Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

33 viewsThe King Vikramaditya

The King Vikramaditya

Uploaded by

nitakuri1. The legend of King Vikramaditya emerged from the consolidation of historical facts and exploits of multiple kings from the 1st century BC to 8th century AD who used the title Vikramaditya.

2. Among these were several Gupta kings from the 4th to 6th century AD who used titles like Sri Vikrama and Vikramaditya, contributing to the legendary figure of Vikramaditya representing the entire Gupta dynasty's achievements.

3. The document discusses how the repetitive use of these titles by successive Gupta kings helped create this legendary figure, noting various kings who used titles like Vikramaditya and Sri Vikrama based on evidence from

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- The Historicity of Vikramaditya and Salivahana1 by K M RaoDocument11 pagesThe Historicity of Vikramaditya and Salivahana1 by K M RaoKosla Vepa100% (4)

- YashovarmanDocument3 pagesYashovarmanGadothkajan BhimNo ratings yet

- Art Integration Social ScienceDocument16 pagesArt Integration Social ScienceSatyajith ReddyNo ratings yet

- Indian History Before British - MHTDocument139 pagesIndian History Before British - MHThevenpapiyaNo ratings yet

- Gupta Dynasty Origin Famous Rulers NCERT Notes PDFDocument4 pagesGupta Dynasty Origin Famous Rulers NCERT Notes PDFAshwini SharmaNo ratings yet

- Guptas Empire: Malvikangimitram, Ritusamhara and Kumarasambhava Provide Reliable InformationDocument9 pagesGuptas Empire: Malvikangimitram, Ritusamhara and Kumarasambhava Provide Reliable InformationBINIT ROYNo ratings yet

- Maurya Incriptions of AshokaDocument20 pagesMaurya Incriptions of Ashokassrini2009No ratings yet

- Gupta Era - Jain Sir LectureDocument32 pagesGupta Era - Jain Sir LectureNayan DhakreNo ratings yet

- Gupta PeriodDocument13 pagesGupta PeriodMs. Renuka CTGNo ratings yet

- Guptas Empire: 1 Download Study Materials On Follow Us On FB For Exam UpdatesDocument5 pagesGuptas Empire: 1 Download Study Materials On Follow Us On FB For Exam UpdatesjackNo ratings yet

- Samudragupta - DhariwalDocument11 pagesSamudragupta - DhariwalArya SahitayaNo ratings yet

- 6 KachaDocument2 pages6 KachaAnshuNo ratings yet

- NCERT Notes Gupta EmpireDocument3 pagesNCERT Notes Gupta EmpireRaghavendra PratapNo ratings yet

- Gupta Empire History NotesDocument8 pagesGupta Empire History NotesSana MariyamNo ratings yet

- Gupta EmpireDocument52 pagesGupta EmpireSahil Raj RavenerNo ratings yet

- Ancient Indian History - Gupta PeriodDocument4 pagesAncient Indian History - Gupta PeriodEkansh DwivediNo ratings yet

- MAHABHARTADocument10 pagesMAHABHARTAPuneet BhushanNo ratings yet

- Gupta Empire (History)Document9 pagesGupta Empire (History)Ravindra SinghNo ratings yet

- Gaha Sattasai 3Document1 pageGaha Sattasai 3RaneNo ratings yet

- Gupta EmpireDocument49 pagesGupta EmpirerohitsaNo ratings yet

- A Theatre of Broken Dreams 2 0 Vidisha IDocument21 pagesA Theatre of Broken Dreams 2 0 Vidisha Imayanklata22No ratings yet

- Kharavela Was A King of Kalinga in Present Day of OdishaDocument18 pagesKharavela Was A King of Kalinga in Present Day of OdishaFlorosia StarshineNo ratings yet

- Vikramaditya As A PoetDocument6 pagesVikramaditya As A PoetElise Rean (Elise Rein)No ratings yet

- Ancient History Notes - Gupta DynastyDocument2 pagesAncient History Notes - Gupta Dynastysteffy deanNo ratings yet

- Gupta Empire PDFDocument59 pagesGupta Empire PDFnishitNo ratings yet

- Kakatiya Dynasty - WikipediaDocument92 pagesKakatiya Dynasty - WikipediajohnNo ratings yet

- Gupta DynastyDocument16 pagesGupta DynastySMRSMRNo ratings yet

- The Gupta AgeDocument5 pagesThe Gupta AgeSiddhant ManchanNo ratings yet

- Chandragupta MauryaDocument23 pagesChandragupta MauryaRicha PandeyNo ratings yet

- The Guptas and VakatakasDocument19 pagesThe Guptas and Vakatakassonishreya0621No ratings yet

- Early History KolhapurDocument3 pagesEarly History KolhapurShivraj WaghNo ratings yet

- Ancient 1Document18 pagesAncient 1akashraizada2023No ratings yet

- Gupta EmpireDocument6 pagesGupta EmpireAshish Rockstar100% (1)

- Date of KalidasaDocument12 pagesDate of Kalidasahari18No ratings yet

- Chandragupta IIDocument3 pagesChandragupta IInilendumishra500No ratings yet

- Jammu & KashmirDocument68 pagesJammu & KashmirHilal Ahmad40% (5)

- Mewar HistoryDocument53 pagesMewar HistoryTheScienceOfTimeNo ratings yet

- Article - Historical Background of The KalachurisDocument4 pagesArticle - Historical Background of The KalachurisMonal BhoyarNo ratings yet

