Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Hendrix 2006

Hendrix 2006

Uploaded by

happyOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Hendrix 2006

Hendrix 2006

Uploaded by

happyCopyright:

Available Formats

This material is protected by U.S. copyright law. Unauthorized reproduction is prohibited.

To purchase quantity reprints,

please e-mail reprints@ons.org or to request permission to reproduce multiple copies, please e-mail pubpermissions@ons.org.

Informal Caregiver Training on Home Care

and Cancer Symptom Management

Prior to Hospital Discharge: A Feasibility Study

Downloaded on 08 27 2020. Single-user license only. Copyright 2020 by the Oncology Nursing Society. For permission to post online, reprint, adapt, or reuse, please email pubpermissions@ons.org. ONS reserves all rights.

Cristina C. Hendrix, DNS, APRN-BC, GNP, FNP, and Charlene Ray, BSN, RN

Purpose/Objectives: To determine the feasibility of individualized Key Points . . .

caregiver training for home care and symptom management con-

ducted at the bedside of older patients with cancer prior to hospital

➤ When given an opportunity for training on cancer symptom

discharge.

Design: Pilot study. management prior to hospital discharge, informal caregivers

Setting: The Extended Care Rehabilitation Center at the Durham were very interested in participating.

Veterans Affairs Medical Center in North Carolina. ➤ Individualized bedside training with an opportunity to prac-

Sample: 7 female informal caregivers with a mean age of 56 (range = tice skills increased confidence among informal caregivers

26–76). More than half were African American. Most commonly, caregiv- that they would be able to help their loved ones manage their

ers were spouses of the patients with cancer.

symptoms at home.

Methods: Individualized and experiential training on home care and

cancer symptom management was conducted at the bedside of patients ➤ The flexibility of when to conduct the training proved to be

before hospital discharge. Caregiver demographic data were collected. crucial when soliciting participation from informal caregivers.

An informal interview at the end of the training asked about the useful-

ness of the training in preparing for home caregiving.

Main Research Variables: Feasibility of the training.

Findings: Individualized bedside training to caregivers prior to being (Bandura, 1997), and, in general, informal caregivers’

hospital discharge is feasible. All caregivers noted the relevance of the psychological states already are vulnerable as a consequence

content as well as the approach to the training. of caregiving (Schulz & Beach, 1999; Schulz, Visintainer, &

Conclusions: When given an opportunity for training on symptom Williamson, 1990). Because of the reciprocal and intricate

management and home care, informal caregivers were very interested

relationship in caregiver and patient dyads, when caregivers’

in participating. The individualized approach gave caregivers an op-

portunity to have their particular needs met. The flexibility of when to

psychological health deteriorates, it may have a negative

conduct the training proved to be crucial when soliciting attendance. impact on their ability to provide care, thus adversely af-

The biggest challenge was in recruiting caregiver subjects through fecting patients’ conditions as well (Hodges, Humphris, &

patients with cancer. Macfarlane, 2005).

Implications for Nursing: The impetus now is to look at the effects of The period immediately after hospitalization has been

the training on caregiver-patient variables as well as the cost-effective- found to be one of the most trying times in cancer symptom

ness and sustainability of such an approach to caregiver training. management (Giarelli, McCorkle, & Monturo, 2003; Laizner,

Yost, Barg, & McCorkle, 1993; Weitzner, Jacobsen, Wagner,

Friedland, & Cox, 1999). In addition, the use of emergency

services is common among patients with cancer during the first

B

y 2030, the number of older people with cancer in the two weeks after hospital discharge (Kurtin et al., 1990). One

United States is expected to double (Edwards et al., possible reason is that, in the current healthcare system, many

2002). With shorter hospital stays and cancer treat- patients with cancer still are acutely ill at the point of discharge

ments in ambulatory settings, a concomitant increase will

occur in the number of community-dwelling, informal care-

givers for patients (Andrews, 2001; Aranda & Hayman-White, Cristina C. Hendrix, DNS, APRN-BC, GNP, FNP, is an assistant pro-

2001; Pasacreta & McCorkle, 2000). Symptom management fessor in the School of Nursing at Duke University Medical Center

has been identified as an essential component of effective and a senior fellow at the Duke Center for Aging and Charlene Ray,

home caregiving for older adults with cancer (Steinhauser BSN, RN, is an oncology nurse practitioner student in the School of

et al., 2000). However, most informal caregivers do not feel Nursing at Duke University, both in Durham, NC. This pilot study

confident that they possess the knowledge and skills to care was funded by the P20 National Institute of Nursing Research Tra-

for their loved ones while managing their symptoms at home jectory of Aging and Care Center in the School of Nursing at Duke

(Aranda & Hayman-White; Schumacher et al., 2002; Steele University. (Submitted September 2005. Accepted for publication

& Fitch, 1996; Sutton, Clipp, & Winer, 2000). Low levels of November 16, 2005.)

confidence may negatively affect people’s psychological well- Digital Object Identifier: 10.1188/06.ONF.793-798

ONCOLOGY NURSING FORUM – VOL 33, NO 4, 2006

793

(Laizner et al.); thus, many symptoms still may be unabated. how tasks are performed is useful. Performance exposure al-

