Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Summary Research Methods For Business Students H 1 13

Summary Research Methods For Business Students H 1 13

Uploaded by

Vikram VickyCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

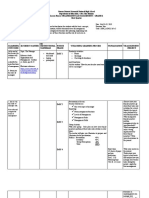

- IEC 60601 1 2 4th Edition PDFDocument21 pagesIEC 60601 1 2 4th Edition PDFjose david bermudez perez0% (1)

- Measure It Up!: Performance Task Grade 7 - Mathematics Quarter 2Document1 pageMeasure It Up!: Performance Task Grade 7 - Mathematics Quarter 2ROSELYN SANTIAGO100% (5)

- Productivity Tool EssayDocument1 pageProductivity Tool EssayJohnelyn Porlucas MacaraegNo ratings yet

- Resultados de La Web: ZimmermanDocument3 pagesResultados de La Web: ZimmermanTryj1No ratings yet

- Chapter 2 - Generating The Research TopicDocument3 pagesChapter 2 - Generating The Research TopicAbdul BasitNo ratings yet

- Queens College Business Research Methods-1Document232 pagesQueens College Business Research Methods-1shigaze habteNo ratings yet

- BRM Study PackDocument146 pagesBRM Study PackFaizan ChNo ratings yet

- BRM CivilDocument159 pagesBRM CivilRahul SahuNo ratings yet

- Business Research Methods Unit IDocument34 pagesBusiness Research Methods Unit IRohitNo ratings yet

- The Nature of Business ResearchDocument21 pagesThe Nature of Business ResearchAbdiweli mohamedNo ratings yet

- Notes Business Research MethodsDocument101 pagesNotes Business Research MethodsMuneebAhmedNo ratings yet

- Research Methodology Unit 2Document33 pagesResearch Methodology Unit 2Raghavendra A NNo ratings yet

- BRM NotesDocument74 pagesBRM NotesShilpi SinghNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1 Research Methodology: Mr. Kwadwo Boateng PrempehDocument25 pagesLesson 1 Research Methodology: Mr. Kwadwo Boateng PrempehprempehNo ratings yet

- Module Overview-Research MethodsDocument33 pagesModule Overview-Research Methodselijah phiriNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Summary 17253Document6 pagesChapter 2 Summary 17253Lasitha NawarathnaNo ratings yet

- Business Research MethodDocument26 pagesBusiness Research Methodjitender KUMARNo ratings yet

- Research of GonderDocument68 pagesResearch of GonderTesfu HettoNo ratings yet

- RRRRDocument72 pagesRRRRVenkateswara Raju100% (1)

- Criteria For Good Research 1Document5 pagesCriteria For Good Research 1Mohammed OmerNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2 The Research ProcessDocument2 pagesLesson 2 The Research ProcessMarkChristianRobleAlmazanNo ratings yet

- Week 002 Module The Research ProcessDocument2 pagesWeek 002 Module The Research ProcessJohnloyd LapiadNo ratings yet

- Module-I Business Research BasicsDocument22 pagesModule-I Business Research BasicsNivedita SinghNo ratings yet

- Research Methods For Business Students - Chapter 1Document6 pagesResearch Methods For Business Students - Chapter 1Lasitha NawarathnaNo ratings yet

- Samenvatting Business Research MethodsDocument15 pagesSamenvatting Business Research MethodsER AsesNo ratings yet

- Course 1 - Introduction of Research MethodDocument32 pagesCourse 1 - Introduction of Research Methodteuku ismaldyNo ratings yet

- Chapter Objectives: Scope of Business Research Business Research DefinedDocument49 pagesChapter Objectives: Scope of Business Research Business Research DefinedZena Addis Shiferaw100% (1)

- Rift Valley University: Course Title: Business Research MethodsDocument4 pagesRift Valley University: Course Title: Business Research MethodsAbdela Aman MtechNo ratings yet

- Methodology Used in Research PapersDocument5 pagesMethodology Used in Research Papersc9spy2qz100% (1)

- Research Methodology Assignment: Farhad Bharucha Roll No: 18 MMM Semester-1Document18 pagesResearch Methodology Assignment: Farhad Bharucha Roll No: 18 MMM Semester-1farhad10_1No ratings yet

- Methodology 1 ChinaDocument13 pagesMethodology 1 ChinaErk ContreNo ratings yet

- Research Methods in ThesisDocument4 pagesResearch Methods in Thesisjennifercruzwashington100% (2)

- Subject Code & Name - Bba 201research Methods: BK Id-B1518 Credits 2 Marks 30Document7 pagesSubject Code & Name - Bba 201research Methods: BK Id-B1518 Credits 2 Marks 30mreenal kalitaNo ratings yet

- Introducing ResearchDocument13 pagesIntroducing Researchdeo cabradillaNo ratings yet

- Farha BRM Notes MbaDocument16 pagesFarha BRM Notes MbaFarhaNo ratings yet

- Suggest Directions For Future ResearchDocument17 pagesSuggest Directions For Future Researchmuhammad qasimNo ratings yet

- Research Method Chapter OneDocument21 pagesResearch Method Chapter OneAlmaz Getachew100% (1)

- Unit 2Document77 pagesUnit 2komalkataria2003No ratings yet

- 2021 - PDF - Research Methods For ManagersDocument30 pages2021 - PDF - Research Methods For ManagersTIHONOVA (c. BOTAN) VALENTINANo ratings yet

- Pracrea1 Chapter 1Document36 pagesPracrea1 Chapter 1Abegail AcohonNo ratings yet

- RM Module 1-6 MaterialsDocument122 pagesRM Module 1-6 Materialsabhi60rNo ratings yet

- BRM - Final Review QuestionDocument15 pagesBRM - Final Review Questionarteam.lmuyenNo ratings yet

- Week 1 - Topic OverviewDocument13 pagesWeek 1 - Topic Overviewashley brookeNo ratings yet

- Principles of Research Design: March 2021Document22 pagesPrinciples of Research Design: March 2021Sharad RathoreNo ratings yet

- Dr. Manas Kumar PalDocument23 pagesDr. Manas Kumar PalManas PalNo ratings yet

- Leacture NoteDocument82 pagesLeacture NoteYN JohnNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1 Research Skills PDFDocument5 pagesAssignment 1 Research Skills PDFVardaSamiNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1 Introduction Modified RMDocument33 pagesLecture 1 Introduction Modified RMMuhammad JunaidNo ratings yet

- Research Methodology Unit 1 Ph.D. Course WorkDocument15 pagesResearch Methodology Unit 1 Ph.D. Course WorkMOHAMMAD WASEEMNo ratings yet

- Business Research MethodsDocument99 pagesBusiness Research Methodsjagadish hudagiNo ratings yet

- Assignment Fundamentals of Research Methodology: Dr. Khalid Mahmod BhattiDocument12 pagesAssignment Fundamentals of Research Methodology: Dr. Khalid Mahmod BhattiZohaib TariqNo ratings yet

- Research Process BBM 502: Aditi Gandhi BBM VTH Sem. 107502Document13 pagesResearch Process BBM 502: Aditi Gandhi BBM VTH Sem. 107502geetukumari100% (1)

- Research Methodology and Graduation ProjectDocument47 pagesResearch Methodology and Graduation Projectجیهاد عبدالكريم فارسNo ratings yet

- Steps of Research ProcessDocument6 pagesSteps of Research ProcessJasreaNo ratings yet

- Research Methodology Step by Step Guide For StuedentsDocument14 pagesResearch Methodology Step by Step Guide For StuedentshaiodNo ratings yet

- 18MBA23 Research Methods Full Notes With Question BankDocument87 pages18MBA23 Research Methods Full Notes With Question BankNeena86% (7)

- Definition of A Research Project ProposalDocument11 pagesDefinition of A Research Project ProposalAbu BasharNo ratings yet

- Research MethodologyDocument24 pagesResearch Methodologylatha gowdaNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Methodology Focus GroupDocument7 pagesDissertation Methodology Focus GroupWriteMyThesisPaperCanada100% (1)

- BRM Unit-1Document20 pagesBRM Unit-1REDAPPLE MEDIANo ratings yet

- Introduction To Researcch Methods (AutoRecovered)Document61 pagesIntroduction To Researcch Methods (AutoRecovered)mikee franciscoNo ratings yet

- Mr./Ms. Vikram Aditya Raja Mallula: This Certificate Is Presented ToDocument2 pagesMr./Ms. Vikram Aditya Raja Mallula: This Certificate Is Presented ToVikram VickyNo ratings yet

- SSS CCL Aka PDFDocument18 pagesSSS CCL Aka PDFVikram VickyNo ratings yet

- Inventory Management: Raw Material Policies Are Decided by Purchasing and Production DepartmentsDocument8 pagesInventory Management: Raw Material Policies Are Decided by Purchasing and Production DepartmentsVikram VickyNo ratings yet

- Receivables Management: Costs Associated With Maintaining ReceivablesDocument6 pagesReceivables Management: Costs Associated With Maintaining ReceivablesVikram VickyNo ratings yet

- Accounting Part1Document305 pagesAccounting Part1Vikram VickyNo ratings yet

- CRPC 154Document5 pagesCRPC 154vipin jaiswalNo ratings yet

- ED 241 - Contemporary National DevelopmentDocument9 pagesED 241 - Contemporary National DevelopmentAlmera Mejorada - Paman100% (1)

- Crump Multiparty Negotiation PDFDocument39 pagesCrump Multiparty Negotiation PDFIvan PetrovNo ratings yet

- Monetary System 1Document6 pagesMonetary System 1priyankabgNo ratings yet

- ENG40001 Final Year Research Project 1 Semester 2, 2020: RubricsDocument8 pagesENG40001 Final Year Research Project 1 Semester 2, 2020: RubricsAS V KameshNo ratings yet

- Other Suggested Resources: Cambridge IGCSE History (9-1) (0977)Document6 pagesOther Suggested Resources: Cambridge IGCSE History (9-1) (0977)Mc MurdoNo ratings yet

- Smart CitiesDocument35 pagesSmart CitiesBhava SharmaNo ratings yet

- Notification NLC ApprenticeDocument3 pagesNotification NLC ApprenticePrasad MallipudiNo ratings yet

- On-Line Application For PLMAT of Pamantasan NG Lungsod NG MaynilaDocument3 pagesOn-Line Application For PLMAT of Pamantasan NG Lungsod NG MaynilaAngela Regala100% (1)

- Thesis Statement - Cleveland State UniversityDocument4 pagesThesis Statement - Cleveland State Universitymaria evangelistaNo ratings yet

- CESC Task-sheet-Week-7-and-8-Qtr.2Document2 pagesCESC Task-sheet-Week-7-and-8-Qtr.2Editha BalolongNo ratings yet

- VPAA Letter To StudentsDocument2 pagesVPAA Letter To StudentsJessaNo ratings yet

- Isover Students Contest 2010Document110 pagesIsover Students Contest 2010Gonzalo Luque GarcíaNo ratings yet

- School Rules and Regulation Agreement With The ParentsDocument15 pagesSchool Rules and Regulation Agreement With The ParentsJulie Ann SuarezNo ratings yet

- Presentation On Marketing MixDocument11 pagesPresentation On Marketing MixTriciaGay DaleyNo ratings yet

- 5 Full Tests Cơ B N - Kèm Đáp Án Bám Sát Sách Giáo KhoaDocument21 pages5 Full Tests Cơ B N - Kèm Đáp Án Bám Sát Sách Giáo KhoabohucNo ratings yet

- Resume CuratioDocument5 pagesResume CuratioJansen Taruc NacarNo ratings yet

- BRM - Post Mid ProjectDocument18 pagesBRM - Post Mid ProjectJeny ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- JCI BackgroundDocument4 pagesJCI BackgroundchensuziNo ratings yet

- Strategic Management Prelims PaperDocument2 pagesStrategic Management Prelims PaperDaniel Mathew VibyNo ratings yet

- Outline in Ethics (By: Group 4)Document6 pagesOutline in Ethics (By: Group 4)Dale Francis Dechavez RutagenesNo ratings yet

- Literature Review JDocument9 pagesLiterature Review JmovinNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Meco6303.pi1.11u Taught by Peter Lewin (Plewin)Document6 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Meco6303.pi1.11u Taught by Peter Lewin (Plewin)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- 1000 Most Common Words in EnglishDocument29 pages1000 Most Common Words in EnglishSebastian ChavezNo ratings yet

- T/royanup/the Evolution of Management TheoryDocument6 pagesT/royanup/the Evolution of Management TheoryAnn TiongsonNo ratings yet

- Philippine Criminal Justice System: Asmundia@sfxc - Edu. PHDocument3 pagesPhilippine Criminal Justice System: Asmundia@sfxc - Edu. PHJayson GeronaNo ratings yet

Summary Research Methods For Business Students H 1 13

Summary Research Methods For Business Students H 1 13

Uploaded by

Vikram VickyOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Summary Research Methods For Business Students H 1 13

Summary Research Methods For Business Students H 1 13

Uploaded by

Vikram VickyCopyright:

Available Formats

lOMoARcPSD|5681783

Summary Research methods for business students, - H 1-13

Methodology of Management Science (Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam)

StuDocu is not sponsored or endorsed by any college or university

Downloaded by Vikram (vikramaditya978@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5681783

1.1 Introduction

This book teaches the different steps one should take when conducting business and management research.

It will help you to undertake a research project by providing a range of approaches, strategies, techniques

and procedures. Throughout this book the term methods and methodology will be used. However some may

think these terms refer to the same thing, they actually have different meanings. The term ‘methods’ refers

to techniques and procedures used to obtain and analyse data, while ‘methodology’ refers to the theory of

how research should be undertaken.

1.2 What is research?

People conduct research to systematically investigate things in order to enhance their knowledge, but

research is not merely collecting data. Research is conducted when:

• Data are collected systematically

• Data are interpreted systematically

• There is a clear goal: to discover new findings

In order to systematically conduct research based on logical relationships, a researcher must provide an

explanation of the methods used to collect data, prove why the results are meaningful and outline any

limitations to the research. The goal of research is not only to explain, describe, criticize, understand or

analyse something, but also to simply find a clear answer to a specific problem.

1.3 The nature of business and management research

Management research is different from other kinds of research because it is transdisciplinary (multiple

studies are involved with it) and it is a design science. Moreover, it has to be theoretically and

methodologically accurate, while at the same time being of practical relevance in the business world. The

researcher Michael Gibbons has introduced 3 modes of knowledge creation:

• Mode 1 – creating fundamental knowledge

• Mode 2 – creating practical relevant knowledge, with emphasis on collaboration

• Mode 3 – creating knowledge that is mainly relevant to the human condition

Research that only emphasises Mode 1 ways of creating knowledge which only focuses on understanding

business and management processes and their outcomes is called basic, fundamental or pure research.

Another type of research is called applied research where the emphasis is more on Mode 2. In this case

research is only being conducted direct relevance to managers and is presented in ways these managers can

understand and act upon. Pure and applied research are two extremes, in order to successfully conduct

business and management research there has to be a balance between the theoretical (Mode 1) and

practical (Mode 2) part of research. The characteristics of pure/basic and applied science are summarised in

figure 1.1 on page 11.

1.4 The research process

When doing research on needs to go through several stages, usually involving: formulating and clarifying

the research topic, reviewing the literature, designing the research, collecting the data, analysing the data

and finally the writing. However, it is not always necessary to pass through these stages one at a time. More

frequently the stages in a research process will cross-refer to other stages, meaning that there is no linear

line in the research process. Therefore it’s important to have a strong research topic and to revise ideas

many times. See figure 1.2 in the book on page 14.

Downloaded by Vikram (vikramaditya978@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5681783

2.2 Characteristics of a good research topic

Before generating ideas for a research topic it is always useful to address the assessment criteria. The topic

of research should be something that really excites the researcher and it should lie within his

capabilities. These capabilities depend on constraints on time and financial resources, possession of the

necessary skills and access to the relevant data. Moreover, it is useful for a researcher to have knowledge of

the literature associated with the topic and to be able to provide bright insights.

It is important to have a symmetry of potential outcomes, which means that the result will have to be of

similar value whatever you find out. If this is not the case there is a chance you find an answer of little

importance. Also consider your career goals, consider how this research could be useful in your future

career.

2.3 Generating and refining research ideas

There are many different techniques that can be used to generate research ideas. They can be divided into

those techniques that involve rational thinking…:

• Examine own strengths and interests, choose a topic in which you are likely to do well

• Explore your university staff research interests

• Analyse past project titles of your university such as dissertations (projects from undergraduates) and

theses (projects made by postgraduates)

• Discuss with colleagues, friends or university tutors

• Search through literature and media (articles in journals, books, reports). Review articles in particular,

since they contain a lot of information about a specific topic and can therefore provide you with many

ideas

…and those that are more based on creative thinking:

• Noting ideas down in a notebook

• Exploring preferences using past projects (see page 28 to know how)

• Brainstorming

• Exploring relevance of an idea to business using the literature, articles may be based on abstract ideas

(conceptual thinking) or on empirical studies (collected and analysed data)

Most often it is a combinations of these two ways of thinking that leads to a good research idea.

Refining Ideas

There exist different techniques for refining research techniques, one of which is the Delphi technique. This

approach requires a group of people who are involved with or share the same interest in the research idea

to generate and pick a more specific research idea. Another way to refine a research idea is to is to turn it

into a research question before turning it into a research project. This is called preliminary inquiry.

Integrating Ideas

The integration of the ideas from the techniques is an important part of a research project. This process

includes ‘working up and narrowing down’, which means that each research idea needs to be classified into

its area, its field, and ultimately the precise aspect into which one is interested.

Downloaded by Vikram (vikramaditya978@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5681783

2.4 The transformation from research idea to research project

Writing research questions

It is very important to define a clear research question at the beginning of the research process. A research

question may be:

• Descriptive – question usually starts with ‘When’, ‘What’, ‘Who’, ‘Where’, or ‘How’

• Evaluative – question may start with ‘How effective…’ or ‘To what extent….’

• Explanatory – question mainly starts with ‘Why’ or has this word in it

Do not make the research question too simple or too difficult to answer. The ‘Goldilocks test’ may be helpful

to determine if a question is too big (when it demands too many resources), too small (provides insufficient

data), too hot (when it is a sensitive subject) or ‘just right’. It is also essential for a research question to

provide new insights.

Writing research objectives

Research questions can be used either to produce more detailed investigative questions or as a starting

point for research objectives. Writing objectives is more generally accepted as a way to specify sense and

direction in a research project than research questions. This is because they are more precise in displaying

what one would like to make clear. Research objections operationalize the research question, which means

that they show the steps that are required to take to answer it.

What is theory and why is it important?

Theory is concerned with causality. This means that it regards the cause and effect relationship between two

or more variables. For example, theory explains why and how a promotion influences employee’s behaviour.

Logical reasoning is essential here to explain in a clear way why this is the case. The role of theory is to

explain the relationship between variables and to make predictions about possible new outcomes. Advising

on how to take research in a certain way (Variable 1) is based on the theory that this will eventually create

effective results (Yield B). By undertaking research it is possible to collect data with which new theories

could be developed.

A research project is designed to either test a theory or to develop a theory. When someone is taking a clear

theoretical standpoint and wishes to test this through the collection of data one is using a deductive

approach. An inductive approach is used when someone builds a theory from the collected and analysed

data. There exist three kinds of theories:

• Grand theories – Newton’s gravity theory, Darwin’s evolution theory etc.

• Middle range theories – these are significant, but they don’t change the way in which we think like

grand theories do

• Substantive theories – focussed on a particular, setting, group, or time theories

2.5 Writing a research outline

The research proposal is a structured outline of a research project. Making a research proposal demands

that you think through what you want to do and why. It helps you to guide the project through all of its

stages. When producing a proposal think of these general criteria:

• A research project needs to be coherent, which means that all the different components of the project

need to be in relationship with each other.

• It needs to be feasible as well. This means that the project should be possible to achieve.

Downloaded by Vikram (vikramaditya978@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5681783

Structure of a research proposal

• Title – This should summarise the research question

• Background – This is an introduction for the reader to the problem or issue, it gives answers to the

questions ‘what is going to be done’ and ‘for what purpose?’. The background also shows the

relationship between a theory and a particular context and it should demonstrate the relationship

between the research and what has been done before in this subject area.

• Research question and objectives - the background should eventually lead to a statement of the

research questions and objectives and the observable outcomes.

• Method – This is the longest section and reveals how the research will be conducted. It consists of two

parts: Research design and data collection. Research design is an overall overview of the chosen

method and provides the reason for choosing this method. Here you will explain the choice for a certain

research strategy and determine an appropriate time frame for the project . The section ‘data collection’

will specific how and where the data will be collected and will explain the various analysis techniques

that will be used during the research.

Downloaded by Vikram (vikramaditya978@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5681783

• Timescale – In this section you will divide the research into different stages and explain how much

time each stage will approximately take.

• Resources – In this facet of the proposal certain resource categories such as finance, data access and

equipment will be taken into consideration. This section will also include the expenses that may be

involved with these categories.

• References – This section consists of the literature sources to which you have referred to.

Downloaded by Vikram (vikramaditya978@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5681783

3.1 What is a literature review?

A literature review is a review in which one makes reasoned judgements about the value of pieces of

literature. When doing this, it is necessary to organise valuable ideas and findings. There are two kinds of

reviews. The first kind of review goes along with the initial search for research ideas, because that’s when

you browse through pieces of work and judge which ones are relevant and which ones are not. The second

kind of reviews are referred to as critical reviews. To be able to show the significance of a research project it

is necessary to understand the subject field and its concepts, ideas and key theories. One is ‘critically

reviewing literature’ when one chooses those pieces of literature that are relevant to the research.

3.2 Critical review

A critical review should be a constructively analysis that critically develops a transparent argument about

what the chosen literature tells you about a research question. It should not simply summarize what a piece

of literature is about. Rather, it is necessary to evaluate what is significant to the research project and what

is not.

The goal of a critical review

Reviewing literature critically enables you to generate the foundation on which a research is based. The

exact goal of reading literature depends on the approach one is wishing to use in a research. A deductive

approach is when you develop a theoretical or conceptual framework which you afterwards test using data.

An inductive approach is when one analyses the collected data to subsequently develop theories from them

and relate them to the literature. The difference with an inductive approach is that you don’t start with

predetermined theories and conceptual frameworks. There are three ways of using literature:

1. Use literature in the initial stages of a research, when making research proposal

2. Use literature to provide the theoretical framework and context

3. To help place research findings within the wider body of knowledge

When a critical review is successful it will provide new insights about a subject area that no one has ever

thought about. It is necessary to show how the new findings and developed theories relate to other

literature about your subject to demonstrate that you are familiar with what has already been said about the

subject.

Adopting a critical view of your reading

In order to read effectively it is necessary to master various skills, which include:

Previewing: Browsing the text to find out what its purpose

Annotating: Conducting an analogue with yourself, the author and the issues at

stake

Summarising: Be able to explain/state the text in your own words

Comparing and contrasting: How has your thinking been altered by this reading?

Use review questions: Questions which you ask yourself during reading which are linked

to your research questions.

Content of a critical review

The critical review will eventually have to appear in a project report. It has to include an evaluation of the

research that has already been done in the subject area, demonstrate and discuss the relationships between

published research findings and refer to the literature in which they were reported. Moreover, a critical

review must present the key points and trends in a structured way and show the relationship with the

research. By doing so the readers of a research project will have background knowledge to the research

questions. When considering the content of a critical review one needs to:

Downloaded by Vikram (vikramaditya978@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5681783

• Include the key academic theories within the chosen research area

• Demonstrate that your knowledge of the chosen area is up to date

• Through clear referencing, enable those reading your project report to find the original publications

which you cite

How to be ‘critical’

Being critical means that one needs to make reasoned judgments about a particular text, by evaluating a

problem with good use of language. This means that one ’s own critical stance needs to be based on clear

arguments and references to the literature. Being critical also means making a clear and justified analysis of

the key literature of a research project.

The structure of the critical literature review

A literature review is a critical analysis and a description of what other writers have written. It is helpful to

address to a literature review as a discussion of how far existing literature goes in answering the chosen

research questions. One should therefore point out the limitations of the existing literature. It is also helpful

to look at the way the review relates to the chosen research objectives. There are three common critical

review structures:

• One single chapter

• A series of chapters

• Throughout the project report while tackling various issues

Every project report should refer to the key issues from the literature in the discussion and conclusions.

Don’t let the review become an uncritical listing of previous research! It is easy to be critical when

constantly tries to compare or contrast different authors and their ideas. The review should be a funnel in

which you:

1. Start at a general level and narrow it down to research questions and objectives

2. Provide a brief overview of key ideas and themes

3. Summarise, compare and contrast research of the key writers

4. Narrow down to highlight research most relevant to the research

5. Provide detailed findings and show how they are related to the literature

6. Highlight those aspects where your research is providing new insights

7. Lead the reader to subsequent sections of your project

3.3 Available literature sources

The available literature sources can be divided into three categories: primary, secondary and tertiary

sources (See Figure 3.3 on page 82).

Downloaded by Vikram (vikramaditya978@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5681783

Primary literature First occurrence of a piece of work. Includes public sources as reports and documents, but

also unpublished work such as letters and memo’s.

Most of the times this kind of literature is very detailed, but not easy to access, therefore it is sometimes

referred to as grey literature.

Secondary literature Is aimed at a wider audience, easier to locate and better covered by tertiary literature.

This includes books, journals and newspapers.

Tertiary literature Also called search tools, to locate primary and secondary literature. They include online

search tools, databases, and dictionaries.

Especially journals are a essential literature source for virtually any research, since they provide a

researcher with information which focussed on his subject area. Nowadays it is easy to access journals via

online databases. Refereed academic journals only publish articles which are evaluated by academics before

their publication. These articles are therefore characterised by their quality and suitability. Professional

journals are made for their members by various organisations. Their articles are usually more of practical

nature than those of refereed academic journals.

3.4 Planning a literature search strategy

If one starts his search for literature it is important to have clearly defined research questions, objectives

and outline proposal. This prevents information overload. One should make a search strategy which

includes:

• The parameters of the search

• The key words and search terms

• The databases and search engines you’re going to use

• The criteria to select relevant and useful studies

Defining parameters

One way to start searching for parameters is to browse lecture notes and course textbooks and make notes

for research question.

Generating search terms

It is important to read articles from key authors as well as recent review articles in the area of research.

This will help generating key words. Recent review articles are sometimes also helpful to refine search

terms, plus they will sometime refer to other work which may be relevant to your project. The identification

of search terms is an essential part of planning a search for relevant literature. The definition of search

terms is: basic terms that describe research questions and objectives and shall be used to search the

tertiary literature. Different techniques for generating search terms are:

1. Discussion

2. Initial reading, dictionaries, encyclopaedias, handbooks and thesauruses

3. Search on Google with ‘define: (enter term)’

4. Brainstorming

5. Relevance trees: constructed after brainstorming - see box 3.11 on page 96

Downloaded by Vikram (vikramaditya978@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5681783

3.5 Conducting literature search

While most it is very tempting to start a literature search with using a search engine such as Google, this

must be handled with care, as the research project should be an academic piece of work and hence must

utilise academic sources. Search should therefore be used to provide access to academic literature.

Conducting literature search can be done by:

1. Using Tertiary literature sources

2. Obtaining literature referenced in books and journal articles you already read

3. Using Internet: see Table 3.4 and figure 3.3

4. Scanning and browsing secondary literature in the library

5. Searching the Internet

3.6 Obtaining and evaluating the literature

Box 3.15 on page 108 displays a checklist of what should be done to evaluate the literature.

3.7 Recording literature

It is important to make notes of the literature one has read, because it will help thinking though the ideas in

the literature in relation to the research. When making notes there are three sets of information one needs

to record:

• Bibliographic details

• Brief summary of content

• Supplementary information

Downloaded by Vikram (vikramaditya978@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5681783

4.1 Why is philosophy important

The way one chooses to collect data belongs in the centre of the research ‘onion’, as displayed below. The

research onion depicts the aspects underlying the choice of data collection techniques.

4.2 Why research philosophy is important

Research philosophy is a term that describes the development of knowledge and the nature of that

knowledge. Understanding research philosophy is important because the very purpose of research is also to

develop new knowledge. It is not true that one philosophy is better than another, but they might be suited

to achieve different things. Two major ways of thinking in philosophy are: ontology and epistemology (See

table 4.1 on page 129).

A pragmatist is someone who thinks that concepts are only relevant where they support action. He believes

that one philosophical position could be more likely lead to the answer to his research question than

another. In addition, a pragmatist also believes that it is possible to work with multiple philosophical

positions. According to a pragmatist there is not one way of thinking.

Ontology

Ontology is a philosophical position that refers to the nature of reality. One aspect of ontology is

objectivism. This means that things exist with a purpose independent of those social actors concerned with

their existence.

Another aspect is subjectivism, which holds that social occurrences are created through the perceptions and

consequent actions of the involved social actors. People who adopt a subjectivist way of thinking find it is

necessary to explore the details of a situation to be able to understand what is going on. This is termed

social constructionism.

Objectivists think that the culture of an organisation is something that an organisation ‘has’ while

subjectivist tend to view the culture as something an organisation ‘is’. Management theory is leaning

towards the objectivist way of thinking.

Downloaded by Vikram (vikramaditya978@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5681783

Epistemology

Epistemology regards what constitutes acceptable knowledge in an area of study. It addresses the

questions: ‘What is knowledge?’, ‘How is knowledge acquired?’ and ‘What do people know?’.

Positivism

The philosophy of positivism refers to the philosophical stance of a natural scientist. This philosophy holds

that collecting data about an observable reality and searching for regularities and causal relationships will

lead to the creation of a new theory or new generalisations. Other characterizations of positivism are:

• The researcher is independent of the subject of the research, he is value-neutral (his feelings are

included in the research)

• Cyclical relationship between hypothesis testing and theoretical development

• Quantifiable observations that lend themselves to statistical analysis

Realism

Realism claims that whatever we sense is reality: objects exist without concern of the human mind.

Therefore realism contradicts idealism, which states that only the mind and its contents exist. Just like

positivism, realism also assumes a scientific approach to the development of knowledge. There exist two

kinds of realism:

• Direct realism – what you see is what you get, what we perceive and experience with our senses

displays the world in an accurate way.

• Critical realism – what we experience are sensations, images of existing things in the real world, not the

existing things themselves. What we experience are mere illusions.

There is a difference between these two kinds of realism regarding the capacity of research to change the

world. A direct realist would state that the world is relatively unchangeable whereas a critical realist would

claim that the researcher’s understanding to that which is being studied could be changed. Many researchers

claim that what we explore is just part of the bigger picture. Thus researchers usually adopt a critical

realism point of view.

Interpretivism

Interpretivism claims that it is necessary for researchers to understand the differences between humans in

our role as social actors. We interpret our daily social roles in accordance with the meaning we give to these

roles. Interpretivism stems from two intellectual heritages

• Phenomenology considers the way in which we as humans make sense of the world around us

• Symbolic interactionism: we are all in a continual process of interpreting the social world we live in and

we interpret the actions of the people that interact with us. These interpretations lead to adjustments of

our own meaning and actions.

It is important for a researcher to understand the world of his research subjects and to understand the world

from their point of view.

Downloaded by Vikram (vikramaditya978@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5681783

Axiology

Axiology is a strand of philosophy that studies judgments about value. This includes values in the fields of

ethics and aesthetics. One’s own values play a crucial role in all stages of the research process. Our values

are the guiding line for all our actions (Heron 1996).

Research Paradigms

The term paradigm is frequently used in the social sciences, but it often leads to confusion because of its

many meanings. Here we define paradigm as a way of examining social occurrences from which particular

understandings of these phenomena can be gained and explanations attempted. In Figure 4.2 on page 141

there is an image of how the four paradigms can be arranged:

• Functionalist paradigm – this paradigm is frequently used in business management. Functionalists

assume that an organisation are rational entities, in which rational explanations will provide solutions to

rational problems.

• Radical structuralist paradigm – this paradigm is concerned with understanding structural patterns

within organisations (hierarchies for example) and reporting relationships and the extent to which these

relationships may produce dysfunctionalities.

• Interpretive paradigm – when adopting this paradigm one is concerned with understanding the

fundamental meanings attached to organisational life. Instead of rationalities this one wishes to

discover irrationalities. In this paradigm being involved in the everyday activities of the organisation in

order to understand and explain what is happening is more important that to try to change things.

• Radical humanist paradigm – this dimension adopts a critical perspective of organisational life. It

emphasises the consequences of one’s words and deeds on others. Working with this paradigm one

wishes to change things.

4.3 Research approaches

Deduction

Two main research approaches can be adopted when conducting research: deductive and inductive

approach. Deduction is the development of theory and hypotheses which are tested by using a research

strategy. Deductive reasoning is done when a conclusion is logically derived from a set of premises

(stellingen). The conclusion will be true when all these premises are proven to be true. There are 5 stages in

an inductive research:

1. Forming a hypothesis to form a theory

2. Deduce testable premises

3. Examine these premises and the logic of the argument that produced them, relate it to existing theories

4. Testing the premises by collecting data to measure variables or concepts

5. Analyze the results, If they are not consistent with the premises the theory is false and should be

rejected, or modified. If the results are consistent that a new theory is formed.

There exist four general characterizations for deduction

Downloaded by Vikram (vikramaditya978@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5681783

• Reliability. Every research should use a highly structured methodology, so that it is easy to replicate. If

this is the case the research is reliable.

• Concepts need to be operationalized in such a way that enables facts to be measured.

• Generalisation.

Induction

With inductive reasoning it is not true that when a set of premises are true that a clear conclusion can be

formed. This is because the conclusion is based on observations made by humans, and humans make

mistakes. A conclusion is therefore never guaranteed.

Abduction

A third approach, called abduction, starts with a conclusion: a surprise fact. With a set of premises one

subsequently tries to prove the conclusion. An abductive approach does not move from theory to data

(deduction) or from data to theory (induction), but rather moves back and forth between the two, combining

deduction and induction.

Downloaded by Vikram (vikramaditya978@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5681783

5.1 Introduction

A researcher must be able to explain why he chooses a particular research design. This justification should

be based upon the research questions and objectives and should also be consistent with his research

philosophies.

5.2 Choosing a research design

A research design is a general plan of how one will answer research questions. It includes clear objectives

derived from the research question, it displays the sources from which data will be collected and it will

explain how these data will be collected. This chapter will describe the different aspects of the formulation of

a research design:

• The research strategy: qualitative, quantitative or multiple methods

• The nature of the project: explanatory, descriptive or exploratory

• Methodological choice and related strategies

• Determining the time horizon of the research

• Ethical issues regarding the project

5.3 The research strategy : qualitative, quantattive or multiple methods

Quantitative research design

Often, the term ‘quantative’, is used to refer to a way to collect data or a procedure to analyse data that

generates or uses numerical data. Some characteristics:

• This research method is often associated with positivism. But may also be associated with

interpretivism when data is drawn from qualitative numbers.

• Quantative research is generally associated with a deductive approach, which means that the focus is

on using data to test a certain theory or certain theories. However, it could be associated with an

inductive approach in some cases.

• This method explores the relationships between variables after which they are measured numerically

and analysed using statistical techniques.

Qualitative research design

‘Qualitative’, is a term frequently used as a synonym for a way to a data collection technique or a procedure

to analyse data tat generates or uses non-numerical data. Some characteristics:

• This research method is often associated with an interpretive philosophy, because researchers need to

make sense of the phenomenon being studied. Qualitative research is often referred to naturalistic

research since it needs to be conducted in a natural setting, in order to gain trust, participation and

access to meanings and in-depth understanding

• Qualitative research can either be started with an inductive or a deductive approach. But in practice, an

abductive approach is frequently used.

• When conducting qualitative research, participants’ meanings and the relationships between them are

studied using data collection techniques and analytical procedures, to develop a conceptual framework.

• It is usually associated with action research, case study research and ethnography.

Downloaded by Vikram (vikramaditya978@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5681783

Multiple methods research design

Many management and business research designs are likely to combine qualitative and quantitative

elements. This is because some data derived from qualitative research may be analysed quantitavely, or

may be used to inform the design of another questionnarie. Quantative and qualitative research may be

seen as two ends of a continuum. Characteristics:

• Often associated with critical realism, since this philosophy advocates that while there is an objective

reality to the world we live in, the way in which each of us understand and interpret it will be affected

by our own social conditioning. It could also be associated with pragmatism .

• This method may use either an inductive or a deductive approach. Frequently both approaches are

used.

Figure 5.2 on page 165 shows an image of the different methodolocial choices one could make:

• Mono method: choosing either a quantitative or qualitative study

• Multiple methods: choosing both qualitative and qualitative study

o Multi method: more than one data collection technique is used but this is restricted to either

qualitative or quantitative design

o Mixed methods: both qualitative and quantitative design are mixed in a research design

5.4 Recognising the nature of a research design

There exist three research designs one could adopt when conducting research:

1. Exploratory study

This kind of study is a valuable way to ask open questions to discover what is going on and gain new

insights about a subject of interest. Conducting exploratory research is useful when one wishes to

understand something or wants to assess phenomena in a bright light. A view ways to conduct exploratory

research are:

1. To search literature

2. To interview experts

3. Conducting focus group interviews or individual interviews

2. Descriptive study

The purpose of a descriptive research is to acquire an accurate profile of happenings, people or situations. It

is possible for descriptive, explanatory and exploratory studies to coexist in one research project, where

they might extend one another. When conducing descriptive research one should be cautious, because

descriptive study may become too descriptive and may therefore lead to worthless outcomes. This is also

the reason why most descriptive studies are often combined with explanatory studies: after describing

something the research will provide a valuable explanation. This is referred to as descripto-explanatory

study.

3. Explanatory study

Downloaded by Vikram (vikramaditya978@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5681783

When performing this kind of study one wishes to determine causal relationships between certain variables.

5.5 Research strategies

Generally, a strategy is a plan of approach to achieve a certain goal. A research strategy could therefore be

defined as the various steps a researcher has to take to answer his research question. The choice of a

research question should be guided by one’s research question(s) and objective(s), the cohesiveness with

which these link to the research philosophy, research approach and purpose, and to more pragmatic

concerns such as the extent to existing knowledge and access to participants and other sources of data. The

following strategies will be discussed in this chapter (along with the research design that is linked to them):

Experiment

Quantitative research design only Survey

Archival Research

Qualitative research design only Case study

Ethnography

Action Research

Quantative, qualitative or both

Grounded Theory

Narrative Inquiry

Experiment

The experiment is a type of research that has been used frequently by natural scientist. The goal of an

experiment is to examine the probability of a change in an independent variable causing a change in

another, dependent variable (Hakim 2000). See table 5.2 on page 174 for the different variables and their

meanings. Instead of research questions, an experiment uses hypothesis (predictions). There are two kinds

of hypothesis in an experiment:

• Null hypothesis - which predicts that a significant difference or relationship between the variables does

not exist

• The alternative hypothesis - which predicts there is a relationship or difference

Downloaded by Vikram (vikramaditya978@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5681783

When performing an experiment, the null hypothesis is tested statistically. The null hypothesis will be

accepted when the probability that there is no statistical difference is greater than a prescribed value (most

of the times 0.05). In this case the alternative hypothesis will be rejected.

There are various experimental designs:

• Classical experiment – a group of participating people is selected and randomly assigned to either a

control or an experimental group. The experimental group will test a manipulation or intervention

(storing) and in the control group no such intervention is made. Because the control group is influenced

by the same external influences as the experimental group any changes to the dependent variable will

have to be caused by the intervention.

• Quasi experiment – also uses an experimental and control group, but the participants will not be

randomly assigned to a group. Matched pair analysis is when a participant in a control group will be

compared to a participant in the experimental group based on matching factors such as gender, age,

occupation etc. this is to create an even greater possibility that the intervention is the cause of change

to the variable.

• Within subject design/repeated measures design – this design uses only one single group to determine

change in a variable. Every participant will be subject to an intervention of the independent variable.

Before the intervention, all participants will be observed, a pre-intervention, to establish a baseline (or

control), after which a planned intervention of the independent variable and observation and

measurement of the dependent variable will follow. This research design requires much less participants

than others, but the side effects may be that the participants become tired or familiar with the

experiment.

Internal validity is the extent to which the findings of the experiment can be attributed to the interventions

instead of any flaws in the research design (such is the case with a laboratory experiment. External validity

is a lot more difficult to establish (when conducting field-based research).

Survey

This research strategy is usually associated with the deductive research approach. It is often used for

exploratory and descriptive research. Because most surveys use questionnaires it is easy for people to

understand and to explain. This is the reason why this kind of research design is so popular. Besides through

questionnaires, data for a survey strategy could also be collected through structured observation and

structured interviews. With a survey, quantative data is collected and be analyzed quantatively using

descriptive statistics. When using a sample one needs to be sure that the sample is representative to the

whole population.

Archival research

An archival research strategy uses administrative records and documents as the main source of data. Not

only historical but also recent data documents could be collected and analysed when adopting this strategy.

With use of an archival research strategy (research) questions with focus upon the past could be answered.

These questions may be exploratory, descriptive or explanatory.

Case study

Downloaded by Vikram (vikramaditya978@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5681783

A case study allows one to explore a research topic or phenomenon , within its context or within real-life

contexts. With a case study there is no clear boundary between that which is being studied (the

phenomenon or topic) and the context within which it is being studied (the real-life ‘case’). This approach is

useful when one wishes to gain a better understanding of the research and a certain phenomenon ,

especially when one wishes to explore existing theory. Below are some characteristics of case studies:

• It is most often used in exploratory and explanatory research.

• Case study research could combine qualitative and quantative methods such as questionnaires and

interviews. The use of different data collection techniques within one study to be sure that the data are

telling you what you think they tell you is called triangulation.

• It is possible to use multiple cases within one case study, this is termed literal replication. The cases will

be chosen in such a way that similar results are predicted to be produced from each one. Theoretical

replication is when a contextual factor is deliberately different in a certain set of cases. This approach of

case study is done deductively.

• Holistic case study – when research is focussed on the organisation as a whole

• Embedded case study – when research is focussed on sub units within an organisation and the case will

involve more than one unit of analysis.

Ethnography

This approach is used to study particular groups of people. When conducting ethnographic research one

wishes to explore and analyse people in groups who share the same space (this could be the same street,

work group, organisation or even society) and who interact with each other. Cunliffe distinguishes three

ethnographic strategies:

• Realist Ethnography – this is an objective, factual strategy which wishes to identify ‘true’ meanings.

People are being observed through facts or data about structures and processes, routines and norms,

practices and customs, artefacts and symbols (Cunliffe 2010). A realist ethnographer writes in third

person, which displays his role as impersonal reporter of facts.

• Impressionist/Interpretive Ethnography – this ethnographic strategy is in contrast with realist

ethnography since impressionist ethnography focusses on subjectivity rather than on objectivity.

Participants are treated like people rather than just subjects, this is the reason why Tedlock (2005) calls

the interpretive ethnographic strategy ‘the observation of participation’. Since the Instead of one

definite meaning, an interpretive ethnographic believes that it is likely that multiple meanings exist. The

interpretive ethnographer writes his report in first person and uses method such as personalisation,

dialogues, quotations, dramatization etc.

• Critical Ethnography – this strategy is designed to analyse and explain the impact of power, privilege

and authority on the people who are subject to these influences.

Action Research

This type of research strategy designed to develop answers to real organisational problems by using a

participative and collaborative approach which uses various forms of knowledge. Action research will

Downloaded by Vikram (vikramaditya978@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5681783

influence the participants and the organisation beyond the research project. As Greenwood and Levin said:

action research is a social process in which a researcher works with members of an organisation to enhance

their situation and their organisation. This type of research has 5 themes:

1. Purpose – the purpose of action research is to promote organisational learning to produce practical

outcomes through identifying issues, planning action, taking action and evaluating action (Coghlan and

Brannick).

2. Process – the process of action research starts with a particular context and with a research question,

but because it moves through several stages (See figure 5.4 on page 183) the focus may change as the

research develops. Each stage of the process begins with diagnosing or constructing ideas, planning,

taking action and finally evaluating action. This cycle will be repeated several times.

3. Participation – this component of action research is critical. For Greenwood and Levin action and

participation are essential parts of an Action Research process. One of the reasons why this is the case

is because the members of an organisation need to cooperate with the researcher and enable him to

study their existing work. Moreover, the participants are required to participate in the form of

collaboration though the cycles to allow any improvement in the organisation to occur. Without

participation this type of research would not be able to work. Action Research enables bottom up

culture change, because organisational members are more likely to implement change they have helped

to develop. Therefore, members of an organisation become more engaged and more willing to make

decision.

4. Knowledge – different forms of knowledge: theoretical, propositional, lived experiences of participants

and knowing-in-action knowledge. The last type of knowledge comes from practical application. All

these kinds of knowledge will be incorporated into each of the stages of the Action Research process.

5. Implications – One of the implications of Action Research is that participants will raise their expectations

about their future treatment (since they are so involved with the organisation). Another implication is

that the organisation will develop and its culture will change. Also researchers could use the results

from this research and use it to develop theory to inform other contexts.

Grounded theory

Grounded theory is a theory developed from a set of data (using an inductive approach). It was developed

as a way to analyse, interpret and explain the meanings that social actors construct to make sense of their

daily experiences in particular situations. There are three stages:

1. Open coding – reorganising data into categories

2. Axial coding – determining relationships between categories

3. Selective coding – the integration of categories to produce theory

During all these stages of coding the researcher is constantly comparing each item of data with others.

Constantly coding involves moving between inductive (data to theory) and deductive (theory to data)

thinking: while discovering relationships between codes and interpreting them the researcher is thinking

inductively (he develops his own theory from the relationships between codes). This interpretation needs to

be tested by collecting data from other cases, which means that the researcher is thinking deductively

because he tests his ‘theory’(interpretation) with other data. This is known as the process of abduction.

Downloaded by Vikram (vikramaditya978@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5681783

With the Grounded Theory strategy, sampling is not meant to achieve representativeness but rather to focus

the research on a core theme, relationship or process. This approach is known as theoretical sampling which

ends when theoretical saturation/conceptual destiny is reached. This happens when the data collection does

not continue to reveal any new properties relevant to a category, where categories have become well

developed and understood and relationships between categories have been verified (Straus and Corbin

2008).

Narrative inquiry

The term narrative means story or a personal account which interprets an event or sequence of events

(Saunders 2012). Narrative inquiry refers to a research strategy where a researcher believes that the

experiences of his participants can best be accessed by collecting and analysing these as stories. Narrative

inquiry preserves any chronological connection and sequence of events as told by the participant. In this

way the reader may find it more easy to understand the report and the researcher is able to provide his

interpretation of the events.

With Narrative Inquiry the participant is the narrator of a story about an event, work project, managing or

setting up a business, or organisational change. It may be used in combination with other strategies as

complementary approaches.

5.6 A Time Horizon

Cross Sectional studies

When a research is more like a ‘snapshot’ taken at a certain time then it’s called cross-sectional. These kind

of studies often use the survey strategy, where an incidence of a phenomenon may be described or where

may be explained how different factors in different organisation are related.

Longitudinal studies

Is the research reported more like a ‘diary’ which represents the events over a specific period than it’s called

longitudinal. The advantage of this time horizon is that it’s able to study change and development.

5.7 The ethics of Research

When choosing a subject for a research project one needs to consider the ethics. Some topics have more

ethical difficulties than others. One needs to be sure that ethical issues will not be disadvantageous

(harmful, embarrassing, painful) to participants. Moreover, the participants need to be aware of that they

are subject of research.

5.8 Quality of Research

To ensure quality in any scientific research one needs to consider the ‘canons of scientific inquiry’:

• Reliability – a reliable research is reproducible, meaning that the data collection techniques and analytic

procedures would produce the same findings if they were repeated by some one else or another time.

In order to be reliable one has to work in a structured and methodological way.

• Construct validity – the extent to which the research measures actually measured what the researcher

intended them to assess.

• Internal validity – this is the case when the research displays a causal relationship between two

variables.

Downloaded by Vikram (vikramaditya978@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5681783

• External validity – Concerned with questions such as: “Are the research findings generalised?”, “Would

a researcher find the same in other relevant settings or groups?”.

Alternative criteria to asses quality of research

The ‘canons of scientific inquiry’ are most suitable with quantative, positivist methods. Researchers who

undertake a qualitative research may find it difficult cover the four criteria listed above, because they may

not be suitable to their kind of research. As an answer to this problem, Lincoln and Guba, have formulated

new names for the ‘canons of scientific inquiry’: dependability instead of reliability, credibility for internal

validity and trasferability instead of external validity. Moreover, Lincoln and Guba have also developed a new

set of criteria named ‘authenticity criteria’.

5.9 The role of the researcher

Full-time students usually adopt the role of an external researcher. This is someone who needs to identify an

organisation within which he conducts his research. The researcher is external to the organisation therefore

he has to negotiate with its members to be able to access the organisation and to collect its data.

An internal/practitioner researcher is one who works in an organisation. The advantage of this is that the

researcher has easy access to the organisation. Plus, he is also likely to have knowledge of the organisation

and therefore understands the complexity of what is happening in that organisation. This may also be a

disadvantage since the external researcher’s assumptions and preconceptions may be different from reality.

Downloaded by Vikram (vikramaditya978@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5681783

Before conducting research, a researcher need to be sure he will have access to the data he needs and he

has to think carefully about the possible ethical difficulties he might face. Because business and

management research will inevitably make use of human participants ethical concerns will almost always

rise.

6.2 Gaining access

There are different types of access to data:

1. Traditional access- this may refer to face-to-face interaction, conversations, correspondence or visiting

data archives.

2. Internet-mediated access – this involves the use of a computer, or computer technologies such as the

Web, email and webcams to be able to gain access to questionnaires, discussions, experiments or

interviews or to gather secondary data.

3. Intranet-mediated access – a variant of internet-mediated access where one gains virtual access as an

organisational employee or worker using its intranet.

