Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Medication Review PDF

Medication Review PDF

Uploaded by

Roselyn DawongOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Medication Review PDF

Medication Review PDF

Uploaded by

Roselyn DawongCopyright:

Available Formats

British Journal of Clinical DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04331.

Pharmacology

Correspondence

Medication reviews Professor Alison Blenkinsopp, School of

Pharmacy, University of Bradford, Bradford

BD7 1DP, UK.

Alison Blenkinsopp,1 Christine Bond2 & David K. Raynor3 Tel.: 01274234698

Fax: 01274235600

1 E-mail: a.blenkinsopp@bradford.ac.uk

School of Pharmacy, University of Bradford, Bradford BD7 1DP, 2Centre of Academic Primary Care,

----------------------------------------------------------------------

University of Aberdeen, Foresterhill, Aberdeen AB25 2ZD and 3School of Healthcare, University of Leeds,

Keywords

Leeds LS2 9JT, UK

medication review, medicines use review,

pharmacists, primary care

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Received

21 December 2011

Accepted

9 May 2012

Accepted Article

Published Online

18 May 2012

Recent years have seen a formalization of medication review by pharmacists in all settings of care. This article describes the different

types of medication review provided in primary care in the UK National Health Service (NHS), summarizes the evidence of effectiveness

and considers how such reviews might develop in the future. Medication review is, at heart, a diagnostic intervention which aims to identify

problems for action by the prescriber, the clinican conducting the review, the patient or all three but can also be regarded as an educational

intervention to support patient knowledge and adherence.There is good evidence that medication review improves process outcomes of

prescribing including reduced polypharmacy, use of more appropriate medicines formulation and more appropriate choice of medicine.

When ‘harder’ outcome measures have been included, such as hospitalizations or mortality in elderly patients, available evidence indicates

that whilst interventions could improve knowledge and adherence they did not reduce mortality or hospital admissions with one study

showing an increase in hospital admissions. Robust health economic studies of medication reviews remain rare. However a review of

cost-effectiveness analyses of medication reviews found no studies in which the cost of the intervention was greater than the benefit.

The value of medication reviews is now generally accepted despite lack of robust research evidence consistently demonstrating cost or

clinical effectiveness compared with traditional care. Medication reviews can be more effectively deployed in the future by targeting,

multi-professional involvement and paying greater attention to medicines which could be safely stopped.

Introduction cost management, into a clinical role involving first medi-

cation review and latterly, in some cases, independent pre-

Awareness of the need to reassess periodically treatment scribing. Government policy documents, including the

to monitor both beneficial and potentially harmful effects National Service Framework for Older People [3], embed-

of polypharmacy was highlighted by Zermansky’s 1990s ded medication review in primary care and led to its inclu-

primary care study which quantified for the first time the sion in the new General Medical Services contractual

large numbers of patients whose long term medicines requirements in 2004 [4], and community pharmacy con-

were not being reviewed year on year [1]. Understanding tracts in England and Wales since 2005 (Medicines Use

was also growing that a needs assessment was required Reviews) and in Scotland since 2010 (Chronic Medication

not only when long term medicines were first started but Service). These examples represent a continuum of

regularly thereafter. Studies of the consequences of approaches ranging from a full clinical review to a more

adverse effects of medicines have consistently shown over superficial check.These different approaches are described

two decades that many hospital admissions are potentially in more detail later in this article, focusing on UK primary

preventable [2]. In hospitals, pharmacists have, since the care and drawing on published evidence from the UK and

1980s, been reviewing medicines charts and making rec- elsewhere.

ommendations to prescribers. This peer review of doctors’

prescribing (known as ‘clinical pharmacy’ in the hospital Why medication use reviews are

setting) generally did not, however, occur in primary care. needed

In the UK the first pharmacists started to work in primary

care medical practices in the late 1980s, and their work A key function of medication review is to identify where

developed from analysis of prescribing data and advice on adherence support is needed. We know that only

© 2012 The Authors Br J Clin Pharmacol / 74:4 / 573–580 / 573

British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology © 2012 The British Pharmacological Society

A. Blenkinsopp et al.

approximately 50% of long term medicines are actually consultation. It involves evaluating the therapeutic efficacy of

taken as directed [5]. We also know that adherence gener- each drug and the progress of the conditions being treated.

ally decreases as the length of time a medicine has been Other issues, such as compliance, actual and potential

taken increases. Adherence support needs to take account adverse effects, interactions, and the patient’s understanding

of the extent to which non-adherence is intentional and/or of the condition and its treatment are considered when

intentional. Side effects are one of the influencers of adher- appropriate. The outcome of the review will be a decision

ence, and a key function of medication review is to assess about the continuation (or otherwise) of the treatment’ [8].

whether side effects are happening. The National Institute Medication review is, at heart, a diagnostic intervention

for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) Guideline on which aims to identify problems for action by the pre-

Medication Adherence emphasizes the importance of a scriber, patient or both but can also be regarded as an

joint approach to medication review with the patient educational intervention to support patient knowledge

taking a full role to maximize best use of medicines [6]. and adherence. The balance of these elements varies in

Medication review is particularly relevant in polypharmacy practice and the boundaries between the three types of

(four or more long term medicines), especially in older review are not clear cut. Table 2 shows the reviews cur-

people, where medicines are an important cause of rently being provided in NHS care in the UK. In all of these

unplanned hospital admissions. The use of such long term cases, the patient is involved in the review.

