Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Suma 2020 Assessment 1

Suma 2020 Assessment 1

Uploaded by

api-473650460Copyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- 4ac1 01 Rms 20240125Document17 pages4ac1 01 Rms 20240125Nang Phyu Sin Yadanar KyawNo ratings yet

- Libro Creative Leadership PuccioDocument278 pagesLibro Creative Leadership PuccioIsabella MontenegroNo ratings yet

- Assessment 1 FinalDocument7 pagesAssessment 1 Finalapi-473650460No ratings yet

- Assessment 1 FinalDocument7 pagesAssessment 1 Finalapi-473650460No ratings yet

- Multifactor Leadership QuestionnaireDocument28 pagesMultifactor Leadership Questionnairerubens100% (4)

- Final EssayDocument15 pagesFinal Essayapi-526201635No ratings yet

- Howe Brianna 1102336 Task2a Edu410Document8 pagesHowe Brianna 1102336 Task2a Edu410api-521615807No ratings yet

- Beat0075-Emma Beaton - Assignment 1 - Educ2420Document4 pagesBeat0075-Emma Beaton - Assignment 1 - Educ2420api-428513670No ratings yet

- Reconciliation PedagogyDocument4 pagesReconciliation Pedagogyapi-360519742No ratings yet

- Assignment 1: Aboriginal Education (Critically Reflective Essay)Document11 pagesAssignment 1: Aboriginal Education (Critically Reflective Essay)api-355889713No ratings yet

- Major AssignmentDocument7 pagesMajor Assignmentapi-524427620No ratings yet

- Assessment 2 - ActivityDocument4 pagesAssessment 2 - Activityapi-368607098No ratings yet

- Position Paper - Inclusive PracticeDocument5 pagesPosition Paper - Inclusive Practiceapi-339522628No ratings yet

- The Gold Coast Transformed: From Wilderness to Urban EcosystemFrom EverandThe Gold Coast Transformed: From Wilderness to Urban EcosystemTor HundloeNo ratings yet

- Performance Evaluation Form (Staff)Document1 pagePerformance Evaluation Form (Staff)ckb18.adolfoNo ratings yet

- Achievement Cluster Planning Cluster Power Cluster: Page 1 of 1Document1 pageAchievement Cluster Planning Cluster Power Cluster: Page 1 of 1MESIE JEAN PARALNo ratings yet

- Industrial Attachment Excel CompletedDocument23 pagesIndustrial Attachment Excel CompletedObaphemy El-Rookie Kappo100% (1)

- Summer 2020 EssayDocument3 pagesSummer 2020 Essayapi-410625203No ratings yet

- Suma2017-18assessment1Document10 pagesSuma2017-18assessment1api-428109410No ratings yet

- Final EssayDocument6 pagesFinal Essayapi-375391245No ratings yet

- Academic Essay. Written Reflections & Critical AnalysisDocument4 pagesAcademic Essay. Written Reflections & Critical AnalysisEbony McGowanNo ratings yet

- 2H2018Assessment1Option1Document7 pages2H2018Assessment1Option1Andrew McDonaldNo ratings yet

- Aboriginal & Culturally Responsive Pedagogies: Critical Reflective EssayDocument9 pagesAboriginal & Culturally Responsive Pedagogies: Critical Reflective Essayapi-460175800No ratings yet

- 2h 2019 Assessment 1Document11 pages2h 2019 Assessment 1api-405227917No ratings yet

- Acrp Essay - Rachel Jolly 19665131Document9 pagesAcrp Essay - Rachel Jolly 19665131api-553761934No ratings yet

- Acrp Essay - Assessment 1Document13 pagesAcrp Essay - Assessment 1api-368764995No ratings yet

- Rimah Aboriginal Assessment 1 EssayDocument8 pagesRimah Aboriginal Assessment 1 Essayapi-376717462No ratings yet

- Aboriginal Individual Reflection RaDocument6 pagesAboriginal Individual Reflection Raapi-376717462No ratings yet

- Reflection Acrp FinalDocument4 pagesReflection Acrp Finalapi-357662510No ratings yet

- Final Essay - CompleteDocument4 pagesFinal Essay - Completeapi-473289533No ratings yet

- Eeo311 Assignment 2 Janelle Belisario Dean William NaylorDocument24 pagesEeo311 Assignment 2 Janelle Belisario Dean William Naylorapi-366202027100% (1)

- Acpr A1 FinalDocument15 pagesAcpr A1 Finalapi-332836953No ratings yet

- Aboriginal Reflection 2 - 2Document6 pagesAboriginal Reflection 2 - 2api-407999393No ratings yet

- Pd02 35 Aboriginal EducationDocument14 pagesPd02 35 Aboriginal EducationAnwar HussainNo ratings yet

- Evidence Standard 1 2Document12 pagesEvidence Standard 1 2api-368761552No ratings yet

