Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 159.237.12.142 On Fri, 08 Jan 2021 11:54:27 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 159.237.12.142 On Fri, 08 Jan 2021 11:54:27 UTC

Uploaded by

Pedro PabloOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 159.237.12.142 On Fri, 08 Jan 2021 11:54:27 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 159.237.12.142 On Fri, 08 Jan 2021 11:54:27 UTC

Uploaded by

Pedro PabloCopyright:

Available Formats

The Argument from Nominal-Notable Comparisons, 'Ought All Things Considered', and

Normative Pluralism

Author(s): Mathias Slåttholm Sagdahl

Source: The Journal of Ethics , December 2014, Vol. 18, No. 4 (December 2014), pp. 405-

425

Published by: Springer

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43895887

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Springer is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of

Ethics

This content downloaded from

159.237.12.142 on Fri, 08 Jan 2021 11:54:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

J Ethics (2014) 18:405-425

DOI 1 0. 1 007/s 1 0892-01 4-9 1 79-9

The Argument from Nominal-Notable Comparisons,

'Ought All Things Considered', and Normative

Pluralism

Mathias Slàttholm Sagdahl

Received: 17 September 2013 /Accepted: 19 June 20 14 /Published online: 12 September 2014

© Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2014

Abstract The idea that morality and prudence are incommensurable normative

domains - a central idea in normative pluralism - tends to be rejected because of the

argument from nominal-notable comparisons. The argument relies on a premise

that there are situations of moral-prudential conflict where we have a clear intuition

that there are things we ought to do "all things considered". It is usually concluded

that this shows that morality and prudence must be comparable. I argue that nor-

mative pluralists, who defend this type of incommensurability, can account for these

intuitions by (1) arguing that an "ought all things considered" need not presuppose

inter-type comparability among the reasons it covers, and (2) by endorsing more

sophisticated theories of prudence; theories for which there are good, independent

reasons to endorse, in any case. By following these steps, normative pluralism does

not need to have the counterintuitive implications it is often thought to have.

Keywords Comparability of reasons • Morality and prudence • Normative

pluralism • Ought 'all things considered'

Consider the thought that practical normativity is not a unified domain, but that it

rather consists of several incommensurable domains, such as morality and prudence.

With this idea in mind, we can think that there are moral reasons and prudential

reasons, but that there are no plain reasons (no reasons simpliciter). Similarly, we

can think that while there are things one morally ought to do, and things that one

prudentially ought to do, there are no things we just plain ought to do.1 We can call

an idea like this normative pluralism. Although this kind of theory has been

1 I have adopted these terms from McLeod (2001).

M. S. Sagdahl (El)

Department of Philosophy, Classics, History of Art and Ideas, Centre for the Study of Mind in

Nature (CSMN), University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

e-mail: m.s.sagdahl@csmn.uio.no

Ô Springer

This content downloaded from

159.237.12.142 on Fri, 08 Jan 2021 11:54:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

406 M. S. Sagdahl

advocated, most pr

literature on norm

due to an argumen

theory. This is "th

The argument fro

domains such as t

incommensurable with each other since there are at least some cases where it is

obvious that moral-prudential conflicts about what to do can be resolved and that there

is something one ought all things considered to do. This "ought all things considered"

is then identified with what one "just plain ought" to do.

The cases that the argument from nominal-notable comparisons appeals to are cases

where an option supported by very strong reasons of one kind is compared with an option

supported by very weak reasons of another kind. For example, we may compare our very

strong moral reasons to save a child from drowning in a pond with the very weak

prudential reason not to do so because we want to avoid getting our shoes wet. In these

cases, we would like to say that the very weak reason of the one kind is outweighed by the

strong reasons of the other kind. There must therefore be an overarching, more general

domain of normativity under which the two types of reasons can be subsumed and

compared in strength. The more comprehensive nature of that domain is what explains

why the resultant 'ought all things considered' should be identified as a plain ought.

If the latter type of 'ought' exists, which subsumes and compares the other

normative domains, then normative pluralism is false. However, it is my claim that

the argument from nominal-notable comparisons fails to show that this kind of

'ought' exists. It is therefore not the decisive argument against normative pluralism

that it has often been considered to be. The most important line of response for the

normative pluralist that I shall be pursuing is to show that the pluralist can account

for the existence of an "ought all things considered" without presupposing any

comparability between the different types of reasons and without understanding this

ought as a result of subsuming the different normative domains. Doing so for the

relevant cases also involves appealing to a more sophisticated theory of prudence

than what generally seems to be presupposed by proponents of the argument from

nominal-notable comparisons. If the pluralist can account for the existence of an

"ought all things considered" in these cases, normative pluralism does not have the

counterintuitive implications it is argued to have.

I will begin, in Sect. 1, by explaining the structure of the argument, and what

conditions need to be satisfied in order for an example to properly target normative

pluralism. In Sect. 2, 1 introduce a way to understand the notion of "ought all things

considered" that is consistent with normative pluralism. My main response to the

argument is in Sect. 3, where I argue that typical examples of nominal-notable

comparisons do not seem to satisfy the conditions laid out in Sect. 1, and that the

central intuition that the argument relies on can be accommodated by the pluralist

understanding of "ought all things considered" laid out in Sect. 2. My proposal is

that plausible theories of prudence do not make room for the existence of genuine

nominal-notable cases. In Sect. 4, 1 assess to what degree the answer I gave in Sect.

3 is a sufficient response on behalf of normative pluralism. I argue that unless one

denies the relevancy of the prudential considerations laid out in Sect. 3, the

Ö Springer

This content downloaded from

159.237.12.142 on Fri, 08 Jan 2021 11:54:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Argument from Nominal-Notable Comparisons 407

argument from nominal-notable comparisons does not have the

believed to have - even if some nominal-notable cases were to

consider two alternative variants of the argument from nom

isons, and I conclude that neither of them succeeds as decisiv

normative pluralism.

1 The Structure of the Argument

The first prominent use of the argument, by Ruth Chang, is

normative pluralism, but against the existence of value incom

moral and prudential values. (Chang 1997)2 She mentions that i

as if there is any overarching value (or 'covering value' in Ch

terms of which the moral merit and the prudential merit of op

If this is right, we can say what is best morally and what is bes

what is the best option overall. But Chang argues that it is plausib

actually is such an overarching value, and this, she thinks, can

calls 'nominal-notable comparisons'. Nominal-notable comparis

we compare options that are valuable in different respects (i.e. s

kinds of values), but where one option is valuable in the first resp

marginal degree, but where the other option is valuable in th

notable degree. In these cases, Chang thinks it is plausible to be

value outweighs the 'nominal' value, and hence that there mu

value that takes these two kinds of values as parts and from

overall judgments about overall value. With respect to moral an

asks us to consider the following case:

You can either save yourself a small inconvenience, or you

stranger severe physical and emotional trauma. Suppose t

only nominal prudential [...] value, while the other bears no

[...]. We can say more than that the one act is better morally

better prudentially. We can also say that, with respect to bo

moral value, the latter act is better: given both values, savi

better overall. [. . .] There must therefore be a covering value

comparisons of moral and prudential merits proceed, one th

and prudential values as components. (Chang 1997, p. 32)

The argument is basically an appeal to a certain sort of cases,

we already know or find it highly intuitive that one option is

than the other. Because these judgments presuppose an overar

must be such a value if the judgments are true. The reason w

know or find it highly intuitive that one option is more valuab

the extreme nature of the comparison. Because the com

something which is notably and only nominally valuable (in di

supposed to be especially clear that the values in question can

2 The argument is also used in, for example, Regan (1997), Parfit (2011), a

^ Springer

This content downloaded from

159.237.12.142 on Fri, 08 Jan 2021 11:54:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

408 M. S. Sagdahl

Although Chang fo

normative pluralism

is no overarching

compared.3 It app

normative standpoin

marginal that they

the other standpoin

reason not to get y

reason you have to

claimed that all thin

seems that there m

prudential reasons a

less obvious cases as well.

