Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Report 14 Vol 1

Report 14 Vol 1

Uploaded by

VarunPratapMehta0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

4 views660 pagesOriginal Title

Report14Vol1[1]

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

4 views660 pagesReport 14 Vol 1

Report 14 Vol 1

Uploaded by

VarunPratapMehtaCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

You are on page 1of 660

LAW COMMISSION OF INDIA

M. C. Setalvad, LAW COMMISSION

5, Jor Bagh,

New Delhi-3,

: September 26, 1958.

Shri Ashok Kumar Sen,

Minister of Law,

. New Delhi.

My Dear MrnisTER,

I have great pleasure in forwarding herewith the -fourteenth

Report of the Law Commission om the Reform of Judicial Adminis-

ation. .

2. The appointment of the Commission was announced by B bond

predecessor in the Lok Sabha on fhe 5th August, 1955, and the Mem-

bers of the Commission assumed their office on the 16th September,

1955.. The: Commission has sincebeen .engazed, among other thin,

in investigating the system of juditial administration in this country.

3 3. For various. réasons the inquiry has taken a longer time than

" was originally anticipated. While an attempt has been made to ge

into all"the matters covered by the terms of reference, we have

obvious reasons, not entered into a detailed examination of either of

the procedural codes or of the law of evidence with a view to

suggesting amendments. We have confined ourseleves to indicating

in broad outline the changes that would be necessary to make

judicial administration speedy and less expensive.

4. The detailed examination and revision of the codes of civil and

criminal procedure is a task which calls for considerable time. Su¢h

a revision on the basis of our general recommendations will have fo

be undertaken hereafter. :

3 5. The manner in which the Commission conducted its invest:

; tions in this branch of its inquiry has been set forth at I in the

4) introductory chapter. The large volume of material collected fér

ti this pores was put into the shape of notes for a draft report by

“! the Secretariat of the Commission. A draft report was then pre-

pared and circulated to the members. The draft was after a fnal

discussion settled by the Chairman.

a

6. I would like in this connectien to express my gratitude to my

colleagues for the assistance and the co-operation which I have

j received from’ them during the course of the Commission’s enquiries

and deliberations.

7. I would like to acknowledge the able assistance rendered in

the course of the Commission’s inquiries and in the drafting and the

completion of the Report by the officers of the Commission. The

Joint Secretary, Shri K. Srinivasan has brought to this work not

only a wide knowledge of the working of civil and criminal courts

byt wlso:administyative ability of a high order. Shri R. M. Meht

the Deputy Secretary, did ve valuable work in the field of cit

law and in Spe ee a Nenkatasubramanian, the fear

man’s, ial Assistant did indefatigable work in gathering valuable

iene ‘and putting into shape various parteoof the Report

, f+ Shri,G. S. Pathak being outside India is unable to sign the

e] , but ie concurs in the recommendations and has authorised

{he Chairman to sign the Report on his behalf: Dr..N. C. Sen Guptix,

Shri V. K. T. Chari and Shri D. Narasa Raju who ere unable to come

cine to Delhi, similarly concur in the recommendations and have

aut ii the Chairman to sign the Report on their behalf.

9. Dr. N. C. Sen Gupta and Shri V. K. T. Chari have signed the

Report subject to their separate motes which are annexed to the

Report.

-« 10. With this Report, the Comu@ssion, -é8-at present constituted

concludes its labours. The task of revising the Central Acts of ge

importance and making suggestiong for the reform of the Jaw is,

Newever, far ftom beitg-ovér. . Mae of the uridertaken in this

eéanection is still unffAi: and He te be cortipleted.

J], In conclusion, the Cemmissidn. wishes to;acknowledge the un~

eudging services rendered to it by its entive staff.

‘Yours sincerely,

28. 'C. SEPALVAD:

CHAPTERS Vor. I

1. Introductory. 6) et

2. Historical . 5 . . . .

3. The Judicial System. 5 +e .

4 Indigenous System = - . . . .

5. The SupremeCourt . - + +

6. High Courts eee

7. High Courts—Origina Side.

8 Adequacy of Judicial Strength . - +

9. Subordinate Judiciary Baa

10. Supervision and control of subordina‘e courts

11. Delays in Civil Proceedings 9 - + +

12. Jurisdiction of Civil Courts aeerieaeny)

13. Courts of small Causes . . . .

4 TribofSuits 2. 0. +

15. Civil Appeals

16. Civil Appellate Procedure. -

17. Civil Revisions - . . . . .

18. Execution of decrees . ie .

1g. Written Arguments - + + + +

20. Suits against Government . + + +

an Cots 6 Ft

a2. CoutFes - - + te

23. Insolvency ieee eevee a tdteeea

24- The Lew of evidence . . eee

25. Legal Education . . aaaaie .

26. TheBrs - * + + 8

27. Legal Aid . . . . fee

28.

29

‘Law Reports. . ee . .

‘Language . . . . ee .

Paca him

9

1086

17—03

24——3t

32—t

6g

112138

129—160

161229 *

230—251

252—a63

264-277

2780496

2970361

36ammpB4

38Somg12

413-430

BImniie

S874

47976

477-86

Sigs

S16—819

520-355

55686

387404,

525-06

67896

1—INTRODUCTORY

Ever since Independence, suggestions were made in and

outside Parliament for the appointment of a Law Com-

mission for examining the entra Acts and recommend-

ing the lines on which they should be amended, revised or

consolidated,

‘On the 2nd December 1947 Dr. Sir Hari Singh Gour

moved a resolution in the Constituent Assembly (Legisla-

tive) recommending the establishment of a Statutory Law

Revision Committee to ‘clarify and settle questions of

law which required elucidation. The resolution was,

however, withdrawn by the, mover upon an assurance

being given by the then Law Minister, Dr. Ambedkar, that

Government would try td devise some other suitable

machinery for revising laws, One of the methods by

which the work of law revision could be undertaken was

stated by Dr. Ambedkar to be a permanent Commission

which would be entrusted solely with the work of revising

and codifying the laws.

The advisability of creating a Law Commission was.

again stressed in the Lok Sabha on the 27th June 1952 by

Shri N. C. Chatterjee, on a discussion on the Motion for

Demands for the Ministry of; Law.* In the course of his

speech-on the occasion, the then Law Minister Shri C. C.

Biswas stated that the Government recognised that the

work of keeping the law up4o-date was one of vital im-

portance and he gave an assutance that the question would

be examined by Government and necessary steps would be

taken.

On the 26th of July 1954 ithe AllsIndia Congress Com-

mittee resolved that “a Law Commission should be

appointed as in England to iE ise the laws promulgated

nearly a century back by the Law Commission of Macaulay

and to advise on current legislation from time to time”.

The genesis of the present Commission lies in a non-

official resolution moved in ‘the Lok Sabha on the 19th

November 1954. The contents of that resolution were:

“This House resolves that a Law Commission be

appointed to recommend) revision and modernization

of laws, criminal, civil revente, substantive, proce-

dural or otherwise and jin particular, the Civil and

Criminal Procedure Codes and the Indian Penal Code,

to reduce the quantum of'case-law and to resolve the

conflicts in the decisions of the High Courts on many

points with a view to realise that justice is simple,

speedy, cheap, effective rt substantial.”

i

*House of the People Debates, 1452, Vol. Ilf, ediumn 2690.

315 MofL—1

2

In the course of |further discussion on this resdlution

in the Lok Sabha the 3rd December 1954 the ‘ime

Minister, Shri Jawaarlal Nehru, made a statemenf that

the Government hadj accepted the resolution in so far as

the appointment of the Law Commission was conderned

and that Governmerg were even then “engaged in jconsi-

dering the steps to taken towards that end”. In view

of the acceptance by the Prime Minister of the pripciple

underlying the resol¥tion, tht resolution was withdzawn.

2. Though the suy

assurances given by

revision and model

pose as stated in t!

