Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Non Communicable Disease in Childern and Adolescent

Non Communicable Disease in Childern and Adolescent

Uploaded by

Renov OmpusungguCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5822)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Academic Motivation Scale College VersionDocument4 pagesAcademic Motivation Scale College VersionJyothi MallyaNo ratings yet

- Roles of TeacherDocument5 pagesRoles of TeacherCharlynjoy Abañas67% (3)

- Analysis and Control of Underactuated Mechanical SystemsDocument148 pagesAnalysis and Control of Underactuated Mechanical SystemsDjelejnyNo ratings yet

- Explode The Code Book 1 Is The First Book in TheDocument10 pagesExplode The Code Book 1 Is The First Book in TheSurabhi Gupta ThakurNo ratings yet

- Frequencies: NotesDocument37 pagesFrequencies: NotesRenov OmpusungguNo ratings yet

- Standard Treatment Guidelines HaemodialysisDocument12 pagesStandard Treatment Guidelines HaemodialysisRenov OmpusungguNo ratings yet

- Flow Ands Cardiac ComplicationsDocument4 pagesFlow Ands Cardiac ComplicationsRenov OmpusungguNo ratings yet

- Takikardi RelatifDocument7 pagesTakikardi RelatifRenov OmpusungguNo ratings yet

- Group 1 Subjects Ca Inter - Google SearchDocument1 pageGroup 1 Subjects Ca Inter - Google Searchy7frhdvm5fNo ratings yet

- SDTS User Guide v2 0Document32 pagesSDTS User Guide v2 0jeffNo ratings yet

- S.K.S. Group of Institutions: (A) College FeeDocument1 pageS.K.S. Group of Institutions: (A) College FeeIsaac EdusahNo ratings yet

- Every Day Sometimes Always Often Usually Seldom Never First ... ThenDocument5 pagesEvery Day Sometimes Always Often Usually Seldom Never First ... ThenMuhammad PersadaNo ratings yet

- Board of Regents V RothDocument1 pageBoard of Regents V Rothapi-240190507No ratings yet

- Rubrics For Computer Integrated Manufacturing Lab Assessment: Video Based Case Study PresentationsDocument1 pageRubrics For Computer Integrated Manufacturing Lab Assessment: Video Based Case Study PresentationsAli NoraizNo ratings yet

- A Needs Analysis For Psychology Students of La Salle College AntipoloDocument12 pagesA Needs Analysis For Psychology Students of La Salle College Antipoloruzzel frijasNo ratings yet

- IPCRF Transmittal 2021Document1 pageIPCRF Transmittal 2021KeyrenNo ratings yet

- Portfolio Guidelines For Unit 7 1: First Day of Class November 29 - Last Day of Class December 23Document7 pagesPortfolio Guidelines For Unit 7 1: First Day of Class November 29 - Last Day of Class December 23Edith BaosNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Learning: NCM102 Health Education AY 2020-2021 Prepared By: Arvee Macanaya, MSNDocument40 pagesDeterminants of Learning: NCM102 Health Education AY 2020-2021 Prepared By: Arvee Macanaya, MSNchichiNo ratings yet

- Eapp Q1-L1Document9 pagesEapp Q1-L1Jeanica Delacosta CesponNo ratings yet

- Q2 HEALTH8 Wk1 Dating CourtshipDocument15 pagesQ2 HEALTH8 Wk1 Dating CourtshipThaliafaith ArdienteNo ratings yet

- CV Jin 10252021Document4 pagesCV Jin 10252021mamun wasimNo ratings yet

- Students PerceptionsDocument11 pagesStudents PerceptionsHidayah RamlanNo ratings yet

- Pediatrics-30.06.2020 FN Grief & Bereavement, Role of A Pediatric Nurse and Principles of Pre and Post Operative CareDocument63 pagesPediatrics-30.06.2020 FN Grief & Bereavement, Role of A Pediatric Nurse and Principles of Pre and Post Operative CareAjeeshNo ratings yet

- Biblical Greek For Ministry 1: GRK 2610 DDocument4 pagesBiblical Greek For Ministry 1: GRK 2610 DEmanuel ValdezNo ratings yet

- Week 03 - Time ManagementDocument18 pagesWeek 03 - Time ManagementMUSIC & TECHNo ratings yet

- Declarative Vs Procedural KnowledgeDocument1 pageDeclarative Vs Procedural KnowledgeJabir AliyiNo ratings yet

