Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Reading 17 PDF

Reading 17 PDF

Uploaded by

April Joy TamayoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Reading 17 PDF

Reading 17 PDF

Uploaded by

April Joy TamayoCopyright:

Available Formats

A reading from the CD accompanying

Developmentally Appropriate Practice in

Early Childhood Programs Serving Children

from Birth through Age 8, Third Edition.

17

Cultural Influences on the Development of

Self-Concept: Updating Our Thinking

Hermine H. Marshall

Reprinted from the November 2001 edition of Young Children

Categories:

Culture and Diversity

Early Childhood Professional

National Association for the Education of Young Children

www.naeyc.org

No permission is required to excerpt or make copies for distribution at no cost. For

academic copying by copy centers or university bookstores, contact Copyright Clearance

Center’s Academic Permissions Service at 978-750-8400 or www.copyright.com. For other

uses, email NAEYC’s permissions editor at lthompson@naeyc.org.

Cultural Influences

on the Development

of Self-Concept:

Updating Our Thinking

© Jonathan A. Meyers

Hermine H. Marshall

Why is it that some children try

new things with enthusiasm and

approach peers and adults with

confidence, whereas other chil-

dren seem to believe that they are

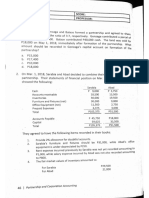

T welve years ago I assumed

along with many early

childhood educators that

approaching new situations with

confidence indicated a child’s strong

self-concept; hesitation and hanging

The last decade has seen an in-

crease in research on child develop-

ment in different cultures. Awareness

of this research has enhanced early

childhood educators’ sensitivity to

how perspectives may vary in cul-

incapable of succeeding in many back could indicate lack of self- tures that are different from the cul-

situations? . . . What can we learn esteem. In my review of research on ture of individual educators as well

from research that will allow us the development of self-concept as the dominant culture. Culture im-

written at that time, the notion that pacts not just which behaviors are

to help children approach new

children’s behavior is influenced by valued and displayed but also our in-

situations and other people with

their cultural background had only terpretations of these behaviors. As

confidence? begun to enter the research litera- a result of this decade of research, it

—H.H. Marshall, ture and thinking of early child- has become clear that what many of

“Research in Review. The hood educators. I pointed out us have taken for evidence of self-

Development of Self-Concept” briefly that cultural values can af- esteem is influenced by our cultural

fect self-esteem and different cul- perceptions. It is important, there-

tures may value and encourage dif- fore, to revisit some of the issues

ferent behaviors. For instance, taking related to self-concept develop-

Hermine H. Marshall, Ph.D., is emerita personal control, important in domi- ment in light of a more sophisti-

professor at San Francisco State Univer- nant American culture, might not be cated understanding of cultural in-

sity, at which she was coordinator of the valued in other cultures. Yet I indi- fluences. To this end, as educators

early childhood and master’s degree pro- cated that autonomy and initiative we need to increase our awareness

grams. She has conducted research on are behaviors to look for as reflect- that our perceptions, actions, and

self-concept, self-evaluation, and class-

room processes. She thanks Elsie Gee for ing positive self-concept. I implied interactions and those of children

critical comments on an earlier version that children who lacked these traits derive their meanings from the cul-

of this article. might have low self-esteem. tures in which they are embedded.

Young Children • November 2001 19

CULTURE, DIVERSITY, AND EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION

We need to increase our awareness that our perceptions, actions, and interactions and those of

children derive their meanings from the cultures in which they are embedded.

Constructing a view of self: and lacking in self-confidence— attempting to try things (Bacon &

independent/interdependent have a positive view of themselves Carter 1991). For these children too

and of their social relationships. standing back and observing rather

Children construct their views of Similarly, in other cultures where than exploring should not be taken

self “by participating in interac- interdependence or “relative en- as an indication of low self-esteem.

tions that caregivers structure ac- meshment” (Garcia Coll 1990) are Nevertheless, although Chinese

cording to cultural values about the seen as ideal mature relationships, parents tend to value interdepen-

nature of human existence” (Raeff interdependency and interpersonal dence and cohesion and may mini-

1997). In Western cultures, striving dependency are likely to be fostered mize the development of individu-

toward independence and individu- between young children and their ality within the family, Taiwanese

ality and asserting oneself are seen mothers. When asked about desir- and immigrant Chinese parents

as impor tant accomplishments able child behavior, mothers from seem to encourage independence

