Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Defining Cyberbullying A Qualitative Res

Defining Cyberbullying A Qualitative Res

Uploaded by

Jay JayOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Defining Cyberbullying A Qualitative Res

Defining Cyberbullying A Qualitative Res

Uploaded by

Jay JayCopyright:

Available Formats

CYBERPSYCHOLOGY & BEHAVIOR

Volume 11, Number 4, 2008 ©

Mary Ann Liebert, Inc.

DOI: 10.1089/cpb.2007.0042

Rapid Communication

Defining Cyberbullying: A Qualitative Research into the

Perceptions of Youngsters

HEIDI VANDEBOSCH, Ph.D. and KATRIEN VAN CLEEMPUT, M.Sc.

ABSTRACT

Data from 53 focus groups, which involved students from 10 to 18 years old, show that youngsters

often interpret “cyberbullying” as “Internet bullying” and associate the phenomenon with a wide

range of practices. In order to be considered “true” cyberbullying, these practices must meet

several criteria. They should be intended to hurt (by the perpetrator) and perceived as hurtful (by

the victim); be part of a repetitive pattern of negative offline or online actions; and be performed in

a relationship characterized by a power imbalance (based on “real-life” power criteria, such as

physical strength or age, and/or on ICT-related criteria such as technological know-how and

anonymity).

INTRODUCTION lying,” or “bullying via Internet or mobile phone.”4–6,10 In

the second case, the researchers

T HE LITERATURE ABOUT CYBERBULLYING is still rela- measure the respondent’s experience with a range tively scarce

and characterized by a lack of of cyber activities, which are assumed to represent

conceptual clarity. The phenomenon is defined in insulting or threatening somebody via e-mail or instant

different ways (usually—implicitly or explicitly— messaging; intentionally sending a virus to someone). 11

starting from definitions of “traditional” bullying), 1–7 and The existing studies about cyberbullying have

the distinction from other forms of “deviant” cyber produced inconsistent results. The estimations for the

activities, such as cyber harassment,4 flaming,8 and prevalence of cyberbullying, for instance, vary greatly.

cyberstalking,9 is often very vague. These differences seem to be the result (at least in part)

Different perspectives about exactly what of the definitions and operationalizations of

cyberbullying is have also led to different kinds of cyberbullying that are used in different studies. Surveys

operationalizations. Cyberbullying is mostly studied by that rely on both indirect and direct measurements of

means of online surveys4,10,11 or school surveys among cyberbullying12 further suggest that cyber activities

youngsters.5,6,12 In these types of surveys, researchers perceived as “forms of cyberbullying” by the researchers

directly or indirectly measure the respondent’s are not always considered cyberbullying by the

experience (as a bully, victim, or bystander) with respondents.

cyberbullying. In the first case, respondents are asked The above-mentioned problems call for the

whether (and sometimes how often) they have been the development of a clear definition of cyberbullying,

perpetrator of or have been confronted with “online which is congruent with the perceptions of the re-

bullying,” “cyberbulforms of cyberbullying (e.g.,

Department of Communication Studies, University of Antwerp, Antwerpen, Belgium.

499

500 VANDEBOSCH AND VAN CLEEMPUT

search participants. In this article, we take a first step in (30.5%), technical secondary education; and 31

this direction by presenting the results of a qualitative respondents (11.1%), vocational secondary education.

research into the experiences and views of youngsters Of the respondents, 98.6% said they made use of the

with regard to cyberbullying. Internet, and 90.3% appeared to have a mobile phone.

Negative aspects of the Internet and mobile phones

METHOD In the first part of the focus groups, the youngsters

were asked to mention some of the positive and negative

To gain deeper insight into the perspectives of

aspects of information and communication technologies.