- Aboriginal & Culturally Responsive Pedagogies: Assessment 1-EssayDocument9 pagesAboriginal & Culturally Responsive Pedagogies: Assessment 1-Essayapi-435791379No ratings yet

- Assignment 2 Aboriginal Education Isabel SarreDocument6 pagesAssignment 2 Aboriginal Education Isabel Sarreapi-465723124No ratings yet

- Final Copy David Philo Unit 102082 Philosophy of Classroom Management Document R 2h2018Document15 pagesFinal Copy David Philo Unit 102082 Philosophy of Classroom Management Document R 2h2018api-408497454No ratings yet

- Educ2420 Final Essay Part 1 CsvilansDocument3 pagesEduc2420 Final Essay Part 1 Csvilansapi-359286252No ratings yet

- Major Essay GoodDocument5 pagesMajor Essay Goodapi-472902076No ratings yet

- 2Document6 pages2api-519322453No ratings yet

- Acrp A1Document4 pagesAcrp A1api-456235166No ratings yet

- Suma2018 Assignment1Document8 pagesSuma2018 Assignment1api-355627407No ratings yet

- G Stewart s226337 Etl310 A2 2ndDocument24 pagesG Stewart s226337 Etl310 A2 2ndapi-279841419No ratings yet

- Ppce Self ReflectionDocument2 pagesPpce Self Reflectionapi-357572724No ratings yet

- Acrp - A2 Lesson PlanDocument9 pagesAcrp - A2 Lesson Planapi-409728205No ratings yet

- Ppce Self Reflection FormDocument2 pagesPpce Self Reflection Formapi-435535701No ratings yet

- Designing Teaching and Learning A1Document7 pagesDesigning Teaching and Learning A1api-460568887No ratings yet

- Sc2a Assessment One - CulhaneDocument53 pagesSc2a Assessment One - Culhaneapi-485489092No ratings yet

- Autumn Assessment2Document7 pagesAutumn Assessment2api-320308863No ratings yet

- What Are Some of The Key Issues' Teachers Need To Consider For Working Successfully With Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Students?Document4 pagesWhat Are Some of The Key Issues' Teachers Need To Consider For Working Successfully With Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Students?api-465449635No ratings yet

- A2 Curriculum 1bDocument34 pagesA2 Curriculum 1bapi-408430724No ratings yet

- Suma2018 19 Reflections SsiDocument11 pagesSuma2018 19 Reflections Ssiapi-357536453No ratings yet

- Critical Review Claudia Norris-GreenDocument5 pagesCritical Review Claudia Norris-Greenapi-361866242No ratings yet

- DSJL Assessment 2 Part B Critical Personal ReflectionDocument6 pagesDSJL Assessment 2 Part B Critical Personal Reflectionapi-357679174No ratings yet

- Acrp Unit OutlineDocument14 pagesAcrp Unit Outlineapi-321145960No ratings yet

- Acrp ReflectionDocument5 pagesAcrp Reflectionapi-327348299No ratings yet

- Unit Outline Aboriginal FinalDocument12 pagesUnit Outline Aboriginal Finalapi-330253264No ratings yet

- Researching Teaching Learning Assignment 2Document12 pagesResearching Teaching Learning Assignment 2api-357679174No ratings yet

- Ppce Reflection WeeblyDocument2 pagesPpce Reflection Weeblyapi-435630130No ratings yet

- Summer 2017-2018 Assessment1Document10 pagesSummer 2017-2018 Assessment1api-332379661100% (1)

- Assessment 2 InclusiveDocument5 pagesAssessment 2 Inclusiveapi-554490943No ratings yet

- Acrp ReflectionDocument7 pagesAcrp Reflectionapi-429869768No ratings yet

- Aboriginal Assignment 20Document5 pagesAboriginal Assignment 20api-369717940No ratings yet

- Designing Teaching & Learning: Assignment 2 QT Analysis TemplateDocument12 pagesDesigning Teaching & Learning: Assignment 2 QT Analysis Templateapi-403358847No ratings yet

- Research Paper - Angela Carolina RoennauDocument16 pagesResearch Paper - Angela Carolina RoennauCarolina RoennauNo ratings yet

- RTL Assessment 2Document8 pagesRTL Assessment 2api-357684876No ratings yet

- Reconciliation EssayDocument8 pagesReconciliation Essayapi-294443260No ratings yet

- 1 Final AssignmentDocument15 pages1 Final Assignmentapi-473650460No ratings yet

- Assignment 2 Bin Liners Lesson Plan Analysis, Revision and JustificationDocument9 pagesAssignment 2 Bin Liners Lesson Plan Analysis, Revision and Justificationapi-473650460No ratings yet

- A Qualitative Study of Teacher Perspectives of Assessment in STEM EducationDocument19 pagesA Qualitative Study of Teacher Perspectives of Assessment in STEM Educationapi-473650460No ratings yet

