Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Burnout, Fatigue and Stress Factors in Solo Entrepreneurs

Burnout, Fatigue and Stress Factors in Solo Entrepreneurs

Uploaded by

PJ PoliranOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Burnout, Fatigue and Stress Factors in Solo Entrepreneurs

Burnout, Fatigue and Stress Factors in Solo Entrepreneurs

Uploaded by

PJ PoliranCopyright:

Available Formats

MBA

Thesis: Burnout, Stress, Fatigue + Solo Entrepreneurs 2015

BURNOUT,

FATIGUE

AND

STRESS

FACTORS

IN

SOLO

ENTREPRENEURS

A

Thesis

submitted

in

partial

satisfaction

of

the

requirements

of

the

Postgraduate

Degree

in

Master

of

Business

Administration

by

Suzanne

Jade

Barclay

June

2015

S. Jade Barclay -‐ 1 -‐ burnoutprofile.com

MBA Thesis: Burnout, Stress, Fatigue + Solo Entrepreneurs 2015

Executive

Summary

Burnout

can

be

devastating

to

individuals

and

organisations,

and

is

often

not

recognised

until

it

has

already

caused

physical,

mental

and

financial

damage

(Maslach

and

Lieter

1997;

Cordes

and

Dougherty

1993;

Maslach

and

Goldberg

1998;

Leiter

et

al.

2014).

Since

the

1970s,

the

majority

of

academic

research

into

burnout

has

studied

employees

who

work

closely

with

people

in

helping

professions,

such

as

nurses

or

teachers

(Ashkar

et

al.

2010;

Calnan

et

al.

2011;

Whitebird

et

al.

2013;

Maslach

1982).

As

more

and

more

people

have

the

opportunity

or

obligation

to

work

for

themselves

in

recent

years

(Arum

and

Müller

2004),

the

lack

of

entrepreneur-‐specific

research

in

the

literature

implies

that

employee

burnout

is

to

be

treated

the

same

as

solo

entrepreneur

burnout.

However,

personal

accounts

from

solo

entrepreneurs

and

mainstream

entrepreneurial

publications

imply

otherwise

(Robinson

2011;

Hughes

2011;

Seegal

2012;

Smbeco.com

2012).

The

purpose

of

this

research

project

is

to

investigate

the

unique

impact

and

experience

of

burnout

and

fatigue

on

solo

entrepreneurs,

with

a

view

to

identifying

common

themes

and

practical

prevention

and

management

strategies.

This

research

involved

conducting

surveys

and

non-‐directive

in-‐depth

interviews

with

respondents

about

their

experiences

with

burnout

and

fatigue

throughout

their

career,

both

as

a

solo

entrepreneur

and

as

an

employee.

The

literature

shows

that

employees

experience

three

dimensions

of

employee

burnout:

emotional

exhaustion,

depersonalisation,

and

diminished

sense

of

personal

accomplishment.

Unique

themes

emerged

in

this

study

showing

that

employees

and

solo

entrepreneurs

experience

their

work

differently

and,

as

such,

experience

burnout

very

differently.

This

studied

revealed

that

solo

entrepreneurs

experience

three

very

different

types

of

burnout:

physical

breakdown

(body),

mental

exhaustion

(brain),

and

lack

of

challenge

(boredom).

Once

one

is

aware

of

these

types

of

burnout,

prevention

and

early

intervention

is

possible

as

each

type

can

each

be

recognised

and

managed

appropriately.

S. Jade Barclay -‐ 2 -‐ burnoutprofile.com

MBA Thesis: Burnout, Stress, Fatigue + Solo Entrepreneurs 2015

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS: ENTREPRENEUR BURNOUT PROFILE

Research

reveals 3 distinct types of Entrepreneurial Burnout.

Symptoms differ from burnout experienced by employees. • Take regular

Research findings and helpful practices are outlined below. vacations

Business

ceases to be interesting after

• Automate + delegate

the

challenge of establishing and

growing it is behind you.

• Start a new project

But you still have energy, clear thinking

or a new business

and interest in other areas of life.

BOREDOM

Awareness

is

the

first

step.

(Many

entrepreneurs

12.5%

For all 3 types, ignoring or

have both Brain and fighting it makes it worse.

Body symptoms

simultaneously.) BODY

62.5% Decision-‐making is difficult.

BRAIN Can’t think as clearly as usual.

“My body just broke down.” Brain is foggy, thinking is fuzzy.

79.2%

Can’t eat, sleep, concentrate. . Mental exertion = physical fatigue.

Increased sensitivity to stress, Lack of sleep can ruin the next day

noise, foods, chemicals. Less work or two. Flexible schedule becomes

and more support required asap. a necessity, not a luxury.

TOP BURNOUT PREVENTION PRACTICES FOR SOLO ENTREPRENEURS:

CLEAR YOUR MIND + GET RESTORATIVE MANAGE TASKS BY ENERGY,

❶ STEP AWAY FROM YOUR WORK

❷ NOT BY URGENCY

Entrepreneurs are “always on” and their minds Batching tasks or time-‐boxing is even more

don’t leave work at 5pm. Build in deliberate helpful when aligned with your natural cycle of

ways to “flush the brain” and truly switch off high + low energy times during the day or week.

twice a day and at the end of each week.

Entrepreneurs constantly make decisions and

Allow breathing room in your schedule. think new thoughts, leading to fatigue. But they

Don’t wait until you get to breaking point. also have more control over their schedules.

Be preventative. Schedule it in advance.

