Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Hungarian Rom (Gypsy) Political Activism and The Development of Folklór Ensemble Music

Hungarian Rom (Gypsy) Political Activism and The Development of Folklór Ensemble Music

Uploaded by

zibilumOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Hungarian Rom (Gypsy) Political Activism and The Development of Folklór Ensemble Music

Hungarian Rom (Gypsy) Political Activism and The Development of Folklór Ensemble Music

Uploaded by

zibilumCopyright:

Available Formats

Hungarian Rom (Gypsy) Political Activism and the Development of Folklór Ensemble

Music

Author(s): Barbara Rose Lange

Source: The World of Music , 1997, Vol. 39, No. 3 (1997), pp. 5-30

Published by: VWB - Verlag für Wissenschaft und Bildung

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41699162

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

, and are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The World of

Music

This content downloaded from

157.181.112.231 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 09:47:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

the world of music 39(3) - 1997: 5-30

Hungarian Rom (Gypsy) Political Activism and the

Development of Folklór Ensemble Music

Barbara Rose Lange

Abstract

In socialist Hungary there were many negative conceptions of Rom (Gypsy) culture ,

exacerbated by a state policy of assimilation. Starting in the 1970s , Roma established

folklór ensembles whose repertoire was based on rural family singing and dance.

Folklór ensembles asserted artistic value for Rom music and served as a means of in-

dependent political development.

During the last decades of the socialist period in Hungary, Roma (Gypsies) devel-

oped a new stage genre which they called folklór ensemble music. In order to be em-

braced both by Roma and Hungarians as a legitimate art form, this music had to

counteract a high degree of stigma. Several seemingly disparate factors combined to

give folklór ensemble music its capacity to redefine Rom cultural expression. These

included increasing activist sentiment on the part of Roma, the humanistic orienta-

tion of some Hungarian intellectuals, and coercive state social policies. Observations

made by folklór ensemble participants reveal that this music was- and continues to

be- significant as a form of political expression. At the same time, folklór perfor-

mances were tailored to contradict negative assumptions that Hungarian audiences

possessed about Rom singing. Folklór music came to be viewed by Roma and non-

Roma alike as an expression of both the uniqueness and aesthetic value of Rom cul-

ture in Hungary.1

This essay takes as its primary sources the recollections of leaders of early folklór

groups and observations on folklór music made by ensemble participants who were

active during the time I conducted fieldwork in the early 1990s. Their opinions also

appear in publications produced under Rom editorial direction during the late and

post-socialist periods. The method of incorporating several individual viewpoints in

musical ethnography has shown ever-deeper cycles of understanding between the

subjects (Rice 1994), complex operational modes of interpretation (Titon 1988), and

contrasting knowledges based on the experience of performing (Chernoff 1979). It

also has the potential to contradict a tendency towards erasure inherent in writing

about subaltern peoples like Roma and East Europeans in general. The reflections of

This content downloaded from

157.181.112.231 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 09:47:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

6 • the world of music 39(3)- 1997

folklór musicians emphasize the degree of persistence and innovation that was re-

quired in order to create a new order of society in the late socialist period. Obtaining

initial public and institutional acceptance for folklór ensembles and music required

interethnic cooperation, individual commitment, and choices to alter musical sound.

1. Development of Folklór Music

Folklór music consists of songs in several dialects of the languages spoken by Roma

in Hungary, arranged with guitar accompaniment.2 It is based on rural singing, from

which it retains the two broad categories of dance songs in moderate to fast tempos

( khelimaski gilya or táncdalok) and slow songs (loki gilya or hallgatók) (Hajdu 1958;

Kovalcsik 1985; Kertész- Wilkinson 1990). The melody of dance songs can be

"rolled," meaning sung in vocables (pergetés ). This melody is accompanied in a

style called "oral bassing" ( szájbõgõzés ), by which several men forcefully interlock

vocables at different pitch levels (Kovalcsik 1987b:47-48). Household implements

like spoons or a water jug are used as percussion instruments. Slow songs utilize ru-

bato. In one regional variant of the slow song style, accompanying vocalists harmo-

nize a soloist's vocal line at phrase end (Kovalcsik 1981). In the rural context, Roma

are likely to sing with others who belong to their own ethnic group and extended

family. Group participation is so important that oral bassing or line-end harmoniza-

tions are often louder than the melodic line. Dance scholar György Martin reports

that Roma introduced the guitar (and tambourine) into rural-style music as an accom-

panying instrument to dance songs in the 1970s (Martin 1980:70). 3

The folklór style differs in a number of ways from rural family singing, as Gusz-

táv Varga, leader of the folklór ensemble Kalyi Jag (Black Fire), explained: "We set

these songs to instrumental accompaniment. We arranged them; if there was possibly

a line of verse that had to be removed, we took that out and added from our own-

that is, from our own ideas. So we changed the songs a little, but they returned to the

Gypsy people" (Varga 1992). One contrast between rural family singing and folklór

ensemble music lies in the role of the instrumental accompaniment mentioned by

Varga. On the occasions when Roma include the guitar in the rural family context,

they may utilize it as a drone, for rhythmic support, or with chord progressions.4 In

folklór ensemble music, guitar chords emphasize the functional harmonic character

of the melody, which is sometimes altered to accommodate the chords; a tambura or

mandolin plays either chords or the song melody. Instrumental interludes precede

and follow verses of text (Kovalcsik 1987a). Additionally, in folklór music slow

singing is metrically regularized and the vocal tone is somewhat more bel canto than

in rural singing. Folklór music utilizes line-end polyphony, vocal interjections, and

oral bassing, but the melody line remains prominent. Folklór ensembles are ethnical-

ly mixed, including members from more than one Rom ethnic group as well as non-

Roma. Their repertoires often include songs from a variety of Rom ethnic and lan-

guage groups.

This content downloaded from

157.181.112.231 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 09:47:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lange. Hungarian Rom ( Gypsy) Political Activism • 7

The stylistic changes in folklór music imply a reordering of power relations.

Folklór ensembles syncretized Rom singing with two elements valued in Hungarian

art and popular music: polished delivery and functional harmony. Katalin Kovalcsik

has described Rom communities in Hungary as musically conservative but as having

adopted from popular culture elements of songs, texts, and guitar accompaniment

that resembled existing Rom practice or were connected to Roma in some way (Ko-

valcsik 1987b:47-53). Her observations support what Margaret Kartomi has called

the "theory of central traits," according to which styles are built on the basis of shared

elements. (Kartomi 1981:240). Kovalscik also commented in her notes to the first

widely available recording of folklór music that the style reflected a change in func-

tion from privately performed music to stage genre (Kovalcsik 1987a). Folklór en-

semble participants emphasized to me that their public performance was crucial; they

developed and adopted this style not only because it appealed aesthetically to them,

but also as a means of reworking the relationship between Roma and Hungarians in

mainstream society. Kobena Mercer has argued that African-American aesthetic

forms can be viewed both as "dialogic responses to the racism of the dominant cul-

ture" and as "acts of appropriation" that have resulted in syncretism (Mercer

1990:257). While Mercer considers the dialogic level to be less significant than ap-

propriation, in the East European context dialogue had fundamental importance. In

Hungary under socialism the types of communication fostered by civil society were

discouraged, resulting in an atomized polity; in this vacuum, ordinary forms of vol-

untary association had the potential to challenge the system (Hankiss 1988:28-29,

40). The Rom members of folklór groups challenged Roma's subaltern position by

making ethnic affiliations, organizing independent ensembles, and fostering direct

interaction between the privileged and the disadvantaged.

Folklór music, through its relation to traditional music, provided a means to as-

sert ethnic legitimacy. Jánoš Balogh, an early participant in folklór activities who lat-

er co-founded the Ando Drom Ensemble and led the Amalipe umbrella organization

of folklór ensembles, stressed that they were a form of self-organization: "Our en-

sembles preserve, nurture, and develop the Gypsy people's world of tradition and

their cultural values" (Blaha 1994:6). Folklór participants stress that they perceived,

prior to the advent of folklór music, that Rom traditional singing was heavily stigma-

tized. By contrast, they found that an atmosphere of tolerance and inclusiveness sur-

rounded the performances that led to th c folklór style. This atmosphere contradicted

the Roma's rejection elsewhere in Hungarian society, a rejection that took many

forms and was present to varying degrees at all levels from villages to state institu-

tions.

