Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Impact of Globalisation On Poverty and Inequality in The Global South

The Impact of Globalisation On Poverty and Inequality in The Global South

Uploaded by

Kassyap VempalliOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Impact of Globalisation On Poverty and Inequality in The Global South

The Impact of Globalisation On Poverty and Inequality in The Global South

Uploaded by

Kassyap VempalliCopyright:

Available Formats

The Impact of Globalisation on Poverty and Inequality in the Global South

Written by Julia Heinze

This PDF is auto-generated for reference only. As such, it may contain some conversion errors and/or missing information. For all

formal use please refer to the official version on the website, as linked below.

The Impact of Globalisation on Poverty and Inequality

in the Global South

https://www.e-ir.info/2020/03/22/the-impact-of-globalisation-on-poverty-and-inequality-in-the-global-south/

JULIA HEINZE, MAR 22 2020

Globalisation according to Luke Martell is “the integration of poor countries into a world economy of open

competition” (Martell 2017, 148). Its process allows hundreds of people to live in the comfort of not having to worry

about food, money, health care or education. They are lucky enough to take such basics for granted and to be

oblivious to the gap of inequality and poverty (Bardhan 2006). The IMF’s neoliberal policy of the World Bank, the rise

of the Green Revolution, and Structural Adjustment policies created a gap with a chasm of injustice in between.

While, anti-globalists see globalisation as a producer of inequality, others view it as equalising, democratising and

expanding the horizons of the poor. The latter conviction is partly the result of a belief in the beneficial effects of free

trade. Maintaining that inequality is not the same as poverty, as inequality can rise while poverty can reduce, this

essay will explain the impact globalisation has had on inequality and poverty in the Global South. It will begin with the

counter-opinion to this essay – that globalisation has made the world a better place and reduced the gap between the

West and the “rest”, by explaining the beliefs of anti-globalists, present how neoliberal policies in the 1980s failed in

becoming effective to developing countries. Finally, it will touch on problems of inequality in the fast fashion industry

and inhumane working conditions which, despite reducing poverty, did not render these countries economically

viable.

To begin with, it is important to outline some of the terms being used in this essay. While it is very hard to define

“inequality”, as it can be examined through a multitude of factors, according to the European Commission there are

two main ideas – “inequality of outcome and inequality of opportunity” (Ec.europa.eu. n.d.). However, in this essay I

will focus mostly on the former, the ‘inequality of outcome’, defining it as “how the income earned in an economy is

distributed across the population” (Ec.europa.eu. n.d.). This is extended by the European Commission’s definition of

poverty from 1984 – “the poor shall be taken to mean persons, families and groups of persons whose resources

(material, cultural and social) are so limited as to exclude them from the minimum acceptable way of life in the

member state in which they live” (Spicker et al. 2007, 71). There are two waves of globalisation. The first dates from

the beginning of the nineteenth century to the First World War and the second established in the second half of the

twentieth century (O’Rourke 2001). Economists usually stand by the belief that globalisation made the world more

integrated, as local economies become no longer just individual. The improvement of development that happened

over the past 200 years has been very supportive for developing countries. As Martin Wolf argues in “Financial

Times” – global economic integration made both poverty and inequality fall over the past two decades for the first

time in 150 years, “a decline of people in the absolute poverty, fall from 31% of the world’s population to 20%” (Held

and McGrew 2016, 441). This is further extended, as “between 1981 and 2001 the percentage of rural people living

on less than 1 a day decreased from 79 to 27 per cent in China, 63 to 42 per cent in India, and 55 to 11 per cent in

Indonesia” (Bardhan 2006). Providing such data, one could conclude that globalisation has strongly contributed to

the improvement of the economic and living situation in developing countries.

