Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Correcting Working Postures in Industry: A Practical Method For Analysis

Correcting Working Postures in Industry: A Practical Method For Analysis

Uploaded by

GOBCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Correcting Working Postures in Industry: A Practical Method For AnalysisDocument3 pagesCorrecting Working Postures in Industry: A Practical Method For AnalysissubirNo ratings yet

- Mork 2015Document10 pagesMork 2015andresNo ratings yet

- Applied Ergonomics: Miranda Cornelissen, Roderick Mcclure, Paul M. Salmon, Neville A. StantonDocument11 pagesApplied Ergonomics: Miranda Cornelissen, Roderick Mcclure, Paul M. Salmon, Neville A. StantonMas SahidNo ratings yet

- 2014 - Battini - Innovative Real Time System To Integrate Ergonomic Evaluations Into Warehouse DesignDocument10 pages2014 - Battini - Innovative Real Time System To Integrate Ergonomic Evaluations Into Warehouse DesignJohannes SchützNo ratings yet

- Salmon Et Al. - 2009Document11 pagesSalmon Et Al. - 2009Mehdi PoornikooNo ratings yet

- Aplicacion de BiomecanicaDocument25 pagesAplicacion de BiomecanicaJOSE JAVIER BARZALLO GALVEZNo ratings yet

- Grier 2013Document5 pagesGrier 2013nandaas887No ratings yet

- Introducing Quantitative Analysis Methods Into Virtual Environments For Real-Time and Continuous Ergonomic EvaluationsDocument14 pagesIntroducing Quantitative Analysis Methods Into Virtual Environments For Real-Time and Continuous Ergonomic EvaluationsJorge Luis Raygada AzpilcuetaNo ratings yet

- Ergonomics Study For Injection Moulding Section Using RULA and REBA TechniquesDocument9 pagesErgonomics Study For Injection Moulding Section Using RULA and REBA TechniquesJorge Luis Raygada AzpilcuetaNo ratings yet

- Lins Et Al 2021Document9 pagesLins Et Al 2021ElAhijadoNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics: D. Battini, M. Faccio, A. Persona, F. SgarbossaDocument13 pagesInternational Journal of Industrial Ergonomics: D. Battini, M. Faccio, A. Persona, F. SgarbossaVipin KumarNo ratings yet

- Postural Analysis of Building Construction Workers Using ErgonomicsDocument9 pagesPostural Analysis of Building Construction Workers Using Ergonomicsgowri ajithNo ratings yet

- Todos Los MetodosDocument22 pagesTodos Los MetodosvictorNo ratings yet

- Biomechanical Assessments of TDocument36 pagesBiomechanical Assessments of TyorddiccNo ratings yet

- Wor 2012 41-S1 WOR0699Document7 pagesWor 2012 41-S1 WOR0699Mário Sobral JúniorNo ratings yet

- Gangopadhyay-Dev2014 Article DesignAndEvaluationOfErgonomyDocument6 pagesGangopadhyay-Dev2014 Article DesignAndEvaluationOfErgonomyabhimanyu adhikaryNo ratings yet

- Cevikcan Kilic2016Document20 pagesCevikcan Kilic2016QMS WIDCCNo ratings yet

- Field Study, Field Experiment, and Macroergonomic Analysis of Structure (MAS) MethodsDocument5 pagesField Study, Field Experiment, and Macroergonomic Analysis of Structure (MAS) MethodsZahra WiniadestaNo ratings yet

- An Ergonomic Evaluation of Preoperative and Postoperative Workspaces in Ambulatory Surgery CentersDocument12 pagesAn Ergonomic Evaluation of Preoperative and Postoperative Workspaces in Ambulatory Surgery CentersebrahimpanNo ratings yet

- Qec Reference GuideDocument22 pagesQec Reference GuideVitaPangestikaNo ratings yet

- An Integrative Approach For Evaluating Work Related Musculoskeletal DisordersDocument10 pagesAn Integrative Approach For Evaluating Work Related Musculoskeletal DisordersmariaNo ratings yet

- Proposal of Parameters To Implement A Workstation Rotation System To Protect Against MsdsDocument10 pagesProposal of Parameters To Implement A Workstation Rotation System To Protect Against MsdsEnriqueNo ratings yet

- 2017 - Manghisi - Real Time RULA Assessment Using Kinect v2 SensorDocument11 pages2017 - Manghisi - Real Time RULA Assessment Using Kinect v2 SensorJohannes SchützNo ratings yet

- Anumba 2001Document11 pagesAnumba 2001wachid yahyaNo ratings yet

- Ergonomics Study of Automobile-Assembly-LineDocument5 pagesErgonomics Study of Automobile-Assembly-Linekalite gurusuNo ratings yet

