Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

13 viewsRogers 1925 A Note Plato Aristote Eng

Rogers 1925 A Note Plato Aristote Eng

Uploaded by

Diogenes OrtizRogers 1925 a note Plato Aristote eng

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5834)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (350)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (824)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (405)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Wason's Selection TaskDocument5 pagesWason's Selection TaskMiss_M90100% (2)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Legal ResearchDocument10 pagesLegal ResearchAnu Lahan OnifadeNo ratings yet

- Article Writing Subjek IctDocument3 pagesArticle Writing Subjek IctAnida AhmadNo ratings yet

- Arts-Informed Research - Cole, KnowlesDocument16 pagesArts-Informed Research - Cole, KnowlesGloria LibrosNo ratings yet

- ThinkingDocument6 pagesThinkingNupur PharaskhanewalaNo ratings yet

- The Contribution of Native Ethiopian Philosophers - Zara Yacob and Wolde Hiwot - To Ethiopian Philosophy by Tassew AsfawDocument17 pagesThe Contribution of Native Ethiopian Philosophers - Zara Yacob and Wolde Hiwot - To Ethiopian Philosophy by Tassew Asfawillumin7No ratings yet

- National Science Education Standards Compare NGSS To Existing State Standards About The Next Generation Science StandardsDocument3 pagesNational Science Education Standards Compare NGSS To Existing State Standards About The Next Generation Science StandardsROMEL A. ESPONILLANo ratings yet

- Reflection Paper-The Nature of Science and of Theories On OriginDocument2 pagesReflection Paper-The Nature of Science and of Theories On OriginKarl Kristian TolarbaNo ratings yet

- Education and PhilosophyDocument2 pagesEducation and PhilosophySuraj TupeNo ratings yet

- 48 Critical Thinking Questions For Any Content AreaDocument10 pages48 Critical Thinking Questions For Any Content AreaZady Zalexx100% (1)

- Useful Sentences For Essay WritingDocument4 pagesUseful Sentences For Essay Writingmithil1111111No ratings yet

- 5AANB011 Philosophy of Logic and Language Lectures Spring Term 2012Document2 pages5AANB011 Philosophy of Logic and Language Lectures Spring Term 2012BETSIE BAHRUNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 - Developing Research SkillsDocument13 pagesChapter 2 - Developing Research SkillsArly TolentinoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1: Meaning and Characteristics of ResearchDocument6 pagesChapter 1: Meaning and Characteristics of ResearchMagy Tabisaura GuzmanNo ratings yet

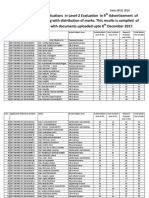

- 9th Advt of INSPIRE Fellowship List of 114 Rejected Applications in Level - 2 Evaluation PDFDocument4 pages9th Advt of INSPIRE Fellowship List of 114 Rejected Applications in Level - 2 Evaluation PDFAayushi VermaNo ratings yet

- Dr. Maheswari JaikumarDocument34 pagesDr. Maheswari JaikumarNors Cruz100% (1)

- Experimentalism and PragmatismDocument17 pagesExperimentalism and PragmatismLagman Danielle JohnsNo ratings yet

- Poststructuralism (Derrida and Foucault)Document4 pagesPoststructuralism (Derrida and Foucault)ROUSHAN SINGHNo ratings yet

- IB TOK 1 Resources NotesDocument85 pagesIB TOK 1 Resources Notesxaglobal100% (1)

- 7 Theory of Knowledge Day OneDocument10 pages7 Theory of Knowledge Day OneimNo ratings yet

- Knowledge ManagementDocument13 pagesKnowledge ManagementAchutReddy0% (1)

- The Scientific Method: Formal Vs Everyday ApplicationDocument2 pagesThe Scientific Method: Formal Vs Everyday ApplicationArc RenNo ratings yet

- HRE 121 Research in Daily Life 2: Senior High SchoolDocument17 pagesHRE 121 Research in Daily Life 2: Senior High SchoolChristian Dave EvangelistaNo ratings yet

- OneDocument7 pagesOneapi-499953196No ratings yet

- Graduate Courses & Seminars - Department of Philosophy - UCLADocument3 pagesGraduate Courses & Seminars - Department of Philosophy - UCLARaghu YadavNo ratings yet