youngsters with regard to cyberbullying, focus groups

Looking at the number of times that certain negative

were organized. This method was chosen because it was

aspects associated with the Internet and with mobile

expected that the interaction among youngsters about a

phones were mentioned during the focus groups gives us

conversation topic that is part of their everyday (social)

a rough idea about the problems and dangers that most

life—namely, ICT—would reveal detailed information

concerned the youngsters. These were (in order of

about their concrete Internet and mobile phone practices

diminishing frequency) being contacted by strangers

and their individual and group norms and values with

(mentioned 52 times), computer viruses (49), hacking

regard to electronic communication. Given the deviant

(38), pedophilic attempts (22), cyberbullying (20),

topic of the research, the interviewers applied a gentle

threats (17), spam (17), stalking (14), e-advertising (14),

approach: starting from youngsters’ everyday (positive

sexual intimidation (12), pornographic Web sites (11),

and negative) experiences with ICT, the interviewers

people who turn on their webcam unwanted (10), the

moved on to the topic of cyberbullying and catered for

cost of the communication (10), technical failure (10),

general opinions about and personal experiences (as a

health-related problems (5), and the content of certain

bystander, victim, or perpetrator) with this phenomenon.

Web sites (3).

Because of the exploratory nature of the study, the

aim was to reach a heterogeneous audience of What is cyberbullying?

youngsters to obtain a wide range of opinions about and

experiences with cyberbullying. To involve students General descriptions (cyberbullying is Internet

from different ages, sexes, and educational levels, bullying) versus a summation of Internet and mobile

classes ranging from the last year of elementary school phone practices. When asked to provide a description of

to the last year of secondary school; classes from cyberbullying, most students seemed to equate it with

general, technical, and vocational education; and classes “bullying via the Internet,” or they mentioned Internet

with both boys and girls, were asked for their practices they regarded as examples of cyberbullying.

cooperation. These examples were sometimes extreme cases that had

The focus group conversations were all tape recorded been discussed in the media. More often, however,

and literally transcribed. The texts were then imported in students had personal or interpersonal experiences with

Atlas-Ti (a program for the analysis of qualitative data) Internet and mobile phone uses that in some instances

and coded. The analyses focused on the detection of could be considered forms of cyberbullying.

general trends as well as on possible differences in Most of the interpersonal examples of cyberbullying

answers between subgroups (based on sex, age, and were practices related to instant messaging. Several

education level). students admitted that they (or somebody they knew)

had been the victim of hacking. In those instances,

someone else had broken into their MSN account, for

RESULTS instance, and changed their password, deleted their

contact list, and sent insulting or strange messages to

Background characteristics of the respondents their contact persons. The most common reaction of

victims to hacking was changing their e-mail accounts

Two hundred seventy-nine youngsters participated in and passwords. Another MSN practice often mentioned

the 53 focus groups that were organized in 17 classes of by the respondents was being contacted by strangers.

DEFINING CYBERBULLYING: THE PERCEPTIONS OF YOUNGSTERS 501

These intrusions were often unwelcome and therefore

10 different schools. Of them, 142 (50.9%) were boys,

blocked or deleted.

137 (49.1%) girls. The mean age of the respondents was

The respondents also reported other forms of Internet

14.1 (the youngest was 10 years old, the oldest 19), SD

bullying, such as sending huge amounts of buzzers or

2.098. One hundred nineteen respondents (42.7%)

winks to someone, copying personal conversations and

followed general secondary education; 85 respondents

sending them to others, spreading gossip, manipulating

pictures of persons and sending them to others, making attacked thus seemed to play an important role. On the

Web sites with humiliating comments about a student, other hand, the line between what was and what was not

sending threatening e-mails, misleading someone via e- perceived as a personal attack was often very vague.

mail, humiliating someone in an open chat room, and One girl said, for instance, that being called “ugly” on

sending messages with sexual comments. MSN was acceptable to her, but being called “a whore”

On the other hand, several respondents (especially the was certainly not. The relationship between the

older ones) seemed to have negative experiences with perpetrator and the victim also played an important role

mobile phones (e.g., getting calls in the middle of the in the way messages were interpreted. Getting a message

night, being threatened through the telephone). Some from a friend that might be considered an insult (and a

also admitted they had done this to others. form of cyberbullying) by a third party was often

These Internet and mobile phone practices were given regarded at as a joke, a sign of common understanding,

as examples of cyberbullying. The respondents noticed, or a kind of playful interaction between friends.

however, that the same practices could be interpreted in

other ways, depending on the precise circumstances. Repetition

Following are a few “crucial” characteristics of Another aspect that students mentioned spontaneously

cyberbullying that were suggested by the respondents when describing the difference between cyberbullying

and indeed seem to overlap to a high degree with criteria and cyber-teasing was that cyberbullying implied

used to define traditional bullying. repetition. However, this criterion did not necessarily

imply several instances of electronic bullying. A single

Intended to hurt by the perpetrator (and perceived as

negative act via Internet or mobile phone that followed

hurtful by the victim). According to the respondents,

on traditional ways of bullying was also considered

cyberbullying was clearly different from teasing via the

cyberbullying.

