Professional Documents

Culture Documents

GLOBIL - Isprsarchives XL 7 W3 511 2015

GLOBIL - Isprsarchives XL 7 W3 511 2015

Uploaded by

Raymond LinatocCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Enemy - What Every American Should Know - Felix GreeneDocument418 pagesThe Enemy - What Every American Should Know - Felix GreeneElizabeth Pérez100% (2)

- Global Waste Outlook 2015 PDFDocument346 pagesGlobal Waste Outlook 2015 PDFAnita MarquezNo ratings yet

- Managing Conflicts in Protected AreasDocument110 pagesManaging Conflicts in Protected Areasgh29du7No ratings yet

- Ament R. Et Al. 2023. Conectividad Ecológica de Carreteras, Líneas de Ferrocarril y Canales (UICN)Document143 pagesAment R. Et Al. 2023. Conectividad Ecológica de Carreteras, Líneas de Ferrocarril y Canales (UICN)CAROL SANCHEZNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Applying Protected Area Management CategoriesDocument143 pagesGuidelines For Applying Protected Area Management CategoriesTRISHIA DELA CRUZNo ratings yet

- Marine Remote Sensing PDFDocument328 pagesMarine Remote Sensing PDFFarhan FarohiNo ratings yet

- IucnDocument136 pagesIucnapi-288962582No ratings yet

- Ibat Annual Report 2021Document18 pagesIbat Annual Report 2021suzukisplash1200No ratings yet

- A Strategic Framework For Biodiversity Monitoring in South African National ParksDocument10 pagesA Strategic Framework For Biodiversity Monitoring in South African National ParkssamuNo ratings yet

- Forest Restoration in LandscapesDocument440 pagesForest Restoration in Landscapesleguim6No ratings yet

- Miles 2007 RED Main TextDocument10 pagesMiles 2007 RED Main TextA WicaksonoNo ratings yet

- Values - Case - Study - Protecting - Mangroves - Philippines (1) (6751)Document3 pagesValues - Case - Study - Protecting - Mangroves - Philippines (1) (6751)Nataly Andrea Garcia GilNo ratings yet

- Africa Ecological Footprint Report - Green Infrastructure For Africas Ecological SecurityDocument72 pagesAfrica Ecological Footprint Report - Green Infrastructure For Africas Ecological SecurityewnjauNo ratings yet

- Provide Any Opening Remarks That May Assist in The Review of This ReportDocument30 pagesProvide Any Opening Remarks That May Assist in The Review of This ReportJo AgodillaNo ratings yet

- Carbon FinanceDocument50 pagesCarbon Financesayuti djNo ratings yet

- Sourcebook On Remote SensingDocument206 pagesSourcebook On Remote SensingJose Pacheco SilvaNo ratings yet

- IMFN Book Eng 9-13 HresDocument60 pagesIMFN Book Eng 9-13 HresRyan MorraNo ratings yet

- Global Biodiversity AssessmentDocument4 pagesGlobal Biodiversity AssessmentzeboblisshendrixNo ratings yet

- Management - Effectiveness - Evaluation - in - Protected - Areas 2010Document102 pagesManagement - Effectiveness - Evaluation - in - Protected - Areas 2010Adrianne BasantesNo ratings yet

- Mapping Actors in Value ChainDocument28 pagesMapping Actors in Value Chainrobert.delaserna0% (1)

- Resilience Herbivorous MonitoringDocument72 pagesResilience Herbivorous MonitoringAlin FithorNo ratings yet

- 2445 Global Protected Planet 2016 - WEBDocument84 pages2445 Global Protected Planet 2016 - WEBsofiabloemNo ratings yet

- Effective Biodiversity MonitoringDocument13 pagesEffective Biodiversity MonitoringAleydaNo ratings yet

- Natural SolutionsDocument130 pagesNatural SolutionsDaisy100% (3)

- WA BiCC Final ReportDocument99 pagesWA BiCC Final ReportVikram RaghavanNo ratings yet

- Publishing Camera Trap Data: A Best Practice GuideDocument62 pagesPublishing Camera Trap Data: A Best Practice GuideDenise EMNo ratings yet

- World Conservation Strategy IUCN-UNEP-WWF 1980 PDFDocument77 pagesWorld Conservation Strategy IUCN-UNEP-WWF 1980 PDFGabrielle NunagNo ratings yet

- Ecological Restoration For Protected Areas Principles, Guidelines and Best PracticesDocument133 pagesEcological Restoration For Protected Areas Principles, Guidelines and Best PracticesRafael GerudeNo ratings yet

- IBA MonitoringDocument38 pagesIBA MonitoringFathurrahman SidiqNo ratings yet

- Information Resources On Environmental Studies - An OverviewDocument11 pagesInformation Resources On Environmental Studies - An OverviewVenugopal ReddyvariNo ratings yet

- WWF DissertationDocument5 pagesWWF DissertationWhereToBuyCollegePapersSingapore100% (1)

- Poverty Equity and Rights in ConservationDocument173 pagesPoverty Equity and Rights in ConservationRomaric MawuleNo ratings yet

- 4Document40 pages4vanshNo ratings yet

- The GBIF Integrated Publishing Toolkit: Facilitating The Efficient Publishing of Biodiversity Data On The InternetDocument8 pagesThe GBIF Integrated Publishing Toolkit: Facilitating The Efficient Publishing of Biodiversity Data On The InternetRogelio Lazo ArjonaNo ratings yet

- Unep PDFDocument4 pagesUnep PDFNikos CuatroNo ratings yet

- Undpa Unep NRC Mediation FullDocument107 pagesUndpa Unep NRC Mediation Fulleyob tenchoNo ratings yet

