Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Crypto-Jews in Mexico During The Seventeenth Century PDF

Crypto-Jews in Mexico During The Seventeenth Century PDF

Uploaded by

DavidJensenLópezCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5820)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Mackie - Heaven & Hell NotesDocument12 pagesMackie - Heaven & Hell NotesWilliam Sanjaya100% (4)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Lines of Credit, Ropes of BondageDocument30 pagesLines of Credit, Ropes of BondageJennifer Buhrle Hood100% (3)

- ANCIENT CIVILIZATIONS Active Reading and Note-Taking Guide G6Document214 pagesANCIENT CIVILIZATIONS Active Reading and Note-Taking Guide G6Roxana Soledad Marin Parra100% (9)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- 900+ Names & Titles of GodDocument38 pages900+ Names & Titles of GodRecuperatedbyJesus100% (2)

- The Correct Translation of John 8:58. List of Alternative Readings To "I Am."Document40 pagesThe Correct Translation of John 8:58. List of Alternative Readings To "I Am."Lesriv Spencer88% (8)

- Scripture Hebrew Name DictionaryDocument28 pagesScripture Hebrew Name Dictionarydaniel_vmcNo ratings yet

- DuodirectionalityDocument8 pagesDuodirectionalityapi-3735458No ratings yet

- Commentary On Genesis 9,8-17.howardDocument2 pagesCommentary On Genesis 9,8-17.howardgcr1974No ratings yet

- Exegetical Paper-The Prophet Joel - by Maria Grace, Ph.D.Document10 pagesExegetical Paper-The Prophet Joel - by Maria Grace, Ph.D.Monika-Maria GraceNo ratings yet

- Chukas Rabbi Baruch EpsteinDocument4 pagesChukas Rabbi Baruch EpsteinRabbi Benyomin HoffmanNo ratings yet

- Shoe Box ProjectDocument5 pagesShoe Box ProjectAndrea SavuNo ratings yet

- The Life and Times of The Old TestamentDocument410 pagesThe Life and Times of The Old TestamentborrcoNo ratings yet

- The Kabalistic CrossDocument4 pagesThe Kabalistic CrossStarChildPaulaNo ratings yet

- Baumgarten, Joseph M. The Book of Elkesai and Merkabah Mysticism,' Proceedings of The World Congress of Jewish Studies Vol. 8, Division C (1981), Pp. 13-18Document6 pagesBaumgarten, Joseph M. The Book of Elkesai and Merkabah Mysticism,' Proceedings of The World Congress of Jewish Studies Vol. 8, Division C (1981), Pp. 13-18yadatanNo ratings yet

- Society of Biblical Literature Publication NoticeDocument3 pagesSociety of Biblical Literature Publication NoticeDavid Vanlalnghaka SailoNo ratings yet

- Andrew Perriman Corporate PersonalityDocument23 pagesAndrew Perriman Corporate Personalityjhunma20002817No ratings yet

- 2 Corinthians 6-2 - Paul's Eschatological "Now" and Hermeneutical Invitation - by - Mark GignilliatDocument15 pages2 Corinthians 6-2 - Paul's Eschatological "Now" and Hermeneutical Invitation - by - Mark Gignilliatmarcus_bonifaceNo ratings yet

- Election in The Old Testament, Brown.Document13 pagesElection in The Old Testament, Brown.M. CamiloNo ratings yet

- Lesson 29 Retelling A Selection Listened ToDocument4 pagesLesson 29 Retelling A Selection Listened ToConnie Diaz CarmonaNo ratings yet

- Companions Promised ParadiseDocument36 pagesCompanions Promised Paradiseims@1988No ratings yet

- PsalmsDocument257 pagesPsalmsxal22950100% (1)

- Impact ReportDocument10 pagesImpact ReportEmilio CortésNo ratings yet

- 1 ST Quarter Report 09Document2 pages1 ST Quarter Report 09stevejursNo ratings yet

- Four Kingdoms of DanielDocument55 pagesFour Kingdoms of Danielkingkrome999No ratings yet

- Daf Ditty Eruvin 15:divorce As ParadigmDocument19 pagesDaf Ditty Eruvin 15:divorce As ParadigmJulian Ungar-SargonNo ratings yet

- Is Yahushua Really MessiahDocument26 pagesIs Yahushua Really MessiahDaniel Lemos100% (1)

- Church in TransylvaniaDocument17 pagesChurch in TransylvaniaTimothy Kitchen Jr.No ratings yet

- Importance of JerusalemDocument1 pageImportance of JerusalemMishkaat KhanNo ratings yet

- Som SekelDocument6 pagesSom SekelAngel SanchezNo ratings yet

- The Parable of The King-Judge LK 19 1228Document9 pagesThe Parable of The King-Judge LK 19 1228Jipa IustinNo ratings yet

Crypto-Jews in Mexico During The Seventeenth Century PDF

Crypto-Jews in Mexico During The Seventeenth Century PDF

Uploaded by

DavidJensenLópezOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Crypto-Jews in Mexico During The Seventeenth Century PDF

Crypto-Jews in Mexico During The Seventeenth Century PDF

Uploaded by

DavidJensenLópezCopyright:

Available Formats

Crypto-Jews in Mexico during the Seventeenth Century

Author(s): Arnold Wiznitzer

Source: American Jewish Historical Quarterly , JUNE, 1962, Vol. 51, No. 4 (JUNE, 1962),

pp. 222-231, 233-268, 322

Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23874312

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to American Jewish Historical Quarterly

This content downloaded from

87.77.195.98 on Mon, 28 Sep 2020 21:55:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Crypto-Jews in Mexico

during the Seventeenth Century

By Arnold Wiznitzer

INTRODUCTION

The beginning of the seventeenth century found only a

Judaizers in the prison of the Holy Office in Mexico

trying these prisoners, the Inquisitors prepared a specta

da-fe for March 25, 1601. One hundred and twenty-thre

indicted for bigamy, blasphemy, witchcraft, Lutheranism

and other crimes appeared in the presence of seven hund

men, the Viceroy of New Spain, and the general populatio

City. Among the victims were thirty-nine accused of Jud

Twenty-one of the latter group were accused for the f

These showed repentance, asked for mercy, and abjured th

errors. As reconciliados they were accepted into the Cat

As a result, instead of being condemned to death they wer

to confiscation of their possessions .and to variable prison

pulsion from New Spain, public lashing, or galley slaver

the mercy conceded to the penitents by the Inquisition.

Among the reconciliados was Dona Ana de Leon Carv

teen-year-old unmarried sister of the martyr Luis de Ca

had been executed in 1596.1

Among the Judaizers condemned to death were the following:

1. Dona Maria Nunez de Carvajal, another unmarried sister of

Luis de Carvajal, reconciled in 1596, was again imprisoned on the

charge of having relapsed into Judaism. Because she expressed a wish

to die as a Catholic, she was executed by the garrote [strangulation],

1 Cf. Luis Gonzdlez Obreg6n, Mexico viejo (Mexico D.F. 1959), p. 686. Cf. Jos£

Toribio Medina, Historia del Tribunal del Santo Oficio de la Inquisicidn

en Mexico (Mexico D.F., 1952), p. 160.

222 ]

This content downloaded from

87.77.195.98 on Mon, 28 Sep 2020 21:55:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CRYPTO-JEWS IN MEXICO: 17th CENTURY

and her body was immediately afterward burned at the stake. She

was twenty-nine-years old.2

2. Thomas de Fonseca Castellanos, a native of Portugal, had come

to Mexico from Holland. He became a miner in Taxco. Accused of

relapsing into Judaism and condemned to death, because he showed

a slight intention to die as a Catholic he was garroted and afterward

burned.3

3. Francisco Rodriguez de Ledesma was accused of Judaizing and

condemned to death. At the reading of his sentence at the auto-da-fe

he asked for a new hearing and made some confessions. Consequently

his execution was suspended, and he was returned to his cell. He

died in prison, and his body was burned on April 20, 1603.4

Fifteen of the accused crypto-Jews had already left Mexico or had

died. Their effigies were burned on March 25, 1601, and the bodies of

those who had died in Mexico were exhumed and burned at the

same time.5

Another auto-da-fe was celebrated on April 20, 1603. At this, Juan

Nunez de Leon was executed by garrote, while Dona Clara Enriquez

and Rodrigo del Campo were reconciled.6 A sick old man, Antonio

Gomez, was condemned to death for Judaizing, but he confessed at

the last moment and was returned to prison for further investigation.