1954 was “to realise:

effective and substai

merely by revision

also overhauling th

The growing accumt

Courts and subordins

necessitated a caret

proper functioning

Presumably these

ambit of the activiti

ation @f laws, the underlyin,

is simple, speedy,

is'aim could not be a

Wid simplification of the laws but reeds.

system!of administration of jestice.;:

lation of arrears in the various| High

e courts had created a situation 4

examifation of the problem @f the

the ‘machinery of the

sons led Government to wit

s of thé proposed Law Comm

the subject of the reform of j

administration, 2

3. On the Sth of

Cc. C. Biswas, made’

Sabha announcing

appoint a Law Com:

of reference.

Augusti1955 the Law Ministeq.

the following statement in the Lok

le Goveymment of India’s decisfon te

ission, its membership and the Res .

ta

sion should be

and suggesting 4

system of judic

‘ en :

(1) Shri] M. ¢ Betalvad, Attorney-Gend

mn), Hf

Phagla, Chief Justice

3

*{4) Shri G. N. Das, retired Judge of the

Calcutta High Court,

(5) Shri P. Satyanarayana Rao, retired Judge

of the Madras High Court,

(6) Dr. N. C. Sen Gupte, Advocate, Caleutta,

(7) Shri V. K, T. Chari, Advocate-General,

Madras,

(8) Shri Narasa Raju, Advocate-General,

Andhra,

(9) Shri S. M. Sikri, Advocate-General,

Punjab,

(10) Shri G. S, Pathak, Advocate, Allahabad,

(11) Shri G. N. Joshi, Advocate, Bombay,

The terms of reference to the Commission will

firstly, to review the sysiem of judicial administra-

tion in all its aspects and suggest ways and means for

improving it and making it speedy and less expensive;

secondiy, to examine the Central Acts of general

application and importasce, and recommend the line on

which they should be amended, revised, consolidated

or otherwise brought up-to-date.

4, With regard to the first term of reference, the

Commission’s inquiry ‘into the system of judicial

administration will be comprehensive and thorough,

including in its scope,—

(a) the operatign and_ effect of laws, sub-

stantive as well as, procedural, with a view to

eliminating unnecesgary litigation, speeding up the

disposal of cases and making justice less expensive;

(b) the organigation of courts, both civil and |

criminal; ’ , .

(e) recruitment of the judiciary; and

(@) level of thi{ bar angi of legal education.

5. With regard to ib second term cf reference, the

Commission’s principal‘iobjectives in the revision of

existing legislation will be—

{a) to simplify‘ithe laws in general, and the

procedural laws in garticular,

* Resigned on 33st December 55.

4

(b) to ascertain if any provisions are inconsis—

tent with the Constitution and suggest the necessary

alterations or omissions,

(c) to remove anomalies and ambiguities.

brought to light by conflicting decisions of High

Courts or otherwise,

(a) to consider local variations introduced by

State legislation in the concurrent field, with a view

to reintroducing and maintaining uniformity,

(e) to consolidate Acts pertaining to the same

subject with such technical revision as may be

found necessary, and

(2) to suggest modifications wherever neces-

sary for implementing the directive principles of

State policy laid down in the Constitution.

6. In order to perform its task expeditiously and

efficiently, the Commission will function in two

sections. The first section consisting of the Chairman

and the first three members will deal mainly with the

question of the reform of judicial administration, while

the second section consisting of other seven members.

will be mainly concerned with statute law revision on

the lines indicated above. The two sections, however,

will work in close co-operation with each other under

the direction of the Chairman.

7. The Chairman of the Commission may at his

discretion co-opt as members one or two prac' iz

lawyers of a State in order to assist the Commissjon’s.

inquiries in that State.

8. The Commission is appointed in the first instance

upto the end of the ear 1956. Its headquarters wil}

be at New Delhi.

4. Shri N. A. Palkhivala was appointed a Member of

‘the Commission on the Ist October 1956 in the Stgtute.

Revision Section, it having been decided to give priority to

the revision of the Indian Income-tax Act.

In December 1956, pne of the Members of the Comgnis-

sion Shri G, N. Das resigned his Membership of the 2 Gam

mission for reasons of health. His resignation deprit the

Commission of the mature experience of a senior ;and

eminent member of the Bar and later of the Bench. Itiwas

with considerable regret that the Chairman accepted his

resignation, It may be mentioned that the Commission is

greatly indebted to him for the assistance he gave to the

commission during the period of his association with it,

particularly on important topics relating to. the

reform of judicial adxginistration. .

5

After Shri G. N. Das resigned from the Commission

Shri P. Satyanarayana Rao who was till then prineipally

in charge of the Statute Revision Section of the Commis-

sion was invited by the Chairman to serve on the First

Section in addition to his onerous duties in the Second

Section and the invitation was accepted by him.

5. Although our appointment was in the first instance

mpto the 3st December, 1956, the period had to be extended

from time to time upto the 30th September, 1958 in view of

cthe large field of our inquiry.

6. In accordance with our instructions we have func-

tioned in two sections. The first section consisting of the

‘Chairman and the first three members has dealt mainly

‘with the question of the reform of judicial administration.

-At our inaugural meeting held on the 16th September, 1955

we discussed the objectives in our terms of reference and

the particular lines on which the Commission as a whole

and the two sections thereof should proceed; the initial

steps to be taken and the procedure to be followed, in so

far as the work of the first section was concerned. It was

decided (1) that the factual position with which the first

section had to deal should in the first instance be ascertained

before considering the remedial measures; (2) that detailed

information on these problems should be collected from all

possible suurces; (3) after the information had been

collected, a comprehensive questionnaire should be addres-

sed to all bodies and persons likely to assist the Commission

with their knowledge and experience, and (4) that the

vecommendations should be decided upon after the replies

to the questionnaire had beer examined. At the first meet-

‘ing of the first section held on the 17th September, 1955 we

‘discussed the several problems relating to the administra-

tion of justice on which reform was needed and preparéd a

‘list of the topics on which material had to be collected.

After the required information had been collected from

the State Governments, the High Courts and other sources,

a detailed questionnaire* containing 193 questions embrac-

ing almost all the aspects of judicial administration was

‘prepared at the second meeting of this section held on 6th

January, 1956 and was finally settled at a meeting of the

full Commission held on the 7th January. More than six

thousand copies of the questionnsire were distributed

samongst individuals and associations including the High

Courts, the State Governments, Bar Associations and other

organisations such as Chambers of Commerce, individual

‘lawyers and judicial officers, Although we received a fairly

large number of replies to the questionnaire we regret to

observe that the response was not as encouraging as we

had anticipated.

*See Appendix Ito the Report. i

6

Ata meeting held in Bombay on the 21st July, 1956, we

reviewed the progress of the work done by the first section

cf the Commission till that date with special reference

to the answers to the Questionnaire that had been

received. It was then decided thet in order to

obtain opinion and information on some of the important

problems which arose, it was necessary that the first section

of the Commission should visit the States and hold sittings

at the principal seat df the High Court in each State and

examine witnesses at these pleces. The conclusions reached

at this meeting of the first section were endorsed by the

Commission at its full meeting held on the next day.

The first section of the Commission met ai New Delhi

on the 18th, 19th and 2th of October, 1956 to further discuss:

the matters raised in the Questionnaire in the light of the

replies and information received and formulated certain

tentative idezs,. with a view to eliciting opinion on Shem at

the sittings of the Commission when on tour. These o

tive ideas were placed before a meeting of the full Commis-

sion held on the 20th of October, 1956.

. pee. exercise of the discration vested in the ha an

of Commission to co-opt one or two practising vers.

of a State in order to assist the Commission’s inqui in

that State, the Chairman co-opted two members in egch of

the States visited by us_except Madras where only one

member was co-opted, The names of the membefs co-

opted are given below:

‘Urrar Prapesit (ALLAHABAD)

(1) Shri Jagdish Swaroop, Advocate, Allahdbed.

(2) Shri Kirpa Narain, Advocate, Agra,

Kerana (ErwakuLaM)

(1) Shri KV. Sutyanarayana Iyer, Advpcate-

General of Kerala, rnakulam.

(2) Shri K, P. Abraham, Advocate, Ernakuldm.

