Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Brief: Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome

Brief: Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome

Uploaded by

Maria Esther JimenezCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Module 4 RLE Activity NeriDocument9 pagesModule 4 RLE Activity NeriAngela Neri75% (4)

- Hyperleukocytosis, Leukostasis and Leukapheresis Practice ManagementDocument6 pagesHyperleukocytosis, Leukostasis and Leukapheresis Practice ManagementPutri Wulan Sukmawati100% (1)

- Hyperviscosity SyndromeDocument34 pagesHyperviscosity SyndromeSartika Riyandhini100% (1)

- Jessica Reid-Adam: Department of Pediatrics, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NYDocument3 pagesJessica Reid-Adam: Department of Pediatrics, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NYAnastasia Widha SylvianiNo ratings yet

- Henoch-Schonlein PurpuraDocument5 pagesHenoch-Schonlein PurpuraPramita Pramana100% (1)

- Brief: Henoch-Schönlein PurpuraDocument5 pagesBrief: Henoch-Schönlein PurpuraAdrian KhomanNo ratings yet

- HEMOLYTICDocument4 pagesHEMOLYTICzainabd1964No ratings yet

- Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome A Case ReportDocument3 pagesHemolytic Uremic Syndrome A Case ReportAna-Mihaela BalanuțaNo ratings yet

- Pediatric VasculitisDocument17 pagesPediatric VasculitisRam PadronNo ratings yet

- By: DR Najibullah Suhraby FMR First YearDocument33 pagesBy: DR Najibullah Suhraby FMR First YearShami PokhrelNo ratings yet

- Acute GlomerulonephritisDocument4 pagesAcute GlomerulonephritisJulliza Joy PandiNo ratings yet

- Reid Adam2014Document5 pagesReid Adam2014afrilia.iNo ratings yet

- Hyperleukocytosis: Emergency Management: The Indian Journal of Pediatrics November 2012Document6 pagesHyperleukocytosis: Emergency Management: The Indian Journal of Pediatrics November 2012akshayajainaNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Sickle Cell Anemia 1Document11 pagesRunning Head: Sickle Cell Anemia 1api-264952333No ratings yet

- Colitis Isquemica PDFDocument7 pagesColitis Isquemica PDFWaldo ReyesNo ratings yet

- Vasculitis PDFDocument4 pagesVasculitis PDFDiego Ariel Alarcón SeguelNo ratings yet

- Management of HyperleukocytosisDocument10 pagesManagement of HyperleukocytosisNaty AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Universidad Privada San Juan Bautista: Escuela de Medicina HumanaDocument6 pagesUniversidad Privada San Juan Bautista: Escuela de Medicina HumanaKarolLeylaNo ratings yet

- Henoch Schonlein PurpuraDocument3 pagesHenoch Schonlein PurpuraannisaNo ratings yet

- How I Treat TTPDocument10 pagesHow I Treat TTPGhazal KangoNo ratings yet

- Osler-Weber-Rendu Disease - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocument4 pagesOsler-Weber-Rendu Disease - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfanaNo ratings yet

- Sickle Cell enDocument9 pagesSickle Cell enbatraz79No ratings yet

- Hemolytic UremicsyndromeDocument60 pagesHemolytic UremicsyndromeMuhammad AleemNo ratings yet

- Thrombotic Microangiopathy, Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome, and Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic PurpuraDocument16 pagesThrombotic Microangiopathy, Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome, and Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic PurpuraDavidAlbertoMedinaMedinaNo ratings yet

- Journal LeukemiaDocument5 pagesJournal LeukemiaSuwadiaya AdnyanaNo ratings yet

- Hemolytic-Uremic Syndrome in ChildrenDocument17 pagesHemolytic-Uremic Syndrome in ChildrenYuri vanessa Ortiz hNo ratings yet

- Hyperleukocytosis: Emergency ManagementDocument7 pagesHyperleukocytosis: Emergency Managementrivha ramadhantyNo ratings yet

- Application of Ultrasound Elastography in Assesing Portal HypertensionDocument16 pagesApplication of Ultrasound Elastography in Assesing Portal HypertensionValentina IorgaNo ratings yet

- How I Use Hydroxyurea To Treat Young Patients With Sickle Cell Anemia 2Document12 pagesHow I Use Hydroxyurea To Treat Young Patients With Sickle Cell Anemia 2qayyum consultantfpscNo ratings yet

- Sickle CellDocument16 pagesSickle CellAnastasiafynnNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology of Sepsis American Journal of PathologyDocument10 pagesPathophysiology of Sepsis American Journal of PathologyStella Gracia OctaricaNo ratings yet

- Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding in ChildrenDocument24 pagesLower Gastrointestinal Bleeding in ChildrenmacedovendezuNo ratings yet

- Anemia at Older AgeDocument10 pagesAnemia at Older AgeAbdullah ZuhairNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0006497120325088 MainDocument10 pages1 s2.0 S0006497120325088 MainDewi NurpitasariNo ratings yet

- Noncirrhotic Portal Hypertension: ReviewDocument6 pagesNoncirrhotic Portal Hypertension: ReviewIsrael BlancoNo ratings yet

