Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Lord He in

Lord He in

Uploaded by

Claire F.Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Lord He in

Lord He in

Uploaded by

Claire F.Copyright:

Available Formats

time had come when a man of genius could hope to make an independent living.

Once intellectuals began to dispense with the protection of the nobility, the French

Revolution could not be far off.

Piranesi's thirties were his years of truculence. As soon as he had

published the

Roman Antiquities, and even while he was rebuking Lord Charlemont, he started a

gigantic polemical work called The Magnificence and Architecture of the Romans. He

was angered by two attacks on ancient Rome from London and Paris. In 1755 a silly

anonymous article in a London newspaper called the Romans "a gang of mere

plunderers sprung from them who had been, but a little while before their con

quest of Greece, naked thieves and runaway slaves." Then in 1758, after Piranesi

had prepared to answer this article, the real threat came from another quarter

when David Leroy published the first book ever devoted to Greek architecture,

Les Ruines des plus beaux Monuments de la Grèce. Leroy claimed that the Greeks had in

vented an architecture which the Romans had then adapted. It astonishes us today

to find that such an opinion ever caused astonishment. Europe knew Roman archi

tecture well, but had no idea of the Greek, for few cultivated Europeans had pene

trated the iron curtain of brigands and suspicious Turkish officials who made a

visit to Greek ruins next to impossible.

On the other hand, Rome had dominated the West for over two thousand years

until Romans, and indeed all Italians, had come to feel that nothing could have

originated anywhere else. Not only Piranesi's uncle Matteo, but all his Italian con

temporaries believed that the Etruscans, an older and more intelligent race than

the Greeks, had handed on their inventions to the Romans. After the Romans con

quered Greece, the Greeks had picked up a whimsical facility from the pioneer la

bors of ancient Italy. When Piranesi was a boy certain Frenchmen and Englishmen

began to suspect that the Greeks had invented more art than the Italians allowed.

The French and English attacks that roused Piranesi were just the beginning of one

of the great revaluations of modern time. This revaluation struck with force in

1764 when Winckelmann's History of Ancient Art announced the vision (later a

dogma) of the Greeks as Arcadians dwelling in ideal beauty and noble calm. Winck-

elmann allowed merit to Piranesi's etchings but naturally spurned his theories. In

the narrow intellectual circles of the eighteenth-century Rome the two men, who

were almost of the same age, avoided each other for thirteen years like wrestlers too

wary to grapple— one the lofty rhapsodist of Greece, the other the heavyweight

champion of Rome. Today both theorists seem equally arbitrary.

When Piranesi saw the threat to his faith he threw everything into the defense.

After five years of work he had etched only thirty-eight plates of great Roman build

18

You might also like

- BRKSEC 3699 ReferenceDocument411 pagesBRKSEC 3699 ReferencePhyo Min TunNo ratings yet

- CH 6 Sec 5 - Rome and The Roots of Western Civilization PDFDocument6 pagesCH 6 Sec 5 - Rome and The Roots of Western Civilization PDFJ. NievesNo ratings yet

- Seeing Europe with Famous Authors, Volume 7 Italy, Sicily, and Greece (Part One)From EverandSeeing Europe with Famous Authors, Volume 7 Italy, Sicily, and Greece (Part One)No ratings yet

- AQA Power and Conflict Wider Reading BookletDocument16 pagesAQA Power and Conflict Wider Reading BookletZainab JassimNo ratings yet

- Course 2 The Romantic Period 1780-1830Document4 pagesCourse 2 The Romantic Period 1780-1830Raducan Irina FlorinaNo ratings yet

- The Evolution of an Empire: A Brief Historical Sketch of GermanyFrom EverandThe Evolution of an Empire: A Brief Historical Sketch of GermanyNo ratings yet

- Same Tractor Krypton 80-90-95 100 105 Parts CatalogDocument22 pagesSame Tractor Krypton 80-90-95 100 105 Parts Catalogmirandajuarezmd241202kxn100% (128)

- Romanity, Rome, RomaniaDocument14 pagesRomanity, Rome, RomaniaMario KorraNo ratings yet