Internet or mobile phone. One huge distinction,

according to the youngsters who participated in the Power imbalance

focus groups, was that the perpetrator of cyberbullying

really wanted to hurt the feelings of another person. The interviews showed that the respondents who

Cyber jokes, on the other hand, were not intended to admitted they had done things via the Internet or mobile

cause the victim negative feelings—they were meant to phone that might be hurtful to others indicated that they

be funny. The respondents acknowledged, however, that had mostly operated anonymously or disguised

there might be a difference between the way things were themselves and that their victims were often people they

intended and the way things were perceived. What some also knew in the real world. In real life, these victims

perpetrators considered an innocent joke might be were perceived by the perpetrator as weaker, of equal

considered an aggressive attack by the victim (or even strength, or stronger. The weaker victims were usually

the other way around). also the target of traditional bullying. These students

Asking students why they did things via Internet or were described as “strange,” “shy,” “small,” and so on.

mobile phone that might be perceived as hurtful by Cyber actions aimed at these youngsters were almost

others revealed a wide range of motives. In some unanimously considered cyberbullying. On the other

instances, the perpetrator’s intent to harm was quite hand, there were people whom the perpetrators

clear. Some said, for instance, that they took revenge on considered equals. These could be friends or former

those who had bullied them (in real life or in friends. The same Internet or mobile phone actions that

cyberworld) or attacked and harassed another person via were considered cyberbullying in the case of the more

vulnerable targets were in the latter instances more often

502 VANDEBOSCH AND VAN CLEEMPUT

Internet or mobile phone because they had an argument

described as “cyber-teasing,” “cyber-arguing,” or

with or just couldn’t stand the person. In other instances,

“cyber-fighting” (although a considerable number of

things were done just for fun because the youngsters felt

students thought of the last phenomenon as

bored or because they wanted to display their

“cyberbullying”). In some instances, persons who were

technological skills and power.

perceived as more powerful in real life were the target of

The way in which Internet or mobile phone practices

cyber attacks. The anonymity of the Internet and mobile

were actually perceived by the victims appeared to

phone and knowledge of ICT applications13 indeed

depend on the kind of practice and the relationship

seemed to empower those who were unlikely to become

between the individuals involved. Some respondents

reallife bullies or who were even victims of traditional

mentioned, for instance, that receiving computer viruses

bullying.

(especially those sent by strangers) was not really

From the side of the victim, not knowing the person

bullying, but being threatened, scared, or insulted was.

behind the cyber attacks was often frustrating and

The degree to which the individuals felt personally

increased the feeling of powerlessness. Knowing the

individual(s) behind a certain action, on the other hand, term (e.g., electronic bullying, digital bullying). On the

made it possible to put the action into perspective (and other hand, the question What is cyberbullying? often

to perceive it as negative or not) and to react leads to a numeration of media and interpersonal

accordingly. The focus groups showed that in the case of experiences that might be considered examples of

friends, the initial anonymity was often given up by the cyberbullying. The direct and indirect ways of

perpetrators themselves. measuring cyberbullying behavior used in most of the

scientific cyberbullying studies so far thus seem to be

closely related to the natural descriptions of

Familiar persons versus strangers, individual, or group

attacks cyberbullying by youngsters. However, the focus group

interviews also make clear that measuring youngsters’

