Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Language Maintenance and Spread in Algeria PDF

Language Maintenance and Spread in Algeria PDF

Uploaded by

AmiraOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Language Maintenance and Spread in Algeria PDF

Language Maintenance and Spread in Algeria PDF

Uploaded by

AmiraCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/249918399

Language Maintenance and Spread: French in Algeria

Article in International Journal of Francophone Studies · March 2007

DOI: 10.1386/ijfs.10.1and2.193_1

CITATIONS READS

22 4,110

1 author:

Mohamed Benrabah

Université Stendhal - Grenoble 3

10 PUBLICATIONS 119 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Undoing the "Old World": The Politics of Language in Colonial and Post-Colonial Algeria View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Mohamed Benrabah on 09 March 2015.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

IJFS 10.1-2_12_art_Benrabah.qxd 2/21/07 8:35 PM Page 193

International Journal of Francophone Studies Volume 10 Numbers 1 and 2

© 2007 Intellect Ltd.

English Language. doi: 10.1386/ijfs.10.1and2.193/1

Language maintenance and spread:

French in Algeria

Mohamed Benrabah Université Stendhal Grenoble III

Abstract Keywords

The present article studies the survival of French in Algeria despite an assertive policy Algeria

of linguistic Arabization designed, among other things, to displace French. This Arabization

language has been maintained and the number of its users has increased substantially French

since independence. Four major factors affecting language maintenance are considered language attitudes

here against a background of social change: economic change, demographic growth, language policy

institutional support and language status. In addition to these ‘measurable’ predictors language maintenance

of language survival, the attitudes of senior secondary school students towards

French and other languages were investigated via a large survey. All four social

factors proved important for explaining the maintenance of French. The results of the

survey revealed that respondents were attached to the ex-colonizers’ language. The

study concludes with a number of implications for language planning in Algeria.

Résumé

Cet article étudie la question du maintien de la langue française en Algérie en dépit

d’une politique d’arabisation volontariste conçue, entre autres, pour l’éradiquer. Le

français s’est non seulement maintenu mais que le nombre de ses locuteurs algériens

a connu une nette augmentation. Des différents changements sociaux intervenus

durant la période de transition post-coloniale l’auteur a privilégié quatre facteurs pou-

vant expliquer ce processus de maintien linguistique: les changements économiques,

le développement démographique, le soutien des institutions et le statut des langues en

présence. L’étude s’est également basée sur les résultats d’un questionnaire portant

sur les attitudes des lycéens envers le français et d’autres langues en présence en

Algérie. Les quatre facteurs choisis se sont avérés important pour rendre compte du

maintien du français. Quant aux attitudes linguistiques, les lycéens ont montré leur

attachement à la langue française. Enfin, l’article évoque un certain nombre d’impli-

cations pour tout aménagement linguistique futur en Algérie.

When the French occupation ended in 1962, Algeria’s elites were exuber-

antly confident in the complete replacement of French by Arabic as the

medium of the vital functions of the country. As an illustration of these

beliefs, typical of the time, here is how, in 1963, a leading Algerian

poet/writer forecast this development:

In ten to fifteen years…, Arabic will have replaced French completely and

English will be on its way to replacing French as a second language. French

IJFS 10 (1+2) 193–215 © Intellect Ltd 2007 193

IJFS 10.1-2_12_art_Benrabah.qxd 2/21/07 8:35 PM Page 194

1 Quoted in D.C. is a clear and beautiful language, … but it holds too many bitter memories

Gordon, The Passing for us.1

of French Algeria,

London: Oxford

University Press, The attitude of Algerians towards the French language is a complex one

1966, p. 113. mainly because of recent history. During colonial rule (1830–1962), there

2 B. Stora, Algérie. was some ambivalence in the roles assigned to French. On the one hand,

Formation d’une that language symbolized foreign exploitation and was thus to be resisted,

nation, Biarritz:

Atlantica, 1998, but, on the other, because of the universal values it conveyed (liberty,

pp. 27–28. equality, fraternity), it also served as a tool to raise the population’s aware-

3 M. Bennoune, ness and support in favour of such resistance.2

Education, Culture et After independence, language policies for achieving the two objectives

développement en mentioned in the above quote were implemented. From the end of the

Algérie. Bilan &

perspectives du système 1970s to the early 1990s, French was taught as a subject and as the first

éducatif, Algiers: mandatory foreign language, starting from the fourth grade in the pri-

Marinoor-ENAG, mary cycle. English was the second foreign language, introduced in Middle

2000, p. 303;

M. Benrabah, ‘La School (eighth grade). Under the influence of the pro-Arabization lobby,

question linguistique’, the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education introduced English in

in Y. Belaskri and primary school as a competitor to French in September 1993. Thus, the

C. Chaulet-Achour

(eds.), L’Epreuve d’une Grade Four pupils (8–9 year olds) had to choose between French and

décennie 1992–2002. English as the first mandatory foreign language.3 For the Minister of

Algérie arts et culture, Education, English was ‘the language of scientific knowledge’4 and for

Paris: Editions Paris-

Méditerranée, 2004a, opponents of Arabic–French bilingualism, French was ‘“par essence” une

pp. 95–96. langue “impérialiste” et “colonialiste”’.5 Unexpectedly, the competition

4 Haut Conseil de la between the two European languages turned in favour of French and the

Francophonie (HCF) prediction made in 1963 by the Algerian poet/writer quoted above was

(1999), Etat de la startlingly wrong. Between 1993 and 1997, out of 2 million schoolchildren

francophonie dans le

monde. Données in Grade Four, the total number of those who chose English was insignifi-

1997–1998 et 6 cant – between 0.33% and 1.28%.6

études inédites, Nancy: Arabization, or the language policy implemented to displace French

La Documentation

Française, 1999, altogether, failed. From a quantitative point of view, today’s Algeria is the

p. 28. second largest French-speaking community in the world.7 After indepen-

5 S. Goumeziane, Le dence, out of a total population of 10 million people around 90% were

Mal algérien. Economie illiterate.8 In 1963, the total number of literate people stood at 1,300,000

politique d’une transi- (approximately 12% of the total population) and linguistic competence in

tion inachevée

1962–1994, Paris: Standard Arabic was relatively low.9 Algerians who could read Literary

Librairie Arthème Arabic only were estimated at 300,00010 while 1 million read French and

Fayard, 1994, p. 258. 6 million spoke French.11 In 1990, there were 6,650,000 francophones in

6 M. Miliani, ‘Teaching Algeria with 150,000 L1 speakers and 6,500,000 L2 speakers.12

English in a According to Rossillon,13 the total number of French speakers in Algeria

Multilingual Context:

The Algerian case’,

amounted to 49% in 1993 (for a population of 27.3 million) and projec-

Mediterranean Journal tions for the year 2003 were 67%. Recent polls have confirmed this trend.

of Educational Studies, In April 2000, the Abassa Institute polled 1,400 households and found

6: 1, 2000, p. 23;

A. Queffélec,

that 60% understood and/or spoke French. These percentages represent

Y. Derradji, V. Debov, 14 million Algerians aged 16 and over.14 The most recent poll conducted

D. Smaali-Dekdouk by the same Institute suggests that Rossillon’s projections were more or less

and Y. Cherrad-

Benchefra, Le Français

accurate. Out of 8,325 young Algerians polled in 36 wilayas (provinces) in

en Algérie. Lexique et November 2004, 66% declared they spoke French and 15% English.15

dynamique des langues, However, if the number of francophone users has increased substantially,

Brussels: Editions

Duculot, 2002, p. 38.

the use of French in a number of higher domains has diminished since the

colonial era when that language held an unassailable position in the

194 Mohamed Benrabah

IJFS 10.1-2_12_art_Benrabah.qxd 2/21/07 8:35 PM Page 195

media, education, government and administration. The functions allo- 7 T. Oberlé, ‘Algérie.

Nous occupons une

cated to institutional Arabic have expanded as a result of the Algerian gov- place croissante dans

ernment’s commitment via its official language policy. For example, l’enseignement

Arabization is either complete or almost complete in the Ministry of public. L’horizon

désensablé’, Le Figaro

Justice, the Ministry of Religious Affairs and the registry offices in town littéraire. Spécial fran-

halls and, to a lesser extent, the Ministry of Education. In the educational cophonie, 18 March,

sector, a shift to Literary Arabic as the language of instruction has 2004, p. 9 ; J.P.

