Professional Documents

Culture Documents

SOJ V Lantion

SOJ V Lantion

Uploaded by

Athina Maricar CabaseCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Spouses Avelina Rivera-Nolasco and Eduardo A. Nolasco, vs. Rural Bank of Pandi, Inc.Document3 pagesSpouses Avelina Rivera-Nolasco and Eduardo A. Nolasco, vs. Rural Bank of Pandi, Inc.Athina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

- United States v. Travis Robinson, 4th Cir. (2012)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Travis Robinson, 4th Cir. (2012)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Handbook-International Arbitration 3rd Ed P. CapperDocument102 pagesHandbook-International Arbitration 3rd Ed P. Cappercchesser100% (6)

- Annotation On Locus Standi 314 Scra 641Document6 pagesAnnotation On Locus Standi 314 Scra 641Johanna Mae L. AutidaNo ratings yet

- Case Digest - OBUS, MYRNA A.Document42 pagesCase Digest - OBUS, MYRNA A.Myrna Angay Obus100% (1)

- People V ElkanishDocument7 pagesPeople V ElkanishDuffy DuffyNo ratings yet

- Erlinda Sistual v. Atty. Eliordo Ogena, Ac. No. 9807, Feb 02, 2016Document2 pagesErlinda Sistual v. Atty. Eliordo Ogena, Ac. No. 9807, Feb 02, 2016Karen Joy MasapolNo ratings yet

- 28 - Lim v. Pacquing, 240 SCRA 649 - EspinosaDocument8 pages28 - Lim v. Pacquing, 240 SCRA 649 - EspinosaRudiverjungcoNo ratings yet

- Bar 2015 QuestionsDocument27 pagesBar 2015 QuestionsBrent DagbayNo ratings yet

- Abueva vs. Wood, 45 Phil 612Document13 pagesAbueva vs. Wood, 45 Phil 612fjl_302711No ratings yet

- 21-Cruz Vs IturraldeDocument6 pages21-Cruz Vs IturraldeLexter CruzNo ratings yet

- Wack Wack Golf vs. WonDocument4 pagesWack Wack Golf vs. WonWendy PeñafielNo ratings yet

- Salonga Vs Paño, GR No. L-59524Document13 pagesSalonga Vs Paño, GR No. L-59524Ashley Kate PatalinjugNo ratings yet

- Bayan vs. Executive SecretaryDocument49 pagesBayan vs. Executive SecretaryJerry SerapionNo ratings yet

- David Vs Gma Immunitability Vs ImpeachabilityDocument2 pagesDavid Vs Gma Immunitability Vs Impeachabilityanon_360675804No ratings yet

- LegProf - Soliman Santos, Jr. Vs Atty. Francisco Llamas AC 4749, (Jan. 20, 2000)Document1 pageLegProf - Soliman Santos, Jr. Vs Atty. Francisco Llamas AC 4749, (Jan. 20, 2000)Lu CasNo ratings yet

- Maneuvering Reconveyance of Client's Property To Self, EtcDocument5 pagesManeuvering Reconveyance of Client's Property To Self, EtcTricia Low SanchezNo ratings yet

- Estarija v. RanadaDocument14 pagesEstarija v. RanadaJ. JimenezNo ratings yet

- Full Text - Ynot Vs Iac 148 Scra 659Document2 pagesFull Text - Ynot Vs Iac 148 Scra 659arctikmarkNo ratings yet

- Sample Complaint For Collection For A Sum 1Document3 pagesSample Complaint For Collection For A Sum 1ALEXNo ratings yet

- Garcia vs. Board of Investments (G.R. No. 92024, November 9, 1990)Document8 pagesGarcia vs. Board of Investments (G.R. No. 92024, November 9, 1990)Carlota Nicolas VillaromanNo ratings yet

- Revised Penal C OdeDocument3 pagesRevised Penal C OdeDah Rin CavanNo ratings yet

- Hustler Magazine, Inc. v. Falwell, 485 U.S. 46 (1988)Document10 pagesHustler Magazine, Inc. v. Falwell, 485 U.S. 46 (1988)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. L-17115 Guevara Vs Gimenez (Functions and Duties of COA)Document3 pagesG.R. No. L-17115 Guevara Vs Gimenez (Functions and Duties of COA)MarkNo ratings yet

- Lim v. PacquingDocument46 pagesLim v. PacquingJD grey100% (1)

- Tax Rev Midterms CoverageDocument11 pagesTax Rev Midterms CoverageRegi Mabilangan ArceoNo ratings yet

- Quimsing v. TajanlangitDocument2 pagesQuimsing v. TajanlangitSteven OrtizNo ratings yet

- C3f - 3 - People v. SabayocDocument4 pagesC3f - 3 - People v. SabayocAaron AristonNo ratings yet

- Freeman vs. ReyesDocument7 pagesFreeman vs. ReyesBiboy GSNo ratings yet

- City Government of Baguio V MaswengDocument2 pagesCity Government of Baguio V MaswengLax ConcepcionNo ratings yet

- Ciocon-Reer v. LubaoDocument6 pagesCiocon-Reer v. LubaoKirk BejasaNo ratings yet

