Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Clinical Use of Blood - Handbook: Search Topics Titles Organizations Keywords

The Clinical Use of Blood - Handbook: Search Topics Titles Organizations Keywords

Uploaded by

kaminiOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Clinical Use of Blood - Handbook: Search Topics Titles Organizations Keywords

The Clinical Use of Blood - Handbook: Search Topics Titles Organizations Keywords

Uploaded by

kaminiCopyright:

Available Formats

Home page | About this library | Help | Clear English | French | Spanish

Search | Topics | Titles A-Z | Organizations | Keywords

Expand Document Expand Chapter Full TOC Preferences

The Clinical Use of Blood - Handbook (WHO; 2002; 222 pages)

Introduction

The appropriate use of blood and blood products

Replacement fluids

Blood products

Clinical transfusion procedures

Adverse effects of transfusion

Clinical decisions on transfusion

General medicine

Obstetrics

Paediatrics & neonatology

Key points

Paediatric anaemia

Transfusion in special clinical situations

Printable version

Bleeding and clotting disorders

Export document as HTML file Thrombocytopenia

Help

Neonatal transfusion

Export document as PDF file

Surgery & anaesthesia

Acute surgery & trauma

Burns

Glossary

Back cover

Paediatric anaemia

Paediatric anaemia is defined as a reduction of haemoglobin concentration or red cell blood volume below the normal values for healthy

children. Normal haemoglobin/haematocrit values differ according to the child’s age.

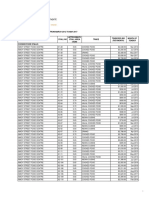

Age Haemoglobin concentration (g/dl)

Cord blood (term) ± 16.5 g/dl

Neonate: Day 1 ± 18.0 g/dl

1 month ± 14.0 g/dl

3 months ± 11.0 g/dl

6 months-6 years ± 12.0 g/dl

7-13 years ± 13.0 g/dl

http://helid.digicollection.org/en/d/Js2882e/10.2.html 10/11/18, 4:19 PM

Page 1 of 5

> 14 years Same as adults, by sex

Causes

Very young children are at particular risk of severe anaemia. The majority of paediatric transfusions are given to children under three years

of age. This is due to a combination of the following factors occurring during a rapid growth phase when blood volume is expanding:

• Iron-poor weaning diets

• Recurrent or chronic infection

• Haemolytic episodes in malarious areas.

A severely anaemic child with other illness (e.g. acute infection), has a high risk of mortality. As well as treating the anaemia, it is

essential to look for and treat other conditions: e.g. diarrhoeal disease, pneumonia and malaria.

Prevention

The most effective and cost-effective means of preventing anaemia-associated mortality and the use of blood transfusion is to prevent

severe anaemia by:

• Early detection of anaemia

• Effective treatment and prophylaxis of the underlying causes of anaemia

• Clinical monitoring of children with mild and moderate anaemia.

CAUSES OF PAEDIATRIC ANAEMIA

Decreased production of normal red blood cells

• Nutritional deficiencies due to insufficient intake or absorption (iron, B12, folate)

• HIV infection

• Chronic disease or inflammation

• Lead poisoning

• Chronic renal disease

• Neoplastic diseases (leukaemia, neoplasms invading bone marrow)

Increased destruction of red blood cells

• Malaria

• Haemoglobinopathies (sickle cell disease, thalassaemia)

• G6PD deficiency

• Rh D or ABO incompatibility in the newborn

• Autoimmune disorders

• Spherocytosis

Loss of red blood cells

• Hookworm infection

• Acute trauma

• Surgery

• Repeated diagnostic blood sampling

Clinical assessment

Clinical assessment of the degree of anaemia should be supported by a reliable determination of haemoglobin or haematocrit.

Prompt recognition and treatment of malaria (see pp. 95-97) and any associated complications can be life-saving since death can

occur within 48 hours.

Management of compensated anaemia

In children, as in adults, the body’s mechanisms to compensate for chronic anaemia often means that very low haemoglobin levels can be

tolerated with few or no symptoms, provided anaemia develops slowly over weeks or months.

