Professional Documents

Culture Documents

21 Signposts For Musical Analysis

21 Signposts For Musical Analysis

Uploaded by

CHRISTIAN HALFPENNYOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

21 Signposts For Musical Analysis

21 Signposts For Musical Analysis

Uploaded by

CHRISTIAN HALFPENNYCopyright:

Available Formats

21 signposts for musical analysis

1. Avoid mere description of the music (your readers will usually have the score in front of them)

unless you need it to support your conclusion.

2. An analysis may mention every detail of the score and still be pointless. Details are only relevant in

relation to others (e.g., similarities and dissimilarities).

3. You can rarely do without subdividing a work into sections (e.g., A-part, interlude, coda).

However, do not lose sight of the whole work.

4. Distinguish carefully between statements of fact and your personal views (e.g., 1 st vs. 3rd person)

5. ‘Motif x can be traced back to bar y’; ‘Beethoven repeats motif x in bar y’. The first statement is

definitely correct, the second one might be.

6. Not everything that does not fit into an expected form is ‘formless’.

7. When discussing a musical passage, you do not need to mention everything about it. Especially

features that occur frequently in the same work, you may want to summarise separately.

8. Music examples are only necessary if they illustrate a point which cannot be made clear by

referring to the score.

9. Pay attention to the frequency at which musical elements (e.g. a theme) are repeated.

10. When discussing the activity of a work, distinguish between note values and harmonic tempo.

11. Pay attention to phrasing. It often causes a piece to be experienced as lively or peaceful.

12. ‘Abnormalities’ are only audible if expectations were established beforehand (e.g. deceptive

cadence).

13. Beat-by-beat complete harmonic analyses often disclose a lack of understanding. Instead,

highlight repetition, similarity, and contrast. With unconventional elements, distinguish whether they

occur in contrast to commonplaces or in a wholly unconventional surrounding.

14. Statistics about rising and falling musical lines are usually pointless. Consider in what context

they appear (e.g. in exposed places like the beginning of a movement).

15. When analyzing vocal music, do not forget the text – it usually preceded the music and suggested,

e.g. tonality, form, and phrasing to the composer (or s/he may have consciously ignored it).

16. Observe how much music carries how much text.

17. Is the theme driving the accompaniment or vice versa? It can tell you something about the ‘power’

of a theme.

18. Not only themes and harmony can create form, but also instrumentation.

19. Consider a strongly expressive feature in its context, e.g. is it an unexpected surprise or the climax

of a steady development?

20. Never try to force a work into a certain form. Instead, celebrate its distinctiveness.

21. If you cannot find anything to say about a work or passage, nor discover any musical structure, do

not be afraid to go in the opposite direction. The absence or avoidance of form creates form in itself

(and can have its own charm!).

You might also like

- Erotic Cakes Guthrie Govan TranscriptionsDocument59 pagesErotic Cakes Guthrie Govan TranscriptionsCesar Berrios Dueñas100% (3)

- Hal Leonard Pocket Music Theory (Music Instruction): A Comprehensive and Convenient Source for All MusiciansFrom EverandHal Leonard Pocket Music Theory (Music Instruction): A Comprehensive and Convenient Source for All MusiciansRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Writing in MusicDocument3 pagesWriting in MusicbewescribNo ratings yet

- Humpty Dumpty Jazz AnalysisDocument4 pagesHumpty Dumpty Jazz AnalysisAugusto Pereira100% (4)

- Vocal Technique ChecklistDocument3 pagesVocal Technique ChecklistMichi AmamiNo ratings yet

- Dolls House Vs Dorian GrayDocument1 pageDolls House Vs Dorian GrayCHRISTIAN HALFPENNYNo ratings yet

- AnneboyerthetwothousandsDocument61 pagesAnneboyerthetwothousandsamboyer100% (3)

- Writing About Music: A Guide To Writing in A & I 24: Harvard College Program in General EducationDocument13 pagesWriting About Music: A Guide To Writing in A & I 24: Harvard College Program in General EducationRaajeswaran BaskaranNo ratings yet

- Oculus Non Vidit: Rhythm and AccentDocument9 pagesOculus Non Vidit: Rhythm and AccentFrancesco Russo100% (2)

- Erotic CakesDocument76 pagesErotic CakesFrancisco RuaNo ratings yet

- Variations On A Korean FolksongDocument5 pagesVariations On A Korean FolksongOhhannah100% (2)

- Prelims (Michaelmas) 23-24Document10 pagesPrelims (Michaelmas) 23-24sharon oliverNo ratings yet