The argument from nominal-notable comparisons crucially relies on judgments

about cases. However, the way that these cases are often set up can make us doubt that

they are able to target normative pluralism in an adequate manner, because the

judgments that they appeal to are not necessarily inconsistent with normative

pluralism. Take the example with the drowning child. In this case we are confronted

with an option supported by a substantial moral reason to save the child and another

option supported by a prudential reason not to save the child that is no more than

nominal. But from the fact that you have both these reasons, of different types, it by no

means follows that there is a conflict between the overall verdicts of the moral

standpoint and the overall verdicts of the prudential standpoint, such that they produce

conflicting verdicts about what one ought to do. If one wants to properly target

normative pluralism and claim that it has counterintuitive results, it is not enough to

show that there could be two options where one is supported by a notable moral reason

and the other option supported by only a nominal prudential reason. Reasons are, after

all, only things that count in favour (pro tanto ) of an action. For the argument to be

effective one must also show that this nominal prudential reason is sufficient to make it

the case that one prudentially ought to do what the reason counts in favour of doing.

Unless this is done, one might think that even though there is a nominal prudential

reason to not save the child, there are other prudential reasons that outweigh this

nominal reason. Since the bare fact of a prudential reason counting in favour of not

saving the child is not sufficient to guarantee that one prudentially ought to not save the

child, we can, I shall argue, respond to the argument by pointing out the possibility that

there actually is something one ought to do "all things considered" in these cases that

is consistent with normative pluralism.

A construal of the argument that properly targets normative pluralism must

therefore consist of the genuine possibility of a case with the following elements:

3 The question of normative pluralism is, at least prima facie , distinct from the question of value

pluralism. First, one can think that although there are several types of value, they do not provide several

types of reasons. Second, normative pluralism seems consistent with thinking that there is only one type

of value, as there can be different standards as to how that value is to be distributed. Sidgwick, for

example, reached his famous "dualism of practical reason" on the basis of a hedonistic value theory,

where the "rationality of self-regard" seemed just as undeniable as the rationality of a moral utilitarian

principle (Sidgwick 1981).

Springer

This content downloaded from

159.237.12.142 on Fri, 08 Jan 2021 11:54:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Argument from Nominal-Notable Comparisons 409

(1) A type 1 requirement to F supported by a notable type 1

(2) A type 2 requirement or permission to not F which is sup

than a nominal type 2 reason.

(3) A clear intuition, considered judgment, or knowledge tha

considered to F in the case at hand.

If (1)- (3) is true, then the explanation of why one ought all things considered to F

must be that type 1 and type 2 reasons are not incommensurable and that there is an

overarching normative standpoint from which one ought to F. Only if one can show

that there is a genuine conflict between the type 1 requirement and the type 2

requirement, will the normative pluralist be unable to account for the intuition that

there is something one ought all things considered to do, in the case at hand.

2 The Pluralist Construal of 'Ought All-Things Considered'

We certainly say that there are things we just plain ought to do or ought all things

considered to do, and it seems that we can at least sometimes say so truly. For

instance, we would say that you just plain ought not to drink poison, or that all

things considered you ought to treat your friends well. To reject these statements as

false does not seem like a natural way to go, and so the pluralist needs to make sense

of them. However, this sense will inevitably diverge from the way many non-

pluralists understand such statements. Chang, for example, treats "all things

considered" as a placeholder term for the kind of standpoint that would do the job of

commensurating the standpoints that it takes as parts. (Chagn 2004a) With respect

to morality and prudence, she speaks of a commensurating standpoint that she

tentatively names "prumorality".4 (Chang 2004b) On this non-pluralist construal,

'ought all things considered', and the normative standpoint from which it springs,

seems to have two important features.

First, it is comprehensive , meaning that it is able to take every feature into

consideration and assign it a normative weight, where a given consideration could

either have a negative, zero, or positive weight with respect of favouring some

action. But being comprehensive is not enough for a standpoint to represent an

overarching, commensurating standpoint. Arguably, both morality and prudence can

also be understood as comprehensive normative standpoints that takes everything

into account.5 Suppose there is a conflict between morality and prudence such that

you prudentially ought to do F and morally ought to not do F. It seems natural to say

that the prudential standpoint can take into account all the things that the moral

4 Though the ought of 'prumorality' might be seen as a particular kind of ought, it can properly be

understood as a plain ought, because it is the only 'ought' which warrants having the status of 'oughts'. If

prumorality exists and takes morality and prudence as parts, then moral and prudential requirements

together explain what one 'prumorally ought'. In standing in an explanatory relationship to an ought, they

are better understood as reasons explaining an ought, rather than being genuine oughts themselves. See

Broome (2013).

5 We can in any case imagine several competing standpoints concerning what you ought to do, which all

take everything into account but assign a different set of weights to the considerations. Comprehen-

siveness can therefore not be sufficient.

Springer

This content downloaded from

159.237.12.142 on Fri, 08 Jan 2021 11:54:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

410 M. S. Sagdahl

standpoint takes in

vice versa). The n

properly) seem to b

account; the only di

things they take in

somewhat misleadin

oughts, like moral o

all things". It makes

ought to do F and I

just plain ought to

that the ought is a

just a partial judgm

The plain ought is

qualified oughts and

would represent jus

of oughts, rather th

sense take priority

ought to be able to

to have what Davi

being the normativ

The real disagreem

whether there is

somehow more norm

of "prumorality" s

existence, she claim

isons. Normative pl

But how, then, can

many situations, so

Why does it seem t

poison, and to trea

authoritative ought

not the result of so

them up against each

the prudential ough

considered" can be

are in agreement, w

you ought to F bot

morally and pruden

6 John Broome states th

considered' rather refer

2013). However, as the

enough to take us beyon

7 Copp argues that the i

8 Interestingly, Copp is o

required simpliciter , in s

status of the plain ought

^ Springer

This content downloaded from

159.237.12.142 on Fri, 08 Jan 2021 11:54:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Argument from Nominal-Notable Comparisons 41 1