A child with well-compensated anaemia may have:

http://helid.digicollection.org/en/d/Js2882e/10.2.html 10/11/18, 4:19 PM

Page 2 of 5

• Raised respiratory rate

• Increased heart rate

But will be:

• Alert

• Able to drink or breastfeed

• Normal, quiet breathing, with abdominal movement

• Minimal chest movement

Management of decompensated anaemia

Many factors can precipitate decompensation in an anaemic child and lead to life-threatening hypoxia of tissues and organs.

Causes of decompensation

1 Increased demand for oxygen:

• Infection

• Pain

• Fever

• Exercise

2 Further reduction in oxygen supply

• Acute blood loss

• Pneumonia

Early signs of decompensation

• Laboured, rapid breathing with intercostal, subcostal and suprasternal retraction/recession (respiratory distress)

• Increased use of abdominal muscles for breathing

• Flaring of nostrils

• Difficulty with feeding

Signs of acute decompensation

• Forced expiration (‘grunting’)/respiratory distress

• Mental status changes

• Diminished peripheral pulses

• Congestive cardiac failure

• Hepatomegaly

• Poor peripheral perfusion (capillary refill greater than 2 seconds)

Supportive treatment

Immediate supportive treatment is needed if the child is severely anaemic with:

• Respiratory distress

• Difficulty in feeding

• Congestive cardiac failure

• Mental status changes.

A child with these clinical signs needs urgent treatment as there is a high risk of death due to insufficient oxygen carrying-

capacity.

MANAGEMENT OF SEVERE DECOMPENSATED ANAEMIA

1 Position the child and airway to improve ventilation: e.g. sitting up.

2 Give high concentrations of oxygen to improve oxygenation.

3 Take blood sample for crossmatching, haemoglobin estimation and other relevant tests.

4 Control temperature or fever to reduce oxygen demands:

• Cool by tepid sponging

• Give antipyretics: e.g. paracetamol.

http://helid.digicollection.org/en/d/Js2882e/10.2.html 10/11/18, 4:19 PM

Page 3 of 5

5 Treat volume overload and cardiac failure with diuretics: e.g. frusemide, 2 mg/kg by mouth or 1 mg/kg intravenously to a maximum

dose of 20 mg/24 hours.

The dose may need to be repeated if signs of cardiac failure persist.

6 Treat acute bacterial infection or malaria.

REASSESSMENT

1 Reassess before giving blood as children often stabilize with diuretics, positioning and oxygen.

2 Clinically assess the need for increased oxygen-carrying capacity.

3 Check haemoglobin concentration to determine severity of anaemia.

Severely anaemic children are, contrary to common belief, rarely in congestive heart failure, and dyspnoea is due to acidosis. The sicker

the child, the more rapidly transfusion needs to be started.

Transfusion

The decision to transfuse should not be based on the haemoglobin level alone, but also on a careful assessment of the child’s

clinical condition.

Both laboratory and clinical assessment are essential. A child with moderate anaemia and pneumonia may have more need of increased

oxygen-carrying capacity than one with a lower haemoglobin who is clinically stable.

If the child is stable, is monitored closely and is treated effectively for other conditions, such as acute infection, oxygenation may improve

without the need for transfusion.

INDICATIONS FOR TRANSFUSION

1 Haemoglobin concentration of 4 g/dl or less (or haematocrit 12%), whatever the clinical condition of the patient.

2 Haemoglobin concentration of 4-6 g/dl (or haematocrit 13-18%) if any the following clinical features are present:

• Clinical features of hypoxia:

- Acidosis (usually causes dyspnoea)

- Impaired consciousness

• Hyperparasitaemia (>20%).

The procedure for paediatric transfusion is shown on p. 142.

Special equipment for paediatric and neonatal transfusion

Never re-use an adult unit of blood for a second paediatric patient because of the risk of bacteria entering the pack during the

first transfusion and proliferating while the blood is out of the refrigerator.

• Where possible, use paediatric blood packs which enable repeat transfusions to be given to the same patient from a

single donation unit. This reduces the risk of infection

• Infants and children require small volumes of fluid and can easily suffer circulatory overload if the infusion is not well-

controlled. If possible, use an infusion device that makes it easy to control the rate and volume of infusion.

TRANSFUSION PROCEDURE

1 If transfusion is needed, give sufficient blood to make the child clinically stable.

2 5 ml/kg of red cells or 10 ml/kg whole blood are usually sufficient to relieve acute shortage of oxygen carrying-capacity. This will

http://helid.digicollection.org/en/d/Js2882e/10.2.html 10/11/18, 4:19 PM

Page 4 of 5

increase haemoglobin concentration by approximately 2-3 g/dl unless there is continued bleeding or haemolysis.