- Organization Associated With Biodiversity Organization-Methodology For Execution IucnDocument45 pagesOrganization Associated With Biodiversity Organization-Methodology For Execution IucnmithunTNNo ratings yet

- Sekercioglu 2011 Promoting Community-BasedDocument5 pagesSekercioglu 2011 Promoting Community-BasedJuliánMolgutNo ratings yet

- Biodiversity Precautionary PrincipleDocument65 pagesBiodiversity Precautionary PrincipleLBROK100% (6)

- Accountingforconservation RLI Youngetal 2014Document14 pagesAccountingforconservation RLI Youngetal 2014davidNo ratings yet

- Textbook The Geo Handbook On Biodiversity Observation Networks 1St Edition Michele Walters Ebook All Chapter PDFDocument53 pagesTextbook The Geo Handbook On Biodiversity Observation Networks 1St Edition Michele Walters Ebook All Chapter PDFarthur.mitchell434100% (1)

- IUCNresource Kit A EngDocument96 pagesIUCNresource Kit A EngLais AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- State of The World's Waterbirds 2010Document24 pagesState of The World's Waterbirds 2010spnagy01No ratings yet

- Worboys Et Al 2015 Protected Area Governance and ManagementDocument992 pagesWorboys Et Al 2015 Protected Area Governance and ManagementGeorgeStefanKudor-GhitescuNo ratings yet

- Management Guidelines For IUCN Category V Protected Areas Protected Landscapes/SeascapesDocument141 pagesManagement Guidelines For IUCN Category V Protected Areas Protected Landscapes/SeascapesAnastasia GusevNo ratings yet

- GREEN-GREY COMMUNITY of PRACTICE. Practical Guide To Implementing Green-Gray Infrastructure, 2020Document172 pagesGREEN-GREY COMMUNITY of PRACTICE. Practical Guide To Implementing Green-Gray Infrastructure, 2020YasminRabaioliRamaNo ratings yet

- 1.1 To 1.11 - Decision Tree For MonitoringDocument34 pages1.1 To 1.11 - Decision Tree For MonitoringSherica IsaacsNo ratings yet

- (Mallari Et Al) Philippine Protected Areas Are Not Meeting The Biodiversity Coverage and Management Effectiveness Requirements of Aichi Target 11Document10 pages(Mallari Et Al) Philippine Protected Areas Are Not Meeting The Biodiversity Coverage and Management Effectiveness Requirements of Aichi Target 11Javier GamboaNo ratings yet

- Biological Resource Management: Pa PersDocument48 pagesBiological Resource Management: Pa PersSeputar InfoNo ratings yet

- Uicn Livelihoods, Povery and ConservationDocument167 pagesUicn Livelihoods, Povery and Conservationrafo76No ratings yet

- Genetic Frontier For Conservation - Synth Biology and Biodi ConservDocument184 pagesGenetic Frontier For Conservation - Synth Biology and Biodi ConservBarnaudNo ratings yet

- Nbsapcbw Seasi 01 PH enDocument23 pagesNbsapcbw Seasi 01 PH enPeng MacNo ratings yet

- IUCN Green List Standard Version 1.1Document43 pagesIUCN Green List Standard Version 1.1Santikumar AkoijamNo ratings yet

- Safeguarding The Blue Planet Six Strategies For AcDocument137 pagesSafeguarding The Blue Planet Six Strategies For Acrahul katariaNo ratings yet

- UNESCO Heritage Sites in North AmericaDocument2 pagesUNESCO Heritage Sites in North Americachandria congeNo ratings yet

- Harmful Algal Blooms (Habs) and Desalination: A Guide To Impacts, Monitoring, and ManagementDocument538 pagesHarmful Algal Blooms (Habs) and Desalination: A Guide To Impacts, Monitoring, and ManagementAly ShahNo ratings yet

- Feasibility Study of IKEA Carbon ProjectDocument27 pagesFeasibility Study of IKEA Carbon ProjectNguyễn Quang AnhNo ratings yet

- Wild LifeDocument44 pagesWild Lifeحماد حسينNo ratings yet

- Biodiversity Integrated Assessment and Computation Tool | B-INTACT: GuidelinesFrom EverandBiodiversity Integrated Assessment and Computation Tool | B-INTACT: GuidelinesNo ratings yet

- Microplastics in Fisheries and Aquaculture: Status of Knowledge on Their Occurrence and Implications for Aquatic Organisms and Food SafetyFrom EverandMicroplastics in Fisheries and Aquaculture: Status of Knowledge on Their Occurrence and Implications for Aquatic Organisms and Food SafetyNo ratings yet

- Choral SpeakingDocument3 pagesChoral Speakingzaimankb100% (3)

- AziziM PaperMakingFactoryDocument11 pagesAziziM PaperMakingFactorytazebachew birkuNo ratings yet

- 1st PPT - Forest EcologyDocument87 pages1st PPT - Forest EcologyMia KhufraNo ratings yet

- Impact of Population Problem On The Environment of BangladeshDocument10 pagesImpact of Population Problem On The Environment of BangladeshShahriar SayeedNo ratings yet

- Effects and Solutions of Food ScarcityDocument14 pagesEffects and Solutions of Food ScarcityHaziq HanafiNo ratings yet

- English 2sci21 2trim1Document2 pagesEnglish 2sci21 2trim1brook candyNo ratings yet

- Gr.9G Term 3 WorksheetsDocument11 pagesGr.9G Term 3 WorksheetsTarisha ChaytooNo ratings yet

