Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Curriculum Topics in Pharmacy

Curriculum Topics in Pharmacy

Uploaded by

Donaldo Delvis DuddyCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Mind Maps in MedicineDocument159 pagesMind Maps in MedicineAnonymous jSTkQVC27b100% (44)

- Nursing Care Plan ON: Caesarean DeliveryDocument22 pagesNursing Care Plan ON: Caesarean DeliveryKavi rajput79% (14)

- Clinical PharmacyDocument16 pagesClinical Pharmacyblossoms_diyya299850% (6)

- Clinical Pharmacist in ICUDocument26 pagesClinical Pharmacist in ICUCosmina GeorgianaNo ratings yet

- NICU Bereavement Care and Follow-Up Support For Families and StaffDocument10 pagesNICU Bereavement Care and Follow-Up Support For Families and StaffEduardo Rios DuboisNo ratings yet

- Pharmacists' Role in The Healthcare System: January 2006Document9 pagesPharmacists' Role in The Healthcare System: January 2006Anca IacobNo ratings yet

- Pharmacy and Its Paradigm ShiftDocument4 pagesPharmacy and Its Paradigm ShiftKristel Keith NievaNo ratings yet

- Pharmacist Role in Health Care SystemDocument8 pagesPharmacist Role in Health Care SystemLoo Soo WeiNo ratings yet

- DR - Ismail HamedDocument25 pagesDR - Ismail HamedHanan AhmedNo ratings yet

- AMA Sample PaperDocument6 pagesAMA Sample PaperfmrashedNo ratings yet

- Clinical Pharmacy ReviewDocument8 pagesClinical Pharmacy Reviewsagar dhakalNo ratings yet

- Research Articles Independent Community Pharmacists' Perspectives On Compounding in Contemporary Pharmacy EducationDocument8 pagesResearch Articles Independent Community Pharmacists' Perspectives On Compounding in Contemporary Pharmacy EducationWiwin WiniartiNo ratings yet

- Eview F Herapeutics: Economic Evaluations of Clinical Pharmacy Services: 2006 - 2010Document23 pagesEview F Herapeutics: Economic Evaluations of Clinical Pharmacy Services: 2006 - 2010Igor SilvaNo ratings yet

- Clinical PharmacyDocument16 pagesClinical Pharmacyfike0% (1)

- 17 - HEPLER, C - D - Clinical Pharmacy, Pharmaceutical Care, and The Quality of Drug TherapyDocument8 pages17 - HEPLER, C - D - Clinical Pharmacy, Pharmaceutical Care, and The Quality of Drug TherapyIndra PratamaNo ratings yet

- Exploring The Knowledge and Attitude of Medical and Pharmacy Students About Generic Medicine in Lahore, PakistanDocument7 pagesExploring The Knowledge and Attitude of Medical and Pharmacy Students About Generic Medicine in Lahore, PakistanMathilda UllyNo ratings yet

- PMNL PcarDocument6 pagesPMNL PcarMA. CORAZON ROSELLE REFORMANo ratings yet

- Unit 3Document15 pagesUnit 3MayMenderoNo ratings yet

- Improving Safety On High-Alert MedicationDocument48 pagesImproving Safety On High-Alert MedicationLenny SucalditoNo ratings yet

- Attitude On Clinical Pharmacy Training: The Case of Haramaya University, EthiopiaDocument8 pagesAttitude On Clinical Pharmacy Training: The Case of Haramaya University, EthiopiaAychluhm TatekNo ratings yet

- Healthcare 08 00143 v2Document14 pagesHealthcare 08 00143 v2lethuydanthuNo ratings yet

- Clinical Drug LiteratureDocument12 pagesClinical Drug LiteratureRaheel AsgharNo ratings yet

- Coursework For PharmacistDocument5 pagesCoursework For Pharmacistafjwrmcuokgtej100% (2)

- Ractice Nsights: The Critical Care Pharmacist: An Essential Intensive Care PractitionerDocument5 pagesRactice Nsights: The Critical Care Pharmacist: An Essential Intensive Care PractitionerDaniela HernandezNo ratings yet

- FPX4020 WilsonChelsea Assessment4 1Document17 pagesFPX4020 WilsonChelsea Assessment4 1FrancisNo ratings yet

- Defining Competencies and Performance Indicators For Physicians in Medical ManagementDocument8 pagesDefining Competencies and Performance Indicators For Physicians in Medical Managementsami_1410No ratings yet

- 1 PDFDocument7 pages1 PDFHayatul IslamiahNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1: Introduction To The Concept of Drug Information: Learning ObjectivesDocument17 pagesChapter 1: Introduction To The Concept of Drug Information: Learning Objectiveskola belloNo ratings yet

- A Medical Outreach Elective CourseDocument11 pagesA Medical Outreach Elective CourseRobert SmithNo ratings yet

- What Is Clinical PharmacyDocument4 pagesWhat Is Clinical PharmacySethiSheikhNo ratings yet

- Scope of Pharmacist Practice J Am Pharm Assoc 2010Document35 pagesScope of Pharmacist Practice J Am Pharm Assoc 2010garcimicNo ratings yet

- Course Outline - 664759538modular Curriculum For Pharmacy Students, September 2013Document357 pagesCourse Outline - 664759538modular Curriculum For Pharmacy Students, September 2013Sebaha TijoNo ratings yet

- Self-Learning Material-2Document3 pagesSelf-Learning Material-2mona salah tag el dinNo ratings yet

- Jurnas Bull2017Document10 pagesJurnas Bull2017miftah zannahNo ratings yet

- Hospital Pharmacology An Alternative Model For Practice and Training in Clinical PharmacologyDocument6 pagesHospital Pharmacology An Alternative Model For Practice and Training in Clinical PharmacologyLuciana OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Clinical Pharmacy - A Definition: Fahad Hussain 9/20/2010Document4 pagesClinical Pharmacy - A Definition: Fahad Hussain 9/20/2010Tawhida Islam100% (1)

- Curriculum Trends in Nurse-MDocument10 pagesCurriculum Trends in Nurse-MmfhfhfNo ratings yet

- Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning: Bobby Jacob, Samuel PeasahDocument6 pagesCurrents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning: Bobby Jacob, Samuel PeasahNorris TadeNo ratings yet

- Multidisciplinary Team and Pharmacists Role in That TeamDocument5 pagesMultidisciplinary Team and Pharmacists Role in That TeamTimothy OgomaNo ratings yet

- 9 Golden Stars PharmacistDocument6 pages9 Golden Stars PharmacistNahwa AzuraNo ratings yet

- A Career Exploration Assignment For First-Year Pharmacy StudentsDocument9 pagesA Career Exploration Assignment For First-Year Pharmacy StudentsYankanagoudaNo ratings yet

- 600e37697a46ec002cbed98a-1611544499-PHARMACY MANAGEMENTDocument13 pages600e37697a46ec002cbed98a-1611544499-PHARMACY MANAGEMENTClarkStewartFaylogaErmilaNo ratings yet

- Making Pharmacogenetic Testing A Reality in A Community PharmacyDocument7 pagesMaking Pharmacogenetic Testing A Reality in A Community PharmacyGodstruthNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Medication Administration ErrorsDocument7 pagesLiterature Review On Medication Administration Errorsea2167raNo ratings yet

- Pharmacy 06 00037Document9 pagesPharmacy 06 00037Rosen AnthonyNo ratings yet

- Content ServerDocument10 pagesContent ServersyarifaNo ratings yet

- Clinical PharmacyDocument2 pagesClinical PharmacySuman DickensNo ratings yet

- MassHealth Pharmacy Program Success Story - DATE-PRINTDocument65 pagesMassHealth Pharmacy Program Success Story - DATE-PRINTIftekhar AhmedNo ratings yet