- Writing About MusicDocument6 pagesWriting About MusicYolanda Zhang XiaoNo ratings yet

- Writing in Music: ScopeDocument3 pagesWriting in Music: ScopeMauricioNo ratings yet

- How To Write Listening LogsDocument12 pagesHow To Write Listening LogsJaime DaviesNo ratings yet

- Additional Information: 1.1 What Features in Your Piece Help You Determine The Prelude Type?Document26 pagesAdditional Information: 1.1 What Features in Your Piece Help You Determine The Prelude Type?aarrNo ratings yet

- How To Analyze A PoemDocument4 pagesHow To Analyze A PoemPartusa Cindrellene AnchelNo ratings yet

- African Thunderstorm QuestionsDocument7 pagesAfrican Thunderstorm Questionsseamus heaneyNo ratings yet

- Critical Analysis in The Humanities Music RevisedDocument2 pagesCritical Analysis in The Humanities Music Revisedtimmy doyleNo ratings yet

- Songwriters Workshop-What Makes A Good Song PDFDocument3 pagesSongwriters Workshop-What Makes A Good Song PDFMathew Wooyoung ChongNo ratings yet

- How To Analyse A PoemDocument3 pagesHow To Analyse A PoemGalo2142No ratings yet

- 15125-Concert Report InformationDocument3 pages15125-Concert Report InformationLeslie wanyamaNo ratings yet

- Test SoA03 S23Document4 pagesTest SoA03 S23amrsadek1No ratings yet

- Xviii. Analysis: The Big Picture: TranscriptionDocument12 pagesXviii. Analysis: The Big Picture: TranscriptionCharles Donkor100% (2)

- Fall 2016-CRW 3013-Literary Terms Handout (Poetry) - 1Document3 pagesFall 2016-CRW 3013-Literary Terms Handout (Poetry) - 1Jamie CheawNo ratings yet

- Jazz Piano Voicings For The Intermediate To Advanced PianistDocument1 pageJazz Piano Voicings For The Intermediate To Advanced PianistYerdana YerbolNo ratings yet

- Chapter G: Musical StyleDocument16 pagesChapter G: Musical StylemyjustynaNo ratings yet

- DMA TH Study GuideDocument11 pagesDMA TH Study GuideYeahNo ratings yet

- Chord Melody Chord & Notes PDFDocument5 pagesChord Melody Chord & Notes PDFAlessio MicronNo ratings yet

- Analysis MozartDocument16 pagesAnalysis MozartmarcoheliosNo ratings yet

- Article Presentation NotesDocument6 pagesArticle Presentation NotesEmily BrownleeNo ratings yet

- The Elements of A Great Pop Song - FromDocument4 pagesThe Elements of A Great Pop Song - Frompaulkriesch0% (1)

- Music TutorialDocument6 pagesMusic TutorialCMBYN nostalgiaNo ratings yet

- Poetry AnalysisDocument4 pagesPoetry AnalysisRebecca Haysom67% (3)

- WMMWDocument168 pagesWMMW351ryderhallNo ratings yet

- MelodyDocument7 pagesMelodyNevenaNo ratings yet

- Kia1 Analisis Jazz PDFDocument13 pagesKia1 Analisis Jazz PDFAdolfo Suarez GarciaNo ratings yet

- Unity and Variety - Tension and ReleaseDocument4 pagesUnity and Variety - Tension and Releasefrank orozcoNo ratings yet

- Jazz Improv in The Twentieth CenturyDocument41 pagesJazz Improv in The Twentieth CenturyswiffyNo ratings yet

- Easyreadmusic9781546933304 PDFDocument114 pagesEasyreadmusic9781546933304 PDFAnonymous Y5xa4hNo ratings yet

- Ezra Pound A Few DontsDocument4 pagesEzra Pound A Few DontsMissi Alejandrina WerehyenaNo ratings yet

- Senfter Ernste Gedanken PDFDocument8 pagesSenfter Ernste Gedanken PDFthieves11No ratings yet

- MMus APP7 - Thoughts On PerformanceDocument4 pagesMMus APP7 - Thoughts On PerformanceAntonio LoscialeNo ratings yet

- Erotic Cakes - The Backing TracksDocument76 pagesErotic Cakes - The Backing TracksCarlos Celis RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Additional Instruction For Episode 1Document4 pagesAdditional Instruction For Episode 1Michael Free100% (1)

- Erotic Cakes - The Backing TracksDocument59 pagesErotic Cakes - The Backing TracksPablo Café BarreiroNo ratings yet