- Amazon Tipping PointDocument6 pagesAmazon Tipping PointMarcos José Falcão De Medeiros FilhoNo ratings yet

- Deforestation Is The Permanent Destruction of Indigenous Forests and WoodlandsDocument3 pagesDeforestation Is The Permanent Destruction of Indigenous Forests and WoodlandsTara Idzni AshilaNo ratings yet

- Effects of Tropical Deforestation Policymaker SummaryDocument9 pagesEffects of Tropical Deforestation Policymaker SummaryhariNo ratings yet

- Sample Task 1 - 2Document90 pagesSample Task 1 - 2Saeid RajabiNo ratings yet

- Ecological ApproachDocument2 pagesEcological ApproachJonNo ratings yet

- Economic and Environmental Concerns in Philippine Upland Coconut Farms - An Analysis of Policy, Farming Systems and Socio Economic IssuesDocument64 pagesEconomic and Environmental Concerns in Philippine Upland Coconut Farms - An Analysis of Policy, Farming Systems and Socio Economic IssuesPogpog ReyesNo ratings yet

- Your PDF - IELTS Vocabulary & Ideas About The EnvironmentDocument9 pagesYour PDF - IELTS Vocabulary & Ideas About The EnvironmentMARCOS PRIETO RICONo ratings yet

- Land Degradation - Bangladesh PDFDocument16 pagesLand Degradation - Bangladesh PDFSiddique AhmedNo ratings yet

- Edexcel B Geography Unit 1 Revision BookletDocument45 pagesEdexcel B Geography Unit 1 Revision BookletIlayda UludagNo ratings yet

- Unit 5 Land and Water UseDocument133 pagesUnit 5 Land and Water UseMohammadFaisalQureshiNo ratings yet

- SCIENCE-9 Q1 W5 Mod5 ADMDocument19 pagesSCIENCE-9 Q1 W5 Mod5 ADMMönica MasangkâyNo ratings yet

- Essay On Cutting Down ForestDocument1 pageEssay On Cutting Down ForestJose JativaNo ratings yet

- Environment Communication Unit IDocument39 pagesEnvironment Communication Unit IWdymNo ratings yet

- Forests-Topical - KeyDocument6 pagesForests-Topical - KeyAyeshaNo ratings yet

- Women and Enviornmental Protection in Karnataka With Special Refrence To Salumarada ThimmakkaDocument2 pagesWomen and Enviornmental Protection in Karnataka With Special Refrence To Salumarada ThimmakkaNithyananda PatelNo ratings yet

- 2012 Kelloggs CRRDocument120 pages2012 Kelloggs CRRAli NANo ratings yet

- Bennett 2021Document29 pagesBennett 2021George NeyraNo ratings yet

- Final Revised PaperDocument61 pagesFinal Revised PaperBernard T. AsiaNo ratings yet

- Forest Man of India: Submitted ToDocument8 pagesForest Man of India: Submitted ToAman GuptaNo ratings yet

- Threats To Our Environment CLT Communicative Language Teaching Resources Pict - 83876Document19 pagesThreats To Our Environment CLT Communicative Language Teaching Resources Pict - 83876Pamela Soto VelasquezNo ratings yet

- Population and EnvironmentDocument29 pagesPopulation and Environmentdewi fatmaNo ratings yet

- Compliance Case Study: NestleDocument28 pagesCompliance Case Study: NestlephátNo ratings yet

GLOBIL - Isprsarchives XL 7 W3 511 2015

GLOBIL - Isprsarchives XL 7 W3 511 2015

Uploaded by

Raymond LinatocOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

GLOBIL - Isprsarchives XL 7 W3 511 2015

GLOBIL - Isprsarchives XL 7 W3 511 2015

Uploaded by

Raymond LinatocCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/277360198

GLOBIL: WWF's global observation and biodiversity information portal

Article · April 2015

DOI: 10.5194/isprsarchives-XL-7-W3-511-2015

CITATION READS

1 916

4 authors, including:

Aurelie Shapiro Susanne Schmitt

WWF Germany WWF United Kingdom

40 PUBLICATIONS 432 CITATIONS 2 PUBLICATIONS 1 CITATION

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Paolo Tibaldeschi

WWF-Norway

6 PUBLICATIONS 43 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Assessing Forest Degradation in DRC and the Congo Basin View project

Conservation Technologies and Methodologies View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Aurelie Shapiro on 15 March 2016.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XL-7/W3, 2015

36th International Symposium on Remote Sensing of Environment, 11–15 May 2015, Berlin, Germany

GLOBIL: WWF'S GLOBAL OBSERVATION AND BIODIVERSITY INFORMATION

PORTAL

A. C. Shapiro a, 1*, L. Nijsten b, S. Schmittc, P. Tibaldeschid

a

World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) Germany, Reinhardtstr. 18, 10117 Berlin, Germany - Aurelie.shapiro@wwf.de

b

World Natur Fonds (WWF) Netherlands, Driebergsweg 10, 3708 JB Zeist, Netherlands – lnijsten@wwf.nl

c

World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) United Kingdom, Brewery Road, Woking, Surrey GU21 4LL, UK -

sschmitt@wwf.org.uk

d World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) Norway, Kristian Augusts gate 7A, 0164 Oslo, Norway - ptibaldeschi@wwf.no

KEY WORDS: GIS, Remote Sensing, Monitoring, Evaluation, Impact, Wildlife, Habitat, Conservation

ABSTRACT:

Despite ever increasing availability of satellite imagery and spatial data, conservation managers, decision makers and planners are

often unable to analyze data without special knowledge or software. WWF is bridging this gap by putting extensive spatial data into

an easy to use online mapping environment, to allow visualization, manipulation and analysis of large data sets by any user.

