Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

37 viewsChurch History: Studies in Christianity and Culture

Church History: Studies in Christianity and Culture

Uploaded by

Moldovan RaduThis review summarizes Amos Megged's book "Exporting the Catholic Reformation: Local Religion in Early-Colonial Mexico". The book examines how European Catholic missionaries attempted to replace the native religions of central Mexico with Spanish Catholicism between the 16th and 17th centuries. It focuses on the process of negotiation, compromise and accommodation between the missionaries and native populations. While providing useful local details, the book does not significantly advance overall analyses of the Catholic Reformation or cultural history of the missionary efforts. It remains focused on the specific challenges faced by missionaries in transforming an entire culture.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- The Intentionality of Sensation: A Grammatical FeatureDocument21 pagesThe Intentionality of Sensation: A Grammatical Featureapi-26004537No ratings yet

- The Old Religion in a New World: The History of North American ChristianityFrom EverandThe Old Religion in a New World: The History of North American ChristianityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (19)

- The Mexican Reformation: Catholic Pluralism, Enlightenment Religion, and the Iglesia de Jesus Movement in Benito Juarez’s Mexico (1859–72)From EverandThe Mexican Reformation: Catholic Pluralism, Enlightenment Religion, and the Iglesia de Jesus Movement in Benito Juarez’s Mexico (1859–72)No ratings yet

- Introduction to the History of Christianity in the United StatesFrom EverandIntroduction to the History of Christianity in the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Moral RelativismDocument11 pagesMoral RelativismperpetualdreamerNo ratings yet

- Varieties of PositioningDocument15 pagesVarieties of PositioningbendevaneNo ratings yet

- Change Management at ICICIDocument10 pagesChange Management at ICICIneha444100% (1)

- Syntax by George YuleDocument3 pagesSyntax by George Yulevelmar lumantaoNo ratings yet

- CENTRAL AMERICA-Pentecostals 3 - September JLRDocument11 pagesCENTRAL AMERICA-Pentecostals 3 - September JLRJosé Luis RochaNo ratings yet

- The Future of Christian Learning: An Evangelical and Catholic DialogueFrom EverandThe Future of Christian Learning: An Evangelical and Catholic DialogueRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Callahan Franco New Spain PDFDocument14 pagesCallahan Franco New Spain PDFgregalonsoNo ratings yet

- Solidarity with the World: Charles Taylor and Hans Urs von Balthasar on Faith, Modernity, and Catholic MissionFrom EverandSolidarity with the World: Charles Taylor and Hans Urs von Balthasar on Faith, Modernity, and Catholic MissionNo ratings yet

- Church Planting in the Secular West: Learning from the European ExperienceFrom EverandChurch Planting in the Secular West: Learning from the European ExperienceNo ratings yet

- Valentina Napoiltano PDFDocument17 pagesValentina Napoiltano PDFEstêvão BarrosNo ratings yet

- New Age-The Working Group On New Religious Movements in The VaticanDocument29 pagesNew Age-The Working Group On New Religious Movements in The VaticanFrancis LoboNo ratings yet

- Where Are the Poor?: A Comparison of the Ecclesial Base Communities and Pentecostalism—A Case Study in Cuernavaca, MexicoFrom EverandWhere Are the Poor?: A Comparison of the Ecclesial Base Communities and Pentecostalism—A Case Study in Cuernavaca, MexicoNo ratings yet

- Reseña Gabriela Ramos - Kenneth Mills. Idolatry and Its Enemies. Colonial Andean Religion and Extirpation 1640-1750Document4 pagesReseña Gabriela Ramos - Kenneth Mills. Idolatry and Its Enemies. Colonial Andean Religion and Extirpation 1640-1750Lucila IglesiasNo ratings yet

- Divine Likeness: Toward a Trinitarian Anthropology of the FamilyFrom EverandDivine Likeness: Toward a Trinitarian Anthropology of the FamilyRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Culture, Inculturation, and Theologians ReviewDocument3 pagesCulture, Inculturation, and Theologians ReviewEvangelos ThianiNo ratings yet

- Contextual Scripture Engagement and Transcultural Ministry by Rene Padilla: WCIDJ Fall 2013Document6 pagesContextual Scripture Engagement and Transcultural Ministry by Rene Padilla: WCIDJ Fall 2013William Carey International University PressNo ratings yet

- Revivalism and Social Reform: American Protestantism on the Eve of the Civil WarFrom EverandRevivalism and Social Reform: American Protestantism on the Eve of the Civil WarNo ratings yet

- Hidden Histories in the United Church of Christ 2From EverandHidden Histories in the United Church of Christ 2Barbara Brown ZikmundNo ratings yet

- Hidden Histories in the United Church of ChristFrom EverandHidden Histories in the United Church of ChristBarbara Brown ZikmundNo ratings yet

- Seeking Shalom: The Journey to Right Relationship between Catholics and JewsFrom EverandSeeking Shalom: The Journey to Right Relationship between Catholics and JewsNo ratings yet

