Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Nterview NO With Ierre Enry

Nterview NO With Ierre Enry

Uploaded by

Danilo Pires LucioOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Nterview NO With Ierre Enry

Nterview NO With Ierre Enry

Uploaded by

Danilo Pires LucioCopyright:

Available Formats

INTERVIEW NO.

1 WITH PIERRE HENRY

This interview and text are by Ios Smolders, and originally appeared in issue 44 of

Vital magazine, in 1995. This version has been slightly edited by Brian Duguid;

some quotes by Ios, Henry and Michel Chion have been altered to make them read

better in English.

For years the list of people who I wanted to interview was headed by

Pierre Henry. Together with Pierre Schaeffer, Henry was one of the

founding fathers of musique concrète. He was especially interesting to me

because after an initial close relationship with the "official teachings" of

musique concrète Henry chose his own path. Having left the Groupe de

Recherches Musicales (G.R.M.), Henry successfully set up his own studio

and pursued his own career. His latest release is L'Homme a le Camera,

based on the film by Dziga Vertov with the same title. For this interview

the questions were faxed to M. Henry. For his answers he set up a little sketch, his assistant

assuming the role of interviewer. This fake interview was recorded and the tape returned.

THE COMPOSER: PIERRE HENRY

After your musical training you started to investigate the nature of sounds. When was that

and why?

Why did I suddenly want to start to work with a new musical universe? This was at

practically the end of my formal musical studies. I have said it many times and I will

tell it again now: I started to listen to the world around me, outside and in my parents'

garden, inside the house where I had started my musical studies at the piano and

vocal scales. Well, all of it must have been due to my fondness for noises. I had

started my career as a percussionist quite early, beating on anything around me;

furniture, the tables, the drums. I arrived at the moment of creating a noise, and went

on to create something entirely new, an unheard sound that was much more complex

and extraordinary. At the beginning I wanted very much to create something strange.

Henry loved the theatrical presentation of music, admiring Wagner for example. He also became an

ardent admirer of the ballet of Maurice Bejart. With Bejart's group Henry travelled the world as

sound engineer. He also composed many works for ballet. La Messe Pour Le Temps Present became

a very popular piece of music that was scored for ballet. He expressed this fondness for dramatic

theatre in compositions, staged in large halls, that had the atmosphere of (pagan?) masses, lasting

at least three hours without a break.

In the 60s you worked with the rock group Spooky Tooth on Ceremony. Why was that?

The reason for this was much more commercial than artistic. The great success of La

Messe Pour Le Temps Present and Les Jerks Electroniques with Michel Colombier

gave my editor at Philips the idea that I should work together with an English group

to make a thematic album, based on the idea of the Mass. When this started, I didn't

know these people at all, and I accepted for a number of reasons which would not

interest me now, but to me this enterprise was totally without any result for years. I

am planning a new work with a rock group, but I can't say anything about that now.

Two interviews with Pierre Henry pg. 1 of 15

Henry went to London to supervise the recordings. He brought the tapes home and began the

editing process. "He didn't like the heavy basses and the voice drowned in reverb, so he composed a

sort of counterpart Ceremony II. This work is a myriad of little additional movements based on

concrete sounds, beaten tam-tams, carillons, forming little pagan rites for an imaginary savage

religion." (Michel Chion). Perhaps that shows how Henry looks at pop music; a pagan ritual.

Were you interested in the popular side of electronic music?

To me that is not a big deal, because my music has never been truly electronic. It's

music for tape, an electro-acoustic music. It leaves me a bit cold. A creator does not

search for immediate success.

But do you look around you at what happens with electronics in popular music?

Well, actually, I don't have the time to have a pressing curiosity in that area. I hold

tight to my own formulae and my system. Moreover, I think this music becomes

more and more polluted ... this music is absolutely disgraceful on the radio, at the

cinema, in adverts. And I see that at the moment there is one sound. Not sounds. One

single sound, everywhere. It's a sound that has been standardised. It's a sound that is

produced digitally, and it all comes down to the same sound, which is a painful thing

at this end of the century.

What was the effect on you, when you scored a number 1 hit single in the French charts?

But I haven't been number one in the hit parade! That is a big misunderstanding! The

record was released in a category of classical music, and I was judged by the

standards of classical music, not of pop or rock music. In the same list, 2nd and 3rd,

were the Concerto de Aranjuez, The Four Seasons, Albinoni. So, all in all, the young

people were right to buy La Messe Pour Le Temps Present and Le Voyage, La Porte

Et Un Soupir. But it was a list of classical music.

You did attract large audiences at your live concerts. Did you feel like a rock star?

I have met with the appreciation of a large public that was interested in my concerts.

I believe that everywhere where I have performed interpretations of my work, I

received an immediate response from the audience. Whereas, with the release of

records, the reactions of the audience are quite remote. Now it is more interesting for

the audience, because the records are copied, and less interesting for the composer.

But overall, the music gets everywhere which is basically a good thing. But don't

forget that as well as discs, there is also radio. I have renewed my acquaintance with

the radio waves recently.

I think it must have been an awkward experience to suddenly see masses of people crazed

over your music.

I was not very much embarrassed by this because I was always occupied by my

music. And by its continuity.

Could one say that your reputation from the 70s is what has brought you into the Mantra

label's catalogue?

I don't think so, because Mantra has a catalogue that features music that differs from

mine, even though that music too is outside of the norm. The label believes in my

music. No, there's nothing to be astonished about. These people happen to like my

music. They're nice people and they want to release my work. I'm quite content with

this label.

Two interviews with Pierre Henry pg. 2 of 15

BASIS: MUSIC / SOUND

Using non-musical sounds inside a traditionally musical context is one thing. In the 50s (and 60s)

we saw electronic composers work with electronic sounds inside a classical musical structure. Do

new sounds require, or even lead to new compositional structures? Michel Chion, in his book "L'Art

des Sons Fixés" advocates a compositional approach that is different from the classical (notated)

manner. Not (only) work according to a preconceived structure and sound-palette but adopting the

approach that the material induces as well. That is, improvising in the studio. Working by trial and

error.

How do you set to work? Do you work like the classical composer, writing things down and

then executing them (collect sound material, equipment, record, and edit)?

