Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Cultura de La Pantalla

Cultura de La Pantalla

Uploaded by

ganvaqqqzz21Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Cultura de La Pantalla

Cultura de La Pantalla

Uploaded by

ganvaqqqzz21Copyright:

Available Formats

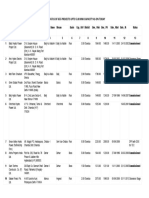

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/329885476

Cultura de la Pantalla network: writing new cinema histories across Latin

America and Europe

Article · January 2018

CITATIONS READS

3 65

3 authors:

Philippe Meers Daniel Biltereyst

University of Antwerp Ghent University

58 PUBLICATIONS 335 CITATIONS 177 PUBLICATIONS 687 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Jose Carlos Lozano

Texas A&M International University

118 PUBLICATIONS 526 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Cultura de la Pantalla View project

Screen(ing) Audiences View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Philippe Meers on 07 January 2019.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

PROYECTOS

Philippe Meers; Daniel Biltereyst; José Carlos Lozano

The Cultura de la Pantalla network: writing new

cinema histories across Latin America and Europe

· Philippe Meers, Daniel Biltereyst and José Carlos Lozano

University of Antwerp, Ghent University and Texas A&M International University

Part of the Cultura de la Pantalla team and guests at a workshop in Mexico City, September 2016

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Philippe Meers is Professor in Film and Media Studies at the University of Antwerp, Belgium, where

he is deputy director of the Visual and Digital Cultures Research Center (ViDi) and director of the

Center for Mexican Studies. He publishes on historical and contemporary film cultures and

audiences.

Contact: philippe.meers@uantwerpen.be

Daniel Biltereyst is Professor in Film and Media History and director of the Cinema and Media

Studies research center (CIMS) at Ghent University, Belgium. Besides exploring new approaches to

historical media and cinema cultures, he publishes regularly on film and screen culture as sites of

censorship, controversy, public debate and audience engagement.

Contact: daniel.biltereyst@ugent.be

José Carlos Lozano is Professor of Communication and Chair of the Psychology and Communication

Department at Texas A&M International University, Laredo, Texas, USA, and a Research Fellow at

158 © 2018. Revista Internacional de Comunicación y Desarrollo, 9, 158-165, ISSN e2386-3730

PROYECTOS

The Cultura de la Pantalla network: writing new cinema histories across Latin America and Europe

Tecnológico de Monterrey, Mexico. He has published widely on historical cinema cultures, mass

communication theories and international communication.

Contact: carlos.lozano@tamiu.edu

© 2018. Revista Internacional de Comunicación y Desarrollo, 9, 158-165, ISSN e2386-3730 159

PROYECTOS

Philippe Meers; Daniel Biltereyst; José Carlos Lozano

for Monterrey, Lozano started with a new study

1. THE NETWORK in Laredo, Texas, thereby including the US within

Cultura de la Pantalla. And recently two new Me-

xican teams joined the group, León in 2017 and

The Cultura de la Pantalla (CdP) network con-

Saltillo in 20182.

sists of an international group of film, media and

communication researchers in Latin America

(Mexico and Colombia) and Europe (Belgium and

Spain) collaborating in a series of multi-method

longitudinal studies on urban cinema cultures in

the Spanish language world. Together we are

writing ‘new cinema histories’ (Maltby, 2006)

across Latin America and Europe with a focus on

exhibition, programming and audience experien-

ces. The network connects directly with wider

dynamics in the field of cinema history, under

the header of ‘new cinema history’ (see: the Cinema City Cultures: screen shot opening page