- Joseph Keim Campbell, Michael O'Rourke, Harry S. Silverstein - Causation and Explanation (Topics in Contemporary Philosophy) (2007) PDFDocument335 pagesJoseph Keim Campbell, Michael O'Rourke, Harry S. Silverstein - Causation and Explanation (Topics in Contemporary Philosophy) (2007) PDFMaghiar Manuela PatriciaNo ratings yet

- Developing Manual Practicum Book Integrated Science Junior High School Based Home Materials To Build Students' CharacterDocument10 pagesDeveloping Manual Practicum Book Integrated Science Junior High School Based Home Materials To Build Students' CharacterNanang RahmanNo ratings yet

- Quotations RationalityDocument81 pagesQuotations Rationalitylairdwilcox100% (2)

- Knowledge Management Techniques in B - Schools - With Special Reference To Entry and Exit PointsDocument6 pagesKnowledge Management Techniques in B - Schools - With Special Reference To Entry and Exit PointsTyrone RiddleNo ratings yet

- Feist Theories of Personality Chapter 1Document2 pagesFeist Theories of Personality Chapter 1Rashia LubuguinNo ratings yet

Rogers 1925 A Note Plato Aristote Eng

Rogers 1925 A Note Plato Aristote Eng

Uploaded by

Diogenes Ortiz0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

13 views5 pagesRogers 1925 a note Plato Aristote eng

Original Title

Rogers 1925 a Note Plato Aristote eng

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentRogers 1925 a note Plato Aristote eng

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

13 views5 pagesRogers 1925 A Note Plato Aristote Eng

Rogers 1925 A Note Plato Aristote Eng

Uploaded by

Diogenes OrtizRogers 1925 a note Plato Aristote eng

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 5

Downloaded from http://mind.oxfordjournals.

org/ at Georgetown University on August 25, 2015

A NOTE ON SOCRATE8 AND ARIBTO'ILE.

PEBaaPithe weightiest single rerrson for holding bo the usual

opinion about the relation of ElocreLes to the Platonic philosophy,

is whet is taken to be the testimony of Aristotle to the effect that

&ratas was qnoerned only with definibions and induative in-

quiries, and did not believe in the exidenoa of eeparate Ideas,

which last heresy wee due to Plato. There are various ways of

meeting this which might be adopted by thoae who think that a

caae has been established, by Professors Burnet and Taylor in par-

ticular, for soceptingPlato's own. rait of h r a b e e as containing

a subtantiel measure of truth. g..l

s a last mrt it is always pos-

sible to fsll baak on the supposition that A r i d e is mistaken, and

was not suffiaiently aaquainted with the faate. This is not an

altogether &isfactory solution. But it is not an impossible one

provided a strong enough positive cam aan be made out for the

thing that Arietotle denies; and at least it a n n o t be dismissed

off-hand by critics who urge that Aristotle has blundered egregiously

in dmribing the ideal theory of his own teacher Plato.

9 line of attack somewhat more setisfa& would be through s

re-in~rpretetionof dristotle's evidenos. A ~ as Ia matter of fact,

there are diiliculties connected with this a rt from any particular

thesis that one may desire to see emerge. gbubtless to the modem

r d e r it will seem natural to Cake the statement aa if it meant h t

80cmks regerded the u n i v e d simp1 in a oonoeptnalistic sense ;

g

but the historicel presum tion is on b e whole against this. The

original approach of the &reek mind to the problem of the univeml

was realistic rather than psychological ; for the Pythagoreans the

number theory was underetood in a thoroughly realietia way, and

everywhere in P l a b it ii evident that the realistic point of view ie

regarded as so obvious as hardlv to need aruument. It would

a&%rdingly be W b l e bo supPo& that the sktement about the

semratenese of the Idea h e reference. in the aase of &rates iust

main Aristotle's similar statement sbbut the Pythegoreans, n i t to

a denial of realism, but simply to a failure to

==riseg

any residuum of sense over and above the ideal e ments

constitub the reality of the phenomenal world-perha s bectmma

explioitl

whic

~ocnb ~e not thought hi. way far enough into the iBal theory

to realise the problems involved. It is certainly worth noting that,

in Met. A, Plato's innovation is said to consist In the fact, not that

he made Ideas exist spar6 from sensible things by hypostashing

cronuepbe, but that he mede sensible t h i n p exiet apart from ' real '

univerda, and thus only indireably ' psrboipete ' in reality.'