- 1 Final AssignmentDocument15 pages1 Final Assignmentapi-473650460No ratings yet

- StudentsResult - 38 - Evening - BS English - ENGL4141 - DGK-BS ENGLISH-EVE - Summative Exam - UExamDocument3 pagesStudentsResult - 38 - Evening - BS English - ENGL4141 - DGK-BS ENGLISH-EVE - Summative Exam - UExamTalhaNo ratings yet

- Strategic Leadership: By: Erica B. ArceDocument20 pagesStrategic Leadership: By: Erica B. ArceBryan B. Arce100% (1)

- Project Scope Management Units 1 To 7Document30 pagesProject Scope Management Units 1 To 7Reshad JoomunNo ratings yet

- Advantage and Disadvantage: Ling Shahrul Amin Fahmi HasifDocument4 pagesAdvantage and Disadvantage: Ling Shahrul Amin Fahmi HasifaminipgNo ratings yet

- ACCT 6621 S1 Syllabus 1Document5 pagesACCT 6621 S1 Syllabus 1Matthew ChristopherNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae: ObjectiveDocument2 pagesCurriculum Vitae: ObjectiveShakir MunhakkalNo ratings yet

- CTU Online InfoDocument4 pagesCTU Online Infojamjayjames3208100% (2)

- Episode 611 Jim KwikDocument52 pagesEpisode 611 Jim KwikKiran James100% (2)

- Walt Whitman Research Paper OutlineDocument5 pagesWalt Whitman Research Paper Outlineltccnaulg100% (1)

- Research Process 11Document12 pagesResearch Process 11Xalu XalManNo ratings yet

- Philosophy of TeachingDocument10 pagesPhilosophy of Teachingapi-508763315No ratings yet

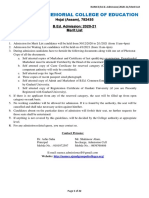

- Nazir Ajmal Memorial College of Education: Hojai (Assam), 782435 B.Ed. Admission: 2020-21 Merit ListDocument22 pagesNazir Ajmal Memorial College of Education: Hojai (Assam), 782435 B.Ed. Admission: 2020-21 Merit ListrakeshNo ratings yet

- CV Layout For DIB Students With Work HistoryDocument6 pagesCV Layout For DIB Students With Work HistoryTìmLạiNo ratings yet

- Speech and Oral CommunicationDocument9 pagesSpeech and Oral CommunicationKaren MolinaNo ratings yet

- Pre Grado Week 2 - Task Assignment - My University Class Sessions Then and NowDocument8 pagesPre Grado Week 2 - Task Assignment - My University Class Sessions Then and NowKathy zzjjjNo ratings yet

- Score SheetDocument1 pageScore SheetDianne Kate NacuaNo ratings yet

- AfL Assignment FinalDocument16 pagesAfL Assignment FinalMontyBilly100% (1)

- DRRM PlanDocument62 pagesDRRM PlanAntartica Antartica75% (4)

- Gender Differences in Career Aspiration Among Public Secondary Schools Students in Nairobi County, KenyaDocument10 pagesGender Differences in Career Aspiration Among Public Secondary Schools Students in Nairobi County, KenyaajmrdNo ratings yet

- Tate Encounters: Britishness and Visual CultureDocument36 pagesTate Encounters: Britishness and Visual CultureMirtes OliveiraNo ratings yet

- EDUC. 6 Module 1Document16 pagesEDUC. 6 Module 1Larry VirayNo ratings yet

- Course Guide-Pe3Document2 pagesCourse Guide-Pe3Macabulos Edgardo SableNo ratings yet

- Sarai M. Alvarez Zepeda: E-Mail: LinkedinDocument4 pagesSarai M. Alvarez Zepeda: E-Mail: Linkedinapi-676558382No ratings yet

- Jadwal Kuliah MKK Periode 30 September 2020Document15 pagesJadwal Kuliah MKK Periode 30 September 2020Edy Anugrah PutraNo ratings yet

Suma 2020 Assessment 1

Suma 2020 Assessment 1

Uploaded by

api-473650460Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Suma 2020 Assessment 1

Suma 2020 Assessment 1

Uploaded by

api-473650460Copyright:

Available Formats

19897921 Peter Fahim

The process of creating a culturally-responsive pedagogy that enables Indigenous students to

excel and develop rich connections with their cultural and linguistic backgrounds is reliant on

both policy and professional reforms that have yet to be fully realised. Lowe and Yunkaporta

(2018) and Castagno and Brayboy (2008) both emphasise the importance of constructing a

culturally appropriate curriculum that supports the learning of Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander students. However, it takes more than just a supportive curriculum to close the gap.

There is a need for a change in national standards as per the Australian Institute for Teaching

and School Leadership (AITSL) and investment in the professional development of teachers such

as that provided by the Stronger and Smarter Institute. It also takes connection with the

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community and employment of more Indigenous teachers

in schools (Price & Rogers, 2019).