- Jurnal ErgonomicDocument6 pagesJurnal ErgonomicDallan AizenNo ratings yet

- Materials Today: Proceedings: Harold Villacís Jara, Iván Zambrano Orejuela, J.M. Baydal-BertomeuDocument7 pagesMaterials Today: Proceedings: Harold Villacís Jara, Iván Zambrano Orejuela, J.M. Baydal-Bertomeumari ccallo noaNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument15 pagesPDFreza30 dilagaNo ratings yet

- A Neurophysiological Approach To Assess Training Outcome Under StressDocument16 pagesA Neurophysiological Approach To Assess Training Outcome Under StressdianagueNo ratings yet

- A Practical Method For The Assessment of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Risks - Quick Exposure Check (QEC)Document6 pagesA Practical Method For The Assessment of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Risks - Quick Exposure Check (QEC)hildaNo ratings yet

- DIAGNOSTIC - DES - SYSTEMES - INDUSTRIELS (1) KCCDocument30 pagesDIAGNOSTIC - DES - SYSTEMES - INDUSTRIELS (1) KCCjacqueminattouekouassiNo ratings yet

- Nihms 1903570Document20 pagesNihms 1903570sam mehraNo ratings yet

- Redes Neuronales - Aplicación y Oportunidades en AeronáuticaDocument6 pagesRedes Neuronales - Aplicación y Oportunidades en AeronáuticaVany BraunNo ratings yet

- Ergonomics at Work PlaceDocument16 pagesErgonomics at Work PlaceKoutuk MogerNo ratings yet

- Ergonomics: Body Posture: Summary On Research PapersDocument11 pagesErgonomics: Body Posture: Summary On Research PapersPreksha PandeyNo ratings yet

- OSHA Module 2Document16 pagesOSHA Module 2Varsha G100% (1)

- A Field Methodology For The Control of Musculoskeletal InjuriesDocument14 pagesA Field Methodology For The Control of Musculoskeletal InjuriesIbañez AlejandroNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Reliability Allocation Methods: Luca Silvestri, Domenico Falcone, Giuseppina BelfioreDocument8 pagesGuidelines For Reliability Allocation Methods: Luca Silvestri, Domenico Falcone, Giuseppina Belfioreali alvandi100% (1)

- BUKU QEC A Practical Method For The Assessment of Work-RelaDocument6 pagesBUKU QEC A Practical Method For The Assessment of Work-Reladery2000019094No ratings yet

- Research Regarding Works Ergonomics in Automotive Repair ShopDocument7 pagesResearch Regarding Works Ergonomics in Automotive Repair ShopEPNo ratings yet

- Reliability and Concurrent Validity of The Computer Workstation ChecklistDocument9 pagesReliability and Concurrent Validity of The Computer Workstation ChecklistDavid DizonNo ratings yet

- 50-Article Text-145-107-10-20210622Document30 pages50-Article Text-145-107-10-20210622Hazeq ZNo ratings yet

- Coleman 1995Document9 pagesColeman 1995بلال بن عميرهNo ratings yet

- Articulo Cientifico 1Document9 pagesArticulo Cientifico 1Danna JimenezNo ratings yet

- Background: C4711 - C01.fm Page 1 Saturday, February 28, 2004 10:30 AMDocument23 pagesBackground: C4711 - C01.fm Page 1 Saturday, February 28, 2004 10:30 AMamir amirNo ratings yet

- Review Article Methodological Approaches To Anaesthetists' Workload in The Operating TheatreDocument8 pagesReview Article Methodological Approaches To Anaesthetists' Workload in The Operating TheatreRafael BagusNo ratings yet

- A Method Assigned For The Identification of A Ergonomic Hazards - Plibel - KemmlertDocument13 pagesA Method Assigned For The Identification of A Ergonomic Hazards - Plibel - KemmlertIbañez AlejandroNo ratings yet

- Critical ReviewDocument10 pagesCritical ReviewBrenda Venitta LantuNo ratings yet

- 1 SMDocument11 pages1 SMfarahzibaNo ratings yet

- Observation Procedures Characterizing Occupational Physical Activities: Critical ReviewDocument28 pagesObservation Procedures Characterizing Occupational Physical Activities: Critical ReviewtheleoneNo ratings yet

- Utilization of Participatory Ergonomics For Workstation Evaluation Towards Productive ManufacturingDocument6 pagesUtilization of Participatory Ergonomics For Workstation Evaluation Towards Productive ManufacturingJorge Alejandro Patron ChicanaNo ratings yet

- Ergonomics at Work PlaceDocument10 pagesErgonomics at Work PlacevishwaNo ratings yet

- Quick Exposure Check (QEC) Reference: GuideDocument24 pagesQuick Exposure Check (QEC) Reference: GuidePaula AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- Analiza Publicaiilor Privind ProteciaDocument10 pagesAnaliza Publicaiilor Privind ProteciaMihai RusuNo ratings yet

- Applications of Ergonomics and Work Study in An Organization (A Case Study)Document9 pagesApplications of Ergonomics and Work Study in An Organization (A Case Study)International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology100% (3)

- IJBAMR Content ValidityDocument7 pagesIJBAMR Content ValidityRohin GargNo ratings yet

