Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 8 PDF

The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 8 PDF

Uploaded by

Mat WilliamsCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Laumann (2013) Colonial Africa (1884-1994) 1Document9 pagesLaumann (2013) Colonial Africa (1884-1994) 1onyame38380% (2)

- The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 6 PDFDocument906 pagesThe Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 6 PDFMat Williams100% (1)

- (Philip D. Curtin.) The World and The West TheDocument308 pages(Philip D. Curtin.) The World and The West TheChenault14No ratings yet

- Africans and The Politics of Popular CultureDocument347 pagesAfricans and The Politics of Popular CulturenandacoboNo ratings yet

- Encyclopedia of African History PDFDocument1,864 pagesEncyclopedia of African History PDFfictitious30100% (16)

- A Short History of African Art (Art Ebook)Document418 pagesA Short History of African Art (Art Ebook)CITILIMITS91% (11)

- Jean Suret-Canale, French Colonialism in Tropical Africa, 1900-1945. New York Pica Press, 1971Document530 pagesJean Suret-Canale, French Colonialism in Tropical Africa, 1900-1945. New York Pica Press, 1971OSGuinea100% (1)

- General History of Africa Vol 2: Ancient Civilizations of AfricaDocument825 pagesGeneral History of Africa Vol 2: Ancient Civilizations of Africaalagemo100% (7)

- The History of Northern AfricaDocument196 pagesThe History of Northern AfricaCosmin_Isv75% (4)

- (John Middleton, Joseph C. Miller) New Encyclopedia of AfricaDocument600 pages(John Middleton, Joseph C. Miller) New Encyclopedia of AfricaAbdellatifTalibi100% (3)

- (Social History of Africa Series) Florence Bernault, Janet Roitman-A History of Prison and Confinement in Africa-Heinemann (2003) PDFDocument297 pages(Social History of Africa Series) Florence Bernault, Janet Roitman-A History of Prison and Confinement in Africa-Heinemann (2003) PDFAndrei DragomirNo ratings yet

- Uncovering The History of Africans in AsiaDocument209 pagesUncovering The History of Africans in AsiaJaron K. Epstein100% (4)

- A History of The Colonization of Africa by Alien RacesDocument362 pagesA History of The Colonization of Africa by Alien RacesJohn Jackson100% (5)

- General History of Africa - Volume VI - Africa in The Nineteenth Century Until The 1880sDocument887 pagesGeneral History of Africa - Volume VI - Africa in The Nineteenth Century Until The 1880sDrk_Mtr100% (6)

- General History of Africa Vol 8Document1,039 pagesGeneral History of Africa Vol 8liberatormag100% (5)

- General History of Africa, Abridged Edition, V.4 Africa From The Twelfth To The Sixteenth CenturyDocument313 pagesGeneral History of Africa, Abridged Edition, V.4 Africa From The Twelfth To The Sixteenth CenturyDaniel Williams100% (1)

- Unesco Historyof Africa Vol6Document887 pagesUnesco Historyof Africa Vol6jnukpezahNo ratings yet

- General History of Africa, Abridged Edition, V.2 Ancient Civilizations of AfricaDocument437 pagesGeneral History of Africa, Abridged Edition, V.2 Ancient Civilizations of AfricaDaniel Williams100% (3)

- The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 1 From The Earliest Times To C. 500 B.C.Document1,107 pagesThe Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 1 From The Earliest Times To C. 500 B.C.Mahmoud Hassino86% (7)

- Volume V - Africa From The Sixteenth To The Eighteenth CenturyDocument1,071 pagesVolume V - Africa From The Sixteenth To The Eighteenth CenturyNaja Nzumafo Mansakewoo100% (5)

- General History of Africa Vol 3: Africa From The Seventh To The Eleventh CenturyDocument891 pagesGeneral History of Africa Vol 3: Africa From The Seventh To The Eleventh Centuryalagemo100% (7)

- African Histoty VDocument511 pagesAfrican Histoty VJohan Westerholm100% (2)

- General History of Africa, Abridged Edition, V.3 Africa From The Seventh To The Eleventh CenturyDocument418 pagesGeneral History of Africa, Abridged Edition, V.3 Africa From The Seventh To The Eleventh CenturyDaniel Williams100% (1)

- The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 1 From The Earliest Times To C. 500 B.C.Document1,107 pagesThe Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 1 From The Earliest Times To C. 500 B.C.AnTUmbraNo ratings yet

- South Atlantic HistoryDocument282 pagesSouth Atlantic HistoryGilberto Guerra100% (3)

- Early African HistoryDocument52 pagesEarly African HistoryRashard Dyess-Lane75% (4)

- Vol1Document142 pagesVol1Pradeep Mangottil Ayyappan100% (5)

- History of AfricaDocument208 pagesHistory of AfricaDashi Mambo100% (4)

- Africa Before Slavery and African ProverbsDocument4 pagesAfrica Before Slavery and African ProverbsOrockjoNo ratings yet

- General History of Africa, Abridged Edition, V.1 Methodology and African PrehistoryDocument367 pagesGeneral History of Africa, Abridged Edition, V.1 Methodology and African PrehistoryDaniel WilliamsNo ratings yet

- African Colonial StatesDocument16 pagesAfrican Colonial Statesjozsef10No ratings yet

- (African Systems of Thought) Paulin J. Hountondji - African Philosophy - Myth and Reality (1996, Indiana University Press)Document240 pages(African Systems of Thought) Paulin J. Hountondji - African Philosophy - Myth and Reality (1996, Indiana University Press)Fabricio Neves100% (1)

- CSS 132 Ethnography of NigeriaDocument86 pagesCSS 132 Ethnography of NigeriaIkenna Ohiaeri100% (3)

- African Studen MovementsDocument199 pagesAfrican Studen MovementsPedro Bravo ReinosoNo ratings yet

- Area Handbook - SudanDocument360 pagesArea Handbook - SudanRobert Vale50% (2)

- (2008) The Arts of The Muslim HausaDocument5 pages(2008) The Arts of The Muslim HausaAwalludin RamleeNo ratings yet

- A Nervous State by Nancy Rose HuntDocument42 pagesA Nervous State by Nancy Rose HuntDuke University Press100% (2)

- Empires of Medieval Africa (136-153)Document18 pagesEmpires of Medieval Africa (136-153)Thiago Thiago0% (1)

- African Kings and Black Slaves: Sovereignty and Dispossession in the Early Modern AtlanticFrom EverandAfrican Kings and Black Slaves: Sovereignty and Dispossession in the Early Modern AtlanticRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- The Cambridge Economic History of The United States Vol 01 - The Colonial Era PDFDocument461 pagesThe Cambridge Economic History of The United States Vol 01 - The Colonial Era PDFMolnár Levente0% (1)

- Cambridge World History of Slavery Vol 3 - The Early Modern AgeDocument755 pagesCambridge World History of Slavery Vol 3 - The Early Modern AgeThiago Krause100% (2)

- 17) Ross, A Concise History of South AfricaDocument271 pages17) Ross, A Concise History of South AfricaGianmarco RizzoNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Development and Social Change A Global Perspective 6Th Edition by Mcmichale Isbn 1452275904 978145227590 Full Chapter PDFDocument33 pagesTest Bank For Development and Social Change A Global Perspective 6Th Edition by Mcmichale Isbn 1452275904 978145227590 Full Chapter PDFkerry.hafenstein856100% (11)

- Development and Social Change A Global Perspective 6th Edition by McMichale ISBN Test BankDocument12 pagesDevelopment and Social Change A Global Perspective 6th Edition by McMichale ISBN Test Bankedward100% (24)

- AFRICAN Women and Apartheid Migration and SettlementDocument297 pagesAFRICAN Women and Apartheid Migration and SettlementDragon JudahNo ratings yet

- General History Africa VIDocument887 pagesGeneral History Africa VILudwig SzohaNo ratings yet

- MC MichaelDocument10 pagesMC MichaelthandiNo ratings yet

- General History Africa VIIIDocument1,039 pagesGeneral History Africa VIIILudwig SzohaNo ratings yet

- Grade 8-9 Social Studies - MR 6pointsDocument102 pagesGrade 8-9 Social Studies - MR 6pointsjohnchimfwembe717No ratings yet

- Christopher Harrison France and Islam in West PDFDocument256 pagesChristopher Harrison France and Islam in West PDFNam NguyenNo ratings yet

- Barbara L. Solow - Slavery and The Rise of The Atl (BookFi) PDFDocument365 pagesBarbara L. Solow - Slavery and The Rise of The Atl (BookFi) PDFneetuNo ratings yet

- The Cambridge History of Nationhood and Nationalism 2 Volume Hardback Set Carmichael Full ChapterDocument67 pagesThe Cambridge History of Nationhood and Nationalism 2 Volume Hardback Set Carmichael Full Chapterloretta.donnelly923100% (7)

- Development and Social Change A Global Perspective 6th Edition Mcmichale Test BankDocument11 pagesDevelopment and Social Change A Global Perspective 6th Edition Mcmichale Test Bankangelicaperezberxonytcp100% (15)

- The African Poor 1987 IliffeDocument397 pagesThe African Poor 1987 Iliffewsoors3098No ratings yet

- The Scramble For Africa Final ProjectDocument7 pagesThe Scramble For Africa Final Projectr2wq9zv5ycNo ratings yet

- Sudan HistoryDocument21 pagesSudan Historyopoka2010No ratings yet

- Reading #1 2Document33 pagesReading #1 2m55ppf8zv5No ratings yet

- Wayne C. McWilliams - Harry Piotrowski - The World Since 1945 - A History of International Relations-Lynne Rienner Publishers (1997)Document632 pagesWayne C. McWilliams - Harry Piotrowski - The World Since 1945 - A History of International Relations-Lynne Rienner Publishers (1997)alamgeerNo ratings yet

- The White Redoubt The Great Powers and The Struggle For Southern Africa 1960 1980 1St Edition Filipe Ribeiro de Meneses All ChapterDocument68 pagesThe White Redoubt The Great Powers and The Struggle For Southern Africa 1960 1980 1St Edition Filipe Ribeiro de Meneses All Chapteralan.lewis489100% (9)