- Summary of Summary 5Document36 pagesSummary of Summary 5anon-265120100% (2)

- Emergencias Hematologicas y OncologicasDocument17 pagesEmergencias Hematologicas y OncologicasFelipe Villarroel RomeroNo ratings yet

- Esophageal Varices: Pathophysiology, Approach, and Clinical DilemmasDocument2 pagesEsophageal Varices: Pathophysiology, Approach, and Clinical Dilemmaskaychi zNo ratings yet

- Sepsis - ClinicalKeyDocument41 pagesSepsis - ClinicalKeyRoberto AndíaNo ratings yet

- 2022 Hepatic EncephalopathyDocument22 pages2022 Hepatic Encephalopathykarina hernandezNo ratings yet

- Anemia en ReumatologiaDocument10 pagesAnemia en ReumatologiaAsunciónNo ratings yet

- Approach To A Child With Pallor and Hepatosplenomegaly: Anirban Das, MD, DMDocument7 pagesApproach To A Child With Pallor and Hepatosplenomegaly: Anirban Das, MD, DMMarc Lyndon CafinoNo ratings yet

- Glomerular Disease in ChildrenDocument8 pagesGlomerular Disease in ChildrenMuti IlmarifaNo ratings yet

- 11 - Shock - Current Diagnosis and Treatment Emergency MedicineDocument18 pages11 - Shock - Current Diagnosis and Treatment Emergency MedicineRon KNo ratings yet

- Portal HypertensionDocument13 pagesPortal HypertensionCiprian BoesanNo ratings yet

- Lo Wo Ho JMTDocument15 pagesLo Wo Ho JMTclaraNo ratings yet

- Approach To A Child With Pallor and Hepatosplenomegaly: Anirban DasDocument8 pagesApproach To A Child With Pallor and Hepatosplenomegaly: Anirban DasvgmanjunathNo ratings yet

- HemeoncalgorithmsDocument11 pagesHemeoncalgorithmsida ayu agung WijayantiNo ratings yet

- Vasculitis: Carol A. Langford, MD, MHS Bethesda, MDDocument11 pagesVasculitis: Carol A. Langford, MD, MHS Bethesda, MDYesid OlidenNo ratings yet

- VASCULITIS by Dr. AJ. 1Document34 pagesVASCULITIS by Dr. AJ. 1Abira KhanNo ratings yet

- What Is HenochDocument7 pagesWhat Is HenochHazel Monique SaysonNo ratings yet

- Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome: Ankit GurjarDocument18 pagesHemolytic Uremic Syndrome: Ankit GurjarAnkit Tonger AnkyNo ratings yet

- Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura and Hemolytic Uremic SyndromeDocument9 pagesThrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura and Hemolytic Uremic SyndromeRex RuthorNo ratings yet

- Myeloproliferative Disordersandthe Hyperviscosity Sy NdromeDocument18 pagesMyeloproliferative Disordersandthe Hyperviscosity Sy NdromeAhmad Harissul IbadNo ratings yet

- Hypertension in Hematologic Malignancies and Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation: An Emerging Issue With The Introduction of Novel TreatmentsDocument8 pagesHypertension in Hematologic Malignancies and Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation: An Emerging Issue With The Introduction of Novel TreatmentsGabryelNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Management of HELLP Syndrome Complicated by Liver HematomaDocument8 pagesDiagnosis and Management of HELLP Syndrome Complicated by Liver HematomaIce 69No ratings yet

- Sepsis and The Systemic Inflammatory Response SyndromeDocument22 pagesSepsis and The Systemic Inflammatory Response SyndromeLaburengkengNo ratings yet

- What Is Acute Glomerulonephritis?: Acute Glomerulonephritis (GN) Comprises A Specific Set of Renal Diseases inDocument6 pagesWhat Is Acute Glomerulonephritis?: Acute Glomerulonephritis (GN) Comprises A Specific Set of Renal Diseases inAnnapoorna SHNo ratings yet

- APSGNDocument3 pagesAPSGNmadimadi11No ratings yet

- SickleDocument6 pagesSickleNalini T GanesanNo ratings yet

- Comprehensive Insights into Acute Arterial Occlusion: Pathways, Prevention, and Holistic CareFrom EverandComprehensive Insights into Acute Arterial Occlusion: Pathways, Prevention, and Holistic CareNo ratings yet

- Spanish Flu ThesisDocument5 pagesSpanish Flu ThesisSomeoneToWriteMyPaperForMeCanada100% (2)

- Predictive Validity of The Post Partum Depression Predictors Inventory Revised PDFDocument6 pagesPredictive Validity of The Post Partum Depression Predictors Inventory Revised PDFAnonymous jmc9IzFNo ratings yet

- Upper Respiratory Tract InfectionDocument45 pagesUpper Respiratory Tract InfectionNatasha Abdulla100% (2)

- 2.02 - Quality and Bioequivalence Guideline - Jul19 - v7 1Document35 pages2.02 - Quality and Bioequivalence Guideline - Jul19 - v7 1vinayNo ratings yet