Caregiving for older patients with cancer is particularly chal- lows caregivers to execute interventions under the guidance of

lenging because comorbidities complicate the illness process healthcare professionals in an atmosphere that is supportive,

and the number of cancer-related symptoms increases with with constructive feedback (positive appraisal). The goal is to

age (Sutton, Demark-Wahnefried, & Clipp, 2003). Therefore, enable caregivers to experience successful task performance,

formalized training should be offered to family caregivers prior because performance accomplishment is the most influential

to hospital discharge to prepare them for home caregiving, source of efficacy (Bandura, Adams, & Beyer, 1977). In the

especially concerning symptom management. proposed study, interventions for cancer symptom manage-

Nurses always have taken the lead in assisting and edu- ment requiring skills were demonstrated by an expert while

cating informal and family caregivers prior to the hospital caregivers observed (live modeling), and the caregivers then

discharge of their loved ones. Most hospitals embody the performed the interventions while the expert observed (per-

principle that discharge planning should commence at the formance exposure and positive appraisal) until the caregivers

time of admission. However, in reality, nursing practice for were able to complete the tasks successfully (performance

home discharge consists of teaching caregivers in spurts as mastery). When caregivers’ involvement in cancer care was

dictated by nurses’ time and workloads as well as caregivers’ recognized and legitimized through participation in the train-

availability. What frequently occurs in many inpatient settings ing, they gained a possible increase in self-efficacy. In addi-

is that most discharge instructions are given to patients and tion, caregivers could then attend to their own needs along

caregivers on the day of discharge. A review of recent research with those of their patients (Morris & Thomas, 2001).

literature revealed that studies on discharge planning have

been focused mainly on patients in emergency rooms (Chor- Methods

ley, 2005; Ferrari et al., 2005) and surgical patients (Lee &

Bokovoy, 2005; Reynolds, 2002). None was found involving Setting and Sample

older patients with cancer and their family caregivers. Cur- The pilot study was conducted in the Extended Care Re-

rent discharge practices for older patients with cancer may habilitation Center (ECRC) at the Durham Veterans Affairs

be inadequate because many informal caregivers perceive a Medical Center (VAMC) in North Carolina. The ECRC

lack of confidence and preparedness in assuming their role in was targeted because many older patients with cancer stay

home settings, particularly with cancer symptom management there while undergoing induction chemotherapy or radiation

(Hudson, Aranda, & McMurray, 2002; Rose, 1999). therapy. The ECRC has two wards, with more than 30 semi-

The purpose of this article, therefore, is to report the find- private rooms in each ward. Each semiprivate room has two

ings of a feasibility study about formalized caregiver training beds and a curtain, which serves as a partition. Each room

for home care and symptom management prior to patient is equipped with a sink and a bathroom. The researchers

discharge from an inpatient setting. Specifically, the study designed the study to recruit informal caregivers of patients

explored whether informal caregivers were willing to par- newly diagnosed with cancer because they anticipated that

ticipate in one-on-one training at their loved ones’ bedsides these caregivers were the ones who knew the least about

before hospital discharge and whether the caregivers found cancer and its symptoms.

the training useful in increasing their confidence and prepar- Informal caregiver subjects were primary caregivers of

ing them for home caregiving. The study also provided the older veterans, aged 50 and older, who were undergoing in-

researchers an opportunity to pilot test an individualized and duction treatment for cancer in the ECRC and were expected

experiential approach to caregiver training. In the study, the to be discharged after treatment. A primary caregiver was

researchers laid the groundwork for ongoing studies about defined as an individual who lived in the same household as

the effects of individualized bedside training on caregiver the patient and provided the most “hands-on” care. Inclu-

and patient variables such as caregivers’ psychological well- sion criteria for caregiver subjects were being age 18 years

being and self-efficacy and patients’ symptom intensity and or older; able to speak, read, and write English; and able to

distress, as well as their use of emergency services for cancer spend time at the bedsides of their patients with cancer in the

symptoms. Ultimately, the authors plan to investigate the ECRC to participate in the training.

cost-effectiveness and sustainability of such an approach to After the researchers obtained approval from the VAMC

caregiver training. institutional review board, they recruited subjects one at a time

over three months through referrals from the medical direc-

tor of the ECRC. Because the intent of the pilot study was

Conceptual Framework to look at the feasibility of providing training for home care

The conceptual foundation of the study is Bandura’s Self- and cancer symptom management, the medical director only

Efficacy Theory. According to Bandura (1997), self-efficacy referred caregivers of older patients with cancer with planned

is the confidence or belief in your capabilities to organize discharge dates and homecare issues (e.g., limited mobility,

and execute the courses of action required to produce given feeding tubes, wound care) or cancer symptoms (e.g., pain,

outcomes. In the context of cancer caregiving, it is a caregiv- constipation, skin irritation). Thus, caregivers of older patients

er’s confidence that he or she can provide care. Sources of who were asymptomatic and independent in their activities of

self-efficacy include live modeling, performance exposure, daily living were excluded from participation.

positive appraisal, and performance mastery (Bandura, 1986,

1997). In individualized experiential training for caregivers, Procedure

live modeling allows caregivers to observe people who have The ECRC medical director reviewed lists of new patients

mastered skills perform interventions. Because caregivers every Thursday for potential subjects. The principal investiga-

have difficultly visualizing how tasks are achieved, observing tor (PI) communicated with the medical director every Friday

ONCOLOGY NURSING FORUM – VOL 33, NO 4, 2006

794

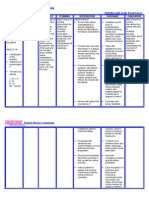

for a list of potential recruits. The PI approached patients dur- Table 1. Cancer Symptom Areas in Each Caregiver Training

ing the second half of their estimated stays in the ECRC. For

example, if a patient was expected to be in the ECRC for three Topic Discussion

months, the PI approached the patient during the second half

Prevention of infection Assessment of caregiver’s knowledge

of his or her estimated length of stay. Therefore, the caregiver

Prevention of infection

training was based on the patient’s condition as close to the Discussion of signs and symptoms of infec-

discharge date as possible. tion

The PI met with each referred patient to explain the study Central line care and dressing change, Foley

and to determine whether he or she had a primary caregiver. catheter care, and wound care, as ap-