- In Search of Christ in Latin America: From Colonial Image to Liberating SaviorFrom EverandIn Search of Christ in Latin America: From Colonial Image to Liberating SaviorNo ratings yet

- Dominicana FriarsbookshelfDocument27 pagesDominicana FriarsbookshelfCharles MorrisonNo ratings yet

- Introducing World Christianity PDFDocument4 pagesIntroducing World Christianity PDFEsteban Rozo0% (1)

- Justo Luis Gonzalez Was Born On August 9Document6 pagesJusto Luis Gonzalez Was Born On August 9Bryan FuentesNo ratings yet

- Lesson 5 The Sacramental Life of Early Christian CommunitieDocument15 pagesLesson 5 The Sacramental Life of Early Christian CommunitieHaydee FelicenNo ratings yet

- Transforming Faith Communities: A Comparative Study of Radical Christianity in Sixteenth-Century Anabaptism and Late Twentieth-Century Latin AmericaFrom EverandTransforming Faith Communities: A Comparative Study of Radical Christianity in Sixteenth-Century Anabaptism and Late Twentieth-Century Latin AmericaNo ratings yet

- Lut 31 1 DieterDocument28 pagesLut 31 1 DieterYosueNo ratings yet

- The Practice of Piety: Puritan Devotional Disciplines in Seventeenth-Century New EnglandFrom EverandThe Practice of Piety: Puritan Devotional Disciplines in Seventeenth-Century New EnglandNo ratings yet

- How the Catholic Church Built Western CivilizationFrom EverandHow the Catholic Church Built Western CivilizationRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (68)

- Catholic University of America Press The Catholic Historical ReviewDocument25 pagesCatholic University of America Press The Catholic Historical ReviewLucasNo ratings yet

- Beyond the Borders of Baptism: Catholicity, Allegiances, and Lived IdentitiesFrom EverandBeyond the Borders of Baptism: Catholicity, Allegiances, and Lived IdentitiesNo ratings yet

- BOOK REVIEW. Lost Christianity. Bonon WilhelmDocument5 pagesBOOK REVIEW. Lost Christianity. Bonon WilhelmWilhelm Bautista Boñon OPNo ratings yet

- 4.+Johnson+Final+Typeset UPLOAD+VERSION Correct+PaginationDocument27 pages4.+Johnson+Final+Typeset UPLOAD+VERSION Correct+PaginationYvan MartinNo ratings yet

- Nadams,+19800611 35 264-286Document23 pagesNadams,+19800611 35 264-286RajanNo ratings yet

- Gooren CCR Latin America Pneuma 34 2 2012Document23 pagesGooren CCR Latin America Pneuma 34 2 2012reinaldo.espinoNo ratings yet

- Catholic Modern: The Challenge of Totalitarianism and the Remaking of the ChurchFrom EverandCatholic Modern: The Challenge of Totalitarianism and the Remaking of the ChurchRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- A History of Christian Thought Volume II: From Augustine to the Eve of the ReformationFrom EverandA History of Christian Thought Volume II: From Augustine to the Eve of the ReformationNo ratings yet

- Church History Studies in Christianity and CultureDocument3 pagesChurch History Studies in Christianity and CultureAlbert R HinkleNo ratings yet

- European Spirituality?: Jan KerkhofsDocument9 pagesEuropean Spirituality?: Jan KerkhofsDeepthi ChoragudiNo ratings yet

- Global Migration and Christian Faith: Implications for Identity and MissionFrom EverandGlobal Migration and Christian Faith: Implications for Identity and MissionNo ratings yet

- Book Reviews: Religions in The Modern World: Traditions and Transformations, 3rd EditionDocument3 pagesBook Reviews: Religions in The Modern World: Traditions and Transformations, 3rd EditionMario BaghosNo ratings yet

- The Ransom of the Soul: Afterlife and Wealth in Early Western ChristianityFrom EverandThe Ransom of the Soul: Afterlife and Wealth in Early Western ChristianityRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (13)

- Book Review Shrikant JMJDocument3 pagesBook Review Shrikant JMJVipin MasihNo ratings yet

- Community Among The Brethren (Brethren Life and Thought, 1 No 1 Aut 1955, P 63-76) - Joseph B. MowDocument15 pagesCommunity Among The Brethren (Brethren Life and Thought, 1 No 1 Aut 1955, P 63-76) - Joseph B. MowlimagoncalvesNo ratings yet

- A History of Christian Thought Volume III: From the Protestant Reformation to the Twentieth CenturyFrom EverandA History of Christian Thought Volume III: From the Protestant Reformation to the Twentieth CenturyNo ratings yet

- One World or Many: The Impact of Globalisation on MissionFrom EverandOne World or Many: The Impact of Globalisation on MissionRichard TipladyNo ratings yet

- History of Christianity Research Paper TopicsDocument7 pagesHistory of Christianity Research Paper Topicsfys5ehgs100% (1)

