Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Vaughan Williams

Vaughan Williams

Uploaded by

eliza_celisOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Vaughan Williams

Vaughan Williams

Uploaded by

eliza_celisCopyright:

Available Formats

Vaughan Williams's Melodic Style

Author(s): William Kimmel

Source: The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 27, No. 4 (Oct., 1941), pp. 491-499

Published by: Oxford University Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/739496 .

Accessed: 08/01/2015 23:24

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Oxford University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Musical

Quarterly.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Thu, 8 Jan 2015 23:24:45 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS'S

MELODIC STYLE1

By WILLIAM KIMMEL

AUGHAN WILLIAMS'S MELODIC INVENTION is perhapsthe most

characteristicelement of his musical idiom. An analysisof his

melodic style, therefore, would contribute more than any other

to an understandingof the roots, sources, and basic elements of

his style in general. Such an analysis reveals three primary influ-

encing factors-early church music, folk music, and contemporary

melodic devices.

The influence of Gregorian melodies is comparatively slight

and apparentonly in a few works, viz. the "Five Mystical Songs",

the "Three Choral Hymns", Flos Campi and the "Five Tudor

Portraits".In only the first and last of these are actual plainsong

melodies used, treated as obbligato parts, alternatingwith either

the solo or choral voices, which have original and independent

melodies. Here the plainsong is introduced purely for special

emotional or symbolic effect and has no influence upon the gen-

eral melodic structure of the song. More significantare the plain-

song elements that appearin Vaughan Williams's originalmelodic

style. The second and fourth of the "Five Mystical Songs" show

decided Gregorianinfluence.A comparisonof their floridcadences

1

Excepting four works, Sancta Chitas, Job, Benedicite and the "Mystical Songs",

all references in the following analysis are made to the complete scores. In the above-

mentioned cases the references are to the piano and vocal scores. For convenience, in

the quotations and footnotes, the following abbreviations have been used. Arabic

figures refer to pages and Roman to measures.In the case of the "Journalof the Folk-

Song Society", however, the Roman numeral refers to the volume number and the

Arabic to the page.

Benedic.-Benedicite

Chor. Hymn-Three Choral Hymns

Flos.-Flos Campi

J.F.S.-Journal of the Folk-Song Society

Land.-London Symphony

Mass.-Mass in G minor

Past.-Pastoral Symphony

Sancta.-Sancta Civitas

Shep.-Shepherds of the Delectable Mountains

Wenlock.-On Wenlock Edge

4 Poems.-Four Poems by Fredegond Shove

3 Songs.-Three Songs from Shakespeare

F. Symph.-Symphony in F Minor

491

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Thu, 8 Jan 2015 23:24:45 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

492 The Musical Quarterly

with those of typical plainsongmelodies2reveals not only a simi-

larity of melodic contour but the same rhythmic flexibility. The

consistentdiatonicmovement is particularlysuggestivewhen com-

pared with the typically angular character of most of Vaughan

Williams's melodies.8The metrical element in the songs partially

obscuresthe effect. Were all the notes of the fourth song reduced

to a common value, however, the generalcharacterwould be quite

obviously Gregorian.

The modality of these melodies is also significant evidence of

plainsong influence; but since this prominent feature of Vaughan

Williams's style is derived more from folk-song than from plain-

song it will be discussedin that connection. In the "Three Choral

Hymns" and in Flos Campi the Gregorian element is apparentin

the generally diatonic progression of the melodies, in the free

rhythmic flow, sometimes dependent almost entirely upon the

rhythm of the text, in the contrast between duple and triple note

groups,in the characteristicinitialinflectionsof the melodies,often

correspondingto those of the Gregorian psalm-tones,and in the

florid and modal cadences.4Aside from these few examples, in

which an incorporationof the plainsongstyle is quite appropriate

to the spirit of the texts, the Gregorian element is not significant

and can therefore hardly be considered a primary factor condi-

tioning Vaughan Williams'smelodic style.

