Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Lesson 4 - Assessment Traditions and Principles

Lesson 4 - Assessment Traditions and Principles

Uploaded by

Erika Quindipan0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

16 views5 pages- Large-scale assessments traditionally take a psychometric perspective focused on measuring outcomes, while classroom assessments examine student thinking and learning processes.

- Both assessment types should support student learning, reflect important mathematics, and provide opportunities for students to demonstrate their knowledge.

- While formats differ, common principles like problem solving, modeling, and representing the complex nature of mathematics should be valued in both large-scale and classroom assessments.

Original Description:

Original Title

Lesson 4- Assessment Traditions and principles

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Document- Large-scale assessments traditionally take a psychometric perspective focused on measuring outcomes, while classroom assessments examine student thinking and learning processes.

- Both assessment types should support student learning, reflect important mathematics, and provide opportunities for students to demonstrate their knowledge.

- While formats differ, common principles like problem solving, modeling, and representing the complex nature of mathematics should be valued in both large-scale and classroom assessments.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

16 views5 pagesLesson 4 - Assessment Traditions and Principles

Lesson 4 - Assessment Traditions and Principles

Uploaded by

Erika Quindipan- Large-scale assessments traditionally take a psychometric perspective focused on measuring outcomes, while classroom assessments examine student thinking and learning processes.

- Both assessment types should support student learning, reflect important mathematics, and provide opportunities for students to demonstrate their knowledge.

- While formats differ, common principles like problem solving, modeling, and representing the complex nature of mathematics should be valued in both large-scale and classroom assessments.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 5

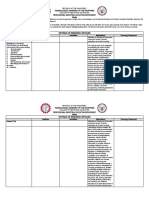

Assessment Traditions

Large-scale assessment and classroom assessment have different

traditions/backgrounds, having been influenced in different ways by learning theories and

perspectives (Glaser and 2 State of the Art 3 Silver 1994).

Large-scale assessment traditionally comes from a psychometric/ measurement

perspective, and is primarily concerned with scores of groups or individuals, rather than

examining students’ thinking and communication processes.

A psychometric perspective is concerned with reliably measuring the outcome of

learning, rather than the learning itself (Baird et al. 2014).

The types of formats traditionally used in large-scale assessment are mathematics

problems that quite often lead to a single, correct answer (Van den Heuvel-Panhuizen and

Becker 2003).

Some might see these types of questions as more aligned with a behaviourist or

cognitivist perspective as they typically focus on independent components of knowledge

(Scherrer 2015).

A focus on problems graded for the one right answer is sometimes in conflict with

classroom assessments that encourage a range of responses and provide opportunities for

students to demonstrate their reasoning and creativity, and work is being done to examine large-

scale assessment items that encourage a range of responses.

Current approaches to classroom assessment have shifted from a view of assessment

as a series of events that objectively measure the acquisition of knowledge toward a view of

assessment as a social practice that provides continual insights and information to support

student learning and influence teacher practice.

These views draw on cognitive, constructivist, and sociocultural views of learning (Gipps

1994; Lund 2008; Shepard 2000, 2001).

Gipps (1994) suggested that the dominant forms of large-scale assessment did not seem

to have a good fit with constructivist theories, yet classroom assessment, particularly formative

assessment, did.

Further work has moved towards socio-cultural theories as a way of theorizing work in

classroom assessment as well as understanding the role context plays in international assessment

results.

Common Principles

There are certain principles that apply to both large-scale and classroom assessment.

Although assessment may be conducted for many reasons, such as reporting on students’

achievement or monitoring the effectiveness of an instructional program, several suggest

that the central purpose of assessment, classroom or large-scale, should be to support and

enhance student learning (Joint Committee on Standards for Educational Evaluation 2003;

Wiliam 2007).

Even though the Assessment Standards for School Mathematics from the National

Council of Teachers of Mathematics in the USA (NCTM 1995) are now more than 20 years old,

the principles they articulate of ensuring that assessments contain high quality mathematics,

that they enhance student learning, that they reflect and support equitable practices, that

they are open and transparent, that inferences made from assessments are appropriate to

the assessment purpose, and that the assessment, along with the curriculum and

instruction, form a coherent whole are all still valid standards or principles for sound

large-scale and classroom assessments in mathematics education.

Assessment should reflect the mathematics that is important to learn and the

mathematics that is valued. This means that both large-scale and classroom assessment

should take into account not only content but also mathematical practices, processes,

proficiencies, or competencies (NCTM 1995, 2014; Pellegrino et al. 2001; Swan and Burkhardt

2012).

