Professional Documents

Culture Documents

New Treatment Modality For Maxillary Hypoplasia in Cleft Patients

New Treatment Modality For Maxillary Hypoplasia in Cleft Patients

Uploaded by

KaranPadhaCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Mechanistic Insights in Cardiorenal Syndrome: Published August 23, 2022Document13 pagesMechanistic Insights in Cardiorenal Syndrome: Published August 23, 2022Raul Fernando100% (1)

- Test Bank The Art of Public Speaking 11th Edition by Stephen LucasDocument26 pagesTest Bank The Art of Public Speaking 11th Edition by Stephen Lucasbachababy0% (3)

- MCQ's Blood BankDocument74 pagesMCQ's Blood BankAlireza Goodazri100% (2)

- 10 1093@ejo@cjv053Document11 pages10 1093@ejo@cjv053Drazza TagaldinNo ratings yet

- Camouflage Treatment of Skeletal Class III Malocclusion With Asymmetry Using A Bone-Borne Rapid Maxillary ExpanderDocument13 pagesCamouflage Treatment of Skeletal Class III Malocclusion With Asymmetry Using A Bone-Borne Rapid Maxillary ExpanderClinica Dental AdvanceNo ratings yet

- Bong 2011 PDFDocument14 pagesBong 2011 PDFkarenchavezalvanNo ratings yet

- Nonsurgical Correction of A Class III Malocclusion in An Adult by Miniscrew-Assisted Mandibular Dentition DistalizationDocument11 pagesNonsurgical Correction of A Class III Malocclusion in An Adult by Miniscrew-Assisted Mandibular Dentition DistalizationNeycer Catpo NuncevayNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2666430522000036 MainDocument12 pages1 s2.0 S2666430522000036 MainDANTE DELEGUERYNo ratings yet

- Benedict Wimes, Mascara FacialDocument8 pagesBenedict Wimes, Mascara FacialjamilistccNo ratings yet

- Artículo DentalDocument6 pagesArtículo DentalAngélicaLujánNo ratings yet

- Severe Class II Division 1 MalocclusionDocument14 pagesSevere Class II Division 1 MalocclusionCARMEN ROSA AREVALO ROLDANNo ratings yet

- Xu 2014Document10 pagesXu 2014Marcos Gómez SosaNo ratings yet

- Correction of Late Adolescent Skeletal Class III Using The Alt-RAMEC Protocol and Skeletal AnchorageDocument11 pagesCorrection of Late Adolescent Skeletal Class III Using The Alt-RAMEC Protocol and Skeletal AnchoragePorchiddioNo ratings yet

- Severe Anterior Open Bite With Mandibular Retrusion Treated With Multiloop Edgewise Archwires and Microimplant Anchorage ComplementedDocument10 pagesSevere Anterior Open Bite With Mandibular Retrusion Treated With Multiloop Edgewise Archwires and Microimplant Anchorage ComplementedLedir Luciana Henley de AndradeNo ratings yet

- (23350245 - Balkan Journal of Dental Medicine) Treatment of Maxillary Retrusion-Face Mask With or Without RPEDocument5 pages(23350245 - Balkan Journal of Dental Medicine) Treatment of Maxillary Retrusion-Face Mask With or Without RPEmalifaragNo ratings yet

- Openbite MIA AJODODocument10 pagesOpenbite MIA AJODOscribdlptNo ratings yet

- Ajodo 3Document10 pagesAjodo 3ayisNo ratings yet

- Camouflage Treatment of Skeletal Class III Malocclusion With Multiloop Edgewise Arch Wire and Modified Class III Elastics by Maxillary Mini-Implant AnchorageDocument11 pagesCamouflage Treatment of Skeletal Class III Malocclusion With Multiloop Edgewise Arch Wire and Modified Class III Elastics by Maxillary Mini-Implant AnchorageValery V JaureguiNo ratings yet

- Angle Orthod. 2012 82 5 846-52Document7 pagesAngle Orthod. 2012 82 5 846-52brookortontiaNo ratings yet

- VR Mesh 5Document6 pagesVR Mesh 5Zaid DewachiNo ratings yet

- Maxillary Arch Distalization Using Interradicular Miniscrews and The Lever-Arm ApplianceDocument8 pagesMaxillary Arch Distalization Using Interradicular Miniscrews and The Lever-Arm ApplianceJuan Carlos CárcamoNo ratings yet

- Early Management of Class III Malocclusion in Mixed DentitionDocument4 pagesEarly Management of Class III Malocclusion in Mixed DentitionMariana SantosNo ratings yet

- Posterior Crossbite With Mandibular Asymmetry Treated With Lingual Appliances, Maxillary Skeletal Expanders, and Alveolar Bone MiniscrewsDocument21 pagesPosterior Crossbite With Mandibular Asymmetry Treated With Lingual Appliances, Maxillary Skeletal Expanders, and Alveolar Bone MiniscrewsJuliana ÁlvarezNo ratings yet

- Ishihara 2013Document12 pagesIshihara 2013Mirek SzNo ratings yet

- Openbite CamouflageDocument8 pagesOpenbite CamouflageRakesh RaveendranNo ratings yet

- Dentofacial Effects of Two Facemask Therapies For Maxillary Protraction Miniscrew Implants Versus Rapid Maxillary ExpandersDocument9 pagesDentofacial Effects of Two Facemask Therapies For Maxillary Protraction Miniscrew Implants Versus Rapid Maxillary ExpandersMariana SantosNo ratings yet

- 2020 Article 265Document7 pages2020 Article 265Fabian BarretoNo ratings yet

- APOSTrendsOrthod 2016 6 4 228 186439 PDFDocument5 pagesAPOSTrendsOrthod 2016 6 4 228 186439 PDFDr sneha HoshingNo ratings yet

- Treatment of An Anterior Open Bite, Bimaxillary Protrusion and Mesiocclusion by The Extraction of Premolars and The Use of Clear AlignersDocument14 pagesTreatment of An Anterior Open Bite, Bimaxillary Protrusion and Mesiocclusion by The Extraction of Premolars and The Use of Clear AlignersAstrid HutabaratNo ratings yet

- Angle Orthod. 2014 84 5 919-30Document12 pagesAngle Orthod. 2014 84 5 919-30brookortontiaNo ratings yet

- Effects of Facemask Treatment Anchored With Miniplates After Alternate Rapid Maxillary Expansions and Constrictions A Pilot StudyDocument8 pagesEffects of Facemask Treatment Anchored With Miniplates After Alternate Rapid Maxillary Expansions and Constrictions A Pilot StudyMariana SantosNo ratings yet

- Absolute Anchorage With Universal T-Loop Mechanics For Severe Deepbite and Maxillary Anterior Protrusion and Its 10-Year StabilityDocument12 pagesAbsolute Anchorage With Universal T-Loop Mechanics For Severe Deepbite and Maxillary Anterior Protrusion and Its 10-Year StabilitysmritiNo ratings yet

- Jung 2018Document14 pagesJung 2018Anonymous ckVKx4njgNo ratings yet

- Multiloop Edgewise Arch-Wire Technique For Skeleta PDFDocument4 pagesMultiloop Edgewise Arch-Wire Technique For Skeleta PDFanhca4519No ratings yet

- 404 AlamDocument5 pages404 AlamEva ApriyaniNo ratings yet

- 2176 9451 Dpjo 24 05 52Document8 pages2176 9451 Dpjo 24 05 52Crisu CrisuuNo ratings yet

- Art Maloclusiones CepilloDocument5 pagesArt Maloclusiones Cepillopaola tarazonaNo ratings yet

- Vertical-Dimension Control During En-MasseDocument13 pagesVertical-Dimension Control During En-MasseLisbethNo ratings yet

- Space Closure in The Maxillary Posterior Area Through The Maxillary SinusDocument8 pagesSpace Closure in The Maxillary Posterior Area Through The Maxillary SinusArsenie TataruNo ratings yet

