Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Making Sense of Public Issues With Songs: January 2016

Making Sense of Public Issues With Songs: January 2016

Uploaded by

arreeOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Making Sense of Public Issues With Songs: January 2016

Making Sense of Public Issues With Songs: January 2016

Uploaded by

arreeCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/308873896

Making sense of public issues with songs

Article · January 2016

CITATIONS READS

0 449

2 authors, including:

James Howell

University of Southern Mississippi

9 PUBLICATIONS 30 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

The Bridging Divides Project View project

The Plowing Freedom's Ground Project View project

All content following this page was uploaded by James Howell on 24 February 2017.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Social Studies Research and Practice

www.socstrp.org

Making Sense of Public Issues with Songs

James B. Howell

The University of Southern Mississippi

Cory Callahan

The University of Alabama

Arguments surrounding public issues are not always expressed in writing; they often take visual

and auditory forms. In recent years, scholarship encouraging teachers and students to think

deeply about songs—music and lyrics—has increased. Historical analysis of songs from the past

can help students develop critical listening habits useful for interpreting contemporary songs.

We share an inquiry-based, research-into-practice lesson centered around the following question:

Was the US justified in pursuing nuclear weapons following the conclusion of World War II?

We highlight a public issues approach where students use historical content and analysis as

evidence to defend a chosen public policy.

Key words: Public Issues, Music Literacy, Historical Thinking, Inquiry-Based

Instruction, Civic Competence

Like many living in America, we grew up playing instruments and listening to an eclectic

mix of music: jazz, hard rock, pop, hip-hop, country, etc. In the searching times of adolescence,

we were drawn to musicians who used their considerable artistic abilities to comment on social

issues. Metallica’s One (Hetfield & Ulrich, 1989) invited us to explore returning home mangled

from war, Arrested Development’s Mr. Wendal (Todd, 1992) compelled us to consider

homelessness in our communities, and Nirvana’s Smells Like Teen Spirit (Cobain, Noroselic, &

Grohl, 1991) challenged us to rethink conformity and social acceptance.

Students of all ages are likely to have similar experiences, with an important exception:

today, songs are far more accessible. Whereas we had to wait for a song to cycle through its

rotation on the radio or visit a store, students can now access almost any song within seconds.

Music stars release singles via well-known multimedia software applications and amateur singer-

songwriters upload high-quality original creations on social media. Digital music is available for

near-instant download across multiple platforms, all of which are available at students’

fingertips. This availability may partially explain why teenagers (and tweens) now listen to

music an average of 2.5 hours per day, an increase of nearly 40% from a decade ago (see

Rideout, Foehr, & Roberts, 2010).

Students tend to listen to songs delivering powerful messages and providing commentary

on popular culture (Buckingham, 2003; Luke, 2000), and it is often through listening to those

songs that students construct opinions on social issues (Mangram & Weber, 2012). It seems

reasonable, therefore, that independent participation in our increasingly digitized democracy

requires increased media literacy to help establish a healthy distance from powerful influences

(Silverblatt, Smith, Miller, Smith, & Brown, 2014). Competence in media literacy would afford

citizens agency to choose which media to access, the ability to interpret their selections, and the

reflective judgment to evaluate them (Brkich, 2012; Wineburg & Reisman, 2015). In this article,

we describe how thinking deeply about the powerful messages found in songs from the past can

help students develop critical listening habits useful for interpreting contemporary songs. We

Volume 11 Number 2 80 Summer 2016

Social Studies Research and Practice

www.socstrp.org

also suggest situating the analysis of songs from the past in the context of a persistent public

issue (Saye & Brush, 2004) increases the likelihood students will grasp the modern significance

of their analytical findings.

In contrast to their lives away from school, adolescents in social studies classrooms rarely

explore social commentaries built from music and lyrics (White & McCormack, 2006).

Teachers’ classroom practices tend to exclude potentially powerful instruction featuring songs as

primary sources (Root, 2005). We believe students can develop the disposition to transfer skills

of critical audio consumption (e.g., sourcing, contextualizing, constructing arguments) by

interpreting historical and contemporary music (White & McCormack, 2006, see also Wineburg,

2003) within the context of persistent social issues that intersect both time and space (Saye &

Brush, 2004). Historical music, in particular, may create much needed cognitive space for

students to explore questions about the past while recognizing artists’ assumptions about the

world. Historical songs can 1) present opportunities for students to question truth claims, 2) add

contextual depth to help students make sense of the past, and 3) help students recognize that tone

and rhythm often buttress social arguments made through lyrics.

A Public Issues Framework

Social studies approaches that implement songs as historical artifacts tend to develop

students’ interpretive skills or students’ understanding of under-represented perspectives (see

Heafner, Groce, & Bellows, 2014). Surely, these goals should be considered. We seek to tie the

examination of historical songs to a public issues framework, thus aiding students in developing

civic competence (see Oliver & Shaver, 1966). Research over the past 30 years has consistently

suggested teaching social studies within a public issues framework can help students refine the

skills, knowledge, and dispositions needed for a productive civic life (Hess, 2002; Oliver,

Newmann, & Singleton, 1992; Parker, 2006; Saye & Brush, 2004). Active democratic

citizenship requires an understanding of cultures, politics, economics, and attempts to manipulate

one’s personal decisions (Peck 2005). Students who develop the skills associated with civic

competence—the knowledge, intellectual processes, and democratic dispositions required of

students to be active and engaged participants in public life (National Council for the Social

Studies, 2010)—may be better prepared to critique information regarding complex issues and act

according to their well-informed consciences.