The assumption that Roma have inferior cultural characteristics has been present

throughout Hungarian society. Magyars have applied the concept müveletlen to Ro-

ma. The term literally means "without culture"; such a person lacks education and

the refinement of speech, manners, and taste which this brings in the European con-

text (see Bourdieu 1984). The sociologist Zsolt Csalog noted in a summation of Hun-

garian attitudes towards Roma during the early 1980s that there were many incorrect

This content downloaded from

157.181.112.231 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 09:47:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

8 • the world of music 39(3)- 1997

assumptions about them. The intelligentsia had little information on Roma. In spite

of the fact that villagers had personal contact with them, many thought that the be-

havior of Roma was "un-bourgeois" (Csalog 1984:74-75).

Until the appearance of th q folklór ensembles, violin music and stereotyped sing-

ing (i cigánydal ) accompanied by strings were the genres that defined Rom music in

the Hungarian public sphere. In the 19th century, Rom violinists received accolades

for their virtuoso playing and for their service as accompanists to Hungarian cafe pa-

trons who sang magyar nota , the patriotic popular song of the period (Sárosi 1978

[1971]: 131-34). Cigánydal (Gypsy song) developed as a mass-mediated sub-genre

of magyar nòta in the mid-1950s. Sung in Hungarian, cigánydal included transla-

tions of Romani-language songs and other songs that emphasized the stereotype of

the Gypsy.5 Magyar nòta singers (both Rom and Hungarian) performed cigánydal ,

accompanied by string orchestras. By the 1960s, public opinion was contradictory on

the subject of Rom singing. Cigánydal as a form of magyar nòta enjoyed popularity

among the working class and villagers (Losonczi 1969:138-41).

The negative opinions of the intelligentsia about this music show deep class dif-

ferences in musical taste (Lange 1996). In his summary of the representation of

Roma in the Hungarian press, András Hegediis criticized the fascination for Gypsy

music and dance as a disguised means of building the ethnic stereotype: "In this me-

dium the tone is friendly, sometimes overheated to rapture ... it is a form of present-

able social Darwinism, where we explain with genetic or sexual peculiarities the fact

that the viewer becomes a 'friend of the Gypsies' upon seeing their unique talents,

harmonious movements, and beautiful bodies" (Hegedüs 1989:70).

Most of the Hungarian intelligentsia considered this music to be aesthetically in-

ferior because of its association with magyar nòta , its emphasis on stereotypes, and

because of magyar nòta' s earlier links with corrupt nobility (Frigyesi 1994). The eth-

nomusicologist Imre Olsvai observed that in the late 1950s scholars were unable to

draw the attention of the public to the actual village performance practices of Roma,

while cigánydal accompanied dance choreographies and was broadcast on the radio

(Olsvai 1977:8).

Many members of the intelligentsia had a potential interest in rural Romani-lan-

guage music because of their great respect for the work of Bartók and Kodály on East

European folk song (that is, village singing that had retained a style apart from 19th-

or 20th-century urban popular song). Bartók had recorded and transcribed some Ro-

mani-language singing, referring to it as "real gypsy music" (Bartók 1947

[1931]:252; Vig 1974). Such singing had also been researched by other folk song

scholars since the 1930s. However, several conditions mitigated against a larger au-

dience becoming familiar with this music. Sándor Csenki, who along with his broth-

er recorded songs from Roma in southeast Hungary, died during World War II, and

his recordings were lost.6 André Hajdu, a student of Kodály, had just begun to pub-

lish his research on the subject of Romani-language singing (Hajdu 1958) before he

emigrated in 1956. The decisions of the Hungarian authorities to pursue a policy of

This content downloaded from

157.181.112.231 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 09:47:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lange. Hungarian Rom ( Gypsy) Political Activism • 9

assimilation also contributed to the fact that this music remained in obscurity as far

as the general public was concerned.7

Ágnes Daróczi (a Rom) and Jánoš Bársony (a Magyar), who were early partici-

pants in folklór music, trace institutional antipathy towards Rom singing to the spe-

cific policies regarding Roma that the Hungarian Communist party established in

1961. The party's particular concern was that Roma were not yet participating in the

creation of a large working class; the reasons were thought not to lie in their cultural

differences, but rather in their lack of education, proper housing, and employment

opportunities (Gronemeyer 1981:205-208). The government took the position that

these things should be provided for Roma- and their consent was not considered to

be an issue. However, since the primary goal was to create workers out of Roma, they

would not be classified as an officially recognized ethnic minority, or "nationality."

Jánoš Bársony quoted from memory a key passage in the 1961 party declaration:

"Our political action towards the Gypsy population must be based on the principle

[that] in spite of certain of their folkloric peculiarities, they do not comprise a 'na-

tionality'" (Jánoš Bársony 1996; Mezey 1986:242).

The designation "nationality" derives from Soviet policy, which officially recog-

nized some ethnic minorities but did not allow them actual statehood (see Pipes

1975). In Hungary, the ethnic minorities who were classified as "nationalities" (for

example Germans, Slovaks, or Romanians) received many forms of institutional

support, including ethnically specific language instruction, radio programs, and folk

performance groups.8 Unlike Roma, the Hungarian "nationalities" had affiliations

with other European states or provinces; one propaganda document also observed

that the "nationalities" had been early participants in the Hungarian Communist Par-

ty and had helped establish its government (Nagy 1955:8; see also Hammond

1966:22). In contrast to the "cultural and also material advancement" that socialist

policy accorded to the nationalities (Nagy 1955:9), the government took the position

that it would be harmful to establish the Rom-oriented institutions that a "nationali-

ty" classification required.9 The government used this rationale to allow Magyars

and the officially recognized ethnic minorities the widespread local organization of

ensembles and clubs for village music and dance while at the same time stopping

support for the activities of most small Rom folk ensembles that had been function-

ing in villages.

The views of Rom culture that directly affected the first Rom participants in

folklór ensembles were articulated at the village level as they were growing up in the

1960s. The folklór performers with whom I have spoken emphasize that villagers

were derisive of their domestic languages, singing in those languages, and of them-

selves as people. Ágnes Daróczi recalls that it had a severe effect on her: "Even as a

child, a person would countless times be put into the situation where it was expressly

bad to be a Gypsy. It was a hateful thing. You felt as though you were burning. That

you would like to peel your skin off. That you would like to hide in the smallest

mouse hole. Just don't be in front of people and have them look at you like that. I dis-

covered this in my own self too, that I would like to hide and deny it" (Daróczi 1996).

This content downloaded from

157.181.112.231 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 09:47:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

10 • the world of music 39(3)- 1997

Since villagers had personal contact with Roma, they knew that there was a

unique style of Rom singing. But they often found this singing unbearable. Ko-

valcsik attributes this to the "intolerance of unilingual Hungarian society," comment-

ing that villagers often interrupted her recording of Boyash Rom songs, which they

could not understand (1996:92). Villagers sometimes viewed Romani-language

songs not as music, but as offensive forms of vocalization. Gusztáv Varga, leader of

the folklór group Kalyi Jag (Black Fire), has observed that "young people did not

sing these, because, you know, they would say that the Gypsies were bellowing (gaj-

dolnak)" (Varga 1992).

Both Daróczi's and Varga's comments reveal that, in a common reaction to stig-

ma as described by Erving Goffman (1963:102-104), many Roma responded to the

general negative atmosphere by obscuring as much of their difference as they could.

Roma spoke their unique languages and dialects primarily in the home; they avoided

singing or speaking these languages in a context where fellow villagers could hear

them. Kovalcsik has noted that one Boyash informant was reluctant to sing because

he feared that villagers would think he were drunk (Kovalcsik 1988a:217). Gusztáv

Varga (1992) commented, "Many [Roma] were embarrassed to speak the Romani

language, because everywhere they said 'why do you speak in such an ugly way,

stutteringly, what [on earth] are you saying?' and the people began to believe about

themselves that they should stop, because they weren't accepted at school or in pub-

lic opinion."

The stigmatization of Rom culture at the village level includes many paradoxes.

Firstly, it is not clear that all Roma responded by reducing their singing activities.