Péroncel-Hugoz,

occurred since 1962 mainly at primary and secondary levels. But in uni- ‘Les origines d’une

versities French is still the key language for studies in scientific disciplines “guerre civile

and has remained the language with higher social status and prestige.16 culturelle”’, Le Monde,

19 May,1994,

Apart from the ministries where Arabization is complete or partial, in the pp. ii–iii;

other government departments not all official documents are exclusively A. Queffélec,

written in Arabic: they are often written in French and then only trans- Y. Derradji, V. Debov,

D. Smaali-Dekdouk

lated into Arabic when required.17 and Y. Cherrad-

As these figures readily show, the policy of linguistic Arabization which Benchefra, Le Français

targeted, among other things, the French language has not been successful. en Algérie. Lexique et

dynamique des langues,

One of the main objectives of Arabization was to make Algerians abandon p. 118.

French as well as their first languages (Algerian Arabic and Tamazight or

Berber) in favour of Literary Arabic as the primary means of communica- 8 M. Bennoune,

Education, Culture et

tion and socialization (in the media, administration, education, home and développement en

employment) and of English as the first mandatory foreign language. In Algérie. Bilan &

spite of an overly Arabized Algeria, French did not succumb to competition perspectives du système

éducatif, Algiers:

from both institutional Arabic and English. Algeria’s language policy was Marinoor-ENAG,

unsuccessful in encouraging Algerians to give up French. Against all odds, 2000, p. 12 ; A.A.

not only has the latter survived but it has also increased in terms of number Heggoy, ‘Colonial

Education in Algeria:

of users. Specialists describe this process of language survival and expan- Assimilation and

sion as respectively, language maintenance – the other side of the coin Reaction’, in P.G.

being language shift or death – and language spread. Altbach and G. Kelly

(eds.), Education and

the Colonial

Language maintenance and spread as linguistic fields Experience, New

of inquiry Brunswick, N.J.:

Transaction Books,

In 1964, Joshua Fishman proposed the concepts of ‘maintenance’ and 1984, p. 111.

‘shift’ as fields of linguistic inquiry.18 Language maintenance refers to the

9 G. Grandguillaume,

continuing use of a language or language variety in the face of competi- ‘L’Algérie, une iden-

tion from a more prestigious or politically more powerful language. tité à rechercher’,

Language shift simply means the replacement of one language or lan- Economie et

Humanisme, 309:

guage variety by another in certain domains of social life. Robert Cooper September–October,

coined the term ‘language spread’ in 1982 to describe the process 1989, p. 49; M.

whereby ‘the uses or the users of a language increase’.19 Cooper’s concept Lacheraf, L’Algérie,

nation et société,

is a rather neutral term for describing language imposition via a process of Algiers: SNED, 1978,

political expansion by a colonial power. In the history of Algeria, Arabic p. 313.

spread as a result of military conquest by Muslim armies, from the seventh 10 C.F. Gallagher, ‘North

century onwards. More recently, the French language spread as a result of African Problems and

France’s colonial expansion during the nineteenth and twentieth cen- Prospects: Language

and Identity’, in J.A.

turies. But language spread can also take place as the outcome of a process Fishman, C.A.

of acquisition in schools (language-in-education planning or acquisition Ferguson and J. Das

planning) and language promotion.20 The recent and overwhelming Gupta (eds.), Language

Problems of Developing

weight of research on language maintenance and shift has tended to focus Nations, New York:

on ethnolinguistic minorities in immigration countries. Scholars involved John Wiley and Sons,

in this field of research seem to have been more concerned with language 1968, p. 148; D.C.

Language maintenance and spread: French in Algeria 195

IJFS 10.1-2_12_art_Benrabah.qxd 2/21/07 8:35 PM Page 196

Gordon, The French shift than with language maintenance and/or spread.21 And to the best of

Language and National

Identity, The Hague: this author’s knowledge, very little is known about language maintenance

Mouton, 1978, and spread of ex-colonial languages despite assertive language policies

p. 151. implemented in the postcolonial period to displace them.

11 C.F. Gallagher, ‘North This study involves an attempt to contribute to the discussion around

African Problems the question of language maintenance and spread in contexts not neces-

and Prospects:

Language and sarily concerned with minority groups. Its tenure concerns the sociolin-

Identity’, p. 134. guistic aspect of the maintenance and spread of French in Algeria. It is a

12 L. Depecker, Les Mots

search for the set of conditions that lead people to keep languages and not

de la francophonie, succumb to competition from another language or languages. In the litera-

Paris: Editions Belin, ture, methods used to study language maintenance/spread (or shift/death)

1990, p. 389.

have relied on two sets of data. First, researchers have used measurable fac-

13 P. Rossillon, Atlas de tors (like urbanization, migration, shifts in economic indicators, etc.) that

la langue française,

Paris: Bordas, 1995,

provide information on cultural values. Second, they have made use of

p. 91. indirect measurements such as survey data.22 In this article, both types of

14 T. Assia, ‘Sondage:

data will be used when appropriate; that is, sociological factors and infor-

l’Algérie, premier mation collected with the help of a large survey based on an attitude ques-

pays francophone tionnaire.

après la France’, El

Watan, 2 November,

In fact, there is considerable consensus in the subfield of language

2000, p. 24. maintenance and shift in the sense that there is no single set of sociologi-

15 Z.A. Maïche, ‘Enquête

cal factors that can be used to predict maintenance or shift.23 Several rea-

nationale sur les sons may be responsible for language shift. Moreover, these factors do not

besoins des jeunes. La operate independently but are interrelated in a complex way. Fasold,24 for

recherche d’un

emploi, première

example, lists around seven such causes: societal bilingualism, migration,

occupation’, El industrialization and other economic changes, school language and other

Watan, 29 November, governmental forms of pressure, urbanization, prestige and demographic

2004, p. 32.

size. Kaplan and Baldauf25 mention three such factors: absence/presence

16 M. Benrabah, of intergenerational transmission, maintenance/displacement of commu-

Language- nication registers or domains as a result of socio-economic prestige, demo-

in-Education

Planning in Algeria: graphic contraction/expansion of the community. Broadly speaking then,

Historical there are some reasons which relate to prestige, political or economic cri-

Development and teria and others which have to do with the role played by major social

Current Issues,

Language Policy, forth- institutions such as the media, education, family relationships and friend-

coming a. ship networks.26 Some linguists have grouped the frequently cited factors

17 M. Benrabah, ‘The into four major categories: economic changes, demographic factors, insti-

Language Planning tutional support and language status.27 This classification is adopted here

Situation in Algeria’, because it is perceived as most relevant to the purpose of this study. Thus,

Current Issues in

Language Planning, in the next section, each of the above ecological factors will be discussed in

6: 4, 2005, p. 454; turn in relation to its link with the maintenance of French in Algeria.

A. Queffélec, However, not to be overlooked, with regard to the present study, is the

Y. Derradji, V. Debov,

D. Smaali-Dekdouk notion of ‘social change’ defined by Cooper28 as ‘the appearance of new

and Y. Cherrad- social and cultural patterns of behaviour among specific groups within a

Benchefra, Le Français society or within the society as a whole’. In order to explain social change,

en Algérie. Lexique et

dynamique des langues, Cooper mentions several theories amongst which the ‘functionalist view’

pp. 70–72. seems to apply to the Algerian case. The functionalist view favours ‘the

18 J.A. Fishman, interrelatedness of all parts of the system, with changes in one part rippling

‘Language throughout the system to cause changes in other parts’.29 In other words,

Maintenance and changes in one part of the Algerian society (as a system) ripple throughout

Shift as Fields of

Inquiry’, Linguistics, the system to cause changes in other parts. Eight different invaders more

9, 1964, pp. 32–70. or less shaped the social history of Algeria and its sociolinguistic profile.