At the March 25, 1605, auto-da-fe he appeared as reconciled.7

Diego Dias Nieto, born in Oporto, Portugal, had lived for some

time in Ferrara, Italy, where Jews could openly profess their faith.

In 1596, he was imprisoned in Mexico City as the result of a denuncia

tion. He served one year in prison and was again imprisoned in 1601.

He told the strange story that he had come to Mexico with a Bulla

of Pope Clement VIII and with a royal license to collect alms. Being

very learned in Judaism, he was able to discuss Bible passages and

2L. G. Obreg6n, op. cit., p. 690; J. T. Medina, op. cit., pp. 160-161. For the

garrote the condemned was placed with his back to a wooden pillar, his

neck tied to the pillar (stake) with a thick cord on which an iron tourniquet

was twisted, to strangle the condemned gradually. Cf. D. J. Garcia Icazbalceta,

Obras, vol. I (Mexico, 1896), chapter "Autos da F6 celebrados in Mexico,"

pp. 271-316.

3 L. G. Obreg6n, op. cit., p. 689; J. T. Medina, op. cit., p. 160.

4 J. T. Medina, op. cit., pp. 161, 162, 171; L. G. Obreg6n, op. cit., p. 690.

5 Ibid.

6 J. T. Medina, op. cit., p. 171. Juan Nunez de Leon is not mentioned in

Obreg<3n's list.

1 J. T. Medina, op. cit., p. 171; L. G. Obreg6n, op. cit., p. 691.

[223

This content downloaded from

87.77.195.98 on Mon, 28 Sep 2020 21:55:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

AMERICAN JEWISH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

their interpretations with the scholarly clergymen. He appeared as

reconciled during the auto-da-fe of March 25, 1605.8

Spain had been left virtually bankrupt at the death of Philip II

in 1598. Portugal had been under Spanish rule since 1580 and, in

1605, rich Portuguese New Christians succeeded in buying from King

Philip III a General Pardon for Judaizers of Portugese descent at

tha.t time indicted or imprisoned by the Holy Office in Spain, Portugal,

or the Colonies. For this they paid 2,925,000 cruzados. The king's

patent was dated February 1, 1605. When it reached Mexico, the only

Judaizer in prison was Francisco Lopez Enriquez, and he was set

free.9

As a consequence of the trials of 1590, 1596, and 1601, Mexican

Judaizers were ruined financially, imprisoned, expelled, or killed. The

remnants certainly exercised caution in their observation of Jewish

rites. During the subsequent thirty years only nine Judaizers were

accused at autos-da-fe. Seven of them were reconciled and two were

accused in absentia.10 At the April 12, 1635, auto-da-fe twelve Ju

daizers appeared as reconciled and two were in absentia.11 And in

the year 1638 one person was reconciled.12

The tapering off of persecutions in Mexico and the economic

prospects of the silver rush encouraged many Judaizers to migrate

to Mexico from 1606 to 1642. They were active in business, and

some became very wealthy. The Holy Office, seeking an opportunity

to fill its coffers, in 1642 created such an occasion.

One day a priest reported that his two servants had overheard in

the streets of Mexico City a conversation to the effect that certain

Portuguese intended to set the Inquisition buildings on fire. Immediate

ly a guard was placed around those buildings and an order was issued

that no Portuguese should be allowed to embark at the Port of

Vera Cruz.

The moment for the attack on the Portuguese was carefully chosen.

Two years earlier Portugal had regained her independence and had

crowned the Duke of Braganza as King John IV.

Portuguese all over the world, including Judaizers, were in sympathy

with Portugal and thus were considered enemies of Spain.

8 J. T. Medina, op. cit., p. 173.

9 Ibid., pp. 112, 174.

10 L. G. Obreg6n, op. cit., p. 691; J. T. Medina, op. cit., pp. 170-176.

11L. G. Obreg6n, op. cit., pp. 692-693; J. T. Medina, op. cit., pp. 184-185.

12 Ibid., p. 186.

224 ]

This content downloaded from

87.77.195.98 on Mon, 28 Sep 2020 21:55:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CRYPTO-JEWS IN MEXICO: 17th CENTURY

On July 13, 1642, the Mexican Holy Office started a new campaign

to exterminate the Judaizers by imprisoning forty of them. This move

made a great stir all over Mexico, with the general population

discussing the country's concern over the problem of the "perfidious

Hebrews." The Holy Office had to arrange for additional space when,

in a short time, more than a hundred and fifty prisoners were ap

prehended. Altogether, two hundred and sixteen Judaizers were

tried, some in prison and others absent by death or flight. Between

1646 and 1649, several autos-da-fe were held. The last one, celebrated

on April 11, 1649, was called the "Big One" [el auto grande].

On that occasion sixty-seven, who had either escaped in time or

had died outside of Mexico, were burned in effigy. The bodies

of those who had died in Mexico were exhumed and burned.

One "hundred and thirty-five of the accused were reconciliados who

were punished in the manner explained above.

Fourteen Judaizers were accused of being relapsed heretics, and

these perished as martyrs. One of them was burned alive, and

thirteen died by the garrote. Here is a report of the fourteen trials,

based on the accounts \relaciones del auto-da-fe] published under

the auspices of the Holy Office in Mexico, on manuscripts and on

other printed sources, which give an insight into social, economic, and

religious conditions of the Judaizers of that time.13

1. Dona Ana de Leon Carvajal was a daughter of Francisco Ro

driguez de Mattos and Dona Francisca Nunez de Carvajal, a sister

of the martyr Luis de Carvajal. In 1601, at the age of nineteen, she

had been reconciled. A widow of Cristobal Miguel, she was very

religious, observed holy days and fast days, prayed unceasingly, and

was known among fellow Judaizers as a Santa [saint]. Even in prison

she was heard to pray, repeating the word Adonai. She denied all

accusations and did not denounce anybody. As the last survivor of

the Carvajal family, at the age of sixty-seven she was garroted and

her body afterward burned at the stake.

13 The sources are Relation sumaria del Auto particular de Fee... Ano de

1646. Reprinted in Genaro Garcia y Carlos Pereyra, "Docuraentos in£ditos

o muy raros para la Historia de Mexico," vol. XXVIII, p. 94; Breve y

Sumaria Relation de un Auto particular Mexico, 1647. Reprinted in

"Documentos incditos," vol. XXVIII, pp. 95-132; Relation del Tercero Auto

Particular de Fee... treinta del mes de Marzo de 1648 (Mexico, 1648). Re

printed in "Documentos incditos," vol. XXVIII, pp. 133-269, also in Museo

Mexicano, tomo I, pp. 387 ff. (Mexico, 1943); Auto General de la Fee, Cele

brado... en la Ciudad de Mexico... 11 de Abril, 1649 (Mexico, 1649).

Cf. also Obreg<5n, op. cit., pp. 693-709, and J. T. Medina, op. tit., pp. 111

120 and pp. 189-208.

[225

This content downloaded from

87.77.195.98 on Mon, 28 Sep 2020 21:55:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

AMERICAN JEWISH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

2. Francisco Lopez Blandon (alias Ferrasas) was born in 1619,

son of Dona Leonor Nunez, and became a goldsmith in Mexico.

Having been reconciled in 1635, he was subsequently imprisoned again

on the charge of Judaizing. Blandon belonged to a family of well

known Judaizers and was a brother-in-law of Thomas Trebino de

Sobremonte. He was specifically accused of having circumcised his

little son born of a mulatto mother. Even in prison he was seen praying

on his knees and fasting. He did not admit anything, nor did he

denounce anybody during his trial. He was executed by garrote and

later his body was burned at the stake.

3. Gonzalo Flores (alias Gonzales Vaez Mendez) was born in 1605

in La Torre de Moncorbo, Portugal, and was given the Hebrew

name of Samuel. In Mexico he was a merchant. During his three

years in prison, he consistently denied that he was a Judaizer, but

later admitted it. Gonzalo behaved like an insane person, but during

his incarceration in an asylum the doctors declared he was completely

sane and responsible. He was executed by garrote and his body was

burned at the stake.

4. Ana Gomez, born in Madrid in 1606, was a daughter of Leonor

Nunez and Diego Fernando Cardado, a descendant of a family of

martyrs. While in prison she often claimed that she wished to die as

a martyr of the Jewish faith. She was executed by strangulation and

her body was burned at the stake.

5. Maria Gomez, born in Madrid in 1617, was a sister of Ana

Gomez and was married to Thomas Trebino de Sobremonte. Having

been reconciled in 1625, she was this time condemned for relapsing

in Judaism. She was executed by strangulation, and her body was

burned at the stake on the same day as her mother, Leonor Gomez

Nunez, her sister Ana, and her husband Sobremonte were similarly

executed.