Nonetheless, it’s worth pointing out that China and India include over a third of the world’s population and are an

example of the fastest developing countries. Through their rapid growth they succeeded in fighting poverty and

reducing undernourishment, meanwhile in looking at sub-Saharan Africa there is still 23% of people living

undernourished (Held and McGrew 2016). Following this, if we take China out, the global economic situation has

worsened in other parts of the developing world. For example, the poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa has risen from 290

E-International Relations ISSN 2053-8626 Page 1/4

The Impact of Globalisation on Poverty and Inequality in the Global South

Written by Julia Heinze

million to 415 million and “at the end of the nineteenth century, the ratio of average income in the richest countries to

middle income in the poorest was 9 to 1” (Martell 2017, 138). What’s more, the middle-income family today in the

United States is 60 times richer than the average family in Ethiopia or Bangladesh” (Birdsall 2003).

In contrast to supporters of globalisation, anti-globalists believe the result of globalisation is negative, and the

inequalities in the world instead of decreasing, are increasing. A “movement of movements” emerged in the late

1990s in opposition to neoliberalism, in the form of organisations like WTO. Movements like “Battle of Seattle”,

aimed to repeal laws and lack of democratic accountability, protect public health, stop the negative impact of

globalisation and try to bring the power back to the people again. When showing the negative effect of globalisation it

is important to mention that today’s “rich countries” were already rich many years ago (thanks to the industrial

revolution). In turn, poor countries, (which were poor from the beginning) did not gain much from it. For anti-

globalists, the IMF’s neoliberal policies had led to greater indebtedness and even greater inequality. They believe

that the neoliberal global economy would only effective and beneficial if everyone was equal (Martell 2017).

Firstly, the Green Revolution occurring between 1950 and the late 1960s invoked a boom in agricultural production

and pushed a demand for more in developing countries. This meant something different for poor Africans than that

for rich corporations. It indeed increased the production, but at the same time it rejected small farmers who could not

afford the High-tech inputs and went bankrupt or disappeared (George 2013). To best show the negative effects of

the Green Revolution, it is worth mentioning how it affected Pakistan and Ethiopia. According to Niazi (2004), the

Green Revolution did not end the existing hunger, poverty and unemployment, but instead increased them and

contributed to social inequalities through unequal access to production resources (Birdsall 2003). It also led to

inequalities in distribution. There are opinions that the Green Revolution played a major role in reducing poverty in

Asia through the emergence of international partnerships, which helped to develop products suitable for the poor,

such as drugs, vaccines etc. (Bardhan 2006). In Ethiopia, on the other hand, although the Green Revolution led to an

increase in food production, it contributed to huge social tensions (Birdsall 2003). Again, because the effects of the

Green Revolution were mostly harmful for the Global South, it supports the previous argument that the global

situation, discounting China and India, is worsened in other parts of the developing world (Martell 2017).

Secondly, in the 1980s and 1990s, developing countries opened and liberalised their markets by creating reforms,

reducing tariff barriers, privatising their economies, and, after time, opening up capital markets. This opportunity to

put neoliberal policies into practice within developing countries had a huge impact on them and led to sudden

increase in interest rates. The way in which poorer countries have become included in world trade was created

through the Washington Consensus, implemented with the help of organisations such as the World Bank and the

IMF. This led to the Debt Crisis of the 1980s which played another significant role when it comes to poverty in the

Global South (Martell 2017). The IMF’s structural adjustments, loans under special conditions, aimed to help fight the

debt crisis and restructure their economies. Along these lines, Washington Consensus policies promoted

liberalisation of trade, the elimination of barriers to foreign trade, and the achievement of stable and balanced

economic development, to finally fight against the Debt Crisis, thanks to the influence of neoliberal policies and

financial institutions. This created a situation where organisations and rich countries provided financial support to

poor countries in order to stimulate development (Martell 2017).

The Structural Adjustment Policies, in fact, led to poor, negative growth, a dramatic increase in external debt,

decrease of exports and, in the end, doubled poverty. Summing up the Washington Consensus, its numerous

problematic reforms that were implemented in Latin America and other countries of The Global South did not

produce the expected effect. According to Joseph Stiglitz, globalisation and more specifically the Washington

Consensus lacked in attention to governance and did not adequately consider the impact of economic policies on the

state and its role, thus failing to address both poverty and inequality (Stiglitz 2017). What is more, the companies of

rich countries in fact benefited from it because of the easing of tariffs (Martell 2017). Evidently, there is a need for

more active and integrated policies than the one provided by the SAP to allow developing countries to benefit from

globalisation (Kaplinsky 2013).

