Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Chicago Board of Trade Vs US

Chicago Board of Trade Vs US

Uploaded by

May AnascoOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Chicago Board of Trade Vs US

Chicago Board of Trade Vs US

Uploaded by

May AnascoCopyright:

Available Formats

Chicago Board of Trade v. United States, 246 U.S.

231 (1918)-jet

Facts: Defendant Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) is a commodity market, dealing in spot sales (sales of

grain stored in Chicago and ready for delivery), future sales (grain to be purchased for delivery at a later

time), and “to arrive” orders (grain which is en route to Chicago). CBOT introduced a new “call rule”

which regulated board members buying or selling sales of “to arrive” orders—at the close of the call

session (which at that point was 2:00 p.m Central Time), the price of grain is set and dealers can't sell

grain at any other price. The United States Department of Justice accused CBOT of price-fixing, and in

1913, filed suit against the Board in the United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois.

At trial, CBOT asserted that the rule did not have any unlawful purpose, but rather was set up to curb

certain pre-existing problems and abuses. CBOT claimed that a group of agents were lowering discounts

on commissions to those people buying grain after hours. These agents would wait until after hours, and

then buyers would get cheaper prices. CBOT wanted to curb the power of these monopsony/oligopsony

type of buyers by making prices the same for everyone after hours. Also, the rule shortened the traders’

work hours, for the convenience of its members.

Ultimately, however, the District Court did not issue an opinion. The Justice Department and CBOT

entered into a consent decree under which enjoined them from acting upon the same or from adopting

or acting upon any similar rule.

Issue: WON the Call Rule violate the Anti-Trust Law.

Ruling: No.

Justice Brandeis, writing for a unanimous court, first observed that every trade association and board of

trade imposes some restraint upon the conduct of its members. He explained the essence of the Rule of

Reason: "The true test of legality is whether the restraint imposed is such as merely regulates and

perhaps thereby promotes competition or whether it is such as may suppress or even destroy

competition." Whether or not a rule restrains trade in violation of the Sherman Act thus turns on the

facts and circumstances of each particular case.

He then examined the nature, scope, effect, and history of the rule. He held that the call rule was

ultimately procompetitive in purpose and effect. The scope of the rule was such that it only operated

during certain times of day, and affects only small percentage of the grain market. The rule helped to

create public market for grain and made pricing more transparent. It decreased the market power of

dominant sellers and made sure that prices were set by open competitive bidding. The decree of the

District Court was reversed.

You might also like

- The Hail Mary - Sales Outline (1) (2213)Document164 pagesThe Hail Mary - Sales Outline (1) (2213)Mikel FisherNo ratings yet

- To Uphold A Federal LawDocument4 pagesTo Uphold A Federal LawkrzyreeeshNo ratings yet

- Commerce Clause AnalysisDocument4 pagesCommerce Clause AnalysisJonathan TanakaNo ratings yet

- Mo-957-S2015 KcastDocument32 pagesMo-957-S2015 KcastMay AnascoNo ratings yet

- 2 Material HandlingDocument218 pages2 Material HandlingJon Blac100% (1)

- James DiagramsDocument73 pagesJames DiagramsgabrielNo ratings yet

- COMPLETE Competition MaterialsDocument29 pagesCOMPLETE Competition MaterialsAndrew CrabbeNo ratings yet

- 36.1 Basic Concepts: Chapter 36 - AntitrustDocument11 pages36.1 Basic Concepts: Chapter 36 - AntitrustpfreteNo ratings yet

- Antitrust - Pierce - Fall 2004 - 3Document48 pagesAntitrust - Pierce - Fall 2004 - 3champion_egy325No ratings yet

- Competiton Law NotesDocument34 pagesCompetiton Law Notesaghilan.hb19009No ratings yet

- Key Points in Constitutional LawDocument6 pagesKey Points in Constitutional LawYin Huang / 黄寅100% (2)

- Legal and Ethical BehaviorDocument61 pagesLegal and Ethical BehaviorMicol VillaflorNo ratings yet

