Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Manika, Kanika-Petitioner

Manika, Kanika-Petitioner

Uploaded by

manikaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Manika, Kanika-Petitioner

Manika, Kanika-Petitioner

Uploaded by

manikaCopyright:

Available Formats

THE 2ND LEGAL INSIDER, MEMORIAL WRITING COMPETITION, 2020

THE 2ND LEGAL INSIDER, MEMORIAL WRITING COMPETITION, 2020

BEFORE THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIANA

SLP NO. ………… OF 2016

IN THE MATTER OF:

RANSOM AND ORS. PETITIONER

V.

UNION OF INDIANA .. RESPONDENT

CLUBBED WITH

WP(C) NO. ………… OF 2016

ZIO FOUNDATION .. PETITIONER

V.

UNION OF INDIANA .. RESPONDENT

ON SUBMISSION TO THE REGISTRY OF THE COURT

OF THE HON’BLE SUPREME COURT OF INDIANA

MEMORIAL ON BEHALF OF THE PETITIONER

[0 | P a g e ]

MEMORIAL FOR THE PETITIONER

THE 2ND LEGAL INSIDER, MEMORIAL WRITING COMPETITION, 2020

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ......................................................................................................... 2

INDEX OF AUTHORITIES........................................................................................................... 3

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION............................................................................................... 9

STATEMENT OF FACTS ........................................................................................................... 10

ISSUES RAISED .......................................................................................................................... 11

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENTS .................................................................................................. 12

ARGUMENTS ADVANCED ......................................................................................................... i

I. THAT THE JUVENILE JUSTICE (CARE AND PROTECTION OF CHILDREN) ACT,

2014 IS NOT CONSTITUTIONAL ............................................................................................ i

II. THAT THE HIGH COURT AND SESSION’S COURT WERE NOT JUSTIFIED IN

REJECTING THE TEST FOR DETERMINATION OF RANSOM’S AGE .......................... vii

III. THAT PETER SHOULD BE ACQUIITED OF ALL THE CHARGES LEVIED

AGAINST HIM........................................................................................................................... x

PRAYER .................................................................................................................................... xviii

[1 | P a g e ]

MEMORIAL FOR THE PETITIONER

THE 2ND LEGAL INSIDER, MEMORIAL WRITING COMPETITION, 2020

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

¶ Paragraph

§ Section

AIR All India Reporter

Art. Article

Cri Criminal

GOI Government Of Indiana

Hon’ble Honourable

IEA Indian Evidence Act

i.e That is

IPC Indian Penal Code

J. Justice

JJ. Juvenile Justice

NCRB National Crime Research Bureau

Ors. Others

POCSO Protection of Children from Sexual Offences

r/w Read with

SC Supreme Court

SCC Supreme Court Cases

v. Versus

Yrs. Years

[2 | P a g e ]

MEMORIAL FOR THE PETITIONER

THE 2ND LEGAL INSIDER, MEMORIAL WRITING COMPETITION, 2020

INDEX OF AUTHORITIES

CASES

S.NO. CASE LAWS CITATION PAGE

NUMBER

1. Abdul Sayeed vs State Of M.P (2010) 10 SCC 259 xiv

2. Abuzar Hussain v. State of West Bengal (2012) 10 SCC 489 iv

3. Abdulwahab Abdulmajid Baloch v. State (2009) 11 SCC 625 xiii

of Gujarat

4. Aftab Ahamd Anasari v. State of 2010 2 SCC 583 xiv

Uttaranchal,

5. Akbar Sheikh (2009) 7 SCC 415 ix

6. A Mohnam v. State of Kerela 1990 Supp SCC 66 xii

7. Arnit Das v. State of Bihar (2000) 5 SCC 488 x

8. Ashok Basak v. State of Maharashtra (2010) 10 SCC 660 xii

9. Ashwani Kumar Saxena v. State of M.P (2012) 9 SCC 750 ix

10. Atlas Cycle Industries Ltd. v. State Of AIR 1979 SC 1149 ix

Haryana

11. Avishek Goenka v. Union of India (2012) 5 SCC 321 iv

12. Balco Employees Union v. Union of (2002) 2 SCC 333 i

India

13. Bangalore Wollen, Cotton and Silk AIR 1962 SC 1263 i

Mills, Co. Ltd. v. Corporation. of City of

Bangalore

14. Bhim Singh v. State of Uttrakhand (2015) 4 SCC 739 xv

[3 | P a g e ]

MEMORIAL FOR THE PETITIONER

THE 2ND LEGAL INSIDER, MEMORIAL WRITING COMPETITION, 2020

INDEX OF AUTHORITIES

15. Bikash Bora v. State of Assam (2019) 4 SCC 280 xiii

16. Bikramaditya Singh v. State of Bihar (2013) 2 SCC (Cri) 169 xii

17. Bishnupada Sarkar v. State of West AIR 2012 SC 2248 xii

Bengal

18. C. Chenga Reddy v State of AP (1996) 10 SCC 193 xv

19. Deepak v. State of Haryana (2015) 4 SCC 762 xiii

20. Essa v. State of Maharashtra 2013 (4) SCALE 1 iv

21. Gulam Hossain v. State of WB (2012) 10 SCC 489 ix

22. Gunga v. State of Rajasthan (2015) 2 SCC 775 ix

23. Hanumant v. State of M.P AIR 1952 SC 343 xv

24. Hari Vishnu Kamath v. Ahmad Ishaque AIR 1955 SC 233 viii

25. Hukam v state AIR 1977 SC 1063 xv

26. Independent Thought v. Union of India AIR 2017 SC 4904 iv

27. Jai Prakash Tiwari v. State of U.P (2016) 97 AIICC 592 ix

28. Jitendra Ram v. State of Jharkhand (2006) 9 SCC 428 ix

29. Jitendra Singh (2010) 13 SCC 523 ix

30. Javed Alam v. State of Chhattisgarh (2009) 6 SCC 450 xvi

31. Kartar Singh and Ujagar Singh v. Delhi (1979) 2 SCC 675 viii

Administration

32. Khalil Chishti v. State of Rajasthan (2013) 2 SCC 541 xi

33. Mal Singh v. Union of India and Ors. (1980) 2 SCC 684 viii

34. Manjula Krippendorf v. State (Govt. of AIR 2017 SC 3457 iv

NCT of Delhi) and Ors

35. Mano Dutt v. State of Uttar Pradesh (2012) 4 SCC 79 xii

36. M. Nagaraj v. Union of India AIR 2007 SC 71 iii

[4 | P a g e ]

MEMORIAL FOR THE PETITIONER

THE 2ND LEGAL INSIDER, MEMORIAL WRITING COMPETITION, 2020

INDEX OF AUTHORITIES

37. Mofil Khan and Anr. v. State of (2015) 1 SCC 67 iv

Jharkhand,

38. Mrinal Das v. State of Tripura (2011) 9 SCC 479 xiv

39. Nachimuthu v state of Tamil Nadu (2011) 14 SCC 441 xi

40. Nand Kishore v. State of Madhya (2011) 12 SCC 120 xi

Pradesh

.41. Nathu Singh and Ors. v. Union of India (1980) 2 SCC 675 viii

and Another

42. Nash v. State of Madhya Pradesh AIR 1953 SC 420 xiii

43. Om Prakash v. State of Rajasthan and (2012) 5 SCC 201 ix

Ors.

.44. Padaala Veera Reddy v. State of A.P AIR 1990 SC 79 xv

45. Parichat v. state of Madhya Pradesh AIR 1972 SC 535 xi

46. Pawan, (2009) 15 SCC 259 ix

47. PT Rajan v. TPM Sahir, AIR 2003 SC 4603 viii

48. Raghbir Chand v. State of Punjab (2013) 12 SCC 294 xvi

49. Rajindra Chandra v. State of (2002) 2 SCC 287 ix

Chhattisgarh and Anr.

50. Rajesh Rai v. State of Sikkim 2002 Cr.L.J. 1385 at P. xv

1390(Sikkim)

51. Raju Kumar v. State of Haryana (2010) 3 SCC 235 x

52. Ramdeo Chauhan v. State of Assam (Crl.) 4 of 2000 ix

53. Ram Jag v. State of Uttar Pradesh AIR 1974 SC 606 xi

54. Ramuthai v. State (2011) 13 SCC 212 xi

55. Ranganath Sharma v. Satendra Sharma (2009) 1 SCC (Cr.) 415 xi

[5 | P a g e ]

MEMORIAL FOR THE PETITIONER

THE 2ND LEGAL INSIDER, MEMORIAL WRITING COMPETITION, 2020

INDEX OF AUTHORITIES

56. R.D Upadhyay v. State of A.P and Ors. AIR 2006 SC 1946 iii

57. Reena Banerjee and Anr. v. Govt. (NCT (2015) 11 SCC 725 iv

of Delhi) and Ors.

58. Rewa Ram v. State of Madhya Pradesh (1978) Cr.L.J. 858 xiv

59. Roop Chand Adlakha v. DDA 1989 Supp (1) SCC 116 iii

60. RK Garg v Union Of India AIR 1981 SC 2138 iii

61. Salil Bali v Union of India (2013) 7 SCC 705 iii

62. Sainik Motors v. State of Rajasthan AIR 1961 SC 1480 viii

63. Sampurna Behura v. Union of India (2018) 4 SCC 433 iv

(UOI) and Ors.