- 02 BOC V OgarioDocument1 page02 BOC V OgarioGabriel CruzNo ratings yet

- Pesach Guide 2016Document88 pagesPesach Guide 2016joy sherriNo ratings yet

- Cash and RecievablesDocument60 pagesCash and Recievablesአንተነህ የእናቱ100% (1)

- 'FFFFDocument3 pages'FFFFajay pawaraNo ratings yet

- Pauline Ethics 1st Tri 2022-2023 TASKS - REQUIREMENTDocument3 pagesPauline Ethics 1st Tri 2022-2023 TASKS - REQUIREMENTDeborah Keith UpanoNo ratings yet

- Draft Program Turn-OverDocument1 pageDraft Program Turn-OverPamela TabayNo ratings yet

- How To Pass A Prop Firm Challenge 1Document11 pagesHow To Pass A Prop Firm Challenge 1benyaminseptiardi08simamoraNo ratings yet

- Eee111 Proposal TemplateDocument3 pagesEee111 Proposal TemplateAina SaffiyaNo ratings yet

- Declarations-: (Signature & Stamp of The Buyer)Document3 pagesDeclarations-: (Signature & Stamp of The Buyer)akakakshanNo ratings yet

- Thomas Lawton Evans Jr. IndictmentDocument3 pagesThomas Lawton Evans Jr. IndictmentLeigh EganNo ratings yet

- 37 Bitte v. Jonas (2015)Document3 pages37 Bitte v. Jonas (2015)Aloysius BresnanNo ratings yet

- Client Solutions Advisor - Independent Contractor Agreement BairesDev LLC - Bret BrockbankDocument8 pagesClient Solutions Advisor - Independent Contractor Agreement BairesDev LLC - Bret BrockbankPaulo BaraldiNo ratings yet

- Politicization of The Public Service in TanzaniaDocument13 pagesPoliticization of The Public Service in TanzaniaAlbert Msando100% (1)

- Uz-Kor Gas Chemical Ёқилғи системаси, Факел системаси ва Резервуарлар парки хақидаDocument35 pagesUz-Kor Gas Chemical Ёқилғи системаси, Факел системаси ва Резервуарлар парки хақидаNaurizbay SultanovNo ratings yet

- Fouls and Violations of Basketball: Physical Education 11 Activity Sheets (4 Quarter)Document3 pagesFouls and Violations of Basketball: Physical Education 11 Activity Sheets (4 Quarter)Angel DiazNo ratings yet

- Gazette of SarpanchesDocument56 pagesGazette of SarpanchesThappetla SrinivasNo ratings yet

- Notice No.2 Rules For The Manufacture Testing and Certification of Materials July 2Document3 pagesNotice No.2 Rules For The Manufacture Testing and Certification of Materials July 2taddeoNo ratings yet

- California Unveils Latest Cannabis RulesDocument15 pagesCalifornia Unveils Latest Cannabis RulesJohn sonNo ratings yet

- Attachment of DecreeDocument15 pagesAttachment of DecreeHrishika Netam100% (1)

- Krabi Riviera Company Ltd. - 251/13 Moo.2, Ao Nang, Muang, Krabi 81000 ThailandDocument2 pagesKrabi Riviera Company Ltd. - 251/13 Moo.2, Ao Nang, Muang, Krabi 81000 ThailandJames OtienoNo ratings yet

- Chicago Lawyers&apos Committee For Civil Rights Under Law, Inc. v. Craigslist, Inc. - Document No. 73Document15 pagesChicago Lawyers&apos Committee For Civil Rights Under Law, Inc. v. Craigslist, Inc. - Document No. 73Justia.comNo ratings yet

- A 031 C 8Document32 pagesA 031 C 8Shakil Khan100% (1)

- Application For Review of Research Involving HumanDocument3 pagesApplication For Review of Research Involving Humanbillie_haraNo ratings yet

- Full General KnowledgeDocument81 pagesFull General Knowledgehunain84100% (1)

- Women and DevelopmentDocument4 pagesWomen and DevelopmentnadiaafzalNo ratings yet

- Criminal Justice SystemDocument26 pagesCriminal Justice SystemAman rai100% (1)

- AVE MARIA Court MotionDocument35 pagesAVE MARIA Court MotionNews-PressNo ratings yet

- Employee Benefits Questions 2Document1 pageEmployee Benefits Questions 2Ronnah Mae FloresNo ratings yet

- Labad Vs - UspDocument8 pagesLabad Vs - UspGe LatoNo ratings yet

- NP 1115 S875WP1TPSDocument117 pagesNP 1115 S875WP1TPSChinnaNo ratings yet

The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 8 PDF

The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 8 PDF

Uploaded by

Mat WilliamsOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 8 PDF

The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 8 PDF

Uploaded by

Mat WilliamsCopyright:

Available Formats

THE CAMBRIDGE HISTORY

OF A F R I C A

General Editors: J. D . F A G E a n d ROLAND OLIVER

Volume 8

from c. 1940 to c. 1975

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE CAMBRIDGE

H I S T O R Y OF

AFRICA

Volume 8

from c. 1940 to c. 1975

edited by

MICHAEL CROWDER

I CAMBRIDGE

UNIVERSITY PRESS

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE

The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom

CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS

The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge C B 2 2RU, U K

4 0 West 20th Street, N e w York, N T 1 0 0 1 1 — 4 2 1 1 , USA

4 7 7 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, v i e 3 2 0 7 , Australia

Ruiz de Alarcon 1 3 , 2 8 0 1 4 Madrid, Spain

Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8 0 0 1 , South Africa

http://www. cambridge.org

© Cambridge University Press 1 9 8 4

This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception

and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements,

no reproduction of any part may take place without

the written permission of Cambridge University Press.

First published 1 9 8 4

Reprinted 1 9 8 8 , 1 9 9 ; , 1 9 9 9 , 2 0 0 0 , 2003

Printed and bound in the United Kingdom

at the University Press, Cambridge

Library of Congress catalogue card number: 76—2261

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

The Cambridge history of Africa

Vol. 8: From c. 1 9 4 0 to c. 1 9 7 ;

1. Africa — History

I. Crowder, Michael

960 DT20

ISBN 0 ;2i 2 2 4 0 9 8 (v. 8)

UP

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CONTENTS

List of figures page x

Preface xiii

Introduction i

b y M I C H A E L C R O W D E R , Professor of History,

University of Botswana

The Second World War: prelude to decolonisation

in Africa 8

by M I C H A E L CROWDER

T h e course o f the w a r o n A f r i c a n soil 15

T h e impact o f the Second W o r l d W a r o n the

colonial powers 20

T h e impact o f the Second W o r l d W a r o n

Africans 29

Colonial reforms 40

Conclusion 47

Decolonisation and the problems of independence 5 2

b y t h e l a t e B I L L Y J . DUDLEY, formerly Department

of Political Science, University of Ibadan

Paths to independence 54

T h e constitutional inheritance 64

The bureaucracy and the e c o n o m y 70

Social mobilisation 75

T h e military a n d militarism 87

Political leadership and political succession 93

Pan-Africanism since 1 9 4 0 95

b y I A N D U F F I E L D , Department of History,

University of Edinburgh

The 1945 P a n - A f r i c a n C o n g r e s s 101

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CONTENTS

T h e African diaspora and post-194 5

Pan-Africanism 104

T h e road to the Organisation o f African Unity 109

Nationalism, regionalism and African unity 117

Pan-Africanism and the armed liberation

struggles 126

P a n - A f r i c a n i s m a n d w o r l d affairs 131

Pan-Africanism and culture 13 8

l z

4 Social and cultural change 4

b y J. D . Y . P E E L , Professor of Sociology, University

of Liverpool

Patterns o f migration 145

The growth o f towns 15 o

C h a n g i n g bases o f identity 15 3

Class formation 162

State a n d society 184

Cultural change 187

5 T h e economic evolution o f developing Africa 192

b y A D E B A Y O A D E D E J I , United Nations

Under-Secretary-General and Executive Secretary,

Economic Commission for Africa

T h e colonial e c o n o m y o n the e v e o f the Second

World War 193

T h e performance o f the African e c o n o m y ,

6

1940-75 19

Structural and sectoral changes 205

T h e search for e c o n o m i c integration 2 31

Africa and the international e c o n o m y 238

Conclusion 248

6 Southern Africa 251

b y F R A N C I S W I L S O N , Professor of Economics,

University of Cape Town

Industrial revolution in South Africa, 1 9 3 6 - 7 6 260

Politics 1936-60 277

South Africa's neighbours 294

Maintaining the white republic, 1 9 6 1 - 7 6 301

T h e struggle for liberation, 1 9 6 1 - 7 7 310

Conclusion 328

vi

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CONTENTS

7 English-speaking West Africa 3 31

by D A V I D WILLIAMS

T h e impact o f the S e c o n d W o r l d W a r 3 33

8

Decolonisation 33

T h e problems o f independence 355

Social, cultural and educational

1

developments 37

R e g i o n a l relations 375

Economics 377

Conclusion 3 81

8 East and Central Africa 383

b y C H E R R Y G E R T Z E L , School of Social Sciences,

The Flinders University of South Australia

Political and constitutional d e v e l o p m e n t 385

Economic development 416

Social change 431

Education 444

Inter-state and external relations 451

8

9 T h e Horn of Africa 45

by C H R I S T O P H E R C L A P H A M , Department of

Politics, University of Lancaster

8

T h e setting 45

T h e restored Ethiopian empire, 1 9 4 1 - 5 2 461

T h e peripheral administrations 464

P o l i t i c i s a t i o n a n d its o u t c o m e 467

Political decay and revolution 473

Regional and international relationships 480

Social and e c o n o m i c change 484

Urbanisation and education 487

Economic development 492

Agriculture 496

Conclusion 5 00

10 Egypt, Libya and the Sudan 502

by H A N S - H E I N O K O P I E T Z ,

and PAMELA A N N SMITH

Decolonisation and independence 504

International relations 546

Social and cultural change 55

vii

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CONTENTS

Economic development 55 5

Conclusion 5 61

11 T h e Maghrib 5 64

b y C L E M E N T H E N R Y M O O R E , Visiting Professor,

American University of Beirut

The struggle for independence 5 66

8 2

The independent regimes 5

Strategies o f d e v e l o p m e n t 5 94

F o r e i g n affairs 604

12 French-speaking tropical Africa 611

by R U T H SCHACHTER MORGENTHAU,

Department of Political Science, Brandeis University

and L U C Y C R E E V E Y B E H R M A N , University of

Pennsylvania

Formal political decolonisation 615

Political parties a n d leaders, 1944-60 625

T h e difficulties o f n a t i o n - b u i l d i n g , 1 9 6 0 - 7 5 636

Social, e c o n o m i c and cultural change 649

International relations 663

13 Madagascar 674

b y B O N A R A. G o w

Political and constitutional history:

pre-independence 674

Political and constitutional history:

post-independence 680

Social and cultural change 685

Educational development 689

Economic development 692

14 Zaire, Rwanda and Burundi 698

b y M . C R A W F O R D Y O U N G , Department of Political

Science, University of Wisconsin-Madison

T h e rise o f n a t i o n a l i s m 707

I n d e p e n d e n c e a n d crisis in Z a i r e 717

Internationalisation o f the * C o n g o crisis' 722

The N e w Regime, 1965-75 731

R w a n d a : consolidation o f the H u t u regime 734

viii

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CONTENTS

Burundi: from monarchy to Tutsi republicanism,

1962-75 73 5

Economic change 739

Social and cultural c h a n g e 743

Educational development 749

International relations 751

15 Portuguese-speaking Africa 755

by B A S I L DAVIDSON

Colonial continuity and expansion, 1945-60 758

T h e rise o f n a t i o n a l i s m 764

D e v e l o p m e n t s in colonial policy, 1 9 6 1 - 7 5 772

T h e f i g h t f o r i n d e p e n d e n c e , 1961—75 780

T h e politics o f liberation: theory and practice 798

Appendix: E q u a t o r i a l G u i n e a , c. 1 9 4 0 t o 1 9 7 5 806

Bibliographical essays 811

Bibliography 905

Index 963

ix

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

FIGURES

1 Africa, 1940 page 3

2 Africa, 1975 6

3 Africa, 1946 19

4 Africa: the path to independence, 1 9 5 6 - 6 6 55

5 Major vegetation zones 194

6 Primary commodities - export prices indices 202

7 D e v e l o p i n g Africa: structure o f gross domestic

product, 1960-75 206

8 Staple and cash crops 210

9 Cash crops 211

10 F a c t o r y w o r k e r s as a p r o p o r t i o n o f t h e t o t a l p o p u l a t i o n 2 1 7

11 T r a n s p o r t 222

12 R e g i o n a l a n d s u b - r e g i o n a l o r g a n i s a t i o n s f o r c o

operation and integration 234

13 E x p o r t s a n d i m p o r t s i n d e v e l o p i n g A f r i c a , 1 9 6 0 - 7 5 239

1 4 B a l a n c e o f p a y m e n t s d e f i c i t s in d e v e l o p i n g A f r i c a ,

1960-75 242

15 T h e Republic o f South Africa, Swaziland and L e s o t h o 254

16 Namibia and B o t s w a n a 256

17 Ghana 342

18 Nigeria, 1964 347

19 Sierra L e o n e and Liberia 3 51

20 N i g e r i a : t h e 12 s t a t e s 363

21 The Gambia 368

22 Uganda, K e n y a and Tanzania 384

23 Rhodesia, Z a m b i a and M a l a w i 388

24 E t h i o p i a , S o m a l i a and the F r e n c h T e r r i t o r y o f the

A f a r s a n d Issas 459

25 Egypt 505

26 T h e Sudan 521

27 Libya 535

28 T h e M a g h r i b c. 1 9 7 5 565

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

FIGURES

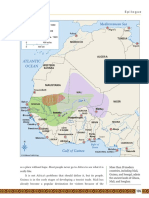

29 F r a n c o p h o n e tropical A f r i c a : the w e s t e r n states 612

30 F r a n c o p h o n e t r o p i c a l A f r i c a : t h e e a s t e r n states 613

31 Madagascar 676

32 Zaire, R w a n d a and Burundi 699

33 A n g o l a : the risings o f 1961 771

34 G u i n e a - B i s s a u : l a u n c h i n g the w a r o f liberation. 780

35 N o r t h e r n M o z a m b i q u e after S e p t e m b e r 1 9 6 4 781

36 G u i n e a - B i s s a u : g e n e r a l p o s i t i o n in late 1968 a n d after 787

37 M o z a m b i q u e after l a t e 1 9 7 3 791

38 A n g o l a in 1 9 7 0 a n d after 792

xi

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

PREFACE

In the English-speaking w o r l d , the C a m b r i d g e histories h a v e

since the b e g i n n i n g o f the c e n t u r y set the pattern for m u l t i - v o l u m e

w o r k s o f history, w i t h chapters written b y experts o n a particular

t o p i c , a n d unified b y the g u i d i n g h a n d o f v o l u m e editors o f senior

s t a n d i n g . The Cambridge Modern History, p l a n n e d b y L o r d A c t o n ,

appeared in sixteen v o l u m e s b e t w e e n 1902 a n d 1 9 1 2 . It w a s

f o l l o w e d b y The Cambridge Ancient History, The Cambridge Medieval

History, The Cambridge History of English Literature, a n d C a m b r i d g e

Histories o f India, o f Poland, and o f the British E m p i r e . T h e

o r i g i n a l Modern History h a s n o w b e e n r e p l a c e d b y The New

Cambridge Modern History i n f o u r t e e n v o l u m e s , a n d The Cambridge

Economic History of Europe is n o w c o m p l e t e . O t h e r C a m b r i d g e

Histories recently undertaken include a history o f Islam, o f A r a b i c

l i t e r a t u r e , o f t h e B i b l e t r e a t e d as a c e n t r a l d o c u m e n t o f a n d

influence o n W e s t e r n civilisation, and o f Iran, C h i n a and Latin

America.

It w a s d u r i n g t h e l a t e r 1 9 5 0 s t h a t t h e S y n d i c s o f t h e C a m b r i d g e

U n i v e r s i t y P r e s s first b e g a n t o e x p l o r e t h e p o s s i b i l i t y o f e m b a r k i n g

on a C a m b r i d g e History o f Africa. B u t they were then advised

that the time w a s n o t y e t ripe. T h e serious appraisal o f the past

o f Africa b y historians and archaeologists had hardly been

u n d e r t a k e n b e f o r e 1 9 4 8 , t h e y e a r w h e n u n i v e r s i t i e s first b e g a n t o

appear in increasing n u m b e r s in the vast reach o f the African

continent south o f the Sahara and n o r t h o f the L i m p o p o , and the

t i m e t o o w h e n u n i v e r s i t i e s o u t s i d e A f r i c a first b e g a n t o t a k e s o m e

n o t i c e o f its h i s t o r y . I t w a s i m p r e s s e d u p o n t h e S y n d i c s t h a t t h e

most urgent need o f such a y o u n g , b u t also very rapidly a d v a n c i n g

branch o f historical studies, w a s a journal o f international

standing t h r o u g h w h i c h the results o f o n g o i n g research m i g h t b e

disseminated. In i960, therefore, the C a m b r i d g e University Press

l a u n c h e d The Journal of African History, w h i c h g r a d u a l l y d e m o n

strated the a m o u n t o f w o r k b e i n g undertaken t o establish the past

xiii

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

PREFACE

o f A f r i c a as a n i n t e g r a t e d w h o l e r a t h e r t h a n - as it h a d u s u a l l y

b e e n v i e w e d b e f o r e - as t h e s t o r y o f a s e r i e s o f i n c u r s i o n s i n t o

the continent b y p e o p l e s c o m i n g f r o m outside, f r o m the M e d i

terranean basin, the N e a r East o r western E u r o p e . T h i s m o v e m e n t

will o f course c o n t i n u e a n d d e v e l o p further, b u t the increasing

facilities a v a i l a b l e f o r i t s p u b l i c a t i o n s o o n b e g a n t o d e m o n s t r a t e

a n e e d t o a s s e s s b o t h w h a t h a d b e e n d o n e , a n d w h a t still n e e d e d

to b e d o n e , in the light o f s o m e general historical perspective for

the continent.

T h e S y n d i c s therefore returned t o their original c h a r g e , a n d in

1 9 6 6 t h e f o u n d i n g e d i t o r s o f The Journal of African History

accepted a commission to b e c o m e the general editors o f a

Cambridge History of Africa. T h e y f o u n d it a d a u n t i n g t a s k t o d r a w

up a plan for a co-operative w o r k c o v e r i n g a history w h i c h w a s

in a c t i v e p r o c e s s o f e x p l o r a t i o n b y s c h o l a r s o f m a n y n a t i o n s ,

s c a t t e r e d o v e r a fair p a r t o f t h e g l o b e , a n d o f m a n y d i s c i p l i n e s -

linguists, anthropologists, geographers and botanists, for example,

as w e l l as h i s t o r i a n s a n d a r c h a e o l o g i s t s .

It w a s t h o u g h t t h a t t h e g r e a t e s t p r o b l e m s w e r e l i k e l y t o a r i s e

w i t h the earliest a n d latest p e r i o d s : the earliest, b e c a u s e s o m u c h

w o u l d d e p e n d o n the results o f l o n g - t e r m a r c h a e o l o g i c a l investi

g a t i o n , a n d t h e latest, b e c a u s e o f the rapid c h a n g e s in historical

p e r s p e c t i v e that w e r e o c c u r r i n g as a c o n s e q u e n c e o f t h e e n d i n g

o f c o l o n i a l rule in Africa. T h e r e f o r e w h e n , in 1967, the general

editors presented their s c h e m e t o the Press a n d notes w e r e

prepared for contributors, only four v o l u m e s - c o v e r i n g the

p e r i o d s 500 B.C. t o A . D . 1 0 5 0 , A . D . 1 0 5 0 t o 1 6 0 0 , 1600—1790, a n d

1 7 9 0 - 1 8 70 - h a d b e e n p l a n n e d i n a n y d e t a i l , a n d t h e s e w e r e

p u b l i s h e d as v o l u m e s 2 - 5 o f t h e History b e t w e e n 1 9 7 5 a n d 1 9 7 8 .