In advocating for the examination of historical songs within a public issues framework, we

sought to provide students with experiences in reasoning through social issues and conflicts

typical of democracies. Students need practice analyzing the competing perspectives and

evidence inevitably arising when working through controversial public issues in a democratic

society. Students also need practice making and defending reasonable resolutions to these

issues. We suggest music and lyrics hold educative potential beyond making social studies

classes more engaging (White & McCormack, 2006) or helping “students learn to think like

historians” (Library of Congress, 2015, para. 1). Songs can be used as resources to develop and

hone powerful analysis tools for negotiating auditory data (i.e., music and lyrics), weighing

value-conflicts, and deriving solutions to public issues.

We featured a lesson employing historical songs as evidence that students analyzed and

used to address a public issue. We situated the lesson within a post-World War II unit asking an

authentic question upon which reasonable people of good will disagreed: Was the US justified in

pursuing nuclear weapons following the conclusion of World War II? The question’s

pedagogical significance hinges on the word justified; rather than asking students to explain how,

Volume 11 Number 2 81 Summer 2016

Social Studies Research and Practice

www.socstrp.org

it asks whether the nation acted justly. The question required students to identify and explore

historical evidence as a means to an end: making value judgments as to the justness of foreign

policy decisions immediately after World War II. The authentic question is also a manifestation

of a larger, more enduring societal concern: What actions are justified when securing the welfare

or security of a community? (Newmann, 1970; Saye & Brush, 2004). We suggest the use of this

persistent question within our curricular materials brings more contemporary significance to the

examination of Cold War era historical songs. By calling for students to justify actions, both

questions encouraged reflective inquiry that moved beyond transmitting historical content or

practicing the tools of inquiry embedded within the social science disciplines (see Barr, Barth, &

Shermis, 1978). The questions also asked students to explore justice-oriented themes by

analyzing collective strategies that attempted to resolve social issues (see Westheimer & Kahne,

2004).

We also designed an advanced organizer (Appendix A) to carefully scaffold students’

interpretation of historical songs. To create the handout, we synthesized research-based

suggestions for 1) recognizing, deconstructing, and “evaluating” an argument (see NCSS, 2013,

C3 Framework, Dimension 3, p. 18), 2) thinking critically and historically about evidence from

the past (see Wineburg, 1991; Wineburg, Martin, & Monte-Sano, 2013; Wineburg, & Reisman,

2015), and 3) thinking deeply about songs’ “unique artistic characteristics” (Library of Congress,

2015, para. 1). Appendix B is a completed scaffold that may be a useful resource for teachers as

they facilitate students’ historical thinking.

An Exemplar Lesson: Reactions to Nuclear Proliferation following World War II

The lesson featured below was nested within a unit designed to help students decide if the

US was justified in pursuing nuclear weapons following the conclusion of World War II. Each

of the unit’s lessons worked to assist students in developing the knowledge and skills required to

answer the unit central question in a culminating activity. At the end of the unit, student-groups

prepared and delivered a persuasive presentation to the American people within the historical

context of SALT I negotiations taking place between the United States and the Soviet Union.

Throughout instruction, we used technology to address anticipated obstacles students would

encounter related to studying history within a public issues framework. In the lesson below, for

example, we added contextual hyperlinks within our digital presentation of each historical song

to provide historical expertise and metacognitive aides to students’ thinking (see Land, 2000;

Saye & Brush, 2004).

During an initial introductory lesson grabber concerning value conflicts surrounding a

modern military dispute, we emphasized that the skills to be sharpened during the unit were

essential for thoughtful 21st century civic life. We reminded students there are people or groups

who intentionally use auditory messages (e.g., songs, anthems, jingles) to influence their

decision-making. We shared with students that they would soon think deeply about songs, using

them as evidence to hypothesize about the past. We stressed our hope was for students to

develop the disposition to transfer those newly honed skills and use them to improve their lives

away from school. We then introduced an authentic, real-world scenario framing the unit’s

culminating activity: student-pairs had been hired by an U.S. special interest group to develop an

evidence-based, persuasive speech to convince the public of their position on the question of

nuclear weapons following the conclusion of World War II. We emphasized that persuasive

speechwriters usually address their opponents’ arguments; therefore, analysis of multiple

perspectives was crucial.

Volume 11 Number 2 82 Summer 2016

Social Studies Research and Practice

www.socstrp.org

Next, we provided foundational knowledge of the early Cold War years through an

interactive lecture. Topics we covered included: the dropping of atomic bombs on Japan, post-

World War II peace conferences, the Marshall Plan, NATO, the Warsaw Pact, the nuclear arms,

the space race, and a very brief overview of several Cold War proxy conflicts.

Then, we directed student-pairs to complete an online song analysis activity using four

Cold War songs as historical sources. We selected songs based on their 1) musical and lyrical

richness, 2) human interest, and 3) ability to provide divergent views on the question of nuclear

proliferation. Two songs supported U.S. efforts to develop and use nuclear weapons following

the end of World War II; two different songs highlighted the dangers of nuclear proliferation.

Because of space limitations, below we feature and discuss only one song from each perspective.