- Endencia V DavidDocument2 pagesEndencia V DavidMarius RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Bengzon vs. Senate Blue Ribbon Committee (203 SCRA 767)Document31 pagesBengzon vs. Senate Blue Ribbon Committee (203 SCRA 767)Mak FranciscoNo ratings yet

- Case Digests in Special Penal LawsDocument39 pagesCase Digests in Special Penal LawsLovelle Belaca-olNo ratings yet

- Tetangco Vs OmbudsmanDocument5 pagesTetangco Vs OmbudsmanRon AceNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 14129, July 31, 1962 People Vs ManantanDocument5 pagesG.R. No. 14129, July 31, 1962 People Vs ManantanJemard FelipeNo ratings yet

- Peña v. Court of Appeals, 193 SCRA 717 (1991)Document27 pagesPeña v. Court of Appeals, 193 SCRA 717 (1991)inno KalNo ratings yet

- Belgica vs. Ochoa DigestDocument16 pagesBelgica vs. Ochoa DigestRonnieEnggingNo ratings yet

- Doctrine: UCCP and BUCCI, Being Corporate Entities and Grantees of Primary Franchises, AreDocument2 pagesDoctrine: UCCP and BUCCI, Being Corporate Entities and Grantees of Primary Franchises, AreShandrei GuevarraNo ratings yet

- David Vs ArroyoDocument5 pagesDavid Vs ArroyoPortia WynonaNo ratings yet

- The Honorable Office of The Ombudsman v. Leovigildo Delos Reyes, JRDocument12 pagesThe Honorable Office of The Ombudsman v. Leovigildo Delos Reyes, JRRAINBOW AVALANCHENo ratings yet

- People v. Dionisio Vicente y QuintoDocument12 pagesPeople v. Dionisio Vicente y QuintoKuzan AokijiNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 138965 - Public Interest Center Inc. v. ElmaDocument3 pagesG.R. No. 138965 - Public Interest Center Inc. v. ElmaMA. TERIZ S CASTRONo ratings yet

- Valdez v. PeopleDocument27 pagesValdez v. Peoplekyla_0111No ratings yet

- Rod of Pampangga Vs PNBDocument2 pagesRod of Pampangga Vs PNBedmarkbaroyNo ratings yet

- Tatad v. Sec. of Doe - 281 Scra 330 (1997)Document16 pagesTatad v. Sec. of Doe - 281 Scra 330 (1997)Gol Lum100% (1)

- 62 Court Administrator v. QuinanolaDocument1 page62 Court Administrator v. QuinanolaNMNGNo ratings yet

- Olaquer vs. MC No. 4, 150 SCRA 144 (1987)Document36 pagesOlaquer vs. MC No. 4, 150 SCRA 144 (1987)Reginald Dwight FloridoNo ratings yet

- Current Status of Adoption in The PhilippinesDocument3 pagesCurrent Status of Adoption in The PhilippinesEugene Albert Olarte JavillonarNo ratings yet

- Marceliano L. Castellano For PetitionerDocument19 pagesMarceliano L. Castellano For PetitionerLien PatrickNo ratings yet

- Bacani Vs NacocoDocument1 pageBacani Vs NacocoHenteLAWcoNo ratings yet

- Nunga, Jr. v. Nunga 111, 574 SCRA 760 PDFDocument10 pagesNunga, Jr. v. Nunga 111, 574 SCRA 760 PDFenarguendo100% (1)

- Public Officers' Right To Retirement PayDocument5 pagesPublic Officers' Right To Retirement PayMiguel AlagNo ratings yet

- Francisco vs. House of Representatives Case DigestDocument4 pagesFrancisco vs. House of Representatives Case DigestEmma Ruby Aguilar-ApradoNo ratings yet

- GR No. L-13250 Oct. 29, 1971 COLLECTOR OF INTERNAL REVENUE v. ANTONIO CAMPOS RUEDADocument7 pagesGR No. L-13250 Oct. 29, 1971 COLLECTOR OF INTERNAL REVENUE v. ANTONIO CAMPOS RUEDAJuris AbiderNo ratings yet

- Candelaria - International Legal Concepts of Peace AgreementsDocument34 pagesCandelaria - International Legal Concepts of Peace AgreementsJoe PanlilioNo ratings yet

- Del Mar vs. Pva, 51 Scra 340Document5 pagesDel Mar vs. Pva, 51 Scra 340Atty Ed Gibson BelarminoNo ratings yet

- Dingcong vs. Guingona PDFDocument8 pagesDingcong vs. Guingona PDFAlthea Angela GarciaNo ratings yet

- ABAKADA GURO PARTY LIST OFFICERS SAMSON S. ALCANTARA v. EXECUTIVE SECRETARY EDUARDO ERMITADocument8 pagesABAKADA GURO PARTY LIST OFFICERS SAMSON S. ALCANTARA v. EXECUTIVE SECRETARY EDUARDO ERMITAMae TrabajoNo ratings yet

- Tilted Justice: First Came the Flood, Then Came the Lawyers.From EverandTilted Justice: First Came the Flood, Then Came the Lawyers.Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- MEDIA LAW 2. Department of Justice v. LantonDocument3 pagesMEDIA LAW 2. Department of Justice v. LantonKarl Angelo TulioNo ratings yet