The creee would be still &ro r if we muld follow Profsssor

B-et d m in ths s u p p c e i t i o n x t what Aristotle in M&. M hss

b say a b u t ' those who f h & maintained the erietenoa of Ideae ' is

meant to a ply, not b P l a b at all, but to the contemporery k o m t i o

p u p in t\e Phah.' I t is e drong argument in h m u r of this

b h , ae he points out, Arisbde expressly distinguishes the theory

he is here exemining as en eerly theory nob wnneabed with the

Downloaded from http://mind.oxfordjournals.org/ at Georgetown University on August 25, 2015

neture of nnmtmrs ; end this carbir~lya n n o t apply to the doatrim

which he commonly attributes to Pleto. S i d e r l y he speake of

oertein aonsequenoes whioh follow for the& early Ideelista, but

which the Plebniete denied.

NeverLheleaa it is not easy b avoid the impression thet the

diotum about Swratea' uts a reel, thongh not necassarily a htel,

difficulty in the way of t&a thesis. For wbsl is stated here about

those who firet mid bhat there were Ideas has previously in Met. A

been aaid ex lioitl of Plato; and one woultl not naturally have

expected (o L d the same statement made of different -ns

without some ex@enetion. Furthermore, it ie not quite easy to be

sure of the meanmg of the paasage in this new referenoe. There

is mme trouble in supposing the4 prior to Plato, the metaphysia

of the ideel theory had been worked out sufficiently to develop a

sharp diffemnoe of opinion betwean Socrebse and hie Pythagomn

~ ~ s o c i a t(oertainly

ss we should n& gether this from the Pkmk);

while if we do thlnk that SmraCes' psition is being crontnded

with e clearly consoions early theory of q a r a k i o n of a very ax-

treme type,4 we have b meet the objeotion that the separation is

not only attributed in the two con- b different persons, bub

that it mill have to h r a di&rent meaning here from the one

ven to sepamtion in Mat. A. I t appears to me that a more

k s t i o remedy is needed 0 mmove thia difioulty.

A s an eppmsch to thia it is neoesserv to examine first the earlier

peseege.' -After d e a l i v briefl with thekythagoreans, Aristotle here

oroceeds to d v e a relat~velvc L r and stramhtforward aoaount of the

bnnexion &ween them a h P h t o - a cl& cronnexion on the whole,

thongh there are several points of diffe~nce. From Heracleitns

Plato had got the ition that sensible thin are in a state of

7

flus, so that no know1 ge of them is p i b l e . F rom &-crab he

derived the insight that knowledge is m n c e r n d with definitions or

u n i v e m l a EbcreLes himself, however, had been intereabd only

in e t h i d universals; it was P l a b who turned the method into

e generel theory of knowledge, end by combining the two docbrines

' Aid. A. 6,867 b, 8.

6 h c k Ph-hy, pp. 167, 313. Cf. pp. 165 ff.

Met. M. 4, 1078 b, 30.

Cf. Taylor, Van'n 6 c m d i c u , p. 81 ff.

5 Mat. A. 6.

A NOTE ON 8 0 ~ AND

~ A~B I ~m E6. 473

WBS led not merelv to poetdata a world of Id- as the true objeat

of knowledge, but to separmte )he eeneible world from thie Re

having an esietenoe for knowledge only through ' participation ' in

the Forma Aa regard^ thb relationship of partiaiption P l a b did

not differ from the PyLhsgoreens, exmpt in using a different term

to express it. He elm egress in ~ayingthat the Numbere are the

C a U S M of the r d i t y ~f other thine. Hh d i b c l e e b y in intro-

duoing the objeobe of mathematias as inbermeiliete between sensible

t h i n p and the Forms; in hie theory of the Dyed; and in hie view

that the Numbere exist apart from sensible things, whersas the

Downloaded from http://mind.oxfordjournals.org/ at Georgetown University on August 25, 2015

Py&agorsans say that the things themaelves are Numbers.