Our unit was conceptualized using the unit framework advocated by the Persistent Issues

in History (PIH) Network (see Saye & Brush, 2004). The PIH Network is a community of

skilled teachers who engage their students in problem-based historical inquiry (e.g., critically

weighing evidence for historical claims, using content knowledge generated from sound

historical analysis to inform decisions about enduring societal questions). The PIH unit

framework encourages teachers to plan backwards by identifying a persistent issue question and

a related topic-specific, unit central question before then conceptualizing an authentic

performance assessment that creates opportunities for students to defend answers to both

questions. We created this lesson online within the PIH Network website (Persistent Issues in

History, 2015) and used the site’s authoring tools to assist students in their analysis. We

provided hyperlinked scaffolding to accompany each song’s lyrics. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate

scaffolded web-interfaces we created for students. We also distributed to each student an

advanced organizer (Appendix A).

Volume 11 Number 2 83 Summer 2016

Social Studies Research and Practice

www.socstrp.org

Figure 1. PIH Network scaffolded interface design for “Atom and Evil.”

Just before encouraging students to begin their analysis of the historical songs, we

reviewed the following logistical steps. We asked students to:

1) plug in their headphones and independently listen to the songs while reading

along with the lyrics,

2) pay careful attention to the tone, melody, and word-choices (lyrics);

3) re-read the lyrics with their partner, making use of the embedded scaffolding;

and

4) complete the advanced organizer as they worked through each song and after

analyzing each set.

Students first analyzed the songs opposed to nuclear proliferation following the end of

World War II: Atom and Evil (Zaret & Singer, 1947) and Atomic Sermon (Hughes, 1953). Here,

we feature Atom and Evil, performed by The Golden Gate Quartet, an African-American gospel

group. The song is metaphorically grounded in the Judeo-Christian allegory in which Eve

convinced Adam to eat fruit from the forbidden tree against God’s will, resulting in humanity’s

fall from grace and the origination of sin in the world (Genesis Ch. 3, New Revised Standard

Version). The song portrays Atom (i.e., the atomic bomb) as innocent, but warns humanity

Volume 11 Number 2 84 Summer 2016

Social Studies Research and Practice

www.socstrp.org

would be destroyed if Atom were to unite with an unspecified Miss Evil. In this sense, the bomb

is portrayed as an amoral object by itself, yet dangerous and evil when placed in the wrong

hands. By the conclusion of the song, the quartet calls for society to prevent the atomic bomb

from getting into Evil’s hands because doing so was the only way to prevent human destruction.

Musically, The Golden Gate Quartet uses a jubilee style with close harmonies and restrained

singing but with strong musical technique. It seems the singer-songwriters wanted to appeal to a

broad audience and thus juxtaposed the serious, almost spiritual, lyrics with a playful tempo and

tone. Students who analyze Atom and Evil should grasp its warnings against nuclear

proliferation and infer that the song likely reflected the sentiments of the quartet’s similarly

concerned contemporaries (see Appendix B for a complete analysis of the song with anticipated

student responses).

Figure 2. PIH Network scaffolded interface design for “When They Drop the Atomic Bomb.”

Students next analyzed the two songs supporting the development or use of nuclear

weaponry following the end of World War II: When They Drop the Atomic Bomb (Howard,

1951) and Dawn of Correction (Madara, White, & Gilmore, 1965). We feature When They Drop

the Atomic Bomb. Very little is known about the song’s singer, Jackie Doll. He recorded only

Volume 11 Number 2 85 Summer 2016

Social Studies Research and Practice

www.socstrp.org

six songs before disappearing from the music scene. The song, however, calls for the destruction

of America’s communist enemies, using any means necessary, including nuclear weapons, and is

among the clearest appeals for the use of nuclear weapons during the Cold War (i.e., the Korean

conflict). The song champions General Douglas MacArthur, commander of UN operations on

the Korean peninsula. It describes an U.S. atomic first-strike that would destroy the communist

North Koreans while simultaneously sending a strong message to Joseph Stalin that he would not

be allowed to expand Soviet influence. Musically, the song has an upbeat, country-western

tempo and tone that one might expect to find at a barn dance (a genre popular at the time). In

this sense, the musical setting seems to minimize the overtness with which the singer-songwriters

call for preemptive use of the atomic bomb to stop the spread of communism. Students who

analyze When They Drop the Atomic Bomb should conclude that it represents a more

conservative Cold War perspective and that the song was likely intended to strengthen the

position of those U.S. citizens who favored strong action in North Korea (see Appendix B for a

complete analysis of the song with anticipated student responses).

Throughout students’ efforts to analyze the songs, we worked to scaffold their

understanding by prompting student pairs for more details, by problematizing trivial thinking,

and by providing students with additional historical context to consider. During these

spontaneous conversations, after students had first independently considered each song’s music

and tone, we used soft scaffolding to introduce additional details about the musical genres

reflected in each song. We also identified gaps in students’ advanced organizers, corrected

ahistorical assumptions, and invited students to revisit the songs for additional details. After the

student-pairs analyzed and discussed the songs, we asked them to tentatively address the unit

central question. We encouraged students to pool their foundational knowledge from the lecture

and song analysis, then offer evidence-based answers to: “Was the US justified in pursuing

nuclear weapons following the conclusion of World War II?” We facilitated a whole-class

discussion that encouraged students to draw from their contextual knowledge of the time period

presented in the lecture and the competing historical perspectives embedded in the songs. To

close, we reiterated how the media literacy skills practiced in the lesson (i.e., thinking critically

about auditory data) had great value in students’ everyday lives as democratic citizens. We also

reminded students of the culminating activity and indicated that their speech would require them

to recognize perspectives (Barton & Levstik, 2004) before arguing their evidence-based view on

the unit question.