3 A red cell transfusion is preferable to whole blood for a patient at risk of circulatory overload, which may precipitate or worsen cardiac

failure. 5 ml/kg of red cells gives the same oxygen-carrying capacity as 10 ml/kg of whole blood and contains less plasma protein and

fluid to overload the circulation.

4 Where possible, use a paediatric blood pack and a device to control the rate and volume of transfusion and

5 Although rapid fluid infusion increases the risk of volume overload and cardiac failure, give the first 5 ml/kg of red cells to relieve the

acute signs of tissue hypoxia. Subsequent transfusion should be given slowly: e.g. 5 ml/kg of red cells over 1 hour.

6 Give frusemide 1 mg/kg by mouth or 0.5 mg/kg by slow IV injection to a maximum dose of 20 mg/kg if patient is likely to develop

cardiac failure and pulmonary oedema. Do not inject it into the blood pack.

7 Monitor during transfusion for signs of:

• Cardiac failure

• Fever

• Respiratory distress

• Tachypnoea

• Hypotension

• Acute transfusion reactions

• Shock

• Haemolysis (jaundice, hepatosplenomegaly)

• Bleeding due to DIC.

8 Re-evaluate the patient’s haemoglobin or haematocrit and clinical condition after transfusion.

9 If the patient is still anaemic with clinical signs of hypoxia or a critically low haemoglobin level, give a second transfusion of 5-10 ml/kg

of red cells or 10-15 ml/kg of whole blood.

10 Continue treatment of anaemia to help haematological recovery.

Please provide your feedback English | French | Spanish

http://helid.digicollection.org/en/d/Js2882e/10.2.html 10/11/18, 4:19 PM

Page 5 of 5

You might also like

- Sandal Magna Primary SchoolDocument36 pagesSandal Magna Primary SchoolsaurabhNo ratings yet

- Hematological Disorders of NewbornDocument98 pagesHematological Disorders of Newbornlieynna499650% (2)

- AABB Pediatric Transfusion - Risks and GuidelinesDocument57 pagesAABB Pediatric Transfusion - Risks and GuidelinesDR.RAJESWARI SUBRAMANIYANNo ratings yet

- Pediatric NursingDocument105 pagesPediatric NursingPaida P. Abdulmalik75% (4)

- 1 Childhood Nephrotic Syndrome - Diagnosis and ManagementDocument52 pages1 Childhood Nephrotic Syndrome - Diagnosis and ManagementNilupul Niwantha100% (1)

- The Child With Hematologic DisordersDocument149 pagesThe Child With Hematologic DisordersNics FranciscoNo ratings yet

- Hemolytic DiseaseDocument10 pagesHemolytic DiseaseChino Paolo SamsonNo ratings yet

- Patent Ductus Arteriosus - Nov 20 FDocument11 pagesPatent Ductus Arteriosus - Nov 20 FZwinglie SandagNo ratings yet

- AnemiaDocument43 pagesAnemiapradeep pintoNo ratings yet

- Dengue Fever Management - Pediatrics SeminarDocument106 pagesDengue Fever Management - Pediatrics SeminarAimhigh_PPMNo ratings yet

- MRCPCH Paper1B Best of Five NeonateDocument8 pagesMRCPCH Paper1B Best of Five NeonateCherryNo ratings yet

- Pneumonia: Clinical DescriptionDocument14 pagesPneumonia: Clinical DescriptionNama ManaNo ratings yet

- Management of Fluid Status in Haemodialysis Patients: The Roles of Technology and Dietary AdviceDocument15 pagesManagement of Fluid Status in Haemodialysis Patients: The Roles of Technology and Dietary AdviceRuwaedaNasruddinNo ratings yet

- SCD and Hydroxyurea TherapyDocument29 pagesSCD and Hydroxyurea Therapysamuel waiswaNo ratings yet

- POLYCYTHEMIADocument14 pagesPOLYCYTHEMIAPrajwal Kumar JhaNo ratings yet

- Update On (Approach To) Anemia1 (Changes)Document39 pagesUpdate On (Approach To) Anemia1 (Changes)Balchand KukrejaNo ratings yet