Deliberately step away every day. • Well-‐rested, within 3-‐4 hours of waking:

Decisions + Creativity + Difficult Analysis

• Take a walk in nature Make decisions first, in your best hour

10 minutes at the park or beach

• Mid-‐range energy and clarity hours:

• Talk it out, use your social support Concentration + Learning + Writing

10-‐minute talk vs 48-‐hour crash • Low energy and foggy hours:

Restorative + Repetitive + Familiar

• Relax in, on or near the water

Email + Admin + Mindless filing

Lakes, rivers, beaches, showers, baths

• Reduce task-‐switching:

• Out of your head + into your body Batch all the same tasks together

Yoga, massage, swim, cuppa tea Creative day, Meetings day, Admin day

S. Jade Barclay -‐ 3 -‐ burnoutprofile.com

MBA Thesis: Burnout, Stress, Fatigue + Solo Entrepreneurs 2015

Table of Contents

1. Introduction...............................................................................................6

2. Orientation ................................................................................................8

2.1. Entrepreneurship defined .............................................................8

2.2. Burnout defined...........................................................................10

2.3. Why solo entrepreneurs..............................................................13

2.4. Research questions......................................................................13

3. Data collection and analysis ....................................................................14

3.1. Stage one – reconnaissance ........................................................15

3.2. Stage two – online surveys ..........................................................15

3.3. Stage three – in-‐depth interviews ...............................................16

3.3.1. Three types of burnout....................................................17

3.3.2. Sleep and being “always on” ...........................................18

3.3.3. Time and control..............................................................19

3.3.4. Stress and pressure..........................................................21

3.3.5. Support and isolation.......................................................21

3.3.6. Introverts and extraverts .................................................22

4. Key findings..............................................................................................23

5. Key implications.......................................................................................25

6. Conclusion ...............................................................................................27

References...................................................................................................28

Appendices ..................................................................................................33

Appendix 1: AIB Individual consent form ...........................................34

Appendix 2: Online survey questions and results...............................35

Appendix 3: Interview themes............................................................40

Appendix 4: Entrepreneur Burnout Profile (EBP) ...............................41

S. Jade Barclay -‐ 4 -‐ burnoutprofile.com

MBA Thesis: Burnout, Stress, Fatigue + Solo Entrepreneurs 2015

1. Introduction

Burnout

and

fatigue

affect

not

just

work

performance,

but

can

lead

to

long-‐term

health,

relational

and

financial

problems

(Maslach

and

Lieter

1997;

Leiter

and

Maslach

2005;

Leiter

et

al.

2014).

This

research

focuses

on

exploring

burnout,

fatigue

and

stress

factors

as

experienced

by

solo

entrepreneurs,

and

draws

on

academic

literature

about

burnout

in

the

workplace

and

a

mainstream

texts

that

target

the

entrepreneurship

market.

The

purpose

of

this

research

is

to

gain

insights

into

the

factors

that

surround

burnout

and

fatigue

in

solo

entrepreneurs,

and

to

make

recommendations

for

practice,

and

identify

common

themes

and

practical

measures

that

can

be

used

to

prevent

and

reverse

burnout.

Burnout

research,

pioneered

by

Christine

Maslach

PhD

in

the

1970s,

focuses

on

exploring

how

working

closely

with

people

can

lead

to

burnout

(Maslach

and

Lieter

1997;

Maslach

and

Goldberg

1998;

Maslach

1982).

Research

has

typically

been

conducted

in

employee

populations

with

employees

who

work

closely

with

people,

such

as

nurses,

educators,

and

psychotherapists

(Ashkar

et

al.

2010;

Calnan

et

al.

2011;

Whitebird

et

al.

2013;

Cordes

and

Dougherty

1993;

Maslach

1982).

Burnout

and

compassion

fatigue

research

has

been

crucial

in

establishing

supportive

procedures

and

policies

in

the

workplace

to

enable

sustainable

health

and

performance

outcomes

for

employees

(ibid.).

As

more

people

turn

to

solo

entrepreneurship

as

a

viable

work

option,

there

seems

to

be

an

unspoken

assumption

in

the

field

that

burnout

findings

for

employees

hold

equally

true

for

entrepreneurs.

While

it

is

well

recognised

than

stress

and

burnout

are

inevitable

by-‐products

of

entrepreneurship,

almost

no

literature

is

available

in

this

area,

which

has

been

largely

ignored

by

scholars

and

researchers

(Shepherd

et

al.

2010).

In

recent

years

there

has

been

frequent

coverage

of

entrepreneurial

burnout

and

entrepreneurial

mental

health

in

mainstream

publications

(Carson

2015;

Ellsberg

2014;

S. Jade Barclay -‐ 5 -‐ burnoutprofile.com

MBA Thesis: Burnout, Stress, Fatigue + Solo Entrepreneurs 2015

Ferriss

2008;

Hoehn

2014;

Bruder

2014)

An

assumption

has

been

repeatedly

stated

that

isolation

and

overload

are

common

problems

for

entrepreneurs

(Sydney

Morning

Herald

2011;

Smbeco.com

2012;

Kraft

2006;

Robinson

2011;

Gray

2015).

Despite

this,

a

gap

has

been

identified

in

the

academic

literature

relating

to

stress

and

burnout

in

entrepreneurs

and

in

people

who

work

alone

(Shepherd

et

al

2010;

Grant

and

Ferris

2009).

In

particular,

this

research

project

explores

burnout

among

solo

entrepreneurs

and

identifies

practical

intervention

and

prevention

factors

that

could

increase

productivity

and

health

for

solo

entrepreneurs.

Surveys

and

in-‐depth

phenomenological

interviews

were

conducted

with

solo

entrepreneurs

about

their

experiences

with

burnout

and

fatigue

throughout

their

career,

both

as

a

solo

entrepreneur

and

as

an

employee.

These

interviews

were

exploratory

and

non-‐directive,

allowing

core

themes

to

emerge

from

the

respondents’

own

words

without

introducing

any

typical

burnout-‐related

jargon

or

predictive

categorisation.

Employees

and

solo

entrepreneurs

experience

their

work

differently

and

experience

burnout

differently.

As

entrepreneurs,

the

majority

of

respondents

described

“never

switching

off”

and

no

longer

being

able

to

stop

thinking

about

work

after

5pm

like

they

could

as

employees.

For

some,

this

affected

their

sleep,

or

their

relationships.

Counter-‐

intuitively,

most

respondents

felt

more

isolated

when

surrounded

by

people

in

their

former

jobs

than

they

did

working

for

themselves,

and

chose

to

go

solo

to

gain

a

greater

sense

of

control

over

their

time

and

meaning

in

their

work.

Rather

than

the

lack

of

control

experienced

by

burnt

out

employees,

solo

entrepreneurs

described

having

full

control

over

what

they

do

and

how

and

when

they

do

it.

As

such,

rather

than

the

three

burnout

dimensions

as

measured

by

Maslach’s

Burnout

Inventory

–

exhaustion,

cynicism,

and

professional

efficacy

–

which

has

been

validated

for

numerous

employee

occupations

(Maslach

1981;

Maslach

and

Jackson

1981;

Langballe

et

al.