- Pharmacist Role in Health Care Setting and CommunicationDocument30 pagesPharmacist Role in Health Care Setting and CommunicationDes LumabanNo ratings yet

- Book ReviewsDocument4 pagesBook ReviewsZafran KhanNo ratings yet

- Article - Pharmacists Knowledge On Complementary MedDocument12 pagesArticle - Pharmacists Knowledge On Complementary MedAnonymous EAPbx6No ratings yet

- Teachers' Topics Evaluating The Potential Impact of Pharmacist Counseling On Medication Adherence Using A Simulation ActivityDocument7 pagesTeachers' Topics Evaluating The Potential Impact of Pharmacist Counseling On Medication Adherence Using A Simulation ActivityKayedAhmadNo ratings yet

- 2013 Introduction of Clinical PharmacyDocument18 pages2013 Introduction of Clinical Pharmacyyudi100% (1)

- HPCP Assignment 2Document8 pagesHPCP Assignment 2mokshmshah492001No ratings yet

- Your Guide To A Career in Pharmacy A Comprehensive OverviewFrom EverandYour Guide To A Career in Pharmacy A Comprehensive OverviewNo ratings yet

- Article 6yCODocument14 pagesArticle 6yCOAychluhm TatekNo ratings yet

- Pharmacy Informatics (PHAR 110) : Activity 2Document10 pagesPharmacy Informatics (PHAR 110) : Activity 2Karylle RiveroNo ratings yet

- Clinical Pharmacy: 4 ProfessionalDocument300 pagesClinical Pharmacy: 4 ProfessionalMobeen AhmedNo ratings yet

- Intro To Pharmacy-Chapter3Document4 pagesIntro To Pharmacy-Chapter3nm1006055No ratings yet

- Physician Assistants and Nurse Practitioners in Specialty Care. CALIFORNIA HEALTHCARE FOUNDATIONDocument0 pagesPhysician Assistants and Nurse Practitioners in Specialty Care. CALIFORNIA HEALTHCARE FOUNDATIONJuanPablo OrdovásNo ratings yet

- Pharmacoeconomics Education in WHO Eastern Mediterranean RegionDocument8 pagesPharmacoeconomics Education in WHO Eastern Mediterranean RegionDevanti EkaNo ratings yet

- As ReferenceDocument6 pagesAs Referenceapi-3728683No ratings yet

- Article 23yCODocument11 pagesArticle 23yCOAychluhm TatekNo ratings yet

- FINAL PAPER Duddy-1 PDFDocument93 pagesFINAL PAPER Duddy-1 PDFDonaldo Delvis DuddyNo ratings yet

- ISRC Manager Application Form (Rev 1 25)Document6 pagesISRC Manager Application Form (Rev 1 25)Donaldo Delvis DuddyNo ratings yet

- English Language Teaching in The PeripheDocument29 pagesEnglish Language Teaching in The PeripheDonaldo Delvis DuddyNo ratings yet

- Teaching English To Pharmacy Students: Resources, Importance and ApplicationsDocument14 pagesTeaching English To Pharmacy Students: Resources, Importance and ApplicationsDonaldo Delvis DuddyNo ratings yet

- StudentHandbook Pharmacy CourseDocument96 pagesStudentHandbook Pharmacy CourseDonaldo Delvis DuddyNo ratings yet

- English For Pharmacy: An IntroductionDocument2 pagesEnglish For Pharmacy: An IntroductionDonaldo Delvis DuddyNo ratings yet

- English For PharmacyDocument11 pagesEnglish For PharmacyDonaldo Delvis Duddy100% (1)

- Focused Abdominal Sonography in Trauma (FAST)Document56 pagesFocused Abdominal Sonography in Trauma (FAST)RannyNo ratings yet

- Healthcare Delivery System ProjectDocument2 pagesHealthcare Delivery System Projectapi-534896073No ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument13 pagesCase Studyshakuntla Devi0% (2)

- Doctors ListDocument6 pagesDoctors ListDcStrokerehabNo ratings yet

- Adapted Anatomical Image Criteria For PA Chest RadiographyDocument29 pagesAdapted Anatomical Image Criteria For PA Chest RadiographyDR MUHAMMAD NADEEMNo ratings yet

- De Gruchys Clinical Haematology PDFDocument1 pageDe Gruchys Clinical Haematology PDFShivanshi K0% (1)

- GNM, B.SC (N)Document27 pagesGNM, B.SC (N)REVATHI H KNo ratings yet

- Dalman 222Document7 pagesDalman 222Cyril D. SuazoNo ratings yet

- Satera Gause Annotated BibDocument3 pagesSatera Gause Annotated Bibapi-264107234No ratings yet

- OrifDocument2 pagesOrifGene Edward D. ReyesNo ratings yet

- EMS Alphabet SoupDocument3 pagesEMS Alphabet SoupCourtney0% (1)

- 3 16Document27 pages3 16Iful SaifullahNo ratings yet

- Overactive BladderDocument50 pagesOveractive BladderYaneth AngelNo ratings yet

- BCC 2008Document5 pagesBCC 2008mesNo ratings yet

- IcuDocument8 pagesIcuBikul Nayar100% (1)

- Drug Computations 1Document9 pagesDrug Computations 1Alex Olivar100% (1)

- Online Application PDF File1Document3 pagesOnline Application PDF File1nav2edNo ratings yet

- Newer Insulin in Diabetic Pregnancy - PPT'Document56 pagesNewer Insulin in Diabetic Pregnancy - PPT'Hemamalini100% (1)

- Ankle and FootDocument10 pagesAnkle and FootGlea PavillarNo ratings yet

- Part 2 Oral Examination Process PDFDocument9 pagesPart 2 Oral Examination Process PDFTin SantosNo ratings yet

- Fine Needle Aspiration PDFDocument5 pagesFine Needle Aspiration PDFjkNo ratings yet

- Final Project Vijay EditedDocument67 pagesFinal Project Vijay EditedHemanth KittuNo ratings yet

- Choosing A Wound Dressing Based On Common Wound CharacteristicsDocument11 pagesChoosing A Wound Dressing Based On Common Wound CharacteristicsYolis MirandaNo ratings yet

- Principal Veins and ArteriesDocument5 pagesPrincipal Veins and Arteriesrodz_verNo ratings yet

- Linee Guida Intubazione DifficileDocument51 pagesLinee Guida Intubazione Difficilemarco.mercieriNo ratings yet

- Medidas Pediátricas GastrointestinaisDocument5 pagesMedidas Pediátricas GastrointestinaislftvNo ratings yet

- TS Circ025-2015Document11 pagesTS Circ025-2015zaldusalvaradoNo ratings yet

Curriculum Topics in Pharmacy

Curriculum Topics in Pharmacy

Uploaded by

Donaldo Delvis DuddyOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Curriculum Topics in Pharmacy

Curriculum Topics in Pharmacy

Uploaded by

Donaldo Delvis DuddyCopyright:

Available Formats

Curriculum Topics in Pharmacy Education: Current and Ideal

Emphasis1

David R. Graber, Janis P. Bellack, Carol Lancaster and Catherine Musham

Department of Health Administration and Policy, Medical University of South Carolina, 171 Ashley Avenue, Charleston SC 29425

Jean Nappi

College of Pharmacy, Medical University of South Carolina, 171 Ashley Avenue, Charleston SC 29425

Edward H. O’Neil

University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco CA 94341

This study assessed the current and ideal emphasis for curriculum coverage of 33 generalist curriculum

topics in PharmD programs and evaluated barriers to curriculum change. These topics reflect a wide

range of recommendations for curriculum change in a number of health professions. This study was part

of a larger study of 11 health professions education programs. A 46-item survey using a 5-point scale for-

mat was mailed to the curriculum directors at all U.S. pharmacy schools affiliated with the American