Consistent, reliable and repeatable ecosystem monitoring information for priority eco-regions is needed to increase transparency in

WWF’s global conservation work, to measure conservation impact, and to provide communications with the general public and

organization members. Currently, much of this monitoring and evaluation data is isolated, incompatible, or inaccessible and not

readily usable or available for those without specialized software or knowledge.

Launched in 2013 by WWF Netherlands and WWF Germany, the Global Observation and Biodiversity Information Portal

(GLOBIL) is WWF’s new platform to unite, centralize, standardize and visualize geo-spatial data and information from more than

150 active GIS users worldwide via cloud-based ArcGIS Online. GLOBIL is increasing transparency, providing baseline data for

monitoring and evaluation while communicating impacts and conservation successes to the public.

GLOBIL is currently being used in the worldwide marine campaign as an advocacy tool for establishing more marine protected

areas, and a monitoring interface to track the progress towards ocean protection goals. In the Kavango-Zambezi (KAZA)

Transfrontier Conservation area, local partners are using the platform to monitor land cover changes, barriers to species migrations,

potential human-wildlife conflict and local conservation impacts in vast wildlife corridor. In East Africa, an early warning system is

providing conservation practitioners with real-time alerts of threats particularly to protected areas and World Heritage Sites by

industrial extractive activities. And for globally consistent baseline ecosystem monitoring, MODIS-derived data are being combined

with local information to provide visible advocacy for conservation. As GLOBIL is built up through the WWF network, the

worldwide organization is able to provide open access to its data on biodiversity and remote sensing, spatial analysis and projects to

support goal setting, monitoring and evaluation, and fundraising activities.

1. INTRODUCTION outcomes of investments and projects. As WWF is truly a

network, the Global Observation and Biodiversity Information

1.1 Conservation on a global scale Portal, (GLOBIL - http://globil.panda.org) was launched in

2013 to centralize and mobilize geo-spatial data from around

The World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) is one of the largest the organization for monitoring and evaluation, assessment of

international conservation organizations, comprised of a global ecosystem status and provide an outlet for public

network with more than 5,000 employees located in more than communications and marketing.

100 countries across the world. WWF is united by a single

mission: to stop the degradation of the planet's natural WWF hosts a wide range of spatial data, and putting this data in

environment and build a future in which humans live in a useable form on the internet increases not only visibility but

harmony with nature. Two major pillars underlie WWF’s uptake and integration of valuable conservation related datasets,

strategy: namely conservation of biodiversity in critical places, which encourages other organizations to acknowledge rapidyle

and reduction of the human footprint, or negative impacts of declining biodiversity and vulnerable ecosystems. Additionally,

human activity. this portal plays a role in assessing global data sets to align with

Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) indicators and

As WWF’s activities are largely supported by private and public targets which are also relevant to WWF’s work (Leadley et al.

donors, it is important that this conservation work be 2014). Monitoring biodiversity and the impacts and outcomes

transparent and adequately monitored and evaluated. WWF has of conservation projects at national, trans-boundary and global

been criticized in recent years over its conservation impacts, levels is an essential challenge for all conservation

and new efforts are underway to showcase activities and organizations supporting government efforts and the NGO and

1

* Corresponding author.

This contribution has been peer-reviewed.

doi:10.5194/isprsarchives-XL-7-W3-511-2015 511

The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XL-7/W3, 2015

36th International Symposium on Remote Sensing of Environment, 11–15 May 2015, Berlin, Germany

science community has been developing appropriate planning complicated dataset which normally requires long download

and monitoring methods (Kapos et al. 2008; Mascia et al. time and processing and technical knowledge and software.

2014).

1.3 Kavango-Zambezi Impact Monitoring

The Kavango-Zambezi trans-frontier conservation area (KAZA

TFCA) is a vast ecosystem straddling the borders of Namibia,

Angola, Zambia, Zimbabwe and Botswana which is the target

for sustainable development programs. WWF has been

supporting local partners in various conservation efforts in the

region, notably by monitoring species populations and their

movements over international boundaries. A complex

monitoring system for managing and evaluating efforts and

conservation impacts in all five countries has been established

by the donor agencies and includes data collection on wildlife

populations, eco-tourism operations and socio-economic

indicators is underway.

In 2014, WWF supported the development of the first KAZA-

wide land cover map, derived from Landsat imagery at 30m

Figure 1. the GLOBIL public web map gallery resolution. This land cover and land use map comprises more

than 10 categories relevant for important wildlife habitat and

The GLOBIL platform is a major effort to expose WWF’s data helps KAZA assess a majority of the required indicators for

holdings and increase transparency in conservation planning project evaluation. This map also provides the basis for

and execution of projects. GLOBIL lets the public know where conservation planning and wildlife corridor conservation and

WWF is working, why, and what are the outcomes. will be updated over time.

1.2 Marine Protected Areas Action Network

The establishment of marine protected areas (MPAs) has a

significant spatial component. Protection of Marine habitat is

currently far below the set policy targets and still in its early

days compared to terrestrial protection. A combination of

economic use of the marine environment and to be protected

habitats is a challenging geo-spatial puzzle. GLOBIL helps by

mapping existing MPAs and supporting work within the

complex legal framework in the marine realm. GLOBIL

generates real-time scorecards that show how jurisdictions are

advancing on the achievement of policy targets.

Figure 3. the KAZA web map summarized land cover and other

data in a series of monitoring landscapes.