- A. Relativity of Due ProcessDocument13 pagesA. Relativity of Due ProcessErika PotianNo ratings yet

- Secretary of Justice vs. LantionDocument23 pagesSecretary of Justice vs. LantionPamela Jane I. TornoNo ratings yet

- Virgines Calvo Doing Business Under The Name and Style Transorient Container Terminal Services, Inc Vs UCPB General Insurance Co.Document5 pagesVirgines Calvo Doing Business Under The Name and Style Transorient Container Terminal Services, Inc Vs UCPB General Insurance Co.Athina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

- Compania Maritima v. CADocument4 pagesCompania Maritima v. CAAthina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

- Reodica v. CADocument2 pagesReodica v. CAAthina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

- De Guzman v. CA, G.R. No. L-47822 (1988)Document4 pagesDe Guzman v. CA, G.R. No. L-47822 (1988)Athina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

- Torres-Madrid Brokerage v. Feb Mitsui Marine InsuranceDocument7 pagesTorres-Madrid Brokerage v. Feb Mitsui Marine InsuranceAthina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

- Theory of Error (Prelim)Document5 pagesTheory of Error (Prelim)Athina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

- Loadstar Shipping v. Malayan InsuranceDocument2 pagesLoadstar Shipping v. Malayan InsuranceAthina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

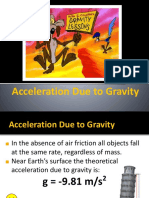

- 1.6 - Acceleration Due To GravityDocument5 pages1.6 - Acceleration Due To GravityAthina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

- Saludo v. CA, G.R. No. 95536Document5 pagesSaludo v. CA, G.R. No. 95536Athina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

- Ernesto L. Natividad, Petitioner, vs. Fernando Mariano, Andres Mariano and Doroteo Garcia, RespondentsDocument2 pagesErnesto L. Natividad, Petitioner, vs. Fernando Mariano, Andres Mariano and Doroteo Garcia, RespondentsAthina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

- Davao New Town Development CorporationDocument3 pagesDavao New Town Development CorporationAthina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

- Dionisia L. Reyes, Petitioner, vs. Ricardo L. Reyes, Lazaro L. Reyes, Narciso L. Reyes and Marcelo L. Reyes, Respondents.Document3 pagesDionisia L. Reyes, Petitioner, vs. Ricardo L. Reyes, Lazaro L. Reyes, Narciso L. Reyes and Marcelo L. Reyes, Respondents.Athina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

- Eufrocina Nieves, As Represented by Her Attorney-In-fact, Lazaro Villarosa, JR., Petitioner, vs. Ernesto Duldulao and Felipe Pajarillo, RespondentsDocument2 pagesEufrocina Nieves, As Represented by Her Attorney-In-fact, Lazaro Villarosa, JR., Petitioner, vs. Ernesto Duldulao and Felipe Pajarillo, RespondentsAthina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

- Victoria P. Cabral, Petitioner, vs. Heirs of Florencio Adolfo and Heirs of Elias Policarpio, RespondentsDocument4 pagesVictoria P. Cabral, Petitioner, vs. Heirs of Florencio Adolfo and Heirs of Elias Policarpio, RespondentsAthina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

- Otilia Sta. Ana, Petitioner, vs. Spouses Leon G. CarpoDocument3 pagesOtilia Sta. Ana, Petitioner, vs. Spouses Leon G. CarpoAthina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

- Casent Realty Dev't Corp v. Philbanking Corporation (2007)Document2 pagesCasent Realty Dev't Corp v. Philbanking Corporation (2007)Athina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

- Pre-Trial Brief Peter Cruz - PlaintiffDocument5 pagesPre-Trial Brief Peter Cruz - PlaintiffbananayellowsharpieNo ratings yet

- 35th BCI Moot Court Competition 2019 Respondent Memorial Problem 1 PDFDocument14 pages35th BCI Moot Court Competition 2019 Respondent Memorial Problem 1 PDFDebashish PandaNo ratings yet

- People V ReyesDocument3 pagesPeople V ReyesRoselyn PascobelloNo ratings yet

- Department OF Budget AND Management Department OF Interior AND Local GovernmentDocument2 pagesDepartment OF Budget AND Management Department OF Interior AND Local GovernmentdonyacarlottaNo ratings yet

- Freeborn County AnswerDocument4 pagesFreeborn County AnswerMark WassonNo ratings yet

- Sample Case-People vs. Anson (G.R. No. 175940)Document13 pagesSample Case-People vs. Anson (G.R. No. 175940)Aaron BeasleyNo ratings yet

- Agrarian Law (CASE DIGEST) Fatima C. Dela PenaDocument17 pagesAgrarian Law (CASE DIGEST) Fatima C. Dela PenaFatima Dela PeñaNo ratings yet

- Republic vs. Luzon Stevedoring CorporationDocument4 pagesRepublic vs. Luzon Stevedoring Corporationcassandra leeNo ratings yet

- Writ of Habeas DataDocument11 pagesWrit of Habeas DataAlvin ClaridadesNo ratings yet