64. Sarvesh Narain Shukla v. Daroga Singh (2007) 13 SCC 360 xiv

and Ors.,

65. Satto v. State of UP (1979) 2 SCC 628 ii

66. Selvam v. State of Tamil Nadu (2012) 10 SCC 402 xi

67.68. Shankarlal v. State of Rajasthan (2004) 10 SCC 632 xiv

69. Sharad Birdichand Sarda v. State of AIR 1984 SC 1682 xv

Maharashtra

70. Sher Singh and Another v. State of (1980) 2 SCC 696 viii

Punjab and Another

71. Shweta Gulati v. State (NCT of Delhi) (2004) 89 SCC 654 x

72. Solanki Chimanbhai Ukabhai v. State of AIR 1983 SC 484 xiv

Gujarat,

73. Sri Mahadeb Jiew and Anr. v. Dr. B.B AIR 1951 Cal 563 iv

Sen

74. State of Andhra Pradesh v. IBS Prasad AIR 1970 SC 648 xv

Rao

75. State of Maharashtra v. Goraksha (2011) 7 SCC 437 (¶27) xv

Ambaji Adsul

[6 | P a g e ]

MEMORIAL FOR THE PETITIONER

THE 2ND LEGAL INSIDER, MEMORIAL WRITING COMPETITION, 2020

INDEX OF AUTHORITIES

76. State of Mysore v. Venappasetty, 1973 CrLJ 1568. x

77. State of Rajasthan v. Manoj Kumar 138 AIC 261 (SC) xii

78. State of Rajasthan v. Tej Ram. (1999) 3 SCC 507 xv

79. State of Tamil Nadu v. Shyam Sunder (2011) 8 SCC 737 iii

80. State of U.P. v. Babu Ram AIR 1961 SC 751 viii

81. State of Uttar Pradesh v. Munni Ram (2010) 14 SCC 364 xiv

82. State of Uttar Pradesh v. Rajvir (2007) 15 SCC 545 xiii

83. State of Uttar Pradesh v Satish (2005) 3 SCC 114 xv

84. Subedar v. State of Uttar Pradesh. AIR 1971 SC 125 xvi

85. Suchita Srivastava and Anr. v. (2009) 9 SCC 1 iv

Chandigarh Administration

86. Sunil Batra v. Union of India and Ors. (1982) 2 SCC 684 viii

87. Suresh Sakharam Nangare v. State of (2012) 9 SCC 249 xi

Madhya Pradesh

88. Tulshidas Kanolkar v. State of Goa (2003) 8 SCC 590 iv

89. Veer Singh v. State of U.P., 2010 (1) A.C.R. 294 xii

(All.)

90. Vijj v. State of Karnataka (2008) 15 SCC 786 x

91. Yadav Lohar v. State of Bihar 1991 Supp (1) SCC 214 xiii

FOREIGN CASES

S.NO. CASE LAWS CITATION PAGE NUMBER

1. Graham v. Florida 560 US 48 (2010) iv

2. Madrid v. Gomez 889 F. Supp. 1146 (ND Cal. ii

1995)

3. Miller v. Alabama 567 US 460 (2012) iv

[7 | P a g e ]

MEMORIAL FOR THE PETITIONER

THE 2ND LEGAL INSIDER, MEMORIAL WRITING COMPETITION, 2020

INDEX OF AUTHORITIES

4. Roper v. Simmons 543 US 551 (2005) iv

5. S v Dyk (1969(1) SA 601(C) iv

6. Stanford v. Kentucky 492 US 361 iv

7. Winterbottom v Wright 152 ER 402 i

BOOKS

1. DR. HARI SINGH GOUR, 1 INDIAN PENAL CODE (14th ed. Law Publishers Pvt. Ltd.,

Allahabad 2013) .......................................................................................................................... x

2. JUSTICE G P SINGH, PRINCIPLES OF STATUTORY INTERPRETATION (12th ed. Lexis

Nexis Butterworths Wadhwa, Nagpur 2010). .......................................................................... viii

3. KD GAUR, CRIMINAL LAW CASES AND MATERIALS (7th ed. Lexis Nexis, Gurgaon

2013)............................................................................................................................................ x

4. M.P. TANDON, THE INDIAN PENAL CODE (23th ed. Allahabad Law Agency, Faridabad

2005)............................................................................................................................................ x

5. S.K. SARVARIA, R.A. NELSON’S INDIAN PENAL CODE (9th ed. Lexis Nexis

Butterworths Gurgaon 2002). ...................................................................................................... x

JOURNALS

1. Franklin E. Zimring, The Changing Legal World of Adolescene, MAcmillan Publishing Co.

New York, (1985) ...................................................................................................................... iii

2. Hon’ble Justice M.L Singhal, Medical Evidence and it’s use in trial of cases, J.T.R.I. Journal,

Issue – 3, September, 1995....................................................................................................... xiv

3. Northern Kentucky L. Rev. 205-224 (2014) ............................................................................... ii

[8 | P a g e ]

MEMORIAL FOR THE PETITIONER

THE 2ND LEGAL INSIDER, MEMORIAL WRITING COMPETITION, 2020

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION

Petitioners approach the Hon’ble Supreme Court of Indiana under Article 1361 of the

Constitution of Indiana which gives discretionary power to the Supreme Court of Indiana to hear

any matter on appeal against the order passed by any court or tribunal in the territory of Indiana

where justice and equity so demands.

Whereas the last Petitioner approaches this Hon’ble Supreme Court by filing a Public Interest

Litigation under Article 322 of the Constitution of Indiana which gives the power to the Supreme

Court any petition in the form of a writ.

1

“(1) Notwithstanding anything in this Chapter, the Supreme Court may, in its discretion, grant special leave appeal

from any judgment, decree, determination, sentence or order in any cause or matter passed or made by any court or

tribunal in the territory of India. (2) Nothing in clause (1) shall apply to any judgment, determination, sentence or

order passed or made by any court or tribunal constituted by or under any law relating to the Armed Forces.” 2 32.

Remedies for enforcement of rights conferred by this Part (1) The right to move the Supreme Court by appropriate

proceedings for the enforcement of the rights conferred by this Part is guaranteed.

2

The Supreme Court shall have power to issue directions or orders or writs, including writs in the nature of habeas

corpus, mandamus, prohibition, quo warranto and certiorari, whichever may be appropriate, for the enforcement of

any of the rights conferred by this Part (3) Without prejudice to the powers conferred on the Supreme Court by

clause ( 1 ) and ( 2 ), Parliament may by law empower any other court to exercise within the local limits of its

jurisdiction all or any of the powers exercisable by the Supreme Court under clause ( 2 ) (4) The right guaranteed by

this article shall not be suspended except as otherwise provided for by this Constitution.

[9 | P a g e ]

MEMORIAL FOR THE PETITIONER

THE 2ND LEGAL INSIDER, MEMORIAL WRITING COMPETITION, 2020

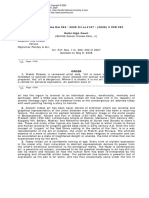

STATEMENT OF FACTS

a

Mr. Singhal Mr. Saxena

Employee

Son Daughter Son

Friends Friends Friends

Gaurav Ransom Peter Arther Phillips

Vaishali

Enemy

12th March,

8th March, 2015 Exhibition 12th March, 10th March, 2015 Arrest

2015 Arrest 2015 Arrest

Death Death by

15th May, 15th May, 15th May,

by head Asphyxia. Her

2015 Case 2015 Case 2015 Case

injury clothes were torn

admitted admitted admitted

and and she had

into Juvenile into Juvenile into Juvenile

internal several scratches

Court Court Court

bleeding and injuries.

Well aware of

Well aware of

circumstances 9th June,

circumstances and

insufficiency of age

Case admitted into 2015 Guilty

Sessions Court u/s304, 326,

Case admitted into 354 r/w 34

Sessions Court Juvenile

IPC, 1860

12th June, 2015 Case and

28th July, 2015

remanded back to Juvenile sentenced for

Guilty u/s 304,

Court 1 year in

17th December, 2014 326, 354 r/w 34

4th August, 2015 Guilty u/s special home

Juvenile Justice (Care IPC, 1860

and Protection of 304, 326, 354 r/w 34 IPC,

Children’s) Act Appealed the High 1860 and sentenced for 3 No further

Passed. Court which years in special home appeals

rejected the same

20th January, 2014

Appealed the Sessions Court

Juvenile Justice (Care

which dismissed the same

and Protection of

Children’s) Act

enforced. Revision Petition in the High

Court which rejected the same

PIL filed by ZIO 11th January, 2016 Appeal

Foundation filed in the Apex Court

challenging the act.

[10 | P a g e ]

MEMORIAL FOR THE PETITIONER

THE 2ND LEGAL INSIDER, MEMORIAL WRITING COMPETITION, 2020

ISSUES RAISED

……………………………….. ISSUE I………………………………..

WHETHER THE JUVENILE JUSTICE (CARE AND PROTECTION OF CHILDREN) ACT, 2014

IS CONSTITUTIONAL OR NOT?

