brugere100% (6)

- The Greatest Gothich Novels of Edward Bulwer-Lytton: Zanoni, A Strange Story, The Coming Race, Falkland, Zicci, The House and the Brain & The IncantationFrom EverandThe Greatest Gothich Novels of Edward Bulwer-Lytton: Zanoni, A Strange Story, The Coming Race, Falkland, Zicci, The House and the Brain & The IncantationNo ratings yet

- Gothic Horror Classics: The Bulwer-Lytton Collection: Zanoni, A Strange Story, The Coming Race, Falkland, Zicci, The House and the Brain & The IncantationFrom EverandGothic Horror Classics: The Bulwer-Lytton Collection: Zanoni, A Strange Story, The Coming Race, Falkland, Zicci, The House and the Brain & The IncantationNo ratings yet

- The Boss of Taroomba: "The little musician had turned upon his tormentor like a knife"From EverandThe Boss of Taroomba: "The little musician had turned upon his tormentor like a knife"No ratings yet

- BeethovenDocument42 pagesBeethovenHlaching Mong Murruy100% (1)

- Chopin and Other Musical Essays by Finck, Henry Theophilus, 1854-1926Document87 pagesChopin and Other Musical Essays by Finck, Henry Theophilus, 1854-1926Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Anna Fedorova: Four FantasiesDocument13 pagesAnna Fedorova: Four FantasiesСапармырат КадыровNo ratings yet

- Franco DonatoniDocument6 pagesFranco DonatoniHermann90No ratings yet

- Hyoung Lok Choi (Booklet)Document10 pagesHyoung Lok Choi (Booklet)ᄋᄋNo ratings yet

- Secret Lives of Great Composers: What Your Teachers Never Told You about the World's Musical MastersFrom EverandSecret Lives of Great Composers: What Your Teachers Never Told You about the World's Musical MastersRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (22)

- Mozart Exsultate JubilateDocument9 pagesMozart Exsultate JubilateAhlfNo ratings yet

- BT Electric Forklift C4e400 450 500v Service Operator Manuals DiagramsDocument22 pagesBT Electric Forklift C4e400 450 500v Service Operator Manuals Diagramsjerrysmith120300tji100% (18)

- Paganini 2Document36 pagesPaganini 2Rodolfo Miguel Luján RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Chambers's Edinburgh Journal, No. 436volume 17, New Series, May 8, 1852 by VariousDocument35 pagesChambers's Edinburgh Journal, No. 436volume 17, New Series, May 8, 1852 by VariousGutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Puccini: The Illustrated Lives of the Great Composers.From EverandPuccini: The Illustrated Lives of the Great Composers.No ratings yet

- Cecile Licad's Chopin, Ms. Picazo's CecileDocument6 pagesCecile Licad's Chopin, Ms. Picazo's CecileClement AcevedoNo ratings yet

- The Spectacle of Nineteenth Century VirtuosityDocument9 pagesThe Spectacle of Nineteenth Century VirtuosityMiguel LópezNo ratings yet

- Soirée Rossiniana Cecilia Bartoli Mezzo-Soprano Sergio Ciomei Piano DonizettiDocument20 pagesSoirée Rossiniana Cecilia Bartoli Mezzo-Soprano Sergio Ciomei Piano DonizettishadowwyNo ratings yet

- Music of Romantic Period - 3rd Quarter (MUSIC 9)Document30 pagesMusic of Romantic Period - 3rd Quarter (MUSIC 9)Neth ManaliliNo ratings yet

- Bellman Chopin and His ImitatorsDocument14 pagesBellman Chopin and His ImitatorsKamila Stępień-Kutera100% (1)

- Discografia - Andrea BocelliDocument8 pagesDiscografia - Andrea BocelliBindea Marian0% (1)

- 106 Liszt, The All-Conquering PianistDocument3 pages106 Liszt, The All-Conquering Pianist杨飞燕No ratings yet

- Trio Khnopff ProgrammeDocument2 pagesTrio Khnopff ProgrammesimoncallaghanNo ratings yet

- St. Louis Symphony Extra - November 8, 2014Document16 pagesSt. Louis Symphony Extra - November 8, 2014St. Louis Public RadioNo ratings yet

- Sociology of OperaDocument10 pagesSociology of OperaMick PolNo ratings yet

- Excerpts From Jan Swafford: Beethoven: Anguish and TriumphDocument4 pagesExcerpts From Jan Swafford: Beethoven: Anguish and TriumphZoltán KovácsNo ratings yet

- Cosme Mcmoon Interview, 1990sDocument4 pagesCosme Mcmoon Interview, 1990sskNo ratings yet

- Paganini 2011Document2 pagesPaganini 2011Cristi AntonNo ratings yet

- Operas Every Child Should Know Descriptions of the Text and Music of Some of the Most Famous MasterpiecesFrom EverandOperas Every Child Should Know Descriptions of the Text and Music of Some of the Most Famous MasterpiecesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Iwona Kaminska-Bowlby, Pianist: in RecitalDocument6 pagesIwona Kaminska-Bowlby, Pianist: in RecitallevernNo ratings yet