- Sema V ComelecDocument5 pagesSema V Comelecannlorenzo100% (5)

- Mala in Se and Mala Prohibita PEOPLE V MARIACOS, G.R. No. 188611, 16 June 2010 FactsDocument14 pagesMala in Se and Mala Prohibita PEOPLE V MARIACOS, G.R. No. 188611, 16 June 2010 FactsSean Asco RumaNo ratings yet

- Questions For CrimPro Mock BarDocument7 pagesQuestions For CrimPro Mock BarNeil AntipalaNo ratings yet

- Ormoc Sugar Co Vs Treasurer of Ormoc CityDocument5 pagesOrmoc Sugar Co Vs Treasurer of Ormoc CityMadelle PinedaNo ratings yet

- Atty. Soleng Batch 1: Principles and Doctrines in Criminal Procedure CasesDocument10 pagesAtty. Soleng Batch 1: Principles and Doctrines in Criminal Procedure CasesRabindranath S. Polito100% (1)

- Eu Procedural Law Oxford European Union Law Library 2Nd Edition Koen Lenaerts Full ChapterDocument67 pagesEu Procedural Law Oxford European Union Law Library 2Nd Edition Koen Lenaerts Full Chaptersteve.cohen414100% (4)

- Contreras V SolisDocument2 pagesContreras V SolisPaul SarangayaNo ratings yet

- 1 - HJS 2019 Mains Civil Law IDocument5 pages1 - HJS 2019 Mains Civil Law IMystic ClanNo ratings yet

- Bernardo v. People 123 SCRA 365 (1983)Document9 pagesBernardo v. People 123 SCRA 365 (1983)eubelromNo ratings yet

- 00423-082907atl Eight-IndictedDocument2 pages00423-082907atl Eight-IndictedlosangelesNo ratings yet

- PAUL LEE TAN vs. PAUL SYCIP and MERRITTO LIMDocument5 pagesPAUL LEE TAN vs. PAUL SYCIP and MERRITTO LIMRal CaldiNo ratings yet

- The Types of ArbitrationsDocument2 pagesThe Types of Arbitrationsnupur jhodNo ratings yet

- Vs. Kazuhiro Sugiyama and People of The Philippines: Socorro F. Ongkingco and Marie Paz B. OngkingcoDocument2 pagesVs. Kazuhiro Sugiyama and People of The Philippines: Socorro F. Ongkingco and Marie Paz B. OngkingcoAyen GNo ratings yet

- WarraichDocument48 pagesWarraichdenpcarNo ratings yet

- 41 - Pascual v. Universal Motors Corporation, 61 SCRA 121Document2 pages41 - Pascual v. Universal Motors Corporation, 61 SCRA 121Johnny EnglishNo ratings yet

- Osk Mca 144 2018.odtDocument18 pagesOsk Mca 144 2018.odtRudraksh LakraNo ratings yet

- Kidnapping and Abduction-IiDocument5 pagesKidnapping and Abduction-IiSergio RamosNo ratings yet

- Project-Tasks CertificateDocument23 pagesProject-Tasks CertificateNeal FariñasNo ratings yet

SOJ V Lantion

SOJ V Lantion

Uploaded by

Athina Maricar CabaseOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

SOJ V Lantion

SOJ V Lantion

Uploaded by

Athina Maricar CabaseCopyright:

Available Formats

The United States Government, on June 17, 1999, through Department of Foreign Affairs U. S.

Note Verbale No. 0522, requested the Philippine Government for the extradition of Mark

Jimenez, herein private respondent, to the United States. The request was forwarded the

following day by the Secretary of Foreign Affairs to the Department of Justice (DOJ). Pending

evaluation of the extradition documents by the DOJ, private respondent requested for copies of

the official extradition request and all pertinent documents and the holding in abeyance of the

proceedings. When his request was denied for being premature, private respondent resorted to an

action for mandamus, certiorari and prohibition. The trial court issued an order maintaining and

enjoining the DOJ from conducting further proceedings, hence, the instant petition.

Although the Extradition Law does not specifically indicate whether the extradition proceeding is

criminal, civil, or a special proceeding, it nevertheless provides the applicability of the Rules of

Court in the hearing of the petition insofar as practicable and not inconsistent with the summary

nature of the proceedings.

The prospective extraditee under Section 2[c] of Presidential Decree No. 1069 faces the threat of

arrest, not only after the extradition petition is filed in court, but even during the evaluation

proceeding itself by virtue of the provisional arrest allowed under the treaty and the

implementing law. Thus, the evaluation process, in essence, partakes of the nature of a criminal

investigation making available certain constitutional rights to the prospective extraditee. The

Court noted that there is a void in the provisions of the RP-US Extradition Treaty regarding the

basic due process rights available to a prospective extraditee at the evaluation stage of the

proceedings. The Court was constrained to apply the rules of fair play, the due process rights of

notice and hearing. Hence, petitioner was ordered to furnish private respondent copies of the

extradition request and its supporting papers and to grant the latter a reasonable time within

which to file his comment with supporting evidence.