can say truly that from all normative standpoints, you ough

commensuration of reasons is involved in reaching this concl

possible to take on a comprehensive perspective without com

the existence of some overarching standpoint takes mora

comparable parts. This interpretation also seems to captur

phrase "all things considered you ought to F". For it is a w

relevant standpoints, and the judgments of these standpoints in

having considered all the reasons and relevant features of

ought all things considered to treat one's friends well, in mos

ought to do so from all relevant normative standpoints: it is

prudential thing to do. By treating them well, one treats th

way, while maintaining the friendship that brings value to on

in most contexts, you ought not to inflict pain on yourself or

you, and so, from all relevant standpoints ought you not to d

However, it is clear that this approach to "ought all th

somewhat limited when it comes to determining a single option

since its application requires the relevant standpoints to be in

option that ought to be taken. But this is how the pluralist wil

morality and prudence differ, there is simply no way to get bey

is seen as irresolvable. One might think that this means that

ever facts about what we ought to do all things conside

quantification sense. There are two things to be said in respon

that the frequency with which the standpoints tend to agree

verdicts will depend on the specific content of these standpo

content to the terms 'morality' and 'prudence' before we can sa

will tend to conflict and to what extent they will harmonize. F

just blank placeholders for whatever moral theory and theory

correct. The second thing to be said is that even with these t

concepts, it seems likely that facts about what one just plain

marginal phenomena. They are, in fact, extremely comm

in situations of conflict.9 If morality requires you to do F and

to do G, there might be no fact as to whether you just plain ou

you just plain ought to do G, but there might be a fact that you

do cp, where doing cp is doing other options than F or G. For i

do F, it follows that you morally ought to not do anything tha

or excludes doing F in the context of that choice situation, a

prudence with respect to any option that is incompatible wit

So this is one type of 'all things considered' -fact that alway

there are things that we ought in a qualified sense. Another fa

if morality and prudence disagrees over whether I should do

that all things considered (in the quantificational sense) I ough

9 The truth of this claim depends on the supposition that we can avoid a h

standpoints and the number of normative oughts. The more oughts in play, t

tend to be. Evan Tiffany's version of normative pluralism clearly involves su

2007).

Ô Springer

This content downloaded from

159.237.12.142 on Fri, 08 Jan 2021 11:54:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

412 M. S. Sagdahl

This exclusive disjun

is true that I ought

3 The Possibility a

The quantification

pluralist to explain

But since the nomi

conflict, it seems

judgments that ther

will argue that the

pluralism are, in m

normative pluralist c

the agent ought to

For these particular

structure of (l)-(3),

we are operating wi

could actually be pr

when there is also a

reasons. The doubt

Typical examples

conflict between a

prudential requirem

consider a convers

presented as objecti

Norm: Norm's tele

very painful electr

Norm knows this,

is a misanthrope, a

also enjoys the tele

pleasure watching

Since we can suppo

show and given the

seem plausible:

(l') Norm is morally required not to watch Arrested Development.

(2') Norm is prudentially required to watch Arrested Development .

(3') Watching Arrested Development is, for Norm, all-things-considered

unjustified.

Dorsey then claims that if we accept (l')-(3'), which roughly correspond to (1)-

(3) above, then normative pluralism fails, at least prima facie. The reasons behind

the prudential requirement are clearly outweighed by the reasons behind the moral

requirement, he seems to think.

Ô Springer

This content downloaded from

159.237.12.142 on Fri, 08 Jan 2021 11:54:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Argument from Nominal-Notable Comparisons 413

Dorsey seems to be right in claiming that if a situation with

like (1X2') could obtain, then normative pluralism has co

quences, because we also tend to have the intuition that (3').

the case could be reconstructed such that "on virtually an

prudential value, Norm could obtain a very minor (thoug

benefit by committing a very grave moral sin". In this, I thi

Just as one can argue that a plausible moral theory would not

only a nominal moral benefit given a notable prudential

conversely, that a plausible prudential theory would not requi

nominal prudential benefit given a notable moral cost. I

plausibly make the case that prudence would require you not

To make this argument, one needs to rely on a more so

prudence than what Dorsey seems to rely on in his rejection

The theory would have to predict that extremely immoral beh

very minor benefit is not in your long-term interest. Conside

tradition in moral philosophy for arguing that morality has

and hence that self-interest requires moral behaviour,10 the pr

need in order to rebut the possibility of nominal-notable

demanding, since we only need the result that prudence

extremely immoral behaviour given that there is not very mu

only need a prudential theory that requires us to be minima

look at some general reasons for why it would be at least so

flout moral requirements. These are prudential reasons that c

other prudential reasons if the benefit is high enough, but that

favour of behaving in accordance with morality and which

defeating reasons that are only nominal.

First, and most obviously, a person often risks external so

violating moral demands. Some of morality's functions seem

mutually benefiting cooperation between individuals in a

everyone a chance to live a good life. Since people therefore

in that other people should behave morally, they tend to imp

who act in morally bad ways. Second, by violating moral

suffer from shame, guilt or similar "internal sanctions" con

emotional states or negative self-assessments which can redu

Third, besides these negative sanctions, many people experie

pleasure in doing the right thing and in contributing to th

seems likely to think that this could both result from a brute s

others as well as from having personal projects that inco

others.

However, it will be objected (as it often has been against th

justify morality in terms of self-interest) that the existenc

feelings, and projects are wholly contingent, and hence

prudential reasons to be moral is also contingent. Altho

generally and in the majority of cases, it is still possible th

10 See, for example, Gauthier (1986).

Ö Springer

This content downloaded from

159.237.12.142 on Fri, 08 Jan 2021 11:54:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

414 M. S. Sagdahl

where there are no

are no more than t

that no prudential

callous that he suff

he enjoys no pleasu

Iwill soon explain,

But let us first not

to be moral, then i

intuitive results in

would exist pruden

conflicting with t

things considered

have some counter-

a knockdown obje

general. It is, for i

of counterintuit

normative pluralis

reason, but merely

needs to be taken i

conserve a greater

especially since t

theoretical framew

not clear that any

But even with the

further considerat

violate notable mo

reason. The explana

and what personal

not the case, accor

psychology and yo

how to attain plea

they are. As a firs

keep in mind tha

account to evaluate

timelessly consid

callousness does no

1 1 Or if one does not,

moral.

12 This might either b

might think that rival

because one might thin

outweighed by the theo

themselves. See Singer

cases.

13 See for example Bricker (1980). Bricker thinks, however, that prudence must b

the agent desires.

40 Springer

This content downloaded from

159.237.12.142 on Fri, 08 Jan 2021 11:54:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Argument from Nominal-Notable Comparisons 415

of happiness or a good life, it will be said, requires possession

of empathy, sympathy, and moral virtues.