Like you say ... these new structures, the way you say it, that's like putting the horse

behind the cart. One of course has to compose with a direction, a lucid idea. One has

to have in mind a certain construction, a form. But that form differs according to the

theme, to the character of the work and of course according to the material. A work

like Le Voyage [a piece based almost entirely on feedback - IS] has a form, another

like La Porte another one. And another work that requires a voice or chanting ...

every work has its form, but this form is there in the art of creation. I think that from

the beginning of my work I have been more original in my form than in my material.

Pierre Schaeffer wanted to educate composers (and as a result of that, of course, audiences,

too) to find a new way of experiencing music, a sort of "pure listening experience" somehow

even coming close to the theories of John Cage. It has become clear, through the years, that

you do not see things that way. Although you use sounds 'clean' (with a very clear relationship

and association to its source), you use it in such a manner (by encapsulating it in a structure,

or combining it with other sounds) that it becomes disassociated from its source, or perhaps

becomes an icon, a metaphor. Sometimes this leads towards a solemn, and theatrical

atmosphere. What is the function of a sound in your composition? Is it a metaphor?

No, but as you already say in your words it is certain ... my work is so varied that

there are works where sounds are exposed with their tempered notes like La Noire à

Soixanteand others which are truly life; the development of sound and its

multiplication, its transformation, its mutation, I think that is the better word for it,

like in Le Livre de Morts Egyptien. There are sometimes no laws, basically. My

sounds are sometimes ideograms. The sounds need to disclose an idea, a symbol ... I

often very much like a psychological approach in my work, I want it to be a

psychological action, with a dramatic or poetic construction or association of timbre

or, in relation to painting, of colour. Sounds are everywhere. They do not have to

come from a library, a museum. The grand richness of a sound palette basically

determines the atmosphere. At the moment I try to manufacture a certain 'tablature de

serie'. I won't talk about it. I almost become a late serialist. After a big vehement

expressive period, post-romantic, I think that now I'm going into a period of pure

ideas. It all reminds me very much of my work of the 50s.

Can you tell something about what sound is, and/or what it means in your work?

It is more a phrase. Contemporary digital sound is very realistic, but also very

impersonal, it's not a word but an atom, almost virtual. The words together become

phrases. These phrases are combined by me.

Two interviews with Pierre Henry pg. 3 of 15

MATERIAL: THEMES

The atmosphere and themes of your work have changed through the years. When we listen to

your early work it is noticeable that humour plays a part. This is hardly ever present in the

work (that I know) of the last 20 years. I also notice that in the early days you regarded

yourself as a man of modern times, who wants to break with the history of music, become a

composer with modern means. This unruly, stubborn attitude later on seems less emphatically

present. What do think of that yourself? Do you still think one should destroy all music?

Well, the things that one says at the age of 20 are, of course, not the same as those

one would say at the age of 60 ... I believe that every day one destroys their past. My

earlier works are not literally destroyed of course, but when I listen to one after the

other they are non-existent now. I don't regard myself as more or less revolutionary

now than in the beginning, but now I compose works that are less spontaneous, and

more reflective on the things that I see around me, comprising issues of philosophy

and metaphysics, radiating a certain serenity which is, I think, a natural thing for an

artist. After years of hard work one arrives at a sort of peace and one tries to restrain

one's language.

Death is an important issue in your work. I think of Le Voyage, Le Livre des Morts Egyptien

and Le Livre des Morts Thibetain. Why are you so fascinated with the theme?

That's very difficult to say. I think it is the emotional part of my self. I have had

many relations who have died. I think that the loss of a friend or a loved one invoke

emotions and these emotions are also the emotions that come from tragedies or

stories. Death is a great subject for a work. On the other hand I prefer birth, but to

me, artistically, I like very much the notion of death, more than birth. I believe that

one departs from the end and works towards the beginning.

THE COMPOSER AND THE FIELD OF ELECTROACOUSTIC COMPOSITION

In 1964 you made a prophecy for a newspaper. Fifty years later there would be less other

music, but more electronic music. We are now 30 years on the way to 2014. Indeed electronics

play an important part in the production of music of these days. What do you think of the

developments?

I have said that these developments were an inflation of the imagination musically

and soundwise because ... I believe that the dressing up of electronics by CD-ROM

and all the communications techniques, I think that this adventure will turn back at

the music made with a twisted voice ... that's a pity because, for example, people

with a fantastic creative mind will be submerged in showbiz. They will be

overloaded with synthesizers. I now have strong confidence that we will reach a

musical life.

You are a film enthusiast. Brigitte Massin once said that in your studio you sometimes write

down your composition like a filmscript. Does the notion of "acousmatism" [the musical

equivalent of cinematography - Ed.] appeal to you?

I can't see the relation between film and the acousmatic. I think that cinema is a way

of imagining life, the rhythm, whereas the acousmatic is a way of catching it. One

should not confuse a cinema with the film that is projected.

When I listen to contemporary electronic and electroacoustic music I see that to many

composers one aspect is very important: the use of technology and the meaning it has to the

composer. Of course the management of the machine/instrument that one plays is quite

Two interviews with Pierre Henry pg. 4 of 15

important. And composers of electronic or electroacoustic music have the disadvantage of

having to learn to play new (and improved?) instruments every month. When listening to

many contemporary compositions I hear a composer who is still impressed by his machinery.

As a result we hear beautiful sounds that only function as a catalogue of the capabilities of the

equipment used. Creative aesthetic statement seems to have become of minor importance. I

see that in this regard you stand out from the crowd of composers. Why is it that in your

music this pre-occupation with machinery in most cases is absent? And (having asked you

about your relation with sound): what is your attitude towards your machinery?

That's very simple. I have always had a battle with the machines; not for aesthetic

reasons but for reasons of quality. At the beginning of music concrète we worked

with discs, but the result of copying a piece of sound was quite poor. So I have

always struggled to have the sounds retain their transparency. Now I have conquered

these problems, thanks to digital techniques. It is possible to make a perfect copy, but

I am worried about the machines doing the work that I should be doing. This is the

case with many of the logical catalogues that are available to which one can

subscribe. The computer works instead of you. The computer has decided. I think

that we now live in a dangerous age because the composer should certainly not work

with a tap, that he can open or close. That's a very bad development.