- Soal PTS 8 - INGGRISDocument10 pagesSoal PTS 8 - INGGRISeciNo ratings yet

- Nephrotic SyndromeDocument20 pagesNephrotic Syndromeami5687No ratings yet

- A 100-Year Journey From GV Black To Minimal Surgical InterventionDocument6 pagesA 100-Year Journey From GV Black To Minimal Surgical InterventionMichael XuNo ratings yet

- Active Management of The Third Stage of LabourDocument25 pagesActive Management of The Third Stage of LabourRedroses flowers0% (1)

- Mat2 FormDocument2 pagesMat2 FormTirso Leo Adelante100% (1)

- Hgfyjgf 7 IuDocument2 pagesHgfyjgf 7 IuPavan KumarNo ratings yet

- Drug StudyDocument2 pagesDrug StudyShayne Jessemae Almario100% (1)

- Rev Sistemática - Effectiveness of Medical Nutrition Therapy in Adolescents With TD1Document13 pagesRev Sistemática - Effectiveness of Medical Nutrition Therapy in Adolescents With TD1Nayesca GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Seven Countries Study A Scientific Adventure in C-Wageningen University and Research 287595Document220 pagesSeven Countries Study A Scientific Adventure in C-Wageningen University and Research 287595Jorge CabezasNo ratings yet

- Management of The Short Bowel Syndrome in Adults - UpToDateDocument10 pagesManagement of The Short Bowel Syndrome in Adults - UpToDateyessyNo ratings yet

- Clinical Teaching ON Geriatric AssessmentDocument9 pagesClinical Teaching ON Geriatric AssessmentANITTA SNo ratings yet

- Protocol and Thesis WritingDocument48 pagesProtocol and Thesis WritingPragya ShahNo ratings yet

- Ict in MedicineDocument9 pagesIct in MedicineObiegba V Fidelis50% (2)

- Module 1Document25 pagesModule 1AlbertDatu100% (1)

- CD003425Document14 pagesCD003425sarahloba100No ratings yet

- dwn150082F ns210 1602080177Document9 pagesdwn150082F ns210 1602080177Cindy ParamitaaNo ratings yet

- Megacolon Toxic of Idiophatic Origin: Case ReportDocument6 pagesMegacolon Toxic of Idiophatic Origin: Case ReportgayutNo ratings yet

- Povidone Iodine: Useful For More Than Preoperative AntisepsisDocument4 pagesPovidone Iodine: Useful For More Than Preoperative AntisepsisNur AjiNo ratings yet

- APPENDICITISDocument15 pagesAPPENDICITISTiffany AdriasNo ratings yet

- Effectivity of Vernonia Cinerea As An Anti-Microbial SalveDocument13 pagesEffectivity of Vernonia Cinerea As An Anti-Microbial SalveK8Y KattNo ratings yet

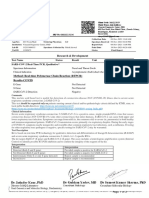

- Research & Development: Test Name Status Result Unit Reference Interval SARS-COV-2 Real-Time PCR, QualitativeDocument2 pagesResearch & Development: Test Name Status Result Unit Reference Interval SARS-COV-2 Real-Time PCR, QualitativeakashNo ratings yet

- Birthasphyxia 160328161503Document20 pagesBirthasphyxia 160328161503Noto SusantoNo ratings yet

- (6-22) DR Takele ManuscriptDocument17 pages(6-22) DR Takele Manuscriptchernet bekeleNo ratings yet

- Avarana in VyadhiDocument4 pagesAvarana in VyadhiSamhitha Ayurvedic ChennaiNo ratings yet

- Megan Reineck: EducationDocument3 pagesMegan Reineck: EducationMegan ReineckNo ratings yet

Brief: Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome

Brief: Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome

Uploaded by

Maria Esther JimenezOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Brief: Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome

Brief: Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome

Uploaded by

Maria Esther JimenezCopyright:

Available Formats

Brief

in

Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome

Bernarda Viteri, MD,* Jeffrey M. Saland, MD†

*Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA

†

Mount Sinai Kravis Children’s Hospital, New York, NY

Thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) was described by Moschcowitz in 1924, and

the term hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) appeared by 1955 to describe a series

of patients with small-vessel renal thrombi, thrombocytopenia, and hemolytic

anemia. During the 1970s an association was noted between enteric Escherichia

coli infections and HUS, and in 1983 the specific trigger of Shiga toxin–producing

E coli (STEC) was recognized. This recognition led to classification of HUS as

“diarrhea positive” or “diarrhea negative,” although this terminology is no longer

popular. Other secondary forms of HUS are known, including HUS associated

with invasive pneumococcal infection, human immunodeficiency virus, systemic

AUTHOR DISCLOSURE Dr Viteri has disclosed lupus erythematosus, or uncommon reactions to medications such as cyclospor-

no financial relationships relevant to this ine. More recently, the term atypical HUS (aHUS) has been used to describe a

article. Dr Saland has disclosed that he is

rare form of HUS occurring in susceptible individuals, most often from defects in

principal investigator for a study related to

type 1 primary hyperoxaluria for Alnylam regulation of the alternative pathway of complement, whereas typical HUS largely