Mysore (BANGALORE)

(1) Shri A, R, Somenatha Iyer, Advocate,

Bangalore, (now Judge Mysore High }

(2) Shri N. K. Dixit, Advocate, Dharwar.

‘Mlapnas (Mapas) *

(1) Shri § V. Gopalakrishnan, Advocate,

Tinnevelly.

“Shri V. K.T,, Chacisf member of the Scatute Revision Sectiog atcend=

‘Section’s a

ANDHRA PrabesH (Hyprranap)*

(1) Shri A. Ramaswamy Iyengar, Advocate,

Secunderabad.

(2) Shri M. S. Ramachandra Rao, Advocate,

Secunderabad.

West Benga (CaLeutra)t

(1) Shri S. M. Bose, Advocate-General, West

Bengal, Calcutta.

(2) Shri Atul Charidra Gupta, Advocate, Calcutta

Orissa (CUTTACK)

(1) Shri B. Jagannadha Rag, Advocate, Berhampur.

(2) Shri B. Mahapatra, Adyocate-General, Cuttack.

Assam i(GAUHATI)

(1) Shri Debeshwar' Sarma, Advocate, Jorhat.

(2) Shri S. K. Ghodh, Advocate, Gauhati.

Bomar (Bomar) +t

(1) Shri R. A. Jahagirdar, Advocate, Bombay.

(2) Shri V. R. Dholakia, Advocate, Ahmedabad.

RagasTHaN (JODHPUR)

(1) Shri C. L. Agarwal, Advocate, Jaipur.

(2) Shri Chand Mal Lodha, Advocate, Jodhpur.

Pounsas (CHANDIGARH)

(1) Shri A. N. Grover, Advocate, Chandigarh (now

Judge Punjab High Court),

(2) Shri G, D. Sehgal, Advocate, Jullundur.

é

Mapuya Prapes (JABaLPUR)

(1) Shri K. A. Chitale, Advocate, Indore, (Madhya

Pradesh).

**(2) Shri M. Adhilari, Advocate-General, Madhya

-Pradesh, Jabalppr.

— - men

*Shri D. Narasa Raju, a member{of the Statute Revision Section attend

ed the First Section’s sittings at Hyderabad.

}Dr. N.C. Sen Gupta, a meehber of the Starute Revision Section

attended the First Section’s sittings:at Calcutes,

Shri N. A. Palkhivala, a member of the Statute Revision Section attend-

ed the First Section’s sittings at Borybay,

**Waus unable to attend the sittihgs of the Conimission,

Butarn (Patwa)

(1) Shri Aghore Nath Banerjee, Advocate,

Monghyer (Bihar).

(2) Shri Lalnarayan Sinha, Advocate, Bihar High

Court, Patna.

&. Before commencing our tour we requested all the

High Courts and the State Governments to suggest the

names of witnesses of several categories, such as, (1)

judicial officers, (2) representatives of Bar Associations,

{3) representatives of the State Governments, (4) Heads

of the police departments, (5) Chairman of the Public

Service Commissions, (6) University teachers of law, (7)

Persons experienced in the working of Village Panchayat

Courts, (8) representatives of Legal Aid organisations and

(9) individual lawyers. The selection of the witnesses to

be examined in each State was made from the lists supplied

to us by the High Courts and the State Governments. Ia

addition, publicity in. the press was given to the visits of

the Commission to the headquarters of the High Courts,

so that, in addition to the witnesses proposed by the High

Courts and the State Govermments, we were also able to

obtain in each State the assistance of several other

witnesses who volunteered to piace before us their views

on the problems in which they were particulary interested.

9. In December 1956 the first section of the Commission

commenced its tours of the headquarters of all the State

High Courts for the purpose of recording evidence of

witnesses whose opinfon could be helpful in our task. We

examined in all 473 avitnesses whose names are gi in

Appendix 11. The sittings of the Commission and the

places visited are shown below: :

Sirings No. of

Place closed = Witnesses

Allshabat 31-12-1956 5

Emakuam s+ 11-1-1957 28

Banglore | 19-1-1957 35

Magms - 6 261-1957 35

Hyderabad + 3-2-1957 uM

Delhi : 24-2-1957 Jo

Calcutta foe 4-4-1987 eB

Cuteck 74-1987 14

so 1Eng-I987 7

Bombay © + 59-7-1987 37

Jodhpur 2-8-1957 at

wath 8-8-1957 32

Jaoatour 21-11-1957 30

tn. 29-11-1957 a6

“Witnesses from Himachal Predeshare emmmined et Chandigarh.

9

We generally held our sittings at the centres we

visited in public. Occasionally, jowever, it was found

necessary to take the evidence of some witnesses in camera.

The Commission had also the advantage of informal

discussions with all the Chief Justices and a certain

number of Judges of the High Courts on the various

. problems raised in the Questionnaire.

10, From the 2nd January to the 7th January, 1958 the

First Section again met in New Delhi in a series of meetings

in which conclusions were reached as to recommendations

to be made to Government. These conclusions and

recommendations were decided upon finally in the

combined meetings of both the Sections of the Commission

held in New Delhi on the 25th and 26th January, 1958.

11. A draft Report prepared in the light of the conclu-

sions was discussed at a meeting of the full Commission

in New Delhi on the 23rd August—and the Report as finally

settled and approved was signed at a meeting on the 26th

September, 1958.

12, We cannot conclude without expressing our warm

cand sincere thanks to the High Courts, the representatives

of State Governments and to the large number of indivi-

duals and associations who at the expense of much time and

‘labour sent us detailed and elaborate replies to the question-

“naire and submitted memoranda on various topics relating

‘to the administration of justice. We would also express

cour deep gratitude to the State High Courts and their

ministerial officers for the valuable co-operation and

assistance given to us during our visits to each State and to

the State Governments for the excellent arrangements

made by them for our accommodation and comfort and for

ithe staff which accompanied us.

First Law

Commis

tion,

2—HISTORICAL

The system cf administration of justice and laws as

we have today is the product of well thought out efforis

on the part of the British Government. No less than fopr

Law Commissions ‘were appointed during the last

century to augment the efforts of the Government in

settling its shape. Since then a number of committees

have been appointed from time to time to deal with

particular aspects so as tc mbdify the system to suit the

needs of the community. A brief review of the work of

the various commissions and committees is necessaryi both

to take stock of what has been done as also to evaluate

the task before us. t

The first Law Commission was constituted in‘ 1834

under the Charter Act of 1833, to investigate inté the

constitution of Courts and the nature of laws. In those

years there were being administered in the different parts.

of British India several systems of law “widely differing

from each other but co-existing and co-equal” and, yet,

singularly devoid of completeness, uniformity andj cer-

tainty. The origin of the important movement for legal re~

form and codification which began in 1833 may per be

traced to 2 correspondence which took place in or gout

1829 between Sir Charles Metcalfe and the Judges of

Bengal, in the course of which a scheme was conceived of

of administration of Justice which existed when the |East

India Company foi itself the territorial soverei,

the greater part of the country! In the debates

preceded the passing of the Act of 1833, Charles

the President of the Board of Control, called attenti

the three leading defects in the frame of the Indian C

tution. “The first was in the nature of Laws; the

was the ill-defined authority and power from which

various Laws and Regulations emanated; and the

was the anomalous and conflicting state of judicai by

which the Laws were administered’*, Macaulay |who

devoted a part of his speech upon the second reading, to.

the uncertainty of the laws and the need for codification

to ensure uniformity and certainty, said: j

“I believe that no country ever stood so mudh in

need of a Code of law as India, and I believe also that

there never was a country in which the want ntight

ue so easily supplied. Our principle is simply this,—

See Whitiey Stokes: The Anglo-Indian Codes, Volume 1, page %

‘Hansard, 1833 XVII, page 728,

‘10

laws to replace the re of conflicting laws and 5)

ll

uniformity when you can have it; diversity when you

must have it; but, in all cases, certainty”.! :

2. The First Indian Law Commission was composed of 1's person

T. B. Macaulay, the Law Member, as Chairman, and J. M. Sct,, 4

Macleod, G, W. Anderson and F. Millett—civil servants reference.

drawn from the presidencies of Calcutta, Madras and

Bombay as members, The Commission was to inquire into

the jurisdiction, powers and rules of the existing courts

of justice and police establishments and into the nature

and operation of all laws prevailing in any part of British

India; and to make reports’ thereon and to suggest altera-

tions, due regard being hatl to the distinction of castes,

differences of religion, arid the manners and opinions

prevailing among different races and in different parts of

the said territories. The Commissioners were to follow

such instructions as they should receive from the Governor-

General in Council.?