- +distraction Osteogenesis For The Cleftlip and PalateDocument12 pages+distraction Osteogenesis For The Cleftlip and PalategrisguzlNo ratings yet

- Class II Bimaxillary ProtrusionDocument13 pagesClass II Bimaxillary ProtrusionPrasne SriNo ratings yet

- Daimaruya 2010Document7 pagesDaimaruya 2010KATERIN TTITO MAMANINo ratings yet

- EtiologyDocument3 pagesEtiologyMoe AtraNo ratings yet

- Lee 2019Document7 pagesLee 2019Monojit DuttaNo ratings yet

- 7 Articulo Bone-Anchored Maxillary Protraction in A Patient With Complete Cleft Lip and Palate: A Case ReportDocument8 pages7 Articulo Bone-Anchored Maxillary Protraction in A Patient With Complete Cleft Lip and Palate: A Case ReportErika NuñezNo ratings yet

- C-Orthodontic Microimplant For Distalization of Mandibular Dentition in Class III CorrectionDocument9 pagesC-Orthodontic Microimplant For Distalization of Mandibular Dentition in Class III CorrectionNeeraj AroraNo ratings yet

- Absolute Anchorage With Universal T-Loop Mechanics For Severe Deepbite and Maxillary Anterior Protrusion and Its 10-Year StabilityDocument12 pagesAbsolute Anchorage With Universal T-Loop Mechanics For Severe Deepbite and Maxillary Anterior Protrusion and Its 10-Year StabilityThang Nguyen TienNo ratings yet

- Articulo 3Document8 pagesArticulo 3Carolina SepulvedaNo ratings yet

- Angle 2007 Ene 155-166Document12 pagesAngle 2007 Ene 155-166André MéndezNo ratings yet

- SUB158101Document4 pagesSUB158101chirag sahgalNo ratings yet

- 2215 3411 Odovtos 20 02 31Document7 pages2215 3411 Odovtos 20 02 31habeebNo ratings yet

- Use of Palatal Miniscrew Anchorage and Lingual Multi-Bracket Appliances To Enhance Efficiency of Molar Scissors-Bite CorrectionDocument8 pagesUse of Palatal Miniscrew Anchorage and Lingual Multi-Bracket Appliances To Enhance Efficiency of Molar Scissors-Bite CorrectionTriyunda PermatasariNo ratings yet

- Maxillary Protraction / Orthodontic Courses by Indian Dental AcademyDocument86 pagesMaxillary Protraction / Orthodontic Courses by Indian Dental Academyindian dental academyNo ratings yet

- Craniofacial Changes in Patients With Class III Malocclusion Treated With The Rampa SystemDocument7 pagesCraniofacial Changes in Patients With Class III Malocclusion Treated With The Rampa Systemapi-192260741100% (1)

- Early Treatment Protocol For Skeletal Class III MalocclusionDocument7 pagesEarly Treatment Protocol For Skeletal Class III MalocclusionJavier Farias VeraNo ratings yet

- Arvystas 1998Document4 pagesArvystas 1998Саша АптреевNo ratings yet

- 2011-Orthopedic Treatment of Class III Malocclusion With Rapid Maxillary Expansion Combined With A Face Mask A Cephalometric Assessment of Craniofacial Growth PatternsDocument7 pages2011-Orthopedic Treatment of Class III Malocclusion With Rapid Maxillary Expansion Combined With A Face Mask A Cephalometric Assessment of Craniofacial Growth PatternsMariana SantosNo ratings yet

- Kaya 2011Document8 pagesKaya 2011ortodoncia 2022No ratings yet

- Orthodontic Treatmentafter High Condylectomyin Patientswith Unilateral Condylar HyperplasiaDocument9 pagesOrthodontic Treatmentafter High Condylectomyin Patientswith Unilateral Condylar HyperplasiaOrtodoncia UNAL 2020No ratings yet

- Miniscrew-anchored maxillary protraction in growing Class III patientsDocument17 pagesMiniscrew-anchored maxillary protraction in growing Class III patientscirurgicafontellesNo ratings yet

- TRATRAMIENTO DE CLASE II DIVISION 2 CON ExTREMA PROFUNDIDADDocument13 pagesTRATRAMIENTO DE CLASE II DIVISION 2 CON ExTREMA PROFUNDIDADMelisa GuerraNo ratings yet

- Orthodontic Management of A Horizontally Impacted Maxillary Incisor in An Adolescent PatientDocument11 pagesOrthodontic Management of A Horizontally Impacted Maxillary Incisor in An Adolescent PatientMarcos Gómez SosaNo ratings yet

- Bernstein 1984Document7 pagesBernstein 1984KaranPadhaNo ratings yet

- Brennan 2001Document8 pagesBrennan 2001KaranPadhaNo ratings yet

- Faciomaxillary Fractures in North India A Statistical Analysis and Review of ManagementDocument5 pagesFaciomaxillary Fractures in North India A Statistical Analysis and Review of ManagementKaranPadhaNo ratings yet

- Significance: Clinical of The Anastomotic Branches FacialDocument4 pagesSignificance: Clinical of The Anastomotic Branches FacialKaranPadhaNo ratings yet

- Facial Nerve Function After Partial Superficial Parotidectomy: An 11-Year Review (1987-1997)Document4 pagesFacial Nerve Function After Partial Superficial Parotidectomy: An 11-Year Review (1987-1997)KaranPadhaNo ratings yet

- Bainton 1990Document2 pagesBainton 1990KaranPadhaNo ratings yet

- Bloodborne The Old Hunters Collectors Edition Guide 6alw0hoDocument2 pagesBloodborne The Old Hunters Collectors Edition Guide 6alw0hoKaranPadhaNo ratings yet

- Tech Connect Retail Private Limited,: Grand TotalDocument1 pageTech Connect Retail Private Limited,: Grand TotalKaranPadhaNo ratings yet

- Circulatory MatchDocument2 pagesCirculatory MatchJinky AydallaNo ratings yet

- Esthetic Analysis Checklist: 8 Steps For Systematic Treatment PlanningDocument1 pageEsthetic Analysis Checklist: 8 Steps For Systematic Treatment PlanningMarcus EskilssonNo ratings yet

- Burning Mouth SyndromeDocument28 pagesBurning Mouth SyndromeMelissa KanggrianiNo ratings yet

- Neuroscience ABCsDocument261 pagesNeuroscience ABCsxxx xxx100% (2)

- Prometric Dental Exam Questions For: DHA Nov 2019Document5 pagesPrometric Dental Exam Questions For: DHA Nov 2019Aniket PotnisNo ratings yet

- 1901: Three Main Blood Groups DiscoveredDocument4 pages1901: Three Main Blood Groups Discoveredjohn dave cuevasNo ratings yet

- Biology: Topic - Endocrine System Class-VIII Board - ICSEDocument3 pagesBiology: Topic - Endocrine System Class-VIII Board - ICSEItu DeyNo ratings yet

- Pre Transfusion TestingDocument57 pagesPre Transfusion TestingDominic Bernardo100% (4)

- 2nd Quarter Summative Test No.1 in Science 6Document1 page2nd Quarter Summative Test No.1 in Science 6Marilou Kimayong100% (9)

- Coffee Dental StainsDocument2 pagesCoffee Dental StainsL SalemNo ratings yet

- Laporan Gigi Bulan JuliDocument765 pagesLaporan Gigi Bulan Julimaurin's diaryNo ratings yet

- Peripheral Nervous SystemDocument39 pagesPeripheral Nervous SystemHengky HanggaraNo ratings yet

- Posterior Abdominal WallDocument25 pagesPosterior Abdominal Wallapi-19916399No ratings yet