John Lemos contrasts two different conceptions of prude

and an absolute conception of prudence. (Lemos 2006) Where

prudence looks at what it would be in an agent's interest to

person he is and the character traits he has now, the latter

prudence argues that someone who is fully prudent in t

already have fallen short of the demands of prudence, since

looks at "what it is in an agent's interest to do if he had begu

consistent with the rational pursuit of self-interest".14 He th

which perspective is more important in assessing the extent

conforms to reasons, and for the extent to which the agent

fulfilling life. Lemos thinks that a proper prudential assessm

consists of an assessment according to the absolute criteria,

with athletics. We do not give someone a prize for performin

training. Instead we recognize people for their accomplis

ideals of good athleticism, and not relative to their preparat

One can point to several reasons why prudence would r

moral virtues, or at least avoid the worst moral vices, such as the extreme

callousness shown, for instance, by Norm and which seems to be a necessary trait

for anyone who agrees to violate a notable moral requirement merely for the sake of

a nominal prudential reason. If callousness or a similar trait is necessary for

someone to make this kind of choice, then a prudential theory which requires you to

avoid those traits suffices to avoid all the extreme counterintuitive consequences

that the argument from nominal-notable comparisons is supposed to show. Lemos

argues in a way similar to David Hume: that becoming morally virtuous is simply a

person's best bet for living a good or fulfilling life.15 He claims that if you are

raising a child, then you would want that child to possess the moral virtues. For in

possessing them the child is most likely to lead a happy life because having the

virtues makes us valued members of our communities and reduces our chance of

social ostracism and punishment.16 This means that an agent who has not cultivated

the moral virtues may have been lucky and lived a good and happy life. But given

the poor bet, his way of life has been imprudent. Lemos also points to the

consideration that prudence requires us to develop intellectual virtues and in virtue

of those virtues, we would need to engage in self-deception to mask to oneself the

14 Lemos's wording here is somewhat unfortunate, since the demands of the person who "began his life"

in accordance with an absolute prudence may not seem relevant for the person who has already

committed errors. For the absolute variant of prudence to be interesting, we must suppose that previous

errors in life are no obstacle to starting to conform to the absolute variant of prudence. In terms of virtues,

we must suppose that although an agent has so far not lived a virtuous life, that fact is not a hindrance for

the agent to start living a virtuous life. This assumption seems plausible enough, especially insofar as

virtues are thought to be attained through experience with life.

15 At least this is the interpretation of Hume given by Joel J. Kupperman (2008). Kupperman also appeals

to Paul Ekman's research on "micro-expressions" to argue against the strategy of being only

"apparently" virtuous, like Hume's sensible knave, since people tend to pick up on such insincere

attitudes.

16 This point is also stressed by Hursthouse (1999).

^ Springer

This content downloaded from

159.237.12.142 on Fri, 08 Jan 2021 11:54:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

416 M. S. Sagdahl

knowledge of one's

breed unhappiness i

Another reason tha

vices stand in the wa

class of goods.18 In

such as callousness or those who lack the moral virtues are unable to form true and

faithful interpersonal relationships, such as true friendship and love. These

relationships, it is argued, require a certain level of empathy and sympathy with

other people, and to see people as valuable in non-instrumental ways. The callous

person lacks these sentiments and so is unable to form true relationships. In addition,

they are unable to show their true selves to the world, but must act in secret and so

cannot live sincerely. Living sincerely without hiding and pretence might be seen as a

good in itself, but it might also be connected with inner states. Plato famously

appealed to the "psychic harmony" enjoyed by the morally virtuous person, and

which is unavailable to the vicious person. A related point is that the virtuous person

enjoys the satisfaction and pleasure that comes from knowing that one is doing well

to others and acting virtuously. Lastly, one can appeal to what seems like the pettiness

and impoverishment of a life without moral motivation. In the words of Stephen

Finlay, "a purely self-interested life is [. . .] a life of small and diminishing rewards in

comparison to the rewards of a life of interest in broader and more enduring matters

(pure self-interest has no 'legacy'). Our objective self-interest itself therefore

counsels us not to live an overly (subjectively) self-interested life". (Finlay 2008,

p. 138(f7)) In preferring to watch a rerun of Arrested Development rather than not

harming a hundred people, Norm's life seems petty and impoverished, and not the

sort of meaningful life that we envision the good life to be.

Some of these claims may seem somewhat strong, especially when we keep in

mind that many of them have been put forth by moral philosophers with the aim of

showing that morality has a self-interested basis. It certainly seems that we can

doubt that they are able to secure a perfect coextension between moral and

prudential requirements. The prudential reasons which are appealed to, and which

count in favour of acting morally, exists because immoral behaviour seems to risk a

certain set of significant goods becoming unavailable to the agent. But the agent

who considers acting immorally could object that despite risking these goods, it is

made up for by the hope of acquiring another set of goods, such as various material

goods, which will considerably enhance the agent's quality of life. The reasons

pointed to above are just ordinary prudential reasons which have the potential of

being outweighed by other prudential reasons. Someone skeptical to the significance

of these prudential reasons to be moral could claim that while it may be the case that

I prudentially ought to be the kind of person who has sympathy with others, that

17 It is here reasonable to object that one may not care about whether one's character is good in a moral

way, but it might be replied that this would be an expression of another character trait which is unlikely to

lead to a good life. The theme of self-deception is also pressed by Paul Bloomfield (2008). Bloomfield

connects the self-deception with self-respect and claims that it is impossible for a self-deceiving agent to

have self-respect, since he has a false idea of his self, and couples it with the claim that self-respect is

necessary for a good life.

18 The following list is to a large part taken from Paul Bloomfield (2008).

Springer

This content downloaded from

159.237.12.142 on Fri, 08 Jan 2021 11:54:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Argument from Nominal-Notable Comparisons 417

sympathy is not enough to establish that I prudentially ought

have all the things I want in life by immorally hurting others.

might suffer somewhat from doing that immoral act, but I o

prudential reasons to get everything I want in life.

Although this argument should worry those who aim to pr

grounding for morality, it should not worry the normative p

not concerned with showing that we always have decisive pr

morally, but only with showing that nominal prudential reas

ground a prudential requirement that conflicts with a moral

by notable moral reasons. Once we are dealing with con

reasons, the situation changes and we are no longer faced w

comparison since what is supposed to ground the nominal re

but a slight reason. This is the very limited aim of the norm

virtue of being weaker than those made by moral philosoph

coextension between the two types of requirements, it is m

We are, after all, only seeking a partial and very minimal ov

In fact, there is a very significant tension between the two

coextension would mean that normative pluralism migh

unclear that we would end up with more than one norm

normative pluralist seeks a certain amount of agreement be

prudential standpoints, to a degree that is sufficient to explain

concerning nominal-notable comparisons, but also to le

prudential conflicts in some situations where significant reas

sides. The prudential reasons I have pointed to which cou

morally seem to be up to that task. They are significant enoug

prudential reasons (being a person who feels sympathy for oth

would not be prudentially worth violating those feelings for

but they do not seem able to prevent all conflicts with morality

only prudential reasons of significance.

4 The Dialectical Situation

Does this reply on behalf of normative pluralism represent an adequate way o

meeting the argument from nominal-notable comparisons? That, of course, depend

on the plausibility of a more sophisticated theory of prudence, one that can appeal t

the reasons pointed to above as significant reasons that are always present t

outweigh prudential reasons that are merely nominal. On the face of it, examples

like Norm seem to rely on a simple hedonistic theory of prudence that take

prudence to consist in maximizing pleasure relative to the agent's actual desires in

the present. Other theories of prudence are concerned with achieving "good lives

in a way which encompass more goods than just pleasure which assess the value of

those goods not just according to the agent's present desires, but "timelessly", an

the theories may not even be maximizing in the same way that the simple hedonisti

19 For reasons to doubt a perfect coextension between morality and self-interest, see Scheffler (2008).

Springer

This content downloaded from

159.237.12.142 on Fri, 08 Jan 2021 11:54:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

418 M. S. Sagdahl

theory seems to b

could exist is theref

exist such-and-such

moral requirement

for whatever theor

be indeterminate.

theories of morality

other with respect

normative standpoi

argument from no

equally well for ev

answer to the possi

debate have to sett

disagreement about

Still, the sophistic

reject the possibilit

and seems a reas

comparisons. In ord

option of denying

considerations that

and then try to sho

after all. Let us bri

First, if the one tr

one is, in effect, ad

we need to settle

discussion which g

should be pointed

intuitively relevant

the considerations

have at least a nomi

as being of little sig

with, and possibly

last option is to den

all possible example

insist that there exist cases that have not been considered and where the reasons I

have pointed to (or similar prudential reasons of notable strength) are not present to

outweigh the nominal prudential reason. Whichever option is taken, insofar as

sophisticated theories of prudence are on the table, it will be up to the non-pluralist

to deny the relevancy of these considerations or to provide a convincing example of

a nominal-notable comparison where these considerations could not be present.