Pharmaceuticals. This commentary does not refers to STEC-HUS or pneumococcal HUS.

contain a discussion of an unapproved/ In patients with bloody diarrhea, it is imperative that front-line providers

investigative use of a commercial product/

device. understand the importance of testing for STEC. In many parts of the world STEC

O157:H7 is the most common pathogen leading to HUS, but it certainly is not the

Association Between Hydration Status, only one as many other organisms besides E coli have been causally implicated with

Intravenous Fluid Administration, and

Outcomes of Patients Infected with Shiga HUS. Testing for STEC is evolving quickly. Stool culture, various assays for the

Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli. Grisaru S, Shiga toxin, and most recently DNA testing of stool are all being used, each method

Xie J, Samuel S, et al. JAMA Pediatr. with its own strengths and limitations. The most crucial issue is timeliness because

2017;171(1):68–76

the window of opportunity to reduce the morbidity of HUS is limited.

Shiga-Toxin–Producing Escherichia coli and HUS is characterized by microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, with intravas-

Haemolytic Uraemic Syndrome. Tarr PI,

Gordon CA, Chandler WL. Lancet. cular red blood cell fragmentation seen as schistocytes on peripheral blood smear;

2005;365(9464):1073–1086 thrombocytopenia; and kidney injury manifesting as uremia. However, the pre-

Acute Bloody Diarrhea: A Medical

sentation of HUS can vary considerably, and any organ can be injured, including

Emergency for Patients of All Ages. the brain, pancreas, colon, and heart. And, in rare cases, the kidneys may be

Holtz LR, Neill MA, Tarr PI. Gastroenterology. spared. The differential diagnosis of HUS includes other forms of TMA, includ-

2009;136(6):1887–1898

ing thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), which clinically may be nearly

Complement Activation Is Associated with identical.

More Severe Course of Diarrhea-Associated

Whereas bloody diarrhea with STEC infection or a clearly evident infection

Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome: A Preliminary

Study. Karnisova L, Hradsky O, Blahova K, et al. with invasive pneumococcus quickly allows the diagnosis of typical HUS with

Eur J Pediatr. 2018;177(12):1837–1844 high certainty, when these infections are not present the etiology of HUS is

Hemorrhagic Colitis Associated with a Rare unclear without additional investigation. In such patients a presumption of aHUS

Escherichia coli Serotype. Riley LW, Remis RS, is useful because rapid empirical treatment may be curative. Initial diagnostic

Helgerson SD, et al. N Engl J Med. steps may include measuring ADAMSTS13 activity and assessing complement

1983;308(12):681–685

activity and markers of systemic lupus erythematosus. Decreased ADAMSTS13

Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome. Sethna CB, activity is not uncommon in aHUS, but activity less than 10% is generally

Gurusinghe S. In: Glomerulonephritis.

Trachtman H, Hogan J, Herlitz L, Lerma E, diagnostic of TTP instead. Low levels of C3 are suggestive but not necessary

eds. New York, NY: Springer; 2018 or sufficient to diagnose aHUS.

Vol. 41 No. 4 APRIL 2020 213

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ at Kardlinska Institute on April 4, 2020

STEC-HUS is among the leading causes of acute kidney evolve rapidly and require multiple blood transfusions; prac-

injury (AKI) in children younger than 3 years. HUS develops titioners should notify the blood bank of this possibility,

in approximately 15% of children younger than 10 years with which may allow several transfusions from the same unit of

STEC infection, mostly in the summer and autumn. STEC- blood, reducing exposure to several different blood donors.

HUS has a good prognosis in that most children recover Platelets are usually not given, except for active bleeding or if

from the episode, resolving AKI with few if any sequelae. a surgical procedure is required. Hypertension is frequent,

However, an important minority of patients has acutely seri- but its severity is variable and treatment may range from

ous or fatal renal and other target organ complications, minimal to aggressive, with the mandate being to maintain

such as gastrointestinal or neurologic events, and patients a safe blood pressure. Minor neurologic manifestations,

may, indeed, experience long-term complications, includ- such as irritability and headache, are common, but seizures

ing progressive chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal or altered mental status may herald severe complications

disease. such as ischemia from a large cerebrovascular accident,

Clinicians should have a high level of suspicion for HUS, diffuse microvascular disease, or hypertensive encephalop-

particularly in children younger than 10 years who develop athy. Any of these may result in permanent brain damage.

bloody diarrhea, often painful, with or without fever. The Severe AKI may require renal replacement therapy

diagnosis of STEC is of key importance because the risk of (RRT), usually peritoneal dialysis or hemodialysis; but in

developing HUS with STEC infection is reduced when the some cases, hemofiltration may be more suitable. Risk

microbiological diagnosis is made in a timely manner, factors at presentation associated with AKI requiring RRT

before the onset of HUS, and ample fluid replacement with include the degree of dehydration, oligoanuria, leukocytosis,

isotonic saline is provided. Even in patients in whom hematocrit concentration greater than 23%, and neurologic

administration of fluids during the period leading up to involvement. In turn, the requirement for RRT and its