- Hypovolemic Shock Nursing Care Management and Study GuideDocument1 pageHypovolemic Shock Nursing Care Management and Study GuideRoselyn VelascoNo ratings yet

- Neonatal and Pediatric Transfusion Practice: Cassandra D. Josephson, MD, and Erin Meyer, DO, MPHDocument28 pagesNeonatal and Pediatric Transfusion Practice: Cassandra D. Josephson, MD, and Erin Meyer, DO, MPHpro earnerNo ratings yet

- 1 Childhood Nephrotic Syndrome - Diagnosis and ManagementDocument52 pages1 Childhood Nephrotic Syndrome - Diagnosis and ManagementThana Balan100% (1)

- 8BBK Lec8 - HDN MQA 2019-09-26 08 - 14 - 44Document32 pages8BBK Lec8 - HDN MQA 2019-09-26 08 - 14 - 44gothai sivapragasamNo ratings yet

- CPG IP Pneumonia-AdultDocument15 pagesCPG IP Pneumonia-Adultkarthi keyanNo ratings yet

- Wa0002 PDFDocument4 pagesWa0002 PDFVivin KarlinaNo ratings yet

- Pediatric AnesthesiaDocument70 pagesPediatric AnesthesiaEliyan KhanimovNo ratings yet

- DehydrationDocument17 pagesDehydrationLaura Anghel-MocanuNo ratings yet

- Blood Transfusion in Pediatrics - Dr. RiniDocument55 pagesBlood Transfusion in Pediatrics - Dr. RiniAndyani PratiwiNo ratings yet

- Amniotic Fluid EmbolismDocument51 pagesAmniotic Fluid EmbolismDenyse Mayer Atutubo100% (2)

- Syok - Anzak Akbar Andin PangeDocument34 pagesSyok - Anzak Akbar Andin PangeannisazakirohNo ratings yet

- Acute GlomerulonephritisDocument6 pagesAcute GlomerulonephritisAnsu MaliyakalNo ratings yet

- Anemia in Pregnancy B.JDocument39 pagesAnemia in Pregnancy B.JBhawna JoshiNo ratings yet

- NCBI Bookshelf-Diabetes InsipidusDocument44 pagesNCBI Bookshelf-Diabetes InsipidusDiah Pradnya ParamitaNo ratings yet

- Hypernatremic Dehydration in Newborn Infants: A Review: July 2015Document5 pagesHypernatremic Dehydration in Newborn Infants: A Review: July 2015medibase12No ratings yet

- Deteriorating PatientDocument39 pagesDeteriorating PatientDoc EddyNo ratings yet

- Pediatric HandbookDocument201 pagesPediatric HandbookJoseph MensaNo ratings yet

- Iron and SCD AnemiaDocument28 pagesIron and SCD Anemiariadharthy2No ratings yet

- Febrile NuetropeniaDocument4 pagesFebrile NuetropeniayuliNo ratings yet

- Case Study - Nephrotic SyndromeDocument42 pagesCase Study - Nephrotic Syndromefarmasi rsud cilincingNo ratings yet

- MaeDocument9 pagesMaeCharmaigne Mae Padilla Sotelo100% (1)

- Pulmonary Haemorrhage: Section: 2 Respiratory Problems and ManagementDocument2 pagesPulmonary Haemorrhage: Section: 2 Respiratory Problems and ManagementЛена ДуминикNo ratings yet

- Management of Neonatal Hypotension and ShockDocument7 pagesManagement of Neonatal Hypotension and ShockntnquynhproNo ratings yet

- Management of Neonatal Hypotension and ShockDocument7 pagesManagement of Neonatal Hypotension and ShockntnquynhproNo ratings yet

- Anemia Neonatus MhsDocument32 pagesAnemia Neonatus MhsTria100% (1)

- Plan of CareDocument4 pagesPlan of CareNicole SedaNo ratings yet

- 13pediatric ConsiderationsDocument4 pages13pediatric ConsiderationsIna PoianaNo ratings yet

- Nephrotic SyndromeeDocument28 pagesNephrotic SyndromeeRiteka SinghNo ratings yet