196 Mohamed Benrabah

IJFS 10.1-2_12_art_Benrabah.qxd 2/21/07 8:35 PM Page 197

The Berbers, the indigenous populations, came under the yoke of the 19 R.L. Cooper,

‘A Framework for the

Phoenicians (860 BCE), the Romans (second century BCE), the Vandals Study of Language

(429 CE), the Romanized Byzantines (533 CE), the Arabs (647/648 CE), Spread’, in R.L.

the Spanish (1505), the Turks (1529) and the French (1830). One of the Cooper (ed.),

Language Spread:

consequences of this long history of intermingling of populations is language Studies in Diffusion

contact and its by-product multilingualism – Berber–Punic, Berber– and Social Change,

Punic–Latin, Berber–Arabic, Berber–Arabic–Spanish–Turkish, Berber–Arabic– Bloomington:

Indiana University

French, etc.30 The two recent periods seem to lend most validity to the Press, 1982, p. vii.

functionalist theory of social change in Algeria: the French colonial occu-

20 J. Swann,

pation and the postcolonial transition following the liberation of the country. A. Deumert, T. Lillis

In the next section, we will first examine some changes affecting Algeria’s and R. Mesthrie,

economy after 1962. A Dictionary of

Sociolinguistics,

Edinburgh:

Economic changes Edinburgh University

Since 1962, Algeria’s economic development has gone through three Press, 2004, p. 175.

main phases. The first phase corresponds to the period immediately fol- 21 J.A. Fishman,

lowing independence and marked by two sectors. The ‘modern’ sector in Reversing Language

Shift. Theoretical and

agriculture and the mining industry was completely integrated within the Empirical Foundations

French economy and almost exclusively geared towards the needs of the of Assistance to

colonist minority – around 1 million people.31 Within this economy, 2.5 million Threatened Languages,

Clevedon:

Algerians occupied junior posts only. The ‘traditional’ sector consisted of the Multilingual Matters

‘poorest’ lands with low crop yield occupied by the majority of the rural Ltd., 1991; S. Gal,

indigenous population (6.5 million) living in very poor conditions since Language Shift. Social

Determinants of

the beginning of colonization in 1830. In terms of living standards, the Linguistic Change in

difference between the two communities was striking. In rural areas, the Bilingual, Austria,

European colonists had 30 times more land than Algerians and they New York: Academic

Press, 1979;

owned more than 2.5 million acres in the fertile coastal plain in the north H. Slavik, ‘Language

of Algeria. This surface represented 30% of total farming lands and pro- Maintenance and

duced 60% of the total agricultural produce. As to incomes, the colonists’ Language Shift

Among Maltese

were 48 times higher than those of the indigenous population.32 With Migrants in Ontario

independence (1961–62), 900,000 European colonists, who had been in and British

charge of almost all the economic and administrative sectors, fled the Columbia’,

International Journal of

country. Algeria’s economy was completely disorganized. Active unem- the Sociology of

ployment affected 2 million people and about 2,600,000 had no means of Language, 152, 2001,

support. By spring 1965, more than 450,000 Algerians had emigrated in pp. 131–52;

M. Tannenbaum, and

the pursuit of better living conditions and to remake their lives somewhere M. Berkovich,

else.33 By the mid-1990s, the Algerian community in France rose to ‘Family Relations

around 800,000. Many members of this community have kept close ties and Language

Maintenance:

with members of their families in Algeria. These ties work in favour of the Implications for

maintenance of French in this country.34 Language Educational

The second phase, called the ‘postcolonial transition’ lasted until the Policies’, Language

Policy, 4: 3, 2005,

end of the 1980s.35 After the military coup in June 1965, the new regime pp. 287–309.

adopted radical economic and foreign policies within the context of revo-

22 R. Fasold, Introduction

lutionary ideologies in Arab countries and the rest of the world. to Sociolinguistics: The

Economic policies gave priority to industrialization. The model adopted Sociolinguistics of

for economic development came under the Soviet influence on the one Society, Oxford:

Blackwell, 1984,

hand and the ‘developmentalist’ school of economics on the other.36 With p. 216.

the ex-Soviet Union the Algerian economy shared a number of features,

23 id.; R. Mesthrie,

such as high levels of financial investment in heavy industry considered J. Swann, A. Deumert

to be the most important sector, acquisition of state-of-the-art technologies

Language maintenance and spread: French in Algeria 197

IJFS 10.1-2_12_art_Benrabah.qxd 2/21/07 8:35 PM Page 198

and W.L. Leap, and vertical planning with hierarchical control.37 Academics from the

Introducing

Sociolinguistics,

French developmentalist school of economics argued that Algeria’s post-

Philadelphia: John colonial transition could only succeed if it rapidly moved away from an

Benjamins Publishing under-developed, mainly agricultural state to an industrialized one and

Company, 2000,

p. 255.

that heavy industry could help the country overcome its dependence on

hydrocarbons and modernize its agriculture – food self-sufficiency and

24 R. Fasold, Introduction

to Sociolinguistics: The

export of agricultural produce.38 To do so, Algeria had to give the utmost

Sociolinguistics of priority to the ‘industrializing industries’39 which included the ‘steel indus-

Society, p. 216–17. try’, ‘mechanical engineering’, ‘electromechanical engineering’, ‘chem-

25 R.B. Kaplan and R.B. istry’ and ‘energy’.40 These French economic theoreticians also insisted on

Baldauf Jr., Language the importance of the state as the major actor for implementing such a

Planning from Practice

to Theory, Clevedon:

strategy.41 The result is a highly centralized ‘administered’ rentist socio-

Multilingual Matters, economic system.42 Within a decade, the industrializing industries strategy

1997, 273–75. turned Algeria’s economy from an agricultural mono-exporting state to a

26 M.E. García, ‘Recent petroleum mono-exporting one. Within two decades GNP structure

Research on changed substantially in favour of hydrocarbons at the expense of the agri-

Language

Maintenance’, Annual

culture sector: agriculture GNP which was 31.5% in 1957 fell to 5.5% in

Review of Applied 1977; the hydrocarbons and mining GNP which was 5.5% in 1957

Linguistics, 23, 2003, reached 33% in 1977.43 The number of workers in the agricultural sector,

p. 24.

which represented 50% in 1967, fell to less than 30% in 1982.44

27 R. Mesthrie, The Algerian model of development adopted by the revolutionary regime

J. Swann, A. Deumert led to the generalized inefficiency of the economic machine45: an inefficient

and W.L Leap,

Introducing agricultural sector, waste, additional costs and under-utilization of the

Sociolinguistics, industrial production capacity could not allow the economy to reach the

Philadelphia: John projected goals. What is more, Algeria suffered from the Dutch disease effect

Benjamins Publishing

Company, 2000, in the 1980s following the high rise in international oil prices of the 1970s.

pp. 255–58. In other words, high oil revenues led to high investments in industry and to

28 R.L. Cooper, Language debts contracted with foreign financial institutions. But the situation wors-

Planning and Social ened when oil prices in the international market collapsed and the dollar

Change, Cambridge: was devalued in 1986. Consequently, inefficient economic activities gener-

Cambridge University

Press, 1989, p. 164. ated social tensions which culminated in the October 1988 uprisings.

The third economic phase, initiated after these events, aimed at imple-

29 id., p. 177.

menting a diversified market economy to create a favourable environment

30 M. Benrabah, ‘The for foreign and domestic investment and ease social tensions. 46 In the

Language Planning

Situation in Algeria’, mid-1990s, when the government could not repay its external debt the

pp. 391–400. International Monetary Fund (IMF) imposed a structural adjustment

31 G. Destanne de programme (April 1994–March 1995 and April 1995–March 1998) to

Bernis, ‘Les industries further an economic transition process to a market economy. 47 The result

industrialisantes et of these economic reforms was macro-economic stabilization which bene-

les options

algériennes’, Revue fited from the substantial increase in financial facilities generated by high

Tiers-Monde, 12: 47, hydrocarbon revenues: rising crude prices registered since the end of 1999

1971, p. 546. led to state coffers overflowing and a context of excess liquidity in the

32 S. Goumeziane, Le banking system.48 But this healthy macro-economic state was not

Mal algérien. Economie matched at the micro-economic level which was marked by bankruptcy

politique d’une transi-

tion inachevée and ruin.49 Among the ‘structural reforms’ urgently needed, there was the

1962–1994., 1994, one that concerned education as a way of eradicating, among other

52 ; M. Ollivier, ‘Les things, Islamist fanaticism50 fuelled by the Algerian educational system.51

choix industriels’, in

M. Lakehal (ed.), Indeed, two heads of state, Mohamed Boudiaf (in office between January

Algérie, de and June 1992) and the current president, Abdelaziz Bouteflika, spoke

l’indépendance à l’état publicly of ‘l’école sinistrée’. In a nation-wide television address in

198 Mohamed Benrabah

IJFS 10.1-2_12_art_Benrabah.qxd 2/21/07 8:35 PM Page 199

July 1999, President Bouteflika declared: ‘le niveau a atteint un seuil d’urgence, Paris:

Larmises-

intolérable’.52 L’Harmattan, 1992,

The major cause of this educational failure is the implementation of p. 113 ; O. Si Ameur

Arabic monolingualism in schools. This language education policy and N. Sidhoum,

‘L’emploi et le

(Arabization) goes back to the second phase of economic development (the chômage, de

nationalist ‘postcolonial’ transition). The educational reforms conducted in l’euphorie à la crise’,

the 1970s provided education with three major goals: to enforce universal in M. Lakehal (ed.),

Algérie, de

schooling through democratization of education; to promote the acquisi- l’indépendance à l’état

tion of science and technology so as to facilitate its transfer from industrial- d’urgence, Paris:

ized nations; to implement Arabization as a way of expanding Algerians’ Larmises-