……………………………….. ISSUE II ………………………………..

WHETHER THE HIGH COURT AND SESSION’S COURT WERE JUSTIFIED IN REJECTING

THE TEST FOR DETERMINATION OF SHYAMA’S AGE OR NOT?

……………………………….. ISSUE III………………………………..

WHETHER SHEKHAR SHOULD BE ACQUITTED OF ALL THE CHARGES LEVELED

AGAINST HIM OR NOT?

[11 | P a g e ]

MEMORIAL FOR THE PETITIONER

THE 2ND LEGAL INSIDER, MEMORIAL WRITING COMPETITION, 2020

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENTS

I. THAT THE JUVENILE JUSTICE (CARE AND PROTECTION OF CHILDREN) ACT,

2014 IS CONSTITUTIONAL

The JJ. Act, 2014 is not Constitutional as it was not the need of the hour. It did not preced a

consultative process. It is violative of the Art. 14, Art. 15 and Art. 21 as it does not permit

reasonable classification of the juveniles belonging to the age-group of 16-18 yrs. in case of

commission of heinous offences. The procedure followed is not appropriate and does not stand

the test under the Constitution. The Act is not in consonance with various International

Covenants and Rules. The new act is not oa beneficial piece of legislation rather a legislation

which is not in juxtaposition to the JJ. act, 2000.

II. THAT THE HIGH COURT AND SESSION’S COURT WERE NOT JUSTIFIED IN

REJECTING THE TEST FOR DETERMINATION OF RANSOM’S AGE

The Courts of Law were not justified in rejecting the test on the ground that it is certain that in all

probabilities his age was > 16 yrs. The test should be conducted because different results would

have been given as the age of Ransom in probable sense is less than 16. As per the preliminary

assessment of the JJ. Board he was not found capax of committing the offence. His act does not

satisfy the ingredients of a heinous crime because of the ambiguity in the definition.

III. THAT PETER’S CONVICTION BY THE JUVENILE BOARD, SESSION COURT

AND THE HIGH COURT WAS NOT VALID

It is submitted that Peter’s guilt hasn’t been proved beyond reasonable doubt on the basis of

circumstantial evidence, medical evidence and ocular evidence. The prosecution has established

that there exists no chain of circumstantial evidence and it doesn’t point towards only conclusion

that Peter is not guilty and rules out any other possibility. Peter’s culpability isn’t clearly

established by his prior animosity with Gaurav and Vaishali and his subsequent act of grabbing

an opportunity to talk to Ransom. His presence at the crime scene where he was seen sneaking

away doesn’t complete the chain of circumstantial evidence. Hence, the decision of the High

Court must not be upheld.

[12 | P a g e ]

MEMORIAL FOR THE PETITIONER

THE 2ND LEGAL INSIDER, MEMORIAL WRITING COMPETITION, 2020

ARGUMENTS ADVANCED

I. THAT THE JUVENILE JUSTICE (CARE AND PROTECTION OF CHILDREN) ACT,

2014 IS NOT CONSTITUTIONAL

(¶ 1.) This is the humble submission of the counsel of Petitioners that the JJ. Act, 2014 is not

constitutional. The counsel has proposed this contention in a three–fold manner, [A] The act was

not the need of the hour, [B] The act is in contravention with the Constitution of Indiana, [C] The

act is not in consonance with the International Law.

A. The act was not the need of the hour

(¶ 2.) The Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015 is not the need of the

hour. This sub contention has been proposed by the counsel of petitioners in a two-fold manner.

i. The bad law (JJ act, 2015) was a product of a hard case

(¶ 3.) The JJ. Act, 2015 was a bad law, product of a hard case as observed by Justice Robert Rolf

in the case of Winterbottom v. Wright stated: "This is one of those unfortunate cases in which, it

is, no doubt, a hardship upon the plaintiff to be without a remedy but by that consideration we

ought not to be influenced."3 The Nirbhaya case is one such bad example. It is therefore urged a

mere hardship is not enough4 no matter how horrifying or terrible it might be.5

(¶ 4.) The J. Verma Committee constituted in the aftermath of the Nirbhaya case, to look into

possible amendments to criminal law, also recommended against the reduction of the age of the

juvenile6. Despite cogent reasons proposed by the committees and the Apex Court, the

parliament

3

Winterbottom v Wright, 152 ER 402.

4

Bangalore Wollen, Cotton and Silk Mills, Co. Ltd. v. Corporation. of City of Bangalore, AIR 1962 SC 1263.

5

Balco Employees Union v. Union of India (2002) 2 SCC 333

6

Justice J.S Verma, Justice Leila Seth, Gopal Subramanium, Report of the Committee on Amendments to Criminal

Law, 2013: Page 276 ¶ 45.

[i | P a g e ]

MEMORIAL FOR THE PETITIONER

THE 2ND LEGAL INSIDER, MEMORIAL WRITING COMPETITION, 2020

ARGUMENTS ADVANCED

succumbed to popular demand resonating through media frenzy and proceeded with the Act in its

present form.

(¶ 5.) Moreover, it is submitted that out of the 472 million children in our country, only 1.2 %

actually committed crimes in 2012 and 2013. In 2013, of all the children apprehended for crimes

under the Indian Penal Code, 2.17% were accused of murder and 3.5% were accused of rape.

That is 2% of 1.2%. These figures of the NCRB, account for the FIRs registered and not the

children who were actually found guilty.7

(¶ 6.) Therefore, it is not justified to treat a juvenile at par with an adult based on one bad

incident

ii. Ignorance on part of the government

(¶ 7.) The government jettisoned its responsibility to take into account the experience of

countries which have adopted the practice of transfer of children to the adult criminal justice

system.8 The Court in Madrid v. Gomez9, observed that the modern prison life may press the

outer bounds of what most humans can psychologically tolerate. The observation of J. Krishna

Iyer that the adult prisons are like "animal farms".10 The future of child offenders in adult

prisons, presents a bleak picture. Owing to such a system, the juveniles are at a greater risk of

committing suicide and suffering from sexual and physical abuse meted out to them by older

inmates. A direct causal link can be drawn to the effects of the brutalization and the harms

suffered by juveniles. The culture and environment in prison, fosters behavior in juveniles that

increases their chance of recidivism. They are also exposed to techniques which they can utilize,

in order to indulge in illegal activities, on their return to the society.

B. The act is in contravention with the Constitution of Indiana

7

National Crime Record Bureau, Crime in India 2013 Statistics, available at

http://ncrb.nic.in/StatPublications/CII/CII2013/Statistics-2013.pdf , last seen on 2/1/2017.

8

Donna Bishop et. al., The Transfer of Juvenile to Criminal Court: Does it make a difference?, 42 Crime and

Delinquency, 171-91 (1996); Karen Miner-Romanoff, Juvenile Offenders tried as adult: What they know and

implications for practitioners, 41 Northern Kentucky L. Rev. 205-224 (2014); Deanie C. Allen, Trying Children as

Adults, 6 Jones L. Rev. 27-64 (2002)

9

Madrid v. Gomez, 889 F. Supp. 1146 (ND Cal. 1995)

10

Satto v. State of UP, (1979) 2 SCC 628.

[ii | P a g e ]

MEMORIAL FOR THE PETITIONER

THE 2ND LEGAL INSIDER, MEMORIAL WRITING COMPETITION, 2020

ARGUMENTS ADVANCED

(¶ 8.) In State of Tamil Nadu v. Shyam Sunder11, the court held that, to make an act as Ultra

Vires or to make any amendment in it the relevant act or provision as the case maybe must be

proved violative of the fundamental rights.

(¶ 9.) The JJ Bill, 2014 was examined by the Department Related Parliamentary Standing

Committee, which in its 264th report took note that certain provisions of the legislation being

ultra vires of the Constitution. It also took cognizance of the fact that the children, are likely to

be adversely affected by the legislation. It rejected the bill as being unwarranted and

unconstitutional in the following words: "[T]he existing Juvenile Justice Act, 2000 recognizes

the fact that 16-18 years is an extremely sensitive and critical age requiring greater protection.

Hence, there is no need to subject them to a different or an adult judicial system as it will violate

Article 14, 15(3)12, 21 of the Constitution.13 In catena14 of cases, the constitutionality of

definition of child under 18 years was challenged as ultra vires Constitution. The new act also

violates Article 21 of the Constitution.

(¶10.) The counsel will further substantiate it in the following manner:

i. The act is inconsistent with article 14 of the Constitution of Indiana

(¶11.) The counsel humbly submits that inclusion of all under 18 into a class called juvenile

under the act is not valid as it does not provide separate scheme of investigation, trial and

punishment for offences committed by them and such categorization is not identifiable,

distinguishable and reasonable thus violating Article 1415.

(¶12.) Children and adults being on an unequal footing with respect to their psychological

development, ought not to be treated alike.16 Subjecting children in same manner as adults, is

11

State of Tamil Nadu v. Shyam Sunder, (2011) 8 SCC 737

12

R.D Upadhyay v. State of A.P and Ors., AIR 2006 SC 1946

13

Two Hundred Sixty Fourth Report The Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Bill, 2014, Parliament

of India, http:// www.prsindia.org/ uploads/media/ Juvenile%20Justice/ SC%20 report-%20Juvenile%20justice.pdf.