I try to work without any specific machinery and when I find a machine ... I find a

machine interesting when I have twisted it without knowing. That's same thing like

in painting. I love it when the objects have been led away from their function. When

working with a filter, and this filter turns a sound into something entirely new and

unexpected, that interests me more because I am less connected to the style of the

machine and its function than to the source of the sound. The source of a sound

interests me because that's the adventure of mind's world. There are particular sounds

that interest me because they have been cut in certain fashion, because they have a

certain roughness, because perhaps there are these stories that have not been entirely

excised. An analogy: Raymond Roussel wrote his books with mirrored images with

coded words and I use coded sounds and shallow sounds and sounds that tell a story.

And these latter sounds to me are The Sound.

The second aspect is a direct consequence of the first one: your music is able to express a

clear-cut statement, just because you concentrate on what you want to express. You make

quite dramatic statements. Is that caused by a passion for stage presentations?

It is not easy. It is a passion for the dramaturgy and also for the psychological

problems of this age, the suspense and the curiosity as to where society will go.

Music to me is also finding a solution. I am very much interested by the language of

sounds and more still to make with the sounds a personal theatre where there are

actors who meet and then fight or embrace.

Is it an emotion?

It's an emotion, but ... it's me who steers them and they stem from myself. They do

not necessarily have to be emotional. They exist.

The electronic/electroacoustic composer is often a lonely man, sitting behind his desk with his

tools. In your case, most of the photographs I have seen picture you in a live situation. You did

some large scale live performances. Were these the consequence of your popularity in the 60s

and 70s? Did you attract a large and broad audience?

Well, I wanted an audience that was adapted to a certain condition. I wanted a

concert that was made theatrical by decoration, light, glass, sounds. Certainly also by

Two interviews with Pierre Henry pg. 5 of 15

the spatialisation of the sounds that were made audible. These concerts were given in

boxing venues, churches and concert halls. I certainly had a long period of well-

attended concerts but now it is different because the audience now has the radio and

the discs.

Nowadays many people hear music at home. Electronic music has certainly drawn back inside

the cocoon of the living room. Many of your works have been designed for stage performance.

How do you feel about this situation? Why is stage performance so important to you?

The concert is an artistic performance. A concert work must be re-recorded and re-

edited for home listening. When I make a version for home, this version is aimed at a

close listening, but it must be more profound and richer. Both situations and both

versions are interesting. Practically all my important works have been released on

disc but only the future will tell what will happen in the area of concerts.

CONTEXT

Henry was almost the opposite of Pierre Schaeffer, the godfather of musique concrète. Schaeffer

was a thinker, a theoretician, and not a musician. Schaeffer was interested in concrete sounds from a

theoretical point of view. Henry on the other hand was a trained composer, and most of all

audacious, ready to set about things. Concrete sounds were interesting to him as a means for

composing music. The two Frenchmen had in common their curiosity and a maniacal search for

order. But whereas Schaeffer got stuck in ordering his thoughts about sound and instrumentation, in

search for a totally experience of music, Henry in 1958 left the Paris institute to set up his private

studio, where he could work with his sounds without being bothered by bureaucratic rules and

regulations.

HISTORY

Pierre Henry was born in Paris in 1927. He never went to school; his teachers came to his house.

Being of feeble health he had to do gymnastic excercises and perhaps that is the reason that he

developed a strong feeling for rhythm. In 1944 he studied at the conservatory; piano and percussion

with Passeronne, composition with Nadia Boulanger and harmony with Olivier Messiaen. Henry is

an ardent film lover and visits the cinema two or three times a week. "Le Ballet Mecanique" by

Fernand Leger is a great inspiration because of the direct link between sound and vision. In 1949 he

received a commission to write music for a television documentary called "Seeing the Invisible".

He then started working with the 'disque souple', the writable record. The tape recorder was not yet

available in a practical model. He by then had already made acquaintance with Pierre Schaeffer and

with the music of Luigi Russolo, John Cage, Walter Ruttmann etc. When Schaeffer asked Henry,

because of his skills as a percussionist and at the piano, to assist him with the Symphonie pour un

Homme Seul in 1950, the career as a composer of musique concrète or, better, electroacoustic music

has taken a lift-off.

The early electroacoustic compositions, dating from 1950, show Henry dabbling about with sounds

recorded with the disque souple recorder, much in the same vein as Schaeffer. The structure,

however, is much more complicated. Whereas Schaeffer keeps to simple classical and rhythmical

structures, Henry shows much more insight into complex composition.

In 1964 Henry produced his Jerks Electronique with a 'song' called Psyche Rock under the

pseudonym Yper Sound. It sold some 150,000 copies. It made Henry instantly famous, not only

with connoisseurs of avant garde art but also with the man in the street. A few years ago its echo

was to be heard in the background of a house music record. Anyway, it enabled Henry to make a

good deal with the Philips label. Although always following his own path, Henry has never been a

Two interviews with Pierre Henry pg. 6 of 15

solitary closed man. His friendship with dancer Maurice Bejart has taken him all over the world.

Henry has produced music for films and advertisements.

Another difference between Schaeffer (and the disciples of his theories) and Henry was that Henry

did not follow the Husserlian ideas about music. To Henry sound has never been interesting as a

phenomenon as such. That's why he denies the existence of noise; there is only sound. The sound

that is there for music. To Henry, emotion, he calls it nature, is to be captured in music. That's a

fundamental step over the line that Schaeffer had drawn.

Towards the end of the 70s the public attention died down, but Henry continued to develop his

music. Through the years Henry's work has gradually changed from spikey, and sometimes even

anarchistic (certainly for the well-behaved musical society of the 50s) towards themes that are more

sincere and more reflective. Perhaps it is because of these themes, not fit for a society that

welcomes the energy and ideas of punk-rock and anarchy, that Henry has remained more in the

background. In 1989 however, the WDR broadcast a radio-play in three episodes, each lasting 180

minutes, on Proust's "A La Recherche...". In 1990 a new work was released: Le Livre des Morts

Egyptien. Henry has been invited to perform the work on several occasions around the world. Let us

listen to Henry's music from a cool distance.

RECORDINGS

Henry's works have in the past been released on vinyl by Philips, all of which have been long

deleted. Much to my regret because what I did know of his work I have been able to purchase at

fleamarkets. But sound quality was poor of course. Philips only rereleased the Variations pour Une

Porte et Un Soupir on CD a couple of years ago. Now French label Mantra has rereleased a series

of works by Henry. I was amazed to see this because the Mantra catalogue for the most part features

New Age, Krautrock and hippy music. Henry however doesn't seem to be worried by this marketing

anomaly. So why should we? The quality of the releases is excellent.