- Ala 3Document30 pagesAla 3Alaz NellyNo ratings yet

- Anexo-Unit1-Body SystemsDocument5 pagesAnexo-Unit1-Body SystemsPau GuauNo ratings yet

- Art 3Document16 pagesArt 3Carol LozanoNo ratings yet

- Circulation Blood Components Worksheet 2021Document4 pagesCirculation Blood Components Worksheet 2021api-523306558No ratings yet

- Difference Between Complete and Incomplete AntibodiesDocument4 pagesDifference Between Complete and Incomplete AntibodiesAnindita Abriani PiradeNo ratings yet

- Homologous Blood Trasfusion Practice ShortsDocument23 pagesHomologous Blood Trasfusion Practice ShortsdrprasadingleyNo ratings yet

- Health Examination Record (CS Form 86)Document2 pagesHealth Examination Record (CS Form 86)gina dunggonNo ratings yet

- Digestive SystemDocument25 pagesDigestive Systembazaar9No ratings yet

- Ancient Science Institute of Research On Alternative Medicine (Asiram)Document28 pagesAncient Science Institute of Research On Alternative Medicine (Asiram)kckejaman100% (1)

- Kokich 2Document5 pagesKokich 2ilich sevillaNo ratings yet

- Laporan Kasus SMF/ Bagian Ilmu Bedah (Short Case 1)Document59 pagesLaporan Kasus SMF/ Bagian Ilmu Bedah (Short Case 1)Roby Aditya SuryaNo ratings yet

- Kidneys BiochemistryDocument53 pagesKidneys BiochemistryMi PatelNo ratings yet

- Transplantation Immunology PDFDocument99 pagesTransplantation Immunology PDFVictoriaNo ratings yet

New Treatment Modality For Maxillary Hypoplasia in Cleft Patients

New Treatment Modality For Maxillary Hypoplasia in Cleft Patients

Uploaded by

KaranPadhaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

New Treatment Modality For Maxillary Hypoplasia in Cleft Patients

New Treatment Modality For Maxillary Hypoplasia in Cleft Patients

Uploaded by

KaranPadhaCopyright:

Available Formats

Case Report

New treatment modality for maxillary hypoplasia in cleft patients

Protraction facemask with miniplate anchorage

Seung-Hak Baeka; Keun-Woo Kimb; Jin-Young Choic

ABSTRACT

Objective: To present cleft patients treated with protraction facemask and miniplate anchorage

(FM/MP) in order to demonstrate the effects of FM/MP on maxillary hypoplasia.

Materials and Methods: The cases consisted of cleft palate only (12 year 1 month old girl,

treatment duration 5 16 months), unilateral cleft lip and alveolus (12 year 1 month old boy,

treatment duration 5 24 months), and unilateral cleft lip and palate (7 year 2 month old boy,

treatment duration 5 13 months). Curvilinear type surgical miniplates (Martin, Tuttlinger, Germany)

were placed into the zygomatic buttress areas of the maxilla. After 4 weeks, mobility of the

miniplates was checked, and the orthopedic force (500 g per side, 30u downward and forward from

the occlusal plane) was applied 12 to 14 hours per day.

Results: In all cases, there was significant forward displacement of the point A. Side effects such

as labial tipping of the upper incisors, extrusion of the upper molars, clockwise rotations of the

mandibular plane, and bite opening, were considered minimal relative to that usually observed with

conventional protraction facemask with tooth-borne anchorage.

Conclusions: FM/MP can be an effective alternative treatment modality for maxillary hypoplasia

with minimal unwanted side effects in cleft patients. (Angle Orthod. 2010;80:783–791.)

KEY WORDS: Maxillary protraction; Facemask; Miniplate

INTRODUCTION unwanted side effects such as labioversion of the

upper incisors, extrusion of the upper molars, coun-

In Class III malocclusion patients with mild to

terclockwise rotation of the upper occlusal plane, and

moderate maxillary hypoplasia, the protraction face-

eventual clockwise rotation of the mandible.3–6 There-

mask has been used to stimulate sutural growth at the

fore, labial inclined maxillary incisors and/or a vertical

circum-maxillary suture sites in growing patients.1–3 To

facial growth pattern would be contraindications for

transmit the orthopedic force from the protraction

facemask therapy with tooth-borne anchorage.

facemask to the maxilla, intraoral devices such as a

To allow the direct transmission of orthopedic force

labiolingual arch, quad helix, and rapid maxillary

to the circum-maxillary sutures, intentionally ankylosed

expansion (RME) have been used. However, the use

primary canines, osseointegrated implants, and ortho-

of the upper dentition as anchorage cannot avoid

dontic miniscrews have been used as skeletal anchor-

a

Associate Professor, Department of Orthodontics, School of age for protraction facemasks.7–11 Since surgical

Dentistry, Dental Research Institute, Seoul National University, miniplates are a reliable means for applying orthodon-

Seoul, South Korea. tic and orthopedic forces,12 Kircelli et al.,13 Cha et al.,14

b

Resident and Graduate Masters Student, Department of and Kircelli and Pektas15 introduced the protraction

Orthodontics, School of Dentistry, Seoul National University,

facemask with miniplate anchorage (FM/MP) therapy

Seoul, South Korea.

c

Associate Professor, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial to treat Class III malocclusion with maxillary hypopla-

Surgery, School of Dentistry, Dental Research Institute, Seoul sia and hypodontia (Figure 1).

National University, Seoul, South Korea. The protocol of FM/MP is as follows: (1) After an

Corresponding author: Dr Jin-Young Choi, Department of Oral approximate 1–2 cm horizontal vestibular incision is

and Maxillofacial Surgery, School of Dentistry, Dental Research

made just below the zygomatic buttress area under

Institute, Seoul National University, Yeonkun-dong #28, Jongro-

ku, Seoul 110-768, South Korea local anesthesia, the zygomatic buttress is exposed

(e-mail: jinychoi@snu.ac.kr) with a subperiosteal flap. (2) Curvilinear type surgical

Accepted: September 2009. Submitted: July 2009. miniplates (Martin, Tuttlinger, Germany) are bent

G 2010 by The EH Angle Education and Research Foundation, according to the anatomical shape of the zygomatic

Inc. buttress. (3) The distal end hole of the miniplate should

DOI: 10.2319/073009-435.1 783 Angle Orthodontist, Vol 80, No 4, 2010

784 BAEK, KIM, CHOI

Figure 1. Comparison of pretreatment (left) and posttreatment (right) in patient with Class III malocclusion. (a) Facial photographs. (b) Intraoral

photographs. (c) Lateral cephalograms. (d) Superimposition (solid line: pretreatment; dotted line: posttreatment).

be cut to make a hook for elastics. (4) After the patients who were treated with FM/MP and to

miniplates are placed into the zygomatic buttress demonstrate the effect of FM/MP on maxillary hypo-

areas, three self-tapping type screws are used per plasia in cleft patients.

side to fix the miniplates (Figure 2a). (5) The distal end

of the miniplate should be exposed through the CASE REPORTS

attached gingiva between the upper canine and first CASE 1

premolar to control the vector of elastic traction

(Figure 2b). (6) Four weeks after placement of the Skeletal Class III malocclusion with cleft palate (CP)

miniplates, their mobility is checked and the orthopedic and anterior open bite (Figure 3, Table 1).

force (500 g per side, 30u downward and forward from

the occlusal plane) is applied for 12 to 14 hours per Diagnosis

day. (7) It is recommended to overcorrect the The patient was a 12 year 1 month old girl with CP

malocclusion into positive overjet and a slight Class only. She presented with concave facial profile,

II canine and molar relationship. anterior crossbite (29 mm overjet), and anterior open

Cleft patients often develop Class III malocclusion bite (22 mm overbite). Cephalometric analysis

with maxillary hypoplasia and vertical facial growth showed skeletal Class III malocclusion with maxillary

pattern due to the combined effects of the congenital hypoplasia (ANB, 25.4u; A to N perp, 23.4 mm), steep

deformity itself and the scar tissues after surgical mandibular plane angle (FMA, 32.7u), and a skeletal

repair.16 These are contraindications for conventional age after the pubertal growth spurt according to the

facemask therapy. However, little research has been cervical vertebrae maturation index (CVMI, stage 4).17

done on the use of FM/MP in cleft patients. Therefore, Her condition was one of the contraindications for

the purpose of this case report is to present three cleft conventional facemask therapy.