14

Salil Bali v Union of India, (2013) 7 SCC 705, Subramanian Swamy v. Raju, (2014) 8 SCC 390

15

Roop Chand Adlakha v. DDA, 1989 Supp (1) SCC 116.

16

M. Nagaraj v. Union of India, AIR 2007 SC 71, RK Garg v Union Of India, AIR 1981 SC 2138, Franklin E.

Zimring, The Changing Legal World of Adolescene, MAcmillan Publishing Co. New York, (1985).

[iii | P a g e ]

MEMORIAL FOR THE PETITIONER

THE 2ND LEGAL INSIDER, MEMORIAL WRITING COMPETITION, 2020

ARGUMENTS ADVANCED

premised on the flawed assumption that children and adults can be held to the same standard of

culpability and that children are capable of participating in legal proceedings in a like manner.

Expecting the same level of psychological understanding and behavior as adults from children17,

is synonymous to treating unequals as equals thus violating Article 14.

ii. The act is inconsistent with Article 15(3) of the Constitution of Indiana

(¶13.) Article 15(3) of the Constitution mandates that states make special provisions in favor of

children, not against them.18 The state has a Constitutional obligation to safeguard their interests

and welfare in the real sense, not by doing them a favor, as charity.19

iii. The act is inconsistent with Article 21 of the Constitution of Indiana

(¶14.) It is submitted that, the main objective of the act is to provide for care, protection,

treatment, development and rehabilitation of the neglected or the delinquent juveniles.20 So, the

essence of the act is restorative and not retributive, providing for rehabilitation and integration of

children in conflict with law back into the mainstream society.21 The counsel hereby submits

that, the act is against Right to Life as it does not aim at providing better living conditions to the

Juveniles22 and also harms their dignity.23

C. The act was in contravention with the international law

17

S v Dyk, (1969(1) SA 601(C), Stanford v. Kentucky, 492 US 361, Roper v. Simmons, 543 US 551 (2005);

Graham v. Florida, 560 US 48 (2010); Miller v. Alabama,567 US 460 (2012).

18

Sri Mahadeb Jiew and Anr. v. Dr. B.B Sen, AIR 1951 Cal 563; Independent Thought v. Union of India, AIR 2017

SC 4904.

19

Sampurna Behura v. Union of India (UOI) and Ors., (2018) 4 SCC 433.

20

Avishek Goenka v. Union of India (2012) 5 SCC 321.

21

Abuzar Hussain v. State of West Bengal, (2012) 10 SCC 489.

22

Essa v. State of Maharashtra, 2013 (4) SCALE 1

23

The Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015, No. 02 of 2016, INDIA CODE, § 2(20);

Manjula Krippendorf v. State (Govt. of NCT of Delhi) and Ors, AIR 2017 SC 3457, Tulshidas Kanolkar v. State of

Goa, (2003) 8 SCC 590; Suchita Srivastava and Anr. v. Chandigarh Administration, (2009) 9 SCC 1; Reena

Banerjee and Anr. v. Govt. (NCT of Delhi) and Ors., (2015) 11 SCC 725; Mofil Khan and Anr. v. State of

Jharkhand, (2015) 1 SCC 67.

[iv | P a g e ]

MEMORIAL FOR THE PETITIONER

THE 2ND LEGAL INSIDER, MEMORIAL WRITING COMPETITION, 2020

ARGUMENTS ADVANCED

(¶15.) The impugned act dishonors the principle of pacta sunt servanda stated in the Article 26 of

the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties stating: every treaty signed by a country is

binding on it and the obligations imposed by treaties must be performed by the country in

good faith.24 A party may not invoke the provisions of its internal law as justification for its

failure to perform a treaty. The counsel hereby submits that in this case the country’s domestic

laws are inconsistent with the international law.25 This contention has been further substantiated

in a two-fold manner

i. The act is inconsistent with the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child

(¶16.) The impugned amendment is against the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child as the

object clause of the present amendment states: "And whereas, the Government of India has

acceded on the 11th December, 1992 to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, adopted by

the General Assembly of United Nations which has prescribed a set of standards to be adhered

to by all State parties in securing the best interest of child." The mention of UNCRC in the

objective of the impugned amendment is a mere eye wash as the amendment seeks to erode the

very definition of child as envisaged in the Article 1 of the convention which reads as "For the

purposes of the present Convention, a child means every human being below the age of eighteen

years unless under the law applicable to the child, majority is attained earlier."

(¶17.) UNCRC, 1990 read with the concluding resolution of the committee on child rights

(constituted under the UN convention) of the year 2000 and the General Resolution of the year

2007 clearly contemplate the MACR as 18 yrs. and mandates member states to act accordingly.

(¶18.) General Comment No.10 specifically reminds State Parties of their obligations under the

UNCRC: "they have recognized the right of every child alleged as, accused of, or recognized as

having infringed the penal law to be treated in accordance with the provisions of article 40 of

UNCRC. This means that every person under the age of 18 years, at the time of the alleged

commission of an offence, must be treated in accordance with the rules of juvenile justice.26

24

Art. 26 of Vienna convention see at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/pacta-sunt-servanda last accessed on 11

August 2020.

25

K. Padmaja, Juvenile Delinquency, ICFAI University Press (2007).

26

General Comment No. 10, Children’s Rights in Juvenile Justice, para 37, 38 (2007)

[v | P a g e ]

MEMORIAL FOR THE PETITIONER

THE 2ND LEGAL INSIDER, MEMORIAL WRITING COMPETITION, 2020

ARGUMENTS ADVANCED

ii. Fails to conform to the declaration of the rights of the child (declaration of Geneva)

(¶19.) The declaration is the first international instrument on children’s rights, advocated that

child offenders should be transformed, not penalized. The instrument casts a duty on humankind

that “the delinquent child must be reclaimed.”27

iii. Fails to conform to the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Administration of

Juvenile Justice (Beijing rules)

(¶20.) The Beijing rules categorically spelt out the minimum standard to be followed by member

states. It states in detail, the treatment to be meted out to juveniles without distinction of any

28

kind. It focuses on rehabilitation aspects of the juvenile, while also stipulating a variety of

dispositions.29 Rule 2.2(a) defines juvenile as a child or young person who, under the respective

legal system, may be dealt with for an offence differently than an adult. Rule 4.1 mandates

Member states to refrain from a minimum age of criminal responsibility that is too low, bearing

in mind the facts of emotional, mental and intellectual maturity.

iv. Fails to conform to the UN guidelines for the prevention of child delinquency (the Riyadh

guidelines)

(¶21.) The guidelines stressed and recognized in spirit that: part of maturing often includes

behavior that does not conform to societal norms and that tends to disappear in most individuals

with the transition to adulthood and avoid labelling a youth a deviant or delinquent as this

contributes to negative pattern of behavior.30

v. Fails to conform the UN rules for the protection of juveniles deprived of their liberty (the

Havana rules)

27

Covenant of the League of Nations adopting Geneva Declaration of the Rights of the Child on 26 September,

1924.

28

G.A. Res. 40/33, United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Administration of Juvenile Justice (Nov. 29,

1985).

29

Rules 24.1 and 25.1.

30

G.A Res. 45/112, United Nations Guidelines for the Prevention of Juvenile Delinquency (Dec. 14, 1990).

[vi | P a g e ]

MEMORIAL FOR THE PETITIONER

THE 2ND LEGAL INSIDER, MEMORIAL WRITING COMPETITION, 2020

ARGUMENTS ADVANCED

The Havana rules is the first international instrument that defines a juvenile is every person

under the age of 18.31

II. THAT THE HIGH COURT AND SESSION’S COURT WERE NOT JUSTIFIED IN

REJECTING THE TEST FOR DETERMINATION OF RANSOM’S AGE

(¶22.) It is the humble submission of the counsel of petitioners that the High Court and the

Session’s Court were not justified in rejecting the test for determination of Ransom’s age. This

contention has been proposed in a three-fold manner. [A] The preliminary assessment was not

conducted in consonance with the new act, [B] The ossification test should be conducted, [C]

The guilt has not been established beyond.

A. The preliminary assessment was not conducted in consonance with the JJ. Act, 2014

(¶23.) The essentials of the preliminary assessment were not fulfilled

i. Ransom did not commit a heinous offence

(¶24.) The definitions of both the serious offence and the heinous offence are vaguely worded.

The ambiguous classification certainly creates a fourth class. Thus, the offences under which

Ransom is charged accept § 302 of IPC, 1860 are not heinous offences.

ii. Ransom’s age is not between 16-18 yrs.

(¶25.) The Education Act in its § 11 says that the elementary education starts at the age of three

yrs. thus, the age of Ransom in all probability sense cannot be above 16 yrs. As mentioned by the

Hon’ble court in Rajindra Chandra v. State of Chhattisgarh that the standard of proof for age

determination is the degree of probability and not proof beyond reasonable doubt.

iii. Ransom was not capax of committing the offence

31

G.A Res. 45/113, United Nations Rules for the Protection of Juveniles Deprived of their Liberty (Dec. 14, 1990),

Rule 11(a).