The influence of I6th-century music is most apparentin the

Mass in G minor and is manifest more in the rhythmic structure

and general contour of the melodies than in their modality or

tonality. The predominanceof smooth diatonic progression,the

great freedom and independence of phrases, the lack of a fixed

metric division, necessitating frequent change of time signature,

the independence of stress with relation to bar-lines,the domina-

tion of musicalrhythm by that of the text-all bear witness to the

composer's complete familiarity with I6th-century contrapuntal

techniques.5Another significant factor is the ease with which the

themes lend themselvesto imitative treatmentand to the develop-

ment of a closely knit polyphonic texture. The appearanceof such

themes as those of the Credo and of the Gratiasagimus,however,

2 Cf. particularly Kyrie Deus sempiterne, Kyrie Alnie Pater, Adoro Te, Ant. Post

triduum.

3 Cf. below.

4 Cf. Chor. Hymn. 26-ii, 3-i, 28-i, 8-iii; Flos 8-iv.

5 Cf. Mass. 4-vii, 33-ii, 43-i.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Thu, 8 Jan 2015 23:24:45 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

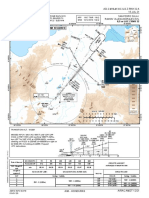

From "Modern British Composers:

Seventeen Portraits" by' Herbert Lambert

61V-ysJ-ws

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Thu, 8 Jan 2015 23:24:45 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Page 2 of the Holograph Score of Vaughan W\7illiams's Benedicite

(By Courtesy of the Oxford Universitv Press)

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Thu, 8 Jan 2015 23:24:45 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Vaughan Williams's Melodic Style 493

with their strong pentatonicbases,is evidence that this work is not

merely an imitation or rejuvenationof an old style but an amalga-

mation of certainold principleswith other, new concepts.

The i6th-century technique is found also, but to a lesser

degree, in Sancta Civitasand in the "Three ChoralHymns", where

typical melodies possess the characteristic i6th-century contour

and rhythmic freedom, although from the point of view of the

scale lines upon which they are based they are distinctly of the

2oth century.6

For the sake of completeness it is necessary to mention the

I6th-century Tallis melody in the Phrygian mode, which forms

the basis of the "Fantasiafor Double Stringed Orchestra",a work

that reflectsthe 6th century in other respectsalso.

Probably the strongest external factor that has influenced

Vaughan Williams's melodic invention is the English folk-song.7

6 Cf. Sancta. 46-vi, 48-x.

7 The following summary will serve to recall to mind the principal elements of

English folk-song. (For more complete discussion refer to the bibliography at the end

of the footnote.)

i. Modality. This probably provides the most characteristicfeature. Melodies have

been found in the Dorian, Mixolydian, Aeolian, Ionian, Phrygian, and Lydian

modes, although the latter two are rather infrequent. The purely pentatonic

scale is very rarely found in folk melodies. It is generally agreed, however,

among students of pentatonic music that many melodies which seem to use the

seven-tone system are essentially pentatonic, the two additional notes (pien)

appearing only as unessential notes on weak beats, either as changing notes or

as passing notes whose omission would not alter the fundamental form of the

melody.

2. Cadences. The normal progression is a fall to the final, although occasionally

the melody descends to the note below the final and returns. In most instances

this lower note is the flat seventh which is never altered for leading-tone pur-

poses.

3. Characteristicfigures. As a result of the modal and pentatonic basis of folk-

songs and the freedom from harmonic considerations with which they move,

certain characteristicmelodic patterns and figures are found to recur frequently

throughout folk-song literature, particularly at the beginning and end of the

melodies. Some of these figures, whose frequent occurrence in Vaughan Wil-

liams's music accounts in a large measure for its folk quality, are quoted at the

end of this article. They are taken from the "Journalof the Folk-Song Society".

In all of these figures the fundamentalnotes are the first, fourth, and fifth. The

various manners of filling in the intervals between the tones creates the charac-

teristics of each figure. It will be noticed that some of them are characteristic

also of Gregorian melodies.

4. Form. Because the folk influence upon Vaughan Williams's melodies has been

stronger in determining the character of the scale line and the intervals used

than in regulating the formal melodic structure, it is necessary here to mention

only the characteristicsymmetry and balance of phrases,the prevalence of five-

and seven-beat measures and the frequent appearances of three- and five-

measure phrases. [Footnotecontinuedon next page.]