L’Harmattan, 1992,

competence in Classical Arabic.53 The regime’s Arabization drive was p. 14.

intended to accompany a ‘Cultural Revolution’ – revive the Arabo-Islamic

culture, and identity and ‘go back to’ to what ideologues believed to be the 33 O. Si Ameur and

N. Sidhoum,

‘essence’ of Algeria, that is an Arabic-speaking country – and to link ‘L’emploi et le

Algeria to the rest of the Arab (revolutionary) world, regarded then as the chômage, de

cultural counter-weight to the imperialist West, headed by France.54 l’euphorie à la crise’,

p. 146; B. Stora,

Transition towards a market economy and the demands of internationalism Histoire de l’Algérie

have led the authorities to commit the educational sector to new reforms depuis l’indépendance

that would re-establish Arabic–French bilingualism and the pre-eminence (1962–1988), Paris:

Editions La

of French as the tool for the teaching of science and technology. Indeed, Découverte, 2001,

since September 2003, French has been introduced as the first mandatory pp. 26–9.

foreign language in Grade Two (6–7 year olds) of the primary cycle and 34 M. Benrabah, Langue

English in the first grade of Middle Schools.55 Despite the recommendations et pouvoir en Algérie.

made by the National Commission for the Reform of the Educational Histoire d’un trauma-

tisme linguistique,

System in mid-March 2001, French has not been re-introduced as the Paris: Éditions

medium for teaching scientific disciplines in secondary education. This reco- Séguier, 1999,

mmendation answers a powerful demand among Algeria’s population. In p. 269 ; P. Rossillon,

Atlas de la langue

1999, a survey conducted for the authorities revealed that 75% of française, 1995, p. 90.

Algerians supported the idea of teaching scientific school subjects in

35 S. Goumeziane, Le

French.56 In fact, Arabization failed to turn Literary Arabic into the lan- Mal algérien. Economie

guage of ‘iron and steel’ as its promoters used to describe it, a function still politique

attached to French, which remains the ‘language for bread’.57 The expression d’une transition

inachevée 1962–1994,

language for bread refers to the language that carries with it ‘economic pp. 18–19.

advantages’.58 In her report on young Algerians’ daily life in spring 2004, a

36 A. Dahmani, L’Algérie

French journalist described as follows the lost opportunities for Algeria’s à l’épreuve. Economie

youth due to lack of linguistic competence. (Their only chance was to engage politique des réformes

in trabendo – a word of Spanish origin meaning ‘smuggling’.) 1980–1997, Paris:

L’Harmattan, 1999,

p. 31 ; S. Goumeziane,

[C]eux qui n’ont connu que les bancs de l’école algérienne, ceux qui ne par- Le Mal algérien.

lent qu’arabe, ceux qui ne sont jamais allés à l’étranger, ont-ils des chances Economie politique

d’une transition

de profiter du ‘boom’ actuel? ‘Ce sera plus difficile pour eux’, reconnaît Samir inachevée 1962–1994,

Aït Aoudia [chef d’entreprise], tandis qu’un autre directeur d’entreprise p. 38.

répond net: ‘No way!’ 37 S. Goumeziane, Le

Maîtriser plusieurs langues est utile pour réussir ailleurs que dans le tra- Mal algérien. Economie

bendo, mais parler français est un imperatif59. politique d’une

transition inachevée

1962–1994, p. 54 ;

Demographic changes and urbanization G. Hidouci, Algérie.

La libération inachevée.

In addition to agricultural and industrial inefficiency, the economic develop- Paris: Editions La

ment of Algeria (postcolonial transition) was also hampered by an unprece- Découverte, 1995,

dented population growth which went unchecked by the authorities. p. 37; B. Stora,

Language maintenance and spread: French in Algeria 199

IJFS 10.1-2_12_art_Benrabah.qxd 2/21/07 8:35 PM Page 200

Histoire de l’Algérie Government officials used to respond to internal and external warnings by

depuis l’indépendance

(1962–1988), 2001,

the then popular Third Worldist slogan ‘the best contraceptive is develop-

p. 47. ment’.60 From 10 million inhabitants in 1962, the population grew to 23

38 A. Dahmani, L’Algérie

million in 1987, 29.5 million in 1997 and an estimated 32,531,853

à l’épreuve. Economie today.61 In 1975, the fertility rate reached almost the world record with 8.1

politique des réformes children born per woman.62 Between 1960 and 1990, population growth in

1980–1997., p. 31;

M. Ollivier, ‘Les choix

Algeria was the highest in the Maghreb and the Developing World: the

industriels’, in growth rate increased substantially from 2.0% to 3.3% in Algeria while

M. Lakehal (ed.), the mean average for developing countries decreased from 2.3% to 1.9% for

Algérie, de

l’indépendance à l’état

the respective years (see Table 1). In 1983 and then in 1985, the Algerian

d’urgence, Paris: government resigned itself to adopting a national programme of birth control.

Larmises- It aimed to accompany a social trend resulting from a rise in female education

L’Harmattan, 1992,

p. 130.

and women joining the job market.63 For example, by the end of the 1980s,

75% of girls were enrolled in educational institutions and 8% had a job.64

39 G. Destanne de Both the growth and fertility rates went down in the 1980s and 1990s:

Bernis, ‘Industries

industrialisantes et 2.8% growth with 5.5 children born per woman in 1986, 2.5% growth

contenu d’une with 4.5 children born per woman in 1990 and 2.1% with 3.85 children

politique born per woman in 1995.65

d’intégration

régionale’, Economie With such high birth rates, 70% of the population was aged 30 and

appliquée, 19: 3–4, under in the early 1990s. Today they represent 62.7%67. Unlike most of

1966, pp. 415–73; their elders, the youth in general does not feel resentful about France and

G. Destanne de

Bernis, ‘Les industries its heritage in their country. Our original hypothesis was that without for-

industrialisantes et getting French colonialism, young people considered it as part of Algeria’s

les options history.68 To confirm or refute this hypothesis, an attitudinal direct closed-

algériennes’, Revue

Tiers-Monde, 12: 47, choice questionnaire was distributed to 1,051 Algerian secondary school

1971, pp. 545–63. students in April/May 2004. Informants were registered in Lycées in three

40 A. Dahmani, L’Algérie cities in the west of the country. The urban centres were chosen according

à l’épreuve. Economie to the number of their inhabitants: Oran as the large city, Saïda and

politique des réformes Ghazaouet as medium-sized and small-sized centres, respectively. Of all

1980–1997, p. 31.

informants 57.5% were female and the rest male. All respondents were

41 B. Stora, Histoire de aged between 14–15 and 20 and the 17–18 year olds represented 57.5%.

l’Algérie depuis

l’indépendance In one part of the written questionnaire, students had to indicate, along a

(1962–1988), p. 44. Likert attitude scale, the strength of their agreement or disagreement with

42 H. Beblawi and a series of 25 statements on a five-point range. Two statements were

G. Luciani, The Rentier intended to measure respondents’ reactions to the status of French in

State, London: Croom Algeria (see Table 2). For the first statement, the majority of all informants

Helm, 1987; B.L.

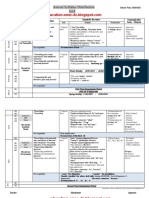

Five year periods (1950–90)

Countries 1950–55 1955–60 1960–65 1965–70 1970–75 1975–80 1980–85 1985–90

Tunisia 1.8 1.8 1.9 2.0 1.8 2.6 2.1 2.3

Algeria 2.1 2.1 2.0 2.9 3.1 3.1 3.0 3.3

Morocco 2.5 2.8 2.7 2.8 2.5 2.9 3.2 3.1

Mean for 2.1 2.1 2.3 2.55 2.4 2.1 2.0 1.9

Developing

Polities

Table 1: Evolution of population growth rate (1950–90) (percentages for yearly mean average).66

200 Mohamed Benrabah

IJFS 10.1-2_12_art_Benrabah.qxd 2/21/07 8:35 PM Page 201

1 2 3 4 5

Agree Agree Neither Disagree Disagree

completely agree nor completely

Statement disagree

1) As an Algerian, I consider 15.5% 23.2% 11.1% 28.8% 20.2%

French a foreign language like (163) (244) (117) (303) (212)

German, English and Spanish.