[vii | P a g e ]

MEMORIAL FOR THE PETITIONER

THE 2ND LEGAL INSIDER, MEMORIAL WRITING COMPETITION, 2020

ARGUMENTS ADVANCED

(¶26.) He did not possess the required mental capacity as the brain of a juvenile i.e. under the age

of 18 yrs. is still developing or still not mature enough to understand the circumstances and thus

it is not capable enough to develop the required intention to be charged under IPC, 186032.

B. The ossification test should be conducted

(¶27.) It is humbly submitted that the ossification test should be conducted to ascertain

Ransom’s age.

i. Understanding the word shall according to § 94 of the act

(¶28.) “The word ‘shall’ as observed by J. Hidayatullah “is ordinarily mandatory but it is

sometimes not so interpreted if the context or the intention otherwise demands”33, and this is also

pointed out by J. Subarao that “When a statute uses the word ‘shall’, prima facie is mandatory,

but carefully attending to the whole scope of the statute”34. If different provisions are connected

with the same word ‘shall’, and if with respect to some of them the intention of the Legislature is

clear that the word ‘shall’ in relation to them must be given an obligatory or a directory meaning,

it may indicate that with respect to other provisions also, the same construction should be placed.

35

Furthermore, a provision in a statute procedural in nature although employs the word "shall"

may not be held as mandatory if thereby no prejudice is caused. 36 The provision of § 94 of the

JJ. Act, 2014 may be construed as both mandatory and directory.37

(¶29.) Two considerations for regarding a provision as directory are: [A] absence of any

provision for the contingency of a particular provision not being complied with or followed and,

[B] serious general inconvenience and prejudice that would result to the general public if the act

32

Mal Singh v. Union of India and Ors. (1980) 2 SCC 684, Sunil Batra v. Union of India and Ors. (1982) 2 SCC

684, Nathu Singh and Ors. v. Union of India and Another. (1980) 2 SCC 675, Sher Singh and Another v. State of

Punjab and Another (1980) 2 SCC 696, Kartar Singh and Ujagar Singh v. Delhi Administration (1979) 2 SCC 675.

33

Sainik Motors v. State of Rajasthan, AIR 1961 SC 1480.

34

State of U.P. v. Babu Ram, AIR 1961 SC 751.

35

Hari Vishnu Kamath v. Ahmad Ishaque, AIR 1955 SC 233

36

PT Rajan v. TPM Sahir, AIR 2003 SC 4603.

37

JUSTICE G P SINGH, PRINCIPLES OF STATUTORY INTERPRETATION (12th ed. Lexis Nexis Butterworths

Wadhwa, Nagpur 2010).

[viii | P a g e ]

MEMORIAL FOR THE PETITIONER

THE 2ND LEGAL INSIDER, MEMORIAL WRITING COMPETITION, 2020

ARGUMENTS ADVANCED

of the Government or an instrumentality is declared invalid for noncompliance with the

particular provision.38

(¶29.) In each case one must look to the subject matter and consider the importance of the

provision disregarded and the relation of that provision to the general object intended to be

secured. The counsel hereby submits that the observation of the division bench in the above cited

case law is very clear stating that a provision can be regarded as directory if it will not result in

serious general inconvenience and prejudice to the general public by reading it in that manner. In

addition, Ransom’s age cannot be ascertained beyond reasonable doubt thus, Ransom’s age

should be ascertained through the test.

ii. Inconclusivity as an insufficient ground for rejecting the plea

(¶30.) The JJ. Act, 2014 states that In case, the Committee or the Board has reasonable grounds

for doubt regarding whether the person brought before it is a child or not, the Committee or the

Board, as the case may be, shall undertake the process of age determination, by seeking evidence

by obtaining — (i) The date of birth certificate from the school, or the matriculation or

equivalent certificate from the concerned examination Board, if available; and in the absence

thereof; (ii) The birth certificate given by a corporation or a municipal authority or a panchayat;,

(iii) And only in the absence of (i) and (ii) above, age shall be determined by an ossification test

or any other latest medical age determination test conducted on the orders of the Committee or

the Board” It is a well-accepted fact in the precedents of our Indian Judiciary that the last resort

for age determination of a juvenile is the Bone Test i.e. Ossification Test.39

(¶31.) The court of law has time and again relied on the fact that the ossification test in cases

where the certificates are manipulated or not available the Hon’ble court has always given the

judgement placing the argument entirely and primarily on the test report.40

38

Atlas Cycle Industries Ltd. v. State Of Haryana, AIR 1979 SC 1149.

39

Ashwani Kumar Saxena v. State of M.P (2012) 9 SCC 750, Jai Prakash Tiwari v. State of U.P (2016) 97 AIICC

592, Om Prakash v. State of Rajasthan and Ors. (2012) 5 SCC 201, Ramdeo Chauhan v. State of Assam (Crl.) 4 of

2000.

40

Rajindra Chandra v. State of Chhattisgarh and Anr. (2002) 2 SCC 287., Gulam Hossain v. State of WB (2012) 10

SCC 489, Akbar Sheikh (2009) 7 SCC 415, Pawan (2009) 15 SCC 259, Jitendra Singh (2010) 13 SCC 523, Jitendra

Ram v. State of Jharkhand (2006) 9 SCC 428, Gunga v. State of Rajasthan (2015) 2 SCC 775.

[ix | P a g e ]

MEMORIAL FOR THE PETITIONER

THE 2ND LEGAL INSIDER, MEMORIAL WRITING COMPETITION, 2020

ARGUMENTS ADVANCED

iii. Benefit of Doubt

(¶32.) The Hon’ble courts have time and again stressed on the dignity of child and hence have

provided the benefit of doubt to the accused41.

III. THAT PETER SHOULD BE ACQUIITED OF ALL THE CHARGES LEVIED

AGAINST HIM

(¶33.) The hon’ble bench is beseeched to overturn the conviction of peter upheld by the juvenile

board, sessions court and high court as invalid and inappropriate and there has been a gross

miscarriage of justice as the fact that peter has committed the offence cannot be proved without

an iota of doubt and is nothing but sheer uncertainty. No accused should end up with a heavier

liability than what is strictly contemplated by the law and conversely that there should be not a

failure of justice through to light a consequence for wrongful conviction.42

A. Peter’s acts do not commend confidence under §34 of ipc,1860

(¶34.) In order to attract the provision of this section, it is not enough that there was the same

intention on the part of the several people to commit a particular criminal act or a similar

intention.43 Intention is a question of fact which is to be gathered from the acts of the parties.44 It

is trite law that § 34 is only a rule of evidence and does not create a substantive offence. 45 It

means that if two or more persons do a thing jointly, it is just the same as if each of them has

done it individually.46 Common intention requires a prior consent or a pre-planning.47 For

41

Shweta Gulati v. State (NCT of Delhi) (2004) 89 SCC 654, Raju Kumar v. State of Haryana (2010) 3 SCC 235,

Arnit Das v. State of Bihar (2000) 5 SCC 488

42

Vijj v. State of Karnataka (2008) 15 SCC 786

43

KD GAUR, CRIMINAL LAW CASES AND MATERIALS (7th ed. Lexis Nexis, Gurgaon 2013).

44

M.P. TANDON, THE INDIAN PENAL CODE (23th ed. Allahabad Law Agency, Faridabad 2005).

45

S.K. SARVARIA, R.A. NELSON’S INDIAN PENAL CODE (9th ed. Lexis Nexis Butterworths Gurgaon 2002).

46

DR. HARI SINGH GOUR, 1 INDIAN PENAL CODE (14th ed. Law Publishers Pvt. Ltd., Allahabad 2013), State

of Mysore v. Venappasetty, 1973 CrLJ 1568.

47

State of Mysore v. Venappasetty, 1973 CrLJ 1568.

[x | P a g e ]

MEMORIAL FOR THE PETITIONER

THE 2ND LEGAL INSIDER, MEMORIAL WRITING COMPETITION, 2020

ARGUMENTS ADVANCED

attracting the §34 of the impugned ethic necessitates commission of a criminal act by several

persons in furtherance of a common intention pointing out the participation of all48.

(¶35.) The presence of every ingredient can be clearly denied. Death of the deceased by asphyxia

and grievous blows indicate towards the commission of a criminal act but the burden of the same

cannot be levied upon Peter. The other essentials are further substantiated in a twofold manner.

i. There is no commonality of intent

(¶36.) In Ranganath Sharma v. Satendra Sharma49, it was held, “Direct proof of common

intention is seldom available and, therefore, such intention can only be inferred from the

circumstances appearing from the proved facts of the case and the proved circumstances. The

prosecution has to establish by evidence, whether direct or circumstantial, that there was plan or

meeting of minds of all the accused person be it pre-arranged or on the spur of the moment; but it

must necessarily be before the commission of the crime.”

(¶37.) Section 33 states that word act denotes a series of acts as well a single act. 50 Thus, even

many may have committed different acts, they have cumulatively committed criminal act which

resulted in death of deceased and are liable for same punishment51 but in the instant case that

culpability cannot be put onto Peter. Section 34 IPC includes commission of overt act 52,

Participation53, Specific Role54 but the only part attributable to the accused is the grievous

enmity which isn’t sufficient cause to hold the accused liable55 and there is a presumption of

innocence in favour of the accused56. Participation in the case of common intention would not

48

Parichat v. state of Madhya Pradesh, AIR 1972 SC 535.