- Kharabela & Gupta DynastyDocument44 pagesKharabela & Gupta Dynasty09whitedevil90No ratings yet

- Mughal Coinage: Coins of The Mughal EmpireDocument6 pagesMughal Coinage: Coins of The Mughal Empiresiva2011mbaNo ratings yet

- Notes of ChronologyDocument18 pagesNotes of ChronologyVidhi SinghNo ratings yet

- Srilankan History Part 3Document1 pageSrilankan History Part 3WISH BOOK SHOP & GROCERYNo ratings yet

- Sr. Kalidas PoetDocument2 pagesSr. Kalidas PoetPalak PathakNo ratings yet

- The Gupta EmpireDocument17 pagesThe Gupta EmpireSyamNo ratings yet

- Classical Period: Gupta Empire (C. 320 - 650 CE) : Main Article: Further Information:, ,, ,,, andDocument3 pagesClassical Period: Gupta Empire (C. 320 - 650 CE) : Main Article: Further Information:, ,, ,,, andAbrogena, Daniela Adiel A.100% (1)

- 322 PDFDocument26 pages322 PDFDeepankar SamajdarNo ratings yet

- Gupta Dynasty History Study MaterialsDocument8 pagesGupta Dynasty History Study MaterialsAliaNo ratings yet

- Notes Chapter 2 Kings Farmers and Towns Early States and EconomiesDocument5 pagesNotes Chapter 2 Kings Farmers and Towns Early States and EconomiesroopmaanroopNo ratings yet

- Saka ERADocument22 pagesSaka ERAChinmay Sukhwal100% (1)

- Conquest of SamudraguptaDocument52 pagesConquest of SamudraguptaOlivia RayNo ratings yet

- Prelims Ancient-HistoryDocument16 pagesPrelims Ancient-Historynikhil dahiyaNo ratings yet

- GuptasDocument39 pagesGuptastnpscmeterial1No ratings yet

- Kharavela: Kharavela (Also Transliterated KhārabēDocument8 pagesKharavela: Kharavela (Also Transliterated KhārabēthwrhwrNo ratings yet

- Post Mauryan DynastiesDocument68 pagesPost Mauryan DynastiesjjNo ratings yet

- Class 12 History Notes Chapter 2Document5 pagesClass 12 History Notes Chapter 2Ahsas 6080No ratings yet

- Chap - 08 Threshold of Regional (Bangladesh Studies)Document22 pagesChap - 08 Threshold of Regional (Bangladesh Studies)jayeedahmed507No ratings yet

- Satavahanas PDFDocument18 pagesSatavahanas PDFAbhinandan SarkarNo ratings yet

- FirstDocument25 pagesFirstRahul KumarNo ratings yet

- The Gupta EmpireDocument4 pagesThe Gupta Empirebansalekansh50% (2)

- HumanDocument3 pagesHumannitakuriNo ratings yet

- In The Late 1980s and Early 1990sDocument25 pagesIn The Late 1980s and Early 1990snitakuriNo ratings yet

- Salvatore Ferragamo Promotes Sustainability With Art and FashionDocument4 pagesSalvatore Ferragamo Promotes Sustainability With Art and FashionnitakuriNo ratings yet

- Mother MaryDocument9 pagesMother MarynitakuriNo ratings yet

- SweatshopDocument3 pagesSweatshopnitakuriNo ratings yet

- Eco Chic The Fashion ParadoxDocument5 pagesEco Chic The Fashion ParadoxnitakuriNo ratings yet

- The Technologies Reinventing Physical RetailDocument7 pagesThe Technologies Reinventing Physical RetailnitakuriNo ratings yet

- Acknowledgements Plates: Chapter-1Document3 pagesAcknowledgements Plates: Chapter-1nitakuriNo ratings yet

- Handbook of Catholic Social Teaching (PDFDrive)Document182 pagesHandbook of Catholic Social Teaching (PDFDrive)nitakuri100% (2)

- Widescreen Escapism at Haute Couture: Tim'S TakeDocument6 pagesWidescreen Escapism at Haute Couture: Tim'S TakenitakuriNo ratings yet

- The Lost Art of Himroo WeavingDocument7 pagesThe Lost Art of Himroo WeavingnitakuriNo ratings yet

- LONDON FASHION WEEK 2022 Ones To WatchDocument3 pagesLONDON FASHION WEEK 2022 Ones To WatchnitakuriNo ratings yet

- Dior Brings Vacation PopDocument5 pagesDior Brings Vacation PopnitakuriNo ratings yet

- Eastern Region: Bengal and OrissaDocument14 pagesEastern Region: Bengal and OrissanitakuriNo ratings yet

- Louis Vuitton Investigates Counterfeit Selling Allegations in China June 9, 2022Document3 pagesLouis Vuitton Investigates Counterfeit Selling Allegations in China June 9, 2022nitakuriNo ratings yet

- Angelo Flaccavento: Said Jonathan Anderson at The Beginning of The WeekDocument7 pagesAngelo Flaccavento: Said Jonathan Anderson at The Beginning of The WeeknitakuriNo ratings yet

- Chapter - 1Document11 pagesChapter - 1nitakuriNo ratings yet

- Discuss in Detail The Costumes of The SatavahanasDocument16 pagesDiscuss in Detail The Costumes of The SatavahanasnitakuriNo ratings yet

- Conclusion: Chapter - 5Document41 pagesConclusion: Chapter - 5nitakuriNo ratings yet