I t would Fbpp-r, then, thet in thie earlier passege Ariabtle baa

intention of oontrasting Plato m t h Socr&m when he

spealre of t e seperstion of the Ideas. The firet etahment which

he make3 to this effect m' M aonoeiwbly have E o Q r a h in mind,

but hardly on the m a t p%able interpretation. Sooreta ap-

to be inttduued merely to axplain Plabo's acloepbenue of the method

of definition ; the thought then bo4k to the problem of know-

l e d g raised by Herealeitua. E t h i a ia not Bmrated problem ia

i n b t e d by the fmt that Saoratea has just been said to have wn-

tined hie interest to ethh, and to h v e ignored general questions

about the physical or 'seneible' world. And a little further on

Aristotle expreaaly names the Pythagoreans as t h e from whom

Plate differed on the neetion of the mparetensse of the Ideas.

We need to have %us &tisely dear -unt in mind, then, in

turning b the seoond in Mat. M? In a general wey this

seems to be modelled on the basis of the ps- in A; but the

sequence ia muoh more mnfnsed. It sets out as a oritioiem of the

ideal theory rather than ~ E I an historicre1 amount of ik I n h t h

uasea, however; a referencle to the Herauleibn doatrine ie followed

b remarks about h r a t e e ;,and while bhese remerka are d e r -

d l y more ertonded in M,they lesd in the same w e y k an h$i+

andemnation of ' those who f h t maintained the existenoe of I em

for aiviw to Ideas a serarate eristenue. It ia hew that the swcial

di&m a b u t EoQrata appsare. The passege then goes on &th a

critiaal a t t d such ae the opening sentenue would l e d ne to emect.

I t doea not take a very i&eful-reading b beoome awere thsi the

referen- to &mraCeein thb d o n hee a far less netnrel setting

than in the earlier one. The trensibion oomee indeed 8s a distinct

jolt ;and thie jolt is not lsssened on a more m f d anelyak Why,

r

when we are alread launched on an aamun&aacmrding to the

ordinary view-of P ab's theory, ehonld we hum baak mddenly to

his pred-r? An interest primirily historid, BB in A, might

furniah rseson for this ; but here it is the o r i t i d intereat that is

nppermcmt, and the referenw adds nothing to the argument. In

the first lace it is a m i o n from aritioim to hietorid apprecia-

1

tion, an to an appreuiation, furthermore, in terms of aaientific

methodology rather than of a metephyaics of the ideel theory, with

Met. K 4.

which bhe rest of the paasege is oonoerned. I t is true that t h e

h t i o episode turns to metaphyeia a t its oloae. Bub even then

bhe relevanue Lo the argument is not a p nt. Those who first

mainteined Idem, the passege runs,gmve em -te

therefore it followed for them, d m & by the seme ab-,

%" existence ;

that

there must be Ideas of all things that are spoken of u n i v e q -

But why should suah a aonolueion follow from the fact thmt the

Idem are ueparake? What it might be tho ht to follow from is

the aentenoe whioh immediately p d e s the%ratio digmion-

that if knowledge is to have an obj- there mnet be other and

Downloaded from http://mind.oxfordjournals.org/ at Georgetown University on August 25, 2015

permanent entities apart from those whioh are ~enaible;the point

would then be that the Ideas, not beuause they are eeperete, but as

the permanent elements present in &he sensible world, must exist

wherever suoh common elements are to ba discovered.

I t seems to me a probable hypothesis, therefore, that this last

repnwnts the original aonnexion, whiah would lseve the section

throughout what ah the stark it promieee to be-the criticism of a

doctrine whose historical antacedents have a l d y sufficiently been

explained. But some editor, it may lm conjeutured, finding himself

with a deteohed note aboub Soorah' contribution to scientific

method, hit upon this as a good plam to insert it, since he re-

called a former passege where a reference to &rates' metbod had

followed one to Herecleitns. To fit this note in, he supplied an

introduction and conclusion. Both are obviously reminkcant of

the former seation, though the rest of the pamage is new matter ;