Les Années 50 (3CD)

This trio surveys the early works of Henry when he still worked with Pierre Schaeffer. As with

many creative people the early work in hindsight reveals the core of the later work. The core of

Henry's work are the piano (snares) and percussion. They are abundantly present on these three

discs. The later solemnity of the work of Henry is completely absent in these works. Humour plays

a part (Vocalises), and we hear comments on jazz music (Tabou Clairon). Now and again there is a

wildness and freakiness that Nurse With Wound could only dream of (the hilariousKesquidi,

something like a Marx Bros film on tape).

Messe de Liverpool / Pierres Reflechies

A time warp and arriving in 1967 brings us to Liverpool, with its monstrous concrete cathedral.

Henry had been asked to compose music for the inaugurational mass. Henry by that time already

wore the aura of being a composer with a deep affection for public performances of a mass-like

character. Messe de Liverpool is structured as a classical Catholic mass. Starting with a Kyrie,

moving on with Gloria, Sanctus, Agnus Dei, and finishing with Communion. The work consists of

recitation of the traditional texts in a way that is definitely Buddhist. These voices are supported by

traditional musical instruments that are traditionally played at first but after some ten minutes they

are played in a typically Henry-esque fashion: plucking and scratching the snares.Pierres

Reflechies, composed in 1982, bears all the characteristics of the contemporary Henry: ostinatos of

a certain number of instruments that are placed, superimposed over each other in thousands of

combinations that differ only slightly. This description makes one think of minimal music. But this

Two interviews with Pierre Henry pg. 7 of 15

is much more anarchistic, more undisciplined. Here the ideograms that Henry speaks of in the

interview are applied. Some parts reminded me very much of the Cristal-Memoires radio-play that

he composed for the German radio (which is to my opinion, next to theApocalypse is the best he

ever did). In this composition Proust's work is translated in sound, which of course has all to do

with ideogrammes and synaesthesia. Pierres Reflechies is dedicated to the late Pierre Schaeffer.

Mouvement, Rhythme, Etude

This work is dedicated to a close friend of Henry: Maurice Bejart, the famous dancer. Henry has

composed numerous works for ballet, which were staged by the dancers of Bejart. In the early days

Henry even accompanied the dance group all over the world. This work is exactly what the title

says: it's a study of movement and rhythm. Starting of with very simple beats that meet with the

reversed sound of scraped metal wires. Track 2 is a play for blowing balloons and a person saying:

'pssh' and 'psst'. Talking about humour. Track 3 is instrumental and quite acoustic whereas track 4 is

entirely electronic. And that's how it continues. The whole things consists of 21 etudes for a ballet

dancer.

L'Apocalypse de Jean (2CD)

This is Henry's masterpiece. Actually there is nothing much to say about the composition when one

decides not to dissect the work in exegesis. The apocalypse, spooky already in the literary form, is

performed in a fashion that makes the hair on your back stand up. Henry's translation of the

different scenes, using no doubt the ideograms, is more than perfect and the narration that

accompanies the auditive scenery brings shivers down your spine. When your French is below

average I advise you to read along with the music in your own language. Try to find a Bible

somewhere. John's apocalypse inspired Clive Barker too, you know.

Le Livre Des Morts Eqyptien

Death is an important theme in Henry's work. The Egytian book of the Dead therefore is an ideal

theme for Henry to work on. The ideograms that are essential in this composition are magnificently

worked out. The course that the sounds take is quite dramatic and theatrical. The introduction is

awe-inspiring. Henry follows in the subsequent scenes quite exactly the course that the dead person

will go when on his/her trip towards the realm of the dead. The associations with large pyramids

and ancient Egypt are but one layer in this 'spectacle'.

L'Homme A La Camera

Based on the film by Dziga Vertov. Here again Henry's love for the filmic genre is shown. Actually

this work should not be listened to without seeing the images. The titles give a clue about the

scenery but that's hardly enough. Indeed, we can hear Henry go back to what he calls the pure

composition that he favoured in his early works. In this soundtrack the large and dramatic

movements are absent. The music is as machine-like as the film is. It tries to abstract the concrete.

This interview was made possible thanks to Jerome Noetinger of Metamkine. For

those who would like to read more on the life of Pierre Henry, Michel Chion wrote a

biography in 1980, published by Fayard in Paris, and available from Metamkine, 13

rue de la Drague, 38600 Fontaine, France.

Two interviews with Pierre Henry pg. 8 of 15

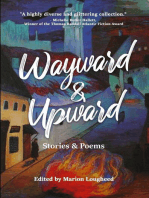

INTERVIEW NO. 2 WITH PIERRE HENRY

photo by S. Ouzounoff (Radio France)

Interview by Iara Lee for Modulations

As you could tell by the name, music concrete is a French concoction- one of its

pioneers is composer Pierre Henry. Along with Pierre Schaeffer, Henry took sounds and

manipulated, re-arranged and recontextualized them. In one brilliant piece, Henry took a

squeaky door and a person sighing and turned these into saxophones, bells, laughter,

gongs, wind gushes and other unidentifiable noises. After creating his early

revolutionary work with Shaeffer in a state sponsored studio, Henry went to work on his

own studio in the late '50's, further exploring this medium, which continues even now.

Today, Henry's work with sound manipulation is what we usually think of as sampling.

His works have included the very moving "Voile d'Orphee" (1953) (where sound

sources become meditative orchestras and choirs), the above mentioned "Variations

pour une Porte et un Soupir" (1963), "Le Voyage" (1961-63, based on the Tibetan Book

of the Dead) and more recently "A La Recherche..." (a radio play based on a Proust

work) and "Le Livre des Morts Egyptien" (1990). His work has also included assorted

collaborations with poets, dancers, film makers and rock bands (Ceremony with Spooky

Tooth, 1968), not to mention his foray into popular music with Yper Sound ("Psyche

Rock", 1964).

Iara Lee conducted this interview for her film Modulations in September 1997 at

Henry's home/studio in Paris.

Q: What time or period do you consider music concrete to be rooted in?