Association of Colleges of Pharmacy that offer the PharmD degree (n=71).The ordinal scores for current

emphasis and ideal emphasis for each of the 33 topics were compared for differences between current

and desired emphasis. The ratings of barriers to curriculum change were also analyzed. The four topics

rated highest for ideal emphasis by pharmacy respondents were “Effective patient-provider relation-

ships/communication,” “Patient teaching/ education,” “Outpatient/ ambulatory care,” and “Use of electron-

ic information systems.” Topics related to community health and health care for the underserved were not

ranked highly for ideal emphasis. The most significant barriers to curriculum reform were “Limited avail-

ability of clinical learning sites” and “An already crowded curriculum”. Responses indicate an awareness

by pharmacy curriculum directors of the need for significant improvements in the coverage of broad, gen-

eralist competencies in the PharmD curriculum. The curriculum directors were most concerned about

increasing the emphasis on “Accountability for cost-effectiveness and patient outcomes,” “Health promo-

tion/disease prevention,” “Population- based health care,” “Managed care,” and “Use of electronic informa-

tion systems.” A movement toward primary and outpatient care and better relationships and communi-

cation between pharmacists and patients were evident in the curriculum directors’ responses.

INTRODUCTION public about drug-related information, and providing pharma-

In the past decade the U.S. health care system has undergone ceutical care in such non-hospital settings as ambulatory care

major change, shifting from a professionally-driven fee-for- and long-term care. Challenges such as the burgeoning elderly

service model to a market-driven managed care model. population who often require complicated drug regimens,

Demographic changes, disease patterns, and rapid advances in changes in the organization and financing of health care,

science and technology have resulted in the use of more drugs demands for cost-effectiveness, the increase in chronic illness,

and more expensive drug delivery systems. Such changes are and continuing advances in information systems and pharma-

challenging those who are responsible for educating the ceutics must be addressed in the pharmacy curriculum as

nation’s future pharmacy practitioners. Because of the rapid well(3).

proliferation of pharmaceutical agents, pharmacy has especial- The Pew Health Professions Commission’s 1993 report(1)

ly felt the impact of these broad system changes. recommended the following changes in the pharmacy curricu-

For nearly a decade, the Pew Health Profession lum: (i) initiate curricular reform that engenders competencies

Commission(1-3) has recommended preparing health profes- essential to pharmaceutical care (e.g., critical thinking, com-

sions students to be more adaptable and better prepared to munication, ethical behavior, teamwork, leadership, and car-

work in different environments and within interdisciplinary ing); (ii) develop systems of peer review and evaluation that

teams. The Commission’s 1993 and 1995 reports(2,3) chal- include documentation and review of care delivered, analysis of

lenged pharmacy schools to prepare graduates for practice in the the outcomes of care, and efforts to ensure the continuing

changing delivery system by refocusing the curriculum

toward such areas as protocol-driven therapies, collaboration 1

This study was supported in part through a grant from the National Fund for

with patients and other health team members about drug thera- Medical Education through the University of California, San Francisco,

py decisions, counseling patients about their drug therapies, Center for the Health Professions. The views expressed in this article do not

monitoring patient responses to drug therapies, educating the necessarily represent the views of the supporting organization.

American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education Vol. 63, Summer 1999 145

quality and effective coordination of care; (iii) develop and appropriately trained pharmacists can make a meaningful dif-

promote a medication-use information system for application ference in the care of patients. A high priority must be assigned

to the ambulatory care setting; and (iv) develop a sufficient to advancing pharmacy education and training.” The concept

number and variety of ambulatory clinical training models and of the pharmacist sharing responsibility for patients’ drug ther-

sites to provide ample educational opportunity for pharmacy apy outcomes became known as pharmaceutical care. The

and other health professional students in the delivery of phar- pharmacist became responsible for drug dispensing as well as

maceutical care. The Commission’s 1995 Critical Challenges monitoring patients’ therapeutic progress, consulting with pre-

report(3) suggested that schools of pharmacy “focus profes- scribers and collaborating with other health professionals on

sional pharmaceutical training even more on issues of clinical behalf of patients.

pharmacy, system management, and working with other health Our study evaluated the importance accorded by academ-

care providers.” ic deans and curriculum directors (of several health professions

Traditionally, pharmacy education has focused on drug educational programs) to 33 curriculum topic areas. Although

products, emphasizing chemistry, pharmaceutics and the con- our survey did not seek to replicate any single report or study,

trol and regulation of drug product delivery systems. The dra- many of the survey topics reflect or are related to the recom-

matically changing health care delivery system and the increas- mendations presented in the Third Strategic Planning

ingly prominent role of pharmaceutical agents in the diagnosis Conference for Pharmacy Practice in the 21st century(5). This

and treatment of disease is shifting this focus to a broader role conference brought practitioners from a wide variety of areas

for pharmacy practitioners. This broader role demands a set of together. A small number of academicians were also invited.

generalist competencies to augment traditional discipline-spe- During this conference, attendees described pharmacy curricu-

cific competencies in order to assure that pharmacy practition- la as being outmoded and unresponsive to pharmacists’ needs.

ers are prepared to practice effectively in the changing envi- Attendees believed that the new PharmD curriculum should

ronment. emphasize skills such as patient assessment, drug therapy man-

In 1989, the President of the American Association of agement, and problem-solving.

Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) formed a Commission to More recently, the Janus Commission of the AACP called

Implement Change. This group re-examined the role of phar- for continuing reform of pharmaceutical education(6). In fact,

maceutical education in relation to the dramatic changes occur- the Commission suggested that the academic pharmacy com-

ring in society and the health care system(4). Following two munity has failed to evolve to meet the current challenges fac-

years of study, the Commission determined that the bachelor’s ing the profession. Pharmaceutical education continues to be

degree in pharmacy would not longer meet the changing needs heavily dominated by a factual, product-based, knowledge-

of the profession and the health care system. Instead, the focused curriculum delivered in traditional classroom lectures.

Commission agreed that the doctoral degree in pharmacy The Commission stressed that the ideal curriculum should

(Doctor of Pharmacy, or PharmD) should become the entry- focus on patient-centered, therapeutic knowledge. Less empha-

level credential for the profession. The program should be at sis should be placed on the pharmacist controlling the supply

least four academic years in length, with at least two years of of the drug product. Instead the pharmacist should coordinate

pre-pharmacy coursework as a foundation for the upper level the drug use process in collaboration with other health profes-

professional curriculum. Although the Commission’s report sionals.

did not offer specific recommendations for change, it did pro- The Janus Commission also recommended that the gradu-

vide general direction. The Commission noted that pharmacists ate of a college of pharmacy be capable of solving problems

of the future would assume greater responsibility for the man- and adapting to changes in health care. The graduate should be

agement of drug therapy in patients. To this end they identified able to contribute to positive health care outcomes through

four major areas of competence: effective medication use and be able to collaborate with

patients, physicians, nurses and other health care practitioners.