(Markus & Kitayama 1991). As a Latino cultures, such as Spanish- so that children will be able to suc-

consequence, Westerners perceive speaking Puerto Rican mothers, are ceed in the larger society (Lin & Fu

children who are outgo- 1990). Likewise, some

ing and eagerly explore Mexican immigrant fami-

new situations as demon- lies may begin to approve

strating competence and of their children’s inde-

having a positive self- pendent thinking related

concept, especially com- to school topics as they

pared to children who become more accultur-

do not appear to seek ated (Delgado-Gaitan 1994).

out and actively partici- In addition in Eastern cul-

pate in these situations. tures (Markus & Kitayama

In contrast, Eastern 1991) and Latino cultures

cultures place greater

© Elisabeth Nichols

(Parke & Buriel 1998), pri-

emphasis on maintain- mary concern centers on

ing harmonious, interde- other people and the self-

pendent relationships. in-relationship-to-other

Markus and Kitayama rather than self alone.

(1991) note that interde- Most people in these cul-

pendent views are also tures value developing

characteristic of many African, likely to focus on respectfulness empathetic understanding and at-

Latin American, and southern Euro- (respecto), a concept which as- tention to the needs of others.

pean cultures. (See also Greenfield sumes appropriate interrelated- These behaviors serve to maintain

1994.) In cultures influenced by ness. In contrast the Anglo mothers harmonious relationships more

Confucian and Taoist philosophies, in one study focused on autonomy than would attending to meeting

self-restraint and control of emo- and active exploration, reflecting one’s own needs.

tional expressiveness is considered more independent values (Harwood These contrasts should not be

an indication of social maturity 1992). Moreover, some cultures taken to mean that independence

(Chen et al. 1998). Asserting oneself such as traditional Navajo cultures and interdependence are mutually

may be seen as a sign of immaturity expect children to observe before exclusive (Raeff 1997). Both indepen-

(Markus & Kitayama 1991). Children

who are shy, reticent, and quiet are

likely to be considered competent

and well behaved by parents and We must be careful not to assume that just because children

teachers in the People’s Republic of or families are from a specific ethnic or racial group that they

China (Chen et al. 1998; Rubin

1998). These children—whom North necessarily share a common cultural experience. There are

American teachers from the domi- differences within cultures and within families.

nant culture might see as inhibited

20 Young Children • November 2001

dent and interdependent tendencies

are common to human experience. Children who are able to maintain comfort with behaviors that

People in Western cultures value re-

lationships and cooperation as well

are valued in their home as well as those valued in the wider

as independence. “Every group se- society may be most likely to have positive views of themselves

lects a point on the independence/in-

terdependence continuum as its cul-

in both cultural contexts.

tural ideal” (Greenfield 1994, 4).

are differences within cultures and meaning of children’s actions for

The impact on socialization within families. Other factors im- that family and child. It is impor-

pinge on how children are raised tant to recognize and affirm behav-

and development and the meanings accorded to be- iors valued by the home culture. It

Varieties of both independence havior, such as the family’s coun- is also essential to provide oppor-

and interdependence affect socializa- tries of origin, the length of time im- tunities for children to learn behav-

tion and development. Consequently migrant families have been in the iors that are valued by the Western

we should be aware that how chil- United States, the degree of accul- culture (Delpit 1988). Children who

dren see themselves in relationship turation the family has experi- are able to maintain comfort with

to others is also a part of their self- enced, educational background, behaviors that are valued in their

concept. Educators need to expand and social status (Delgado-Gaitan home as well as those valued in the

their views of what is considered 1994; Killen 1997; McLloyd 1999). wider society may be most likely to

important to self-concept beyond Some children and families expe- have positive views of themselves

the typical notions of autonomy, rience the influence of multiple cul- in both cultural contexts.

self-assertion, self-enhancement, tures. This is par ticularly true

and uniqueness and include char- when parents are from different

acteristics such as empathy, sensi- ethnic, racial, or cultural groups. In What does this mean in

tivity to others, modesty, coopera- these families parents may bring practice?

tion, and caring as well. values from two or more cultures to

Although it is important to be their views and practices in raising M y e a r l i e r re s e a rc h o n s e l f -

aware that our perceptions and in- children. Regardless of children’s concept development describes a

terpretations of behavior are influ- apparent ethnic or cultural back- number of ways to influence self-

enced by the culture(s) in which we ground, it is important for teachers concept. These include helping chil-

were raised and in which we reside to be sensitive to individual children dren (1) feel they are of value, (2)

and that the meaning of behavior and family members and to how a believe they are competent, (3) have

may vary for different cultures, we family’s beliefs, attitudes, and values some control over tasks and actions,

must be careful not to assume that may affect children’s behavior. (4) learn interpersonal skills. Also

just because children or families Attempting to understand what noted as important is becoming

are from a specific ethnic or racial each family values as important aware of your expectations for chil-

group that they necessarily share a behaviors and watching for these dren. The particular techniques for

common cultural experience. There behaviors may provide clues to the each of these recommendations re-

main valid today (see Marshall 1989).