2006),

solo

entrepreneurs

experience

three

very

different

versions

of

burnout:

physical

body

breakdown,

mental

exhaustion,

and

lack

of

challenge,

each

of

which

can

be

specifically

recognised

and

managed.

S. Jade Barclay -‐ 6 -‐ burnoutprofile.com

MBA Thesis: Burnout, Stress, Fatigue + Solo Entrepreneurs 2015

Five

sections

follow

in

this

report.

Firstly,

a

brief

review

of

existing

literature,

then

data

collection

and

analysis.

The

key

findings

are

extracted

in

the

third

section,

followed

by

key

implications

for

solo

entrepreneurs,

recommendations

for

practice,

and

suggestions

for

future

research.

2. Orientation

A

recent

study

revealed

a

seven

times

higher

rate

of

mental

health

issues

to

entrepreneurs

(49%)

than

the

general

population

(7%)

(Carson

2015).

The

same

study

showed

that

72%

of

entrepreneurs

reported

having

mental

health

problems

in

themselves

or

their

immediate

family

(ibid.).

Stress,

burnout

and

mental

health

issues

are

intertwined

for

entrepreneurs,

despite

being

largely

understudied

topics

in

this

population

(Shepherd

et

al.

2010).

Entrepreneurs

engage

with

work

differently

than

their

employee

counterparts.

Despite

frequent

references

in

mainstream

press

to

stress

and

mental

health

risks

associated

with

burnout

in

the

life

of

an

entrepreneur,

there

has

been

very

little

academic

research

to

support

this

claim

(Carson

2015;

Ellsberg

2014;

Hoehn

2014;

Bruder

2014;

Seegal

2012;

Robinson

2011;

Hughes

2011;

Ferriss

2008).

Academic

burnout

research

conducted

on

employee

populations,

adopted

by

authors

in

mainstream

media,

has

been

assumed

to

be

applicable

to

the

entrepreneurial

experience.

However,

usual

measures

of

occupational

stress

and

job

burnout

do

not

effectively

translate

to

entrepreneurs

(Shepherd

et

al.

2010;

Grant

and

Ferris

2009).

This

research

takes

a

look

behind

these

unspoken

assumptions.

2.1. Entrepreneurship defined

It

is

generally

accepted

that

there

is

not

one

single

definition

that

encapsulates

entrepreneurship

(Kuratko,

2014;

Spinelli

and

Adams

2012).

The

word

originated

from

the

French

entrependre

meaning

“to

undertake”

and

has

also

been

described

as

“a

S. Jade Barclay -‐ 7 -‐ burnoutprofile.com

MBA Thesis: Burnout, Stress, Fatigue + Solo Entrepreneurs 2015

journey

of

promise”

(Kuratko

2014;

Hamilton

2009).

The

literature

includes

three

characteristics

that

separate

an

entrepreneur

from

a

small

business

owner.

A

small

business

is

generally

viewed

as

a

going

concern

that

is

managed

without

much

focus

on

change

or

growth.

An

entrepreneurial

venture,

in

contrast,

involves

pursuing

rapid

yet

sustainable

growth,

immediate

profits,

and

accepting

responsibility

for

a

certain

level

of

risk

(Kuratko

2014;

Spinelli

and

Adams

2012).

While

entrepreneurs

may

acquire

funding

and

assemble

a

team

to

enable

the

growth

they

seek,

it

is

the

pursuit

of

growth

and

assumption

of

risk

that

defines

entrepreneurship,

not

the

means

by

which

that

growth

is

attained.

The

literature

reflects

an

assumption

that

entrepreneurship

is

driven

by

combining

opportunity

and

individual

skills

(Kuratko

2014;

Shane

2003).

However,

solo

entrepreneurs

describe

a

necessary

dimension

of

having

control

over

one’s

schedule

and

meaningfulness

in

one’s

work,

which

aligns

more

with

Daniel

Pink’s

(2009)

inner

motivational

model

of

autonomy,

mastery

and

purpose.

Entrepreneurs

typically

gain

experience

as

employees

before

beginning

their

own

ventures.

Solo

entrepreneurship

has

become

mentioned

more

and

more

in

mainstream

literature

and

a

little

in

academic

literature.

A

solo

entrepreneur

is

defined

as

an

entrepreneur

with

no

employees

(Wasdani

and

Mathew

2014).

Solo

entrepreneurs

include

freelancers

selling

their

own

services,

owners

of

agencies

of

contractors,

or

individuals

who

grow

their

business

by

expanding

their

product

line

and

distribution

channels.

Solo

entrepreneurs

may

use

investment

capital

to

start

or

grow

their

venture,

assume

risk,

and

focus

on

growth

and

profit,

while

deliberately

not

taking

on

employees

(ibid.).

Of

the

1.8

million

small

businesses

in

Australia,

and

most

of

them

are

home-‐based

(Switzer

2007).

48.6%

of

all

firms

in

Australia

and

22

million

firms

in

the

USA

are

reported

to

be

solo

entrepreneurs

or

“non-‐employer

businesses”,

with

combined

receipts

of

over

$950

billion

in

the

American

businesses

alone

(Baron

and

Shane

2007,

Nagel

2013).

Even

as

employees,

it

is

estimated

that

over

30%

of

employees

have

tried

S. Jade Barclay -‐ 8 -‐ burnoutprofile.com

MBA Thesis: Burnout, Stress, Fatigue + Solo Entrepreneurs 2015

to

tap

into

Australia’s

$51

billion

freelancing

economy,

without

being

aware

of

the

potential

health

risks

(Chung

2014).

Solo

entrepreneurs

and

micro-‐businesses

make

a

significant

contribution

to

the

economy,

and

are

seven

times

affected

more

by

mental

health

issues,

stress

and

burnout

than

traditional

employees

(Carson

2015).

2.2. Burnout defined

Leiter

et

al.

(2014)

define

the

psychological

concept

of

burnout

as

long-‐term

exhaustion

and

diminished

interest

in

work.

Employee

burnout,

referred

to

as

job

burnout

or

compassion

fatigue,

was

first

identified

in

the

1970s

and

since

then

has

been

studied

extensively

(ibid.).

Job

burnout

has

been

persistent

over

time,

and

has

been

found

to

be

a

widespread

phenomenon

around

the

world

(ibid.).