- Pt4822-Ergonomics BookDocument104 pagesPt4822-Ergonomics BookMr.Nasser HassanNo ratings yet

- MHAC-An Assessment Tool For Analysing Manual Material Handling TasksDocument14 pagesMHAC-An Assessment Tool For Analysing Manual Material Handling TasksDiego A Echavarría ANo ratings yet

- Reliability and Usability of The Ergonomic Workplace MethodDocument14 pagesReliability and Usability of The Ergonomic Workplace MethodEPNo ratings yet

- Project Execution Plan TemplateDocument5 pagesProject Execution Plan TemplateJRE LettingsNo ratings yet

- Impact of Railways On Employment GenerationDocument9 pagesImpact of Railways On Employment Generationasmi94No ratings yet

- Sallivahan Class NotesDocument3 pagesSallivahan Class NotesHimanshu DidwaniyaNo ratings yet

- Business Transactions Their AnalysisDocument5 pagesBusiness Transactions Their AnalysisJeah PanganibanNo ratings yet

- Cup 3 AFAR 1Document9 pagesCup 3 AFAR 1Elaine Joyce GarciaNo ratings yet

- MS-CIT Question Bank 1: Answer Start ButtonDocument29 pagesMS-CIT Question Bank 1: Answer Start ButtonChamika Madushan ManawaduNo ratings yet

- Ananta Tsabita Agustina (06) Second PortofolioDocument8 pagesAnanta Tsabita Agustina (06) Second PortofolioAnanta TsabitaNo ratings yet

- Guia Entrenamiento en Habilidades de Cuiado en Familiares de Niñs Con DiscapacidadDocument20 pagesGuia Entrenamiento en Habilidades de Cuiado en Familiares de Niñs Con DiscapacidadAbigail MJNo ratings yet

- System Analysis and Design - Quick Guide - TutorialspointDocument70 pagesSystem Analysis and Design - Quick Guide - TutorialspointKayeh VarxNo ratings yet

- PHD Thesis in Education in PakistanDocument7 pagesPHD Thesis in Education in Pakistanbk156rhq100% (2)

- One Pager v2Document2 pagesOne Pager v2JuanCarlosMarrufoNo ratings yet

- Acctstmt DDocument3 pagesAcctstmt Dmaakabhawan26No ratings yet

- PHY 107 Experiment 1Document6 pagesPHY 107 Experiment 1Aisha AwaisuNo ratings yet

- Week 12 WOWS Penyelesaian Dan Kerja Ulan PDFDocument41 pagesWeek 12 WOWS Penyelesaian Dan Kerja Ulan PDFmndNo ratings yet

- City Limits Magazine, November 2000 IssueDocument52 pagesCity Limits Magazine, November 2000 IssueCity Limits (New York)No ratings yet

- IR7243 en ModuloDocument2 pagesIR7243 en ModuloAitor Tapia SaavedraNo ratings yet

- Borchert Epochs SummaryDocument5 pagesBorchert Epochs SummaryDafri EsfandiariNo ratings yet

- Math SBA 1Document18 pagesMath SBA 1The First Song Was Titled MemoriesNo ratings yet

- Construction Safety - Part 2 (Site Premises)Document20 pagesConstruction Safety - Part 2 (Site Premises)Henry Turalde0% (1)

- July 2006Document24 pagesJuly 2006Judicial Watch, Inc.No ratings yet

- Relevance of Forensic Accounting in The PDFDocument10 pagesRelevance of Forensic Accounting in The PDFPrateik RyukiNo ratings yet

- Micro MachiningDocument302 pagesMicro Machiningapulavarty100% (2)

- Submittal Chiler 205 TRDocument5 pagesSubmittal Chiler 205 TRcarmen hernandezNo ratings yet

- HA16129FPJ: Single Watchdog TimerDocument24 pagesHA16129FPJ: Single Watchdog TimerMichael PorterNo ratings yet

- Deep WorkDocument2 pagesDeep Workbama33% (6)

- 3 Boiler PAF and System Commissioning Procedure-TöàtéëS+Ç íTúÄ Såèsà T +T+ƑF Âf Ò Ä Û+Document34 pages3 Boiler PAF and System Commissioning Procedure-TöàtéëS+Ç íTúÄ Såèsà T +T+ƑF Âf Ò Ä Û+kvsagarNo ratings yet

- Business Bay MSDocument14 pagesBusiness Bay MSM UMER KHAN YOUSAFZAINo ratings yet

- PERSONAL FINANCE Multiple Choice QuestionsDocument3 pagesPERSONAL FINANCE Multiple Choice QuestionsLinh KhánhNo ratings yet

- Purchase Order 2023Document12 pagesPurchase Order 2023zelleL21No ratings yet

- Tesco CaseDocument17 pagesTesco CaseManish ThakurNo ratings yet

Correcting Working Postures in Industry: A Practical Method For Analysis

Correcting Working Postures in Industry: A Practical Method For Analysis

Uploaded by

GOBOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Correcting Working Postures in Industry: A Practical Method For Analysis

Correcting Working Postures in Industry: A Practical Method For Analysis

Uploaded by

GOBCopyright:

Available Formats

ApplledErgonomtcs 1977, 8.