HUS does not prevent its development, the severity of the duration (particularly >3 weeks) are associated with a higher

episode seems to be reduced by the early intervention with likelihood of long-term sequelae such as chronic kidney

saline fluid. One must be careful, however, to avoid fluid disease or end-stage renal disease.

overload and elevated blood pressure if AKI is unfolding. The diagnosis of aHUS begins with the same biochem-

Serial renal and hematologic evaluation, including blood cell ical and hematologic criteria as for typical HUS. Atypical

counts (especially hemoglobin, platelets, smear, and lactate features include age younger than 6 months, family history

dehydrogenase) is required, noting that serum measures of of HUS or recurrence of HUS, absence of diarrhea, or a

renal function lag behind actual renal function when it is in slower and insidious onset sometimes preceded by vague

flux. Hematologic manifestations often precede clear signs and nonspecific signs and symptoms.

of AKI. STEC-HUS usually develops within 1 week (5–13 aHUS is predominantly associated with defects of reg-

days) after the onset of diarrhea and commonly within 1 to ulatory proteins that allow increased activity of the alterna-

2 days of the diarrhea itself resolving. Thus, if the diarrhea tive pathway (AP) of complement. Implicated defects

with STEC infection resolves and the patient is stable for 1 to include those that reduce the activity of factor H, factor I,

3 days without hematologic or other manifestation, the risk and membrane cofactor protein, as well as defects that

of HUS may be considered past. increase factor B or C3 itself. Defects in thrombomodulin

Another imperative for identifying STEC, as opposed to and vitronectin have been implicated, as have antibodies

other causes of bloody diarrhea, is that the use of antibiotics against factor H, and the list of such defects may enlarge

with STEC may increase the likelihood of HUS; the current or shrink in the future as distinctions between causative

recommendation is to avoid antibiotics unless another mutations and common genetic variants are disentangled.

specific indication for their use supersedes. Nonetheless, However, the general mechanism of these various defects

some evidence suggests that the risk is not uniform across is shared: intrinsic and triggered activation of the AP

all classes of antibiotics; some (eg, fosfomycin) may actually pathway leads to unabated amplification, which results

reduce the risk of HUS. Future research is needed. in endothelial injury and TMA. An exception to this group

Most children with STEC-HUS require some degree of is HUS related to a mutation in the DGKE gene, which

symptomatic treatment, but no therapy is proven to ame- regulates an intracellular lipid kinase and is not related to

liorate typical HUS once it has developed. Anemia may complement.

214 Pediatrics in Review

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ at Kardlinska Institute on April 4, 2020

Measurement of AP function and genetic analysis has and treatment of the disease, I’d like to take the liberty of

improved considerably but still requires more time than recalling my Comment to that earlier article.

routine biochemical and hematologic testing. Thus, empir- Historically, HUS was considered the pediatric sibling of

ical treatment of aHUS is advised pending clarification TTP, a syndrome with similar clinical features but most

of the diagnosis. Eculizumab is a humanized monoclonal commonly affecting adults. However, it turns out that as

antibody that inhibits complement activation; approved in much as the 2 may look alike, their parentage is very different.

North America and Europe for aHUS, eculizumab super- Typical HUS, the classic form of the disease, is engendered

sedes the use of plasma therapy, which remains indi- by a toxin, whereas TTP is the product of an enzymatic

cated when eculizumab is not immediately available. For deficiency—the loss of ADAMTS-13, a metalloprotease that

patients with aHUS receiving long-term eculizumab ther- cleaves von Willebrand factor. TTP can be either familial,

apy, active efforts are underway to better classify and when the deficiency of ADAMTS-13 is inherited, or acquired,

monitor them to allow selective and safe discontinuation when autoantibodies attack the enzyme creating a functional

of treatment. deficiency. In the absence of customary cleavage, excessively

The role of complement in typical HUS remains large multimers of von Willebrand factor build up in the

ambiguous, with some evidence that Shiga toxin is able circulation, causing platelets to aggregate abnormally. The

to activate the AP. One study analyzed 33 patients with result is thrombosis, along with thrombocytopenia and its

STEC-HUS and found a correlation between C3 levels and characteristic purpuric rash: TTP. The thrombi in the micro-

disease severity. Eculizumab has been used in some vasculature cause the organ damage that is a feature of both

patients with severe typical HUS, although definitive evi- TTP and HUS, particularly to the kidneys and brain.

dence to support such use is lacking despite analysis of Of interest to pediatricians, although TTP is usually

its effect either in large STEC-HUS outbreaks or in reported considered a disease of adults, the first case described

case series. almost 100 years ago was the report of a 16-year-old patient.

COMMENT: We last published an In Brief on HUS in 2006. – Henry M. Adam, MD

Although we have since seen changes in our understanding Associate Editor, In Brief

ANSWER KEY FOR APRIL 2020 PEDIATRICS IN REVIEW

Headache in Children: 1. B; 2. B; 3. E; 4. B; 5. E.