49

(2009) 1 SCC (Cr.) 415.

50

Section 33, Indian Penal Code, 1860

51

Selvam v. State of Tamil Nadu (2012) 10 SCC 402

52

Nachimuthu v state of Tamil Nadu (2011) 14 SCC 441

53

Suresh Sakharam Nangare v. State of Madhya Pradesh (2012) 9 SCC 249

54

Nand Kishore v. State of Madhya Pradesh (2011) 12 SCC 120, Khalil Chishti v. State of Rajasthan (2013) 2 SCC

541

55

Ramuthai v. State (2011) 13 SCC 212

56

Ram Jag v. State of Uttar Pradesh AIR 1974 SC 606

[xi | P a g e ]

MEMORIAL FOR THE PETITIONER

THE 2ND LEGAL INSIDER, MEMORIAL WRITING COMPETITION, 2020

ARGUMENTS ADVANCED

depend on the extent of overt act.57 There is absence of any specific averment demonstrating the

role of the accused in commission of offence, no prima facie case can be made out against the

accused58. The said intention did not develop at the time of the incident as well and therefore, it

was held that Section 34 of the IPC cannot be resorted to hold the accused guilty of any crime. 59

Accused causing simple injuries60 61

and holding legs or arms cannot be made a ground for

formation of common intention. In Bikramaditya Singh v. State of Bihar62 it was held that

exhortation to kill the deceased was attributed as only role played by the accused though he was

armed with firearm at the time, implausibility of such conduct had accused really shared

common intention. The incident of the fight with Gaurav and strangulation of Vaishali had taken

place in heat of passion on account of a sudden erupted instance unfortunately calumniating in

demise, no, evidence suggests pre-mediation on part of accused.63The others cannot be attributed

the common intention of inflicting injuries which resulted in the death of the deceased.64

ii. That peter was present in the exhibition

(¶38.) The ocular evidence provided by Ram Manohar on 10th March, 2015 proves his presence

as he saw him sneaking out of the basement on the night of 8th March, 2015. Peter too has not

disputed this fact but he has time and again stressed that he was just present in the exhibition.

Mere presence of the accused on the spot when the incident took place is not sufficient to hold

57

Mano Dutt v. State of Uttar Pradesh (2012) 4 SCC 79

58

Ashok Basak v. State of Maharashtra (2010) 10 SCC 660

59

Veer Singh v. State of U.P., 2010 (1) A.C.R. 294 (All.).

60

A Mohnam v. State of kerela 1990 Supp SCC 66

61

Suresh Sakharam Nangare v. State of Maharashtra (2012) 9 SCC 249

62

(2013) 2 SCC (Cri) 169

63

Bishnupada Sarkar v. State of West Bengal AIR 2012 SC 2248

64

State of Rajasthan v. Manoj Kumar 138 AIC 261 (SC)

[xii | P a g e ]

MEMORIAL FOR THE PETITIONER

THE 2ND LEGAL INSIDER, MEMORIAL WRITING COMPETITION, 2020

ARGUMENTS ADVANCED

the accused65 and can’t be the basis to record a finding of guilt66 and does not make a case

beyond reasonable doubt67. Such presence cannot establish intention of rape.68

B. There is no sufficient evidence to prove peter’s guilt beyond reasonable doubt

(¶39.) The judgment pronounced by the Sessions Court opines that peter’s case has been proved

beyond reasonable doubts before juvenile board which was later upheld by the high court but the

lapses, had left serious lacunae in the case against the accused. Evidence against accused though

highly incriminating yet some loose links are not satisfactorily explained, handling the case

improbable.69

i. Penurious or no medical attestation present

(¶40.) The court emphasized that, even in if medical attestation supports the commission of

sexual assault on the victim. We needn’t elaborate on the issue any more light of the concurrent

finding in clear terms holds that sign of commissions of rape on the victim stood proved by

medical evidence beyond reasonable doubt.70 In present case, the proposition nowhere mentions

presence of Peter’s fingerprints on Vaishali’s body is enough to prove that Peter was not

involved as the proposition contains the medical testimony of others but not him. Moreover, the

proposition nowhere specifically mentions that he was involved in inflicting grievous blows to

Gaurav and strangulating Vaishali for her to die of asphyxia.

ii. Untrustworthy ocular testimony prevails

(¶41.) As the popular saying goes witnesses are eyes and ears of justice, the oral evidence has

primacy over the medical evidence. Oral evidence can’t be rejected on hypothetical medical

65

State of Uttar Pradesh v. Rajvir (2007) 15 SCC 545, Nash v. State of Madhya Pradesh AIR 1953 SC 420

66

Bikash Bora v. State of Assam (2019) 4 SCC 280

67

Yadav Lohar v. State of Bihar 1991 Supp (1) SCC 214

68

Om Prakash v. State of Haryana (2011)14 SCC 309

69

Abdulwahab Abdulmajid Baloch v. State of Gujarat (2009) 11 SCC 625

70

Deepak v. State of Haryana, (2015) 4 SCC 762.

[xiii | P a g e ]

MEMORIAL FOR THE PETITIONER

THE 2ND LEGAL INSIDER, MEMORIAL WRITING COMPETITION, 2020

ARGUMENTS ADVANCED

evidence provided the oral testimony is reliable, creditworthy and inspires confidence. 71 Thus,

the position of law in instances where a contradiction prevails between medical evidence and

ocular evidence can be crystallized to the effect that though the ocular testimony of a witness has

greater evidentiary value vis-à-vis medical evidence, when medical evidence makes the ocular

testimony impossible, that becomes a relevant factor in the process of evaluation of evidence.72

As per Sec 118, Indian Evidence Act, all persons shall be competent witnesses, unless they are

prevented from understanding or answering question put to them virtue of tender years, extreme

old age, disease or infirmity lunacy or any other cause of same kind.73

(¶42.) A chance and ocular witness, Ram Manohar’s statement requires a cautious and close

scrutiny and his presence at the crime spot must be explained74, if doubtful it must be

discarded75. Where a large number of offenders are involved, it is necessary to seek

corroboration at least from two or more witnesses as a measure of caution76, here, evidence of

the complainant’s witness is not corroborated by any other independent witness which fails to

commend confidence.77 Ram Manohar just saw him fleeing and not committing the act. Only one

firm conclusion can be made that Peter cannot is not blameworthy.

iii. Circumstancial evidence is fully established

(¶43.) Human agency can express faulty picture but circumstantial agency cannot fail78 literally

meaning men may tell lies, but circumstances do not.79 If the cumulative effect of all the facts

71

Hon’ble Justice M.L Singhal, Medical Evidence and it’s use in trial of cases, J.T.R.I. Journal, Issue – 3,

September, 1995, Solanki Chimanbhai Ukabhai v. State of Gujarat, AIR 1983 SC 484.

72

Abdul Sayeed vs State Of M.P, (2010) 10 SCC 259.

73

Sec 118, Indian Evidence Act, 1872

74

Sarvesh Narain Shukla v. Daroga Singh and Ors., (2007) 13 SCC 360

75

Shankarlal v. State of Rajasthan, (2004) 10 SCC 632.

76

Mrinal Das v. State of Tripura (2011) 9 SCC 479

77

State of Uttar Pradesh v. Munni Ram (2010) 14 SCC 364

78

Rewa Ram v. State of Madhya Pradesh, (1978) Cr.L.J. 858.

79

Aftab Ahamd Anasari v. State of Uttaranchal, 2010 2 SCC 583.

[xiv | P a g e ]

MEMORIAL FOR THE PETITIONER

THE 2ND LEGAL INSIDER, MEMORIAL WRITING COMPETITION, 2020

ARGUMENTS ADVANCED

form a chain so complete80 the guilt the conviction is justified ignoring the fact that isn’t,81

relying on the maxim, “Evidence has to be weighed not counted.”82

(¶44.) In State of Maharashtra v. Goraksha Ambaji Adsul83, the SC reiterated that in a case of

circumstantial evidence, if the prosecution is able to establish chain of events to satisfy

ingredients of commission of offence, accused would be liable to suffer consequences of his

proven guilt. In Sharad Birdichand Sarda v. State of Maharashtra84, the Apex Court described

the five golden principles that were laid down in Hanumant v. State of M.P85 of the proof based

on circumstantial evidence.

(¶45.) A chain of fully established facts consistent with hypothesis of the guilt excluding every

possible hypothesis except the one to be proved and should be of conclusive nature and tendency

not leaving behind any reasonable ground consistent with accused’s innocence.86 In cases

dependent on circumstantial evidence, to justify the inference of guilt, all the incriminating facts

and circumstances must be incompatible with the innocence of the accused or the guilt any other

person and incapable of explanation upon any other reasonable hypothesis than that of his guilt87

and the circumstances from which the conclusion of guilt is drawn, should be fully proved along

with being conclusive in nature.88 Any other hypothesis except the one to be proved, provided by

the Petitioners, however extravagant and fanciful, cannot be the basis of an acquittal.89 The effort

of the criminal court should not be to prowl for imaginative doubts.90

80

Rajesh Rai v. State of Sikkim, 2002 Cr.L.J. 1385 at P. 1390(Sikkim)

81

Ibid

82

Padaala Veera Reddy v. State of A.P, AIR 1990 SC 79

83

(2011) 7 SCC 437 (¶27)

84

AIR 1984 SC 1682.