- C 4Document44 pagesC 4nitakuriNo ratings yet

- Unit-4 Lesson 11 PDFDocument10 pagesUnit-4 Lesson 11 PDFnitakuriNo ratings yet

- Unit-4 Lesson 11 PDFDocument10 pagesUnit-4 Lesson 11 PDFnitakuriNo ratings yet

- For 5 Buns of One Single ColourDocument7 pagesFor 5 Buns of One Single ColournitakuriNo ratings yet

- Soft Hawaiian Rolls RecipesDocument6 pagesSoft Hawaiian Rolls Recipesnitakuri100% (1)

- Complete Medieval History MarathonDocument156 pagesComplete Medieval History MarathonManish DhurveNo ratings yet

- Bnba Kks Des 2021.Document753 pagesBnba Kks Des 2021.Muhammad Syaifuddin RosyidiNo ratings yet

- Hampi - In-History of VijayanagaraDocument11 pagesHampi - In-History of VijayanagararamyaNo ratings yet

- Tripartite StruggleDocument15 pagesTripartite StruggleGusto EriolasNo ratings yet

- Ppt-British Empire in IndiaDocument17 pagesPpt-British Empire in IndiaJeesma AntonyNo ratings yet

- College ListDocument2 pagesCollege ListIslamic PointNo ratings yet

- Goyal Brothers Prakashan History Solutions Class 7 Chapter 3 The Turkish InvadersDocument10 pagesGoyal Brothers Prakashan History Solutions Class 7 Chapter 3 The Turkish Invaders2920mannuNo ratings yet

- Unit 3 The, Maratha State System: StructureDocument12 pagesUnit 3 The, Maratha State System: StructureSudarshan Ashok ChaudhariNo ratings yet

- Vijayanagar KingdomDocument77 pagesVijayanagar KingdomShruti KabraNo ratings yet

- Hfs1p1 To p6 Entry Europeans (Edited)Document116 pagesHfs1p1 To p6 Entry Europeans (Edited)Dr AjinathNo ratings yet

- L2Document50 pagesL2Hu ChangNo ratings yet

- Efficient Administrator Chhatrapati Shivaji MaharajDocument2 pagesEfficient Administrator Chhatrapati Shivaji MaharajRaj SharmaNo ratings yet

- Maratha Empire - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument9 pagesMaratha Empire - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaAtul VeerNo ratings yet

- VijayanagaraempireDocument34 pagesVijayanagaraempireSachi SachuNo ratings yet

- 02 The Great Escape VIIDocument5 pages02 The Great Escape VIIshinypinks112No ratings yet

- Revised Address IIA 2014Document18 pagesRevised Address IIA 2014Shubhada EngineeringNo ratings yet

- Medieval Indian HistoryDocument73 pagesMedieval Indian HistoryAnonymous x869mKNo ratings yet

- University of Kerala: First Degree Programme Under CBCS System Fifth Semester BA Degree Examination December 2023Document14 pagesUniversity of Kerala: First Degree Programme Under CBCS System Fifth Semester BA Degree Examination December 2023archana97anilNo ratings yet

- Medieval History Updated-English PrintableDocument67 pagesMedieval History Updated-English Printablembawork793No ratings yet

- Delhi Sultanate PDFDocument300 pagesDelhi Sultanate PDFHarsh SharmaNo ratings yet

- Shouvik Mukhopadhyay Military Organization of The CholasDocument41 pagesShouvik Mukhopadhyay Military Organization of The CholasShouvik Mukhopadhyay100% (1)

- Day 7: Medieval Telangana and The Emergence of Composite Culture-Velama KingdomDocument14 pagesDay 7: Medieval Telangana and The Emergence of Composite Culture-Velama Kingdomramya shagamNo ratings yet

- Byjus Exam Prep Ias Monthly Magazine June 2023 1Document184 pagesByjus Exam Prep Ias Monthly Magazine June 2023 1Street Style StoreNo ratings yet

- About Raja Bhoja: Aysha SadafDocument6 pagesAbout Raja Bhoja: Aysha SadafmohamedNo ratings yet

- Indian History 2Document93 pagesIndian History 2M Teja100% (2)

- Rashtrakuta Dynasty Medieval History of India For UPSCDocument6 pagesRashtrakuta Dynasty Medieval History of India For UPSCashishvermarajdmrNo ratings yet

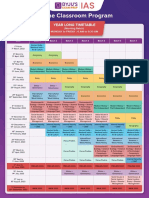

- BHLP Year Long Plan Required English Medium 2023 24 Batch Year Long Timetable 2 961666704096739Document3 pagesBHLP Year Long Plan Required English Medium 2023 24 Batch Year Long Timetable 2 961666704096739Maheshwari Patel NKNo ratings yet

- Centuary 30Document176 pagesCentuary 30Arvind MishraNo ratings yet

- Medieval Indian HistoryDocument90 pagesMedieval Indian HistoryAadi SammetaNo ratings yet

- Delhi Sultanate For WBCSDocument36 pagesDelhi Sultanate For WBCSSAUMYAJIT SABUINo ratings yet

The King Vikramaditya

The King Vikramaditya

Uploaded by

nitakuri0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

33 views5 pages1. The legend of King Vikramaditya emerged from the consolidation of historical facts and exploits of multiple kings from the 1st century BC to 8th century AD who used the title Vikramaditya.