conceptual framework). In practice, the teams

carry out multidimensional replica studies in

their respective cities, with quasi-identical cen-

tral research questions, research design and

methods. The network developed out of a re-

search project The Enlightened City on the his-

tory of Belgian cinema culture and more spe-

cifically the interaction between exhibition, pro-

gramming and audience experiences1. This pro-

ject built the research design that was later

replicated by the teams within the network,

under coordination of the three initiators, Daniel

Biltereyst, José Carlos Lozano and Philippe

Meers. Cinema City Cultures: screen shot map projects in

Mexico and Colombia

The story goes back to 2008, when Lozano,

after listening to a conference presentation on

the Enlightened City project, contacted Biltereyst

Cultura de la Pantalla is an example of a

and Meers with the proposal to do a replica

bottom-up quite informal international research

study of the Belgian project for the Northern

collaboration with little extra funding3. Each

Mexican city of Monterrey. Both immediately

team provided its own means for research, often

agreed and the replica in Monterrey started in

working with bachelors and masters students,

2009. The research design, central questions

involving them in an original research project

and all research instruments were shared and

and allowing them to discover parts of their own

translated to Spanish. With the help of collea-

city’s cinema history.

gues from other universities in Monterrey, and a

large team of junior and senior students within The network also plays a prominent role in

the framework of the research chair that Lozano Cinema City Cultures, as one of the key aims of

held at the TEC, the project was executed the Cinema City Cultures network is precisely to

successfully. And with the Monterrey study still foster more work on the history of urban

ongoing, we organized a workshop in 2012 for cinematic cultures. The wider context for both

interested colleagues at TEC Monterrey, ex- Cultura de la Pantalla and Cinema City Cultures

plaining the general set-up and the aims of the has always been HoMER, the History of

project, with the invitation to join. And rather to Moviegoing, Exhibition and Reception network, a

our surprise, what started out as a single city diverse international group of film researchers

replica study for Monterrey, developed into a forming a driving force behind the renewal of

network of teams across Mexico and other contemporary cinema research, now known as

Spanish language countries. As an outcome of ‘new cinema history’. This approach has directly

the workshop new replica studies were initiated inspired Cultura de la Pantalla.

in several Mexican cities: Mexico City, Torreón,

Tampico; in Spain: Barcelona, and in Colombia:

Cartagena de Indias. After finishing the project

160 © 2018. Revista Internacional de Comunicación y Desarrollo, 9, 158-165, ISSN e2386-3730

PROYECTOS

The Cultura de la Pantalla network: writing new cinema histories across Latin America and Europe

2. THE CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK: NEW 3. THE MODEL

CINEMA HISTORY

The aim of the CdP projects is to develop a

Over the past fifteen years, film and cinema series of multi-method longitudinal studies on ci-

studies developed from a largely text and film nema culture in cities of the Spanish language

centered approach into a more cultural- and world. This entails a diachronical analysis of 1.

socio-historical approach to cinema. The theo- cinema locations and institutional structures, 2.

retical and empirical work of scholars like Allen cinema programming and 3. ethnographic oral

(1990, 2006) and Staiger (1992), among others, history audience research on cinema-going. The

have established the grounds for an approach ultimate goal of the network is the comparison of

looking both at film exhibition and programming these individual replica projects with each other

and at the lived experiences of film audiences and with the findings of the original project in

and the social experience of cinema-going (Mal- Belgium. This central aim is operationalised in

tby, Biltereyst and Meers, 2011; Biltereyst, three research parts, each formulating a specific

Maltby and Meers, 2012, 2019). This shift in hypothesis and resulting in a separate database,

focus coincided with what Richard Maltby (2007) with large amounts of data to be compared

indicated as the terminological and method- between all cases.

logical distinction between film history and cine-

In a first part ‘Mapping cinemas: geographi-

ma history, or ‘the difference between an aes-

cal location and institutional structures’ an insti-

thetic history of textual relations between indi-

tutional analysis is executed of cinemas and

viduals or individual objects, and the social his-

sites of film distribution in an urban context. The

tory of a cultural institution.’

hypothesis here is that cinemas have occupied

In its assessment of the wider historical central spaces in the urban fabric of provincial

conditions of the cinematic experience, this new and metropolitan cities, developing a symbolic,

cinema history involves the usage of several dis- cultural, economic and social hierarchy ranging

ciplinary approaches, coming from history, cultu- from high end picture palaces to low esteemed

ral geography, demography, ethnography, etc. neighborhood cinemas. Specific research ques-