2) French is part of Algeria’s 12.3% 32.4% 13.5% 19.4% 20.2%

heritage. (129) (341) (142) (204) (212)

Table 2: Language attitudes: French as ‘heritage’.

did not consider French as a ‘foreign language’ in the way they did Dillman, State and

German, English and Spanish. As to the second statement, the difference is Private Sector in

Algeria. The Politics of

not as high as for the first statement. Yet, subjects who considered the Rent-Seeking and

French language as part of Algeria’s heritage are slightly higher than Failed Development,

those who did not share this view. Boulder: Westview

Press, 2000;

A final factor related to demography is urbanization, which has been F. Talahite, ‘Economie

favourable to the spread of French in Algeria since its conquest by France. administrée, corrup-

The economic policy of industrialization in the 1970s led to a radical deval- tion et engrenage de

la violence en

uation of farm work. Peasants, of which there were 7 million in 1973, Algérie’, Revue Tiers

chose to settle in urban centres. This exodus reached 100,000 migrants a Monde, 41: 161,

year in the 1970s.69 Moreover, the rural population, which represented January–March

2000, pp. 49–74;

67% of the population in 1966, dropped to 58% in 1977.70 The present P. Vieille, ‘Le pétrole

level of urbanization is estimated at 61.7%.71 In fact, before industrialization, comme rapport

the level of urbanization in Algeria had been rising steadily ever since the social’, Peuples

Méditerranéens /

conquering French armies entered the country in 1830. The destruction of Mediterranean Peoples,

the tribal system and the complete disintegration of Algeria’s traditional 26, 1984, pp. 3–29.

society following land expropriation led several groups of landless peasants 43 H. Temmar, H.

to migrate to the outskirts of towns and cities mainly created by and for the Stratégie de développe-

European settlers (Pieds Noirs) along the fertile Mediterranean coast. ment indépendant,

Algiers: Office des

Algerian migrants who did not leave the country came to live close to the Publications

French-speaking regions and thus also came into contact with the French Universitaires, 1983,

language.72 And the degree of urbanization also affected the spread of the pp. 267.

French language. On the eve of French occupation, the total urban popula- 44 S. Goumeziane, Le

tion in Algeria represented less than 5%.73 It was then an enormous rural Mal algérien. Economie

politique d’une transi-

area given over entirely to agriculture and nomadism. The first major tion inachevée

socio-demographic transformations took place during the second half of the 1962–1994,

nineteenth century: from 5% in 1830 the urban population rose to 13.9% pp. 58–59.

in 1886, 16.6% in 1906, 20.2% in 1926 and 25% in 1954.74 45 id., p. 83.

Paradoxically, events linked to the Algerian war of liberation 46 G. Hidouci, Algérie. La

(1954–62) reinforced the status of French among Algerians, with a major libération inachevée,

impact on their language attitudes in post-independent Algeria. When De Paris: Editions La

Découverte, 1995,

Gaulle took office in May 1958, he introduced an ambitious Five-Year Plan pp. 178–237.

(the Constantine Plan) to provide Algeria with an economic solution to its

47 A. Dahmani, L’Algérie

turmoil. In 1959 and 1960, vast new horizons of schooling were opened à l’épreuve. Economie

to children who had so far been excluded from learning, especially in the politique des réformes

countryside. French language and culture did not have much influence on 1980–1997,

Language maintenance and spread: French in Algeria 201

IJFS 10.1-2_12_art_Benrabah.qxd 2/21/07 8:35 PM Page 202

pp. 184–92; I. the illiterate peasantry, completely ignored by the Pieds Noirs, since

Martín, ‘Algeria’s European colonialism in Algeria was a coastal phenomenon. So, apart

Political Economy

(1999–2002): An from those villagers who discovered the French language and culture as

Economic Solution to soldiers or factory workers in France during the 1914–18 world conflict,

the Crisis?’, The the vast majority of the population was not influenced by literacy and

Journal of North

African Studies, 8: 2, ideals of rational culture and democracy. The Algerian war of liberation

2003, p. 7. was to change all this.

48 Algeria Interface, In the military field, the French counter-revolutionary strategy aimed at

Information Service draining away the ‘water’ in order to asphyxiate the ‘fish’ and deprive

on Internet about Algerian fighters of any contact with a population which provided them

Algeria, http://www.

algeria-interface. with food and shelter. So ‘regroupment camps’ and ‘pacification zones’

com/new/article. were created in 1954 and generalized in 1957 and 1958. By 1960, the

Accessed 18 French army transferred around 2 million villagers – representing 24% of

November 2004;

International the total Muslim population.75 These uprooted rural populations, which

Monetary Fund (IMF), had had no contact with the présence française, discovered the French lan-

Algeria: Selected Issues guage and culture in schools provided by the military, who favoured poor

and Statistical

Appendix. IMF Country populations living in remote areas. After liberation, the majority of dis-

Report No. 04/31. placed people preferred to settle in urban centres deserted by the Pieds Noirs

February 2004, who had left the country.76 Between 1960 and 1963, 800,000 people

Washington, D.C.:

International moved to towns and cities. They swelled the population in urban centres

Monetary Fund which had been in contact with French for many years. Their sons and

Publications, daughters would take part in the reinforcement of French acculturation

http://www.imf.org.

Accessed 27 intensified by the end of the war of Algeria. In fact, one of the major para-

September 2004. p. 4. doxes of this armed struggle was a quantitative and qualitative increase in

49 O. Benderra, ‘Les the spread of francophonie in Algeria described as a ‘delayed Frenchifying

réseaux au pouvoir’, process’.77 This process was to have far reaching effects on Algerians’ lan-

Confluences guage attitudes and internal representations in the post-independent era.

Méditerranée, 45:

Spring, 2003; One question comes to mind when the age and urbanization variables

W. Byrd, ‘Contre are taken together. Does the added effect of those two factors (age and

performances urbanization) affect young Algerians’ attitude towards French as the lan-

économiques

et fragilité institution- guage of the ex-colonizers? Indeed, memories of French colonialism have

nelle’, not completely faded away. In the written questionnaire discussed above,

Confluences Méditerra another task consisted in associating 30 statements with one of the four

née, 45:

Spring, 2003; major languages of Algeria (Algerian Arabic, Literary Arabic, French and

N. Gillet, Tamazight). In Table 3, the responses to the statement about which lan-

‘Macroéconomie. guage was felt to be associated with a painful past (i.e. colonialism) are

Etat financier

excellent malgré tabulated. The majority (53.3%) chose French. It is worth noting here that

les archaisms’, it is the only statement/task where a substantial number of informants did

Marchés Tropicaux, not respond (91 out of 1,051).

3057, 11 June,

2004a,; I. Martín, The results presented in Table 3 are confirmed by responses to one

‘Algeria’s Political Eco statement in the Likert scale activity. For this task, only 26 informants

Algerian Literary French Tamazight Total

Arabic Arabic

Statement Resp. % Resp. % Resp. % Resp. % Resp.

Language associated

201 20.9 105 10.9 509 53.3 145 15.1 960

with a painful past

Table 3: Language attitudes: Language and painful past (colonialism).

202 Mohamed Benrabah

IJFS 10.1-2_12_art_Benrabah.qxd 2/21/07 8:35 PM Page 203

nomy (1999–2002):

1 2 3 4 5 An Economic Solutio

Agree Agree Neither Disagree Disagree n to the Crisis?’,

completely agree nor completely The Journal of North

Statement disagree African Studies, 8:

2, 2003; S. Moatti,

‘Algérie:

I associate French with 17.8% 28.2% 16.9% 21.8% 12.8% l’économie confi-

colonization. (187) (296) (178) (229) (135) squée’, Alternatives Ec

onomiques, 224,

Table 4: Language attitudes: language associated with colonialism. April 2004.

50 I. Martín, ‘Algeria’s

(2.5%) did not respond but the number of undecided respondents is quite Political Economy

(1999–2002): An

high: 178 responses or 16.9% (see the third column in Table 4). From a Economic Solution to

statistical point of view, the gender variable does not yield any significant the Crisis?’, p. 41.

results, but the difference between cities is statistically significant. In 51 M. Benrabah, Langue

Table 5, p< represents the significance level which is simply the probability et pouvoir en Algérie.

that the change in the independent variable (size of urban centre) was due to Histoire d’un trauma-

tisme linguistique,

chance factors alone. There is a convention whereby the significance Paris: Éditions

level of probability p = 0.05 is referred to as significant and the significance Séguier, 1999,

level of probability p = 0.01 and lower (p = 0.000) is referred to as highly pp. 154–60;

M. Benrabah,

significant.78 In Table 5, .000 means that the independent variable was ‘Language and

responsible for the differences between the three groups of students. Politics in Algeria’,

Hence, and as shown in Table 5, the larger the city the less students asso- Nationalism and Ethnic

Politics, 10: 1, 2004b,

ciated French with a painful past (colonialism) and vice versa. These pp. 71–73; W. Byrd,

results tend to show that the French colonial era is an enduring memory ‘Contre performances

in less populated towns and cities. économiques et

fragilité

institutionnelle’,

Institutional support 2003, p. 78 ; J.M.