Again, globalists believe that people in developing countries are more productive thanks to the industrial growth,

which still increases through globalisation. They allow that fast-fashion company owners becoming millionaires, while

E-International Relations ISSN 2053-8626 Page 2/4

The Impact of Globalisation on Poverty and Inequality in the Global South

Written by Julia Heinze

the women working in the factories earn 3 dollars per 10 hours every day, without any rights, displays inequality. But

globalists argue that because the workers’ standard of living is much higher than if they were without that job, it is

actually beneficial for them (Bardhan 2006). An Oxfam report in 2002 quoted, a 23-year-old mother working in the

factory in Bangladesh: “This job is hard–and we are not treated fairly(…) But back in my village, I would have less

money. Outside of the factories, people selling things in the street or carrying bricks on building sites earn less than

we do” (Bardhan 2006) In addition, The University of Sussex in England and the Bangladesh Institute of

Development Studies claims that “the average monthly income of workers in garment-export factories was 86

percent above that of other wage workers living in the same slum neighborhoods” (Bardhan 2006). Therefore, this

creates a paradox. Although it might reduce poverty, it does increase inequality.

The women working in fast-fashion live on low wages, under unsafe conditions and harassment. Not only do they

receive less pay than male employees, but they also are not allowed to ask for more rights or better working

conditions (Kaur 2016). Even though the report from Oxfam shows that without the job in the sweatshop factories

they would not be able to have food and basic needs, and they would earn much less, the “War on Want” report

published in July 2011 shows that “wages of the sweatshops workers were not enough to allow them to provide their

family with basic human necessities”( Kaur 2016). Therefore, sweatshops today are not only the cause of inequality,

but also poverty, as the “War on Want” report on the living conditions of these sweatshop workers aligns with the

definition of poverty illustrated previously by the European Commission in 1984. Globalisation and the fast-fashion

industry has created a situation where these women are under huge pressure to feed their children and lack the

rights of registered workers, often under sexual harassment, low wages and hazardous working conditions, while the

owners of these fashion brands are becoming millionaires and continue to benefit from it (Kaur 2016).

To conclude, while some countries benefit from globalisation, others are left behind with increasing inequality. As

Hans Rosling once said, globalisation is often accused of the creation of “the West and the rest” (Rosling et al.

2018). On the whole, The Washington Consensus, SAP, the World Bank and the IMF’s strive towards global liberal

integration and liberal trade did not create an effective solution for the Global South to get out of poverty and

inequality. My essay has introduced that globalisation and free trade “would be a good thing if all actors were equal

participants” (Martell 2017, 138). Neoliberalism has created a situation where while the poor benefits, the rich still get

richer and it does not make the gap any smaller. If we look more broadly, while China and India are reducing levels of

poverty, other developing countries are still left behind and are not positioned as an equal participant in the whole

process of global economic integration. Therefore, the opinion of Joseph Stiglitz about the Global South being mostly

worse off from globalisation seems to be accurate. Globalisation failed in analyzing its impact on poverty and

inequality in developing countries. Globalisation as a concept is not itself the problem, but the way it is being

managed and put into practice is hugely problematic (Stiglitz 2017).

Bibliography

Bardhan, P. (2006). Does Globalization Help or Hurt the World’s Poor?: Overview/Globalization and Poverty .

[online] Scientific American. Available at: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/does-globalization-help-

o-2006-04/.

Birdsall, N. (2003). Asymmetric Globalization: Global Markets Require Good Global Politics . [online] Brookings.

Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/asymmetric-globalization-global-markets-require-good-global-

politics/.