The approach brought forward clear-cut empiri- tions then are e.g.: How are sites for film exhi-

cal methodologies from the social sciences to a bition and distribution situated in an urban con-

field hitherto dominated by theoretical, humaniti- text? How do cinemas and other sites of film ex-

es- or text-oriented approaches. This new trans- hibition interact with the cultural and social net-

disciplinary and multi-methodological approach, works of a city? This part results in a database

equally embraces an openness towards digi- containing an extended historical inventory of

tization at various levels, including data collec- the film exhibition structure, including the socio-

tion, processing and analysis (e.g. construction geographical distribution of cinema houses, their

of large-scale databases on historical film ex- characteristics and types of movies shown.

hibition sites, programming, distribution, cen-

The second part ‘Film programming trends’

sorship data; use of computational tools for ana-

starts from the hypothesis that film programming

lysis and presentation like GIS), as well as in

in Latin America and Europe was historically for

terms of data valorization, e.g. building open-

a large part dominated by American film, except

access platforms for other researchers and the

for specific areas (art house cinemas) and or

wider audience.

specific periods (e.g. the Golden Age of Mexican

cinema). Central questions then are: What are

the key data on programming, box office and

organization of film exhibition? Classical archival

research is hereby combined with interviews with

key players of the local cinema scene. For sam-

ple years per decade (1932, 1942, 1952, up to

2012) the film programs are inventoried and

analyzed. This second part results in a large da-

tabase containing a detailed description of the

movies exhibited during the sample years (type

of movies shown, their number of screenings,

HoMER website: screen shot opening page country of origin, etc.) through the analysis of

programming schedules of local movie houses

included in local daily newspapers.

© 2018. Revista Internacional de Comunicación y Desarrollo, 9, 158-165, ISSN e2386-3730 161

PROYECTOS

Philippe Meers; Daniel Biltereyst; José Carlos Lozano

The third part ‘Audience and film experien- different from the majority of the American

ces’ shifts the attention from structures, location market. Using a triangulation of methods invol-

and programming to consumption and experien- ving a mapping of cinemas, an extensive data-

ce of film culture, whereby the central hypothesis base of films exhibited and oral histories on

is that cinema-going is a social event, highly cinemagoing, Lozano reconstructs the strategies

conditioned by contextual factors. This allows for of the Robb and Rowley company, a regional

the construction of a typology of viewers. Diffe- chain that controlled exhibition in the Laredo

rent types are interviewed in a qualitative set-up latino market over a period of more than fifty

and in depth interviews are executed with a years. The large exhibition circuit adapted its

substantial number of respondents (according to programming strategies to a particular local mar-

age, gender, etc). Research questions are: What ket: Lozano reveals the striking absence of any

are the meanings of film consumption and of policy segregating Mexicans or Mexican-Ameri-

sites of film exhibition and distribution? How cans in the chain’s cinemas, despite this being

does the discursive construction of the cinema common practice in many Texan and U.S. cities

as space develop historically in interaction with in the first half of the twentieth century.

the cultural and social networks in the city? The

database for part 3 contains the transcribed and

coded interviews. The final phase of the project

then consists in combining the three levels of

analysis to achieve a nuanced, complex multi-

layered view on the landscape of cinema culture

for each city and later, over the different cities,

regions, countries.

4. CASE STUDIES

Most teams that are currently in advanced

stages of the research have published on their

results (Lozano, Biltereyst, Frankenberg, Meers

& Hinojosa, 2012; Lozano, Biltereyst & Meers,

2017; Repoll, Portillo & Meers, 2014; Chajin &

Miranda, 2015; Chong, Ornelas, Solís & Flores,

2016; Luzón & García Fleitas, 2016; Nieto

Malpica, Tello Iturbe, Rosas Rodríguez &

Biltereyst, 2016, for full list of publications see

www.cinemacitycultures.com). Looking at these

case studies we find a fascinating mix on all

Map of Laredo, Texas with cinemas 1930s-1940s

three central dimensions – exhibition, pro-

gramming and audiences- of particularities due

to the geographical, cultural, socio-economic si-

tuation of the city studied, while other findings On the level of cinema memory, this excep-

clearly transcend the specific context of each tional case offers equally fascinating findings.

case and align to more international patterns, Exploring the memories of Laredo filmgoers bet-

such as the importance of the movies and ween the ages of 64 and 95 on US and Mexican

cinema-going in everyday life, the social expe- films we get a nuanced picture of the role of film

rience of cinema-going etc,. We illustrate briefly stars and local venues in cinema-going, against

with the peculiar case of Laredo, Texas (USA). the historical background of a fluid and complex

border. In particular, Lozano (2017) demons-

In Laredo, a border town with a predomi- trates how residents with strong connections to

nantly Spanish-speaking or bilingual Mexican- Mexican heritage negotiate their cultural iden-

American population, the cultural-geographical tities, but are also influenced by the structural

location plays a crucial role in the historical characteristics of the American political, econo-

development of cinema culture (Lozano, 2019). mic and educational systems.

Laredo provides evidence of the flexibility of

cinema exhibition and programming in a cultural,

linguistic and geographic context significantly

162 © 2018. Revista Internacional de Comunicación y Desarrollo, 9, 158-165, ISSN e2386-3730

PROYECTOS

The Cultura de la Pantalla network: writing new cinema histories across Latin America and Europe

5. COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVES sources and research conditions. In the case of

Monterrey, terraza screenings for lower social

Much of the work done so far in new cinema classes were mostly not listed in newspapers or

history is focused on very specific local practices trade journals, and could only be discovered via

of historical cinema culture and concentrates on oral histories.

film exhibition and audience experiences in parti- These issues are a major challenge for the

cular cities, neighborhoods or venues. Com- network to focus even more on the comparative

parison has, however, been on the agenda of aspects of the research: both regional (Northern

new cinema history for a few years now, as com- Mexico), national (Mexico), American (Mexico,

parison is helpful in trying to understand larger Colombia and the US), European (Belgium and

trends, factors or conditions explaining differen- Spain) and cross-continental (Mexico, Colombia,

ces and similarities in historical cinema cultures. Spain and Belgium) comparisons are on the

Especially for Latin America, where empirical agenda.

studies on cinema culture are rather scarce, the

need for large scale comparative work is urgent.

Testing hypotheses on e.g. Americanization, US

influence and the hybridization of media and the 6. FUTURE HISTORIES

collective imaginary benefit from this intercom-

tinental comparison. It can also link up with The various teams are currently working on

wider theoretical debates, both in Latin America the case studies each in their own time frame.

(e.g. Garcia-Canclini, 1990) and Europe on these Many journal articles and book chapters on

issues. individual cases have been published (see

As the CdP network covers various projects reference list), others, both on cases and on the

within Mexico, it offers possibilities for intrana- comparative dimensions are in press or in prepa-

tional (intercity and interregional) comparison as ration (e.g. Lozano, 2019). Meanwhile, resear-

well as international and intercontinental com- chers can also engage in fruitful conversations

parison. And the Belgian project, as one of the with similar work published on Mexico (e.g.

pioneering large scale empirical projects of this Rosas Mantecon, 2017) and other countries

kind, is very well placed for providing the compa- such as Brazil (Ferraz, 2017).

rative material, also for the Southern European In the long term, the aim is to join all

findings of the Barcelona case study. databases of each case study together in one

Projects that try to compare mostly stumble central sustainable data depository and subse-

onto problems of comparing variables and me- quently open them up to both the academic

thods. As our projects all work with an identical community and the wider public via a digital

methodological set-up and toolkit, resulting in platform. Inspiration for this endeavor can be

identical and fully compatible databases, compa- found in CINECOS, a research infrastructure pro-

rison should be facilitated. But even here we are ject developing a ‘cinema ecosystem’ that con-

confronted with problems such as interrogating sists of an open access platform for sharing,

some of the seemingly obvious temporal and enriching, analyzing and sustaining databases

spatial dimensions (Biltereyst & Meers, 2016). In on film history in Belgium4. In a later phase and