S o far as t h e p r e h i s t o r i c p e r i o d w a s c o n c e r n e d , t h e g e n e r a l

editors w e r e clear f r o m the outset that the p r o p e r course w a s t o

e n t r u s t t h e p l a n n i n g as w e l l as t h e a c t u a l e d i t i n g o f w h a t w a s

necessary entirely t o a scholar w h o w a s fully e x p e r i e n c e d in the

archaeology o f the African continent. In d u e course, in 1982,

V o l u m e 1, ' F r o m t h e e a r l i e s t t i m e s t o c. 500 B . C . a p p e a r e d u n d e r

t h e d i s t i n g u i s h e d e d i t o r s h i p o f P r o f e s s o r J. D e s m o n d C l a r k . A s

f o r t h e c o l o n i a l p e r i o d , it w a s e v i d e n t b y t h e e a r l y 1 9 7 0 s t h a t t h i s

w a s b e i n g r a p i d l y b r o u g h t t o i t s c l o s e , s o t h a t it b e c a m e p o s s i b l e

t o p l a n t o c o m p l e t e t h e History i n t h r e e f u r t h e r v o l u m e s . T h e first,

V o l u m e 6, is d e s i g n e d t o c o v e r t h e E u r o p e a n p a r t i t i o n o f t h e

xiv

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

PREFACE

continent, and the setting up o f the colonial structures b e t w e e n

c. 1 8 7 0 a n d c. 1 9 0 5 ; t h e s e c o n d , V o l u m e 7, is d e v o t e d t o t h e

' c l a s s i c a l ' c o l o n i a l p e r i o d r u n n i n g f r o m c. 1905 t o c. 1 9 4 0 ; w h i l e

t h e f o c u s o f t h e t h i r d , V o l u m e 8, is o n t h e p e r i o d o f r a p i d c h a n g e

w h i c h led f r o m a b o u t the time o f the S e c o n d W o r l d W a r t o the

e n d i n g o f f o r m a l c o n t r o l f r o m E u r o p e w i t h t h e d r a m a t i c final

c o l l a p s e o f t h e P o r t u g u e s e e m p i r e in 1 9 7 5 .

W h e n they started their w o r k , the g e n e r a l editors q u i c k l y c a m e

to the c o n c l u s i o n that the m o s t practical plan for c o m p l e t i n g the

History w i t h i n a r e a s o n a b l e p e r i o d o f t i m e w a s l i k e l y t o b e t h e

simplest and most straightforward. E a c h v o l u m e w a s therefore

entrusted to a v o l u m e editor w h o , in addition t o h a v i n g m a d e a

substantial c o n t r i b u t i o n to the u n d e r s t a n d i n g o f the p e r i o d in

question, w a s s o m e o n e w i t h w h o m the g e n e r a l editors w e r e in

close t o u c h . W i t h i n a v o l u m e , the aim w a s to k e e p the n u m b e r

o f contributors to a m i n i m u m . E a c h o f t h e m w a s asked to essay

a b r o a d s u r v e y o f a particular area o r t h e m e w i t h w h i c h h e w a s

familiar for the w h o l e o f the p e r i o d c o v e r e d b y the v o l u m e . In

this s u r v e y , h i s p u r p o s e s h o u l d b e t o t a k e a c c o u n t n o t o n l y o f all

r e l e v a n t r e s e a r c h d o n e , o r still i n p r o g r e s s , b u t a l s o o f t h e g a p s

in k n o w l e d g e . T h e s e h e s h o u l d t r y t o fill b y n e w t h i n k i n g o f h i s

o w n , w h e t h e r based o n n e w w o r k o n the available sources o r o n

interpolations from c o n g r u e n t research.

It s h o u l d b e r e m e m b e r e d t h a t t h i s b a s i c p l a n w a s d e v i s e d

n e a r l y t w e n t y y e a r s a g o , w h e n little o r n o r e s e a r c h h a d b e e n d o n e

on many important topics, and before many o f today's y o u n g e r

s c h o l a r s - n o t least t h o s e w h o n o w fill p o s t s i n t h e d e p a r t m e n t s

o f history and a r c h a e o l o g y in the universities a n d research

institutes in A f r i c a itself - h a d m a d e their o w n d e e p p e n e t r a t i o n s

into s u c h areas o f i g n o r a n c e . T w o t h i n g s f o l l o w f r o m this. I f the

general editors had d r a w n u p their plan in the 1970s rather than

the 1960s, the shape m i g h t w e l l h a v e b e e n v e r y different, p e r h a p s

with a larger n u m b e r o f m o r e specialised, shorter chapters, each

centred o n a smaller area, p e r i o d o r t h e m e , t o the u n d e r s t a n d i n g

o f w h i c h the c o n t r i b u t o r w o u l d h a v e m a d e his o w n i n d i v i d u a l

c o n t r i b u t i o n . T o s o m e e x t e n t , i n d e e d , it h a s b e e n p o s s i b l e t o

adjust t h e s h a p e o f t h e last t h r e e v o l u m e s i n t h i s d i r e c t i o n .

S e c o n d l y , the sheer v o l u m e o f n e w research that has b e e n

published since m a n y contributors accepted their c o m m i s s i o n s

has o f t e n l e d t h e m t o u n d e r t a k e v e r y s u b s t a n t i a l r e v i s i o n s i n t h e i r

xv

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

PREFACE

w o r k as it p r o g r e s s e d f r o m d r a f t t o d r a f t , t h u s p r o t r a c t i n g t h e

length o f time originally e n v i s a g e d for the preparation o f these

volumes.

A t the time w h e n the plan for V o l u m e 8 w a s settled, 1975

s e e m e d an ideal c l o s i n g date. F o r the reason w h i c h has already

b e e n m e n t i o n e d , it still is a v e r y s e n s i b l e d a t e . B u t h i s t o r y d o e s

n o t s t o p at t h e p o i n t s w h e r e its r e c o r d e r s a n d i n t e r p r e t e r s c h o o s e

to d r a w their lines and, in the n o t i n c o n s i d e r a b l e space o f time

in w h i c h V o l u m e 8 w a s b e i n g w r i t t e n a n d p u t t o g e t h e r , it w a s

inevitable that a n u m b e r o f events s h o u l d o c c u r w h i c h m i g h t be

t h o u g h t w o r t h y o f m e n t i o n . S o m e o f t h e s e h a v e fitted n i c e l y i n t o

the w a y s o m e c o n t r i b u t o r s c h o s e to organise their chapters ; s o m e

h a v e not. Inevitably, therefore, the c o n c l u d i n g line o f the v o l u m e

as a w h o l e h a s b e c o m e s o m e w h a t r a g g e d . S e c o n d l y , n o t all

historians are w i l l i n g t o w r i t e s o c l o s e t o the c h r o n o l o g i c a l

f r o n t i e r o f t h e i r d i s c i p l i n e as t h i s v o l u m e a i m s t o g o . Its e d i t o r

has therefore perforce s o m e t i m e s had to seek c o n t r i b u t i o n s from

s c h o l a r s w h o s e d i s c i p l i n e is less h i s t o r y t h a n p o l i t i c a l s c i e n c e o r

e c o n o m i c s . T h e discerning reader will therefore recognise s o m e

differences o f a c a d e m i c a p p r o a c h b e t w e e n chapters.

H o w e v e r , histories are m e a n t to b e read, a n d n o t t o b e

c o m m e n t e d o n and analysed b y their general editors, and w e

therefore present t o the reader this c o n c l u d i n g v o l u m e o f o u r

enterprise.

March 1984 J. D. F A G E

ROLAND OLIVER

M a n y p e o p l e h a v e assisted the E d i t o r in the p r o d u c t i o n o f this

volume. He would particularly like to express his debt to

Professor Lalage Bown, Professor Robert Gavin, Dr Lome

Larson, Professor R o b i n H o r t o n , and D r Philip Shea.

xvi

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

INTRODUCTION

W h e t h e r the Second W o r l d W a r marked a decisive stage in the

colonial history o f Africa, unleashing forces that, w i t h hindsight,

w e c a n see m a d e political d e c o l o n i s a t i o n b y e v e n the m o s t

r e l u c t a n t o f E u r o p e a n p o w e r s i n e v i t a b l e , o r w h e t h e r it m e r e l y

hastened a process that w a s already, if n o t v e r y o b v i o u s l y , u n d e r

w a y , w i l l l o n g r e m a i n a m a t t e r f o r d e b a t e . T h e r e is m u c h t o b e

said f o r b o t h v i e w s . W h a t is c l e a r is t h a t n e a r l y a l l w r i t e r s o n t h e

c o l o n i a l p e r i o d o f A f r i c a ' s p a s t a c c e p t , o r a t least p a y l i p s e r v i c e

to, the v i e w that for w h a t e v e r reason the S e c o n d W o r l d W a r

represented a watershed in the history o f the continent. Y e t

c u r i o u s l y f e w o f t h e m g i v e its c o u r s e o r i m p a c t detailed attention.

It is as t h o u g h it w e r e a n i n t e r v a l b e t w e e n t h e t w o a c t s o f a p l a y

in w h i c h t h e a u d i e n c e is a s k e d t o a c c e p t t h a t t h e r e h a s b e e n a

p a s s a g e o f t i m e b u t is g i v e n o n l y t h e b a r e s t o u t l i n e o f w h a t h a s

happened meanwhile.

T h e r e are m a n y serious studies of, o n the o n e h a n d , the years

1 9 1 9 - 1 9 3 9 - the p e r i o d o f classic colonial r u l e - a n d , o n the

other, the years immediately f o l l o w i n g the w a r - the period o f

' d e c o l o n i s a t i o n ' o r ' t h e transfer o f p o w e r ' . F e w historians h a v e

interested t h e m s e l v e s in b o t h p e r i o d s , a n d the latter p e r i o d has

m o s t l y b e e n left t o t h e a t t e n t i o n o f p o l i t i c a l s c i e n t i s t s . C o n v e r s e l y ,

few political scientists h a v e paid m u c h attention t o the years

before 1945. T h e Second W o r l d W a r seems t o represent a

b o u n d a r y b e t w e e n w h a t is r e g a r d e d as t h e p r o p e r t e r r i t o r y o f t h e

h i s t o r i a n a n d w h a t is t h e p r o v i n c e o f t h e p o l i t i c a l s c i e n t i s t o r

j o u r n a l i s t . M o s t h i s t o r i a n s a p p a r e n t l y feel r e l u c t a n t t o b r i n g t h e

tools o f their trade t o bear o n a period in w h i c h the chief actors

are still p r a c t i s i n g t h e i r p r o f e s s i o n , a n d f o r w h i c h t h e a r c h i v a l

e v i d e n c e h a s , f o r t h e g r e a t e r p a r t o f it, n o t y e t b e e n r e l e a s e d . T h e y

prefer t o let political scientists h a z a r d j u d g e m e n t s w h i c h t h e y fear

w i l l fail t h e test o f t i m e .