medicines is increasing, especially preventative medicines To refine further the definition of a clinical medication

where adherence is particularly low. In addition, when review, it has been suggested [11] that it should:

patients taking many medicines visit their primary care

doctor, the consultation usually focuses on one or two of • Check whether the patient still needs to be on all of their

their conditions and there is insufficient time for an overall medicines

review of all medicines. • Find out whether the medicines are helping the patient

• Find out whether the medicines are causing harm or risk

to the patient

What is meant by ‘medication • Explore whether the patient is happy to continue to

review’? receive and take the medicines

• Find out whether the patient should be offered any addi-

The overall aim of medication review is to improve the tional medicines for treated or untreated conditions.

quality, safety and appropriate use of medicines. ‘Medica-

tion review’ is an umbrella term which encompasses a The General Medical Services (GMS) contract advises

number of interventions that might be carried out by pre- medication review (‘clinical medication review’) should be

scribers themselves (self-review by doctors, pharmacists, undertaken every 15 months for all patients being pre-

nurses) or by other practitioners providing advice to pre- scribed repeat medicines. Reviews may be conducted by a

scribers (independent review, usually done by pharma- GP, a practice-based pharmacist or a practice-based nurse.

cists). This article focuses on the latter. The three types of A review‘may not always necessarily be a face to face review.

review described by Medicines Partnership [7] have It is possible to review the patient’s repeat prescriptions in

become widely cited: Prescription review, Compliance and some circumstances without seeing the patient face to face,

concordance review and Clinical medication review (see e.g. by telephone review or a review of the records’. [4]

Table 1) A key benefit of fully involving the patient in a medica-

Clinical medication review was first defined by Zerman- tion review is that this can support and facilitate ‘partner-

sky et al. as ‘the process where a health professional reviews ship in medicine taking’ (see ‘Prescribing and partnership

the patient, the illness, and the drug treatment during a with patients’). Medicines review with full input from the

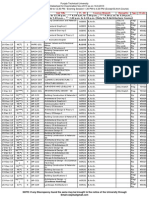

Table 1

Types of medicines review (Medicines Partnership, 2008) [7])

Type Scope Method

Prescription review Practical medicines management issues that can improve the clinical Usually without patient present

and cost-effectiveness of medicines and patient safety

Compliance and Explore medicine taking including the patient’s pattern of medicine With patient present

concordance review taking and beliefs about medicines

Clinical medication review Consider treatment in the context of the patient’s underlying With patient present and with access to patient’s medical notes and

condition and symptoms. laboratory test results

574 / 74:4 / Br J Clin Pharmacol

Medication reviews

Table 2

Medication reviews in the National Health Service

Review type Conducted by Purpose

Medicines Use Review Community pharmacists ‘Helping patients use their medicines more effectively. The pharmacist will perform a MUR to help assess any problems

(MUR) in England and Wales patients have with their medicines and to help develop the patient’s knowledge about their medicines.

Recommendations made to prescribers may also relate to the clinical or cost effectiveness of treatment’ [9].

Dispensing review of Dispensing practices (by ‘Help patients understand their medicines and to identify medicines-related problems’.

use of medicines GP or dispenser)

(DRUM)

Chronic medication Community pharmacists ‘Pharmaceutical care of patients with long term conditions. It introduces a more systematic way of working and formalizes

service in Scotland the role of community pharmacists in the management of individual patients with long term conditions in order to assist

in improving the patient’s understanding of their medicines and optimizing the clinical benefits from their therapy’. It

involves patients registering with a pharmacy of their choice. The pharmacist identifies and records the patient’s

pharmaceutical care needs, care issues, any desired outcomes and the actions required to deliver those outcomes, and

documents these in a pharmaceutical care plan.

Comprehensive Hospital pharmacists ‘Distinct from the more routine review of drug charts that pharmacists make on ward visits. Can take place at any point

medication review during the hospital stay, generally when there is a concern about potential interaction of medicines or the patient has

(Hospital) not been responding to their medication as expected’ [7]. Often conducted as part of medicines reconciliation when a

patient is admitted to hospital.

Clinical medication GP practice-based ‘A structured, critical examination of a patient’s medicines with the objective of reaching an agreement with the patient

review pharmacists; about the continued appropriateness and effectiveness of the treatment, optimizing the impact of medicines, minimizing

Community the number of medication related problems and reducing waste’.

pharmacists; ‘The pharmacist will provide further advice and support regarding the patient’s use of medicines and, where appropriate,

will refer the patient to another health care professional’ [10].

patient may lead to ‘an agreement to differ’ where the countries have taken different approaches. In Australia the

desired prescribing and clinical outcomes (from a profes- model is of‘Collaborative home medication reviews (HMR)’

sional perspective), are not achieved. However, this is the where patients whose treatment appears in need of review

appropriate outcome for that patient. are identified by a GP or community pharmacist and joint

Community pharmacists in England and Wales provide patient outcomes agreed as goals of the review. Medicines

‘medicines use reviews’ (MURs) as part of their NHS con- information is shared by the GP with the pharmacist, who

tract.The pharmacist has to be accredited to provide MURs visits the patient in their own home (or in a care home) to

and the pharmacy premises must have a consultation area conduct the review and then reports back to the GP. Medi-

that meets NHS standards of privacy. The focus of MURs is cation Therapy Management (MTM) services in the US

on establishing how the patient is using (or not) their include reviews of patients’ medicines by community

medicines and covers both prescribed and non-prescribed pharmacists and other service providers.

