Professional Documents

Culture Documents

(Littlehales G.W.) The Problems and Functions of T (BookFi)

(Littlehales G.W.) The Problems and Functions of T (BookFi)

Uploaded by

Pallav Jain0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

12 views4 pagesThe document summarizes the history and progress of physical oceanography as a field of study. It outlines major oceanographic expeditions by different nations from the late 19th to early 20th centuries that contributed to accumulating observations about the ocean's physical characteristics. It then describes current approaches like studying fixed stations over time to understand variations, and highlights ongoing American programs gathering long-term data on temperature, salinity, currents and more in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. The section aims to coordinate such efforts to advance oceanography.

Original Description:

Original Title

[Littlehales_G.W.]_The_Problems_and_Functions_of_t(BookFi)

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe document summarizes the history and progress of physical oceanography as a field of study. It outlines major oceanographic expeditions by different nations from the late 19th to early 20th centuries that contributed to accumulating observations about the ocean's physical characteristics. It then describes current approaches like studying fixed stations over time to understand variations, and highlights ongoing American programs gathering long-term data on temperature, salinity, currents and more in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. The section aims to coordinate such efforts to advance oceanography.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

12 views4 pages(Littlehales G.W.) The Problems and Functions of T (BookFi)

(Littlehales G.W.) The Problems and Functions of T (BookFi)

Uploaded by

Pallav JainThe document summarizes the history and progress of physical oceanography as a field of study. It outlines major oceanographic expeditions by different nations from the late 19th to early 20th centuries that contributed to accumulating observations about the ocean's physical characteristics. It then describes current approaches like studying fixed stations over time to understand variations, and highlights ongoing American programs gathering long-term data on temperature, salinity, currents and more in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. The section aims to coordinate such efforts to advance oceanography.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 4

580 GEOPHYSICS: G. W. LITTLEHALES PROC. N. A.

S,

6 Terrestrial Magnetism and Atmospheric Electricity, 24, June, 1919 (96).

7See Terrestrial Magnetism and Atmospheric Electricity, 19, 1914 (57-72, 189-203);

also Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 4, 1914 (204-214).

8 See Publications of St. Louis Congress of Arts and Science, 4, 1904 (750-756).

9 Palmieri, L., "Osservaziones delle correnti telluriche," Rend. d'Acad. Napoli, 3,

1890 (225, 250); 4 (164, 228); 5 (216).

THE PROBLEMS AND FUNCTIONS OF THE SECTION OF

PHYSICAL OCEANOGRAPHY OF THE

AMERICAN GEOPHYSICAL UNION

By G. W. LITTLZHALES

The former and present function of the ocean in the history of the earth

and in its economy has forged bonds of kinship between oceanography

and many other branches of science. Ever since the ocean became the

world-encompassing highway of communication, its surface aspects,

embracing the movements of the waters in waves, tides, and currents,

have been subjects of observation. With the advance of the physical

sciences and a knowledge of the extent of the ocean came the realization

that so large an expanse of a substance having the highest known capacity

for heat must, to a large extent, govern the external temperature of the

earth and exercise an important influence as a factor in geophysics.

But centuries of voyaging did not extend marine observations beyond

the delineation of coasts and the service of navigation; and, in the middle

of the nineteenth century, the sea remained unfathomed, and the observa-

tions of the physicist, the chemist, the geologist, and the biologist did

not extend beyond the shallow coastal waters.

In setting forth the principal deep-sea expeditions, by nations and states,

through the names of the vessels engaged and the period of their service,

we shall serve ourselves the purpose of reflecting the progress of the at-

tempts that have been made to ascertain the physical characteristics of

that vast region of the earth's surface which is occupied by the deeper

waters of the ocean:

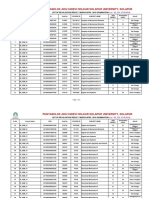

Austria Frangais (1903-5).

Pola (1891-1910). Germany

Belgium National (1889).

Belgica (1897-9). Valdivia (1898-9).

Denmark Gauss (1901-3).

Ingolf (1895-6). Planet (1906-14).

France Great Britain

Travailleur (18 3.Li ghtning (1868).

Talisman } (1803) Porcupine (1869-70).

Caudan (1895). Challenger (1873-6).

Vol. 6, I1920 GEOPHYSICS: G. W. LITTLEHALES 58I

Investigator (1887-1902). Sweden

Discovery (1901-4). Vega (1878-80).