- Continental Ambitions: Roman Catholics in North America: The Colonial ExperienceFrom EverandContinental Ambitions: Roman Catholics in North America: The Colonial ExperienceRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- A Living Tradition: Catholic Social Doctrine and Holy See DiplomacyFrom EverandA Living Tradition: Catholic Social Doctrine and Holy See DiplomacyNo ratings yet

- God, The Trinity, and Latin Ameriea TodayDocument18 pagesGod, The Trinity, and Latin Ameriea TodayPadre Luciano Couto, ccnNo ratings yet

- Carpenter-Popular ChristianityDocument17 pagesCarpenter-Popular ChristianityacapboscqNo ratings yet

- Gods of The AndesDocument3 pagesGods of The AndesSebastian Davis100% (1)

- Reinventing American Protestantism: Christianity in the New MillenniumFrom EverandReinventing American Protestantism: Christianity in the New MillenniumRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Mcnally 2000Document27 pagesMcnally 2000Osheen SharmaNo ratings yet

- Marty 1993Document44 pagesMarty 1993Vicky IuornoNo ratings yet

- Between: Contextual Evangelization in Latin America: Accommodation and ConfrontationDocument10 pagesBetween: Contextual Evangelization in Latin America: Accommodation and ConfrontationMoldovan RaduNo ratings yet

- Carozza Latin America HRDocument33 pagesCarozza Latin America HRMoldovan RaduNo ratings yet

- Invasion The Maya at War 1520s 1540s inDocument54 pagesInvasion The Maya at War 1520s 1540s inMoldovan RaduNo ratings yet

- The Representation of The Spanish ConqueDocument87 pagesThe Representation of The Spanish ConqueMoldovan RaduNo ratings yet

- Catholic University of America Press Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To The Catholic Historical ReviewDocument3 pagesCatholic University of America Press Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To The Catholic Historical ReviewMoldovan RaduNo ratings yet

- America S Birth Certificate The Oldest GDocument69 pagesAmerica S Birth Certificate The Oldest GMoldovan RaduNo ratings yet

- CarteDocument50 pagesCarteMoldovan RaduNo ratings yet

- Alone Before God: The Religious Origins of Modernity in MexicoDocument4 pagesAlone Before God: The Religious Origins of Modernity in MexicoMoldovan RaduNo ratings yet

- Arjun Appadurai - Cultural Diversity A Conceptual PlatformDocument8 pagesArjun Appadurai - Cultural Diversity A Conceptual PlatformFelipe GibsonNo ratings yet

- Gorgolini, Pietro - The Fascist Movement in Italian LifeDocument234 pagesGorgolini, Pietro - The Fascist Movement in Italian Lifenonamedesire555100% (1)

- Regenerating Digbeth - A Way ForwardDocument34 pagesRegenerating Digbeth - A Way ForwardgetgoodNo ratings yet

- Cagayan State UniversityDocument6 pagesCagayan State UniversityJohnny AbadNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan-2Document5 pagesLesson Plan-2api-464424894No ratings yet

- Mijikenda Ethnoornithology: A Dictionary and Notes (Draft)Document29 pagesMijikenda Ethnoornithology: A Dictionary and Notes (Draft)Martin WalshNo ratings yet

- Blooms Revised Taxonomy For Cognitive Affective and Psychomotor DevelopmentDocument4 pagesBlooms Revised Taxonomy For Cognitive Affective and Psychomotor DevelopmentԱբրենիկա ՖերլինNo ratings yet

- JSRNC Final)Document160 pagesJSRNC Final)Robin M. WrightNo ratings yet

- French Anthropology in 1800Document18 pagesFrench Anthropology in 1800Marcio GoldmanNo ratings yet

- Arthur Penty - Communism and AlternativeDocument60 pagesArthur Penty - Communism and AlternativeSteve BorgeltNo ratings yet

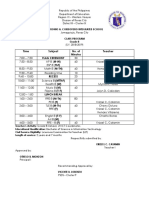

- Grade 8 Class ProgramDocument1 pageGrade 8 Class ProgramKRIZZEL CATAMIN100% (1)

- Case Reflection Scope TrialDocument4 pagesCase Reflection Scope TrialMikey CupinNo ratings yet

- ENGLISH 7th GradeDocument20 pagesENGLISH 7th GradeSofia Macarena AcuñaNo ratings yet

- Cosmic Wealth Ebook PDFDocument119 pagesCosmic Wealth Ebook PDFeva100% (1)

- Running Head: International Marketing StrategyDocument7 pagesRunning Head: International Marketing StrategyHassan SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- Zalewski, Pat - Secret Inner Order Rituals of The Golden DawnDocument181 pagesZalewski, Pat - Secret Inner Order Rituals of The Golden Dawnnikola tesla100% (9)

- Effective Approach To HindusDocument9 pagesEffective Approach To HindusMeera ShresthaNo ratings yet

- 57400679Document22 pages57400679aaaageeNo ratings yet

- Capitalism Communism Socialism DebateDocument28 pagesCapitalism Communism Socialism DebateMr. Graham Long100% (1)

