Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0%(1)0% found this document useful (1 vote)

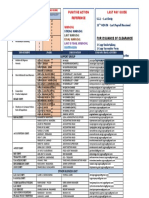

22 viewsThe Maths of Beauty: Insight Intermediate Workbook Unit

The Maths of Beauty: Insight Intermediate Workbook Unit

Uploaded by

Patrycja TruchanowiczCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5820)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Principles of Marketing Chapter 7 NotesDocument12 pagesPrinciples of Marketing Chapter 7 Notessam williamNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Celebrating PartnershipDocument49 pagesCelebrating PartnershipMirela BitoiNo ratings yet

- Plan TheoryDocument121 pagesPlan TheoryW C VETSCH100% (3)

- 14th Annual State of Agile Report PDFDocument19 pages14th Annual State of Agile Report PDFHarold GómezNo ratings yet

- Cannabis and Mental HealthDocument8 pagesCannabis and Mental HealthalinaneagoeNo ratings yet

- Android Application To Read and Record Data From Multiple SensorsDocument8 pagesAndroid Application To Read and Record Data From Multiple SensorsRanjitha RNo ratings yet

- COMPARATIVES AND SUPERLATIVES With ANSWERSDocument4 pagesCOMPARATIVES AND SUPERLATIVES With ANSWERSDaria SesinaNo ratings yet

- Educational Tour Narrative ReportDocument4 pagesEducational Tour Narrative ReportAirs Cg67% (3)

- Eapp Group 2 Concept PaperDocument43 pagesEapp Group 2 Concept PaperVICTOR, KATHLEEN CLARISS B.No ratings yet

- Walter Benjamin Goethes Elective AffinitiesDocument33 pagesWalter Benjamin Goethes Elective AffinitiesAaron Schuster SchusterNo ratings yet

- Comparative Water Requirements For Rice Irrigation Using FAO-CROPWAT MODEL-Case Study-Cross River Basin - 270219 Rev9Document78 pagesComparative Water Requirements For Rice Irrigation Using FAO-CROPWAT MODEL-Case Study-Cross River Basin - 270219 Rev9Engr Evans OhajiNo ratings yet

- Stereochemistry Practce PDFDocument6 pagesStereochemistry Practce PDFFerminNo ratings yet

- SOMF 2.1 Conceptualization Model Language SpecificationsDocument27 pagesSOMF 2.1 Conceptualization Model Language SpecificationsMelina NancyNo ratings yet

- LECTURE 2 England As A Constituent Unit of The UnitedDocument26 pagesLECTURE 2 England As A Constituent Unit of The UnitedOlyamnoleNo ratings yet

- Answer For Inference Worksheet 1Document4 pagesAnswer For Inference Worksheet 1najwa najihahNo ratings yet

- DDocument28 pagesDkle3nexNo ratings yet

- Messages To Pastor EnocDocument3 pagesMessages To Pastor EnocpgmessageNo ratings yet

- Mapeh 10 1 Grading Examination: E. Modern NationalismDocument3 pagesMapeh 10 1 Grading Examination: E. Modern NationalismMildred Abad SarmientoNo ratings yet

- World Journal On Educational Technology: Current IssuesDocument12 pagesWorld Journal On Educational Technology: Current IssuesBelay HaileNo ratings yet

- Lab Act FinalsDocument4 pagesLab Act FinalstaiyuraijinNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Department of Education Region XI Atty. Orlando S. Rimando National High School Binuangan, Maco Compostela ValleyDocument26 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Department of Education Region XI Atty. Orlando S. Rimando National High School Binuangan, Maco Compostela ValleyNur-aine Londa HajijulNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1 Speaking (f1)Document1 pageLesson 1 Speaking (f1)Siti HaidaNo ratings yet

- ĐỀ SỐ 24Document18 pagesĐỀ SỐ 2411 Nguyễn Quang HàNo ratings yet

- Guide MeDocument1 pageGuide MeAllan Amante Jr.No ratings yet

- Grade 1 Mid Term Assessment Report 2023Document4 pagesGrade 1 Mid Term Assessment Report 2023KISAKYE ANTHONYNo ratings yet

- Comprender Frases y Vocabulario Habitual Sobre Temas de Interés Personal y Temas TécnicosDocument2 pagesComprender Frases y Vocabulario Habitual Sobre Temas de Interés Personal y Temas TécnicosPaoliitha PteNo ratings yet

- La Ilaha IlallahDocument3 pagesLa Ilaha Ilallahtawhide_islamic100% (1)