Conclusion

Arguments surrounding public issues are not always expressed in writing; they often take

visual and auditory forms. In recent years, encouraging students to think deeply about the latter

expression, in the form of music and lyrics, has increased (see Brkich, 2012; Heafner, et al.,

2014; Heafner, Groce, & Finnell, 2014; Mangram & Weber, 2012; Pellegrino, Adragna, &

Zenkov, 2015; Soden & Castro, 2013). While many social studies teachers use music to engage

students, they tend to underutilize songs as powerful pedagogical resources (Heafner, et al.,

2014, p. 265). The Cold War lesson we presented offers the opportunity for students to use

information from the past to better understand an enduring societal concern. Students’ efforts

were scaffolded to include critical and historical analysis of songs from the era in order to

construct a more robust understanding of the context surrounding the use of nuclear weapons. In

particular, the analysis of Cold War songs provided students with an understanding of multiple

Volume 11 Number 2 86 Summer 2016

Social Studies Research and Practice

www.socstrp.org

historical perspectives that students are to first assess and then use in support of a position on an

overarching authentic, public issue.

We contend that analysis of historical songs within a public issues framework encourages

students to question truth claims while adding contextual depth to help students make sense of

the past. In our lesson, students analyzed songs presenting competing perspectives on a public

issue: whether the US was justified in pursuing nuclear weapons following the conclusion of

World War II. Students were not given a single, celebratory narrative covering U.S. Cold War

actions but were asked to use historical evidence to take a position on an important policy issue

from the past that emerges even today. The competing perspectives built into the lesson were

offered by musicians and represented important attempts by artists to persuade the wider U.S.

public on the appropriateness of developing and using nuclear weaponry. We argue the

musicians’ efforts to persuade or inform were made more palatable for the public through their

use of easily recognizable tones and rhythms. In the songs featured, for instance, we suggest that

the songwriters used popular country-western and jubilee musical settings to appeal to a wider

public audience even as they sung about serious societal concerns.

We hope the research-based lesson presented further encourages wise use of songs:

framed by disciplined-inquiry, contextualized within a public issue, and marked by critical and

historical thinking. We believe this lesson will help further develop the skills necessary for

students to become active citizens.

References

Barr, R., Barth, J., & Shermis, S. (1978). The nature of the social studies. Palm Springs,

CA: ETC Publications.

Barton, K., & Levstik, L. (2004). Teaching history for the common good. Mahwah, NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Brkich, C. (2012). Music as a weapon: Using popular culture to combat social injustice. The

Georgia Social Studies Journal, 2(1), 1-9.

Buckingham, D. (2003). Media education: Literacy, learning, and contemporary culture. Polity

Press in association with Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Cobain, C., Novoselic, K., & Grohl, D. (1991). Smells like teen spirit. Nevermind [CD]. Santa

Monica: CA. DGC Records.

Heafner, T., Groce, E., & Bellows, E. (2014). Exploring the complexity of music and the utility

of digital access to understand the past. In W. B. Russell III (Ed.), Digital Social Studies

(pp. 243-267).

Heafner, T., Groce, E., & Finnell, A. (2014). Springsteen's Born in the U.S.A.: Promoting

historical inquiry through music. Social Studies Research & Practice, 9(3), 118-138.

Hess, D. (2002). Discussing controversial public issues in secondary social studies classrooms:

Learning from skilled teachers. Theory & Research in Social Education, 30(1), 10-41.

Hetfield, J., & Ulrich, L. (1989). One [Recorded by Metallica]. On And justice for all [CD]. New

York, NY: Elektra Records.

Howard. (1951). When they drop the atomic bomb [Recorded by Jackie Doll and his Pickled

Peppers]. On When they drop the atomic bomb / Get me a ticket on the Wabash

Cannonball [LP]. Mercury Records.

Hughes, B. (1953). Atomic sermon [Recorded by Billy Hughes and his Rhythm Buckeroos]. On

Atomic sermon / Beside the Alamo [LP]. Space Records.

Volume 11 Number 2 87 Summer 2016

Social Studies Research and Practice

www.socstrp.org

Land, S. M. (2000). Cognitive requirements for learning with open-ended learning environments.

Educational Technology Research and Development, 48(3), 61-78.

Luke, C. (2000). Cyber-schooling and technological change: Multiliteracies for new times. In B.

Cope & M. Kalantzis (Eds.), Multiliteracies: Literacy, learning & the design of social

futures (pp.69-105). Melbourne, Australia: MacMillan.

Madara, J., White, D., & Gilmore, R. (1965). Dawn of correction [Recorded by The

Spokesmen]. On The dawn of correction [LP]. Decca Records.

Mangram, J., & Weber, R. (2012). Incorporating music into the social studies classroom: A

qualitative study of secondary social studies teachers. Journal of Social Studies Research,

36(1).

National Council for the Social Studies. (2010). National curriculum standards for social

studies: A framework for teaching, learning and assessment. National Council for the

Social Studies. Washington, D.C.

National Council for the Social Studies. (2013). The college, career, and civic life (C3)

framework for the social studies state standards: Guidance for enhancing the rigor of K-

12 civics, economics, geography, and history. Silver Springs, MD.

Newmann, F. (1970). Clarifying public controversy: An approach to teaching social studies.

Boston: Little Brown.

Oliver, D., Newmann, F., & Singleton, L. R. (1992). Teaching public issues in the secondary

school classroom. The Social Studies, 83, 101-103.