- 101 FullDocument15 pages101 FullhelinNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Physiology: Presented By: Mohammad El-Masri Moderated By: Dr. Omar AbabnehDocument41 pagesPediatric Physiology: Presented By: Mohammad El-Masri Moderated By: Dr. Omar AbabnehMorad SatariNo ratings yet

- Compensated Dengue Shock Syndrome (A97.2) and Obesity (E.661)Document3 pagesCompensated Dengue Shock Syndrome (A97.2) and Obesity (E.661)NyomanGinaHennyKristiantiNo ratings yet

- Blood Pressure Management in Children On DialysisDocument12 pagesBlood Pressure Management in Children On DialysisinaNo ratings yet

- NCM 109 Lecture: Nursing Care of A Child With Hematologic DisorderDocument95 pagesNCM 109 Lecture: Nursing Care of A Child With Hematologic DisorderAmiscua Pauline AnneNo ratings yet

- Renal Replacement TherapyDocument50 pagesRenal Replacement TherapyMalueth Angui100% (1)

- Fluid and ElectrolytesDocument135 pagesFluid and ElectrolytesLindsay PinedaNo ratings yet

- Acute Glomerulonep Hritis: By: Edelrose D. Lapitan BSN Iii-CDocument29 pagesAcute Glomerulonep Hritis: By: Edelrose D. Lapitan BSN Iii-CEdelrose Lapitan100% (1)

- Fresh Frozen Plasma: Plasma Is The Clear, Pale-Yellow Liquid Part of BloodDocument5 pagesFresh Frozen Plasma: Plasma Is The Clear, Pale-Yellow Liquid Part of BloodsashaNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Hypertension: Why The Rise in Childhood Hypertension?Document9 pagesPediatric Hypertension: Why The Rise in Childhood Hypertension?Peace ManNo ratings yet

- 12 FullDocument4 pages12 FullyesumovsNo ratings yet

- Nephrotic SyndromeDocument28 pagesNephrotic Syndromerupali khillareNo ratings yet

- A 12Document19 pagesA 12NestleNo ratings yet

- Pulmonary Hemorrhage: Dr. Habibur RahimDocument46 pagesPulmonary Hemorrhage: Dr. Habibur Rahimallaaobeid1987No ratings yet

- Hematological Alterations: Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC)Document16 pagesHematological Alterations: Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC)jhommmmmNo ratings yet

- Labs & Imaging for Primary Eye Care: Optometry In Full ScopeFrom EverandLabs & Imaging for Primary Eye Care: Optometry In Full ScopeNo ratings yet

- Eight Cases That Will Test Whether 'Basic Structure Doctrine' Can Safeguard India's DemocracyDocument19 pagesEight Cases That Will Test Whether 'Basic Structure Doctrine' Can Safeguard India's DemocracykaminiNo ratings yet

- Adventure 10 - "The Adventure of The Noble Bachelor" - The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes - Sir Arthur Conan Doyle - Lit2Go ETCDocument12 pagesAdventure 10 - "The Adventure of The Noble Bachelor" - The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes - Sir Arthur Conan Doyle - Lit2Go ETCkaminiNo ratings yet

- In The Supreme Court of India Civil Appellate JurisdictionDocument23 pagesIn The Supreme Court of India Civil Appellate JurisdictionkaminiNo ratings yet

- List of Counsels Nominated With Delhi High CourtDocument64 pagesList of Counsels Nominated With Delhi High CourtkaminiNo ratings yet

- The Development of The Anti-Cruelty Laws During The 1800's - Animal Legal & Historical CenterDocument33 pagesThe Development of The Anti-Cruelty Laws During The 1800's - Animal Legal & Historical CenterkaminiNo ratings yet

- Writ of Mandamus On Commissioner of Police, Mumbai - Save Indian Family FoundationDocument21 pagesWrit of Mandamus On Commissioner of Police, Mumbai - Save Indian Family FoundationkaminiNo ratings yet

- CDC - Rabies Around The World - RabiesDocument1 pageCDC - Rabies Around The World - RabieskaminiNo ratings yet

- Cause List: 011-28031838 011-28032406 Fax No. 28032381Document71 pagesCause List: 011-28031838 011-28032406 Fax No. 28032381kaminiNo ratings yet

- Simple Ways To Test Dogs For Rabies - 9 Steps (With Pictures)Document5 pagesSimple Ways To Test Dogs For Rabies - 9 Steps (With Pictures)kaminiNo ratings yet