INTERNATIONAL LAW; RULE OF PACTA SUNT SERVANDA; CONSTRUED. — The rule

of pacta sunt servanda, one of the oldest and most fundamental maxims of international law,

requires the parties to a treaty to keep their agreement therein in good faith. The observance of

our country's legal duties under a treaty is also compelled by Section 2, Article II of the

Constitution which provides that "[t]he Philippines renounces war as an instrument of national

policy, adopts the generally accepted principles of international law as part of the law of the land,

and adheres to the policy of peace, equality, justice, freedom, cooperation and amity with all

nations."

DOCTRINE OF INCORPORATION; WHEN APPLIED; CASE AT BAR. — Under the doctrine

of incorporation, rules of international law form part of the law of the land and no further

legislative action is needed to make such rules applicable in the domestic sphere (Salonga & Yap,

Public International Law, 1992 ed., p. 12). The doctrine of incorporation is applied whenever

municipal tribunals (or local courts) are confronted with situations in which there appears to be a

conflict between a rule of international law and the provisions of the constitution or statute of the

local state. Efforts should first be exerted to harmonize them, so as to give effect to both since it

is to be presumed that municipal law was enacted with proper regard for the generally accepted

principles of international law in observance of the Incorporation Clause in the above-cited

constitutional provision (Cruz, Philippine Political Law, 1996 ed., p. 55). In a situation, however,

where the conflict is irreconcilable and a choice has to be made between a rule of international

law and municipal law, jurisprudence dictates that municipal law should be upheld by the

municipal courts (Ichong vs. Hernandez, 101 Phil. 1155 [1957]; Gonzales vs. Hechanova, 9

SCRA 230 [1963]; In re: Garcia, 2 SCRA 984 [1961]) for the reason that such courts are organs

of municipal law and are accordingly bound by it in all circumstances (Salonga & Yap, op. cit.,

p. 13).

NO PRIMACY OF INTERNATIONAL LAW OVER NATIONAL OR MUNICIPAL LAW. —

The fact that international law has been made part of the law of the land does not pertain to or

imply the primacy of international law over national or municipal law in the municipal sphere.

The doctrine of incorporation, as applied in most countries, decrees that rules of international law

are given equal standing with, but are not superior to, national legislative enactments.

Accordingly, the principle lex posterior derogat priori takes effect — a treaty may repeal a statute

and a statute may repeal a treaty. In states where the constitution is the highest law of the land,

such as the Republic of the Philippines, both statutes and treaties may be invalidated if they are

in conflict with the constitution (Ibid.).

You might also like

- Spouses Avelina Rivera-Nolasco and Eduardo A. Nolasco, vs. Rural Bank of Pandi, Inc.Document3 pagesSpouses Avelina Rivera-Nolasco and Eduardo A. Nolasco, vs. Rural Bank of Pandi, Inc.Athina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

- United States v. Travis Robinson, 4th Cir. (2012)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Travis Robinson, 4th Cir. (2012)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Handbook-International Arbitration 3rd Ed P. CapperDocument102 pagesHandbook-International Arbitration 3rd Ed P. Cappercchesser100% (6)

- Annotation On Locus Standi 314 Scra 641Document6 pagesAnnotation On Locus Standi 314 Scra 641Johanna Mae L. AutidaNo ratings yet

- Case Digest - OBUS, MYRNA A.Document42 pagesCase Digest - OBUS, MYRNA A.Myrna Angay Obus100% (1)

- People V ElkanishDocument7 pagesPeople V ElkanishDuffy DuffyNo ratings yet

- Erlinda Sistual v. Atty. Eliordo Ogena, Ac. No. 9807, Feb 02, 2016Document2 pagesErlinda Sistual v. Atty. Eliordo Ogena, Ac. No. 9807, Feb 02, 2016Karen Joy MasapolNo ratings yet

- 28 - Lim v. Pacquing, 240 SCRA 649 - EspinosaDocument8 pages28 - Lim v. Pacquing, 240 SCRA 649 - EspinosaRudiverjungcoNo ratings yet

- Bar 2015 QuestionsDocument27 pagesBar 2015 QuestionsBrent DagbayNo ratings yet

- Abueva vs. Wood, 45 Phil 612Document13 pagesAbueva vs. Wood, 45 Phil 612fjl_302711No ratings yet

- 21-Cruz Vs IturraldeDocument6 pages21-Cruz Vs IturraldeLexter CruzNo ratings yet

- Wack Wack Golf vs. WonDocument4 pagesWack Wack Golf vs. WonWendy PeñafielNo ratings yet

- Salonga Vs Paño, GR No. L-59524Document13 pagesSalonga Vs Paño, GR No. L-59524Ashley Kate PatalinjugNo ratings yet

- Bayan vs. Executive SecretaryDocument49 pagesBayan vs. Executive SecretaryJerry SerapionNo ratings yet

- David Vs Gma Immunitability Vs ImpeachabilityDocument2 pagesDavid Vs Gma Immunitability Vs Impeachabilityanon_360675804No ratings yet

- LegProf - Soliman Santos, Jr. Vs Atty. Francisco Llamas AC 4749, (Jan. 20, 2000)Document1 pageLegProf - Soliman Santos, Jr. Vs Atty. Francisco Llamas AC 4749, (Jan. 20, 2000)Lu CasNo ratings yet