S i n c e The Cambridge History of Africa sets o u t t o b e a n e n d u r i n g

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

INTRODUCTION

historical survey, there m i g h t , therefore, seem to be a case for

a c c e p t i n g t h e S e c o n d W o r l d W a r as a t e r m i n a l e v e n t f o r t h e

e n t e r p r i s e . A t least f o r m a n y o f t h e c o u n t r i e s t h a t o n c e r u l e d

A f r i c a , t h e a r c h i v e s are o p e n f o r m o s t o f t h e p e r i o d t h a t p r e c e d e d

t h a t w a r , t h o u g h s o m e still m a i n t a i n t h e 50-year r u l e . A s a r e s u l t

it w i l l o n l y b e in 1 9 9 0 t h a t w e s h a l l l e a r n t h e i n n e r m o s t s e c r e t s

o f s o m e o f the c o l o n i s e r s for the year 1940, the date w i t h w h i c h

this p r e s e n t v o l u m e b e g i n s .

Inevitably a v o l u m e that takes the history o f Africa u p to 1 9 7 5 ,

a n d t h e c h a p t e r s o f w h i c h w e r e in s o m e c a s e s w r i t t e n as e a r l y as

1977 by those martyrs o f collective enterprises - the p r o m p t

deliverers - d o e s n o t h a v e the a d v a n t a g e o f p e r s p e c t i v e that e v e n

t h e p r e c e d i n g v o l u m e , c o v e r i n g t h e c o l o n i a l p e r i o d f r o m 1905 till

1940, can h a v e . M u c h o f the e v i d e n c e m u s t o f necessity be

s e c o n d a r y o r , w h e r e it is p r i m a r y , t h e r e s u l t o f t h e d i r e c t

experience o f the contributor, using evidence assimilated from day

to day in n e w s p a p e r s , c o n v e r s a t i o n o r i n t e r v i e w s .

A m o r e cautious scheme for a history o f Africa w o u l d , then,

h a v e h a d its last v o l u m e c o n c l u d e w i t h t h e S e c o n d W o r l d W a r .

B u t that w o u l d h a v e been to leave the story w i t h o u t an e n d i n g .

T h e S e c o n d W o r l d W a r m a y h a v e b e e n a w a t e r s h e d in A f r i c a n

h i s t o r y , b u t it w a s m o r e in t h e n a t u r e o f a t u r n i n g p o i n t w i t h i n

a p e r i o d than the e n d i n g o f o n e o r the b e g i n n i n g o f another.

W h e t h e r t h e w a r is s e e n as h a v i n g u n l e a s h e d n e w f o r c e s o r m e r e l y

4 1

as h a v i n g s t i m u l a t e d a n d g i v e n s c o p e t o f o r c e s a l r e a d y at p l a y ' ,

it d i d c h a n g e t h e s i t u a t i o n s o r a d i c a l l y i n A f r i c a t h a t t h e

c o n c l u s i o n o f the c h a n g e has to be seen if the significance o f the

w a r is t o b e u n d e r s t o o d . I n d e e d , o n e o f t h e G e n e r a l E d i t o r s o f

The Cambridge History of Africa o n c e c r i t i c i s e d t h e w r i t e r f o r

t e r m i n a t i n g h i s West Africa under Colonial Rule i n 1 9 4 5 , ' t h u s

2

e x c l u d i n g the m o s t d e t e r m i n i n g part o f the colonial p e r i o d \ T h a t

w a s o f c o u r s e the d i s m a n t l i n g o f the E u r o p e a n e m p i r e s in the

g r e a t e r p a r t o f N o r t h a n d W e s t A f r i c a b y i 9 6 0 , a n d t h e rest o f t h e

continent by 1975.

In 1940 the v a s t majority o f the inhabitants o f the c o n t i n e n t

w e r e under one f o r m or another o f E u r o p e a n colonial rule. O f

the three countries that w e r e n o m i n a l l y i n d e p e n d e n t , L i b e r i a w a s

enfeoffed to the F i r e s t o n e R u b b e r C o m p a n y o f the U n i t e d States,

E g y p t w a s s e v e r e l y l i m i t e d in t h e e x e r c i s e o f h e r s o v e r e i g n t y b y

1 2

See Chapter 8. Roland Oliver in The Observer, n August 1968.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

INTRODUCTION

SPANISH MOROCCO^

^FRENCHWEST AFRICA; „J A N G L O -

^GAÒBÌA^ y/' EGYPTIAN

SUDAN

|NÏGERÏA|

SIERRA^ :::|TALIAN :

LEONE - E A S T AFRICA::

SStP /rernandoPoISploK

oua&i/ C A M E R O O N S ^

r

T O G O L A N O (Br.&Fr.mandates) J

(Br. &Fr. mandates) SaoTom6»

& Principe*

BELGIAN -RUANDA-

IICONGC URUNDI

'//AV/A'//'

• ' , * f ( B e l g i a n

^TANGANYIKA

,

NYASALAND

(Mandated to Union

of South Africa)^

Portuguese

^British SWAZILAND

BASUTOLANO

British mandate

French

French mandate

Belgian

E Belgian mandate

• Spanish

2000km

EÏÏ3 Italian

IBoOrt

i Africa, 1940.

the terms o f the A n g l o - E g y p t i a n T r e a t y o f 1936, w h i l e indepen

dence in the U n i o n o f S o u t h Africa w a s meaningful o n l y for the

white minority w h i c h h a d already embarked o n a p r o g r a m m e o f

stripping the non-white majority o f the f e w political a n d social

r i g h t s it d i d p o s s e s s . I n d e e d , w h i l e m o s t o t h e r b l a c k A f r i c a n s

d u r i n g o u r period w e r e t o i m p r o v e their political position, those

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

INTRODUCTION

o f S o u t h A f r i c a w e r e t o suffer a c o n c o m i t a n t d e t e r i o r a t i o n in

theirs.

O n the e v e o f the S e c o n d W o r l d W a r f e w , if any, E u r o p e a n s

or Africans e n v i s a g e d that w i t h i n t w o decades well o v e r half o f

t h e p o p u l a t i o n o f t h e c o n t i n e n t w o u l d b e free f r o m c o l o n i a l

tutelage. D e s p i t e the d e v o l u t i o n o f p o w e r in the major A s i a n

d e p e n d e n c i e s , t h e B r i t i s h g o v e r n m e n t d i d n o t y e t t h i n k it n e c e s s a r y

to a p p l y that e x p e r i e n c e t o A f r i c a . B y 1940 C e y l o n h a d for l o n g

had internal s e l f - g o v e r n m e n t , w h i l e in India the British had

already d e v o l v e d a great deal o f the business o f g o v e r n m e n t o n

I n d i a n s , r e t a i n i n g e x c l u s i v e c o n t r o l o n l y o v e r e x t e r n a l affairs a n d

defence. A l t h o u g h the British L a b o u r Party had independence for

I n d i a o n its p r o g r a m m e , as far as t h e A f r i c a n c o l o n i e s w e r e

c o n c e r n e d it c o n s i d e r e d s e l f - g o v e r n m e n t , l e t a l o n e i n d e p e n d e n c e ,

a remote prospect. M a l c o l m M a c D o n a l d , L a b o u r Colonial Sec

r e t a r y in t h e B r i t i s h N a t i o n a l g o v e r n m e n t , p u t t h e B r i t i s h v i e w o n

political d e v e l o p m e n t in the A f r i c a n c o l o n i e s t o the H o u s e o f

C o m m o n s o n 7 D e c e m b e r 1938: 'It may take generations, or e v e n

centuries, for the p e o p l e s in s o m e parts o f the c o l o n i a l e m p i r e

t o a c h i e v e s e l f - g o v e r n m e n t . B u t it is a m a j o r p a r t o f o u r p o l i c y ,

e v e n a m o n g the m o s t b a c k w a r d peoples o f Africa, to teach t h e m

1

a l w a y s t o b e a b l e t o s t a n d a little m o r e o n t h e i r o w n f e e t . ' T h e

Popular Front g o v e r n m e n t o f France had been n o more daring

in its t h i n k i n g a b o u t p o l i t i c a l d e v e l o p m e n t i n A f r i c a , a n d t h e f e w

r e f o r m s it h a d b e e n a b l e t o i n t r o d u c e w e r e b a s i c a l l y a s s i m i l a t i o n i s t

in i n t e n t , w h i l e t h e B e l g i a n s , S p a n i s h , P o r t u g u e s e a n d I t a l i a n s d i d

n o t g i v e the subject a passing t h o u g h t .

Far from decolonisation b e i n g a theme o f these times, a n e w

i m p e r i a l i s m w a s i n t h e E u r o p e a n air. I t a l y h a d j u s t i n v a d e d

E t h i o p i a a n d i n c o r p o r a t e d it i n t o h e r E a s t A f r i c a n e m p i r e . T h e

L e a g u e o f N a t i o n s , w h i c h had earlier v o t e d e c o n o m i c sanctions

a g a i n s t I t a l y i n t h e h o p e o f h a l t i n g h e r i n v a s i o n , o n c e it w a s

successful w i t h d r e w t h e m , t u r n i n g a d e a f if e m b a r r a s s e d ear t o

the personal appeal by E m p e r o r Haile Selassie for i n t e r v e n t i o n

o n h i s c o u n t r y ' s b e h a l f . G e r m a n y , still s m a r t i n g u n d e r t h e

humiliation o f the T r e a t y o f Versailles w h i c h had stripped her o f

her colonial empire, thrilled to Hitler's d e m a n d s that the c o u n t r y

r e g a i n its ' r i g h t f u l p l a c e i n t h e t r o p i c a l s u n ' . E v e n in S p a i n t h e r e

1

Hansard^ 7 December 1938.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

INTRODUCTION

w e r e expansionists w h o d r e a m e d d u r i n g the w a r o f creating an

1

e m p i r e taken from N i g e r i a and F r e n c h E q u a t o r i a l A f r i c a .