4, 199-201

Correcting working postures in

industry: A practical method

for analysis

Osmo Karhu*, Pekka Kansi** and Ilkka Kuorinka***

* Department manager,OVAKO Oy, Helsinki, Finland

** MSc, Finnish Institute for Leadership,Helsinki, Finland

*** Assistant Director, Institute of Occupational Health, Departmentof Physiology, Helsinki, Finland

A practical method for identifying and evaluating poor working postures, ie, the Ovako

Working Posture Analysing System (OWAS), is presented. The method consists of two

parts. The first is an observational technique for evaluating working postures. It can be

used by work-study engineers in their daily routine and it gives reliable results after a

short training period. The second part of the method is a set of criteria for the redesign

of working methods and places. The criteria are based on evaluations made by

experienced workers and ergonomics experts. They take into consideration factors such

as health and safety, but the main emphasis is placed on the discomfort caused by the

working postures. The method has been extensively used in the steel company which

participated in its development. Complete production lines have already been redesigned

on the basis of information gathered from OWAS, the result being more comfortable

workplaces as well as a positive effect on production quality.

Introduction by ergonomically untrained personnel, (b) it must provide

unambiguous answers even if it results in over-simplification,

When the problems of working postures in industry are (c) it must also offer possibilities for correcting the over-

considered, the following two questions are important. What

simplified ergonomic approach. Continuity is gained if the

is the most feasible way of analysing postures? How does

method can be incorporated into existing routine tasks.

one know which postures are the poor ones, ie, how can

the postures be evaluated according to a chosen criterion? The Ovako Working Posture Analysing System (OWAS)

has been planned to meet the preceding criteria for use by

The first question seems fairly easy to answer. The

work-study engineers. The engineers may use it as part of

features of a working situation can be observed (eg, Tippet,

their daily routine or as a separate analytical tool. The

1967) or photographed (Muybridge, 1887), or

method is based on work sampling (variable or constant

chronocyclography, etc, can be used. The newest methods

interval sampling), which provides the frequency of, and

available are automated, computer-based posture and

time spent in, each posture. The postures are classified and

movement analysing systems. The posture analyser can

their discomfort assessed so that a systematic guide to

choose the method to be used according to his needs and

corrective action can be constructed. Occupational health

economical resources.

personnel participate in the use of OWAS and this procedure

The problem of identifying and classifying poor working helps to solve problems arising from a too rigid application

postures seems more complicated. Scientific literature on of the system.

the ill effects of working postures is scant; well-controlled

epidemiological studies are few; and present knowledge is

mainly based on case reports and common sense. In the

Table 1: Schemeof the reliability evaluationof posturex

earlier literature poor postures were connected with

physically heavy jobs, in which diseases of the musculo-

rs Morning observation Afternoon observation

skeletal system were over-represented (Schr6ter, 1961).

Poor postures and the physical demands of the job were

regarded as the causes of the injuries. The relation between

ergonomic deficiencies in the workplace and diseases of Worker A Worker B Worker A Worker B

engineers "~

the musculoskeletal system has been demonstrated by

van Wely (1970), and illustrative case reports have been No 1 hI h2 h3 h4

published by Perrot (1961).

An analytical method for industry must meet the No 2 hs h6 h7 hs

following criteria: (a) it must be simple enough to be used t

Applied Ergonomics December 1977 199

Classification of postures statistical method used, see Ferguson, 1959). The scheme

and results of the reliability check are presented in Tables 1

The working postures were collected from photographic

material taken in several divisions of one steel factory. The

and 2 respectively. The percentages in Table 2 describe

the inter-worker and inter-observer agreement as well as the

material covered most of the working postures typical for

agreement between the morning and afternoon observations.

a branch of heavy industry. The material was sorted to

In general the reliability of the observations was fairly good

form a classified system. The classification was based on

the subjective evaluation of discomfort and the health between the two work-study engineers. The figures indicate,

effect of each posture, as well as the practicability of however, that the two workers who were observed doing

observational analysis. The classification yielded 72 postures the same job used different postures on a large percentage

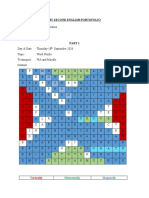

(for some examples, see Fig. 1), the main grouping being of occasions. From a theoretical point of view the concept

based on the general features (sitting, standing, etc.) and of reliability may need more clarification, but for practical

the position of the back and arms. The classification purposes the information presented here seems sufficient

itself implied the existence of some postures which did to justify OWAS. The reliability of the work sampling

not appear in the original photographic material. method has been discussed in other literature (eg, Ferguson,

1959).