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Thu, 8 Jan 2015 23:24:45 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

494 The MusicalQuarterly

The importance of modality in general in Vaughan Williams's

melodies has already been mentioned. It is not difficult to find

melodies, themes, and fragments based upon each of the modes

common to folk-song (and, incidentally, to i6th-century music).

Phrygian and Lydian modes are less frequently represented,while

examplesof the Aeolian, Mixolydian, and Dorian are more abun-

dant. It is rare, however, to find a single mode used consistently

for any length of time. There is frequent modulation from one

mode to another.Even in the shortersongs, such as the first of the

"Three Songs from Shakespeare",the tonality wavers between

the Dorian and Aeolian modes. In the more extended works, the

individual modal melodic fragments are only incidental elements

of a broader tonality in which modality is but a single factor.

Modal, pentatonic, Gregorian, and I6th-century elements are so

thoroughly mixed and combined with other elements, harmonic,

rhythmic, and contrapuntal, that it is difficult to find melodies

purely characteristicof any of those types which have exerted

their influence upon them.8 Of the five possible types of penta-

tonic scale discussedby Helmholtz,9 most of Vaughan Williams's

pentatonic melodies belong to the second and third types (natural

minor scale without second and sixth and naturalminor scale with-

out third and sixth) although examplesconforming to the fourth

type (majorscalewithout fourth and seventh) arenot infrequent."

If the term "pentatonic"is used in a free sense, numerous other

melodiesmay be found that employ five tones but that do not con-

form to the pure pentatonic without half-steps.There are some in

which both the sixth and seventh scale steps are lacking, and others

composed of but four notes; while still other six-tone melodies, in

Grove's Dictionary, article on "English Folk-Song."

"Journalof the Folk-Song Society".

Frederick Keel, "British Folk Song," in Zeitschrift der internationalenMusikgesell-

schaft, XIII (19I I-I2), p. 2i.

Frank Kidson and Mary Neal, "English Folk-Song and Dance", Cambridge, 1915.

Cecil Sharp,"EnglishFolk-song, Some Conclusions",London, I907.

Ralph Vaughan Williams, "English Folk-Song," in Encyclopedia Britannica, i4th

edition; "National Music",London, 1934.

Ernest Walker, "A History of Music in England",Oxford, 1907,chapt. xii.

8 The reader is referred, however, to the following examples of modal melodies:

Past. 58-i, 86-iv, io-ii, 52-i; Mass. 3-iii; 4 Poems, 14; 3 Songs, i.

9 Helmholtz, Hermann L. F.: "On the Sensationsof Tone", edition of 1930, Lon-

don, p. 26off.

l Wenlock 2-ii; Past. 4-iii, Io-ii, I5-ii, 33-ii, 66-ii; Shep. 32-ii; Sancta 5-iii, 34-xviii,

42-Xiii; Benedic. I-xiii, 40-ii.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Thu, 8 Jan 2015 23:24:45 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Vaughan Williams's Melodic Style 495

which the sixth degree is subsidiary,suggest both pentatonic and

modal backgrounds.1l

As was noted in connection with pentatonic folk melodies in

general (see footnote 7) certain characteristicfigures recur again

and again in Vaughan Williams's melodies. One could fill pages

with melodic quotations in which the typical folk figures quoted

at the end of this article appear as prominent melodic elements.l2

I do not mean to infer that Vaughan Williams consciously inserted

such figuresinto his melodies in order to secure a folk quality, but

I would ratherpoint out those featuresof his melodic style which

give it a definitely pastoral quality. It is hardly necessary to call

attention to the peculiarly blunt, vigorous energy created by a

melodic style so angular and unrefined as one based upon penta-

tonic scales. Much of the recognized austerity and frankness of

Vaughan Williams's music may be attributedto the generaluse of

incomplete scales and pentatonic melodies. It is not only when

seeking rustic atmospherethat he uses such melodies, for the pen-

tatonic element is also present in the Mass and other sacred choral

works, such as Flos Campi, Benedicite, and Sancta Civitas.It is to

be considered a pervasiveelement of his melodic style ratherthan

a specialpictorialor descriptivedevice.