- Maneuvering Reconveyance of Client's Property To Self, EtcDocument5 pagesManeuvering Reconveyance of Client's Property To Self, EtcTricia Low SanchezNo ratings yet

- Estarija v. RanadaDocument14 pagesEstarija v. RanadaJ. JimenezNo ratings yet

- Full Text - Ynot Vs Iac 148 Scra 659Document2 pagesFull Text - Ynot Vs Iac 148 Scra 659arctikmarkNo ratings yet

- Sample Complaint For Collection For A Sum 1Document3 pagesSample Complaint For Collection For A Sum 1ALEXNo ratings yet

- Garcia vs. Board of Investments (G.R. No. 92024, November 9, 1990)Document8 pagesGarcia vs. Board of Investments (G.R. No. 92024, November 9, 1990)Carlota Nicolas VillaromanNo ratings yet

- Revised Penal C OdeDocument3 pagesRevised Penal C OdeDah Rin CavanNo ratings yet

- Hustler Magazine, Inc. v. Falwell, 485 U.S. 46 (1988)Document10 pagesHustler Magazine, Inc. v. Falwell, 485 U.S. 46 (1988)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. L-17115 Guevara Vs Gimenez (Functions and Duties of COA)Document3 pagesG.R. No. L-17115 Guevara Vs Gimenez (Functions and Duties of COA)MarkNo ratings yet

- Lim v. PacquingDocument46 pagesLim v. PacquingJD grey100% (1)

- Tax Rev Midterms CoverageDocument11 pagesTax Rev Midterms CoverageRegi Mabilangan ArceoNo ratings yet

- Quimsing v. TajanlangitDocument2 pagesQuimsing v. TajanlangitSteven OrtizNo ratings yet

- C3f - 3 - People v. SabayocDocument4 pagesC3f - 3 - People v. SabayocAaron AristonNo ratings yet

- Freeman vs. ReyesDocument7 pagesFreeman vs. ReyesBiboy GSNo ratings yet

- City Government of Baguio V MaswengDocument2 pagesCity Government of Baguio V MaswengLax ConcepcionNo ratings yet

- Ciocon-Reer v. LubaoDocument6 pagesCiocon-Reer v. LubaoKirk BejasaNo ratings yet

- Endencia V DavidDocument2 pagesEndencia V DavidMarius RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Bengzon vs. Senate Blue Ribbon Committee (203 SCRA 767)Document31 pagesBengzon vs. Senate Blue Ribbon Committee (203 SCRA 767)Mak FranciscoNo ratings yet

- Case Digests in Special Penal LawsDocument39 pagesCase Digests in Special Penal LawsLovelle Belaca-olNo ratings yet

- Tetangco Vs OmbudsmanDocument5 pagesTetangco Vs OmbudsmanRon AceNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 14129, July 31, 1962 People Vs ManantanDocument5 pagesG.R. No. 14129, July 31, 1962 People Vs ManantanJemard FelipeNo ratings yet

- Peña v. Court of Appeals, 193 SCRA 717 (1991)Document27 pagesPeña v. Court of Appeals, 193 SCRA 717 (1991)inno KalNo ratings yet

- Belgica vs. Ochoa DigestDocument16 pagesBelgica vs. Ochoa DigestRonnieEnggingNo ratings yet

- Doctrine: UCCP and BUCCI, Being Corporate Entities and Grantees of Primary Franchises, AreDocument2 pagesDoctrine: UCCP and BUCCI, Being Corporate Entities and Grantees of Primary Franchises, AreShandrei GuevarraNo ratings yet

- David Vs ArroyoDocument5 pagesDavid Vs ArroyoPortia WynonaNo ratings yet

- The Honorable Office of The Ombudsman v. Leovigildo Delos Reyes, JRDocument12 pagesThe Honorable Office of The Ombudsman v. Leovigildo Delos Reyes, JRRAINBOW AVALANCHENo ratings yet

- People v. Dionisio Vicente y QuintoDocument12 pagesPeople v. Dionisio Vicente y QuintoKuzan AokijiNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 138965 - Public Interest Center Inc. v. ElmaDocument3 pagesG.R. No. 138965 - Public Interest Center Inc. v. ElmaMA. TERIZ S CASTRONo ratings yet

- Valdez v. PeopleDocument27 pagesValdez v. Peoplekyla_0111No ratings yet

- Rod of Pampangga Vs PNBDocument2 pagesRod of Pampangga Vs PNBedmarkbaroyNo ratings yet

- Tatad v. Sec. of Doe - 281 Scra 330 (1997)Document16 pagesTatad v. Sec. of Doe - 281 Scra 330 (1997)Gol Lum100% (1)

- 62 Court Administrator v. QuinanolaDocument1 page62 Court Administrator v. QuinanolaNMNGNo ratings yet

- Olaquer vs. MC No. 4, 150 SCRA 144 (1987)Document36 pagesOlaquer vs. MC No. 4, 150 SCRA 144 (1987)Reginald Dwight FloridoNo ratings yet

- Current Status of Adoption in The PhilippinesDocument3 pagesCurrent Status of Adoption in The PhilippinesEugene Albert Olarte JavillonarNo ratings yet