Beyond these fundamentals, the

following steps are based on a more

sophisticated awareness of cultural

and individual variations in values

and behaviors. Using them as a

guide will increase your sensitivity to

the values and practices of the fami-

lies whose children are in your care

and enable you to support the devel-

opment of positive self-concepts.

© Judith Keith Rose

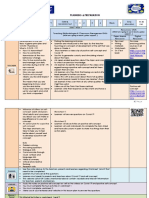

1. Be aware of the ways your

own culture influences your ex-

pectations of children. Think

about how you were raised, your

family values. What behaviors were

Young Children • November 2001 21

CULTURE, DIVERSITY, AND EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION

encouraged? How did your family 4. Use your basic knowledge of interact in a variety of ways. En-

make you feel proud? Talk to the culture to talk with each fam- large your repertoire of responses;

friends or other teachers about ily about its values and prac- some children will find more com-

their upbringing. Within your own tices. Learn what families think is fort in nonverbal acceptance—a

community, there are likely varia- important to consider for their chil- smile or nod—than praise. In all

tions in what families value and in dren. You might share with them cases, showing respect for ways of

the bases for positive self-concept. what you have been learning about interacting that derive from the

This reflection and knowledge may their culture or cultures. Explain home culture is critical to the sup-

help you begin to expand your that you recognize that every fam- port and development of a child’s

awareness of the indications of ily is different and that you would self-concept. Practices that are

positive self-concept. like to know what they think and clearly harmful to the child, of

what they value as important. Ask- course, should not be supported. In

ing about the families’ methods for such a case, being able to discuss

2. Consider the cultural back-

teaching and learning may be use- with the family why the practice is

grounds of the children in your

ful. Discuss what happens if child- detrimental is important (see

setting and their community. Ob-

ren raise questions or explore on Gonzalez-Mena & Bhavnagri 2000).

serve how children approach new

their own and how children and

tasks, relate to other people, and

6. Infuse the curriculum

react to praise. This may

and classroom environ-

raise some questions. Be a

ment with a rich variety of

good listener. If you teach

materials from the cultures

at the primary level, chat

of your children as well as

with the children before

other cultures. Parents may

and after school or at lunch-

be able to share songs or sto-

time. Be careful that surface

ries or bring in something

appearances do not influ-

special representing their

ence your perceptions or

home culture. Find books

interactions. Gather more

and posters that represent

information about the cul-

the children in your class.

tural and ethnic groups rep-

Introduce as snacks special

resented in your class (as

treats from the children’s

© Jonathan A. Meyers

noted below).

cultures. Seeing their ethnic

groups and cultures of ori-

3. Learn about the cul- gin valued will enhance chil-

tures from which the chil- dren’s self-concepts.

dren in your program or

school may come. Read

Conclusion

about the values and child

rearing practices of these cul- adults show respect. It is important It is not enough to assume that af-

tures. (See the “For further reading” to accept what family members say firming young children’s assertive-

list.) Talk to community leaders or as valuable information to consider ness, confidence, and independence

people you know who have greater and avoid letting your own values suffices to support self-concept de-

knowledge of these cultures. and methods stifle communication. velopment. Such qualities as show-

Contact community-based orga- ing respect for and being sensitive

nizations, such as the National 5. Build on what you have to others, learning by observing,

Council of La Raza (NCLR). Inviting learned from each family. Provide and exhibiting humility may also

representatives of such organiza- opportunities for children to learn evidence positive self-concept and

tions to talk to teachers in your set- in a variety of ways. For example, should be nourished. Acknowledg-

ting may be helpful. Still, do not as- children might learn by observing ing the contributions and values of

sume that this general information first, trying things out on their own, all the families whose children are

is sufficient. Further understanding or by doing tasks with a partner or in our care while also supporting

of the cultural background of par- group of peers. Children need op- children’s development of neces-

ticular children in your class will be portunities to demonstrate caring sary skills to succeed in main-

necessary since, in every cultural and cooperation. stream America is most likely to

and ethnic group, individual and All children will benefit from en- enhance the development of chil-

generational differences are likely. hanced opportunities to learn and dren’s self-esteem.