While many Internet and mobile phone practices that experiences with a range of activities, without taking

might be hurtful to others were directed to people whom into account the context in which these activities take

the perpetrators also knew in person, other practices place, is not an adequate method. To be classified as

were aimed at total strangers. Some students mentioned, cyberbullying, these Internet or mobile phone practices

for instance, that they dialed a random mobile phone should be intended by the sender to hurt; part of a

number and started insulting the person who picked up repetitive pattern of negative offline or online actions;

the phone. Others took on another identity and misled and performed in a relationship characterized by a power

persons whom they met in chat rooms or sent insulting imbalanced (based on real-life power criteria such as

or threatening messages to the e-mail address of an physical strength or age and/or on ICTrelated criteria

unknown person. The victims, in these cases, functioned such as technological know-how and anonymity). These

as an individual but random target. In some instances, criteria help, for instance, to distinguish cyberbullying

the perpetrators made a more strategic selection (which from cyber-teasing (not intended to hurt, not necessarily

resembles the way traditional bullies choose their repetitive, and performed in an equal-power

victims) based on the (presumed) reallife characteristics relationship) and cyber arguing (intended to hurt, not

of the persons they met online. In these instances, they necessarily repetitive, and performed in an equal-power

targeted weaker strangers (e.g., younger, inexperienced relationship). Cyberbullying often occurs within the

persons, girls). context of existing social (offline) groups and is mostly

From the part of the receiver, the anonymity of the aimed at one individual. In this way, cyberbullying also

sender often made it difficult to know whether the differs from forms of harassment by strangers aimed at

person was someone they actually knew or a stranger. one wellchosen target (e.g., pedophilic acts) or at a

But in many instances, the victim did have a clue about group of people (e.g., sending viruses or spam).

the identity of the perpetrator (e.g., because of the

content of the messages, the way others in their

environment behaved) or was informed of the identity

REFERENCES

by the perpetrator or a third party.

Furthermore, the focus group interviews showed that 1. Patchin JW, Hinduja S. Bullies move beyond

certain Internet and mobile phone practices were not theschoolyard: a preliminary look at cyberbullying.

only aimed at individuals or groups but also performed Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice 2006; 4:148–69.

by individuals or groups. This aspect, however, does not 2. Belsey B. www.cyberbullying@org (accessed Oct.

seem to be unique to cyberbullying. Teasing or arguing 2006).

via the Internet, for instance, can also imply multiple 3. Wired Safety. Cyberbuulying, Flaming and

DEFINING CYBERBULLYING: THE PERCEPTIONS OF YOUNGSTERS 503

senders and receivers. Cyberstalking. www.internetsuperheroes.org/

CONCLUSION cyberbullying/ summit_8feb05_2.html (accessed March

2007).

The focus groups reveal that youngsters can name 4. Ybarra ML, Mitchell KJ. Online aggressor/targets,

aggressors, and targets: a comparison of associated youth

(and have experience with) a wide range of negative

characteristics. Journal of Child Psychology and

Internet and mobile phone practices. On top of their list Psychiatry 2004; 45:1308–16.

is being contacted by strangers. Other, less frequently 5. Li Q. New bottle but old wine: a research of cyberbullying

mentioned aspects are receiving viruses, being hacked, in schools. Computers in Human Behavior 2007;

pedophilic attempts, and cyberbullying. The term 23:1777–91.

cyberbullying is often familiar to youngsters via the 6. Li Q. Cyberbullying in schools: a research of

media and is usually equated with “bullying via the genderdifferences. School Psychology International

Internet.” When referring to bullying that occurs via 2006; 27:157–70.

7. Baruch Y. Bullying on the Net: adverse behavior one-

electronic means in general, it might therefore be

mail and its impact. Information and Management 2005;

worthwhile to consider the use of a more appropriate 42:361–71.

8. O’Sullivan PB, Flanagin AJ. Reconceptualizing

“flaming” and other problematic messages. New Media

& Society 2003; 5:69–94.

9. Spitzberg BH, Hoobler G. Cyberstalking and the

technologies of interpersonal terrorism. New Media and

Society 2002; 4:71–92.

10. Ybarra ML. Linkages between depressive

symptomatology and Internet harassment among young

regu-

lar Internet users. CyberPsychology and Behavior 2004; 7:

247–57.

11. Qrius. (2005). Online pesten: Geintje of kwetsend?

www.planet.nl/planet/show/id761788/contenti

546528/sc3eb360 (accessed Oct. 2006).

12. Vandebosch H, Van Cleemput K, Mortelmans D, etal.

(2006) Cyberpesten bij jongeren in Vlaanderen–

onderzoeksrapport. Brussel: viWTA(available at

www.viwta.

be/files/Eindrapport_cyberpesten_(nw).pdf

13. Jordan T. (1999) Cyberpower: the culture and politics of

cyberspace and the Internet. London: Routledge.