Previously, the access and manipulation of a land cover map

would require specialized software and training. GLOBIL is

being used to centralize all data collected from specific

monitoring landscapes online, and enable managers and

decision makers to visualize, manipulate and interact with

monitoring data for project reporting and planning. The KAZA

monitoring system in GLOBIL links to live data shared from

partner organizations through web services, and combines them

Figure 2. Ocean Protection Map allows users to query how with remotely sensed land cover data, local data collections and

much of any country’s marine territory is protected more, also reducing the effort often required to download data

and share it in areas with limited bandwidth. The KAZA

With regard to marine spatial planning, GLOBIL contains monitoring system brings various datasets directly into the

layers and tools on economic use, habitat and species richness. hands of project managers. Finally, data collection apps are

These tools help determine which areas are most important for actively being developed to allow data upload from the field

conservation and MPA establishment. This data is accessible to with a mobile device, allowing conservation activities to be

anyone, allowing the easy manipulation and querying of a large, coordinated seamlessly across borders, without loss of data.

This contribution has been peer-reviewed.

doi:10.5194/isprsarchives-XL-7-W3-511-2015 512

The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XL-7/W3, 2015

36th International Symposium on Remote Sensing of Environment, 11–15 May 2015, Berlin, Germany

1.4 Africa Land Use Planning and Early Warning System – swiping and animation of time series enabled data, without the

ALES need for special software.

Increasing demand for commodities has made Africa a hot Using ALES, WWF and partners can engage at an early stage in

prospect for industrial expansion. Activities in the extractive the development process by reviewing the Environmental

industries such as mining, oil and gas is occurring at an Impact Assessment (EIA). WWF will also be able to propose

increasing pace. This boom is driving unprecedented expansion concrete policy recommendations such as Strategic

of infrastructure into sparsely populated regions that will Environmental Assessments (SEA) for the management of

require heavy infrastructure and large settled workforces (Weng specific areas. Finally, WWF staff can easily produce map

et al. 2013). All these developments will have a direct or outputs, query, interact and evaluate risk in various landscapes

indirect impact on WWF priority areas and other ecologically and address conservation interventions, policy

important regions. recommendations accordingly.

A major gap in conservation intervention is the lack of easily 1.5 Global Program Framework Reporting

available and early intelligence on major developments, their

associated environmental and social risks, as well as long-term In order to effectively meet conservation goals, WWF actively

development scenarios. The Africa Land use Planning and Early monitors a series of indicators to measure progress and impacts

Warning System (ALES) aims at filling this gap by integrating of conservation projects towards biodiversity goals, which are

into GLOBIL real-time environmental and development data. similar to Aichi targets defined by the Secretariat of the

This allows a user to visualize the extent of developments over Convention on Biological Diversity (Leadley et al. 2014). This

ecological areas of interest, understand their environmental and work includes compiling information available from global

social risk and find the companies behind it. In addition, ALES data-sets along with satellite-derived information, combined

also integrates long-term development scenarios, as well climate with data collected locally by WWF. For several global-scale

change data in order to visualize the extent of future indicators, WWF has acquired annual best-pixel MODIS

development and Climate change impacts in WWF priority composites from SarVision LLC for baseline mapping and

areas. ALES is a new platform hosting up to date spatially monitoring. These are 250m resolution cloud-free images of all

explicit data, and for some layers near-real time data on WWF priority ecoregions, allowing consistent measurement of

conservation interests, sensitive areas, developments and the natural forest cover and fragmentation consistently over time.

associated risks from new development projects in Africa. The

risk of all new development projects is evaluated for WWF

offices and partners in order to help engagement in the

development sector.

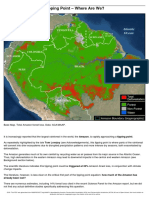

Figure 5. Deforestation assessment in Amazon (forest: green;

deforestation: red) from MODIS composite

Figure 4. ALES provides many interactive features to help Combining these satellite-derived data with other indicators,

determine overlaps of extractive industrry concessions and such as protected areas coverage, management effectiveness or

conservation areas wildlife counts, GLOBIL will provide a comprehensive view of

projects, and conservation impacts and will facilitate reporting

ALES focuses on four major development sectors including at the global level. Additionally this data will be published

extractive industries (oil and gas and mining), forestry, agro- alongside species information from local monitoring and other

industry and infrastructure. This platform helps WWF and sources such as the Living Planet Index (Loh et al., 2005). The

partners in three ways; (i) real time data allow to monitor interactive online system will support all manners of reports and

developments in order to engage at an early stage at the level of analysis, allowing monitoring and evaluation programs to

the government and the company (ii) by overlaying perform their own data analysis without specialized software or

development scenarios and their associated risks over key knowledge.

biodiversity areas, WWF can propose integrated land use plans

and related policies and (iii) the ability to find the company

behind a specific development allows to engage at the investor’s

level e.g. financial institutions outside the country of interest.

Several key features include online analysis of overlapping

areas, early warning of function on land use change, interactive

This contribution has been peer-reviewed.

doi:10.5194/isprsarchives-XL-7-W3-511-2015 513

The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XL-7/W3, 2015

36th International Symposium on Remote Sensing of Environment, 11–15 May 2015, Berlin, Germany

2. CONCLUSIONS Mascia, M.B. et al., 2014. Commonalities and

complementarities among approaches to conservation

2.1 Conservation in the cloud monitoring and evaluation. Biological Conservation,

169, pp.258–267.