Roma reserved a great deal of their musical performance and native language con-

versation to private, family-centered environments. Recent ethnographic work from

two different Vlach Rom communities in Hungary demonstrates that their musical

values and activities could be autonomous from those of non-Roma. Roma might

emphasize the separateness from non-Roma in their aesthetic evaluations of perfor-

mance style (Kertész- Wilkinson 1992:114) or in their moral assessments of song

texts (Stewart 1989:87-87). But in addition to the emphasis on cultural separateness

deriving from this fieldwork, Daróczi and Gusztáv Varga asserted to me that Roma

did feel and react to negative views of them at the village level.

Romani-language singing became destigmatized in the early 1970s when Roma

began to perform in a new environment- the worker's hostels of Budapest, Hunga-

ry's capital city. Ironically, this was a side effect of the state assimilation policies.

Hungarian citizens had to work at jobs given or approved by the state. Otherwise

they faced the possibility of fines (Gronemeyer 1981:208). As one Rom observed,

there was also the threat of jail sentences on vagrancy charges (Anonymous 1992).

The state's centralization plans involved concentrating industrial activity in urban ar-

eas (Huseby-Darvas 1989:490-91). Many Roma from the countryside thus had to

suspend their traditional trades, among them basket-making, smithery, and wood-

carving, to work as manual laborers on huge building, factory, and highway con-

struction projects in Budapest and western Hungary (Grabócz and Kovalcsik

This content downloaded from

157.181.112.231 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 09:47:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lange. Hungarian Rom ( Gypsy) Political Activism • 11

1988:25-26). They were not allowed to permanently move to these areas with their

families, but instead the workers lived for most of the week in large dormitories

called "worker's hostels." Worker's hostels were ethnically mixed; their residents

also included many lower-class Hungarians who likewise worked as manual labor-

ers.

Musical performance that originally took place on a casual basis at the wor

hostels would not necessarily have drawn much attention. Jánoš Bársony, i

menting on the recognition given to Rom music by stage performance, contr

with "the person who sits in the corner and makes music and dances for his own

sure and that of his buddies" (Bársony 1996). Kovalcsik has observed that th

hours entailed in commuting to work may have stimulated traditional storyt

practices (Grabócz and Kovalcsik 1988:28). Jánoš Balogh relates that outside

est, as well as the spare time they spent at the hostels, helped stimulate him and

Roma from his home village to create an ensemble for formal performance.

Most people were living in workers' hostels ... Well, we were together a lot, so a gui

would turn up; we talked together, played music together, and so forth. And there we

one or two cultural educators ( népmüvelo) who ultimately thought that if so many pe

ple are gathered together then there should be a cultural event. This slowly took sh

and formed so well that this forged into an ensemble in Budapest (Balogh 1992).

The cultural educators whom Balogh mentions were hired by the state to or

leisure activities for the hostel residents. However, the activities of the népmü

sometimes contradicted the official assimilation policies; in fact, the attention

sympathy with, disadvantaged people demonstrated by many of them had a

predating socialism. Georg Schöpflin, in his analysis of Hungarian dissidenc

classified this as a type of resistance which took place from within the institutio

the state and which was thus tolerated to a certain extent (Schöpflin 1979:142

53).

The hostels also attracted more specifically politicized and dissident activity. It is

this activity, exemplified by the work of the musical ensemble Monszun (Monsoon),

which is most closely linked with the emergence of the seminal folklór group Kalyi

Jag. Monszun was an ensemble of young musicians from the Hungarian intelligen-

tsia. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, they began a series of interchanges with the

residents of the hostels. Monszun played Hungarian "beat"- that is music in 1960s

"British Invasion" style. Jánoš Bársony, one of Monszun's members, relates that he

and other group members were for a brief time interested in Maoist teachings, with

several results. Along with several other beat groups, they utilized song lyrics that

had political content, rather than themes of romantic love. Jánoš Balázs, in an analy-

sis of musical activities by Hungarian young people in the 1970s, called these ensem-

bles "hard folk" groups. He noted that they were the first in Hungary to try "folk fu-

sion" as a statement of political solidarity, combining 1960s rock with the folk music

of other peoples involved in socialist political movements or systems, particularly

South Slavs and Latin Americans (Balázs 1983; see also Vitányi 1974). 10 Julia Bár-

sony, Monszun's artistic director, asserts that the group was not interested in wide

This content downloaded from

157.181.112.231 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 09:47:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

12 • the world of music 39(3) - 1997

exposure or commercial success; the group got neither recording contracts nor exten-

sive media attention. The members of Monszun saw themselves rather as musical

ambassadors within Hungary's borders. They initially construed this in class terms;

in an effort to find out more about the music of Hungary's lower classes, they began

to visit the worker's hostels. There, Jánoš Bársony notes, they immediately encoun-

tered Roma as well as Magyars.

In line with a century-long practice by Hungarian intelligentsia, Monszun' s

members initially went to the hostels to "collect" music, that is, to tape record songs

from individual performers. However, Dénes Marton, Monszun's manager, noted

that because the group's Maoist philosophical orientation stressed the practice rather

than the rhetoric of mobilization, their goal was to build a relationship with residents

of the worker's hostels. Monszun members and the hostel residents attended movies

together and visited one anothers' homes- activities which were unusual because of

ethnic segregation and the rigid social stratification that obtained at the time (Marton

1996). Monszun did not simply pursue the accepted Hungarian scholarly method of

music "collection," whereby the researcher directs a solo singer to perform individu-

al repertoire items in an acoustically clean setting. They closed the distance that this

elicitation method creates by concluding their sessions with joint music-making.

Jánoš Bársony says that the Roma impressed both the members of his group, as well

as Magyar residents of the workers' hostels, with their striking dance movements and

musical improvisations (1996).

For many Roma, music-making in the worker's hostels stimulated a new form of

interaction with non-Roma based on mutual respect. Agnes Daróczi has observed

that as a result of their performances in the worker's hostel music sessions, Roma got

recognition from Magyar workers both as individuals and as people worthy of re-

spect for their performance abilities.

This achievement not only encouraged and prompted the Roma, or rather those who

stood up on stage and sang, but ... it gave dignity. Out of that nameless nobody and de-

spised Gypsy, he became a personality. In the eyes of his fellow workers, he became

Zsiga. "Zsiga, when are you going to sing? When will there be a performance again?

Zsiga, will there be a club [meeting], can we come?" And because he himself got dig-

nity, he made even more effort (Daróczi 1996, spoken emphasis indicated by italics).

Early in its history, Monszun also began to include Rom members and Romani-

language music in its own formal performances. Julia Bársony reports that the group

held rehearsals weekly, with approximately fifty Roma in regular attendance. In an

observation that confirms the variety of Rom attitudes towards formal ensemble

playing, Bársony notes that although Monszun's rehearsals were open, the partici-

pants were self-selecting. She recalls that the group members met many musically

gifted Roma who were not interested in pursuing music for public performance, with

the rehearsals, arrangements, and memorization that this entailed (Julia Bársony

1996). From the rehearsal group of fifty, a smaller ensemble was culled for Mons-

zun's public concerts. These performances, in keeping with the group's ideology,

This content downloaded from

157.181.112.231 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 09:47:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lange. Hungarian Rom ( Gypsy) Political Activism • 13

were held primarily in the small clubs that were attached to worker's hostels and oc-

casionally at larger clubs associated with factories (ibid.).

Performances by Monszun and in other worker's hostels provided some of the

first occasions for Romani-language singing to be heard by the general public in

Hungary. But because their activities were quasi-dissident, most of the early perfor-

mances of politically-oriented Hungarian "beat" groups like Monszun were confined

to small university clubs and isolated culture houses. One key step in the shift from

Monszun's folk-popular fusion music to the formation of Rom folklór ensembles

was the meeting of Ágnes Daróczi and the Monszun group at a nationally organized

and adjudicated talent contest for youth called Ki mit tud or "Who can do what?"

Ágnes Daróczi was a winner in this contest as a reciter of Romani-language poetry.