Address reprint requests to:

Dr. Heidi Vandebosch

Department of Communication Studies

University of Antwerp

Sint-Jacobstraat 2

Antwerpen, Belgium 2000

E-mail: heidi.vandebosch@ua.ac.be

You might also like

- Caribbean Studies Internal Assessment 2017Document39 pagesCaribbean Studies Internal Assessment 2017Kris84% (19)

- OBDII Codes PDFDocument238 pagesOBDII Codes PDFedhuam50% (6)

- Chapter 1 AnintroductionincyberbullyingresearchDocument15 pagesChapter 1 AnintroductionincyberbullyingresearchElisha Rey QuiamcoNo ratings yet

- List of Consumables/MaterialsDocument2 pagesList of Consumables/MaterialsJay JayNo ratings yet

- The Pathophysiology of CancerDocument1 pageThe Pathophysiology of Cancermisskitcat100% (11)

- How To Run Your Brand's Advertising ProcessDocument15 pagesHow To Run Your Brand's Advertising ProcessDhivya GandhiNo ratings yet

- Rockwell Laser Industries - Laser Safety Training and Consulting BrochureDocument16 pagesRockwell Laser Industries - Laser Safety Training and Consulting Brochurer_paura100% (1)

- Defining Cyberbullying A Qualitative ResDocument6 pagesDefining Cyberbullying A Qualitative ResMemeFNo ratings yet

- Rapid Communication: C P & B Volume 11, Number 4, 2008 © Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. DOI: 10.1089/cpb.2007.0042Document6 pagesRapid Communication: C P & B Volume 11, Number 4, 2008 © Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. DOI: 10.1089/cpb.2007.0042Oana VezanNo ratings yet

- Practical Research 1Document45 pagesPractical Research 1Samantha SalamancaNo ratings yet

- Brown (2014)Document10 pagesBrown (2014)FlorinaNo ratings yet

- Cyberbullying Identification Prevention Response 2023Document9 pagesCyberbullying Identification Prevention Response 2023yukilatsu999No ratings yet

- Cyberbullying Identification Prevention Response 2024Document9 pagesCyberbullying Identification Prevention Response 2024PinkynurseNo ratings yet

- Research ProposalDocument46 pagesResearch ProposalJules Gerald Morales JoseNo ratings yet

- Literature ReviewDocument53 pagesLiterature ReviewjharanaNo ratings yet

- Research CyberbullyingDocument9 pagesResearch CyberbullyingBlayne PiamonteNo ratings yet

- Journal Pone 0253180Document19 pagesJournal Pone 0253180karend.penahNo ratings yet

- IssuePaper13 Cyberbullying SA Impact - Responses1Document17 pagesIssuePaper13 Cyberbullying SA Impact - Responses1Jolene GoeiemanNo ratings yet

- Cyber Victimization in Middle School and RelationsDocument11 pagesCyber Victimization in Middle School and RelationsZayden VarickNo ratings yet

- Bystander Responses To Cyberbullying The Role of Perceived - 2022 - Computers IDocument13 pagesBystander Responses To Cyberbullying The Role of Perceived - 2022 - Computers IFulaneto AltoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 FinalDocument26 pagesChapter 1 FinalYeshua Marion Dequito David100% (1)

- Chapter 1 SampleDocument8 pagesChapter 1 SampleSky SaracanlaoNo ratings yet

- Issue Paper 13 Cyberbullying in SA Impact and ResponsesDocument16 pagesIssue Paper 13 Cyberbullying in SA Impact and ResponsesmaxlothuNo ratings yet

- Short Research PaperDocument6 pagesShort Research PaperCrystal Queen GrasparilNo ratings yet

- Assessing Cyberbullying in Higher Education: Ali Kamali Kamali@missouriwestern - EduDocument11 pagesAssessing Cyberbullying in Higher Education: Ali Kamali Kamali@missouriwestern - EduRishika guptaNo ratings yet