22 Young Children • November 2001

Building Cross-Cultural Relationships

Teaching children from a ents who have the confidence to be active advo-

culture with which I had no cates may articulate doubt about the reality of the

prior experience, I consis- school’s commitment to teaching their children.

tently relied on the extended When we first introduced more developmen-

family to share responsibil- tally appropriate practices at our school, teach-

ity for keeping the children ers were afraid that parents would be unsupportive.

safe and connected. Walking But when parents saw children’s enthusiasm—chil-

trips to the neighborhood dren who used to cry and cling on arrival now run-

park, where many urban ning in to join the others, children who used to be

evils could be found (but “sick” in the morning now bouncing up early to

which, as I explained earlier, are part of the be sure to get to school, and children whose par-

children’s world), were made safe by the presence— ents feared they would be bad now eagerly join-

at my invitation—of many of the culture’s elders. ing the group—their support flourished.

It must have been very hard for Iu Mien parents For me teaching in the Mien community has

to drop their child in my room on the first day of been a wonderful challenge. My previous experi-

kindergarten. Here was a teacher who didn’t know ence had been mostly with children of European

the child’s language, who didn’t look like anybody American and African American cultures with

they knew, except maybe a social worker. What in which I am very familiar. Mien culture was alto-

my voice, my face, my demeanor could reassure gether new to me. But I found the Mien people

them that I would take the very best care of their forthcoming about sharing their cultural beliefs

most precious child? What in the room and the and practices, and I simply asked if I was unsure

songs and stories could reassure the children that of something. On issues of death and funerals, it

this would be a great place to be for three hours surprised me to learn that Mien people don’t

every day? practice protracted grieving rituals because they

The Mien people have endured rudeness and in- believe that the longer you grieve, the more difficult

consideration even to get as far as my door. There you make it for the departed to go to the next world.

was often a lot of confusion about legal addresses, I would ask, observe, visit! I risked cultural blun-

immunizations, custody, birth certificates—even ders and noticed when I blundered. Whenever I was

about names. People at the registration table may invited to weddings, birthday parties, cultural

have been loud and brusque—characteristics sel- events, I’d go. I would step outside the school sys-

dom seen in a Mien person in a public setting. A tem to help families get mental health services, le-

translator may or may not have been available. So gal advice, and citizenship classes. In teaching adult

when they arrived at my room, I tried my best to literacy, I learned more and more about life in the

look reassuring. I invited parents to stay for a refugee camps in Laos and Thailand.

while if their child seemed unsure, and I con- I’ve learned that, as Bateson says, “Living in a

nected them with parents I already knew from pre- society made up of different ethnic groups offers

vious years. From the children’s enthusiasm for a paradigm for learning to participate without

this wonderful place set up just for them, most knowing all the rules and learning from the pro-

parents were able to hope it would be good. cess without allowing the rough edges to create

Parents with a long family history of school suc- unbridgeable conflict” (1994, 153). Clearly I am

cess may not need the same reassurance. For going beyond the boundaries of the classroom in

nearly every parent, however, there is anxiety: Will defining my obligations as a teacher. But I am very

the school be a good place for so precious a child? concerned that children get skills, and I cannot

But higher anxiety must be the common immi- be an effective teacher of children unless I know

grant experience, especially when there are lan- what is meaningful and engaging to them. Skills

guage barriers. African Americans experience as- learning can occur in the midst of any topic,

pects of anxiety as well. Those viewed as outsiders theme, or activity; it must, however, be grounded

by people in official roles have a hard time. Par- in what is important to the learner.

Source: Reprinted from K. Evans and K.S. Rencken, “Kathleen’s story,” The Lively Kindergarten: Emergent

Curriculum in Action by E. Jones, K. Evans, and K.S. Rencken (Washington, DC: NAEYC, 2001), 113–15.

Young Children • November 2001 23

CULTURE, DIVERSITY, AND EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION

References Markus, H.R., & S. Kitayama. 1991. Culture and the self: McAdoo, H.P., ed. 1997. Black families.

Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Bacon, J., & H.L. Carter. 1991. Culture and math- Psychological Review 98: 224–53. NAEYC. 1993. Educating yourself about

ematics learning: A review of the literature. Marshall, H.H. 1989. Research in Review: The

Journal of Research and Development in Edu- development of self-concept. Young Children

diverse cultural groups in our country

cation 25: 1–9. 44 (5): 44–51. by reading. Young Children 48 (3): 13–

Chen, X., P.D. Hastings, K.H. Rubin, J. Chen, G. McLloyd, V. 1999. Cultural influences in a multi- 16.