3. Macaulay expected tq finish the work on the Penal ork, of

Code and the Criminal Procedure Code in 1837 and to je com

enter on the work of framing a Code of Civil Procedure

in 1838." The task before the Commission was, however,

not as easy as Macaulay had envisaged. It was of a

stupendous and diversified character and required a great

deal of time and larger personnel. Moreover, the practice

of the Government of making too many references to the

Commission even on questions “which might have been

settled without any such r@ference” added to the Commis-

-sion’s difficulties and evoked sharp grotests from Macaulay.‘

it appears from an undated minute of Macaulay that in

order to speed up the work on the Penal Code, a fifth,

member was required!

4. After Macaulay’s departure Jate in 1837, the Com-;lts end.

mission shrank in size statunp partly on account of,

the absence of a successor.'of equal vitality and drive and:

partly because of extranepus circumstances. As Rankin:

points out in his ‘Backgrpund to, Indian Law’, notwith-

standing its strenuous la¥ours under Macaulay and his

successors, no results had teached'the statute book before

the mutiny." In the wortls of Fitzjames Stephen “The

Afghan disasters and triutnphs, the war in Central India,

the war with the Sikhs. Lord Dalhousie’s annexations,

threw law reform into the background and produced

state of mind net very favourable-4e it” It was felt tha‘

the Commission cost mord than it was worth and in 184

1Cited by Whitley Stokes : The Angl-Tadlan Codes, Vol. I, page &.

Act of 1833, 38. 53-35.

"Macaulay's Legislative Mibute of 6th June 1836. India Legislative

Consultations, 3rd April 357 Me 3 SCD) Diarkee? Lo Mateulere

minutes pp. 239-40.

“india Legislative Consultarlons, No, 3, 2nd Jan, 1837,

STbid,

"Page 21. \

"Cited in Rankin} + op. cit gh 21.

“Estimate

of its work,

bebe

12

its strength was reduced to one member and a secretary

in addition to the Law Member who acted as its president.

By January 1845 it had to forego its secretary as well,

5. In spite of difficulties in its way the first Commission

did remarkable pioneering work. It nad to work against

the background of the English system which had not then

been pruned of its manifold technicalities and the Indian

system, full of diversity and imcongruities. Without the

aid of a perfect model it had to evolve a consistent system

of Courts and laws from a conflicting and __ ill-defined

system of judicature on the one hand, and a bewildering

variety of ascertained. umascertained or unascertainable

rules of law of doubtful origin and vague application, on

the other hand. Its chief contributions were the draft

Penal Code of 1837, the draft law of Limitation and

Prescription of 1842, the scheme of pleading and procedure

with forms of eriminal indictments of 1848 and the Ler

Loci proposals of 1841. Besides these, the Commission also

reported on diverse subjects, eg., Judicial Establishmtents

of the Presidencies of Bengal, Madras and Bombay.

Special Appeals, Review of Judgments framed by Sadar

Courts, Report on Slavery, and Remuneration of officers

of the Courts of Judicature. It thus Jaid down the founda-

tions on which other legislators were to work.”

6. The next Charter Act” provided for the appointment

of the Second Law Commission to examine and consider

the recommendations of the First Indian Law Commission

and the enactments proposed by them for the reform of

the judicial establishments, judicial procedure and, the

laws of India and other matters. This Commission mwas

composed of Sir John Romilly, Sir John Jervis, Sir Edward

Ryan and Messrs, C. H. Cameron, J. M. Macleed, J. A. F.

Hawkins, T. F, Ellis and R. Lowe. The Commission was

directed to address itself in the first instance to the pro-

blem of amalgamation of the Supreme and Sadar Courts

of each of the presidencies and to devise a simple system

of pleading and practice, “uniform as far as possible

throughout the whole judrisdiction”

7. In its First Report the Commission submitted a plan

for the amalgamation of the Supreme Court at Fort

William with Sudder Dewanny and Nizamut Adawlat as

well as simple and uniform codes of Civil and Cri

Procedure, applicable to all the courts in the Presidegcy.

The Commission submitted plans and codes of pro re

on somewhat similar lines for th~ North Western Provinces

in their Third Report and for . edras and Bombay in

their Fourth Report. The Commission’s proposals for the

amalgamation of the Saddar Courts and the Supreme

Courts were given effect to by the Indian High Cotris

Act of 1861. In 1859, the Indian Legislature enacted the

\Cambridge History of Epi, Volume VI (1932) p, 8.

436 & 17 Vict ©. 95 Seey 28,

13

Code of Civil Procedure (VII of 1859) and the Limitation

Act (X of 1839). The Penal Code and the Code of Criminal

Procedure were passed respectively in 1860 end 1861, In

1862 a greater part of the Civil Procedure Code was

extended to the High Courts by Letters Patent.1 In their

Second Report the Commission examined ihe problems

of Lex Loci and codification and came to the conclusion Second |

that “what India wants is a body of substantive civil Report!

jaw, in preparing which the law of England should be

used as a basis, but which, once enacted, should itself be

the law of India on the subject it embraced. And such

a body of law, prepared as it ought to be with a constant

regard to the condition and institutions of India, and the

character, religions, and usages of the population, would,

we are convinced, be of great benefit to that country”?

The Commission also recommended that codification

should not extend to matters like the personal laws of the

Hindus and the Mohammedans which derived their

authority from their respective religions,

8, The Third and the Fourth Commissions were consti- The work

tuted respectively in 1861 and 1879. The Third Commission of the

was at the outset composed of Lord Romilly, Sir William [bird aed

Erle, Sir Edward Ryan, Robert Lowe (later Lord Ley Com-

Sherbrooke), Mr. Justice Willes and Mr. J. M. Macleod missions.

and sat in England." The Fourth Commission sat in

India and was composed of Mr. Whitley Stokes, Mr.

Justice Turner of Allahabad (later Sir Charles Turner,

Chief Justice of Madras) and Mr. Justice West of Bombay.

Those two Commissions were entrusted with the task of

codification of substantive law on the lines laid down by

the Second Law Commission in its Second Report. The

Third Commission submitted six draft Bills on Succession,

Contracts, Negotiable Instruments, Evidence, Transfer of

Property and Insurance besides making suggestions for

revision of the Criminal Procedure Code of 1861. Of these

drafts only the first became law in 1865. The Third

Commission felt dissatisfied with the apathy of the

Government of India in taking no action on their reports

and the acquiescence of the Home authorities in this.

attitude of the Government. They resigned in 1870 partly

for these reasons and partly as a result of a controversy

between the Secretary of State and the Commissioners on

the one hand and the Home and Indian authorities on the

other, as to certain proposals of the Commission in the

draft on the Law of Contract. The Fourth Commission

was directed to report on cettain Bills which had already

1The Civil Procedure Code of 1859 was was amended four times during the

next four years, Further amendments were made in 1877 and 1879 and the

original Code was revised and replaced by the Codes of 1882 and 1908, The

€riminal Procedure Code of 1861 was revised and replaced by the Codes

1872, 1882 and 1898,

*Second Report dated 13th December, 2855, page 8,

*Sic W. M. James L. tle 5 Mr. John

Henderson wicereddd Me, janice Wikies + and Mr: Tastee Lish mcedstea

Mr. Henderson.

! !

subsequent

inquiries,

Statute Law

Revision

‘Committee.