6. Duarte de Leon Jaramillo, a businessman in Mexico, born in

1596 at Casteloblanco, Portugal, was the husband of Isabel Nunez.

The Inquisition had always shadowed him. First imprisoned in 1628,

his trial was suspended. In 1635 he was reconciled to Catholicism

and later imprisoned again as a relapsed Judaizer because he had

instructed his three sons, Francisco de Leon Jamarillo, Simon de

Leon, Iorge Duarte (alias Iorge de Leon), and his three daughters,

Clara Nunez, Antonia Nunez, and Ana Nunez, in the observation

of the Jewish rites. He was known to have been very severe with his

children. It was claimed that he had beaten them whenever he heard

226 ]

This content downloaded from

87.77.195.98 on Mon, 28 Sep 2020 21:55:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CRYPTO-JEWS IN MEXICO: 17th CENTURY

them pray to the Holy Virgin Maria but to have treated them well

from the moment they began to Judaize. He circumcised his son,

Francisco de Leon. During the hearings his imprisoned daughters

testified that he had performed a small operation on them when he

initiated them into Judaism: He cut a piece of flesh from the left

shoulder of each, roasted it, and ate it. The Tribunal accepted this

fantastic story as an example of Jewish cannibalism. Padre Mathias

de Bocanegra, who wrote the published report of the auto-da-fe,

decided that this was a newly revealed method of circumcision and

called Jamarillo "the inhuman Jew." His children further deposed

that Jamarillo had often fasted in penance for having broken his vow

to migrate to a country where Jews could freely practice their religion.

They declared that on Friday evenings he and his wife and many

other Jews locked themselves in a warehouse where they uttered

shouts of joy. Jamarillo did not confess to anything, and at the

auto-da-fe of April 11, 1649, he was condemned to death. He was

executed by garrote and on the same day his body was burned at

the stake.

7. Simon Montero, born in 1600 in Casteloblanco, Portugal, was

a businessman and was married in Seville to Dona Elena Montero.

Before migrating to Mexico, he visited Jewish communities in France,

Rome, Livorno, and Pisa, studying to be a rabbi and teacher of

dogma. In Mexico, he was seen to pray with other Judaizers while

wearing "tunicas judaicas con sus cucuruchos en las Cabezas" [prayer

shawl and phylacteries]. He was first imprisoned in 1635 as the

result of a denunciation, on a charge that he had tried to buy a

fresh grave for one of his friends. He denied everything when under

torture and was set free. Again imprisoned and tried, he was con

demned to death. During the auto of April 11, 1649, he was executed

by garrote and his body was burned at the stake.

8. Leonor Gomez Nunez, born in Madrid in 1585, was the daughter

of Gaspar Fernandes of Portugal. She was married three times. Her

first husband was Fernando Cardado, and the children of this mar

riage were Ana Gomez and Isabel Nunez. Her second husband was

Pedro Lopez (alias Simon Fernandez), and the children of this mar

riage were Francisco Lopez Blandon and Maria Gomez (wife of

Sobremonte). Her third husband was Francisco Nieto. Leonor Gomez

Nunez was a devoted Jewess and instructed her children accordingly.

9. Simon Rodriguez Nunez, born in Portugal, had come to Mexico

from Seville. He was accused of relapsing into Judaism and appeared

[227

This content downloaded from

87.77.195.98 on Mon, 28 Sep 2020 21:55:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

AMERICAN JEWISH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

at the auto of January 23, 1647, and was c6ndemned to death. He

was executed the following day, by being first garroted and then

burned at the stake.

10. Dona Catalina de Silva (alias Enriquez) was born in Seville in

1601. She was the wife of Diego Tinoco and sister of Antonio Rodri

gues Arias and Blanca Enriquez, all of whom were tried by the In

quisition. She practiced Jewish rites and taught her children, Pedro

and Isabel Tinoco, their observance. In Church, she was in the habit

of covering her face with a handkerchef in order to avoid seeing the

host and the chalice. In prison she fasted regularly and did not confess

anything and did not ask for mercy. On April 11, 1649, she appeared

at the auto-da-fe as condemned. On the insistence of her children

she asked for mercy at the last moment. Because of this she was

executed by garrote, and her body was burned at the stake.

11. Isabel Tristan, born in Seville in 1599, was the daughter of

Simon Lopez, a Portuguese, and married to her uncle, Luis Fernandez

Tristan. She was a pious Jewess and was accused of having invited

other Judaizers to spend Jewish fast days in her home, where she

served them appropriate meals at the completion of the fast. She

appeared at the April 11, 1649, auto-da-fe as condemned and was

executed the same day by garrote, and her body was burned at the

stake.

12. Antonio Vaez (alias Tirado, also called Captain de Castelo

blanco) was born in Portugal in 1574, a brother of the famous

Judaizer Simon Vaez Sevilla. In 1625, Antonio appeared for the first

time at an auto in Mexico and was reconciled to Catholicism. He

boasted that he had not denounced anybody. Immediately after his

liberation, he resumed the practice of Judaism and also instructed

other New Christians in Judaism at the home of his brother Simon.

Antonio told people that he was a descendant of the priestly tribe of

Levi. Before couples went to their weddings in the Church, he married

them at home in conformity with Jewish custom. He was often asked

to visit the sick, when he would lay hands on the ailing part of the

body, praying to Adonai Sabaot. Many of those whom he instructed

in Judaism were invited to participate in the Seder [home service on

Passover eve] in his house and to partake of the Passover meal of

lamb and mazzot [unleavened bread]. In 1640, he disagreed with

Sobremonte concerning the exact date of Yom Kippur—as to whether

the Judaizers in Mexico should fast during one week or another.

While in prison, in 1625, he had circumcised Sobremonte. When the

228]

This content downloaded from

87.77.195.98 on Mon, 28 Sep 2020 21:55:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CRYPTO-JEWS IN MEXICO: 17th CENTURY

wave of arrests began in 1642 Antonio Vaez admonished his friends

to confess to nothing and to denounce no one. During his own trial

he behaved accordingly. Called by Padre Bocanegra "the priest of

the Jews in this part of the Kingdom," he appeared at the April 11,

1649, auto-da-fe and was condemned. He was garroted and his body

was burned at the stake.

13. Gonzalo Vaez was born in 1602 at Casteloblanco, Portugal. He

was a traveling salesman in the interior of Mexico. He was related

as a nephew or cousin to most of the Judaizers in Mexico. Imprisoned

and accused of practicing and propagating Judaism, he first admitted

everything but later recanted. He also simulated insanity, but the

doctors declared him responsible. On April 11, 1649, he appeared at

the auto-da-fe, was condemned and, on the same day, was garroted,

and his body was burned at the stake.

All these thirteen martyrs had practiced and propagated Judaism

in Mexico knowing well the risk involved. As courageous and as

strong as some of them were during the torturing by the Inquisition,

they could not face being burned alive. That is the reason they

appeared in the autos-da-fe procession carrying a green cross, agreeing

to say a paternoster or to kiss a crucifix, sometimes at the last moment,

and thereby were executed through strangulation, with their bodies

being burned immediately afterward.

II

THOMAS TREBINO DE SOBREMONTE

Sobremonte was arrested by the Inquisition for the first tim

March 1, 1624, and removed from Antequera, Mexico, to M

City on November 23, 1624.14 During his hearings he vouchsaf

following biographical details.

14 The manuscripts of the Sobremonte trials (1625 and 1649) are fo

the Archivo General de la Nation in Mexico City, vol. 1495. Photocop

Sobremonte's signature and the sentences of the ecclesiastical and

authorities have been obtained. The complete trials have been publis

the original Spanish in Boletin del Archivo General de la Nacidn,

(Mexico City, 1935), pp. 99-148, 305-308, 420-464 and 578-620; vol

(Mexico City, 1936), pp. 88-142, 757-777; vol. VIII (Mexico City, 193

1-172. There exists an English translation of the trials in the Library

Cambridge University, England. Cf. J. Street, "The G. R. G. Collection

Cambridge University Library: A Checklist," in the Hispanic Ame

Historical Review, vol. XXXVII, no. 1, February, 1957, pp. 60-82.

[229

This content downloaded from

87.77.195.98 on Mon, 28 Sep 2020 21:55:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

AMERICAN JEWISH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

He was born in the town of Medina de Rioseco in Castile, Spain.