The externalform of the folk tunes is not so much in evidence

in Vaughan Williams's melodies, which are much freer rhyth-

mically and structurally than typical folk-songs. Occasionally

melodies are found which are definite imitationsof folk melodies

with symmetricalphrasesand a strict metricalpattern.l3These are

unquestionably employed to evoke the definite mood associated

with folk-songs. Far more characteristicfrom the formal point of

view, however, are the very free, rhapsodicmelodies which may

be found in nearly all of the larger works-vocal and instru-

mental.14They are frequently marked "senzamisura"and where

possible are written without bar lines. Almost completely devoid

of harmonic background and of rhythmic regularity or metrical

symmetry, they are held together and given coherence by means

of a pedal sustainedbelow or above the melody or through some

11Cf. Mass I7-vi; Past. 35-vii, 86-iv; Shep. Io-x; Sancta 34-1O; Lond. 8o-iii; Bene-

dic. 27-ii, 34-vi.

12Any of the melodies referred to in the last three footnote references to Vaughan

Williams's music will serve as illustrations.

13 Cf. Past.

58-i, 86-iv; 4 Poems 4-ii.

14 Cf. Past. 84-iii, 54-ii; Sbep. i-i; Flos i6-ix.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Thu, 8 Jan 2015 23:24:45 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

496 The Musical Quarterly

recurring note or figure to which the melody frequently returns.

The significanceof this type of melody is emphasizednot only by

the frequency of its use but also by its invariableappearancein

prominent places. "The Shepherdsof the Delectable Mountains"

begins and ends with such a melody; two movements of the

"Pastoral"Symphony begin and three movements end with these

melodies;Flos Campi and "The Lark Ascending" both begin and

end thus; Sancta Civitas,Job, Benedicite, the Mass,the "Fantasia",

the Piano Concerto, "Five Tudor Portraits",the Symphony in F

Minor, in fact, almost all of the larger works, as well as many of

the songs, contain examplesof this free, meanderingmelody.

The length of these melodies varies from very long cadenza-

like ones to short fragments. The longer melodies are generally

given to a solo instrument-viola, violin, trumpet, or, as in the last

movement of the "Pastoral"Symphony, to a solo voice-and are

generally found beginning or ending a movement or forming a

connection between two sections. The shorter fragments are

sometimes found as primary themes,15sometimes as principal ele-

ments of the contrapuntal texture,16 and sometimes as counter-

melodies or as episodic figurationsover more solid harmonicpro-

gressions.17A conspicuous feature is the great frequency of triplet

figures and their alternation with duplets and quadruplets.It is

also characteristicto find repetitionsof the samemelodic fragment

in varying rhythmic patterns.Additional references are unneces-

sary since examplesmay easily be found in all of the works.

The emotional capacitiesof this type of melody.are varied.At

first, and most obviously, it is pastoral,suggesting the somewhat

wandering improvisationsof a shepherdon his pipe, and recalling

the similar treatment of the shepherd's tune in the last act of

Tristan.But the resultof its consistentand generaluse by Vaughan

Williams is more subtle and significant. The extreme structural

looseness with its correspondingrhythmic and harmonicfreedom

tends to destroy the consciousness of logic and form-of the

definite and concrete. The formal boundaries which in music,

even when most strongly felt, are undefinable,are expanded and

obliteratedand an indefinite mood between reverie and reflection

15 Cf. Past. 4-ii, 8-i, x -iv, 54-ii; F. Symph. 3o-x.

16Cf. Past. 9, i4; F. Sympb. second movement.

17 Cf. Past. 56; Shep. 25.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Thu, 8 Jan 2015 23:24:45 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Vaughan Williams's Melodic Style 497

results.This is most conducive to a suggestionof the mysticism of

such works as Sancta Civitas and Flos Campi and some of the

poems of Seumas O'Sullivan and Fredegond Shove. It is also an

importantfactor responsiblefor the quality of reflection and con-

templation often noted in Vaughan Williams's works.18It is quite

different from that vague, nostalgic impressionismthe French

achieved through the disrupting of the harmonic system and

through the exploitation of augmented chords and the higher dis-

sonances. It is more austere,more thoughtful-more English. The

fact that this type of melody is found so generally in most of the

major works, regardlessof their individualsubject matter or emo-

tional purport, suggests that it forms one of the essentiallyfunda-

mental qualities of Vaughan Williams's melodic style and is not

merely a device employed for a single descriptiveeffect.