Another Algerian paradox concerns the language policies implemented in Coffman, Arabization

and Islamisation in the

the educational system and their effect on the maintenance and spread of Algerian University,

French. Indeed, the universalization of education following independence Ph.D dissertation,

probably served as the major support for the expansion of the ex-colonial Stanford University,

1992, p. 147, 185.

idiom usually acquired as a second language. It is quite ironic that inde-

pendent Algeria has done more to assist the spread of this language than 52 M. Benrabah,

L’Epreuve d’une

the colonial authorities did throughout the 132 years of French presence. décennie 1992–2002.

As part of their ‘civilizing mission’, the French colonial authorities used a Algérie arts et culture,

methodical assimilationist policy of deracination and deculturization between p. 99 ; M. Benrabah,

‘An Algerian Paradox:

1830 and 1962.79 Part of this ‘mission’ was to impose the supremacy of the Arabisation and the

French language and culture over the indigenous languages and cultures.80 French Language’, in

Reading and writing skills, considered to be widely spread among Y. Rocheron and

C. Rolfe (eds.), Shifting

Algerians prior to the French occupation and which were estimated Frontiers of France and

at 40% to 50%, dropped dramatically to around 10% by 1962.81 This Francophonie, Oxford:

high rate of illiteracy was the result of two trends. First, because of the Peter Lang, 2004d,

p. 52.

53 A. Benachenhou,

Large town Medium town Small town p< ‘L’accès au savoir

scientifique et

Statement Oran (%) Saïda (%) Ghazaouet (%) technique’, in

M. Lakehal (ed.),

Language associated 43.0% 54.4% 59.1% .000 Algérie, de

with a painful past: l’indépendance à l’état

d’urgence, Paris:

Table 5: Association of French with painful past (colonialism) and size of town. Larmises-

L’Harmattan, 1992,

Language maintenance and spread: French in Algeria 203

IJFS 10.1-2_12_art_Benrabah.qxd 2/21/07 8:35 PM Page 204

p. 210. aggressive nature of colonial assimilationist policies, Algerian parents

54 J.E. Lewis, ‘Freedom refused to send their children to French schools as a way of resisting the

of Speech — in any occupation.82 Second, the European settlers who controlled the administra-

Language’, Middle

East Quarterly,

tion were strong opponents of any schooling for Algerians beyond low-level

Summer, 2004, vocational training. They feared the birth of nationalist sentiment among

http://www.meforum. Algerians and they clearly articulated it. For example, General Tirman, a

org/article/635.

Accessed 8 December

French Governor, declared in the 1870s: ‘L’hostilité de l’indigène se

2005. mesur[e] à son degré d’instruction’.83

As a result of the demise of French colonialism, and with it educational

55 M. Benrabah, ‘The

Language Planning segregation, the country has witnessed an influx of student enrolment. In

Situation in September 1962, 600,000 children of school age joined the primary cycle.

Algeria’p. 450. This represented 80% of the number of enrolments during the final year of

56 B. Djamel, ‘Réforme colonization.84 In secondary schools there were 48,000 pupils in 1962,

de l’école, les islamo- that is far more registrations than in 1961. However, following the mass

conservateurs

accusent’, Le Matin, exodus of the Pieds Noirs, the number of students enrolled at the University

19 March, 2001, p. 3. of Algiers dropped from 5,000 to 2,500 amongst which only 600 were

57 M. Benrabah, Algerian.85 The government’s decisions were to accompany the popula-

Language- tion’s yearning for more education. The High Commission for the

in-Education Planning Educational Reform met for the first time in December 1962 and recom-

in Algeria: Historical

Development and mended, among other things, the democratization of public instruction.86

Current Issues, forth- And the post-independent high birth rates discussed above generated a

coming a; G. formidable demand for education. As an illustration of this rise in the

Grandguillaume,

‘L’Arabisation au school population, Table 6 shows the total number of enrolments in

Maghreb’, Revue Fundamental (primary and middle) schools as well as in secondary

d’Aménagement schools between 1979 and 1998. The latest figures confirm a similar

Linguistique, 107,

2004, pp. 35–36. trend: there were 7,805,000 pupils in primary, middle and secondary levels

in September 200387 and 600,000 university students in 2000.88

58 D. Ager, Motivation in

Language Planning and Of course, not all French second-language learning takes place at

Language Policy, school. Competence in French is also gained by young people when they

Clevedon: Multilingual find it necessary to participate in the wider society (for example, the eco-

Matters Ltd., 2001,

pp. 36–37. nomic sphere discussed above). Another institution that has facilitated the

acquisition and spread of the French language is publishing and the

59 F. Beaugé, ‘Algérie,

envies de vie’, media. The first national publishing house, known by its French acronym

Le Monde, 7 April,

2004, p. 17.

Year Total in Secondary Secondary Total Total

60 B. Stora, Histoire de Fundamental Technical General Secondary

l’Algérie depuis School School School School

l’indépendance

(1962–1988), p. 62. 1979–80 3,799,154 12,770 170,435 183,205 3,982,359

61 African Development

Bank Group (ADBG),

1983–84 4,463,056 32,086 293,783 325,869 4,788,925

Basic indicators on 1986–87 5,107,883 98,300 405,008 505,308 5,611,191

African countries –

Comp, 1989–90 5,436,134 165,182 588,765 753,949 6,190,081

http://www.afdb.org/

african_countries/info 1991–93 5,994,409 129,122 618,030 747,152 6,741,561

rmation_comparison.

htm. Accessed 18 1995–96 6,309,289 69,195 784,108 853,303 7,162,592

November 2004;

Central Intelligence 1997–98 6,556,768 64,988 814,102 879,090 7,435,858

Agency (CIA) (2005),

The World Factbook – Table 6: Enrolments in Fundamental and secondary schools between 1979 and

Algeria,

http://www.cia.gov/ 1998.89

204 Mohamed Benrabah

IJFS 10.1-2_12_art_Benrabah.qxd 2/21/07 8:35 PM Page 205

SNED (Société Nationale d’Edition et de Diffusion), was founded in 1966. By cia/publications/fact-

book/geos/ag.html.

1973, the SNED had published 268 books in French and 287 in Arabic.90 Accessed

The Office des Presses Universitaires, created in the 1970s, published 1,382 27 September 2005;

books in Arabic and 1,633 in French (55%). According to Latifa Kadi, O. Si Ameur and N.

Sidhoum, ‘L’emploi et

French publications represent more than half the total works published by le chômage, de

the public and private sectors.91 Soon after independence, the various peri- l’euphorie à la crise’,

odicals and journals, which had been under colonial ownership, came M. Lakehal (ed.),

Algérie, de

under the central authorities’ control. By 1984, the circulation of the l’indépendance à l’état

French-medium daily El Moudjahid represented twice that of three major d’urgence, Paris:

Arabic-medium dailies.92 The post-October 1988 political liberalization Larmises-

L’Harmattan, 1992,

witnessed the birth of an important private sector in the written press. In p. 148.

1993, the circulation of dailies in French was roughly three times that of

62 B. Stora, Histoire de

dailies in Arabic: 625,000 for the former and 220,000 for the latter.93 By l’Algérie depuis

1998, those figures had risen to 780,905 and 364,500, respectively.94 As l’indépendance

for recent circulation, there were, in June 2004, 26 francophone dailies (1962–1988), p. 62.

and 20 arabophone ones with a total circulation of 1,600,000 – half for 63 id., p. 63.

each language.95

64 M. Khelladi, ‘Les

The above-mentioned figures for press circulation are quite low com- données

pared with the total literate population of Algeria. They illustrate the crisis démographiques’, in

that faces Algeria’s national press resulting, among other things, from the M. Lakehal (ed.),

Algérie, de

competing audio-visual media in general and satellite television in partic- l’indépendance à l’état

ular. Since 1962, out of three national radio stations, one of them called d’urgence Paris:

‘Chaîne III’ has catered for the French-speaking audience. As far as televi- Larmises-

L’Harmattan, 1992,

sion is concerned, Algerian viewers prefer international channels because p. 183.

of the dull and doctrinaire quality of the programmes aired by the single

65 A. Dahmani, L’Algérie

national TV channel named Entreprise Nationale de Television (ENTV). à l’épreuve. Economie

(Derisive nicknames like ‘l’Unique’ or ‘Canal Moins’ an ironic allusion to politique des réformes

the French TV channel called ‘Canal Plus’ are used by the man in the 1980–1997, p. 243.

street to refer to ENTV.) According to Rossillon,96 one Algerian household 66 Source: R. Escallier,

in two had a satellite dish by the mid-1990s. In 1992 between 9 and 12 ‘Démographie: obses-

sion du nombre et

million Algerians watched French TV channels.97 And on a daily basis, considérable