The

literature

has

defined

three

typical

elements

to

employee

burnout:

emotional

exhaustion,

depersonalisation

or

cynicism,

and

a

diminished

sense

of

personal

efficacy

and

accomplishment

(Cordes

and

Dougherty

1993;

Maslach

1981;

Maslach

1982).

Initial

burnout

research

focused

on

proving

that

the

phenomenon

exists,

and

standardising

its

measurement

in

an

occupational

context

(Maslach

1982).

The

social

context

of

job

burnout

focused

on

the

emotional

exhaustion

experienced

by

those

in

occupations

that

involved

both

frequent

and

intense

social

interactions,

such

as

nurses,

medical

students,

teachers

and

psychotherapists

(Maslach

1982;

Maslach

and

Leiter

2010;

Whitebird

et

al.

2013;

Montgomery

2014).

Also,

the

level

of

meaningfulness,

uncertainty

and

role

ambiguity

surrounding

one’s

work

has

been

found

to

also

be

contributing

factors

to

burnout

(ibid.).

Later

literature

focused

on

the

degree

to

which

organisations

are

responsible

for

the

health

and

risk

of

burnout

to

their

staff

(Montgomery

2014;

Whitebird

et

al.

2013;

Calnan

et

al.

2001;

Maslack

and

Goldberg

1998;

Maslach

and

Leiter

2010).

S. Jade Barclay -‐ 9 -‐ burnoutprofile.com

MBA Thesis: Burnout, Stress, Fatigue + Solo Entrepreneurs 2015

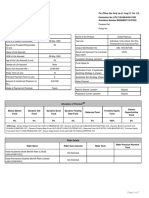

Figure 1. Social Interactions and Job Burnout

Frequency

of

Social

Interactions

Low

High

FREQUENT

FREQUENT

(NOT

INTENSE)

&

INTENSE

Moderate

burnout

risk

High

burnout

risk

(NOT

FREQUENT)

INTENSE

(NOT

INTENSE)

(NOT

FREQUENT)

Low

burnout

risk

Moderate

burnout

risk

Low

High

Intensity

of

Social

Interactions

Source:

Created

for

this

research

Burnout,

among

stress

and

other

mental

challenges

that

face

entrepreneurs,

has

been

discussed

more

and

more

frequently

in

mainstream

media

in

recent

years

(Carson

2015;

Ellsberg

2014;

Hoehn

2014;

Hughes

2011;

Ferriss

2008).

When

a

psychological

topic

becomes

popular

in

entrepreneurial

publications

in

mainstream

media,

usually

a

new

piece

of

academic

research

or

a

new

book

on

the

subject

is

cited

in

one

or

more

of

the

popular

articles,

as

was

the

case

with

the

growing

interest

in

neuroplasticity

since

2009

(Doidge

2009;

Doidge

2015).

However,

the

entrepreneurial

burnout

phenomenon,

while

frequently

discussed,

cannot

be

traced

back

to

a

new

book

or

academic

research

to

spark

its

recent

popularity.

The

topic

seems

to

have

become

popular

because

authors

and

entrepreneurs

have

been

writing

about

personal

experiences

rather

research.

The

little

academic

research

found

that

specifically

addresses

burnout

in

entrepreneurs

shows

that

the

measures

used

for

employees

are

inadequate

when

applied

to

entrepreneurs

(Shepherd

et

al.

2010;

Grant

and

Ferris

2009).

The

most

common

instrument

used

to

assess

burnout

is

the

Maslach

Burnout

Inventory

and

its

variants

(Maslach

and

Jackson

1981;

Schaufeli

et

al.

1996).

These

instruments

have

been

used

in

academic

research

primarily

with

employee

populations.

While

these

S. Jade Barclay -‐ 10 -‐ burnoutprofile.com

MBA Thesis: Burnout, Stress, Fatigue + Solo Entrepreneurs 2015

instruments

have

been

adapted

for

various

occupational

groups

and

students,

no

instruments

have

been

found

that

are

specifically

designed

for

use

with

entrepreneur

populations.

Of

six

general

areas

evaluated

in

the

most

common

employee

burnout

assessment,

only

one

directly

applies

to

the

solo

entrepreneur.

The

first

area,

Workload

(See

Figure

2

below),

is

the

only

area

that

is

directly

applicable

to

the

solo

entrepreneur’s

experience.

The

other

five

areas

are

not

relevant

because

the

entrepreneur

has

control

over

their

own

work

environment

and

working

conditions.

Issues

such

as

role

ambiguity,

role

conflict,

role

overload,

communicating

vision,

delegation,

maintaining

drive

and

reputation,

unforeseen

risks,

fear

of

failure,

and

other

entrepreneur-‐specific

antecedents

of

stress

and

burnout

are

not

accounted

for

in

employee

burnout

assessments

(Maslach

and

Jackson

1981;

Shepherd

et

al.

2010;

Grant

and

Ferris

2009).

Figure

2:

Quick

Burnout

Assessment

Source:

Maslach

and

Leiter

2010,

p.48

S. Jade Barclay -‐ 11 -‐ burnoutprofile.com

MBA Thesis: Burnout, Stress, Fatigue + Solo Entrepreneurs 2015

2.3. Why solo entrepreneurs

This

research

investigates

entrepreneurs

in

general,

and

solo

entrepreneurs

in

particular,

exploring

aspects

of

the

experience

of

burnout.

This

approach

provides

new

insights

for

three

important

reasons.

Firstly,

burnout

research

has

traditionally

focused

on

employees,

not

entrepreneurs.

Solo

entrepreneurs

are

uniquely

positioned

to

describe

the

similarities

and

differences

between

being

an

employee

and

being

an

entrepreneur

because

most

have

held

both

roles

in

quick

succession.

Secondly,

burnout

research

has

traditionally

focused

on

people

who

work

closely

with

people,

not

people

who

work

primarily

alone.

Solo

entrepreneurs

may

hire

contractors

and

engage

with

clients,

but

they

generally

work

alone

in

their

business,

control

their

own

schedule,

and

shoulder

the

full

risk

and

responsibility

for

every

decision

in

their

venture

without

partners

or

colleagues.

This

is

a

very

different

experience

of

work

and

may

lead

to

a

very

different

experience

of

burnout.