- 2Document25 pages2kaminiNo ratings yet

- Global Freedom of Expression - Shreya Singhal v. Union of India - Global Freedom of ExpressionDocument4 pagesGlobal Freedom of Expression - Shreya Singhal v. Union of India - Global Freedom of ExpressionkaminiNo ratings yet

- Bidding ManualDocument8 pagesBidding ManualkaminiNo ratings yet

- Public Health - Rabies in IndiaDocument6 pagesPublic Health - Rabies in IndiakaminiNo ratings yet

- Upload 8222Document7 pagesUpload 8222kaminiNo ratings yet

- 27.10.2021 For Website Upload (2) 21102021Document42 pages27.10.2021 For Website Upload (2) 21102021kaminiNo ratings yet

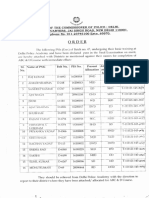

- Office of The Commissioner of Police: Delhi.: Cancellation of Transfer OrderDocument2 pagesOffice of The Commissioner of Police: Delhi.: Cancellation of Transfer OrderkaminiNo ratings yet

- Office of The Commissioner of Police: Delhi.: Tele/Fax No. 011-234739J4, Extn.-72934Document2 pagesOffice of The Commissioner of Police: Delhi.: Tele/Fax No. 011-234739J4, Extn.-72934kaminiNo ratings yet

- ( '/"i J :/ /:"/ ,/ R S:: SJ!LCFDocument2 pages( '/"i J :/ /:"/ ,/ R S:: SJ!LCFkaminiNo ratings yet

- Annexure 1Document16 pagesAnnexure 1kaminiNo ratings yet

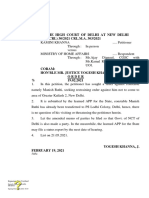

- In The High Court of Delhi at New Delhi W.P. (CRL) 30/2021 CRL.M.A. 303/2021Document1 pageIn The High Court of Delhi at New Delhi W.P. (CRL) 30/2021 CRL.M.A. 303/2021kaminiNo ratings yet

- Upload 8216Document2 pagesUpload 8216kaminiNo ratings yet

- Government: NOT Fie AT' NDocument2 pagesGovernment: NOT Fie AT' NkaminiNo ratings yet

- Office of The Commissioner of Police: Di/941.16950193 143-OorbDocument3 pagesOffice of The Commissioner of Police: Di/941.16950193 143-Oorbkamini0% (1)

- OrderDocument7 pagesOrderkaminiNo ratings yet

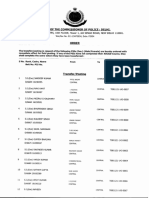

- Pouce Headquarters, 10Th Floor, Tower 1, Jai Singh Road, New Delhi 11000LDocument16 pagesPouce Headquarters, 10Th Floor, Tower 1, Jai Singh Road, New Delhi 11000LkaminiNo ratings yet

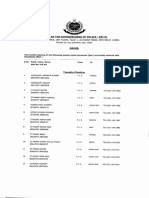

- Policeheadquarters, 10Th Floor, Tower 1, Jai Singh Road, New Delhi 11000LDocument18 pagesPoliceheadquarters, 10Th Floor, Tower 1, Jai Singh Road, New Delhi 11000LkaminiNo ratings yet

- Unpaid Unclaimed Dividend IEPF 1Document46 pagesUnpaid Unclaimed Dividend IEPF 1kaminiNo ratings yet

- Office of The Commissioner of Police: Delhi.: R-RT: '7 RDocument1 pageOffice of The Commissioner of Police: Delhi.: R-RT: '7 RkaminiNo ratings yet

- Office of The Commissioner of Police: DelhiDocument91 pagesOffice of The Commissioner of Police: DelhikaminiNo ratings yet

- Notification: Office of The Commissioner of Police: Delhi Police Headquarters, Jai Singh Road, New Delhi 110001Document1 pageNotification: Office of The Commissioner of Police: Delhi Police Headquarters, Jai Singh Road, New Delhi 110001kaminiNo ratings yet

- (GOLD) The Examples of Final Semester TestDocument8 pages(GOLD) The Examples of Final Semester TestMetiska MunzilaNo ratings yet