Oliver, D., & Shaver, J. (1966). Teaching public issues in the high school. Boston: Houghton

Mifflin.

Parker, W. (2006). Public discourses in schools: Purposes, problems, possibilities. Educational

Researcher, 35(8), 11-18.

Peck, C. (2005). Introduction to the special edition of Canadian social studies: New approaches

to teaching history. Canadian Social Studies, 39(2).

Pellegrino, A., Adragna, J., & Zenkov, K. (2015). Using the power of music to support students'

understanding of fascism. Social Studies Research and Practice, 10 (67-72).

Root, D. (2005). Music as a cultural mirror. Magazine of History, 19(4), 7-8.

Saye, J., & Brush, T. (2004). Promoting civic competence through problem-based history

learning environments. In G. E. Hamot & J. J. Patrick (Eds.), Civic learning in teacher

education (Vol. 3, pp. 123-145). Bloomington, Indiana: The Social Studies Development

Center of Indiana University.

Silverblatt, A., Miller, D. C., Smith, J., & Brown, N. (2014). Media literacy: Keys to interpreting

media messages: ABC-CLIO.

Soden, G., & Castro, A. (2013). Using contemporary music to teach critical perspectives of war.

Social Studies Research & Practice, 8(2).

Todd, T. (1992). Mr. Wendal [Recorded by Arrested Development]. On 3 Years, 5 Months & 2

Days in the Life Of... [CD]. London: EMI/Chrysalis Records.

Westheimer, J., & Kahne, J. (2004). What kind of citizen? The politics of educating for

democracy. American educational research journal, 41(2), 237-269.

White, C., & McCormack, S. (2006). The message in the music: Popular culture and teaching in

social studies. The Social Studies, 97(3), 122-127.

Volume 11 Number 2 88 Summer 2016

Social Studies Research and Practice

www.socstrp.org

Wineburg, S. (1991). Historical problem solving: A study of the cognitive processes used in the

evaluation of documentary and pictorial evidence. Journal of Educational Psychology,

83, 73-87.

Wineburg, S. (2003). Teaching the mind good habits. Chronicle of Higher Education, 49(31), 20.

Wineburg, S., Martin, D., & Monte-Sano, C. (2012). Reading like a historian: Teaching literacy

in middle and high school history classrooms. Teachers College Press.

Wineburg, S., & Reisman, A. (2015). Disciplinary literacy in history. Journal of Adolescent &

Adult Literacy, 58(8), 636-639.

Zaret, H., & Singer, L. (1947). Atom and Evil [Recorded by Golden Gate Quartet]. On Atom and

Evil [Vinyl]. Columbia.

Web-based References

Library of Congress. (2015). Library of Congress: Song and Poetry Analysis Tools.

Retrieved from http://www.loc.gov/teachers/lyrical/tools

Persistent Issues in History. (2015). The Persistent Issues in History Network. Retrieved

from http://pihnet.org

Rideout, V., Foehr, U., & Roberts, D. (2010). Generation M2: Media in the lives of 8-18 year

olds. A Kaiser Family Foundation study. Retrieved from

http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED527859.pdf

Appendix A

Advanced organizer for students to complete during the lesson

Your Tasks: Listen for common conventions artists use to convey their message: pace, volume, tone,

and mood as well as its use of alliteration, imagery, simile/metaphor, parallelism, repetition, rhyme,

hyperbole, symbolism, and choice of language. Remember we are making sense with songs to help

answer the central question: Was America justified in pursuing nuclear weapons following the

conclusion of World War II?

The Golden Gate Quartet Jackie Doll. (1951) When

(1947). Atom and Evil They Drop the Atomic Bomb

Source

What does the song’s Date

suggest?

Who are the song’s Creators

and why might they be unable

or unwilling to be fully

objective (Bias)?

What important allusions or

connotations are found in the

Title?

Volume 11 Number 2 89 Summer 2016

Social Studies Research and Practice

www.socstrp.org

Context

List three aspects of the song

that seem important.

What role does the music

play? Is it loud, soft, flowing,

clunky?

After experiencing the song,

how is the audience supposed

to feel?

What do the above findings

suggest to you about the

song’s purpose?

Corroborate & Think Deeply

How do these songs work

together?

Why are there similarities or

differences?

How they help us begin to

answer the central question?

Appendix B

Completed Advanced organizer for teacher

Was America justified in pursuing nuclear weapons following the conclusion of World War II?

The Golden Gate Quartet (1947). Jackie Doll. (1951). When They

Atom and Evil Drop the Atomic Bomb

Source The song was released after World The song was released during the

War II but before the Soviets Korean War, a Cold War conflict.

developed their own nuclear bomb. America was at war.

The song was sung by a popular Black Little is known about the

quartet. They may have been most performer but as a country-

interested in selling records. western artist, he may have had

The title refers to the story of Adam & traditional, or conservative views.

Eve in the Bible. The whole song is The title is “when” they drop the

grounded in that Biblical narrative. bomb, not “if.” The “they” is the

United States so it seems like the

title approves of using the bomb

to root out communism.