Finally,

even

within

the

context

of

social

psychology,

typical

burnout

research

has

been

quantitative,

investigating

prevalence

statistics

and

proving

pre-‐existing

hypotheses,

whereas

this

research

is

qualitative,

taking

a

phenomenological

approach

to

explore

the

lived

experience

of

burnout

and

any

common

themes

that

may

organically

emerge.

2.4. Research

questions

The

purpose

of

this

project

is

to

explore

the

phenomenological

experience

and

coping

strategies

of

solo

entrepreneurs

related

to

stress,

fatigue

and

burnout,

and

make

recommendations

for

practice.

The

following

questions

will

be

addressed:

• How

do

solo

entrepreneurs

experience

stress,

fatigue

and

burnout?

• What

are

the

most

stressful

pressures

for

solo

entrepreneurs?

S. Jade Barclay -‐ 12 -‐ burnoutprofile.com

MBA Thesis: Burnout, Stress, Fatigue + Solo Entrepreneurs 2015

• How

do

solo

entrepreneurs

cope

with

stress,

fatigue,

burnout

and

isolation?

• What

are

the

similarities

and

differences

in

stress,

burnout

and

fatigue

levels

compared

with

previous

work

experience

(before

becoming

a

solo

entrepreneur)?

• What

strategies

do

solo

entrepreneurs

utilise

to

prevent

or

reverse

elevated

stress

and

burnout?

• What,

if

any,

systemic

themes

are

present

in

the

profiles

of

solo

entrepreneurs?

This

research

aims

to

contribute

to

a

significant

issue

that

affects

many

entrepreneurs

by

opening

the

door

for

further

academic

research

for

burnout

and

mental

health

for

this

largely

understudied

population.

Benefits

to

solo

entrepreneurs

include

providing

recommendations

for

burnout

prevention

and

reversal

in

daily

practice.

3. Data Collection and Analysis

The research methodology is a qualitative case study focusing on solo entrepreneurs

(Saunders et al. 2012; Yin 2013). Surveys and in-‐depth phenomenological interviews

were conducted with 24 solo entrepreneurs about their experiences with burnout and

fatigue throughout their career, both as a solo entrepreneur and in their previous roles

as either a partnered business owner, consultant, student or employee. An exploratory

and non-‐directive interview approach was deliberately adopted, allowing core themes to

emerge from the respondents’ own words and personal understanding, without

introducing any jargon, interpretation, or arbitrary categorisation.

Secondary data and primary data were collected and analysed as part of this research.

Respondents were sourced via six online networking groups for entrepreneurs. Each

respondent was directed to complete an online survey and informed consent form prior

to their interview (see Appendix 1 and Appendix 2). The completed surveys and

interviews were coded and emergent themes were identified and analysed. Cross-‐

referencing between the surveys, the interview data and the literature also provided

additional insights.

S. Jade Barclay -‐ 13 -‐ burnoutprofile.com

MBA Thesis: Burnout, Stress, Fatigue + Solo Entrepreneurs 2015

3.1. Stage one – reconnaissance

Initial

research

was

conducted

with

secondary

data,

exploring

burnout

in

academic

literature

and

mainstream

publications.

These

findings

are

shared

in

section

2

above.

Burnout

research

has

primarily

been

conducted

on

employee

populations,

with

no

mention

of

entrepreneurs.

Additionally,

the

majority

of

the

burnout

research

concentrated

on

nursing,

medical,

teaching,

and

psychotherapy

staff

(Maslach

1982;

Montgomery

2014).

The

entrepreneurial

experience

was

not

discussed

in

any

of

the

literature

that

was

reviewed.

Common

assessment

instruments

used

in

research

into

burnout

and

fatigue

were

reviewed.

3.2. Stage two – online surveys

Primary

data

was

collected

via

online

surveys.

24

respondents

completed

a

short

online

survey

(see

Appendix

2).

The

researcher

assumed

respondents

could

be

busy

and

have

short

attention

spans.

To

ensure

the

most

completed

responses,

this

survey

was

designed

to

be

simple,

quick

and

enjoyable

to

complete

online

(Typeform.com

2015).

The

questions

were

designed

to

apply

specifically

to

solo

entrepreneurs

while

also

incorporating

elements

from

commonly

used

fatigue

and

burnout

instruments,

including

the

Maslach

Burnout

Inventory

(Maslach

and

Jackson

1981)

and

the

Fatigue

Severity

Scale

(Krupp

1989;

Neuberger

2003).

Data analysis of this stage

Respondents

worked

in

various

industries,

including

technology,

coaching,

healing,

sales,

finance,

and

translation

services.

Despite

vastly

different

industries

and

work

activities,

the

described

experience

of

entrepreneurship

and

burnout

was

remarkably

similar.

The

number

of

years

working

as

a

solo

entrepreneur

varied

from

a

few

months

to

over

30

years,

with

an

average

of

9.3

years.

Only

one

of

24

respondents

reported

feeling

no

sense

of

meaning

or

contribution

in

his

or

her

work.

There

were

slightly

more

female

(54.1%)

than

males

(45.9%)

respondents.

S. Jade Barclay -‐ 14 -‐ burnoutprofile.com

MBA Thesis: Burnout, Stress, Fatigue + Solo Entrepreneurs 2015

Despite

100%

stating

that

they

were

good

at

their

work,

over

half

the

respondents

(54.1%)

stated

that

they

missed

deadlines

a

few

times

per

month

or

more,

and

most

(87.5%)

found

that

stress

and

fatigue

stopped

them

from

thinking

clearly

or

completing

work

as

quickly

as

they

would

like.

Most

of

respondents

(62.5%)

reported

that

stress

and

fatigue

prevented

them

from

starting

as

many

projects

as

they

would

like.

Every

respondent

bar

one

(95.8%)

stated

that

stress

and

fatigue:

• impaired

thinking

speed;

or

• reduced

capacity

to

take

on

new

projects;

• or

both.

As

a

solo

entrepreneur

is

only

as

productive

as

his

or

her

ability

to

start

new

projects,

think

clearly,

and

complete

projects

quickly,

this

finding

may

have

far-‐reaching

performance

implications.

3.3. Stage three – in-‐depth interviews

All

interviews

were

conducted

via

phone

or

Skype.

Each

interview

was

between

60-‐75

minutes

in

duration.