Use of C-Reactive Protein and Ferritin Biomarkers in Daily Pediatric Practice: 1. E; 2. E; 3. D; 4. D; 5. B.

Where in the World Did You Get That Rash?: 1. E; 2. D; 3. B; 4. D; 5. B.

Vol. 41 No. 4 APRIL 2020 215

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ at Kardlinska Institute on April 4, 2020

Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome

Bernarda Viteri and Jeffrey M. Saland

Pediatrics in Review 2020;41;213

DOI: 10.1542/pir.2018-0346

Updated Information & including high resolution figures, can be found at:

Services http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/41/4/213

Subspecialty Collections This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

following collection(s):

Hematology/Oncology

http://classic.pedsinreview.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/hemato

logy:oncology_sub

Nephrology

http://classic.pedsinreview.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/nephro

logy_sub

Permissions & Licensing Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

in its entirety can be found online at:

https://shop.aap.org/licensing-permissions/

Reprints Information about ordering reprints can be found online:

http://classic.pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/reprints

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ at Kardlinska Institute on April 4, 2020

Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome

Bernarda Viteri and Jeffrey M. Saland

Pediatrics in Review 2020;41;213

DOI: 10.1542/pir.2018-0346

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

located on the World Wide Web at:

http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/41/4/213

Pediatrics in Review is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly

publication, it has been published continuously since 1979. Pediatrics in Review is owned,

published, and trademarked by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 345 Park Avenue, Itasca,

Illinois, 60143. Copyright © 2020 by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved.

Print ISSN: 0191-9601.

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ at Kardlinska Institute on April 4, 2020

You might also like

- Module 4 RLE Activity NeriDocument9 pagesModule 4 RLE Activity NeriAngela Neri75% (4)

- Hyperleukocytosis, Leukostasis and Leukapheresis Practice ManagementDocument6 pagesHyperleukocytosis, Leukostasis and Leukapheresis Practice ManagementPutri Wulan Sukmawati100% (1)

- Hyperviscosity SyndromeDocument34 pagesHyperviscosity SyndromeSartika Riyandhini100% (1)

- Jessica Reid-Adam: Department of Pediatrics, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NYDocument3 pagesJessica Reid-Adam: Department of Pediatrics, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NYAnastasia Widha SylvianiNo ratings yet

- Henoch-Schonlein PurpuraDocument5 pagesHenoch-Schonlein PurpuraPramita Pramana100% (1)

- Brief: Henoch-Schönlein PurpuraDocument5 pagesBrief: Henoch-Schönlein PurpuraAdrian KhomanNo ratings yet

- HEMOLYTICDocument4 pagesHEMOLYTICzainabd1964No ratings yet

- Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome A Case ReportDocument3 pagesHemolytic Uremic Syndrome A Case ReportAna-Mihaela BalanuțaNo ratings yet

- Pediatric VasculitisDocument17 pagesPediatric VasculitisRam PadronNo ratings yet

- By: DR Najibullah Suhraby FMR First YearDocument33 pagesBy: DR Najibullah Suhraby FMR First YearShami PokhrelNo ratings yet

- Acute GlomerulonephritisDocument4 pagesAcute GlomerulonephritisJulliza Joy PandiNo ratings yet

- Reid Adam2014Document5 pagesReid Adam2014afrilia.iNo ratings yet

- Hyperleukocytosis: Emergency Management: The Indian Journal of Pediatrics November 2012Document6 pagesHyperleukocytosis: Emergency Management: The Indian Journal of Pediatrics November 2012akshayajainaNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Sickle Cell Anemia 1Document11 pagesRunning Head: Sickle Cell Anemia 1api-264952333No ratings yet

- Colitis Isquemica PDFDocument7 pagesColitis Isquemica PDFWaldo ReyesNo ratings yet

- Vasculitis PDFDocument4 pagesVasculitis PDFDiego Ariel Alarcón SeguelNo ratings yet

- Management of HyperleukocytosisDocument10 pagesManagement of HyperleukocytosisNaty AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Universidad Privada San Juan Bautista: Escuela de Medicina HumanaDocument6 pagesUniversidad Privada San Juan Bautista: Escuela de Medicina HumanaKarolLeylaNo ratings yet

- Henoch Schonlein PurpuraDocument3 pagesHenoch Schonlein PurpuraannisaNo ratings yet

- How I Treat TTPDocument10 pagesHow I Treat TTPGhazal KangoNo ratings yet

- Osler-Weber-Rendu Disease - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocument4 pagesOsler-Weber-Rendu Disease - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfanaNo ratings yet

- Sickle Cell enDocument9 pagesSickle Cell enbatraz79No ratings yet

- Hemolytic UremicsyndromeDocument60 pagesHemolytic UremicsyndromeMuhammad AleemNo ratings yet

- Thrombotic Microangiopathy, Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome, and Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic PurpuraDocument16 pagesThrombotic Microangiopathy, Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome, and Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic PurpuraDavidAlbertoMedinaMedinaNo ratings yet