The increasinguse of such a free and flexible melodic style is

paralleledby an increasinguse of atonality, melodically as well as

harmonically, noticeable in the later works. First appearing in

Sancta Civitas and Flos Campi, it is further developed in Job and

reaches its broadestapplicationin the Symphony in F Minor. Ex-

treme chromaticism-the juxtapositionof B-naturaland B-flat, of

F-natural and F-sharp, of C-natural,C-flat, and C-sharp,the fre-

quency of diminishedand augmented fourths, diminishedthirds,

etc.-prevents the feeling of either a modal or a harmonicbasis.In

the earlierworks this melodic atonality grows out of the harmonic

background and is more the result of harmonic writing. In the

highly contrapuntalSymphony in F Minor, however, the atonal-

ity derives rather from the melodic invention itself, harmonic

atonality being a result, not a cause.Even more than the free, rhap-

sodic melodies, mentioned above, do these twelve-tone-scale

melodies depend for their formal coherence upon recurringrhyth-

mic patterns and upon the device of repeating certain melodic

fragmentsin differentrhythms.

Until recently Vaughan Williams has made little use of so-

called exotic scales. The whole-tone scale appearsbut rarely and

then not as a melodic form but as the result of a harmonic pro-

gression through keys a major second apart. A few isolated ex-

amples of melodies based upon synthetic scales may be found in

18 Cf. the author's article, "Vaughan Williams's Choice of Words" in Music &

Letters, XIX (1938), p. I32.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Thu, 8 Jan 2015 23:24:45 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

498 The Musical Quarterly

Sancta Civitasand Flos Campil9but these are generally incidental

color lines rather than definite melodic patterns. Other melodic

fragments which appear to be based upon exotic scale forms are

really the result of unusualharmonicprogressionand are therefore

harmonic and not melodic phenomena. In the Symphony in F

Minor, however, synthetic scales assume a significant role in de-

termining the melodic style. More than six definite, arbitrary

octave divisionsmay be noted, some of them appearingonly inci-

dentally and others forming the principal thematic materialof a

movement. The following six divisions of the octave C-C repre-

sent these synthetic scalesas used by VaughanWilliams.

C C E F Ft A As B C

C D DSE F G A B C

C Cs D$ F$ G Gs Ag B C

C D Dt E Ft GS As C

C D D Fs G A B C

C Ds E F$ G As C

It will be noticed that three of these are eight-note scales, two of

them seven-, and one a six-note scale. When written in terms of

half-stepsthe logic and symmetry of most of them becomes more

apparent.

I I 3 I 3 I I

2 I I 2 I 2 2 1

I 2 2 I I 2 I 2

2 I I 2 2 2 2

2 I 3 I 2 2 I

3 I 2 I 3 2

A summary of the development of Vaughan Williams's me-

lodic style reveals that the extreme modernity of melodic inven-

tion in the F minor Symphony is not at all a new departurefor the

composerto make nor a distinct breakfrom previousstyles but the

logical continuation of a gradualevolution. The whole course of

development seems to have been away from accepted formulas

towards a new and independent melodic style, free, as far as pos-

sible, from all non-melodic influences.The presence of plainsong,

I6th-century polyphony, and folk-song influences in the early

19Cf. Sancta 47-vi; Flos 43-i.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Thu, 8 Jan 2015 23:24:45 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Vaughan Williams's Melodic Style 499

works reveals some of the meansby which this melodic liberation

was achieved. The progressionfrom modal to pentatonic and then

to duodecuple scales, and from the free verbal rhythm of plain-

song through i 6th-century styles to his own characteristicallyfree

and rhapsodicinstrumentalmelodic type, marksthe variousstages

of this development.

J.FlS. T- J.FS.Y-68

i ~ j IJJ_LJ ~-4 .l-- r

I J2J4jjl4?B w .

J. F .1F-9- i rTIPs?

x-Ai

.7F..$.~~~~~1

1I

wt _ .- J :P Il r *-- I 4' 11

__ T

..S. sr-68 7J.fS. it-too

,J FI, r Ir IIfr ,Fr J IJ

.