medicines. MURs are now targeted towards particular

patient groups and core groups include those taking ‘high

risk’ medicines, e.g. warfarin, those with asthma/COPD and Effectiveness of medication reviews

those recently discharged from hospital. Dispensing prac-

tices provide DRUMs (Dispensing Review of Use of Medi- This section traces the introduction and development of

cines) which, like MURs, have a focus on the patient’s use of medication review in UK primary care drawing on pub-

medicines. In Scotland a similar service, the Chronic Medi- lished systematic and structured reviews of relevant

cation Service (CMS) is part of the core community phar- literature and the authors’ own literature collections

macy contract. It has a slightly more holistic remit than the supplemented by structured searches to ensure currency.

MUR service, delivering a full pharmaceutical care assess- Work in general practices in Dundee, Scotland during the

ment, plan and implementation. It also includes the use of 1990s was one of the earliest examples of a robustly evalu-

serial prescriptions to allow repeat prescribing of long ated systematic approach to medicines management in

term medication and communication and data storage is primary care based on medication review [12, 13]. Building

all electronic, with transfer of information between GP and on the‘clinical pharmacy’role pharmacists had in hospitals,

pharmacist. experienced hospital pharmacists worked with GPs to

Thus, medication review has been formalized in NHS review prescribing of sub-groups of the registered patients

contracts extensively in the UK with an underlying pre- receiving treatment for certain targeted conditions. In one

sumption that all patients on medication for long term of the earliest examples of such a service, all patients

conditions should have at least an annual review. Other receiving ulcer healing medicines were reviewed jointly by

Br J Clin Pharmacol / 74:4 / 575

A. Blenkinsopp et al.

the pharmacist and the GP and those with no recorded analysis of a targeted service where pharmacists con-

diagnosis or no recent ordering of the drug had their ducted a medication review in the patient’s own home

repeat discontinued. All other patients were invited to found that costs were offset by reductions in emergency

attend a clinic where they were reviewed by the pharma- hospital admissions and in medicines costs [26]. A large UK

cist and subsequent treatment was in accordance with study (PINCER study) compared simple computerized

guidelines agreed with the GP. As a result overall expendi- feedback to GPs about patients at risk of potentially haz-

ture on this group of drugs in one general practice fell at a ardous prescribing with a joint review of the feedback by

time when it was generally rising elsewhere [12].The same pharmacist, GP and other members of the practice team

team reported similar benefits for pharmacist led warfarin [27]. The study included a full economic analysis and

clinics [13] the results indicated that the intervention reduced the

Subsequently medication review by an emerging risk of prescribing and monitoring errors for NSAIDs,

group of UK primary care pharmacists became a well b-adrenoceptor blockers and ACE inhibitors 6 months post

established service despite little strong evidence of health intervention.

economic benefit [14].Whilst many trials reported benefits In common with much research there are indications

in one or two parameters few would meet current meth- that moving from studies of medication review with rela-

odological standards and only one early US study included tively small sample sizes and often a single (or a small

a cost analysis which showed a small per patient saving number) of highly trained committed pharmacists, to

[15]. wider implementation to more patients and more pharma-

There is now good evidence that medication review cists, there is a dilution of effect. For example, the Commu-

improves process outcomes of prescribing such as nity Pharmacy Medicine Management study was a

reduced polypharmacy, more appropriate formulation, randomized controlled trial to test the effect of medication

and more appropriate choice of medicine [8, 16–18] and review on clinical indicators in patients with coronary

that GPs have accepted and implemented high percent- heart disease involving 1493 patients, 62 community phar-

ages of such changes recommended by pharmacists in the macists and 164 GPs. Patients’ treatment was reviewed by

UK [8, 16–18] and in Australia [19, 20].There is an increasing the community pharmacist in the pharmacy setting in a

call for evidence of the benefit of medication review using model that in some ways was a forerunner to MURs.

longer term clinical outcomes. When ‘harder’ outcome Despite increased patient satisfaction in the group receiv-

measures have been included such as reduced hospitaliza- ing the intervention and recommendations for medication

tions or mortality in elderly patients a systematic review change in line with previously published work [28], there

concluded that whilst interventions could improve knowl- were no improvements in any of the clinical indicators [29].

edge and adherence they did not reduce mortality or hos- The performance of individual community pharmacists in

pital admissions with one study showing an increase in the Community Pharmacy Medicines Management Study

hospital admissions [21]. Another review likewise con- showed considerable variation [28], also a finding in

cluded limited benefit [22].There is debate, however, about another multi-pharmacist study [30]. In New Zealand a ran-

whether total hospital admission numbers are an appro- domized controlled trial of community pharmacist con-

priate outcome measure for medication review and an ducted medication review found improved Medication

analysis of the causes of admission in a cohort of patients Appropriateness Index (MAI) in the intervention group but

found that only one in five were considered to be related withdrawal of one in three study pharmacists from the

to medicines and only one in 10 were judged possibly study raised questions about generalizability [31].

preventable by pharmacist intervention [23]. There have been few studies of the effectiveness of

