Professional Documents

Culture Documents

State Failure As A Risk Factor - How Natural Events Turn Into Disasters

State Failure As A Risk Factor - How Natural Events Turn Into Disasters

Uploaded by

Marien BañezOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

State Failure As A Risk Factor - How Natural Events Turn Into Disasters

State Failure As A Risk Factor - How Natural Events Turn Into Disasters

Uploaded by

Marien BañezCopyright:

Available Formats

SH1639

State failure as a risk factor – How natural events turn into disasters

Whether natural events turn into disasters depends critically on the coping and adaptive capacities of

governments. In 2010, when an earthquake with a magnitude of 7.0 on the moment magnitude scale

struck Haiti, the consequences were devastating. More than 220,000 people were killed in the disaster

(CRED EM-DAT 2011), as many people injured and 1.5 million became homeless. In some villa ges,

about 90 per cent of buildings were destroyed. Although it was the worst earthquake in Haiti in 200

years and the epicenter was only about 25 km from Port au Prince, the capital of the country, it soon

became clear that the impact of the earthquake was so severe and destructive not only because of its

natural force, but also the almost complete failure of the Haitian State, as could be observed later

through a comparison with a much stronger earthquake that occurred in Chile.

Weak governance – big risk

Weak governance is one of the most important risk factors with regard to the impact of natural hazards,

which is shown, inter alia, in the number of deaths: states with strong institutions have fewer deaths

after extreme natural events than those with weak or inexistent institutions (Kahn 2005).

In states considered weak according to the Failed States index of the Fund for Peace, the governme nt

cannot or can only partially provide its citizens with basic government functions, such as security and

welfare benefits, or rule of law. Many of these states primarily act as “skimming devices”: most

available funds are used for their own personnel and do not flow into public interest oriented

development processes. Often, there is an oversized police and military apparatus, which cannot ensure

appropriate security due to poor education and low pay of their personnel, especially in the lower

echelons, as well as widespread corruption. Most weak states have only a small taxable income base

since no taxes can be collected from the usually large segments of poor people, and the citizens with

higher income are not properly recorded or are rarely asked to pay because of corruption. The resulting

poor condition of infrastructure leads to further weakening of the enforcement capacity of the state. In

addition, there is often a lack of qualified personnel or the administration is characterized by

clientelistic structures that lead to inefficient administrative procedures and, not infrequently, to

individuals taking advantage of the state and its structures for private interests.

The effects of weak governance, particularly on the capacities of societies to cope with and adapt to

natural hazards are enormous. The state is rarely able or ready to establish a functioning system of

disaster preparedness and to implement it. Due to the lack of monitoring capacities of the governme nt

and high levels of corruption, building regulations – if they exist – can be bypassed. The development

of disaster preparedness plans is often prevented by the low qualification or sheer non-existence of

state personnel. Further, insufficient government revenue hinders the regular conduct of awareness

campaigns and the installation of early warning systems and information portals. Also, public health

care in poor states is often provided insufficiently. Only rarely is it possible to develop public services

so as to be prepared for coping with disasters. Lack of investment in education and research, and the

resulting low level of education limit the possibilities of the population to develop strategies to cope

with disasters and thus reduce the adaptive capacities of society (see box on Haiti). Yet, examples from

states that have succeeded in recent years in significantly strengthening their institutions prove much

more successful in coping with and adapting to disasters (see box on Chile).

01 Handout 2 *Property of STI

Page 1 of 4

SH1639

When neighbors save lives

How hard a natural hazard strikes a society does not exclusively depend on the strength of the state.

For instance, there are relatively strong, autocratic states that theoretically have the capacity of

functioning disaster preparedness, but not the will to protect their citizens accordingly. Examples

include the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and Myanmar. For instance, when Cyclone Nargis

swept through the Bay of Bengal in 2008 and devastated five regions of Myanmar, including the former

capital of Yangon, it quickly became clear that that the military regime ruling the country was barely

able to provide on its own the urgently needed emergency aid for the affected population. In addition,

the Junta declared the 15,000 km2 of Irrawaddy Delta a “restricted area” to international aid workers

and journalists, making it greatly difficult to supply aid to the victims.