When a patient had a primary caregiver, the PI requested plicable

from the patient the caregiver’s telephone number. The PI also

left her contact number so that the caregiver or patient could Pain control Pain assessment

contact the PI with any questions about the study. Guidelines for pain medication

The PI contacted primary informal caregivers by telephone Nonpharmacologic interventions

to determine eligibility, explain the individualized training,

Maintenance of adequate Assessment of the patient’s problem with

and invite participation. Once a caregiver agreed to partici- nutrition nutrition

pate, he or she was asked for a convenient time to have the Guidelines for maintaining or increasing calor-

individualized training. Flexibility was observed in schedul- ic intake

ing: nights and weekends, in addition to days and weekdays, Oral care

were given as options. In addition, mileage reimbursement Tube feeding, if applicable

was provided to participating caregivers.

Each caregiver had a choice to receive the training in one Prevention and management Assessment of patient’s problem with bowel

or two sessions. If the caregiver chose one session, he or she of constipation or diarrhea elimination

was asked to allot at least an entire morning or afternoon. Discussion of strategies that alleviate or pre-

vent constipation or diarrhea

If the caregiver chose two sessions, he or she was asked to

allot at least two hours for the first session. All caregivers Medication regimen related Assessment of medications

were informed that the time allotment was a gross estimate to cancer symptoms Discussion of each medication: purpose and

of the length of the training. All were assured that they side effects

would not be kept longer than the time allotted for each

session but that more than one session might be necessary.

A day before scheduled training, the PI consulted with the

ECRC medical director and staff nurses about the patient’s The training combined didactic teaching and actual per-

condition so that areas covered in the training were specific formance of the skills necessary to carry out homecare pro-

and appropriate. cedures, if any were required. For interventions that required

skills, the PI modeled performance of the interventions. After-

Caregiver Training ward, the caregivers were asked to demonstrate the interven-

Individualized training began after caregivers signed the tions while the PI observed and offered guidance and positive

consent form. The PI, an experienced advanced practice feedback as necessary. For example, in the case of a patient

nurse, conducted the training. The caregivers’ loved ones requiring feeding through a gastrostomy tube, the PI initially

(i.e, patients with cancer) were encouraged to be part of the showed the proper way to inspect and handle the tube, aspirate

training. the feeding solution using a syringe, and flush the tube with

Training started with brief discussion of patient care water after feeding. The PI initially fed the patient while the

needs and cancer symptoms. The training consisted of basic caregiver observed. Midway through the feeding, the caregiver

areas of cancer symptom management as outlined in Table was asked to give the feeding herself while the PI observed

1. Training in other symptom areas was conducted when and gave positive feedback as appropriate. If the patient did not

applicable to a patient’s condition, most commonly helping participate in the training, the PI brought in the contraptions

with dyspnea and fatigue. With each care need or symptom, associated with a gastrostomy tube feeding (e.g., gastrostomy

the discussion focused on nonpharmacologic interventions tube and a 60-cc syringe) and still allowed the caregiver to go

that could be implemented in home settings to assist pa- through the steps of how to give a tube feeding.

tients. When applicable to a particular homecare need or Adequate time was provided for questions and repeated

cancer symptom, teachings on home medications also were caregiver demonstrations of learned materials if requested.

incorporated. Because each caregiver had different learning needs and skills,

The PI ensured that the training was interactive, requiring the caregivers guided the duration of training. Training only

the caregivers, and the patients when present, to interact as concluded when caregivers expressed satisfaction with the

well as to participate in problem solving for specific symp- adequacy of learned materials and confidence in assisting

toms or care needs. The PI focused the training on interven- patients at home. At the end of training, caregivers received a

tions as they applied to patients. For example, for decreased copy of A Manual for Informal Caregivers on Cancer Symp-

appetite, the PI asked the caregiver (or patient) about foods tom Management (Hendrix, 2004), a book developed by the

that the patient loved to eat, then explained how to make them PI that contains a list of nonpharmacologic and supportive

more palatable to the patient. If a patient was a vegetarian, the interventions for cancer symptom management. Using the

discussion focused on maintaining or increasing caloric intake Flesch-Kincaid criteria (Flesch, 1974), the readability of the

using calories from plants and plant products. manual was at the seventh-grade level.

ONCOLOGY NURSING FORUM – VOL 33, NO 4, 2006

795

Data Collection Procedure specific time for the training). All seven participating caregiv-

Data were collected regarding personal characteristics of ers agreed to have the training in one continuous session, with

caregivers, including gender, age, race and ethnicity, marital four requesting a Saturday.

status, relationship to patient, and occupation. An informal The duration of the training ranged from three to six hours;

interview was conducted with each caregiver at the end of five of the seven subjects had the training for four hours. One

training for input regarding the usefulness of the training in caregiver decided to have a second day of training: Four hours

preparing him or her for home caregiving. Three main ques- were conducted on day 1 and two hours on day 2. Although

tions were asked: “Do you think that this training has been the patients were not formally invited to participate in the

helpful to you?” “How can we improve the training?” and training, four of seven joined their caregivers during the entire

“Would you recommend this training to all family caregivers training session.

of older patients with cancer?” The amount of time for train- After training was completed, all subjects noted the rel-

ing also was documented. evance of the content as well as the approach to the training.