Volume 11 Number 2 90 Summer 2016

Social Studies Research and Practice

www.socstrp.org

Context The song warns that Atom and Evil The song clearly supports General

should not be united – that the atom MacArthur and his fight against

bomb should not get into evil hands. communism. The song paints

It is clear that humanity’s fate rests in communists as evil and violent

ensuring close control of atomic who need to be destroyed, even

bombs. The song doesn’t offer any with atomic weapons.

way to ensure its aim. The song is upbeat and has a

The music is jubilee style with close country-western theme. The

harmonies and technical singing in the playfulness of the music seems to

context of a spiritual with a rhythmic soften the harsh tone taken against

beat. The seriousness of the lyrics is communists and its endorsement

made more palatable by using a for preemptively using the bomb.

playful tempo and tone that would The song might have been

resonate with broader audiences. intended to strengthen

The song might have been intended to conservative support for

warn people against nuclear MacArthur in Korea or as

proliferation but in a way that didn’t propaganda against the

scare the audience. communists.

Corroborate The songs provide opposite perspectives on the atomic bomb. These

& perspectives probably reflected two sides in American public opinion.

Think The similarities are musical – they both seem to soften the seriousness of the

Deeply lyrics by using playful music. The differences are lyrical, which might be due

to the intended audiences for each song.

The two songs work together to explore the pros and cons to developing

nuclear weapons. On the one hand, the bombs strengthen America’s position

against the communists. On the other hand, they kill innocent people and

could destroy the world.

Author Bios

James Howell is Assistant Professor of Secondary Education at The University of Southern

Mississippi. His research interests include lesson study professional development with in-service

social studies teachers, problem-based geographic and historical inquiry, and the culture of

schooling. Email: james.b.howell@usm.edu

Cory Callahan is Assistant Professor of Secondary Social Studies Education at The University

of Alabama. His research interests include educative curriculum materials, public issues, and

historical thinking about various historical texts including historical photographs and songs.

Volume 11 Number 2 91 Summer 2016

View publication stats

You might also like

- Guitar Books CollectionDocument2 pagesGuitar Books CollectionSheng Zhang50% (10)

- Democratic Schools - Beaneapple95Document18 pagesDemocratic Schools - Beaneapple95Juan PérezNo ratings yet

- Event AuditDocument11 pagesEvent AuditMai NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Star Ocean First Departure - GuideDocument40 pagesStar Ocean First Departure - GuideLucianaBelenAsteita100% (7)

- Wineburg+y+Reisman +teaching+the+skill+of+contextualizing+in+historyDocument7 pagesWineburg+y+Reisman +teaching+the+skill+of+contextualizing+in+historyHrpozasNo ratings yet

- Digital Booklet - Word ShakerDocument7 pagesDigital Booklet - Word ShakerMonokaea SilphNo ratings yet

- The National Music Artist of The PhilippinesDocument38 pagesThe National Music Artist of The PhilippinesKristel Gail Basilio100% (1)

- 2690-Article Text-14308-1-2-20220422Document13 pages2690-Article Text-14308-1-2-20220422api-608098430No ratings yet

- Introduction: Music and Media Infused Lives: Music Education in A Digital AgeDocument33 pagesIntroduction: Music and Media Infused Lives: Music Education in A Digital AgeMuhamadRifkiAdinurZeinNo ratings yet

- (2002) Morrell - Toward A Critical Pedagogy of Popular Culture Literacy Development Among Urban YouthDocument7 pages(2002) Morrell - Toward A Critical Pedagogy of Popular Culture Literacy Development Among Urban Youthcharlee1008No ratings yet

- Public History and The Study of Memory Author(s) : David GlassbergDocument18 pagesPublic History and The Study of Memory Author(s) : David GlassbergRaiza BaezNo ratings yet

- Music As A Means of Social Justice Course Proposal 1Document9 pagesMusic As A Means of Social Justice Course Proposal 1api-371696606No ratings yet

- Critical Ethnography ThesisDocument8 pagesCritical Ethnography ThesisCheapPaperWritingServicesMobile100% (2)

- La Historia PublicaDocument18 pagesLa Historia PublicaGloria AyalaNo ratings yet

- What Does It Mean To Decolonise The School Music Curriculum?Document12 pagesWhat Does It Mean To Decolonise The School Music Curriculum?Ying ShiNo ratings yet

- Community Music EducationDocument21 pagesCommunity Music EducationinfoNo ratings yet

- The Reconstruction Era and The Fragility of DemocracyFrom EverandThe Reconstruction Era and The Fragility of DemocracyNo ratings yet

- The Musicological Elite: Tamara LevitzDocument72 pagesThe Musicological Elite: Tamara LevitzJorge BirruetaNo ratings yet

- Palin/Pathos/Peter Griffin: Political Video Remix and Composition PedagogyDocument17 pagesPalin/Pathos/Peter Griffin: Political Video Remix and Composition PedagogyAllison De FrenNo ratings yet

- Music Sociology: Getting The Music Into The Action: TiadenoraDocument13 pagesMusic Sociology: Getting The Music Into The Action: TiadenoraOtilia VaniliaNo ratings yet

- Cpo 6077 OdwyerDocument5 pagesCpo 6077 OdwyerMandingo XimangoNo ratings yet

- Religion and Media: Syllabi & PedagogyDocument33 pagesReligion and Media: Syllabi & Pedagogygreg_perreaultNo ratings yet

- Formal Studies of Culture: Issues, Challenges and Current TrendsDocument15 pagesFormal Studies of Culture: Issues, Challenges and Current TrendsAkhtar Ali QaziNo ratings yet

- Sociological Approaches To The Pop Music Phenomenon: American Behavioral Scientist January 1971Document19 pagesSociological Approaches To The Pop Music Phenomenon: American Behavioral Scientist January 1971h o t s p i c yNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Civil Rights BLMDocument3 pagesLesson Plan Civil Rights BLMapi-653723755No ratings yet