• Conceptual competence - Understanding the theoretical The Commission suggested requiring the incorporation of

foundations of the profession, community outreach programs or service learning activities as

• Technical competence - Ability to perform skills required part of the core curriculum. Clearly this would be a major shift

in the profession, from the emphasis on chemistry and drug products as the cor-

• Integrative competence - Ability to meld theory and skills nerstones of the curriculum.

in the practice setting, and Pharmacy students will not be prepared to meet the

Career marketability - Becoming marketable as a result of demands of these new roles without more extensive and inten-

education and training. sive education. In addition to requiring the PharmD degree as

the entry-level credential for pharmacy practice, most pharma-

The Commission also highlighted critical thinking, communi- cy educators advocate that schools and colleges must recon-

cation abilities, aesthetic sensitivity, professional ethics, and ceptualize and reconstruct their curricula so that graduates

adaptability as essential skills for future pharmacists(4). would be prepared to meet the complex challenge of providing

At the same time the Commission was engaged in its pharmaceutical care. While pharmacy education programs

work, the American College of Clinical Pharmacy (ACCP) have expanded the curriculum coverage of pharmacy-specific

submitted comments to the American Council on knowledge and skills, it is not clear to what extent they are also

Pharmaceutical Education (ACPE) regarding the accreditation preparing their students with the broad competencies and skills

standards for pharmacy programs. The ACCP noted, “There needed for practice in an increasingly complex and shifting

will be increasing opportunities and societal mandates for health care system. In addition to assuring that students acquire

pharmacists to take a more responsible role in managing the the knowledge and skills for the practice of pharmacy, they

therapeutic outcomes of patients. It may be years until these must also acquire knowledge and skills to practice pharmacy

opportunities are realized fully on a national basis. However, within the broader health care and social environment.

146 American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education Vol. 63, Summer 1999

Although pharmacy is a unique discipline, many of the were coded for each curriculum director and pharmacy school.

recommendations for the reform of distinct health professions’ After six weeks, a reminder letter and a second copy of the sur-

curricula have described similar skills and competencies as vey were mailed to nonrespondents. Return of a completed sur-

needed by their program graduates. However, the importance vey was considered as the respondent’s consent to participate.

accorded to many of these skills and competencies by educa- In the first section of the survey, the directors were asked

tors has not typically been evaluated or measured to what extent each of the 33 topics: (i) was included in phar-

macy students’ required learning experiences (current empha-

STUDY PURPOSE sis), and (ii) they believed should be included in pharmacy stu-

dents’ required learning experiences (ideal emphasis). For the

The purpose of this study was to determine the extent to which

33 topics, respondents also were requested to circle the three

pharmacy (and ten other health professions) education pro-

topics that they believed “are most important to assure your

grams are responding to contemporary calls for educational

graduates are prepared adequately for practice in the evolving

reform. This study was part of a larger national survey of aca-

health care system.” In the second section of the survey,

demic deans, curriculum directors, or program directors of 11

respondents were asked to what extent they believed 12 differ-

health professions disciplines. The survey measured the extent to

ent factors were a barrier to needed curriculum changes in their

which these academic leaders believed that 33 selected cur-

program. For the 46 scale questions, the five response levels

riculum topics are presently emphasized, and the extent to

ranged from 1 (Not at All) to 5 (To a Great Extent). The scale

which they believe they should be emphasized in the required

contained a clear midpoint; however, the second and fourth

curriculum.

levels were not labeled. It was decided that various possible

The survey was intended to ascertain current and ideal labels were unsatisfactory, and ultimately less intuitively clear

emphasis on selected broad curriculum topics in health profes- than allowing the respondent to infer the level of emphasis.

sions education programs. The selected topic areas are relevant

This survey was not designed to precisely measure the

to a variety of health disciplines; commonalities and differ-

degrees of coverage of any of the topic items. Only general

ences among the health professions groups surveyed were also

estimates of the current and ideal coverage for each topic were

of interest.

sought. Also, a comprehensive evaluation of the amount of

As a group, the pharmacy curriculum directors were coverage for each item was beyond the resources available for

assumed to be familiar with the overall emphasis, coverage, the study. Its principal purposes were to determine which top-

and status accorded the various curriculum topics in their ics the curriculum directors thought needed greater emphasis

respective programs, and the basic competencies that are and to identify those topics with the largest gap between cur-

expected of their graduates. Thus, they were considered the rent and ideal levels of coverage, indicating potential areas in

appropriate target group to survey for the study. which curriculum change may be needed.

METHODS The topics selected were diverse and reflected the many

calls for health professions education reform across the health

A 46-item survey instrument was developed and mailed to the professions. The topics were selected on the basis of literature

curriculum directors at all U.S. schools of pharmacy affiliated reviews, in-depth interviews with academic deans, and the

with the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy views elicited in the preliminary focus groups. The final list of

(n=71). The names of individuals responsible for curricular 33 curriculum topics reflected the wide range of recommenda-

affairs were supplied by this organization. This survey was part tions for curriculum change that have been made in recent

of a larger study of health professions education, with 1,770 years, including those in pharmacy education(1,3,5,6).

surveys mailed to academic deans, program directors, or cur- Primary analyses focused on comparisons of the rankings

riculum directors in 11 disciplines. In addition to pharmacy, the and frequencies of the responses. The current and ideal set of

survey groups included dentistry, undergraduate allopathic responses from the pharmacy curriculum directors were ana-

medicine, undergraduate osteopathic medicine, nurse practi- lyzed with the Wilcoxon Matched Pairs Signed Ranks Test.

tioner, nurse midwife, and physician assistant, as well as four The pharmacy responses were then compared to the responses

generalist medical residency programs: internal medicine, fam- of five of the other surveyed groups using the Mann-Whitney

ily medicine, pediatrics, and obstetrics/gynecology. This paper Test for ordered data. To aid in interpretation a means was

focuses on the pharmacy program findings, which are also computed for each curriculum topic, using 1 to correspond to a

compared with the aggregate responses from the dental, med- response of “not at all” and using 5 for a response of “to a great

ical, nurse practitioner, nurse midwifery, and physician assis- extent” with equal interval values assigned to responses in

tant programs, since these programs are considered to be at between. The 0.05 level of significance was adjusted for the

comparable educational and practice levels, despite some vari- number of comparisons (Bonferroni method).

ations.

QUESTIONNAIRE DEVELOPMENT RESULTS

The survey consisted of 46 questions in five-point scale for- Two separate mailings resulted in the return of 51 surveys, a

mat, and one open-ended question, color-coded by survey response rate of 72 percent. This compared with an overall

group. The Total Design Method(7), which uses a booklet for- study response rate of 55 percent (range 36 to 86 percent). No

mat with an illustrated cover, was employed. The survey was geographic regions were under-represented in the final sample.

developed initially by the research team and revised after con- Table I exhibits means (developed from the ordinal

ducting a focus group with health professions educational scores) for current and ideal emphasis for the 33 curriculum

directors representing the groups to be surveyed. The survey topics. The five topics with the highest ratings for current

was then pilot tested with a group of academic deans and cur- emphasis were “Effective patient-provider relationships/com-

riculum directors, further revised, and subsequently mailed, munication”(3.82), “Patient teaching/education” (3.63),

with a cover and an assurance of confidentiality. The surveys “Tertiary/quaternary care” (3.49), “Outpatient/ambulatory

American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education Vol. 63, Summer 1999 147

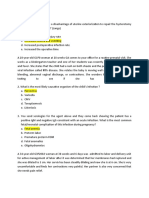

Table I. Mean ratings of current and ideal emphasis for 33 curriculum topics: Ranked by ideal emphasis

Mean

Curriculum topic Current emphasis Ideal emphasis

1. Effective patient-provider relationships/communication 3.82 4.62*

2. Patient teaching/education 3.63 4.47*

3. Outpatient/ambulatory care 3.45 4.41*

4. Use of electronic information systems 3.08 4.41*

5. Primary care 3.16 4.36*

6. Care of the elderly 3.26 4.28*

7. Professional values 3.38 4.26*

8. Accountability for cost-effectiveness & patient outcomes 2.66 4.26*

9. Interdisciplinary teamwork 3.08 4.26*

10. Managed care 2.88 4.25*

11. Health promotion/disease prevention 2.76 4.20*

12. Case management 3.02 4.20*

13. Patients as partners in health care 3.02 4.14*

14. Clinical practice guidelines 3.19 4.12*

15. Long-term/chronic illness care 3.18 3.96*

16. Health care economics/financing 2.94 3.92*

17. Understanding & utilizing research findings 3.00 3.88*

18. Home health care 2.63 3.86*

19. Biomedical/health care ethics 3.00 3.80*

20. Continuous quality improvement 2.69 3.80*

21. Health care policy 2.82 3.73*

22. Health care organization & administration 3.14 3.71*

23. Legal aspects of health care 3.43 3.61

24. Business management of practice 2.98 3.56*

25. Epidemiology 2.43 3.45*

26. Psychosocial care 2.57 3.43*

27. Population-based care 2.00 3.38*

28. Community social problems 2.37 3.33*

29. Care for underserved patient/populations 2.33 3.33*

30. Cultural differences 2.22 3.25*

31. Communities as partners in health care 2.12 3.23*

32. Tertiary/quaternary care 3.49 3.16

33. Environmental health 2.00 2.83*

*Difference significant at 0.05 level, Wilcoxon Matched Pairs Signed Ranks Test. Responses were on a five-point scale (1=not at all, 5=to a great extent).