But what if someone were to come up with a plausible nominal-notable example

consistent with the type of sophisticated theories of prudence that give a significant

role to things like sympathy and moral virtues in achieving a good life? I think that a

correct conception of prudence does not allow for nominal-notable conflicts

between prudence and morality, but I have not shown conclusively that they are

impossible. But it seems that if some version of the sophisticated theory of prudence

Springer

This content downloaded from

159.237.12.142 on Fri, 08 Jan 2021 11:54:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Argument from Nominal-Notable Comparisons 419

is correct, then moral-prudential conflicts of the nominal-

maybe even downright exceptional, if they exist at all. It se

be conflicts of this kind, they can only arise for agen

motivational structure who (1) do not have the same inter

ordinary human beings, such as an interest in love, r

relationships; (2) who do not suffer from guilt; (3) who do

cultivating moral virtues; and (4) are under exceptional cir

risk of damaging sanctions is absolutely minimal.

If these are the conditions under which a nominal-not

imaginable, the normative pluralist probably should not wo

especially counterintuitive results that the argument

comparisons are supposed to show that normative pluralism

to a very special class of cases involving special agents. For

with normal motivational structures, the theory does n

counterintuitive results, and it can explain why we o

considered, to do what we are morally required to do.

pluralism attractive for reasons like, e.g., recognizing the

between living a good life and upholding one's moral o

arguably, involve various degrees of self-sacrifice), and fo

Henry Sidgwick, that the "rationality of self-regard"

rationality of self-sacrifice", this restricted set of counterin

be seen as very damaging. (Sidgwick 1981)20 In moral p

widespread moral theories, utilitarianism and deontolo

plagued by counterintuitive consequences. Proponents of th

bullet and accept the counterintuitiveness of the theory's c

to certain cases, but still claim that the theory is the most

The same line of argument can be pursued by the normativ

that alternatives to pluralism would yield less counter

Indeed, we do not even seem to know how to commensura

reasons, and so we do not even seem to have much of an a

evaluate. As far as I can see, no good framework for mora

suration has ever been proposed.

Secondly, we might doubt the degree to which we shoul

regarding this special class of cases. To repeat, the argume

when it deals with an unusual type of agents with a special

could very well be the case that because of the unfamiliar n

we are unable to properly imagine or assess them.21 First

least to some extent, and we have at least a certain empath

guilt. Moral values play a significant role in our own lives,

are committed to could possibly contaminate our judgment

20 See also Wallace (2006), and Copp (2007), for similar themes.

21 In a somewhat similar vein, Elster (201 1) argues against the reliability

"outlandish" features. Although he focuses on moral judgments and cases

outwardly 'freakish', one of the problems he mentions is our ability to pr

psychological makeup. See also Parfit' s criticism against Nozick' s imag

1986).

Ö Springer

This content downloaded from

159.237.12.142 on Fri, 08 Jan 2021 11:54:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

420 M. S. Sagdahl

imagine and influe

presence of prudent

though they are sti

be easy to stipulate

it is much harder t

thought would rem

Since even a small r

our imagination of

nominal reason seem

values and rules m

nominal-notable c

shown by an agen

prudential nominal

outrage. The feeling

being a genuine jud

condemnation. Th

obscure the point o

reasonableness of hi

that normative plura

morally ought to do

his show, has done

true of him), he is

severe form of bla

needed to explain th

purpose.

5 Two Alternative Variants of the Argument from Nominal-Notable

Comparisons

We should now consider two other possible variants of the argument from nominal-

notable comparisons. Each of them would to a certain degree change the dialectical

landscape that we have explored.

As we have seen, the typical way to formulate the argument from nominal-

notable comparisons is to proceed from an example where there is a conflict

between a moral requirement supported by very strong moral reasons and a

prudential requirement supported by a very slight prudential reason. One of the two

ways to alter the argument is to appeal to a different sort of case where the strength

of the two types of reasons supporting two different options is considered not in

absolute terms but in relative terms. Consider an example where one would have the

choice of either losing two hundred thousand dollars or else all Falklanders would

die. A proponent of the argument from nominal-notable comparisons could here

appeal to an intuition that one just plain ought to save the Falklanders. Here it seems

that one is prudentially required not to lose the money, for prudential reasons that

can be understood as notable, but which nonetheless pale with respect to notability

in comparison with the moral reasons for saving the Falklanders. So although the

Springer

This content downloaded from

159.237.12.142 on Fri, 08 Jan 2021 11:54:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Argument from Nominal-Notable Comparisons 421

prudential reasons are in some sense considerable, they become

outweighed when compared to the moral reasons. Or so th

would go.

This way of advancing the argument has the advantag

prudential reasons are, at least from a prudential perspect

clearer that the prudential reasons actually support the t

requirement not to do the morally required option. It does no

agent with an alien motivational structure or that we need an

prudence in order for there to actually be a prudential re

morally. So the argument can much more clearly target the p

kinds of examples. On the other hand, however, the advantage

also a disadvantage. What makes the existence of a pruden

more plausible is the presence of prudential reasons that are, f

of the agent, notable. This also makes it much more plau

prudential option is actually an option that his reasons make e

above, that the prudential option would be notable becomes m

reflect on the consequences of not acting prudentially. Losing

dollars may lead the agent into debt or economic uncertainty

seriously reduce his life prospects and life quality (if we stipu

then the argument would no longer have the form which we

The agent is sacrificing himself and the quality of his own l

extent for the lives of others, and it is a sacrifice that is not

agent, by the moral gains. That it can be reasonable and prai

oneself in this manner is not disputed by the pluralist, but it

that this is the only reasonable thing to do - as the argument

of the significant costs to the agent and the quality of his o

conforming to morality, we may also find it reasonable for

prudential option. If one still resists this thought, and insists

the only reasonable thing to do for the agent, then we can a

account for this intuition by explaining it through a quantific

considered. That one would suffer a considerable prudential lo

options does not imply that one is, on the whole, prudentially

loss. I doubt that I could live with the knowledge of being res

of all Falklanders, as that knowledge would seriously affect

and probably more so than being in debt. Even if this would n

case - or be the case for every other agent - facts like these

judgment about what the agent in question ought to do

considering the examples only in the abstract, have a difficult

ourselves in the agent's place and understanding the conse

well-being. So there is room to doubt the usefulness of our in

as well.