- New Ad Case StudiesDocument6 pagesNew Ad Case StudiesPraveen KadarakoppaNo ratings yet

- Noun 2Document2 pagesNoun 2Sravani AkurathiNo ratings yet

- Department of Education Kidapawan City Division Daily Lesson Log in Math 8 Quarter 4, Week 1 Date: - I - ObjectivesDocument2 pagesDepartment of Education Kidapawan City Division Daily Lesson Log in Math 8 Quarter 4, Week 1 Date: - I - ObjectivesCristopher MusicoNo ratings yet

- Consumer Behaviour Unit - 2 PDFDocument22 pagesConsumer Behaviour Unit - 2 PDFPrashant TripathiNo ratings yet

- Gellner Civilsociety2021Document9 pagesGellner Civilsociety2021TPr Hj Nik KhusairieNo ratings yet

- Making Sense of Discourse AnalysisDocument24 pagesMaking Sense of Discourse AnalysisYuda BrilyanNo ratings yet

Church History: Studies in Christianity and Culture

Church History: Studies in Christianity and Culture

Uploaded by

Moldovan Radu0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

37 views3 pagesThis review summarizes Amos Megged's book "Exporting the Catholic Reformation: Local Religion in Early-Colonial Mexico". The book examines how European Catholic missionaries attempted to replace the native religions of central Mexico with Spanish Catholicism between the 16th and 17th centuries. It focuses on the process of negotiation, compromise and accommodation between the missionaries and native populations. While providing useful local details, the book does not significantly advance overall analyses of the Catholic Reformation or cultural history of the missionary efforts. It remains focused on the specific challenges faced by missionaries in transforming an entire culture.

Original Description:

buna

Original Title

3170188

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis review summarizes Amos Megged's book "Exporting the Catholic Reformation: Local Religion in Early-Colonial Mexico". The book examines how European Catholic missionaries attempted to replace the native religions of central Mexico with Spanish Catholicism between the 16th and 17th centuries. It focuses on the process of negotiation, compromise and accommodation between the missionaries and native populations. While providing useful local details, the book does not significantly advance overall analyses of the Catholic Reformation or cultural history of the missionary efforts. It remains focused on the specific challenges faced by missionaries in transforming an entire culture.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

37 views3 pagesChurch History: Studies in Christianity and Culture

Church History: Studies in Christianity and Culture

Uploaded by

Moldovan RaduThis review summarizes Amos Megged's book "Exporting the Catholic Reformation: Local Religion in Early-Colonial Mexico". The book examines how European Catholic missionaries attempted to replace the native religions of central Mexico with Spanish Catholicism between the 16th and 17th centuries. It focuses on the process of negotiation, compromise and accommodation between the missionaries and native populations. While providing useful local details, the book does not significantly advance overall analyses of the Catholic Reformation or cultural history of the missionary efforts. It remains focused on the specific challenges faced by missionaries in transforming an entire culture.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 3

Church History: Studies in

Christianity and Culture

http://journals.cambridge.org/CHH

Additional services for Church

History:

Studies in Christianity and Culture:

Email alerts: Click here

Subscriptions: Click here

Commercial reprints: Click here

Terms of use : Click here

Exporting the Catholic Reformation: Local

Religion in Early-Colonial Mexico. By Amos

Megged. Cultures, Beliefs and Traditions 2.

Leiden: Brill, 1996. 191 pp. \$71.50 cloth.

Carlos M. N. Eire

Church History: Studies in Christianity and Culture / Volume 68 / Issue 01 / March 1999,

pp 239 - 240

DOI: 10.2307/3170188, Published online: 28 July 2009

Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/

abstract_S0009640700071833

How to cite this article:

Carlos M. N. Eire (1999). Church History: Studies in Christianity and Culture,

68, pp 239-240 doi:10.2307/3170188

Request Permissions : Click here

Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/CHH, IP address: 147.188.128.74 on 09 Jun 2015

BOOK REVIEWS AND NOTES 239

Exporting the Catholic Reformation: Local Religion in Early-Colonial Mexico.

By Amos Megged. Cultures, Beliefs and Traditions 2. Leiden: Brill, 1996.

191 pp. $71.50 cloth.

In the author's own words, the purpose of this book is "to offer a fresh

cultural interpretation" of the impact of European Catholicism on the reli-

gious life of the native peoples of southern Mexico in the sixteenth and

seventeenth centuries (1). The "fresh cultural interpretation" boils down to

this: the conversion of the natives was a process of negotiation, compromise,

and accommodation. Scholars who are familiar with the history of the

Christianization of the Americas might call into question the claim that this is

really a "fresh" interpretation. Historians of culture might also raise the same

question. But the ultimate value of this book, fortunately, does not rest solely

on the author's claims to innovation, or on the question of whether or not

these claims could stand up to scrutiny. This is a truly fine local study of the

ways in which European clerics sought to replace the religion of the Central

American natives with their own Spanish Catholicism.