Cen, & S. Stewart. 1998. Child-rearing atti- cultural society: Conceptual and methodologi- Pomerleau, A., G. Malcuit, & C. Sabatier.

tudes and behavioral inhibition in Chinese cal issues. In Cultural processes in child devel- 1991. Child-rearing practices and par-

and Canadian toddlers. Developmental Psy- opment, Minnesota Symposia on Child ent beliefs in three cultural groups of

chology 34: 677–86. Psychology, vol. 29, ed. A.S. Masten, 123–26. Montréal: Québéçois, Vietnamese, Hai-

Delgado-Gaitan, C. 1994. Socializing young chil- Parke, R.D., & R. Buriel. 1998. Socialization in the

dren in Mexican-American families: An intergen-

tian. In Cultural approaches to parenting,

family: Ethnic and ecological perspectives. In

erational perspective. In Cross-cultural roots of Handbook of child psychology, vol. 3: Social, ed. M.H. Bornstein, 46–48. Hillsdale, NJ:

minority child development, eds. P.M. Greenfield emotional, and personality development, 5th ed., Erlbaum.

& R.R. Hocking, 55–86. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. ed. N. Eisenberg, 463–552. New York: Wiley. Rothenberg, B.A. 1995. Understanding and

Delpit, L. 1988. The silenced dialogue: Power and Raeff, C. 1997. Individuals in relationships: Cul- working with parents and children from

pedagogy in educating other people’s children. tural values, children’s social interactions, and rural Mexico: What professionals need to

Harvard Educational Review 58: 280–98. the development of an American individualis- know about child rearing. Menlo Park, CA:

Garcia Coll, C. 1990. Developmental outcome of tic self. Developmental Review 17: 205–38. Children’s Health Council, Center for

minority infants: A process-oriented look into Rubin, K.H. 1998. Social and emotional devel-

our beginnings. Child Development 61: 270–89. opment from a cultural perspective. Develop-

Children and Family Development Press.

Gonzalez-Mena, J., & N.P. Bhavnagri. 2000. Di- mental Psychology 34: 611–15. Saracho, O.N., & B. Spodek, eds. 1983.

versity and infant/toddler caregiving. Young Understanding the multicultural experi-

Children 55 (5): 31–35. ence in early childhood education. Wash-

Greenfield, P.M. 1994. Independence and inter- For further reading ington, DC: NAEYC.

dependence as developmental scripts: Impli- Thomas, R.M. 1988. Oriental theories of

cations for theory, research, and practice. In Bromer, J. 1999. Cultural variations in child human development: Scriptural and

Cross-cultural roots of minority child develop-

ment, eds. P.M. Greenfield & R.R. Hocking, 1–

care: Values and actions. Young Children popular beliefs from Hinduism, Bud-

37. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. 54 (6): 72–78. dhism, Confucianism, Shinto, and Islam.

Harwood, R.L. 1992. The influence of culturally Derman-Sparks, L., & the A.B.C. Task New York: Peter Lang.

derived values on Anglo and Puerto Rican Force. 1989. Anti-bias curriculum: Tools

mothers’ perceptions of attachment behav- for empowering young children. Wash-

ior. Child Development 63: 822–39. ington, DC: NAEYC.

Killen, M. 1997. Commentary: Culture, self and Garcia, E.E. 1997. The education of Hispan-

development: Are cultural templates useful or Copyright © 2001 by the National Associa-

ics in early childhood: Of roots and tion for the Education of Young Children.

stereotypic? Developmental Review 17: 239–49.

Lin, C.C., & V.R. Fu. 1990. A comparison of child- wings. Young Children 52 (3): 5–14. See Permissions and Reprints online at

rearing practices among Chinese, immigrant Little Soldier, L. 1992. Working with Native www.naeyc.org/resources/journal.

Chinese, and Caucasian-American parents. American children. Young Children 47

Child Development 61: 429–33. (6): 15–21.

24 Young Children • November 2001

You might also like

- Typical and Atypical DevelopmentDocument24 pagesTypical and Atypical DevelopmentXyxy MeimeiNo ratings yet

- Edu 530: The Child and Adolescent Learners and Learning PrinciplesDocument6 pagesEdu 530: The Child and Adolescent Learners and Learning PrinciplesApple Apdian BontilaoNo ratings yet

- PERDEV - Q1 - Mod1 - Knowing OneselfDocument23 pagesPERDEV - Q1 - Mod1 - Knowing Oneselfjoshua sean100% (3)

- The Development of Self Concept PDFDocument9 pagesThe Development of Self Concept PDFLone SurvivorNo ratings yet

- Module 5 Social and Emotional Development of Children and AdolescentsDocument11 pagesModule 5 Social and Emotional Development of Children and Adolescentsjaz bazNo ratings yet