However, in addition to national disaster management systems, there are other effective social

mechanisms that can help to reduce the disaster risk. Scientists and practitioners who deal with the

issue agree that, particularly in the first days after a disaster such as an earthquake, a flood or a cyclone,

it is above all the informal aid provided in the local context and solidarity among people that are

critical. In fact, most first aid is provided by family and neighborhood networks. In addition, almost

all societies have coping and adaptation strategies at their disposal. In fact, many disasters are not

single events; they occur every year and repeatedly reveal to the affected societies the need of

developing coping and adaption strategies, such as a change in building design or the creation of

evacuation plans.

Supporting, not replacing the State

The relief aid and development work faces immense challenges, given the coincidence of weak

governance and extreme natural events. With which actors and institutions is collaboration possible in

the event of a disaster? How can these actors be strengthened? Which tasks can be assumed by the

government and which by civil society or private actors? It is certain that both government and local

civil society play a crucial role in disaster preparedness and that each must be strengthe ned

accordingly.

01 Handout 2 *Property of STI

Page 2 of 4

SH1639

Given the often severe corruption, the low capacities of the state and a virtually non-existent local civil

society, it seems often easier for international public donors to entrust the funds earmarked for disaster

preparedness and reconstruction after a disaster to international NGOs that implement their projects.

However, this creates the danger of removing responsibility from the state and weakening it even more

in the long term.

In Haiti, the risk of undermining state authority by the international community is currently real. Joel

Boutroué, Adviser to the Haitian Prime Minister, pointed out at the Conference of the Internatio na l

Council of Voluntary Agencies (ICVA) in Geneva, Switzerland, in March 2011 that hardly any real

cooperation between the Haitian Government and the international community is evident; instead,

there is a climate of mistrust. Rather than closely accompanying the Government’s work and taking

common action, the promised government aid is handled through international NGOs or not even

disbursed. This creates a vicious circle: the Government does not have the necessary financ ia l

resources to implement actions and therefore cannot demonstrate success, which in turn would be the

prerequisite for gaining assertiveness and obtaining additional funds. Therefore, there is currently a

real risk that the Haitian Government will be replaced by international NGOs in the implementa tio n

and planning processes.

Disaster risk reduction and disaster management in fragile states is undoubtedly a challenging task.

However, it cannot be solved by undermining local state actors. As long as the concerned governme nts

have a minimum level of development targets, they must be supported in close partnership in bilateral

and multilateral development cooperation when they implement and execute development measures.

More responsibility and more money must gradually be transferred to them. This can be successful if

the governments are supported in setting up effective anti-corruption programmes. In addition, long-

term plans to create local government capacities must be developed, training programmes set up, and

the support of government officials by international experts guaranteed. According to the subsidiar ity

principle, which states that the higher and more remote level of government should only regulate what

the lower level or the nearest level to the citizens cannot, it is important that local governme nt

structures in particular be strengthened. They must be allowed access to the institutions in charge of

reconstruction and disaster preparedness.

Civil society as a lever to strengthen the state

Only when bilateral development cooperation is impossible because of gross human rights violatio ns

or extremely weak governance resources can be provided solely through NGOs. This approach,

however, should remain temporary. An important function of NGOs is, in this case, also the

strengthening of state structures in disaster preparedness. The member organizations of Bündnis

Entwicklung Hilft achieve this by involving government officials in the planning processes and, with

the help of their partner organizations, supporting the local population to actively demand state action

in the field of disaster preparedness and beyond. Examples include the consideration of local

government officials in local risk assessments or in planning and training processes, or the influe nce

of national political processes and legislative procedures in disaster risk reduction.

In parallel to building state capacity, civil society’s coping and adaptive capacities should be

encouraged at the local level. If the government fails in disaster preparedness, then the catastrophic

consequences of natural disasters can at least be mitigated at a lower level. The organizations that

01 Handout 2 *Property of STI

Page 3 of 4

SH1639

collaborate within Bündnis Entwicklung Hilft promote the already set up social, self-help strategies,

for instance, by using traditional knowledge of construction design or pre-existing early warning

systems and further developing them with local partner organizations.