Megged's study focuses on southeastern New Spain, covering an area now

shared by the nation of Guatemala and the Mexican state of Chiapas. The

book is divided into five chapters, with an introduction and an epilogue. The

introduction contains a brief outline of the book and its aims, as well as a

compact discussion of the relevant interpretative literature. At the outset,

Megged makes it known that he has read widely, not just in the history of

colonization, but also in the history of early modern European religion and

culture. The chapters break down as follows: chapter 1 analyzes now the

Catholic clerics interpreted the religion of the natives; chapter 2 outlines the

various administrative and cultural obstacles faced by the missionaries in

transplanting Tridentine Catholicism to a remote corner of Mexico; chapter 3

focuses on some of the principal ways in which Catholic ritual became

institutionalized at the local level by the missionaries; chapter 4 probes the

missionaries' collective mentality by scrutinizing their own definitions of the

concept of "idolatry," and their attitudes towards the ancestral religion of the

natives; chapter 5 is a brief survey of some of the most salient examples of

native resistance to the Spaniards' missionary efforts.

Megged's study is based on a very wide range of archival and printed

sources from both sides of the Atlantic: Spain, the Vatican, Mexico, Guatemala,

and the United States. The documents themselves also range impressively,

and include such disparate sources as legal court records, visitation reports by

bishops, missionaries' letters, teaching manuals, catechisms, printed treatises,

and dictionaries.

When all is said and done, this book offers up much in the way of detail,

and thus expands our knowledge of the way in which religion was trans-

formed on the local level in one part of New Spain. As far as the larger picture

is concerned, though, this book does not make great analytical strides for-

ward. This is not so much a book about the exportation of the Catholic

Reformation as it is a book about the transformation of native religion; nor is

this as much a cultural history of the Spanish missionary effort as it is a

narrative of the nuts and bolts of a forced mass conversion, told largely from

the documents that were left behind by the missionaries. As the title indicates,

Amos Megged also wants to make much here of the fact that this was not

merely Spanish Catholicism that was being exported, but rather that of

Tridentine Reformation, which was not only more vigorous, but also much

240 CHURCH HISTORY

more inclined towards uniformity and homogeneity at the expense of local

diversity. Exporting Catholicism was a difficult enterprise to begin with, but

exporting Tridentine Catholicism was an even harder task, Megged reminds

us repeatedly. In the end, though, Megged cannot really deal so much with the

Catholic Reformation as with the specific local difficulties faced by clerics who

happened to belong to the Tridentine church. Though he makes valiant efforts

to set his narrative and analysis against the larger background of what was

transpiring in Spain and Europe, his focus remains fixed on the distinctive

tasks faced by Catholic clerics in a different world, where there was no corrupt

church to "reform," but rather an entire culture to transform.

Ultimately, Megged seems to offer an ambivalent conclusion. After reading

about the myriad ways in which the Tridentine missionaries and the natives

negotiated a kind of religion that was as local and native as the Catholic

Church would allow, we are told that the native traditions were ultimately

"crushed under the wheel of conversion" (160), and are offered as an example

of this crushing process a hybrid Christian/native ritual from present-day

Oxchuc. (A similar ahistorical leap from the sixteenth to the twentieth century

is made earlier, on 73, also as a means of identifying the hybridization of

religion in this area.) Whether this anachronistic example points to a negoti-

ated religion or a "crushed" religion remains unclear. Also unclear is Megged's

assessment of the relation of this process to the Catholic Reformation.

This book should naturally prove of greatest interest to historians of

colonial Central America and historians of missions, for whom it should prove

quite useful, perhaps even enlightening owing to its wealth of details, and its

firm anchoring in primary sources. Historians of the Catholic Reformation,

too, might want to dive into this rich collection of locally specific facts, all of

which ultimately relate to the expansion of the Catholic Church in the early

modern era.

Finally, a relatively small but significant point needs to be raised: this book

is full of typographical errors. As someone who has been burned many times

by the negligence of publishers (even to the point of having a book published

with the title misspelled on the spine), this reviewer is wary of calling

attention to production flaws, but in this case the mistakes are glaring enough

to deserve comment. At $71.50, or any price, such carelessness should be

considered an intolerable affront to the author and his readers.

Carlos M. N. Eire

Yale University

Women, Religion, and Social Change in Brazil's Popular Church. By Carol

Ann Drogus. Notre Dame, Ind.: University of Notre Dame Press, 1997. xiv

+ 226 pp. $26.00 cloth.