24

completed

the

online

survey,

but

only

21

completed

interviews.

One

respondent

was

hospitalised,

and

two

mixed

up

the

times

and

did

not

reschedule.

Each

respondent

was

briefed

about

confidentiality

and

privacy,

and

permission

was

sought

to

record

the

audio

of

the

interview.

One

respondent

refused

permission

to

record

and

requested

only

hand

written

notes

be

taken.

To

minimise

researcher

bias,

while

maintaining

an

unstructured

and

in-‐depth

approach,

leading

questions

were

avoided

(Yin

2013).

The

initial

question

for

each

interview

was

“Tell

me

your

story

of

becoming

a

solo

entrepreneur,

and

your

story

of

burnout

or

fatigue,

if

you

have

one.”

From

there,

if

any

pertinent

themes

were

mentioned,

following

questions

took

the

form

of

“I’m

curious,

you

mentioned

{theme}.

Would

you

tell

me

more

about

that?”

S. Jade Barclay -‐ 15 -‐ burnoutprofile.com

MBA Thesis: Burnout, Stress, Fatigue + Solo Entrepreneurs 2015

Data analysis of this stage

Interviews

revealed

three

different

types

of

burnout

symptoms,

each

of

which

is

different

from

the

typical

employee

burnout

dimensions.

The

most

common

and

significant

themes

that

emerged

during

the

interviews

include:

• Three

types

of

burnout

• Sleep

and

being

“always

on”

• Time

and

control

• Stress

and

pressure

• Support

and

isolation

• Introverts

and

extraverts

3.3.1. Three types of burnout

Respondents

described

three

distinct

types

of

burnout:

(i)

the

body

just

broke

down,

with

physical

symptoms,

often

affecting

the

immune

and

digestive

systems;

(ii)

mental

fatigue,

with

fuzzy

thinking,

exhaustion,

forgetfulness

and

poor

concentration;

and

(iii)

lack

of

challenge,

with

disinterest

in

the

business

once

it

was

financially

stable.

Some

respondents

reported

having

one

major

burnout

experience,

while

many

had

one

initial

burnout

experience

and

many

subsequent

mini-‐crashes.

For

many,

despite

serious

improvements

they

have

not

ever

felt

as

strong

or

had

the

same

level

of

energy

since

that

first

crash.

For

many

with

physical

symptoms,

there

was

also

a

relational

issue

or

relational

trauma

also

described.

“I

tried

to

work

and

I

could

only

last

an

hour.

I

couldn’t

even

sit

at

a

desk.”

“My

brain

was

fuzzy

and

I

couldn’t

produce.

I

couldn’t

eat,

couldn’t

sleep,

couldn’t

concentrate.”

“It

was

really

disheartening.

And

scary.

I’m

used

to

being

capable

and

competent,

and

all

of

a

sudden

I

wasn’t.”

S. Jade Barclay -‐ 16 -‐ burnoutprofile.com

MBA Thesis: Burnout, Stress, Fatigue + Solo Entrepreneurs 2015

“Burnout is something you tend to recognise in

hindsight.”

“My body just broke down. It was devastating, but I

couldn’t do anything about it.”

3.3.2. Sleep and being “always on”

Many respondents reported having trouble with sleep, and that their minds were

“always on” and they “couldn’t switch off.” Respondents gave various reasons for this,

from childhood trauma to head injury to having lots of ideas racing around the mind.

Sleep troubles were separated into three distinct types: (i) Trouble getting to sleep

easily; (ii) Needing more rest no matter how long they slept; and (iii) Getting to sleep

easily, but waking up for a couple of hours around midnight.

Those who couldn’t get to sleep easily either cited a childhood trauma that had taken

place at night, or described their mind racing with thoughts – usually about their

business – and that they found it hard to quiet the mind and drift off. Most used several

sleep strategies and could to get to sleep within an hour. Those who felt they needed

more and more rest identified as experiencing burnout currently, or being in recovery.

They were very protective of their sleep hygiene and had 7-‐9 hours sleep every night as

often as possible.

The group who got to sleep easily but woke in the night all described almost the exact

same experience, but different interpretations of that experience. They described falling

asleep then waking for two hours, then going to sleep again only to feel refreshed upon

waking around sunrise. The interpretations were either: (a) lying in bed trying to go back

to sleep for the full two hours, getting more and more frustrated and worried; or (b)

getting up, making a tea, meditating or writing for the two hours, then going back to

sleep. All mentioned the broken sleep to their doctors and spouses, and their doctors

had told them it was a problem. None of the respondents had heard of segmented

S. Jade Barclay -‐ 17 -‐ burnoutprofile.com

MBA Thesis: Burnout, Stress, Fatigue + Solo Entrepreneurs 2015

sleep,

even

though

they

were

regularly

experiencing

it.

Sleep

historians

have

found

that

“first

sleep,

second

sleep”

was

common

knowledge

in

the

times

before

the

invention

of

the

electric

light

bulb

(Ekirch

2005).

Researchers

claim

that

this

broken

sleep

is

a

golden

time

for

creativity

(Emslie

2014)

and

that

the

prolactin

boost

provides

by

this

benevolent

insomnia

may

reduce

inflammation

and

improve

memory

(Gamble

2014).

Entrepreneurs

could

stop

worrying

unnecessarily

about

their

sleep

patterns

if

they

understood

this

common

phenomenon.

“I

was

really

sick.

My

immune

system

wasn’t

working

very

well.

And

I

had

a

lot

of

trouble

with

my

sleep.”

“I

need

my

rest.

Exercise,

good

food,

everything

else

I

can

do

without.

But

if

I

don’t

get

enough

rest,

nothing

works.”

“My

mind

is

always

on.

I

didn’t

have

that

until

I

worked

for

myself.”

“I’m

always

having

ideas

about

the

business.

They’re

just

racing

all

over

the

place.

I

need

to

do

something

physical

to

flush

my

brain

or

it

just

gets

too

exhausting.”

“I

wake

up

from

about

1-‐3am.

Sometimes

2-‐4am.

I

might

have

a

cuppa

tea,

write

out

some

ideas.

Then

I

go

back

to

sleep

and

wake

up

refreshed

at

6.”

“If

I

don’t

get

enough

rest

I

can’t

think

straight

or

do

anything

for

the

next

few

days.

It’s

really

important.”