85

AIR 1952 SC 343, Ravinder Singh v. State (NCT) of Delhi.

86

State of Uttar Pradesh v Satish, (2005) 3 SCC 114, Bhim Singh v. State of Uttrakhand (2015) 4 SCC 739.

87

Hukam v state, AIR 1977 SC 1063.

88

C. Chenga Reddy v State of AP, (1996) 10 SCC 193.

89

State of Andhra Pradesh v. IBS Prasad Rao AIR 1970 SC 648.

90

State of Rajasthan v. Tej Ram. (1999) 3 SCC 507.

[xv | P a g e ]

MEMORIAL FOR THE PETITIONER

THE 2ND LEGAL INSIDER, MEMORIAL WRITING COMPETITION, 2020

ARGUMENTS ADVANCED

(¶46.) There must be a chain of evidence so complete as not to leave any reasonable ground for

the conclusion consistent with the innocence of the accused and in all probability the act must

have been done by the accused91 which hasn’t been clearly established as it has already been

proved that grievous animosity92 and mere presence cannot be the ground. Sharing and talking to

Ransom only amounts to motive and not intention. There was no evidence much less credible

which was salvaged from the onslaught of witness.93

91

Ibid.

92

Subedar v. State of Uttar Pradesh AIR 1971 SC 125.

93

Javed Alam v. State of Chhattisgarh (2009) 6 SCC 450.

[xvi | P a g e ]

MEMORIAL FOR THE PETITIONER

THE 2ND LEGAL INSIDER, MEMORIAL WRITING COMPETITION, 2020

PRAYER

Whereof in the light of facts of the instant case, written pleadings and authorities cited, it is

humbly prayed before this Hon'ble Supreme Court that it may be pleased to hold, adjudge and

declare:

1. That the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2014 is unconstitutional.

2. That Ransom is not capax of committing the offences the charges of which are leveled

against him and that there is no need to conduct any test for determining his age.

3. That Ransom is not guilty under §§ 302, 326, 354 r/w § 34 of IPC, 1860.

4. That Peter is not guilty under §§ 302, 326, 354 r/w § 34 of IPC, 1860.

Pass any other order, which the court may deem fit in light of the facts of the case, evidences

adduced and justice, equity and good conscience.

And for this act of kindness, the counsel for the petitioner shall duty bound forever pray.

Sd/-

Counsels for the Petitioner

[xviii | P a g e ]

MEMORIAL FOR THE PETITIONER

You might also like

- Law of Partnerships (Indian Partnership Act 1932)From EverandLaw of Partnerships (Indian Partnership Act 1932)No ratings yet

- Co Kim Chan Vs Tan Keh 75 Phil 113Document1 pageCo Kim Chan Vs Tan Keh 75 Phil 113Jomar Teneza100% (1)

- People vs. DapitanDocument3 pagesPeople vs. DapitanDanica Irish RevillaNo ratings yet

- RespondantDocument30 pagesRespondantmanikaNo ratings yet

- 10th Semester Internal Class Moot MEMORIAL 2022Document24 pages10th Semester Internal Class Moot MEMORIAL 2022annuchauhanNo ratings yet

- LawFoyer SampleMemorial PDFDocument29 pagesLawFoyer SampleMemorial PDFhimakshi.studentNo ratings yet

- TC 008 - AppellantDocument26 pagesTC 008 - AppellantRISHI SHARMANo ratings yet

- Petitioner Nomc 3610 LloydDocument28 pagesPetitioner Nomc 3610 LloydLalitendu DebataNo ratings yet

- Petitioner TC-03Document25 pagesPetitioner TC-03arindam95461.amNo ratings yet

- CRPC Memo Sem 4 FinalDocument23 pagesCRPC Memo Sem 4 FinalHarsh MishraNo ratings yet

- 3 S - N D B M I O M C C I I L: RD MT Irmala EVI AM Emorial Nternational Nline OOT Ourt OmpetitionDocument28 pages3 S - N D B M I O M C C I I L: RD MT Irmala EVI AM Emorial Nternational Nline OOT Ourt OmpetitionSanket DasNo ratings yet

- RESPONDENTS Edited Final PRINTDocument23 pagesRESPONDENTS Edited Final PRINTLOLITA DELMA CRASTA 1950351No ratings yet

- NMCC 2019-07-PDocument41 pagesNMCC 2019-07-PkritzrockxNo ratings yet

- Final Petitioner MemorialDocument31 pagesFinal Petitioner MemorialTusharkant SwainNo ratings yet

- Petitioner Memorandum Final (Divya's Try)Document32 pagesPetitioner Memorandum Final (Divya's Try)Drishti TiwariNo ratings yet

- Respondent Nomc 3610 LloydDocument28 pagesRespondent Nomc 3610 LloydKrish100% (1)

- TC 008 - RespondentDocument26 pagesTC 008 - RespondentRISHI SHARMA0% (1)

- Respondent 119Document24 pagesRespondent 119SuseelaNo ratings yet

- Moot Case AppellantDocument25 pagesMoot Case AppellantSai Srija LAWNo ratings yet

- Before The Supreme Court of AmphissaDocument26 pagesBefore The Supreme Court of Amphissakomal100% (1)

- I T H ' H C J S: Sir Syed & Surana & Surana Ational Criminal Moot Court Law Competition 2018Document46 pagesI T H ' H C J S: Sir Syed & Surana & Surana Ational Criminal Moot Court Law Competition 2018Piyush jainNo ratings yet

- BIM/123 33 A I U M C C, 2017: RD LL Ndia Niversity OOT Ourt OmpetitionDocument18 pagesBIM/123 33 A I U M C C, 2017: RD LL Ndia Niversity OOT Ourt OmpetitionABINASH DASNo ratings yet

- Ab Chane MT KrnaDocument30 pagesAb Chane MT KrnaSHOURYANo ratings yet

- MC RespondentDocument24 pagesMC RespondentSai Srija LAWNo ratings yet

- Before: 2 N M C C, 2022Document28 pagesBefore: 2 N M C C, 2022ScribdNo ratings yet

- Rayat Memo TC A AppellantDocument42 pagesRayat Memo TC A AppellantKiran KNo ratings yet

- Respondent 31Document33 pagesRespondent 31Aman RajoriyaNo ratings yet

- Memorial Petitioner SideDocument25 pagesMemorial Petitioner Sidegeethu sachithanandNo ratings yet

- TC - K 1 Memorial For Appellant (Final)Document23 pagesTC - K 1 Memorial For Appellant (Final)muzammil shaikhNo ratings yet

- Defendant Memorial RJ-21Document31 pagesDefendant Memorial RJ-21Mandira PrakashNo ratings yet

- Krishna Singh, Speaker 1 - Petitioner SideDocument31 pagesKrishna Singh, Speaker 1 - Petitioner Sidekrishna singhNo ratings yet

- The Honorable High Court of Kalbari: BeforeDocument27 pagesThe Honorable High Court of Kalbari: BeforeRavi GuptaNo ratings yet

- PETITIONERDocument18 pagesPETITIONERRichaNo ratings yet

- The Legal Insider in Collaboration With I.E.C. University, Sol National Virtual Moot Court Competition, 2020Document34 pagesThe Legal Insider in Collaboration With I.E.C. University, Sol National Virtual Moot Court Competition, 2020Aman RajoriyaNo ratings yet

- Petitioner 1Document23 pagesPetitioner 1deepakkoranga12No ratings yet

- Constitution Moot Memo HarishDocument19 pagesConstitution Moot Memo HarishAbhinav Mehra100% (1)

- Memo Intra MootDocument26 pagesMemo Intra MootChhatreshNo ratings yet

- BCI Moot (Respondent)Document16 pagesBCI Moot (Respondent)NaveenNo ratings yet

- Clinical 2Document32 pagesClinical 2mohit kumarNo ratings yet

- Final MemoDocument27 pagesFinal MemoSanjeev0% (1)

- 1 B. P D M C C, 2016: I T H ' S C o IDocument5 pages1 B. P D M C C, 2016: I T H ' S C o IAnamika VatsaNo ratings yet

- Class Moot 1 - Akash 1735Document22 pagesClass Moot 1 - Akash 1735akash tiwariNo ratings yet

- fINAL MEM0 AppelleantDocument36 pagesfINAL MEM0 AppelleantSatyam Singh SuryavanshiNo ratings yet

- Memorial For Respondent AmityDocument27 pagesMemorial For Respondent AmityAnurag GuptaNo ratings yet

- Itm Moot Court PetitionerDocument34 pagesItm Moot Court PetitionerAbhishek SharmaNo ratings yet

- Moot EssDocument60 pagesMoot EssSai Srija LAWNo ratings yet

- Respondent Memo Moot 1Document29 pagesRespondent Memo Moot 1ANJALI BASKAR 1950446No ratings yet

- Petitioner (TC - 28)Document34 pagesPetitioner (TC - 28)Shreya Yadav100% (1)