All believed that the bedside training with an opportunity to

practice skills was effective in increasing their confidence

Results that they would be able to help their loved ones manage their

Sample symptoms. All caregivers unanimously stated that they liked

the individualized approach to the training because it gave

Through convenience sampling, the researchers were able

them a chance to raise personally relevant issues and to focus

to recruit seven caregivers. All seven were female, with a

the training on what they really needed to know. The flexibil-

mean age of 56 (range = 26–76), and more than half were

ity of the scheduling process allowed most of the caregivers to

African American. Most commonly, caregivers were the

participate in the training. All subjects agreed that the experi-

patients’ spouses. Other demographic characteristics of the

ence was worthwhile and highly recommended that the train-

caregivers are shown in Table 2. All subjects resided quite a

ing be given to all cancer caregivers before hospital discharge

distance from the Durham, NC, area, driving 119–282 miles

of their loved ones. When asked how the training could be

roundtrip to participate in the training.

improved, one caregiver stated that patients should be invited

During the three-month enrollment period, the medical di-

to participate, citing that caregiving in home settings is a part-

rector of the ECRC referred 22 patients to the study. Of those,

nership between caregivers and patients. Furthermore, patient

15 (68%) had primary caregivers at home; however, almost

participation in the training simulates the milieu of home-

half of those patients (n = 7) refused to allow their caregivers

based caregiving, making the context of training relevant and

to be contacted for the training. A common reason for refusal

realistic. Other caregivers thought that the training was very

was to avoid placing additional burden on their caregivers.

good and offered no suggestions for improvement.

Most said that their caregivers were busy working and would

not have time to perform the training. The remaining eight

patients provided contact information for their caregivers Discussion

or agreed to have their caregivers contact the PI when they

As the provision of cancer care shifts from acute settings to

visited.

home settings, the impetus shifts to better preparing informal

Seven of the eight caregivers agreed to participate. Three

caregivers. Symptom management consistently has been iden-

of them contacted the PI first to inquire about the study and

tified as an essential component of effective home caregiving

eventually agreed to participate. The PI contacted the remain-

(Steinhauser et al., 2000); however, most caregivers do not

ing five by telephone. One caregiver declined to participate

feel confident and are ill-prepared to help their loved ones

because of a scheduling conflict (specifically, her work sched-

manage their cancer symptoms at home. The period after

ule varied from day to day, so she was unable to commit to a

hospitalization appears to be one of the most critical periods

in symptom management for patients with cancer (Laizner

et al., 1993; Weitzner et al., 1999). Yet healthcare providers

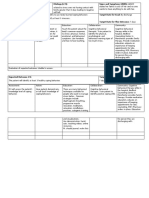

Table 2. Demographic Characteristics of Participating continue to neglect caregivers’ needs for formal education and

Caregivers training prior to hospital discharge.

Flexibility in scheduling training proved to be crucial when

Relationship Marital

soliciting attendance from informal caregivers, because most

Caregiver to Patient Age Race Status Working

of the subjects worked. This reflects the current characteristics

1

a

Sister 57 Caucasian Married No of caregivers in the country: 59% either work or have worked

2

a

Daughter-in-law 26 Caucasian Married No while providing care (National Alliance for Caregiving &

a

3 Mother 72 African Widowed Yes AARP, 2004). Work and perhaps driving distance had the most

American influence on caregivers’ decisions to complete training in one

a

4 Sister 47 African Married Yes session. As anticipated, most training was on a weekend.

American The biggest challenge was in recruiting caregivers through

a

5 Wife 76 Caucasian Married No the patients themselves. The authors were surprised that,

a

6 Wife 68 African Married No

even when older patients viewed the training as potentially

American

7

a

Yes

helpful to their caregivers, almost half were reluctant to have

Wife 48 African Married

American

their caregivers participate. Most said that they worried about

imposing additional burdens on their caregivers. Some cited

that their caregivers had too much to do and would not have

a

This caregiver also was a healthcare professional. time to participate. However, the researchers did not find the

ONCOLOGY NURSING FORUM – VOL 33, NO 4, 2006

796

same reluctance among informal caregivers contacted by tion that older patients with cancer may be too fatigued or

phone. Rather, they all were eager to participate because they distraught to participate in training, however, was refuted. In

viewed the training as potentially helpful in preparing them to contrast, patient participation was seen to simulate the milieu

give the best care to their loved ones at home. of home-based caregiving, making the context of training

Although the institutional review board did not require the relevant and realistic.

researchers to obtain consent from patients, the researchers For symptom management intervention that requires skills,

solicited patients’ permission to have their caregivers in the the researchers purposefully gave caregivers an opportunity

study because of the necessity to discuss their symptoms and to practice the skills under the tutelage of an expert (the PI).

homecare issues with their caregivers. The researchers were The caregivers unanimously complimented the approach as

quite challenged with how to deal with patient-protected in- effective and important in boosting their confidence that they

formation. With the advent of the Health Insurance Portability could actually perform the interventions. This is an important

and Accountability Act of 1996 and its mandate of strict pro- finding of the study, because self-confidence is essential for

tection of privacy, the problem is common among researchers any course of action. Even when individuals believe that

in informal caregiving (Albert & Levine, 2005). particular actions will produce certain results, they will not

act on that belief if they question whether they can take the

Implications for Nursing Practice necessary actions (Bandura, 1997). Most cancer caregiver

education programs mainly consist of written or audiovisual

Caregiving education and support are considered to be un- modules that are insufficient in promoting self-efficacy in

der the purview of the nursing discipline. Nurses always have caregiving.