- Module 2 Reading - Ross, 2006 PDFDocument20 pagesModule 2 Reading - Ross, 2006 PDFMacky AguilarNo ratings yet

- SS CurriculumDocument17 pagesSS Curriculummuhamad.wildan33410No ratings yet

- Critical Analysis in EducationDocument52 pagesCritical Analysis in EducationIrisha AnandNo ratings yet

- Children and Media A Cultural Studies ApproachDocument29 pagesChildren and Media A Cultural Studies ApproachMatheus VelasquesNo ratings yet

- The End of Consensus: Diversity, Neighborhoods, and the Politics of Public School AssignmentsFrom EverandThe End of Consensus: Diversity, Neighborhoods, and the Politics of Public School AssignmentsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- This Content Downloaded From 154.59.124.166 On Mon, 05 Apr 2021 16:34:04 UTCDocument13 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 154.59.124.166 On Mon, 05 Apr 2021 16:34:04 UTCJoão ReisNo ratings yet

- Media Studies Evolution and PerspectivesDocument12 pagesMedia Studies Evolution and Perspectivesbahas065.307No ratings yet

- Reflections On The National History StandardsDocument4 pagesReflections On The National History StandardsWALACANo ratings yet

- Unit 1: The Elementary Social Studies Curriculum Lesson 1: What Is Social Studies?Document13 pagesUnit 1: The Elementary Social Studies Curriculum Lesson 1: What Is Social Studies?Giselle CabangonNo ratings yet

- Toward A Playful Pedagogy Popular Culture and TheDocument14 pagesToward A Playful Pedagogy Popular Culture and TheMiruna MateiNo ratings yet

- Civil Rights and Social Movements SyllabusDocument9 pagesCivil Rights and Social Movements Syllabuspattychen19No ratings yet

- 614 - Race, Ethnicity, Inequality PDFDocument9 pages614 - Race, Ethnicity, Inequality PDFPaul g. AdogamheNo ratings yet

- MUSIC 208R - 2017 Spring (24088)Document6 pagesMUSIC 208R - 2017 Spring (24088)mingeunuchbureaucratgmail.comNo ratings yet

- AltheideTrackingDiscourse1 s2.0 S0304422X0000005X MainDocument14 pagesAltheideTrackingDiscourse1 s2.0 S0304422X0000005X MainDarinaa ElsteitsagNo ratings yet

- Coming To AmericaDocument9 pagesComing To AmericaGeLo L. OgadNo ratings yet

- Historyandsocialstudiescurriculum ORE Ross2020Document36 pagesHistoryandsocialstudiescurriculum ORE Ross2020Takudzwa GomeraNo ratings yet

- IAAAS Social Science Grade8 Q4UnitDocument15 pagesIAAAS Social Science Grade8 Q4UnitChuckGLPNo ratings yet

- Syllabusdoc3 Gagnonsp16Document5 pagesSyllabusdoc3 Gagnonsp16api-317922107No ratings yet

- Debating The Meaning of "Social Studies"Document15 pagesDebating The Meaning of "Social Studies"Dicky WahyudiNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan 5Document12 pagesLesson Plan 5api-510714748No ratings yet

- Resource CollectionDocument9 pagesResource Collectionapi-702310108No ratings yet

- Greenwalt and Holohan, Performing The NationDocument25 pagesGreenwalt and Holohan, Performing The NationKyle GreenwaltNo ratings yet

- Higher Education Music Students' Perceptions of The Benefits of Participative Music MakingDocument18 pagesHigher Education Music Students' Perceptions of The Benefits of Participative Music MakingMaria DiazNo ratings yet

- Two-Column Notes: Standards For Social Studies. Washington, DC: NCSS, 1-3Document4 pagesTwo-Column Notes: Standards For Social Studies. Washington, DC: NCSS, 1-3api-328484850No ratings yet

- Abrahams The Application of Critical TheoryDocument16 pagesAbrahams The Application of Critical TheorySimon FillemonNo ratings yet

- Critical Discourse Analysis in Education ... Rogers (2005)Document53 pagesCritical Discourse Analysis in Education ... Rogers (2005)debiga fikky100% (1)

- Thinking Critically About Society An Introduction To Sociology 1st Edition Russell Westhaver Solutions Manual DownloadDocument5 pagesThinking Critically About Society An Introduction To Sociology 1st Edition Russell Westhaver Solutions Manual DownloadMarshall Brammell100% (23)

- Critical Studies TheoryDocument20 pagesCritical Studies TheoryTiaraNo ratings yet

- Part Front Matter For Part II TransformationsDocument2 pagesPart Front Matter For Part II Transformations吴善统No ratings yet

- Meaning Over Memory: Recasting the Teaching of Culture and HistoryFrom EverandMeaning Over Memory: Recasting the Teaching of Culture and HistoryNo ratings yet

- Freedom Schooling - Stokely Carmichael and Rhetorical EducationDocument25 pagesFreedom Schooling - Stokely Carmichael and Rhetorical EducationHenriqueNo ratings yet

- JMHP Teaching Global Music HistoryDocument55 pagesJMHP Teaching Global Music Historyokorochinenyemodesta2No ratings yet

- 0D92Ed01 - Reconfiguring The Public Sphere Implications For Analyses of Educational PolicyDocument22 pages0D92Ed01 - Reconfiguring The Public Sphere Implications For Analyses of Educational PolicyskripsitesismuNo ratings yet