N o t only was imperialism very m u c h alive, but few Europeans

questioned their right to p o s s e s s i o n o f c o l o n i e s . C o n v e r s e l y , the

majority o f Africans had c o m e to accept the E u r o p e a n presence,

if o n l y passively. N o t a f e w o f the educated élite shared the v i e w

o f Isaac D e l a n o w h o w r o t e in 1 9 3 7 : ' T h e p e o p l e o f N i g e r i a are

very p r o u d o f the British E m p i r e to w h i c h they b e l o n g , and o f

British statesmanship and equity. T h e y realise that they c a n n o t

safely b e c o m e i n d e p e n d e n t o f t h e B r i t i s h G o v e r n m e n t as t h i n g s

2

are t o d a y i n t h e w o r l d . ' S o m e o f t h e w e s t e r n - e d u c a t e d m i n o r i t y

had, h o w e v e r , b e g u n to articulate q u e s t i o n s c o u c h e d in terms o f

western political t h o u g h t a b o u t the presence o f the E u r o p e a n s and

their right to g o v e r n c o l o n i a l p e o p l e s in an autocratic fashion.

T h u s for L a m i n e G u è y e , w h o f o u n d e d the Parti Socialiste

S é n é g a l a i s i n 1 9 3 5 , it w a s i r o n i c t h a t t h e s a m e c o l o n i a l p o w e r

w h i c h i m p o s e d t h e corvée o n its A f r i c a n s u b j e c t s p l a c e d i n t h e

h a n d s o f t h e i r c h i l d r e n at s c h o o l b o o k s p r o c l a i m i n g t h a t t h e

' c o l o n i e s w e r e an i n t e g r a l p a r t o f t h e v e r y R e p u b l i c w h o s e

founders had d i s c o v e r e d and t a u g h t that " m e n are b o r n and

r e m a i n f r e e " a n d w h i c h h a d as its m o t t o " L i b e r t y - E q u a l i t y -

3

F r a t e r n i t y " \ W h i l e the majority o f the e d u c a t e d élite limited

their d e m a n d s to s o m e f o r m o f participation in the institutions

o f g o v e r n m e n t i m p o s e d o n t h e m b y their colonial masters, w i t h

the v a r i o u s y o u t h m o v e m e n t s in W e s t A f r i c a d e m a n d i n g that this

participation be g r a n t e d m o r e s p e e d i l y , a m i n o r i t y in F r e n c h

N o r t h Africa w a s b e g i n n i n g to m a k e o v e r t d e m a n d s for an early

and c o m p l e t e i n d e p e n d e n c e that w a s n o t tied to s o m e f o r m o f

constitutional association w i t h F r a n c e . E v e n s o , in the year before

the o u t b r e a k o f the S e c o n d W o r l d W a r the E u r o p e a n imperial

p o w e r s had g o o d reason to be c o m p l a c e n t a b o u t their l o n g - t e r m

p o s i t i o n in A f r i c a . Y e t w i t h i n t w o years o f the o p e n i n g o f

h o s t i l i t i e s i n E u r o p e E t h i o p i a h a d r e g a i n e d its s o v e r e i g n t y , a n d

a d e c a d e later L i b y a b e c a m e i n d e p e n d e n t . W i t h i n a n o t h e r 2 5 years

t h e last m a j o r E u r o p e a n c o l o n y i n A f r i c a , A n g o l a , h a d g a i n e d its

independence o n 11 N o v e m b e r 1 9 7 5 , and the dismantling o f the

1

René Pélissier, 'Equatorial Guinea: recent history', in Africa: South of the Sahara,

1977-78 ( L o n d o n , 1977), 301.

2

I. O . Delano, The soul of Nigeria ( L o n d o n , 1937), 8.

3

Lamine G u è y e , Itinéraire africaine (Paris, 1966), 79.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

INTRODUCTION

0

0

Madeira

Ceuta ( S p l

-tè

(Port) • /TUNISIA

Canary Is

<Sp)*„. s

v

* go

ALGERIA

SPANISH j LIBYA EGYPT

SAHARA

{MAURITANIA French territory of

AFARS & ISSAS

MALI NIGER

CHAD SUDAN

UPPER

VOLTA y

12/ N I G E R I A

J? SIERRr- ' I V O R Y 1^ ETHIOPIA

COAST/* 'CENTRAL

£ LEONE ^AFRICAN REP.

3 LIBERIA" TOGO

SàoTomé.

F

& Principe« ZAIRE KENYA

(ind 1975) /

EQUATORIAL RWANDA/

C a p e Verde Is. GUINEA BURUNDlt

(ind. 1975)

A TANZANIA^

ANGOLA

ZAMBIA

.RHODESIA? ^»

iG>V

\NAMIBIA (ZÌMBABWEy^r^ MADAGASCAR

BOTSWANA/*"^ ^

:SOUTH-

V WEST

VAFRICA

SWAZILAND

I Areas still under colonial rule SOUTH o

Mauritius Û

AFRICA /"LESOTHO

] U N Trust Territory under Reunion(Fr)

illegal South African rule

I Illegal independence from

Britain declared by white

minority government in 1965

Partitioned between Morocco

2000 km

and Mauritania, Nov. 1975

10*00 miles

2 Africa, 1975.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

INTRODUCTION

E u r o p e a n e m p i r e s in A f r i c a w a s c o m p l e t e e x c e p t for a f e w e x o t i c

enclaves and offshore islands. T h e r e w e r e , o f course, three major

t e r r i t o r i e s i n w h i c h A f r i c a n s w e r e still s u b j e c t t o c o n t r o l b y p e o p l e

o f E u r o p e a n origin but w h i c h n o l o n g e r formed part o f any

E u r o p e a n i m p e r i u m . T h e w h i t e m i n o r i t y in the R e p u b l i c o f S o u t h

A f r i c a h a d g a i n e d v i r t u a l i n d e p e n d e n c e f r o m B r i t a i n as l o n g a g o

as 1 9 1 0 . T h e f o r m e r G e r m a n c o l o n y o f S o u t h W e s t A f r i c a h a d

b e e n m a n d a t e d t o S o u t h A f r i c a after t h e F i r s t W o r l d W a r . I n

R h o d e s i a the w h i t e minority had unilaterally and effectively taken

its i n d e p e n d e n c e f r o m B r i t a i n i n 1965 s o as t o a v o i d a n y q u e s t i o n

o f effective A f r i c a n p a r t i c i p a t i o n in the political p r o c e s s o f their

c o u n t r y , let a l o n e s u b j e c t i o n t o A f r i c a n m a j o r i t y r u l e , w h i c h w a s

a prerequisite o f the legal g r a n t i n g o f i n d e p e n d e n c e b y the m o t h e r

country.

T h e political, social and e c o n o m i c c o n s e q u e n c e s o f this rapid

collapse o f the E u r o p e a n c o l o n i a l e m p i r e s in A f r i c a b e t w e e n 1940

a n d 1 9 7 5 f o r m t h e c e n t r a l t h e m e o f t h i s v o l u m e . T h e first c h a p t e r

will seek to assess the role o f the S e c o n d W o r l d W a r in that

collapse.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

C H A P T E R 1

THE S E C O N D W O R L D WAR: PRELUDE

T O D E C O L O N I S A T I O N IN AFRICA

B y 1 9 3 9 t h e E u r o p e a n c o l o n i a l p o w e r s w e r e as firmly i n c o n t r o l

o f t h e i r A f r i c a n t e r r i t o r i e s as t h e y e v e r w o u l d b e . D u r i n g t h e

p r e c e d i n g ten years there had been f e w major challenges to their

authority. Africans had c o m e to accept the n e w political order and

to o b e y the rules laid d o w n b y the c o l o n i a l administration. T h e

lesson had been learned that, a l t h o u g h the colonial administration

w a s t h i n o n t h e g r o u n d , i n t h e last r e s o r t it h a d o v e r w h e l m i n g

resources o f p o w e r . A t t e m p t s to take a d v a n t a g e o f the w e a k n e s s

o f s o m e colonial administrations d u r i n g the First W o r l d W a r and

to return to an i n d e p e n d e n c e based o n pre-colonial political

structures, t h o u g h t e m p o r a r i l y successful, had failed. S u c h chal

l e n g e s t o t h e c o l o n i a l a u t h o r i t i e s as d i d t a k e p l a c e d u r i n g t h e 1 9 3 0 s

w e r e m a d e w i t h i n the f r a m e w o r k o f the c o l o n i a l state and w e r e

b y and large limited to protest against o b n o x i o u s features o f the

administration; such protest t o o k the f o r m o f riots against

taxation o r strikes to obtain h i g h e r w a g e s or better conditions o f

s e r v i c e in the small c o l o n i a l industrial sector. W i t h the n o t a b l e

exception o f French N o r t h Africa, there w e r e few violent d e m o n

s t r a t i o n s o f a m o d e r n p o l i t i c a l c h a r a c t e r , t h a t i s , a i m e d at

securing greater participation b y Africans, and m o r e specifically

the small e d u c a t e d élite, in the g o v e r n m e n t a l processes o f the

c o l o n i a l state. N e v e r t h e l e s s it w a s c l e a r t h a t i f t h e e d u c a t e d é l i t e

a c c e p t e d t h e s t a t u s q u o it w a s a p a s s i v e n o t a n a c t i v e a c c e p t a n c e :

t h e y h a n k e r e d after a n i n d e p e n d e n c e , b u t , l i k e t h e B r i t i s h , t h e y

s a w it as a g o a l w h o s e r e a l i s a t i o n w a s d i s t a n t . Y e t w h e n t h e y s a w

t h e o n e t r u l y i n d e p e n d e n t s t a t e o f E t h i o p i a fall t o c o l o n i a l i s t

forces in 1936, their reaction w a s o n e o f w i d e - s c a l e protest.