2. Among these were several Gupta kings from the 4th to 6th century AD who used titles like Sri Vikrama and Vikramaditya, contributing to the legendary figure of Vikramaditya representing the entire Gupta dynasty's achievements.

3. The document discusses how the repetitive use of these titles by successive Gupta kings helped create this legendary figure, noting various kings who used titles like Vikramaditya and Sri Vikrama based on evidence from

Original Description:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Document1. The legend of King Vikramaditya emerged from the consolidation of historical facts and exploits of multiple kings from the 1st century BC to 8th century AD who used the title Vikramaditya.

2. Among these were several Gupta kings from the 4th to 6th century AD who used titles like Sri Vikrama and Vikramaditya, contributing to the legendary figure of Vikramaditya representing the entire Gupta dynasty's achievements.

3. The document discusses how the repetitive use of these titles by successive Gupta kings helped create this legendary figure, noting various kings who used titles like Vikramaditya and Sri Vikrama based on evidence from

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

33 views5 pagesThe King Vikramaditya

The King Vikramaditya

Uploaded by

nitakuri1. The legend of King Vikramaditya emerged from the consolidation of historical facts and exploits of multiple kings from the 1st century BC to 8th century AD who used the title Vikramaditya.

2. Among these were several Gupta kings from the 4th to 6th century AD who used titles like Sri Vikrama and Vikramaditya, contributing to the legendary figure of Vikramaditya representing the entire Gupta dynasty's achievements.

3. The document discusses how the repetitive use of these titles by successive Gupta kings helped create this legendary figure, noting various kings who used titles like Vikramaditya and Sri Vikrama based on evidence from

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 5

The King Vikramaditya

The Legendary King Vikramāditya Before we proceed further to study coins

issued by each of the Gupta kings and to better understand the attribution of

coins to specific Gupta kings, it is very important to first and foremost

understand the Legend of the great Indian king Vikramāditya . If you were to

ask ten scholars on Indian history this question - Who was King Vikramāditya? -

You will get ten different answers, and in most cases they would all be partially

correct! The reality is that in the time from the 1st century BC to 8th century

AD, there were many kings who took on the title of Vikramāditya. Some were

major kings who ruled over vast territories, whose domain encompassed vast

tracts of the Indian sub-continent and some were very minor kings who are

mostly known from fleeting references in epigraphs or coins. The memories of

all of these kings synthesized to form a common legendary personality of a

famous Indian king called Vikramāditya whose legends dictated that he was

the Paramabhāgvata - the most devout devotee of Lord Vishnu, Benevolent,

Powerful, Valorous, Charitable, Just and Gifted in the Arts and above all the

Bravest of all the kings.

The earliest use of the name Vikramāditya comes to us from the chief of the

Mālwā tribe of Ujjayinī who is assumed to have initiated the Vikrama Sa vat

(Vikrama era) in 57 BC. However, this Mālwā chief was not big enough or

powerful enough to have been solely accredited with this legendary name. The

actual use of the name 'Vikrama Sa vat' is only first seen in the 9th century AD

in the dated Dhaulpur inscription of King Chandamahasena of 841AD (Goyal

2005: 365-72). However, in this period there ruled one of the greatest

dynasties of India - the Gupta dynasty, which had it's own share of

Vikramādityas! From the 3rd through 6th century AD, multiple Gupta kings

used and reused the titles Śrī Vikrama and Vikramāditya , leading to a

consolidation of the historical facts into the legend of the mighty Vikramāditya

who came to represent not one king but an entire dynasty (Raychaudhuri

1997: 484).

In fact, Goyal suggests that this time period should be called 'The Age of the

Vikramādityas' (Goyal 2005: 367). Raychaudhuri suggested that the

Vikramādityacharita "sums up the historical and traditional achievements of a

dynasty (the Guptas), rather than that of one single individual ruler", a

conclusion I also came to and suggested as such using the coins as examples in

2010 at the Conference on the Gupta Dynasty in Chandigarh. The evolution of

this legend is best seen through the coins issued by the Gupta kings which list

their birudas - the imperial titles on these gold, silver, copper and lead coins

that were widely distributed across northern, western and central India and in

use for approximately 250+ years.

While Chandragupta II is considered as the most famous of the Gupta kings to

have used the titles Śrī Vikrama and Vikramāditya , in fact you will see in the

following pages that this title was used by his grandfather, Chandragupta I,

prior to him as well as many of the later Gupta kings. This fact was mostly

ignored in the past by eminent scholars such as John Allan, A.S. Altekar, P.L.

Gupta, etc., and led each of them to erroneously attribute all coins which

featured the legend Chandra and Śrī Vikrama to just one king: Chandragupta II.

In the following pages you will see coins issued by Chandragupta I,

Samudragupta, Chandragupta II, Kumāragupta I, Skandagupta, Chandragupta

III, Budhagupta, an additional new king known only as Vikramāditya from his

coins, Chandragupta IV, and Vainyagupta, covering a period from 319 AD to

507+ AD, where all of their coins featured biruda, Śrī Vikrama or versions

thereof. Goyal points out that Samudragupta's title Parākramanka also means

Vikramānka or Vikramāditya (Goyal 2005: 242). In addition, the biruda

Vikramāditya was used by both Chandragupta II and Skandagupta on their

coins. We also know of coins issued in the name of Samudragupta and

Kumaragupta I with the biruda Śrī Vikrama on the reverse. Similarly, the

literary works that followed in the coming centuries eulogizing the famous

Gupta kings, added to the confusion by continuing to refer to the different

Gupta monarchs with a singular name, Vikramāditya . The Kathāsaritsāgara

and the Bharatkathāmanjarī narrate the wide conquests of the famous King

Vikramāditya (which matches up quite well with the conquests of

Samudragupta), while the Devi Chandraguptam of Viśaka and the legends

found in Vetālapanchavinśatī and Vikrama-kathā use the title Vikramāditya for

Chandragupta II. Similarly in the Kathāsaritsāgara, the noble King Vikramāditya

is described as the son of King Mahendrāditya (which of course refers to

Skandagupta as son of Kumāragupta I).