- Persuasive Communication: Persuade, and RemindDocument8 pagesPersuasive Communication: Persuade, and RemindRahul Pawar100% (1)

- History of MSNDocument20 pagesHistory of MSNSyamVRNo ratings yet

- PhysEd11 ScriptDocument3 pagesPhysEd11 ScriptChaseNo ratings yet

- Annual Report 2013 14 English HalDocument136 pagesAnnual Report 2013 14 English HalDivansu D BansalNo ratings yet

- Nurse 2 FDocument2 pagesNurse 2 FEllaNo ratings yet

- Nilai Pendidikan Agama Hindu Dalam Lontar Siwa Sasana: Ida Bagus Putu Eka Suadnyana, I Putu Ariyasa DarmawanDocument21 pagesNilai Pendidikan Agama Hindu Dalam Lontar Siwa Sasana: Ida Bagus Putu Eka Suadnyana, I Putu Ariyasa DarmawanKomang gde TantraNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Application Bilingual ClassDocument4 pagesAnalysis of Application Bilingual ClassIka Yogi Wirawan PutraNo ratings yet

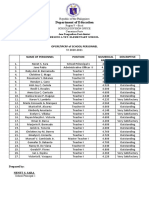

- Department of Education: Training MatrixDocument3 pagesDepartment of Education: Training MatrixJohn Lester Ysug AlenoidNo ratings yet

Non Communicable Disease in Childern and Adolescent

Non Communicable Disease in Childern and Adolescent

Uploaded by

Renov OmpusungguOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Non Communicable Disease in Childern and Adolescent

Non Communicable Disease in Childern and Adolescent

Uploaded by

Renov OmpusungguCopyright:

Available Formats

CONTRIBUTORS: Jenny Proimos, MB BS, MPH, FRACP,a,b and Jonathan D.

Klein, MD, MPH, FAAPc,d

a

Department of Pediatrics, University of Melbourne, Centre for Adolescent

Health, Royal Children’s Hospital, Parkville, Victoria, Australia; bVictoria

Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, Victoria, Australia;

c

American Academy of Pediatrics, Elk Grove Village, Illinois; and dUniversity of

Rochester School of Medicine, Rochester, New York

Dr Proimos is a member and Dr Klein is chair of the International Pediatric

Association Technical Advisory Group on Noncommunicable Diseases. The

International Pediatric Association is a nongovernmental organization of 144

national, regional, and international specialty pediatric societies.

Accepted for publication Jun 4, 2012

ABBREVIATION

NCD—noncommunicable disease

doi:10.1542/peds.2012-1475

Noncommunicable Diseases in Children and

Adolescents

We have made great progress in these most common health issues of In September 2011, the United Nations

preventing and managing commu- our time. General Assembly declaration on pre-

nicable diseases worldwide. Non- —Jay E. Berkelhamer, MD vention and control of NCDs first ac-

communicable diseases (NCDs), which knowledged the increasing impact of

Editor, Global Health Perspectives

result from noninfectious and non- NCDs on children and adolescents and

transmissible factors, are often Recent global attention has focused on recognized the need to protect them

caused by factors that are modifiable. NCDs and their impact on global mor- from NCDs.5

Children are the frequent victims of bidity and mortality. NCDs are medical

air pollution and behaviors such as conditions or diseases that are non-

tobacco use, physical inactivity, and transmissible and often enduring. Of CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS ARE

unhealthy diets leading to the de- the 57 million deaths worldwide in 2008, HEAVILY IMPACTED BY NCDS

velopment of the NCDs discussed in NCDs accounted for 36 million, mainly • 1.2 million children and youth under

this global health perspectives com- due to cardiovascular disease, cancers, age 20 died of NCDs in 20026

mentary. The worldwide burden of diabetes, and chronic lung diseases.1

• More than 25% of obese adolescents

NCDs is enormous, actually account- Eighty percent of NCD deaths occur in

have signs of diabetes by age 157

ing for the majority of all deaths. low and middle income countries.2

• Despite improvements in survival for

Risk factors such as high blood NCDs often result from modifiable life-

some childhood cancers,8 survival is

pressure, raised cholesterol, tobacco style risk factors, such as tobacco use,

much lower in resource-poor coun-

use, alcohol consumption, and over- problem alcohol use, unhealthy diet, and

tries

weight coupled with poor economic lack of physical activity, leading to

and social conditions create a per- overweight, raised blood pressure, and • 90% of the 1 million children born