The second way of varying the argument is to switch which normative standpoint

is supported by nominal reasons and which is supported by notable reasons. As we

have seen, the typical way to formulate the argument from nominal-notable

comparisons is by appealing to an example where there is a moral requirement

supported by notable prudential reasons, and a prudential requirement supported

â Springer

This content downloaded from

159.237.12.142 on Fri, 08 Jan 2021 11:54:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

422 M. S. Sagdahl

only by nominal pr

imagine a case that

requirement with n

nominal moral reaso

there probably is

However, I will then

may likely be foun

Cases where there

and where there is

seem plausible as a

moves around a lot

morning. However,

legally earn an easy

can assume that y

Although it can ini

prudential requirem

moral requiremen

consequences to you

easily come to doub

promise, given the

very strict moral t

view of morality. F

morality as includi

that morality allow

what would be all

calculus).22 The tho

compromise with r

best morality, but r

would not be a pl

fundamental aims

(Scheffler 2008) Sc

moderate system o

coherent and attrac

impersonal point of

of others and our n

1992) When we appl

conflicts between a

ment, the putative

great personal cos

unreasonable not j

standpoint. This vi

moral rules that ide

appeal to moderac

22 The most prominent

Finlay (2008).

Ô Springer

This content downloaded from

159.237.12.142 on Fri, 08 Jan 2021 11:54:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Argument from Nominal-Notable Comparisons 423

utilitarian theory of morality, and a utilitarian can therefore n

for these kinds of nominal-notable conflicts in the sam

utilitarians, these kinds of conflict seem to be impossible for

my own costs are to be included in the moral calculus, any n

would simply outweigh any benefits to others that are merely

These considerations suggest that unless one defends a ce

demanding morality (in terms of personal costs), nominal-nota

prudential requirements based on notable prudential reasons an

based only on nominal moral reasons are an impossibility. And

on the possibility by defending a very demanding moralit

centred prerogative and where one's own costs do not outweigh

from the moral standpoint, then normative pluralism does n

plausibility by the possibility of these kinds of conflicts. Qu

morality really demands so much of me, then am I really un

morality aside and acting prudentially?23

I believe these considerations explain why opponents of norm

to ignore these kinds of putative nominal-notable conflicts an

the converse type of putative conflict. But as we have see

doubt the possibility of such nominal-notable conflicts as

retain the focus on notable prudential reasons and nominal m

be able to argue for a different sort of nominal-notable confli

not between two requirements, but between a prudential requ

permission. Take again the example with helping your friend

seem prudentially required to earn those million dollars, and m

so, you could also, arguably, be morally permitted to decline t

meet your friend at the time you had promised. That it would

some moral theories, such as typical Kantian theories as well

have moral reasons to look after your own interests which m

moral reasons and not only permit you, but require you t

yourself. If that is right, then these types of nominal-notab

obtain either. But if this is not right, and "agent-centred pr

permissions not to sacrifice your own interests for a slight mor

of nominal-notable conflict does seem possible. Although I ha

the matter, I take it that the latter view of agent-centred prer

implausible. This means that the normative pluralist may after

deal with a particular type of nominal-notable conflict.

How serious is this for the pluralist? My claim is that it is a p

concern the pluralist too much, even if the pluralist would hav

deny the commonly accepted intuition that one just plain ough

dollars rather than keep one's promise. The main reason is

represent a very different type of conflict, where both norm

be satisfied by the same action, and where the nominal mora

23 Witness for instance Finlay (2008), who starts by defending a very demand

the possibility of these kinds of conflicts with self-interest, and then ends up

relationship between morality and self-interest which seems to be a version o

Springer

This content downloaded from

159.237.12.142 on Fri, 08 Jan 2021 11:54:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

424 M. S. Sagdahl

keeping the promis

when deliberating

not give the same v

this, there would b

to do. But, on the o

option, you can d

(quantificationally)

a whole does not dis

agent with a norma

morality's demands

taking the prudent

is all things consid

existence of these k

intuitive results of

Acknowledgments I am g

of Ethics. I would also li

Oslo for making this wo

discuss these issues wit

and Kasper Lippert-Ras

References

Bloomfield, Paul. 2008. Why it's bad to be bad. In Morality and Self-Interest , ed. Paul Bloomfield,

251-271. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bricker, Philip. 1980. Prudence. Journal of Philosophy 77(7): 381-401.

Broome, John. 2013. Rationality Through Reasoning. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Chang, Ruth. 2004. All things considered. Philosophical Perspectives 18(1): 1-22.

Chagn, Ruth. 2004. Putting together morality and well-being. In Practical Conflicts , ed. M. Betzler, and

P. Baumann, 118-158. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chang, Ruth. 1997. Introduction. In Incommensurability, Incomparability, and Practical Reason , ed.

Ruth Chang, 1-34. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Copp, David. 2007. The ring of Gyges: Overridingness and the unity of reasons. In Morality in a Natural

World , ed. David Copp, 249-283. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Copp, David. 2009. Toward a pluralist and teleological theory of normativity. Philosophical Issues 19(1):

21-37.

Dorsey, Dale. 2013. Two dualisms of practical reason. In Oxford Studies in Metaethics 8 , ed. Russ Shafer-

Landau (Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Elster, Jakob. 201 1. How outlandish can imaginary cases be? Journal of Applied Ethics 28(3): 241-258.

Finlay, Stephen. 2008. Too much morality? In Morality and Self-Interest , ed. Paul Bloomfield, 136-154.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gauthier, David. 1986. Morals by agreement. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hursthouse, Rosalind. 1999. On virtue ethics. Oxford: Oxford Univeristy Press.

Kupperman, Joel J. 2008. Classical and sour forms of virtue. In Morality and self-interest , ed. Paul

Bloomfield, 272-286. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lemos, John. 2006. Morality, self-interest, and two kinds of prudential practical rationality. Philosophia

34(1): 85-93.

McLeod, Owen. 2001. Just plain ought. Journal of Ethics 5(4): 269-291.

Parfit, Derek. 2011. On What Matters , vol. I. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Parfit, Derek. 1986. Reasons and Persons. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Regan, Donald. 1997. Value, comparability, and choice. In Incommensurability, Incomparability, and

Practical Reason , ed. Ruth Chang, 129-150. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Springer

This content downloaded from

159.237.12.142 on Fri, 08 Jan 2021 11:54:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Argument from Nominal-Notable Comparisons 425

Scheffler, Samuel. 1992. Human Morality. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Scheffler, Samuel. 2008. Potential congruence. In Morality and Self-Inter

117-135. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sidgwick, Henry. 1981. The Methods of Ethics, 7th ed. Indianapolis: Hacke

Singer, Peter. 2005. Ethics and intuitions. Journal of Ethics 9: 331-352.