A similar picture has emerged for medication reviews MUR and a review concluded that ‘studies evaluating

conducted in institutional settings with a review conclud- directed MUR services, focusing on a particular disease,

ing that whilst the interventions reduced prescribing there were most likely to report clinical outcomes’ [32]. In con-

is still a need for evidence to demonstrate benefits related trast the HMR service in Australia has been the subject of

to health care costs and patient outcomes [24]. An excep- several substantive studies which have demonstrated

tion to the overall conclusion of the review is a UK paper effectiveness in preventing, detecting and resolving

which studied pharmacist led medication review for medication-related problems [20] and cohort studies in

elderly people living in care homes and showed a reduc- Australian veterans have shown reductions in hospitaliza-

tion in falls but no change in hospitalization, mortality or tions associated with heart failure [33] or warfarin [34–36].

other validated patient scales [16]. Despite much of the groundbreaking work in primary

Robust health economic studies of medication review care having been led by hospital pharmacists there are few

remain rare but a review of cost-effectiveness of medica- studies of medication review in hospitals. A Cochrane

tion reviews concluded ‘there were no reports of studies in review is ongoing and the results should be of wide inter-

which the cost of the intervention was greater than the est (medication review of hospitalized patients to prevent

benefit, and several reported a cost saving when measur- morbidity and mortality: Effective Practice and Organiza-

ing drug cost change only’ [25]. A cost consequences tion of Care group http://www.epoc.cochrane.org).

576 / 74:4 / Br J Clin Pharmacol

Medication reviews

In summary recent years have seen a formalization of also an annual review it is undertaken in the practice

medication review by pharmacists in all settings of care. setting where the practice pharmacist has access not only

The value of this service is now generally accepted despite to patient notes but also to other health professionals with

lack of robust research evidence consistently demonstrat- whom necessary communication and changes are more

ing any cost or clinical effectiveness compared with tradi- easily implemented.

tional care. Acceptance of treatment recommendations made by

pharmacists in medication reviews is fundamental to

improving treatment quality. However prescribers’ levels

Factors affecting the quality and of agreement with, and changes made as a result of the

effectiveness of medication use recommendations have varied markedly in studies. The

reviews relationship between the prescriber and the practitioner

conducting the review is now recognized to be critical.

Authors of evidence reviews in clinical medication reviews Acceptance of the need for review and trust in the practi-

and MURs have identified the key explanatory factors that tioner doing the review is essential to open dialogue about

impact on quality and effectiveness and account for the recommendations to prescribers that may result. As

inconsistent benefit shown in studies: described earlier the benefits of medication review can be

maximized by full involvement of the patient but as this

• the quality of the recommendations made by pharma- may lead to an ‘agreement to differ’ where the desired

cists improves when pharmacists have more patient prescribing and clinical outcomes (from the professional

information [37] perspective) are not achieved, measuring the effectiveness

• without a good working relationship between the clini- of medication reviews only on the basis of adherence will

cian and pharmacist, the impact of pharmacist medica- not give the full picture.

tion review is reduced and may be minimal [21, 37] Knowledge and skills to build on pharmacists’ knowl-

• written recommendations from a pharmacist to a clini- edge of medicines and underpin medication review

cian, in the absence of other forms of communication, include consultation skills, use of clinical records and com-

have limited effect [37] munication of issues and recommendations arising from

• other pharmacist interventions with similar components the reviews. Community pharmacy service specifications

have been effective when pharmacists form part of a for medication review in different countries, including

team [21] within the UK, require training and accreditation. Many of

• variation in the consultation skills of practitioners con- the published studies referred to in the effectiveness

ducting medication review [7]. section of this paper stated that additional training was a

pre-requisite of participation. In addition, the increasing

In reviews undertaken in the community pharmacy cadre of pharmacists who have completed qualification as

setting the pharmacist can refer to their computerized an independent prescriber will have received consultation

patient medication records (PMRs) and can consult with skills training and will also have the ability to make

the patient for further information. For a MUR where the changes without reference to the prescriber who initiated

focus is on practical use of medicines this may be suffi- the therapy.

cient. These sources are not adequate for a clinical medi-

cation review, where access to the patient’s notes is

needed. Community pharmacists usually do not have such

access (with a few exceptions where the pharmacy and The future of medication use

surgery are electronically linked). Some community phar- reviews

macists also do sessional work as practice based pharma-

cists and may undertake clinical medication review in There are three key ways in which medication reviews can

these practices. be more effectively deployed in the future:targeting,multi-

Frequency of review may also be important but it is the professional involvement and paying greater attention to

follow-up actions that are more likely to be critical. The medicines which could be safely stopped.

MUR is a single intervention intended to be conducted There are already some moves towards more effective

annually with implications for potential impact as a stand targeting of the resource invested in mediation reviews to

alone service. The lack of dialogue between community patients whose need is greatest. However this process

pharmacists and GPs is well recognized as a limitation of needs to develop at GP practice level and an analysis of the

the MUR process. However the potential for MURs to assist effects of the Quality and Outcomes Framework (the QOF,

in improving patient outcomes is considerable and their which has been part of the general practice contract since

core purpose, to improve patients’ understanding of their 2004) on the quality of care concluded that‘although there

medicines, is clinically important [38]. Although clinical is ostensibly an annual medication review target in the

medication review undertaken within the GMS contract is QOF, it is doubtful that this really stimulates meaningful

Br J Clin Pharmacol / 74:4 / 577

A. Blenkinsopp et al.

risk benefit analysis and rationalization of medicines in 2 Pirmohammed M, James S, Meakin S, Green C, Scott AK,

older people with multiple diseases’ [39]. Walley TJ, Farrar K, Park BK, Breckenridge AM. Adverse drug