Table II. Topics listed most often by curriculum Table III. Mean rating of 12 barriers to pharmacy

directors school curriculum changes

Percent of Factor Mean ratinga

No. times respondent 1. Limited availability of clinical learning sites 3.70

Curriculum topic listed deans 2. Already crowded curriculum 3.67

1. Effective patient-provider relation- 3. Inadequate funding 3.66

ships/communication 18 51.4 4. Professional “turf” issues 3.30

2. Accountability for cost-effect- 5. Faculty resistance 3.22

iveness and patient outcomes 13 37.1 6. Lack of faculty expertise 2.76

3. Primary care 9 25.7 7. Professional accreditation criteria 2.29

4. Managed care 8 22.9 8. Administration resistance 2.29

5. Outpatient/ambulatory care 6 17.1 9. Scheduling conflicts 2.22

6. Patient teaching/education 6 17.1 10. Student resistance 2.20

7. Health promotion-disease 11. Professional licensing requirements 2.12

prevention 5 14.3 12. Community resistance 1.84

8. Professional values 5 14.3 a

Responses were on a five-point scale (1 =not at all, 5=to a great extent).

9. Long term/chronic illness care 5 14.3

10. Health care economics/financing 5 14.3

“Outpatient/ambulatory care” (4.41), “Use of electronic infor-

mation systems” (4.41), and “Primary care” (4.36). For ideal

care” (3.45), and “Legal aspects of health care” (3.43). None of

emphasis, fourteen of the topics were rated above 4.00, and

the topics was rated higher than 3.82 for current emphasis, and

only one—”Environmental health”—was rated below the scale

nearly half (16; 48 percent) were rated below the scale mid-

midpoint of 3.00.

point (3.00). The five topics with the highest ratings for ideal

emphasis were “Effective patient-provider relationships/com- Only two of the topics’ ideal emphasis were not signifi-

munication” (4.62), “Patient teaching/education” (4.47), cantly different from the current emphasis (at the 0.05 level)

using the Wilcoxon Matched Pairs Signed Ranks Test. These

148 American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education Vol. 63, Summer 1999

Table IV. Mean ratings and ranking for ideal emphasis: Pharmacy and five health professions academic deans

Five health

Pharmacy (n=51) professions (n=289)

Curriculum topic Mean score Rank Mean score Rank

1. Effective patient-provider relationships/communication 4.62 1 4.58 2

2. Patient teaching/education 4.47 2 4.29 6

3. Outpatient/ambulatory care 4.41 3 4.49 4

4. Use of electronic information systems 4.41 4 4.20 9

5. Primary care 4.36 5 4.54 3

6. Care of the elderly 4.28 6 3.94 19

7. Professional values 4.26 7 4.38 5

8. Accountability for cost-effectiveness & patient outcomes 4.26 8 4.04 17

9. Interdisciplinary teamwork 4.26 9 4.23 8

10. Managed care 4.25 10 3.79 23

11. Health promotion/disease prevention 4.20 11 4.63* 1

12. Case management 4.20 12 3.97 18

13. Patients as partners in health care 4.14 13 4.28 7

14. Clinical practice guidelines 4.12 14 4.05 16

15. Long-term/chronic illness care 3.96 15 3.50 29

16. Health care economics/financing 3.92 16 3.56 27

17. Understanding & utilizing research findings 3.88 17 4.16 10

18. Home health care 3.86 18 3.25* 32

19. Biomedical/health care ethics 3.80 19 4.14 11

20. Continuous quality improvement 3.80 20 3.84 22

21. Health care policy 3.73 21 3.67 26

22. Health care organization & administration 3.71 22 3.48 30

23. Legal aspects of health care 3.61 23 3.71 25

24. Business management of practice 3.56 24 3.39 31

25. Epidemiology 3.45 25 3.87* 21

26. Psychosocial care 3.43 26 4.11* 13

27. Population-based care 3.38 27 3.78 24

28. Community social problems 3.33 28 4.10* 14

29. Care for underserved patient/populations 3.33 29 4.13* 12

30. Cultural differences 3.25 30 4.06* 15

31. Communities as partners in health care 3.23 31 3.91* 20

32. Tertiary/quaternary care 3.16 32 2.97 33

33. Environmental health 2.83 33 3.53* 28

a

The five health professions or schools are dental, medicine, physician assistant, nurse practitioner, and nurse midwife.

*Difference significant at .05 level, Mann-Whitney Test. Responses were on a five-point scale (1=not at all, 5=to a great extent).

topics were “Legal aspects of health care” and “Tertiary/qua- outcomes,” and “Primary care.” However, only 35 of the 51

ternary care.” respondents circled items as requested. Therefore, these results

As a group, the pharmacy curriculum directors rated may not be representative of the views of the full sample.

eleven of the topics lower than any other survey group for cur- The curriculum directors were queried as to what extent

rent emphasis, and six lower for ideal emphasis. However, they each of 12 listed factors would be a barrier to needed curricu-

also rated two topics—”Managed care” and “Health care eco- lum changes. Table III shows the curriculum directors’ ratings

nomics/financing”—highest among the survey groups for ideal of barriers to curriculum change. “Limited availability of clin-

emphasis. ical learning sites” (3.70), “An already crowded curriculum”

All of the topics except “Tertiary/quaternary care” (3.67), and “Inadequate funding” (3.66) were considered, on

increased in perceived emphasis from current to ideal. The rat- average, the three most significant barriers to curriculum

ings for sixteen topics increased approximately one full level reform. Internal issues—”Professional ‘turf issues,” “Faculty

or more (from current to ideal emphasis), more than any other resistance,” and “Lack of faculty expertise”—were rated next

group surveyed. That is, none of the other surveyed disciplines highest as barriers to change.

indicated the need for substantial increases in emphasis for as Table IV compares the ratings of the 33 topic items by the

many curriculum topics as did the pharmacy curriculum direc- pharmacy curriculum directors and the academic deans or cur-

tors. riculum directors of the five other health professions disci-

Table II highlights the topics circled most often as most plines that were surveyed. There were 289 responses from

important by the pharmacy curriculum directors as “Most these five disciplines (i.e., physician assistant, undergraduate

important to assure that your graduates are prepared adequate- allopathic medicine, dentistry, nurse midwifery, and nurse

ly for practice in the evolving health care system.” The cur- practitioner). The Mann-Whitney Test indicated that eight top-

riculum directors were asked to circle three curriculum topics ics (Figure 1) were considered significantly more important to

in response to this statement. The most frequently indicated the five disciplines (as a group) than the pharmacy educators

items were “Effective patient-provider relationships / commu- (P < 0.05).

nication,” “Accountability for cost-effectiveness and patient “Home health care” was the only item rated higher in ideal

American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education Vol. 63, Summer 1999 149