Consideration should be given as to whether and how tasks assess the complex

nature of mathematics and the curriculum or standards that are being assessed.

In both large-scale and classroom assessment, assessment design should value problem

solving, modelling, and reasoning.

The types of activities that occur in instruction should be reflected in assessment.

As noted by Baird et al., “Assessments define what counts as valuable learning and

assign credit accordingly” (2014, p. 21), and thus, assessments play a major role in

proscribing what occurs in the classroom in countries with accountability policies

connected to high-stakes assessments. That is, in many countries the assessed curriculum

typically has a major influence on the enacted curriculum in the classroom.

Furthermore, assessments should provide opportunities for all students to

demonstrate their mathematical learning and be responsive to the diversity of learners

(Joint Committee on Standards for Educational Evaluation 2003; Klieme et al. 2004; Klinger et

al. 2015; NCTM 1995).

In considering whether and how the complex nature of mathematics is represented in

assessments, it is necessary to consider the formats of classroom and large-scale assessment

and how well they achieve the fundamental principles of assessment.

For instance, the 1995 Assessment Standards for School Mathematics suggested that

assessments should provide evidence to enable educators “(1) to examine the effects of the

tasks, discourse, and learning environment on students’ mathematical knowledge, skills,

and dispositions; (2) to make instruction more responsive to students’ needs; and (3) to

ensure that every student is gaining mathematical power” (NCTM, p. 45).

These three goals relate to the purposes and uses for both large-scale and classroom

assessment in mathematics education.

The first is often a goal of large-scale assessment as well as the assessments used by

mathematics teachers.

The latter two goals should likely underlie the design of classroom assessments so that

teachers are better able to prepare students for national examinations or to use the

evidence from monitoring assessments to enhance and extend their students’ mathematical

understanding by informing their instructional moves.

Classroom teachers would often like to use the evidence from large-scale assessments

to inform goals two and three and there are successful examples of such practices (Boudett

et al. 2008; Boudett and Steele 2007; Brodie 2013) where learning about the complexity of

different tasks or acquiring knowledge about the strengths and weaknesses of one’s own

instruction can inform practice.

However, this is still a challenge in many parts of the world given the nature of the tasks

on large-scale assessments, the type of feedback provided from those assessments, and the

timeliness of that feedback.

Table 1 provides a sample of assessment goals that are taken from different

perspectives and assessment purposes. Looking across the columns of the table, there are

similarities in the goals for assessment that should inform the design of tasks, whether the

tasks are for formative assessment, for competency models, or for high-stakes assessment;

in fact, they typically interact with each other.

Specifically, teachers and students need to know what is expected which implies that

tasks need to align with patterns of instruction, tasks need to provide opportunities for students to

engage in performance that will activate their knowledge and elicit appropriate evidence of

learning, the assessment should represent what is important to know and to learn, and when

feedback is provided it needs to contain enough information so that students can improve their

knowledge and make forward progress. These common goals bear many similarities to the 1995

NCTM principles previously discussed.

You might also like

- Mindset TB L3Document16 pagesMindset TB L3shanekeeling10150% (8)

- Handout - Topic 4 - Interactions of Large-Scale and Classroom AssessmentDocument6 pagesHandout - Topic 4 - Interactions of Large-Scale and Classroom AssessmentJannine Cabrera PanganNo ratings yet

- KCSE Revision Work Book Mathematics Paper - 1Document148 pagesKCSE Revision Work Book Mathematics Paper - 1luballomuyoyo100% (1)

- Don't Apply For A Job at The CIA-You Might Be Interviewed by An Alien by Elaine DouglassDocument41 pagesDon't Apply For A Job at The CIA-You Might Be Interviewed by An Alien by Elaine Douglassmikeclelland100% (3)

- IV. Implications For Assessment Design The Design and Use of Classroom AssessmentDocument6 pagesIV. Implications For Assessment Design The Design and Use of Classroom AssessmentChristine ApriyaniNo ratings yet

- CHPT 3&4Document13 pagesCHPT 3&4jyua9946No ratings yet

- CCE - NCERT Source Book FrameworkDocument101 pagesCCE - NCERT Source Book Frameworktellvikram100% (1)

- Formative Assessment For Next Generation Science Standards: A Proposed ModelDocument28 pagesFormative Assessment For Next Generation Science Standards: A Proposed ModelgulNo ratings yet