taken the lead in assisting and educating informal caregivers In summary, one-on-one, experiential training regarding

as they prepare to care for their loved ones at home. The re- cancer symptom management and home care given to infor-

sults of the initial pilot study support an innovative approach mal caregivers at the bedside prior to discharge from acute

to caregiver training. The findings indicate that when given care settings was feasible and received well by caregivers. To

an opportunity for training on cancer symptom management the researchers’ knowledge, no studies have systematically

prior to hospital discharge, informal caregivers were very in- looked at this type of training and its potential effects on care-

terested in participating despite the fact that they had to travel givers. In addition, the authors believe that through the train-

long distances for the training (the nearest caregiver lived ing, nurses have the potential to improve patient outcomes and

almost 60 miles away from the hospital). This underscores ultimately enable older patients with cancer to remain as long

how important the training was to caregivers. The research- as possible in the comfort of their homes.

ers’ assumption that a one-on-one approach to training would

be more advantageous than a group approach was supported The authors acknowledge Jack Twersky, MD, for his contribution to subject

by the caregivers’ feedback. They were unanimous in stating recruitment.

that individualized training gave them an opportunity to have

their particular needs met, unlike in group training, where Author Contact: Cristina C. Hendrix, DNS, APRN-BC, GNP, FNP, can

caregivers often are left to decide on their own how to apply be reached at cristina.hendrix@duke.edu, with copy to editor at ONF

information to their situations. The researchers’ other assump- Editor@ons.org.

References

Albert, S.M., & Levine, C. (2005). Family caregiver research and the HIPAA Flesch, R. (1974). The art of readable writing. New York: Harper and Row.

factor. Gerontologist, 45, 432–437. Giarelli, E., McCorkle, R., & Monturo, C. (2003). Caring for a spouse after

Andrews, S.C. (2001). Caregiver burden and symptom distress in people prostate surgery: The preparedness needs of wives. Journal of Family

with cancer receiving hospice care. Oncology Nursing Forum, 28, Nursing, 9, 453–485.

1469–1474. Hendrix, C.C. (2004). A manual for informal caregivers on cancer symptom

Aranda, S.K., & Hayman-White, K. (2001). Home caregivers of the person management. Unpublished manuscript.

with advanced cancer: An Australian perspective. Cancer Nursing, 24, Hodges, L.J., Humphris, G.M., & Macfarlane, G. (2005). A meta-analytic in-

300–307. vestigation of the relationship between the psychological distress of cancer

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cogni- patients and their carers. Social Science and Medicine, 60(1), 1–12.

tive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Hudson, P., Aranda, S., & McMurray, N. (2002). Intervention development

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W.H. for enhanced lay palliative caregiver support—The use of focus groups.

Freeman and Company. European Journal of Cancer Care, 11, 262–270.

Bandura, A., Adams, N.E., & Beyer, J. (1977). Cognitive processes mediat- Kurtin, D., Elting, L., Martin, C., DeFord, L., Rubenstein, E., Lam, T., et al.

ing behavioral change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, (1999, June). Risk, outcomes and cost of emergency center visits in cancer

35(3), 125–139. patients [Abstract]. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American

Chorley, J.N. (2005). Ankle sprain discharge instructions from the emergency Society of Clinical Oncology, Atlanta, GA.

department. Pediatric Emergency Care, 21, 498–501. Laizner, A.M., Yost, L.M., Barg, F.K., & McCorkle, R. (1993). Needs of

Edwards, B.K., Howe, H.L., Ries, L.A., Thun, M.J., Rosenberg, H.M., Yan- family caregivers of persons with cancer: A review. Seminars in Oncology

cik, R., et al. (2002). Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, Nursing, 9, 114–120.

1973–1999, featuring implications of age and aging on U.S. cancer burden. Lee, T.L., & Bokovoy, J. (2005). Understanding discharge instructions after

Cancer, 94, 2766–2792. vascular surgery: An observational study. Journal of Vascular Nursing,

Ferrari, R., Rowe, B.H., Majumdar, S.R., Cassidy, J.D., Blitz, S., Wright, 23(1), 25–29.

S.C., et al. (2005). Simple educational intervention to improve the recovery Morris, S.M., & Thomas, C. (2001). The carer’s place in the cancer situation:

from acute whiplash: Results of a randomized, controlled trial. Academic Where does the carer stand in the medical setting? European Journal of

Emergency Medicine, 12, 699–706. Cancer Care, 10, 87–95.

ONCOLOGY NURSING FORUM – VOL 33, NO 4, 2006

797

National Alliance for Caregiving & AARP. (2004). Family caregiving in the into practice at home. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management,

US: Findings from a national survey. Washington, DC: Authors. 23, 369–382.

Pasacreta, J.V., & McCorkle, R. (2000). Cancer care: Impact of interven- Steele, R.G., & Fitch, M.I. (1996). Needs of family caregivers of patients

tions on caregiver outcomes. Annual Review of Nursing Research, 18, receiving home hospice care for cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 23,

127–148. 823–828.