During a pilot study the practicability of the method was

tested. Twelve work-study engineers spent one week learning

the system. After this training they analysed 28 tasks in the Evaluation of the classified postures

steel plant. The results were encouraging, and we proceeded In order to evaluate each posture from the point of view

to the next phase of evaluating the reliability of the method. of the discomfort caused and the effect on health, we

During the pilot phase training material was also developed established a rating system with which 32 experienced steel

for later teaching programmes. workers evaluated each position twice during the same

During the reliability evaluation, 52 tasks were analysed session. For each posture the workers were shown a male

and a total of 36 240 observations were made (for the manikin properly positioned as well as a schematic drawing.

The four-point rating scale which was employed had the

following extremes: "normal posture with no discomfort

and no effect on health" and "extremely bad posture,

(41 short exposure leads to discomfort, ill effect on health

possible". From the workers' ratings a mean rating was

calculated for each posture and a rank order was established.

In general the distributions of the workers' ratings were

coherent. In some cases, however, a scattering of ratings

occurred. In order to provide these postures with a firm

rating, a small group of international ergonomists also rated

straight bent twisted twisted them. The final rating of each posture was formed from

the workers' ratings weighted by the evaluation of the

/1 ~(1) ~==1, (2] ~==(~=~AN,~X-A.MPLE specialists.

O W A S as a tool for work-study engineers

both one

After each of the postures had been rated, they were

limbs ~ limb ~

claor re-classified into four categories according to the results.

s h o u l d e r level e h m t l d ~ level The first category contained the normal postures, the fourth

q) (1] ~) (~ q) (3) included those which were rated as the most uncomfortable,

and the other two were made up of the postures with

/ / / RACK:bent (2) intermediate ratings. These categories, which have an

LIMBS: operative character, were named operative classes. Each

! both bek~

~ ~ slmtflderlevel(I] class has an implication for the work-study engineer, ie:

' LOWERLIMBS:

loadingon mxe Class 1 = normal postures which do not need any special

load~zgonboth Ioadfng o n both llmb, ]~neeli attention, except in some special cases

(} (41 (} (5] (l i 16)! (} (7)

/, \ ,! \ Table 2: The medians and ranges of the percentage

agreement between the two workers, the two

work-study engineers, and the morning/afternoon

observations

loadingon one loading~ one both limbs

tree Item Median Range

% %

Fig. 1 List of items classified by OWAS (the Ovako Workers A and B 69 23-88

Working Posture Analysing System). A code number

Work-study

is given for each item. Each posture can be described 93 74-99

engineers 1 and 2

with a three-digit code. The example in the right

side of the figure, thus, can be represented by the Morning/afternoon 86 70-100

code 215.

200 Applied Ergonomics December 1977

Class 2 = postures must be considered during the next decoding transparency. OWAS has proved to be handy and

regular check of working methods easy to use. Observations can be made rapidly on postures

Class 3 = postures need consideration in the near future so that they can be classified into various groups and then

evaluated in terms of their desirability and need of attention,

Class 4 = postures need immediate consideration by reference to the special formula and decoding

In practice the work-study engineer uses OWAS during transparency. One by-product of OWAS has been a growing

his daily routine. If postures are regarded as a special interest in working conditions in the firm in which it has

problem, the method can of course be used separately. It been applied. The training material developed at the

can also be applied by other personnel such as safety beginning of the project has not only greatly added to-the

engineers, health officers, etc, after they have been work-study personnel's knowledge of working postures but

appropriately trained. also to that of production engineers.

Before OWAS can be useful as a tool for improving

working conditions, company policy towards working

conditions must be decided, Otherwise the work-study

References

engineer's use of OWAS has no meaning.

Ferguson, G.A.

Experience w i t h O W A S 1959 'Statistical analysis in psychology and education'

McGraw-Hill Book Co, 264-275.

OWAS has been used for two years in the steel

company which developed it. The work-study engineers Muybridge, E.

make their analyses either during their daily routine or at 1887 'The human figure in motion' (new edition 1955).

the request of production departments, health personnel or Dover Publications, New York.

workers. The results have led to improvements in comfort Perrot, J.W.

in individual jobs and have greatly contributed to the 1961 MedicalJournal of Australia 3, 73-82. Anatomical

reconstruction of some production lines. For one difficult factors in occupational trauma.

task, bricklaying the deck of an electric arc oven, a

SchrSter, G.

satisfactory solution was found with OWAS*. Trials to

1961 Aufbraucht und Abnutzungskrankheiten in 'Handbuch

solve the problem had earlier been made for many years

der gesamten Arbeitsmedizin', ed E.W. Baader, Bd II,

in vain. The effects of OWAS in improving health and safety

2. Teilband, 448-472. Urban und Schwarzberg,

are currently being evaluated.

Berlin.

With OWAS a rapid registration and check of working

Tippet, L.M.C.

postures can be made with the use of a special formula and

1967 In Hovi, Lehmuskoski, Ojanen.'Havainnointimenetelm/i

tytJntutkimuksessa'. Tietomies, Helsinki.