B y 1 9 3 9 t h e i m p o s e d c o l o n i a l states h a d g a i n e d l e g i t i m a c y i n

the eyes o f their inhabitants, particularly a m o n g the e d u c a t e d

elites, w h o n o w identified their political and social a m b i t i o n s w i t h

them. T h i s did not m e a n that they had a b a n d o n e d their pre-colonial

identities ; yet that part o f the legacy o f colonial rule that w a s called

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

PRELUDE TO DECOLONISATION

less i n t o q u e s t i o n t h a n a n y o t h e r b y t h e n a t i o n a l i s t s w a s t h e

f r a m e w o r k o f states s u p e r i m p o s e d o n t h e p r e - c o l o n i a l p o l i t i e s b y

t h e i n v a d i n g E u r o p e a n p o w e r s at t h e e n d o f t h e n i n e t e e n t h

c e n t u r y . It w a s m o r e t h e c o u n t r y - f o l k , p a r t i c u l a r l y t h o s e w h o s e

lands had b e e n arbitrarily split b y the n e w E u r o p e a n c o l o n i a l

frontiers, w h o tended to operate socially and e v e n politically in

terms o f their pre-colonial structures.

O n t h e e v e o f t h e S e c o n d W o r l d W a r , t h e n , t h e Pax Europaea

w a s f i r m l y e s t a b l i s h e d i n A f r i c a . A t o n e l e v e l it w a s a s e e m i n g l y

very tenuous peace, dependent on a handful o f E u r o p e a n admini

strators ruling o v e r vast and p o p u l o u s areas w i t h o n l y a handful

o f A f r i c a n s o l d i e r s o r p a r a - m i l i t a r y p o l i c e at t h e i r d i s p o s a l .

N i g e r i a , f o r e x a m p l e , h a d o n l y s o m e 4000 s o l d i e r s a n d 4000 p o l i c e

in 1 9 3 0 , o f w h o m all b u t a b o u t 75 i n e a c h f o r c e w e r e b l a c k . J u s t

h o w thin o n the g r o u n d the E u r o p e a n administrations w e r e can

b e s e e n f r o m t h e fact t h a t i n N i g e r i a i n t h e l a t e 1 9 3 0 s t h e n u m b e r

o f a d m i n i s t r a t o r s f o r a p o p u l a t i o n e s t i m a t e d at 20 m i l l i o n w a s o n l y

386, a r a t i o o f 1 : 5 4 0 0 0 , a n d t h a t i n c l u d e d t h o s e i n t h e s e c r e t a r i a t .

In the B e l g i a n C o n g o the ratio w a s 1: 34800 and in F r e n c h W e s t

A f r i c a 1 : 2 7 500. It s h o u l d n o t b e f o r g o t t e n , t o o , t h a t i n p a r t s o f

t h e E u r o p e a n c o l o n i a l e m p i r e t h e c o l o n i a l i m p r i n t w a s still v e r y

light. M a n y Africans had never personally seen a w h i t e man, w h i l e

in M o z a m b i q u e p a r t s o f t h e t e r r i t o r y w e r e n o t e v e n a d m i n i s t e r e d

b y the g o v e r n m e n t , b u t b y c o n c e s s i o n c o m p a n i e s .

T h e Pax Europaea e s t a b l i s h e d b y t h e e n d o f t h e 1 9 3 0 s w a s , o f

course, vital to the successful and intensive exploitation o f the

c o l o n i a l estate b y m e t r o p o l i t a n capital. A n d b y the 1930s the

pre-colonial e c o n o m i c structure o f Africa had been remodelled

i n t o a series o f c o l o n i a l e c o n o m i e s w h o s e c o m m o n characteristic,

w h a t e v e r the nationality o f their administration, w a s that they

w e r e p r o d u c e r s o f foodstuffs and raw materials for c o n s u m p t i o n

o r p r o c e s s i n g b y t h e m e t r o p o l i t a n a n d r e l a t e d e c o n o m i e s ; in t u r n

t h e y s e r v e d as m a r k e t s f o r t h e m a n u f a c t u r e d g o o d s o f E u r o p e a n

industry, m a n y o f them, like soap, processed from r a w materials

exported b y these v e r y colonial e c o n o m i e s . T h e infrastructural

pattern o f the A f r i c a n c o l o n i e s reflected clearly this f u n c t i o n .

R a i l w a y s and roads w e r e built primarily to link m i n e s o r areas o f

e x p o r t - c r o p p r o d u c t i o n w i t h the coast; few w e r e built to link o n e

centre o f p r o d u c t i o n o f crops o r g o o d s for internal c o n s u m p t i o n

with another. T h e colonial administrations were handmaidens to

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

PRELUDE TO DECOLONISATION

this e x p l o i t a t i o n , differing o n l y in the d e g r e e o f a c t i v e assistance

t h e y g a v e in t e r m s o f t a x a t i o n , f o r c e d l a b o u r o r c o m p u l s o r y c r o p

cultivation, and the extent to w h i c h they tried to protect the

interests o f their c o l o n i a l subjects. W h e r e p r i v a t e capital w a s

u n w i l l i n g t o p r o v i d e t h e i n f r a s t r u c t u r a l s e r v i c e s it s u p p l i e d in

E u r o p e , s u c h as e l e c t r i c a l p o w e r , r a i l w a y s a n d p o r t s , t h e c o l o n i a l

g o v e r n m e n t s raised the necessary funds for their establishment

f r o m the c o l o n i a l b u d g e t either t h r o u g h taxation o r loans. In

short, b y 1939 Africa had been integrated b y c o l o n i a l rule into

the E u r o p e a n capitalistic s y s t e m and in turn had been i m p r e g n a t e d

w i t h the capitalistic structure o f the m e t r o p o l e , and s u c h d e v e l

o p m e n t that t o o k place w a s m a i n l y in t h o s e sectors p r o d u c i n g for

1

the e x p o r t and i m p o r t trade. A n y d e v e l o p m e n t o f the internal

e x c h a n g e e c o n o m y that resulted w a s largely co-incidental.

T h e extent and intensity o f the incorporation o f the African

e c o n o m y into the w o r l d capitalist system b y 1939 varied f r o m

colony to c o l o n y and from region to region within individual

c o l o n i e s . T h i s p r o c e s s h a d b e g u n as e a r l y as t h e e i g h t e e n t h

c e n t u r y , b u t u n t i l t h e E u r o p e a n o c c u p a t i o n it affected p r i n c i p a l l y

t h o s e areas o n the coast w i t h w h i c h trade h a d already b e e n o p e n e d

u p . T h e r e s u l t o f c o l o n i a l o c c u p a t i o n w a s t o i n v o l v e all A f r i c a n s ,

h o w e v e r indirectly, in the w o r l d e c o n o m y . T h e directness o f their

i n v o l v e m e n t w a s , o f course, determined b y the resources o f the

locality they l i v e d in. B y the b e g i n n i n g o f o u r p e r i o d the m o s t in

t e n s i v e l y i n v o l v e d w e r e t h e p r o d u c e r s o f c r o p s s u c h as g r o u n d

n u t s , p a l m - o i l , c o t t o n , c o c o a , cofTee a n d sisal f o r w h i c h t h e r e

was a demand overseas. T h e s e crops had c o m e to be produced

i n t h r e e d i s t i n c t w a y s w h i c h w e r e t o h a v e i m p o r t a n t effects o n t h e

c o u r s e o f t h e d e v e l o p m e n t o f A f r i c a n n a t i o n a l i s m . T h e first,

p r e d o m i n a n t in W e s t A f r i c a , b u t a l s o t o b e f o u n d i n t h e M a g h r i b ,

E g y p t and U g a n d a , w a s t h r o u g h the a g e n c y o f peasant farmers.

T h e s e c o n d , p r e d o m i n a n t in E q u a t o r i a l A f r i c a and in parts o f

Central and southern Africa, w a s t h r o u g h c o m p a n y - o w n e d

plantations using w a g e a n d / o r forced labour. T h e third w a s

t h r o u g h farms run b y w h i t e settlers u s i n g A f r i c a n w a g e - l a b o u r .

Irrespective o f nationality, the character o f individual colonial

administrations w a s deeply influenced b y the m o d e s o f agricultural

p r o d u c t i o n t o b e f o u n d in t h e i r t e r r i t o r i e s . T h u s B r i t i s h a d m i n -

1

See the i n t r o d u c t i o n ' to Peter C . W . G u t k i n d and Immanuel Wallerstein (eds.),

The political economy of contemporary Africa (Beverly Hills and L o n d o n , 1976), 1 1 - 1 2 .

IO

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

PRELUDE TO DECOLONISATION

i s t r a t i o n in K e n y a w i t h its s e t t l e r - f a r m e r s , differed c o n s i d e r a b l y

f r o m t h a t i n t h e G o l d C o a s t , w i t h its i n d i g e n o u s f a r m e r s . W h e r e

the principal m e a n s o f agricultural p r o d u c t i o n w a s t h r o u g h w h i t e

settler-farmers, their interests w e r e held p a r a m o u n t b y the c o l o n i a l

a d m i n i s t r a t i o n s , as i n L i b y a , A l g e r i a a n d S o u t h e r n R h o d e s i a . I n

colonies w h e r e settler-farmers a n d E u r o p e a n - c o n t r o l l e d plan

t a t i o n s w e r e j o i n t l y c o n c e r n e d a s p r o d u c e r s o f e x p o r t c r o p s , as i n

A n g o l a , M o z a m b i q u e a n d the B e l g i a n C o n g o , E u r o p e a n interests

w e r e also held to b e paramount. In colonies w h e r e there w e r e

substantial a n d influential settler g r o u p s w h o w e r e n o t , h o w e v e r ,

s e e n as t h e p r i n c i p a l o r e x c l u s i v e m e a n s o f p r o d u c t i o n o f e x p o r t

c r o p s , A f r i c a n interests w e r e n e v e r entirely s u b o r d i n a t e d t o t h e m .