Like many Romani-speaking Roma in Hungary, she came from a close-knit family in

a small village. A teenager at the time of the contest, she subsequently became a lead-

ing intellectual, politician, and organizer of Rom performing groups. She first recog-

nized in the work of the Rom poet Károly Bari that newly created art forms were ca-

pable of expressing both the social difference that was manifested in the exclusion

and ostracism of Roma in her village and the necessity of resisting self-rejection. "I

discovered myself while reading his lines [of poetry]. I realized that even if the world

is prejudiced, we have no alternative. We can stand up and cry out that yes, we are

Gypsies. We will not deny it. In fact, we are proud of it. And we will demonstrate to

them that we are not those people [they think us to be], but rather the possessors of

wonders and treasures. And we are going to demonstrate this" (Daróczi 1996)

After 1972, Daróczi and one Monszun member, Jánoš Bársony, began working

even more intensively with Roma, while the other members of Monszun pursued ac-

tivities more characteristic of small pop groups of the time. It was at this point that

folklór music can be said to have taken shape. Ensembles formed which had a pre-

dominately Rom membership and took on Romani-language names, including Ro-

mano Glaso (Romani Sound), Rom Som (I am Rom), and Kalyi Jag. Daróczi per-

suaded these groups to participate in public programs. Meanwhile, she gained

institutional clout by completing a university degree. She was hired as a Rom spe-

cialist at the Cultural Education Institute (Népmûv elési Intézet ), which under the re-

form Communist Iván Vitányi helped sponsor many folk revival efforts. The mid-

1970s saw an expansion of Rom performing groups all over Hungary. Both Jánoš

Balogh and Gusztáv Varga estimate that by the mid-1980s, there were approximately

sixty groups (Balogh 1994; Varga 1992). Daróczi, as well as another cultural educa-

tor assigned to the large Szegedi Worker's Hostel, organized trips abroad and to

towns in the countryside for performing groups, where they met other Roma and in-

spired them to form similar groups. She encouraged Rom performers to take the ex-

aminations required to give formally organized concerts on a regular basis. She also

produced several festivals for Rom performing groups and a concert series at the

University Theatre (Egyetemi Szinpad) in Budapest, which had a reputation for pro-

gressive and high-quality performances. Other Rom intellectuals and community

This content downloaded from

157.181.112.231 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 09:47:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

14 • the world of music 39(3)- 1997

leaders organized youth clubs and summer camps where music and dance perfor-

mance was the main activity.

Rom activists have observed that folklór music was an important means of inter-

nal political mobilization. The state had recruited a few Roma to aid in the formation

of Rom-oriented policy, but because they were chosen from above, their integrity

was compromised in the view of the Roma (Havas 1991 [1988]: 19-20). Folklór

groups were often the vehicle for quasi-dissident expression. In an interview with

István Javorniczky, Daróczi observed that the Rom performing groups produced

community leaders as well as effecting change in individuals.

Performing gives great prestige and recognition. This has an effect on the other parts

of [the performers'] lives; they will be greater because of it. And it also persuades

them a bit to prove this in the rest of their lives. It gives them some incentive to prove

this in the other areas of their lives. There is another influence which is not insignifi-

cant from the standpoint of the community. This kind of ensemble is never just purely

an ensemble ... they function as a forum. State and societal leaders invite them to dis-

cuss what they think of their own fate, what points there are upon which they can be

helped, what requests they have, how these might be achieved, etc. This inevitably

brings them with more exact knowledge and preparation to the level of political lead-

ership (Javorniczky 1986:224-25).

After the fall of socialism, many of the Roma who became active in drafting leg-

islation, negotiating with political parties, speaking to the press on Rom issues, and

serving as elected representatives, were indeed the leaders of folklór groups. (Includ-

ed among these were Aladár Horváth, Jenô Zsigó, Jánoš Balogh, and Ágnes Daró-

czi.)

2. Mainstream Acceptance of Rom Folklór Music

In the 1970s, there was receptivity among the Hungarian intelligentsia towards learn-

ing more about Roma. This was signaled from multiple fields of interest, including

the initiation of a sociological study that involved in-person surveys of Rom districts

around the country (Kemény 1974), the pressing of a record of Romani-language

field recordings (Hungaroton SLPX 12028-29), the awarding of prizes to young

Rom artists like Daróczi and the poet Károly Bari, and the publication in a handsome

edition of translated Rom song texts (Szegó 1977). But in order to be accepted by the

Hungarian mainstream as a valid expression of ethnic identity, Rom folklór music

had to demonstrate that it was comparable as an art form to Hungarian folk music.

Hungarian intellectuals applied a very strong set of aesthetic standards to folk music

(see Frigyesi 1996). They paid a great deal of attention to evaluating folk music per-

formances for authenticity and for a rural provenance unaffected by popular styles

(the "pure source," or tiszta forrás). A summary by László Dobszay concludes that,

although definitions of folk song are extremely complex and often contradictory,

"authentic" Hungarian folk songs were performed mostly by peasants, were integral

This content downloaded from

157.181.112.231 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 09:47:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lange. Hungarian Rom ( Gypsy) Political Activism • 15

with the life of a rural community, and exhibited "relative homogeneity" of style

(Dobszay 1992:12). The idea of homogeneous style also implies uniqueness. In his

seminal essay comparing Hungarian folk music with that of neighboring countries,

Béla Bartók qualified homogeneous musical styles as sharing special features ( közös

sajatságú egységek ; Bartók 1952 [1934]:3). In the 1970s, folk revivalists in what was

called the táncház (dance-house) movement were endeavoring to replicate the

unique dance styles, costumes, and music of specific Hungarian villages (Siklós

1977; Frigyesi 1996). The urban Gypsy orchestras and singing both of magyar nòta

and cigánydal were cited as the epitome of inauthenticity and low taste. In truth, the

popular music elements utilized by folklór ensembles also contradicted the musical

ideals of dance house adherents, although the rural origin of much ensemble music

appealed to the "pure source" ideal.1 1

The activities of Rom folklór ensembles have much in common with those of the

Hungarian dance houses of this period. In both cases, the principal participants were

young people. Dance-house repertoire, like that of Rom folklór ensembles, was

sometimes ethnically mixed. While they primarily derived from Hungarian villages,

dance-house repertoires often included the music of other regional ethnic groups (but

rarely Roma). Several ensembles focused on specific ethnic minority idioms, partic-

ularly those of the Romanians and South Slavs in Hungary (Széll 1981:52-62, 153-

90, et passim). The small club was an important early forum for both dance-house

and Rom folklór ensembles. Agnes Daróczi relates that the musical evenings she

helped organize at worker's hostels in the early 1970s initially included poetry read-

ing; similarly, some events of the dance-house movement involved poetry set to mu-

sic (Sebo 1981 [1975]:28). The Institute for Cultural Education, which employed

Agnes Daróczi, was also a center of institutional support for dance-house activities.

In spite of these many connections, however, both Daróczi and Gusztáv Varga

emphasized to me aspects in which Rom folklór activities differed from the dance-

house movement, particularly where access to the largest media and performance in-

stitutions was concerned. According to Daróczi, dance-house and Rom folklór

events attracted completely separate audiences (Daróczi 1996). The clientele of the

Rom ensembles, which gathered in small clubs adjoining worker's hostels, differed

greatly from that of the college clubs and district culture houses where dance-house

events took place. However, audiences at dance camps, the University Theatre con-

cert series, and the occasional college club where Rom ensembles performed consti-

tute exceptions, since they were initially attended by Hungarian folk revivalists.

Daróczi and Varga focus on institutional rigidity as one of the primary obstacles

to be overcome in gaining broad public acceptance for folklór music. They encoun-

tered difficulties with funding, participation in large folk festivals, and recording.

Daróczi objected, for example, that a modest funding request to the Cultural Educa-

tion Institute for a Rom ensemble from Nagyecsed was bureaucratically obstructed

when it bounced for months between the dance and the adult education departments.