At the death of his father, Antonio, his mother, Dona Leonor Martinez

de Villagomez, as he was told, was imprisoned by the Holy Office in

Valladolid and died there. His brother Francisco was in Peru and his

brother Jeronimo in Valladolid. His ancestors on his father's side had

been Old Christians and noblemen [hidalgos]: De Sobremontes. He

himself was baptized at birth and confirmed at the age of seven

or eight.

Sobremonte correctly recited the paternoster and other Catholic

prayers.15 He knew how to read and write in his own language and

in Latin because he had attended the College of the Jesuits in Valencia,

Spain, for one year and had studied canonical law at the University

of Salamanca. He was appointed page of Don Rodrigo Enriquez

de Mendoza in Medina de Rioseco. One day another page in the same

service called him "Jew" and in anger Sobremonte killed him. Be

cause of this he went into hiding in a neighboring convent and

changed his name to Jeronimo de Represa. In the year 1612, he

sailed from Cadiz to Mexico and settled as a trader in the town of

Guaxaca.

Accused by the Inquisitors of being a Judaizer, Sobremonte averred

that when he was about fourteen years old his mother explained to

him that Christians adore figures of wood and metal, while Jews

adore Adonai who gave the true law to Moses in the desert; that in

order to obtain salvation (deliverance from sin and eternal damnation)

he would have to believe in Adonai, the God of the Jews. Under this

influence he accepted Adonai and the Law of Moses.

His mother had instructed him to keep his Judaism secret in order

not to endanger their lives. She taught him several prayers but did

not allow him to write them down. In broken Hebrew he recited:

Sema, Adonai, Beruto, Ceolan, Banel [obviously the Shema

prayer: "Shema Israel Adonai Elohenu Adonai Ehad. Baruch

Shem Kevod Malchuto leolam Vaed"].

He further quoted a prayer which started with the defective Hebrew

words:

Binuam, Adonai, Maciadeno, [continuing in Spanish: ] debajo

o a sombra del abastado me adormezo, debajo, o so tu alias

15 The Court usually examined the accused Judaizers, asking them to recite

the Paternoster, Ave Maria, Credo y Salve, and the Doctrina. Cf. Nicolas

Lopez Martinez, Los Judaizantes Castellanos y la Inquisicidn en Tiempo de

Isabel la Catdlica (Burgos, 1954), p. 327.

230]

This content downloaded from

87.77.195.98 on Mon, 28 Sep 2020 21:55:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

jut ^

®*q»ariille.

**)SeLLO OVARTO, VN QVARTlLfcO,

(MA^OS DEMI L YSI^SCIENTOS YQV A

^ REMTA YSIETE , TQVARENTA^O

e&?rnf$v?>?■ 'ffl

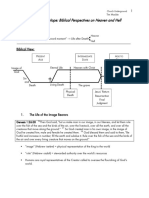

THOMAS TREMINO [TREBINO] DE SOBREMONTE IS SENTENCED TO

BE BURNED ALIVE [Quemado vivo]

[From the original manuscript of the trial, Volume 1495, in the

Archivo General de la Nacidn, Mexico City]

This content downloaded from

87.77.195.98 on Mon, 28 Sep 2020 21:55:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CRYPTO-JEWS IN MEXICO: 17th CENTURY

sede alumbrado y enderezado a tu servicio, no temere, el

pavor de la noche, y asi mismo decia, Adarja y escudo, y

tambien no llegara a ti malicia, ni llaga que tralla dice en

la prea de tu mano.16

Sobremonte then went on to explain that his mother had owned

a notebook entitled "Los Siete Salmos Penitenciales" [the Seven Peni

tential Psalms] including psalms in her own handwriting. On the day

before Yom Kippur the whole family assembled, took baths, and put

on fresh linen, and ate fish. The same evening all prayed together

while standing until two in the morning, and they also discussed the

Law of Moses. They fasted a day and a night, then dined on fishmeal.

Sobremonte confessed that one day while on a business trip in

Rio Hondo, Mexico, he had behaved dishonestly [deshonesto] with

an Indian girl named Juana. When he returned to Rio Hondo a year

and a half later he was told that Juana was the mother of twins, but

he was not sure whether he was their father. He also admitted

having had intercourse with Dona Luisa de Bilona, the wife of Don

Alonso de Carriage. She too became pregnant and could not abort

the child.

During renewed interrogations about his mother's teachings, Sobre

monte deposed that the family rested on Shabbat [the Jewish Sabbath]

but sometimes had to eat pork in order not to attract attention. He

was taught to wash his hands before each meal and to pray:

Bendito sea el Poderoso Adonai, que en las enseiianzas me

ensenaste el lavar de las manos, boca y ojos te alabrar y

servir en loor y honra del Senor y en la Ley de Moisen

[Blessed be the Almighty Adonai, who taught me in his teach

ings to wash hands, mouth, and eyes in order to glorify and

serve in praise and honor of the Lord and the Law of

Moses] .17

Sobremonte told the Court that he relented of having followed his

mother's instructions and was willing to return to Catholicism. Even

so, on February 1, 1625, the Promoter Fiscal [Ecclesiastic Attorney

General] demanded capital punishment for him. The Court con

demned him to appear at the March 25th auto-da-fe as a reconciled

Catholic wearing the sambenito [penitential garment]. He was also

sentenced to one year in prison and to confiscation of all his belongings.

io Cf. Boletin mentioned above, vol. VI, pp. 426-427.

it Ibid., p. 435.

[233

This content downloaded from

87.77.195.98 on Mon, 28 Sep 2020 21:55:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

AMERICAN JEWISH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

Besides, he was required to assist every Sunday and on holy days at

High Mass and to attend the sermons in the Convent of the Dominican

friars.

How serious Sobremonte's repentance was can be learned from

subsequent events. On November 29, 1624, complying with his request,

the Court assigned him a cell mate. This companion was Antonio

Vaez, who circumcised Sobremonte during his incarceration in the

prison cell.

After his first condemnation, Sobremonte became seriously ill in the

damp cell and was transferred to the hospital for paupers, where he

was detained for four months. He was set free on June 16, 1626. He

then resumed his business and was successful.

On June 20, 1629, he was again denounced to the Inquisitors by

the Attorney General because he was seen horseback riding, publicly

wearing arms, and dressed in silk and fine clothes—conduct as such

was forbidden to persons reconciled by the Tribunals of the Holy

Office. On July 16, 1629, several witnesses confirmed the denuncia

tion. On February 26, 1630, a member of the Holy Office deposed

that he had seen Sobremonte elegantly dressed and wearing a sword.

Despite all this, Sobremonte was not imprisoned; however, he was

frightened. In 1633, he wrote to the Holy Office offering one hundred

pesos as a voluntary fine for delaying to present his rehabilitation

document dated May 6, 1631, in Madrid, and signed by the Cardinal

and General Inquisitor of Spain, Don Antonio Zapata. According to

this document Sobremonte was entitled to wear arms and expensive

clothes, to ride a horse, and to enjoy other privileges usually forbidden

to the reconciliados. Inquisitors everywhere were expected to respect

this Royal Decree. On April 23, 1633, the Inquisitors in Mexico

acquiesced to this document and accepted the one hundred pesos

offered by Sobremonte, and decided to use the money for repairs on

the Holy Office's building.

Sobremonte was then left in peace by the Inquisition until 1644.

Then the Attorney General denounced him on the ground that, since

his reconciliation in 1625, he had been practicing Judaism. Informa

tion had been obtained that Sobremonte intended to sail from Acapulco

to the Philippines, from where it would be easy for him to escape to

Portuguese India. Consequently, Sobremonte was imprisoned again on

October 11, 1644.

At his hearing on November 11, 1644, he deposed that the name

of his grandfather was Pedro de Sobremonte, and that the name of

234]

This content downloaded from

87.77.195.98 on Mon, 28 Sep 2020 21:55:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CRYPTO-JEWS IN MEXICO: 17th CENTURY

his grandmother was Maria Garcia Tremino. One year after his

reconciliation, in 1626, he had married Dona Maria Gomez, the

daughter of Leonor Nunez and Pedro Lopez. By 1644, he had five

children: Rafael, Leonor, Micaela, Gabriel, and Salvador, their ages

ranging from one and a half month to thirteen years. One son,

Antonio, had died. From 1626 to 1632, he had lived in Guadalajara,

and, since 1632, in Mexico City. He was a businessman and often

traveled to Acapulco, Vera Cruz, Zacatecas, and Guadalajara.