3.3.3. Time and control

The most common reason stated for going solo was not to have more money, but to

have more flexibility with time. Not necessarily wanting to work less hours overall,

S. Jade Barclay -‐ 18 -‐ burnoutprofile.com

MBA Thesis: Burnout, Stress, Fatigue + Solo Entrepreneurs 2015

respondents

described

a

desire

to

have

flexibility

overwhen

they

worked,

especially

to

spend

more

time

with

children,

less

time

commuting,

and

to

be

able

to

work

around

family

commitments

and

health

needs.

The

majority

of

respondents

(62.5%)

shared

that

unreasonable

and

inflexible

work

hours

in

a

previous

role

had

led

to

their

initial

experience

of

burnout,

and

that

having

time

to

rest

and

take

breaks

when

needed

enabled

them

to

not

experience

such

severe

burnout

symptoms

in

the

future.

They

also

described

a

sense

of

meaning

and

agency

that

comes

with

having

control

over

one’s

own

schedule.

“In

corporate,

I

copped

a

lot

of

flack

for

taking

time

off

and

I

got

really

sick.

Now

that

I

plan

my

breaks

in

advance,

I’ve

never

had

the

same

symptoms

since.”

“I

can

create

my

own

schedule,

and

take

big

chunks

of

time

away.

There

are

very

few

limitations

that

are

externally

generated.”

“I

turn

my

phone

to

airplane

mode

for

an

hour

every

day

and

get

down

to

the

beach.”

“On

my

days

off

I

do

something

really

restorative,

like

hiking.”

“Being

a

fulltime

mum

is

my

first

priority.

If

I

need

to,

I

want

to

be

able

to

drop

everything

to

be

there

for

my

kids

without

employees

or

investors

breathing

down

my

neck.”

While

every

respondent

mentioned

having

control

and

flexibility

over

their

schedule

was

a

dominant

reason

for

choosing

to

be

a

solo

entrepreneur,

only

one-‐third

of

the

respondents

actually

turned

up

on

time

for

their

scheduled

interview,

even

when

a

reminder

SMS

was

sent

to

their

phone

(for

50%

of

the

interviewees).

The

interviewees

scheduled

their

own

appointments

via

an

online

scheduler,

and

chose

their

own

date

and

time

for

the

interview.

However,

many

did

not

note

the

appointment

in

their

calendar,

or

thought

it

was

on

a

different

day

or

at

a

different

time

than

was

scheduled.

S. Jade Barclay -‐ 19 -‐ burnoutprofile.com

MBA Thesis: Burnout, Stress, Fatigue + Solo Entrepreneurs 2015

On

average,

the

researcher

spent

the

first

8-‐12

minutes

of

the

scheduled

interview

time

tracking

down

each

respondent

via

phone,

email

and

social

media.

3.3.4. Stress and pressure

When asked what caused the most stress or pressure, some said “Everything, I can’t

narrow it down,” while many respondents shared where their stress was vented rather

than what caused it. The most common area in which stress and pressure “came out”

was in their spousal relationships. Many cited previous financial pressures but that was

not a common stressor currently. Nothing specifically was attributed to causing the most

stress. However, when the respondents hadn’t had enough sleep, everything felt more

stressful and they were more irritable in their communications in the home.

“The

thing

that

gives,

where

my

stress

comes

out,

is

in

my

relationship

with

my

husband.

Whenever

I

am

tired

I

take

it

out

on

him.”

“I’m

still

stressed,

but

it’s

a

different

stress

now.”

“I

was

in

high

pressure

work,

with

high

expectations

on

performance

and

results.

That’s

when

I

got

burnt

out.”

“It

comes

down

to

the

basics.

If

I

don’t

get

enough

sleep

or

basic

nutrition

or

hydration,

I

just

can’t

handle

much

at

all

and

everything

feels

more

stressful.”

3.3.5. Support and isolation

While all described themselves as independent from an early age, some respondents

were very comfortable asking for help, while others only recently starting to develop this

skill. Almost all of the respondents felt they had a lot of support available to them, both

through friends and family and via professional networks. Paradoxically, the most

S. Jade Barclay -‐ 20 -‐ burnoutprofile.com

MBA Thesis: Burnout, Stress, Fatigue + Solo Entrepreneurs 2015

common

experience

of

isolation

did

not

occur

as

a

solo

entrepreneur,

but

when

respondents

were

in

traditional

employment.

Many

described

feeling

very

isolated

when

surrounded

by

lots

of

people

in

the

workplace.

The

worst

–

and

most

common

–

experience

of

organisational

culture,

when

a

person

or

team

in

the

role

of

providing

support

was

not

actually

supportive,

and

had

to

be

avoided

in

times

of

stress

rather

leaned

on.

“They

didn’t

believe

me

at

first.

It

took

my

supervisor

a

few

weeks

to

see

how

serious

it

was.”

“I

thought

they

were

there

for

me,

but

suddenly

I

found

myself

out

in

the

cold.”

“Having

‘named’

support

that’s

not

actually

supportive.

Like

when

everyone

knows

that

whoever

goes

and

talks

to

the

HR

department

about

their

troubles

is

getting

fired.”

“When

you

have

to

walk

on

eggshells

around

and

cover

your

*ss

in

front

of

them…

It

just

grinds

down

the

spirit.”

3.3.6. Introverts and extraverts

No questions were asked about introversion or extraversion, but many respondents

identified as one or the other as the reason for one of their other responses. The most

notable difference between self-‐described introverts and extraverts is that that

introverts describe feeling really productive on their own, whereas the extraverts would

prefer to have a partner in the business with them. Each respondent who self-‐identified

as an extravert mentioned having previous business partners, and some mentioned that

they’re only working solo because they’re looking for a new business partner. Introverts

did not mention a business partner, former, present or future, and described working

S. Jade Barclay -‐ 21 -‐ burnoutprofile.com

MBA Thesis: Burnout, Stress, Fatigue + Solo Entrepreneurs 2015

solo

as

a

conscious

decision

that

inoculated

them

from

the

burnout

factors

they

had

experienced

in

previous

workplaces.

“I’ve always been a bit of a lone wolf.”

“I’ve always been independent. Even as a child. I’m very

resilient.”

“I had a partner that really let me down. I’ve had a more

independent path. But I’m actively looking to take on a

partner right now.”