- National Labor Relations Board v. C. H. Cross D/B/A Cross Poultry Company, 346 F.2d 165, 4th Cir. (1965)Document3 pagesNational Labor Relations Board v. C. H. Cross D/B/A Cross Poultry Company, 346 F.2d 165, 4th Cir. (1965)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Competition LawDocument8 pagesCompetition Lawchaitra50% (2)

- Competition Law Notes (T Edits)Document67 pagesCompetition Law Notes (T Edits)Yash VermaNo ratings yet

- Competition Law NotesDocument10 pagesCompetition Law NotesSidharth SreekumarNo ratings yet

- Memorandum: Allocation/ de Facto Monopoly Whereby Companies Agree To Steer Clear of EachDocument6 pagesMemorandum: Allocation/ de Facto Monopoly Whereby Companies Agree To Steer Clear of EachKweeng Tayrus FaelnarNo ratings yet

- Big Tech Is Why I Have (Anti) Trust IssuesDocument26 pagesBig Tech Is Why I Have (Anti) Trust IssuesAtish BiswasNo ratings yet

- Economic Due ProcessDocument4 pagesEconomic Due ProcessLeandro BertoncelloNo ratings yet

- Restrictive Rade PracticesDocument8 pagesRestrictive Rade PracticesvkNo ratings yet

- Agriculture Law: RS20241Document6 pagesAgriculture Law: RS20241AgricultureCaseLawNo ratings yet

- Antitrust Law Kesselman Fall 2020Document71 pagesAntitrust Law Kesselman Fall 2020Rhyzan Croomes100% (3)

- National Law Institute UniversityDocument10 pagesNational Law Institute UniversitySanchit AsthanaNo ratings yet

- IO - AntiTrust LawsDocument6 pagesIO - AntiTrust LawsDhriti DhingraNo ratings yet

- Lawrence W. White v. United States, 395 F.2d 5, 1st Cir. (1968)Document8 pagesLawrence W. White v. United States, 395 F.2d 5, 1st Cir. (1968)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Commerce Clause TestsDocument10 pagesCommerce Clause Testsmdaly102483No ratings yet

- United States v. Concentrated Phosphate Export Assn., Inc., 393 U.S. 199 (1968)Document11 pagesUnited States v. Concentrated Phosphate Export Assn., Inc., 393 U.S. 199 (1968)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- The Sherman Antitrust ActDocument5 pagesThe Sherman Antitrust ActKamakshi JoshiNo ratings yet

- Federal and State Statutes - EditedDocument4 pagesFederal and State Statutes - EditedMakau100% (1)

- Old Dearborn Distributing Co. v. Seagram-Distillers Corp., 299 U.S. 183 (1936)Document11 pagesOld Dearborn Distributing Co. v. Seagram-Distillers Corp., 299 U.S. 183 (1936)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- C. Use of The Commerce Clause To Eradicate Racial DiscriminationDocument3 pagesC. Use of The Commerce Clause To Eradicate Racial DiscriminationChristineNo ratings yet

- Questions To Ask Your Professor Before The Exam:: (Judicial Review)Document26 pagesQuestions To Ask Your Professor Before The Exam:: (Judicial Review)Fyouck EmilieNo ratings yet

- Chatper 6..Document10 pagesChatper 6..bucketless.tvNo ratings yet

- Chatper 6.7.9Document49 pagesChatper 6.7.9bucketless.tvNo ratings yet

- Case Summaries Dormant Commerce Clause - OutlineDocument3 pagesCase Summaries Dormant Commerce Clause - OutlineMadhulika VishwanathanNo ratings yet

- Antitrust Kesselman Fall 2020Document101 pagesAntitrust Kesselman Fall 2020Rhyzan CroomesNo ratings yet

- Anti Trus Tpo Licy A NDR Egu Latio NDocument152 pagesAnti Trus Tpo Licy A NDR Egu Latio NUmair Muhammad HaroonNo ratings yet

- United States of America: Before Federal Trade CommissionDocument8 pagesUnited States of America: Before Federal Trade CommissionSkip OlivaNo ratings yet

- Cooley v. Board of WardensDocument2 pagesCooley v. Board of Wardenssunjingyu_661865190No ratings yet

- Legal Analysis of Section 25 Sale of GoDocument2 pagesLegal Analysis of Section 25 Sale of GoSambit PatriNo ratings yet