The title Śakahari king Vikramāditya applies to Chandragupta II who started the

wars against the Kshatrapa king and also to Kumāragupta I who finally

vanquished the last Kshatrapa king Rudrasi ha III (Goyal 2005: 242).

Skandagupta was the Vikramāditya who was supposed to have vanquished the

revolt from the local Nāgās of eastern Mālwā and Śakas/Vākātākās who had

rebelled against the Guptas after the death of Prabhāvatiguptā in 443AD (more

on this will be discussed ahead; the Invasion by the Hūnas, a possible mis-

characterization of the invasion of the Gupta Empire at the end of

Kumaragupta I's reign). Numismatic evidence shows us that, after the death of

Kumāragupta I, Skandagupta issued silver coins using this Vikramāditya title for

himself on his Garuda Type silver coins, a term that is also used on his Supia

pillar inscription of GE141, and concurrently we see another Chandragupta (III)

who uses the same biruda, Śrī Vikrama (Bhandarkar 1981: 318). To add to the

confusion of the legends, other later Gupta Kings like Budhagupta also use this

same biruda Vikrama . From numismatic evidence we find that two additional

later Vikramādityas that follow: a Hū a king who gives himself the title of

Vikramāditya who issued his coins in the chaotic period after Budhagupta but

before Vainyagupta, and another king using the name Chandragupta (IV)

known from his coins of the Archer Fire Altar Type, who also adopts this same

biruda Śrī Vikrama ! This repetitive use of the epitaphs and titles by successive

Gupta kings helped to create this legend. It is clear that over the span of 241

years, the exploits, conquests and victories, marital alliances, historical facts

and events of the Gupta kings all merged into one common legend - the legend

of the powerful king called Vikramāditya . Even after the end of the Gupta

Empire, the title of Vikramāditya was resurrected for Har avardhana (606-647

AD) as chronicled in the Kashmiri text Rājatara gi ī (Stein 1900).

Over the last century, scholars have used the royal titles, biruda's and epitaphs

to make their case of whether a king was in a position to issue coins. A detailed

study of the titles, names, biruda's and epithets used for the Gupta kings

shows us that the Gupta kings did not limit themselves to a singular title as is

the general belief, but rather freely used the most appropriate title or epithet

that suited the occasion. While it is generally assumed that Samudragupta's

biruda was Parākrama and Chandragupta II's biruda was Śrī Vikrama it will be

seen that they were not limited to just these singular titles. Similarly, the

greatest of the Gupta kings, Samudragupta, is given all of these royal

designations: Rājā, Mahārājā, Mahārājādhirāja, as seen in inscriptions and coin

legends. If Rājā and Mahārājā can be used for the mighty Samudragupta, then

why is it assumed that his grandfather, Mahārāja Śrīgupta was just a petty king

who had used the title Rajña? According to Altekar he "was too insignificant to

issue any coinage"! (Altekar 1957: 2), an assertion that is wrong.

Another example of the importance of titles and birudas is the case of

Rāmagupta. He was assumed by scholars to have never ruled as a Gupta king,

till the Jaina sculptures were discovered with inscriptions listing his title as a

Mahārājādhirāja (Gai 1968-69: 250-251). The epigraphical data from the Jain

sculptures clearly confirms that he had assumed the title of a Mahārājādhirāja

a "King of Kings" and finally included him into the list of known Gupta kings.

The identity of Kāchagupta has been debated for the past century with almost

every major Gupta historian offering their opinions: Princep and Rapson

ascribed these coins to Ghatotkacha, Vincent Smith kept changing his views,

Allan, Fleet and Raychaudhuri thought he was the same as Samudragupta,

Bhandarkar thought he was same as Rāmagupta but changed his view later,

Banerji and P.L. Gupta thought he was a brother of Samudragupta (Allan

1914/1967: xxxiii-iv, Fleet 1888: 27, Joshi 1992). The reality is that all of these

debates were strictly conjecture. None of the proposed attributions was based

on evidence. This question of the identity of this king is addressed later in the

book where the coins of Rāmagupta-Kāchagupta are discussed in detail to

prove that both of them were one and the same person. There are many such

quandaries one has to consider when trying to walk through the maze of the

history of ancient India. Our interpretation of the data is only as good as the

next new piece of information that comes to light through new inscriptions,

seals or coins.