As ecosystems worldwide degrade due to human impacts,

climate change and other large scale threats, it is more crucial Weng, L. et al., 2013. Mineral industries, growth corridors and

than ever for conservation organizations such as WWF to agricultural development in Africa. Global Food

increase transparency and showcase efforts and both positive Security, 2(3), pp.195–202. Available at:

and negative impacts. First, for donors and members who need http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S22119124130

to see where investments are going and under what context; and 00357 [Accessed March 23, 2015].

second, for effective monitoring and evaluation, and project

reporting. More often, project impacts are falsely correlated

with causes which are not spatially correlated, due to

misaligned scale or extent. The reach of projects and their

investments need to be openly communicated and spatially

correlated to correlate potential outcomes and impacts. This

also supports more focused conservation intervention and

improved project planning.

The GLOBIL platform has allowed WWF to open its spatial

databases and information to staff, members and the public,

allowing for an improved communications, reporting and

strategic planning. This spatial context translates to greater

conservation impacts, though refined project planning and

efficient targeting through a more informed context through

spatial data. GLOBIL allows anyone with an internet

connection to work with spatial data from any source, which

ultimately supports knowledgeable and transparent conservation

activities. Conservation activities can now be planned and

monitored in the cloud, in real-time.

This public sharing of spatial data in an interactive manner

should encourage other organizations, research institutions to

follow suit. At the rate of current biodiversity loss,

technological barriers and inaccessible data should no longer

limit conservation activities. The growth of web services allows

improved data sharing, allowing data holders to protect and

manage how their data is being used. A platform such as

GLOBIL can facilitate access to what are soon to be

overwhelming data streams. This spatial information is an

essential tool to inform and target conservation resources to

ensure that global ecosystem thrive with natural biodiversity

and resources for human livelihoods.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

WWF would like to acknowledge ESRI’s continued support for

GIS through their conservation grant program.

REFERENCES

Kapos, V. et al., 2008. Calibrating conservation: new tools for

measuring success. Conservation Letters, 1, pp.155–164.

Available at: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1755-

263X.2008.00025.x.

Leadley, P., Krug, C. & Alkemade, R., 2014. Progress towards

the Aichi Biodiversity Targets: an assessment of

biodiversity trends, policy scenarios and key actions. ,

4(78). Available at:

http://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:344577

[Accessed March 23, 2015].

This contribution has been peer-reviewed.

doi:10.5194/isprsarchives-XL-7-W3-511-2015 514

View publication stats

You might also like

- The Enemy - What Every American Should Know - Felix GreeneDocument418 pagesThe Enemy - What Every American Should Know - Felix GreeneElizabeth Pérez100% (2)

- Global Waste Outlook 2015 PDFDocument346 pagesGlobal Waste Outlook 2015 PDFAnita MarquezNo ratings yet

- Managing Conflicts in Protected AreasDocument110 pagesManaging Conflicts in Protected Areasgh29du7No ratings yet

- Ament R. Et Al. 2023. Conectividad Ecológica de Carreteras, Líneas de Ferrocarril y Canales (UICN)Document143 pagesAment R. Et Al. 2023. Conectividad Ecológica de Carreteras, Líneas de Ferrocarril y Canales (UICN)CAROL SANCHEZNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Applying Protected Area Management CategoriesDocument143 pagesGuidelines For Applying Protected Area Management CategoriesTRISHIA DELA CRUZNo ratings yet

- Marine Remote Sensing PDFDocument328 pagesMarine Remote Sensing PDFFarhan FarohiNo ratings yet

- IucnDocument136 pagesIucnapi-288962582No ratings yet

- Ibat Annual Report 2021Document18 pagesIbat Annual Report 2021suzukisplash1200No ratings yet

- A Strategic Framework For Biodiversity Monitoring in South African National ParksDocument10 pagesA Strategic Framework For Biodiversity Monitoring in South African National ParkssamuNo ratings yet

- Forest Restoration in LandscapesDocument440 pagesForest Restoration in Landscapesleguim6No ratings yet

- Miles 2007 RED Main TextDocument10 pagesMiles 2007 RED Main TextA WicaksonoNo ratings yet

- Values - Case - Study - Protecting - Mangroves - Philippines (1) (6751)Document3 pagesValues - Case - Study - Protecting - Mangroves - Philippines (1) (6751)Nataly Andrea Garcia GilNo ratings yet

- Africa Ecological Footprint Report - Green Infrastructure For Africas Ecological SecurityDocument72 pagesAfrica Ecological Footprint Report - Green Infrastructure For Africas Ecological SecurityewnjauNo ratings yet

- Provide Any Opening Remarks That May Assist in The Review of This ReportDocument30 pagesProvide Any Opening Remarks That May Assist in The Review of This ReportJo AgodillaNo ratings yet

- Carbon FinanceDocument50 pagesCarbon Financesayuti djNo ratings yet

- Sourcebook On Remote SensingDocument206 pagesSourcebook On Remote SensingJose Pacheco SilvaNo ratings yet

- IMFN Book Eng 9-13 HresDocument60 pagesIMFN Book Eng 9-13 HresRyan MorraNo ratings yet

- Global Biodiversity AssessmentDocument4 pagesGlobal Biodiversity AssessmentzeboblisshendrixNo ratings yet

- Management - Effectiveness - Evaluation - in - Protected - Areas 2010Document102 pagesManagement - Effectiveness - Evaluation - in - Protected - Areas 2010Adrianne BasantesNo ratings yet

- Mapping Actors in Value ChainDocument28 pagesMapping Actors in Value Chainrobert.delaserna0% (1)

- Resilience Herbivorous MonitoringDocument72 pagesResilience Herbivorous MonitoringAlin FithorNo ratings yet