- Edu 714 History of Education in Nigeria PDFDocument121 pagesEdu 714 History of Education in Nigeria PDFAbdulmumin UsmanNo ratings yet

- War in Bathroom InstructionsDocument2 pagesWar in Bathroom Instructionsapi-325714386No ratings yet

- The Development of Self Concept PDFDocument9 pagesThe Development of Self Concept PDFLone SurvivorNo ratings yet

- Transformative School Leadership in Homeschools: Forming Character in Moral EcologyFrom EverandTransformative School Leadership in Homeschools: Forming Character in Moral EcologyNo ratings yet

- Literature CritiqueDocument14 pagesLiterature CritiqueJohnNo ratings yet

- Tugas Psikologi PendidikanDocument11 pagesTugas Psikologi PendidikanBhang BhochilNo ratings yet

- Maccoby 1992Document12 pagesMaccoby 1992SHARON GUIANELLI CARHUAMACA ALBUJARNo ratings yet

- PSY101-Sulibran-Activity 1Document3 pagesPSY101-Sulibran-Activity 1Kent VillelaNo ratings yet

- Measuring Creativity From The Child's Point of View: Mary MeekerDocument11 pagesMeasuring Creativity From The Child's Point of View: Mary Meekersazzad hossainNo ratings yet

- ChildAndAdolescent ReviewerDocument5 pagesChildAndAdolescent ReviewerMichelle Villareal CuevasNo ratings yet

- PPD chp8Document8 pagesPPD chp8asti indahNo ratings yet

- Emotional DevelopmentDocument2 pagesEmotional DevelopmentHumaNo ratings yet

- What Is Our Purpose?: Planning The InquiryDocument4 pagesWhat Is Our Purpose?: Planning The InquiryPatriciaNo ratings yet

- Sachi Anjunkar Cross Cultural CieDocument3 pagesSachi Anjunkar Cross Cultural Ciesvavidhya libraryNo ratings yet

- Nagc-Asynchronous Development-Tip SheetDocument2 pagesNagc-Asynchronous Development-Tip Sheetapi-351751281No ratings yet

- Ece 15 - Module 1 - LacoDocument6 pagesEce 15 - Module 1 - LacoJELLAMIE LACONo ratings yet

- Colmhefferonsthesis DramaDocument140 pagesColmhefferonsthesis DramaFrancisca PuriceNo ratings yet

- Positive Youth Development, Willful Adolescents, and MentoringDocument14 pagesPositive Youth Development, Willful Adolescents, and MentoringpoopmanNo ratings yet

- Module 3-Final-Child & AdoDocument7 pagesModule 3-Final-Child & AdoPie CanapiNo ratings yet

- The History of ECE: Who's Who?Document29 pagesThe History of ECE: Who's Who?jade tagabNo ratings yet

- Emotional DevelopmentDocument8 pagesEmotional DevelopmentJeremy Dela Rosa100% (1)

- J. Russell, How Children Become Moral Selves: Building Character and Promoting Citizenship in EducationDocument4 pagesJ. Russell, How Children Become Moral Selves: Building Character and Promoting Citizenship in EducationRiniNo ratings yet

- Child Development AssignmentDocument13 pagesChild Development AssignmentMAKABONGWE SHAQUILLE100% (1)

- Intrinsic Motivation 2Document42 pagesIntrinsic Motivation 2Bonsik BonsNo ratings yet

- B.ed EssayDocument2 pagesB.ed EssayPooja GowdaNo ratings yet

- Figure Out Your ThoughtsDocument50 pagesFigure Out Your ThoughtsMaria Victoria Padro100% (3)

- Impact of Parenting Style, Emotional Maturity, and Social Competence On Cultural Intelligence Among Adolescents of Kerala... A Critical AnalysisDocument8 pagesImpact of Parenting Style, Emotional Maturity, and Social Competence On Cultural Intelligence Among Adolescents of Kerala... A Critical AnalysisAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- Developmental Reading 2Document51 pagesDevelopmental Reading 2Arissa Jane LacbayNo ratings yet

- Jjm1 - Jjm1 Task 1: Human Development Theories Ciara Ayala Pujols Western Governors UniversityDocument6 pagesJjm1 - Jjm1 Task 1: Human Development Theories Ciara Ayala Pujols Western Governors UniversityCiara AyalaNo ratings yet

- Field Study 1 ReviewersDocument13 pagesField Study 1 ReviewersJovie Dealca PratoNo ratings yet

- Concept of Childhood and AdolescenceDocument15 pagesConcept of Childhood and AdolescenceNikhil Vivek 'A'No ratings yet