- T Part 1 - Georgetown 2020Document110 pagesT Part 1 - Georgetown 2020Justin JonesNo ratings yet

- Competition Law Project (Sanjeet Kumar Singh)Document23 pagesCompetition Law Project (Sanjeet Kumar Singh)Sanjeet KumarNo ratings yet

- Consolidated Mfg. Co. v. Federal Trade Commission. Container Mfg. Co. v. Federal Trade Commission. Superior Products v. Federal Trade Commission, 199 F.2d 417, 4th Cir. (1952)Document3 pagesConsolidated Mfg. Co. v. Federal Trade Commission. Container Mfg. Co. v. Federal Trade Commission. Superior Products v. Federal Trade Commission, 199 F.2d 417, 4th Cir. (1952)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Cartel Regulation: A Critical Study With Special Reference To IndiaDocument39 pagesCartel Regulation: A Critical Study With Special Reference To IndiaSri BalajiNo ratings yet

- Competition Commission: Power, Duty and Functions: Dyer's Is The First Known Restrictive Trade Agreement To BeDocument14 pagesCompetition Commission: Power, Duty and Functions: Dyer's Is The First Known Restrictive Trade Agreement To BeNikhilparakhNo ratings yet

- Labor Board v. Reliance Fuel Corp., 371 U.S. 224 (1963)Document3 pagesLabor Board v. Reliance Fuel Corp., 371 U.S. 224 (1963)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Counts. This Guide To The Antitrust Laws Contains A More In-Depth Discussion of CompetitionDocument2 pagesCounts. This Guide To The Antitrust Laws Contains A More In-Depth Discussion of CompetitionAdolfo Cuevas CaminalNo ratings yet

- CH 6 - International Sale of GoodsDocument37 pagesCH 6 - International Sale of GoodsJustin NatanaelNo ratings yet

- Katzenbach v. McClung, 379 U.S. 294 (1964)Document8 pagesKatzenbach v. McClung, 379 U.S. 294 (1964)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- ConcurrenceDocument2 pagesConcurrenceapi-284415671No ratings yet

- The Sherman ActDocument9 pagesThe Sherman ActAnjana HaridasNo ratings yet

- The Regina Corporation, A Corporation of The State of Delaware v. Federal Trade Commission, 322 F.2d 765, 3rd Cir. (1963)Document6 pagesThe Regina Corporation, A Corporation of The State of Delaware v. Federal Trade Commission, 322 F.2d 765, 3rd Cir. (1963)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Con Law OutlineDocument28 pagesCon Law OutlineJosh CauhornNo ratings yet

- LAWS1116 Lecture 7 - Corporations PowerDocument8 pagesLAWS1116 Lecture 7 - Corporations PowerThoughts of a Law StudentNo ratings yet

- UjumDocument23 pagesUjumMarcus King Ataucusi TicllacuriNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDocument18 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Competition Law: Dr. Rajesh Kumar Lecture-1Document12 pagesCompetition Law: Dr. Rajesh Kumar Lecture-1Subodh MalkarNo ratings yet

- Separation of PowersDocument24 pagesSeparation of Powersnkata560% (1)

- Guiyab Compet Bar Reviewer UpdatedDocument35 pagesGuiyab Compet Bar Reviewer UpdatedAbraham GuiyabNo ratings yet

- Bridgeport V GanimDocument3 pagesBridgeport V Ganimggarrett4255No ratings yet

- 031 - ALA Schechter Poultry Corp v. USDocument3 pages031 - ALA Schechter Poultry Corp v. USMiriam Celine MicianoNo ratings yet

- The Constitution: Focus On Application To BusinessDocument33 pagesThe Constitution: Focus On Application To BusinessStanley CkNo ratings yet

- Socrates Vs Sandiganbayan Digest Rule 110Document11 pagesSocrates Vs Sandiganbayan Digest Rule 110May AnascoNo ratings yet

- Mallari Vs CADocument3 pagesMallari Vs CAMay AnascoNo ratings yet

- Demand Letter - LiuDocument1 pageDemand Letter - LiuMay AnascoNo ratings yet

- Monsanto Corp. vs. Spray-Rite Service CorpDocument1 pageMonsanto Corp. vs. Spray-Rite Service CorpMay AnascoNo ratings yet