These organizations also support communities that, for example, due to migration or abject poverty,

have no disaster preparedness mechanisms by ensuring a common risk analysis, transferring

knowledge and providing training, and supporting necessary preventive measures, such as dike

reinforcements or salt-water sealing for water wells.

The work of Bündnis Entwicklung Hilft is based on the assumption that, in the face of extreme natural

events, only disaster risk management that is firmly rooted in local structures has a lasting effect.

Reference:Birkmann, J., et al. (n.d.). WorldRiskReport 2011. Retrieved from

http://www.preventionweb.net/files/21709_worldriskreport2011.pdf

01 Handout 2 *Property of STI

Page 4 of 4

You might also like

- Test Bank Principles of Incident Response and Disaster Recovery 1st Edition WhitmanDocument8 pagesTest Bank Principles of Incident Response and Disaster Recovery 1st Edition Whitmanmarina meshiniNo ratings yet

- DRRR G2Document6 pagesDRRR G2Johnlloyd CahuloganNo ratings yet

- Nature Resilience by Erwann Michel KerjanDocument1 pageNature Resilience by Erwann Michel KerjanDiana MitroiNo ratings yet

- Manuel, Shanin Kyle C. - SDG 13 ReflectionDocument4 pagesManuel, Shanin Kyle C. - SDG 13 ReflectionShanin Kyle ManuelNo ratings yet

- Primer On The Disaster Risk Reduction and ManagementDocument76 pagesPrimer On The Disaster Risk Reduction and ManagementGil L. Gregorio100% (1)

- TI - Corruption in AidDocument7 pagesTI - Corruption in AidZi Jian 雷No ratings yet

- DRRRDocument14 pagesDRRRsesaldochristianaameliaNo ratings yet

- Reaction PaperDocument3 pagesReaction PaperMa YaNo ratings yet

- Working Paper World Bank3Document59 pagesWorking Paper World Bank3dhrumeepalanNo ratings yet

- The Political Economy of "Natural" Disasters: Charles Cohen Eric WerkerDocument47 pagesThe Political Economy of "Natural" Disasters: Charles Cohen Eric WerkerBogdan HgbNo ratings yet

- Analyzing The Role of States' in Face of A Global PandemicDocument7 pagesAnalyzing The Role of States' in Face of A Global PandemicISHA HUSSAINNo ratings yet

- Keefer Disastrous ConsequencesDocument25 pagesKeefer Disastrous ConsequencesGiovani VargasNo ratings yet

- International Strategy For Disaster ReductionDocument5 pagesInternational Strategy For Disaster ReductionMia InigoNo ratings yet

- Aquino - Comprehensive ExamDocument12 pagesAquino - Comprehensive ExamMa Antonetta Pilar SetiasNo ratings yet

- Improving - Humanitarian Aid How To Make Relief More Efficient - and EffectiveDocument8 pagesImproving - Humanitarian Aid How To Make Relief More Efficient - and EffectiveEl JuancezNo ratings yet

- Aid Corruption Policy Paper 2007Document27 pagesAid Corruption Policy Paper 2007Jetro KaronNo ratings yet

- Extract Scenario Plans and Projects by The Rockefeller Foundation: A CommentaryDocument11 pagesExtract Scenario Plans and Projects by The Rockefeller Foundation: A CommentaryCarl CordNo ratings yet

- Social JusticeDocument3 pagesSocial Justicehana humairaNo ratings yet

- FINAL States of Fragility Highlights DocumentDocument16 pagesFINAL States of Fragility Highlights DocumentJENNY NAVANo ratings yet

- Building Social Resilience Protecting and Empowering Those Most at RiskDocument35 pagesBuilding Social Resilience Protecting and Empowering Those Most at RiskMinhHyNo ratings yet

- Reaction Paper On The Article: DBM Trims Departments' Budget For COVID FundDocument3 pagesReaction Paper On The Article: DBM Trims Departments' Budget For COVID FundMa YaNo ratings yet