Civil Yus-

tice Com-

mittee,

14

been prepared for codifying the laws relating to Nego-

tiable Instruments, Transfer of Property, Easements and

certain other subjects and to make suggestions for future

codification of the remaining branches of the substantive

law of India. The Commissioners completed their work

in about ten months and submitted their report in 1879.

In accordance with their recommendations the Bill

relating to Negotiable Instruments was enacted in 1881

and the Bills relating to Trusts, Transfer of Property and

Easements ete. were enacted in 1882.

9. The system af laws and judicial organization

established in the Jast century on the basis of the earlier

Law Commissions’ recommendations has continued with

minor modifications down to the present day. The scope

and need for improvement particularly in the sphere of

judicial administration and procedural laws has been felt

throughout this Iong period but it was only in the years

following the first World War that systematic efforts ‘were

made in the direction of reform.

10. The earliest of these efforts was the creation df the

Statute Law Revision Committee of 1921 under the

chairmanship of the President of the Council of $tate,

This Committee was entrusted with the task of pre, ‘ing

for the consideration’ of the 'Government such meagures

of consolidation and clarification as might be nec y

to secure the highest attainable standards of formal

perfection in the statute law of the country. The Com-

mittee did some work in the sphere of consolidatiqn of

some branches of substantive law, e.g. Succession! and

Merchant Shipping. ‘With the retirement of its sdcond

President in 1932 the. Committee ceased to function.

11. In 1923, mai through the efforts of Sir] Tej

Bahadur Sapru, th Law ‘Member of the Vier "s,

Executive Council, a cbmmittee was appointed to deal Wwith

the problem of delay in civil eourts and the defects id-the

constitution of the dudiciary and the substantive! and

procedural laws of the country. This Committee with

Mr. Justice Rankin as, Chairman was “to enquire intd the

operation and effects a the substantive and adjective flaw,

whether enacted or erwise, followed by the courfs in

India in the disposal.jof civil suits, appeals, applications

for revision and other civi] Litigation (including! the

execution of decrees orderg), with a view to ascerfain-

ing and reporting ether any and what changes }and

improvements should be made so as to provide for; the

more speedy, economigal and gatisfactory despatch

business transacted in the courts and for the more 5] ly,

economical and satisfagtory execution of the process ishued

by the courts”. The Committee was expressly directed

not to inquire into the strength of judicial establishments

maintained in the Pa ek After a thorough and careful

inquiry into the varioug probleifas the Committee submitted

16

an exhaustive report in 1925. We shall have occasion ts

refer from time to time to its recommendations and the

extent to which they were implemented.

12, In the years preceding independence other Com- Committee

mittees were set up both by the Central and Provincial om special

Governments to inquire inte particular problems. Amongst ropice

the Central Committees must be mentioned the Indian

Bar Committee of 1923 to examine the conditions of the

Bar in India. The report of this Committee led to the

passing of the Indian Bar Councils Act of 1926. Earlier

in 1921 the States of Bengal, Bihar, Punjab and United

Provinces had appointed spegial committees to inquire into

the problem of the separation of the Judiciary from the

Executive. In Madras two gommittees were appointed for

the same purpose, the first in 1923 with Mr. Justice

Coleridge and the second in 1946 with Shri K. Rajah Aiyar

as Chairman.

The post-independence period witnessed a powerful

demand for a complete re-orientation of the legal and

judicial systems of the country. Not much, however, could

be done in the years immediately following 1947 on account

of the Central Government’s preogcupation with other

problems of a more pregsing nature. Mention must,

however, be made of the High Court Arrears Committee

of 1949 and the All India Bar Committee of 1951, The

High Court Arrears mittee, presided over by

Mr. Justice Sudhi Ranjan Das. was appointed to inquire

into and report on the advisability of curtailing the right

of appeal and revision, the extent and method of such

curtailment, and any other measures that might be adopted

to reduce arrears in the High Courts. In view of the

restricted character of its tegms of reference the Committee

contented itself by making @ few concrete proposals.

The All India Bar Comniittee was dppointed in Decem-

ber 1951 again under the chhirmanship of Mr. Justice Das.

Some of the problems referred to it were the desirability

and feasibility of a unified Bar for ‘India, the continuance

or abolition of different classes of legal practitioners, the ;

continuance or abolition of the dual system of counsel and

attorney, and the desirability of a sfhgle Bar Council. The

Committee recommended creation of a unified All India |

Bar and the continuance of the dual; system in the Bombay

and Caleutta High Courts. , In regard to its latter recom-

mendation two of its memiers expressed dissent. .

13. Meanwhile the States of West Bengal and Uttar

Pradesh appointed separatei committees in their respective

States to report on several problems relating to the Pradesh

administration of justice,}The West Bengal Committee fudicial ‘Re

appointed in 1949 under Sip Arthur Trevor Harries, then forms Com-

hief Justice of Calcutta,iwas asked to report on four"

specified matters—(a) ref in the system of administra-,

tion of justice in Calcutta, @) reforin in the administration:

i:

eat Bengal

Utar

Other

Commitces

of Enquiry.

Conclusion:

task before

the present

Law Com-

mission.

16

of justice in the rural areas, (c) reform of the legal

profession and (d) the question of State aid to indigent

litigants. The Committee submitted its report in 1981

recommending tnter alia the setting up of a City Civil and

Sessions Court and made several other recommendations.

The Uttar Pradesh Committee was set up in April 1950

with one of us, Mr. Justice K. N. Wanchoo, 2s Chairman

for considering the question of reform in the system of

administration of justice in that State with a view to

simplifying the process of law and making justice cheap

and expeditious. Its terms of reference were fairly

comprehensive. The Committee submitted its report in

1951 making a series of recommendations, some of which

required changes in the law for their implementation.

14. Amongst the other committees constituted in the

States to inquire into particular problems, special mention

may be made of the Separation Committee of 1947. in

Bombay under the chairmanship of Mr. Justice Lokur, and’

the Jury Committee of Bihar in 1950 with Mr. Justice

S. K. Das as its chairman.

15. As we have seen, the work of the four Law Com-

missions of the last century formed an integrated whole

and together they accomplished the task with which the

First Law Commission was entrusted but which. for

reasons already explained, it could not accomplish, ‘Their

work was directed towards the creation of a co-ordinated

system of Courts of law and a well-defined and as far as

possible a unified system of rules of aw. Their emphasis

all along was on Indian conditions and Indian needs

their endeavour, in the words of the Third Law Commisgion

was, to create a system which would be “alike honourdble

to the English Government and beneficial to the peqple

of India’. Their personne! -consisted of some of the

leading jurists of England. Their task was essentially of

a pioneering nature; it lay principally in delineating the

broad outlines of a system suited to Indian conditions, The

Subsequent inguiries into the diverse problems affecting

the legal and judicial systems in the present century were

all considerably restricted in seope and character.

In contrast, our task is more in the nature of improving

and reforming our presént structure of judicial administra-

tion in all its aspects of-revising and modifying the statute

Jaw. In fact, ours may well be described as the first

comprehensive inquiry into our legal system. We are thus

faced with a task of greater complexity and responsibility

than that which confronted our predecessors. Its cgm-

plexity is increased by the need for adjusting the machinery

of law and justice to the changed ideologies embodied in

our Constitution and our rapidly changing conditions.

3.—THE JUDICIAL SYSTEM

1, The powerful impact ,which the system of ‘Courts

cand judicial administration thas oh a vast number of

scitizens needs to be pointed ‘out, so that, it may be appre-

«ciated that the reform of the systefa is a matter of vital

importance, not only to the Jawyer and the judge but also

to the State and the avetege citizen, The smooth and

‘speedy operation of the Courts of law is essential to the

‘progress of the country anf the growth of its economic

and industrial stature. .