Scotia (1902-4). Antarctic (1901-3).

Holland

William Barents (1878-84). United States

Siboga (1899-1900). Albatross (1883-1920).

Italy Blake (1876-97).

Washington (1881-2). Narragansett (1871-3).

Vettor Pisani (1882-5). Nero (1900).

Norway Thetis (1895).

Voringen (1876-8). Tuscarora (1873-6).

Fram (1893-6).

Gjoa (1903-5). Principality of Monaco

Michael Gars (1900-20) l'Hirondelle (1885-8).

Russia Princesse Alice I (1891-7).

Vitiaz (1886-9). Princesse Alice II (1895-1914).

These expeditions and many others of lesser import, operating for the

most part in seas remote from the countries in which they were fitted out,

have contributed much of the literature of oceanography in which we find

set forth the dynamic meteorology and climatology of the ocean, the

theories of the tides and waves and the observed facts concerning them,

the depths of the ocean, the temperature, the composition and circulation

of oceanic waters, the nature and distribution of marine organisms at the

surface and in the depths, and the origin and distribution of marine de-

posits over the floor of the ocean. But the ocean is so vast that the ac-

cumulation of facts of observation concerning it-extensive though it be

is but a sparse array in geographical distribution and constitutes but a

skeleton of knowledge in relation to the configuration of its basins, the

nature and distribution and thickness and stratification of the deposits

which cover the bottom, and the physical and chemical properties and

movements and mode of operation of its waters in producing their effects

in the economy of the earth.

It is not alone through expeditions upon the ocean that oceanography

has progressed; investigations in marine laboratories and institutions of

research and discoveries in cognate sciences have sometimes yielded more

advancement than distant and perilous voyages.

Advancement in the nature of the application of the philosophy of

method has enabled oceanography to profit in its later stages of develop-

ment. The system according to which progress is now being sought is

the study in detail of definite stations in the ocean occupied in concert,

and, as we hope it will be, by international cooperation, and periodically

revisited for the purpose of observing the variations of physical condition

whose import, when it comes to be understood, will enhance all those

wealth-producing sources which operate in seasonal cycles. Observa-

582 GEOPHYSICS: G. W. LITTLEHALES PROC. N. A. S.

tions of temperature, salinity, gas content, and currents made as nearly

as possible at the same instant at series of points or stations and through-

out a network of lines distributed in the depths beneath a given area of

the ocean, and repeated every three months have afforded the means of

making synoptic charts which disclose the existence of bends or undula-

tions like the waves formed on the boundary surface between water layers

of different densities. It is the mathematical investigation of the varia-

tions with time of the changing network of lines of equal values of the

physical elements in their distribution in the depths that promises to in-

troduce oceanography into the ranks of the exact sciences by enabling

oceanographers, by mathematical laws, to predict effects from a few

observations strategically placed.

Conspicuous among the features of the resumption of American oceano-

graphical operations, after the interruption occasioned by the exigencies

of the late times, are the following: The International Ice Observation

and Ice Patrol Service in the North Atlantic Ocean, employing the vessels

of the United States Coast Guard under an arrangement by which the

cost is shared proportionately by the nations participating in the London

Conference of 1913, is engaged (coordinately with the primary duties of

ascertaining the locations and progressive movements of the limiting

lines of the regions in which icebergs and field ice exist in the vicinity of

the Grand Bank of Newfoundland and the dissemination of the informa-

tion so ascertained for the guidance and warning of navigators) in gather-

ing an important accumulation of oceanographical and meteorological

observations. Year by year, observations at recorded times, extending

from the surface to the bottom, are made in well determined geographical

positions throughout the patrolled region for determining the tempera-

ture and salinity of the, water by readings in series at definite depths, the

direction and rate of movement of the waters in the different depths, the

collection and preservation of plankton and samples of the water from

ascertained depths, and in recording the state of the weather and the sea

together with the barometric pressure, the humidity and the tempera-

ture of the air. These observations are published annually in the Bulle-

tins of the United States Coast Guard, Treasury Department.

Closely related to these investigations from the standpoint of the ad-

vancement of oceanography, is the accumulation of observations result-

ing from the annual returns of the schooner Grampus in the Gulf of Maine

and its vicinity, for the study of the correlation between physical ocean-

ography and biological oceanography in these waters, under the joint

auspices of the United States Bureau of Fisheries and the' Museum of

Comparative Zo6logy of Harvard University.