Concrete music is not a music of today nor of yesterday. It comes from a long

way off. Many composers, artists, writers, painters imagined that one day

music would transform itself into a vast opera of new sounds, unprecedented

sounds, sounds that have never been heard of.

Two interviews with Pierre Henry pg. 9 of 15

As a child, my head was filled with new sounds, sounds that couldn't be

interpreted. And that is the peculiarity of concrete music. It resides in the fact

that it doesn't come from interpretation nor performance. Thus imagination is

the core of concrete music. And this imagination is linked to a technique, to a

way of doing. So the first would be that concrete music is a music that is done

differently. It's the fabrication of music and not only fabrication but also its

conception and its composition.

Q: What do you mean here by "conception"?

I refer to conception because it's unwritten music. It is thought and imagined

and is engraved in the memory. It's a music of memory. Usually when a

musician leaves out a fragment, a chord, he leaves it out from his score. In

concrete music, we can't leave anything out because it's always there. So the

second posit is to isolate a sound, keep it, record it and than proceed to make

manipulations, developments, imitation of old pieces, and synthetic exploration

of the nature.

Because concrete music comes from nothing it has a high range of possibilities.

It's a spontaneous creation and at the same time it doesn't play, therefore it

keeps on being. Fortunately recording still exists. Now it's through digital

recording, before it was on a tape recorder and before that on a soft record.

Concrete music was born in Pierre Schaeffer's studio. Pierre Schaeffer had the

idea to produce sounds by means of different tools, by splitting the attack of a

sound, prolonging the sound by reverberation, repetition, a sort of alchemy that

doesn't exist in orchestral music.

Q: What was the initial reaction to this music?

There weren't many reactions because it simply didn't exist. When we started it

in 1948, 50 years ago, there weren't any researchers or inventors. We were

isolated. Many instruments could be considered electric. There were

sophisticated organs. Electricity was fashionable. The introduction of electric

guitars and other electronic instruments was certainly interesting for us. It

encouraged us to use high-speakers in order to create other sounds that came

from nowhere. Thus concrete music is a music that was invented based on

nothing. It's a dust of sound, it's a coma of sound, it's almost nothing. In a piece

entitled "Spiral," the sound came from some sort of amplified respiration that

repeated itself endlessly, this continuity was of a very interesting choice in the

sense that one could see that it could be performed and developed with the

wrist and with fingers. This music cannot be played with instruments but with

electronic tools.

Q: Did you consider this music to be a stance against any particular school of

musical thought that came before it?

There weren't any reactions against any school. We came from a musical cell.

Before, I was a normal music composer. I wrote for instruments. I studied at

the academy of music with Olivier Messiaen. I played percussion. The classical

approach to music led me to connect this new music to tradition. So there

Two interviews with Pierre Henry pg. 10 of 15

wasn't any opposition to atonal music nor to serial music.

The idea was to find a new form of music, a new writing style instead of just

imitating and being stuck in a trend. We essentially wanted to bring out a new

music. It had nothing to do with the other kind of music. It was meant to be a

revolution in connection with the state of being a musician, to the musician's

function and to listening. We are different from other musicians but we are not

opposed to any music.

Henri Michaux had lent me a record of Japanese music, sacred music and I

started doing something with it. It was an interesting way to begin, more

interesting than a flute. It had a different blow that we could play off. We could

make variations out of it. Variation is the principle of concrete music. A cell

becomes another and then there are combinations, associations, and many

possibilities of inter-mixing, of polyphony. Current music is extremely

polyphonic. It's like a grand orchestra but it's done track by track.

Q: How did the sounds that you create literally come about?

It was a day by day, in the 50s an ongoing invention, but it was also a search

for brainwaves. This music was still not codified, standardized equipment such

as the synthetics, before synthesizers.

All current processes were discovered at that time. The anarchy was to search

for these processes but it wasn't a revolution. A composer is inevitably

revolutionary. But it's not necessarily revolutionary in his writing, in the way

he composes. He is a revolutionary in the mind meaning he has his own

esthetic. Beethoven was a revolutionary compared to those that preceded him.

I wrote about destroying music in order to alter little by little the listening of

music. But contrary to groups of painters or writers, the musician is like a

monk. He has to stay in his studio and work everyday by constantly trying out,

listening, starting all over a piece. Musicians don't have time to be

revolutionary.

Concrete music leads to authenticity more than the usual kind of music. It's like

a photographer who makes try outs, does Polaroid, spotting. Music proceeds

from photography, cinema. We set up planes, cut out the editing but also the

grain of sound like the grain of photography.

It's a music that is connected to photography, to cinema, a little to literature,

and less to music because the music lies within you, you don't learn it whereas

you have to learn the rest. A story needs to be told with this type of music. It

needs an action of gestures, a choreography of sounds, movements. Concrete

music is the music of movements, of rhythm, of beat. The body needs to be

linked to a musical sentence different from the one of other kind of music. This

other music is thought and abstract whereas ours is concrete. It is concrete

because it is related to the body, to the surrounding, to objects, to nature, to

emotions.

Two interviews with Pierre Henry pg. 11 of 15

There is an emotion. I'm currently composing a new piece in which I'm trying

to bring forth an emotion that will then be experienced by a public. There is

also a communication. It's a music of communication.

Q: How important is rhythm to you?

I'm interested by all kinds of rhythm, irrational rhythm and arithmetic...

syncopation, jazz, rhythm, beats. There is always a beat in my music. The beat

is what I find more interesting than something asymmetrical. Everything has to

be natural for me. It's a music that comes from nature, there are rhythms in

nature that can be qualified of elementary, surprising, aleatory, that come and

go. I don't like codified music.

Q: So do you see a connection between your work and techno?

We've been recently talking a lot about techno music, in reference to the mass

of the present that sort of initiated not so much rhythmic music than music of

the rhythm. It's a music that must be drawn from technique and be connected to

what I'm trying to do that is inspiration, to the body, some sort of cerebral

trans., though I think it's unfortunate that it is for the moment too much

connected to the place it is listened to, to high volume listening where bass is

powerful. It's a music far too much connected to physiological reactions and

not enough to mental reaction. It has no sensitivity, it's not surprising enough

and it lacks poetry. I feel music should keep its share of poetry.

Q: Do you think it should also have a soul to it?