* Case-study material on this exercise, illustrating the use van Wely, P.

of OWAS. will be published in a future issue of Applied 1970 Applied Ergonomics 1.5,262-269. Design and

Ergonomics. disease.

Applied Ergonomics December 1977 201

You might also like

- Correcting Working Postures in Industry: A Practical Method For AnalysisDocument3 pagesCorrecting Working Postures in Industry: A Practical Method For AnalysissubirNo ratings yet

- Mork 2015Document10 pagesMork 2015andresNo ratings yet

- Applied Ergonomics: Miranda Cornelissen, Roderick Mcclure, Paul M. Salmon, Neville A. StantonDocument11 pagesApplied Ergonomics: Miranda Cornelissen, Roderick Mcclure, Paul M. Salmon, Neville A. StantonMas SahidNo ratings yet

- 2014 - Battini - Innovative Real Time System To Integrate Ergonomic Evaluations Into Warehouse DesignDocument10 pages2014 - Battini - Innovative Real Time System To Integrate Ergonomic Evaluations Into Warehouse DesignJohannes SchützNo ratings yet

- Salmon Et Al. - 2009Document11 pagesSalmon Et Al. - 2009Mehdi PoornikooNo ratings yet

- Aplicacion de BiomecanicaDocument25 pagesAplicacion de BiomecanicaJOSE JAVIER BARZALLO GALVEZNo ratings yet

- Grier 2013Document5 pagesGrier 2013nandaas887No ratings yet

- Introducing Quantitative Analysis Methods Into Virtual Environments For Real-Time and Continuous Ergonomic EvaluationsDocument14 pagesIntroducing Quantitative Analysis Methods Into Virtual Environments For Real-Time and Continuous Ergonomic EvaluationsJorge Luis Raygada AzpilcuetaNo ratings yet

- Ergonomics Study For Injection Moulding Section Using RULA and REBA TechniquesDocument9 pagesErgonomics Study For Injection Moulding Section Using RULA and REBA TechniquesJorge Luis Raygada AzpilcuetaNo ratings yet

- Lins Et Al 2021Document9 pagesLins Et Al 2021ElAhijadoNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics: D. Battini, M. Faccio, A. Persona, F. SgarbossaDocument13 pagesInternational Journal of Industrial Ergonomics: D. Battini, M. Faccio, A. Persona, F. SgarbossaVipin KumarNo ratings yet

- Postural Analysis of Building Construction Workers Using ErgonomicsDocument9 pagesPostural Analysis of Building Construction Workers Using Ergonomicsgowri ajithNo ratings yet

- Todos Los MetodosDocument22 pagesTodos Los MetodosvictorNo ratings yet

- Biomechanical Assessments of TDocument36 pagesBiomechanical Assessments of TyorddiccNo ratings yet

- Wor 2012 41-S1 WOR0699Document7 pagesWor 2012 41-S1 WOR0699Mário Sobral JúniorNo ratings yet

- Gangopadhyay-Dev2014 Article DesignAndEvaluationOfErgonomyDocument6 pagesGangopadhyay-Dev2014 Article DesignAndEvaluationOfErgonomyabhimanyu adhikaryNo ratings yet

- Cevikcan Kilic2016Document20 pagesCevikcan Kilic2016QMS WIDCCNo ratings yet

- Field Study, Field Experiment, and Macroergonomic Analysis of Structure (MAS) MethodsDocument5 pagesField Study, Field Experiment, and Macroergonomic Analysis of Structure (MAS) MethodsZahra WiniadestaNo ratings yet

- An Ergonomic Evaluation of Preoperative and Postoperative Workspaces in Ambulatory Surgery CentersDocument12 pagesAn Ergonomic Evaluation of Preoperative and Postoperative Workspaces in Ambulatory Surgery CentersebrahimpanNo ratings yet

- Qec Reference GuideDocument22 pagesQec Reference GuideVitaPangestikaNo ratings yet

- An Integrative Approach For Evaluating Work Related Musculoskeletal DisordersDocument10 pagesAn Integrative Approach For Evaluating Work Related Musculoskeletal DisordersmariaNo ratings yet

- Proposal of Parameters To Implement A Workstation Rotation System To Protect Against MsdsDocument10 pagesProposal of Parameters To Implement A Workstation Rotation System To Protect Against MsdsEnriqueNo ratings yet

- 2017 - Manghisi - Real Time RULA Assessment Using Kinect v2 SensorDocument11 pages2017 - Manghisi - Real Time RULA Assessment Using Kinect v2 SensorJohannes SchützNo ratings yet

- Anumba 2001Document11 pagesAnumba 2001wachid yahyaNo ratings yet

- Ergonomics Study of Automobile-Assembly-LineDocument5 pagesErgonomics Study of Automobile-Assembly-Linekalite gurusuNo ratings yet