fect storm for many of the world’s cholesterol. Left unchecked, NCDs will each year with congenital heart dis-

chronic illnesses diseases. Drs Proimos continue to lower global productivity, ease live in areas without adequate

and Klein bring new focus to threaten quality of life, and cost trillions medical care9

the pediatric perspective and sug- of dollars.3 Systematic efforts to prevent • Tobacco smoke causes asthma, oti-

gest an approach to developing NCDs, and ameliorate their burden, are tis, and respiratory infections in

strategies internationally to combat now part of a global health strategy.4 children10

PEDIATRICS Volume 130, Number 3, September 2012 379

Downloaded from pediatrics.aappublications.org by guest on May 9, 2015

• Mental health disorders,11 motor papilloma virus and hepatitis B) are Advocacy for child and adolescent

vehicle trauma, homicide, and sui- examples of effective primary pre- NCD efforts must encourage coun-

cide12 cause significant morbidity vention that have successfully mobi- tries to develop and implement ef-

and mortality in children and lized international resources to help fective monitoring and surveillance

youth the world’s poorest countries.21 NCD systems. Advocacy is also needed to

efforts must collaborate with maternal, ensure that child and adolescent

RISK FACTORS AND BEHAVIORS newborn, and child health systems health targets are included in the

LEADING TO ADULT NCDS START IN to achieve efficiency and effective- monitoring framework and targets

CHILDHOOD ness and must also address the being set by the United Nations for

social determinants of health and NCDs. The International Pediatric As-

Prenatal exposure to tobacco and al-

disease. This includes promoting ed- sociation, American Academy of Pe-

cohol, prematurity and low birth weight,

ucation, which benefits both lifestyle diatrics, and other national pediatric

nutritional deficiency, and diabetes have

choices and health outcomes, and societies have called on countries to

long-term impacts on health and de-

also community productivity and pay specific attention to children and

velopment, including increased risk of

social stability.22 Living conditions, air adolescents in developing national to-

adult cardiovascular disease, diabetes,

and water pollution, and adequate bacco, alcohol, mental health, chronic

and other social and medical problems

sanitation and open spaces all should illness, nutrition and physical activity,

later in life.13 It is important to focus

be considered by governments in and reproductive health goals. A broad

on prenatal care, healthy nutrition in

developing policies to promote child coalition of family advocates and clin-

pregnancy, and breastfeeding. Safe

health. ical groups, the NCD Child Network,

deliveries, effective resuscitation, and

has also called on the global com-

postnatal care with adequate immuni- Strengthening child and adolescent

munity to (1) focus attention on NCDs

zations and safe, smoke-free environ- health systems is essential if low- and

in children and adolescents, (2) ad-

ments also help prevent the burden of middle-income countries are to de-

vance policies and interventions that

chronic care for children and their velop comprehensive approaches

ensure maternal and child health sys-

families. to prevention and management of

tems become engaged in development

The onset of risk behaviors predis- NCDs. Comprehensive family centered

of NCD prevention and management,

posing to NCDs often occurs in chil- “medical home” based care systems

and (3) assist nations in addressing a

dren and adolescents. Globally, 100 000 (www.medicalhomeinfo.org), integrat-

life-course approach to the prevention

young people start smoking each ing primary care for children and

and management of NCDs among chil-

day,14 and over 90% of adults who youth with community public health

dren and adolescents at all levels of

smoke started as children or youth.15 systems, are a useful model for a

the health care system.27

Adolescent alcohol consumption is com- comprehensive, multilevel approach to

mon, risking brain development, nonin- NCD prevention and management. In-

tentional injury and violence, and alcohol creasingly, young people themselves CONCLUSIONS

dependence in adulthood.16,17 Overweight have also been engaged as active par- Childhood and adolescence are crucial

and obesity are increasing in high-income ticipants in promoting community times for the prevention of NCDs. A life-

countries and in low- and middle- health and social services that meet course approach to prevention, di-

income countries,10,18 with increased their needs.23 agnosis, and management may result

risk of diabetes and cardiovascular The United Nations global strategy in significant gains in health outcomes,

disease.19 calls for comprehensive monitoring of global productivity, and health care