Evidence from Australia provides a strong indication reactions as cause of admission to hospital: prospective

analysis of 18,820 patients. BMJ 2004; 329: 15–9.

that pharmacists and prescribers in primary care need to

work more closely together if the potential benefits of 3 Department of Health. 2001. National service framework for

medication use reviews are to be realized. In a forthcoming older people.

randomized controlled trial of a multi-professional medi-

4 GP Committee of the BMA and the NHS Confederation.

cation review service (MMRS) pharmacists, pharmacy tech-

Investing in General Practice: The New General Medical

nicians, care home staff and the GP(s) responsible for the Services Contract. London: British Medical Association,

medical care of residents will take a team approach, National Health Service Confederation, 2003.

meeting together to review and discuss the medications of

care home residents [40]. Community pharmacist involve- 5 Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, McDonald HP, Yao X.

Interventions for enhancing medication adherence.

ment in reviews post discharge is now a focus of the MUR

Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008; (2): CD000011. DOI:

service in England and Wales and will require a step 10.1002/14651858.CD000011.pub3.

change in communication not only between community

pharmacist and GP but also between hospitals and their 6 National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. 2009.

community pharmacist and GP colleagues. Medicines adherence: involving patients in decisions about

Recent work on ‘deprescribing’ with MUR as the means prescribed medicines and supporting adherence.

to identify treatments that can be stopped is ripe for 7 Clyne W, Blenkinsopp A, Seal R. 2008. A guide to medication

further study [41]. Monitored withdrawal of medicines review. Keele University. NPC Plus & Medicines Partnership.

known to be associated with adverse effects has the Available at http://www.npc.nhs.uk/review_medicines/

potential to both improve patients’ quality of life and intro/resources/agtmr_web1 (last accessed 25 June 2012).

reduce unnecessary resource use. A pilot randomized con- 8 Zermansky AG, Petty DR, Raynor DK, Lowe CJ, Freemantle N,

trolled trial showed sufficiently promising results, with Vail A. Clinical medication review by a pharmacist of patients

greater reductions in prescribing in the intervention group on repeat prescriptions in general practice: a randomised

[42], to warrant larger studies. controlled trial. Health Technol Assess 2002; 6: 1–86.

9 Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee/NHS

Conclusions Employers. 2012. Service specification: medicines use review

and prescription interventions. Available at http://www.

Medication review is now a well established part of UK psnc.org.uk/data/files/PharmacyContractandServices/

primary care based on evidence of reductions in polyp- AdvancedServices/MUR_service_spec_Jan_2012.pdf (last

harmacy and increased appropriateness of prescribing. A accessed 25 June 2012).

key outcome has been a greater use of, and thereby rec- 10 Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee. 2005.

ognition of the skills of, pharmacists attached to general Service specification: medication review. (Full Clinical

practices and in community settings. Reviews conducted Review) Available at http://www.psnc.org.uk/data/files/

by community pharmacists in the pharmacy setting will PharmacyContract/enhanced_service_spec/en7__

require more formal systems for linkage to GPs if they are medication_review.pdf (last accessed 25 June 2012).

to achieve their potential. This, together with targeting 11 Blenkinsopp A, Lowe C. Medicines reviews. BMJ Learning

of patients who are prescribed medicines associated 2011.

with higher risk of hospital admission and morbidity

12 Macgregor SH, Hamley JG, Dunbar JA, Dodd TR, Cromarty JA.

and the proactive identification of medicines that could

Evaluation of a primary care anticoagulant clinic managed

be withdrawn, will offer further improvements in by a pharmacist. BMJ 1996; 312: 560–560.

effectiveness.

13 Macgregor S. Disease management. In: Evidence Based

Pharmacy, ed. Bond C. London: Pharmaceutical Press, 2000;

Competing Interests 115–29.

DKR is co-founder and academic advisor to Luto Research 14 Fish A, Watson M, Bond C. Practice based pharmaceutical

Ltd, which develops, refines and tests patient information services: a systematic review. Int J Pharm Pract 2002; 10:

225–33.

materials.

15 Stergachis A, Fors M, Wagner E, Sims D, Penna P. Effect of

clinical pharmacists on drug prescribing in a primary care

clinic. Am J Hosp Pharm 1987; 44: 525–9.

REFERENCES

16 Zermansky AG, Alldred DP, Petty DR, Raynor DK,

1 Zermansky AG. Who controls repeats? Br J Gen Pract 1996; Freemantle N, Eastaugh J, Bowie P. Clinical medication

46: 643–7. review by a pharmacist of elderly people living in care

578 / 74:4 / Br J Clin Pharmacol

You might also like

- Community Pharmacy Symptoms, Diagnosis and Treatment by Paul RutterDocument489 pagesCommunity Pharmacy Symptoms, Diagnosis and Treatment by Paul RutterNhi Nguyễn75% (8)

- Test Bank For Pharmacotherapeutics For Advanced Practice 4th EditionDocument4 pagesTest Bank For Pharmacotherapeutics For Advanced Practice 4th EditionMichael Pupo59% (17)

- Pharmaceutics: Basic Principles and Application to Pharmacy PracticeFrom EverandPharmaceutics: Basic Principles and Application to Pharmacy PracticeAlekha DashNo ratings yet