- Digital Orientation and Cyber-Victimization of College Students As Mediated by Their Attitude Toward CrimeDocument12 pagesDigital Orientation and Cyber-Victimization of College Students As Mediated by Their Attitude Toward CrimePsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Research Paper - Group 3Document37 pagesResearch Paper - Group 3Sophia Luisa V. DaelNo ratings yet

- Bidgoli Knijnenburg Grossklags 2016Document10 pagesBidgoli Knijnenburg Grossklags 2016Master BeaterNo ratings yet

- JISEv 25 N 1 P 71Document6 pagesJISEv 25 N 1 P 71Zayden VarickNo ratings yet

- IBRAHIM Group Thesis Chapter 1 4Document50 pagesIBRAHIM Group Thesis Chapter 1 4Norodin IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Tsitsika 2015Document7 pagesTsitsika 2015Asuwad Bin AbdullahNo ratings yet

- Online GamingDocument5 pagesOnline GamingWinsome Carl CamusNo ratings yet

- Basic Research 1Document4 pagesBasic Research 1JezenEstherB.PatiNo ratings yet

- Lino Bebula 2Document8 pagesLino Bebula 2sikelelaphetshana2No ratings yet

- Computers in Human Behavior: Vimala BalakrishnanDocument3 pagesComputers in Human Behavior: Vimala BalakrishnanNurul Fatehah Binti KamaruzaliNo ratings yet

- Cyberbullying Review RelatedDocument11 pagesCyberbullying Review RelatedJennie Marlow AddisonNo ratings yet

- Computers in Human Behavior: Chiao Ling Huang, Sining Zhang, Shu Ching YangDocument8 pagesComputers in Human Behavior: Chiao Ling Huang, Sining Zhang, Shu Ching YangNurul Fatehah Binti KamaruzaliNo ratings yet

- Cyberbullying PamphletDocument9 pagesCyberbullying Pamphletapi-360229778No ratings yet

- The Perceptions of Cyberbullied Student - Victims On Cyberbullying and Their Life SatisfactionDocument7 pagesThe Perceptions of Cyberbullied Student - Victims On Cyberbullying and Their Life SatisfactionPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- PR2 Chapter 1 2Document8 pagesPR2 Chapter 1 2Krianne KilvaniaNo ratings yet

- Cyberbullying Practices and Experiences of The Filipino College Students' Social Media UsersDocument9 pagesCyberbullying Practices and Experiences of The Filipino College Students' Social Media UsersGreyie kimNo ratings yet

- Cyberbullying: A Review of The Literature: Charles E. Notar, Sharon Padgett, Jessica RodenDocument9 pagesCyberbullying: A Review of The Literature: Charles E. Notar, Sharon Padgett, Jessica RodenIthnaini KamilNo ratings yet

- Futureinternet 11 00120 v2Document11 pagesFutureinternet 11 00120 v2Indhumathi MurugesanNo ratings yet

- IssuePaper13 Cyberbullying SA Impact Responses1Document17 pagesIssuePaper13 Cyberbullying SA Impact Responses1andiswamsaba5No ratings yet

- Mitigating Cyberbullying Among Teens The Crucial Role of Moral Education in School CurriculaDocument5 pagesMitigating Cyberbullying Among Teens The Crucial Role of Moral Education in School CurriculaKIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONNo ratings yet

- Cybergossip and Problematic Internet Use in Cyberaggress - 2022 - Computers in HDocument11 pagesCybergossip and Problematic Internet Use in Cyberaggress - 2022 - Computers in HFulaneto AltoNo ratings yet

- Lived Experiences of Cyberbullying VICTIMS: A Phenomenological StudyDocument13 pagesLived Experiences of Cyberbullying VICTIMS: A Phenomenological StudyNicole TrinidadNo ratings yet

- Introduction CyberbullyingDocument3 pagesIntroduction CyberbullyingNicholas CharlesNo ratings yet

- Smith Et Al-2008-Journal of Child Psychology and PsychiatryDocument10 pagesSmith Et Al-2008-Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatrywesley_wfNo ratings yet

- The Impacts of Cyberbullying To The Self-Esteem of Grade 11 Stem D of Cldh-Ei Student'SDocument7 pagesThe Impacts of Cyberbullying To The Self-Esteem of Grade 11 Stem D of Cldh-Ei Student'SLovely Bloom BagalayNo ratings yet