- 2445 Global Protected Planet 2016 - WEBDocument84 pages2445 Global Protected Planet 2016 - WEBsofiabloemNo ratings yet

- Effective Biodiversity MonitoringDocument13 pagesEffective Biodiversity MonitoringAleydaNo ratings yet

- Natural SolutionsDocument130 pagesNatural SolutionsDaisy100% (3)

- WA BiCC Final ReportDocument99 pagesWA BiCC Final ReportVikram RaghavanNo ratings yet

- Publishing Camera Trap Data: A Best Practice GuideDocument62 pagesPublishing Camera Trap Data: A Best Practice GuideDenise EMNo ratings yet

- World Conservation Strategy IUCN-UNEP-WWF 1980 PDFDocument77 pagesWorld Conservation Strategy IUCN-UNEP-WWF 1980 PDFGabrielle NunagNo ratings yet

- Ecological Restoration For Protected Areas Principles, Guidelines and Best PracticesDocument133 pagesEcological Restoration For Protected Areas Principles, Guidelines and Best PracticesRafael GerudeNo ratings yet

- IBA MonitoringDocument38 pagesIBA MonitoringFathurrahman SidiqNo ratings yet

- Information Resources On Environmental Studies - An OverviewDocument11 pagesInformation Resources On Environmental Studies - An OverviewVenugopal ReddyvariNo ratings yet

- WWF DissertationDocument5 pagesWWF DissertationWhereToBuyCollegePapersSingapore100% (1)

- Poverty Equity and Rights in ConservationDocument173 pagesPoverty Equity and Rights in ConservationRomaric MawuleNo ratings yet

- 4Document40 pages4vanshNo ratings yet

- The GBIF Integrated Publishing Toolkit: Facilitating The Efficient Publishing of Biodiversity Data On The InternetDocument8 pagesThe GBIF Integrated Publishing Toolkit: Facilitating The Efficient Publishing of Biodiversity Data On The InternetRogelio Lazo ArjonaNo ratings yet

- Unep PDFDocument4 pagesUnep PDFNikos CuatroNo ratings yet

- Undpa Unep NRC Mediation FullDocument107 pagesUndpa Unep NRC Mediation Fulleyob tenchoNo ratings yet

- Organization Associated With Biodiversity Organization-Methodology For Execution IucnDocument45 pagesOrganization Associated With Biodiversity Organization-Methodology For Execution IucnmithunTNNo ratings yet

- Sekercioglu 2011 Promoting Community-BasedDocument5 pagesSekercioglu 2011 Promoting Community-BasedJuliánMolgutNo ratings yet

- Biodiversity Precautionary PrincipleDocument65 pagesBiodiversity Precautionary PrincipleLBROK100% (6)

- Accountingforconservation RLI Youngetal 2014Document14 pagesAccountingforconservation RLI Youngetal 2014davidNo ratings yet

- Textbook The Geo Handbook On Biodiversity Observation Networks 1St Edition Michele Walters Ebook All Chapter PDFDocument53 pagesTextbook The Geo Handbook On Biodiversity Observation Networks 1St Edition Michele Walters Ebook All Chapter PDFarthur.mitchell434100% (1)

- IUCNresource Kit A EngDocument96 pagesIUCNresource Kit A EngLais AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- State of The World's Waterbirds 2010Document24 pagesState of The World's Waterbirds 2010spnagy01No ratings yet

- Worboys Et Al 2015 Protected Area Governance and ManagementDocument992 pagesWorboys Et Al 2015 Protected Area Governance and ManagementGeorgeStefanKudor-GhitescuNo ratings yet

- Management Guidelines For IUCN Category V Protected Areas Protected Landscapes/SeascapesDocument141 pagesManagement Guidelines For IUCN Category V Protected Areas Protected Landscapes/SeascapesAnastasia GusevNo ratings yet

- GREEN-GREY COMMUNITY of PRACTICE. Practical Guide To Implementing Green-Gray Infrastructure, 2020Document172 pagesGREEN-GREY COMMUNITY of PRACTICE. Practical Guide To Implementing Green-Gray Infrastructure, 2020YasminRabaioliRamaNo ratings yet

- 1.1 To 1.11 - Decision Tree For MonitoringDocument34 pages1.1 To 1.11 - Decision Tree For MonitoringSherica IsaacsNo ratings yet

- (Mallari Et Al) Philippine Protected Areas Are Not Meeting The Biodiversity Coverage and Management Effectiveness Requirements of Aichi Target 11Document10 pages(Mallari Et Al) Philippine Protected Areas Are Not Meeting The Biodiversity Coverage and Management Effectiveness Requirements of Aichi Target 11Javier GamboaNo ratings yet

- Biological Resource Management: Pa PersDocument48 pagesBiological Resource Management: Pa PersSeputar InfoNo ratings yet

- Uicn Livelihoods, Povery and ConservationDocument167 pagesUicn Livelihoods, Povery and Conservationrafo76No ratings yet

- Genetic Frontier For Conservation - Synth Biology and Biodi ConservDocument184 pagesGenetic Frontier For Conservation - Synth Biology and Biodi ConservBarnaudNo ratings yet

- Nbsapcbw Seasi 01 PH enDocument23 pagesNbsapcbw Seasi 01 PH enPeng MacNo ratings yet

- IUCN Green List Standard Version 1.1Document43 pagesIUCN Green List Standard Version 1.1Santikumar AkoijamNo ratings yet