a Western European context for instance, a film with the necessary funds, this platform might

venue mostly is a fixed building with bricks, become a model to accommodate the CdP data-

stones and a roof, while mobile cinema became bases. Expanding the network to other South-

rather quickly a marginal phenomenon, and film American countries is another ambition for the

programmes are announced in mainstream near future. New teams from Spanish speaking

newspapers. In a city like Monterrey, Mexico, countries are most welcome to join in. And as

night-time mobile and open air screenings, like the network grows, new cinema histories of

those referred to as terrazas, were a widely de- cities, countries and regions in Latin America

veloped phenomenon in the neigbourhoods, and Europe are in the making, helping to re-

underlining the importance of often overlooked construct the fascinating, complex and highly

conditions like weather or climate, next to issues diverse stories of historical cinema cultures in

of class as the terraza cinema experience was the Spanish language world.

mostly reserved to lower-class audiences. These

various conditions in terms of class, climate-

logical, material and spatial dimensions not only

emphasize the fluidity of the cinema concept,

they also influence the availability and use of

© 2018. Revista Internacional de Comunicación y Desarrollo, 9, 158-165, ISSN e2386-3730 163

PROYECTOS

Philippe Meers; Daniel Biltereyst; José Carlos Lozano

NOTES BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

1The research Project The ‘Enlightened’ City: Screen culture Allen, R. C. (1990). From Exhibition to Reception,

between ideology, economics and experience. A study on the Reflections on the Audience in Film History. Screen,

social role of film exhibition and film consumption in

Flanders (1895-2004) in interaction with modernity and

31 (4), 347-356.

urbanisation was funded by the Research Foundation- Allen, R. C. (2006). Relocating American Film

Flanders, (FWO 2005-8). Promoters were Philippe Meers,

Daniel Biltereyst and Marnix Beyen.

History. Cultural Studies, 20 (1): 44-88.

2The teams in the CdP network and their local coordinators Biltereyst, D., Maltby, R. & Meers, Ph. (eds.) (2012).

are: Cinema, Audiences and Modernity. London:

Routledge.

USA |Laredo, Texas: José Carlos Lozano (TAMIU/ITESM).

Mexico|Monterrey: José Carlos Lozano (TAMIU/ITESM),

Biltereyst, D. & Meers, Ph. (2016). New Cinema

Lorena Frankenberg (Universidad Metropolitana de History and the Comparative Mode: Reflections on

Monterrey), Lucila Hinojosa (Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo Comparing Historical Cinema Cultures, Alphaville:

León). Ciudad de México: Maricela Portillo Sánchez Journal of Film and Media Studies, special issue:

(Universidad Iberoamericana); Vicente Castellanos Cerda Cinema Heritage in Europe, 11, 13-32. Retrieved

(Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Unidad Cuajimalpa); from:

Jerónimo Repoll (Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana,

http://www.alphavillejournal.com/Issue11/Articl

Unidad Xochimilco). Tampico and Veracruz: Jorge Nieto

Malpica (Universidad Autónoma de Tamaulipas). Torreón: eBiltereystandMeers.pdf.

Blanca Chong (Universidad Autónoma de Coahuila, Torreón).

Biltereyst, D. Maltby, R. & Meers, Ph. (Eds.) (2019,

León: Efraín Delgado Rivera and Jaime Miguel González-

Chávez (Universidad De La Salle, Bajío). Saltillo: Brenda in press). Routledge Companion to New Cinema

Azucena and Antonio Corona (Universidad Autónoma de History. London: Routledge.

Coahuila, Saltillo)

Chajin O. & Miranda W. (2015). Memoria del

Colombia |Cartagena de Indias: Maricela Portillo Sánchez consumo de cine en Cartagena de Indias, 1962-

(Universidad Iberoamericana), Waydi Miranda Perez 1982. Informe. Beca Ministerio de Cultura.