- Childhood Studies An Overview ofDocument6 pagesChildhood Studies An Overview ofFabiana EstrellaNo ratings yet

- Final Requirement Educ 101Document20 pagesFinal Requirement Educ 101Vince Andrei MayoNo ratings yet

- Developmental Psychology Chapter 1 8Document39 pagesDevelopmental Psychology Chapter 1 8kentjelobernardoNo ratings yet

- Action Research Planner PPL Ammended 1Document14 pagesAction Research Planner PPL Ammended 1api-437156113No ratings yet

- Self EsteemDocument6 pagesSelf EsteemSoledad CruzNo ratings yet

- Enculturation and SocializationDocument8 pagesEnculturation and SocializationpunjtaareNo ratings yet

- BlablablaDocument6 pagesBlablablaNathaniel AzulNo ratings yet

- F S Research Findings Findings: Stages of Adolescent DevelopmentDocument4 pagesF S Research Findings Findings: Stages of Adolescent DevelopmentewrerwrewNo ratings yet

- 2017 Australian Mensa Initiative - Sensitivity Rev 0 PDFDocument8 pages2017 Australian Mensa Initiative - Sensitivity Rev 0 PDFgenerjustnNo ratings yet

- 1 Rogoff, Correa-Chávez y Silva-Cultural Variation in Childrens Attention and LearningDocument6 pages1 Rogoff, Correa-Chávez y Silva-Cultural Variation in Childrens Attention and LearningJuan MezaNo ratings yet

- MODULE 10-B - EARLY CHILDHOOD ADocument14 pagesMODULE 10-B - EARLY CHILDHOOD AKaren GimenaNo ratings yet

- PSY230 Textbook NotesDocument32 pagesPSY230 Textbook NotesEmilyNo ratings yet

- The Family: RLE Activity Week 4 Group 2Document6 pagesThe Family: RLE Activity Week 4 Group 2Matthew De PakwanNo ratings yet

- Emotional DevelopmentDocument2 pagesEmotional DevelopmentGuodaIndriunaiteNo ratings yet

- Module 4-Final-Child & AdoDocument5 pagesModule 4-Final-Child & AdoPie CanapiNo ratings yet

- Delany & Cheung 2020 - Culture and Adolescent DevelopmentDocument12 pagesDelany & Cheung 2020 - Culture and Adolescent Developmentpsi.valterdambrosioNo ratings yet

- Darie and MaicaDocument86 pagesDarie and Maicabeverly100% (1)

- Lilly Creativityearlychildhood DoneDocument29 pagesLilly Creativityearlychildhood Doney9cyhsjvkgNo ratings yet

- School Evaluation FrameworkDocument3 pagesSchool Evaluation FrameworkarhamkNo ratings yet

- LANZDocument2 pagesLANZMayflor BarlisoNo ratings yet

- CreativityDocument17 pagesCreativityJr MontanaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 158.195.4.7 On Fri, 02 Dec 2022 10:35:40 UTCDocument13 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 158.195.4.7 On Fri, 02 Dec 2022 10:35:40 UTCZuzana KriváNo ratings yet

- MultikulturalDocument10 pagesMultikulturalNeng Defa Alwiyyah Idrus XIA1No ratings yet

- F.2 - Human Development Diversity & LearningDocument5 pagesF.2 - Human Development Diversity & LearningShankar Kumar mahtoNo ratings yet

- Rottger-Rossler Et Al 2013 Socializing EmotionsDocument29 pagesRottger-Rossler Et Al 2013 Socializing EmotionsCaio MorettoNo ratings yet

- Development Stages in Middle and Late AdolescenceDocument5 pagesDevelopment Stages in Middle and Late AdolescenceNeslierae MonisNo ratings yet

- Importance of Sex Education in Schools: Literature Review: Maria Maqbool and Hafsa JanDocument7 pagesImportance of Sex Education in Schools: Literature Review: Maria Maqbool and Hafsa JanMichaer AmingNo ratings yet

- ThehsuDocument12 pagesThehsuApril Joy TamayoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 ShorDocument5 pagesChapter 1 ShorApril Joy TamayoNo ratings yet

- Operations Strategy It Operations StrategyDocument9 pagesOperations Strategy It Operations StrategyApril Joy TamayoNo ratings yet

- 3.MAJOR GENRES OF 21st Century LitDocument20 pages3.MAJOR GENRES OF 21st Century LitApril Joy TamayoNo ratings yet

- Kashato-Shirts Compress PDFDocument20 pagesKashato-Shirts Compress PDFApril Joy Tamayo100% (2)