- Guideline Watch 2021Document24 pagesGuideline Watch 2021Pedro NicolatoNo ratings yet

- MCQ PharmacologyDocument136 pagesMCQ PharmacologyIbrahim Negm96% (54)

- Medspan's Pharmacy Guide For OSCEDocument8 pagesMedspan's Pharmacy Guide For OSCEDeviselvam100% (1)

- 2019 Article 816Document37 pages2019 Article 816Annafiatu zakiahNo ratings yet

- Systemic Medicines Taken by Adult Special CareDocument10 pagesSystemic Medicines Taken by Adult Special CareAlistair KohNo ratings yet

- Brit J Clinical Pharma - 2013 - Nguyen - What Are Validated Self Report Adherence Scales Really Measuring A SystematicDocument19 pagesBrit J Clinical Pharma - 2013 - Nguyen - What Are Validated Self Report Adherence Scales Really Measuring A SystematicparameswarannirushanNo ratings yet

- Dispensing Activity in A Community Pharmacy-Based Repeat Dispensing Pilot ProjectDocument8 pagesDispensing Activity in A Community Pharmacy-Based Repeat Dispensing Pilot Projectsaw thidaNo ratings yet

- Paediatric Pharmacokinetics: Key Considerations: Hannah Katharine Batchelor & John Francis MarriottDocument10 pagesPaediatric Pharmacokinetics: Key Considerations: Hannah Katharine Batchelor & John Francis MarriottAlloiBialbaNo ratings yet

- A Review On Extended Release Drug Delivery SystemDocument9 pagesA Review On Extended Release Drug Delivery SystemTuyến Đặng ThịNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2667278221000766 MainDocument5 pages1 s2.0 S2667278221000766 MainHarold fotsingNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of NHS Medicines Waste Web Publication VersionDocument106 pagesEvaluation of NHS Medicines Waste Web Publication VersionEmmanuelNo ratings yet

- TDM AntimikrobaDocument10 pagesTDM AntimikrobaDaniel GiantinoNo ratings yet

- A Study To Assess The Impact of Pharmaceutical Care Services To Cancer Patients in A Tertiary Care HospitalDocument10 pagesA Study To Assess The Impact of Pharmaceutical Care Services To Cancer Patients in A Tertiary Care HospitalRaya PambudhiNo ratings yet

- Should Hospital Pharmacists Prescribe?: The Canadian Journal of Hospital Pharmacy October 2014Document5 pagesShould Hospital Pharmacists Prescribe?: The Canadian Journal of Hospital Pharmacy October 2014Tenzin TashiNo ratings yet

- Article Wjpps 1467683350 PDFDocument13 pagesArticle Wjpps 1467683350 PDFNur FitriNo ratings yet

- Brit J Clinical Pharma - 2013 - Batchelor - Paediatric Pharmacokinetics Key ConsiderationsDocument10 pagesBrit J Clinical Pharma - 2013 - Batchelor - Paediatric Pharmacokinetics Key ConsiderationsYosep SembiringNo ratings yet

- Clinical Pharmacist Role in Drug Information ServiDocument9 pagesClinical Pharmacist Role in Drug Information ServiDesalegn DansaNo ratings yet

- A Pilot Study To Evaluate A Community Pharmacy - Based Monitoring System To Identify Adverse Drug Reactions Associated With Paediatric Medicines UseDocument6 pagesA Pilot Study To Evaluate A Community Pharmacy - Based Monitoring System To Identify Adverse Drug Reactions Associated With Paediatric Medicines UsekhanNo ratings yet

- Antibiotic Dosing in Critically Ill Patients With Acute Kidney InjuryDocument11 pagesAntibiotic Dosing in Critically Ill Patients With Acute Kidney InjuryHa LinhNo ratings yet

- Prof. Gregory PetersonDocument17 pagesProf. Gregory PetersonandrianiNo ratings yet

- Mucoactive Agent Use in Adult UK Critical Care UniDocument12 pagesMucoactive Agent Use in Adult UK Critical Care Uniklinik4habibaNo ratings yet

- TugasDocument16 pagesTugaselsarahmiNo ratings yet

- bcp0065 0386Document10 pagesbcp0065 0386gabyvaleNo ratings yet

- 10 Svensberg2020 Article PatientsPerceptionsOfMedicinesDocument10 pages10 Svensberg2020 Article PatientsPerceptionsOfMedicinesmehakNo ratings yet

- Effect of Medication Reconciliation at Hospital AdDocument12 pagesEffect of Medication Reconciliation at Hospital AdJasmin Kae SistosoNo ratings yet

- MedicationReview PracticeGuide2011Document29 pagesMedicationReview PracticeGuide2011Yusnia Gulfa MaharaniNo ratings yet

- Ok INTOXICACION ACETAMONIFEN GUIAS UK 2014Document9 pagesOk INTOXICACION ACETAMONIFEN GUIAS UK 2014Ingrid Paola Serrano MoralesNo ratings yet

- Conciliação 005Document13 pagesConciliação 005Izabella WebberNo ratings yet

- Medication-Related Problems in Critical Care Survivors - A Systematic ReviewDocument7 pagesMedication-Related Problems in Critical Care Survivors - A Systematic ReviewenesNo ratings yet