I don't think music shouldn't have a soul. Music should consider the past as

much as the future. And there are still many things to discover in the future. So

we should begin illustrating this future with futurist projections such as the

apocalypse, by emphasizing changes, and by pointing out the differences in

each centuries, and that there is an evolution. A technical music is of no interest

for me.

Q: Does it bother you to use digital equipment for your work nowadays?

No, it doesn't disturb me. It helps me keep and preserve the sound. Concrete

music was precarious, very difficult because sounds were almost immediately

damaged.

There are many things we can do with digital sound such as uncovering the

original sound. All sounds become original sounds, the sound of the beginning.

That's interesting but there is a betrayal in the sense that digital sound is not as

good as analogical sound. It has less strength, less impact, less presence.

Therefore it's necessary to mix analog, that is, old equipment with new

equipment. We can't get rid of old equipment. We still need to have the future

connected to the past. And that's what life is, this mixture slightly archeological

of the laws of the past with the foresight of the future.

Two interviews with Pierre Henry pg. 12 of 15

Q: Is it possible to create music that expresses inner thoughts and expressions?

I did that in the '50's while I was working with records and making

improvisations. But I used tape recorders. I did concerts where I would

improvise and perform using artificial waves. I had transmitters set on my skull

so that we could hear what came directly out of my skull. Instinct served

music. The music was intuitive, instinctive.

Q: Do you find it necessary to be open to chance in your work?

It's as important as fate. Without fate, without any deviation... drifting is

necessary once in a while. I often play everything together and then listen.

Sometimes a strange phenomenon occurs.

We need to catch it. But that which is intuitive, instinctive, imaginary comes

also from fate because fate is nature. It's always the same. There's thought and

fate, the control of fate by thought, and the simulation of thought by

fate.

Q: Did you see composers such as Russolo as kindered spirits?

I can't really say that I felt close to Italian futurists. I thought of them as fascists

and not as artists. Of course it was glorifying for them to say we could make

noise, but there always has been noise, even classical composers would add a

cannon shot in their work. Noise becomes a musical note when altered.

Real noise is very interesting. A drama should be told with noise, and then it

can be broadcast. I enjoy noise in film, I dislike music in film. I like to

conceive a score like a film, with noises, voices.

Q: So music concrete stood alone?

We were isolated. There was the bet. There was John Cage whom I didn't

know. And Stockhausen was much younger. It all started distinctively and then

similarities were discovered. I've also performed prepared piano different from

John Cage's performance. Stockhausen's research was somehow slightly

similar to mine. And then there was the splitting. There was a need for new

music. New music meant new sounds, new ears.

Q: How do you see changes in recording technology as having an effect on music?

Has it been a positive effect?

During the evolution of technique, engineers wanted to bring out finished

products, standardize manufactured products. What was interesting in

electroacoustic music, was to search, to find new ways, new possibilities. The

automatism of finding didn't bring forth much possible aspiration. Though

gradually this music evolved and became quite convenient. It has become a

homemade music, the music of the new studios, the music of films. Now we

can't imagine any other kind of music for those kind of work. So we play

classical music, but current music is constantly invented over and over again, it

Two interviews with Pierre Henry pg. 13 of 15

has become like the sound of the sea, constantly renewed, but always the same.

That's why I fear that sound will be the same everywhere, on the radio, in

films.

And it's easy now for youngsters. They can get for only a few thousand francs,

a box, an amp, something that makes sounds. There is no longer a formal

sensitivity, meaning that music comes out. I prefer music that stays inside of

us, that allows us to dream, to imagine and even perhaps to love. The music I'm

referring to is the one of communication. It's a language more than an art. Now

it's no longer a language. It's some sort of tam-tam constantly present. I'm not

convinced by current music, the way it is done. But there are some

possibilities. It's form is similar to the one of beginning of music in the Middle

Age in France where it was not only just a form but it was also very boring. I

don't particularly like cave music. I prefer vocal music starting with Bel canto

and then with Melesande and Pelleas. Music of yesterday was linear and white.

When Renoir spoke of white he meant with no colors. And music of today has

no colors. That's why I try to add a little spatial effect and colors in my music.

Q: What do you mean by 'space' then?

Speaking of space means that there is already space in reactions, in music. I

want music to be profound. Even in mono. At first, I was against stereo. I didn't

like it. I like mono sound, the sound of a dimension and that in this dimension

there is a past, a present, that it moves. I didn't like the panoramic aspect of

sound. I like the sound to be enlarged and elaborate like under a microscope.

The first concerts I did were in mono. First the sound came through one track.

Then there were tape recorders with two tracks, stereo, which had inevitably a

center. There was still mono in stereo. I thought of it as being too artificial. I

then imagined concerts using a lot of mono, which created movements using

specific technical tools, or gestures that would attract sound to a high speaker.

Mono sound was moving and I found it more interesting then to create

movements with stereo sounds. Gradually I stuck to the cinematography point

of view, where sounds had various dimension, were very focused that is with a

sound here, on the top on the bottom but stereo couldn't be used to give spatial

effect to a concert room. I refer more in terms of specialization than of stereo.

My next creative piece for the radio will be on 16 tracks. Those 16 tracks will

each go directly in a speaker.

Q: How has editing figured into your work?

It was an option because sound existed with length. With length on a record or

a soundtrack, we couldn't always cut off the attack but we could place it at the

end or reverse part of the sound. Cutting off the attack... well many film

makers have done it way before us. Optical tools allow us to cut off the attack

of sounds. Many film effect were done that way. It's not an invention. Invention

is recording a sound and playing with it. That's invention. Cutting off the attack

is part of the 1001 possibilities of manipulation.

Two interviews with Pierre Henry pg. 14 of 15

Q: Is it a technique that interests you?

That's a harmonic question. It's a question of thickness of sound. It's not very

interesting. At the beginning Pierre Schaeffer cut off the attack of the piano and

it gave sound. What's important is to have many possibilities of manipulation

in order to give substance to the game, the game of sounds.

Sounds must play for we don't play with instruments, we play with soundtrack,

with editing, filtering, reverberation. These games must use all kind of

possibilities. It's about transformation, the magic of transformation of sounds is

important. I've always thought of music as a way to let things come out. Many

sounds, and also many ideas. It's an animation, an animation of sound talk.

Q: Do you find that your work with Sheaffer has been something of an

exploration?