4. Key Findings

How solo entrepreneurs experience burnout, stress and fatigue

The overall findings indicate that solo entrepreneurs experience control, time, work, and

social support differently to employees. Consequently, the way they experience burnout

is also significantly different. Personal or organisational strategies used to alleviate or

prevent burnout in employee populations may require significant alteration to be

effective in the solo entrepreneur population.

Respondents described burnout in solo entrepreneurs as taking three distinct forms:

• Physical body breakdown;

• Mental fatigue; and

• Lack of challenge.

This differs significantly from the usual dimensions of employee burnout, which are

emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation, and diminished sense of personal

accomplishment (Maslach 1982). Solo entrepreneurs tend to personalise and internalise

their experiences more during phases of fatigue or burnout, in contrast to employees

who experience a sense of depersonalisation during burnout (ibid.).

S. Jade Barclay -‐ 22 -‐ burnoutprofile.com

MBA Thesis: Burnout, Stress, Fatigue + Solo Entrepreneurs 2015

Almost

all

respondents

interviewed

had

experienced

burnout

working

long

hours

in

high-‐pressure

corporate

or

consulting

careers

before

they

decided

to

work

for

themselves.

In

the

majority

of

cases,

becoming

a

solo

entrepreneur

was

the

cure

to

their

burnout,

rather

than

its

cause.

Also,

in

54.2%

of

respondents,

the

decision

to

go

solo

was

to

have

greater

flexibility

and

control

over

the

work

schedule,

with

69.2%

of

those

cases

wanting

more

time

to

be

flexible

around

time

with

children

and

family.

Often

the

area

in

which

the

respondent

felt

a

lack

of

control

in

the

workplace

and

served

as

a

catalyst

to

“inspire”

the

respondent

to

work

for

him-‐

or

herself

in

order

to

gain

more

control

over

that

particular

aspect

of

their

daily

work

experience:

schedule,

breaks,

support,

clientele,

food,

or

decision

making.

How

solo

entrepreneurs

prevent

and

cope

with

burnout,

stress

and

fatigue

Solo

entrepreneurs

reported

preventing

using

burnout

by

planning

work

breaks

or

vacations

in

advance,

balancing

their

workload,

and

utilising

social

and

professional

support

networks.

Despite

working

alone

now,

most

respondents

cited

that

they

felt

most

isolated

while

surrounded

by

people

in

a

previous

work

environment.

Many

described

having

support

systems

in

place

that

paid

lip

service

to

supporting

employees,

but

that

could

not

be

relied

upon

for

actual

support.

Many

reported

maintaining

a

brave

face

in

order

to

keep

one’s

job,

rather

than

being

able

to

use

support

systems

to

ease

the

work-‐related

burdens.

This

kind

of

pseudo-‐support

seemed

to

increase

stress

and

pressure

in

each

respondent

that

shared

such

an

experience,

and

became

a

key

reason

in

the

decision

to

go

solo.

The

majority

of

respondents

described

having

very

strong

personal

and

professional

support

networks

in

their

lives

that

they

accessed

regularly

as

a

solo

entrepreneur.

Self-‐identified

introverts

and

extraverts

expressed

very

different

experiences

of

solo

entrepreneurship.

Solo

entrepreneurs

who

described

themselves

as

“a

lone

wolf”

or

“a

solitary

person”

enjoy

the

experience

of

working

alone,

making

their

own

decisions,

having

no

one

to

answer

to,

and

having

contact

primarily

with

clients

and

close

friends

S. Jade Barclay -‐ 23 -‐ burnoutprofile.com

MBA Thesis: Burnout, Stress, Fatigue + Solo Entrepreneurs 2015

and

family

rather

than

colleagues.

Introverts

had

reliable

support

networks,

but

were

solitary

in

their

business

activities

and

business

decisions.

Extraverts,

however,

felt

they

did

their

best

work

in

partnerships,

had

often

worked

in

partnerships

in

the

past,

and

tended

to

only

work

solo

while

between

partnerships.

Every

respondent

was

aware

of

their

personal

early

warning

signals

and

coping

strategies

they

used

when

getting

close

to

burnout.

Most

spontaneously

said

that

they

would

like

to

be

more

proactive

and

preventative

about

“doing

what

works”

rather

than

waiting

until

they

hit

the

wall.

Common

coping

strategies

include

being

in

nature,

meditating,

showers,

yoga,

taking

a

walk.

Two

very

common

coping

strategies

were

making

lists

and

being

in

or

on

the

water

(swimming,

kayaking,

surfing,

walking

near

the

lake,

taking

a

bath).

Water

seems

to

have

soothing

effect

and

clears

the

mind,

which

is

a

common

need

among

all

the

respondents.

5. Key

Implications

Typical

measures

of

occupational

stress

and

job

burnout

do

not

fully

apply

to

entrepreneurial

stress

and

burnout

(Shepherd

et

al.

2010;

Grant

and

Ferris

2009).

This

research

contributes

in

part

to

start

shedding

some

light

on

the

issue

of

burnout

in

this

important

but

largely

understudied

population.

Employees

and

solo

entrepreneurs

do

not

experience

work

the

same

way,

and

they

do

not

experience

burnout

the

same

way.

Differences

in

control

of

schedule,

isolation,

and

downtime

results

in

burnout

manifesting

differently

in

solo

entrepreneurs

than

in

employees.

Employees

experience

burnout

as

a

combination

of

exhaustion,

cynicism,

and

professional

efficacy

(Maslach

1982;

Langballe

et

al.

2006),

whereas

solo

entrepreneurs

experience

three

very

different

versions

of

burnout:

physical

body

breakdown,

mental

exhaustion,

and

lack

of

challenge.

Respondents

consistently

reported

having

greater

control

over

their

schedule

as

solo

entrepreneurs,

but

also

having

the

experience

of

“always

being

on”

The

experience

of

“the

mind

always

racing

with

ideas,”

“there’s

always

another

decision

to

make,”

and

not

S. Jade Barclay -‐ 24 -‐ burnoutprofile.com

MBA Thesis: Burnout, Stress, Fatigue + Solo Entrepreneurs 2015

being

able

to

“leave

work

at

the

office

at

5pm

like

normal

people”

was

described

over

and

over

in

the

interviews.

Burnout

symptoms

were

experienced

in

the

past,

but

recurred

from