Sobremonte did not confess to anything and did not denounce any

body, but many witnesses testified against him. Dona Margarita de

Rivera told the Inquisitors about his 1624 circumcision by his cell

mate, Antonio Vaez. Four surgeons examined him and verified signs

of circumcision. Rafael Sobremonte, his son, told the Inquisitors that

his father had instructed him in Judaism, first telling him that all the

Christians believed was nonsense [pat ar at a], that God has no mother,

and that they adored wooden images painted as saints. He was taught

to believe in One God. who had created heaven and earth. They fasted

every Thursday and his father once struck him when he was caught

eating on a Thursday. He stated also that his father circumcised him

when he was about thirteen years old and taught him to pray daily

upon awakening as follows:

Bendita sea la luz del dia, y el Senor que nos lo envia. Alabad

al Senor todas las gentes; Alabad al Senor todos los pueblos.

Porque ha confrmado sobre nosotros, y la verdad del Senor

permanecera para siempre. [Blessed be the light of the day

and the Lord who sends it out. All peoples praise the Lord,

all nations praise the Lord, because he has supported us. And

the truth of the Lord remains forever.]18

Many witnesses claimed that when Sobremonte married Maria

Gomez, he celebrated the marriage in conformity with Jewish customs;

that he and his family endeavored to eat kasher in accordance with

Jewish dietary laws; that he recited psalms in Latin while his head

was covered with a cap [montera']; that the crypto-Jewish com

munity in Mexico considered him as a clergyman-rabbi [sacerdote

rabino]; that he calculated the dates of holy days and fast days in

conformity with the Jewish calendar; that in the year 1640 he had

a long discussion with Antonio Vaez concerning the date of Yom

Kippur [because an error had been made in observing the appearance

of the new moon] as to whether the fast day that year was one week

18 Ibid., vol. VIII, p. 41.

[235

This content downloaded from

87.77.195.98 on Mon, 28 Sep 2020 21:55:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

AMERICAN JEWISH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

earlier or later; that he and his family in that year fasted for eight

days in order not to miss the day of Atonement;19 that he prayed

three times a day and sometimes even at midnight—always with his

head covered and a towel tied to the cap for drying his hands after

washing; that his family attended Mass and made confession in the

Church only to deceive neighbors and authorities, but whenever they

did so they fasted previously at home and knelt to ask God to forgive

them for this sin.

Other witnesses testified concerning the wealth of Sobremonte,

claiming that he had buried a few thousand pesos just before his

trial in 1624; that he had always planned to take his family to

Flanders, where they could live freely as professing Jews; that he had

even made a vow to do so and that as long as he did not fulfill this

vow he punished himself by regularly fasting twice a week.

Sobremonte denied everything that he was accused of during this

second trial. Orally and in writing he protested that the depositions

of his son Rafael and all the other witnesses were pure inventions,

especially accusing Margarita de Rivera of having a treacherous

tongue. The trial continued for five years. Sobremonte often fasted

in prison, and he became emaciated. On February 21, 1649, the

Tribunal condemned him to capital punishment.20 He was required

to appear at the auto-da-fe of April 11, 1649, to be burned alive at

the stake. -

The evening before that auto-da-fe, on April 10, 1649, Sobremonte

was visited in his cell by three clergymen who tried to convert him to

Catholicism before his death. One of them, Licenciado Francisco

Corchero Correno, wrote a report covering the twenty-four hours spent

with Sobremonte, and this report, attached to the trial manuscript,

was dated April 17th [six days after the execution]. It relates that

Correno and the padres Master Fr. Lorenzo Macdonald and Fr.

Miguel de Leon, both Dominicans, were chosen to assist Sobremonte

during his last twenty-four hours; that they admonished him to prepare

himself to die as a Catholic; that Sobremonte became terribly irritated

and, when he was asked to kiss a crucifix, he turned his face away

and started to blaspheme Christianity, declaring that he was a Jew

and wished to die as a Jew. The. three clergymen tried all night to

convert him, arguing without success. At five A.M., the time to

leave the prison for the auto-da-fe procession, Sobremonte told his

i# Ibid., vol. VII, p. 128.

20 See photograph on p. 230.

236]

This content downloaded from

87.77.195.98 on Mon, 28 Sep 2020 21:55:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CRYPTO-JEWS IN MEXICO: 17th CENTURY

visitors that they should convert themselves to Judaism, because his

God was the true one. Moreover, they asserted:

No solo ya se contentaba esta bestia con confesar su muerta

Ley de Moises, pero su descaro llego a que decia a voces

que la siguiesemos porque su dios era el verdadero. [This

beast was not satisfied to confess his dead Law of Moses, but

his impudence reached the point of screaming that we should

follow his God because he was the true one.]

During the procession to the plaza where the auto-da-fe was to be

celebrated, Sobremonte was accompanied by the three clergymen who

continued to plead with him for a last-minute conversion. The masses

on the streets, says Correno—men, women, and children—begged

Sobremonte "with Christian piety," while they were crying aloud and

reciting the Credo and other prayers, to accept Catholicism before

his execution.

When Sobremonte arrived on the stage of the auto-da-fe, priests

of all orders tried to persuade him. Though he had been fasting for

four days, he refused the food and drink offered him. Correno ex

plained chapter 9 of Daniel to him, in which the appearance of a

Messiah was prophesied, and showed him several other Bible passages.

Finally Sobremonte answered:

Do not exert yourself to convince me, for I must die as a

Jew. It would be better to convert yourself to Judaism.

Because of the blasphemies Sobremonte had uttered, he was gagged.

When other condemned Judaizers were brought upon the stage,

Sobremonte tried to give them signs with his eyes that they should

remain firm and die as Jews. When his mother-in-law, Leonor Gomez

Nunez, her daughter Maria Gomez [Sobremonte's wife], and her

other daughter, Ana Gomez, all condemned to death, appeared on

the stage, Sobremonte [obviously not gagged at that time] said:

Remember the mother of the Maccabeans!

When his sentence was read he said that he believed only in the God

of Israel. ("Como si nosotros lo negaramos" [as if we others would

deny him], adds Correno.)

After Sobremonte was declared relajado and released to the civil

authorities for punishment, Correno accompanied him to the stage

where General Don Jeronimo de Banuelos, Corregidor of Mexico

City, was performing his duties. This official condemned all other

[ 237

This content downloaded from

87.77.195.98 on Mon, 28 Sep 2020 21:55:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

AMERICAN JEWISH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

relajados to be garroted and burned after death. Only Thomas Tre

bino de Sobremonte was condemned to be burned alive.

Following the other relajados who had to ride on pack animals

through the streets of Mexico City from the stage of the auto-da-fe

to the square selected for the burning, Sobremonte (the "perfidious")

tried to mount a mule. But the mule, otherwise docile, refused to let

him mount, leaping and jerking. Other mules acted in the same way.

Finally Sobremonte was put on a mule with an Indian behind him to

keep him in the saddle. During this ride even, the Indian tried to

persuade Sobremonte to accept Catholicism.

The public on the streets along the way to the Quemadero was

inflamed against Sobremonte and would have lynched him many

times [muchas veces], says Correno, if he had not intervened, expect

ing that Sobremonte would show some sign of repentance at the last

moment.

When Sobremonte was tied to the stake, the clergymen who sur

rounded him and also the public made continuous exhortations. When

he was set on fire the clergymen begged him to make some sign of

accepting Christianity (since this would have still saved him from

being burned alive). But brave Sobremonte, not surrendering, asked

in a loud voice that they should finish burning him. The report

concludes:

Irritados los soldados, sacaron las espadas y dandole muchos

golpes y los verdugos soplando el fuego y echando de abajo

los hombres, mujeres y muchachos, la lefia, tnuriS entre las

llamas, empezando a sentir su maldito cuerpo el fuego que

su descomulgada alma estea y estara sintiendo en el infierno.

[The soldiers, irritated, drew their swords and gave him

many blows while the executioners fanned the fire and men,

women and children threw the wood into the burning flames,

and his cursed body began to feel the fire which his excom

municated soul is feeling and will feel in hell.]21

In Mexico City, the Quemadero [the burning place], in 1649, was

situated in front of the still existing building of the Convent of San

Diego [to the west of the Alemada passageway], on a plaza then

called Tianguis de San Hipolito [Saint Hippolyte market square].