I I I ,I

1

ftr^^ iUi

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Thu, 8 Jan 2015 23:24:45 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Egnater SS4 Amp Switcher ManualDocument3 pagesEgnater SS4 Amp Switcher ManualMattNo ratings yet

- Lydia: Text by Charles-M Set by Gabriel FauDocument4 pagesLydia: Text by Charles-M Set by Gabriel FauRAQUEL PRECIADONo ratings yet

- Booklet CD93.268Document26 pagesBooklet CD93.268Elizabeth Ramírez NietoNo ratings yet

- Will Ye Buy A Fine DogDocument2 pagesWill Ye Buy A Fine DogClark BrydonNo ratings yet

- Teachers Pet Acordes - School of RockDocument3 pagesTeachers Pet Acordes - School of RockVladimir Zárate GayossoNo ratings yet

- Analysis On Alla HornpipeDocument1 pageAnalysis On Alla HornpipeChan VirginiaNo ratings yet

- Misty Mountains ChordsDocument1 pageMisty Mountains ChordsAlexiosKomnenosNo ratings yet

- The Cuckoo and Nightingale in Music PDFDocument18 pagesThe Cuckoo and Nightingale in Music PDFxNo ratings yet

- C3 Music of The RenaissanceDocument21 pagesC3 Music of The RenaissanceCESHNo ratings yet

- The Attributes of Folk and Popular SongsDocument39 pagesThe Attributes of Folk and Popular SongsTéê ÅñnNo ratings yet

- Two Madrigals, 1609 / John WilbyeDocument38 pagesTwo Madrigals, 1609 / John WilbyeDaniel Van GilstNo ratings yet

- Solfege Bingo Level 1 Do Re MiDocument13 pagesSolfege Bingo Level 1 Do Re Miubirajara.pires1100100% (1)

- When David HeardDocument5 pagesWhen David HeardsounditoutNo ratings yet

- Soul of My SaviourDocument1 pageSoul of My SaviourVivek SequeiraNo ratings yet

- IMSLP284770-PMLP45354-Fischer J.C. Preludes and Fugues - Ariadne Musica OrganaedumDocument42 pagesIMSLP284770-PMLP45354-Fischer J.C. Preludes and Fugues - Ariadne Musica OrganaedumisseauNo ratings yet

- Mozart Requiem BrisslerDocument81 pagesMozart Requiem BrisslerFrancesco MalapenaNo ratings yet

- Recital Program NotesDocument7 pagesRecital Program Notesapi-330249446No ratings yet

- Robin, Gentle RobinDocument3 pagesRobin, Gentle RobinMichelCostaNo ratings yet

- The Russian FiveDocument14 pagesThe Russian Fivetianna heppnerNo ratings yet

- Duarte Lobo (1564-1646) - Pater PeccaviDocument3 pagesDuarte Lobo (1564-1646) - Pater PeccaviFrancisco RosaNo ratings yet

- KV Choral Library 2014Document10 pagesKV Choral Library 2014Bruno Vargas0% (1)

- Tallis - Te Lucis Ante Terminum - MODERNADocument5 pagesTallis - Te Lucis Ante Terminum - MODERNASilvia Perucchetti100% (1)

- Love Like You: Steven UniverseDocument4 pagesLove Like You: Steven UniverseEmil ConcepcionNo ratings yet

- Vaughan-Williams - Five Variants On Dives and LazarusDocument1 pageVaughan-Williams - Five Variants On Dives and LazarusMatthew LynchNo ratings yet

- Lessons&Carols 2017Document20 pagesLessons&Carols 2017Jo CraddockNo ratings yet

- Pirate MusicDocument12 pagesPirate MusicrachelqNo ratings yet

- Zimmermann Violin Sonatas BookletDocument20 pagesZimmermann Violin Sonatas BookletKristina Ammattil100% (1)

- The Lark in The Clear Air PDFDocument1 pageThe Lark in The Clear Air PDFPaul DunleaNo ratings yet

- Rose ResponsesDocument8 pagesRose Responses赵诣No ratings yet

- Dirge+for+Two+Veterans 20220320125532Document6 pagesDirge+for+Two+Veterans 20220320125532HyunwookfullyNo ratings yet