- Local Media1240772049276078473Document14 pagesLocal Media1240772049276078473jiaNo ratings yet

- Assignment 5053Document21 pagesAssignment 5053Rosazali IrwanNo ratings yet

- Criteria 1Document21 pagesCriteria 1Estela ChevasNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Evaluation: Weeks 10 and 11Document39 pagesCurriculum Evaluation: Weeks 10 and 11April Rose Villaflor Rubaya100% (1)

- 978 3 319 63248 3 - 3 Exploring Relations Between FormativeDocument28 pages978 3 319 63248 3 - 3 Exploring Relations Between FormativefidyaNo ratings yet

- What Are The Major Purposes of Assessment in Education?Document24 pagesWhat Are The Major Purposes of Assessment in Education?Hwee Kiat Ng67% (3)

- Evidence of Testing and Evidence of Advocacy and Mentoring - TemplateDocument4 pagesEvidence of Testing and Evidence of Advocacy and Mentoring - TemplateraviNo ratings yet

- Classroom Assessment Techniques: An Assessment and Student Evaluation MethodDocument5 pagesClassroom Assessment Techniques: An Assessment and Student Evaluation MethodPutri RahmawatyNo ratings yet

- Evaluation Assessment and TestingDocument6 pagesEvaluation Assessment and TestingBe Creative - كن مبدعاNo ratings yet

- Summary Chapter 11Document9 pagesSummary Chapter 11IO OutletsNo ratings yet

- Educational Assessment: Are We Doing The Right Thing Dr. Frank Tilya University of Dar Es SalaamDocument14 pagesEducational Assessment: Are We Doing The Right Thing Dr. Frank Tilya University of Dar Es SalaamYvonna NdibalemaNo ratings yet

- Chapter5 PDFDocument15 pagesChapter5 PDFairies92No ratings yet

- Quadrante VolXII 1 Art Morgan 48160362473eeDocument16 pagesQuadrante VolXII 1 Art Morgan 48160362473eePengki yudistiraNo ratings yet

- Norm and Criterion-Referenced TestsDocument5 pagesNorm and Criterion-Referenced TestsBenjamin L. Stewart100% (4)

- Than PaingDocument3 pagesThan Paingthanpaing131203No ratings yet

- Assessment PlanningDocument17 pagesAssessment PlanningolivaparlemoNo ratings yet

- RTL Assessment TwoDocument11 pagesRTL Assessment Twoapi-331867409No ratings yet

- Principles of Assessment - Docx Noman ZafarDocument9 pagesPrinciples of Assessment - Docx Noman ZafarMujahid AliNo ratings yet

- What You Measure Is What You GetDocument3 pagesWhat You Measure Is What You GetBondtwitNo ratings yet

- MODULEDocument12 pagesMODULEJoy Ann BerdinNo ratings yet

- DWYER Assessment and Classroom Learning Theory and PracticeDocument8 pagesDWYER Assessment and Classroom Learning Theory and PracticeSAMIR ARTURO IBARRA BOLAÑOSNo ratings yet

- In-Course Optimization of Teaching QualityDocument8 pagesIn-Course Optimization of Teaching QualitySwapan Kumar KarakNo ratings yet

- Basic Concepts in Assessment 1Document55 pagesBasic Concepts in Assessment 1Michael BelludoNo ratings yet

- ASSIGNMENTDocument12 pagesASSIGNMENTAjimotokan Adebowale Oluwasegun MatthewNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1. Measurement Assessment and EvDocument6 pagesChapter 1. Measurement Assessment and EvAkari ChanNo ratings yet

- Assessment and EvaluationDocument38 pagesAssessment and EvaluationJefcy NievaNo ratings yet

- Hammerman, Formative Assessment CH 1Document14 pagesHammerman, Formative Assessment CH 1zeinab15No ratings yet

- Supporting Primary School Teachers ' Classroom Assessment in Mathematics Education: Effects On Student AchievementDocument23 pagesSupporting Primary School Teachers ' Classroom Assessment in Mathematics Education: Effects On Student AchievementWong Yan YanNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2 Part BDocument4 pagesAssignment 2 Part Bapi-478706872No ratings yet