Angle Orthodontist, Vol 80, No 4, 2010

MAXILLARY PROTRACTION: FACEMASK AND MINIPLATE 785

anterior open bite was corrected by downward and

forward movement of the maxilla. Slight labial tipping of

the upper incisors (DU1 to SN, 2.0u) occurred after

correction of anterior crossbite and open bite.

CASE 2

Skeletal Class III malocclusion with unilateral cleft lip

and alveolus (UCLA) and vertical facial growth pattern

(Figure 4, Table 1).

Diagnosis

The patient was a 12 year 1 month old boy with

UCLA on the left side. Although he presented with a

straight facial profile, he had an anterior crossbite

(22.5 mm overjet), upper anterior crowding, and peg

laterals on the cleft side. Although the anteroposterior

skeletal relationship (ANB, 1.4u) was within normal

range and the upper and lower incisors were lingually

inclined (U1 to SN, 95.1u; IMPA, 86.9u), a vertical facial

growth pattern (FMA, 33.2u) existed. His skeletal age

was before his pubertal growth spurt according to the

CVMI (stage 3).17

Treatment Plan

Conventional facemask protraction with a tooth-

borne anchorage device was not appropriate because

the patient had a vertical facial growth pattern.

Figure 2. Schematic drawing of the surgical positioning (a) and

intraoral position of the miniplate (b).

Therefore, the FM/MP was used to avoid unwanted

side effects.

Treatment Plan Treatment Progress

Although growth observation and reassessment Initially, the fixed orthodontic appliance was placed

after 2 years were proposed, her parents wanted to to correct the anterior crowding in the upper arch. The

receive the FM/MP therapy. The possibility of orthog- FM/MP therapy was started 4 weeks after placement

nathic surgery after pubertal growth was explained. of the miniplates according to the protocol.

Treatment Progress Treatment Results

FM/MP therapy was started 4 weeks after place- After 24 months of FM/MP therapy, there was a 3.1-

ment of the miniplates according to the protocol. mm forward movement of point A (DA to N perp). ANB

During protraction, the fixed appliances were placed angle was changed from 1.4u to 3.5u, and a Class II

to align the dentition. canine and molar relationship was obtained. The

finding that there was a negligible counterclockwise

Treatment Results rotation of the mandibular plane (0.4u) and occlusal

plane angle (20.9u) indicated that there were almost

After 16 months of FM/MP therapy, there was

no side effects such as extrusion of the upper molars

significant forward movement of the point A (DA to N

and bite opening. Labial tipping of the upper incisors

perp, 5.6 mm). The ANB angle was changed from

(DU1 to SN, 4.9u) occurred due to alignment.

25.4u to 2.9u, and a Class II canine and molar

relationship, normal overbite, and overjet were ob-

CASE 3

tained. A slight counterclockwise rotation of the occlusal

plane angle (21.8u) was interpreted to mean that there Skeletal Class III malocclusion with unilateral cleft lip

was almost no side effect such as extrusion of the upper and palate (UCLP) and vertical facial growth pattern

molars. Although the FMA was increased 4.3u, the (Figure 5, Table 1).

Angle Orthodontist, Vol 80, No 4, 2010

786 BAEK, KIM, CHOI

Figure 3. Comparison of pretreatment (left) and posttreatment (right) in patient with cleft palate (case 1). (a) Facial photographs. (b) Intraoral

photographs. (c) Lateral cephalograms. (d) Superimposition (solid line: pretreatment; dotted line: posttreatment).

Diagnosis Treatment Results

The patient was a 7 year 2 month old boy with a Similar to Case 2, there was a 3.0-mm forward

UCLP on the right side. Although he presented with a movement of point A (DA to N perp) after 13 months of

straight facial profile, he had an anterior crossbite protraction facemask therapy. The ANB angle was

(22.7 mm overjet). Although the anteroposterior skel- changed from 1.6u to 3.1u, and Class II canine and

etal relationship (ANB, 1.6u) was within normal range molar relationships were obtained. Although there was

and the upper incisors were lingually inclined (U1 to a slight counterclockwise rotation of the mandibular

SN, 93.9u), a vertical facial growth pattern existed plane (20.9u) and occlusal plane angle (22.5u), there

(FMA, 34.6u). His skeletal age was before his pubertal was no bite opening in the anterior teeth. Some labial

growth spurt according to CVMI (stage 2).17 tipping of the upper incisors (DU1 to SN, 2.7u) occurred

after correction of the anterior crossbite.

Treatment Plan

DISCUSSION

FM/MP was planned to maximize protraction of the

maxilla and to avoid unwanted side effects. Site for Placement of Miniplates

The zygomatic buttress area was used as the site for

Treatment Progress

placement of the miniplates due to following reasons:

FM/MP therapy was started 4 weeks after place- (1) It has enough thickness and adequate bone

ment of the miniplates according to the protocol. quality.18 (2) It is near to the center of resistance of

Angle Orthodontist, Vol 80, No 4, 2010

MAXILLARY PROTRACTION: FACEMASK AND MINIPLATE 787

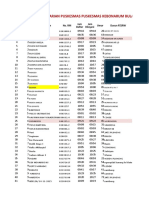

Table 1. Comparison of the Skeletal, Dental, and Soft Tissue Variables Between Pretreatment (T0) and Posttreatment (T1)

Case 1 Case 2 Case 3

Variable T0 T1 T0 T1 T0 T1

Anteroposterior skeletal relationship

SNA (u) 76.0 80.6 74.9 77.1 78.5 80.4

SNB (u) 81.4 77.7 73.5 73.6 76.9 77.3

ANB (u) 25.4 2.9 1.4 3.5 1.6 3.1

A to N perp (mm) 23.4 2.2 25.2 22.1 23.3 20.3

Pog to N perp (mm) 4.7 20.6 212.2 210.2 28.0 28.0

Wits appraisal (mm) 215.5 23.6 25.2 21.9 25.4 22.5

Vertical skeletal relationship

Bjork sum (u) 403.7 408.2 403.2 403.6 402.3 401.5

Saddle angle (u) 128.4 125.4 120.7 122.1 116.9 117.2

Articular angle (u) 143.9 154.1 152.4 152.8 150.1 151.1

Gonial angle (u) 131.4 128.7 130.1 128.7 135.3 133.2

Facial height ratio (%) 55.7 52.7 58.6 58.1 60.4 61.6

Palatal plane angle (u) 22.3 21.5 2.7 2.9 2.2 1.8

FMA (u) 32.7 37.0 33.2 32.7 34.6 33.7

Mandibular plane to SN plane angle (u) 43.7 48.2 43.2 43.6 42.3 41.5

Occlusal plane to SN plane angle (u) 21.6 19.8 24.6 23.7 23.2 20.7

Dental relationship

U1 to SN (u) 106.4 108.4 95.1 100.0 93.9 96.6

IMPA (u) 88.2 76.3 86.9 87.5 86.8 82.2

Soft tissue

Nasolabial angle (u) 105.8 107.3 117.4 119.0 115.4 109.3

the nasomaxillary complex so that the force vector can movement in the maxilla when protraction was in

be placed close to the center of rotation of the conjunction with RME compared with protraction

nasomaxillary complex.12,19 without RME. Liou and Tsai22 presented the combined

use of repeated rapid maxillary expansion and

Vector Control constriction and intraoral springs for maxillary protrac-

tion and concluded that significant advancement of the

The direction of force vector was 30u downward and point A could be obtained.

forward from the occlusal plane. Tanne et al.20 and However, a recent prospective, randomized clinical

Miyasaka-Hiraga et al.21 reported that downward and trial23 showed that facemask therapy, with or without

forward force produced uniform stretch and translatory RME, produced equivalent changes in the dentofacial

repositioning of the nasomaxillary complex in an complex and insisted that RME might not be indis-

anterior direction. However, conventional dental an- pensable to maxillary protraction unless a transverse

chorage usually results in counterclockwise rotation of deficiency exists. In our cases, we did not use RME

the palatal plane, and clockwise rotation of the because cleft lip and palate patients do not have some

mandible, which would be unfavorable in a patient or whole parts of the midpalatal suture. Since this

with vertical growth pattern. could affect the amount of maxillary advancement in

The miniplate can transmit the orthopedic force cleft patients, further studies will be necessary.

directly to the maxilla and minimize rotational effect.