- Jurnal ErgonomicDocument6 pagesJurnal ErgonomicDallan AizenNo ratings yet

- Materials Today: Proceedings: Harold Villacís Jara, Iván Zambrano Orejuela, J.M. Baydal-BertomeuDocument7 pagesMaterials Today: Proceedings: Harold Villacís Jara, Iván Zambrano Orejuela, J.M. Baydal-Bertomeumari ccallo noaNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument15 pagesPDFreza30 dilagaNo ratings yet

- A Neurophysiological Approach To Assess Training Outcome Under StressDocument16 pagesA Neurophysiological Approach To Assess Training Outcome Under StressdianagueNo ratings yet

- A Practical Method For The Assessment of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Risks - Quick Exposure Check (QEC)Document6 pagesA Practical Method For The Assessment of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Risks - Quick Exposure Check (QEC)hildaNo ratings yet

- DIAGNOSTIC - DES - SYSTEMES - INDUSTRIELS (1) KCCDocument30 pagesDIAGNOSTIC - DES - SYSTEMES - INDUSTRIELS (1) KCCjacqueminattouekouassiNo ratings yet

- Nihms 1903570Document20 pagesNihms 1903570sam mehraNo ratings yet

- Redes Neuronales - Aplicación y Oportunidades en AeronáuticaDocument6 pagesRedes Neuronales - Aplicación y Oportunidades en AeronáuticaVany BraunNo ratings yet

- Ergonomics at Work PlaceDocument16 pagesErgonomics at Work PlaceKoutuk MogerNo ratings yet

- Ergonomics: Body Posture: Summary On Research PapersDocument11 pagesErgonomics: Body Posture: Summary On Research PapersPreksha PandeyNo ratings yet

- OSHA Module 2Document16 pagesOSHA Module 2Varsha G100% (1)

- A Field Methodology For The Control of Musculoskeletal InjuriesDocument14 pagesA Field Methodology For The Control of Musculoskeletal InjuriesIbañez AlejandroNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Reliability Allocation Methods: Luca Silvestri, Domenico Falcone, Giuseppina BelfioreDocument8 pagesGuidelines For Reliability Allocation Methods: Luca Silvestri, Domenico Falcone, Giuseppina Belfioreali alvandi100% (1)

- BUKU QEC A Practical Method For The Assessment of Work-RelaDocument6 pagesBUKU QEC A Practical Method For The Assessment of Work-Reladery2000019094No ratings yet

- Research Regarding Works Ergonomics in Automotive Repair ShopDocument7 pagesResearch Regarding Works Ergonomics in Automotive Repair ShopEPNo ratings yet

- Reliability and Concurrent Validity of The Computer Workstation ChecklistDocument9 pagesReliability and Concurrent Validity of The Computer Workstation ChecklistDavid DizonNo ratings yet

- 50-Article Text-145-107-10-20210622Document30 pages50-Article Text-145-107-10-20210622Hazeq ZNo ratings yet

- Coleman 1995Document9 pagesColeman 1995بلال بن عميرهNo ratings yet

- Articulo Cientifico 1Document9 pagesArticulo Cientifico 1Danna JimenezNo ratings yet

- Background: C4711 - C01.fm Page 1 Saturday, February 28, 2004 10:30 AMDocument23 pagesBackground: C4711 - C01.fm Page 1 Saturday, February 28, 2004 10:30 AMamir amirNo ratings yet

- Review Article Methodological Approaches To Anaesthetists' Workload in The Operating TheatreDocument8 pagesReview Article Methodological Approaches To Anaesthetists' Workload in The Operating TheatreRafael BagusNo ratings yet

- A Method Assigned For The Identification of A Ergonomic Hazards - Plibel - KemmlertDocument13 pagesA Method Assigned For The Identification of A Ergonomic Hazards - Plibel - KemmlertIbañez AlejandroNo ratings yet

- Critical ReviewDocument10 pagesCritical ReviewBrenda Venitta LantuNo ratings yet

- 1 SMDocument11 pages1 SMfarahzibaNo ratings yet

- Observation Procedures Characterizing Occupational Physical Activities: Critical ReviewDocument28 pagesObservation Procedures Characterizing Occupational Physical Activities: Critical ReviewtheleoneNo ratings yet

- Utilization of Participatory Ergonomics For Workstation Evaluation Towards Productive ManufacturingDocument6 pagesUtilization of Participatory Ergonomics For Workstation Evaluation Towards Productive ManufacturingJorge Alejandro Patron ChicanaNo ratings yet

- Ergonomics at Work PlaceDocument10 pagesErgonomics at Work PlacevishwaNo ratings yet

- Quick Exposure Check (QEC) Reference: GuideDocument24 pagesQuick Exposure Check (QEC) Reference: GuidePaula AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- Analiza Publicaiilor Privind ProteciaDocument10 pagesAnaliza Publicaiilor Privind ProteciaMihai RusuNo ratings yet

- Applications of Ergonomics and Work Study in An Organization (A Case Study)Document9 pagesApplications of Ergonomics and Work Study in An Organization (A Case Study)International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology100% (3)