Ec.europa.eu. (n.d.). [online] Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/file_import/european-

semester_thematic-factsheet_addressing-inequalities_en_0.pdf [Accessed 18 Feb. 2019].

George, S. (2013). Whose Crisis, Whose Future?. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Held, D. and McGrew, A. (2016). The global transformations reader. Cambridge: Polity Press, pp. 440-480.

E-International Relations ISSN 2053-8626 Page 3/4

The Impact of Globalisation on Poverty and Inequality in the Global South

Written by Julia Heinze

Kaplinsky, R. (2013). Globalization, Poverty and Inequality. Oxford: Wiley.

Kaur, H. (2016). Low wages, unsafe conditions and harassment: fashion must do more to protect female workers .

[online] the Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2016/mar/08/fashion-industry-

protect-women-unsafe-low-wages-harassment.

Martell, L. (2017). The sociology of globalization. 2nd ed. Cambridge, UK, p. 138.

Martell, L. (2017). The sociology of globalization. 2nd ed.

Niazi, T. (2004). Rural Poverty and the Green Revolution: The Lessons from Pakistan. Journal of Peasant Studies,

31(2), pp. 242-260.

O’Rourke, K. (2001). Globalization and Inequality. Cambridge, Mass: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Rosling, H., Rosling, O. and Rosling Rönnlund, A. (2018). Factfulness. London: Sceptre.

Spicker, P., Álvarez Leguizamón, S. and Gordon, D. (2007). Poverty. London, England: Zed Books, pp.71-72.

Stiglitz, J. (2017). Globalization and its discontents.

Written by: Julia Heinze

Written at: De Montfort University

Written for: Zoe Pflaeger Young

Date written: April 2019

E-International Relations ISSN 2053-8626 Page 4/4

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

You might also like

- Mi Uia 6347Document1 pageMi Uia 6347Alton Marshall Sr.42% (36)

- Module - The Contemporary WorldDocument54 pagesModule - The Contemporary WorldPhilip Lara100% (11)

- Read: Florida Unemployment Lawsuit FiledDocument15 pagesRead: Florida Unemployment Lawsuit FiledChris Vaughn100% (2)

- Black Swans - Discrete Events-Would Cause Large-Scale Disruption. All But Two ofDocument8 pagesBlack Swans - Discrete Events-Would Cause Large-Scale Disruption. All But Two ofClven Joszette FernandezNo ratings yet

- EARNINGS REWARDS AND BENEFITS 1 ExerciceDocument1 pageEARNINGS REWARDS AND BENEFITS 1 ExerciceOukil RaouaneNo ratings yet

- Engleza 2Document5 pagesEngleza 2Diana DumitruNo ratings yet

- Globalization and PovertyDocument7 pagesGlobalization and PovertyEricNzukiNo ratings yet

- Economic Globalization Impacts Developing CountriesDocument14 pagesEconomic Globalization Impacts Developing CountriesThavann ThaiNo ratings yet

- The Debate On The Relationship Between Globalization, Poverty and InequalityDocument6 pagesThe Debate On The Relationship Between Globalization, Poverty and InequalityRURI TIYASNo ratings yet

- Globalisation - Good or Bad? RodrigoDocument11 pagesGlobalisation - Good or Bad? RodrigoMycz DoñaNo ratings yet

- Making Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureDocument43 pagesMaking Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureOxfamNo ratings yet

- Making Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureDocument43 pagesMaking Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureOxfamNo ratings yet

- Making Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureDocument43 pagesMaking Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureOxfamNo ratings yet

- Making Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureDocument43 pagesMaking Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureOxfamNo ratings yet

- Making Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureDocument43 pagesMaking Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureOxfamNo ratings yet

- Making Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureDocument43 pagesMaking Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureOxfamNo ratings yet

- Making Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureDocument43 pagesMaking Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureOxfamNo ratings yet

- Making Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureDocument43 pagesMaking Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureOxfamNo ratings yet

- Making Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureDocument43 pagesMaking Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureOxfamNo ratings yet