and in both eases an alien hand is not difEcult to trece. The intro-

duction shows the familiar signs of a textual influence, as distinct

from independent writing, by the use of the words of the earlier

and more extended p a w in a dBerent g r a m m a t i d mnnexion,

and with a somewhat different and less appropriata meening.l And

in the conclusion the cese is still oleerer. The editor has to bring

the narrative back from methodology bo his text; and he does h i s

by repeating Aristotle's complaint that PLto gave the Ideas -re&

existence. But in doing so he falls into a misunderstending, and

interprets the failure to separate the universels as referrin to

Gmrates, whereas this was originally said by ArisbUe not a%out

8oaraCes, but about the Pythagoreans, and in a Bense whioh he

clearly explains. Its reference to &rates, on the c o n h r y , can

carry at bed a very unuertain meaning. I t is true that a litkle

later Aristotle is made to repeat incidentdy the same reference

to Socrab.? But if the origin of the first statement is as has been

suggested, there is no trouble in attributing the repetition also t o

the aame hand, espeoially as it refers back to the earlier passege a s

its o w .

%cp&uw & ucpl p i v r d jerd upcr,,ar+vcw, rrpi 8d j c OrXr/c

{em

P r a r &v, I v pi- m & a c rd coBdXw

u w r i j u a v r o s u p k v n ) v &&aav,

I ~ ~ L K &+w&

cai rrrpi +up&

k 6,987 b, 1-4. Zacpairovr 84 wrpi rds

uolJvov cai rrpi r o i r m v bpi{edor c d & u { p i m r

=+ &"1ml;l-le.

~ld

* Mef. N.9, 1088 b, E

A NOTE ON SOCRATES AND A R I B T O T L E . 475

I t remains to note briefly the bearing which this elimination

would have u n the i d m a c a t i o n of t h m who first aaid there

were 1llea.s. may be taken as almost certain that this esrly

theory is the m e 8s t h t whioh is presnpposed in ahe Phado,

and thet it differs in imporbent rticulere from the one which,

aamrding to Arinhtle, was tanggBt conaisbenkly by Plato in the

A d e m y . There is s n albrnative, however, to s u p p i n g bhet it

therefore could not have teen Plab'e ; Aristoble's words might refer

ko a n early form in whioh Plato's own doatrine was cast. I n

favour of this would be the fact that Plato is elmwhere seid to

Downloaded from http://mind.oxfordjournals.org/ at Georgetown University on August 25, 2015

have m m e to ahe theory by the errme Heraaleitean path that is

here attributed to its originators; and, in general, while some of

Aristotle's criticisms clearly refer to the Phado, the d e r hardly

geta the impression anywhere that he is confrontin in different

passaga two entirely different sets of antagonists. P aee no real

necresaity, however, for choosing between the alternatives. I n

view of the reasons Profeseor Burnet has mdduced, there seems no

g m d ground for supposing that the ideal theory represented in the

P& was not in its genere1 outlines actually held by 6ccrates,

and that Aristotle consequently did not mean to include both

Socrates and his essocietas among 'those who first maintained

the existence of Ideas'. But also I see no need for refusing to

s u p p s e that P l a b himeelf was in an earlier period a Socretic, and

thet Arisbokle therefore may not have thought of him, too,as in a

sense a member of the group which he introduces in a wey so

almost studiously indefinite. I t would appear indeed to have b e n

from the less developed form of the doctrine that Aristotle gets a

g d Bhare of his evidenoa for Plato's aeparatiou of the Ideas ; and

this may very well have predisposed him to continue to find

difficdbiea in the maturer theory which, in view of Plato's c h a n ~

of emphasis, would not otherwise have loomed es large.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5834)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (350)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (824)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (405)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Wason's Selection TaskDocument5 pagesWason's Selection TaskMiss_M90100% (2)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Legal ResearchDocument10 pagesLegal ResearchAnu Lahan OnifadeNo ratings yet

- Article Writing Subjek IctDocument3 pagesArticle Writing Subjek IctAnida AhmadNo ratings yet

- Arts-Informed Research - Cole, KnowlesDocument16 pagesArts-Informed Research - Cole, KnowlesGloria LibrosNo ratings yet

- ThinkingDocument6 pagesThinkingNupur PharaskhanewalaNo ratings yet

- The Contribution of Native Ethiopian Philosophers - Zara Yacob and Wolde Hiwot - To Ethiopian Philosophy by Tassew AsfawDocument17 pagesThe Contribution of Native Ethiopian Philosophers - Zara Yacob and Wolde Hiwot - To Ethiopian Philosophy by Tassew Asfawillumin7No ratings yet