A life course approach to preventive trends and progress in implementation savings. Measuring progress in health

efforts addressing NCDs and their risk of national plans and recommendations outcome trends is a first step to being

factors and behaviors will improve for voluntary global targets for pre- able to monitor the impact of NCD

child and adolescent health but also vention and control of NCDs.24,25 Mon- prevention. Advocacy by child health

decrease lifetime health care costs.20 itoring is crucial to inform policy; leaders for equitable inclusion of

This approach recognizes that adult however, many countries do not col- children and adolescents in NCD goals

health and disease risk develops early lect comparable mortality and NCD by countries is critically needed to

in life and can affect disease states data.26 Only one-third of the world’s ensure that countries’ NCD efforts in-

and risks across generations.20 Vaccine- population lives in areas where births clude support for child and adoles-

preventable NCD programs (eg, human and deaths are accurately registered. cent health.

380 PROIMOS and KLEIN

Downloaded from pediatrics.aappublications.org by guest on May 9, 2015

PEDIATRICS PERSPECTIVES

REFERENCES 9. Tchervenkov CI, Jacobs JP, Bernier PL, et al. 18. Wang Y, Lobstein T. Worldwide trends in

The improvement of care for paediatric childhood overweight and obesity. Int J

1. Alwan A, Maclean DR, Riley LM, et al.

and congenital cardiac disease across the Pediatr Obes. 2006;1(1):11–25

Monitoring and surveillance of chronic

World: a challenge for the World Society for 19. Must A, Strauss RS. Risks and conse-

non-communicable diseases: progress and

Pediatric and Congenital Heart Surgery. quences of childhood and adolescent obe-

capacity in high-burden countries. Lancet.

Cardiol Young. 2008;18(suppl 2):63–69 sity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23

2010;376(9755):1861–1868

10. The NCD Alliance. A Focus on Children and (suppl 2):S2–S11

2. World Health Organization. Global Status

Adolescents: Key Recommendations on Tar- 20. Catalano RF, Fagan AA, Gavin LE, et al.

Report on Non-Communicable Diseases

2010. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health gets to Monitor Progress in Reducing the Worldwide application of prevention sci-

Organization; 2011 Burden of Non-Communicable Diseases ence in adolescent health. Lancet. 2012;379

(NCDs); 2012. Available at: http://ncdalliance. (9826):1653–1664

3. Bloom D, ed. The Global Economic Burden

org/sites/default/files/rfiles20110627_A_ 21. Monk BJ, Wiley DJ. Will widespread human

on Non-Communicable Diseases. Geneva,

Focus_on_Children_&_NCDs_FINAL_2.pdf. papillomavirus prophylactic vaccination

Switzerland: World Economic Forum; 2011

Accessed June 19, 2012 change sexual practices of adolescent and

4. World Health Organization. Action Plan

11. Patel V, Flisher AJ, Hetrick S, McGorry P. Mental young adult women in America? Obstet

for the Global Strategy for the Prevention

health of young people: a global public-health Gynecol. 2006;108(2):420–424

and Control of Noncommunicable Dis-

challenge. Lancet. 2007;369(9569):1302–1313 22. Viner RM, Ozer EM, Denny S, et al. Adoles-

eases. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health

Organization; 2008 12. Gore FM, Bloem PJ, Patton GC, et al. Global cence and the social determinants of

burden of disease in young people aged 10- health. Lancet. 2012;379(9826):1641–1652

5. United Nations. Political declaration of the

24 years: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 23. Adamchak S. Youth Peer Education in Re-

high-level meeting of the general assem-

2011;377(9783):2093–2102 productive Health and HIV/AIDS. Arlington, VA:

bly on the prevention and control of non-

communicable diseases; September 16, 2011; 13. Gluckman P, Hanson M; University of Family Health International/YouthNet; 2006.