- Miles Med. Co. v. John D. Park & Sons Co. - 220 U.S. 373, 31 S. Ct. 376 (1911)Document2 pagesMiles Med. Co. v. John D. Park & Sons Co. - 220 U.S. 373, 31 S. Ct. 376 (1911)May AnascoNo ratings yet

- Sta. Maria, Nabunturan, Davao de Oro: February 12, 2013Document1 pageSta. Maria, Nabunturan, Davao de Oro: February 12, 2013May AnascoNo ratings yet

- United States v. Trenton Potteries Co - 273 U.S. 392, 47 S. Ct. 377 (1927)Document2 pagesUnited States v. Trenton Potteries Co - 273 U.S. 392, 47 S. Ct. 377 (1927)May AnascoNo ratings yet

- Rodriguez vs. Judge DigestDocument2 pagesRodriguez vs. Judge DigestMay AnascoNo ratings yet

- Eastern Shipping vs. Iac FactsDocument6 pagesEastern Shipping vs. Iac FactsMay AnascoNo ratings yet

- Diocese of Bacolod vs. COMELEC DigestDocument5 pagesDiocese of Bacolod vs. COMELEC DigestMay AnascoNo ratings yet

- Pre Trial Brief ColladoDocument2 pagesPre Trial Brief ColladoMay AnascoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2, Page 50 ICJ 1971: Termination of Treaties Nimibia CaseDocument1 pageChapter 2, Page 50 ICJ 1971: Termination of Treaties Nimibia CaseMay AnascoNo ratings yet

- Digest Noceda vs. CADocument2 pagesDigest Noceda vs. CAMay AnascoNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Municipal Trial Court of Mati 11 Judicial Region Mati City, Davao OrientalDocument8 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Municipal Trial Court of Mati 11 Judicial Region Mati City, Davao OrientalMay Anasco100% (1)

- Rodriguez vs. Judge DigestDocument2 pagesRodriguez vs. Judge DigestMay AnascoNo ratings yet

- Usufruct CasesDocument24 pagesUsufruct CasesMay AnascoNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Province of Davao Oriental Municipality of Mati Barangay Santa MariaDocument1 pageRepublic of The Philippines Province of Davao Oriental Municipality of Mati Barangay Santa MariaMay AnascoNo ratings yet

- PCL-World Trade Center FlyerDocument4 pagesPCL-World Trade Center FlyerMay AnascoNo ratings yet

- WHO vs. Aquino DigestDocument1 pageWHO vs. Aquino DigestMay Anasco100% (1)

- Ganzales Vs IACDocument2 pagesGanzales Vs IACMay AnascoNo ratings yet

- Teague vs. FernandezDocument1 pageTeague vs. FernandezMay AnascoNo ratings yet

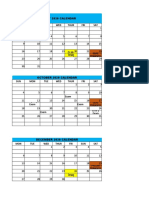

- SUN MON TUE WED Thur FRI SATDocument3 pagesSUN MON TUE WED Thur FRI SATMay AnascoNo ratings yet

- First Division: ARNELITO ADLAWAN, G.R. No. 161916Document30 pagesFirst Division: ARNELITO ADLAWAN, G.R. No. 161916May AnascoNo ratings yet

- Cristobal vs. RonoDocument4 pagesCristobal vs. RonoMay AnascoNo ratings yet

- Partnership List of CasesDocument46 pagesPartnership List of CasesMay AnascoNo ratings yet

- Credit Transaction Cases 2Document23 pagesCredit Transaction Cases 2May AnascoNo ratings yet

- Lu - RR) Ar1: Il /iv".,brk Q-!T ! !L"Document12 pagesLu - RR) Ar1: Il /iv".,brk Q-!T ! !L"May AnascoNo ratings yet

- Cruz Vs Court of AppealsDocument2 pagesCruz Vs Court of AppealsMay AnascoNo ratings yet

- People Vs AsuncionDocument1 pagePeople Vs AsuncionMay AnascoNo ratings yet

- Steamshovel Press Issue 04Document60 pagesSteamshovel Press Issue 04liondog1No ratings yet