- Shalom ChaverimDocument1 pageShalom ChaverimrzasaNo ratings yet

- Byrd - Laudibus in Sanctis 12Document12 pagesByrd - Laudibus in Sanctis 12Giuseppe Pecce100% (1)

- J. Strauss - Tales From The Vienna WoodDocument2 pagesJ. Strauss - Tales From The Vienna Woodlorenzopetrini6445No ratings yet

- Sally Gardens C MajorDocument4 pagesSally Gardens C Majorpan boruiNo ratings yet

- All The Pretty Little Horses Lead emDocument1 pageAll The Pretty Little Horses Lead emSydney BauerNo ratings yet

- Nabucco.16 17.guideDocument35 pagesNabucco.16 17.guideDimitri ChaplinNo ratings yet

- Feis Ceoil 1st & 2nd Prizewinners 2021Document6 pagesFeis Ceoil 1st & 2nd Prizewinners 2021The Journal of MusicNo ratings yet

- Bach and Numerology: 'Dry Mathematical Stuff'?: DavidDocument23 pagesBach and Numerology: 'Dry Mathematical Stuff'?: DavidMarius BahneanNo ratings yet

- Frank Sewall The CHRISTIAN HYMNAL Hymns With Tunes Philadelphia 1867Document249 pagesFrank Sewall The CHRISTIAN HYMNAL Hymns With Tunes Philadelphia 1867francis battNo ratings yet

- HMCC The Lords PrayerDocument1 pageHMCC The Lords Prayerelvin lozandeNo ratings yet

- High HopesDocument1 pageHigh HopesRidzuan JaafarNo ratings yet

- Let All The World in Every Corner SingDocument6 pagesLet All The World in Every Corner SingSteven L RalteNo ratings yet

- WCC - Westminster 2013 Tour Program, FinalDocument16 pagesWCC - Westminster 2013 Tour Program, FinalJeffrey GreinerNo ratings yet

- 2015 SSA Holiday SongbookDocument16 pages2015 SSA Holiday SongbookFelix BunkeNo ratings yet

- Andriessen Workers Union 1Document5 pagesAndriessen Workers Union 1Izabela RyšnikNo ratings yet

- Your Combined Hi-Ho Silver Lining WorkDocument3 pagesYour Combined Hi-Ho Silver Lining Workapi-377869240No ratings yet

- Glam RockDocument3 pagesGlam RockCzink TiberiuNo ratings yet

- ACDA MN Multicultural - 0Document3 pagesACDA MN Multicultural - 0Teuku AwaluddinNo ratings yet

- MR Q - Cocktail Boogie Liner NotesDocument15 pagesMR Q - Cocktail Boogie Liner NotesmusicmakerbluesNo ratings yet

- The French Art Song Style in Selected Songs by Charles Ives: Scholar CommonsDocument68 pagesThe French Art Song Style in Selected Songs by Charles Ives: Scholar CommonsFamigliaRussoNo ratings yet

- Un Cuaderno de Música Poco Conocido de Toledo. Música de Morales, Guerrero, Jorge de Santa María, Alonso Lobo y Otros, en El Instituto Español de Musicología (Barcelona), Fondo Reserva, MS 1Document32 pagesUn Cuaderno de Música Poco Conocido de Toledo. Música de Morales, Guerrero, Jorge de Santa María, Alonso Lobo y Otros, en El Instituto Español de Musicología (Barcelona), Fondo Reserva, MS 1Anonymous qZNimTMNo ratings yet

- 10 Mark - Locus IsteDocument1 page10 Mark - Locus IsteojharrisNo ratings yet

- White Christmas LyricsDocument2 pagesWhite Christmas LyricsAnonymous pRPtEPwFhENo ratings yet

- DMA Review Sheet MergedDocument33 pagesDMA Review Sheet MergedposkarziNo ratings yet

- Mary's Boy ChildDocument5 pagesMary's Boy ChildsandraheraldNo ratings yet

- Toot Toot Tootsie! (Goo Bye)Document7 pagesToot Toot Tootsie! (Goo Bye)HanslickNo ratings yet

- Szello ZugDocument2 pagesSzello Zugdaniel100% (1)

- Singing for Our Lives: Stories from the Street ChoirsFrom EverandSinging for Our Lives: Stories from the Street ChoirsNo ratings yet