- Journal LeukemiaDocument5 pagesJournal LeukemiaSuwadiaya AdnyanaNo ratings yet

- Hemolytic-Uremic Syndrome in ChildrenDocument17 pagesHemolytic-Uremic Syndrome in ChildrenYuri vanessa Ortiz hNo ratings yet

- Hyperleukocytosis: Emergency ManagementDocument7 pagesHyperleukocytosis: Emergency Managementrivha ramadhantyNo ratings yet

- Application of Ultrasound Elastography in Assesing Portal HypertensionDocument16 pagesApplication of Ultrasound Elastography in Assesing Portal HypertensionValentina IorgaNo ratings yet

- How I Use Hydroxyurea To Treat Young Patients With Sickle Cell Anemia 2Document12 pagesHow I Use Hydroxyurea To Treat Young Patients With Sickle Cell Anemia 2qayyum consultantfpscNo ratings yet

- Sickle CellDocument16 pagesSickle CellAnastasiafynnNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology of Sepsis American Journal of PathologyDocument10 pagesPathophysiology of Sepsis American Journal of PathologyStella Gracia OctaricaNo ratings yet

- Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding in ChildrenDocument24 pagesLower Gastrointestinal Bleeding in ChildrenmacedovendezuNo ratings yet

- Anemia at Older AgeDocument10 pagesAnemia at Older AgeAbdullah ZuhairNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0006497120325088 MainDocument10 pages1 s2.0 S0006497120325088 MainDewi NurpitasariNo ratings yet

- Noncirrhotic Portal Hypertension: ReviewDocument6 pagesNoncirrhotic Portal Hypertension: ReviewIsrael BlancoNo ratings yet

- Summary of Summary 5Document36 pagesSummary of Summary 5anon-265120100% (2)

- Emergencias Hematologicas y OncologicasDocument17 pagesEmergencias Hematologicas y OncologicasFelipe Villarroel RomeroNo ratings yet

- Esophageal Varices: Pathophysiology, Approach, and Clinical DilemmasDocument2 pagesEsophageal Varices: Pathophysiology, Approach, and Clinical Dilemmaskaychi zNo ratings yet

- Sepsis - ClinicalKeyDocument41 pagesSepsis - ClinicalKeyRoberto AndíaNo ratings yet

- 2022 Hepatic EncephalopathyDocument22 pages2022 Hepatic Encephalopathykarina hernandezNo ratings yet

- Anemia en ReumatologiaDocument10 pagesAnemia en ReumatologiaAsunciónNo ratings yet

- Approach To A Child With Pallor and Hepatosplenomegaly: Anirban Das, MD, DMDocument7 pagesApproach To A Child With Pallor and Hepatosplenomegaly: Anirban Das, MD, DMMarc Lyndon CafinoNo ratings yet

- Glomerular Disease in ChildrenDocument8 pagesGlomerular Disease in ChildrenMuti IlmarifaNo ratings yet

- 11 - Shock - Current Diagnosis and Treatment Emergency MedicineDocument18 pages11 - Shock - Current Diagnosis and Treatment Emergency MedicineRon KNo ratings yet

- Portal HypertensionDocument13 pagesPortal HypertensionCiprian BoesanNo ratings yet

- Lo Wo Ho JMTDocument15 pagesLo Wo Ho JMTclaraNo ratings yet

- Approach To A Child With Pallor and Hepatosplenomegaly: Anirban DasDocument8 pagesApproach To A Child With Pallor and Hepatosplenomegaly: Anirban DasvgmanjunathNo ratings yet

- HemeoncalgorithmsDocument11 pagesHemeoncalgorithmsida ayu agung WijayantiNo ratings yet

- Vasculitis: Carol A. Langford, MD, MHS Bethesda, MDDocument11 pagesVasculitis: Carol A. Langford, MD, MHS Bethesda, MDYesid OlidenNo ratings yet

- VASCULITIS by Dr. AJ. 1Document34 pagesVASCULITIS by Dr. AJ. 1Abira KhanNo ratings yet

- What Is HenochDocument7 pagesWhat Is HenochHazel Monique SaysonNo ratings yet

- Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome: Ankit GurjarDocument18 pagesHemolytic Uremic Syndrome: Ankit GurjarAnkit Tonger AnkyNo ratings yet

- Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura and Hemolytic Uremic SyndromeDocument9 pagesThrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura and Hemolytic Uremic SyndromeRex RuthorNo ratings yet

- Myeloproliferative Disordersandthe Hyperviscosity Sy NdromeDocument18 pagesMyeloproliferative Disordersandthe Hyperviscosity Sy NdromeAhmad Harissul IbadNo ratings yet

- Hypertension in Hematologic Malignancies and Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation: An Emerging Issue With The Introduction of Novel TreatmentsDocument8 pagesHypertension in Hematologic Malignancies and Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation: An Emerging Issue With The Introduction of Novel TreatmentsGabryelNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Management of HELLP Syndrome Complicated by Liver HematomaDocument8 pagesDiagnosis and Management of HELLP Syndrome Complicated by Liver HematomaIce 69No ratings yet

- Sepsis and The Systemic Inflammatory Response SyndromeDocument22 pagesSepsis and The Systemic Inflammatory Response SyndromeLaburengkengNo ratings yet