"Symphony for a Lonely Man" corresponds to my first step toward concrete

music. Before that, I did some try outs with equipment, with instrument of

sound search. When I met with Sheaffer again, we composed this piece. It's not

a research. The search had already been done. It was a continuity. We wanted it

to be like a spokesman, with an aesthetic approach. And the aestheticism was a

symphony of voices, instruments with noise. "Symphony for a Lonely Man"

was composed by two lonely men.

Two interviews with Pierre Henry pg. 15 of 15

You might also like

- Stern Strategy EssentialsDocument121 pagesStern Strategy Essentialssatya324100% (3)

- 2 Michel Thomas Spanish AdvancedDocument48 pages2 Michel Thomas Spanish Advancedsanjacarica100% (2)

- Chasing Chopin: A Musical Journey Across Three Centuries, Four Countries, and a Half-Dozen RevolutionsFrom EverandChasing Chopin: A Musical Journey Across Three Centuries, Four Countries, and a Half-Dozen RevolutionsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- Cage Future of Music CredoDocument6 pagesCage Future of Music CredocaseyschenkofskyNo ratings yet

- Brian Eno - His Music and The Vertical Color of Sound-Eric TammDocument186 pagesBrian Eno - His Music and The Vertical Color of Sound-Eric TammEscot100% (3)

- Murail, Tristan - Scelsi and L'Itineraire - The Exploration of SoundDocument5 pagesMurail, Tristan - Scelsi and L'Itineraire - The Exploration of SoundLuciana Giron Sheridan100% (1)

- Offshore Engineer-February 2015Document84 pagesOffshore Engineer-February 2015ilkerkozturk100% (2)

- Pierre Henry InterviewDocument10 pagesPierre Henry InterviewNikos StavropoulosNo ratings yet

- Rozhovor Pre Hudobný ČasopisDocument5 pagesRozhovor Pre Hudobný ČasopisneviemktosomvlastneNo ratings yet

- MB InterviewDocument4 pagesMB InterviewEstevão MaldonadoNo ratings yet

- Morton Feldman Talks To Paul GriffithsDocument4 pagesMorton Feldman Talks To Paul GriffithsalexhwangNo ratings yet

- The Studio As Compositional ToolDocument4 pagesThe Studio As Compositional ToolpauljebanasamNo ratings yet

- Entrevista A Helmut LachenmannDocument6 pagesEntrevista A Helmut LachenmannEva García FernándezNo ratings yet

- Newm Icbox: Sitting in A Room With Alvin LucierDocument10 pagesNewm Icbox: Sitting in A Room With Alvin LucierEduardo MoguillanskyNo ratings yet

- RadioshowtranscriptDocument3 pagesRadioshowtranscriptapi-354741791No ratings yet

- My Life With TechnologyDocument10 pagesMy Life With TechnologyJulio César TeixeiraNo ratings yet

- Questionnaire Rebecca SaundersDocument4 pagesQuestionnaire Rebecca SaundersU ONo ratings yet

- Time Out N.Y. Interview W/ John LurieDocument3 pagesTime Out N.Y. Interview W/ John LurieGarbouliakNo ratings yet

- Cage - Pataphysics Magazine Interview With John CageDocument3 pagesCage - Pataphysics Magazine Interview With John Cageiraigne100% (1)

- 2012-07-26 Musical Aesthetics (Richardcarrier - Info) (1965)Document50 pages2012-07-26 Musical Aesthetics (Richardcarrier - Info) (1965)Yhvh Ben-ElohimNo ratings yet

- Booklet MP Carpentier TheoDocument19 pagesBooklet MP Carpentier TheoTheoNo ratings yet

- Erasing The TimelineDocument5 pagesErasing The TimelineRicardo AriasNo ratings yet

- Gagne 1982 ADocument8 pagesGagne 1982 AalexhwangNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document4 pagesChapter 2Vincent FeutryNo ratings yet

- Suzanne Ciani: by Alexis Georgopoulos All Images Courtesy of Suzanne Ciani ArchiveDocument6 pagesSuzanne Ciani: by Alexis Georgopoulos All Images Courtesy of Suzanne Ciani ArchiveMichael GrossmanNo ratings yet

- Greg PhillinganesDocument3 pagesGreg PhillinganesivanNo ratings yet

- Interview Ligeti 1Document10 pagesInterview Ligeti 1PepeGrilloNo ratings yet

- Philip, Robert - Studying Recordings-The Evolution of A DisciplineDocument11 pagesPhilip, Robert - Studying Recordings-The Evolution of A DisciplineNoMoPoMo576No ratings yet

- Analysis Phenomenology SpectralDocument21 pagesAnalysis Phenomenology SpectralbeniaminNo ratings yet

- We in Music Are Like Physicists: TH THDocument5 pagesWe in Music Are Like Physicists: TH THTomCafezNo ratings yet

- The Greatest Artists in Popular Recorded Music History (The 150 Greatest Artists in the History of Recorded Popular Music)From EverandThe Greatest Artists in Popular Recorded Music History (The 150 Greatest Artists in the History of Recorded Popular Music)No ratings yet

- Stockhausen EtcDocument4 pagesStockhausen Etc항가No ratings yet

- Pretty Lights - A Color Map of The Sun - Digital BookletDocument17 pagesPretty Lights - A Color Map of The Sun - Digital BookletchauhanrishabhNo ratings yet

- NYU EssayDocument2 pagesNYU EssayRishit KotianNo ratings yet

- Baroq Ue Classi Cal Roma Ntic Moder N: "The Persistence of Memory" by Salvador DaliDocument10 pagesBaroq Ue Classi Cal Roma Ntic Moder N: "The Persistence of Memory" by Salvador DaliRoyke JRNo ratings yet

- Interview With Stuart Saunders Smith and Sylvia Smith Notations 21Document10 pagesInterview With Stuart Saunders Smith and Sylvia Smith Notations 21artnouveau11No ratings yet

- Essay On Jazz As Contemporary Music PDFDocument6 pagesEssay On Jazz As Contemporary Music PDFAnya Clarke-CarrNo ratings yet

- ANGERFISTDocument4 pagesANGERFISTonzemillevergesNo ratings yet

- Hightower - The Musical OctaveDocument195 pagesHightower - The Musical OctaveFedepantNo ratings yet