4. Hybrid access – this type of access combines traditional and internet-mediated approaches.

The levels of access may vary because the depend on the nature and depth of the access one wishes to

achieve: physical, continuing and cognitive access. Physical access may be difficult because it not all

organisations are prepared to engage in activities which are not necessary for them, since time and effort is

required. Sometimes the gatekeeper (the person who keeps data and decides who may have access to it)

does not allow people to undertake the research (because the organisation does not receive value from it or

the topic is to sensitive).

Many people see access to data as a continuing process and not just one single event. One of the two

reasons for this is that access may be an iterative (herhalend) and incremental (stapsgewijs oplopend)

process. After gaining access to one particular set of data one might seek further to achieve other data in

order to conduct another part of the research. Another reason why access is a continuing process is because

those people from whom one needs to collect data may be different to those who agreed to your request for

access (gatekeepers).

Physical access to data from of an organisation will be granted in a formal manner, though an organisations

management. Therefore it is useful to gain trust from the organisational members. This type of access is

named cognitive access.

Negotiating access

Negotiating access is likely to be an important if one wishes to gain personal entry to an organisation and to

be able to have cognitive access to allow one to connect the necessary data. Therefore it is important to

consider the project’s feasibility (determine whether it is practicable to negotiate access for a research

project) and sufficiency (whether one is able to gain sufficient access to fulfil the research objectives).

Issues of being an external researcher

Researchers need to negotiate access at each level: physical, continuing and cognitive. Because an external

researcher lacks status in an organisation or group in which he wishes to conduct research he will face

difficulties at every level of access. Therefore external researchers rely on the goodwill of the organisational

members. To be able to gain goodwill from members a researcher needs to be able to communicate his

competence and integrity and explain the importance of his research project clearly and precisely.

Issues of being an internal/participant researcher

Even though an internal or participant researcher is familiar with the organisation and vice versa, he is still

Downloaded by Vikram (vikramaditya978@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5681783

likely to face problems of access to data. The status of an internal/participant researcher who wishes to gain

cognitive access could cause suspicions. This is because other organisational members may not know what

the internal/participant researcher will do with the data. Here it is also important for the researcher to be

able to communicate the purpose of his research.

6.4 Strategies for gaining access

This section will discuss the different strategies one could use to obtain access to data for traditional as well

as internet-mediated means. The applicability of these strategies will differ in relation to the researcher’s

status as an internal or external researcher. Table 6.1 on page 217 displays a number of different strategies.

Familiarity with the group and sufficient time

Before trying to obtain physical access it is very important for a researcher to familiarise himself with the

organisation or group. It may take a lot of time (weeks or even months) before physical access could be

gained (if access is even granted at all). This is the reason why a researcher needs to plan sufficient time for

the data access part of a research project. One also needs to consider the time needed for a participant to

respond to the request of participating in a research.

Using existing contacts and/or developing new ones

When a researcher is able to use existing contacts it is easier to gain access. Because these contacts have

knowledge of the researcher means that they can trust him and his intentions and are therefore likely to

gain access to the data.

Providing clear account of requirements for participators

Researchers need to be aware that they provide a clear report of their requirements to allow their

participants to know what will be asked of them. Without clear requirements, participants may act cautious

since the required amount of time they have to put in their participation may seem to be disruptive. This is

why an introductory letter to the participants will have to provide them with an outline and goal of the

research and what the participants will have to do.

Overcoming organisational concerns

Organisations may be concerned about:

• The amount of time or resources involved in the request for access - the less the better

• The sensitivity about the topic - negative implications are less likely to lead to granting access, thus

highlight positive approach.

• The confidentiality of the data and the anonymity of the organisation need to be ensured.

Possible benefits to organisation granting access and using suitable language

Organisations and their members may find it helpful to discuss their own situation in a non-threatening,

non-judgemental environment. Therefore it may be helpful to provide a summary report of one’s findings to

those who grant access. One should also be aware that the use of language is important and should depend

on the nature of the people who participate.

Facilitating replies, developing access, and establishing credibility

Different contact methods could be used to write requests for access (phone, skype, fax, email), but these

may not be suitable in all cases. When using an incremental strategy (from minimum requirements of

participants to more requirements) one is able to obtain access to a certain level of data and a positive

Downloaded by Vikram (vikramaditya978@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5681783

relationship with participants will rise. As one establishes credibility he can develop the possibility of

achieving a fuller level of access.

6.5 Research ethics

Ethics refer to the standards of behaviour that guide your conduct in relation to the rights of those who

become subject of your work, or are affected by it and usually accompanied by social norms(Saunders

2012). A social norm is an indicator of the type of behaviour an individual should adopt in a specific

situation.

Two conflicting philosophical positions have been identified with regard to ethics:

• Deontological view – following rules to guide researcher’s conduct. When one acts outside these rules it

can never be justified

• Teleological view – deciding whether an act is justified should be determined by its consequences and

not by predetermined rules.

‘Codes of ethics’ were developed to overcome ethical dilemmas arising from various social norms. Codes of

ethics are a list of principles which outlines the nature of ethical research and a statement of ethical

standards.

Many universities have research ethics committees to ensure that research conducted by students is non-

controversial and pose minimal risk to participants. Research ethics committees review all research

conducted by those in the institution that involves human participation and personal data. Table 6.3 on page

231 and 232 provides the general principles developed to recognise ethical issues.

Ethical issues associated with internet-mediated research

A list of general ethical issues associated with Internet-mediated research is listed below:

• Scope for deception

• Lacking respect and causing harm

• Respecting privacy

• Nature of participation and scope to withdraw

• Informed consent

• Confidentiality of data and anonymity of participants

• Analysis of data and reporting the findings

• Management of data

• Safety of data and reporting findings

The term netiquette refers to ‘net etiquette’, or in other words the social standards which one should use

online. Netiquette concerns the use of emails and messaging since they may be poorly worded and may

seem unfriendly or unclear to the receiver.

6.6 Ethical issues during the specific stages of the research process

Figure 6.1 on page 236 sums up the different ethical issues that could rise at specific stages of the research

process. Most ethical issues can be predetermined and dealt with during the design stage of a research

process. One should be sure that the intended research is in line with the ethical principle of not causing any

harm to participants. When seeking access a researcher should not put any pressure on the members of an

Downloaded by Vikram (vikramaditya978@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|5681783

organisation, since this might be unpleasant to them.

When approval for access is given, one should ensure the participants that personal data will be handled

anonymously and confidentially. There is of continuum for the range of approval that could be given.

1. The continuum starts with complete lack of consent – this is the case when participants may fear

deception from the researchers part

2. Through inferred consent - the participant makes an agreement which states that he has control over

the way the data is analysed, used, stored and reported

3. And ends with informed consent - participants are fully informed and may ask questions whenever they

want

Moreover, the participants need to be fully aware of the information that is asked from them. A researcher

needs to inform them of this formally with the use of a participant information sheet. It has to include the

requirements and implications of participating, the nature of research, how the data will be analysed,

reported and stored and who to contact when any concerns rise. A more detailed written agreement could

be established as a consent form, which both parties should sign. Consent forms help clarifying boundaries

of consent.

Ethical issues during data collection

Once participants or organisations have approved to take part in a research they maintain certain rights.

These include that they may withdraw from the research at any point they want and that the researcher

should keep the aims of his research project that he agreed, if this is not the case he is deceiving the

participants. Moreover, a researcher should not ask of participants to participate in something that will cause