Although there was a slight increase of FMA (4.3u) in Timing of Treatment

Case 1, Cases 2 and 3 showed negligible changes of

the palatal plane angle, FMA, and mandibular plane to There are numerous articles that advocate the

SN angle (Table 1). protraction therapy at an early stage.5,24–28 Because

the palatomaxillary suture becomes highly interdigitat-

ed with increasing age, it becomes difficult to

Conjunction with RME

disarticulate the palatal bone from the pterygoid

Expansion of the maxilla before or during protraction process.29 After the pubertal growth peak, side effects

of the maxilla has been performed to facilitate such as tooth movement and/or mandibular rotation

protraction by disarticulating the circum-maxillary rather than maxillary protraction are likely to be the

sutures and initiating a cellular response in these major response to treatment.5,30 However, Baik4 and

sutures.1,3,5 Baik4 reported that there was more forward Sung and Baik31 insisted that there was no statistical

Angle Orthodontist, Vol 80, No 4, 2010

788 BAEK, KIM, CHOI

Figure 4. Comparison of pretreatment (left) and posttreatment (right) in patient with unilateral cleft lip and alveolus (case 2). (a) Facial

photographs. (b) Intraoral photographs. (c) Lateral cephalograms. (d) Superimposition (solid line: pretreatment; dotted line: posttreatment).

difference when changes due to treatment were 0.9 mm to 2.9 mm advancement of the point A. So25

compared according to ages. insisted that the effect of protraction facemask therapy

On the other hand, Kircelli and Pektas15 reported on the maxilla was two thirds skeletal and one third

that protraction using the FM/MP in relatively older dental changes.

patients (11 to 13 years) was successful with minimum In cases with facemask and skeletal anchorage,

dentoalveolar side effects. We also confirmed that amounts of the maxillary advancement have been

there was a significant maxillary protraction with fewer reported to be 4.0 to 4.8 mm.9,15,34 Therefore, maxillary

dentoalveolar side effects using the MP/FM in the advancement can be enhanced by skeletal anchorage

patient after the pubertal growth peak and menarche rather than conventional dental anchorage in growing

(Case 1, CVMI stage 4).17 patients.

In our cases, although a similar treatment protocol

was used, the amounts of maxillary advancement

varied according to cleft types (approximately 3.0 mm–

Comparison of the Amount of

5.6 mm). Since the duration of protraction (approxi-

Maxillary Advancement

mately 13–24 months) was relatively longer than in the

In cases of untreated Class III malocclusion with other studies,9,15,34 the scar tissues of cleft patients can

maxillary hypoplasia, Shanker et al.32 reported that be one of the reasons for variations in the amount of

point A came forward only 0.2 mm over a 6-month maxillary protraction. This result was in accordance

period. With conventional facemask therapy, Kim et with Buschang et al.35 concerning limited protraction

al.33 from meta-analysis, reported that it produced results in cleft patients.

Angle Orthodontist, Vol 80, No 4, 2010

MAXILLARY PROTRACTION: FACEMASK AND MINIPLATE 789

Figure 5. Comparison of pretreatment (left) and posttreatment (right) in patient with unilateral cleft lip and palate (case 3). (a) Facial photographs.

(b) Intraoral photographs. (c) Lateral cephalograms. (d) Superimposition (solid line: pretreatment; dotted line: posttreatment).

Overcorrection are needed. Because the miniplates are independent

from dentition, simultaneous orthodontic treatment and

Ngan et al.36 and MacDonald et al.37 insisted that

maxillary protraction is an attractive advantage.

facemask therapy does not normalize the forward

The FM/MP can be used over a relatively longer

growth of the maxilla and that patients resume a Class

period than conventional facemask because it is

III growth pattern by deficient maxillary growth during the

independent of the upper dentition. According to

follow-up period. Therefore, overcorrection into Class II Ishikawa et al.,39 the effects of conventional facemask

canine and molar relationships is mandatory to com- therapy were significantly less in the second year, and

pensate for deficient posttreatment maxillary growth. no benefit from any treatment longer than 1 year was

Cleft patients seem to need more overcorrection established. However, we confirmed that FM/MP could

than ordinary Class III malocclusion cases with result in uniform advancement of the maxilla during the

maxillary hypoplasia because there are limitations in entire treatment period (Table 1).

the amounts of maxillary advancement and a high In addition, cleft patients have more vertical growth

relapse rate due to scar tissues.38 If the amount of pattern than noncleft patients,40 and excessive clock-

maxillary advancement is large and the patients and wise rotation of the mandible during facemask therapy

parents want a relatively short-term treatment, distrac- can worsen the facial profile. FM/MP can minimize

tion osteogenesis during adolescence or orthognathic clockwise rotation of the mandible and prevent

surgery in adulthood can be recommended. aggravation of the facial profile.

Advantages of FM/MP in Cleft Patients CONCLUSION

In adolescent cleft patients, multiple orthodontic N FM/MP can be an effective alternative treatment

treatment procedures such as alignment, leveling, modality for cleft patients with maxillary hypoplasia

arch expansion, and preparation for bone graft surgery with minimal unwanted side effects.

Angle Orthodontist, Vol 80, No 4, 2010

790 BAEK, KIM, CHOI

REFERENCES on the craniofacial complex: a study using the finite element

method. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1989;95:

1. McNamara JA. An orthopedic approach to the treatment of 200–207.

Class III malocclusion in young patients. J Clin Orthod. 21. Miyasaka-Hiraga J, Tanne K, Nakamura S. Finite element

1987;21:598–608. analysis for stresses in the craniofacial sutures produced by

2. Delaire J. Maxillary development revisited: relevance to the maxillary protraction forces applied at the upper canines.

orthopaedic treatment of Class III malocclusions. Br J Orthod. 1994;21:343–348.

Eur J Orthod. 1997;19:289–311. 22. Liou EJ, Tsai WC. A new protocol for maxillary protraction in

3. Nartallo-Turley PE, Turley PK. Cephalometric effects of cleft patients: repetitive weekly protocol of alternate rapid

combined palatal expansion and facemask therapy on Class maxillary expansions and constrictions. Cleft Palate

III malocclusion. Angle Orthod. 1998;68:217–224. Craniofac J. 2005;42:121–127.

4. Baik HS. Clinical results of the maxillary protraction in 23. Vaughn GA, Mason B, Moon HB, Turley PK. The effects of

Korean children. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1995;108: maxillary protraction therapy with or without rapid palatal

583–592. expansion: a prospective, randomized clinical trial.

5. Kapust AJ, Sinclair PM, Turley PK. Cephalometric effects of Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2005;128:299–309.

face mask/expansion therapy in Class III children: a 24. Tindlund RS. Orthopaedic protraction of the midface in the

comparison of three age groups. Am J Orthod Dentofacial deciduous dentition. Results covering 3 years out of

Orthop. 1998;113:204–212. treatment. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1989;17(suppl 1):17–9.