- John Champagne - The Ethics of Marginality - A New Approach To Gay Studies (1995)Document267 pagesJohn Champagne - The Ethics of Marginality - A New Approach To Gay Studies (1995)Ildikó HomaNo ratings yet

- Brake Valves: Z279180 Z101197 Z289395 Z102626 (ZRL3518JC02)Document5 pagesBrake Valves: Z279180 Z101197 Z289395 Z102626 (ZRL3518JC02)houssem houssemNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Different Political Beliefs On The Family Relationship of College-StudentsDocument16 pagesThe Impact of Different Political Beliefs On The Family Relationship of College-Studentshue sandovalNo ratings yet

- KunalDocument5 pagesKunalPratik PawarNo ratings yet

- Amyand's HerniaDocument5 pagesAmyand's HerniamonoarulNo ratings yet

- International Primary Curriculum SAM Science Booklet 2012Document44 pagesInternational Primary Curriculum SAM Science Booklet 2012Rere Jasdijf100% (1)

- Solution Manual For Transportation: A Global Supply Chain Perspective, 8th Edition, John J. Coyle, Robert A. Novack, Brian Gibson, Edward J. BardiDocument34 pagesSolution Manual For Transportation: A Global Supply Chain Perspective, 8th Edition, John J. Coyle, Robert A. Novack, Brian Gibson, Edward J. Bardielizabethsantosfawmpbnzjt100% (21)

- Shezan Project Marketing 2009Document16 pagesShezan Project Marketing 2009Humayun100% (3)

- Nod 321Document12 pagesNod 321PabloAyreCondoriNo ratings yet

- Final Defense in PR2Document53 pagesFinal Defense in PR2Friza ann marie NiduazaNo ratings yet

- Katy Perry Lyrics: Play "Trust in Me"Document3 pagesKaty Perry Lyrics: Play "Trust in Me"Alex MunteanNo ratings yet

- Thesis APDocument31 pagesThesis APIvy SorianoNo ratings yet

- Novello's Catalogue of Orchestral MusicDocument212 pagesNovello's Catalogue of Orchestral MusicAnte B.K.No ratings yet

- Lap Trình KeyenceDocument676 pagesLap Trình Keyencetuand1No ratings yet

- Hospital Managing QR Code Web Application Using Django and PythonDocument5 pagesHospital Managing QR Code Web Application Using Django and PythonSihemNo ratings yet

- Appendix 2 Works ListDocument18 pagesAppendix 2 Works ListAnonymous 4BZUZwNo ratings yet

- Atharva Vediya Gopala-Tapani Upanishad KRISHNA PrayersDocument3 pagesAtharva Vediya Gopala-Tapani Upanishad KRISHNA PrayersТимур ГнедовскийNo ratings yet

- Party Facility: Atty. Serrano LTD Lecture - July 12 Jzel EndozoDocument7 pagesParty Facility: Atty. Serrano LTD Lecture - July 12 Jzel EndozoJVLNo ratings yet

- Magnetic Systems Specific Heat$Document13 pagesMagnetic Systems Specific Heat$andres arizaNo ratings yet

- Eyewash and Safety Shower SiDocument3 pagesEyewash and Safety Shower SiAli EsmaeilbeygiNo ratings yet

- Services Provided by Merchant BanksDocument4 pagesServices Provided by Merchant BanksParul PrasadNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneurial Lessons From The Bhagavad GitaDocument13 pagesEntrepreneurial Lessons From The Bhagavad GitaMahima FamousNo ratings yet

- Mesina V Meer PDFDocument3 pagesMesina V Meer PDFColee StiflerNo ratings yet

- Oikonomou Mpegetis S 2014 PHD ThesisDocument352 pagesOikonomou Mpegetis S 2014 PHD ThesisCsillag JanosNo ratings yet

- Mortality RateDocument5 pagesMortality Rateamit kumar dewanganNo ratings yet

- 5e Lesson Plan Format StemDocument7 pages5e Lesson Plan Format Stemapi-251803338No ratings yet

- Amazon Goes To HollywoodDocument27 pagesAmazon Goes To Hollywoodvalentina cahya aldamaNo ratings yet