At La Jolla, near San Diego, California, there has grown up an insti-

tution by the name of the Scripps Institution for Biological Research,

whose operations, recently brought under the auspices of the University

VOL,. 6, I 920 GEOPHYSICS: H. S. WASHINGTON 583

of California, constitute an exemplar of intensive oceanographical investi-

gation. By systematically and repeatedly tabulating and mapping

standardized values of the temperature, salinity, density, currents, and

gas content of the water of the Pacific Ocean, serially observed at ascer-

tained intervals of depth from the surface to the bottom in fixed loca-

tions, the variations of these physical elements, with time and locality, in

their distribution in the depths, have been revealed to an important

extent within the confines of the oceanic tract in the region of the seat

of the Institution, stretching from San Diego to Point Concepcion and em-

bracing an area of more than 10,000 square miles.

It is the present purpose of the Section of Physical Oceanography to

foster the labors of these agencies and the similar ones which are con-

tributed by the Navy and the Coast Survey and to seek opportunities to

supplement them and link their operations, as far as may be, into co6rdi-

nation with the operations of the oceanographers of Japan, of Australia

and New Zealand, of the North Sea International Council of Exploration,

and the Mediterranean Sea International Council of Exploration. And,

through the formation of committees, to provide that consideration shall

be given to the problems of evaporation and heat transference and the

interrelations between oceanography and meteorology, to the problems of

dynamic oceanography including the variations of mean sea-level and the

tides and their manifestations in the depths as well as the surface, to the

investigation of the chemical and physical properties of the waters includ-

ing the penetration of light, to the investigation of the origin and distri-

bution of bottom deposits, to the problem of ascertaining the conforma-

tion and topography of the basins, and to the ways and means of

advancement in the domain of physical oceanography.

THE PROBLEMS OF VOLCANOLOGY

By HENRY S. WASHINGTON

INTRODUCTION

Of the various sciences represented in the American Geophysical Union

that of volcanology is perhaps the most complex and has probably most

points of contact with the other geophysical sciences. This complexity

and variety in the problems presented by the study of volcanoes arises, in

part, from the fact that they are, as has been well said, "natural labora-

tories." Also the distribution and many of the activities of volcanoes

are closely connected with some of the physical, as well as the chemical

forces that are involved in the formation and in the present condition of

the earth.

In presenting some of the main problems of volcanology, we may be-

gin with those that are essentially and more purely volcanological, and

You might also like

- Bcra 11-2-1984Document60 pagesBcra 11-2-1984Cae MartinsNo ratings yet

- Lost Islands: The Story of Islands That Have Vanished from Nautical ChartsFrom EverandLost Islands: The Story of Islands That Have Vanished from Nautical ChartsNo ratings yet

- KP Stats CatalogueDocument16 pagesKP Stats CatalogueKumar SaurabhNo ratings yet

- Eda Group5 Hypothesis TestingDocument32 pagesEda Group5 Hypothesis TestingKyohyunNo ratings yet

- Oceanography: For The Scientific Journal, See - "Ocean Science" Redirects Here. For The Scientific Journal, SeeDocument8 pagesOceanography: For The Scientific Journal, See - "Ocean Science" Redirects Here. For The Scientific Journal, Seeserena lhaineNo ratings yet

- Royal Navy Coastlines: Challenger ExpeditionDocument3 pagesRoyal Navy Coastlines: Challenger ExpeditionreenuNo ratings yet

- Oceanography: For The Scientific Journal, See - "Ocean Science" Redirects Here. For The Scientific Journal, SeeDocument5 pagesOceanography: For The Scientific Journal, See - "Ocean Science" Redirects Here. For The Scientific Journal, SeeSaul AchanccarayNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Descriptive Physical OceanographyDocument6 pagesIntroduction To Descriptive Physical OceanographyDiogo CustodioNo ratings yet

- Royal Navy: Challenger ExpeditionDocument3 pagesRoyal Navy: Challenger ExpeditionreenuNo ratings yet

- Aims of OceanographyDocument26 pagesAims of OceanographyKomal KiranNo ratings yet

- Antarctic Advent U 00 Tay LDocument268 pagesAntarctic Advent U 00 Tay LBranko NikolicNo ratings yet