6. Hickham JH. Maxillary protraction therapy: diagnosis and 25. So LL. Effects of reverse headgear treatment on sagittal

treatment. J Clin Orthod. 1991;25:102–113. correction in girls born with unilateral complete cleft lip and

7. Kokich VG, Shapiro PA, Oswald R, Koskinen-Moffett L, cleft palate—skeletal and dental changes. Am J Orthod

Clarren SK. Ankylosed teeth as abutments for maxillary Dentofacial Orthop. 1996;109:140–147.

protraction: a case report. Am J Orthod. 1985;88:303–307. 26. Saadia M, Torres E. Sagittal changes after maxillary

8. Silva Filho OG, Ozawa TO, Okada CH, Okada HY, Carvalho protraction with expansion in Class III patients in the

RM. Intentional ankylosis of deciduous canines to reinforce primary, mixed, and late mixed dentitions: a longitudinal

maxillary protraction. J Clin Orthod. 2003;37:315–320. retrospective study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2000;

9. Enacar A, Giray B, Pehlivanoglu M, Iplikcioglu H. Facemask 117:669–680.

therapy with rigid anchorage in a patient with maxillary 27. Suda N, Suzukl MI, Hirose K, Hiyama S, Suzuki S, Kuroda

hypoplasia and severe oligodontia. Am J Orthod Dentofacial T. Effective treatment plan for maxillary protraction: is the

Orthop. 2003;123:571–577. bone age useful to determine the treatment plan?

10. Hong H, Nagn P, Li HG, Qi LG, Stephen HY. Use of Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2000;118:56–62.

onplants as stable anchorage for facemask treatment. Angle 28. Franchi L, Baccetti T, McNamara JA Jr. Postpubertal

Orthod. 2005;75:453–460. assessment of treatment timing for maxillary expansion

11. Vachiramon A, Urata M, Kyung HM, Yamashita DD, Yen SL. and protraction therapy followed by fixed appliances.

Clinical applications of orthodontic microimplant anchorage Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2004;126:555–568.

in craniofacial patients. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2009;46: 29. Melsen B, Melsen F. The postnatal development of the

136–146. palatomaxillary region studied on human autopsy material.

12. Umemori M, Sugawara J, Mitani H, Nagasaka H, Kamamura Am J Orthod. 1982;82:329–342.

H. Skeletal anchorage for open-bite correction. Am J Orthod 30. Cha KS. Skeletal changes of maxillary protraction in patients

Dentofacial Orthop. 1999;115:166–174. exhibiting skeletal class III malocclusion: a comparison of

13. Kircelli BH, Pektaş ZO, Uçkan S. Orthopedic protraction with three skeletal maturation groups. Angle Orthod. 2003;73:

skeletal anchorage in a patient with maxillary hypoplasia 26–35.

and hypodontia. Angle Orthod. 2006;76:156–163. 31. Sung SJ, Baik HS. Assessment of skeletal and dental

14. Cha BK, Lee NK, Choi DS. Maxillary protraction treatment of changes by maxillary protraction. Am J Orthod Dentofacial

skeletal Class III children using miniplates anchorage. Orthop. 1998;114:492–502.

Korean J Orthod. 2007;37:73–84. 32. Shanker S, Ngan P, Wade D, Beck M, Yiu C, Hägg U, Wei

15. Kircelli BH, Pektas ZO. Midfacial protraction with skeletally SH. Cephalometric A point changes during and after

anchored face mask therapy: a novel approach and maxillary protraction and expansion. Am J Orthod Dentofa-

preliminary results. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008; cial Orthop. 1996;110:423–430.

133:440–449. 33. Kim JH, Viana MA, Graber TM, Omerza FF, BeGole EA.

16. Baek SH, Moon HS, Yang WS. Cleft type and Angle’s The effectiveness of protraction face mask therapy: a meta-

classification of malocclusion in Korean cleft patients. analysis. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1999;115:

Eur J Orthod. 2002;24:647–653. 675–685.

17. Hassel B, Farman AG. Skeletal maturation evaluation using 34. Singer SL, Henry PJ, Rosenberg I. Osseointegrated

cervical vertebrae. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1995; implants as an adjunct to facemask therapy: a case report.

107:58–66. Angle Orthod. 2000;70:253–262.

18. Sugawara J, Nishimura M, Nagasaka H, Kawamura H. 35. Buschang PH, Porter C, Genecov E, Genecov D, Sayler KE.

Temporary anchorage devices in orthodontics. Skeletal Facemask therapy of preadolescents with unilateral cleft lip

Anchorage System Using Orthodontic Miniplates. St Louis, and palate. Angle Orthod. 1994;64:145–150.

Mo: Mosby; 2009;15:320. 36. Ngan PW, Hagg U, Yiu C, Wei SH. Treatment response and

19. Tanne K, Matsubara S, Sakuda M. Location of the centre of long-term dentofacial adaptations to maxillary expansion

resistance for the nasomaxillary complex studied in a three and protraction. Semin Orthod. 1997;3:255–264.

dimensional finite element model. Br J Orthod. 1995;22: 37. MacDonald KE, Kapust AJ, Turley PK. Cephalometric

227–232. changes after the correction of Class III malocclusion with

20. Tanne K, Hiraga J, Kakiuchi K, Yamagata Y, Sakuda M. maxillary expansion/facemask therapy. Am J Orthod Den-

Biomechanical effect of anteriorly directed extraoral forces tofacial Orthop. 1999;116:13–24.

Angle Orthodontist, Vol 80, No 4, 2010

MAXILLARY PROTRACTION: FACEMASK AND MINIPLATE 791

38. Baek SH, Lee JK, Lee JH, Kim MJ, Kim JR. Comparison of unilateral cleft lip and palate patients. Cleft Palate

treatment outcome and stability between distraction osteo- Craniofac J. 2000;37:92–97.

genesis and LeFort I osteotomy in cleft patients with 40. Van den Dungen GM, Ongkosuwito EM, Aartman IH,

maxillary hypoplasia. J Craniofac Surg. 2007;18: Prahl-Andersen B. Craniofacial morphology of Dutch pa-

1209–1215. tients with bilateral cleft lip and palate and noncleft controls

39. Ishikawa H, Kitazawa S, Iwasaki H, Nakamura S. Effects of at the age of 15 years. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2008;45:

maxillary protraction combined with chin-cap therapy in 661–666.

Angle Orthodontist, Vol 80, No 4, 2010

You might also like

- Mechanistic Insights in Cardiorenal Syndrome: Published August 23, 2022Document13 pagesMechanistic Insights in Cardiorenal Syndrome: Published August 23, 2022Raul Fernando100% (1)

- Test Bank The Art of Public Speaking 11th Edition by Stephen LucasDocument26 pagesTest Bank The Art of Public Speaking 11th Edition by Stephen Lucasbachababy0% (3)

- MCQ's Blood BankDocument74 pagesMCQ's Blood BankAlireza Goodazri100% (2)

- 10 1093@ejo@cjv053Document11 pages10 1093@ejo@cjv053Drazza TagaldinNo ratings yet

- Camouflage Treatment of Skeletal Class III Malocclusion With Asymmetry Using A Bone-Borne Rapid Maxillary ExpanderDocument13 pagesCamouflage Treatment of Skeletal Class III Malocclusion With Asymmetry Using A Bone-Borne Rapid Maxillary ExpanderClinica Dental AdvanceNo ratings yet

- Bong 2011 PDFDocument14 pagesBong 2011 PDFkarenchavezalvanNo ratings yet

- Nonsurgical Correction of A Class III Malocclusion in An Adult by Miniscrew-Assisted Mandibular Dentition DistalizationDocument11 pagesNonsurgical Correction of A Class III Malocclusion in An Adult by Miniscrew-Assisted Mandibular Dentition DistalizationNeycer Catpo NuncevayNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2666430522000036 MainDocument12 pages1 s2.0 S2666430522000036 MainDANTE DELEGUERYNo ratings yet