M o r o c c o , Tunisia, the I v o r y Coast, Northern Rhodesia and K e n y a

fit i n t o this c a t e g o r y . E v e n w i t h r e g a r d t o K e n y a , w h i c h i n t h e

p o p u l a r B r i t i s h i m a g i n a t i o n w a s t h e w h i t e - s e t t l e r c o l o n y par

excellence, as e a r l y as 1 9 2 3 a C o n s e r v a t i v e c o l o n i a l s e c r e t a r y , t h e

D u k e o f D e v o n s h i r e , h a d laid d o w n t h a t :

Primarily Kenya is an African territory, and His Majesty's Government thinks

it necessary definitely to record their considered opinion that the interests of

the African natives must be paramount and that if, and when, those interests

and the interests of the European races should conflict, the former should

p r e v a i l . . . In the administration of Kenya, His Majesty's Government regard

themselves as exercising a trust on behalf of the African population, and they

are unable to delegate or share this trust, the object of which may be defined

1

as the protection and advancement of the native races.

In practice this o f c o u r s e o n l y m e a n t t h e p r o t e c t i o n o f t h e A f r i c a n

p o p u l a t i o n f r o m the m o r e e x t r e m e f o r m s o f racial p r i v i l e g e

exercised b y the E u r o p e a n settlers in A l g e r i a a n d S o u t h e r n

R h o d e s i a , n o t f r o m its o v e r a l l s u b j e c t i o n t o t h e i n t e r e s t s o f t h e

w o r l d capitalist e c o n o m y . N e v e r t h e l e s s , in T a n g a n y i k a , f o r

e x a m p l e , s e t t l e r s w e r e g i v e n financial s u p p o r t a n d p r e f e r e n t i a l

t r e a t m e n t e v e n w h e r e it w a s c l e a r f r o m t h e s t a t i s t i c s t h a t A f r i c a n

farmers w e r e m o r e p r o d u c t i v e .

W h e r e w h i t e settlers a n d c o n c e s s i o n c o m p a n i e s w e r e insigni

ficant c o m p a r e d w i t h t h e A f r i c a n p e a s a n t f a r m e r a s a m e a n s o f

production o f export crops, the political role o f local E u r o p e a n s

w a s equally limited. It w a s in s u c h c o l o n i e s that d e c o l o n i s a t i o n

o r d i s e n g a g e m e n t w a s m o s t e a s i l y a c h i e v e d , as t h e c a s e s o f t h e

G o l d Coast, Nigeria, Upper Volta or Senegal witness. T h e most

1

Indians in Kenya, C o m m a n d paper N o . 1922 ( L o n d o n , 1923), 9.

11

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

PRELUDE TO DECOLONISATION

violent confrontations between Africans and colonial g o v e r n m e n t s

t o o k p l a c e in t h o s e c o l o n i e s w h e r e settler or c o n c e s s i o n - c o m p a n y

i n t e r e s t s w e r e m o s t d e e p l y e n t r e n c h e d , as i n A l g e r i a , S o u t h e r n

Rhodesia or Mozambique.

W h a t e v e r t h e a g e n c y o f p r o d u c t i o n in a c o l o n y - w h i t e s e t t l e r -

farmer, plantation c o m p a n y o r African farmer - those colonial

d e p e n d e n c i e s m o s t i n v o l v e d in the w o r l d capitalist e c o n o m y and

m o s t d i r e c t l y s u b j e c t t o its fluctuations w e r e t h o s e in w h i c h

cultivation o f crops for export had been m o s t intensively

developed.

B y 1 9 3 9 , w h a t e v e r t h e i n t e n s i t y o f its p r o d u c t i o n f o r t h e e x p o r t

market, three distinct zones o f e c o n o m i c activity c o u l d be

1

d i s c e r n e d i n t h e c o n t i n e n t . T h e first, o f c o u r s e , w a s t h a t d e v o t e d

to the p r o d u c t i o n o f c r o p s for e x p o r t b y w h a t e v e r means, w h e t h e r

indigenous farming, forced-labour or wage-labour on European

farms o r concessions. H e r e African labour had been diverted from

p r o d u c t i o n o f f o o d for c o n s u m p t i o n for the h o m e m a r k e t to that

for c o n s u m p t i o n overseas. A s e c o n d z o n e , therefore, had

d e v e l o p e d in w h i c h a principal c o n c e r n w a s p r o d u c t i o n o f f o o d

for c o n s u m p t i o n by the z o n e p r o d u c i n g f o o d for export. T h e third

z o n e , w h i c h in o t h e r circumstances w o u l d h a v e c o n t i n u e d to

concentrate o n agriculture for domestic c o n s u m p t i o n , not h a v i n g

sufficient a g r i c u l t u r a l r e s o u r c e s t o p r o d u c e s u r p l u s f o o d s t u f f s f o r

the e x p o r t or the internal market, had b e c o m e the source o f supply

o f l a b o u r f o r t h e f a r m s o f t h e first t w o z o n e s . S u c h l a b o u r w a s

f o r t h c o m i n g as a r e s u l t o f f o r c e d r e c r u i t m e n t , as in t h e P o r t u g u e s e

c o l o n i e s , the n e e d t o earn a w a g e in o r d e r to p a y taxes, o r t h r o u g h

the desire o f individuals w h o w i s h e d to take a d v a n t a g e o f the

e c o n o m i c opportunities p r o v i d e d b y the colonial e c o n o m y . T h i s

z o n e , o f w h i c h N i g e r and U p p e r V o l t a or, o n the other side o f

the continent, N y a s a l a n d w e r e o b v i o u s e x a m p l e s , w a s also a

principal supplier o f labour for mines, army, roads and railways.

T h u s few Africans escaped the impact o f the colonial e c o n o m y ,

w h o s e m o s t i m p o r t a n t p o l i t i c a l effect o r b y - p r o d u c t w a s t h e

increasing peasantisation and proletarianisation o f the erstwhile

small-scale farmer. T h i s w a s to be o f crucial importance for the

d e v e l o p m e n t o f the nationalist m o v e m e n t s w h i c h secured political

i n d e p e n d e n c e f r o m t h e c o l o n i a l r u l e r s . F o r it w a s f r o m a m o n g t h i s

' See Immanuel Wailerstein, 'Three stages of African involvement in the world

e c o n o m y ' , in G u t k i n d and Wailerstein, Political economy, 30-57.

12

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

PRELUDE TO DECOLONISATION

class that an N k r u m a h f o u n d his ' v e r a n d a h b o y s ' o r a S a m o r a

M a c h e l the recruits for the armies o f F R E L I M O .

O f e q u a l i m p o r t a n c e , t h o u g h s o m e t i m e s d i s a s t r o u s i n t h e effects

o n the w e l l - b e i n g o f those i n v o l v e d , w e r e the l o n g - t e r m c o n

s e q u e n c e s o f this m a s s i v e t r a n s f o r m a t i o n o f the e c o n o m i e s o f

Africa into d e p e n d e n t e c o n o m i e s o f the w o r l d capitalist system.

In m a n y cases this t r a n s f o r m a t i o n led t o an increase in p r o d u c t i o n

o f c r o p s for the e x p o r t m a r k e t that w a s d e t r i m e n t a l , especially in

t h e l o n g - t e r m , t o t h e p r o d u c t i o n o f sufficient c r o p s f o r d o m e s t i c

1

c o n s u m p t i o n . A n o t o r i o u s e x a m p l e o f this d e v e l o p m e n t w a s

the G a m b i a , w h e r e a ' h u n g r y s e a s o n ' resulted from o v e r -

concentration o f labour and land o n g r o u n d n u t s , the chief export

c r o p , to the detriment o f rice, the main subsistence c r o p .

A s Vieira da Silva and de M o r a i s h a v e s h o w n for the H u a m b o

D i s t r i c t in A n g o l a , t h e o v e r - c o n c e n t r a t i o n o n e x p o r t c r o p s l e d i n

the l o n g - t e r m to ' a t r o p h y and d e c a y ' in the rural e c o n o m y since

the surplus d e r i v e d f r o m the p r o d u c t i o n o f the cash c r o p , m a i z e ,

w a s n o t r e i n v e s t e d in the local e c o - s y s t e m , w h i l e soils that w e r e

2

allowed shorter and shorter fallows for regeneration deteriorated.

S u c h r u r a l areas b e c a m e less a n d less c a p a b l e o f s u p p o r t i n g a l o c a l

p o p u l a t i o n t h a t w a s i n a n y c a s e i n c r e a s i n g as a r e s u l t o f i m p r o v e d

and m o r e readily available m e d i c a l facilities, and their y o u n g m e n

h a d i n c r e a s i n g l y t o m i g r a t e in s e a r c h o f w o r k . H u a m b o a n d t h e

G a m b i a r e p r e s e n t e x t r e m e e x a m p l e s o f t h e effects o f a c o l o n i a l

e c o n o m i c system w h o s e principal c o n c e r n w a s w i t h m e e t i n g the

demands o f overseas markets for Africa's export crops, and w h i c h

paid little, if any, attention t o p r o b l e m s c o n c e r n e d w i t h the

production, distribution or i m p r o v e m e n t o f subsistence crops.

This concern with cash-crop production was generalised

t h r o u g h o u t colonial Africa and reinforced b y the taxation and

l a b o u r policies o f the colonial administrations, w h i c h c o m p e l l e d

farmers to d e v o t e m o r e and m o r e e n e r g y , land and time to

p r o d u c t i o n o f cash crops. T o g e t h e r these had important social

c o n s e q u e n c e s . T h e y accelerated the g r o w t h o f a plantation

sub-proletariat and w e r e a m a j o r factor in the m a s s i v e m i g r a t i o n

1

See Chapter 5, where it is shown that by 1975 a majority of African countries were

finding it increasingly difficult to feed themselves even though their economies were

still primarily agricultural.

2

Jorge Vieira da Silva and Julio Artur de Morais, * Ecological conditions of social

change in the central highlands of A n g o l a ' , in Franz-Wilhelm Heimer (ed.), Social change

in Angola (Munich, 1973).

13

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

PRELUDE TO DECOLONISATION

to the t o w n s that t o o k place d u r i n g the p e r i o d c o v e r e d b y this

v o l u m e and the c o n s e q u e n t d e v e l o p m e n t o f an u r b a n s u b -

p r o l e t a r i a t . T h e y affected t h e r e l a t i v e r o l e s o f m e n a n d w o m e n i n