Besides the report by Correno there is a description of Sobremonte's

execution in the booklet printed in Mexico City in 1649 covering that

April 11th auto-da-fe. It explains that Sobremonte's neck and hands

21 Ibid., vol. VIII, pp. 154-158.

238 ]

This content downloaded from

87.77.195.98 on Mon, 28 Sep 2020 21:55:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CRYPTO-JEWS IN MEXICO: 17th CENTURY

were tied to the stake before the burning began. Everybody hoped

that, when he saw the other thirteen executed by strangulation and

later burning, he would become frightened and say something that

would cause him to die as a Christian and save himself from being

burned alive.22 The semi-official narrative closes with the statement

that the following day at noon the flames were still burning. The

Corregidor ordered that the ashes be assembled in carts and thrown

into a canal behind the San Diego Convent.23

In none of the seventeenth century manuscripts or printed docu

ments is there any trace of the claim that Sobremonte at the last

moment with his feet drew the burning coals toward his body ex

claiming :

Echen Una, que mi dinero me cuesta [Throw in wood; I pay

for it anyway] ,24

The Mexico City house where Sobremonte had lived could still be

seen at the end of the nineteenth century and was shown as "La Casa

del Judio" [the Jew's house].25

Ill

OTHER INTERESTING VICTIMS OF THE AUTOS-DA-FE CELEBRATED

IN THE YEARS 1646 TO 1649

Besides the fourteen crypto-Jews who were burned at the stake

there were, as mentioned earlier, hundreds of accused Judaizers who

were reconciled during the autos-da-fe of the years 1646, 1647, 1648,

and 1649. Of these, we shall here discuss the most interesting trials.

22 Don Gregorio Martin de Guijo, "Diario de Sucesos Notables" (1648-1664),

in Documentos para la Historia de Mixico, vol. I (Mexico, 1863). He calls

Sobremonte: Tom is Tremino de Campos.

23 L. G. Obreg6n, op. cit., p. 246. "The victim, almost suffocated, but without

heaving a scream, or a sigh, or the slightest complaint, contented himself

to exclaim remembering his confiscated fortune and drawing with his feet

the burning coal (Echen lefia, que mi dinero me cuesta)." Obreg6n's un

verified story was repeated but not quoted in Cecil Roth's account that

Sobremonte's last audible words were, "Pile on the wood! How much money

it costs me!" See A History of the Marranos (Philadelphia, 1947), p. 163.

It was also repeated in Dr. George Alexander Kohut's statement that Sobre

monte exclaimed amid the flames, "That's right—burn wood, pile it thick

and fast; it costs you nothing; the fire is built with my money," see PAJHS,

vol. XI, pp. 179, "Trial of Pedro Arias Maldonado."

24 De Guijo, Diario de Sucesos Notables, op. cit.

25 Cf. photo of the house in L. G. Obreg6n, op. cit., p. 243, and in D. Vicente

Riva Palacio, Mexico a traves de los Siglos (Barcelona), vol. II, p. 425.

[239

This content downloaded from

87.77.195.98 on Mon, 28 Sep 2020 21:55:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

AMERICAN JEWISH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

Esperanza Rodrigues, a mulatto woman, born in Seville, Spain, in

1582, was the daughter of the Negro, Isabel, of Guinea, Africa, and

the New Christian, Francisco Rodrigues. She married a German

sculptor by the name of Juan Francisco del Bosque, and bore him

three daughters: Maria Rodrigues del Bosque, Isabel Rodrigues del

Bosque, and Juana Rodrigues del Bosque, the last marrying the Portu

guese Judaizer, Bias Lopez. The mother and the three daughters

admitted Judaizing and asked for mercy. They were reconciled to

Catholicism during the auto-da-fe of April 16, 1646.26

Manuel Carrasco, a native of Villa Flor, Portugal, at this time

twenty-six years old, was the manager of a sugar storehouse in Valle

das Amilpas. He was accustomed to wearing in a bag on his chest

a piece of mazzah [unleavened bread] as a relic brought from a seder

in Madrid. He used it as a remedy for sick people. He was reconciled

to Catholicism in 1646.27

Captain Francisco Gomez Tejoso Tristan, a fifty-eight-year-old

bachelor, born in Valencia del Cid, Spain, and circumcised, captain

of infantry in Vera Cruz, son of Pedro Gomez Tejoso Tristan of

Lisbon, averred that his grandfather on his mother's side had been

baptized in order to avoid persecution. Being very sad \triste~\ because

of that, he adopted the name Tristan, which all his descendants used.

Tejoso was reconciled in 1646.28

Rafael and Gabriel Granada were the sons of Manuel de Granada

and Dona Maria de Rivera. They testified that their mother had

instructed them in Judaism when they were thirteen years old. Fast

days were observed in their home, and after fasting they ate eggs,

fish and vegetables. Gabriel told the court that it was the custom

to put some grains of seed pearls into the mouth of a deceased person.

His aunt Margarita de Rivera spoke about the "Virgin and her son"

with contempt and confided to him that she used to lash a crucifix.

While Gabriel was in prison he was visited by five surgeons who, in

the presence of an officer of the court and a jailor, separately exa

mined him to see if he had been circumcised. They found signs of

circumcision. Both brothers showed repentance, asked for mercy, and

became reconciled to Catholicism in 1646. In the sentence, the court

26 Genaro Garcia, Documentos iniditos, op. cit., vol. XXVIII, pp. 47-48; L. G.

Obreg<5n, op. cit., p. 698; J. T. Medina, op. cit., pp. 114 and 193.

27 Genaro Garcia, op. cit., pp. 72-73; L. G. Obreg6n, op. cit., p. 701; J. T. Medina,

op. cit., p. 193.

28 Genaro Garcia, op. cit., pp. 51-52; L. G. Obreg6n, op. cit., p. 695; Historia,

pp. 114, 193,

240]

This content downloaded from

87.77.195.98 on Mon, 28 Sep 2020 21:55:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CRYPTO-JEWS IN MEXICO: 17th CENTURY

quoted from the Bible that "God desires not the death of the sinner

but that he should be converted and live."29

Margarita de Morera, the thirty-six-year-old wife of Pedro de

Castro, had once in Mexico City witnessed the public lashing of a

condemned Judaizer and had freely manifested her pity for the

sufferer. When an Old Christian once asked her how the Judaizers

knew when to congregate for their ceremonies, she said the signal

was the beating of a drum by a little Negro boy gaily dressed and

going through the streets. She appeared at the 1646 auto as re

conciled.30

Manuel Rodriguez Nunez, thirty-four years old, born in Castelo

blanco, was unemployed and therefore in the documents was called

an idle vagrant \yagamundo~\. In fear of the Inquisition, he had

changed his name to Manuel Mendez (alias Manuel Diaz) and lived

in the suburbs of Mexico City. He told the Inquisitors that in the

year 1640 there was a great dispute among the secret Jews in Mexico

concerning the exact day of Yom Kippur—as to whether it occurred

eight days sooner or later in conformity with the Christian calendar.

He added that each of the two groups followed the decision of the

leader and fasted on different days.31

Margarita de Rivera, born in Seville, was the thirty-three-year-old

daughter of Blanco de Rivera. She was a dollmaker and was married

to Miguel Nunez de Huerta. She was a great faster, and she was

accustomed to participating at the washing of corpses and in perform

ing other ceremonies for the dead. Whenever she had a bad dream

she went to confession so as to transfer the bad omen to the priest

[por echar el mal aguero en el confessor]. She used to say that

Judaizers who married Old Christians would go to hell. She was

reconciled in the year 1646.32

Gaspar Vaez Sevilla was the twenty-eight-year-old son of the

wealthy and very pious Judaizer, Simon Vaez Sevilla, and of Dona

Juana Enriquez. While his mother was carrying him, the Mexican

Judaizers expected that he would be born the Messiah of the Jews,

29 Genaro Garcia, op. cit., vol. XXVIII, pp. 54, 82, 83; L. G. Obreg6n, op. tit.,

p. 696; J. T. Medina, op. tit., pp. 114, 191, 193. The manuscript of Gabriel

de Granada's trial was published with a preface and notes bv Dr. Cyrus

Adler. Cf. "Trial of Gabriel de Granada by the Inquisition of Mexico. 1642

1652," in PAJHS, vol. VII (1899), pp. 1-134.

30 Genaro Garcia, op. cit., vol. XXVIII, pp. 70-71; L. G. Obreg6n, op. cit., p. 697.

31 Genaro Garcia, op. cit., vol. XXVIII, pp. 73-75; L. G. Obreg6n, op. tit., p. 694.

32 Genaro Garcia, op. cit., vol. XXVIII, pp. 67-70; L. G. Obreg<5n, op. cit.,

pp. 695-696; J. T. Medina, op. cit., pp. 113, 115, 191, 193.