- Marceliano L. Castellano For PetitionerDocument19 pagesMarceliano L. Castellano For PetitionerLien PatrickNo ratings yet

- Bacani Vs NacocoDocument1 pageBacani Vs NacocoHenteLAWcoNo ratings yet

- Nunga, Jr. v. Nunga 111, 574 SCRA 760 PDFDocument10 pagesNunga, Jr. v. Nunga 111, 574 SCRA 760 PDFenarguendo100% (1)

- Public Officers' Right To Retirement PayDocument5 pagesPublic Officers' Right To Retirement PayMiguel AlagNo ratings yet

- Francisco vs. House of Representatives Case DigestDocument4 pagesFrancisco vs. House of Representatives Case DigestEmma Ruby Aguilar-ApradoNo ratings yet

- GR No. L-13250 Oct. 29, 1971 COLLECTOR OF INTERNAL REVENUE v. ANTONIO CAMPOS RUEDADocument7 pagesGR No. L-13250 Oct. 29, 1971 COLLECTOR OF INTERNAL REVENUE v. ANTONIO CAMPOS RUEDAJuris AbiderNo ratings yet

- Candelaria - International Legal Concepts of Peace AgreementsDocument34 pagesCandelaria - International Legal Concepts of Peace AgreementsJoe PanlilioNo ratings yet

- Del Mar vs. Pva, 51 Scra 340Document5 pagesDel Mar vs. Pva, 51 Scra 340Atty Ed Gibson BelarminoNo ratings yet

- Dingcong vs. Guingona PDFDocument8 pagesDingcong vs. Guingona PDFAlthea Angela GarciaNo ratings yet

- ABAKADA GURO PARTY LIST OFFICERS SAMSON S. ALCANTARA v. EXECUTIVE SECRETARY EDUARDO ERMITADocument8 pagesABAKADA GURO PARTY LIST OFFICERS SAMSON S. ALCANTARA v. EXECUTIVE SECRETARY EDUARDO ERMITAMae TrabajoNo ratings yet

- Tilted Justice: First Came the Flood, Then Came the Lawyers.From EverandTilted Justice: First Came the Flood, Then Came the Lawyers.Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- MEDIA LAW 2. Department of Justice v. LantonDocument3 pagesMEDIA LAW 2. Department of Justice v. LantonKarl Angelo TulioNo ratings yet

- A. Relativity of Due ProcessDocument13 pagesA. Relativity of Due ProcessErika PotianNo ratings yet

- Secretary of Justice vs. LantionDocument23 pagesSecretary of Justice vs. LantionPamela Jane I. TornoNo ratings yet

- Virgines Calvo Doing Business Under The Name and Style Transorient Container Terminal Services, Inc Vs UCPB General Insurance Co.Document5 pagesVirgines Calvo Doing Business Under The Name and Style Transorient Container Terminal Services, Inc Vs UCPB General Insurance Co.Athina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

- Compania Maritima v. CADocument4 pagesCompania Maritima v. CAAthina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

- Reodica v. CADocument2 pagesReodica v. CAAthina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

- De Guzman v. CA, G.R. No. L-47822 (1988)Document4 pagesDe Guzman v. CA, G.R. No. L-47822 (1988)Athina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

- Torres-Madrid Brokerage v. Feb Mitsui Marine InsuranceDocument7 pagesTorres-Madrid Brokerage v. Feb Mitsui Marine InsuranceAthina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

- Theory of Error (Prelim)Document5 pagesTheory of Error (Prelim)Athina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

- Loadstar Shipping v. Malayan InsuranceDocument2 pagesLoadstar Shipping v. Malayan InsuranceAthina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

- 1.6 - Acceleration Due To GravityDocument5 pages1.6 - Acceleration Due To GravityAthina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

- Saludo v. CA, G.R. No. 95536Document5 pagesSaludo v. CA, G.R. No. 95536Athina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

- Ernesto L. Natividad, Petitioner, vs. Fernando Mariano, Andres Mariano and Doroteo Garcia, RespondentsDocument2 pagesErnesto L. Natividad, Petitioner, vs. Fernando Mariano, Andres Mariano and Doroteo Garcia, RespondentsAthina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

- Davao New Town Development CorporationDocument3 pagesDavao New Town Development CorporationAthina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

- Dionisia L. Reyes, Petitioner, vs. Ricardo L. Reyes, Lazaro L. Reyes, Narciso L. Reyes and Marcelo L. Reyes, Respondents.Document3 pagesDionisia L. Reyes, Petitioner, vs. Ricardo L. Reyes, Lazaro L. Reyes, Narciso L. Reyes and Marcelo L. Reyes, Respondents.Athina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

- Eufrocina Nieves, As Represented by Her Attorney-In-fact, Lazaro Villarosa, JR., Petitioner, vs. Ernesto Duldulao and Felipe Pajarillo, RespondentsDocument2 pagesEufrocina Nieves, As Represented by Her Attorney-In-fact, Lazaro Villarosa, JR., Petitioner, vs. Ernesto Duldulao and Felipe Pajarillo, RespondentsAthina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