The historic changes experienced in Latin American Catholicism in the

years following the Second Vatican Council, including the rise of liberation

theology, have drawn the attention of a wide range of scholars. Many studies

have examined the church's institutional changes, especially the growth of

base Christian communities (CEBs), and its activism on behalf of human

rights violations and socioeconomic justice, particularly in places like Brazil,

Chile, and Central America. While a number of observers have noted the

central (often majority) role of women in progressive Catholic projects, so far

few full-length studies have explored the complex and ambivalent relations

You might also like

- The Intentionality of Sensation: A Grammatical FeatureDocument21 pagesThe Intentionality of Sensation: A Grammatical Featureapi-26004537No ratings yet

- The Old Religion in a New World: The History of North American ChristianityFrom EverandThe Old Religion in a New World: The History of North American ChristianityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (19)

- The Mexican Reformation: Catholic Pluralism, Enlightenment Religion, and the Iglesia de Jesus Movement in Benito Juarez’s Mexico (1859–72)From EverandThe Mexican Reformation: Catholic Pluralism, Enlightenment Religion, and the Iglesia de Jesus Movement in Benito Juarez’s Mexico (1859–72)No ratings yet

- Introduction to the History of Christianity in the United StatesFrom EverandIntroduction to the History of Christianity in the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Moral RelativismDocument11 pagesMoral RelativismperpetualdreamerNo ratings yet

- Varieties of PositioningDocument15 pagesVarieties of PositioningbendevaneNo ratings yet

- Change Management at ICICIDocument10 pagesChange Management at ICICIneha444100% (1)

- Syntax by George YuleDocument3 pagesSyntax by George Yulevelmar lumantaoNo ratings yet

- CENTRAL AMERICA-Pentecostals 3 - September JLRDocument11 pagesCENTRAL AMERICA-Pentecostals 3 - September JLRJosé Luis RochaNo ratings yet

- The Future of Christian Learning: An Evangelical and Catholic DialogueFrom EverandThe Future of Christian Learning: An Evangelical and Catholic DialogueRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Callahan Franco New Spain PDFDocument14 pagesCallahan Franco New Spain PDFgregalonsoNo ratings yet

- Solidarity with the World: Charles Taylor and Hans Urs von Balthasar on Faith, Modernity, and Catholic MissionFrom EverandSolidarity with the World: Charles Taylor and Hans Urs von Balthasar on Faith, Modernity, and Catholic MissionNo ratings yet

- Church Planting in the Secular West: Learning from the European ExperienceFrom EverandChurch Planting in the Secular West: Learning from the European ExperienceNo ratings yet

- Valentina Napoiltano PDFDocument17 pagesValentina Napoiltano PDFEstêvão BarrosNo ratings yet

- New Age-The Working Group On New Religious Movements in The VaticanDocument29 pagesNew Age-The Working Group On New Religious Movements in The VaticanFrancis LoboNo ratings yet

- Where Are the Poor?: A Comparison of the Ecclesial Base Communities and Pentecostalism—A Case Study in Cuernavaca, MexicoFrom EverandWhere Are the Poor?: A Comparison of the Ecclesial Base Communities and Pentecostalism—A Case Study in Cuernavaca, MexicoNo ratings yet

- Reseña Gabriela Ramos - Kenneth Mills. Idolatry and Its Enemies. Colonial Andean Religion and Extirpation 1640-1750Document4 pagesReseña Gabriela Ramos - Kenneth Mills. Idolatry and Its Enemies. Colonial Andean Religion and Extirpation 1640-1750Lucila IglesiasNo ratings yet

- Divine Likeness: Toward a Trinitarian Anthropology of the FamilyFrom EverandDivine Likeness: Toward a Trinitarian Anthropology of the FamilyRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Culture, Inculturation, and Theologians ReviewDocument3 pagesCulture, Inculturation, and Theologians ReviewEvangelos ThianiNo ratings yet

- Contextual Scripture Engagement and Transcultural Ministry by Rene Padilla: WCIDJ Fall 2013Document6 pagesContextual Scripture Engagement and Transcultural Ministry by Rene Padilla: WCIDJ Fall 2013William Carey International University PressNo ratings yet

- Revivalism and Social Reform: American Protestantism on the Eve of the Civil WarFrom EverandRevivalism and Social Reform: American Protestantism on the Eve of the Civil WarNo ratings yet

- Hidden Histories in the United Church of Christ 2From EverandHidden Histories in the United Church of Christ 2Barbara Brown ZikmundNo ratings yet

- Hidden Histories in the United Church of ChristFrom EverandHidden Histories in the United Church of ChristBarbara Brown ZikmundNo ratings yet

- Seeking Shalom: The Journey to Right Relationship between Catholics and JewsFrom EverandSeeking Shalom: The Journey to Right Relationship between Catholics and JewsNo ratings yet

- In Search of Christ in Latin America: From Colonial Image to Liberating SaviorFrom EverandIn Search of Christ in Latin America: From Colonial Image to Liberating SaviorNo ratings yet

- Dominicana FriarsbookshelfDocument27 pagesDominicana FriarsbookshelfCharles MorrisonNo ratings yet

- Introducing World Christianity PDFDocument4 pagesIntroducing World Christianity PDFEsteban Rozo0% (1)

- Justo Luis Gonzalez Was Born On August 9Document6 pagesJusto Luis Gonzalez Was Born On August 9Bryan FuentesNo ratings yet

- Lesson 5 The Sacramental Life of Early Christian CommunitieDocument15 pagesLesson 5 The Sacramental Life of Early Christian CommunitieHaydee FelicenNo ratings yet