2. The vast volume of ordinary original civil litigation

in the country during any one year is shown in the

accompanying Table I whic relates to 1954. We refer to

it as ordinary civil litiga as opposed to disputes of a

Special kind, arising under‘ special enactments or deter-

mined by special courts. Im: terms of money, the value of

‘such ordinary litigation (exéluding tases which cannot be

valued in terms of money; of which there is a large

number) approaches the order of ome hundred crores of

rupees in a year. The number of suits instituted in the

civil courts exceeds ten less, and of these, nearly nine lacs

of cases involve disputes rating +> sums of rupees one

thousand and below. The r&ajority of these actions affect

persons to whom these sumb of one thousahd rupees and

less represent all or a majét part of their belongings. It

would therefore be wrong to regard them as petty litigation

not worthy of consideration. -

3. This Table does not tike into,

proceedings in appeal courtg, nor

proceedings befére special | trib

:several enactments. These special t4bunals function more

or less in the same =. as courts. They determine

disputes between citizen ari citize and between titizen

-and the State. Their decisidps affect the rights of patties.

In general, such tribunals accorded exclusive jutisdic-

tion in matters placed within their putviéw. Thefr decisions

-are final subject to appeals of revisitns wherever provided

and are also subject to the ‘writ juiisdiction of the High

Courts. A very large number of tizeris appear before

these tribunals in disputes determinable by them.

4. Rent Control Acts, Lahd Refit measures ahd the

like deal with disputes fable by special agencies

-cohstituted for that p and ¢ agéticies perforin

the functions which would have falith upon the

ordinary civil courts. No Mgures dite ‘available to bhow

the number of persons co! in these spetial typay of

Ww

“315 M of Law—2

BeaE

of Jaa

Seental”

Volame nd

Of citi

tion.

bI ies

tyburiats,

Number of

persons

before,

criminal

courts,

Number of

Persons:

before the

ordinary

courts.

Proceedings

to enforee

constitu-

tional

sights.

a8

litigation but having regard to the far-flung nature of

recent Jegislation, it is probable that the number exceeds

those concerned in ordinary civil litigation.

5. Table II gives an indication of the vast number of

persons brought before courts as aceused persons and

Witnesses every year. Complete figures of these are, how-

ever, not available. In addition to the immense number of

persons actually brought before the courts, an even larger

number is probably examined by the police or other depart-

mental agencies during the investigation of offences

6. The broad facts get out above do not, however, portray

a sufficiently clear picture of the impact of the volume of

civil litigation upon the citizen. Each action concerns at

Jeast two persons, a plaintiff and a defendant. In cases-

which go to trial, which are nearly half of the total num-

ber, a large number of persons appear on either side as

witnesses, After making allowance for different methods.

of disposal such as disposal ex-parte, disposal on admigsion,

disposal on a compromise and disposal without trial, a con-

servative estimate of the number of persons who have to:

attend courts in any one year as parties and witnesses in

the ordinary Civil Courts would be about twenty lacs. The

number in criminal cases would exceed cighty lacs. Jf we

further take into account the number of persons examined

by the police and persons concerned in appellate and other

proceedings (such as execution and insolvency) in the regu-

jar courts and special tribunals, the total may exceed two-

crores which amounts nearly to five per cent. of the: total’

population of the country.

7, In addition to the subordinate courts, where only,

generally speaking, original trials of causes take place, the

highest court in the State possesses special jurisdiction.

which has assumed great importance in the post-Corjstitu-

tion period. The upsurge of national consciousness which.

Jed to Independence has to a great extent altered, the

psychology of the citizen. The change of his status fiom:

a subject in a dependency to a citizen of a demorraiic

republic has reacted largely on the citizen's social, eco-

nomic and political kife. He is proudly conscious the

rights guaranleed to him by the Constitution; of hisjright

to social and economic justice; and of his claim to equa-

lity of status and opportunity. In the context of hig new

freedom, the citizen displays a keenness in the asstrtion

and protection of hig new born rights which one Would’

not have expected from him a decade ago. The attitude

of the citizen has been encouraged by the changed aspect

which the State has assumed What formerly was a sta-

tie machinery functioning largely for the purpase of

the preservation of law and order, has now changed into

a dynamic organisation ordeging the social and ecopomic

life of the citizen. e constant interference by! the

State with the everyfiay life of the citizen however well

intentioned and beneficial, comes into repeated conflict,

real or apparent, with the guaranteed freedoms and the

citizen is naturally not content till he has the matter

adjudicated upon by the courts. Thus, these recent changes

in our constitutional, social and economic structure bring

an increasing number of citizens to the courts.

8. It may also be observed that not all cases. civil or

criminal get disposed of at the first hearing. In practically

all civil suits disposed of after full trial, there are several

adjournments; on each of these dates of hearing, the parties

have in any case to appear in the courts. Witnesses also

have to appear in the courts on several occasions as_ the

courts do not always find time to record their evidence on

the days fixed. In the result, a fair proportion of the

lJarge number of the persons who attend courts have to do

so on more than one occasion,

9. What has been said above is enough to show the vital

importance of the proper functioning of the courts to the

country. In the social welfare State towards which we are

said to be moving, laws and tribunals which administer

them will have a constantly growing role to play. The

fanciful ideas of a few, who would abolish courts and law-

yers, are but an idle dream. Not only must courts continue

to exist, but they will have larger and an increasing num-

ber of functions to perform. A strenuous endeavour must

therefore be made to ensure the discharge of those functions

efficiently, and so as to cost the suitor and the witnesses,

the least expenditure of their time and resources.

Frequent

attendance

in Courts,

Importance

of judicial

reform,

Taste I

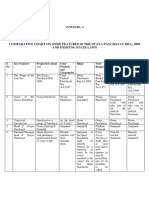

Comparative Statement showing the number and value of Civil Suits instituted in the year 19S4, in Courts of ordinary origtnal furisdiction

Not, Between Between

Between —_ Between.

Between Exceeding Incapable Total Total

Stare exceeding Rs. 10 Rs. 50 Rs, 00. Rs. soo Rs. 1000 Rs. 000 of valua- Number Value of 9 REMARKS

Rs. 10 and and and a and tion in of Suits Suits

Rs. so Rs. 100 Rs. 500 Rs. 1000 Rs, sooo money —Instinat

¢

It 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 oad Iz

Andbra . 4369 TL,74T 13,615 38,504 8,007 8,135 15725 305 86,4on 6,33,04,759 The figures

shown -agaimst

Asam : 318 2,288 1720 33722 994 gis 176. 19 10,205 -70;23,654 the Bombay

cate rt

‘fim .zg0ygsfop-—r7553 TBD 6 BJO FH Sa 133 badt73 om3e71t3 saciads. &

ay

‘Bombay . 2,128 130464 205753 38,135, 12,649, 11,649. 3,872 8,207 110,857 12,21520.000 value of sults:

inst in

Hyderabad. NAL NA NA NA NA NA. NA, NA. 1984 2r6j2ngor the High

‘Madhya Pradesh 619 5,076 5456 22,725 5:004 43100 pe 43,700 34 5:540979 aaercine of

Madras + 6,872 26,864 16313 35,165 Ta 6849 1,981 79 1,04;335 7,38,49,008 —_ juriadietion,

‘Mysore . 303 33,624 15,313 13,216 2,572 2,129 440 2,199 29,796 -1,37.49,031 The figuaes.

shown a

Orissa : 216 n712 2396 HOKE S37 Tag 338 48 14,376 1,68,89,222 the ,

of Mysore and

‘Travancorc-

Cochin roldte

to the: Official-

yetr 1994-55,

ppt G9 RE OOO GBI BEE He oe Ee BERL - Sahat oe et

Rajasthan. 374 4,413 6,413 225947 5219 Ewtcy 513 352 43,653 2994057,410

Saurashira . 508 30558

‘Travancore- = =§ ——-6,578————

Cochin

‘Unar Pradesh $5930 22,841

‘West Bengal . 35:627 73,065

31366237 1,663 15249 278 —1,843—18,266 1,25,06,346 Nore: ‘The

Table does

6,609 16,966 52408 4,169 206 239 40,175 2,80,18,649 not _give the

particulars

relating to

PEPSU_ and

23,802 69,607 «15.139 «1236 1,930 243 1550728 9,45,70,299 Part C States.