- Safeguarding The Blue Planet Six Strategies For AcDocument137 pagesSafeguarding The Blue Planet Six Strategies For Acrahul katariaNo ratings yet

- UNESCO Heritage Sites in North AmericaDocument2 pagesUNESCO Heritage Sites in North Americachandria congeNo ratings yet

- Harmful Algal Blooms (Habs) and Desalination: A Guide To Impacts, Monitoring, and ManagementDocument538 pagesHarmful Algal Blooms (Habs) and Desalination: A Guide To Impacts, Monitoring, and ManagementAly ShahNo ratings yet

- Feasibility Study of IKEA Carbon ProjectDocument27 pagesFeasibility Study of IKEA Carbon ProjectNguyễn Quang AnhNo ratings yet

- Wild LifeDocument44 pagesWild Lifeحماد حسينNo ratings yet

- Biodiversity Integrated Assessment and Computation Tool | B-INTACT: GuidelinesFrom EverandBiodiversity Integrated Assessment and Computation Tool | B-INTACT: GuidelinesNo ratings yet

- Microplastics in Fisheries and Aquaculture: Status of Knowledge on Their Occurrence and Implications for Aquatic Organisms and Food SafetyFrom EverandMicroplastics in Fisheries and Aquaculture: Status of Knowledge on Their Occurrence and Implications for Aquatic Organisms and Food SafetyNo ratings yet

- Choral SpeakingDocument3 pagesChoral Speakingzaimankb100% (3)

- AziziM PaperMakingFactoryDocument11 pagesAziziM PaperMakingFactorytazebachew birkuNo ratings yet

- 1st PPT - Forest EcologyDocument87 pages1st PPT - Forest EcologyMia KhufraNo ratings yet

- Impact of Population Problem On The Environment of BangladeshDocument10 pagesImpact of Population Problem On The Environment of BangladeshShahriar SayeedNo ratings yet

- Effects and Solutions of Food ScarcityDocument14 pagesEffects and Solutions of Food ScarcityHaziq HanafiNo ratings yet

- English 2sci21 2trim1Document2 pagesEnglish 2sci21 2trim1brook candyNo ratings yet

- Gr.9G Term 3 WorksheetsDocument11 pagesGr.9G Term 3 WorksheetsTarisha ChaytooNo ratings yet

- Amazon Tipping PointDocument6 pagesAmazon Tipping PointMarcos José Falcão De Medeiros FilhoNo ratings yet

- Deforestation Is The Permanent Destruction of Indigenous Forests and WoodlandsDocument3 pagesDeforestation Is The Permanent Destruction of Indigenous Forests and WoodlandsTara Idzni AshilaNo ratings yet

- Effects of Tropical Deforestation Policymaker SummaryDocument9 pagesEffects of Tropical Deforestation Policymaker SummaryhariNo ratings yet

- Sample Task 1 - 2Document90 pagesSample Task 1 - 2Saeid RajabiNo ratings yet

- Ecological ApproachDocument2 pagesEcological ApproachJonNo ratings yet

- Economic and Environmental Concerns in Philippine Upland Coconut Farms - An Analysis of Policy, Farming Systems and Socio Economic IssuesDocument64 pagesEconomic and Environmental Concerns in Philippine Upland Coconut Farms - An Analysis of Policy, Farming Systems and Socio Economic IssuesPogpog ReyesNo ratings yet

- Your PDF - IELTS Vocabulary & Ideas About The EnvironmentDocument9 pagesYour PDF - IELTS Vocabulary & Ideas About The EnvironmentMARCOS PRIETO RICONo ratings yet

- Land Degradation - Bangladesh PDFDocument16 pagesLand Degradation - Bangladesh PDFSiddique AhmedNo ratings yet

- Edexcel B Geography Unit 1 Revision BookletDocument45 pagesEdexcel B Geography Unit 1 Revision BookletIlayda UludagNo ratings yet

- Unit 5 Land and Water UseDocument133 pagesUnit 5 Land and Water UseMohammadFaisalQureshiNo ratings yet

- SCIENCE-9 Q1 W5 Mod5 ADMDocument19 pagesSCIENCE-9 Q1 W5 Mod5 ADMMönica MasangkâyNo ratings yet

- Essay On Cutting Down ForestDocument1 pageEssay On Cutting Down ForestJose JativaNo ratings yet

- Environment Communication Unit IDocument39 pagesEnvironment Communication Unit IWdymNo ratings yet

- Forests-Topical - KeyDocument6 pagesForests-Topical - KeyAyeshaNo ratings yet

- Women and Enviornmental Protection in Karnataka With Special Refrence To Salumarada ThimmakkaDocument2 pagesWomen and Enviornmental Protection in Karnataka With Special Refrence To Salumarada ThimmakkaNithyananda PatelNo ratings yet

- 2012 Kelloggs CRRDocument120 pages2012 Kelloggs CRRAli NANo ratings yet

- Bennett 2021Document29 pagesBennett 2021George NeyraNo ratings yet

- Final Revised PaperDocument61 pagesFinal Revised PaperBernard T. AsiaNo ratings yet

- Forest Man of India: Submitted ToDocument8 pagesForest Man of India: Submitted ToAman GuptaNo ratings yet

- Threats To Our Environment CLT Communicative Language Teaching Resources Pict - 83876Document19 pagesThreats To Our Environment CLT Communicative Language Teaching Resources Pict - 83876Pamela Soto VelasquezNo ratings yet

- Population and EnvironmentDocument29 pagesPopulation and Environmentdewi fatmaNo ratings yet

- Compliance Case Study: NestleDocument28 pagesCompliance Case Study: NestlephátNo ratings yet