Reynolds, M.A.H. (2002, Spring). Post-surgical pain management discharge Steinhauser, K.E., Clipp, E.C., McNeilly, M., Christakis, N.A., McIntyre,

teaching—A pilot study [Abstract]. Communicating Nursing Research, L.M., & Tulsky, J.A. (2000). In search of a good death: Observations

35, 360. of patients, families, and providers. Annals of Internal Medicine, 132,

Rose, K.E. (1999). A qualitative analysis of the information needs of informal 825–832.

caregivers of terminally ill cancer patients. Journal of Clinical Nursing, Sutton, L.M., Clipp, E.C., & Winer, E.P. (2000). Management of the termi-

8, 81–88. nally ill patient. In C.P. Hunter, K.A. Johnson, & H.B. Muss (Eds.), Cancer

Schulz, R., & Beach, S.R. (1999). Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: in the elderly (pp. 543–572). New York: Marcel Dekker.

The Caregiver Health Effects Study. JAMA, 282, 2215–2219. Sutton, L.M., Demark-Wahnefried, W., & Clipp, E.C. (2003). Management of

Schulz, R., Visintainer, P., & Williamson, G.M. (1990). Psychiatric and physi- terminal cancer in elderly patients. Lancet Oncology, 4, 149–157.

cal morbidity effects of caregiving. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Weitzner, M.A., Jacobsen, P.B., Wagner, H., Friedland, J., & Cox, C. (1999).

Sciences, 45(5), P181–P194. The Caregiver Quality of Life Index–Cancer (CQOLC) scale: Develop-

Schumacher, K.L., Koresawa, S., West, C., Hawkins, C., Johnson, C., ment and validation of an instrument to measure quality of life of the fam-

Wais, E., et al. (2002). Putting cancer pain management regimens ily caregiver of patients with cancer. Quality of Life Research, 8, 55–63.

ONCOLOGY NURSING FORUM – VOL 33, NO 4, 2006

798

You might also like

- Eccles & Wigfield - From Expectancy-Value Theory To Situated Expectancy-Value TheoryDocument13 pagesEccles & Wigfield - From Expectancy-Value Theory To Situated Expectancy-Value TheoryRubén Páez DíazNo ratings yet

- NURSING CARE PLAN - Breast CancerDocument2 pagesNURSING CARE PLAN - Breast Cancerderic100% (3)

- Plan of Activities For Surgery WardDocument4 pagesPlan of Activities For Surgery WardFrances DaeNo ratings yet

- The Antidote to Suffering: How Compassionate Connected Care Can Improve Safety, Quality, and ExperienceFrom EverandThe Antidote to Suffering: How Compassionate Connected Care Can Improve Safety, Quality, and ExperienceNo ratings yet

- Doing Good by Knowing Who You Are: The Instrumental Self As An Agent of ChangeDocument5 pagesDoing Good by Knowing Who You Are: The Instrumental Self As An Agent of ChangeNitin NigamNo ratings yet

- Pilot Study of a Communication Coaching Telephone Intervention for Lung Cancer CaregiversDocument7 pagesPilot Study of a Communication Coaching Telephone Intervention for Lung Cancer CaregiversCamilaAlejandraHuenchulaoDiazNo ratings yet

- Barriers To and Enablers For Prehospital Analgesia For Pediatric PatientsDocument8 pagesBarriers To and Enablers For Prehospital Analgesia For Pediatric PatientsfuckyeahonewNo ratings yet

- Nursing DX Ineffective CopingDocument2 pagesNursing DX Ineffective CopingBillNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care PlanDocument3 pagesNursing Care PlanMeryl MarcosNo ratings yet

- New Nurses Perceptions of Nursing Practice And.14Document6 pagesNew Nurses Perceptions of Nursing Practice And.14MaryNo ratings yet

- Oncology Nurse Communication Barriers To Patient-Centered CareDocument7 pagesOncology Nurse Communication Barriers To Patient-Centered CareSally YamanNo ratings yet

- Recommendation of Pre-Operative Screening Intervention Evaluation Nursing Intervention Manpower Resources RequiredDocument7 pagesRecommendation of Pre-Operative Screening Intervention Evaluation Nursing Intervention Manpower Resources RequiredBernice EbbiNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0010782418303950 MainDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S0010782418303950 MainCliff Daniel DIANZOLE MOUNKANANo ratings yet

- Ethical Decision Making.1Document2 pagesEthical Decision Making.1NoorNo ratings yet

- W62011151P381700 FirstDocument1 pageW62011151P381700 FirstmochkurniawanNo ratings yet

- Crit Care Nurse 2008 Schmalenberg 54 65Document12 pagesCrit Care Nurse 2008 Schmalenberg 54 65snakovaNo ratings yet

- Absence of Responsible Member and Financial ConstraintsDocument2 pagesAbsence of Responsible Member and Financial ConstraintsFavor ColaNo ratings yet

- Putting Evidence Into Practice: Evidence-Based Interventions For DepressionDocument12 pagesPutting Evidence Into Practice: Evidence-Based Interventions For Depressiondedi kurniawanNo ratings yet

- NCP OsteoDocument3 pagesNCP OsteoLaw MaeNo ratings yet

- Feasibility and Rationale For Incorporating.33Document9 pagesFeasibility and Rationale For Incorporating.33roberta schiavoneNo ratings yet

- Current Issues in NursingDocument6 pagesCurrent Issues in Nursingyogithajeganathan5197No ratings yet

- PQCNC New Initiative Proposal NASDocument9 pagesPQCNC New Initiative Proposal NASkcochranNo ratings yet

- DR KanchnDocument1 pageDR KanchnprashantmNo ratings yet

- Virtual Poster-Msn CHF StrainDocument1 pageVirtual Poster-Msn CHF Strainapi-577634653No ratings yet