Barriers to Curriculum Change

One of the greatest challenges recognized by pharmacy

educators is in the transition from a “passive, c la s sroo m/le c-

tur e-based approach” to an “active, experiential-based

approach” to learning. Limited availability of clinical learning

sites is ranked as the greatest barrier. One likely contributor to

this is the increased number of clinical rotations in the Doctor of

Pharmacy program (typically eight to ten months) compared to

the baccalaureate program (typically three to five months). A

second contributor may be the need to find sites where the

emphasis is on direct patient care activities and patient moni-

toring, with less emphasis on drug dispensing. For most

schools, entry level Doctor of Pharmacy programs are much

larger than the post-BS Doctor of Pharmacy program leading to

an increased number of students requiring these types of

experiences. It is not unusual to find that the number of need-

ed rotation sites has increased from four- to ten-fold. The num-

Fig. 1. Topics. ber of available qualified preceptors, who are willing to take

emphasis by the pharmacy curriculum directors (than the five students, is a serious limitation.

health professions educators) that was also significantly differ- The second most commonly cited barrier to change is an

ent. However, Table IV reveals a number of other topics with already crowded curriculum. Although the entry level Doctor of

considerable disparity in rank. Considering the relative ranking Pharmacy curriculum has been expanded to four years, most of

of the topics, the pharmacy curriculum directors considered the additional time has been set aside for experiential lea rn-

“Use of electronic information systems,” “Care of the elderly,” ing . The continuing explosion of knowledge and literature

“Accountability for cost-effectiveness and patient outcomes,” regarding new drugs and delivery systems puts a strain on the

“Long-term chronic illness care,” and “Managed care” to be current time allotted for didactic sessions. In addition, new

more important for coverage than did the comparison group. areas, such as communication skills, information management,

The latter (in aggregate) ranked “Health promotion/ disease pharmacoeconomics, and drug assessment in patient care sys-

prevention” first in ideal emphasis (4.63), while pharmacists tems have become important.

ranked this item somewhat lower at eleventh place (4.20). The The issue of inadequate funding was also considered a

other groups also indicated that greater coverage of major barrier to curriculum change in pharmacy curricula.

“Understanding and utilizing research findings,” “Community Many schools have instituted the new curriculum with little

social problems,” “Communities as partners in health care,” additional financial support. The new learning experiences will

“Care for underserved patients/populations,” and “Cultural dif- require small group discussions and experiential training (i.e.,

ferences” was needed; considerably less support for these top- smaller student to faculty ratios), and also more computers and

ics was evident in the pharmacy curriculum directors’ rankings. classrooms that are equipped with technology to allow distance

learning and internet access. It is expensive to transform older

DISCUSSION classrooms into contemporary classrooms. In many areas of

Prior to commenting on the key findings of this survey, sever- the country, colleges pay preceptors for students doing clerk-

al survey limitations should be noted. First, while curriculum ships and with more clerkships in the curriculum, there is

directors are a key group with considerable influence on and added cost.

knowledge of curriculum issues, they are not solely responsi- Professional “turf issues and faculty resistance are two

ble for curriculum development. Secondly, in order to enhance areas that may overlap to some degree. Some colleges are

compliance, the survey was designed to be brief and easy to attempting to integrate basic science courses and clinical ther-

complete. Therefore, detailed demographic questions and dif- apeutics. This obviously requires time and effort to coordinate

ferences between pharmacy schools were not explored. The different material and possibly different teaching styles into

curriculum topics included in this survey, in general, do not one course. When single instructor courses are changed into

represent many of the basic science or clinical content areas of courses that are taught by teams, numerous problems often

pharmacy education. Instead, this survey was intended to eval- arise.

uate those competencies and curriculum topics that have been

consistently identified as critical to the preparation of future Curriculum Topic Areas

health care professionals, irrespective of discipline. Also, even Some of the recommendations of the Janus Commission

the broad competencies and curriculum topics may vary some noted earlier are obviously supported by the pharmacy curricu-

from discipline to discipline. For example, “Environmental lum directors. Respondents considered “Effective patient-

health” was more relevant to program directors in medicine provider relationships/ communication” and “Patient teach-

and nursing, but clearly less relevant to the pharmacy curricu- ing/education” to be the most important topics for ideal empha-

lum directors. sis. “Interdisciplinary teamwork” and “Patients as partners in

This survey focused on the knowledge, skills, and values health care” also received relatively high ratings.

needed in the education of future health care professionals, and The findings also indicate that curriculum directors who

did not attempt to address teaching methods, faculty develop- responded to this survey share similar views with participants

ment, or organizational factors to improve pharmacy educa- in the Third Strategic Planning Conference on Pharmacy

tion. Despite these limitations, the survey results help broaden Practice in the 21st Century with regard to emphasizing need-

our understanding of future directions for pharmacy education ed curriculum improvements. Compared to the other disci-

150 American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education Vol. 63, Summer 1999

plines that were surveyed, the pharmacy respondents indicated issues is often considered a corollary to the growth of health

the need for a greater degree of increased emphasis on nearly networks or systems. However, this study suggests there is cur-

half of the study topics. The fact that pharmacy responders to rently a greater separation of pharmacy (compared to many

this survey differed from other health professions (in rating other disciplines) from these emerging systems of care that are so

more areas in need of a substantial increase) may suggest that profoundly influencing the practice and education o f physi-

pharmacy education has not kept up with other professions in c ian s and other health professionals. The curriculum directors

responding to the perceived needs of the health care system considered “Managed care” to be an important topic. However, a

and their students. However, another explanation is that since lack of emphasis on broader community and population

many pharmacy curriculum directors have been involved in issues may leave pharmacists at a disadvantage (compared to

comprehensive curriculum change and also in initiating the other health practitioners) as pharmacy is increasingly drawn

entry level PharmD program, they have been especially aware of into the vortex of managed systems of care.

the deficiencies of their programs in their efforts to improve The pharmacy curriculum directors indicated that every

pharmacy education. item except “Tertiary/quaternary care” was worthy of addi-

Another area that has been cited as being less than ade- tional curricular coverage. They also indicated that “An

quate in the curricula of many schools of pharmacy is that of already crowded curriculum” and “Professional ‘turf issues”

technology(8). Very few schools of pharmacy offer courses in are major obstacles to needed curriculum change. In spite of

medical informatics or information science. Yet given the this, many pharmacy programs have been successful in

amount of information available, computer literacy and exper- restructuring their curricula in recent years. However, for cur-

tise in searching medical databases and managing large vol- ricula to continue to develop and be responsive to societal

umes of scientific and patient information are essential in changes, honest self-evaluation, as well as concerted efforts,

today’s workplace. “Use of electronic information systems” will both be essential.

was ranked higher for ideal emphasis by the pharmacy educa-

Am. J. Pharm. Educ., 63, 145-151(1999) received 6/29/98, accepted 2/15/99.

tors than by the other surveyed disciplines. This indicates an

awareness of the critical importance of information systems to References

pharmacy practice and an awareness that substantially greater (1) Shugars, D.A., O’Neil, E.H. and Bader, J.D., Healthy America:

coverage is warranted. Practitioners for 2005, Pew Health Professions Commission, Durham

Given that pharmacists are often described as being one of NC (1991).

(2) O’Neil E.H., Health Professions Education for the Future: Schools in

the most accessible health care professionals, it is somewhat Service to the Nation, Pew Health Professions Commission, San

surprising that “Community social problems,” “Care for under- Francisco CA(1993).

served patients/populations,” “Communities as partners in (3) Pew Health Professions Commission, Critical Challenges: Revitalizing

health care,” and “Cultural differences” were not rated higher. the Health Professions for the 21st Century, UCSF Center for the Health

Perhaps because pharmacists are often located in drugstores in Professions, San Francisco CA (1995).