- The Deepening Crisis - de Dios Et Al. 2004Document26 pagesThe Deepening Crisis - de Dios Et Al. 2004Lee AlcalanteNo ratings yet

- United Nations Global Assessment Report On Disaster Risk ReductionDocument288 pagesUnited Nations Global Assessment Report On Disaster Risk ReductionUNDP TürkiyeNo ratings yet

- Eapp Position PaperDocument8 pagesEapp Position PaperPatricia PabresNo ratings yet

- Disaster MNGTDocument12 pagesDisaster MNGTPhil Sanver MallorcaNo ratings yet

- Building Urban ResilienceDocument3 pagesBuilding Urban Resilienceprincess sanaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 13 - Disaster Preparedness and Management: 13883-Asia - Book Page 481 Tuesday, December 11, 2001 11:54 AMDocument22 pagesChapter 13 - Disaster Preparedness and Management: 13883-Asia - Book Page 481 Tuesday, December 11, 2001 11:54 AMJudilyn RavilasNo ratings yet

- Exposure and VulnerabilityDocument125 pagesExposure and VulnerabilityMark Rouie FelicianoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6Document20 pagesChapter 6Nikhil ShuklaNo ratings yet

- Towards Good Humanitarian Government: HPG Policy Brief 37Document4 pagesTowards Good Humanitarian Government: HPG Policy Brief 37Kaycee CablayanNo ratings yet

- Strengthening Local Disaster ManagementDocument12 pagesStrengthening Local Disaster ManagementStratbase ADR InstituteNo ratings yet

- Post-Conflict Civilian CapacityDocument3 pagesPost-Conflict Civilian Capacityapi-242666861No ratings yet

- World Development: Jeroen KlompDocument10 pagesWorld Development: Jeroen KlompMaryam OvaisNo ratings yet

- Economic Crises and Natural Disasters: Coping Strategies and Policy ImplicationsDocument16 pagesEconomic Crises and Natural Disasters: Coping Strategies and Policy ImplicationsSaqib NaeemNo ratings yet

- Reaction Paper On The Philippine Risk Management Status Report of 2019 (Vanessa Azurin)Document5 pagesReaction Paper On The Philippine Risk Management Status Report of 2019 (Vanessa Azurin)Jenny Juniora AjocNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 and The Need For Dynamic State Capabilities:: An International ComparisonDocument30 pagesCOVID-19 and The Need For Dynamic State Capabilities:: An International ComparisonTomas TomicNo ratings yet

- Identify Key Actors in Disaster Response and Recovery in Zimbabwe and Discuss Their RolesDocument9 pagesIdentify Key Actors in Disaster Response and Recovery in Zimbabwe and Discuss Their RolesArdrian SizibaNo ratings yet

- Natural Disasters, Conflict, and Human Rights: Tracing The ConnectionsDocument15 pagesNatural Disasters, Conflict, and Human Rights: Tracing The Connectionsumairah4277No ratings yet

- The Material Risks of Gender Based Violence in Emergency Settings 2020 PDFDocument9 pagesThe Material Risks of Gender Based Violence in Emergency Settings 2020 PDFmiriamuzNo ratings yet

- Kenya and Nigeria Where Funds Have Been Allocated To Fueling The Growth of Small-Scale Cottage IndustriesDocument4 pagesKenya and Nigeria Where Funds Have Been Allocated To Fueling The Growth of Small-Scale Cottage IndustrieslemonsparklesNo ratings yet

- Capital and Collusion: The Political Logic of Global Economic DevelopmentFrom EverandCapital and Collusion: The Political Logic of Global Economic DevelopmentNo ratings yet

- Credeconomiclosses PDFDocument33 pagesCredeconomiclosses PDFOsmany OrozcoNo ratings yet

- Lacanaria Et AlDocument142 pagesLacanaria Et AlTlf SlcNo ratings yet

- Disaster Management Role of GovernmentDocument3 pagesDisaster Management Role of GovernmentPramod Nair100% (1)

- 9-24-11 Statement at UN On Horn of Africa - in TemplateDocument2 pages9-24-11 Statement at UN On Horn of Africa - in TemplateInterActionNo ratings yet