- Coastal Paleogeography of The Central and Western Mediterranean During The Last 125 000 Years and Its Archaeological ImplicationsDocument9 pagesCoastal Paleogeography of The Central and Western Mediterranean During The Last 125 000 Years and Its Archaeological ImplicationsLukas PerkovićNo ratings yet

- Tidal SedimentologyDocument638 pagesTidal Sedimentologyandreal94100% (1)

- Principles of Tidal Sedimentology PDFDocument638 pagesPrinciples of Tidal Sedimentology PDFandreal94100% (2)

- Module For bsf2 OceaDocument7 pagesModule For bsf2 OceaJanette BrigueraNo ratings yet

- Oceanography - WikipediaDocument14 pagesOceanography - Wikipedianikolatesla12599aNo ratings yet

- Depositional History of The South Atlantic Ocean During The Last 125 Million Years1Document48 pagesDepositional History of The South Atlantic Ocean During The Last 125 Million Years1Rafael Herzog Oliveira SilvaNo ratings yet

- The Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal, Vol. XLIX April-October 1850From EverandThe Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal, Vol. XLIX April-October 1850No ratings yet

- James C. Ingle, JR.: Winds and WavesDocument17 pagesJames C. Ingle, JR.: Winds and WavesAmritesh PandeyNo ratings yet

- CH 1-IntroDocument10 pagesCH 1-IntroAnonymous WCWjddjCcNo ratings yet

- What Is The Best Way To Observe The Ocean?Document26 pagesWhat Is The Best Way To Observe The Ocean?Zaindra HaqkiemNo ratings yet

- Antarctica As An Exploration Frontier - Hydrocarbon Potential, Geology, and Hazards PDFDocument157 pagesAntarctica As An Exploration Frontier - Hydrocarbon Potential, Geology, and Hazards PDFMarty LeipzigNo ratings yet

- AntarticaDocument23 pagesAntarticaIrene Depetris-ChauvinNo ratings yet

- The Flow of Homogeneous Fluids Through Porous Media by M. MuskatDocument3 pagesThe Flow of Homogeneous Fluids Through Porous Media by M. MuskatFlowersPondNo ratings yet

- Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology: An Earth System PerspectiveDocument20 pagesPaleoceanography and Paleoclimatology: An Earth System PerspectivejohnwcaragNo ratings yet

- Lowe 2014Document13 pagesLowe 2014Guilherme de Souza AmaralNo ratings yet

- Plate TectonicsDocument71 pagesPlate TectonicsAlberto Ricardo100% (1)

- Scimag 1880 v001 n01Document21 pagesScimag 1880 v001 n01Ilia EframovichtNo ratings yet

- Dickey 1997 Gravity of HydrosphereDocument10 pagesDickey 1997 Gravity of Hydrospheredaniel nyalanduNo ratings yet

- The Cambridge Anthropological Expedition To Torres Straits and S 1899Document6 pagesThe Cambridge Anthropological Expedition To Torres Straits and S 1899MUPyP comunidadNo ratings yet

- Introduction To A Collection of Papers On Warm-Core RingsDocument3 pagesIntroduction To A Collection of Papers On Warm-Core Ringssonu RahulNo ratings yet

- Hickman 1985Document3 pagesHickman 1985DiegoAlvarezNo ratings yet

- Ramsay - The Physical Geology and Geography of Great Britain (1874)Document402 pagesRamsay - The Physical Geology and Geography of Great Britain (1874)caegeospNo ratings yet

- Fathoming the Ocean: The Discovery and Exploration of the Deep SeaFrom EverandFathoming the Ocean: The Discovery and Exploration of the Deep SeaRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (4)

- Lab Activity 7 Plate TectonicsDocument10 pagesLab Activity 7 Plate TectonicskleinkeaNo ratings yet

- Artifact PortfolioDocument8 pagesArtifact PortfoliodeclancoppingNo ratings yet

- 1996 2 GlobalDocument8 pages1996 2 GlobalLaura HernandezNo ratings yet

- Temas Varios Geológicos: ERR Eill Rbani Pikings Arry ArneyDocument11 pagesTemas Varios Geológicos: ERR Eill Rbani Pikings Arry ArneyAdonis LemusNo ratings yet

- Syllabus - Oceanography - An Introduction To The Marine EnvironmentDocument6 pagesSyllabus - Oceanography - An Introduction To The Marine EnvironmentMitchNo ratings yet

- Physical MeasurementsDocument11 pagesPhysical Measurementscgkiran_kumar100% (1)