- Benedict Wimes, Mascara FacialDocument8 pagesBenedict Wimes, Mascara FacialjamilistccNo ratings yet

- Artículo DentalDocument6 pagesArtículo DentalAngélicaLujánNo ratings yet

- Severe Class II Division 1 MalocclusionDocument14 pagesSevere Class II Division 1 MalocclusionCARMEN ROSA AREVALO ROLDANNo ratings yet

- Xu 2014Document10 pagesXu 2014Marcos Gómez SosaNo ratings yet

- Correction of Late Adolescent Skeletal Class III Using The Alt-RAMEC Protocol and Skeletal AnchorageDocument11 pagesCorrection of Late Adolescent Skeletal Class III Using The Alt-RAMEC Protocol and Skeletal AnchoragePorchiddioNo ratings yet

- Severe Anterior Open Bite With Mandibular Retrusion Treated With Multiloop Edgewise Archwires and Microimplant Anchorage ComplementedDocument10 pagesSevere Anterior Open Bite With Mandibular Retrusion Treated With Multiloop Edgewise Archwires and Microimplant Anchorage ComplementedLedir Luciana Henley de AndradeNo ratings yet

- (23350245 - Balkan Journal of Dental Medicine) Treatment of Maxillary Retrusion-Face Mask With or Without RPEDocument5 pages(23350245 - Balkan Journal of Dental Medicine) Treatment of Maxillary Retrusion-Face Mask With or Without RPEmalifaragNo ratings yet

- Openbite MIA AJODODocument10 pagesOpenbite MIA AJODOscribdlptNo ratings yet

- Ajodo 3Document10 pagesAjodo 3ayisNo ratings yet

- Camouflage Treatment of Skeletal Class III Malocclusion With Multiloop Edgewise Arch Wire and Modified Class III Elastics by Maxillary Mini-Implant AnchorageDocument11 pagesCamouflage Treatment of Skeletal Class III Malocclusion With Multiloop Edgewise Arch Wire and Modified Class III Elastics by Maxillary Mini-Implant AnchorageValery V JaureguiNo ratings yet

- Angle Orthod. 2012 82 5 846-52Document7 pagesAngle Orthod. 2012 82 5 846-52brookortontiaNo ratings yet

- VR Mesh 5Document6 pagesVR Mesh 5Zaid DewachiNo ratings yet

- Maxillary Arch Distalization Using Interradicular Miniscrews and The Lever-Arm ApplianceDocument8 pagesMaxillary Arch Distalization Using Interradicular Miniscrews and The Lever-Arm ApplianceJuan Carlos CárcamoNo ratings yet

- Early Management of Class III Malocclusion in Mixed DentitionDocument4 pagesEarly Management of Class III Malocclusion in Mixed DentitionMariana SantosNo ratings yet

- Posterior Crossbite With Mandibular Asymmetry Treated With Lingual Appliances, Maxillary Skeletal Expanders, and Alveolar Bone MiniscrewsDocument21 pagesPosterior Crossbite With Mandibular Asymmetry Treated With Lingual Appliances, Maxillary Skeletal Expanders, and Alveolar Bone MiniscrewsJuliana ÁlvarezNo ratings yet

- Ishihara 2013Document12 pagesIshihara 2013Mirek SzNo ratings yet

- Openbite CamouflageDocument8 pagesOpenbite CamouflageRakesh RaveendranNo ratings yet

- Dentofacial Effects of Two Facemask Therapies For Maxillary Protraction Miniscrew Implants Versus Rapid Maxillary ExpandersDocument9 pagesDentofacial Effects of Two Facemask Therapies For Maxillary Protraction Miniscrew Implants Versus Rapid Maxillary ExpandersMariana SantosNo ratings yet

- 2020 Article 265Document7 pages2020 Article 265Fabian BarretoNo ratings yet

- APOSTrendsOrthod 2016 6 4 228 186439 PDFDocument5 pagesAPOSTrendsOrthod 2016 6 4 228 186439 PDFDr sneha HoshingNo ratings yet

- Treatment of An Anterior Open Bite, Bimaxillary Protrusion and Mesiocclusion by The Extraction of Premolars and The Use of Clear AlignersDocument14 pagesTreatment of An Anterior Open Bite, Bimaxillary Protrusion and Mesiocclusion by The Extraction of Premolars and The Use of Clear AlignersAstrid HutabaratNo ratings yet

- Angle Orthod. 2014 84 5 919-30Document12 pagesAngle Orthod. 2014 84 5 919-30brookortontiaNo ratings yet

- Effects of Facemask Treatment Anchored With Miniplates After Alternate Rapid Maxillary Expansions and Constrictions A Pilot StudyDocument8 pagesEffects of Facemask Treatment Anchored With Miniplates After Alternate Rapid Maxillary Expansions and Constrictions A Pilot StudyMariana SantosNo ratings yet

- Absolute Anchorage With Universal T-Loop Mechanics For Severe Deepbite and Maxillary Anterior Protrusion and Its 10-Year StabilityDocument12 pagesAbsolute Anchorage With Universal T-Loop Mechanics For Severe Deepbite and Maxillary Anterior Protrusion and Its 10-Year StabilitysmritiNo ratings yet

- Jung 2018Document14 pagesJung 2018Anonymous ckVKx4njgNo ratings yet

- Multiloop Edgewise Arch-Wire Technique For Skeleta PDFDocument4 pagesMultiloop Edgewise Arch-Wire Technique For Skeleta PDFanhca4519No ratings yet

- 404 AlamDocument5 pages404 AlamEva ApriyaniNo ratings yet

- 2176 9451 Dpjo 24 05 52Document8 pages2176 9451 Dpjo 24 05 52Crisu CrisuuNo ratings yet

- Art Maloclusiones CepilloDocument5 pagesArt Maloclusiones Cepillopaola tarazonaNo ratings yet

- Vertical-Dimension Control During En-MasseDocument13 pagesVertical-Dimension Control During En-MasseLisbethNo ratings yet

- Space Closure in The Maxillary Posterior Area Through The Maxillary SinusDocument8 pagesSpace Closure in The Maxillary Posterior Area Through The Maxillary SinusArsenie TataruNo ratings yet

- +distraction Osteogenesis For The Cleftlip and PalateDocument12 pages+distraction Osteogenesis For The Cleftlip and PalategrisguzlNo ratings yet

- Class II Bimaxillary ProtrusionDocument13 pagesClass II Bimaxillary ProtrusionPrasne SriNo ratings yet

- Daimaruya 2010Document7 pagesDaimaruya 2010KATERIN TTITO MAMANINo ratings yet

- EtiologyDocument3 pagesEtiologyMoe AtraNo ratings yet

- Lee 2019Document7 pagesLee 2019Monojit DuttaNo ratings yet

- 7 Articulo Bone-Anchored Maxillary Protraction in A Patient With Complete Cleft Lip and Palate: A Case ReportDocument8 pages7 Articulo Bone-Anchored Maxillary Protraction in A Patient With Complete Cleft Lip and Palate: A Case ReportErika NuñezNo ratings yet

- C-Orthodontic Microimplant For Distalization of Mandibular Dentition in Class III CorrectionDocument9 pagesC-Orthodontic Microimplant For Distalization of Mandibular Dentition in Class III CorrectionNeeraj AroraNo ratings yet

- Absolute Anchorage With Universal T-Loop Mechanics For Severe Deepbite and Maxillary Anterior Protrusion and Its 10-Year StabilityDocument12 pagesAbsolute Anchorage With Universal T-Loop Mechanics For Severe Deepbite and Maxillary Anterior Protrusion and Its 10-Year StabilityThang Nguyen TienNo ratings yet