(4) Papers from the Commission to Implement Change, Am. J. Pharm.

a variety of communities, academicians may feel that these Educ., 57, 366-399(1993).

areas are adequately addressed in the curriculum through com- (5) The Third Strategic Planning Conference for Pharmacy Practice, Am. J.

munity externship experiences. However, less indulgent expla- Hlth.-System Pharmacy, 52, 2217-2223(1995).

nations may be more realistic. Considering all of the items that (6) Bootman, J.L., Hunter, R.H., Kerr, R.A., Lipton, H.L., Mauger, J.A. and

Roche, V.F., “Approaching the Millennium. The report of the AACP

describe a community orientation or social/cultural conscious- Janus Commission,” Am. J. Pharm. Educ., 61, 4S-10S(1997).

ness, pharmacy scores were in aggregate lower than any of the (7) Bootman, J.L., Hunter, R.H., Kerr, R.A. et al., Dillman, D.A., Mail and

other surveyed disciplines. These finding suggest that the Janus Telephone Surveys: The Total Design Method, John Wiley & Sons, New

Commission’s recommendations for increasing community York NY(1978).

involvement are warranted and may not be realized in the near (8) Vecchione, A., Pharmacy schools found wanting in their training on tech-

nology, Technology and Pharmacy, 22S-23S, (Special Supplement to

future. A greater focus on community and population health Drug Topics, September 15, 1997).

American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education Vol. 63, Summer 1999 151

You might also like

- Mind Maps in MedicineDocument159 pagesMind Maps in MedicineAnonymous jSTkQVC27b100% (44)

- Nursing Care Plan ON: Caesarean DeliveryDocument22 pagesNursing Care Plan ON: Caesarean DeliveryKavi rajput79% (14)

- Clinical PharmacyDocument16 pagesClinical Pharmacyblossoms_diyya299850% (6)

- Clinical Pharmacist in ICUDocument26 pagesClinical Pharmacist in ICUCosmina GeorgianaNo ratings yet

- NICU Bereavement Care and Follow-Up Support For Families and StaffDocument10 pagesNICU Bereavement Care and Follow-Up Support For Families and StaffEduardo Rios DuboisNo ratings yet

- Pharmacists' Role in The Healthcare System: January 2006Document9 pagesPharmacists' Role in The Healthcare System: January 2006Anca IacobNo ratings yet

- Pharmacy and Its Paradigm ShiftDocument4 pagesPharmacy and Its Paradigm ShiftKristel Keith NievaNo ratings yet

- Pharmacist Role in Health Care SystemDocument8 pagesPharmacist Role in Health Care SystemLoo Soo WeiNo ratings yet

- DR - Ismail HamedDocument25 pagesDR - Ismail HamedHanan AhmedNo ratings yet

- AMA Sample PaperDocument6 pagesAMA Sample PaperfmrashedNo ratings yet

- Clinical Pharmacy ReviewDocument8 pagesClinical Pharmacy Reviewsagar dhakalNo ratings yet

- Research Articles Independent Community Pharmacists' Perspectives On Compounding in Contemporary Pharmacy EducationDocument8 pagesResearch Articles Independent Community Pharmacists' Perspectives On Compounding in Contemporary Pharmacy EducationWiwin WiniartiNo ratings yet

- Eview F Herapeutics: Economic Evaluations of Clinical Pharmacy Services: 2006 - 2010Document23 pagesEview F Herapeutics: Economic Evaluations of Clinical Pharmacy Services: 2006 - 2010Igor SilvaNo ratings yet

- Clinical PharmacyDocument16 pagesClinical Pharmacyfike0% (1)

- 17 - HEPLER, C - D - Clinical Pharmacy, Pharmaceutical Care, and The Quality of Drug TherapyDocument8 pages17 - HEPLER, C - D - Clinical Pharmacy, Pharmaceutical Care, and The Quality of Drug TherapyIndra PratamaNo ratings yet

- Exploring The Knowledge and Attitude of Medical and Pharmacy Students About Generic Medicine in Lahore, PakistanDocument7 pagesExploring The Knowledge and Attitude of Medical and Pharmacy Students About Generic Medicine in Lahore, PakistanMathilda UllyNo ratings yet

- PMNL PcarDocument6 pagesPMNL PcarMA. CORAZON ROSELLE REFORMANo ratings yet

- Unit 3Document15 pagesUnit 3MayMenderoNo ratings yet

- Improving Safety On High-Alert MedicationDocument48 pagesImproving Safety On High-Alert MedicationLenny SucalditoNo ratings yet

- Attitude On Clinical Pharmacy Training: The Case of Haramaya University, EthiopiaDocument8 pagesAttitude On Clinical Pharmacy Training: The Case of Haramaya University, EthiopiaAychluhm TatekNo ratings yet

- Healthcare 08 00143 v2Document14 pagesHealthcare 08 00143 v2lethuydanthuNo ratings yet

- Clinical Drug LiteratureDocument12 pagesClinical Drug LiteratureRaheel AsgharNo ratings yet

- Coursework For PharmacistDocument5 pagesCoursework For Pharmacistafjwrmcuokgtej100% (2)

- Ractice Nsights: The Critical Care Pharmacist: An Essential Intensive Care PractitionerDocument5 pagesRactice Nsights: The Critical Care Pharmacist: An Essential Intensive Care PractitionerDaniela HernandezNo ratings yet

- FPX4020 WilsonChelsea Assessment4 1Document17 pagesFPX4020 WilsonChelsea Assessment4 1FrancisNo ratings yet

- Defining Competencies and Performance Indicators For Physicians in Medical ManagementDocument8 pagesDefining Competencies and Performance Indicators For Physicians in Medical Managementsami_1410No ratings yet

- 1 PDFDocument7 pages1 PDFHayatul IslamiahNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1: Introduction To The Concept of Drug Information: Learning ObjectivesDocument17 pagesChapter 1: Introduction To The Concept of Drug Information: Learning Objectiveskola belloNo ratings yet

- A Medical Outreach Elective CourseDocument11 pagesA Medical Outreach Elective CourseRobert SmithNo ratings yet

- What Is Clinical PharmacyDocument4 pagesWhat Is Clinical PharmacySethiSheikhNo ratings yet

- Scope of Pharmacist Practice J Am Pharm Assoc 2010Document35 pagesScope of Pharmacist Practice J Am Pharm Assoc 2010garcimicNo ratings yet

- Course Outline - 664759538modular Curriculum For Pharmacy Students, September 2013Document357 pagesCourse Outline - 664759538modular Curriculum For Pharmacy Students, September 2013Sebaha TijoNo ratings yet

- Self-Learning Material-2Document3 pagesSelf-Learning Material-2mona salah tag el dinNo ratings yet

- Jurnas Bull2017Document10 pagesJurnas Bull2017miftah zannahNo ratings yet

- Hospital Pharmacology An Alternative Model For Practice and Training in Clinical PharmacologyDocument6 pagesHospital Pharmacology An Alternative Model For Practice and Training in Clinical PharmacologyLuciana OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Clinical Pharmacy - A Definition: Fahad Hussain 9/20/2010Document4 pagesClinical Pharmacy - A Definition: Fahad Hussain 9/20/2010Tawhida Islam100% (1)

- Curriculum Trends in Nurse-MDocument10 pagesCurriculum Trends in Nurse-MmfhfhfNo ratings yet

- Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning: Bobby Jacob, Samuel PeasahDocument6 pagesCurrents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning: Bobby Jacob, Samuel PeasahNorris TadeNo ratings yet

- Multidisciplinary Team and Pharmacists Role in That TeamDocument5 pagesMultidisciplinary Team and Pharmacists Role in That TeamTimothy OgomaNo ratings yet

- 9 Golden Stars PharmacistDocument6 pages9 Golden Stars PharmacistNahwa AzuraNo ratings yet