- Stockhausen Karlheinz 1972 1989 Four Criteria of Electronic MusicDocument12 pagesStockhausen Karlheinz 1972 1989 Four Criteria of Electronic MusicMax Lange100% (1)

- Peter Bacon QuestionsDocument3 pagesPeter Bacon QuestionsJNo ratings yet

- Approaching Contemporary MusicDocument19 pagesApproaching Contemporary MusicNivNo ratings yet

- Anthony Stratton "Brian Eno"Document7 pagesAnthony Stratton "Brian Eno"Viiva89No ratings yet

- Writing The Poetics and Politics of Transcription: Ghost NotesDocument18 pagesWriting The Poetics and Politics of Transcription: Ghost NotesHaley Louise MooreNo ratings yet

- David Chu Interview EnglishDocument3 pagesDavid Chu Interview EnglishCzeloth-Csetényi GyulaNo ratings yet

- Intervista Steve ReichDocument6 pagesIntervista Steve ReichandlamNo ratings yet

- Interview AVDG 1Document13 pagesInterview AVDG 1Imri TalgamNo ratings yet

- Gerard Grisey: The Web AngelfireDocument8 pagesGerard Grisey: The Web AngelfirecgaineyNo ratings yet

- Johnson VoiceDocument294 pagesJohnson VoicelibbylordNo ratings yet

- Turntable MusicDocument20 pagesTurntable MusicSwordsmanNo ratings yet

- Infinite Music: Imagining the Next Millennium of Human Music-MakingFrom EverandInfinite Music: Imagining the Next Millennium of Human Music-MakingNo ratings yet

- Musicology and Performance: Daniel Leech-WilkinsonDocument14 pagesMusicology and Performance: Daniel Leech-WilkinsonJohn HigueraNo ratings yet

- John Cage DissertationDocument8 pagesJohn Cage DissertationCustomPaperServiceUK100% (1)

- Ostrava Days 2003 - Tristan Murail Lecture PDFDocument3 pagesOstrava Days 2003 - Tristan Murail Lecture PDFCaterina100% (1)

- Cage-How To Get StartedDocument20 pagesCage-How To Get StartedAnonymous uFZHfqpB100% (1)

- Day 33 Atonal Music PowerpointDocument40 pagesDay 33 Atonal Music PowerpointLogan BinghamNo ratings yet

- Holger Interview enDocument10 pagesHolger Interview enndujaNo ratings yet

- On My Honor, I Have Neither Solicited Nor Received Unauthorized Assistance On This AssignmentDocument6 pagesOn My Honor, I Have Neither Solicited Nor Received Unauthorized Assistance On This AssignmentSuresh KumarNo ratings yet

- Презентация smartwatchesDocument10 pagesПрезентация smartwatchesZiyoda AbdulloevaNo ratings yet

- Ethiopian Health Systems and PolicyDocument81 pagesEthiopian Health Systems and PolicyFami Mohammed100% (2)

- English Activity 1Document13 pagesEnglish Activity 1Mika ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Services Provided by Merchant BanksDocument4 pagesServices Provided by Merchant BanksParul PrasadNo ratings yet

- Awanda Ray ZumaraDocument4 pagesAwanda Ray ZumaraTaz ManiaNo ratings yet

- Bazil. 22381027 (Smart Banking)Document8 pagesBazil. 22381027 (Smart Banking)BazilNo ratings yet

- Materials Letters: Featured LetterDocument4 pagesMaterials Letters: Featured Letterbiomedicalengineer 27No ratings yet

- MPTH Reviewer Part 1Document27 pagesMPTH Reviewer Part 1Hani VitalesNo ratings yet

- Motion Media and InformationDocument2 pagesMotion Media and InformationLovely PateteNo ratings yet

- A Conversation Explaining BiomimicryDocument6 pagesA Conversation Explaining Biomimicryapi-3703075100% (2)

- HRM Project On Engro FoodsDocument20 pagesHRM Project On Engro FoodsSaad MughalNo ratings yet

- BFI E BrochureADocument6 pagesBFI E BrochureAAnuj JainNo ratings yet

- MSDS Gel Sanitizer 280720-01.es - enDocument11 pagesMSDS Gel Sanitizer 280720-01.es - enCristian GomezNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Different Political Beliefs On The Family Relationship of College-StudentsDocument16 pagesThe Impact of Different Political Beliefs On The Family Relationship of College-Studentshue sandovalNo ratings yet

- The Dark Eye - Adv - One Death in GrangorDocument68 pagesThe Dark Eye - Adv - One Death in GrangorBo Poston100% (2)

- Magnetic Systems Specific Heat$Document13 pagesMagnetic Systems Specific Heat$andres arizaNo ratings yet

- Form For Scholarship From INBA PDFDocument5 pagesForm For Scholarship From INBA PDFAjay SinghNo ratings yet

- Persons With Disabilities: Key PointsDocument8 pagesPersons With Disabilities: Key PointsShane ArroyoNo ratings yet

- Major Item Wise Export 2020Document1 pageMajor Item Wise Export 2020RoshniNo ratings yet

- Fehrenbacher V National Attorney Collection Services Inc Archie R Donovan NACS National Attorneys Service Debt Collection ComplaintDocument6 pagesFehrenbacher V National Attorney Collection Services Inc Archie R Donovan NACS National Attorneys Service Debt Collection ComplaintghostgripNo ratings yet

- Law and IT Assignment SEM IXDocument18 pagesLaw and IT Assignment SEM IXrenu tomarNo ratings yet

- All The World's A StageDocument9 pagesAll The World's A StagesonynmurthyNo ratings yet

- Matter Wars Pure Substance Vs Mixture by A. D. Barcelon PDFDocument5 pagesMatter Wars Pure Substance Vs Mixture by A. D. Barcelon PDFjonna mae ranzaNo ratings yet

- Abhinavagupta (C. 950 - 1016 CEDocument8 pagesAbhinavagupta (C. 950 - 1016 CEthewitness3No ratings yet

- Experimental and CFD Resistance Calculation of A Small Fast CatamaranDocument7 pagesExperimental and CFD Resistance Calculation of A Small Fast CatamaranChandra SibaraniNo ratings yet

- Light Sport Aircraft: Standard Terminology ForDocument6 pagesLight Sport Aircraft: Standard Terminology ForAhmad Zubair RasulyNo ratings yet