- Hartman 1966 Polychaeta Sedentaria Antarctica LiteDocument166 pagesHartman 1966 Polychaeta Sedentaria Antarctica LiteValentina Sandoval ParraNo ratings yet

- Changing Views of The History of The EarthDocument15 pagesChanging Views of The History of The EarthAnonymous xN6cc3BzmNo ratings yet

- Thompson Et Al. 1994Document13 pagesThompson Et Al. 1994Steph GruverNo ratings yet

- The Ielts HubDocument15 pagesThe Ielts HubTHE IELTS HUBNo ratings yet

- Mysteries Beneath The SeaDocument184 pagesMysteries Beneath The SeaFabio Picasso100% (1)

- Oceanic Observations of the Pacific 1956: The NORPAC AtlasFrom EverandOceanic Observations of the Pacific 1956: The NORPAC AtlasNo ratings yet

- Pleistocene Glaciation in The Southern Lake District of Chile Stephen C. Porter Quaternary Research 16, 263-292 (1981)Document30 pagesPleistocene Glaciation in The Southern Lake District of Chile Stephen C. Porter Quaternary Research 16, 263-292 (1981)chuchatumareNo ratings yet

- Oceanografia 2Document65 pagesOceanografia 2Biagio CalabroNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To The World's Oceans: Study GuideDocument14 pagesAn Introduction To The World's Oceans: Study GuideSerkan SancakNo ratings yet

- Đề Cương Reading 1Document17 pagesĐề Cương Reading 1Vũ Thùy Bảo TrâmNo ratings yet

- Nat Land 1974Document126 pagesNat Land 1974Juan Guzmán SantosNo ratings yet

- World Prehistory From The Margins: The Role of Coastlines in Human EvolutionDocument12 pagesWorld Prehistory From The Margins: The Role of Coastlines in Human EvolutionEdi BackyNo ratings yet

- Geologic Time - Concepts and PrinciplesDocument5 pagesGeologic Time - Concepts and PrinciplesChaterine ArsantiNo ratings yet

- Dumont Et Al 1996 NEOTECTONICS OF THE COASTAL REGION OF ECUADORDocument4 pagesDumont Et Al 1996 NEOTECTONICS OF THE COASTAL REGION OF ECUADORMilton Agustin GonzagaNo ratings yet

- Australia Archeology - EditedDocument17 pagesAustralia Archeology - Editedjoseph mainaNo ratings yet

- The Archaeology of The Norse North AtlanticDocument22 pagesThe Archaeology of The Norse North AtlanticOdinsvin100% (1)

- Insights Daily Current Affairs PIB 08 June 2019Document13 pagesInsights Daily Current Affairs PIB 08 June 2019Pallav JainNo ratings yet

- (Louise Lyle, David McCallam) Histoires de La Terr (BookFi) PDFDocument273 pages(Louise Lyle, David McCallam) Histoires de La Terr (BookFi) PDFPallav Jain100% (1)

- (Judith Bazler) Earth Science Resources in The Ele (BookFi)Document320 pages(Judith Bazler) Earth Science Resources in The Ele (BookFi)Pallav JainNo ratings yet

- (John S. Stuckless, Robert A. Levich) The Geology (BookFi)Document212 pages(John S. Stuckless, Robert A. Levich) The Geology (BookFi)Pallav Jain100% (1)

- (Marcia S. Freeman) Rourkeis Enciclipaedia World o (BookFi)Document61 pages(Marcia S. Freeman) Rourkeis Enciclipaedia World o (BookFi)Pallav JainNo ratings yet

- Practice Problems For NeetDocument359 pagesPractice Problems For NeetPrudhvi Nath0% (2)

- List of SchoolsDocument4 pagesList of SchoolsPallav JainNo ratings yet

- Neet (Aipmt) PDFDocument114 pagesNeet (Aipmt) PDFPallav JainNo ratings yet

- Start From Here : Previous Papers SolutionsDocument3 pagesStart From Here : Previous Papers SolutionsPallav JainNo ratings yet

- NIACL Assistant Model/ Previous Paper: Test - I: General AwarenessDocument29 pagesNIACL Assistant Model/ Previous Paper: Test - I: General AwarenessPallav JainNo ratings yet

- Ashoka Youth Venture Programme: Changemaker Impact ReportDocument36 pagesAshoka Youth Venture Programme: Changemaker Impact ReportPallav JainNo ratings yet