- ST STDocument4 pagesST STNurfaradilla NasriNo ratings yet

- Marshi 1Document15 pagesMarshi 1zlie79No ratings yet

- Student Feedback On Teachers and Its Practices: 1. Clarify Context and FocusDocument4 pagesStudent Feedback On Teachers and Its Practices: 1. Clarify Context and FocusVishal KumarNo ratings yet

- Basic Assessment Concepts For Teachers and School Administrators. ERIC/AE DigestDocument14 pagesBasic Assessment Concepts For Teachers and School Administrators. ERIC/AE DigestRyan CurtisNo ratings yet

- Ped06 MaterialsDocument70 pagesPed06 MaterialsChloe JabolaNo ratings yet

- Module 6 Curriculum EvaluationDocument5 pagesModule 6 Curriculum Evaluationreyma panerNo ratings yet

- ASSESSMENT IN LEARNING 1 Module 1Document53 pagesASSESSMENT IN LEARNING 1 Module 1Princess Joy ParagasNo ratings yet

- Research On Classroom Summative AssessmentDocument20 pagesResearch On Classroom Summative AssessmentYingmin WangNo ratings yet

- Formative and Summative Assement ProposalDocument10 pagesFormative and Summative Assement Proposalhaidersarwar100% (1)

- Procedures Used in Summative AssessmentDocument2 pagesProcedures Used in Summative Assessmentapi-93111231No ratings yet

- Principles of Classroom AssessmentDocument5 pagesPrinciples of Classroom Assessmentapi-405351173No ratings yet

- The Concepts of TestDocument8 pagesThe Concepts of TestSher AwanNo ratings yet

- Validity of Educational IndicatorsDocument7 pagesValidity of Educational IndicatorsAldo FjeldstadNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 AssessDocument11 pagesChapter 1 AssessLiezel AlquizaNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Learning 1 Chapter 1Document9 pagesAssessment of Learning 1 Chapter 1AlexNo ratings yet

- 8602 Assignment AnswerDocument16 pages8602 Assignment Answernaveed shakeelNo ratings yet

- The University of Hong Kong The University of AucklandDocument10 pagesThe University of Hong Kong The University of AucklandMarwiah RasyaNo ratings yet

- Assessing So TLDocument15 pagesAssessing So TLابو مريمNo ratings yet

- Designing Classroom AssessmentDocument21 pagesDesigning Classroom Assessmentkencana unguNo ratings yet

- Assessment and EvalautionDocument55 pagesAssessment and EvalautionMohammed Demssie MohammedNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 The Concept of Curriculum EvaluationDocument6 pagesUnit 1 The Concept of Curriculum EvaluationMoselantja MaphatsoeNo ratings yet

- Formative Assessment in A Science ClassDocument18 pagesFormative Assessment in A Science ClassEmman Acosta DomingcilNo ratings yet

- Educ6 Prelim m1Document30 pagesEduc6 Prelim m1Lovely ToldanesNo ratings yet

- Profed 06 Lesson 1Document13 pagesProfed 06 Lesson 1Marvin CariagaNo ratings yet

- Assessment Learning 1Document4 pagesAssessment Learning 1rieann leonNo ratings yet

- Teaching Mathematics in the Middle School Classroom: Strategies That WorkFrom EverandTeaching Mathematics in the Middle School Classroom: Strategies That WorkNo ratings yet

- Health7 Q2 Mod6ApplyDecisionMakingSkills v2Document24 pagesHealth7 Q2 Mod6ApplyDecisionMakingSkills v2Erika QuindipanNo ratings yet

- Summative Test (Mapeh-7)Document5 pagesSummative Test (Mapeh-7)Erika QuindipanNo ratings yet

- Arts 7 - Module 3 and 4Document47 pagesArts 7 - Module 3 and 4Erika QuindipanNo ratings yet

- Exercises (Geometric Sequence)Document1 pageExercises (Geometric Sequence)Erika QuindipanNo ratings yet

- Contributions of The FollowingDocument4 pagesContributions of The FollowingErika QuindipanNo ratings yet

- Office of The Laboratory Schools: WWW - Unp.edu - PHDocument11 pagesOffice of The Laboratory Schools: WWW - Unp.edu - PHErika QuindipanNo ratings yet

- Statistics (Part 1)Document98 pagesStatistics (Part 1)Erika QuindipanNo ratings yet

- Erika A. Quindipan October 18, 2021 Bsed Math 4-C What Are The Disadvantages of The Advancement of Science & Technology?Document2 pagesErika A. Quindipan October 18, 2021 Bsed Math 4-C What Are The Disadvantages of The Advancement of Science & Technology?Erika QuindipanNo ratings yet