52% of Algerian households watch French TV channels.98 In November rajeunissement de la

2004, Canal-satellite and TPS, the two major French TV scrambling com- population’, in

Y. Lacoste, and

panies, put an end to Algerian hackers’ practice of illegally decoding their C. Lacoste (eds.,

coded channels. For many Algerians ‘il s’agit là d’une trahison de la L’Etat du Maghreb,

France’ arguing that: ‘Dans les familles, les enfants ont appris à parler Paris: Editions La

Découverte, 1991,

français non pas à l’école, mais en regardant les dessins animés à la télévi- p. 82.

sion. Si l’on doit regarder les chaînes arabes, ils ne seront plus bilingues’.99

67 Y.M. Riols, ‘Le drame

Indeed, satellite TV provides an adequate learning environment for young d’être jeune en

Algerians who have been noted to speak acceptable French even without Algérie’, L’Expansion,

any previous instruction in the language in educational institutions.100 690: October, 2004,

pp. 50–51 ; O. Si

Ameur and

Language status N. Sidhoum,

Decolonization has resulted in changes in the status of the two languages ‘L’emploi et le

that were in competition during the colonial period, i.e. Literary Arabic chômage, de

l’euphorie à la crise’,

and French. At that time, the dominant status of French was founded on in M. Lakehal (ed.),

the ‘inferiorization’, if not erosion and death, of the cultures and languages Algérie, de

of the colonized. And from the point of view of linguistic representation and l’indépendance à l’état

d’urgence, Paris:

identification, speakers of ‘minority’ or stigmatized idioms tend to feel Larmises-

closer to their language than speakers of the ‘majority’ and dominant L’Harmattan, 1992,

Language maintenance and spread: French in Algeria 205

IJFS 10.1-2_12_art_Benrabah.qxd 2/21/07 8:35 PM Page 206

p. 148. language.101 (Nowadays in Algeria, the case of Algerian berberophones

68 M. Benrabah, supports this claim.) Independence has finally satisfied ‘demands for

‘Epuisement de la recognition’102 ignored by the French colonizers. The end of colonialism

légitimation par la

langue’, Némésis.

led to a complete reversal in the status of the two competing languages:

Revue d’Analyse Algeria’s legislation allowed the inferiorization of French and the recogni-

Juridique et Politique, tion of Literary Arabic (considered a foreign language during colonization)

5, 2004c, pp. 94–95.

as the national and official language of the country. Consequently, the ‘bit-

69 B. Stora, Histoire de ter memories’ mentioned in the Algerian poet/writer’s quote at the begin-

l’Algérie depuis

l’indépendance

ning of this article have somewhat faded away. The nationalist phase of

(1962–1988), p. 52. development (Cultural Revolution) of the late 1960s and most of the

1970s allowed the triumph of ideas held by some French language

70 S. Goumeziane, Le

Mal algérien. Economie authors like Malek Haddad well known for his laments over his ‘exile’ in

politique d’une transi- the French language and his inability to express himself. His internal con-

tion inachevée flicts and linguistic insecurity are best illustrated in his famous claim ‘Je

1962–1994, p. 59.

suis moins séparé de ma patrie par la Méditerranée que par la langue

71 Atlapedia, Countries française! Je suis incapable d’exprimer en arabe ce que je sens en arabe.’103

A to Z — Algeria,

2003, This exaggerated and emotional reaction to bilingualism in Algeria paved

http://www.atlapedia. the way for ideological intransigence, the agonizing over the French lan-

com/online/ guage and the near neurotic attitude towards it. It is a context that

countries/algeria.htm.

Accessed thwarted creative writing in French and authors either went into exile or

17 September 2003; stopped writing altogether.104 Malek Haddad was among the second

Central Intelligence group. The 1980s and 1990s in particular witnessed a surge in French

Agency (CIA) (2005),

The World Factbook writing in Algeria and the diaspora. This creative bonanza was accompa-

– Algeria, nied by the rejection of guilt-ridden attitudes towards French. Yasmina

http://www.cia.gov/ Khadra, the Algerian author whose literary work is the most widely trans-

cia/publications/ fact-

book/ geos/ag.html. lated in the world at the moment, represents this new trend.105 To an

Accessed Algerian journalist who asked him why he did not publish his works in

27 September 2005; Algeria, Yasmina Khadra declared in the autumn of 2005:

N. Gillet, ‘Les années

Bouteflika. Un bilan

contrasté’, Marchés Me demander d’éditer en Algérie me rappelle Malek Haddad contraint de

Tropicaux, 3057, 11 renoncer à son immense talent pour des considérations roturières: parce qu’il

June, 2004b,

p. 1313. écrivait en français ! Comme si la langue française était une maladie hon-

teuse, une hérésie. Résultat, la littérature algérienne a perdu prématurément

72 C.A. Sirles, ‘Politics

and Arabization: The l’un de ses grands maîtres. Ça ne marchera pas avec moi. On ne me fera pas

Evolution of taire de cette façon. J’adore la langue française et elle me le rend bien. Elle m’a

Postindependence appris tout ce que je sais et m’a fait connaître dans le monde entier.106

North Africa’,

International Journal of

the Sociology of There is one more social factor that affects language status and has far

Language, 137, 1999, reaching consequences on the internal representations and attitudes of

pp. 119–20.

Algerians towards the major languages of Algeria. This social element

73 A. Nouschi, springs from the language policy-makers’ linguistic behaviour which para-

‘Réflexions sur l’évo-

lution du maillage doxically tends to devalue the national language, Literary Arabic. And

urbain au Maghreb there are at least two aspects to this issue. The first one concerns language

(XIXe-XXe siècles)’, revitalization and/or vernacularization which turns an idiom used exclu-

Bulletin de la société

languedocienne de géo- sively in writing into the spoken language of everyday use.107 The individ-

graphie, 20: 2–3, ual’s home (family) represents the natural context for ‘intergenerational

1986, p. 197. language transmission’.108 For example, the successful revival of Hebrew

74 O. Khiar, ‘Migrations partly depended on its promoters’ linguistic behaviour (e.g. Eliezer Ben

dans les quatre Yehuda) which turned an almost dead idiom into a language of home

métropoles’, Revue

interaction. Here ‘the process of revitalization itself depended on the

206 Mohamed Benrabah

IJFS 10.1-2_12_art_Benrabah.qxd 2/21/07 8:35 PM Page 207

children of those who had adopted the new identity of Hebrew’.109 In Statistiques, 29,

1991, pp. 34–40;

Algeria, promoters of Arabization have not behaved accordingly by setting O. Khiar, ‘Villes —

an example for majority commitment to certain linguistic behaviours. As hypertrophie et

evidence, here is a telling anecdote. In June 1999, after reading this inégalités’, El Watan,

21–22 February,

author’s book,110 Gilbert Meynier, a French historian and professor at the 1992, p. 8.

University of Nancy (France), sent the former a letter saying, among other

75 G. Pervillé, ‘La

things, that in 1969 he was on vacation at a sea-side resort near Algiers. Reconquête de la

One afternoon, he found himself on a beach the anonymous neighbour of population

the then Minister of Education and his family. That Minister spent the algérienne’, in

G. Pervillé (ed.), Atlas

whole afternoon speaking to his wife and children exclusively in… French. de la Guerre d’Algérie,

The tragic irony is that this member of the Algerian elite was above all one Paris: Éditions

of the leading and most zealous champions of ‘Arabization at all costs’.111 Autrement, 2003,

p. 40.

This raises another issue which concerns ‘elite closure’ as a powerful

strategy for creating and/or maintaining social differentiation and 76 P. Vermeren,

Maghreb: La

inequalities.112 Such a strategy is characterized by the policy-makers’ Démocratie

implementation of a language policy (Arabization) for the majority of the Impossible?, Paris:

population in order to enable their own children educated in French to Librarie Arthème

Fayard, 2004,

have less competition for the well-paying jobs and prestigious career pp. 137–38.

options (modern business and technology) which require competence in

77 id., p. 139.

French.113 Thus, the military and socio-political leadership resort to

French lycées, preventing their offspring from enrolling at schools that 78 S. Miller, Experimental

Design and Statistics,

cater for the masses.114 In fact, immediately after independence, the ruling 2nd edn, London and

elite showed its preference for French schools over national ones.115 The New York: Methuen,

phenomenon of elite closure quite nicely illustrates a credibility gap 1984, p. 3; C.

Robson, Experiment,

between what the leaders say and what they actually do. (Their linguistic Design and Statistics in

behaviour mentioned above is also quite significant.) Psychology, 2nd edn,

Drawing on the foregoing discussion and from the perspective of lan- Harmondsworth:

Penguin Books,

guage economics, it seems that Algeria’s elites have failed to promote 1983, pp. 41–43.