- Social Science and Social ProblemsDocument4 pagesSocial Science and Social Problemsshiella mae baltazar100% (2)

- How Regional Co-Operation Helped To Confronting Covid-19 Crisis?Document8 pagesHow Regional Co-Operation Helped To Confronting Covid-19 Crisis?Md. Imran HosenNo ratings yet

- Covid 19Document6 pagesCovid 19Ngọc Thảo NguyễnNo ratings yet

- The Economic Impact of The PandemicDocument5 pagesThe Economic Impact of The Pandemick.agnes12No ratings yet

- It Is The Responsibility of A Government To Protect Its Citizens From Natural DisastersDocument5 pagesIt Is The Responsibility of A Government To Protect Its Citizens From Natural DisastersSons YesuNo ratings yet

- Is The Elimination of Global Poverty A Realistic Aim?Document2 pagesIs The Elimination of Global Poverty A Realistic Aim?snorkellingkittyNo ratings yet

- Intergovernmental Relations: Miftahudin Rian SashaDocument34 pagesIntergovernmental Relations: Miftahudin Rian SashaRian FahminuddinNo ratings yet

- Making Globalization Work For All: Development Programme One United Nations Plaza New York, NY 10017Document48 pagesMaking Globalization Work For All: Development Programme One United Nations Plaza New York, NY 10017Bagoes Muhammad100% (1)

- L2 Disaster From Different PerspectivesDocument4 pagesL2 Disaster From Different Perspectivesmaerussel33No ratings yet

- LECTURE 2 Dev FinanceDocument5 pagesLECTURE 2 Dev FinanceMark KinotiNo ratings yet

- Threatened Silenced and Sidelined Version With CoverDocument12 pagesThreatened Silenced and Sidelined Version With CoverKezia LavanNo ratings yet

- How Disasters Disrupt Development: Recommendations For The Post-2015 Development FrameworkDocument4 pagesHow Disasters Disrupt Development: Recommendations For The Post-2015 Development FrameworkOxfamNo ratings yet

- Making The Impossible Possible: An Overview of Governance Programming in Fragile ContextsDocument13 pagesMaking The Impossible Possible: An Overview of Governance Programming in Fragile ContextsOxfamNo ratings yet

- Making The Impossible Possible: An Overview of Governance Programming in Fragile ContextsDocument13 pagesMaking The Impossible Possible: An Overview of Governance Programming in Fragile ContextsOxfamNo ratings yet

- Revitalizing American Governance: Required: Moderation, Common Sense, and CourageFrom EverandRevitalizing American Governance: Required: Moderation, Common Sense, and CourageNo ratings yet

- Reaction PaperDocument1 pageReaction PaperMarien BañezNo ratings yet

- Concept PaperDocument3 pagesConcept PaperMarien BañezNo ratings yet

- Urbanization and Risk - Challenges and OpportunitiesDocument6 pagesUrbanization and Risk - Challenges and OpportunitiesMarien BañezNo ratings yet

- 01 Handout 6Document8 pages01 Handout 6Marien BañezNo ratings yet

- Health and Healthcare As Risk Factors: "The Double Burden of Diseases"Document7 pagesHealth and Healthcare As Risk Factors: "The Double Burden of Diseases"Marien BañezNo ratings yet

- Sta - Catalina Integraded National High School: MemberDocument2 pagesSta - Catalina Integraded National High School: MemberMarien BañezNo ratings yet

- Police Log August 26, 2016Document10 pagesPolice Log August 26, 2016MansfieldMAPoliceNo ratings yet

- Construction Project CharterDocument2 pagesConstruction Project CharterKushagra SharmaNo ratings yet

- Presented By: MR Jason M BaswelDocument21 pagesPresented By: MR Jason M BaswelJonas valerioNo ratings yet

- Proud of Their Dustbin Collision Course Pre Int UNIT 8Document3 pagesProud of Their Dustbin Collision Course Pre Int UNIT 8Danku MártonNo ratings yet