A culturally responsive curriculum is one of the essential ways in which to engage Indigenous

learners. Such a curriculum must be infused with rich connections to the Indigenous students’

cultural and linguistic backgrounds within their family and community contexts (Belgrade,

Mitchell & Arquero, 2002). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students should be able to see

themselves (their identities and culture) in the curriculum of every learning area and should be

able to participate fully in the curriculum. For this to happen they first need teachers who are

skilled and are culturally competent in the local context and second provide high expectations

for learning that incorporates Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives. A culturally

responsive curriculum is one which makes linkages between local Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander histories and cultures and the learning areas in the curriculum. AITSL gives the example

of ACSSU048 which discusses the Earth’s rotation on its axis causing regular changes including

night and day. Indigenous Australian use their knowledge of astronomy for time-keeping

through observing the rising and setting of the stars, solar cycle and lunar phases to indicate

special events. The curriculum also highlights positive representations of local Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander people in art, sport and NAIDOC as well as ways in which people fill key

roles in their own and the broader community such as the Yarning Strong set of chapter books

that introduce a range of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander authors. As a cross-curriculum

priority in the Australian curriculum, the Aboriginal studies framework consists of three key

concepts; Country/Place, Culture and People. There are nine organising ideas that help teachers

link these three interconnected concepts to learning areas in the curriculum and to the general

capabilities; particularly to personal and social capability, ethical understanding and

intercultural understanding. However, as per Lowe and Yunkaporta’s (2018) critical analysis of

the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander content of the curriculum, the stated intention of

ACARA to ensure “that all young Australians will be given the opportunity to gain a deeper

understanding and appreciation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories and cultures”,

(Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority, 2011), has not been achieved.

Lowe and Yunkaporta (2018) indicate that the curriculum content does not provide teachers

with the tools to create learning experiences that would enable students to understand the

depth of the histories and cultures of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and their

significance within Australia.

Summer Course 2020 Assessment 1

19897921 Peter Fahim

In order for the curriculum to be expounded on in a meaningful way, teachers need to be

culturally competent. This involves understanding the cultural background of their students and

using this understanding to create learning opportunities. Also, by being familiar with the

Indigenous students’ lifestyles, teachers can find suitable teaching methods for reaching these

students (Abrams, Taylor & Guo, 2013). AITSL aims to ensure teachers are culturally competent

by educating them on Aboriginal Australia, giving mandatory Aboriginal cultural education

through professional learning and career development and identifying and engaging the NSW

AECG Inc. and Aboriginal communities as partners in Aboriginal education. Teachers can

develop professional learning through resources including; ACARA’s Australian Curriculum

Specialist, Stronger Smarter Institute, What Works, Reconciliation Australia; Respect,

Relationships, Reconciliation; and State-based Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Education

teams and consultative groups (Price & Rogers, 2019). For instance, by using “What Works”

teachers can find ways to improve literacy by looking beyond whether or not students can spell

all the words and instead find ways they can find identity by, for example, creating a ‘Koorie

Students’ Room’ where students can spend time, seek help with work or when there is trouble

or having ‘mother-tongue’ classes so students can maintain their local Indigenous language

(What Works Team, 2009). Teachers need to have high expectations for students and ensure

those expectations are realised. According to Brayboy and Castagno (2008), non-Indigenous

teachers simply do not know enough about how to teach Indigenous children. Hence, in order

for teachers to fulfill assessment criteria focus areas 1.4 and 2.4 “to provide the best possible

educational opportunities for Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islander people, and to

provide all Australians with knowledge and understandings about Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander histories, cultures and languages that are accurate, culturally correct, and current.” it

remains their responsibility to access the resources available (AITSL, 2011). Main, Nichol and

Fennel (2000) suggest that improving Aboriginal students’ understanding of human sciences

will mean their health also improves and suggests several pedagogical strategies to reach

different types of learners. They describe, focusing on group projects, introducing peer tutoring,

not insisting on direct or immediate answers and being explicit about the purposes of

questions. Main, Nichol and Fennel (2000) draw attention to the various types of learners

including holistic and imaginal learners and provide strategies based on each learner type.

Hence, it is not simply about understanding the cultural background of the students but also

knowing them personally. For example, in a class with holistic learners, a teacher explaining the

cardiovascular system could keep a model of the cardiovascular system in relation to the rest of

the body and reinforce often. “Stronger Smarter” philosophy recommends establishing a

school culture that embraces cultural diversity, that is not all students are the same. Schools

need to encourage a positive sense of Indigenous cultural identity, such that they come to

school and feel proud of who they are just as they are at home and hence feel at home when

they are at school (Sarra, 2007).

Culturally competent pedagogy has been backed up by policy as long ago as 1975 when the

Education for Aborigines: Report to the Schools Commission (Aboriginal Consultative Group)

was created and in the 1990s the National Statement of Principles and Standards for more

Culturally Inclusive Schooling in the 21st Century and A Model of More Culturally Inclusive and

Educationally Effective Schools (Schwab, 2018). According to Karmel (1973), policy

Summer Course 2020 Assessment 1

19897921 Peter Fahim

recommended a grass-roots approach to the control of schools, equality for the disadvantaged,

encouraging diversity, community involvement, building core skills and lifelong learning

(Schwab, 2018). Although these principles have evolved over the years, they have been

significant in developing Indigenous education policy (Price & Rogers, 2019). In 2000-2001 the

‘What Works’ project was meant to accelerate the achievement of educational equality for

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students. The Department of Education and the Arts

prepared guidelines that embedded Indigenous perspectives within school practices so that

Indigenous students ‘develop their sense of identity and pride in their culture, as well as

building knowledge and understanding of their cultural heritage, thus contributing to

developing a positive self-concept’ (Department of Education and the Arts, QLD, 2005).

However, despite these policies and their implication of finding solutions, the majority of

teachers and schools remain unskilled with regards to relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander parents, caregivers and students. This is due to policies proceeding along a course of

untested assumptions such as that all Indigenous students are alike (they have a similar

lifestyle, beliefs, choices and needs) and that principles of ‘consultation, ‘implementation’ and

‘community control’ are included without consideration for how it would actually look in the

context of Indigenous Australian communities (Schwab, 2018). Also, education policies have

been allowed to continue their process of starting reform then stopping repeatedly. There

needs to be continuity, where appropriate programs are resourced with a sustained effort from

state and territory education systems (Price & Rogers, 2019). Also, as recommended by the

DETYA (Commonwealth Department of Education, Training and Youth Affairs) study in 2000,

partnering with the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community throughout the

educational process, including policy making is key (McRae et al, 2000).

Partnering with community forms the crux of creating a culturally- responsive pedagogy. When

departments of school education enter into partnerships with Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander people throughout the whole educational process they empower them to become

active partners. Hence, the knowledge and culture of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

communities is valued and the programs that are created are more likely to be effective (Price

& Rogers, 2019). ‘What Works’ provides advice to all teachers about how school staff members

can develop partnerships. It mentions the importance of kinship to Indigenous peoples, that the

most important unit is family (over the generations and networks of relationships) who will

always be the educators of their children. Hence, if the interests of families and schools are

aligned and there is mutual support between school and home, education will be more

successful (What Works Team, 2009). Partnering begins with pre-service teachers having a yarn

with a member of the Aboriginal community in a setting preferred by the community member.

It has been proven that through conversations like this preservice teachers are motivated to

broaden their limited understanding of Aboriginal culture. Also, the creation of policy to close

the educational gap must also be a joint venture undertaken with Indigenous peoples and their

children (Price & Rogers, 2019). As Dr Chris Sarra said, ‘It is time for doing things with

Indigenous communities and not to Indigenous communities’ (2008). Teachers must discuss

with their students and their parents and caregivers about what it is that can be done together.

This involves making informal contact, getting to know each other rather than doing formal

business, looking for ways to celebrate and acknowledge community events, finding ways for

Summer Course 2020 Assessment 1

19897921 Peter Fahim

parents to be involved in the school (canteen, sports coaching, homework centres). A practical

application of partnering is through use of PLPs (personal learning plans) where a teacher sits

with the student’s family and formulates a personal learning plan based on the student’s

interests, talents, future plans, current class content, how the partners will contribute and how

success will be celebrated (What Works Team, 2009).

I intend to effect change in my future classroom by understanding the cultural identity of my

students and learning to honour their culture, language and world views. I will find ways to

include aspects of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander history and culture in the curriculum

and find opportunities to connect with perspectives of my students. I will have high

expectations of my Indigenous students and demonstrate to them regularly that they will

succeed. I will also develop conversations and relationships with Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander members of the community to learn and to partner in educating their children (Price &

Rogers, 2019). As a STEM teacher, teaching several subjects with the least references to

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge and culture (the least being mathematics) I will

look for opportunities to connect with Indigenous students and make the content suitable to

their way of thinking (Abrams, Taylor & Guo, 2012). I will also find fun ways to connect with the

local community (whether it be the local footy team or cultural venue) to encourage students

to use their learned skills practically. For instance, looking at how Indigenous communities used

to care for the environment and how we use similar concepts till today.

References

Abrams, E., Taylor, P. C., & Guo, C. J. (2013). Contextualizing culturally relevant science and

mathematics teaching for indigenous learning. International Journal of Science and

Mathematics Education, 11(1), 1-21.

AITSL (Australian Institute of Teaching Standards and Leadership). (2011) . National Professional

Standards for Teachers (the Standards). Melbourne: Educational Services Australia.

Department of Education and the Arts, Qld . (2005). Closing the Gap Education Strategy.

McRae , D. ,et. al. (2000). What Works? Explorations in improving outcomes for Indigenous

students. Canberra: Australian Curriculum Studies Association.

Main, D., Nichol, R., & Fennell, R. (2000). Reconciling pedagogy and health sciences to promote

Indigenous health. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 24(2), 211-213.

Price, K., & Rogers, J. (Eds.). (2019). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander education. Cambridge

University Press.

Sarra, C. (2007). Stronger, Smarter, Sarra. Teacher: The National Education Magazine, (Mar

2007), 32.

Summer Course 2020 Assessment 1

19897921 Peter Fahim

Sarra, C. (2008). ‘Getting it Right: Indigenous Leadership and Beyond’. Keynote Address to Jobs

Australia National Conference, 9 September.

Schwab, R. (2018). Twenty years of policy recommendations for indigenous education:

overview and research implications. Canberra, ACT: Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy

Research (CAEPR), The Australian National University.

What Works Team. (2009). Conversations > relationships > partnerships: A resource for the

community. National Curriculum Services: Commonwealth of Australia.

What Works Team. (2010). The Work Program. Improving outcomes for Indigenous students.

The Workbook and guide for school educators, 3rd, revised edition. National Curriculum

Services: Australia.

Summer Course 2020 Assessment 1

You might also like

- 4ac1 01 Rms 20240125Document17 pages4ac1 01 Rms 20240125Nang Phyu Sin Yadanar KyawNo ratings yet

- Libro Creative Leadership PuccioDocument278 pagesLibro Creative Leadership PuccioIsabella MontenegroNo ratings yet

- Assessment 1 FinalDocument7 pagesAssessment 1 Finalapi-473650460No ratings yet

- Assessment 1 FinalDocument7 pagesAssessment 1 Finalapi-473650460No ratings yet

- Multifactor Leadership QuestionnaireDocument28 pagesMultifactor Leadership Questionnairerubens100% (4)

- Final EssayDocument15 pagesFinal Essayapi-526201635No ratings yet

- Howe Brianna 1102336 Task2a Edu410Document8 pagesHowe Brianna 1102336 Task2a Edu410api-521615807No ratings yet

- Beat0075-Emma Beaton - Assignment 1 - Educ2420Document4 pagesBeat0075-Emma Beaton - Assignment 1 - Educ2420api-428513670No ratings yet

- Reconciliation PedagogyDocument4 pagesReconciliation Pedagogyapi-360519742No ratings yet

- Assignment 1: Aboriginal Education (Critically Reflective Essay)Document11 pagesAssignment 1: Aboriginal Education (Critically Reflective Essay)api-355889713No ratings yet

- Major AssignmentDocument7 pagesMajor Assignmentapi-524427620No ratings yet

- Assessment 2 - ActivityDocument4 pagesAssessment 2 - Activityapi-368607098No ratings yet

- Position Paper - Inclusive PracticeDocument5 pagesPosition Paper - Inclusive Practiceapi-339522628No ratings yet

- The Gold Coast Transformed: From Wilderness to Urban EcosystemFrom EverandThe Gold Coast Transformed: From Wilderness to Urban EcosystemTor HundloeNo ratings yet

- Performance Evaluation Form (Staff)Document1 pagePerformance Evaluation Form (Staff)ckb18.adolfoNo ratings yet

- Achievement Cluster Planning Cluster Power Cluster: Page 1 of 1Document1 pageAchievement Cluster Planning Cluster Power Cluster: Page 1 of 1MESIE JEAN PARALNo ratings yet

- Industrial Attachment Excel CompletedDocument23 pagesIndustrial Attachment Excel CompletedObaphemy El-Rookie Kappo100% (1)

- Summer 2020 EssayDocument3 pagesSummer 2020 Essayapi-410625203No ratings yet

- Suma2017-18assessment1Document10 pagesSuma2017-18assessment1api-428109410No ratings yet

- Final EssayDocument6 pagesFinal Essayapi-375391245No ratings yet

- Academic Essay. Written Reflections & Critical AnalysisDocument4 pagesAcademic Essay. Written Reflections & Critical AnalysisEbony McGowanNo ratings yet

- 2H2018Assessment1Option1Document7 pages2H2018Assessment1Option1Andrew McDonaldNo ratings yet

- Aboriginal & Culturally Responsive Pedagogies: Critical Reflective EssayDocument9 pagesAboriginal & Culturally Responsive Pedagogies: Critical Reflective Essayapi-460175800No ratings yet

- 2h 2019 Assessment 1Document11 pages2h 2019 Assessment 1api-405227917No ratings yet

- Acrp Essay - Rachel Jolly 19665131Document9 pagesAcrp Essay - Rachel Jolly 19665131api-553761934No ratings yet

- Acrp Essay - Assessment 1Document13 pagesAcrp Essay - Assessment 1api-368764995No ratings yet

- Rimah Aboriginal Assessment 1 EssayDocument8 pagesRimah Aboriginal Assessment 1 Essayapi-376717462No ratings yet

- Aboriginal Individual Reflection RaDocument6 pagesAboriginal Individual Reflection Raapi-376717462No ratings yet

- Reflection Acrp FinalDocument4 pagesReflection Acrp Finalapi-357662510No ratings yet

- Final Essay - CompleteDocument4 pagesFinal Essay - Completeapi-473289533No ratings yet

- Eeo311 Assignment 2 Janelle Belisario Dean William NaylorDocument24 pagesEeo311 Assignment 2 Janelle Belisario Dean William Naylorapi-366202027100% (1)

- Acpr A1 FinalDocument15 pagesAcpr A1 Finalapi-332836953No ratings yet

- Aboriginal Reflection 2 - 2Document6 pagesAboriginal Reflection 2 - 2api-407999393No ratings yet

- Pd02 35 Aboriginal EducationDocument14 pagesPd02 35 Aboriginal EducationAnwar HussainNo ratings yet

- Evidence Standard 1 2Document12 pagesEvidence Standard 1 2api-368761552No ratings yet

- Aboriginal & Culturally Responsive Pedagogies: Assessment 1-EssayDocument9 pagesAboriginal & Culturally Responsive Pedagogies: Assessment 1-Essayapi-435791379No ratings yet

- Assignment 2 Aboriginal Education Isabel SarreDocument6 pagesAssignment 2 Aboriginal Education Isabel Sarreapi-465723124No ratings yet

- Final Copy David Philo Unit 102082 Philosophy of Classroom Management Document R 2h2018Document15 pagesFinal Copy David Philo Unit 102082 Philosophy of Classroom Management Document R 2h2018api-408497454No ratings yet

- Educ2420 Final Essay Part 1 CsvilansDocument3 pagesEduc2420 Final Essay Part 1 Csvilansapi-359286252No ratings yet

- Major Essay GoodDocument5 pagesMajor Essay Goodapi-472902076No ratings yet

- 2Document6 pages2api-519322453No ratings yet

- Acrp A1Document4 pagesAcrp A1api-456235166No ratings yet

- Suma2018 Assignment1Document8 pagesSuma2018 Assignment1api-355627407No ratings yet

- G Stewart s226337 Etl310 A2 2ndDocument24 pagesG Stewart s226337 Etl310 A2 2ndapi-279841419No ratings yet

- Ppce Self ReflectionDocument2 pagesPpce Self Reflectionapi-357572724No ratings yet

- Acrp - A2 Lesson PlanDocument9 pagesAcrp - A2 Lesson Planapi-409728205No ratings yet

- Ppce Self Reflection FormDocument2 pagesPpce Self Reflection Formapi-435535701No ratings yet

- Designing Teaching and Learning A1Document7 pagesDesigning Teaching and Learning A1api-460568887No ratings yet

- Sc2a Assessment One - CulhaneDocument53 pagesSc2a Assessment One - Culhaneapi-485489092No ratings yet

- Autumn Assessment2Document7 pagesAutumn Assessment2api-320308863No ratings yet

- What Are Some of The Key Issues' Teachers Need To Consider For Working Successfully With Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Students?Document4 pagesWhat Are Some of The Key Issues' Teachers Need To Consider For Working Successfully With Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Students?api-465449635No ratings yet

- A2 Curriculum 1bDocument34 pagesA2 Curriculum 1bapi-408430724No ratings yet

- Suma2018 19 Reflections SsiDocument11 pagesSuma2018 19 Reflections Ssiapi-357536453No ratings yet

- Critical Review Claudia Norris-GreenDocument5 pagesCritical Review Claudia Norris-Greenapi-361866242No ratings yet

- DSJL Assessment 2 Part B Critical Personal ReflectionDocument6 pagesDSJL Assessment 2 Part B Critical Personal Reflectionapi-357679174No ratings yet

- Acrp Unit OutlineDocument14 pagesAcrp Unit Outlineapi-321145960No ratings yet

- Acrp ReflectionDocument5 pagesAcrp Reflectionapi-327348299No ratings yet

- Unit Outline Aboriginal FinalDocument12 pagesUnit Outline Aboriginal Finalapi-330253264No ratings yet

- Researching Teaching Learning Assignment 2Document12 pagesResearching Teaching Learning Assignment 2api-357679174No ratings yet

- Ppce Reflection WeeblyDocument2 pagesPpce Reflection Weeblyapi-435630130No ratings yet

- Summer 2017-2018 Assessment1Document10 pagesSummer 2017-2018 Assessment1api-332379661100% (1)

- Assessment 2 InclusiveDocument5 pagesAssessment 2 Inclusiveapi-554490943No ratings yet

- Acrp ReflectionDocument7 pagesAcrp Reflectionapi-429869768No ratings yet

- Aboriginal Assignment 20Document5 pagesAboriginal Assignment 20api-369717940No ratings yet

- Designing Teaching & Learning: Assignment 2 QT Analysis TemplateDocument12 pagesDesigning Teaching & Learning: Assignment 2 QT Analysis Templateapi-403358847No ratings yet

- Research Paper - Angela Carolina RoennauDocument16 pagesResearch Paper - Angela Carolina RoennauCarolina RoennauNo ratings yet

- RTL Assessment 2Document8 pagesRTL Assessment 2api-357684876No ratings yet

- Reconciliation EssayDocument8 pagesReconciliation Essayapi-294443260No ratings yet

- 1 Final AssignmentDocument15 pages1 Final Assignmentapi-473650460No ratings yet

- Assignment 2 Bin Liners Lesson Plan Analysis, Revision and JustificationDocument9 pagesAssignment 2 Bin Liners Lesson Plan Analysis, Revision and Justificationapi-473650460No ratings yet

- A Qualitative Study of Teacher Perspectives of Assessment in STEM EducationDocument19 pagesA Qualitative Study of Teacher Perspectives of Assessment in STEM Educationapi-473650460No ratings yet

- 1 Final AssignmentDocument15 pages1 Final Assignmentapi-473650460No ratings yet

- StudentsResult - 38 - Evening - BS English - ENGL4141 - DGK-BS ENGLISH-EVE - Summative Exam - UExamDocument3 pagesStudentsResult - 38 - Evening - BS English - ENGL4141 - DGK-BS ENGLISH-EVE - Summative Exam - UExamTalhaNo ratings yet

- Strategic Leadership: By: Erica B. ArceDocument20 pagesStrategic Leadership: By: Erica B. ArceBryan B. Arce100% (1)

- Project Scope Management Units 1 To 7Document30 pagesProject Scope Management Units 1 To 7Reshad JoomunNo ratings yet

- Advantage and Disadvantage: Ling Shahrul Amin Fahmi HasifDocument4 pagesAdvantage and Disadvantage: Ling Shahrul Amin Fahmi HasifaminipgNo ratings yet

- ACCT 6621 S1 Syllabus 1Document5 pagesACCT 6621 S1 Syllabus 1Matthew ChristopherNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae: ObjectiveDocument2 pagesCurriculum Vitae: ObjectiveShakir MunhakkalNo ratings yet

- CTU Online InfoDocument4 pagesCTU Online Infojamjayjames3208100% (2)

- Episode 611 Jim KwikDocument52 pagesEpisode 611 Jim KwikKiran James100% (2)

- Walt Whitman Research Paper OutlineDocument5 pagesWalt Whitman Research Paper Outlineltccnaulg100% (1)

- Research Process 11Document12 pagesResearch Process 11Xalu XalManNo ratings yet

- Philosophy of TeachingDocument10 pagesPhilosophy of Teachingapi-508763315No ratings yet

- Nazir Ajmal Memorial College of Education: Hojai (Assam), 782435 B.Ed. Admission: 2020-21 Merit ListDocument22 pagesNazir Ajmal Memorial College of Education: Hojai (Assam), 782435 B.Ed. Admission: 2020-21 Merit ListrakeshNo ratings yet

- CV Layout For DIB Students With Work HistoryDocument6 pagesCV Layout For DIB Students With Work HistoryTìmLạiNo ratings yet

- Speech and Oral CommunicationDocument9 pagesSpeech and Oral CommunicationKaren MolinaNo ratings yet

- Pre Grado Week 2 - Task Assignment - My University Class Sessions Then and NowDocument8 pagesPre Grado Week 2 - Task Assignment - My University Class Sessions Then and NowKathy zzjjjNo ratings yet

- Score SheetDocument1 pageScore SheetDianne Kate NacuaNo ratings yet

- AfL Assignment FinalDocument16 pagesAfL Assignment FinalMontyBilly100% (1)

- DRRM PlanDocument62 pagesDRRM PlanAntartica Antartica75% (4)

- Gender Differences in Career Aspiration Among Public Secondary Schools Students in Nairobi County, KenyaDocument10 pagesGender Differences in Career Aspiration Among Public Secondary Schools Students in Nairobi County, KenyaajmrdNo ratings yet

- Tate Encounters: Britishness and Visual CultureDocument36 pagesTate Encounters: Britishness and Visual CultureMirtes OliveiraNo ratings yet

- EDUC. 6 Module 1Document16 pagesEDUC. 6 Module 1Larry VirayNo ratings yet

- Course Guide-Pe3Document2 pagesCourse Guide-Pe3Macabulos Edgardo SableNo ratings yet

- Sarai M. Alvarez Zepeda: E-Mail: LinkedinDocument4 pagesSarai M. Alvarez Zepeda: E-Mail: Linkedinapi-676558382No ratings yet

- Jadwal Kuliah MKK Periode 30 September 2020Document15 pagesJadwal Kuliah MKK Periode 30 September 2020Edy Anugrah PutraNo ratings yet