The tables in the following pages attempts to summarize the titles, biruda's

and epithets as used for/by the Gupta kings on Inscriptions, seals and sealings,

coins and copper-plates. It will show that so many of the arguments proposed

over the years can be struck down just by a simple review of these tables. The

problem with assuming that a single title applied to a single King has led many

scholars and historians to errant conclusions. For example, the use of

Sarvarājochchhettā as an epithet (assumed by scholars and historians to have

been only used by Samudragupta) seemed to be the reason for scholars to

argue that Kācha coins should be attributed to Samudragupta (instead to the

King Kāchagupta). However, as shown in the biruda table, this epitaph was not

exclusive to just Samudragupta but also used for Chandragupta II, in the Poona

copper plates of Prabhāvatiguptā where on line 5 she uses this title to refer to

her father (Mirashi 1963: 7). Altekar's argument was that the Poona plates

were not "official" gupta records and hence they should be rejected (Altekar

1967), a weak argument as official Vākātākās inscriptions should be considered

as reliable as official Gupta inscriptions, especially one written by

Chandragupta II’s own daughter Prabhāvatiguptā.

In William Shakespeare’s play Romeo and Juliet, Juliet's line "What’s in a

name? That which we call a rose, by any other name would smell as sweet"

encapsulates perfectly what the legend of the title Vikramāditya meant to the

common man in ancient India. It was not just a name but also a title that

immediately signified a king who was a brilliant, courageous, faithful and

devout, fearless, and powerful, and above all a statesman who united the land

You might also like

- The Historicity of Vikramaditya and Salivahana1 by K M RaoDocument11 pagesThe Historicity of Vikramaditya and Salivahana1 by K M RaoKosla Vepa100% (4)

- YashovarmanDocument3 pagesYashovarmanGadothkajan BhimNo ratings yet

- Art Integration Social ScienceDocument16 pagesArt Integration Social ScienceSatyajith ReddyNo ratings yet

- Indian History Before British - MHTDocument139 pagesIndian History Before British - MHThevenpapiyaNo ratings yet

- Gupta Dynasty Origin Famous Rulers NCERT Notes PDFDocument4 pagesGupta Dynasty Origin Famous Rulers NCERT Notes PDFAshwini SharmaNo ratings yet

- Guptas Empire: Malvikangimitram, Ritusamhara and Kumarasambhava Provide Reliable InformationDocument9 pagesGuptas Empire: Malvikangimitram, Ritusamhara and Kumarasambhava Provide Reliable InformationBINIT ROYNo ratings yet

- Maurya Incriptions of AshokaDocument20 pagesMaurya Incriptions of Ashokassrini2009No ratings yet

- Gupta Era - Jain Sir LectureDocument32 pagesGupta Era - Jain Sir LectureNayan DhakreNo ratings yet

- Gupta PeriodDocument13 pagesGupta PeriodMs. Renuka CTGNo ratings yet

- Guptas Empire: 1 Download Study Materials On Follow Us On FB For Exam UpdatesDocument5 pagesGuptas Empire: 1 Download Study Materials On Follow Us On FB For Exam UpdatesjackNo ratings yet

- Samudragupta - DhariwalDocument11 pagesSamudragupta - DhariwalArya SahitayaNo ratings yet

- 6 KachaDocument2 pages6 KachaAnshuNo ratings yet

- NCERT Notes Gupta EmpireDocument3 pagesNCERT Notes Gupta EmpireRaghavendra PratapNo ratings yet

- Gupta Empire History NotesDocument8 pagesGupta Empire History NotesSana MariyamNo ratings yet

- Gupta EmpireDocument52 pagesGupta EmpireSahil Raj RavenerNo ratings yet

- Ancient Indian History - Gupta PeriodDocument4 pagesAncient Indian History - Gupta PeriodEkansh DwivediNo ratings yet

- MAHABHARTADocument10 pagesMAHABHARTAPuneet BhushanNo ratings yet

- Gupta Empire (History)Document9 pagesGupta Empire (History)Ravindra SinghNo ratings yet

- Gaha Sattasai 3Document1 pageGaha Sattasai 3RaneNo ratings yet

- Gupta EmpireDocument49 pagesGupta EmpirerohitsaNo ratings yet

- A Theatre of Broken Dreams 2 0 Vidisha IDocument21 pagesA Theatre of Broken Dreams 2 0 Vidisha Imayanklata22No ratings yet

- Kharavela Was A King of Kalinga in Present Day of OdishaDocument18 pagesKharavela Was A King of Kalinga in Present Day of OdishaFlorosia StarshineNo ratings yet

- Vikramaditya As A PoetDocument6 pagesVikramaditya As A PoetElise Rean (Elise Rein)No ratings yet

- Ancient History Notes - Gupta DynastyDocument2 pagesAncient History Notes - Gupta Dynastysteffy deanNo ratings yet

- Gupta Empire PDFDocument59 pagesGupta Empire PDFnishitNo ratings yet

- Kakatiya Dynasty - WikipediaDocument92 pagesKakatiya Dynasty - WikipediajohnNo ratings yet

- Gupta DynastyDocument16 pagesGupta DynastySMRSMRNo ratings yet

- The Gupta AgeDocument5 pagesThe Gupta AgeSiddhant ManchanNo ratings yet

- Chandragupta MauryaDocument23 pagesChandragupta MauryaRicha PandeyNo ratings yet

- The Guptas and VakatakasDocument19 pagesThe Guptas and Vakatakassonishreya0621No ratings yet

- Early History KolhapurDocument3 pagesEarly History KolhapurShivraj WaghNo ratings yet

- Ancient 1Document18 pagesAncient 1akashraizada2023No ratings yet

- Gupta EmpireDocument6 pagesGupta EmpireAshish Rockstar100% (1)