- Victoria P. Cabral, Petitioner, vs. Heirs of Florencio Adolfo and Heirs of Elias Policarpio, RespondentsDocument4 pagesVictoria P. Cabral, Petitioner, vs. Heirs of Florencio Adolfo and Heirs of Elias Policarpio, RespondentsAthina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

- Otilia Sta. Ana, Petitioner, vs. Spouses Leon G. CarpoDocument3 pagesOtilia Sta. Ana, Petitioner, vs. Spouses Leon G. CarpoAthina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

- Casent Realty Dev't Corp v. Philbanking Corporation (2007)Document2 pagesCasent Realty Dev't Corp v. Philbanking Corporation (2007)Athina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

- Pre-Trial Brief Peter Cruz - PlaintiffDocument5 pagesPre-Trial Brief Peter Cruz - PlaintiffbananayellowsharpieNo ratings yet

- 35th BCI Moot Court Competition 2019 Respondent Memorial Problem 1 PDFDocument14 pages35th BCI Moot Court Competition 2019 Respondent Memorial Problem 1 PDFDebashish PandaNo ratings yet

- People V ReyesDocument3 pagesPeople V ReyesRoselyn PascobelloNo ratings yet

- Department OF Budget AND Management Department OF Interior AND Local GovernmentDocument2 pagesDepartment OF Budget AND Management Department OF Interior AND Local GovernmentdonyacarlottaNo ratings yet

- Freeborn County AnswerDocument4 pagesFreeborn County AnswerMark WassonNo ratings yet

- Sample Case-People vs. Anson (G.R. No. 175940)Document13 pagesSample Case-People vs. Anson (G.R. No. 175940)Aaron BeasleyNo ratings yet

- Agrarian Law (CASE DIGEST) Fatima C. Dela PenaDocument17 pagesAgrarian Law (CASE DIGEST) Fatima C. Dela PenaFatima Dela PeñaNo ratings yet

- Republic vs. Luzon Stevedoring CorporationDocument4 pagesRepublic vs. Luzon Stevedoring Corporationcassandra leeNo ratings yet

- Writ of Habeas DataDocument11 pagesWrit of Habeas DataAlvin ClaridadesNo ratings yet

- Sema V ComelecDocument5 pagesSema V Comelecannlorenzo100% (5)

- Mala in Se and Mala Prohibita PEOPLE V MARIACOS, G.R. No. 188611, 16 June 2010 FactsDocument14 pagesMala in Se and Mala Prohibita PEOPLE V MARIACOS, G.R. No. 188611, 16 June 2010 FactsSean Asco RumaNo ratings yet

- Questions For CrimPro Mock BarDocument7 pagesQuestions For CrimPro Mock BarNeil AntipalaNo ratings yet

- Ormoc Sugar Co Vs Treasurer of Ormoc CityDocument5 pagesOrmoc Sugar Co Vs Treasurer of Ormoc CityMadelle PinedaNo ratings yet

- Atty. Soleng Batch 1: Principles and Doctrines in Criminal Procedure CasesDocument10 pagesAtty. Soleng Batch 1: Principles and Doctrines in Criminal Procedure CasesRabindranath S. Polito100% (1)

- Eu Procedural Law Oxford European Union Law Library 2Nd Edition Koen Lenaerts Full ChapterDocument67 pagesEu Procedural Law Oxford European Union Law Library 2Nd Edition Koen Lenaerts Full Chaptersteve.cohen414100% (4)

- Contreras V SolisDocument2 pagesContreras V SolisPaul SarangayaNo ratings yet

- 1 - HJS 2019 Mains Civil Law IDocument5 pages1 - HJS 2019 Mains Civil Law IMystic ClanNo ratings yet

- Bernardo v. People 123 SCRA 365 (1983)Document9 pagesBernardo v. People 123 SCRA 365 (1983)eubelromNo ratings yet

- 00423-082907atl Eight-IndictedDocument2 pages00423-082907atl Eight-IndictedlosangelesNo ratings yet

- PAUL LEE TAN vs. PAUL SYCIP and MERRITTO LIMDocument5 pagesPAUL LEE TAN vs. PAUL SYCIP and MERRITTO LIMRal CaldiNo ratings yet

- The Types of ArbitrationsDocument2 pagesThe Types of Arbitrationsnupur jhodNo ratings yet

- Vs. Kazuhiro Sugiyama and People of The Philippines: Socorro F. Ongkingco and Marie Paz B. OngkingcoDocument2 pagesVs. Kazuhiro Sugiyama and People of The Philippines: Socorro F. Ongkingco and Marie Paz B. OngkingcoAyen GNo ratings yet

- WarraichDocument48 pagesWarraichdenpcarNo ratings yet

- 41 - Pascual v. Universal Motors Corporation, 61 SCRA 121Document2 pages41 - Pascual v. Universal Motors Corporation, 61 SCRA 121Johnny EnglishNo ratings yet

- Osk Mca 144 2018.odtDocument18 pagesOsk Mca 144 2018.odtRudraksh LakraNo ratings yet

- Kidnapping and Abduction-IiDocument5 pagesKidnapping and Abduction-IiSergio RamosNo ratings yet

- Project-Tasks CertificateDocument23 pagesProject-Tasks CertificateNeal FariñasNo ratings yet