- Amity Moot Respondent 1Document50 pagesAmity Moot Respondent 1Crazy MechonsNo ratings yet

- TC08 - Memorial For RespondentDocument25 pagesTC08 - Memorial For Respondenthc271105No ratings yet

- Petitioner NLC PuneDocument26 pagesPetitioner NLC Punepururaj singhNo ratings yet

- 10TH July R1Document23 pages10TH July R1Vipra VashishthaNo ratings yet

- Memorial PetitionerDocument38 pagesMemorial PetitionerchetanNo ratings yet

- BCI Moot (Petitioner) - Memo PunditsDocument16 pagesBCI Moot (Petitioner) - Memo PunditsVarun MatlaniNo ratings yet

- DraftDocument43 pagesDraftReddemma ChoudaryNo ratings yet

- Respondent Memo Moot 1Document23 pagesRespondent Memo Moot 1ANJALI BASKAR 1950446No ratings yet

- Criminal LawDocument26 pagesCriminal LawPranjal DarekarNo ratings yet

- Health Law Memorial - RespondentDocument18 pagesHealth Law Memorial - RespondentKrishNo ratings yet

- Imcc - T95 - Memorial For The PetitionerDocument27 pagesImcc - T95 - Memorial For The PetitionerjasminjajarefeNo ratings yet

- Memorial On The Behalf of Petitioner.Document29 pagesMemorial On The Behalf of Petitioner.SHOURYANo ratings yet

- Petitioner AugDocument28 pagesPetitioner AugmanikaNo ratings yet

- Case CommentDocument4 pagesCase CommentmanikaNo ratings yet

- DOE Patriae Powers in Providing Care To Its Citizens Who Are Unable To Care For Themselves."Document8 pagesDOE Patriae Powers in Providing Care To Its Citizens Who Are Unable To Care For Themselves."manikaNo ratings yet

- Express Newspapers v. Union of India AIR 1958, SC 578Document1 pageExpress Newspapers v. Union of India AIR 1958, SC 578manikaNo ratings yet

- Disaster Management Act 2005Document9 pagesDisaster Management Act 2005manikaNo ratings yet

- Petition Filed Under Article 32, Constitution of GEORGOPOL, WRIT PETITION NO. - /2020Document28 pagesPetition Filed Under Article 32, Constitution of GEORGOPOL, WRIT PETITION NO. - /2020manikaNo ratings yet

- ApporvPal PetitionerDocument34 pagesApporvPal PetitionermanikaNo ratings yet

- Versus: 2020 SCC Online SC 481 in The Supreme Court of IndiaDocument2 pagesVersus: 2020 SCC Online SC 481 in The Supreme Court of IndiamanikaNo ratings yet

- RespondantDocument30 pagesRespondantmanikaNo ratings yet

- (1 Lawschole Virtual Moot Court Competition, 2020) : (The Hon'Ble Supreme Court of Georgopol)Document20 pages(1 Lawschole Virtual Moot Court Competition, 2020) : (The Hon'Ble Supreme Court of Georgopol)manikaNo ratings yet

- 2014 Judgement 05-Mar-2019Document28 pages2014 Judgement 05-Mar-2019manikaNo ratings yet

- Reportable in The Supreme Court of India Criminal Appellate Jurisdiction Criminal Appeal No. 233 of 2010 Ude Singh & Ors. .Appellant (S) VSDocument34 pagesReportable in The Supreme Court of India Criminal Appellate Jurisdiction Criminal Appeal No. 233 of 2010 Ude Singh & Ors. .Appellant (S) VSmanikaNo ratings yet

- Case Commentary: The Quran, Ii: 29 The Quran, 2:228 and 2:241Document7 pagesCase Commentary: The Quran, Ii: 29 The Quran, 2:228 and 2:241manikaNo ratings yet

- Versus: Efore Anjay Ishan AULDocument31 pagesVersus: Efore Anjay Ishan AULmanikaNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Amendment Rules 2018Document14 pagesSupreme Court Amendment Rules 2018manikaNo ratings yet

- Chapter XVIII Deals With Offences Related To Documents and Property Marks. 463 of IPC Deals Fraudulently Purports To Be What It Is NotDocument1 pageChapter XVIII Deals With Offences Related To Documents and Property Marks. 463 of IPC Deals Fraudulently Purports To Be What It Is NotmanikaNo ratings yet

- CS (OS) No. 188/2016 Ashish Bhalla v. Suresh Chawdhary: Efore Ajiv Ahai NdlawDocument3 pagesCS (OS) No. 188/2016 Ashish Bhalla v. Suresh Chawdhary: Efore Ajiv Ahai NdlawmanikaNo ratings yet

- 499 ProsecutionDocument1 page499 ProsecutionmanikaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 157.39.12.51 On Mon, 06 Jul 2020 04:07:02 UTCDocument28 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 157.39.12.51 On Mon, 06 Jul 2020 04:07:02 UTCmanikaNo ratings yet

- It Act 67 EssentialsDocument58 pagesIt Act 67 EssentialsmanikaNo ratings yet

- Abetment To SuicideDocument14 pagesAbetment To SuicidemanikaNo ratings yet

- Law Commission's ReportDocument25 pagesLaw Commission's ReportmanikaNo ratings yet

- Am No. 12-8-8-SCDocument2 pagesAm No. 12-8-8-SCcrizaldedNo ratings yet

- C.A PHC Apn 18 - 2017 PDFDocument8 pagesC.A PHC Apn 18 - 2017 PDFHit MediaNo ratings yet

- Manila Surety and Fidelity Co. Vs TeodoroDocument5 pagesManila Surety and Fidelity Co. Vs TeodoroDoni June AlmioNo ratings yet

- Art 23, Family Code Proof of Marriage Presumption of Marriage People V. BorromeoDocument25 pagesArt 23, Family Code Proof of Marriage Presumption of Marriage People V. BorromeoErnest Talingdan CastroNo ratings yet

- Case Study CPCDocument12 pagesCase Study CPCMalika100% (1)

- Through Ultan's Door Presents Beneath The Moss CourtsDocument46 pagesThrough Ultan's Door Presents Beneath The Moss CourtsИван ПолуэктовNo ratings yet

- Chrysler Group LLC V LKQ Corp - ComplaintDocument177 pagesChrysler Group LLC V LKQ Corp - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Filipinas Compania de Seguros V HuenefeldDocument3 pagesFilipinas Compania de Seguros V HuenefeldSean GalvezNo ratings yet

- Mateo Vs DARDocument2 pagesMateo Vs DARxeileen080% (1)

- Texas Juvenile Law 9Document758 pagesTexas Juvenile Law 9Joj CastroNo ratings yet

- Cornejo V GabrielDocument15 pagesCornejo V GabrielMc Alaine LiganNo ratings yet

- People V Villanueva Case DigestDocument3 pagesPeople V Villanueva Case Digestabcyuiop78% (9)

- 26 Fontanilla Vs MaliamanDocument5 pages26 Fontanilla Vs MaliamanArmand Patiño AlforqueNo ratings yet

- Persons and Family Relations-PrelimsDocument205 pagesPersons and Family Relations-PrelimsMary NoveNo ratings yet

- Rice Magazine Fall 2005Document56 pagesRice Magazine Fall 2005Rice UniversityNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 132887 - The Manila Banking Corp. v. SilverioDocument12 pagesG.R. No. 132887 - The Manila Banking Corp. v. SilverioJonah NaborNo ratings yet

- Lethics MCQDocument27 pagesLethics MCQmjpjoreNo ratings yet

- NYAMENEBA AND OTHERS v. THE STATE (1965) GLR 723-729Document4 pagesNYAMENEBA AND OTHERS v. THE STATE (1965) GLR 723-729Christiana AbboseyNo ratings yet

- Jurisprudence On Breach of ContractDocument2 pagesJurisprudence On Breach of ContractJeffrey Garcia Ilagan100% (1)

- 01 Pacific Banking Corporation Employees Organization vs. Court of AppealsDocument10 pages01 Pacific Banking Corporation Employees Organization vs. Court of AppealsJoana Arilyn CastroNo ratings yet

- Hanumant - Civil Procedure Code Notes Hanumant - Civil Procedure Code NotesDocument3 pagesHanumant - Civil Procedure Code Notes Hanumant - Civil Procedure Code NotesIshikaNo ratings yet

- Certificate of Insurance: Patriot America PlusDocument24 pagesCertificate of Insurance: Patriot America PlusKARTHIK145No ratings yet

- Walter Wells LTD V Wilson Samuel Jackson 1984Document6 pagesWalter Wells LTD V Wilson Samuel Jackson 1984talk2marvin70No ratings yet

- Suits by or Against GovernmentDocument11 pagesSuits by or Against Governmentad_coelum100% (5)

- 6VDA DE BORROMEO Vs POGOYDocument2 pages6VDA DE BORROMEO Vs POGOYfermo ii ramosNo ratings yet

- Zamora-Alvarez v. United States of America - Document No. 4Document1 pageZamora-Alvarez v. United States of America - Document No. 4Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Lico vs. ComelecDocument5 pagesLico vs. ComelecMarian's PreloveNo ratings yet

- PS Prods. v. ContextLogic - ComplaintDocument21 pagesPS Prods. v. ContextLogic - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet