Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 202.56.183.21 On Thu, 22 Oct 2020 07:03:29 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 202.56.183.21 On Thu, 22 Oct 2020 07:03:29 UTC

Uploaded by

Mukhtar NusratOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 202.56.183.21 On Thu, 22 Oct 2020 07:03:29 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 202.56.183.21 On Thu, 22 Oct 2020 07:03:29 UTC

Uploaded by

Mukhtar NusratCopyright:

Available Formats

The Effect of Leadership Style on Performance Improvement on a Manufacturing Task

Author(s): Christine M. Shea

Source: The Journal of Business , Vol. 72, No. 3 (July 1999), pp. 407-422

Published by: The University of Chicago Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/209620

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access

to The Journal of Business

This content downloaded from

202.56.183.21 on Thu, 22 Oct 2020 07:03:29 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Christine M. Shea

University of New Hampshire

The Effect of Leadership Style

on Performance Improvement

on a Manufacturing Task

In spite of the considerable amount of empirical A three-factor, re-

work that has been conducted on leadership, peated-measures exper-

there has been no research published to date that iment tested the effect

of leadership style

has used an experimental methodology to investi- (charismatic, structur-

gate the effect of leadership style on followers’ ing, and considerate)

performance improvement on a manufacturing on performance im-

task over time. In view of the recent attention provement on a manu-

given to continuous improvement as a means of facturing task over

four trials. Findings

achieving improved competitiveness, it would be from a repeated-mea-

useful to explore the effect of leadership style on sures multivariate anal-

the improvement of follower performance over ysis of variance indi-

time. This article reports the results of a study cated that individuals

that investigates the effect of leadership style on exposed to considerate

leadership had superior

the qualitative and quantitative performance of a initial performance but

manufacturing task over a series of four trials. that this difference

Bandura’s (1986) social cognitive theory is used faded over time. Fur-

as a framework to develop a model that might ther analysis indicated

explain the psychological mechanism whereby that self-efficacy fully

mediated the relation-

leadership produces its effect on followers. ship between leader-

A growing amount of empirical evidence ship style and perfor-

points to the power of Bandura’s (1986) social mance.

cognitive theory in explaining behavior in orga-

nizations (Frayne and Latham 1987; Gist 1987;

Gist, Schwoerer, and Rosen 1989; Latham and

Frayne 1989; Wood and Bandura 1989; Bandura

and Jourden 1991; Saks 1995). According to

Bandura (1986, p. 12), ‘‘People are neither au-

tonomous agents nor mechanical conveyors of

animating environmental factors.’’ Instead, hu-

man behavior is best understood when viewed as

a reciprocal system of causality where personal

characteristics, environmental factors, and be-

( Journal of Business, 1999, vol. 72, no. 3)

1999 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved.

0021-9398/99/7203-0005$02.50

407

This content downloaded from

202.56.183.21 on Thu, 22 Oct 2020 07:03:29 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

408 Journal of Business

havior operate through cognitive self-regulatory mechanisms as inter-

acting determinants of each other. The self-regulatory mechanism of

self-efficacy, or the individual’s belief that he or she can accomplish

a task, has been found to be affected by external factors such as training

and to be linked with work outcomes such as employee attendance

(Frayne and Latham 1987; Latham and Frayne 1989) and management

decision making (Bandura and Jourden 1991).

Among other sources of self-efficacy, Bandura (1986) advances the

notion that employees can be persuaded that they possess the ability

to accomplish tasks. According to Bandura, managers as well as super-

visors differ in their ability to persuade followers that they possess the

ability to accomplish tasks. This difference in the persuasive ability of

managers is often referred to as leadership ability or style. Hence, the

leadership style that a manager possesses is expected to affect the self-

efficacy of the manager’s followers and, therefore, the performance of

those followers.

In this study, charismatic leadership is compared with both structur-

ing and considerate leadership styles. The structuring leadership style

is one that focuses on the task at hand. It emphasizes such behaviors

as maintaining standards and meeting deadlines. Considerate leadership

involves exhibiting concern for the welfare of the other members of

the group by expressing appreciation for good work, stressing the im-

portance of job satisfaction, maintaining and strengthening the self-

esteem of subordinates by treating them as equals, and making special

efforts to help subordinates feel at ease (Bass 1990). Leaders who dis-

play charismatic leadership behaviors have been described as providing

followers with clear visions of the future, expressing high expectations

for follower performance, and displaying confidence in their followers’

ability to accomplish challenging tasks (House 1988).

Leadership research has consistently found a strong positive relation-

ship between charismatic leadership behaviors and follower perfor-

mance (House 1988; Bass 1990). Specifically, by articulating a compel-

ling vision of the future, communicating high expectations with respect

to followers’ performance, and displaying confidence in followers’

ability to meet these expectations, charismatic leaders have been found

to positively influence follower performance. These findings have been

supported in a variety of settings and using various research methodolo-

gies including laboratory experiments (e.g., Howell and Frost 1989;

Kirkpatrick and Locke 1996), field research (e.g., Smith 1982; Avolio,

Waldman, and Einstein 1988; Hater and Bass 1988; Howell and Avolio

1993), and archival studies (e.g., House, Spangler, and Woycke 1991).

Howell and Frost (1989), for example, found that individuals working

under an actor trained to display charismatic leadership behaviors had

higher qualitative and quantitative task performance, higher task satis-

This content downloaded from

202.56.183.21 on Thu, 22 Oct 2020 07:03:29 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Leadership Style 409

faction, and lower role conflict and ambiguity in comparison to individ-

uals working under considerate leaders; they also had higher quantita-

tive task performance, greater task satisfaction, and less role conflict

than individuals working under structuring leaders. More recently, in

an experiment using 282 undergraduates carrying out a simulated pro-

duction assignment, Kirkpatrick and Locke (1996) found a positive re-

lationship between charismatic behaviors and performance, task satis-

faction, and attitude toward the leader. Both Howell and Frost’s and

Kirkpatrick’s studies found that individuals working under charis-

matic leaders reported that the task was more interesting, engaging,

and satisfying than individuals working under noncharismatic leaders;

this was so in spite of the fact that all individuals performed the identi-

cal task.

The above findings have been supported by the findings of studies

conducted in the field. For example, in a study of 30 charismatic and

30 noncharismatic leaders from a wide variety of organizations, Smith

(1982) found that charismatic leaders could be distinguished from non-

charismatic leaders based on their followers’ higher performances and

higher levels of self-assurance. Based on these reports of higher self-

assurance for followers of charismatic leaders, Smith postulated that

charismatic leaders may produce their effects on followers by enhanc-

ing their self-efficacy beliefs.

While the above empirical evidence supports the relationship be-

tween charismatic leadership behaviors and follower performance, the

effect of those behaviors on follower performance over time and the

role of self-efficacy as a mediator of the relationship between leader-

ship style and performance remain largely unexplored empirically. For

this reason, I draw on Shamir, House, and Arthur (1993) and Bandura

(1997) for a theoretical explanation of the motivational effect of charis-

matic leadership behaviors and how they might enhance follower self-

efficacy and lead to greater sustained effort and performance over time.

According to Bandura (1997, p. 101), ‘‘People who are persuaded ver-

bally that they possess the capabilities to master given tasks are likely

to mobilize greater effort and sustain it than if they harbor self-doubts

and dwell on personal deficiencies when difficulties arise.’’ Drawing on

Bandura (1986), Shamir et al. (1993) propose that charismatic leaders’

expression of high expectations for follower performance and their

ability to persuade followers that they can meet those expectations

motivate followers to produce and sustain greater effort via the medi-

ation of self-efficacy. Further, they propose that, by articulating a

compelling vision, charismatic leaders produce in followers a level of

personal commitment whose behavioral manifestations produce a self-

reinforcing cycle that sustains itself over time. This motivational influ-

ence of charismatic leadership behaviors produces a positive deviation-

This content downloaded from

202.56.183.21 on Thu, 22 Oct 2020 07:03:29 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

410 Journal of Business

amplifying loop or performance improvement spiral (Lindsley, Brass,

and Thomas 1995). Thus, while empirical evidence has demonstrated

the link between charismatic leadership and performance, theoretical

work points both to the sustainability of follower effort and perfor-

mance over time and to the mediating role of self-efficacy.

The above empirical evidence and theoretical arguments lead to the

following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1. There will be a significant effect of leadership style

on individual task performance over time such that individuals exposed

to charismatic leaders achieve higher task performance than those ex-

posed to structuring or considerate leadership.

Hypothesis 2. The effect of leadership style on individual perfor-

mance will be mediated by individuals’ self-efficacy beliefs.

I. Methodology

An experiment was designed to test the effect of leadership style and

self-efficacy on individual performance improvement over four trials

of a manufacturing task. This section describes the sample, the experi-

mental task, and the leadership manipulations.

A. Sample

The voluntary participation of sixty-five undergraduate operations man-

agement students (52 males, 13 females) was obtained in exchange

for the cancellation of one of their classes. The students ranged in age

from 20 to 29 and were randomly assigned to one of three leadership

conditions. The random assignment procedure controlled for variations

in the students’ ability to perform the experimental task.

The selection of undergraduate students as the sample for the present

study constituted a compromise between internal and external validity.

Because of their homogeneity and lack of experience in carrying out

the type of work required by the experimental task, I hoped that the

use of undergraduate students would ensure control over extraneous

sources of variation in performance.

B. Experimental Task

The experimental task involved the assembly of a variation on the

design of a real electrical wiring harness used by a large U.S. aero-

space organization. The harness consists of wires that are cut to speci-

fied lengths and stripped of insulation at both ends (using tooling bor-

rowed from aerospace components manufacturers) and pinned and

dressed into connectors so that the harness can be plugged into a test

fixture for later testing. The harness design was altered to achieve a

level of difficulty such that only 10% (or fewer) of the participants

would be able to complete the first harness attempted, while 90% (or

This content downloaded from

202.56.183.21 on Thu, 22 Oct 2020 07:03:29 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Leadership Style 411

more) of the participants would be able to complete the fourth harness

attempted. This was done to maximize the probability of participants

demonstrating improvement over time.

C. Leadership Manipulation

Scripts were written to demonstrate and professional actors were hired

and trained to portray charismatic, structuring, and considerate leader-

ship styles. All three actors were required to enact each of the three

leadership styles. The leadership style manipulations were based on

Howell (1986). The operationalizations of the three leadership styles

are shown in the appendix.

The three professional actors were recruited and hired based on their

physical similarities and on their ability to play the role of leader in a

manner that would be convincing to undergraduate business students.

A training program was developed that involved a series of readings

and videotapes aimed at conveying an understanding of the different

leadership styles. The actors were each required to learn three scripts—

reflecting charismatic, considerate, and structuring styles—and to re-

hearse the three roles in front of a video camera until I thought the

performances were acceptable.

To verify that the three actors were accurately portraying the differ-

ent leadership styles and were highly similar in these portrayals, 411

student judges, ignorant of the study’s purpose, rated videotapes of

each actor enacting the three styles. The judges completed a 37-item

leadership style questionnaire that measured the extent to which they

perceived the individual on the videotape to be displaying charismatic,

considerate, or structuring behaviors. Scale reliabilities were acceptable

with alphas exceeding .7 in all cases (Nunnally 1978). The coefficients

were .79 for the charismatic items, .86 for the structuring items, and

.92 for the considerate items. For the experimental manipulation to be

perceived as intended, a test of differences among the actors in their

portrayal of the same leadership style should be nonsignificant, while

a test of differences among the different leadership styles as portrayed

by the actors should be significant.

To test for similarities among the actors in their portrayal of the

leadership styles, Hotelling’s T 2 tests were computed for each actor on

the leadership style manipulation checks. None of the tests reached

statistical significance at the .05 level, indicating that the actors were

very similar in their portrayal of each of the three styles.

To test for differences between the three leadership styles, a series

of Hotelling’s T 2 tests were computed. The results revealed highly sig-

nificant statistical differences at the p ⬍ .0001 level between the struc-

turing, considerate, and charismatic styles on the leadership style ma-

nipulation checks. This suggests that there were clear differences in

the judges’ perceptions of the three leadership styles.

This content downloaded from

202.56.183.21 on Thu, 22 Oct 2020 07:03:29 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

412 Journal of Business

D. Procedure

A cover story was devised such that participants believed that they

were working with a real firm and manufacturing a subassembly that

was to be used in a real product. The stated purpose of the study varied

depending on the leadership style being portrayed. For example, partic-

ipants exposed to charismatic leadership were told that they were an

integral part of an effort aimed at determining the factors that affect

product quality in the aerospace industry. Participants in the consider-

ate and structuring conditions were not provided with such a meaning-

ful purpose for the exercise. The participants were required to work

through a series of exercises involving both questionnaires and the as-

sembly of four wiring harnesses. The exercises were arranged in the

following order:

1. Leadership intervention (The leader enters the room and introduces

himself as being a district manager for a distributor of cables and

supplies for the aerospace and electronics industries. He introduces

the task and shows an instructional video to the participants.)

2. Viewing of instructional video

3. Questionnaire no. 1: Pretest measures of self-efficacy

4. Assembly of first wiring harness

5. Leadership intervention (The leader provides some background on

the project and explains the purpose of the exercise using the script

that has been prepared to reflect the particular leadership style he

is portraying.)

6. Questionnaire no. 2: Self-efficacy scales

7. Assembly of second wiring harness

8. Questionnaire no. 3: Self-efficacy scales

9. Assembly of third wiring harness

10. Questionnaire no. 4: Self-efficacy scales

11. Assembly of fourth wiring harness

12. Questionnaire no. 5: Manipulation check and demographics

Throughout the exercise, the leaders were instructed to maintain the

nonverbal behaviors and paralinguistic cues consistent with the leader-

ship role that they were portraying.

II. Measures

A. Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy is a task-specific construct that measures the extent to

which individuals believe that they can achieve increasingly difficult

This content downloaded from

202.56.183.21 on Thu, 22 Oct 2020 07:03:29 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Leadership Style 413

levels of performance with respect to a specific task. Two measures of

self-efficacy were developed based on previous work by Bandura and

his colleagues (Bandura, Adams, and Beyer 1977; Bandura, Adams,

Hardy, and Howells 1980; Bandura and Jourden 1991), Locke, Freder-

ick, Lee, and Bobko (1984) and Gist (1987): a measure of self-efficacy

with respect to quantitative performance and a measure of self-efficacy

with respect to qualitative performance. Participants indicated whether

or not they believed that they could execute the behaviors required to

achieve 10 increasingly difficult levels of quantity and quality. They

also rated their level of confidence in each of those beliefs on a 10-point

scale. Overall self-efficacy was calculated by summing the product of

the confidence scores for those levels of quantity and quality for

which they responded ‘‘yes’’ when asked to indicate whether they

believed that they could achieve the level of performance indicated.

B. Task Performance

Task performance was also divided into two categories: quality and

quantity. Performance quality was assessed by an inspection carried

out by a professional quality control inspector whose services were

retained for that purpose. For each harness, the inspector filled out an

inspection sheet that contained seven items. These items were devel-

oped based on the relevant dimensions of quality as developed by Gar-

vin (1984). Four items captured the extent to which the assembled wir-

ing harnesses ‘‘conformed’’ to the specification (i.e., lengths and solder

flow acceptability). Two items measured the extent to which the wiring

harnesses ‘‘performed’’ according to specification; that is, the wiring

harnesses were plugged into test boxes designed and manufactured for

that purpose. The number of lights activated was counted, and points

were assigned depending on the extent to which performance met spec-

ifications. In addition, a current leakage test was carried out by sending

current through the wiring harnesses and measuring leakage to the

shield to detect possible damage to the wires during assembly. An over-

all quality score was computed based on points assigned on these items.

The maximum possible score was 35 points.

The manufacturing process consisted of a total of 27 steps, and par-

ticipants were given a maximum of 15 minutes to manufacture each

harness. Performance quantity was computed by dividing the actual

time taken by the participants to do the steps completed into the total

standard time associated with those steps. Thus, if a participant com-

pleted a harness in exactly 15 minutes, performance quantity would

equal 15 divided by 15, or 1. If a participant completed the steps associ-

ated with half the harness, performance quantity would be 7.5/15 or

.5. Finally, if a participant completed the entire harness in half the time

allotted, performance quantity would be 15/7.5, or 2.

This content downloaded from

202.56.183.21 on Thu, 22 Oct 2020 07:03:29 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

414 Journal of Business

III. Results

A. Manipulation Check

The experimental leadership manipulation was verified using the same

37-item leadership questionnaire that was used in the pretest. As in the

pretest, the questionnaire was administered at the end of the exercise.

Scale reliabilities were again acceptable with alpha coefficients of .81,

.81, and .86, respectively, for the vision, expectations and confidence

factors of the charismatic scale (the overall scale reliability ⫽ .90); .77

for the structuring items; and .93 for the considerate items. As in the

pretest, for the experimental manipulation to be perceived as intended,

a test of differences among the actors in their portrayal of the same

leadership style should be nonsignificant, while a test of differences

among the different leadership styles as portrayed by the actors should

be significant.

To evaluate the similarity of the three actors’ portrayal of the three

leadership styles in the study itself, Hotelling’s T 2 tests were computed

for each actor on the leadership style manipulation checks. The results

revealed that none of the tests were statistically significant at the .05

level, suggesting that the actors were very similar in their portrayal of

the three leadership styles.

To test for significant differences between the three leadership styles,

a series of Hotelling’s T 2 tests were computed. The results revealed

highly significant statistical differences at the p ⬍ .0001 level between

the structuring, considerate, and charismatic styles on the leadership

style manipulation checks. This suggests that there were clear differ-

ences in the participants’ perceptions of the three leadership styles.

B. Tests of Hypotheses

The cell means and standard deviations for the performance and self-

efficacy measures are presented in table 1. Repeated-measures multi-

variate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was used to test the hypothesis

of a significant effect of leadership style on task performance over time

(hypothesis 1). The results are summarized in table 2. The overall test

of the effect of leadership style on performance over a series of four

trials yielded a statistically significant effect at the p ⬍ .05 level for

both quantitative and qualitative performance (see table 2). As shown in

the table, leadership style explained 8% of the variance in performance

quantity and 9% of the variance in performance quality over time.

While the hypothesis stipulated that individuals exposed to charis-

matic leaders would achieve higher task performance than those ex-

posed to either structuring or considerate leaders, the results were not so

clear in supporting this. Examination of the dependent variable means

indicates that individuals exposed to structuring leaders did have con-

sistently lower performance quantity and quality over time as compared

This content downloaded from

202.56.183.21 on Thu, 22 Oct 2020 07:03:29 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Leadership Style 415

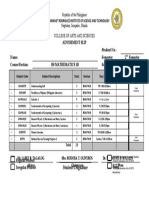

TABLE 1 Cell Means and Standard Deviations for the Dependent Measures

by Leadership Style

Charismatic Structuring Considerate

Style Style Style

Dependent Measures Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD

Performance quantity:

Trial 1 .64 .14 .63 .20 .76 .22

Trial 2 .91 .25 .79 .30 1.08 .35

Trial 3 1.15 .35 1.02 .42 1.28 .35

Trial 4 1.29 .34 1.26 .46 1.41 .44

Performance quality:

Trial 1 9.59 6.93 7.95 5.12 14.05 9.24

Trial 2 17.00 7.86 11.14 8.33 19.36 11.28

Trial 3 20.18 9.61 16.09 9.00 21.86 9.68

Trial 4 22.32 8.71 18.95 9.88 22.27 11.74

Quantity self-efficacy:

Trial 1 2.35 1.53 2.42 1.45 3.55 1.37

Trial 2 2.46 1.72 2.47 1.73 3.44 1.72

Trial 3 3.80 1.75 3.37 1.90 4.34 1.62

Trial 4 4.76 1.01 4.09 1.95 4.74 1.40

Quality self-efficacy:

Trial 1 1.95 1.35 2.54 1.34 3.28 1.37

Trial 2 2.07 1.41 2.09 1.36 3.16 1.78

Trial 3 3.15 1.48 2.99 1.79 3.71 1.77

Trial 4 4.01 1.30 3.27 1.93 4.02 1.61

to individuals exposed to either considerate or charismatic leaders.

However, individuals exposed to considerate leaders outperformed

those in the charismatic leadership condition when performance quan-

tity was considered. With respect to performance quality, while individ-

uals in the considerate leadership condition achieved a higher level of

quality than those exposed to charismatic leaders in the first trial, this

difference in qualitative performance appears to decrease from trial to

trial. The data were plotted in figure 1 for both quantitative and qualita-

tive performance, and post hoc tests were conducted to illuminate this

finding further.

Figure 1 indicates that participants in the considerate condition

achieved higher quantitative and qualitative performance in the first

trial than did the subjects in either the charismatic condition or the

structuring leadership condition. However, the Student-Newman-Keuls

post hoc analysis results reported in table 3 indicate that significant

differences existed only during trials 1 and 2 between the considerate

and the charismatic and structuring conditions, and during trial 2 be-

tween the considerate and the structuring condition. For qualitative per-

formance, figure 1 shows that the performance of individuals in the

considerate leadership condition appears to level off in the third trial,

while the performance of participants in the charismatic leadership con-

dition seems to improve at a faster rate than those of participants in

This content downloaded from

202.56.183.21 on Thu, 22 Oct 2020 07:03:29 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

416

TABLE 2 Repeated Measures Analysis of Variance Summary Table for the Dependent Measures

MANCOVA Results

(With Self-Efficacy

MANOVA Results as Covariate)

Mean

Dependent Measure and Source of Variation df Squared F η2 MS F η2

Performance quantity for trials 1–4:

Leadership style 2 .75 2.51* .08 .07 .70 .02

Trial 3 .76 17.83*** .23 .05 1.32 .02

Style by trial 6 .06 1.44 .05 .04 1.09 .04

Performance quality for trials 1–4:

Leadership style 2 738.25 3.06* .09 190.87 1.49 .05

Trial 3 164.65 6.33*** .10 106.65 4.01** .07

Style by trial 6 29.56 1.14 .04 22.80 .86 .03

Self-efficacy with respect to performance quantity for trials 1–4:

Leadership style 2 21.23 3.44* .11

Trial 3 2.98 2.68* .04

Style by trial 6 1.98 1.78 .06

Self-efficacy with respect to performance quality for trials 1–4:

Leadership style 2 18.66 3.18* .10

Trial 3 2.87 3.19 .05

Style by trial 6 2.28 2.54 .08

* p ⬍ .05.

** p ⬍ .01.

This content downloaded from

*** p ⬍ .0001.

202.56.183.21 on Thu, 22 Oct 2020 07:03:29 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Journal of Business

Leadership Style 417

b

Fig. 1.—Plots of the effect of leadership style on quantitative and qualitative

performance over four trials. a, The y-axis is performance quantity. b, The y-axis

is performance quality.

either of the other conditions. The results of the Student-Newman-

Keuls post hoc analyses of the qualitative performance measures (see

table 3) provide statistical support for these findings. Individuals ex-

posed to a considerate leader had significantly higher qualitative perfor-

mance at the .05 level than did individuals in the charismatic and struc-

turing conditions during the first trial. Individuals in the considerate and

charismatic conditions had significantly higher performance quality at

the .05 level than did individuals in the structuring condition in the

second trial. However, no two groups demonstrated statistically sig-

nificant differences in qualitative performance at the .05 level during

the third and fourth trials.

While the above results show that leadership style had a significant

This content downloaded from

202.56.183.21 on Thu, 22 Oct 2020 07:03:29 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

418 Journal of Business

TABLE 3 Post Hoc Analysis Results

Analysis of

Variance Results

Source of Variance: Student-Newman-Keuls Test:

Leadership Style df MS F Significantly Different Pairs

Performance quantity

at trial:

1 2 .16 4.42* Considerate → Charismatic

Considerate → Structuring

2 2 .36 3.56* Considerate → Structuring

3 2 .23 1.54 None

4 2 .07 .37 None

Performance quality

at trial:

1 2 215.36 4.01* Considerate → Charismatic

Considerate → Structuring

2 2 382.89 4.43** Considerate → Structuring

Charismatic → Structuring

3 2 165.39 1.87 None

4 2 79.45 .76 None

* p ⬍ .05.

** p ⬍ .01.

effect on performance improvement over time, individuals exposed to

charismatic leaders did not outperform those exposed to considerate

leaders in this experiment; thus hypothesis 1 is not supported.

C. Self-Efficacy as Mediator

In order to test the hypothesis that self-efficacy would mediate the rela-

tionship between leadership style and performance (hypothesis 2), it

was first necessary to determine whether leadership style had a sig-

nificant effect on self-efficacy. The results of the repeated-measures

multivariate analysis of variance (see table 2) reveal that there was a

significant effect of leadership style on quantitative and qualitative

performance self-efficacy over time (F ⫽ 3.44 and 3.18, respectively,

p ⬍ .05). The η2 values indicate that leadership style explained 11%

of the variance in quantitative performance self-efficacy and 10% of the

variance in qualitative performance self-efficacy. The effects of self-

efficacy on both quantitative task performance and qualitative task

performance were also significant. Analysis of variance indicates that

self-efficacy beliefs explained 9.3% of the variance in quantitative per-

formance and 7.8% of the variance in qualitative performance (e.g.,

F ⫽ 5.71 and 4.73, respectively, for self-efficacy at trial 4, p ⬍ .05).

To test for mediation, quantitative and qualitative performance self-

efficacy beliefs measured prior to trials 1, 2, 3, and 4 were added as

covariates to the MANOVA analyses. The results of the repeated-mea-

sures multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA), shown in the

This content downloaded from

202.56.183.21 on Thu, 22 Oct 2020 07:03:29 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Leadership Style 419

last three columns of table 2, indicate support for the hypothesis. That

is, when self-efficacy was added to the analysis, the effect of leadership

style on both quantitative and qualitative performance became statisti-

cally nonsignificant (F ⫽ 0.70 and 1.49, respectively, p ⬎ .05).

IV. Discussion

This study supports Howell and Frost’s (1989) conclusion that leader-

ship styles can be isolated, identified, and distinguished from each other

and studied under controlled laboratory conditions; it also shows that

individuals can be trained to exhibit various leadership behaviors. With

respect to charismatic leadership, previous laboratory experiments

studied its effect on the performance of managerial (Howell and Frost

1989) and clerical (Kirkpatrick and Locke 1996) tasks at one moment

in time. Thus, one major contribution of this study is that the effect

of charismatic leadership on the performance of a realistic, technical,

manufacturing task over a series of trials was examined.

The results of this study indicated that individuals working under

considerate leaders outperformed qualitatively individuals working un-

der charismatic and structuring leaders in the first trial; those working

under considerate leaders also outperformed qualitatively individuals

working under structuring leaders in the second trial. These results sug-

gest that by emphasizing the comfort and well-being of participants,

considerate leaders may reduce the stress and uncertainty associated

with a complex, unfamiliar manufacturing task. To speculate, the com-

munication of the importance of quality improvement by the charis-

matic leader may have made the participants more careful at the outset,

perhaps affecting their initial performance. By the second trial, after

another leadership intervention, individuals working under charismatic

leaders improved their qualitative performance substantially. A possi-

ble explanation is that the expression of confidence in individuals’ task

performance by the charismatic leader may encourage participants to

invest greater sustained effort toward improving the quality of their

performance over time. Finally, consistent with prior research, partici-

pants working under structuring leaders never outperformed those

working under considerate or charismatic leaders, and they performed

significantly worse at the outset.

Individuals exposed to considerate leaders had consistently higher

output quantity than those working under either structuring or charis-

matic leaders in the current study. This finding indicates that, by focus-

ing on the comfort and well-being of individuals, considerate leaders

may help them to relax and work faster than do structuring leaders who

emphasize the amount of work to be accomplished and the amount of

time allowed. In the charismatic leadership manipulation, the articu-

lated goal and communication of high-performance expectations fo-

This content downloaded from

202.56.183.21 on Thu, 22 Oct 2020 07:03:29 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

420 Journal of Business

cused on the importance of achieving high-performance quality, not

quantity. Perhaps this quality focus influenced the participants to be

more careful about the quality of their work at the expense of speed.

This finding points to the importance of crafting vision statements that

encourage all of the desired behaviors.

This study supports the notion that leadership style does have an

effect on performance improvement over time. Although the consider-

ate leader appeared to be able to obtain superior performance from

individuals at the outset, the results support a cautious conclusion that

the charismatic leader was also able to sustain persistent individual

effort with respect to the quality of the work over time.

The present study also indicates that self-efficacy plays an important

mediating role in the relationship between leadership style and perfor-

mance quality. This supports Bandura’s (1986) suggestion that the per-

formance of individuals can be enhanced by persuading them that they

are capable of performing the task at hand. Further, this study suggests

that various leadership styles affect self-efficacy in different ways. For

example, considerate leadership appears to have had an immediate ef-

fect on the performance and self-efficacy of the participants of this

study, while charismatic leadership seems to have taken longer to have

an effect and structuring leadership appears to have had no effect.

While the findings with respect to the effect of leadership style on

task performance and self-efficacy support the notion that it is at least

in part because of their impact on individuals’ beliefs in their ability

to perform a task that certain leadership styles can influence individual

performance, more research is needed for a thorough understanding of

how these effects are transmitted.

V. Limitations and Future Research

The limitations of this study include those associated with experiments

in general. While steps were taken to enhance the realism of the experi-

ment, the limited number of trials, the use of undergraduate students,

and the contrived setting suggest caution with respect to the generaliz-

ability of its results. For example, the performance of individuals ex-

posed to charismatic leaders caught up with and slightly exceeded that

of individuals exposed to considerate leaders in the fourth and final

trial of this experiment. It is not possible in the context of this study

to anticipate what would have happened in subsequent trials or to draw

definite conclusions about the long-term effect of the three leader-

ship styles. To understand further the mechanisms whereby leaders

affect follower performance, repeated-measures experimental designs

of longer duration or longitudinal field studies are needed.

This content downloaded from

202.56.183.21 on Thu, 22 Oct 2020 07:03:29 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Leadership Style 421

Appendix

Operationalization of the Three Leadership Styles

Charismatic-Style Operationalization

Verbal behaviors. The leader is trained to articulate an ideological goal re-

lating to the importance of quality improvement to maintain competitiveness,

communicate high performance expectations with respect to the quality improve-

ment achieved by participants over the four trials, and exhibit confidence in partic-

ipants’ ability to meet such expectations.

Nonverbal behaviors. The leader is trained to alternate between pacing and

sitting on the edge of the desk, lean toward participants, and maintain direct eye

contact, a relaxed posture, and animated facial expressions.

Interaction style. The leader projects a powerful, dynamic, confident image.

Paralinguistic cues. The leader demonstrates a high level of intonation: a

captivating, engaging voice tone.

Structuring-Style Operationalization

Verbal behaviors. The leader is trained to emphasize the meeting of deadlines

and quantity and quality of the work to be accomplished, schedule the work to

be done, and maintain standards of performance.

Nonverbal behaviors. The leader is trained to sit on the edge of the desk and

have periodic direct eye contact and neutral facial expressions.

Interaction style. The leader is neutral: neither warm nor cold.

Paralinguistic cues. The leader demonstrates some intonation: a businesslike,

factual voice tone.

Considerate-Style Operationalization

Verbal behaviors. The leader is trained to engage in participative two-way

conversation, express concern for the personal welfare of the participants, reas-

sure and relax the participants, and emphasize the comfort, well-being, and satis-

faction of the participants.

Nonverbal behaviors. The leader is trained to sit on the edge of the desk,

lean toward participants, maintain direct eye contact, and have a relaxed posture

and friendly facial expression (smiling).

Interaction style. The leader is friendly, approachable, responsive, apprecia-

tive, and willing to listen.

Paralinguistic cues. The leader demonstrates considerable intonation: a

warm, friendly voice tone.

References

Avolio, B. J.; Waldman, D. A.; and Einstein, W. O. 1988. Transformational leadership in

a management game simulation: Impacting the bottom line. Group and Organization

Studies 13:59–80.

Bandura, A. 1986. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory.

Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

This content downloaded from

202.56.183.21 on Thu, 22 Oct 2020 07:03:29 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

422 Journal of Business

Bandura, A. 1997. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York: W. H. Freeman &

Co.

Bandura, A.; Adams, N. E.; and Beyer, J. 1977. Cognitive processes mediating behavioral

change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 35:124–39.

Bandura, A.; Adams, N. E.; Hardy, A. B.; and Howells, G. N. 1980. Tests of the generality

of self-efficacy theory. Cognitive Therapy and Research 4:39–66.

Bandura, A., and Jourden, F. J. 1991. Self-regulatory mechanisms governing the impact

of social comparison on complex decision-making. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology 60:941–51.

Bass, B. M. 1990. Bass and Stogdill’s Handbook of Leadership: Theory, Research, and

Managerial Applications. 3d ed. New York: Free Press.

Frayne, C. A., and Latham, G. P. 1987. The application of social learning theory to em-

ployee self-management of attendance. Journal of Applied Psychology 72:387–92.

Garvin, D. A. 1984. What does ‘‘product quality’’ really mean? Sloan Management Review

26:25–43.

Gist, M. E. 1987. Self-efficacy: Implications for organizational behavior and human re-

source management. Academy of Management Review 12:472–85.

Gist, M. E.; Schwoerer, C.; and Rosen, B. 1989. Effects of alternative training methods

on self-efficacy and performance in computer software training. Journal of Applied Psy-

chology 74:884–91.

Hater, J. J., and Bass, B. M. 1988. Supervisors’ evaluations and subordinates’ perceptions

of transformational leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology 73:695–702.

House, R. J. 1988. Leadership research: Some forgotten, ignored, or overlooked findings.

In J. G. Hunt, B. R. Baliga, H. T. Dachler, and C. A. Schriesheim (eds.), Emerging

Leadership Vistas, pp. 246–60. Lexington, Mass.: Lexington Books.

House, R. J.; Spangler, W. D.; and Woycke, J. 1991. Personality and charisma in the

U.S. presidency: A psychological theory of leader effectiveness. Administrative Science

Quarterly 36:364–96.

Howell, J. M. 1986. Charismatic leadership: Effects of leadership style and group produc-

tivity on individual adjustment and performance. Ph.D. dissertation, University of British

Columbia.

Howell, J. M., and Avolio, B. J. 1993. Transformational leadership, transactional leader-

ship, locus of control and support for innovation: Key predictors of consolidated business

unit performance. Journal of Applied Psychology 78:891–902.

Howell, J. M., and Frost, P. J. 1989. A laboratory study of charismatic leadership. Organi-

zational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 43:243–69.

Kirkpatrick, S., and Locke, E. A. 1996. Direct and indirect effects of three core charismatic

leadership components on performance and attitudes. Journal of Applied Psychology

81:36–51.

Latham, G. P., and Frayne, C. A. 1989. Self-management training for increasing job atten-

dance: A follow-up and replication. Journal of Applied Psychology 74:411–16.

Lindsley, D. H.; Brass, D. J.; and Thomas, J. B. 1995. Efficacy-performance spirals: A

multilevel perspective. Academy of Management Review 20:645–78.

Locke, E. A.; Frederick, E.; Lee, C.; and Bobko, P. 1984. Effect of self-efficacy, goals

and task strategies on task performance. Journal of Applied Psychology 69:241–51.

Nunnally, J. C. 1978. Psychometric Theory. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Saks, A. M. 1995. Longitudinal field investigation of the moderating and mediating effects

of self-efficacy on the relationship between training and newcomer adjustment. Journal

of Applied Psychology 80:211–25.

Shamir, B.; House, R. J.; and Arthur, M. 1993. The motivational effects of charismatic

leadership: A self-concept based theory. Organization Science 4:1–17.

Smith, B. J. 1982. An initial test of a theory of charismatic leadership based on the re-

sponses of subordinates. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Toronto.

Wood, R. E., and Bandura, A. 1989. Social cognitive theory of organizational management.

Academy of Management Review 14:361–84.

This content downloaded from

202.56.183.21 on Thu, 22 Oct 2020 07:03:29 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Revision Guide For Anthology TextsDocument11 pagesRevision Guide For Anthology TextsIbra Elmahdy100% (2)

- Prophecies in Islam & Prophet Muhammad - A.aliDocument82 pagesProphecies in Islam & Prophet Muhammad - A.aliZaky MuzaffarNo ratings yet

- A Meta Analytic Review of Relationships Between Team Design Features and Team Performance - StewartDocument28 pagesA Meta Analytic Review of Relationships Between Team Design Features and Team Performance - StewartdpsmafiaNo ratings yet

- MZA Userguide PDFDocument8 pagesMZA Userguide PDFmark canolaNo ratings yet

- The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After The HolocaustDocument13 pagesThe Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After The HolocaustColumbia University Press100% (2)

- The Empowering Leadership Questionnaire: The Construction and Validation of A New Scale For Measuring Leader BehaviorsDocument22 pagesThe Empowering Leadership Questionnaire: The Construction and Validation of A New Scale For Measuring Leader Behaviorsnikola.chakraNo ratings yet

- Group Leadership: Efficacy and EffectivenessDocument17 pagesGroup Leadership: Efficacy and EffectivenessMaria AlzateNo ratings yet

- Team Performance Study: Determining The Factors That Influence High Performance in TeamsDocument8 pagesTeam Performance Study: Determining The Factors That Influence High Performance in Teamstarunsood2009No ratings yet

- 06 IJM LeadershipteamcohesivenessandteamperformanceDocument13 pages06 IJM LeadershipteamcohesivenessandteamperformanceMahendra paudel PaudelNo ratings yet

- Effective Dimension of Leadership StyleDocument11 pagesEffective Dimension of Leadership StyleDr. Khan Sarfaraz AliNo ratings yet

- 37 Icait2011 G4062Document15 pages37 Icait2011 G4062Aye Chan MayNo ratings yet

- The Empowering Leadership Questionnaire: The Construction and Validation of A New Scale For Measuring Leader BehaviorsDocument23 pagesThe Empowering Leadership Questionnaire: The Construction and Validation of A New Scale For Measuring Leader BehaviorsMohammed Mohammed Shoukry NaiemNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S104898431730053X MainDocument11 pages1 s2.0 S104898431730053X MainesracaneltNo ratings yet

- TransformationalLeadershipandCreativity PublicOpenDocument68 pagesTransformationalLeadershipandCreativity PublicOpenphuonghoaflyingNo ratings yet

- The Development of Collective Efficacy in Teams: A Multilevel and Longitudinal PerspectiveDocument12 pagesThe Development of Collective Efficacy in Teams: A Multilevel and Longitudinal PerspectiveFedrik Monte Kristo LimbongNo ratings yet

- The Shared Leadership of Teams A Meta Analysis of Proxim - 2014 - The Leadershi PDFDocument20 pagesThe Shared Leadership of Teams A Meta Analysis of Proxim - 2014 - The Leadershi PDFgeorge pintoNo ratings yet

- A Method of Assessing Leadership EffectivenessDocument17 pagesA Method of Assessing Leadership Effectivenessmazzleza100% (1)

- Achieving Organizational Effectiveness Through Employee Engagement: A Role of Leadership Style in WorkplaceDocument9 pagesAchieving Organizational Effectiveness Through Employee Engagement: A Role of Leadership Style in WorkplaceGaneshkumar SunderajooNo ratings yet

- HumilityDocument18 pagesHumilityKatherine LinNo ratings yet

- 9675-Article Text-36130-3-10-20161024Document12 pages9675-Article Text-36130-3-10-20161024mbauksupportNo ratings yet

- The Role of Transformational Leadership in Enhancing Organizational Innovation: Hypotheses and Some Preliminary FindingsDocument21 pagesThe Role of Transformational Leadership in Enhancing Organizational Innovation: Hypotheses and Some Preliminary Findingssamuel karnadyNo ratings yet

- IJMRES 5 Paper Vol 7 No1 2017Document28 pagesIJMRES 5 Paper Vol 7 No1 2017International Journal of Management Research and Emerging SciencesNo ratings yet

- How Leadership Behaviors Affect Organizational Performance in PakistanDocument10 pagesHow Leadership Behaviors Affect Organizational Performance in Pakistannyan hein aungNo ratings yet

- Empowered Leadership Influences Employee Motivation, Encourages Positive Behaviors, Lessens Emotional Exhaustion, and Reduces The Likelihood of TurnoverDocument18 pagesEmpowered Leadership Influences Employee Motivation, Encourages Positive Behaviors, Lessens Emotional Exhaustion, and Reduces The Likelihood of TurnoverInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Chapter 14 ArticleDocument16 pagesChapter 14 ArticlemohamedNo ratings yet

- Mohammed Et Al-2002-Journal of Organizational BehaviorDocument20 pagesMohammed Et Al-2002-Journal of Organizational BehaviorMuzaffar AbbasNo ratings yet

- 02 - Parris and Peachey 2013 - Servant Leadership-1Document17 pages02 - Parris and Peachey 2013 - Servant Leadership-1Paul RyanNo ratings yet

- From Common To Uncommon KnowledgeDocument37 pagesFrom Common To Uncommon KnowledgeasadqhseNo ratings yet

- Transformational LeadershipDocument20 pagesTransformational Leadershipvank343No ratings yet

- Effect of Leadership Styles Organizational Climate On Employee ProductivityDocument13 pagesEffect of Leadership Styles Organizational Climate On Employee ProductivityNazih YacoubNo ratings yet

- Ent LeadershipDocument38 pagesEnt LeadershipSofía AparisiNo ratings yet

- Shamir 1993Document19 pagesShamir 1993luisgalvanNo ratings yet

- 1 - Leadership Self Efficacy ScaleDocument22 pages1 - Leadership Self Efficacy ScalemddNo ratings yet

- Chapter One 1.1 Background To The StudyDocument142 pagesChapter One 1.1 Background To The StudyOla AdeolaNo ratings yet

- Gist 1992Document30 pagesGist 1992luisgalvanNo ratings yet

- EffectsofLeadershiponOrganizationalPerformance PDFDocument6 pagesEffectsofLeadershiponOrganizationalPerformance PDFVignesh MohanNo ratings yet

- Embracing Transformational Leadership: Team Values and The Impact of Leader Behavior On Team PerformanceDocument11 pagesEmbracing Transformational Leadership: Team Values and The Impact of Leader Behavior On Team PerformanceDimas Halim NugrahaNo ratings yet

- Thesis On Organisational BehaviourDocument8 pagesThesis On Organisational Behaviourheidiowensspringfield100% (2)

- 2000 - Sosik, Godshalk - Leadership Styles, Mentoring Functions Received, and Job Related Stress A Conceptual Model and Preliminary StudDocument27 pages2000 - Sosik, Godshalk - Leadership Styles, Mentoring Functions Received, and Job Related Stress A Conceptual Model and Preliminary Studekojulian_284861966No ratings yet

- 1 Vip,.Document22 pages1 Vip,.SAKHI JANNo ratings yet

- Bozionelos - Mentoring Provided - Relation To Mentor's Career Success, Personality, and Mentoring Received (2004)Document24 pagesBozionelos - Mentoring Provided - Relation To Mentor's Career Success, Personality, and Mentoring Received (2004)Aris VettosNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Leadership Styles On Organizational Culture and Firm Effectiveness: An Empirical StudyDocument16 pagesThe Impact of Leadership Styles On Organizational Culture and Firm Effectiveness: An Empirical StudyJuby JoyNo ratings yet

- Moderating Effects of Group Cohesiveness in Competency-Performance Relationships: A Multi-Level StudyDocument16 pagesModerating Effects of Group Cohesiveness in Competency-Performance Relationships: A Multi-Level StudyLidya WijayaNo ratings yet

- PCX - ReportDocument35 pagesPCX - ReportMerwyn FernandesNo ratings yet

- Abbreviated Self Leadership Questionnaire - Vol7.Iss2 - Houghton - pp216-232 PDFDocument17 pagesAbbreviated Self Leadership Questionnaire - Vol7.Iss2 - Houghton - pp216-232 PDFArdrian GollerNo ratings yet

- Examining Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire Construct - A Validation Study in The Public Hospitals of Sindh, PakistanDocument13 pagesExamining Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire Construct - A Validation Study in The Public Hospitals of Sindh, Pakistanelias saqqaNo ratings yet

- Iwb 1Document15 pagesIwb 1Niaz Bin MiskeenNo ratings yet

- Thompson Et Al 2021 The Impact of Transformational Leadership and Interactional Justice On Follower Performance andDocument10 pagesThompson Et Al 2021 The Impact of Transformational Leadership and Interactional Justice On Follower Performance andBiya RasyidNo ratings yet

- The Empowering Leadership Questionnaire The Construction and Validation of A New Scale For Measuring Leader BehaviorsDocument22 pagesThe Empowering Leadership Questionnaire The Construction and Validation of A New Scale For Measuring Leader BehaviorsKEE POH LEE MoeNo ratings yet

- ARTICLE1 Organizational Leadership Styles and Their Impact On Employees Job SatisfactionDocument14 pagesARTICLE1 Organizational Leadership Styles and Their Impact On Employees Job SatisfactionMelissa Kayla ManiulitNo ratings yet

- Transformational Leadership. Case Study-Wal-Mart: IoannadimitrakakiDocument7 pagesTransformational Leadership. Case Study-Wal-Mart: Ioannadimitrakakiajmrr editorNo ratings yet

- Jung-EffectsLeadershipStyle-1999Document12 pagesJung-EffectsLeadershipStyle-1999s3967945No ratings yet

- en Human Oriented Leadership and OrganizatiDocument7 pagesen Human Oriented Leadership and OrganizatiLeoniNo ratings yet

- Effects of Leadership On Organizational PerformanceDocument5 pagesEffects of Leadership On Organizational Performancenyan hein aungNo ratings yet

- Research Proposal 2Document7 pagesResearch Proposal 2Noor FatimaNo ratings yet

- Podsakoff 1996 HFHFHFGDocument40 pagesPodsakoff 1996 HFHFHFGVali GhitaNo ratings yet

- M LQ InstrumentDocument14 pagesM LQ Instrumentnoreen rafiqNo ratings yet

- Organizational Effectiveness: A Case Study of Telecommunication and Banking Sector of PakistanDocument13 pagesOrganizational Effectiveness: A Case Study of Telecommunication and Banking Sector of PakistanSara AwniNo ratings yet

- Title: Effect of Discrimination On Employees' PerformancesDocument28 pagesTitle: Effect of Discrimination On Employees' PerformancesAksh ChananiNo ratings yet

- LMX & IwbDocument20 pagesLMX & Iwbmuhammad ishaqNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Analysis Leadership QualitiesDocument26 pagesResearch Paper Analysis Leadership QualitiesRakesh Sahu100% (2)

- 1 s2.0 S1048984317300607 MainDocument25 pages1 s2.0 S1048984317300607 MainRizky AmeliaNo ratings yet

- Leadership Best Practices and Employee Performance: A Phenomenological Telecommunications Industry StudyFrom EverandLeadership Best Practices and Employee Performance: A Phenomenological Telecommunications Industry StudyNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 202.56.183.21 On Thu, 22 Oct 2020 06:59:10 UTCDocument25 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 202.56.183.21 On Thu, 22 Oct 2020 06:59:10 UTCMukhtar NusratNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 202.56.183.21 On Thu, 22 Oct 2020 07:35:34 UTCDocument21 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 202.56.183.21 On Thu, 22 Oct 2020 07:35:34 UTCMukhtar NusratNo ratings yet

- Role of Supportive Leadership As A Moderator Between Job Stress and Job PerformanceDocument9 pagesRole of Supportive Leadership As A Moderator Between Job Stress and Job PerformanceMukhtar NusratNo ratings yet

- The Central and Eastern European Online Library: SourceDocument13 pagesThe Central and Eastern European Online Library: SourceMukhtar NusratNo ratings yet

- Letter of Recommendation For Office AssistantDocument1 pageLetter of Recommendation For Office AssistantMukhtar Nusrat0% (1)

- Literature Review Table - DemoDocument2 pagesLiterature Review Table - DemoMukhtar NusratNo ratings yet

- Zero To OneDocument8 pagesZero To OneMukhtar NusratNo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson PlanDocument12 pagesDetailed Lesson PlanIrishNo ratings yet

- Special EducationDocument13 pagesSpecial EducationJanelle CandidatoNo ratings yet

- Effect of Reciprocal Teaching and Motivation On Reading Comprehension2016Document5 pagesEffect of Reciprocal Teaching and Motivation On Reading Comprehension2016Aqila HafeezNo ratings yet

- 1 Year Bachillerato VERB TENSES REVIEWDocument4 pages1 Year Bachillerato VERB TENSES REVIEWLucía CatalinaNo ratings yet

- Gemini Column CareDocument3 pagesGemini Column CareLee MingTingNo ratings yet

- Determination of Chromium VI Concentration Via Absorption Spectroscopy ExperimentDocument12 pagesDetermination of Chromium VI Concentration Via Absorption Spectroscopy ExperimentHani ZahraNo ratings yet

- Experiment 1 Safety Measures: Use and Preparation of Chemical Substance 1.1 ObjectivesDocument8 pagesExperiment 1 Safety Measures: Use and Preparation of Chemical Substance 1.1 ObjectivesMaldini JosnonNo ratings yet

- Variations of Food Consumption Patterns in DCs and LDCsDocument3 pagesVariations of Food Consumption Patterns in DCs and LDCsCathPang-Mak100% (1)

- Master Degree InformationDocument3 pagesMaster Degree InformationBivash NiroulaNo ratings yet

- EMDocument41 pagesEMle.nhu.quynh.lqdNo ratings yet

- Meaning and Nature of SMDocument3 pagesMeaning and Nature of SMArpit SharmaNo ratings yet

- Ga8238 PDFDocument3 pagesGa8238 PDFAstri Indra MustikaNo ratings yet

- Kunci-Jawaban Howard AntonDocument41 pagesKunci-Jawaban Howard AntonAlyagariniNo ratings yet

- CAN For Vehicles HugoProvencher 2Document67 pagesCAN For Vehicles HugoProvencher 2Skyline DvNo ratings yet

- FunctionDocument3 pagesFunctionGeraldo RochaNo ratings yet

- EBTax Tax Simulator Webcast 16 Jul 14pdfDocument49 pagesEBTax Tax Simulator Webcast 16 Jul 14pdfM.MedinaNo ratings yet

- English Literature AnthologyDocument25 pagesEnglish Literature AnthologyShrean RafiqNo ratings yet

- Pelargonium Sidoides SA 4Document1 pagePelargonium Sidoides SA 4rin_ndNo ratings yet

- E.M Year 10 Term 2 NotesDocument25 pagesE.M Year 10 Term 2 NotesNANCYNo ratings yet

- Research ProposalDocument9 pagesResearch Proposalsyed arslan aliNo ratings yet

- Electrical Engineering: Power ElectronicsDocument13 pagesElectrical Engineering: Power ElectronicsSaif UddinNo ratings yet

- Advisement Slip Student No.: Name: Semester: 2 Semester Course/Section: Bs Mathematics 1B School Year: 2020 - 2021Document1 pageAdvisement Slip Student No.: Name: Semester: 2 Semester Course/Section: Bs Mathematics 1B School Year: 2020 - 2021OLASIMAN, SHAN ANGELNo ratings yet

- The Emoji Factor: Humanizing The Emerging Law of Digital SpeechDocument33 pagesThe Emoji Factor: Humanizing The Emerging Law of Digital SpeechCityNewsTorontoNo ratings yet

- The Amsart, Amsproc, and Amsbook Document ClassesDocument79 pagesThe Amsart, Amsproc, and Amsbook Document ClassesiordacheNo ratings yet

- Water Quality For Supercritical Units Steag FormatDocument40 pagesWater Quality For Supercritical Units Steag FormatAmit MukherjeeNo ratings yet

- Improving Machine Translation With Conditional Sequence Generative Adversarial NetsDocument10 pagesImproving Machine Translation With Conditional Sequence Generative Adversarial Netsmihai ilieNo ratings yet