She observed, "this is not just a question of money, but of faith. Whether or not insti-

tutes and society have faith that a performance-ready ensemble will organize from

This content downloaded from

157.181.112.231 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 09:47:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

16 • the world of music 39(3) - 1997

this assemblage" (Javorniczky 1986:223-224). The recollection of Gusztáv Varga is

that those who controlled the infrastructure of festivals, recordings, and culture hous-

es frequently supported the performances of Hungarian dance-house ensembles,

whereas they were antipathetic towards folklór music.12 He reports that his group

Kalyi Jag did not receive invitations to large folk festivals until the mid-1980s. On

the other hand, two Rom dancers, Gusztáv Balázs and Béla Balogh, had been well

accepted by dance-house participants and particularly by the scholar György Martin,

who was a major supporter of young people's efforts to perform folk music and

dance during this time. By providing music for these Rom dancers both in their per-

formances and in their activities as dance teachers, Varga explained to me that Kalyi

Jag was able to expose the dance-house participants to its music.

BRL: At what kind of functions did you play in the beginning; did they invite you to

play?

GV: They did not invite us anywhere. I went around to the clubs alone, because the

group had dissolved ... I went to youth clubs and company clubs and worker's hostels,

and I organized things there. I told them that we are this ensemble and we would like

to give a performance, we are very inexpensive, and we went ... so, these kinds of

clubs. Later culture houses, then the University Theatre. Ágnes Daróczi organized a

series where the group performed a number of times. We went to camps, youth camps,

and we performed there too. So news [of us] went around among young people.

BRL: For example there were large folk music ( népzene ) festivals like the one in

Szeged. Did they ever invite you [to perform]?

GV: No, they didn't invite us ... just in the last three or four years. They didn't invite us

to folk music festivals. They said, "this music is not suitable." They didn't think that it

was of such high quality and they didn't really think it was important. But Béla Balogh

and Gusztáv Balázs, who are dancers whom we can say are the most outstanding prop-

agators of Gypsy dance, went to contests. We always went with them and we then

gave performances. We sang [to accompany] them. We struggled very hard (Varga

1992)

The contests and large outdoor festivals declared by Varga (along with the re-

cording industry) as so difficult to penetrate match those activities which Jánoš Szász

called "organized folklore," responsible for the entrenchment of norms in dance-

house activities (Szász 1981:118). Further, Daróczi (1996) recalls that security pre-

cautions were so severe at the first national festival of Rom ensembles she organized

in the 1980s that even the stage platform was patrolled by policemen with dogs. It is

possible, then, that Rom folklór ensembles had limited participation at large festivals

not only because the organizers followed strict stylistic guidelines, but also because

there were state security concerns based on negative preconceptions about Rom per-

formers and audiences.

Following the thought of Bartók and Kodály, the music of Rom folklór ensem-

bles has many characteristics that dance-house adherents and the Hungarian intelli-

gentsia in general consider clear markers of uniqueness and authenticity. These in-

clude the rural provenance of much early folklór ensemble repertoire, polyphony, use

This content downloaded from

157.181.112.231 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 09:47:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lange. Hungarian Rom ( Gypsy) Political Activism • 17

of the Romani or Boyash languages, found objects as musical instruments, and voca-

bles. Katalin Kovalcsik, in introducing this music to the general public through the

jacket notes to Kalyi Jag's first recording, observed that the music had a clear con-

nection to the domestic village environment. However, the arranged character of the

melodies and use of the guitar meant that the question of stylistic authenticity had to

be repeatedly addressed. Ágnes Daróczi, responding to a question by Javorniczky

about the difference between (Hungarian) folk ensembles and the Rom ensembles,

focused upon the contiguity of folklór music with a local source and refrained from

classifying it according to musical sound.

IJ: These ensembles are in special circumstances. A folk (népï) ensemble performs be-

fore the audience in an established way. On the other hand, in the case of Gypsy tradi-

tion-preserving ( hagyományõrzõ ) ensembles, it is not certain that the audience in an

auditorium and the true audience are one and the same. Why and for whom do they

play?

AD: The Gypsy ensembles are both more and less than the traditional folk ensembles.

They are more, because it means more to the participants. Simply put, in most cases

the rehearsals and performances in front of others have such a large role in their lives,

and not just for some, but in the life of the community, that it has a decisive influence

in forming the person. On the one hand, there is Gypsy tradition, which is a living

thing; many more people can dance and sing than there are ensembles, and many times

those people who are the best practitioners are old and have too many family responsi-

bilities to be in an ensemble (Javorniczky 1986: 224).

Th e folklór ensemble leaders and participants of my acquaintance regularly use

three terms in reference to their groups: együttes (ensemble), hagyományõrzõ (tradi-

tion-preserving), and folklór. They rarely use the Hungarian-language prefix for folk

culture, nép-. By contrast, participants in dance-house groups favored the term nép -,

which was in turn the expression most frequently used by Bartok, Kodály, and many

other Hungarian folklorists (Széll 1981, Siklós 1977). The word folklór is utilized in

the Hungarian scholarly lexicon as an alternate for the term "folk culture" (népi

kultura) .

One reason Rom ensembles use the three terms mentioned above rather than nép-

is to contrast their music with that of the Gypsy string orchestras. The latter often

used the adjective népi in their ensemble names as an indication that they played ar-

rangements of Hungarian village songs as well as the 19th-century popular song

genre magyar nòta. Dryly referring to cigánydal and the Gypsy string orchestras as

the dominant media allowed in the public sphere, Jánoš Balogh utilized the term

folklór to contrast them with Romani-language music: "When at the very first we

started to demonstrate and to raise up the life and the culture of folklore (folklór ),

people knew it barely, or not at all. How could there be an audience, if they did not

know it? Since we [the general public] had the opportunity to know Hungarian com-

mercial music, Gypsy music."

Mozgalom (movement) was another term used by many analysts to refer to Hun-

garian dance-house activities (Balázs 1983, Sági 1979) and to Rom folklór ensem-

This content downloaded from

157.181.112.231 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 09:47:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

18 • the world of music 39 (3) - 1997

bles (Kovalcsik 1997). It seems self-evident that as a movement, the activities of

Rom folklór ensembles represent a collective attempt to create change. But the Rom

folklór ensemble participants of my acquaintance do not use this word. Their reflec-

tions on how folklór music changed the position of Roma place more importance on

the avenues they managed to create locally or as individuals, rather than upon large-

scale mobilization. Similarly, it was not necessarily important to the participants that

Rom folklór music match every one of the aesthetic criteria that apply to Hungarian

folk music. In their usage, the English loan word folklór claims a rhetorical space

analogous to, but not exactly the same as, that for Hungarian folk music.

Gusztáv Varga's group Kalyi Jag can be credited for elevating Rom singing aes-

thetically in the mind of the Hungarian intelligentsia; as Kovalcsik has noted, a num-

ber of previous Rom groups had formed but then dissolved without making a mark in

Hungarian public musical life (1987b:50). Several factors contributed to Kalyi Jag's

rise to prominence. Of the Rom folklór ensembles, Kalyi Jag had the most direct con-

nections with Hungarian musical values through Monszun. Even before Varga

formed Kalyi Jag, relatives and members from his particular Rom ethnic group, the

Churara of northeast Hungary, had been members of Monszun. Varga also possessed

an extraordinary degree of tenacity. For several years he persisted in assembling his

group for rehearsals even though he himself had to commute to Budapest from his

job leading a construction brigade near Lake Balaton (Varga 1992; Jánoš Bársony

1996). The group survived several personnel changes. Béla Balogh, one of the Ro-

mani dance teachers mentioned previously, performed with the group as a vocalist

and Kalyi Jag accompanied him to dance camps and contests. Over its history Kalyi

Jag had non-Rom members, including Jánoš Bársony and the present female vocal-

ist, Agnes Künstler.

Kalyi Jag's particular version of the folklór style displayed characteristics which

were likely to appeal to Hungarian taste. Whereas many other folklór groups were

large, Kalyi Jag had only four members. The larger ensembles often recreate group

participation on stage. As Jánoš Balogh observes, this promotes a family atmosphere

within which the ensemble members themselves feel good. However, this structure

proves not completely successful in holding the attention of an audience (Balogh

1994). Kalyi Jag projected its music to the audience very clearly and formally; con-

trasting elements of the musical texture were clearly discernible.