- Cyberbullied To Death An Analysis of VicDocument9 pagesCyberbullied To Death An Analysis of Vicsafras faizerNo ratings yet

- Fare Fare Si MaleDocument7 pagesFare Fare Si MalePinkynurseNo ratings yet

- Improved Textual Cyberbullying Detection Using Data Mining: Paridhi Singhal and Ashish BansalDocument8 pagesImproved Textual Cyberbullying Detection Using Data Mining: Paridhi Singhal and Ashish BansalCarlos CaraccioNo ratings yet

- Cyber Bullying Final ReportDocument69 pagesCyber Bullying Final Reportnabeela sultoniNo ratings yet

- Results - Group 4Document15 pagesResults - Group 4Harmanpreet SinghNo ratings yet

- Donegan. 2012. Bullying and CyberbullyingDocument10 pagesDonegan. 2012. Bullying and CyberbullyinggitatungawiNo ratings yet

- Kita Na Ba Tong Manuscript Na ToDocument21 pagesKita Na Ba Tong Manuscript Na ToDCRUZNo ratings yet

- Exercise 3 - (Cyberbully)Document6 pagesExercise 3 - (Cyberbully)slayerhunter90No ratings yet

- Sentiment Analysis-Based Method To Prevent Cyber BullyingDocument15 pagesSentiment Analysis-Based Method To Prevent Cyber BullyinglbishtNo ratings yet

- Sociology RP PDFDocument16 pagesSociology RP PDFNandini SooraNo ratings yet

- The Issue of Cyberbullying ofDocument10 pagesThe Issue of Cyberbullying ofkhent doseNo ratings yet

- Bullying and CyberbullyingDocument10 pagesBullying and CyberbullyingYamila Borges RiveraNo ratings yet

- 18bbl055 RESEARCH PROPOSALDocument9 pages18bbl055 RESEARCH PROPOSALunnati jainNo ratings yet

- Cyberbullying and CyberstalkingDocument7 pagesCyberbullying and CyberstalkingRahoul123No ratings yet

- Mastering Cyberbullying: A Comprehensive Guide for Dealing with Online HarassmentFrom EverandMastering Cyberbullying: A Comprehensive Guide for Dealing with Online HarassmentNo ratings yet

- Topics For Impromptu and ExtempoDocument1 pageTopics For Impromptu and ExtempoJay JayNo ratings yet

- Warm Greetings To EveryoneDocument2 pagesWarm Greetings To EveryoneJay JayNo ratings yet

- Barista ToolsDocument3 pagesBarista ToolsJay JayNo ratings yet

- FNB CBLMDocument77 pagesFNB CBLMJay JayNo ratings yet

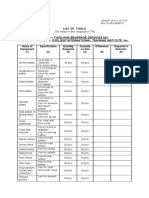

- List of Tools (As Listed in The Respective TR) Program: Food and Beverage Services NciDocument4 pagesList of Tools (As Listed in The Respective TR) Program: Food and Beverage Services NciJay JayNo ratings yet

- How Does Homer Convey The Idea of Continuity Between Generations inDocument3 pagesHow Does Homer Convey The Idea of Continuity Between Generations inJay JayNo ratings yet

- List of Instructional Materials/Library HoldingsDocument2 pagesList of Instructional Materials/Library HoldingsJay JayNo ratings yet

- Program: Food and Beverage Services NC Ii Name of Institution/Company Exelient International Training Institute, IncDocument2 pagesProgram: Food and Beverage Services NC Ii Name of Institution/Company Exelient International Training Institute, IncJay JayNo ratings yet

- Critical Thinking QuestionsDocument7 pagesCritical Thinking QuestionsJay Jay0% (1)

- Handouts Logic 1Document23 pagesHandouts Logic 1Jay JayNo ratings yet

- Research Instrument SampleDocument6 pagesResearch Instrument SampleJay Jay50% (2)

- 6 Good Reasons To Study Logic & All aBOUT LOGICDocument10 pages6 Good Reasons To Study Logic & All aBOUT LOGICJay JayNo ratings yet

- For Additiona Concept MTBMLEDocument3 pagesFor Additiona Concept MTBMLEJay JayNo ratings yet