- Articulo 3Document8 pagesArticulo 3Carolina SepulvedaNo ratings yet

- Angle 2007 Ene 155-166Document12 pagesAngle 2007 Ene 155-166André MéndezNo ratings yet

- SUB158101Document4 pagesSUB158101chirag sahgalNo ratings yet

- 2215 3411 Odovtos 20 02 31Document7 pages2215 3411 Odovtos 20 02 31habeebNo ratings yet

- Use of Palatal Miniscrew Anchorage and Lingual Multi-Bracket Appliances To Enhance Efficiency of Molar Scissors-Bite CorrectionDocument8 pagesUse of Palatal Miniscrew Anchorage and Lingual Multi-Bracket Appliances To Enhance Efficiency of Molar Scissors-Bite CorrectionTriyunda PermatasariNo ratings yet

- Maxillary Protraction / Orthodontic Courses by Indian Dental AcademyDocument86 pagesMaxillary Protraction / Orthodontic Courses by Indian Dental Academyindian dental academyNo ratings yet

- Craniofacial Changes in Patients With Class III Malocclusion Treated With The Rampa SystemDocument7 pagesCraniofacial Changes in Patients With Class III Malocclusion Treated With The Rampa Systemapi-192260741100% (1)

- Early Treatment Protocol For Skeletal Class III MalocclusionDocument7 pagesEarly Treatment Protocol For Skeletal Class III MalocclusionJavier Farias VeraNo ratings yet

- Arvystas 1998Document4 pagesArvystas 1998Саша АптреевNo ratings yet

- 2011-Orthopedic Treatment of Class III Malocclusion With Rapid Maxillary Expansion Combined With A Face Mask A Cephalometric Assessment of Craniofacial Growth PatternsDocument7 pages2011-Orthopedic Treatment of Class III Malocclusion With Rapid Maxillary Expansion Combined With A Face Mask A Cephalometric Assessment of Craniofacial Growth PatternsMariana SantosNo ratings yet

- Kaya 2011Document8 pagesKaya 2011ortodoncia 2022No ratings yet

- Orthodontic Treatmentafter High Condylectomyin Patientswith Unilateral Condylar HyperplasiaDocument9 pagesOrthodontic Treatmentafter High Condylectomyin Patientswith Unilateral Condylar HyperplasiaOrtodoncia UNAL 2020No ratings yet

- Miniscrew-anchored maxillary protraction in growing Class III patientsDocument17 pagesMiniscrew-anchored maxillary protraction in growing Class III patientscirurgicafontellesNo ratings yet

- TRATRAMIENTO DE CLASE II DIVISION 2 CON ExTREMA PROFUNDIDADDocument13 pagesTRATRAMIENTO DE CLASE II DIVISION 2 CON ExTREMA PROFUNDIDADMelisa GuerraNo ratings yet

- Orthodontic Management of A Horizontally Impacted Maxillary Incisor in An Adolescent PatientDocument11 pagesOrthodontic Management of A Horizontally Impacted Maxillary Incisor in An Adolescent PatientMarcos Gómez SosaNo ratings yet

- Bernstein 1984Document7 pagesBernstein 1984KaranPadhaNo ratings yet

- Brennan 2001Document8 pagesBrennan 2001KaranPadhaNo ratings yet

- Faciomaxillary Fractures in North India A Statistical Analysis and Review of ManagementDocument5 pagesFaciomaxillary Fractures in North India A Statistical Analysis and Review of ManagementKaranPadhaNo ratings yet

- Significance: Clinical of The Anastomotic Branches FacialDocument4 pagesSignificance: Clinical of The Anastomotic Branches FacialKaranPadhaNo ratings yet

- Facial Nerve Function After Partial Superficial Parotidectomy: An 11-Year Review (1987-1997)Document4 pagesFacial Nerve Function After Partial Superficial Parotidectomy: An 11-Year Review (1987-1997)KaranPadhaNo ratings yet

- Bainton 1990Document2 pagesBainton 1990KaranPadhaNo ratings yet

- Bloodborne The Old Hunters Collectors Edition Guide 6alw0hoDocument2 pagesBloodborne The Old Hunters Collectors Edition Guide 6alw0hoKaranPadhaNo ratings yet

- Tech Connect Retail Private Limited,: Grand TotalDocument1 pageTech Connect Retail Private Limited,: Grand TotalKaranPadhaNo ratings yet

- Circulatory MatchDocument2 pagesCirculatory MatchJinky AydallaNo ratings yet

- Esthetic Analysis Checklist: 8 Steps For Systematic Treatment PlanningDocument1 pageEsthetic Analysis Checklist: 8 Steps For Systematic Treatment PlanningMarcus EskilssonNo ratings yet

- Burning Mouth SyndromeDocument28 pagesBurning Mouth SyndromeMelissa KanggrianiNo ratings yet

- Neuroscience ABCsDocument261 pagesNeuroscience ABCsxxx xxx100% (2)

- Prometric Dental Exam Questions For: DHA Nov 2019Document5 pagesPrometric Dental Exam Questions For: DHA Nov 2019Aniket PotnisNo ratings yet

- 1901: Three Main Blood Groups DiscoveredDocument4 pages1901: Three Main Blood Groups Discoveredjohn dave cuevasNo ratings yet

- Biology: Topic - Endocrine System Class-VIII Board - ICSEDocument3 pagesBiology: Topic - Endocrine System Class-VIII Board - ICSEItu DeyNo ratings yet

- Pre Transfusion TestingDocument57 pagesPre Transfusion TestingDominic Bernardo100% (4)

- 2nd Quarter Summative Test No.1 in Science 6Document1 page2nd Quarter Summative Test No.1 in Science 6Marilou Kimayong100% (9)

- Coffee Dental StainsDocument2 pagesCoffee Dental StainsL SalemNo ratings yet

- Laporan Gigi Bulan JuliDocument765 pagesLaporan Gigi Bulan Julimaurin's diaryNo ratings yet

- Peripheral Nervous SystemDocument39 pagesPeripheral Nervous SystemHengky HanggaraNo ratings yet

- Posterior Abdominal WallDocument25 pagesPosterior Abdominal Wallapi-19916399No ratings yet

- Ala 3Document30 pagesAla 3Alaz NellyNo ratings yet

- Anexo-Unit1-Body SystemsDocument5 pagesAnexo-Unit1-Body SystemsPau GuauNo ratings yet

- Art 3Document16 pagesArt 3Carol LozanoNo ratings yet

- Circulation Blood Components Worksheet 2021Document4 pagesCirculation Blood Components Worksheet 2021api-523306558No ratings yet

- Difference Between Complete and Incomplete AntibodiesDocument4 pagesDifference Between Complete and Incomplete AntibodiesAnindita Abriani PiradeNo ratings yet

- Homologous Blood Trasfusion Practice ShortsDocument23 pagesHomologous Blood Trasfusion Practice ShortsdrprasadingleyNo ratings yet

- Health Examination Record (CS Form 86)Document2 pagesHealth Examination Record (CS Form 86)gina dunggonNo ratings yet

- Digestive SystemDocument25 pagesDigestive Systembazaar9No ratings yet

- Ancient Science Institute of Research On Alternative Medicine (Asiram)Document28 pagesAncient Science Institute of Research On Alternative Medicine (Asiram)kckejaman100% (1)

- Kokich 2Document5 pagesKokich 2ilich sevillaNo ratings yet

- Laporan Kasus SMF/ Bagian Ilmu Bedah (Short Case 1)Document59 pagesLaporan Kasus SMF/ Bagian Ilmu Bedah (Short Case 1)Roby Aditya SuryaNo ratings yet

- Kidneys BiochemistryDocument53 pagesKidneys BiochemistryMi PatelNo ratings yet

- Transplantation Immunology PDFDocument99 pagesTransplantation Immunology PDFVictoriaNo ratings yet