- Edvard Grieg: The Story of the Boy Who Made Music in the Land of the Midnight SunFrom EverandEdvard Grieg: The Story of the Boy Who Made Music in the Land of the Midnight SunNo ratings yet

- 30133192Document30 pages30133192seeya DWBY0% (1)

- California DreamingDocument4 pagesCalifornia DreamingClaudia BaumannNo ratings yet

- Instruments of The WorldDocument31 pagesInstruments of The WorldEduard StancescuNo ratings yet

- DLP in Music 7 - Topic 5 Music of LuzonDocument7 pagesDLP in Music 7 - Topic 5 Music of LuzonJerielita MartirezNo ratings yet

- Prog Songanddance1 - 0328 2Document2 pagesProg Songanddance1 - 0328 2Fatih TuranNo ratings yet

- 04 - Culture Industry - Enlightenment As Mass Deception PDFDocument11 pages04 - Culture Industry - Enlightenment As Mass Deception PDFMikaela JeanNo ratings yet

- Music WORD POOL: Direction: Read The Statements Carefully and Look For The Correct Answers InsideDocument3 pagesMusic WORD POOL: Direction: Read The Statements Carefully and Look For The Correct Answers InsideClaudette Gutierrez CaballaNo ratings yet

- LuizaDocument2 pagesLuizaLuca NovelloNo ratings yet

- Failure CountersDocument28 pagesFailure CountersБотирали АзибаевNo ratings yet

- 17eskee069 As-2 PecDocument15 pages17eskee069 As-2 PecyashNo ratings yet

- Yellow Music Notes Vocal Trainer Facebook CoverDocument11 pagesYellow Music Notes Vocal Trainer Facebook CoverlonetNo ratings yet

- Qy100 Data ListDocument72 pagesQy100 Data ListY FelixNo ratings yet

- Head Over HeelsDocument89 pagesHead Over HeelsMichelle AshleighNo ratings yet

- Inferences Level 3 PracticeDocument6 pagesInferences Level 3 Practicebaobinh341102No ratings yet

- Ils ZDocument1 pageIls ZGabriela PinotNo ratings yet

- PDF Makalah Wheel Alignment - CompressDocument28 pagesPDF Makalah Wheel Alignment - CompressDo AlNo ratings yet

- OutlineDocument1 pageOutlineKOH KIAT HUNG MoeNo ratings yet

- Growth of Radio in PakistanDocument10 pagesGrowth of Radio in PakistanAyesha ZahraNo ratings yet

- UNIT 1 PPT Microwave TubesDocument45 pagesUNIT 1 PPT Microwave Tubesmanav aNo ratings yet

- All About MixingDocument16 pagesAll About MixingFrancescoMNo ratings yet

- 1999 Dassault Falcon 2000Document4 pages1999 Dassault Falcon 2000TesteArquivosNo ratings yet

- ORGANOS. The Organ in France - A Study of Its Mechanical Construction, Tonal Characteristics, and Literature - W. Goodrich 1917 PDFDocument230 pagesORGANOS. The Organ in France - A Study of Its Mechanical Construction, Tonal Characteristics, and Literature - W. Goodrich 1917 PDFGabriel Pizzi100% (1)

- Unison Songs For Bands: TromboneDocument30 pagesUnison Songs For Bands: TromboneNelson Oswaldo Castaneda JiménezNo ratings yet

- Workshop BrochureDocument1 pageWorkshop BrochureRajanikanth ArNo ratings yet

- List of Years in Philippine Television (2018-Present)Document65 pagesList of Years in Philippine Television (2018-Present)Pcnhs SalNo ratings yet

- Mapeh-3 Q4 W8-DLLDocument2 pagesMapeh-3 Q4 W8-DLLalice mapanaoNo ratings yet

- JULANGDocument19 pagesJULANGFA. SAptoNo ratings yet

- Activity Sheet Introduction To Radar Systems: Transmitters and Receivers, Parts 1 and 2Document4 pagesActivity Sheet Introduction To Radar Systems: Transmitters and Receivers, Parts 1 and 2Ciprian IonelNo ratings yet

- Lesson Notes FormatDocument5 pagesLesson Notes FormatMDNo ratings yet