- Rectified Syllabi Following The Format of An Obe Standard Syllabus and Reflecting The Designed Flexible Learning SystemDocument3 pagesRectified Syllabi Following The Format of An Obe Standard Syllabus and Reflecting The Designed Flexible Learning SystemJay JayNo ratings yet

- Teaching StrategiesDocument5 pagesTeaching StrategiesJay JayNo ratings yet

- HO Tech WritingDocument62 pagesHO Tech WritingJay JayNo ratings yet

- Different Theories in Learning MaterialsDocument2 pagesDifferent Theories in Learning MaterialsJay JayNo ratings yet

- Self Compacting ConcreteDocument9 pagesSelf Compacting ConcreteVimal VimalanNo ratings yet

- Human Resource ManagementDocument13 pagesHuman Resource ManagementJerom EmmnualNo ratings yet

- Hydropower Engineering IIDocument141 pagesHydropower Engineering IIashe zinab100% (7)

- Design of Tower Foundations: $orarnarfDocument7 pagesDesign of Tower Foundations: $orarnarfjuan carlos molano toroNo ratings yet

- 26-Ra Fire Fighting Pipes Threading, Grooving & PaintingDocument5 pages26-Ra Fire Fighting Pipes Threading, Grooving & PaintingAsad AyazNo ratings yet

- Employees' Health Insurance and Pension (Shakai Hoken 社会保険)Document2 pagesEmployees' Health Insurance and Pension (Shakai Hoken 社会保険)Putri HalinNo ratings yet

- Test 1Document14 pagesTest 1Phương LinhNo ratings yet

- Rightway Short ProfileDocument2 pagesRightway Short ProfileRightway Charitable FoundationNo ratings yet

- Notice To The General PublicDocument5 pagesNotice To The General Publicvser19No ratings yet

- MKT 201 - Lecture 2 & 3Document73 pagesMKT 201 - Lecture 2 & 3Duval PearsonNo ratings yet

- Chater 1 ScriptDocument2 pagesChater 1 ScriptJessa CaberteNo ratings yet

- Presentation On Café Coffee Day: by Nailesh Jacob 09020242012Document35 pagesPresentation On Café Coffee Day: by Nailesh Jacob 09020242012Nailesh JacobNo ratings yet

- Mtic NotesDocument50 pagesMtic NotesAnshita GargNo ratings yet

- Banking Laws Cases Diligence Required From BanksDocument4 pagesBanking Laws Cases Diligence Required From Bankslalyn100% (1)

- The Principles of InvestmentDocument29 pagesThe Principles of InvestmentsimilikitiawokwokNo ratings yet

- Science Has Made Life Better But Not Easier.' Discuss.Document2 pagesScience Has Made Life Better But Not Easier.' Discuss.Yvette LimNo ratings yet

- Initial Environmental Examination: Section No. 1: Jalalabad-Kunar 220 KV Double Circuit Transmission Line ProjectDocument129 pagesInitial Environmental Examination: Section No. 1: Jalalabad-Kunar 220 KV Double Circuit Transmission Line ProjectfazailNo ratings yet

- Rosacea FulminansDocument8 pagesRosacea FulminansberkerNo ratings yet

- Multiple Choice Questions (MCQ) On ForecastingDocument3 pagesMultiple Choice Questions (MCQ) On ForecastingJoven Castillo100% (10)

- Combined SpecsheetDocument1 pageCombined SpecsheetApurva PatelNo ratings yet

- Amphenol Connector D38999 - III-357336 PDFDocument82 pagesAmphenol Connector D38999 - III-357336 PDFSiva KumarNo ratings yet

- Cloud Computing Lab ManualDocument57 pagesCloud Computing Lab ManualAdvithNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Spark Plug Removal & ReplacementDocument4 pagesLesson Plan Spark Plug Removal & ReplacementVon MoreNo ratings yet

- BRMDocument6 pagesBRMGagan Kumar RaoNo ratings yet

- Main Engine Failure Check List: Company Forms and Check ListsDocument2 pagesMain Engine Failure Check List: Company Forms and Check ListsopytnymoryakNo ratings yet

- Jet Propulsion: Fred LandisDocument7 pagesJet Propulsion: Fred LandisVikash ShawNo ratings yet