- Date of KalidasaDocument12 pagesDate of Kalidasahari18No ratings yet

- Chandragupta IIDocument3 pagesChandragupta IInilendumishra500No ratings yet

- Jammu & KashmirDocument68 pagesJammu & KashmirHilal Ahmad40% (5)

- Mewar HistoryDocument53 pagesMewar HistoryTheScienceOfTimeNo ratings yet

- Article - Historical Background of The KalachurisDocument4 pagesArticle - Historical Background of The KalachurisMonal BhoyarNo ratings yet

- Kharabela & Gupta DynastyDocument44 pagesKharabela & Gupta Dynasty09whitedevil90No ratings yet

- Mughal Coinage: Coins of The Mughal EmpireDocument6 pagesMughal Coinage: Coins of The Mughal Empiresiva2011mbaNo ratings yet

- Notes of ChronologyDocument18 pagesNotes of ChronologyVidhi SinghNo ratings yet

- Srilankan History Part 3Document1 pageSrilankan History Part 3WISH BOOK SHOP & GROCERYNo ratings yet

- Sr. Kalidas PoetDocument2 pagesSr. Kalidas PoetPalak PathakNo ratings yet

- The Gupta EmpireDocument17 pagesThe Gupta EmpireSyamNo ratings yet

- Classical Period: Gupta Empire (C. 320 - 650 CE) : Main Article: Further Information:, ,, ,,, andDocument3 pagesClassical Period: Gupta Empire (C. 320 - 650 CE) : Main Article: Further Information:, ,, ,,, andAbrogena, Daniela Adiel A.100% (1)

- 322 PDFDocument26 pages322 PDFDeepankar SamajdarNo ratings yet

- Gupta Dynasty History Study MaterialsDocument8 pagesGupta Dynasty History Study MaterialsAliaNo ratings yet

- Notes Chapter 2 Kings Farmers and Towns Early States and EconomiesDocument5 pagesNotes Chapter 2 Kings Farmers and Towns Early States and EconomiesroopmaanroopNo ratings yet

- Saka ERADocument22 pagesSaka ERAChinmay Sukhwal100% (1)

- Conquest of SamudraguptaDocument52 pagesConquest of SamudraguptaOlivia RayNo ratings yet

- Prelims Ancient-HistoryDocument16 pagesPrelims Ancient-Historynikhil dahiyaNo ratings yet

- GuptasDocument39 pagesGuptastnpscmeterial1No ratings yet

- Kharavela: Kharavela (Also Transliterated KhārabēDocument8 pagesKharavela: Kharavela (Also Transliterated KhārabēthwrhwrNo ratings yet

- Post Mauryan DynastiesDocument68 pagesPost Mauryan DynastiesjjNo ratings yet

- Class 12 History Notes Chapter 2Document5 pagesClass 12 History Notes Chapter 2Ahsas 6080No ratings yet

- Chap - 08 Threshold of Regional (Bangladesh Studies)Document22 pagesChap - 08 Threshold of Regional (Bangladesh Studies)jayeedahmed507No ratings yet

- Satavahanas PDFDocument18 pagesSatavahanas PDFAbhinandan SarkarNo ratings yet

- FirstDocument25 pagesFirstRahul KumarNo ratings yet

- The Gupta EmpireDocument4 pagesThe Gupta Empirebansalekansh50% (2)

- HumanDocument3 pagesHumannitakuriNo ratings yet

- In The Late 1980s and Early 1990sDocument25 pagesIn The Late 1980s and Early 1990snitakuriNo ratings yet

- Salvatore Ferragamo Promotes Sustainability With Art and FashionDocument4 pagesSalvatore Ferragamo Promotes Sustainability With Art and FashionnitakuriNo ratings yet

- Mother MaryDocument9 pagesMother MarynitakuriNo ratings yet

- SweatshopDocument3 pagesSweatshopnitakuriNo ratings yet

- Eco Chic The Fashion ParadoxDocument5 pagesEco Chic The Fashion ParadoxnitakuriNo ratings yet

- The Technologies Reinventing Physical RetailDocument7 pagesThe Technologies Reinventing Physical RetailnitakuriNo ratings yet

- Acknowledgements Plates: Chapter-1Document3 pagesAcknowledgements Plates: Chapter-1nitakuriNo ratings yet

- Handbook of Catholic Social Teaching (PDFDrive)Document182 pagesHandbook of Catholic Social Teaching (PDFDrive)nitakuri100% (2)

- Widescreen Escapism at Haute Couture: Tim'S TakeDocument6 pagesWidescreen Escapism at Haute Couture: Tim'S TakenitakuriNo ratings yet

- The Lost Art of Himroo WeavingDocument7 pagesThe Lost Art of Himroo WeavingnitakuriNo ratings yet

- LONDON FASHION WEEK 2022 Ones To WatchDocument3 pagesLONDON FASHION WEEK 2022 Ones To WatchnitakuriNo ratings yet

- Dior Brings Vacation PopDocument5 pagesDior Brings Vacation PopnitakuriNo ratings yet

- Eastern Region: Bengal and OrissaDocument14 pagesEastern Region: Bengal and OrissanitakuriNo ratings yet

- Louis Vuitton Investigates Counterfeit Selling Allegations in China June 9, 2022Document3 pagesLouis Vuitton Investigates Counterfeit Selling Allegations in China June 9, 2022nitakuriNo ratings yet

- Angelo Flaccavento: Said Jonathan Anderson at The Beginning of The WeekDocument7 pagesAngelo Flaccavento: Said Jonathan Anderson at The Beginning of The WeeknitakuriNo ratings yet