- FPBAI Membership Form 4Document4 pagesFPBAI Membership Form 4Pallav Jain100% (1)

- Summative Test: Newton'S Law of MotionDocument2 pagesSummative Test: Newton'S Law of MotionOchia Justine100% (2)

- Craig2016.traditions in Communication TheoryDocument10 pagesCraig2016.traditions in Communication TheoryDelia ConstandaNo ratings yet

- Punyashlok Ahilyadevi Holkar Solapur University, Solapur: List of Revaluation Result March/April - 2019 ExaminationDocument9 pagesPunyashlok Ahilyadevi Holkar Solapur University, Solapur: List of Revaluation Result March/April - 2019 ExaminationAmruta JadhavNo ratings yet

- W1 Module 1Document9 pagesW1 Module 1jrenceNo ratings yet

- Research Paper That Uses AnovaDocument4 pagesResearch Paper That Uses Anovaiiaxjkwgf100% (3)

- DLL (Agham at Teknolohiya)Document5 pagesDLL (Agham at Teknolohiya)mary joyce ariemNo ratings yet

- Group 1 Research No. 1 I. Title: Learning Syles of Sophomore Students of PupDocument4 pagesGroup 1 Research No. 1 I. Title: Learning Syles of Sophomore Students of PupAe RaNo ratings yet

- Human SocietyDocument7 pagesHuman SocietyJasmine Soriano HanschkeNo ratings yet

- Research Chapter 3Document3 pagesResearch Chapter 3Yvannah BasanesNo ratings yet

- GRADE 7 Summative 6Document3 pagesGRADE 7 Summative 6Nick Cris GadorNo ratings yet

- Analisis Pengelolaan Barang Milik Daerah PapuaDocument16 pagesAnalisis Pengelolaan Barang Milik Daerah PapuaSiti QomariyahNo ratings yet

- PhD-Mathematics Prospectus 2023-24Document8 pagesPhD-Mathematics Prospectus 2023-24Antim KushawahaNo ratings yet

- Roman ContributionsDocument4 pagesRoman Contributionsapi-378326551No ratings yet

- Project-Based Learning vs. Problem-Based Learning VsDocument3 pagesProject-Based Learning vs. Problem-Based Learning VsAbdelbaset HaridyNo ratings yet

- Contigency Table Excercise - SPSSDocument17 pagesContigency Table Excercise - SPSSIram NisaNo ratings yet

- BIDNEY 1950 American AnthropologistDocument11 pagesBIDNEY 1950 American AnthropologistasturgeaNo ratings yet

- Rice 0570Document125 pagesRice 0570chautruongNo ratings yet

- Research Proposal Using The CHED-GIA Format: Ida H. Revale Bicol University Research & Development CenterDocument45 pagesResearch Proposal Using The CHED-GIA Format: Ida H. Revale Bicol University Research & Development CenterMichael B. TomasNo ratings yet

- Role of Artificial Intelligence in Supply Chain ManagementDocument4 pagesRole of Artificial Intelligence in Supply Chain ManagementBOHR International Journal of Internet of things, Artificial Intelligence and Machine LearningNo ratings yet

- Sns College of Engineering: End Semester Examinations - Nov/Dec 2021 Annexure - IiDocument2 pagesSns College of Engineering: End Semester Examinations - Nov/Dec 2021 Annexure - IiJawaharNo ratings yet

- Methods of Research Calmorin Chapter 1Document46 pagesMethods of Research Calmorin Chapter 1Peter Gonzaga100% (1)

- Case Study Research: An IntroductionDocument13 pagesCase Study Research: An IntroductionVũ TrangNo ratings yet

- Practical Research 2Document11 pagesPractical Research 2BenjaminJrMoronia83% (18)

- Literature Review Research TopicsDocument5 pagesLiterature Review Research Topicsthrbvkvkg100% (1)

- List of Top Aeronautical Engineering Colleges in IndiaDocument12 pagesList of Top Aeronautical Engineering Colleges in IndiaVenuNo ratings yet

- Nstp-Cwts Ii: The National Service Training ProgramDocument10 pagesNstp-Cwts Ii: The National Service Training ProgramELLA SeekNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Submission of Papers For ESSENCEDocument2 pagesGuidelines For Submission of Papers For ESSENCEVineet ChouhanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 - Qualitative ResearchDocument13 pagesChapter 2 - Qualitative ResearchGlyNo ratings yet