- Disaster and Risk Reduction Part 2Document2 pagesDisaster and Risk Reduction Part 2Hyungee LeeNo ratings yet

- Table A: List of All Commitments/contributions and Pledges As of 20 January 2010Document24 pagesTable A: List of All Commitments/contributions and Pledges As of 20 January 2010haitivshaitiNo ratings yet

- Disaster Preparedness Community ProfilingDocument17 pagesDisaster Preparedness Community ProfilingGrachelle RamirezNo ratings yet

- D&D Campaign ConceptsDocument4 pagesD&D Campaign Conceptsfedorable1No ratings yet

- Executive Order 41 Frequently Asked Questions v2020 2Document4 pagesExecutive Order 41 Frequently Asked Questions v2020 2Virginia Department of Emergency ManagementNo ratings yet

- BibliographyDocument2 pagesBibliographyapi-197414643No ratings yet

- Documente Nautice Houston BalboaDocument2 pagesDocumente Nautice Houston BalboaUnknown11No ratings yet

- Question: "The Himalayas Are Highly Prone To Landslides. "Discuss The Causes and Suggest Suitable Measures of Mitigation. SolutionDocument3 pagesQuestion: "The Himalayas Are Highly Prone To Landslides. "Discuss The Causes and Suggest Suitable Measures of Mitigation. SolutionMukund Anand 16BIT0287No ratings yet

- Staircase BranzDocument5 pagesStaircase BranzsdewssNo ratings yet

- LP Science 4.15.2024Document7 pagesLP Science 4.15.2024Jeric Rey AuditorNo ratings yet

- On Earthquake Preparedness in IsraelDocument14 pagesOn Earthquake Preparedness in IsraelReady.org.il - ספריית החירום הלאומיתNo ratings yet

- Example Fire and Emergency Evacuation PlanDocument6 pagesExample Fire and Emergency Evacuation PlanMateo RosasNo ratings yet

- 20 Words We Owe To William ShakespeareDocument4 pages20 Words We Owe To William ShakespeareBuşatovici LucicaNo ratings yet

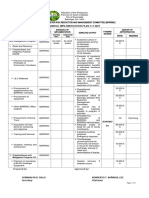

- Bces-Sdrrm Action Plan 2023-2024Document1 pageBces-Sdrrm Action Plan 2023-2024Nimfa Asindido90% (10)

- UNOSAT A3 SituationMap Samar Island 20141206 HagupitDocument1 pageUNOSAT A3 SituationMap Samar Island 20141206 Hagupitkickerzz04No ratings yet

- Disaster Recovery PlanDocument4 pagesDisaster Recovery PlantingishaNo ratings yet

- UltraTech - Mailer - Tips To Construct Earthquake Resistant BuildingsDocument6 pagesUltraTech - Mailer - Tips To Construct Earthquake Resistant Buildingsjosh_mchnNo ratings yet

- Framework To Manage Humanitarian Logistics in Disaster Relief Supply Chain Management in India.Document37 pagesFramework To Manage Humanitarian Logistics in Disaster Relief Supply Chain Management in India.M Irfan KemalNo ratings yet

- VolcanoDocument84 pagesVolcanoJM LomoljoNo ratings yet

- Lancelot and GuinevreDocument8 pagesLancelot and GuinevreLili TigerNo ratings yet

- Ophelias MadnessDocument10 pagesOphelias MadnessalannahliebertNo ratings yet

- Family Preparedness HomeworkDocument4 pagesFamily Preparedness HomeworkAgnes VerzosaNo ratings yet

- Aircraft Accident Investigation: The Uk Overseas TerritoriesDocument72 pagesAircraft Accident Investigation: The Uk Overseas TerritoriesLex Nunes FPireauxNo ratings yet

- BDRRMC 2023 Ppa 2 3 23Document2 pagesBDRRMC 2023 Ppa 2 3 23Glenn Ryan CatenzaNo ratings yet

- 2023 Week 1 Risk Mapping Regional Tourism PPT 2023 IntroductionDocument88 pages2023 Week 1 Risk Mapping Regional Tourism PPT 2023 IntroductionAditya ChoudharyNo ratings yet