Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Nursing Gyne Assessment PDF

Nursing Gyne Assessment PDF

Uploaded by

faria ejazCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Osce Basil.Document304 pagesOsce Basil.AsuganyadeviBala95% (19)

- 30 Main Nogier PointsDocument3 pages30 Main Nogier PointsCarissa Nichols100% (4)

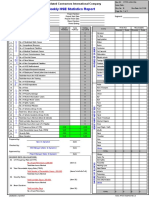

- Hse Statistics Report Pp701 Hse f04 Rev.bDocument1 pageHse Statistics Report Pp701 Hse f04 Rev.bMohamed Mouner100% (1)

- Medip, IJRCOG-8374 ODocument6 pagesMedip, IJRCOG-8374 Oalaesa2007No ratings yet

- Guia Canadience Uso de Mallas VaginalesDocument13 pagesGuia Canadience Uso de Mallas VaginalesGiuliana Cuadros PeñalozaNo ratings yet

- What S New in Guidance - Urinary Incontinence and Pelvic Organ Prolapse NICE NG123 - TOG April 2024Document2 pagesWhat S New in Guidance - Urinary Incontinence and Pelvic Organ Prolapse NICE NG123 - TOG April 2024Myint Su MgNo ratings yet

- Evaluate The Effectiveness of Structured Teaching Program Regarding Menopausal Syndrome Among The Peri Menopausal Women in Bandarulanka, Amalapuram, Andhra PradeshDocument9 pagesEvaluate The Effectiveness of Structured Teaching Program Regarding Menopausal Syndrome Among The Peri Menopausal Women in Bandarulanka, Amalapuram, Andhra PradeshInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Initial Investigation and Managenement Benign Ovariam MassesDocument12 pagesInitial Investigation and Managenement Benign Ovariam MassesleslyNo ratings yet

- Journal Obgyne DR - ApDocument6 pagesJournal Obgyne DR - Apoktaviana54No ratings yet

- Guideline No. 437 - Diagnosis and Management of AdenomyosisDocument14 pagesGuideline No. 437 - Diagnosis and Management of Adenomyosisina.popescu89No ratings yet

- Assessment of The Qualıty of Lıfe in Women Wıth A Dıagnosıs of Urogenıtal ProlapseDocument8 pagesAssessment of The Qualıty of Lıfe in Women Wıth A Dıagnosıs of Urogenıtal ProlapseQuynh Giang Nguyen LeNo ratings yet

- Adult Urodynamics Guideline PDFDocument30 pagesAdult Urodynamics Guideline PDFVlad ValentinNo ratings yet

- AUB 2012 SSDSDDDDDDDDDocument7 pagesAUB 2012 SSDSDDDDDDDDPitra Mukhlis WardaniNo ratings yet

- Quantitative Measures of Self-Reported Data On Abortion Morbidity: A Case Study in Madhya Pradesh, IndiaDocument10 pagesQuantitative Measures of Self-Reported Data On Abortion Morbidity: A Case Study in Madhya Pradesh, IndiaHeather HennessyNo ratings yet

- Guideline No. 414: Management of Pregnancy of Unknown Location and Tubal and Nontubal Ectopic PregnanciesDocument18 pagesGuideline No. 414: Management of Pregnancy of Unknown Location and Tubal and Nontubal Ectopic PregnanciesAmel Zaouma100% (1)

- SAGES Guidelines For The Use of Laparoscopy During PregnancyDocument16 pagesSAGES Guidelines For The Use of Laparoscopy During Pregnancymaryzka rahmadianitaNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Urinary Incontinence in The 12-Month Postpartum Period and Related Risk Factors in TurkeyDocument8 pagesPrevalence of Urinary Incontinence in The 12-Month Postpartum Period and Related Risk Factors in TurkeyMoenaIsmailNo ratings yet

- Der Chi 2001Document19 pagesDer Chi 20013bood.3raqNo ratings yet

- Amsterdam Placental WorkshopDocument16 pagesAmsterdam Placental WorkshopCarlos Andrés Sánchez RuedaNo ratings yet

- 14 Vol. 11 Issue 11 Nov 2020 IJPSR RE 3646Document7 pages14 Vol. 11 Issue 11 Nov 2020 IJPSR RE 3646Ehwanul HandikaNo ratings yet

- Awareness of Patients With Symptomatic Gallstones Regarding Their Own DiseaseDocument3 pagesAwareness of Patients With Symptomatic Gallstones Regarding Their Own DiseaseHelenCandyNo ratings yet

- The Gynecologic History and Pelvic Examination Up To Date 2016Document14 pagesThe Gynecologic History and Pelvic Examination Up To Date 2016Mateo GlNo ratings yet

- Transvaginal Ultrasonography and Female InfertilityDocument76 pagesTransvaginal Ultrasonography and Female InfertilityDavid MayoNo ratings yet

- The Prevalence of Congenital Uterine Anomalies in Unselected and High-Risk Populations A Systematic ReviewDocument11 pagesThe Prevalence of Congenital Uterine Anomalies in Unselected and High-Risk Populations A Systematic ReviewMoustafa KamelNo ratings yet

- Evidence-Based Management of Endometrioma: Tarek A Gelbaya, Luciano G NardoDocument10 pagesEvidence-Based Management of Endometrioma: Tarek A Gelbaya, Luciano G NardofebrianoramadhanaNo ratings yet

- Mehu108 U4 T4 Anomalias Congénitas3Document34 pagesMehu108 U4 T4 Anomalias Congénitas3Michael Rodrigues HaroNo ratings yet

- Spectrum of Symptoms in Women Diagnosed With Endometriosis During Adolescence Vs AdulthoodDocument11 pagesSpectrum of Symptoms in Women Diagnosed With Endometriosis During Adolescence Vs AdulthoodnicloverNo ratings yet

- Predisposing Factors and Demographic Analysis in Inguinal HerniaDocument4 pagesPredisposing Factors and Demographic Analysis in Inguinal HerniaKarl PinedaNo ratings yet

- ICSIUGA Joint Report On The Assessment of Sexual Health of Woman 2018Document21 pagesICSIUGA Joint Report On The Assessment of Sexual Health of Woman 2018sivakumarNo ratings yet

- Gynae ClinDocument10 pagesGynae ClinUmut KNo ratings yet

- FIGO Classification System PALM-COEIN For Causes oDocument12 pagesFIGO Classification System PALM-COEIN For Causes oEdwin SondakhNo ratings yet

- crowley2009 - вагинизмDocument6 pagescrowley2009 - вагинизмxobekon323No ratings yet

- Sultan Et Al-2017-Neurourology and UrodynamicsDocument25 pagesSultan Et Al-2017-Neurourology and UrodynamicsMikhail NurhariNo ratings yet

- Incontinencia FecalDocument11 pagesIncontinencia FecalDiego MarzaroliNo ratings yet

- Abnormal Uterine Bleeding in Perimenopausal WomenDocument15 pagesAbnormal Uterine Bleeding in Perimenopausal WomenOrchid LandNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Neck MassDocument17 pagesEvaluation of Neck MassMuammar Aqib MuftiNo ratings yet

- LANCET - 1 - Time For A Balanced Conversation About Menopause (Hickney Et Al., 2024)Document11 pagesLANCET - 1 - Time For A Balanced Conversation About Menopause (Hickney Et Al., 2024)Rebeca PeñuelaNo ratings yet

- A Prática de Exercícios Físicos É Um Fator Modificavel Da Incontinencia Urinaria de Urgencia em Mulheres IdosasDocument17 pagesA Prática de Exercícios Físicos É Um Fator Modificavel Da Incontinencia Urinaria de Urgencia em Mulheres Idosasbacharelado2010No ratings yet

- Urinary Incontinence With StrokeDocument8 pagesUrinary Incontinence With StrokeJamaicaNo ratings yet

- Aub 1Document3 pagesAub 1Nadiah Baharum ShahNo ratings yet

- Art 3A10.1007 2Fs00192 017 3304 9Document6 pagesArt 3A10.1007 2Fs00192 017 3304 9Khaleed KandaraNo ratings yet

- History Taking and Clinical Examination For Ong Patients 2Document19 pagesHistory Taking and Clinical Examination For Ong Patients 2Shangai GuptaNo ratings yet

- Yeung TeenagersDocument5 pagesYeung TeenagersAnonymous YyLSRdNo ratings yet

- Hope, Burden or Risk FPDocument24 pagesHope, Burden or Risk FPDolores GalloNo ratings yet

- Ultrasound Detected Ovarian Cysts For Nuh Gynaecology TeamsDocument11 pagesUltrasound Detected Ovarian Cysts For Nuh Gynaecology TeamsDirga Rasyidin LNo ratings yet

- A Suggested Approach For Implementing CONSORT Guidelines Specific To Obstetric ResearchDocument5 pagesA Suggested Approach For Implementing CONSORT Guidelines Specific To Obstetric ResearchminhhaiNo ratings yet

- Vaginal Discharge and Associated Views Among Women Attending Gynaecological OPDDocument2 pagesVaginal Discharge and Associated Views Among Women Attending Gynaecological OPDdkhatri01No ratings yet

- Guideline No. 402 Diagnosis and Management of Placenta PreviaDocument13 pagesGuideline No. 402 Diagnosis and Management of Placenta PreviaAndrés Gaviria C100% (1)

- Guideline No. 422b: Menopause and Genitourinary Health: Sogc Clinical Practice GuidelineDocument8 pagesGuideline No. 422b: Menopause and Genitourinary Health: Sogc Clinical Practice GuidelineGabino Alexander Liviac CrisostomoNo ratings yet

- YOUNG 2017 Clinicians' Perceptions of Women's ExperiencesDocument6 pagesYOUNG 2017 Clinicians' Perceptions of Women's ExperiencesCristiane HermesNo ratings yet

- JejeuryDocument5 pagesJejeuryRizka YusraNo ratings yet

- Hum. Reprod.-2005-Kennedy-2698-704Document7 pagesHum. Reprod.-2005-Kennedy-2698-704MariaJimenaPalaciosNo ratings yet

- Literature Review EpisiotomyDocument6 pagesLiterature Review Episiotomyafmztopfhgveie100% (1)

- Hiperplasia EndometrialDocument12 pagesHiperplasia EndometrialJulián LópezNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Urinary IncontinenceDocument6 pagesLiterature Review Urinary Incontinenceea68afje100% (1)

- Causes of Amenorrhea in Korea: Experience of A Single Large CenterDocument4 pagesCauses of Amenorrhea in Korea: Experience of A Single Large CenterNadya MagfiraNo ratings yet

- Knowledge and Practice of Cervical Cancer Screening Amongst Nurses in Ahmadu Bello University Teaching Hospital ZariaDocument9 pagesKnowledge and Practice of Cervical Cancer Screening Amongst Nurses in Ahmadu Bello University Teaching Hospital ZariafxbukenyaNo ratings yet

- Menstrual Disorders Among Zagazig University Students, Zagazig, EgyptDocument6 pagesMenstrual Disorders Among Zagazig University Students, Zagazig, EgyptErsi Dwi Utami SiregarNo ratings yet

- Norton 2014Document5 pagesNorton 2014Gladys SusantyNo ratings yet

- Practic Buletin Early Pregnancy Loss PDFDocument10 pagesPractic Buletin Early Pregnancy Loss PDFsiantan ngebutNo ratings yet

- Family History As A Risk Factor For Pelvic Organ Prolapse: Original ArticleDocument7 pagesFamily History As A Risk Factor For Pelvic Organ Prolapse: Original ArticlepakemainmainNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Problems in Tumors of Female Genital Tract: Selected TopicsFrom EverandDiagnostic Problems in Tumors of Female Genital Tract: Selected TopicsNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Problems in Tumors of Gastrointestinal Tract: Selected TopicsFrom EverandDiagnostic Problems in Tumors of Gastrointestinal Tract: Selected TopicsNo ratings yet

- 18-400 AppbDocument21 pages18-400 Appbfaria ejazNo ratings yet

- Marine Accident Investigation Report: October 25, 2018Document34 pagesMarine Accident Investigation Report: October 25, 2018faria ejazNo ratings yet

- Merchant Shipping Act 1985 Merchant Shipping (Modu Code) Regulations 1997Document7 pagesMerchant Shipping Act 1985 Merchant Shipping (Modu Code) Regulations 1997faria ejazNo ratings yet

- Menstrual DysfuntionDocument49 pagesMenstrual Dysfuntionfaria ejazNo ratings yet

- The Continuous Professional Development of School Principals: Current Practices in PakistanDocument23 pagesThe Continuous Professional Development of School Principals: Current Practices in Pakistanfaria ejazNo ratings yet

- ARCCPDToolkitApril2014 000Document60 pagesARCCPDToolkitApril2014 000faria ejazNo ratings yet

- The Family Client: Home VisitDocument38 pagesThe Family Client: Home Visitfaria ejazNo ratings yet

- Ch12-Ec2e2n Boochk-201511-Guidebook Goodpractice 4pstctDocument16 pagesCh12-Ec2e2n Boochk-201511-Guidebook Goodpractice 4pstctfaria ejazNo ratings yet

- HAJRA QuestDocument6 pagesHAJRA Questfaria ejazNo ratings yet

- Reproductive Health and Responsible Sexuality: Mindanao Young Women Leaders CongressDocument25 pagesReproductive Health and Responsible Sexuality: Mindanao Young Women Leaders Congressfaria ejazNo ratings yet

- Consulting The Oracle: Ten Lessons From Using The Delphi Technique in Nursing ResearchDocument8 pagesConsulting The Oracle: Ten Lessons From Using The Delphi Technique in Nursing Researchfaria ejazNo ratings yet

- Views of Midwives and Gynecologists On Legal Abortion - A Population-Based StudyDocument7 pagesViews of Midwives and Gynecologists On Legal Abortion - A Population-Based Studyfaria ejazNo ratings yet

- Coetzee2013 PDFDocument12 pagesCoetzee2013 PDFfaria ejazNo ratings yet

- IIE Transactions On Healthcare Systems EngineeringDocument14 pagesIIE Transactions On Healthcare Systems Engineeringfaria ejazNo ratings yet

- Congenital Heart DefectsDocument73 pagesCongenital Heart DefectsStaen KisNo ratings yet

- Future Perfect and Cont TestDocument2 pagesFuture Perfect and Cont TestEdit GöröcsNo ratings yet

- Article in Press: Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Medicine, and PathologyDocument7 pagesArticle in Press: Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Medicine, and PathologyNizajaulNo ratings yet

- CH 15Document8 pagesCH 15naguguNo ratings yet

- Application of Reflection of Sound WavesDocument17 pagesApplication of Reflection of Sound Wavesalias_acaiNo ratings yet

- Anatomy, Autonomic Nervous System - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocument10 pagesAnatomy, Autonomic Nervous System - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelfwood landerNo ratings yet

- Assignment # 01 Pharmacology: Presented By: Zoha Abid Submitted To: DR MalihaDocument10 pagesAssignment # 01 Pharmacology: Presented By: Zoha Abid Submitted To: DR MalihaLaraibNo ratings yet

- Micu MedsDocument3 pagesMicu MedsanreilegardeNo ratings yet

- Science NotesDocument2 pagesScience NotesSofia JeonNo ratings yet

- Yoga Therapy ConceptDocument32 pagesYoga Therapy ConceptKirthika R100% (2)

- Case Study and Care Plan FinalDocument14 pagesCase Study and Care Plan Finalapi-238869728No ratings yet

- Birth AsphyxiaDocument20 pagesBirth Asphyxiainne_fNo ratings yet

- Nail Diseases and DisordersDocument45 pagesNail Diseases and DisordersMariel Balmes HernandezNo ratings yet

- AcalyphineDocument1 pageAcalyphinearidwanulohNo ratings yet

- Mind Speak To Us Interactive Lesson Plan 3Document15 pagesMind Speak To Us Interactive Lesson Plan 3PrakashNo ratings yet

- DR - Tateishi's Cancer Healing Formula: What This Remedy May DoDocument8 pagesDR - Tateishi's Cancer Healing Formula: What This Remedy May DoCheri HoNo ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument6 pagesCase Studyapi-276551783No ratings yet

- She Jan 2010Document122 pagesShe Jan 2010shemagononlyNo ratings yet

- Handbookof Autismand AnxietyDocument2 pagesHandbookof Autismand AnxietyJelena JokićNo ratings yet

- Cerebral PalsyDocument24 pagesCerebral PalsyBam ValleserNo ratings yet

- 01 Congenital Diseases of The External and Middle Ear-1Document39 pages01 Congenital Diseases of The External and Middle Ear-1cabdinuux32No ratings yet

- NCM 116 Lab Activity 2 NCP 1 Git PabrnmanDocument6 pagesNCM 116 Lab Activity 2 NCP 1 Git Pabrnmanjericho dinglasanNo ratings yet

- Regis Mani AAOMPT Poster 2008Document1 pageRegis Mani AAOMPT Poster 2008smokey73No ratings yet

- (Chinyanja) Chewa - English Dictionaryvermeullen PDFDocument72 pages(Chinyanja) Chewa - English Dictionaryvermeullen PDFEugênio C. Brito100% (1)

- SURGERY Revalida Review 2019Document78 pagesSURGERY Revalida Review 2019anonymousNo ratings yet

- Drug Study: Valerie V. Villanueva BN3-CDocument1 pageDrug Study: Valerie V. Villanueva BN3-CValerie VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Geria ReviewerDocument7 pagesGeria ReviewerCarl John ManaloNo ratings yet

Nursing Gyne Assessment PDF

Nursing Gyne Assessment PDF

Uploaded by

faria ejazOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Nursing Gyne Assessment PDF

Nursing Gyne Assessment PDF

Uploaded by

faria ejazCopyright:

Available Formats

Art & science | advanced practice

Gynaecological assessment

and history taking

Anthony Summers describes how nurse practitioners

should undertake pelvic examinations, and

outlines significant signs and symptoms

Correspondence

about their gynaecological histories, and the

anthony_summers@health.qld.gov.au Abstract

prospect of physical examination. This anxiety and

Anthony Summers is a nurse Nurse practitioners (NPs) rarely undertake embarrassment can be more pronounced if they

practitioner at Redlands Hospital,

Queensland, Australia

gynaecological histories or female genital examinations have had bad or no experiences of such procedures,

yet, by doing so, they can broaden their scope of or they have histories of trauma or injury

Date of submission practice. This article discusses what NPs should (Huber et al 2009). The confident manner in which

May 3 2013

ask women about their gynaecological histories and NPs approach such patients and explain everything

Date of acceptance how to undertake pelvic examinations, and reviews before proceeding can go a long way to alleviating

July 10 2013 common gynaecological symptoms. Further articles such fears and concerns.

Peer review

will cover different aspects of the pelvic examination The presence of chaperones can also help to

This article has been subject and potential differential diagnoses. ensure patients feel comfortable (Bates et al 2011)

to double-blind review and

and some chaperones can help with examinations.

has been checked using

antiplagiarism software

Keywords In the UK, the Nursing and Midwifery Council

Gynaecological history, pelvic examination, obstetrics (NMC) (2012) states that patients have the right to

Author guidelines

request chaperones when undergoing procedures

www.emergencynurse.co.uk

TAKING GYNAECOLOGICAL histories and or examinations, and most female patients prefer

undertaking physical examinations can be to have chaperones present when examiners are

challenging tasks for nurse practitioner (NPs). male (Fiddes et al 2003, Shawn and Upshur 2008).

They and the patients concerned may be There are no guidelines advocating that there

embarrassed during the processes, and patients should always be chaperones present, however, and

may have unrealistic expectations about the no evidence that their presence makes litigation

examinations. Some patients know less about how less likely. In addition, their presence during history

their bodies function, are less comfortable about taking can make patients feel embarrassed about

revealing parts of their bodies and are less willing revealing their sexual or gynaecological histories to

to discuss their sexual histories than other patients, other people. It is therefore recommended that male

while some may think that discussing these topics examiners use chaperones routinely, that female

with men socially or culturally inappropriate (Carusi examiners ask patients if they would like chaperones

and Goldstein 2013). to be present and that individual patient preferences

The aim of this article is to provide NPs with are documented (Bates et al 2011). Each emergency

the necessary skills and knowledge to take department (ED) should have guidelines about

gynaecological histories and undertake physical chaperoning patients.

examinations of adult women, here defined

as women aged over 18 years. The article will Gynaecological history

allow them to approach such situations without Before examination, patient histories should be

embarrassment and thereby reassure their patients taken to discover important information about

that they are being treated professionally. patients and their presenting problems (Bridge

Many women are anxious or embarrassed 2011). Histories should be taken in private areas

32 September 2013 | Volume 21 | Number 5 EMERGENCY NURSE

Downloaded from RCNi.com by ${individualUser.displayName} on Jan 31, 2016. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2016 RCNi Ltd. All rights reserved.

because it is likely that many sensitive issues will be ■■ Papanicolaou, or pap, test history. This includes

discussed. Nurse practitioners should avoid making whether the patient has had one recently, whether

assumptions about patients’ backgrounds and the results were normal or abnormal and what

remain sensitive and non-judgemental throughout follow up was needed.

the history taking process (Carusi and Goldstein ■■ History of gynaecological problems, of which the

2013). History taking should begin with general presenting conditions may be exacerbations.

open-ended questions to allow patients to express ■■ Vaginal prolapse: whether the patient feels a

what they are concerned about in their own words. lump in her vagina or has problems defecating or

Nurse practitioners can then ask specific questions passing urine.

about signs and symptoms. The areas covered when ■■ History of gynaecological procedures, such as a

taking a gynaecological history include: hysterectomy or oophrectomy, and the reasons

why these were performed.

Menstrual history How this is taken depends on the ■■ Screening for intimate-partner violence to

age of the women concerned. discover whether the symptoms are caused by

■■ For all women: the age of menarche, any history abuse or violence. Signs and symptoms can

of menstrual irregularity, heavy bleeding, include: dysmenorrhea, urinary tract infections,

irregularity or dysmenorrhoea, length of cycle changes in menstrual cycle, vaginal infections,

including the characteristics of bleeding and pelvic pain independent of menstrual bleeding

any other associated signs and symptoms and adnexitis, or inflammation of the ovaries or

(Matteson et al 2011). fallopian tubes (Mark et al 2008).

■■ For women of reproductive age and in

menopausal transition: the date of their last Symptoms

period as measured by the first day of bleeding When good gynaecological histories have been taken,

or spotting, the date of their previous period, histories of signs and symptoms should be obtained.

the length of their current cycle, the number of The most common gynaecological problems among

days of menses, the occurrence of postcoital patients attending EDs are vaginal discharge,

bleeding, the occurrence of premenstrual abnormal bleeding, pelvic pain and urinary

signs or symptoms (Carusi and Goldstein problems. Other potential complaints include sexual

2013). Irregularity in a menstrual cycle among dysfunction and infertility, but these are rare in

premenopausal women should prompt NPs to people who attend EDs.

consider that they are pregnant.

■■ For postmenopausal women: age of last menses; Vaginal discharge There are many causes of vaginal

history of hormone therapy; the occurrence discharge. These may or may not be related to

of postmenopausal bleeding, a risk factor for sexually transmitted infection (Box 1, page 35).

endometrial cancer (Bickley 2003). Most adult women have some vaginal discharge,

which is produced as part of a process that keeps

Obstetric history This includes pregnancies, the vagina healthy. Fluids secreted by the cervix and

miscarriages, terminations or ectopic pregnancies, vagina leave the vagina daily, along with sloughed

as well as attempts at assisted reproduction such as off epithelial cells, non-pathological bacteria and

in vitro fertilisation. mucus. The amount of discharge varies in response

■■ For each pregnancy: date of delivery, gestational to changes in circulating oestrogen levels (Robb-

age, mode of delivery, maternal complications Niholson 2009) but an increase in the usual amount

and fetal complications; delivery complications; of vaginal discharge may be due to vulvovaginal

neonatal problems and current health of the child candidiasis, bacterial vaginosis, trichomoniasis,

(Carusi and Goldstein 2013). or infection involving Chlamydia trachomatis or

■■ Sexual history: sexually transmitted diseases Neisseria gonorrhoeae (French et al 2004). It should

that can affect the gynaecological system be noted, however, that no infective cause is found

(Coverdale et al 2011). in up to 34 per cent of patients with an increase in

■■ Use of contraceptive pills without condoms, vaginal discharge (French et al 2004).

and the associated risk of sexually When taking a history from someone with vaginal

transmitted infection. discharge, it is important to establish timing, colour,

■■ Current signs and symptoms. consistency, smell and presence of itch, because

■■ History of pelvic, vaginal or vulva infections, the these details can help NPs distinguish between

most common sign and symptoms of which being infections (Spence and Melville 2007). For example,

vaginal discharge or itching (Bickley 2003). Chlamydia infection and gonorrhoea produce

EMERGENCY NURSE September 2013 | Volume 21 | Number 5 33

Downloaded from RCNi.com by ${individualUser.displayName} on Jan 31, 2016. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2016 RCNi Ltd. All rights reserved.

Art & science | advanced practice

purulent vaginal discharge (Spence and Melville there is rarely enough space or time available to

2007), while Trichomonas infection often results undertake them privately and thoroughly, which

in a frothy, yellowy-green, fishy smelling discharge means that women are likely to require second

(Summers 2011). examinations soon afterwards.

The competence of the individuals performing

Uterine bleeding There are many potential causes the examinations should be considered and, where

for abnormal uterine bleeding (Box 2) and the possible, patients should be referred to specialists

first to be considered, and excluded if necessary, who perform the examinations regularly rather

is pregnancy (Cirlli and Cipot 2012). If a patient than emergency care team members who perform

is pregnant with vaginal bleeding, she should be them infrequently. Pelvic examinations should be

referred to an obstetrician because a threat to the undertaken in the ED only when appropriate, for

viability of the pregnancy may be indicated and example to confirm a diagnosis of cervicitis.

specialist investigation may be required. If patients are likely to require admission, or if

Bleeding associated with a change in menstrual firm diagnoses are unlikely to be made, they should

cycle or that occurs after menopause is classed be referred to the most appropriate specialists,

as abnormal (Carusi and Goldstein 2013). Normal usually gynaecologists, for examination so that

menses last up to seven days with an average blood subtle abnormalities are not missed. Staff in EDs

loss of between 35 and 40ml. Menorrhagia, defined are called on to make these examinations more than

as blood loss of more than 80ml, is a common other non‑gynaecological staff, however, and should

health problem and occurs in about 10 per cent proficient at them (Close et al 2001).

of all women and 22 per cent of women aged over Before undertaking examinations, NPs should

35 (Jensen et al 2012). prepare all the equipment they need so that patients

Menopause is said to have occurred after are not left in embarrassing or compromising

12 months of amenorrhea and usually occurs positions while, for example, they or the patients’

between the ages of 40 and 58 (Dillaway and Burton chaperones leave to find equipment they have

2011). Postmenopausal bleeding therefore occurs at forgotten. The equipment needed to undertake

any stage after 12 months of amenorrhea. vaginal or pelvic examinations includes:

■■ An appropriate examination table, ideally

Pain Musculoskeletal, gynaecological, urological, with stirrups or with a means to elevate the

gastrointestinal or neurological conditions can patient’s buttocks.

all cause pain in the pelvic region (Apte et al ■■ A good light source to see clearly what is

2012). Gynaecological conditions account for up being examined.

to two thirds of cases of pelvic pain in women ■■ Specula in a range of sizes. There are no

(Apte et al 2012) and, of these, endometriosis guidelines about the size or make of speculum

accounts for half (Garry 2006). Associated that should be used with individual patients.

gastrointestinal or urinary signs and symptoms Wide specula cause the most discomfort but

point to other causes, including constipation, narrower ones can restrict visibility (Bates et al

irritable bowel disease, urinary tract infection, and 2011). Nurse practitioners should be familiar with

musculoskeletal or psychiatric causes (Damle and the different specula in their EDs and understand

Gomez-Lobo 2011). how each of them can suit their needs.

■■ Swabs to collect samples from the vagina.

Prolapse In describing pelvic organ, or vaginal, This equipment should be available even if the

prolapse women often report discomfort or patient undergoing examination has no history

pressure, a weakness in muscle or connective of discharge.

tissue, vaginal bulging or visibility of vaginal walls, ■■ Large cotton swabs to absorb vaginal discharge or

or urinary or bowel-related signs or symptoms blood, to allow a good view of the cervix.

(Pakbaz et al 2011). They may also report a need to ■■ Water soluble lubricant, gloves and material to

place a finger into the vagina to help them defecate drape the patient.

or pass urine (Carusi and Goldstein 2013). Up If the patient is pregnant or has recently given birth,

to 50 per cent of parous women may experience the due date of delivery, gestational age of the

a form of pelvic organ prolapse at some point fetus, mode of delivery and complications, maternal

(Maher et al 2013). and fetal complications, neonatal problems, and

health of the child should be recorded (Carusi and

Pelvic examination Goldstein 2013).

Pelvic examinations in EDs are controversial because Before undertaking examinations, NPs should

34 September 2013 | Volume 21 | Number 5 EMERGENCY NURSE

Downloaded from RCNi.com by ${individualUser.displayName} on Jan 31, 2016. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2016 RCNi Ltd. All rights reserved.

Box 1 Common causes of vaginal discharge be noted because they can help confirm diagnosis

(Talley and O’Connor 2006). If lesions are present,

Non-infective causes they should be palpated to determine if they are

■■ Physiological, such as an increase in normal painful and swabs taken for culture.

vaginal secretions.

■■ Cervical ectopy. Bartholin’s and paraurethral glands Bartholin’s

■■ Presence of foreign bodies such as retained tampons. glands are located in the labia minora, at the 4 and

■■ Vulval dermatitis. 8 o’clock positions, with the clitoris area being the

12 o’clock position. Their function is to secrete

Non-sexually transmitted infections mucus through the Bartholin’s ducts to lubricate

■■ Bacterial vaginosis. the vagina. Unless the ducts are obstructed or

■■ Candidal infections. there is infection, the glands are rarely palpable

(Mercado et al 2013).

Sexually transmitted infections The paraurethral, or Skene’s (Gittes 2002), glands

■■ Chlamydia. are glandular tissue proximal to the two ducts, the

■■ Gonorrhoea. openings of which can be seen next to the urethral

■■ Trichomonas. meatus. If the glands are enlarged or tender, an

(Spence and Melville 2007) attempt should be made to express exudates, which

indicate infection (Carusi and Goldstein 2013).

explain what they are going to examine and

everything they intend to do. Verbal consent for Speculum examination The speculum should be

examinations should be obtained before they inserted into the vagina with the aid of warm water

begin and patients should be told that, if they or water-based lubricant. Gentle downward pressure

are uncomfortable, the examinations will be with a finger inserted into the vagina can help with

stopped. Written consent is usually required only this process. The speculum is advanced to a depth

for examinations of patients under anaesthesia. of around 4cm, and the blades are opened to help

Patients should be told they can be accompanied identify the cervix. The blades should be opened

by chaperones and, if they choose to have them, enough to encircle the cervix before being locked in

examinations should not start until suitable place (Edelman et al 2007).

chaperones are present. Vaginal wall lesions, anomalies or atrophic

Usually, patients are asked to pass urine mucosa should be noted. If discharge is present,

before examinations because a full bladder causes the volume, colour, consistency and odour should

discomfort during bimanual examination and be noted, and swabs taken (Carusi and Goldstein

interferes with the palpation of structures. It also 2013). Lesions or discharge around the cervix

pulls the uterus superiorly, making localisation of should be recorded and swabs taken (Carusi and

the cervix difficult (Bates et al 2011). Goldstein 2013). If patients require pap smears,

Pelvic examinations include that of the external they should be taken before any other tests (Royal

genitalia, and of the Bartholin’s and paraurethral College of Nursing (RCN) 2013). Non-specialist ED

glands. They also include speculum examination of staff should not take pap smear samples, however,

the vagina walls and the cervix, bimanual examination because diagnoses may be wrong if they are

to palpate the ovaries and rectovaginal examination. taken incorrectly.

They should be undertaken after examinations of

Box 2 Common causes of uterine bleeding

other parts of the body have been undertaken, when

patients are more likely to be at ease. ■■ Pregnancy.

■■ Structural problems, such as atrioventricular

External genitalia When patients are comfortable, malformation, polyps, fibroids, endometriosis and

NPs should examine the external genitalia, including hyperplasia.

the mons pubis, labia, perineum, labia minora, ■■ Coagulopathies such as von Willebrand’s disease.

clitoris, urethral meatus and vaginal opening. ■■ Polycystic ovary syndrome.

Excoriations or the presence of itchy, small, red ■■ Intrauterine or oral contraceptives.

maculopapules in the mons pubis suggest pubic lice, ■■ Medications such as antiepileptics and

and the base of the pubic hairs should be examined antipsychotics.

to see if lice are present (Bickley 2003). Inflammation, ■■ Endometritis.

ulceration, discharge, swelling or nodules on the

(Cirlli and Cipot 2012)

labia, perineum or around the vagina opening should

EMERGENCY NURSE September 2013 | Volume 21 | Number 5 35

Downloaded from RCNi.com by ${individualUser.displayName} on Jan 31, 2016. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2016 RCNi Ltd. All rights reserved.

Art & science | advanced practice

After the cervix has been examined, the speculum consistency, uniformity, mobility and tenderness;

should be removed carefully, ensuring that neither also the fornices around the cervix are palpated

the vaginal walls nor cervix are trapped in the (Bickley 2003). Pain on movement of the cervix and

closing blades. As the speculum is removed, the adnexal tenderness suggest pelvic inflammatory

vagina is examined for foreign bodies, signs of disease (Bickley 2003).

infection or cysts (RCN 2013). To palpate the uterus, the hand on the abdomen

should press down midway between the umbilicus

Bimanual examination Bimanual examination and the symphysis pubis, and the fingers of the

has long been considered an essential part of other hand should elevate the cervix, until the

pelvic examination because it is suggested that uterus between can be grasped between both hands.

it provides accurate assessment of the uterus, The size and shape of the uterus vary according to

fallopian tubes and ovaries (Padilla et al 2005). reproductive status, with enlargement, for example,

Its use is controversial, however, especially for suggesting pregnancy, or malignant or benign

the detection of ovarian masses, with the use of tumours (Bickley 2003). The position of the uterus

transvaginal ultrasonography being the preferred can be described as:

method of examination for symptomatic women ■■ Axial, wherein its axis is the same as the

(Westhoff et al 2011). vaginal axis.

The procedure is carried out by inserting gloved, ■■ Inversion, wherein the entire uterus relative to

lubricated index and middle fingers into the vagina, the axis of the vagina is, for example, anteverted

while placing the other hand on the abdomen and or retroverted.

pressing towards the inserted fingers (RCN 2013). ■■ Inflexion, wherein the position of the uterine

As the fingers are inserted, the vaginal tone and fundus relative to the axis of the cervix is, for

wall support are assessed for protrusions, prolapse example, anteflexed or retroflexed (Carusi and

and foreign bodies. Goldstein 2013).

After palpating along the vagina walls, the cervix Finally, the adnexal areas are palpated to examine

is palpated, again with notice of its position, shape, the ovaries, which are usually mobile and tender,

References

Apte G, Nelson P, Brismee J et al (2012) Health Clinical Solutions. tinyurl.com/qfehgg8 and practice patterns. Southern Medical Journal. diagnostic testing more effectively. Journal

Chronic female pelvic pain: part 1. Clinical (Last accessed: July 17 2013.) 99, 3, 212-215. of Family Practice. 53, 10, 805-814.

pathoanatomy and examination of the

Close R, Sachs CJ, Dyne P (2001) Reliability Dillaway H, Burton J (2011) ÔNot done Garry D (2006) Diagnosis of endometriosis and

pelvic region. Pain Practice. 12, 2, 88-110.

of bimanual pelvic examinations performed yet?!Õ Women discuss the ‘end’ of pelvic pain. Fertility and Sterility. 86, 5, 1307-1309.

doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2011.00465.x

in emergency departments. Western Journal menopause. Women’s Studies. 40, 2, 149-176.

Gittes R (2002) Female prostatitis. Urology

Bates C, Carroll N, Potter J (2011) of Medicine. 175, 4, 240-244. doi: 10.1080/00497878.2011.537982

Clinics of North America. 29, 613-616.

The challenging pelvic examination. Journal

Coverdale J, Balon R, Roberts L (2011) Edelman A, Anerderson J, Lai S et al (2007)

of General Internal Medicine. 26, 6, 651-657. Huber J, Pukall C, Boyer S et al (2009)

Teaching sexual history-taking: a systematic Pelvic examination. New England Journal

doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1610-8 ‘Just relax’: physicians’ experiences with

review of educational programs. of Medicine, 356, e26-e28.

women who are difficult or impossible

Bickley L (2003) Bates’ Guide to Physical Academic Medicine. 86, 12, 1590-1595. doi: 10.1056/NEJMvcm061320

to examine gynecologically. Journal

Examination and History Taking. Eighth edition. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823ea41

Fiddes P, Scott A, Fletcher J et al (2003) of Sexual Medicine. 6, 3, 791-799.

Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia PA.

Damle L, Gomez-Lobo V (2011) Attitudes towards pelvic examination and doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01139.x

Bridge S (2011) A competency history: an Pelvic pain in adolescents. Journal of chaperones: a questionnaire survey of patients

Jensen J, Lefebvre P, Laliberte F et al (2012)

additional model of history taking. Australian Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. and providers. Contraception. 67, 4, 313-317.

Cost burden and treatment patterns associated

Family Physician. 20, 9, 735-739. 24, 3, 172-175. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2011.02.002 doi: 10.1016/S0010-7824(02)00540-1

with management of heavy menstrual bleeding.

Carusi D, Goldstein D (2013) The gynecologic Davisson L, Clark K, Powers R et al (2006) The French L, Horton J, Matousek M (2004) Journal of Women’s Health. 21, 5, 539-547.

history and pelvic examination. Wolters Kluwer rectovaginal examination: physician attitudes Abnormal vaginal discharge: using office doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.3147

36 September 2013 | Volume 21 | Number 5 EMERGENCY NURSE

Downloaded from RCNi.com by ${individualUser.displayName} on Jan 31, 2016. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2016 RCNi Ltd. All rights reserved.

and measure about 2 by 3cm (Carusi and Goldstein practitioners need the confidence and skill to put

2013). Most women will be diagnosed with benign patients at their ease so that they experience as

disease processes or no disease. It should be noted little trauma as possible. Cultural sensitivities must

that palpation of adnexal masses can be difficult be acknowledged and respected, and NPs should

for inexperienced examiners and, if diagnoses are ask patients if they object to undergoing pelvic

likely to be based on this procedure, referral to a examinations, and whether they would prefer a male

gynaecological specialist is prudent. Palpation of or female examiner.

ovaries in postmenopausal women is not a normal Before examining patients, comprehensive

practice (McDonald and Modesitt 2006). histories should be taken to ensure that physical

examinations are focused. Nurse practitioners need

Rectovaginal examination Rectovaginal examination to be confident also in asking questions because

is used to evaluate the posterior portion of the this gives patients the confidence to answer them

pelvis and the rectovaginal septum. The examination truthfully. Examinations must also be approached

may be uncomfortable for patients, however, confidently, so that patients are confident that they

because the index finger is inserted into the vagina are being treated professionally.

while the middle finger of the other hand is inserted This article focuses on the taking of gynaecological

into the rectum. This allows for palpation of the histories and examination of adult women. It does

posterior cul-de-sac and uterosacral ligaments. Its not cover the taking of sexual histories, or caring

use for the detection of cul-de-sac pathology is for adolescents or women with special needs. These

debatable (Davisson et al 2006) and, because of its two categories of patient often require a different Online archive

lax sensitivity or specificity for abnormal findings, approach to examination. Questions asked of women

For related information, visit

is rarely performed. with special needs may have to be simplified to

our online archive and search

ensure that they are understood. A discussion of their using the keywords

Conclusion needs has been omitted, therefore, to allow NPs to

Taking gynaecological histories and examining focus on the patients they are most likely to see and Conflict of interest

patients can be daunting for NPs and patients. Nurse to gain confidence in their management. None declared

Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K et al (2013) Surgical Mercado J, Brea I, Mendez B et al (2013) Pakbaz M, Rolfsman E, Mogren I et al (2011) Spence D, Melville C (2007) Vaginal discharge.

management of pelvic organ prolapse in women: Critical obstetric and gynecologic procedures in Vaginal prolapse: perceptions and healthcare- British Medical Journal. 335, 7630, 1147-1151.

review. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. the emergency department. Emergency Medical seeking behavior among women prior to doi: 10.1136/bmj.39378.633287.80

4. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004014.pub5 Clinics of North America. 31, 1, 207-236. gynaecological surgery. Acta Obsterticia et

Summers A (2011) Identifying non-viral

(Last accessed: July 17 2013.) Gynecologica Scandinavica. 90, 10, 1115-1120.

Mark H, Bitzker K, Klapp B et al (2008) gynaecological conditions. Emergency Nurse.

doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2012.09.005 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01225.x

Gynaecological symptoms associated with 18, 9, 26-30.

physical and sexual violence. Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Council (2012) Robb-Niholson R (2009) What can I do about

Talley N, O’Connor S (2006) Clinical

Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynecology. Chaperoning. tinyurl.com/dxpclp7 strep B vaginitis? Harvard Women’s Health

Examination: A Systematic Guide to Physical

29, 3, 164-172. doi: 10.1080/01674820701832770 (Last accessed: July 17 2013.) Watch. 16, 10, 8.

Diagnosis. Fifth edition. Churchill Livingstone,

Matteson K, Munro M, Fraser I (2011) The Padilla L, Radosevich D, Milad M (2005) Royal College of Nursing (2013) Genital Sydney NSW.

structured menstrual history: developing a Limitations of the pelvic examination Examination in Women: A Resource for Skills

Westhoff C, Jones H, Guiahi M (2011)

tool to facilitate diagnosis and aid in symptom for evaluation of the female pelvic Development and Assessment. RCN, London.

Do new guidelines and technology make

management. Seminars in Reproductive organs. International Journal of

Shawn T, Upshur R (2008) The medical the routine pelvic examination obsolete?

Medicine. 29, 5, 423-435. Gynecology and Obstetrics. 88, 1, 84-88.

chaperone: outdated anachronism or Journal of Women’s Health. 20, 1, 5-10.

doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.09.015

McDonald J, Modesitt S (2006) The incidental modern necessity? Southern Medical Journal. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2349

postmenopausal adnexal mass. Clinical 101, 1, 9-10.

Obstetrics and Gynecology. 49, 3, 506-516.

EMERGENCY NURSE September 2013 | Volume 21 | Number 5 37

Downloaded from RCNi.com by ${individualUser.displayName} on Jan 31, 2016. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2016 RCNi Ltd. All rights reserved.

You might also like

- Osce Basil.Document304 pagesOsce Basil.AsuganyadeviBala95% (19)

- 30 Main Nogier PointsDocument3 pages30 Main Nogier PointsCarissa Nichols100% (4)

- Hse Statistics Report Pp701 Hse f04 Rev.bDocument1 pageHse Statistics Report Pp701 Hse f04 Rev.bMohamed Mouner100% (1)

- Medip, IJRCOG-8374 ODocument6 pagesMedip, IJRCOG-8374 Oalaesa2007No ratings yet

- Guia Canadience Uso de Mallas VaginalesDocument13 pagesGuia Canadience Uso de Mallas VaginalesGiuliana Cuadros PeñalozaNo ratings yet

- What S New in Guidance - Urinary Incontinence and Pelvic Organ Prolapse NICE NG123 - TOG April 2024Document2 pagesWhat S New in Guidance - Urinary Incontinence and Pelvic Organ Prolapse NICE NG123 - TOG April 2024Myint Su MgNo ratings yet

- Evaluate The Effectiveness of Structured Teaching Program Regarding Menopausal Syndrome Among The Peri Menopausal Women in Bandarulanka, Amalapuram, Andhra PradeshDocument9 pagesEvaluate The Effectiveness of Structured Teaching Program Regarding Menopausal Syndrome Among The Peri Menopausal Women in Bandarulanka, Amalapuram, Andhra PradeshInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Initial Investigation and Managenement Benign Ovariam MassesDocument12 pagesInitial Investigation and Managenement Benign Ovariam MassesleslyNo ratings yet

- Journal Obgyne DR - ApDocument6 pagesJournal Obgyne DR - Apoktaviana54No ratings yet

- Guideline No. 437 - Diagnosis and Management of AdenomyosisDocument14 pagesGuideline No. 437 - Diagnosis and Management of Adenomyosisina.popescu89No ratings yet

- Assessment of The Qualıty of Lıfe in Women Wıth A Dıagnosıs of Urogenıtal ProlapseDocument8 pagesAssessment of The Qualıty of Lıfe in Women Wıth A Dıagnosıs of Urogenıtal ProlapseQuynh Giang Nguyen LeNo ratings yet

- Adult Urodynamics Guideline PDFDocument30 pagesAdult Urodynamics Guideline PDFVlad ValentinNo ratings yet

- AUB 2012 SSDSDDDDDDDDDocument7 pagesAUB 2012 SSDSDDDDDDDDPitra Mukhlis WardaniNo ratings yet

- Quantitative Measures of Self-Reported Data On Abortion Morbidity: A Case Study in Madhya Pradesh, IndiaDocument10 pagesQuantitative Measures of Self-Reported Data On Abortion Morbidity: A Case Study in Madhya Pradesh, IndiaHeather HennessyNo ratings yet

- Guideline No. 414: Management of Pregnancy of Unknown Location and Tubal and Nontubal Ectopic PregnanciesDocument18 pagesGuideline No. 414: Management of Pregnancy of Unknown Location and Tubal and Nontubal Ectopic PregnanciesAmel Zaouma100% (1)

- SAGES Guidelines For The Use of Laparoscopy During PregnancyDocument16 pagesSAGES Guidelines For The Use of Laparoscopy During Pregnancymaryzka rahmadianitaNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Urinary Incontinence in The 12-Month Postpartum Period and Related Risk Factors in TurkeyDocument8 pagesPrevalence of Urinary Incontinence in The 12-Month Postpartum Period and Related Risk Factors in TurkeyMoenaIsmailNo ratings yet

- Der Chi 2001Document19 pagesDer Chi 20013bood.3raqNo ratings yet

- Amsterdam Placental WorkshopDocument16 pagesAmsterdam Placental WorkshopCarlos Andrés Sánchez RuedaNo ratings yet

- 14 Vol. 11 Issue 11 Nov 2020 IJPSR RE 3646Document7 pages14 Vol. 11 Issue 11 Nov 2020 IJPSR RE 3646Ehwanul HandikaNo ratings yet

- Awareness of Patients With Symptomatic Gallstones Regarding Their Own DiseaseDocument3 pagesAwareness of Patients With Symptomatic Gallstones Regarding Their Own DiseaseHelenCandyNo ratings yet

- The Gynecologic History and Pelvic Examination Up To Date 2016Document14 pagesThe Gynecologic History and Pelvic Examination Up To Date 2016Mateo GlNo ratings yet

- Transvaginal Ultrasonography and Female InfertilityDocument76 pagesTransvaginal Ultrasonography and Female InfertilityDavid MayoNo ratings yet

- The Prevalence of Congenital Uterine Anomalies in Unselected and High-Risk Populations A Systematic ReviewDocument11 pagesThe Prevalence of Congenital Uterine Anomalies in Unselected and High-Risk Populations A Systematic ReviewMoustafa KamelNo ratings yet

- Evidence-Based Management of Endometrioma: Tarek A Gelbaya, Luciano G NardoDocument10 pagesEvidence-Based Management of Endometrioma: Tarek A Gelbaya, Luciano G NardofebrianoramadhanaNo ratings yet

- Mehu108 U4 T4 Anomalias Congénitas3Document34 pagesMehu108 U4 T4 Anomalias Congénitas3Michael Rodrigues HaroNo ratings yet

- Spectrum of Symptoms in Women Diagnosed With Endometriosis During Adolescence Vs AdulthoodDocument11 pagesSpectrum of Symptoms in Women Diagnosed With Endometriosis During Adolescence Vs AdulthoodnicloverNo ratings yet

- Predisposing Factors and Demographic Analysis in Inguinal HerniaDocument4 pagesPredisposing Factors and Demographic Analysis in Inguinal HerniaKarl PinedaNo ratings yet

- ICSIUGA Joint Report On The Assessment of Sexual Health of Woman 2018Document21 pagesICSIUGA Joint Report On The Assessment of Sexual Health of Woman 2018sivakumarNo ratings yet

- Gynae ClinDocument10 pagesGynae ClinUmut KNo ratings yet

- FIGO Classification System PALM-COEIN For Causes oDocument12 pagesFIGO Classification System PALM-COEIN For Causes oEdwin SondakhNo ratings yet

- crowley2009 - вагинизмDocument6 pagescrowley2009 - вагинизмxobekon323No ratings yet

- Sultan Et Al-2017-Neurourology and UrodynamicsDocument25 pagesSultan Et Al-2017-Neurourology and UrodynamicsMikhail NurhariNo ratings yet

- Incontinencia FecalDocument11 pagesIncontinencia FecalDiego MarzaroliNo ratings yet

- Abnormal Uterine Bleeding in Perimenopausal WomenDocument15 pagesAbnormal Uterine Bleeding in Perimenopausal WomenOrchid LandNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Neck MassDocument17 pagesEvaluation of Neck MassMuammar Aqib MuftiNo ratings yet

- LANCET - 1 - Time For A Balanced Conversation About Menopause (Hickney Et Al., 2024)Document11 pagesLANCET - 1 - Time For A Balanced Conversation About Menopause (Hickney Et Al., 2024)Rebeca PeñuelaNo ratings yet

- A Prática de Exercícios Físicos É Um Fator Modificavel Da Incontinencia Urinaria de Urgencia em Mulheres IdosasDocument17 pagesA Prática de Exercícios Físicos É Um Fator Modificavel Da Incontinencia Urinaria de Urgencia em Mulheres Idosasbacharelado2010No ratings yet

- Urinary Incontinence With StrokeDocument8 pagesUrinary Incontinence With StrokeJamaicaNo ratings yet

- Aub 1Document3 pagesAub 1Nadiah Baharum ShahNo ratings yet

- Art 3A10.1007 2Fs00192 017 3304 9Document6 pagesArt 3A10.1007 2Fs00192 017 3304 9Khaleed KandaraNo ratings yet

- History Taking and Clinical Examination For Ong Patients 2Document19 pagesHistory Taking and Clinical Examination For Ong Patients 2Shangai GuptaNo ratings yet

- Yeung TeenagersDocument5 pagesYeung TeenagersAnonymous YyLSRdNo ratings yet

- Hope, Burden or Risk FPDocument24 pagesHope, Burden or Risk FPDolores GalloNo ratings yet

- Ultrasound Detected Ovarian Cysts For Nuh Gynaecology TeamsDocument11 pagesUltrasound Detected Ovarian Cysts For Nuh Gynaecology TeamsDirga Rasyidin LNo ratings yet

- A Suggested Approach For Implementing CONSORT Guidelines Specific To Obstetric ResearchDocument5 pagesA Suggested Approach For Implementing CONSORT Guidelines Specific To Obstetric ResearchminhhaiNo ratings yet

- Vaginal Discharge and Associated Views Among Women Attending Gynaecological OPDDocument2 pagesVaginal Discharge and Associated Views Among Women Attending Gynaecological OPDdkhatri01No ratings yet

- Guideline No. 402 Diagnosis and Management of Placenta PreviaDocument13 pagesGuideline No. 402 Diagnosis and Management of Placenta PreviaAndrés Gaviria C100% (1)

- Guideline No. 422b: Menopause and Genitourinary Health: Sogc Clinical Practice GuidelineDocument8 pagesGuideline No. 422b: Menopause and Genitourinary Health: Sogc Clinical Practice GuidelineGabino Alexander Liviac CrisostomoNo ratings yet

- YOUNG 2017 Clinicians' Perceptions of Women's ExperiencesDocument6 pagesYOUNG 2017 Clinicians' Perceptions of Women's ExperiencesCristiane HermesNo ratings yet

- JejeuryDocument5 pagesJejeuryRizka YusraNo ratings yet

- Hum. Reprod.-2005-Kennedy-2698-704Document7 pagesHum. Reprod.-2005-Kennedy-2698-704MariaJimenaPalaciosNo ratings yet

- Literature Review EpisiotomyDocument6 pagesLiterature Review Episiotomyafmztopfhgveie100% (1)

- Hiperplasia EndometrialDocument12 pagesHiperplasia EndometrialJulián LópezNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Urinary IncontinenceDocument6 pagesLiterature Review Urinary Incontinenceea68afje100% (1)

- Causes of Amenorrhea in Korea: Experience of A Single Large CenterDocument4 pagesCauses of Amenorrhea in Korea: Experience of A Single Large CenterNadya MagfiraNo ratings yet

- Knowledge and Practice of Cervical Cancer Screening Amongst Nurses in Ahmadu Bello University Teaching Hospital ZariaDocument9 pagesKnowledge and Practice of Cervical Cancer Screening Amongst Nurses in Ahmadu Bello University Teaching Hospital ZariafxbukenyaNo ratings yet

- Menstrual Disorders Among Zagazig University Students, Zagazig, EgyptDocument6 pagesMenstrual Disorders Among Zagazig University Students, Zagazig, EgyptErsi Dwi Utami SiregarNo ratings yet

- Norton 2014Document5 pagesNorton 2014Gladys SusantyNo ratings yet

- Practic Buletin Early Pregnancy Loss PDFDocument10 pagesPractic Buletin Early Pregnancy Loss PDFsiantan ngebutNo ratings yet

- Family History As A Risk Factor For Pelvic Organ Prolapse: Original ArticleDocument7 pagesFamily History As A Risk Factor For Pelvic Organ Prolapse: Original ArticlepakemainmainNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Problems in Tumors of Female Genital Tract: Selected TopicsFrom EverandDiagnostic Problems in Tumors of Female Genital Tract: Selected TopicsNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Problems in Tumors of Gastrointestinal Tract: Selected TopicsFrom EverandDiagnostic Problems in Tumors of Gastrointestinal Tract: Selected TopicsNo ratings yet

- 18-400 AppbDocument21 pages18-400 Appbfaria ejazNo ratings yet

- Marine Accident Investigation Report: October 25, 2018Document34 pagesMarine Accident Investigation Report: October 25, 2018faria ejazNo ratings yet

- Merchant Shipping Act 1985 Merchant Shipping (Modu Code) Regulations 1997Document7 pagesMerchant Shipping Act 1985 Merchant Shipping (Modu Code) Regulations 1997faria ejazNo ratings yet

- Menstrual DysfuntionDocument49 pagesMenstrual Dysfuntionfaria ejazNo ratings yet

- The Continuous Professional Development of School Principals: Current Practices in PakistanDocument23 pagesThe Continuous Professional Development of School Principals: Current Practices in Pakistanfaria ejazNo ratings yet

- ARCCPDToolkitApril2014 000Document60 pagesARCCPDToolkitApril2014 000faria ejazNo ratings yet

- The Family Client: Home VisitDocument38 pagesThe Family Client: Home Visitfaria ejazNo ratings yet

- Ch12-Ec2e2n Boochk-201511-Guidebook Goodpractice 4pstctDocument16 pagesCh12-Ec2e2n Boochk-201511-Guidebook Goodpractice 4pstctfaria ejazNo ratings yet

- HAJRA QuestDocument6 pagesHAJRA Questfaria ejazNo ratings yet

- Reproductive Health and Responsible Sexuality: Mindanao Young Women Leaders CongressDocument25 pagesReproductive Health and Responsible Sexuality: Mindanao Young Women Leaders Congressfaria ejazNo ratings yet

- Consulting The Oracle: Ten Lessons From Using The Delphi Technique in Nursing ResearchDocument8 pagesConsulting The Oracle: Ten Lessons From Using The Delphi Technique in Nursing Researchfaria ejazNo ratings yet

- Views of Midwives and Gynecologists On Legal Abortion - A Population-Based StudyDocument7 pagesViews of Midwives and Gynecologists On Legal Abortion - A Population-Based Studyfaria ejazNo ratings yet

- Coetzee2013 PDFDocument12 pagesCoetzee2013 PDFfaria ejazNo ratings yet

- IIE Transactions On Healthcare Systems EngineeringDocument14 pagesIIE Transactions On Healthcare Systems Engineeringfaria ejazNo ratings yet

- Congenital Heart DefectsDocument73 pagesCongenital Heart DefectsStaen KisNo ratings yet

- Future Perfect and Cont TestDocument2 pagesFuture Perfect and Cont TestEdit GöröcsNo ratings yet

- Article in Press: Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Medicine, and PathologyDocument7 pagesArticle in Press: Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Medicine, and PathologyNizajaulNo ratings yet

- CH 15Document8 pagesCH 15naguguNo ratings yet

- Application of Reflection of Sound WavesDocument17 pagesApplication of Reflection of Sound Wavesalias_acaiNo ratings yet

- Anatomy, Autonomic Nervous System - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocument10 pagesAnatomy, Autonomic Nervous System - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelfwood landerNo ratings yet

- Assignment # 01 Pharmacology: Presented By: Zoha Abid Submitted To: DR MalihaDocument10 pagesAssignment # 01 Pharmacology: Presented By: Zoha Abid Submitted To: DR MalihaLaraibNo ratings yet

- Micu MedsDocument3 pagesMicu MedsanreilegardeNo ratings yet

- Science NotesDocument2 pagesScience NotesSofia JeonNo ratings yet

- Yoga Therapy ConceptDocument32 pagesYoga Therapy ConceptKirthika R100% (2)

- Case Study and Care Plan FinalDocument14 pagesCase Study and Care Plan Finalapi-238869728No ratings yet

- Birth AsphyxiaDocument20 pagesBirth Asphyxiainne_fNo ratings yet

- Nail Diseases and DisordersDocument45 pagesNail Diseases and DisordersMariel Balmes HernandezNo ratings yet

- AcalyphineDocument1 pageAcalyphinearidwanulohNo ratings yet

- Mind Speak To Us Interactive Lesson Plan 3Document15 pagesMind Speak To Us Interactive Lesson Plan 3PrakashNo ratings yet

- DR - Tateishi's Cancer Healing Formula: What This Remedy May DoDocument8 pagesDR - Tateishi's Cancer Healing Formula: What This Remedy May DoCheri HoNo ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument6 pagesCase Studyapi-276551783No ratings yet

- She Jan 2010Document122 pagesShe Jan 2010shemagononlyNo ratings yet

- Handbookof Autismand AnxietyDocument2 pagesHandbookof Autismand AnxietyJelena JokićNo ratings yet

- Cerebral PalsyDocument24 pagesCerebral PalsyBam ValleserNo ratings yet

- 01 Congenital Diseases of The External and Middle Ear-1Document39 pages01 Congenital Diseases of The External and Middle Ear-1cabdinuux32No ratings yet

- NCM 116 Lab Activity 2 NCP 1 Git PabrnmanDocument6 pagesNCM 116 Lab Activity 2 NCP 1 Git Pabrnmanjericho dinglasanNo ratings yet

- Regis Mani AAOMPT Poster 2008Document1 pageRegis Mani AAOMPT Poster 2008smokey73No ratings yet

- (Chinyanja) Chewa - English Dictionaryvermeullen PDFDocument72 pages(Chinyanja) Chewa - English Dictionaryvermeullen PDFEugênio C. Brito100% (1)

- SURGERY Revalida Review 2019Document78 pagesSURGERY Revalida Review 2019anonymousNo ratings yet

- Drug Study: Valerie V. Villanueva BN3-CDocument1 pageDrug Study: Valerie V. Villanueva BN3-CValerie VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Geria ReviewerDocument7 pagesGeria ReviewerCarl John ManaloNo ratings yet