- Plane and Solid GeometryDocument5 pagesPlane and Solid GeometryErika QuindipanNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines: WWW - Unp.edu - PHDocument2 pagesRepublic of The Philippines: WWW - Unp.edu - PHErika QuindipanNo ratings yet

- The Purposes of Educational Research Learning OutcomesDocument3 pagesThe Purposes of Educational Research Learning OutcomesErika Quindipan100% (1)

- Greek MathematicsDocument23 pagesGreek MathematicsErika QuindipanNo ratings yet

- Benjamin BannekerDocument53 pagesBenjamin BannekerErika QuindipanNo ratings yet

- Andrey Nikolayevich KolmogorovDocument12 pagesAndrey Nikolayevich KolmogorovErika QuindipanNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Matiiematical EconomicsDocument5 pagesIntroduction To Matiiematical EconomicsNeeresh KumarNo ratings yet

- Centre For Distance and Virtual Learning: University of HyderabadDocument27 pagesCentre For Distance and Virtual Learning: University of HyderabadGOWTHAMNo ratings yet

- Effects of Mastery Learning Instruction On Engineering Students Writing Skills Development and MotivationDocument11 pagesEffects of Mastery Learning Instruction On Engineering Students Writing Skills Development and MotivationRanii raniNo ratings yet

- Compex Modules Ex01 - EX04Document3 pagesCompex Modules Ex01 - EX04Grid LockNo ratings yet

- 2003 Undergraduate Medical Curriculum The Lessons LearnedDocument14 pages2003 Undergraduate Medical Curriculum The Lessons Learnedjoaopmc.mNo ratings yet

- Capstone ProcessesDocument19 pagesCapstone ProcessesAbigail Villanueva GamboaNo ratings yet

- PrelimDocument9 pagesPrelimbrice burgosNo ratings yet

- Into To World of CPAsDocument22 pagesInto To World of CPAsKristine WaliNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Critique GuideDocument11 pagesResearch Paper Critique GuideJunkoNo ratings yet

- Soci-101-Principles of SociolDocument4 pagesSoci-101-Principles of SocioltucchelNo ratings yet

- Praxis ScoresDocument3 pagesPraxis Scoresapi-317240579No ratings yet

- JsuDocument2 pagesJsuAmelia AyNo ratings yet

- Procedure at SSB: Stage FirstDocument2 pagesProcedure at SSB: Stage FirstIrfan MullaNo ratings yet

- Components of A Research Proposal PDFDocument13 pagesComponents of A Research Proposal PDFalithasni45No ratings yet

- How Do I Write A ReportDocument2 pagesHow Do I Write A ReportDr_M_Soliman100% (1)

- Bulletin: Post Doctoral / Graduate Fellowship AdmissionsDocument8 pagesBulletin: Post Doctoral / Graduate Fellowship AdmissionsissacgohanNo ratings yet

- Examen Japones de Ortografia ChileDocument40 pagesExamen Japones de Ortografia ChileMario BownstherNo ratings yet

- University of Eastern PhilippinesDocument7 pagesUniversity of Eastern PhilippinesDelos Santos Estieve NielwardNo ratings yet

- Modified MSEDocument11 pagesModified MSEOliveth Jumalon Pajente-PelagioNo ratings yet

- Pharmacist 06-2013Document15 pagesPharmacist 06-2013PRC BaguioNo ratings yet

- Power System Analysin ScheduleDocument10 pagesPower System Analysin ScheduleABDUL HASEEBNo ratings yet

- Leadership and Management of Health and SafetyDocument20 pagesLeadership and Management of Health and SafetyitapiazNo ratings yet

- Roll Number Slip PDFDocument2 pagesRoll Number Slip PDFM Arslan AshrafNo ratings yet

- University of Caloocan City Graduate SchoolDocument13 pagesUniversity of Caloocan City Graduate SchoolMARLON MARTINEZNo ratings yet

- Comprehensive Interest TestDocument2 pagesComprehensive Interest TestDaniel Lz TluangaNo ratings yet

- QMS Audit Checklist 2 - Basic Production ProcessDocument1 pageQMS Audit Checklist 2 - Basic Production ProcessFlorina GasparNo ratings yet

- CAP Squadron Visitor Guide (2000)Document8 pagesCAP Squadron Visitor Guide (2000)CAP History LibraryNo ratings yet