- Roman Britain's Missing Legion: What Really Happened to IX Hispana?From EverandRoman Britain's Missing Legion: What Really Happened to IX Hispana?Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- The French of Revolution of 1789 and The European Revolts of 1848 Form A Near Although Not Completely Accurate, Boundary For Romanticism.Document32 pagesThe French of Revolution of 1789 and The European Revolts of 1848 Form A Near Although Not Completely Accurate, Boundary For Romanticism.Julian Roi DaquizNo ratings yet

- He in The UntilDocument1 pageHe in The UntilJoni C.No ratings yet

- A Brief History of RomeDocument3 pagesA Brief History of RomeClaireAngelaNo ratings yet

- Rome 5Document3 pagesRome 5EINSTEINNo ratings yet

- Seeing Europe With Famous Authors, Volume 7italy, Sicily, and Greece (Part One) by VariousDocument102 pagesSeeing Europe With Famous Authors, Volume 7italy, Sicily, and Greece (Part One) by VariousGutenberg.org100% (1)

- Hellenism, Alexandrianism, and Roman Enlightenment: Magda El - NowieemyDocument13 pagesHellenism, Alexandrianism, and Roman Enlightenment: Magda El - NowieemyAdrian VladuNo ratings yet

- Roderick Beaton Reviews Adamantios Korais and The European Enlightenment in The TLSDocument4 pagesRoderick Beaton Reviews Adamantios Korais and The European Enlightenment in The TLSlavraki_21No ratings yet

- Unit 4. The 18th Century1Document16 pagesUnit 4. The 18th Century1Minh ChauNo ratings yet

- A Businessman and Adventurer: Much More Appreciated in BritainDocument2 pagesA Businessman and Adventurer: Much More Appreciated in BritainVictoria FedoseevaNo ratings yet

- Princes of the Renaissance: The Hidden Power Behind an Artistic RevolutionFrom EverandPrinces of the Renaissance: The Hidden Power Behind an Artistic RevolutionNo ratings yet

- 3 Roman Empire PDFDocument66 pages3 Roman Empire PDFemmantse100% (1)

- TRANSCRIPT Prof Gino Raymond PDFDocument2 pagesTRANSCRIPT Prof Gino Raymond PDFNataša ZlatovićNo ratings yet

- Legacy of Rome TextDocument10 pagesLegacy of Rome Textapi-233464494No ratings yet

- Summary of After 1177 B.C. by Eric H. Cline: The Survival of CivilizationsFrom EverandSummary of After 1177 B.C. by Eric H. Cline: The Survival of CivilizationsNo ratings yet

- One God of The Jews This PendantDocument7 pagesOne God of The Jews This PendantAlexandra AndreiNo ratings yet

- Roman CultureDocument3 pagesRoman CultureKamalito El CaballeroNo ratings yet

- TextbookromeinfluencesDocument6 pagesTextbookromeinfluencesapi-235382759No ratings yet

- The Big Book of Santa's Christmas Tales: 500+ Novels, Stories, Poems, Carols & LegendsFrom EverandThe Big Book of Santa's Christmas Tales: 500+ Novels, Stories, Poems, Carols & LegendsNo ratings yet

- Possess the Air: Love, Heroism, and the Battle for the Soul of Mussolini's RomeFrom EverandPossess the Air: Love, Heroism, and the Battle for the Soul of Mussolini's RomeNo ratings yet

- Titientes One On The Quirinal Hill, Backed by The Luceres Living in The Nearby WoodsDocument3 pagesTitientes One On The Quirinal Hill, Backed by The Luceres Living in The Nearby WoodsMerryshyra MisagalNo ratings yet

- Seeing Europe With Famous Authors, Volume 3france and The Netherlands, Part 1 by VariousDocument102 pagesSeeing Europe With Famous Authors, Volume 3france and The Netherlands, Part 1 by VariousGutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Celebrated Crimes 'The Cenci', 'The Countess of St Geran' and 'Karl Ludwig Sand'From EverandCelebrated Crimes 'The Cenci', 'The Countess of St Geran' and 'Karl Ludwig Sand'No ratings yet

- Ancient Rome, by Mary Agnes Hamilton 1Document78 pagesAncient Rome, by Mary Agnes Hamilton 1kashanircNo ratings yet

- Ad Britannia Ii: First Century Roman BritanniaFrom EverandAd Britannia Ii: First Century Roman BritanniaNo ratings yet

- THE COMTE DE ST. GERMAIN The Secret of kings: A MonographFrom EverandTHE COMTE DE ST. GERMAIN The Secret of kings: A MonographNo ratings yet