One of Varga' s main concerns was to counteract the village impression that Rom

singing was crude or noisy. Early in the group's history, when he attempted to sched-

ule concerts at factory and workers' clubs, he reports that he had to struggle to per-

suade the club directors that the music was worthwhile: "They condemned this music

because at that time only the violin was known to the public. They condemned it, that

it was a kind of Gypsy music ( cigányzene ), but when they heard it, what a nice mood

it had and how melodic it was, we became closer to each other" (Varga 1992). Sever-

al years later, Varga organized engagements for the group at culture houses in the

countryside, where he also had to counteract the impression of Rom singing as gaj-

dolás , or bellowing, by emphasizing that "this music is soft and pretty" (Varga

This content downloaded from

157.181.112.231 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 09:47:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lange. Hungarian Rom ( Gypsy) Political Activism • 19

Rubato I1 ca. 144

aj, te iío-star man-ge, ma-mo, mu-ro ter - jio : tra- jo, jaj

_o dfc. jaj ]a h ]a ]a

male . ■

voice ß'

' h *

l'I -

o, k( Te naj

an-dre,

haj an-dre, ma-mo, khan-chi bo - If lfcu) V

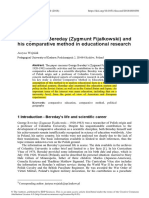

Fig . 1. "Sostar mange , mamo " (What Is My Young Life For , Mother? ). Slow song. -

Rom sam ame! find 194 , #11. Lower mordent; aj vocable , /PA; / ř/rae ¿fe/úry or

anticipation).

1992). Varga's priority on gentleness, however, was not universally expressed by

Rom folklór performers. Jánoš Balogh observed, "It is not up to me to soften [the mu-

sic], but people should relax and be freer" (Balogh 1992).

Refinement (finomság) is a value which is present in rural, neighborhood, or fam-

ily Romani-language singing as a form of extremely courteous speech (Stewart

1997:188). Singing in the group setting is considered to be the most "true" form of

speech (Stewart 1989:85-87). This music emphasizes group participation in ways

which sound unrefined by non-Rom standards. In the region of Hungary from which

Kaly i Jag's Rom members come, Katalin Kovalcsik identified styles of slow singing

with extended rubato, polyphony, and elaborate line-end ornaments (1981). In slow

singing, pauses can suspend the rhythmic pulse at the middle or ends of phrases. The

performers use a wide variety of contrasting vowel sounds. Rather than ending

This content downloaded from

157.181.112.231 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 09:47:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

20 • the world of music 39(3)- 1997

phrases with a pure vowel or consonant, the singers often utilize diphthongs. In the

single verse of a slow song transcribed in Fig. 1, the singers precede and follow text

with vocables. The vocables include six different vowel sounds and two diphthongs;

during the course of six verses, fifteen different diphthongs are used (Fig. 2). The

texture is intermittently heterophonic; the singers who follow the main vocalist delay

their articulations slightly and may sing a different melodic line. The followers must

indicate respect for the lead performer (Bodi Varga 1992); in addition, since the

songs are improvised, followers cannot anticipate exactly what the leader will sing

(see Kovalcsik 1981:261). At the ends of the text lines in Fig. 1, the singers add orna-

menting sets of vocables that emphasize primarily the intervals of a minor third and

the octave. The multiple vowel sounds, diphthongs and added volume all increase

the resonance of the line-end notes while emphasizing the group participation aspect

of the music.

Diphthongs used over six stanzas: €w, aj, aw, aej, £j, jœ,oj, aw, uae,eA > aew,

eaew, oae, aeu

Vowels and Diphthongs Used on Sustained Tones

1 a/e/h

2 a/L /aw

3 aj/c or l/q e/ae/g.

4 aj/gK/jw/ew ae/aew/eaew/a

5 aj/A/c.

6 a/e/aew a/oeu £/aew

Symbol i L A e C x u ° O a aj aw

Example" beet "Bit Enît bate bet pan boot put boat bought pot bite br own

Fig. 2. Vowels and diphthongs used in "Sostar mange , mamo . "

Kalyi Jag's music is "refined" by Western art music standards; text enunciation is

clear, the melodic line is prominent, vocal tone is sweet, and the rhythmic pulse is

somewhat regularized. This is particularly evident in the group's versions of the mu-

sic from their home region. (Kalyi Jag also modified songs that they added to their

repertoire from other Rom language groups by adding elements of Vlach Rom fami-

ly singing [see Kovalcsik 1996:89]). In Kalyi Jag's slow song transcribed in Fig. 3,

the tempo is much faster than in rural family singing. The rhythmic pulse is suspend-

ed at line end, but the held notes and pauses have approximate duple or quadruple

beat proportions. The performers utilize contrasting vowel sounds less often than in

family singing. At the end of the first phrase in Fig. 3, all singers use different vowel

This content downloaded from

157.181.112.231 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 09:47:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lange. Hungarian Rom ( Gypsy) Political Activism • 21

Parlando P ca, 176 J* ca. 163

Mer' te me-rel, mu-ri dej? Te me-rel e lu - ma!

"i* » ~ j 77""^ ~ '

male voice ~ ¡Un "j ~ : f 1?J f |* lÍT f ~ ;

:! 'A _ ^

i ! TI *f - tm- f P ft i 5

male voice *11

Aw Au - ma

✓ '

f ca. 192 *

1 n^u

ki Te me-rel e lu 'ma, sar mu-ri ¡de - he- "jo - j ri.

J

: • : /y

^9* V - ! - ; Iw i a.. ■' j|.0 ===:

; de - jo - :h¿ri

I .^77 ' Ô- V"

e de - jo i_

Fig. 3. "Mer' te merel , muri dej? " (Why Did You Have To Die , Mother? ). Slow song,

sung by Kaly i Jag. - Kalyi Jag HCD 18132 , #18. ( voices are presented in temporal,

not score order ; / time delay; + lower mordent; Ke vocable, IP A).

sounds. At the end of the second phrase, however, two sing the sound [a], while only

the third singer utilizes the contrasting sound [a]. They use diphthongs only sparing-

ly and quickly change vowels within the diphthong rather than drawing out the tran-

sition as in Fig. 1 . Rather than staggering the tempo throughout the line-end orna-

mentation, Kalyi Jag's singers only delay their initial articulations of line-end notes.

The texture at line ends in Example 2 is homophonic. At the end of the second

phrase, one accompanying singer outlines a major triad; at the end of the last phrase,

the singers anticipate a diminished leading tone chord through passing tones, which

then resolves to the final, an open fifth. The melodic line and the text are prominent

because the accompanying voices sing more softly than the leader.

Given Gusztáv Varga's experience with Hungarian reactions to village singing,

the subtle stylistic modifications made by his group Kalyi Jag seem to have been nec-

This content downloaded from

157.181.112.231 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 09:47:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

22 • the world of music 39(3) - 1997

essary in order for the music to appeal to a Hungarian audience that was uninformed

about the internal aesthetics of Rom family singing. The influence of Monszun's ear-

lier work is also evident. Monszun emphasized extensive rehearsal preparation, dur-

ing which guitar chord sequences, vocal harmonies, and song medleys were worked

out to produce polished performances; the group received help with some of its mu-

sical arrangements from professionals and conservatory-trained musicians (Julia

Bársony 1996). The mixing of Rom and non-Rom members in Kalyi Jag, as with

Monszun, may also have had an effect on the resulting musical texture, since non-

Roma would have been accustomed to homophony or monophony rather than the

overlapping voices of Rom group singing.

The members of Kalyi Jag received the national award "Young Masters of Folk

Art" in 1979, and they were the only folklór group ever to be awarded a contract with

the state recording company Hungaroton. The remarks of the reviewer András

Bankó upon the release of Kalyi Jag's second album indicate how appealing folklór

music had become for Hungarian audiences. Banko observed that "with barely no-

ticeable refinements and polishing [the recording] brings out the original flavor of

the music and dance, making it worthy of the stage for an upper-class (uri) audience"

(Bankó 1990:4).

Not only did Kalyi Jag's music appeal to Hungarians but, as Katalin Kovalcsik

(1996:88-89) has observed, it had a sweeping influence on the music performed by

Roma in Hungary. Varga (1992) attributes this influence to the group's having ob-

tained a recording contract, as fellow Roma were thereby convinced that Hungarians

would no longer look derisively on Romani-language singing. The polished nature of

Kalyi Jag's performances was also quite striking, according to a member of the vil-

lage folklór group Phrala Sam (Toldi 1997). Kalyi Jag's style comprises part of a

larger regional and ethnic influence that pervades folklór music. Many influential

folklór musicians, among them the founders of the groups Kale Jakha (Black Eyes),

Ando Drom (On the Journey) and Rományi Rota (Romani Wheel), came from

Varga' s home village, Nagyecsed, and the Churar ethnic group.