Tiffany, Evan. 2007. Deflationary normative pluralism. Canadian Journal o

Wallace, R.Jay. 2006. The Rightness of Acts, Goodness of Lives. In Normat

Wallace, 300-321. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

â Springer

This content downloaded from

159.237.12.142 on Fri, 08 Jan 2021 11:54:27 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Fiscal Directives 2009Document2 pagesFiscal Directives 2009FirstPMFC Sibugay86% (7)

- Niss Theory PDFDocument13 pagesNiss Theory PDFJohn MatthewNo ratings yet

- Legal ReasoningDocument3 pagesLegal ReasoningDumsteyNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 A Practical Ethics ToolkitDocument30 pagesChapter 2 A Practical Ethics Toolkitkristian prestin100% (2)

- Fuller - Morality of LawDocument21 pagesFuller - Morality of LawSaroj KumarNo ratings yet

- Mind Association, Oxford University Press MindDocument32 pagesMind Association, Oxford University Press MindaNo ratings yet

- A Puzzle About Reasons and RationalityDocument27 pagesA Puzzle About Reasons and RationalityGodNo ratings yet

- Petitio Principii - A Bad Form of ReasoningDocument31 pagesPetitio Principii - A Bad Form of Reasoning29milce17No ratings yet

- Mind Association, Oxford University Press MindDocument12 pagesMind Association, Oxford University Press MindJuanpklllllllcamargoNo ratings yet

- Rawlson JusticeDocument16 pagesRawlson JusticeKonrad AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- Väyrynen - Grounding and Normative Explanation (2013)Document24 pagesVäyrynen - Grounding and Normative Explanation (2013)Luigi LucheniNo ratings yet

- DANCY. Ethical Particularism and Morally Relevant PropertiesDocument19 pagesDANCY. Ethical Particularism and Morally Relevant PropertiesGustavo SanrománNo ratings yet

- 10.1007@s10670 019 00142 1Document19 pages10.1007@s10670 019 00142 1GermanCrewNo ratings yet

- Picinali - Reasonable Doubt - Accepted PDFDocument40 pagesPicinali - Reasonable Doubt - Accepted PDFSofia DincuNo ratings yet

- Marraud 2023m Argument ModelsDocument22 pagesMarraud 2023m Argument ModelsFERNANDO MIGUEL LEAL CARRETERONo ratings yet

- Indicative Conditionals StalnakerDocument18 pagesIndicative Conditionals StalnakerSamuel OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Plagiarism in Research: Medicine Health Care and Philosophy July 2014Document22 pagesPlagiarism in Research: Medicine Health Care and Philosophy July 2014Muhammad RizwanNo ratings yet

- 063a12b86b2e9f0510df0960b69277a9Document24 pages063a12b86b2e9f0510df0960b69277a9mghaseghNo ratings yet

- Plagiarism Manuscript Author VersionDocument22 pagesPlagiarism Manuscript Author Versionmehraishita42No ratings yet

- Shapiro - An Argument Against The Social Fact Thesis (And Some Additional Preliminary Steps Towards A New Conception of Legal Positivism) (2008)Document61 pagesShapiro - An Argument Against The Social Fact Thesis (And Some Additional Preliminary Steps Towards A New Conception of Legal Positivism) (2008)Luigi LucheniNo ratings yet

- Logical Pluralism Without The NormativityDocument19 pagesLogical Pluralism Without The NormativityRicardoNo ratings yet

- Thics Are A Vital Component of A Civilized SocietyDocument4 pagesThics Are A Vital Component of A Civilized SocietyDurkhanai ZebNo ratings yet

- Consequential Is MDocument16 pagesConsequential Is MVidhi MehtaNo ratings yet

- Dale Smith - Law, Justice and The Unity of Value (2012)Document18 pagesDale Smith - Law, Justice and The Unity of Value (2012)marting91No ratings yet

- Degrazia 1992Document29 pagesDegrazia 1992alejandroatlovNo ratings yet

- Eskridge JR and Frickey PDFDocument65 pagesEskridge JR and Frickey PDFHannah LINo ratings yet

- The Language and Logic of Law: A Case Study: David N. HaynesDocument17 pagesThe Language and Logic of Law: A Case Study: David N. HaynesMichelle FajardoNo ratings yet

- Comparative Study On Deductive and Inductive Argument: Fec-32 Logical Reasoning Slot-2 1 SemesterDocument13 pagesComparative Study On Deductive and Inductive Argument: Fec-32 Logical Reasoning Slot-2 1 SemesterAryanNo ratings yet

- Nagel - Rawls On JusticeDocument16 pagesNagel - Rawls On JusticeMark van Dorp100% (1)

- Instrumental Rationality Epistemic Rationality and Evidence-GatheringDocument28 pagesInstrumental Rationality Epistemic Rationality and Evidence-GatheringSuresh ShanmughanNo ratings yet

- 3.2 Ethical Monism, Relativism and PluralismDocument3 pages3.2 Ethical Monism, Relativism and PluralismParvadha Varthini. VelmuNo ratings yet

- Rational AgencyDocument23 pagesRational Agencybrevi1No ratings yet

- Presumption Burden of Proof and Lack ofDocument22 pagesPresumption Burden of Proof and Lack ofcjNo ratings yet

- Journal of Philosophy, Inc. The Journal of PhilosophyDocument17 pagesJournal of Philosophy, Inc. The Journal of PhilosophyAnonymous 2Dl0cn7No ratings yet

- ETHICSDocument27 pagesETHICSMoses MirandaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Value PremiseDocument3 pagesIntroduction To Value PremiseVirgiawan Adi KristiantoNo ratings yet

- Why Legal Theory Is Political PhilosophyDocument16 pagesWhy Legal Theory Is Political PhilosophyAntara RanjanNo ratings yet

- Philosophy and LogicDocument24 pagesPhilosophy and Logichauwah202No ratings yet

- Goldman A - Argumentation & Social EpistemologyDocument24 pagesGoldman A - Argumentation & Social EpistemologyLeonardo PortoNo ratings yet

- CriticalDocument9 pagesCriticaldesubie bireNo ratings yet

- Thinking in Three Dimensions Theorizing Rights As A Normative ConceptDocument44 pagesThinking in Three Dimensions Theorizing Rights As A Normative ConceptEsta Em BrancoNo ratings yet

- Murdoch On The Sovereignty of Good 12Document24 pagesMurdoch On The Sovereignty of Good 12Steven SullivanNo ratings yet

- Standards For Paradigm EvaluationDocument9 pagesStandards For Paradigm Evaluationm77799926No ratings yet

- Justification and LegitimationDocument34 pagesJustification and LegitimationRicardoNo ratings yet

- Logical Reasoning: January 2003Document25 pagesLogical Reasoning: January 2003Kevin J. MillsNo ratings yet

- The Value of Cognitive Values PrePrintDocument10 pagesThe Value of Cognitive Values PrePrintBárbaraPintoCorreiaNo ratings yet

- Rawls Paper 2019 PDFDocument24 pagesRawls Paper 2019 PDFJozef DelvauxNo ratings yet

- Restall - Multiple Conclusions PDFDocument18 pagesRestall - Multiple Conclusions PDFHelena LópezNo ratings yet

- Philosophical Issues, 19, Metaethics, 2009: Toward A Pluralist and Teleological Theory of NormativityDocument17 pagesPhilosophical Issues, 19, Metaethics, 2009: Toward A Pluralist and Teleological Theory of NormativityGealaNo ratings yet