- What Is Acute Glomerulonephritis?: Acute Glomerulonephritis (GN) Comprises A Specific Set of Renal Diseases inDocument6 pagesWhat Is Acute Glomerulonephritis?: Acute Glomerulonephritis (GN) Comprises A Specific Set of Renal Diseases inAnnapoorna SHNo ratings yet

- APSGNDocument3 pagesAPSGNmadimadi11No ratings yet

- SickleDocument6 pagesSickleNalini T GanesanNo ratings yet

- Comprehensive Insights into Acute Arterial Occlusion: Pathways, Prevention, and Holistic CareFrom EverandComprehensive Insights into Acute Arterial Occlusion: Pathways, Prevention, and Holistic CareNo ratings yet

- Spanish Flu ThesisDocument5 pagesSpanish Flu ThesisSomeoneToWriteMyPaperForMeCanada100% (2)

- Predictive Validity of The Post Partum Depression Predictors Inventory Revised PDFDocument6 pagesPredictive Validity of The Post Partum Depression Predictors Inventory Revised PDFAnonymous jmc9IzFNo ratings yet

- Upper Respiratory Tract InfectionDocument45 pagesUpper Respiratory Tract InfectionNatasha Abdulla100% (2)

- 2.02 - Quality and Bioequivalence Guideline - Jul19 - v7 1Document35 pages2.02 - Quality and Bioequivalence Guideline - Jul19 - v7 1vinayNo ratings yet

- Soal PTS 8 - INGGRISDocument10 pagesSoal PTS 8 - INGGRISeciNo ratings yet

- Nephrotic SyndromeDocument20 pagesNephrotic Syndromeami5687No ratings yet

- A 100-Year Journey From GV Black To Minimal Surgical InterventionDocument6 pagesA 100-Year Journey From GV Black To Minimal Surgical InterventionMichael XuNo ratings yet

- Active Management of The Third Stage of LabourDocument25 pagesActive Management of The Third Stage of LabourRedroses flowers0% (1)

- Mat2 FormDocument2 pagesMat2 FormTirso Leo Adelante100% (1)

- Hgfyjgf 7 IuDocument2 pagesHgfyjgf 7 IuPavan KumarNo ratings yet

- Drug StudyDocument2 pagesDrug StudyShayne Jessemae Almario100% (1)

- Rev Sistemática - Effectiveness of Medical Nutrition Therapy in Adolescents With TD1Document13 pagesRev Sistemática - Effectiveness of Medical Nutrition Therapy in Adolescents With TD1Nayesca GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Seven Countries Study A Scientific Adventure in C-Wageningen University and Research 287595Document220 pagesSeven Countries Study A Scientific Adventure in C-Wageningen University and Research 287595Jorge CabezasNo ratings yet

- Management of The Short Bowel Syndrome in Adults - UpToDateDocument10 pagesManagement of The Short Bowel Syndrome in Adults - UpToDateyessyNo ratings yet

- Clinical Teaching ON Geriatric AssessmentDocument9 pagesClinical Teaching ON Geriatric AssessmentANITTA SNo ratings yet

- Protocol and Thesis WritingDocument48 pagesProtocol and Thesis WritingPragya ShahNo ratings yet

- Ict in MedicineDocument9 pagesIct in MedicineObiegba V Fidelis50% (2)

- Module 1Document25 pagesModule 1AlbertDatu100% (1)

- CD003425Document14 pagesCD003425sarahloba100No ratings yet

- dwn150082F ns210 1602080177Document9 pagesdwn150082F ns210 1602080177Cindy ParamitaaNo ratings yet

- Megacolon Toxic of Idiophatic Origin: Case ReportDocument6 pagesMegacolon Toxic of Idiophatic Origin: Case ReportgayutNo ratings yet

- Povidone Iodine: Useful For More Than Preoperative AntisepsisDocument4 pagesPovidone Iodine: Useful For More Than Preoperative AntisepsisNur AjiNo ratings yet

- APPENDICITISDocument15 pagesAPPENDICITISTiffany AdriasNo ratings yet

- Effectivity of Vernonia Cinerea As An Anti-Microbial SalveDocument13 pagesEffectivity of Vernonia Cinerea As An Anti-Microbial SalveK8Y KattNo ratings yet

- Research & Development: Test Name Status Result Unit Reference Interval SARS-COV-2 Real-Time PCR, QualitativeDocument2 pagesResearch & Development: Test Name Status Result Unit Reference Interval SARS-COV-2 Real-Time PCR, QualitativeakashNo ratings yet

- Birthasphyxia 160328161503Document20 pagesBirthasphyxia 160328161503Noto SusantoNo ratings yet

- (6-22) DR Takele ManuscriptDocument17 pages(6-22) DR Takele Manuscriptchernet bekeleNo ratings yet

- Avarana in VyadhiDocument4 pagesAvarana in VyadhiSamhitha Ayurvedic ChennaiNo ratings yet

- Megan Reineck: EducationDocument3 pagesMegan Reineck: EducationMegan ReineckNo ratings yet