In the view of Jenó Zsigó, a Rom activist, political spokesman, and leader of the

group Ando Drom, the government also had to effect a change in policy before Hun-

garian or Rom audiences could be consistently exposed to folklór music.

Until the beginning of the 1980s, the Gypsy people could appear neither as ethnic

group nor as nationality in Hungarian political discourse. This meant that according to

official politics, Gypsy culture did not even exist. After some time, the Hungarian

Communist Party (MSzMP) became forced to refine something out of this completely

absurd political, unconstitutional position. Therefore they gave concessions in the area

of culture. During this time the number of Gypsy tradition-preserving (hagyomány-

õrzõ) ensembles grew by leaps (Barabás 1991:25; emphasis in original)

Therefore, in spite of the fact that the government did not officially recognize

Roma as a political or cultural entity, artistic activities were allowed. Nonetheless,

early Rom folklór performers recall that access to standard performance forums like

festivals, the recording industry, and youth camps entailed a great deal of struggle.

This content downloaded from

157.181.112.231 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 09:47:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lange. Hungarian Rom ( Gypsy) Political Activism • 23

By the mid- 1 980s, folklór groups served a variety of purposes in Rom communi-

ties. Political protests were disguised folklór performances at the end of the social-

ist period. In 1989 Roma who had obtained permission from the authorities to give a

cultural program in the city of Miskolc utilized the occasion to raise objections to the

"Miskolc ghetto" plan for segregated housing districts (Ladányi 1991). The group

Ando Drom, under Jenó Zsigó, sponsored concert series in the early 1990s which

were oriented towards fellow Roma, and they subsequently established a concert

presence in Western Europe. The lead singers of folklór groups from Esztergom,

Szolnok, and Budapest became important at wedding festivities held by wealthy

Roma (Balogh 1996).

Folklór music helped introduce the idea, which was later codified in Hungary's

1993 law on minorities, that Roma have claims and status equal to that of other ethnic

minorities in Eastern Europe. Folklór music was important because the debate over

equal treatment for Roma was framed to an extreme degree in terms of cultural legit-

imacy. By emphasizing a musical style that conforms to the dominant ideas of gen-

tleness and refinement, and by persistently seeking venues for public exposure, Hun-

garian Roma transformed the views of outsiders toward their music. Th e folklór style

now continues to act inwardly as a means of community organization.

Notes

1 This essay is based on fieldwork conducted with Roma of several different ethnic groups in

Hungary in 1991-92, 1994, 1996, and 1997. The data includes recordings of folklór music (see

selected discography), oral histories gathered from key folklór figures, interviews in Rom-

edited publications, and observations of folklór festivals, concert series, and teaching sessions

conducted from 1991-1992. Research funds were provided by the International Research and

Exchanges Board and ACCELS. The funds of the IREX grant were provided by the National

Endowment for the Humanities and the United States Information Agency. None of these

organizations is responsible for the views expressed. I am grateful to Gusztáv Varga, Gusztáv

"Bodi" Varga, Jánoš Balogh and his family, Katalin Kovalcsik, Irén Kertész-Wilkinson, Alice

Egyed, and numerous Rom acquaintances for their many helpful comments. All translations

are mine.

Rom/ Roma/ Romani (singular/plural/adjective) will be used as general designations here.

In the Hungarian language, the root word Roma is currently utilized, rather than Rom. Activ-

ists prefer these terms to the word "Gypsy," which often has derogatory connotations in Hun-

gary. The word "Gypsy" is retained in translations and where references are made to the public

images of Roma.

2 There are three broad subdivisions of Roma in Hungary, determined by language. All are

bilingual, speaking the Hungarian language in addition to other languages or dialects. Romun-

gre, or Hungarian Gypsies, once spoke Carpathian Romani but now the great majority speak

Romani-inflected Hungarian. One of their traditional occupations was that of professional

string musician. Boyashes speak Romanian; Vlach Roma speak Vlax Romani. There are other

ethnic and occupational groups within these three, particularly among the Vlach Roma (see

Erdõs 1960; Kemény 1974; Kovalcsik 1996).

This content downloaded from

157.181.112.231 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 09:47:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

24 • the world of music 39(3)- 1997

3 Recordings of rural Rom singing in Hungary include: Rom Sam Ame (Fonti Musicali fmd

194); Magyarországi cigány népdalok. Gypsy Folksongs from Hungary (Hungaroton SLPX

12028-29); and Szabolcs-Szatmári cigány népdalok. Folk Songs by Hungarian Gipsies (Hun-

garoton SLPX 18082).

4 See field recordings from the town of Gyöngyös in the archives of the Hungarian Musicology

Institute (13709a-b) and from Szolnok and Szigetvár at the University of Washington (UWEA

94-27.62b; UWEA 94-27.38Ò).

5 Gábor Grabócz produced recent recordings of Romani-language songs in translation, per-

formed by Apollonia Kovács (. Apollonia . 1984, Qualiton SLPM 10190; Cigánydalok. Gypsy

Songs. 1988, Qualiton SLPM 10277).

6 Transcriptions of the music and texts were published by Csenki's brother Imre (Csenki and

Pászti 1955; Csenki and Csenki 1977, 1980). The singers were re-recorded several decades

later (Pöspökladänyi cigány népdalok. Hungarian Gypsy folk songs. 1993, Hungaroton Clas-

sic/Cigány Ház-Romano Kher MK 18172).

7 An ongoing debate in scholarly circles about the level of originality in Rom music and culture

continued into the 1980s because the government gave institutional support to scholarship that

supported the assimilationist point of view (see summaries in Kovalcsik 1988b, Réger 1988).

8 Other institutional guarantees included free use of the minority language, translation services,

laws against ethnic slurs, minority student residences (collegiums), schools, minority language

publications (including newspapers), adult education courses, and a separate division in the

Cultural Education Ministry (Népmuvelési Miniszterium) (Nagy 1955:9-13).

9 The 1961 party declaration stated, "Many people comprehend this issue as a nationality ques-

tion and recommend the development of the 'Gypsy language' and the establishment of Gypsy

language schools, collegiums, and agricultural coops. These viewpoints are not only erroneous

but also harmful because they preserve the separation of the Gypsies and slow down their inte-

gration into society" (Mezey 1986:240).

10 The music was sometimes called pol-beat. This designation is rejected by Monszun members.

János Sebok's two- volume series Magya-rock (1983-84) summarizes the styles, histories, and

personnel of contemporaneous pop groups. These books only refer obliquely to the currents of

dissidence in Hungarian popular music. Because youth musical groups were independently

formed and organized, if they began to attract large constituencies, the state often treated them

as potential sources of opposition. For questions of overt dissidence in 1980s popular music,

see Kürti 1991.

1 1 Ironically, the musicians who served as a village source of instrumental music repertoire for

the Hungarian dance-house revival were Roma; the vocal repertoire came from village Hun-

garians. The Hungarian revival musicians dominated performance, recording, and broadcast

venues. Most source musicians never performed live for the Hungarian public until after the

1989 revolutions, because they resided in the Hungarian ethnic enclaves of Romania.

12 Dance-house participants also had to initially break down institutional rigidity, particularly

where media exposure and the judging of contests was concerned (Frigyesi 1996:71-72,

Balázs 1983).

This content downloaded from

157.181.112.231 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 09:47:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lange. Hungarian Rom ( Gypsy) Political Activism • 25

References

Anonymous

1992 Personal communication, Miskolc, Hungary, July 1992.

Balázs, Jánoš

1983 "Young People's Folk Music Movement in Hungary: Revival or Failure?" Internation-

al Society for Music Education Yearbook 10:36-45.

Balogh, Jánoš

1992 Interview, Budapest, Hungary, April 1992.

1994 Personal communication, Budapest, Hungary, May 1994.

1996 Personal communication, Budapest, Hungary, January 1996.

Bankó, András

1990 "Képmutató lett a világ" (The World Has Betrayed Us). Magyar Nemzet , 1 1 March, 4.