28,669 40,384 7879 8403 3459 2,467 15995953 19,$1,30,811

B1,7254+6578 BI9.17O 1,84,914 — 3554,465 82,965 70,688 18,026 16,278 10,24:293 83:73,36:467

‘Tape It

Statement showing the number of Criminal Casés, number of accused persons in those cases ahd the number of witnesses toho attended or were ekamined

in the Courts of various States in the year 1953

‘Total number Number of = Number of © Number of

Name of the State of cases accused witnesses who witnesses ‘REMARKS

brought to persons attended the = examined

trial Courts

I 2 3 4 5 6

Andhra. Fe 313,300 4:38.914 . 2.04439 “Does not include High

Courts and Sessions

Courts.

aoam 36,073 95.480 67,091

Bhopal © 2 ee 2,934 243643

Bibar oe se . 105,006 35245223, 3377726 3:30,842

Bombay. 6 1 ee ee 15577:782, 414,23,693,

Cog . ee ee 3:51

Himachal Pradesh 2. wee 5,080 95367

Hyderabad 6 ee ee 1,95.586 2,09,808 1,34)796 1,27,212

Ruch 2 we en 2,817 4,870

Monipot 6 ee 392

Madhya Bharat wee 54,113 1,14,812 991397 85,764

“Madhya Pradesh eee 1,34,163 299.355 1,69,122 1,61,540

Mads 6 ee ee 6,08,722 7:13,853 . 3575,870%

Mesore .

Orissa 4 .

Panjab, .

Ratasthan

Saurashtra ,

‘Travancore-Cochin

Utiar Pradesh .

Vindhya Pradesh

West Bengai

915335

. 515340

. 1,38,668

78,650

. 64,467

. 1448498

: 31575266

16,125

31573061

1,335597

202,378

24379555

1,00,655

2,60,767

7,63,616

$,08,124

65541478

3,04,069**

68,408

1,09,484

274364

7276

6,01,008

**Does not include wit

nesses examined by the

Magistrates under the

Municipal Act.

Nove:—Figures relating

f@ PEPSU are not avail

able,

Scope of

Enquiry.

Criticism

of existing

system of

adi

General

support for

existing

system.

Radical

changes not

necessary.

4—INDIGENOUS SYSTEM

1. The task assigned to us of suggesting ways and

for the improvement ‘of our present system of j

administration, does not preclude us from consideri

cal or revolutionary measures which may make it re

suitable to our needs. |

2. It is said in some quarters that the present syst of

administration of justice does not accord with the pattgrn of

our life and conditi We are told that large s Of

our population are illiterate and live in the villages. These

conditions demand, it is said “a system of judicial adzpinis-

tration suited to the genius of our country” or “an ingigen-

ous system”. Even the Uttar Pradesh Judicial Reforms

Committee of 1950-51 Btated, though by a majority thpt “it.

cannot be denied thati the rules of procedure and evidence

which they (the British) framed to regulate the proce

in court, were in some cases foreign to our genius aj

many cases were made a convenient handle to defeal

delay justice”?

3. In the circumstances, it became our duty to

opinion on these views. The answers we have

state with almost complete unanimity that the system

has prevailed in our country for nearly two centuries t

British in its origin Has grown and developed in

conditions and is now: firmly rooted in the Indian soi

would be disastrous ahd entirely destructive of our |

growth to think of a!radical change at this stage ol

development of our country. It has been pointed ou!

those who have supported a reversion to an indigenou:

1em of judicial administration have not really applied.

minds to the question. It would be ridiculous, it is

for the social welfare: State envisaged by our Constit

which itself is based largely on the Anglo-Saxon nx

think of remodelling its system of judicial administ1

on ancient practices, #dherence to which is totally

able to modern conditions and ways of life. We mi

well, it is said, think af rejecting modern medicine ai

gery and content ourtelves with what the ancients

and practised. :

4. Nevertheless, we must not fail to distinguish be’

the essential principleg of our present system and its

diary features like clumsy ai cumbrous procedurt

should not be forgotten as pointed out earlier that

charged with fashioniag our laws, have while regardit

English laws and institutions'as a model, conscioush

SReport, Page t

ry

2.

continuously gthempted to modify mould them to suit.

Indian life and Indiay conditions. at atterapt wes con—

tinued throughout the period of British rule with the subse-

quent association in an ever-increasing degree of Indiam

legislators, Indian Judges and Indian ‘administrators in the

making of laws and the administration of justice. If may

be that we have failed Ohen. laws and our court

systems and procedures conform, iently to the needs of ©

our people. To that extent, go doubt, they require modifica-

tion and adjustment. We have endeavoured to give atten-

tion to these points of view; but sueh changes can only be:

made within the framework of a system suited to our pre-

sent conditions and needs, which are the needs and condi-

tions of a highly organized welfare spciety with a developing

industrial economy. We haye, therefore, in considering the

changes which are necessaqy and practicable made a dis—

tinction between the fundamentals which must exist in any

modem system for the administration of justice and the:

procedures and practices by: which the system is to be ope-

tated. We agree with the observatiqns of the Uttar Prades:

Judicial Reforms Committee! that “the need of the hour is

that rules and procedures and evidence should be so simpli-

fied that justice may be available te the rich and the poor:

alike and that it may be pyompt and effective”. But sim-

plification cannot mean a gacrifice. of fundamentals andj

essentials. Perhaps, as poigted out:in a note of dissent to!

the report of the Committee, “the real need of the hour is!

the inculeation of a higher sense of duty, a greater regard!

for public convenience. greqter efficiency, in all those con-?

cerned in the administratioy of justite.”* In any case which-!

ever way our needs are looted at, little is to be gained by

an insistence on what has been callad an indigenous system

or a system suited tc the genius of our country.

5. However, we shall briefly endeavour to gather the

essentials of such an indigenous system as existed in our’

country prior to the advent bf the British and point cut that

the essentials of our ancient system were not very different/

from those of our present system.

[

at a stidy of the vast is very

ning fof the future. But it

jt a sysl of judicial adminis-i

wth its advance is mould-.

‘ions the existing social

frorg stage to stage its needsi

any system which governs the:

Ss comppnent parts would also!

ion. In considering the ancient!

system and contrasting it with the present judicial system,|

we must always keep in ngjnd the. ferences in the struc-|

wae anu conditions of sociely as it existed then and as it is?

today. L

It is undoubtedly true

desirable when we are pl

should not be forgotten

tration is a matter cf slow.

structure. As society adv:

alter from time to time

functioning of society or

call for progressive modific:

——

Report, Page 3.

*Report, Page 127.

‘The Hindu

System,

“The Mus-

im system.

26

It is not easy to discover the details of the system of

judicial administration which obtained in India prier to

the introduction of the present system by the British.. The

materials upon whieh we can rely are scarce and.

fragmentary.

6. It is clear that there were two systems one of which

may be designated the Hindu system! The outlines of the

system have to be gathered from various ancient buoks such

as the Smritis, Commentaries and Digests. These books

yield us valuable information but are by no means compre-

hensive; moreover they differ a great deal in regard to the

details. As these books relate to different periods, it is rot

possible to reconstruct a well-defined system with reference

to them. Many of its fundamental features can be derived

from them. In his book on the Hindu Judicial system,

‘Sir S. Varadachariar concludes that “whenever, and wher-

ever and so far as circumstances permitted, attempts were

all along being made in Hindu India to administer justice

broadly on the lines indicated in the law books”.

7. The second system may be styled the Muslim system

which was based upon the writings of the Muslim jurists

and practices of Islamie countries. This system was, how-

ever, never in exclusive use in our country. Most of the

Muslim rulers followed a policy of non-intervention in ¢ivil

matters and permitted the Hindu institutions to function.

However in cases whete the dispute arose between a Mus-

lim on the one hand and a Hindu on the other, or between

two Muslims, the Muslim tribunals claimed exclusive juris-

diction. In the sphere of administration of criminal justice,

the Muslim system prevailed subject to some exceptjons.

The system was not popular with the large mass of; the

people but was in vogue in large parts of the country at

the time of the introduction of the present system base cn

the British model. It 1s, we think, unnecessary to congider

the Muslim system in the present context.