- Making Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureDocument43 pagesMaking Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureOxfamNo ratings yet

- Making Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureDocument43 pagesMaking Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureOxfamNo ratings yet

- Making Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureDocument43 pagesMaking Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureOxfamNo ratings yet

- Making Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureDocument43 pagesMaking Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureOxfamNo ratings yet

- Making Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureDocument43 pagesMaking Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureOxfamNo ratings yet

- Making Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureDocument43 pagesMaking Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureOxfamNo ratings yet

- Making Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureDocument43 pagesMaking Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureOxfamNo ratings yet

- Making Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureDocument43 pagesMaking Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureOxfamNo ratings yet

- The Global EconomyDocument33 pagesThe Global EconomyKwenzie FortalezaNo ratings yet

- Globalisation Boon or BaneDocument3 pagesGlobalisation Boon or Banejhugaroo_raksha01100% (1)

- Inequality BookDocument41 pagesInequality Bookgiuseppedipalo174No ratings yet

- Pcaaa 960Document5 pagesPcaaa 960Genesis AdcapanNo ratings yet

- Globalisation and Its Impact On Poverty and Inequality Case Study of Lower Middle Income CountriesDocument11 pagesGlobalisation and Its Impact On Poverty and Inequality Case Study of Lower Middle Income CountriesEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- UNFPA's View On Population: An Economic Analysis: Alejandro CidDocument15 pagesUNFPA's View On Population: An Economic Analysis: Alejandro CidMurie Amai LisaNo ratings yet

- CWORLD2Document1 pageCWORLD2taehyung trashNo ratings yet

- Globalization and The Nation-State: Sovereignty and State Welfare in JeopardyDocument8 pagesGlobalization and The Nation-State: Sovereignty and State Welfare in JeopardyDeine P. FloresNo ratings yet

- Gupta 2012 - The Construction of The Global PoorDocument4 pagesGupta 2012 - The Construction of The Global PoorLauraEscudeiroNo ratings yet

- Approch To Development and PovertyDocument5 pagesApproch To Development and PovertyJoakim JakobsenNo ratings yet

- Sedigheh Babran - Media, Globalization of Culture, and Identity Crisis in Developing CountriesDocument10 pagesSedigheh Babran - Media, Globalization of Culture, and Identity Crisis in Developing CountriesCristina GanymedeNo ratings yet

- WPS OfficeDocument6 pagesWPS OfficecalindayNo ratings yet

- Rural Development: February 2009Document13 pagesRural Development: February 2009Hilton JingurahNo ratings yet

- Economic GlobalizationDocument41 pagesEconomic GlobalizationMarjorie O. MalinaoNo ratings yet

- Fariha Khan Roll 18 PDFDocument8 pagesFariha Khan Roll 18 PDFFarihaNo ratings yet

- Economic Globalization and PovertyDocument2 pagesEconomic Globalization and PovertyMa. Lourdes SorongonNo ratings yet

- Contemporary World1Document39 pagesContemporary World1Chester Angelo AbilgosNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0955395906002556 Main PDFDocument12 pages1 s2.0 S0955395906002556 Main PDFNur SyafiqahNo ratings yet

- Concept PaperDocument4 pagesConcept PaperMeli SsaNo ratings yet

- PovertyDocument10 pagesPovertyJohnNo ratings yet

- Neoliberalism and PovertyDocument10 pagesNeoliberalism and PovertySabrina SachsNo ratings yet

- Lecture Global Inequality and Global PovertyDocument11 pagesLecture Global Inequality and Global PovertyYula YulaNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Globalization On Income Distribution in Emerging EconomiesDocument25 pagesThe Impact of Globalization On Income Distribution in Emerging EconomiesGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Introduction and History of Globalization: Charles Taze RussellDocument4 pagesIntroduction and History of Globalization: Charles Taze RussellGhulamKibriaNo ratings yet

- 1717775Document13 pages1717775Inri Asridisastra DNo ratings yet

- Global Economy Midterm GroupDocument17 pagesGlobal Economy Midterm GroupshariffabdukarimNo ratings yet