- Transforming Faith Communities: A Comparative Study of Radical Christianity in Sixteenth-Century Anabaptism and Late Twentieth-Century Latin AmericaFrom EverandTransforming Faith Communities: A Comparative Study of Radical Christianity in Sixteenth-Century Anabaptism and Late Twentieth-Century Latin AmericaNo ratings yet

- Lut 31 1 DieterDocument28 pagesLut 31 1 DieterYosueNo ratings yet

- The Practice of Piety: Puritan Devotional Disciplines in Seventeenth-Century New EnglandFrom EverandThe Practice of Piety: Puritan Devotional Disciplines in Seventeenth-Century New EnglandNo ratings yet

- How the Catholic Church Built Western CivilizationFrom EverandHow the Catholic Church Built Western CivilizationRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (68)

- Catholic University of America Press The Catholic Historical ReviewDocument25 pagesCatholic University of America Press The Catholic Historical ReviewLucasNo ratings yet

- Beyond the Borders of Baptism: Catholicity, Allegiances, and Lived IdentitiesFrom EverandBeyond the Borders of Baptism: Catholicity, Allegiances, and Lived IdentitiesNo ratings yet

- BOOK REVIEW. Lost Christianity. Bonon WilhelmDocument5 pagesBOOK REVIEW. Lost Christianity. Bonon WilhelmWilhelm Bautista Boñon OPNo ratings yet

- 4.+Johnson+Final+Typeset UPLOAD+VERSION Correct+PaginationDocument27 pages4.+Johnson+Final+Typeset UPLOAD+VERSION Correct+PaginationYvan MartinNo ratings yet

- Nadams,+19800611 35 264-286Document23 pagesNadams,+19800611 35 264-286RajanNo ratings yet

- Gooren CCR Latin America Pneuma 34 2 2012Document23 pagesGooren CCR Latin America Pneuma 34 2 2012reinaldo.espinoNo ratings yet

- Catholic Modern: The Challenge of Totalitarianism and the Remaking of the ChurchFrom EverandCatholic Modern: The Challenge of Totalitarianism and the Remaking of the ChurchRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- A History of Christian Thought Volume II: From Augustine to the Eve of the ReformationFrom EverandA History of Christian Thought Volume II: From Augustine to the Eve of the ReformationNo ratings yet

- Church History Studies in Christianity and CultureDocument3 pagesChurch History Studies in Christianity and CultureAlbert R HinkleNo ratings yet

- European Spirituality?: Jan KerkhofsDocument9 pagesEuropean Spirituality?: Jan KerkhofsDeepthi ChoragudiNo ratings yet

- Global Migration and Christian Faith: Implications for Identity and MissionFrom EverandGlobal Migration and Christian Faith: Implications for Identity and MissionNo ratings yet

- Book Reviews: Religions in The Modern World: Traditions and Transformations, 3rd EditionDocument3 pagesBook Reviews: Religions in The Modern World: Traditions and Transformations, 3rd EditionMario BaghosNo ratings yet

- The Ransom of the Soul: Afterlife and Wealth in Early Western ChristianityFrom EverandThe Ransom of the Soul: Afterlife and Wealth in Early Western ChristianityRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (13)

- Book Review Shrikant JMJDocument3 pagesBook Review Shrikant JMJVipin MasihNo ratings yet

- Community Among The Brethren (Brethren Life and Thought, 1 No 1 Aut 1955, P 63-76) - Joseph B. MowDocument15 pagesCommunity Among The Brethren (Brethren Life and Thought, 1 No 1 Aut 1955, P 63-76) - Joseph B. MowlimagoncalvesNo ratings yet

- A History of Christian Thought Volume III: From the Protestant Reformation to the Twentieth CenturyFrom EverandA History of Christian Thought Volume III: From the Protestant Reformation to the Twentieth CenturyNo ratings yet

- One World or Many: The Impact of Globalisation on MissionFrom EverandOne World or Many: The Impact of Globalisation on MissionRichard TipladyNo ratings yet

- History of Christianity Research Paper TopicsDocument7 pagesHistory of Christianity Research Paper Topicsfys5ehgs100% (1)

- Continental Ambitions: Roman Catholics in North America: The Colonial ExperienceFrom EverandContinental Ambitions: Roman Catholics in North America: The Colonial ExperienceRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- A Living Tradition: Catholic Social Doctrine and Holy See DiplomacyFrom EverandA Living Tradition: Catholic Social Doctrine and Holy See DiplomacyNo ratings yet

- God, The Trinity, and Latin Ameriea TodayDocument18 pagesGod, The Trinity, and Latin Ameriea TodayPadre Luciano Couto, ccnNo ratings yet

- Carpenter-Popular ChristianityDocument17 pagesCarpenter-Popular ChristianityacapboscqNo ratings yet

- Gods of The AndesDocument3 pagesGods of The AndesSebastian Davis100% (1)

- Reinventing American Protestantism: Christianity in the New MillenniumFrom EverandReinventing American Protestantism: Christianity in the New MillenniumRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Mcnally 2000Document27 pagesMcnally 2000Osheen SharmaNo ratings yet