- Journal of Transcultural NursingDocument7 pagesJournal of Transcultural NursingBiancaNo ratings yet

- Enhancingcommunication: Lesson1:Communicatingwithpatients LearningobjectivesDocument10 pagesEnhancingcommunication: Lesson1:Communicatingwithpatients LearningobjectivesKibegwa MoriaNo ratings yet

- Caring in The Margins A Scholarship Of.5 PDFDocument13 pagesCaring in The Margins A Scholarship Of.5 PDFRirin prastia agustinNo ratings yet

- Coek - Info Dentofacial Orthopedics With Functional AppliancesDocument2 pagesCoek - Info Dentofacial Orthopedics With Functional ApplianceshabeebNo ratings yet

- StandPoint Best Practices in Patient EdDocument20 pagesStandPoint Best Practices in Patient Edkcreel44No ratings yet

- Keaslian Penelitian Tabel 2.3 Keaslian PenelitianDocument3 pagesKeaslian Penelitian Tabel 2.3 Keaslian PenelitianfetreonegeoNo ratings yet

- PosterDocument1 pagePosterLana kamalNo ratings yet

- Breaking Bad News: An Evidence-Based Review of Communication Models For Oncology NursesDocument8 pagesBreaking Bad News: An Evidence-Based Review of Communication Models For Oncology NursesDaniela Lepărdă100% (1)

- Best Practices For Transitioning Patients, 65 Years and Older, From The Hospital To Their Next Level of Care That Prevent Avoidable ReadmissionsDocument6 pagesBest Practices For Transitioning Patients, 65 Years and Older, From The Hospital To Their Next Level of Care That Prevent Avoidable ReadmissionsAnnold ochiezyNo ratings yet

- Breaking Bad For Oncology NursesDocument8 pagesBreaking Bad For Oncology Nursessaifadin khalilNo ratings yet

- Old Signages Around The Institution Assessment/ Observation Management Diagnosis Plans Justification Intervention Resources Evaluation Manpower MaterialsDocument4 pagesOld Signages Around The Institution Assessment/ Observation Management Diagnosis Plans Justification Intervention Resources Evaluation Manpower MaterialsChloe MorningstarNo ratings yet

- Using Relaxation and Guided Imagery to Address Pain, Fatigue, and Sleep Disturbances: A Pilot StudyDocument6 pagesUsing Relaxation and Guided Imagery to Address Pain, Fatigue, and Sleep Disturbances: A Pilot StudyKarlosFD videosvariosNo ratings yet

- Why Not Cancer?Document1 pageWhy Not Cancer?Perdana DialisisNo ratings yet

- Using An Interactive Video Simulator To Improve Certified Nursing Assistants ' Dressing Assistance and Nursing Home Residents ' Dressing PerformanceDocument10 pagesUsing An Interactive Video Simulator To Improve Certified Nursing Assistants ' Dressing Assistance and Nursing Home Residents ' Dressing Performanceapi-523802785No ratings yet

- CHN NCPDocument3 pagesCHN NCPDEE-EMNo ratings yet

- Smile Train INDIADocument21 pagesSmile Train INDIAraghava_cseNo ratings yet

- Specialist Palliative Care Services For Older People in Primary Care: A Systematic Review Using Narrative SynthesisDocument17 pagesSpecialist Palliative Care Services For Older People in Primary Care: A Systematic Review Using Narrative SynthesisKavinkumar SaravananNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plan Endometrial CancerDocument2 pagesNursing Care Plan Endometrial Cancerderic88% (16)

- Qi Presentation Heparin AdministrationDocument10 pagesQi Presentation Heparin Administrationapi-383995637No ratings yet

- Knowledge and BeliefsDocument8 pagesKnowledge and Beliefshayatzu1No ratings yet

- Professional Development Grid EhhDocument3 pagesProfessional Development Grid Ehhapi-354642078No ratings yet

- Daas 1Document6 pagesDaas 1asialoren74No ratings yet

- JLH and Rambo Final PosterDocument1 pageJLH and Rambo Final Posterapi-271971026No ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plan For Breast Cancer NCPDocument2 pagesNursing Care Plan For Breast Cancer NCPEsha MeharNo ratings yet

- UC Irvine Previously Published WorksDocument14 pagesUC Irvine Previously Published WorksNurul RiskiNo ratings yet

- NCP Medial CanthopexyDocument6 pagesNCP Medial CanthopexyIRA MONIQUE CABADENNo ratings yet

- Yopp 2013Document5 pagesYopp 2013Gabriella DivaNo ratings yet

- NEJM Physician ShopDocument2 pagesNEJM Physician ShopZsolt OrbanNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plan For Breast Cancer NCP PDFDocument2 pagesNursing Care Plan For Breast Cancer NCP PDFMaina Barman100% (1)

- Nursing Care Plan For Breast Cancer NCPDocument2 pagesNursing Care Plan For Breast Cancer NCPMaina BarmanNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plan For Breast Cancer NCP PDFDocument2 pagesNursing Care Plan For Breast Cancer NCP PDFMaina BarmanNo ratings yet

- CARES BrochureDocument2 pagesCARES BrochureDaniel FernándezNo ratings yet

- MC Kinney December 2021 CJONDocument8 pagesMC Kinney December 2021 CJONAlessandra BendoNo ratings yet

- Delfinm QsenDocument57 pagesDelfinm Qsenapi-346220114No ratings yet

- Exploring the Gray Zone: Case Discussions of Ethical Dilemmas for the Veterinary TechnicianFrom EverandExploring the Gray Zone: Case Discussions of Ethical Dilemmas for the Veterinary TechnicianAndrea DeSantis KerrNo ratings yet