- Review - Le Gazhikane Muzikante - Marius Kociejowski - EditedDocument5 pagesReview - Le Gazhikane Muzikante - Marius Kociejowski - Editedapi-293379298No ratings yet

- Art of Noises CentenaryDocument12 pagesArt of Noises CentenaryDean PowellNo ratings yet

- Karl Paulnack To The Boston Conservatory Freshman ClassDocument4 pagesKarl Paulnack To The Boston Conservatory Freshman ClassLiaomiffyNo ratings yet

- Entrevista John CoriglianoDocument12 pagesEntrevista John CoriglianoSaul PuenteNo ratings yet

- 106 Liszt, The All-Conquering PianistDocument3 pages106 Liszt, The All-Conquering Pianist杨飞燕No ratings yet

- RIPM User GuideDocument10 pagesRIPM User Guide杨飞燕No ratings yet

- M501 Music History SyllabusDocument8 pagesM501 Music History Syllabus杨飞燕No ratings yet

- Temple University Wind Symphony: Rehearsal Schedule: Week of September 24Document1 pageTemple University Wind Symphony: Rehearsal Schedule: Week of September 24杨飞燕No ratings yet

- Incontroverti: On A Waltz by Anton Diabelli, Op. 120 To Antonie Von Brentano, His "Immortal Beloved"Document8 pagesIncontroverti: On A Waltz by Anton Diabelli, Op. 120 To Antonie Von Brentano, His "Immortal Beloved"杨飞燕No ratings yet

- Assignment #1Document5 pagesAssignment #1杨飞燕No ratings yet

- High Hopes Chords by Panic! at The DiscoDocument4 pagesHigh Hopes Chords by Panic! at The DiscomilesNo ratings yet

- Picture Book Bill RichardsonDocument3 pagesPicture Book Bill Richardsonapi-508307805No ratings yet

- MECA Training 2Document41 pagesMECA Training 2rikyNo ratings yet

- Wonderful Tonight NewDocument2 pagesWonderful Tonight NewNorberto Vogel IINo ratings yet

- 08.0 PP 152 170 Liszts Piano Concerti A Lost TraditionDocument19 pages08.0 PP 152 170 Liszts Piano Concerti A Lost TraditionCobi AshkenaziNo ratings yet

- List (D) UnreleasedDocument11 pagesList (D) Unreleasedsieba sugul0% (1)

- Charlie Parker Jazz TheoryDocument15 pagesCharlie Parker Jazz Theorykris.ivanov.2004No ratings yet

- Music 10week 1Document17 pagesMusic 10week 1HARLEY L. TANNo ratings yet

- Grade 5 - Mapeh - Validation Examination 2022Document10 pagesGrade 5 - Mapeh - Validation Examination 2022Roselyn GutasNo ratings yet

- ENGL110 Grammar 12-3 - Like & Would LikeDocument16 pagesENGL110 Grammar 12-3 - Like & Would LikeESTEFANIA LOPEZ TORRESNo ratings yet

- Pedal Harp String Guide For Salvi and Lyon and HealyDocument1 pagePedal Harp String Guide For Salvi and Lyon and HealyHeidi DiederichNo ratings yet

- Handout 4 - Rectangle and StackDocument5 pagesHandout 4 - Rectangle and StackFernando AgostoNo ratings yet

- HOW DEEP IS YOUR LOVE CHORDS (Ver 5) by Bee Gees @Document7 pagesHOW DEEP IS YOUR LOVE CHORDS (Ver 5) by Bee Gees @Roberto CastilloNo ratings yet

- DLL - Mapeh 6 - Q3 - W10editDocument6 pagesDLL - Mapeh 6 - Q3 - W10editRiza GusteNo ratings yet

- Don Henley Q&ADocument24 pagesDon Henley Q&ALisa MielkeNo ratings yet

- The Art of Composition Vol 2Document6 pagesThe Art of Composition Vol 2Jan Domènech VayredaNo ratings yet

- Oli Herbert Level 2Document36 pagesOli Herbert Level 2BPG ServiceNo ratings yet

- 1a - Magic Train - Solo GuitarDocument3 pages1a - Magic Train - Solo GuitarЮлія ЧепеленкоNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan 280Document20 pagesLesson Plan 280api-584426874No ratings yet

- Dashing White Sergeant Tune and Chords Concert - pdf899333474Document1 pageDashing White Sergeant Tune and Chords Concert - pdf899333474Phil BruceNo ratings yet

- This Place Hotel Double BassDocument2 pagesThis Place Hotel Double BassJosue Umaña CecilianoNo ratings yet

- Music Theory Grade 4 Sample Paper 200825 PDFDocument11 pagesMusic Theory Grade 4 Sample Paper 200825 PDFjackcan501No ratings yet

- New Headway Preintermediate Unit 7 17527Document3 pagesNew Headway Preintermediate Unit 7 17527Zedd ConstantineNo ratings yet

- Présentation1Document13 pagesPrésentation1alias prkNo ratings yet