- Marty 1993Document44 pagesMarty 1993Vicky IuornoNo ratings yet

- Between: Contextual Evangelization in Latin America: Accommodation and ConfrontationDocument10 pagesBetween: Contextual Evangelization in Latin America: Accommodation and ConfrontationMoldovan RaduNo ratings yet

- Carozza Latin America HRDocument33 pagesCarozza Latin America HRMoldovan RaduNo ratings yet

- Invasion The Maya at War 1520s 1540s inDocument54 pagesInvasion The Maya at War 1520s 1540s inMoldovan RaduNo ratings yet

- The Representation of The Spanish ConqueDocument87 pagesThe Representation of The Spanish ConqueMoldovan RaduNo ratings yet

- Catholic University of America Press Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To The Catholic Historical ReviewDocument3 pagesCatholic University of America Press Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To The Catholic Historical ReviewMoldovan RaduNo ratings yet

- America S Birth Certificate The Oldest GDocument69 pagesAmerica S Birth Certificate The Oldest GMoldovan RaduNo ratings yet

- CarteDocument50 pagesCarteMoldovan RaduNo ratings yet

- Alone Before God: The Religious Origins of Modernity in MexicoDocument4 pagesAlone Before God: The Religious Origins of Modernity in MexicoMoldovan RaduNo ratings yet

- Arjun Appadurai - Cultural Diversity A Conceptual PlatformDocument8 pagesArjun Appadurai - Cultural Diversity A Conceptual PlatformFelipe GibsonNo ratings yet

- Gorgolini, Pietro - The Fascist Movement in Italian LifeDocument234 pagesGorgolini, Pietro - The Fascist Movement in Italian Lifenonamedesire555100% (1)

- Regenerating Digbeth - A Way ForwardDocument34 pagesRegenerating Digbeth - A Way ForwardgetgoodNo ratings yet

- Cagayan State UniversityDocument6 pagesCagayan State UniversityJohnny AbadNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan-2Document5 pagesLesson Plan-2api-464424894No ratings yet

- Mijikenda Ethnoornithology: A Dictionary and Notes (Draft)Document29 pagesMijikenda Ethnoornithology: A Dictionary and Notes (Draft)Martin WalshNo ratings yet

- Blooms Revised Taxonomy For Cognitive Affective and Psychomotor DevelopmentDocument4 pagesBlooms Revised Taxonomy For Cognitive Affective and Psychomotor DevelopmentԱբրենիկա ՖերլինNo ratings yet

- JSRNC Final)Document160 pagesJSRNC Final)Robin M. WrightNo ratings yet

- French Anthropology in 1800Document18 pagesFrench Anthropology in 1800Marcio GoldmanNo ratings yet

- Arthur Penty - Communism and AlternativeDocument60 pagesArthur Penty - Communism and AlternativeSteve BorgeltNo ratings yet

- Grade 8 Class ProgramDocument1 pageGrade 8 Class ProgramKRIZZEL CATAMIN100% (1)

- Case Reflection Scope TrialDocument4 pagesCase Reflection Scope TrialMikey CupinNo ratings yet

- ENGLISH 7th GradeDocument20 pagesENGLISH 7th GradeSofia Macarena AcuñaNo ratings yet

- Cosmic Wealth Ebook PDFDocument119 pagesCosmic Wealth Ebook PDFeva100% (1)

- Running Head: International Marketing StrategyDocument7 pagesRunning Head: International Marketing StrategyHassan SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- Zalewski, Pat - Secret Inner Order Rituals of The Golden DawnDocument181 pagesZalewski, Pat - Secret Inner Order Rituals of The Golden Dawnnikola tesla100% (9)

- Effective Approach To HindusDocument9 pagesEffective Approach To HindusMeera ShresthaNo ratings yet

- 57400679Document22 pages57400679aaaageeNo ratings yet

- Capitalism Communism Socialism DebateDocument28 pagesCapitalism Communism Socialism DebateMr. Graham Long100% (1)

- New Ad Case StudiesDocument6 pagesNew Ad Case StudiesPraveen KadarakoppaNo ratings yet

- Noun 2Document2 pagesNoun 2Sravani AkurathiNo ratings yet

- Department of Education Kidapawan City Division Daily Lesson Log in Math 8 Quarter 4, Week 1 Date: - I - ObjectivesDocument2 pagesDepartment of Education Kidapawan City Division Daily Lesson Log in Math 8 Quarter 4, Week 1 Date: - I - ObjectivesCristopher MusicoNo ratings yet

- Consumer Behaviour Unit - 2 PDFDocument22 pagesConsumer Behaviour Unit - 2 PDFPrashant TripathiNo ratings yet

- Gellner Civilsociety2021Document9 pagesGellner Civilsociety2021TPr Hj Nik KhusairieNo ratings yet

- Making Sense of Discourse AnalysisDocument24 pagesMaking Sense of Discourse AnalysisYuda BrilyanNo ratings yet