- Restraints in Dementia Care: A Nurse’s Guide to Minimizing Their UseFrom EverandRestraints in Dementia Care: A Nurse’s Guide to Minimizing Their UseNo ratings yet

- Advanced Practice and Leadership in Radiology NursingFrom EverandAdvanced Practice and Leadership in Radiology NursingKathleen A. GrossNo ratings yet

- Comprehensive Healthcare Simulation: Mobile Medical SimulationFrom EverandComprehensive Healthcare Simulation: Mobile Medical SimulationPatricia K. CarstensNo ratings yet

- Axelsson 2012Document11 pagesAxelsson 2012happyNo ratings yet

- RETREAT Framework Et Al. 2018Document12 pagesRETREAT Framework Et Al. 2018happyNo ratings yet

- Hendrix 2011Document21 pagesHendrix 2011happyNo ratings yet

- Hudson 2005Document13 pagesHudson 2005happyNo ratings yet

- He Demand 2011Document9 pagesHe Demand 2011happyNo ratings yet

- Davison Et Al 2006Document5 pagesDavison Et Al 2006happyNo ratings yet

- ChecklistDocument2 pagesChecklisthappyNo ratings yet

- Leadership Joyce 2016Document7 pagesLeadership Joyce 2016happyNo ratings yet

- Study of Teaching Competence in Relation To Self - Efficacy Among Secondary School TeachersDocument13 pagesStudy of Teaching Competence in Relation To Self - Efficacy Among Secondary School TeachersAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- Module 3Document4 pagesModule 3Color RedNo ratings yet

- 2021 1926896Document18 pages2021 1926896sofia domingosNo ratings yet

- Learning Theories in Entrepreneurship: New Perspectives: January 2012Document37 pagesLearning Theories in Entrepreneurship: New Perspectives: January 2012leila KhalladNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Educational Psychology: Dale H. Schunk, Maria K. Dibenedetto TDocument10 pagesContemporary Educational Psychology: Dale H. Schunk, Maria K. Dibenedetto TNurul FitriNo ratings yet

- HBO Module Midterm and FinalsDocument24 pagesHBO Module Midterm and FinalsMariane Joyce R. BolesaNo ratings yet

- Kiya FelekeDocument50 pagesKiya Felekekiya felelkeNo ratings yet

- Overview of Social Cognitive Theory and of Self EfficacyDocument5 pagesOverview of Social Cognitive Theory and of Self Efficacydata kuNo ratings yet

- Effect of Gender in SLA Inspiring Gender Roles SLADocument5 pagesEffect of Gender in SLA Inspiring Gender Roles SLAMircavid HeydəroğluNo ratings yet

- Self Confidence Foreign StudiesDocument5 pagesSelf Confidence Foreign Studiesjosekin80% (5)

- References For Students With Special NeedsDocument99 pagesReferences For Students With Special NeedsJunalyn Ëmbodo D.No ratings yet

- Students' Level of Self-Confidence and Performance Tasks: ArticleDocument8 pagesStudents' Level of Self-Confidence and Performance Tasks: ArticleJOHN JOMIL RAGASANo ratings yet

- Predicting Health Behaviour PDFDocument402 pagesPredicting Health Behaviour PDFMARILIA LUCIA BAQUERIZO SEDANONo ratings yet

- Practice of Managerial Coaching and Employees Performance BehaviorDocument11 pagesPractice of Managerial Coaching and Employees Performance BehaviorEsha ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- 1 - A Study To Assess The Effectiveness of Mindful Meditation On Adjustment Problem Faced by First Year BDocument5 pages1 - A Study To Assess The Effectiveness of Mindful Meditation On Adjustment Problem Faced by First Year BJohn Ace Revelo-JubayNo ratings yet

- Motivating StudentsDocument85 pagesMotivating StudentsSurya Ningsih100% (1)

- Work Motivation Affecting Self EfficacyDocument4 pagesWork Motivation Affecting Self EfficacyAlina GheNo ratings yet

- Peer Pressure and Its Impact To Personality Development (Chapter 1-5)Document51 pagesPeer Pressure and Its Impact To Personality Development (Chapter 1-5)Jaze RamosNo ratings yet

- Self Efficacy (What It Is and Why It Matters)Document3 pagesSelf Efficacy (What It Is and Why It Matters)ABDUL RAUF100% (1)

- Gender, Internet ActivityDocument16 pagesGender, Internet Activity邓明铭No ratings yet

- Local RRSDocument3 pagesLocal RRSangelo canonNo ratings yet

- Uts Final ReviewerDocument14 pagesUts Final ReviewerCarla QuiñonesNo ratings yet

- Research Chapter2 PDFDocument3 pagesResearch Chapter2 PDFJayvan ChavarriaNo ratings yet

- TACONET Proceedings+CDocument158 pagesTACONET Proceedings+CGaetano Bruno RonsivalleNo ratings yet

- G11 Campos Research Proposal Group 1Document48 pagesG11 Campos Research Proposal Group 1remar rubindiazNo ratings yet

- Leadership and Student Development TheoryDocument16 pagesLeadership and Student Development TheoryEric RuelleNo ratings yet

- Theory MotivationDocument27 pagesTheory MotivationginabonieveNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Speaking and Listening (RRL - 1)Document11 pagesRelationship Between Speaking and Listening (RRL - 1)Gen PriestleyNo ratings yet