- COVID 19 Vaccine Clinical Guidance Rheumatic Diseases SummaryDocument6 pagesCOVID 19 Vaccine Clinical Guidance Rheumatic Diseases SummarySiamakNo ratings yet

- Sap Ecc 6.0: DMO For Using SUM 1.0 SP 23Document2 pagesSap Ecc 6.0: DMO For Using SUM 1.0 SP 23Yolman CalderonNo ratings yet

- Communication and GlobalizationDocument14 pagesCommunication and GlobalizationJOHN LEE VALDEZNo ratings yet

The Maths of Beauty: Insight Intermediate Workbook Unit

The Maths of Beauty: Insight Intermediate Workbook Unit

Uploaded by

Patrycja Truchanowicz0%(1)0% found this document useful (1 vote)

22 views3 pagesOriginal Title

a002003_insight_int_wb_dfrt_unit1 (1).pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0%(1)0% found this document useful (1 vote)

22 views3 pagesThe Maths of Beauty: Insight Intermediate Workbook Unit

The Maths of Beauty: Insight Intermediate Workbook Unit

Uploaded by

Patrycja TruchanowiczCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 3

The maths of beauty

It’s often said that ‘beauty is in the eye of the

beholder,’ and our ideas of attractiveness

certainly depend on personal preferences.

Nevertheless, there are faces which most

people agree are very beautiful or handsome.

Is this something that we just feel about

a certain face, or does it mean that there

are ‘rules’ for what makes someone look

beautiful?

It was long thought that symmetry was the key to explaining A

beauty. If the two halves of a face are symmetrical, we find

it pleasing. There is also a deeper reason why symmetry is

desirable to someone looking for a partner of the opposite

sex, especially when a girl is looking for a boy. A symmetrical

face and body suggests that someone’s genes must be in

very good condition, and that their children will be strong

and healthy.

insight Intermediate Workbook Unit 1 pp.8–9 © Oxford University Press 2014 1

Increasing amounts of symmetry enhance the attractiveness B

of a face, but recent experiments have revealed that there

is a limit to this. When one side of a person’s face is used

in a mirror image in a photograph to make a perfectly

symmetrical face, the result can make us feel uneasy

(photo B). It seems too unnatural, and we even begin to find

it unattractive.

For a better explanation of what makes a face appear ideal, C

we need to enter the world of mathematics. The Greek

mathematician Euclid developed his theory of the ‘golden

ratio’ in 300 BC. He saw that if you measure different parts

of many of the things we find beautiful in nature – flowers

and sea shells for example – and divide the measurements

by each other, you keep finding the same ratio. This golden

ratio is 1.62. It was used when the Greeks designed the

Parthenon in Athens, which is considered to be one of the

most perfect buildings ever built.

Leonardo Da Vinci used the golden ratio in the lengths D

of each part of the body of his perfect man, and when

he painted the Mona Lisa. The ratio is easily found when

measuring the different parts of a beautiful face. If the

height of a face divided by its width comes to 1.62, it will

be seen as perfectly shaped. If the distance from the top of

the head to the pupils of the eyes, divided by the distance

from the pupils to the lips is 1.62, that is also perfect. The

ideal width of the central teeth compared to the next teeth?

1.62. There are numerous opportunities for the golden ratio

to appear in a face. Dr Stephen Marquardt, a surgeon,

developed a ‘mask’ that can be put on top of a photo of a

face to show how close it comes to ‘perfect beauty.’

insight Intermediate Workbook Unit 1 pp.8–9 © Oxford University Press 2014 2

The golden ratio is so powerful that it appears to work

across cultures and across time. Queen Nefertiti of ancient

Egypt (photo C) was clearly just as successful an example of

the golden ratio as Angelina Jolie is today (photo D). And

although different cultures show strong preferences for

particular eye and hair colours in their ideals of beauty, the

impact of the golden ratio is the same for both men and

women.

Magazines know all about this of course, and photographs

of beautiful models are usually manipulated to appear even

more beautiful by moving the nose, or an eye, a millimetre

across, up or down. And there are apps which allow you to

upload a photograph and get a score for how closely a face

matches the golden ratio. Don’t be too disappointed if your

score seems low, though. No one is perfect, and of course,

there are people with asymmetrical faces and less than

golden ratios who many people find incredibly attractive!

The full number, called phi, is similar to the better

known number pi – neither can be fully calculated.

Phi is actually 1.6180339887… never-ending.