Barabás, Klára

1991 "Ando Drom (Útkôzben)" (On the Journey). Phralipe 1991(3):25.

Bársony, Jánoš

1996 Interview, Budapest, January 1996.

Bársony, Júlia

1996 Personal communication, Baltimore, MD, November 1996.

Bartók, Béla

1947 [1931] "Gypsy Music or Hungarian Music?" Musical Quarterly 33(2):240-57.

1952 [1934] Népzenénk és a szomszéd népek népzenéje. (Our Folk Music and the Folk Music of

Neighboring Peoples). Budapest: Zenemükiadó Vállalat.

Blaha, Márta

1994 "Az Amalipe '94-es tervei" (Amalipe's 1994 Plans). Interview with Jánoš Balogh.

Amalipe Inf ormációs fiizet 4 (Apríl 1994):6-8.

Bodi Varga, Gusztáv

1992 Personal communication, Budapest, Hungary, April 1992.

Bourdieu, Pierre

1984 Distinction : A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. London: Routledge and Keg-

an Paul.

Chernoff, John Miller

1979 African Rhythm and African Sensibility. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Csalog, Zsolt

1984 "Jegyzetek a cigányság támogatásának kerdéseirõl" (Notes on Questions of Assisting

the Gypsy People). Szociálpolitikai Értesítõ 1984 (2):36-79.

Csenki, Imre, and Sándor Csenki

1977 Cigány népdalok és táncok (Gypsy Folk songs and Dances). Budapest: Zenemükiadó.

1980 Cigány népballadák és keservesek (Gypsy Ballads and Laments). Budapest: Europa

Kônyvkiadó.

Csenki, Imre, and Miklós Pászti

1955 Bazsarózsa. 99 cigány népdal (Peony. 99 Gypsy Folksongs). Budapest: Zenemükiadó.

This content downloaded from

157.181.112.231 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 09:47:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

26 • the world of music 39(3)- 1997

Daróczi, Agnes

1996 Interview, Budapest, Hungary, January 1996.

Dobszay, László

1 99 1 "Introduction." In Catalogue of Hungarian Folksong Types I. László Dobszay and Jan-

ka Szendrei, eds. Budapest: Institute for Musicology of the Hungarian Academy of Sci-

ences, 7-53.

Erdós, Kamill

1960 "A Classification of Gypsies in Hungary." Acta Orientalia 10(l):79-82.

Frigyesi, Judit

1994 "Béla Bartók and the Concept of Nation and Volk in Modern Hungary." Musical Quar-

terly 78 (Summer): 255-87.

1996 "The Aesthetic of the Hungarian Revival Movement." In Retuning Culture. Mark

Slobin, ed., Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 54-75.

Goffman, Erving

1963 Stigma; Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Pren-

tice-Hall.

Grabócz, Gábor and Katalin Kovalcsik, eds. and collectors

1988 Mihály Rostás, a Story-Teller. Hungarian Gypsy Studies 5. Budapest: MTA Néprajzi

Kutató Csoport.

Gronemeyer, Reimer

1981 "Unaufgeräumte Hinterzimmer." In Kumpania und Kontrolle: Moderne Behinderun-

gen zigeunerischen Lebens. Mark Miinzel and Bernhard Streck, eds. Giessen: Focus,

193-224.

Hajdu, André

1958 "Les tsiganes de hongrie et leur musique." Études Tsiganes 4(l):4-28.

Hammond, Thomas T.

1966 "Nationalism and National Minorities in Eastern Europe." Journal of International Af-

fairs 20(1):9-31.

Hankiss, Elemér

1988 "The 'Second Society': Is There an Alternative Social Model Emerging in Contempo-

rary Hungary?" Social Research 55( 1-2): 1 3-42.

Havas, Gábor (Fölöp Endre)

1991 [1988] "Politikai sztflusgyakorlatok kezdóknek" (Political Style Exercises for Beginners).

Phralipe 2(5): 18-24. (First published in Beszélõ no. 23, 1988).

Hegedüs, T. András

1989 "A cigányság képe a magyar sajtóban (1985-1986)" (The Picture of Gypsies in the

Hungarian Press, 1985-1986). Kultura és Kôzosség 1989(1):68- 79.

Huseby-Darvas, Èva

1989 "Migration and Gender: Perspectives from Rural Hungary." East European Quarterly

23(4):487-98.

Javorniczky, István

1986 "'Hiszek neked, te jó vagy !' Cigányklubokról és egyebekról Daróczi Ágnessel" (I Be-

lieve You, You Are Good! With Ágnes Daróczi on Gypsy Clubs and Other Subjects).

This content downloaded from

157.181.112.231 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 09:47:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lange. Hungarian Rom ( Gypsy) Political Activism • 27

In Egyszer karolj át egy fát ! Cigány almanach. Gábor Murányi, ed. Budapest: TIT

Országos Központja Cigány Ismeretterjesztó Bizottsága, 218-30.

Kartomi, Margaret

1 98 1 "The Processes and Results of Musical Culture Contact: A Discussion of Terminology

and Concepts." Ethnomusicology 25:227-50.

Kemény, István

1974 "A magyarországi cigány lakosság" (The Hungarian Gypsy Population). Valóság

1974(1):63- 72.

Kertész-Wilkinson, Irén

1990 "Lokes Phen! An Investigation into the Musical Tempo Feeling of a Hungarian Gypsy

Community Based on their own Evaluation." In 100 Years of Gypsy Studies. Matt T.

Salo, ed. Cheverly, MD: The Gypsy Lore Society, 193-201.

1 992 "Genuine and Adopted Songs in the Vlach Gypsy Repertoire: A Controversy Re-exam-

ined." British Journal of Ethnomusicology 1:11 1-34.

Kovalcsik, Katalin

1981 "A szatmár megyei oláh cigányok lassù dalainak tôbbszolamúsága" (Polyphony in the

Slow Songs of Szatmár County Vlach Gypsies). Zenetudományi dolgozatok:26'-l'.

1985 Vlach Gypsy Songs in Slovakia. Gypsy Folk Music of Europe 1 . Budapest: Institute for

Musicology of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

1 987a Jacket notes to Kalyi Jag. " Black Fire. " Hungaroton SLPX 1 8 1 32.

1987b "Popular Dance Music Elements in the Folk Music of Gypsies in Hungary." Popular

Music 6(l):45-65.

1988a "A Beás cigány népzene szisztematikus gyüjtésének elsó tapasztalatai" (The First Ex-

periences of Systematic Collection of Boyash Gypsy Folk Music). Zenetudományi

dolgozatok : 2 1 5-33 .

1988b "Hazai írások a cigány zenéról" (Hungarian Writings on Gypsy Music). Mu-

helymunkák a nyelvészet és társtudományai kôrébõl 4:101-15.

1996 "Roma or Boyash Identity? The Music of the 'Ard'elan' Boyashes in Hungary." the

world of music 38(l):77-93.

1997 "The Aesthetics of the Gypsy Folk Music Movement in Hungary." Paper presented at

the 34th World Conference of the International Council for Traditional Music, Nitra,

Slovakia, June 25-July 2, 1997.

Kürti, László

1991 "Rocking the State: Youth and Rock Music Culture in Hungary, 1976-1990." East Eu-

ropean Politics and Societies 5(3):483-5 13.

Ladányi, József

1991 "A miskolci gettóiigy" (The Miskolc Ghetto Affair). Valóság 1991(4):45-54.

Lange, Barbara Rose

1 996 "Lakodalmas Rock and the Rejection of Popular Culture in Post-Socialist Hungary." In

Returning Culture. Mark Slobin, ed. Durham: Duke University Press, 76-91.

Losonczi, Agnes

1969 A zeneéletének szociológiája (The Sociology of Musical Life). Budapest: Zenemuki-

adó.

This content downloaded from

157.181.112.231 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 09:47:04 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

28 • the world of music 39(3)- 1997

Martin, György

1980 "A cigányság hagyományai és szerepe a kelet-európai népek tánckultúrájában" (The

Traditions and Role of the Gypsy People in the Dance Culture of the East European

Peoples). Zenetudományi dolgozatok:61-14.

Marton, Dénes

1996 Personal communication, Houston, TX, October 1996.

Mercer, Kobena