- RetrieveDocument32 pagesRetrieveCarlos BalderasNo ratings yet

- Moral Heuristics: Behavioral and Brain Sciences July 2006Document44 pagesMoral Heuristics: Behavioral and Brain Sciences July 2006SamanthaNo ratings yet

- Jules L. Coleman - Beyond The Separability Thesis (2007)Document28 pagesJules L. Coleman - Beyond The Separability Thesis (2007)Eduardo FigueiredoNo ratings yet

- LRV Issues v35n04 BB2 Walker 35 4 FinalDocument20 pagesLRV Issues v35n04 BB2 Walker 35 4 FinalAnonymous sgEtt4No ratings yet

- Reasoning by Analogy: A General TheoryDocument14 pagesReasoning by Analogy: A General TheoryxxxxdadadNo ratings yet

- The Irreducible Complexity of ObjectivityDocument28 pagesThe Irreducible Complexity of ObjectivityAbraham LilenthalNo ratings yet

- 159 Full PDFDocument19 pages159 Full PDFmaleckisaleNo ratings yet

- (J) Greenspan, Patricia (2010) - Imperfect Duties, and Choice. SPPF.Document25 pages(J) Greenspan, Patricia (2010) - Imperfect Duties, and Choice. SPPF.José LiraNo ratings yet

- Context: The Case For A Principled Epistemic Particularism: Daniel AndlerDocument23 pagesContext: The Case For A Principled Epistemic Particularism: Daniel AndlerdandlerNo ratings yet

- Conceptual Ethics pt1 - Plunkett-Burgess2013Document11 pagesConceptual Ethics pt1 - Plunkett-Burgess2013Tim HardwickNo ratings yet

- Nov 16 22 MeasurementDocument22 pagesNov 16 22 MeasurementJared HarrisNo ratings yet

- Chaim Perelman - How Do We Apply Reason To Values?Document7 pagesChaim Perelman - How Do We Apply Reason To Values?JuniorNo ratings yet

- Rights Claimants and Beneficiaries - David LyonsDocument14 pagesRights Claimants and Beneficiaries - David LyonsPedro PabloNo ratings yet

- Natural Law and The Moral Absolute Against Lying - Mark MurphyDocument21 pagesNatural Law and The Moral Absolute Against Lying - Mark MurphyPedro PabloNo ratings yet

- Textos Inconmensurabilidad Ralph McInernyDocument84 pagesTextos Inconmensurabilidad Ralph McInernyPedro PabloNo ratings yet

- Intrinsically Evil Acts and The Moral Viewpoint - Martin RhonheimerDocument40 pagesIntrinsically Evil Acts and The Moral Viewpoint - Martin RhonheimerPedro PabloNo ratings yet

- Ben Amitai2006Document28 pagesBen Amitai2006Pedro PabloNo ratings yet

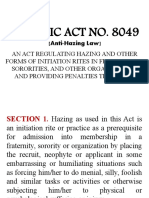

- Republic Act No. 8049: (Anti-Hazing Law)Document12 pagesRepublic Act No. 8049: (Anti-Hazing Law)Mekeni Dogh100% (1)

- DeMott Torts Attack OutlineDocument79 pagesDeMott Torts Attack OutlinefgsdfNo ratings yet

- IRS PUB 519 US TAX GUIDE FOR ALIENS - TAX TREATIES (2018) 68 PagesDocument68 pagesIRS PUB 519 US TAX GUIDE FOR ALIENS - TAX TREATIES (2018) 68 PagesTitle IV-D Man with a planNo ratings yet

- Arrest Procedure in IndiaDocument8 pagesArrest Procedure in IndiaNaman MishraNo ratings yet

- Delineation and Recognition of Ancestral DomainsDocument23 pagesDelineation and Recognition of Ancestral Domainsmitsudayo_No ratings yet

- Villareal Vs RamirezDocument6 pagesVillareal Vs RamirezReth GuevarraNo ratings yet

- E. Partially Valid WarrantDocument10 pagesE. Partially Valid WarrantsiddayaojanusNo ratings yet

- Yujuico Vs QuiambaoDocument1 pageYujuico Vs QuiambaoKatherine Jane Unay100% (1)

- ICC Statement On The Philippines' Notice of Withdrawal: State Participation in Rome Statute System Essential To International Rule of LawDocument16 pagesICC Statement On The Philippines' Notice of Withdrawal: State Participation in Rome Statute System Essential To International Rule of LawJane LumidoNo ratings yet

- Dred Scott PaperDocument28 pagesDred Scott PaperJose PerezNo ratings yet

- Case DigesTDocument10 pagesCase DigesTLea Angelica RiofloridoNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Rules For Writ of Cert.Document13 pagesSupreme Court Rules For Writ of Cert.jamesNo ratings yet

- United States v. Michael W. Critzer, 951 F.2d 306, 11th Cir. (1992)Document3 pagesUnited States v. Michael W. Critzer, 951 F.2d 306, 11th Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- People Vs UbinaDocument21 pagesPeople Vs Ubinavj hernandezNo ratings yet

- Case Digest of People of The Philippines vs. AURELIO LAMAHANG GR 43530 August 3, 1935Document2 pagesCase Digest of People of The Philippines vs. AURELIO LAMAHANG GR 43530 August 3, 1935beingme2100% (3)

- Vital-Gozon vs. Court of Appeals, 212 SCRA 235, G.R. No. 101428 August 5, 1992 ScraDocument31 pagesVital-Gozon vs. Court of Appeals, 212 SCRA 235, G.R. No. 101428 August 5, 1992 ScraKinitDelfinCelestialNo ratings yet

- JOSELANO GUEVARRA v. ATTY. JOSE EMMANUEL EALADocument24 pagesJOSELANO GUEVARRA v. ATTY. JOSE EMMANUEL EALAroy rebosuraNo ratings yet

- Tatad Vs Sandiganbayan (1988) DigestDocument2 pagesTatad Vs Sandiganbayan (1988) DigestArahbellsNo ratings yet

- Wedding Reception ScriptDocument10 pagesWedding Reception ScriptAlexie AlmohallasNo ratings yet

- ContractsDocument16 pagesContractsMark Noel SanteNo ratings yet

- Kamau v. Buss Et Al - Document No. 4Document7 pagesKamau v. Buss Et Al - Document No. 4Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Kho and OngDocument4 pagesKho and OngJesimiel CarlosNo ratings yet

- Lesson 6 A Strange WeddingDocument6 pagesLesson 6 A Strange WeddinglibertyresourcedriveNo ratings yet

- What Makes Us Free? How Does Freedom Shape Our Personality?Document16 pagesWhat Makes Us Free? How Does Freedom Shape Our Personality?Maria Jamilla R. PuaNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Parliamentary PrivilegeDocument30 pagesAn Introduction To Parliamentary PrivilegeRadha CharpotaNo ratings yet

- 20 Wilmon Auto Supply Corp Vs CADocument1 page20 Wilmon Auto Supply Corp Vs CAStephanie GriarNo ratings yet

- Slip-And-Fall Facts by Easter Law FirmDocument3 pagesSlip-And-Fall Facts by Easter Law Firmjoe379No ratings yet

- Philippine Deposit Insurance Corporation (PDIC) LawDocument11 pagesPhilippine Deposit Insurance Corporation (PDIC) LawElmer JuanNo ratings yet