- Poverty GlobalizationDocument14 pagesPoverty Globalizationsiscani3330No ratings yet

- SW 122 Book ReportDocument12 pagesSW 122 Book ReportCarmelaNo ratings yet

- Neoliberalism FinalDocument17 pagesNeoliberalism Finalbaikuntha pandeyNo ratings yet

- Globalisation & InequalityDocument14 pagesGlobalisation & InequalityVan ToNo ratings yet

- Globalization and Its New DiscontentsDocument3 pagesGlobalization and Its New DiscontentsIzzy SalazarNo ratings yet

- United Nations Development Programme: Leading the way to developmentFrom EverandUnited Nations Development Programme: Leading the way to developmentNo ratings yet

- Summary Of "Globalization, An Approach To Discussion" By M. Pautasso & M.L. Diez: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESFrom EverandSummary Of "Globalization, An Approach To Discussion" By M. Pautasso & M.L. Diez: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESNo ratings yet

- Good Food Manufacturing Practices: See Discussions, Stats, and Author Profiles For This Publication atDocument21 pagesGood Food Manufacturing Practices: See Discussions, Stats, and Author Profiles For This Publication atKassyap VempalliNo ratings yet

- 19abpm81 ShobanaaKDocument9 pages19abpm81 ShobanaaKKassyap VempalliNo ratings yet

- Abstract - Irradiation Is The Process of Exposing Fresh Foods To LowDocument22 pagesAbstract - Irradiation Is The Process of Exposing Fresh Foods To LowKassyap VempalliNo ratings yet

- Pps Coffee 2009 1 PDFDocument12 pagesPps Coffee 2009 1 PDFKassyap VempalliNo ratings yet

- 19PGDM48 RmdaDocument23 pages19PGDM48 RmdaKassyap VempalliNo ratings yet

- Course: - Production and Operations Management For Plantation & Agri Commodity (POM - PAC)Document8 pagesCourse: - Production and Operations Management For Plantation & Agri Commodity (POM - PAC)Kassyap VempalliNo ratings yet

- Globalization & Sustainable Development Strategies For Poverty Eradication & Wealth CreationDocument51 pagesGlobalization & Sustainable Development Strategies For Poverty Eradication & Wealth CreationKassyap VempalliNo ratings yet

- K.v.l.deepak 19pgdmabpm13 PDFDocument14 pagesK.v.l.deepak 19pgdmabpm13 PDFKassyap VempalliNo ratings yet

- Creating Opportunities For Rural YouthDocument44 pagesCreating Opportunities For Rural YouthKassyap VempalliNo ratings yet

- Gratitude Farms Introduction - Mar 2020 PDFDocument10 pagesGratitude Farms Introduction - Mar 2020 PDFKassyap VempalliNo ratings yet

- Rural MarketingDocument9 pagesRural MarketingKassyap VempalliNo ratings yet

- New Thinking On Poverty: Implications For Poverty Reduction StrategiesDocument47 pagesNew Thinking On Poverty: Implications For Poverty Reduction StrategiesKassyap VempalliNo ratings yet

- Globalization and Poverty Reduction - DISD PDFDocument3 pagesGlobalization and Poverty Reduction - DISD PDFKassyap VempalliNo ratings yet

- Clare Tresidder: Senior Brand Manager Cow & Gate Consumer ConnectionsDocument20 pagesClare Tresidder: Senior Brand Manager Cow & Gate Consumer ConnectionsKassyap VempalliNo ratings yet

- Kannan Devan PDFDocument56 pagesKannan Devan PDFKassyap Vempalli100% (3)

- Consumer Perception Towards Tea and Coff PDFDocument23 pagesConsumer Perception Towards Tea and Coff PDFKassyap VempalliNo ratings yet

- Barletts TestDocument5 pagesBarletts TestKassyap VempalliNo ratings yet

- 751 Writ of Garnishment Faor Michelle To Figueras - Ls 12.13.2021Document5 pages751 Writ of Garnishment Faor Michelle To Figueras - Ls 12.13.2021larry-612445No ratings yet