- Chapter - 1Document11 pagesChapter - 1nitakuriNo ratings yet

- Discuss in Detail The Costumes of The SatavahanasDocument16 pagesDiscuss in Detail The Costumes of The SatavahanasnitakuriNo ratings yet

- Conclusion: Chapter - 5Document41 pagesConclusion: Chapter - 5nitakuriNo ratings yet

- C 4Document44 pagesC 4nitakuriNo ratings yet

- Unit-4 Lesson 11 PDFDocument10 pagesUnit-4 Lesson 11 PDFnitakuriNo ratings yet

- Unit-4 Lesson 11 PDFDocument10 pagesUnit-4 Lesson 11 PDFnitakuriNo ratings yet

- For 5 Buns of One Single ColourDocument7 pagesFor 5 Buns of One Single ColournitakuriNo ratings yet

- Soft Hawaiian Rolls RecipesDocument6 pagesSoft Hawaiian Rolls Recipesnitakuri100% (1)

- Complete Medieval History MarathonDocument156 pagesComplete Medieval History MarathonManish DhurveNo ratings yet

- Bnba Kks Des 2021.Document753 pagesBnba Kks Des 2021.Muhammad Syaifuddin RosyidiNo ratings yet

- Hampi - In-History of VijayanagaraDocument11 pagesHampi - In-History of VijayanagararamyaNo ratings yet

- Tripartite StruggleDocument15 pagesTripartite StruggleGusto EriolasNo ratings yet

- Ppt-British Empire in IndiaDocument17 pagesPpt-British Empire in IndiaJeesma AntonyNo ratings yet

- College ListDocument2 pagesCollege ListIslamic PointNo ratings yet

- Goyal Brothers Prakashan History Solutions Class 7 Chapter 3 The Turkish InvadersDocument10 pagesGoyal Brothers Prakashan History Solutions Class 7 Chapter 3 The Turkish Invaders2920mannuNo ratings yet

- Unit 3 The, Maratha State System: StructureDocument12 pagesUnit 3 The, Maratha State System: StructureSudarshan Ashok ChaudhariNo ratings yet

- Vijayanagar KingdomDocument77 pagesVijayanagar KingdomShruti KabraNo ratings yet

- Hfs1p1 To p6 Entry Europeans (Edited)Document116 pagesHfs1p1 To p6 Entry Europeans (Edited)Dr AjinathNo ratings yet

- L2Document50 pagesL2Hu ChangNo ratings yet

- Efficient Administrator Chhatrapati Shivaji MaharajDocument2 pagesEfficient Administrator Chhatrapati Shivaji MaharajRaj SharmaNo ratings yet

- Maratha Empire - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument9 pagesMaratha Empire - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaAtul VeerNo ratings yet

- VijayanagaraempireDocument34 pagesVijayanagaraempireSachi SachuNo ratings yet

- 02 The Great Escape VIIDocument5 pages02 The Great Escape VIIshinypinks112No ratings yet

- Revised Address IIA 2014Document18 pagesRevised Address IIA 2014Shubhada EngineeringNo ratings yet

- Medieval Indian HistoryDocument73 pagesMedieval Indian HistoryAnonymous x869mKNo ratings yet

- University of Kerala: First Degree Programme Under CBCS System Fifth Semester BA Degree Examination December 2023Document14 pagesUniversity of Kerala: First Degree Programme Under CBCS System Fifth Semester BA Degree Examination December 2023archana97anilNo ratings yet

- Medieval History Updated-English PrintableDocument67 pagesMedieval History Updated-English Printablembawork793No ratings yet

- Delhi Sultanate PDFDocument300 pagesDelhi Sultanate PDFHarsh SharmaNo ratings yet

- Shouvik Mukhopadhyay Military Organization of The CholasDocument41 pagesShouvik Mukhopadhyay Military Organization of The CholasShouvik Mukhopadhyay100% (1)

- Day 7: Medieval Telangana and The Emergence of Composite Culture-Velama KingdomDocument14 pagesDay 7: Medieval Telangana and The Emergence of Composite Culture-Velama Kingdomramya shagamNo ratings yet

- Byjus Exam Prep Ias Monthly Magazine June 2023 1Document184 pagesByjus Exam Prep Ias Monthly Magazine June 2023 1Street Style StoreNo ratings yet

- About Raja Bhoja: Aysha SadafDocument6 pagesAbout Raja Bhoja: Aysha SadafmohamedNo ratings yet

- Indian History 2Document93 pagesIndian History 2M Teja100% (2)

- Rashtrakuta Dynasty Medieval History of India For UPSCDocument6 pagesRashtrakuta Dynasty Medieval History of India For UPSCashishvermarajdmrNo ratings yet

- BHLP Year Long Plan Required English Medium 2023 24 Batch Year Long Timetable 2 961666704096739Document3 pagesBHLP Year Long Plan Required English Medium 2023 24 Batch Year Long Timetable 2 961666704096739Maheshwari Patel NKNo ratings yet

- Centuary 30Document176 pagesCentuary 30Arvind MishraNo ratings yet

- Medieval Indian HistoryDocument90 pagesMedieval Indian HistoryAadi SammetaNo ratings yet

- Delhi Sultanate For WBCSDocument36 pagesDelhi Sultanate For WBCSSAUMYAJIT SABUINo ratings yet