[241

This content downloaded from

87.77.195.98 on Mon, 28 Sep 2020 21:55:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

AMERICAN JEWISH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

and his mother made nine visits to a Saint Moses that a certain

woman had painted.33 He was reconciled in 1646.

Miguel Tinoco, a twenty-three-year-old bachelor, apprenticed to a

silversmith, functioned as sexton of the secret Jewish community.

Three days before Passover he distributed unleavened bread which

had been baked by Blanca Enriquez, the "great Jewess" [la gran

]udia\. Miguel became reconciled in 1646.34

Pedro Lopez de Morales, having been born in Rodrigo, Spain, was

a forty-nine-year-old miner in Ixtan, Mexico. He was the son of

Morales de Mercado of Portugal. It was proven that he had intended

to send his little daughter [mestizuela, since her mother was a Mexi

can Indian], to Spain to be instructed in Judaism by relatives there.

Morales was reconciled in 1647.35

Pedro Fernandez de Castro, born in Valladolid, Spain, and bearing

signs of circumcision, was a thirty-four-year-old peddler in Santiago

de los Valles, Mexico. He was the son of the lawyer, Ignacio de

Aguado, of Portuguese descent. Pedro had previously lived in Ferrara,

Italy, as a freely professing Jew and had also visited the synagogues

in Genoa and in Livorno, Italy. He arrived in Mexico in 1640 in

order to cash the promised dowry from his rich father-in-law, Simon

Vaez Sevilla. Pedro had married Sim6n's daughter, Leonor Vaez, in

Pisa, where she was living with a sister and nieces. When he fell

into the hands of the Inquisition he declared that in the house of

his father-in-law in Mexico City he met crypto-Jews from Spain,

Peru, and the Philippines, and that they observed fast days together.

He became reconciled in 1647.86

Francisco de Leon Jaramillo, born in Mexico in 1626 and un

married, was the son of Duarte de Leon Jaramillo (burned at the

stake in 1649) and Isabel Nunez. He deposed that his father had

circumcised him in the presence of his mother and grandmother, Justa

Mendes, and that he had learned the common prayers of Judaizers

in his father's home. He became reconciled in 1647.87

33 Genaro Garcia, op. cit., pp. 52-53; L. G. Obreg6n, op. cit., p. 696; J. T. Medina,

op. cit., 114, 193.

34 Genaro Garcia, op. cit., pp. 76-77; L.G. Obregdn, op. cit., p. 698; J. T. Medina,

op. cit., p. 193.

35 Genaro Garcia, op cit., pp. 124-125; L. G. Obreg<5n, op. cit., p. 696; J. T.

Medina, op. cit., p. 117.

36 Genaro Garcia, op. cit., pp. 125-128; L. G. Obregdn, op. cit., p. 697; J. T.

Medina, op. cit., pp. 117, 194.

37 Genaro Garcia, op. cit., pp. 109-111; Anonimo, Autos-de-Fe (Mexico, 1953) ,

pp. 7-14; L. G. Obregdn, op. cit., p. 697; J. T. Medina, op. cit., pp. 116, 195;

Misterios de la Inquisicidn y otras Socieclades Secretas de Espana (traducido

del francos, Mexico, 1850), p. 25.

242 ]

This content downloaded from

87.77.195.98 on Mon, 28 Sep 2020 21:55:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CRYPTO-JEWS IN MEXICO: 17th CENTURY

Jorge Jacinto Bazan (alias Baca), of Portuguese Jewish descent,

had been born in Malaga, Spain, in 1610. He was married to Dona

Blanca Juarez, a niece of Juana Enriquez (wife of Simon Vaez Sevilla),

and was a merchant in Mexico City. At the age of thirteen, he had

been circumcised in Marseilles, France, by a surgeon from Florence,

Italy. He migrated to Mexico in the year 1637, bringing a letter of

recommendation to Simon Vaez Sevilla. Sevilla sent him as a salesman

on trips to the interior of Mexico. Once in Sevilla's house he met a

famous rabbi recently arrived from Spain who was acquainted with

his Jewish parents in Italy. Bazan himself had been in Pisa, Livorno,

Salonika, and Marseilles. The famous rabbi advised him that, in

case of interrogation by the Inquisition, he should say he was a

circumcised Jew from Pisa. Bazan was considered a fine Jew [un

Judio fi.no], and his pretty wife was very religious too. He was re

conciled in 1648.38

Francisco Lopes Dias [nicknamed el chato], was born in the year

1608 in Gasteloblanco, Portugal, and at this time lived in Zacatecas,

Mexico. He and his family had left Portugal because of severe persecu

tions of crypto-Jews and had first settled in Seville. They prayed and

fasted there together with many other Portuguese Judaizers. On Yom

Kippur one of them recited prayers from a Hebrew prayer book. In

1637, Dias migrated to Mexico City and continued to observe Judaism

with Mexican Judaizers. He advised them as to what they should

do and say in case of persecution by the Inquisition. Dias was re

conciled in 1648.39

Beatriz Enriquez, twenty-nine years old, was the daughter of Antonio

Rodrigues Arias and Blanca Enriquez of Seville, and married to

Tomas Nunez de Peralta. She told the Court that at the age of twelve

she was instructed in Judaism by her mother. The whole night before

the Day of Atonement she prayed with her parents, standing without

shoes. She had married Peralta because he was known to be a pious

Jew. Good Jews like Peralta, and especially children of martyrs, were

considered as being aristocrats and highly eligible for marriage.

Judaizers used to assemble in the house of Simon Vaez Sevilla who

often told the guests that in case of imprisonment and persecution by

the Inquisition they should not, even under torture, admit anything

or denounce anybody. He used to boast that his arms were strong

38 Genaro Garcia, op cit., pp. 133-269; L. G .Obreg6n, op. tit., p. 699; Misterios,

pp. 46-48; J. T. Medina, op. cit., pp. 118-195.

39 Anonimo, pp. 11-22; Misterios, pp. 43-48; Relation del Tercero Auto particular

Mexico, 1648); L. G. Obreg6n, op. cit., p. 699; J. T. Medina, op. cit., p. 195.

[243

This content downloaded from

87.77.195.98 on Mon, 28 Sep 2020 21:55:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

AMERICAN JEWISH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

enough to endure tortures. Blanca Enriquez said that after the burial

of a Judaizer visitors brought hardboiled eggs (which had to be eaten

without salt). Such a visit of mourners was considered a very good

deed and called Aveluz.40 After a death, the water from all pitchers

in the house was poured out, because it was believed, that the depart

ing soul had washed away all his sins in this water. Whenever there

was no rabbi present to perform a marriage ceremony, the Judaizers

would marry by giving each other their word of honor and then go

to the Church for the required Catholic marriage. In case a rabbi

[.sacerdote de su ley] was available, he offered the benedictions over

a glass of wine; the married couple and the guests then drank of

the wine, and the glass was thrown upward and broken. Beatriz

Enriquez was reconciled in 1648.41

Micaela Enriquez, the thirty-four-year-old sister of this Beatriz

Enriquez, was married to Sebastian Cardoso. She repeated the same

charges to the court as her sister and added that on Friday evenings

her mother used to %ht oil lamps instead of the usual candles. In

order not to attract the attention of the slave-girl servants, the lamps

were hidden in an empty wooden box. Her mother used to call the

Old Christians "Orcos"*2 and instructed the children neither to eat

pork nor any meat at the same time with butter. After the death

of her grandmother, so many Judaizers came to their house for the

Aveluz ceremony, that it looked like a public synagogue. Dona Micaela

was called a witch [hechizera] because she carried on her body certain

roots and the teeth of dead people. She was reconciled in 1648.43

Dona Rafaela Enriquez, another daughter of Dona Blanca Enriquez

and Antonio Rodriguez, was married to Gaspar Juarez. She deposed

that when she was twelve or thirteen her parents sent her to a relative

for instruction in Judaism. The whole family in Mexico practiced

Judaism almost as openly as they had done in Amsterdam, Livorno,

and Pisa. They married only crypto-Jews and were categorically op

posed to intermarriage with Old Christians because they knew that the

offspring not receiving a Jewish education would be lost to Judaism.

Before the Day of Atonement, everybody took warm baths and lighted

<o Even though the word Aveluz sounds Spanish, there is no such word in the

Spanish language. It is obviously the Hebrew word Avelut (mourning).

Misterios, pp. 34-38; Anonimo, vol. IV, pp. 15-35; Genaro Garcia, vol. XXVIII,

pp. 203-212; L. G. Obreg6n, op. cit., p. 699; J. T. Medina, op. cit., pp. 112,

116, 117 and 195.