- How To Analyse A PoemDocument1 pageHow To Analyse A PoemMolly ROBINSONNo ratings yet

- Arranging For Big Band 123Document4 pagesArranging For Big Band 123John Paluch71% (7)

- Once More On Musical Topics and Style AnalysisDocument16 pagesOnce More On Musical Topics and Style AnalysisAnonymous Cf1sgnntBJ100% (3)

- PoemsDocument36 pagesPoemsNahda RiyadhNo ratings yet

- Creative Principles: Getting Started Motivation / Dry Spells Helping Factors Miscellaneous Concerns FAQ ContentsDocument3 pagesCreative Principles: Getting Started Motivation / Dry Spells Helping Factors Miscellaneous Concerns FAQ ContentsAmy DunkerNo ratings yet

- Pound - A RetrospectDocument8 pagesPound - A RetrospectAndrei Suarez Dillon SoaresNo ratings yet

- Guide Musical Notes CompressedDocument45 pagesGuide Musical Notes CompressedWilliam DottoNo ratings yet

- What Makes A Great MelodyDocument10 pagesWhat Makes A Great MelodyGaby MbuguaNo ratings yet

- Songwriting CheatsheetDocument9 pagesSongwriting CheatsheetMakki ABDELLATIFNo ratings yet

- CH01 IM Power of MusicDocument5 pagesCH01 IM Power of MusicjpisisNo ratings yet

- Thoughts On Janet Schmalfeldt's Article PDFDocument3 pagesThoughts On Janet Schmalfeldt's Article PDFWilliam AntoniouNo ratings yet

- Guthrie Govan - ApostilaDocument11 pagesGuthrie Govan - ApostilaJosé Roberto0% (1)

- The Improvisation Continuum: Daryl RunswickDocument31 pagesThe Improvisation Continuum: Daryl RunswickPietreSonore100% (1)

- Language Games and Musical UnderstandingDocument14 pagesLanguage Games and Musical UnderstandingOrsaNo ratings yet

- Advice For Analysis Examination-2Document2 pagesAdvice For Analysis Examination-2CHRISTIAN HALFPENNYNo ratings yet

- Advanced Group Performance: Timber Lyrics: Cue Words in BoldDocument3 pagesAdvanced Group Performance: Timber Lyrics: Cue Words in BoldCHRISTIAN HALFPENNYNo ratings yet

- Britain Since 1970 - Some Examples-2Document9 pagesBritain Since 1970 - Some Examples-2CHRISTIAN HALFPENNYNo ratings yet

- Citation Guide and Presentation of Written Work - Sep 2015 PDFDocument14 pagesCitation Guide and Presentation of Written Work - Sep 2015 PDFCHRISTIAN HALFPENNYNo ratings yet

- Berlioz Harold in Italy Homework 2Document1 pageBerlioz Harold in Italy Homework 2CHRISTIAN HALFPENNYNo ratings yet

- Advanced Analysis - OverviewDocument13 pagesAdvanced Analysis - OverviewCHRISTIAN HALFPENNYNo ratings yet

- Beethoven Septet in E Flat Homework 2Document1 pageBeethoven Septet in E Flat Homework 2CHRISTIAN HALFPENNYNo ratings yet

- The TwentiesDocument18 pagesThe TwentiesCHRISTIAN HALFPENNYNo ratings yet

- As Music Homework: Note On Madrigals: Christian HalfpennyDocument1 pageAs Music Homework: Note On Madrigals: Christian HalfpennyCHRISTIAN HALFPENNYNo ratings yet

- Renaissance Composers EssayDocument2 pagesRenaissance Composers EssayCHRISTIAN HALFPENNYNo ratings yet

- What Is Diabetes ?: 5-10 YearsDocument3 pagesWhat Is Diabetes ?: 5-10 YearsCHRISTIAN HALFPENNYNo ratings yet

- Research Into Non-Invasive Blood Glucose Monitors: What I Did in My ProjectDocument5 pagesResearch Into Non-Invasive Blood Glucose Monitors: What I Did in My ProjectCHRISTIAN HALFPENNYNo ratings yet

- Greenhouse Effect: Greenhouse Effect: Retention of Heat in The Earth'sDocument5 pagesGreenhouse Effect: Greenhouse Effect: Retention of Heat in The Earth'sCHRISTIAN HALFPENNYNo ratings yet

- Semiotic Analysis EssayDocument10 pagesSemiotic Analysis EssayCHRISTIAN HALFPENNYNo ratings yet

- Ultraviolet PresentationDocument7 pagesUltraviolet PresentationCHRISTIAN HALFPENNYNo ratings yet