- The Role of Pharmacists in Minimizing Medication Errors in The Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: A Systematic ReviewDocument10 pagesThe Role of Pharmacists in Minimizing Medication Errors in The Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: A Systematic ReviewIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Audi S. (Baker E) Top 100 Drugs - Updated. BJCP 2018Document10 pagesAudi S. (Baker E) Top 100 Drugs - Updated. BJCP 2018rheaNo ratings yet

- Ebook Community Pharmacy Symptoms Diagnosis and Treatment PDF Full Chapter PDFDocument67 pagesEbook Community Pharmacy Symptoms Diagnosis and Treatment PDF Full Chapter PDFnancy.larsen721100% (34)

- Community Pharmacy Symptoms Diagnosis and Treatment 5Th Edition Edition Paul Rutter Full ChapterDocument67 pagesCommunity Pharmacy Symptoms Diagnosis and Treatment 5Th Edition Edition Paul Rutter Full Chaptermargaret.perez647100% (5)

- PIIS0085Document17 pagesPIIS0085Rizki Fadil AzzamyNo ratings yet

- Basic Clin Pharma Tox - 2019 - TukukinoDocument10 pagesBasic Clin Pharma Tox - 2019 - Tukukinopurushothama reddyNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0085253815549843 MainDocument16 pages1 s2.0 S0085253815549843 MainDhanang Prawira NugrahaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 General Introduction To Clinical PharmacyDocument120 pagesChapter 1 General Introduction To Clinical PharmacyEmmaNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Clinical Pharmacists InterDocument7 pagesThe Impact of Clinical Pharmacists Interahmed1fkwnNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Clinical Services Provided by Community Pharmacies On The Australian Healthcare System A Review of The Literature Journal of PharmaceutDocument42 pagesThe Impact of Clinical Services Provided by Community Pharmacies On The Australian Healthcare System A Review of The Literature Journal of PharmaceutBIANCA KARLA LICATANNo ratings yet

- Ferner, R.E.ab Postmortem-clinical-pharmacologyReview 2008Document14 pagesFerner, R.E.ab Postmortem-clinical-pharmacologyReview 2008Rafael SallesNo ratings yet

- Brit J Clinical Pharma - 2013 - Bolea Alamanac - Methylphenidate Use in Pregnancy and Lactation A Systematic Review ofDocument6 pagesBrit J Clinical Pharma - 2013 - Bolea Alamanac - Methylphenidate Use in Pregnancy and Lactation A Systematic Review ofAndrés WunderwaldNo ratings yet

- 22A6761 - 222203.final ResarchDocument31 pages22A6761 - 222203.final Resarchrameshwar9595kNo ratings yet

- The Role of The Pharmacist in Patient Care (Book Review)Document22 pagesThe Role of The Pharmacist in Patient Care (Book Review)A. K. MohiuddinNo ratings yet

- HPCP Assignment 2Document8 pagesHPCP Assignment 2mokshmshah492001No ratings yet

- Assessment of Appropriateness of Medical Prescriptions in Community Pharmacies and Adoption of WHO Prescribing IndicatorsDocument4 pagesAssessment of Appropriateness of Medical Prescriptions in Community Pharmacies and Adoption of WHO Prescribing IndicatorsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Aldeyab (2010) - A Point Prevalence Survey of Antibiotic Prescriptions, Benchmarking and Patterns of UseDocument4 pagesAldeyab (2010) - A Point Prevalence Survey of Antibiotic Prescriptions, Benchmarking and Patterns of UseAdeline IntanNo ratings yet

- Article Group ADocument18 pagesArticle Group Alollipop1234556677No ratings yet

- Drug Utilization Patterns Using Who Core Prescribing Indicators in Different Out Patient Departments at Secondary Care Hospital, KarimnagarDocument9 pagesDrug Utilization Patterns Using Who Core Prescribing Indicators in Different Out Patient Departments at Secondary Care Hospital, KarimnagarIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Al Babtain2021Document10 pagesAl Babtain2021Nabilah ZulfaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Pharmacist in ICUDocument26 pagesClinical Pharmacist in ICUApriyanNo ratings yet

- Review of Pharmaceutical Care Services Provided by The PharmacistsDocument3 pagesReview of Pharmaceutical Care Services Provided by The PharmacistsellianaeyNo ratings yet

- Adherence To Medication. N Engl J Med: New England Journal of Medicine September 2005Document12 pagesAdherence To Medication. N Engl J Med: New England Journal of Medicine September 2005Fernanda GilNo ratings yet

- Ractice Nsights: The Critical Care Pharmacist: An Essential Intensive Care PractitionerDocument5 pagesRactice Nsights: The Critical Care Pharmacist: An Essential Intensive Care PractitionerDaniela HernandezNo ratings yet

- Clinical Pharmacy ReviewDocument8 pagesClinical Pharmacy Reviewsagar dhakalNo ratings yet

- Ethics in Pharmacy Practice 200910 PDFDocument38 pagesEthics in Pharmacy Practice 200910 PDFjohnassesNo ratings yet

- Modified Pharmacy Counseling Improves Outpatient Short-Term Antibiotic Compliance in Bali ProvinceDocument10 pagesModified Pharmacy Counseling Improves Outpatient Short-Term Antibiotic Compliance in Bali ProvinceIJPHSNo ratings yet

- 2012 Vrijens Et AlDocument15 pages2012 Vrijens Et AlKharen BimajaNo ratings yet