- Philo ExamDocument2 pagesPhilo ExamJohn Albert100% (1)

- BSI BCI Horizon Scan Report 2016 PDFDocument32 pagesBSI BCI Horizon Scan Report 2016 PDFSandraNo ratings yet

- Premier's Technology Council: A Vision For 21st Century Education - December 2010Document51 pagesPremier's Technology Council: A Vision For 21st Century Education - December 2010The Georgia StraightNo ratings yet

- What Do You Know About Jobs - 28056Document2 pagesWhat Do You Know About Jobs - 28056Kadek DharmawanNo ratings yet

- C4 Tech Spec Issue 2Document5 pagesC4 Tech Spec Issue 2Дмитрий КалининNo ratings yet

- Glossary of Professional Wrestling TermsDocument14 pagesGlossary of Professional Wrestling TermsMaría GoldsteinNo ratings yet

- InglesDocument5 pagesInglesJessi mondragonNo ratings yet

- Major Crops of Pakistan Wheat, Cotton, Rice, Sugarcane: and MaizeDocument17 pagesMajor Crops of Pakistan Wheat, Cotton, Rice, Sugarcane: and MaizeWaleed Bin khalidNo ratings yet

- Doctorine of Necessity in PakistanDocument14 pagesDoctorine of Necessity in Pakistandijam_786100% (9)

- Statistical Quality Control PPT 3 2Document18 pagesStatistical Quality Control PPT 3 2Baljeet Singh100% (1)

- Womens EssentialsDocument50 pagesWomens EssentialsNoor-uz-Zamaan AcademyNo ratings yet

- Lesson 9. Phylum Mollusca PDFDocument44 pagesLesson 9. Phylum Mollusca PDFJonard PedrosaNo ratings yet

- Identifying Figures of Speech (Simile, Metaphor, and Personification)Document10 pagesIdentifying Figures of Speech (Simile, Metaphor, and Personification)khem ConstantinoNo ratings yet

- Great by Choice - Collins.ebsDocument13 pagesGreat by Choice - Collins.ebsShantanu Raktade100% (1)

- The DJ Test: Personalised Report and Recommendations For Alex YachevskiDocument34 pagesThe DJ Test: Personalised Report and Recommendations For Alex YachevskiSashadanceNo ratings yet

- TDS Conbextra GP2 BFLDocument4 pagesTDS Conbextra GP2 BFLsabbirNo ratings yet

- Break Even AnalysisDocument18 pagesBreak Even AnalysisSMHE100% (10)

- Alice Becker-Ho, The Language of Those in The KnowDocument4 pagesAlice Becker-Ho, The Language of Those in The KnowIntothepill Net100% (1)

- Quotation - ABS 2020-21 - E203 - Mr. K Ramesh ReddyDocument1 pageQuotation - ABS 2020-21 - E203 - Mr. K Ramesh ReddyairblisssolutionsNo ratings yet

- Presstonic Engineering Ltd.Document2 pagesPresstonic Engineering Ltd.Tanumay NaskarNo ratings yet

- Sun Pharma ProjectDocument26 pagesSun Pharma ProjectVikas Ahuja100% (1)

- Ch13. Flexible Budget-AkmDocument44 pagesCh13. Flexible Budget-AkmPANDHARE SIDDHESHNo ratings yet

- Third Party Logistics: A Literature Review and Research AgendaDocument26 pagesThird Party Logistics: A Literature Review and Research AgendaRuxandra Radus100% (1)

- Teaching PronunciationDocument6 pagesTeaching PronunciationKathryn LupsonNo ratings yet

- Negotiation ProcessDocument6 pagesNegotiation ProcessAkshay NashineNo ratings yet

- Tender Bids From March 2012 To April 2017Document62 pagesTender Bids From March 2012 To April 2017scribd_109097762No ratings yet

- Arturo Pomar by Bill Wall: Maestros (Pomar, My 50 Games With Masters) - Pomar Was Only 14 at TheDocument3 pagesArturo Pomar by Bill Wall: Maestros (Pomar, My 50 Games With Masters) - Pomar Was Only 14 at TheKartik ShroffNo ratings yet

- GN1 Overlock Machine Manual in English PDFDocument23 pagesGN1 Overlock Machine Manual in English PDFomaramedNo ratings yet