8 The Hindu system as outlined in the law bpoks

reveals a gradual development. In its early beginnings it

was more or less a tribal institution the tribunal disperjsing

justice being the assembly of the village, the caste, ax the

family. These may be called the popular courts and they

seem to have been the earliest tribunals in the coustry.

They, in fact, were a part and parcel of the social structure.

T

3In portraying the Hindu Judicial System, we have dr:

the following ‘sources : me Sv awn largely from

® Berolzheimer : The World's Legal Philosophies,

ii) S. Varadachariar : Hindu Judicial System.

; ‘Thakur : Hindu Law of Evidence.

iv) By Sen: Hindu Jurispradence.

() K.P. Jaiswal ; Hindu Polity,

Sen Gupta : Sources of Law and Society in Aucient Iddia.

(wi) N

3 Sen Gupta ; Evolution of Ancient Indian Law.

«ii

*Page 258.

27

The territorial unit was the village which in those days

enjoyed a considerable measure of autonomy. There arose

and developed courts, if such a term could be applied to

them, of the family, the caste and the village. Though there

is no authority for the view that these popular tribunals

derived their powers from the king, such a view slowly

came to be held.

It is not possible to gather with any certainty the exact

scope of the functions of these tribunals. Colebrooke

asserts that they indicated merely a system of arbitration.

There is a suggestion in some texts that before resort could

be had to the Royal courts, local remedies had to be exhaust-

ed; but whether this was ever the correct position, it is diffi-

cult to say. Most of the later Hindu rulers and the Muslim

rulers were mainly interested in the collection of revenue

and the retention of the authority of these organisations

facilitated this task, Attempts were made for the integra-

tion of these popular courts with the Royal courts but they

did not succeed principally because of the decay of the

Hindu Royal power after the time of Harsha.

9. Though ancient writers have outlined a ‘hierarchy of Structure

courts as having existed in the remote past, the exact struc- of courts,

ture that obtained cannot be ascertained with any definite-

ness; but later works of writers like Narada, Brihaspathi

and others seem to suggest that regular courts must have

existed on a considerable scale, if the evolution of a complex

sysiem of procedural rules and of evidence can be any

Buide.

Popular tribunals, particularly the village courts surviv- p

ed for a long lime and existed even at the time of the com- tribunals,

mencement of the British rule in India, Their continuance

was favoured by their antiquity and the absence of zeny

other effective tribunals within easy reach; the structure

of the village society in those days; the nature of the prin-

cipal functions which these tribunals discharged which -

were conciliatory; and the non-interference by local rulers -

with the working of these tribunals.

In contrast to these popular tribunals, the Royal tribu-

nals were subject to frequent changes. Except for the fact

that ancient literature spealis of the: King as the source of

dharma and regards him as'charged with the duty of pro-

tecting dharma, there is nothing to show that the king per-

‘sonally was incharge of the administration of the law. He

administered law and justice generally through officers or

the sabhas appointed for the purpose. But though the

details of the working of these courts are not available, there

is evidence that a procedure of a specified kind was being Royals

folluwed im these Royal tribunals. Obviously, systematized "

rules were not called for in the popular or village courts;

but some sort of definite procedure seems to have obtained

in the Royal courts. It must not als- be forgotton that the

Pleadings.

E. idence.

‘Witnesses,

28

law enforced in those days was not, apart from specific

edicts, statute law but.was moral law. Tt was regardefl as a

sacred and religious duty to Vindicate the truth and uphold

the righteous and ish the wrong-doer. .

10. Under the andient precedure, every person had a

right of approach to the judivial tribunals. The court was

bound to hear him and take necessary action. There

appears to have been no court fee for the institution of the

sult, though there was provision for the payment of a

small percentage of tHe value of the claim by the successful

party. What may be.called the abuse of the right of suit

was checked by elaborate rulés insisting on an early fesort

to court or the taking of certain other active steps My the

arty. Litigation wag discouraged amongst persons ¢land-

Ing in particular relationships. Fines and penalties could

be imposed on persofs who ¢ame forward with false and

unfounded cases. On the criininal side, it was the dity of

the officers of the King to bi before the court pgrsons

accused of certain specified offences. '

L

11. Rules also provided that following a plaint there

should be a written ly by the defendant. A reference is

made also to a proce@ure for: clarification of the poists in

dispute analogous to the framing of issues. This wab fol-

lowed by the trial atiwhich evidence was recorded Hefore

the final stage of decigion by the court was reached.

The rules also provided for ex parte decisions ij

case of the non-appearance of the defendant.

could be amended at any time. before the defendant a)

ed and put in his answer. THe defendant had to mi his

answer in the prese of tha complainant and it was the

rule that the answer, should.‘méet the grounds rai: by

the plaintiff or the cdmplainant and should be clear! con-

sistent and free fron obscurjty. The answer could] take

the form of an admissjon, denial or special pleading orfeven.

a plea of a former judgment. : In the case of an admigsion,

a decree followed imnjediately; in other cases, evidencp had

to be led by the party on whom the burden of proof lay.

The expression of “‘htrden of proof” was understoo

practically the same gense as it is today. Thakur i;

Hindu Law of Evidertce refeys to the application of{such

important principles 4s the exclusion of oral by doc

tary evidence, the juirement that evidence shoul

direct and the exclugion of hearsay evidence in

courts. i

12. Witnesses were examimed by the court in the pre-

sence of the partigs. Provisions also existed the

summoning of witnestes or the ‘examination of witqesses

on commission. The texts lai down that the judge Id

treat the witnesses gently, tliat none should be ished

on mere suspicion that’ sive evidence of jgwilt

29

should be available before cqfviction, ‘There is aise a seg-

gestion that the judge himself could bndertake the exéthi-

nation of witmesses and that guch an ation could be

ofa thorough-going character; quite ppssibly this was so for

the reason that neither a polide inves! ting agency nor the

legal profession appears to have existed in those days.

There is, however, no suggestion that the Hindu system

corresponded to the inquisitorial protedure that at present

obtains on the continent,

13. It may be noticed that the rules also provided for

fhe impleading of the legal represetmtatives of a deceased

iy.

lig.

Repreventae

tives,

14, The decision of the it was pronounced imme- Judgement.

diately after the conclusion of the trial. Even in those days,

the difference in the conseatences of a judgment on the

merits after contest and a judigment passed ex parte seems

to have been recognized.

15. It is not quite clear from the ancient books whether Appeal

the decision of the Royal court was final or was subject apdRe-

to a review or appeal. In the case of the decisions of the ¥*-

popular courts, it seems likely that they could have been

taken in appeal to the Reyal courts. Sufficient indica-

tions, however, exist to shi that where a court gave a

decision in which the King (lid not personally participate,

the matter could subsequently be brought before him. In

certain cases, the matter cpuld be re-heard, possibly on

the basis of new evidence and a judgment could also be

set aside on the ground of ftaud.

We have attempted only ‘a brief turvey of the structure

and the features of the syatem as it existed in the past.

To go into greater detailiappears to us to be wholly

umnecessary.

16. Even this brief picture is sifficient to show how

‘unsound is the oft-repeated. assewtion that the present

system of administration of justice-ig alien to our genius.

Tt is true that in a literal.sense the present system may

be regarded as alien, It ia undowttedly a version of the

English system modified inj some ways to suit our condi-

tions. The English system|which tad developed through

the centuries was pruned 6f its torical anomalies and

technicalities and made laptablt to the conditions in

‘India. But it is easy to seq that im its essentials even the

ancient Hindu system commprised:these features which

every reasonably-minded 9 wollld acknowledge as the

vessenial features of any sy#tem of judicial administration,

whether British or other, We have already indica

that such features as the rules pleading, the manner

in which plaints were to be drawh, the devices to meet

ah abuse of the right of quit. the} miles of evidence, the

order in which litigation Hd piriteed, the exelitsion of

similarities

ith pre-

ent system.

Benefits of

popular

courts.

The posi-

tion to-

day,

30

oral by documentary evidence, the rule that evidence

should be direct, thé rule that hearsay evidence should