- Write Your Answer On The Space Provided Before The NumberDocument4 pagesWrite Your Answer On The Space Provided Before The NumberApril Joy TamayoNo ratings yet

- 1 Savemore CO CASE ANALYSISDocument4 pages1 Savemore CO CASE ANALYSISApril Joy TamayoNo ratings yet

- Research DesignDocument9 pagesResearch DesignApril Joy Tamayo100% (1)

- University of Northern Philippines: College of Business Administration and AccountancyDocument2 pagesUniversity of Northern Philippines: College of Business Administration and AccountancyApril Joy TamayoNo ratings yet

- The Adult Self Processes and Paradox SheaDocument8 pagesThe Adult Self Processes and Paradox SheaEduardo Martín Sánchez Montoya100% (1)

- Kolehiyo NG Lungsod NG Lipa: Bachelor of Science in Criminology DepartmentDocument8 pagesKolehiyo NG Lungsod NG Lipa: Bachelor of Science in Criminology DepartmentPaul Henry ErlanoNo ratings yet

- MIND According To Vedanta - Tattvaloka OnlineDocument6 pagesMIND According To Vedanta - Tattvaloka Onlinekmeena73No ratings yet

- THE SOCIOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE OF THE SELF - THE SELF AS A PRODUCT OF SOCIETY - IamRolexDocument3 pagesTHE SOCIOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE OF THE SELF - THE SELF AS A PRODUCT OF SOCIETY - IamRolexangelica LeeNo ratings yet

- The Navigators of The AbZu - Part OneDocument198 pagesThe Navigators of The AbZu - Part Onesaviour link100% (1)

- MRR 4 V3Document12 pagesMRR 4 V3Cyruz LapinasNo ratings yet

- Lec 1Document59 pagesLec 1Asvk VinayakNo ratings yet

- SS199202Document16 pagesSS199202XynNo ratings yet

- Philosophy: Historical Period School of Thought Main Features, Beliefs Notable PhilosophersDocument8 pagesPhilosophy: Historical Period School of Thought Main Features, Beliefs Notable PhilosophersJhiamae PiqueroNo ratings yet

- Experiential Activity #1 M.TAGUIBALOSDocument6 pagesExperiential Activity #1 M.TAGUIBALOSMayeyean TaguibalosNo ratings yet

- Animal Magnetism and Mesmerism - A Practical and Scientific ApproachDocument102 pagesAnimal Magnetism and Mesmerism - A Practical and Scientific Approachparetmarco100% (12)

- George Wright - The Green Book, The Philosophy of Self (A Reconstruction)Document28 pagesGeorge Wright - The Green Book, The Philosophy of Self (A Reconstruction)Kenneth Anderson100% (5)

- Self Awareness and Filipino ValuesDocument6 pagesSelf Awareness and Filipino ValuesThe PsychoNo ratings yet

- Amig Module 2Document4 pagesAmig Module 2ROSEMAY FRANCISCO100% (1)

- Levine's Conservational Model PresentingDocument33 pagesLevine's Conservational Model PresentingSherly AmeliaNo ratings yet

- Sociology The Self From Various PerspectiveDocument21 pagesSociology The Self From Various PerspectiveJoevinz MasbateNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 - COMMUNICATION & GLOBALIZATIONDocument5 pagesChapter 2 - COMMUNICATION & GLOBALIZATIONRyna Janelle BrusolaNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Gr. 5 Life Skills PSW Term 1 Week 1 2Document5 pagesLesson Plan Gr. 5 Life Skills PSW Term 1 Week 1 2Raeesa S100% (1)

- Jean Watson (Transpersonal Caring Relationship)Document2 pagesJean Watson (Transpersonal Caring Relationship)KyNo ratings yet

- Sumptuous DesireDocument24 pagesSumptuous DesireGlenn WallisNo ratings yet

- Bayuca, Genovah Niña D. 10:30-12:00 (Tuesday) Bscriminology - IiDocument2 pagesBayuca, Genovah Niña D. 10:30-12:00 (Tuesday) Bscriminology - IiGenovah Niña BayucaNo ratings yet

- William James TheoryDocument2 pagesWilliam James Theorydevtiwari2003No ratings yet

- School Experience Reflection Journal 2Document6 pagesSchool Experience Reflection Journal 2api-272317458No ratings yet

- XAT 2020 Answer Key PDFDocument54 pagesXAT 2020 Answer Key PDFANANT PRAKASHNo ratings yet

- Social Behavior and InteractionDocument14 pagesSocial Behavior and InteractionVergelNo ratings yet

- 202 2017 2 Bpyc2601Document11 pages202 2017 2 Bpyc2601Phindile MkhizeNo ratings yet