- A Career Exploration Assignment For First-Year Pharmacy StudentsDocument9 pagesA Career Exploration Assignment For First-Year Pharmacy StudentsYankanagoudaNo ratings yet

- 600e37697a46ec002cbed98a-1611544499-PHARMACY MANAGEMENTDocument13 pages600e37697a46ec002cbed98a-1611544499-PHARMACY MANAGEMENTClarkStewartFaylogaErmilaNo ratings yet

- Making Pharmacogenetic Testing A Reality in A Community PharmacyDocument7 pagesMaking Pharmacogenetic Testing A Reality in A Community PharmacyGodstruthNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Medication Administration ErrorsDocument7 pagesLiterature Review On Medication Administration Errorsea2167raNo ratings yet

- Pharmacy 06 00037Document9 pagesPharmacy 06 00037Rosen AnthonyNo ratings yet

- Content ServerDocument10 pagesContent ServersyarifaNo ratings yet

- Clinical PharmacyDocument2 pagesClinical PharmacySuman DickensNo ratings yet

- MassHealth Pharmacy Program Success Story - DATE-PRINTDocument65 pagesMassHealth Pharmacy Program Success Story - DATE-PRINTIftekhar AhmedNo ratings yet

- Pharmacist Role in Health Care Setting and CommunicationDocument30 pagesPharmacist Role in Health Care Setting and CommunicationDes LumabanNo ratings yet

- Book ReviewsDocument4 pagesBook ReviewsZafran KhanNo ratings yet

- Article - Pharmacists Knowledge On Complementary MedDocument12 pagesArticle - Pharmacists Knowledge On Complementary MedAnonymous EAPbx6No ratings yet

- Teachers' Topics Evaluating The Potential Impact of Pharmacist Counseling On Medication Adherence Using A Simulation ActivityDocument7 pagesTeachers' Topics Evaluating The Potential Impact of Pharmacist Counseling On Medication Adherence Using A Simulation ActivityKayedAhmadNo ratings yet

- 2013 Introduction of Clinical PharmacyDocument18 pages2013 Introduction of Clinical Pharmacyyudi100% (1)

- HPCP Assignment 2Document8 pagesHPCP Assignment 2mokshmshah492001No ratings yet

- Your Guide To A Career in Pharmacy A Comprehensive OverviewFrom EverandYour Guide To A Career in Pharmacy A Comprehensive OverviewNo ratings yet

- Article 6yCODocument14 pagesArticle 6yCOAychluhm TatekNo ratings yet

- Pharmacy Informatics (PHAR 110) : Activity 2Document10 pagesPharmacy Informatics (PHAR 110) : Activity 2Karylle RiveroNo ratings yet

- Clinical Pharmacy: 4 ProfessionalDocument300 pagesClinical Pharmacy: 4 ProfessionalMobeen AhmedNo ratings yet

- Intro To Pharmacy-Chapter3Document4 pagesIntro To Pharmacy-Chapter3nm1006055No ratings yet

- Physician Assistants and Nurse Practitioners in Specialty Care. CALIFORNIA HEALTHCARE FOUNDATIONDocument0 pagesPhysician Assistants and Nurse Practitioners in Specialty Care. CALIFORNIA HEALTHCARE FOUNDATIONJuanPablo OrdovásNo ratings yet

- Pharmacoeconomics Education in WHO Eastern Mediterranean RegionDocument8 pagesPharmacoeconomics Education in WHO Eastern Mediterranean RegionDevanti EkaNo ratings yet

- As ReferenceDocument6 pagesAs Referenceapi-3728683No ratings yet

- Article 23yCODocument11 pagesArticle 23yCOAychluhm TatekNo ratings yet

- FINAL PAPER Duddy-1 PDFDocument93 pagesFINAL PAPER Duddy-1 PDFDonaldo Delvis DuddyNo ratings yet

- ISRC Manager Application Form (Rev 1 25)Document6 pagesISRC Manager Application Form (Rev 1 25)Donaldo Delvis DuddyNo ratings yet

- English Language Teaching in The PeripheDocument29 pagesEnglish Language Teaching in The PeripheDonaldo Delvis DuddyNo ratings yet

- Teaching English To Pharmacy Students: Resources, Importance and ApplicationsDocument14 pagesTeaching English To Pharmacy Students: Resources, Importance and ApplicationsDonaldo Delvis DuddyNo ratings yet

- StudentHandbook Pharmacy CourseDocument96 pagesStudentHandbook Pharmacy CourseDonaldo Delvis DuddyNo ratings yet

- English For Pharmacy: An IntroductionDocument2 pagesEnglish For Pharmacy: An IntroductionDonaldo Delvis DuddyNo ratings yet

- English For PharmacyDocument11 pagesEnglish For PharmacyDonaldo Delvis Duddy100% (1)

- Focused Abdominal Sonography in Trauma (FAST)Document56 pagesFocused Abdominal Sonography in Trauma (FAST)RannyNo ratings yet

- Healthcare Delivery System ProjectDocument2 pagesHealthcare Delivery System Projectapi-534896073No ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument13 pagesCase Studyshakuntla Devi0% (2)

- Doctors ListDocument6 pagesDoctors ListDcStrokerehabNo ratings yet

- Adapted Anatomical Image Criteria For PA Chest RadiographyDocument29 pagesAdapted Anatomical Image Criteria For PA Chest RadiographyDR MUHAMMAD NADEEMNo ratings yet

- De Gruchys Clinical Haematology PDFDocument1 pageDe Gruchys Clinical Haematology PDFShivanshi K0% (1)

- GNM, B.SC (N)Document27 pagesGNM, B.SC (N)REVATHI H KNo ratings yet

- Dalman 222Document7 pagesDalman 222Cyril D. SuazoNo ratings yet

- Satera Gause Annotated BibDocument3 pagesSatera Gause Annotated Bibapi-264107234No ratings yet

- OrifDocument2 pagesOrifGene Edward D. ReyesNo ratings yet

- EMS Alphabet SoupDocument3 pagesEMS Alphabet SoupCourtney0% (1)

- 3 16Document27 pages3 16Iful SaifullahNo ratings yet

- Overactive BladderDocument50 pagesOveractive BladderYaneth AngelNo ratings yet

- BCC 2008Document5 pagesBCC 2008mesNo ratings yet

- IcuDocument8 pagesIcuBikul Nayar100% (1)

- Drug Computations 1Document9 pagesDrug Computations 1Alex Olivar100% (1)

- Online Application PDF File1Document3 pagesOnline Application PDF File1nav2edNo ratings yet

- Newer Insulin in Diabetic Pregnancy - PPT'Document56 pagesNewer Insulin in Diabetic Pregnancy - PPT'Hemamalini100% (1)

- Ankle and FootDocument10 pagesAnkle and FootGlea PavillarNo ratings yet

- Part 2 Oral Examination Process PDFDocument9 pagesPart 2 Oral Examination Process PDFTin SantosNo ratings yet

- Fine Needle Aspiration PDFDocument5 pagesFine Needle Aspiration PDFjkNo ratings yet

- Final Project Vijay EditedDocument67 pagesFinal Project Vijay EditedHemanth KittuNo ratings yet

- Choosing A Wound Dressing Based On Common Wound CharacteristicsDocument11 pagesChoosing A Wound Dressing Based On Common Wound CharacteristicsYolis MirandaNo ratings yet

- Principal Veins and ArteriesDocument5 pagesPrincipal Veins and Arteriesrodz_verNo ratings yet

- Linee Guida Intubazione DifficileDocument51 pagesLinee Guida Intubazione Difficilemarco.mercieriNo ratings yet

- Medidas Pediátricas GastrointestinaisDocument5 pagesMedidas Pediátricas GastrointestinaislftvNo ratings yet

- TS Circ025-2015Document11 pagesTS Circ025-2015zaldusalvaradoNo ratings yet