- IJBAMR Content ValidityDocument7 pagesIJBAMR Content ValidityRohin GargNo ratings yet

- Pt4822-Ergonomics BookDocument104 pagesPt4822-Ergonomics BookMr.Nasser HassanNo ratings yet

- MHAC-An Assessment Tool For Analysing Manual Material Handling TasksDocument14 pagesMHAC-An Assessment Tool For Analysing Manual Material Handling TasksDiego A Echavarría ANo ratings yet

- Reliability and Usability of The Ergonomic Workplace MethodDocument14 pagesReliability and Usability of The Ergonomic Workplace MethodEPNo ratings yet

- Project Execution Plan TemplateDocument5 pagesProject Execution Plan TemplateJRE LettingsNo ratings yet

- Impact of Railways On Employment GenerationDocument9 pagesImpact of Railways On Employment Generationasmi94No ratings yet

- Sallivahan Class NotesDocument3 pagesSallivahan Class NotesHimanshu DidwaniyaNo ratings yet

- Business Transactions Their AnalysisDocument5 pagesBusiness Transactions Their AnalysisJeah PanganibanNo ratings yet

- Cup 3 AFAR 1Document9 pagesCup 3 AFAR 1Elaine Joyce GarciaNo ratings yet

- MS-CIT Question Bank 1: Answer Start ButtonDocument29 pagesMS-CIT Question Bank 1: Answer Start ButtonChamika Madushan ManawaduNo ratings yet

- Ananta Tsabita Agustina (06) Second PortofolioDocument8 pagesAnanta Tsabita Agustina (06) Second PortofolioAnanta TsabitaNo ratings yet

- Guia Entrenamiento en Habilidades de Cuiado en Familiares de Niñs Con DiscapacidadDocument20 pagesGuia Entrenamiento en Habilidades de Cuiado en Familiares de Niñs Con DiscapacidadAbigail MJNo ratings yet

- System Analysis and Design - Quick Guide - TutorialspointDocument70 pagesSystem Analysis and Design - Quick Guide - TutorialspointKayeh VarxNo ratings yet

- PHD Thesis in Education in PakistanDocument7 pagesPHD Thesis in Education in Pakistanbk156rhq100% (2)

- One Pager v2Document2 pagesOne Pager v2JuanCarlosMarrufoNo ratings yet

- Acctstmt DDocument3 pagesAcctstmt Dmaakabhawan26No ratings yet

- PHY 107 Experiment 1Document6 pagesPHY 107 Experiment 1Aisha AwaisuNo ratings yet

- Week 12 WOWS Penyelesaian Dan Kerja Ulan PDFDocument41 pagesWeek 12 WOWS Penyelesaian Dan Kerja Ulan PDFmndNo ratings yet

- City Limits Magazine, November 2000 IssueDocument52 pagesCity Limits Magazine, November 2000 IssueCity Limits (New York)No ratings yet

- IR7243 en ModuloDocument2 pagesIR7243 en ModuloAitor Tapia SaavedraNo ratings yet

- Borchert Epochs SummaryDocument5 pagesBorchert Epochs SummaryDafri EsfandiariNo ratings yet

- Math SBA 1Document18 pagesMath SBA 1The First Song Was Titled MemoriesNo ratings yet

- Construction Safety - Part 2 (Site Premises)Document20 pagesConstruction Safety - Part 2 (Site Premises)Henry Turalde0% (1)

- July 2006Document24 pagesJuly 2006Judicial Watch, Inc.No ratings yet

- Relevance of Forensic Accounting in The PDFDocument10 pagesRelevance of Forensic Accounting in The PDFPrateik RyukiNo ratings yet

- Micro MachiningDocument302 pagesMicro Machiningapulavarty100% (2)

- Submittal Chiler 205 TRDocument5 pagesSubmittal Chiler 205 TRcarmen hernandezNo ratings yet

- HA16129FPJ: Single Watchdog TimerDocument24 pagesHA16129FPJ: Single Watchdog TimerMichael PorterNo ratings yet

- Deep WorkDocument2 pagesDeep Workbama33% (6)

- 3 Boiler PAF and System Commissioning Procedure-TöàtéëS+Ç íTúÄ Såèsà T +T+ƑF Âf Ò Ä Û+Document34 pages3 Boiler PAF and System Commissioning Procedure-TöàtéëS+Ç íTúÄ Såèsà T +T+ƑF Âf Ò Ä Û+kvsagarNo ratings yet

- Business Bay MSDocument14 pagesBusiness Bay MSM UMER KHAN YOUSAFZAINo ratings yet

- PERSONAL FINANCE Multiple Choice QuestionsDocument3 pagesPERSONAL FINANCE Multiple Choice QuestionsLinh KhánhNo ratings yet

- Purchase Order 2023Document12 pagesPurchase Order 2023zelleL21No ratings yet

- Tesco CaseDocument17 pagesTesco CaseManish ThakurNo ratings yet