42 Orcos most probably is an abbreviation of porcos (hogs).

43 Misterios, pp. 53-54; L. G. Obregdn, op. cit., p. 699; J. T. Medina, op. cit.,

pp. 119, 195, 218.

244 ]

This content downloaded from

87.77.195.98 on Mon, 28 Sep 2020 21:55:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CRYPTO-JEWS IN MEXICO: 17th CENTURY

about eighty wax candles for the souls of the living and the dead.

In Simon's house meetings were held for discussions of Judaism. When

the wave of arrests began, the leaders distributed among the crypto

Jews notes concerning the Catholic doctrines in order that everybody

could learn them by heart and recite them in case of arrest, because

prisoners were usually asked to prove that they were good Catholics

by reciting the Paternoster, the Ave Maria, the Credo, and the Salve

Regina. Besides, everybody was instructed not to confess anything and

was threatened in case they denounced others. Dona Rafaela Enriquez

was reconciled in 1648.44

Dona Blanca Juarez, a native of Mexico, was the twenty-two-year

old daughter of Rafaela Enriquez. She was very religious and was

considered a Santa [holy woman]. She was married to Jorge Jacinto

Bazan, and it was expected that she would give birth to the Messiah.

Her family dressed her in a tunic of silver cloth and seated her in the

center of visitors who prayed that she should give birth to the Messiah.

She could speak the African language of Angola and used that lan

guage in speaking to the Negro servants in prison. She told the

Inquisitors that her grandmother, Dona Blanca Enriquez, on the Day

of Atonement used to put her hands on her head while she was

kneeling, to bless her in the name of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. She

became reconciled in 1648.45

Dona Violante Juarez, born in Lima, Peru, was the thirty-six-year

old illegitimate daughter of Gaspar Juarez and was married to Manuel

de Mello. Their house in Guadalajara was a prayer center for

Judaizers. She became reconciled in 1648.46

Leonor Martinez, the fourteen-year-old daughter of the martyr

Sobremonte, told the Court that her parentts and grandparents had

instructed her in Judaism. She had assisted at a Jewish marriage

which was afterwards celebrated in the Church. Whenever her father

left on a journey he first assembled his children, put his hands on

their heads, and gave them his blessing. Leonor was a very religious

girl and was considered by the Mexican Judaizers as being a little

Santa47

a Relation del Tercero Auto particular (Mexico, 1648); Misterios, pp. 55-58;

L. G. Obreg6n, op. tit., pp. 698-699; J. T. Medina, op. tit., pp. 119, 195, 218.

45 cf. Relation del Tercero Auto particular (Mexico, 1648); L. G. Obreg6n,

op. tit., p. 699; J. T. Medina, op. cit., pp. 118, 195.

46 Relation, op. cit.; Misterios, pp. 63-65; L. G. Obreg6n, op. cit., p. 699; J. T.

Medina, op. cit., p. 195.

47 Relation, op. cit., Misterios, pp. 48-49; L. G. Obreg6n, op. cit., p. 699; J. T.

Medina, op. cit., pp. 118, 120, 195.

[245

This content downloaded from

87.77.195.98 on Mon, 28 Sep 2020 21:55:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

AMERICAN JEWISH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

Manuel de Mello arrived in Mexico in 1624 where he worked as

a silver- and goldsmith and was known as one of the finest Jews who

had ever migrated from Spain. He instructed many people in Judaism

and married a pious girl, Violante Juarez, daughter of Gaspar

Juarez. In order to be less exposed, they left Mexico City and went

to Guadalajara, where their house became the center [sinagoga] for

secret Jews, and where, whenever necessary, the secret Jews could

get food and help. He was reconciled in 1648.48

Ana Nunez, Antonio Nunez, and Clara Nunez were the daughters

of Leon Jaramillo who was burned at the stake in 1649. All three of

them had told the Inquisition the strange story mentioned earlier that

their father, when starting to instruct them in Judaism, had cut a

piece of flesh from the left shoulder of each, roasted and eaten it.

Ana also said that her father beat her cruelly whenever he heard her

tell her rosary beads. Antonia said her father loved her more than

the other children and gave her nice dresses because she used to fast

and pray and observe Jewish rites. She further deposed that her

father had prayed with his face to the East while wearing a cap on

his head and a Jewish prayer shawl and phylacteries (una vestidura

colorada de bombazi con su cucurucho y capirote). Clara deposed

that her family had forbidden her to fraternize with Old Christians;

that the night after her mother was imprisoned she saw her father

and brothers bury silver money, ingots and other valuable things.

After her father's imprisonment, because she had been called Clara,

the Jewess, she changed her name to Josefa de Alzate and told people

she was a Moorish girl [Morisca~\. All three sisters were reconciled

in 1648.49

Rafael de Sobremonte was the young son of the martyr, Thomas

Trebino de Sobremonte, who was burned alive in 1649. Rafael, born

in Guadalajara, Mexico, in 1648 was only seventeen years old. He

told the Inquisitors that his father had circumcised him while his

mother, Dona Maria Gomez, and his grandmother held him in their

laps. Until he was healed a wax candle was burned nightly in his

room and his father prayed until dawn. After his convalescence he

was bathed and neatly dressed for the family's festivities. He was

brought up to be very religious. In 1643 and 1644, he accompanied his

father on a business trip to Zacatacas and Guadalajara, and they did

*8 Relation, op. tit., Misterios, pp. 51-52; L. G. Obreg6n, op. cit., p. 699.

49 Relation, op. tit., Antonimo, vol. IV, pp. 7-13 and 39-49, 46-55; Misterios,

pp. 30-34, 40-42; Genaro Garcia, op. cit., vol. XXVIII, pp. 201-203; J. T.

Medina, op. cit., pp. 117-119, 195.

246 ]

This content downloaded from

87.77.195.98 on Mon, 28 Sep 2020 21:55:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CRYPTO-JEWS IN MEXICO: 17th CENTURY

not cat on Thursdays, sometimes not even on Mondays. His father

instructed him in Jewish prayers and in Judaism generally. When

he returned to Mexico City his mother, grandmother and aunt were

very proud of the "new Judaizer."

Rafael further said that when he was traveling with his father

they were one day caught by a heavy rain shower. When his father

then heard him praying to the Queen of the Angels, he scolded him

and told him that God does not have a mother and that there exists

only one God who created heaven and earth. His father had also

confided in him his intention of soon taking the whole family away

from Mexico to a country where they could worship freely. Rafael

was reconciled in 1648.60

Dona Ana Enriquez, born in Seville, Spain, had already been

reconciled in Seville, and it was known that she had been very brave

and had not denounced anybody under torture. In Mexico City, she

was a fervent Judaizer and instructed others in Jewish rites and

ceremonies. People came to her to be cured by her prayers from the

consequences of an evil eye and bewitchment. In the case of a death

among the Judaizers she gave instructions on the rites to be observed.

She passed away in Mexico City before she could be apprehended.

Nevertheless, she was indicted and burned in effigy on April 11,

1649.51

Dona Blanca Enriquez, born in Lisbon, Portugal was the daughter

of Diego Nunez Batoca and Juana Rodriguez, both persecuted and

reconciled by the Inquisition in Granada, Spain. She was married to

Antonio Rodrigues Arias. The teachings of her mother Juana had

made her a very religious person and an instructor of Judaism in

Mexico. She educated her children—Beatrix, Micaela, and Rafaela

mentioned above—to practice Judaism and to teach it to her grand

children. She saw to it that they did not marry Old Christians whom

she always called enemies. All crypto-Jews in Mexico considered her

as the master-teacher [maestra] of Jewish prayers and ceremonies.

She believed the year 1642 to 1643 was the date of the arrival of the

Messiah who would liberate all of them from the persecutions by the

Inquisition. Dona Blanca Enriquez died in prison. Her body was

BO Relacion, op. cit., Misterios, pp. 58-60; L. G. Obreg6n, op. cit., p. 699; J. T.

Medina, op. cit., pp. 119, 120, 195.

61 Cf. P. Mathias de Bocanegra, Auto General de la Fee 1649 (Mexico, 1649);

L. G. Obreg6n, op. cit., p. 705; J. T. Medina, op. cit., p. 206.

[247

This content downloaded from

87.77.195.98 on Mon, 28 Sep 2020 21:55:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

AMERICAN JEWISH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

exhumed and delivered to the secular powers for burning at the stake

on April llj 1649.62