- National Science Education Standards Compare NGSS To Existing State Standards About The Next Generation Science StandardsDocument3 pagesNational Science Education Standards Compare NGSS To Existing State Standards About The Next Generation Science StandardsROMEL A. ESPONILLANo ratings yet

- Reflection Paper-The Nature of Science and of Theories On OriginDocument2 pagesReflection Paper-The Nature of Science and of Theories On OriginKarl Kristian TolarbaNo ratings yet

- Education and PhilosophyDocument2 pagesEducation and PhilosophySuraj TupeNo ratings yet

- 48 Critical Thinking Questions For Any Content AreaDocument10 pages48 Critical Thinking Questions For Any Content AreaZady Zalexx100% (1)

- Useful Sentences For Essay WritingDocument4 pagesUseful Sentences For Essay Writingmithil1111111No ratings yet

- 5AANB011 Philosophy of Logic and Language Lectures Spring Term 2012Document2 pages5AANB011 Philosophy of Logic and Language Lectures Spring Term 2012BETSIE BAHRUNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 - Developing Research SkillsDocument13 pagesChapter 2 - Developing Research SkillsArly TolentinoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1: Meaning and Characteristics of ResearchDocument6 pagesChapter 1: Meaning and Characteristics of ResearchMagy Tabisaura GuzmanNo ratings yet

- 9th Advt of INSPIRE Fellowship List of 114 Rejected Applications in Level - 2 Evaluation PDFDocument4 pages9th Advt of INSPIRE Fellowship List of 114 Rejected Applications in Level - 2 Evaluation PDFAayushi VermaNo ratings yet

- Dr. Maheswari JaikumarDocument34 pagesDr. Maheswari JaikumarNors Cruz100% (1)

- Experimentalism and PragmatismDocument17 pagesExperimentalism and PragmatismLagman Danielle JohnsNo ratings yet

- Poststructuralism (Derrida and Foucault)Document4 pagesPoststructuralism (Derrida and Foucault)ROUSHAN SINGHNo ratings yet

- IB TOK 1 Resources NotesDocument85 pagesIB TOK 1 Resources Notesxaglobal100% (1)

- 7 Theory of Knowledge Day OneDocument10 pages7 Theory of Knowledge Day OneimNo ratings yet

- Knowledge ManagementDocument13 pagesKnowledge ManagementAchutReddy0% (1)

- The Scientific Method: Formal Vs Everyday ApplicationDocument2 pagesThe Scientific Method: Formal Vs Everyday ApplicationArc RenNo ratings yet

- HRE 121 Research in Daily Life 2: Senior High SchoolDocument17 pagesHRE 121 Research in Daily Life 2: Senior High SchoolChristian Dave EvangelistaNo ratings yet

- OneDocument7 pagesOneapi-499953196No ratings yet

- Graduate Courses & Seminars - Department of Philosophy - UCLADocument3 pagesGraduate Courses & Seminars - Department of Philosophy - UCLARaghu YadavNo ratings yet

- Joseph Keim Campbell, Michael O'Rourke, Harry S. Silverstein - Causation and Explanation (Topics in Contemporary Philosophy) (2007) PDFDocument335 pagesJoseph Keim Campbell, Michael O'Rourke, Harry S. Silverstein - Causation and Explanation (Topics in Contemporary Philosophy) (2007) PDFMaghiar Manuela PatriciaNo ratings yet

- Developing Manual Practicum Book Integrated Science Junior High School Based Home Materials To Build Students' CharacterDocument10 pagesDeveloping Manual Practicum Book Integrated Science Junior High School Based Home Materials To Build Students' CharacterNanang RahmanNo ratings yet

- Quotations RationalityDocument81 pagesQuotations Rationalitylairdwilcox100% (2)

- Knowledge Management Techniques in B - Schools - With Special Reference To Entry and Exit PointsDocument6 pagesKnowledge Management Techniques in B - Schools - With Special Reference To Entry and Exit PointsTyrone RiddleNo ratings yet

- Feist Theories of Personality Chapter 1Document2 pagesFeist Theories of Personality Chapter 1Rashia LubuguinNo ratings yet