- GabrieliDocument1 pageGabrieliCHRISTIAN HALFPENNYNo ratings yet

- How Does Fitzgerald Tell The Story in Chapter 2Document1 pageHow Does Fitzgerald Tell The Story in Chapter 2CHRISTIAN HALFPENNYNo ratings yet

- How Does Fitzgerald Tell The Story in Chapter 4Document2 pagesHow Does Fitzgerald Tell The Story in Chapter 4CHRISTIAN HALFPENNYNo ratings yet

- The Courtship of MR LyonDocument2 pagesThe Courtship of MR LyonCHRISTIAN HALFPENNYNo ratings yet

- Drama History and DefinitionsDocument15 pagesDrama History and DefinitionsUm ZainabNo ratings yet

- NCERT Book Class 9 English Beehive Chapters PDFDocument148 pagesNCERT Book Class 9 English Beehive Chapters PDFSarahNo ratings yet

- The Hoax Heard Round The WorldDocument399 pagesThe Hoax Heard Round The Worldwrightee61100% (2)

- AaaDocument6 pagesAaaGlobal SaraeNo ratings yet

- Alice ReyesDocument8 pagesAlice ReyesVinaNo ratings yet

- PC5020 v3.0 Installation ManualDocument43 pagesPC5020 v3.0 Installation ManualFranklin JimenezNo ratings yet

- Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet StreetDocument3 pagesSweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet StreetCydreckNo ratings yet

- Watermarking: Anshuman MishraDocument16 pagesWatermarking: Anshuman MishraAmit MaharanaNo ratings yet

- How To Record A Guitar Track Using Adobe Audition 1Document10 pagesHow To Record A Guitar Track Using Adobe Audition 1rumkabubarceNo ratings yet

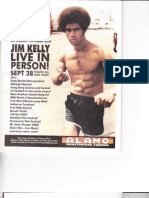

- Alamo Guide: Sep-Oct 2003Document32 pagesAlamo Guide: Sep-Oct 2003Alamo Drafthouse CinemaNo ratings yet

- Largo Bwv1056: Js Bach Arranged by SjnixonDocument9 pagesLargo Bwv1056: Js Bach Arranged by SjnixonBahar OssarehNo ratings yet

- Write Me A Poem, AI PoetryDocument45 pagesWrite Me A Poem, AI PoetryDaan LangeveldNo ratings yet

- BSC6900 UMTS Parameter Reference (V900R011C00 - 06)Document8,100 pagesBSC6900 UMTS Parameter Reference (V900R011C00 - 06)Mohamed MoujtabaNo ratings yet

- Elementary ObservationDocument3 pagesElementary Observationapi-371675597No ratings yet

- InfernoDocument2 pagesInfernoCaio HenriqueNo ratings yet

- Multiple Access ProtocolsDocument43 pagesMultiple Access ProtocolsSahilPrabhakarNo ratings yet

- Lagu NatalDocument14 pagesLagu NatalVeronika SetioningsihNo ratings yet

- Slave Mains On-Off Control: Amplificationj Attenuation SelectorDocument3 pagesSlave Mains On-Off Control: Amplificationj Attenuation SelectorTariq Zuhluf100% (2)

- Jack Teagarden 3Document5 pagesJack Teagarden 3Leonel Hitters100% (1)

- PCIe Equalization v01Document7 pagesPCIe Equalization v01Saujal Vaishnav100% (1)

- XC 003Document6 pagesXC 003mihailNo ratings yet

- Arctic Monkeys Teddy Picker PDFDocument4 pagesArctic Monkeys Teddy Picker PDFJosue De La RosaNo ratings yet

- Wagon Wheel Chords by Darius RuckerDocument3 pagesWagon Wheel Chords by Darius RuckermilesNo ratings yet

- C.PH.E.Bach - Hamburger Sonata, Wq133 PDFDocument8 pagesC.PH.E.Bach - Hamburger Sonata, Wq133 PDFIoNo ratings yet

- COSM2Document27 pagesCOSM2nav brunnNo ratings yet

- WD16 Suite 16Document20 pagesWD16 Suite 16api-26911443No ratings yet

- Cigolea - Cristinel ThesisDocument131 pagesCigolea - Cristinel ThesisLeonid Gourjev100% (1)

- Increase Price Proposal r1 StoreDocument3 pagesIncrease Price Proposal r1 StoreYuli AnaNo ratings yet

- Diameter ProtocolDocument122 pagesDiameter ProtocolMohammad Tayyab KhusroNo ratings yet