New York, NY: United Nations General As- Auckland. Developmental Origins of Health Available at: http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/

sembly; 2011 and Disease. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge PNADI607.pdf. Accessed June 19, 2012

University Press; 2006

6. Mathers C. Global Burden of Disease 24. World Health Organization. Action Plan for

Among Women, Children, and Adolescents. 14. Shafey O. The Tobacco Atlas. 3rd ed. the Global Strategy for the Prevention and

Maternal and Child Health: Global Chal- Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2010 Control of Noncommunicable Disease Con-

lenges, Programs, and Policies. New York, 15. National Centre for Chronic Disease Pre- trol. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Or-

NY: Springer; 2009:19–42 vention and Health Promotion. Youth To- ganization; 2008

7. Goran MI, Ball GD, Cruz ML. Obesity and risk bacco Surveillance - United States. 2000. 25. World Health Organization. WHO Discussion

of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular dis- MMWR Surveill Summ. 2001;50(SS04):1–84 Paper: A comprehensive global monitoring

ease in children and adolescents. J Clin 16. Bonomo YA, Bowes G, Coffey C, Carlin JB, framework and voluntary global targets for

Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(4):1417–1427 Patton GC. Teenage drinking and the onset the prevention and control of NCDs. Geneva,

8. Cancer Research UK. Childhood cancer of alcohol dependence: a cohort study over Switzerland: World Health Organization;

statistics: survival. Available at: http:// seven years. Addiction. 2004;99(12):1520–1528 2011 Updated version December 21, 2011

info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/ 17. DeWit DJ, Adlaf EM, Offord DR, Ogborne AC. 26. Patton GC, Coffey C, Cappa C, et al. Health of

childhoodcancer/survival/childhood-cancer- Age at first alcohol use: a risk factor for the world’s adolescents: a synthesis of in-

survival-statistics. Accessed November 5, the development of alcohol disorders. Am J ternationally comparable data. Lancet.

2011 Psychiatry. 2000;157(5):745–750 2012;379(9826):1665–1675

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: No external funding.

PEDIATRICS Volume 130, Number 3, September 2012 381

Downloaded from pediatrics.aappublications.org by guest on May 9, 2015

Noncommunicable Diseases in Children and Adolescents

Jenny Proimos and Jonathan D. Klein

Pediatrics 2012;130;379; originally published online August 13, 2012;

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2012-1475

Updated Information & including high resolution figures, can be found at:

Services http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/130/3/379.full.ht

ml

Subspecialty Collections This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in

the following collection(s):

Adolescent Health/Medicine

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/adolescent

_health:medicine_sub

Permissions & Licensing Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures,

tables) or in its entirety can be found online at:

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xh

tml

Reprints Information about ordering reprints can be found online:

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

PEDIATRICS is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly

publication, it has been published continuously since 1948. PEDIATRICS is owned, published,

and trademarked by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 141 Northwest Point Boulevard, Elk

Grove Village, Illinois, 60007. Copyright © 2012 by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All

rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0031-4005. Online ISSN: 1098-4275.

Downloaded from pediatrics.aappublications.org by guest on May 9, 2015

Noncommunicable Diseases in Children and Adolescents

Jenny Proimos and Jonathan D. Klein

Pediatrics 2012;130;379; originally published online August 13, 2012;

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2012-1475

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

located on the World Wide Web at:

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/130/3/379.full.html

PEDIATRICS is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly

publication, it has been published continuously since 1948. PEDIATRICS is owned,

published, and trademarked by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 141 Northwest Point

Boulevard, Elk Grove Village, Illinois, 60007. Copyright © 2012 by the American Academy

of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0031-4005. Online ISSN: 1098-4275.

Downloaded from pediatrics.aappublications.org by guest on May 9, 2015

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5822)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Academic Motivation Scale College VersionDocument4 pagesAcademic Motivation Scale College VersionJyothi MallyaNo ratings yet

- Roles of TeacherDocument5 pagesRoles of TeacherCharlynjoy Abañas67% (3)

- Analysis and Control of Underactuated Mechanical SystemsDocument148 pagesAnalysis and Control of Underactuated Mechanical SystemsDjelejnyNo ratings yet

- Explode The Code Book 1 Is The First Book in TheDocument10 pagesExplode The Code Book 1 Is The First Book in TheSurabhi Gupta ThakurNo ratings yet

- Frequencies: NotesDocument37 pagesFrequencies: NotesRenov OmpusungguNo ratings yet

- Standard Treatment Guidelines HaemodialysisDocument12 pagesStandard Treatment Guidelines HaemodialysisRenov OmpusungguNo ratings yet

- Flow Ands Cardiac ComplicationsDocument4 pagesFlow Ands Cardiac ComplicationsRenov OmpusungguNo ratings yet

- Takikardi RelatifDocument7 pagesTakikardi RelatifRenov OmpusungguNo ratings yet