- Examples of Literary ClassicismDocument34 pagesExamples of Literary ClassicismHasan TariqNo ratings yet

- Delphi Complete Works of Velleius Paterculus (Illustrated)From EverandDelphi Complete Works of Velleius Paterculus (Illustrated)No ratings yet

- Troy: Yesterday's Lost City: Aura Ively This Paper Was Presented at The 2006 Regional Phi Alpha Theta ConferenceDocument10 pagesTroy: Yesterday's Lost City: Aura Ively This Paper Was Presented at The 2006 Regional Phi Alpha Theta ConferenceGabriel JacaNo ratings yet

- Ruins As A Mental ConstructDocument14 pagesRuins As A Mental Construct李雨恒No ratings yet

- And in NoDocument1 pageAnd in NoJoni C.No ratings yet

- And in NoDocument1 pageAnd in NoClaire F.No ratings yet

- Main Events Publications: Xiv. ADocument1 pageMain Events Publications: Xiv. AClaire F.No ratings yet

- Writing SitesDocument1 pageWriting SitesClaire F.No ratings yet

- His He ApolloDocument1 pageHis He ApolloClaire F.No ratings yet

- Piranesi by A. Hyatt MayorDocument194 pagesPiranesi by A. Hyatt MayorClaire F.No ratings yet

- The Au in Built Until ThusDocument1 pageThe Au in Built Until ThusClaire F.No ratings yet

- II Xiii: in Tomati Di JanDocument1 pageII Xiii: in Tomati Di JanClaire F.No ratings yet

- Then Print: A A So 1860'sDocument1 pageThen Print: A A So 1860'sClaire F.No ratings yet

- With It: As A ADocument1 pageWith It: As A AClaire F.No ratings yet

- Ruin in Distilling The in No: TivoliDocument1 pageRuin in Distilling The in No: TivoliClaire F.No ratings yet

- Latin Like The His Like MiddleDocument1 pageLatin Like The His Like MiddleClaire F.No ratings yet

- Architetto: Veneziano. ItDocument1 pageArchitetto: Veneziano. ItClaire F.No ratings yet

- Build: Uses As AsDocument1 pageBuild: Uses As AsClaire F.No ratings yet

- With It: As A ADocument1 pageWith It: As A AClaire F.No ratings yet

- PiranesiDocument80 pagesPiranesiClaire F.No ratings yet

- Building: TheirDocument1 pageBuilding: TheirClaire F.No ratings yet

- In inDocument1 pageIn inClaire F.No ratings yet

- Adri Pulling ItDocument1 pageAdri Pulling ItClaire F.No ratings yet

- And in NoDocument1 pageAnd in NoClaire F.No ratings yet

- He It in in in inDocument1 pageHe It in in in inClaire F.No ratings yet

- His in His of HisDocument1 pageHis in His of HisClaire F.No ratings yet

- What Others: Have SaidDocument1 pageWhat Others: Have SaidClaire F.No ratings yet

- Giovanni Piranesi: HyattDocument1 pageGiovanni Piranesi: HyattClaire F.No ratings yet

- In in Their: ET Joan Domovenetiis Sigillari ArchitectiDocument1 pageIn in Their: ET Joan Domovenetiis Sigillari ArchitectiClaire F.No ratings yet

- Mini Dictionary of Irish SlangDocument2 pagesMini Dictionary of Irish SlangClaire F.No ratings yet

- So-Called Villa at Tivoli. Full Sized Detail, About: 69 of Maecenas 1764Document20 pagesSo-Called Villa at Tivoli. Full Sized Detail, About: 69 of Maecenas 1764Claire F.No ratings yet

- Altar, Santa Maria Aventina, Modeled Tommaso RighiDocument20 pagesAltar, Santa Maria Aventina, Modeled Tommaso RighiClaire F.No ratings yet

- Thesis Project: "Orphanage Cum Old Age Home "Document67 pagesThesis Project: "Orphanage Cum Old Age Home "moon100% (1)

- Hammerdb HTML Interface: Introduction To HTML TestingDocument3 pagesHammerdb HTML Interface: Introduction To HTML Testingabc6309982No ratings yet

- Operating System: Deployment Guide Automating Windows NT SetupDocument129 pagesOperating System: Deployment Guide Automating Windows NT SetupmmihmNo ratings yet