Literary Arabic as an attractive ‘product’ to which a high ‘value’ would be

assigned on the Algerian ‘linguistic market’.116 The implementation of 79 C.F. Gallagher, ‘North

African Problems and

language policy requires from its promoters the need to persuade potential Prospects: Language

‘buyers’ of its benefits, social mobility, for example or a better socio-economic and Identity’,

life.117 Many a language planning researcher would concur with Denis pp. 132–33.

Ager’s statement that ‘language policy must demonstrate economic 80 R. Wardhaugh,

advantages if it is to stick. Without the bottom-up advantages, without an Languages in

Competition, Oxford:

identity in which all social categories can share, language policy will Basil Blackwell,

remain empty, symbolic gesture, a plaything for the intellectuals’.118 In 1987, pp. 7–8.

Algeria, ‘promoters’ of Arabization interfered with the basic rules of the 81 M. Bennoune,

game to the point of discrediting the whole policy. In her 2004 report on Education, Culture et

young Algerians’ daily life mentioned earlier, Florence Beaugé shows the développement en

Algérie. Bilan &

prestige attached to the French language and the uneasiness felt with perspectives du système

issues related to the policy of Arabization. éducatif. Algiers:

Marinoor-ENAG,

2000, p. 12; D.C.

[Le français] est en outre ‘un signe de richesse’, comme le dit Selim, 23 ans, Gordon, The French

‘la preuve qu’on appartient à un certain milieu’, ajoute Fatiha, 20 ans. C’est Language and National

aussi un certain snobisme, ‘les nouveaux riches, eux, ne connaissent que Identity, 1978,

p. 151; M. Harbi, La

l’arabe’. Se faire injurier en français est considéré comme ‘plutôt gentil’. En Guerre commence en

arabe, ‘c’est insultant’. Dans les quartiers populaires, en revanche, il est ‘mal Algérie, Brussels:

vu’ de s’exprimer en français. D’abord parce que cela ‘renvoie au passé’ Editions Complexes,

1984, p. 79; A.A.

[l’époque coloniale], ensuite parce que ‘cela donne des complexes à certains’,

Language maintenance and spread: French in Algeria 207

IJFS 10.1-2_12_art_Benrabah.qxd 2/21/07 8:35 PM Page 208

Heggoy, ‘Colonial souligne Selim, touchant du doigt une question des plus sensibles en Algérie:

Education in Algeria: celle de l’arabisation de l’enseignement.119

Assimilation and

Reaction’, in P.G.

Altbach and G. Kelly Ernest Gellner was perceptive enough to write in the early 1970s that the

(eds.), Education and North African knows in his heart not only that God speaks Arabic, but also

the Colonial

Experience, New that modernity speaks French.120 After four decades of an assertive policy

Brunswick, N.J.: of Arabization, Gellner’s claims still hold true for Algerians at least. The

Transaction Books, results of the large survey conducted in April-May 2004 show that

1984, pp. 111;

M. Lacheraf, L’Algérie, secondary school students clearly associate Literary Arabic with religion

nation et société, and French with modernity.121 In the Algerian linguistic market, French

Algiers: SNED, 1978, has a ‘high’ value and carries a prestigious image. Given the claim that

p. 313.

favourable attitudes towards a language (or its survival) serve its mainte-

82 A. Djeghloul, Huit nance, respondents in this survey were also asked to say whether they

études sur l’Algérie,

Algiers: ENAL, 1986, believed that French would disappear in Algeria in the future or not.

pp. 39–40. More than three quarters of a total of 1,042 respondents believed in the

83 Quoted in C.R. future maintenance of French in their country.122 Another way of assessing

Ageron, Les Algériens the future of French in Algeria is by looking at its position in relation to the

musulmans et la English language. Other answers given by Algerian schoolchildren in that

France. Tome 1, Paris:

Presses Universitaires survey (see Table 7) show that a significant proportion of respondents

de France, 1968, rejected the idea of substituting English for French. Rather, they prefer addi-

p. 339. tive instead of subtractive multilingualism. This attitude has certainly been

84 D.C. Gordon, The misrepresented by Algeria’s leaders in the form of a conflict between the

Passing of French two European languages.123 What is more, the valued image associated

Algeria, p. 196.

with French in Algeria overlooks reality and the fact that English is, at the

85 Ambassade d’Algérie moment, the major international language of science and technology. Such

en France, Algérie. Un

guide pratique offert behaviour supports those who argue that image and prestige are not neces-

par l’ambassade sarily grounded in reality. Schoolchildren in our large survey also reject the

d’Algérie en France. replacement of French by English as the major foreign language and refuse

Paris: Corporate,

2002, p. 3; the idea of having English used as the medium of instruction in scientific

M. Bennoune, disciplines (see Table 7). In fact, for Statement 1, the majority do not want

Education, Culture et French replaced by English: 49.3% against 31.7% (note here the high per-

développement en

Algérie. Bilan & centage, 18.5%, of undecided informants). But for Statement 2 a clear

perspectives du système majority prefers French (61.5% for categories 4 and 5).

éducatif. Algiers:

Marinoor-ENAG,

2000, p. 225.

Conclusion

This article has focused on factors affecting, in one way or another, the

86 M. Bennoune,

Education, Culture et

maintenance and spread of French in Algeria. Four reasons have proved to

développement en be significant correlates of language maintenance even though other

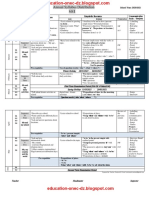

1 2 3 4 5

Agree Agree Neither Disagree Disagree

completely agree nor completely

Statement disagree

1) I would like French to be 13.9% 17.8% 18.5% 26.2% 23.1%

replaced by English in Algeria. (146) (187) (194) (275) (243)

2) Scientific subjects should be 5.1% 15.2% 16.8% 33.2% 28.3%

taught in English. (54) (160) (177) (349) (297)

Table 7: Language attitudes: French vs. English in Algeria.

208 Mohamed Benrabah

IJFS 10.1-2_12_art_Benrabah.qxd 2/21/07 8:35 PM Page 209

possible predictors are not to be discarded. First, changes in the economic Algérie. Bilan &

perspectives du système

sphere have evolved from a period of ‘economic nationalism’ associated éducatif, Algiers:

with an exclusively Arabo-Islamic identity to a free market era with political Marinoor-ENAG,

liberalization accompanied by demands of multiple identities with multi- p. 225.

lingualism as their carrier. Second, the formidable high birth rate and the 87 S.E. Belabes, ‘La ren-

development of urbanization in post-independent Algeria have led to a trée scolaire prévue

reversal in attitudes towards French among the new generations for le 11 septembre.

Moins d’élèves à

whom the ‘bitterness’ towards the ex-colonial language has diminished. l’école’, El Watan, 1

Third, with the help of institutions such as the educational system, inde- September, 2004; D.

pendent Algeria has allowed French to be maintained and even spread to Kourta, ‘Réforme de

l’école.

the point of turning the country into the second francophone community Premiers change-

in the world after France. Fourth, the satisfaction in the ‘demands of ments’, El Watan, 29

recognition’, the Algerian elite’s linguistic practices and their inability to September, 2003.

turn Literary Arabic into a ‘useful’ language and their disregard for the 88 Ambassade d’Algérie

population’s needs and linguistic representations have all helped to give a en France, Algérie. Un

guide pratique offert

high social status (prestige) to French. Most of the above factors turned par l’ambassade

out to be powerful predictors for measuring language attitudes (towards d’Algérie en France.

French) among Algerian senior high school students who participated in a Paris: Corporate,

2002, p. 3.

large survey in April-May 2004.

Implications of such language maintenance are important for lan- 89 Source: M.

Bennoune, Education,

guage policy in Algeria. Arabization, inspired by the outdated nationalistic Culture et

European model based on a monolingual state and linguistic homogeniza- développement en

tion, has shown its limits. It has even proved to be self-destructive and Algérie. Bilan &

perspectives du système

dangerous to the process of nation-building, as the civil war of the 1990s éducatif, Algiers:

clearly showed. That was partly due to linguistic and cultural conflicts Marinoor-ENAG,

generated by Arabization and described by some authors as ‘cultural civil 2000, p. 326.

war’ or linguistic ‘intellectual cleansing’.124 Lessons from the mainte- 90 B. Stora, Histoire de

nance of French should be drawn by Algerian planners. They should l’Algérie depuis

l’indépendance

implement a language policy grounded on additive multilingualism the (1962–1988), p. 73.

advantages of which (cognitive, academic, economic, etc.) have been

91 L. Kadi, ‘La politique