- 2017 Amendment in Maternity ActDocument7 pages2017 Amendment in Maternity ActBhola PrasadNo ratings yet

- Mains 365 Eco Part 2Document3 pagesMains 365 Eco Part 2Ankit VermaNo ratings yet

- PDF de Poche Vocabulaire Anglais AssurancesDocument6 pagesPDF de Poche Vocabulaire Anglais AssurancesMatcheha aimé HervéNo ratings yet

- Idioms and Fixed PhrasesDocument5 pagesIdioms and Fixed PhrasesAnna SobolevaNo ratings yet

- Rural Development Programs of IndiaDocument4 pagesRural Development Programs of IndiaAbhay PratapNo ratings yet

- Unit 03Document9 pagesUnit 03bobo tangaNo ratings yet

- Texas Workforce InstructionsDocument2 pagesTexas Workforce InstructionsamirNo ratings yet

- Job AnalysisDocument5 pagesJob AnalysisHamad RazaNo ratings yet

- Case Study UnileverDocument9 pagesCase Study UnileverCasper John Nanas MuñozNo ratings yet

- Employment Flexibility at Pushkar Hotels: Learning Through Alternative PedagogiesDocument8 pagesEmployment Flexibility at Pushkar Hotels: Learning Through Alternative Pedagogiestanishqa joganiNo ratings yet

- 2023 PCL Chapter 3 CPP Ei RequirementsDocument59 pages2023 PCL Chapter 3 CPP Ei RequirementsSkyNo ratings yet

- Essay Plans 1: Across The Economy and Thus Stimulate Lending, Borrowing, AD and Economic GrowthDocument24 pagesEssay Plans 1: Across The Economy and Thus Stimulate Lending, Borrowing, AD and Economic GrowthAbhishek JainNo ratings yet

- Employee Satisfaction On Welfare Measures at Balco PVT LTDDocument11 pagesEmployee Satisfaction On Welfare Measures at Balco PVT LTDAngel BeautyNo ratings yet

- Chapter Four: The Rewarding of HRDocument25 pagesChapter Four: The Rewarding of HRethnan lNo ratings yet

- Employment ContractDocument2 pagesEmployment ContractInna MrachkovskaNo ratings yet

- Human Resource Management CasesDocument9 pagesHuman Resource Management CasesGio AlvarioNo ratings yet

- Labour in Developing CountriesDocument45 pagesLabour in Developing Countriesmailk jklmnNo ratings yet

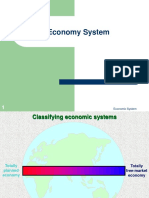

- ECO162 Notes Chap 1 Economy SystemDocument30 pagesECO162 Notes Chap 1 Economy SystemAaaAAAa aaANo ratings yet

- CH 4. Poverty Inequality and DevelopmentDocument45 pagesCH 4. Poverty Inequality and DevelopmentEddyzsa ReyesNo ratings yet

- Householder Employer's GuideDocument18 pagesHouseholder Employer's GuideA PNo ratings yet

- Argumentative Final EssayDocument6 pagesArgumentative Final Essayapi-704336458No ratings yet

- Gcse Economics: Paper 2 How The Economy WorksDocument20 pagesGcse Economics: Paper 2 How The Economy WorkskaruneshnNo ratings yet

- General Direction: Write All Your Answers in Separate Sheet of PaperDocument1 pageGeneral Direction: Write All Your Answers in Separate Sheet of PaperRoey MijaresNo ratings yet

- Macro Economic PoliciesDocument2 pagesMacro Economic PoliciesThomasMercerNo ratings yet

- Income Taxation of Employees in The PhilippinesDocument4 pagesIncome Taxation of Employees in The Philippinesjoan villacastinNo ratings yet

- Credit Union Research PaperDocument6 pagesCredit Union Research Paperz0pilazes0m3100% (1)