A002003

insight Intermediate Workbook Unit 1 pp.8–9 © Oxford University Press 2014 3

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5820)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Principles of Marketing Chapter 7 NotesDocument12 pagesPrinciples of Marketing Chapter 7 Notessam williamNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Celebrating PartnershipDocument49 pagesCelebrating PartnershipMirela BitoiNo ratings yet

- Plan TheoryDocument121 pagesPlan TheoryW C VETSCH100% (3)

- 14th Annual State of Agile Report PDFDocument19 pages14th Annual State of Agile Report PDFHarold GómezNo ratings yet

- Cannabis and Mental HealthDocument8 pagesCannabis and Mental HealthalinaneagoeNo ratings yet

- Android Application To Read and Record Data From Multiple SensorsDocument8 pagesAndroid Application To Read and Record Data From Multiple SensorsRanjitha RNo ratings yet

- COMPARATIVES AND SUPERLATIVES With ANSWERSDocument4 pagesCOMPARATIVES AND SUPERLATIVES With ANSWERSDaria SesinaNo ratings yet

- Educational Tour Narrative ReportDocument4 pagesEducational Tour Narrative ReportAirs Cg67% (3)

- Eapp Group 2 Concept PaperDocument43 pagesEapp Group 2 Concept PaperVICTOR, KATHLEEN CLARISS B.No ratings yet

- Walter Benjamin Goethes Elective AffinitiesDocument33 pagesWalter Benjamin Goethes Elective AffinitiesAaron Schuster SchusterNo ratings yet

- Comparative Water Requirements For Rice Irrigation Using FAO-CROPWAT MODEL-Case Study-Cross River Basin - 270219 Rev9Document78 pagesComparative Water Requirements For Rice Irrigation Using FAO-CROPWAT MODEL-Case Study-Cross River Basin - 270219 Rev9Engr Evans OhajiNo ratings yet

- Stereochemistry Practce PDFDocument6 pagesStereochemistry Practce PDFFerminNo ratings yet

- SOMF 2.1 Conceptualization Model Language SpecificationsDocument27 pagesSOMF 2.1 Conceptualization Model Language SpecificationsMelina NancyNo ratings yet

- LECTURE 2 England As A Constituent Unit of The UnitedDocument26 pagesLECTURE 2 England As A Constituent Unit of The UnitedOlyamnoleNo ratings yet

- Answer For Inference Worksheet 1Document4 pagesAnswer For Inference Worksheet 1najwa najihahNo ratings yet

- DDocument28 pagesDkle3nexNo ratings yet

- Messages To Pastor EnocDocument3 pagesMessages To Pastor EnocpgmessageNo ratings yet

- Mapeh 10 1 Grading Examination: E. Modern NationalismDocument3 pagesMapeh 10 1 Grading Examination: E. Modern NationalismMildred Abad SarmientoNo ratings yet

- World Journal On Educational Technology: Current IssuesDocument12 pagesWorld Journal On Educational Technology: Current IssuesBelay HaileNo ratings yet

- Lab Act FinalsDocument4 pagesLab Act FinalstaiyuraijinNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Department of Education Region XI Atty. Orlando S. Rimando National High School Binuangan, Maco Compostela ValleyDocument26 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Department of Education Region XI Atty. Orlando S. Rimando National High School Binuangan, Maco Compostela ValleyNur-aine Londa HajijulNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1 Speaking (f1)Document1 pageLesson 1 Speaking (f1)Siti HaidaNo ratings yet

- ĐỀ SỐ 24Document18 pagesĐỀ SỐ 2411 Nguyễn Quang HàNo ratings yet

- Guide MeDocument1 pageGuide MeAllan Amante Jr.No ratings yet

- Grade 1 Mid Term Assessment Report 2023Document4 pagesGrade 1 Mid Term Assessment Report 2023KISAKYE ANTHONYNo ratings yet

- Comprender Frases y Vocabulario Habitual Sobre Temas de Interés Personal y Temas TécnicosDocument2 pagesComprender Frases y Vocabulario Habitual Sobre Temas de Interés Personal y Temas TécnicosPaoliitha PteNo ratings yet

- La Ilaha IlallahDocument3 pagesLa Ilaha Ilallahtawhide_islamic100% (1)

- COVID 19 Vaccine Clinical Guidance Rheumatic Diseases SummaryDocument6 pagesCOVID 19 Vaccine Clinical Guidance Rheumatic Diseases SummarySiamakNo ratings yet

- Sap Ecc 6.0: DMO For Using SUM 1.0 SP 23Document2 pagesSap Ecc 6.0: DMO For Using SUM 1.0 SP 23Yolman CalderonNo ratings yet

- Communication and GlobalizationDocument14 pagesCommunication and GlobalizationJOHN LEE VALDEZNo ratings yet