- Sap Basis With Hana Consultant Ramana Reddy. M Gmail: Mobile: +91-8970335642Document3 pagesSap Basis With Hana Consultant Ramana Reddy. M Gmail: Mobile: +91-8970335642chinna chinnaNo ratings yet

- Design Guidelines For Campus Planing - 1Document9 pagesDesign Guidelines For Campus Planing - 1Inara SbNo ratings yet

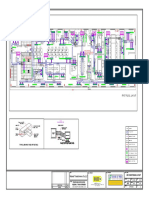

- HVAC DWG SampleDocument1 pageHVAC DWG Sampleimtz2013No ratings yet

- ACRONIME CalculatoareDocument260 pagesACRONIME CalculatoarecgabrielleNo ratings yet

- Automatic Policyd Zcs8.5Document8 pagesAutomatic Policyd Zcs8.5francNo ratings yet

- Design of ConcreteDocument3 pagesDesign of Concretesachin balyanNo ratings yet

- Eci Catalogue 2011 WebDocument136 pagesEci Catalogue 2011 WebECI Lighting DublinNo ratings yet

- Improvements To Shankarpally To Marpally Road From Km.0/0 To 4/0 in Ranga Reddy District. Detailed Cum Abstract Estimate Name of WorkDocument34 pagesImprovements To Shankarpally To Marpally Road From Km.0/0 To 4/0 in Ranga Reddy District. Detailed Cum Abstract Estimate Name of Worksandeep bandaruNo ratings yet

- Taschen Magazine April 2014Document54 pagesTaschen Magazine April 2014Simone Odino100% (10)

- Sika Loadflex Polyurea Product Data 322187Document2 pagesSika Loadflex Polyurea Product Data 322187quaeNo ratings yet

- Blockchain Technology, Bitcoin, and Ethereum: A Brief OverviewDocument8 pagesBlockchain Technology, Bitcoin, and Ethereum: A Brief OverviewEddyNo ratings yet

- 5-MPAK MU16047 enDocument8 pages5-MPAK MU16047 enYulianis ZuñigaNo ratings yet

- DNSDocument157 pagesDNSArmando Velazquez SanchezNo ratings yet

- SCCHC 2012 Pluckemin RPT 2 Surface CollectionDocument44 pagesSCCHC 2012 Pluckemin RPT 2 Surface Collectionjvanderveerhouse100% (1)

- What Is The Difference Between Development Length and Anchorage LengthDocument5 pagesWhat Is The Difference Between Development Length and Anchorage LengthankitNo ratings yet

- Jtag PDFDocument22 pagesJtag PDFamitwangoo0% (1)

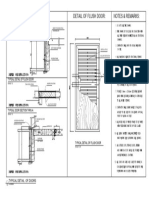

- Typical Detail of DoorDocument1 pageTypical Detail of DoorGlyza Tercero SerraNo ratings yet

- Statnamic Load Test ASTM D7383 - 551.970001TZDocument4 pagesStatnamic Load Test ASTM D7383 - 551.970001TZsenhuNo ratings yet

- Pert CPMDocument8 pagesPert CPMnurNo ratings yet

- 26Document43 pages26altaminNo ratings yet

- Ancon 25-14 Restraint SystemDocument4 pagesAncon 25-14 Restraint SystemmcbluedNo ratings yet

- Sourabh Gupta Profile - 2020 PDFDocument12 pagesSourabh Gupta Profile - 2020 PDFPrashant MallickNo ratings yet

- Key Plan Typical Floor Plan Lift M/C. Room LVL.: Dimensional DetailsDocument1 pageKey Plan Typical Floor Plan Lift M/C. Room LVL.: Dimensional DetailsVinay KatariyaNo ratings yet

- Tribhuvan University Institute of Engineering Purwanchal Campus Dharan-8, Sunsari, NepalDocument6 pagesTribhuvan University Institute of Engineering Purwanchal Campus Dharan-8, Sunsari, NepalPrajina ShresthaNo ratings yet

- ACE OverviewDocument2 pagesACE OverviewtonynyNo ratings yet

- 1992-08 The Computer Paper - BC Edition PDFDocument96 pages1992-08 The Computer Paper - BC Edition PDFthecomputerpaper100% (1)