- Pharmacy 8040213Document20 pagesPharmacy 8040213muhammad raflyNo ratings yet

- Dhanya Kerala 2021Document5 pagesDhanya Kerala 2021xyzNo ratings yet

- Acute Headache: Leeran Baraness Annalee M. BakerDocument6 pagesAcute Headache: Leeran Baraness Annalee M. BakerRoselyn DawongNo ratings yet

- 03 Medication-Related ProblemsDocument13 pages03 Medication-Related ProblemsRoselyn DawongNo ratings yet

- 01 Introduction To DispensingDocument30 pages01 Introduction To DispensingRoselyn DawongNo ratings yet

- Roselyn Dawong Indigenous PeoplejpicDocument6 pagesRoselyn Dawong Indigenous PeoplejpicRoselyn DawongNo ratings yet

- The Natural ApproachDocument11 pagesThe Natural ApproachRoselyn DawongNo ratings yet

- 4 Writing Behavioral ObjectivesDocument45 pages4 Writing Behavioral ObjectivesRoselyn DawongNo ratings yet

- Dales Cone of ExperienceDocument36 pagesDales Cone of ExperienceRoselyn DawongNo ratings yet

- 5 Year Strategic PlanDocument13 pages5 Year Strategic PlanRoselyn Dawong100% (1)

- Daily Learning Plan (DLP) Name Grade Level Teacher Learning Area Teaching Dates and Time QuarterDocument4 pagesDaily Learning Plan (DLP) Name Grade Level Teacher Learning Area Teaching Dates and Time QuarterRoselyn DawongNo ratings yet

- CPDprogram PHARMACY91917Document66 pagesCPDprogram PHARMACY91917PRC BoardNo ratings yet

- USP Dissolution StudiesDocument18 pagesUSP Dissolution StudiesSayeeda MohammedNo ratings yet

- Provisional DateSheet Nov13Document68 pagesProvisional DateSheet Nov13IshanVermaNo ratings yet

- 261410761Document101 pages261410761ERNA KRISTINANo ratings yet

- Drug Study - CetirizineDocument3 pagesDrug Study - Cetirizinekkd nyleNo ratings yet

- In Vivo in Vitro CorrelationDocument4 pagesIn Vivo in Vitro CorrelationAmira HelayelNo ratings yet

- Medication - Chart ADHD PDFDocument2 pagesMedication - Chart ADHD PDFaayceeNo ratings yet

- Clinical Landscape - Report On Ivermectin 2020-05-01Document43 pagesClinical Landscape - Report On Ivermectin 2020-05-01Hoyt NelsonNo ratings yet

- TemplateDocument15 pagesTemplateSelvi Diah MutiaraNo ratings yet

- Daftar Harga-1Document78 pagesDaftar Harga-1Adrian JayaNo ratings yet

- Pharmacological and Synthetic Profile of Benzothiazepine: A ReviewDocument9 pagesPharmacological and Synthetic Profile of Benzothiazepine: A ReviewRao Zikar IslamNo ratings yet

- Reference Guide For The Pharmacy Licensing Exam - Questions and AnswersDocument81 pagesReference Guide For The Pharmacy Licensing Exam - Questions and AnswersNikka LaborteNo ratings yet

- Inclisiran ProspectoDocument12 pagesInclisiran ProspectoGuillermo CenturionNo ratings yet

- PharmacistDocument2 pagesPharmacistcrisjavaNo ratings yet

- 8888Document3 pages8888Mhd iconicNo ratings yet

- Date PTU 2013Document76 pagesDate PTU 2013Ravneet SinghNo ratings yet

- Daftar Obat AsoDocument2 pagesDaftar Obat AsoekarizqiamaliyahNo ratings yet

- US Transdermal Patch Market Outlook 2020Document11 pagesUS Transdermal Patch Market Outlook 2020Neeraj ChawlaNo ratings yet

- Principles of Drug BiotransfornationDocument83 pagesPrinciples of Drug BiotransfornationSunil100% (2)

- Drugs) : NO Jenis Obat (The Dosis (Dosage) Jumlah (Amount) NO Jenis Obat (The Drugs) Dosis (Dosage) Jumlah (Amount)Document2 pagesDrugs) : NO Jenis Obat (The Dosis (Dosage) Jumlah (Amount) NO Jenis Obat (The Drugs) Dosis (Dosage) Jumlah (Amount)Ria FiNo ratings yet

- Prescription and Medication Order 2013 (Compatibility Mode)Document7 pagesPrescription and Medication Order 2013 (Compatibility Mode)jonasestrada97No ratings yet

- Data Pemakaian Obat 2020Document42 pagesData Pemakaian Obat 2020Apt Sitta SobiriantiniNo ratings yet

- QsarDocument36 pagesQsarachsanuddin100% (3)

- Test Bank For Pharmacology An Introduction 6th Edition HitnerDocument24 pagesTest Bank For Pharmacology An Introduction 6th Edition HitnerAndrewHerreraqpgz100% (38)

- DiscussionDocument8 pagesDiscussionChai MichelleNo ratings yet

- Drug Design: Prepared By: DR Mazlin Mohideen B.Pharm Tech, FPHS, Unikl-RcmpDocument22 pagesDrug Design: Prepared By: DR Mazlin Mohideen B.Pharm Tech, FPHS, Unikl-RcmpYana QisNo ratings yet

- Cfaname Tertname CustnameDocument30 pagesCfaname Tertname CustnameAshish GuptaNo ratings yet

- 10Document14 pages10Women 68No ratings yet