- Group 1 Subjects Ca Inter - Google SearchDocument1 pageGroup 1 Subjects Ca Inter - Google Searchy7frhdvm5fNo ratings yet

- SDTS User Guide v2 0Document32 pagesSDTS User Guide v2 0jeffNo ratings yet

- S.K.S. Group of Institutions: (A) College FeeDocument1 pageS.K.S. Group of Institutions: (A) College FeeIsaac EdusahNo ratings yet

- Every Day Sometimes Always Often Usually Seldom Never First ... ThenDocument5 pagesEvery Day Sometimes Always Often Usually Seldom Never First ... ThenMuhammad PersadaNo ratings yet

- Board of Regents V RothDocument1 pageBoard of Regents V Rothapi-240190507No ratings yet

- Rubrics For Computer Integrated Manufacturing Lab Assessment: Video Based Case Study PresentationsDocument1 pageRubrics For Computer Integrated Manufacturing Lab Assessment: Video Based Case Study PresentationsAli NoraizNo ratings yet

- A Needs Analysis For Psychology Students of La Salle College AntipoloDocument12 pagesA Needs Analysis For Psychology Students of La Salle College Antipoloruzzel frijasNo ratings yet

- IPCRF Transmittal 2021Document1 pageIPCRF Transmittal 2021KeyrenNo ratings yet

- Portfolio Guidelines For Unit 7 1: First Day of Class November 29 - Last Day of Class December 23Document7 pagesPortfolio Guidelines For Unit 7 1: First Day of Class November 29 - Last Day of Class December 23Edith BaosNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Learning: NCM102 Health Education AY 2020-2021 Prepared By: Arvee Macanaya, MSNDocument40 pagesDeterminants of Learning: NCM102 Health Education AY 2020-2021 Prepared By: Arvee Macanaya, MSNchichiNo ratings yet

- Eapp Q1-L1Document9 pagesEapp Q1-L1Jeanica Delacosta CesponNo ratings yet

- Q2 HEALTH8 Wk1 Dating CourtshipDocument15 pagesQ2 HEALTH8 Wk1 Dating CourtshipThaliafaith ArdienteNo ratings yet

- CV Jin 10252021Document4 pagesCV Jin 10252021mamun wasimNo ratings yet

- Students PerceptionsDocument11 pagesStudents PerceptionsHidayah RamlanNo ratings yet

- Pediatrics-30.06.2020 FN Grief & Bereavement, Role of A Pediatric Nurse and Principles of Pre and Post Operative CareDocument63 pagesPediatrics-30.06.2020 FN Grief & Bereavement, Role of A Pediatric Nurse and Principles of Pre and Post Operative CareAjeeshNo ratings yet

- Biblical Greek For Ministry 1: GRK 2610 DDocument4 pagesBiblical Greek For Ministry 1: GRK 2610 DEmanuel ValdezNo ratings yet

- Week 03 - Time ManagementDocument18 pagesWeek 03 - Time ManagementMUSIC & TECHNo ratings yet

- Declarative Vs Procedural KnowledgeDocument1 pageDeclarative Vs Procedural KnowledgeJabir AliyiNo ratings yet

- Persuasive Communication: Persuade, and RemindDocument8 pagesPersuasive Communication: Persuade, and RemindRahul Pawar100% (1)

- History of MSNDocument20 pagesHistory of MSNSyamVRNo ratings yet

- PhysEd11 ScriptDocument3 pagesPhysEd11 ScriptChaseNo ratings yet

- Annual Report 2013 14 English HalDocument136 pagesAnnual Report 2013 14 English HalDivansu D BansalNo ratings yet

- Nurse 2 FDocument2 pagesNurse 2 FEllaNo ratings yet

- Nilai Pendidikan Agama Hindu Dalam Lontar Siwa Sasana: Ida Bagus Putu Eka Suadnyana, I Putu Ariyasa DarmawanDocument21 pagesNilai Pendidikan Agama Hindu Dalam Lontar Siwa Sasana: Ida Bagus Putu Eka Suadnyana, I Putu Ariyasa DarmawanKomang gde TantraNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Application Bilingual ClassDocument4 pagesAnalysis of Application Bilingual ClassIka Yogi Wirawan PutraNo ratings yet

- Department of Education: Training MatrixDocument3 pagesDepartment of Education: Training MatrixJohn Lester Ysug AlenoidNo ratings yet