- Jessarie CaragDocument8 pagesJessarie Caragjessariecarag69No ratings yet

- GreenbloomeethnogDocument42 pagesGreenbloomeethnogLuisaNo ratings yet

- Listening Beyond The Echoes MediaDocument207 pagesListening Beyond The Echoes Mediab-b-b1230% (1)

- Class Politics: The Movement for the Students’ Right to Their Own LanguageFrom EverandClass Politics: The Movement for the Students’ Right to Their Own LanguageNo ratings yet

- Journal of Art For LifeDocument18 pagesJournal of Art For LifeSopyan AhmadNo ratings yet

- Ackerman & Fishkin - Deliberation DayDocument289 pagesAckerman & Fishkin - Deliberation DayJulián González100% (1)

- Teaching The 1960s With Primary SourcesDocument13 pagesTeaching The 1960s With Primary SourcesMohammad Amri MustafaNo ratings yet

- Unesco - Eolss Sample Chapters: Tropical Rain ForestsDocument9 pagesUnesco - Eolss Sample Chapters: Tropical Rain ForestsarreeNo ratings yet

- Gallery Springer 2014 PDFDocument23 pagesGallery Springer 2014 PDFarreeNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4: Subtropical Forests Richard T Corlett and Alice C. HughesDocument11 pagesChapter 4: Subtropical Forests Richard T Corlett and Alice C. HughesarreeNo ratings yet

- Nava Graha Stotram - English Lyrics (Text)Document2 pagesNava Graha Stotram - English Lyrics (Text)arreeNo ratings yet

- 235 Bars of Blues Guitar Licks: Standard TuningDocument8 pages235 Bars of Blues Guitar Licks: Standard TuningarreeNo ratings yet

- Prog 1Document1 pageProg 1arreeNo ratings yet

- Prog 1Document1 pageProg 1arreeNo ratings yet

- Hello WorldDocument1 pageHello WorldarreeNo ratings yet

- Return IDocument1 pageReturn IarreeNo ratings yet

- Michael Ramirez: For Trumpet and Live ElectronicsDocument4 pagesMichael Ramirez: For Trumpet and Live ElectronicsMichael RamirezNo ratings yet

- Multiple Intelligences TestDocument14 pagesMultiple Intelligences TestElena BeleskaNo ratings yet

- 33 Songwriting Prompts - Assignments by Tony ConniffDocument14 pages33 Songwriting Prompts - Assignments by Tony Conniffzameer1506No ratings yet

- Arpeggio Connection Exercises Major PDFDocument4 pagesArpeggio Connection Exercises Major PDFManuel Alejandro Rodriguez Madrigal100% (1)

- Emotions Evoked by The Sound of MusicDocument29 pagesEmotions Evoked by The Sound of MusicΕιρηνη ΚαλογερακηNo ratings yet

- Development of The SonataDocument9 pagesDevelopment of The SonataKatNo ratings yet

- Diary of A Madman TabDocument7 pagesDiary of A Madman TabjjwfishNo ratings yet

- UNCHAINDocument26 pagesUNCHAINEfe SezerNo ratings yet

- William Hettrick CVDocument9 pagesWilliam Hettrick CVHofstraUniversityNo ratings yet

- The Offspring - Greatest Hits - Full Album - YouTubeDocument2 pagesThe Offspring - Greatest Hits - Full Album - YouTubeEsteban PerezNo ratings yet

- Edwin Gordon - All About Audiation and Music AptitudesDocument4 pagesEdwin Gordon - All About Audiation and Music Aptitudeselinlau0No ratings yet

- HMG - in MemoriamDocument7 pagesHMG - in MemoriamSzkola SzkolaNo ratings yet

- MGM's Film of Cole Porter's DUBARRY WAS A LADY (1943)Document2 pagesMGM's Film of Cole Porter's DUBARRY WAS A LADY (1943)Ross CareNo ratings yet

- 2019 EUYWO Registration Form enDocument2 pages2019 EUYWO Registration Form enjoaquim97No ratings yet

- David Binney Press Kit PDFDocument26 pagesDavid Binney Press Kit PDFseagle5No ratings yet

- Sound-Generated SpaceDocument7 pagesSound-Generated SpaceJesper BondeNo ratings yet

- Explaning Meyer 1983Document13 pagesExplaning Meyer 1983Carlos Henrique Guadalupe SilveiraNo ratings yet

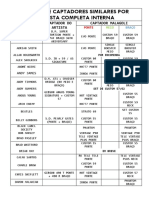

- Indicação de CaptadorDocument5 pagesIndicação de CaptadorenioNo ratings yet

- Drone Lab: PacksDocument43 pagesDrone Lab: PacksscribidisshitNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Philippine MusicDocument2 pagesContemporary Philippine MusicCHAPEL JUN PACIENTE100% (1)

- La Vida Es Un Carnaval-Partitura y PartesDocument22 pagesLa Vida Es Un Carnaval-Partitura y PartesBeaBeteta78No ratings yet

- Traditional ComposersDocument23 pagesTraditional ComposersAngelyn Co-SicatNo ratings yet

- The 'Grosse Fuge' An AnalysisDocument10 pagesThe 'Grosse Fuge' An AnalysisJoão Corrêa100% (1)

- Moonlight Densetsu From Sailor Moon Harp SoloDocument2 pagesMoonlight Densetsu From Sailor Moon Harp SoloAnnaNo ratings yet

- Enhancement As Q1 G11 RAWSDocument12 pagesEnhancement As Q1 G11 RAWSKazandra Cassidy GarciaNo ratings yet