(Universidad Iberoamericana, México / Fundación

Universitaria Colombo Internacional) and Osiris Chajin Chong, B., Ornelas, J., Solís, J. & Flores, J. (2016). Las

(Fundación Universitaria Colombo Internacional, Colombia / audiencias de cine en Torreón, Coahuila, México,

Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina).

durante las décadas 1940-1960. Global Media

Spain |Barcelona: Virginia Luzón and Quim Puig (Universitat Journal México, 25 (13), 140-158. Retrieved from:

Autònoma de Barcelona). http://www.cinemacitycultures.com/documents/a

Belgium |Antwerp and Ghent: Daniel Biltereyst (Ghent rt_chong_torreon.pdf .

University) and Philippe Meers (University of Antwerp). Ferraz, T. (2017). Reapertura de salas de cine,

3 The single overall funding for the network was a grant for memoria del cinema-going y gestión del

bilateral cooperation between the Mexican CONACyT and the patrimonio cultural: una comparación entre Brasil

Belgian Research Foundation – Flanders (FWO), 2014-2017 e Bélgica. Global Media Journal México, 14 (26), 24-

for ‘Cinema cultures in context. An international comparative 43. Retrieved from:

study on cinema spaces, film programming and cinema-going

experiences in Belgium and Mexico’, which allowed the http://journals.tdl.org/gmjei/index.php/GMJ_EI/a

network to organise various international workshops, both in rticle/view/255.

Belgium and in Mexico.

Garcia-Canclini, N. (1990). Culturas híbridas:

4 CINECOS (Cinema Ecosystem) is a research infrastructure Estrategias para entrar y salir de la modernidad,

project lead by Daniel Biltereyst with a.o. Philippe Meers, Grijalbo, México.

funded by the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO, 2018-

2021). It aims at developing an open access platform for Lozano, J.C. (2017). Film at the border. Memories

sharing, enriching, analyzing and sustaining data on film of cinema going in Laredo, Texas, 1930s-1960s.

history in Belgium from the 1890s onwards. Integrating 17 Memory Studies, 10 (1), 35-48.

existing research datasets covering key aspects of Belgian

film history such as production, distribution, exhibition, Lozano, J.C. (2019 in press). Cinema structure,

programming, censorship and reception, the platform aims exhibition and programing in liminal, multicultural

to improve the understanding and further exploration of

cinema as a dominant public entertainment industry and as

spaces: The case of Laredo, Texas, a predominantly

lived popular culture. CINECOS will provide a robust platform Mexican-American city on the U.S. border with

for managing and sustaining this unique dataset, facilitating Mexico. In D. Biltereyst, R. Maltby, & Ph. Meers

(inter)national data exchange and comparative research (Eds.), Routledge Companion to New Cinema

facilitate data driven exploration and analysis using data History. London: Routledge.

visualisation, mapping, text-mining and other digital tools.

Lozano, J.C., Biltereyst, D., Frankenberg, L., Meers,

P. & Hinojosa, L. (2012). Exhibición y

programación cinematográfica de 1922 a 1962 en

Monterrey, México: un estudio de caso desde la

perspectiva de la "Nueva historia del cine". Global

Media Journal Edición México, 9 (18), 73-94.

164 © 2018. Revista Internacional de Comunicación y Desarrollo, 9, 158-165, ISSN e2386-3730

PROYECTOS

The Cultura de la Pantalla network: writing new cinema histories across Latin America and Europe

Retrieved from:

http://www.cinemacitycultures.com/documents/a

rt-2013-lozano-biltereyst-et-al.pdf

Lozano, J.C., Biltereyst, D. & Meers, Ph. (2017).

Naïve and sophisticated long-term readings of

foreign and national films viewed in a Mexican

Northern town during the 1930-60s. Studies in

Spanish & Latin American Cinemas, 14 (3), 277-

296.

Luzón, V. & García Fleitas, E. (2016). Cinemagoing

en Barcelona: una proyección al futuro mediante la

experiencia de consumo de los espectadores

jóvenes, Global Media Journal México, 13 (25): 63-

95. Retrieved from:

https://journals.tdl.org/gmjei/index.php/GMJ_EI/

article/view/264

Maltby, R. (2006). On the Prospect of Writing

Cinema History from Below. Tijdschrift voor

Mediageschiedenis 9 (2), 74-96.

Maltby, R. (2007). How Can Cinema History Matter

More? Screening the Past, 22. Retrieved from:

http://tlweb.latrobe.edu.au/humanities/screening

thepast/22/board-richard-maltby.html

Maltby, R., Biltereyst, D. & Meers, Ph. (eds.) (2011).

Explorations in New Cinema History: Approaches

and Case Studies. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell.

Nieto Malpica, J., Tello Iturbe, A., Rosas Rodríguez,

M. E. & Biltereyst, D. (2016). El cine en Tampico y

Ciudad Madero: exhibición, programación y

contexto histórico-social en 1942. Global Media

Journal Mexico, 25 (13), 159-170. Retrieved from:

http://www.cinemacitycultures.com/documents/a

rt_nieto_et_al.pdf

Repoll, J., Portillo, M. & Meers, P. (2014). ¿Qué

hubiera sido de mi vida sin el cine?. La experiencia

cinematográfica en la Ciudad de México.

Contratexto, 22, 213-228. Retrieved from:

http://repositorio.ulima.edu.pe/xmlui/handle/uli

ma/1838

Rosas Mantecón, A. (2017). Ir al cine: antropología

de los públicos, la ciudad y las pantallas, CDMX:

Gedisa Editorial/UAM Iztapalapa.

Staiger, J. (1992). Interpreting Films. Studies in the

Historical Reception of American Cinema.

Princeton University Press: Princeton.

© 2018. Revista Internacional de Comunicación y Desarrollo, 9, 158-165, ISSN e2386-3730 165

View publication stats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5820)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Design of Brushless Permanent Magnet Machines-1Document2 pagesDesign of Brushless Permanent Magnet Machines-1harshalvikas50% (2)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- GCB - Hec 3-6.emergancy Spare Parts and Comp.V1Document18 pagesGCB - Hec 3-6.emergancy Spare Parts and Comp.V1Fabyano BrittoNo ratings yet

- Undergraduate Faculty Brochure: Make Today MatterDocument20 pagesUndergraduate Faculty Brochure: Make Today Matterganvaqqqzz21No ratings yet

- List/Status of 655 Projects Upto 5.00 MW Capacity As On TodayDocument45 pagesList/Status of 655 Projects Upto 5.00 MW Capacity As On Todayganvaqqqzz21No ratings yet

- Border News Media Coverage of Violence, Organized Crime, and The War On Drugs, and A Culture of LawfulnessDocument3 pagesBorder News Media Coverage of Violence, Organized Crime, and The War On Drugs, and A Culture of Lawfulnessganvaqqqzz21No ratings yet

- Foldery Koji Shima (1) : HawkmenbluesDocument1 pageFoldery Koji Shima (1) : Hawkmenbluesganvaqqqzz21No ratings yet

- Theoretical Approaches and Methodological Strategies in Latin American Empirical Research On Television Audiences: 1992-2007Document30 pagesTheoretical Approaches and Methodological Strategies in Latin American Empirical Research On Television Audiences: 1992-2007ganvaqqqzz21No ratings yet

- Consumption of US Television and Films in Northeastern MexicoDocument23 pagesConsumption of US Television and Films in Northeastern Mexicoganvaqqqzz21No ratings yet

- Public Policies and Research On Cultural Diversity and Television in MexicoDocument16 pagesPublic Policies and Research On Cultural Diversity and Television in Mexicoganvaqqqzz21No ratings yet

- Transcinema: The Purpose, Uniqueness, and Future of Cinema: January 2013Document10 pagesTranscinema: The Purpose, Uniqueness, and Future of Cinema: January 2013ganvaqqqzz21No ratings yet

- Nabokovs Time Doubling From The Gift To PDFDocument41 pagesNabokovs Time Doubling From The Gift To PDFganvaqqqzz21No ratings yet

- Ramdump Wcss Msa0 2023-12-24 18-17-34 PropsDocument14 pagesRamdump Wcss Msa0 2023-12-24 18-17-34 Propschaimaefadil3No ratings yet

- Cover Page - AiDocument266 pagesCover Page - Aijana kNo ratings yet

- Rudder Angle IndicatorsDocument5 pagesRudder Angle IndicatorsFabián Inostroza RomeroNo ratings yet

- Project PumpDocument4 pagesProject PumpPrajwal WakhareNo ratings yet

- 3TN84L RBS-B37 1Document49 pages3TN84L RBS-B37 1sasaNo ratings yet

- Case Study Sprint 4 All Solutions With 100 PointsDocument48 pagesCase Study Sprint 4 All Solutions With 100 PointsAshok Kumar80% (5)

- Student LAB 1 2019Document14 pagesStudent LAB 1 2019ANIME GODNo ratings yet

- Basug BasicTasksDocument640 pagesBasug BasicTasksdebendra128nitr100% (1)

- Internal To WiproDocument17 pagesInternal To WiproVIMAL KUMAR CHAUHANNo ratings yet

- Manual - Fonendoscopio Lightweight IIDocument6 pagesManual - Fonendoscopio Lightweight IIsantiagoNo ratings yet

- Iolan+ Rack 8 Serial Server User GuideDocument230 pagesIolan+ Rack 8 Serial Server User GuideapraksimNo ratings yet

- WIL - Wiley Teaching and Learning Technology CatalogueDocument28 pagesWIL - Wiley Teaching and Learning Technology CatalogueGoldenNo ratings yet

- P14x CortecDocument4 pagesP14x CorteczerferuzNo ratings yet

- Elbow 0,75-6000 SW 90DDocument1 pageElbow 0,75-6000 SW 90DJovianto PrisilaNo ratings yet

- CIAYO Comics Logo Usages PDFDocument10 pagesCIAYO Comics Logo Usages PDFSyifa Putri YudianaNo ratings yet

- "Go Lean, Think Green": Manufacturers Alliance Group, IncDocument12 pages"Go Lean, Think Green": Manufacturers Alliance Group, IncmoonstarNo ratings yet

- Raghav ResumeDocument1 pageRaghav ResumeRam GopalNo ratings yet

- Simplified Com Ai Presentation Maker Agile WorkflowDocument3 pagesSimplified Com Ai Presentation Maker Agile Workflowagile-workflow-presentationsNo ratings yet

- EMIS - Tamil Nadu Schools FOR HIGHER SECONDARYDocument9 pagesEMIS - Tamil Nadu Schools FOR HIGHER SECONDARYVelmurugan JeyavelNo ratings yet

- Plant Disease Detection Using Drones in Precision AgricultureDocument20 pagesPlant Disease Detection Using Drones in Precision AgricultureDavid Castorena MinorNo ratings yet

- GM Ambitious Enclave Green Brochure FinalDocument23 pagesGM Ambitious Enclave Green Brochure FinalFazlur RashoolNo ratings yet

- WFG 2013 enDocument28 pagesWFG 2013 enIhcene BoudaliNo ratings yet

- StockMarketPredictionTermPaper Final1Document4 pagesStockMarketPredictionTermPaper Final1sahil kolekarNo ratings yet

- MEMS Mobility Sensors For Motion Control - SMG130: Automotive ElectronicsDocument2 pagesMEMS Mobility Sensors For Motion Control - SMG130: Automotive ElectronicsdeepNo ratings yet

- Iot Questions For AssignmentsDocument1 pageIot Questions For AssignmentsKumar ChaitanyaNo ratings yet

- GEO 2 LectureDocument37 pagesGEO 2 LecturePin YNo ratings yet

- Choke - Surge - Anty-Surge - Stall: Nuovo PignoneDocument31 pagesChoke - Surge - Anty-Surge - Stall: Nuovo Pignoneadam yassine100% (4)

- Graphical Construction Glossary Roofs and Roofing. Roof Features Parapet GutterDocument25 pagesGraphical Construction Glossary Roofs and Roofing. Roof Features Parapet GutterIeeeChannaNo ratings yet