Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Investigating Expertise in Materials Evaluation

Investigating Expertise in Materials Evaluation

Uploaded by

James LomasCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Defence Manual of SecurityDocument2,389 pagesThe Defence Manual of SecuritySuki100% (6)

- Marketing Strategy Analysis of FabIndiaDocument33 pagesMarketing Strategy Analysis of FabIndiaAman P Jain100% (8)

- American Scholar AnalysisDocument3 pagesAmerican Scholar Analysissdalknranb100% (1)

- FIBA Assist 21Document83 pagesFIBA Assist 21mensrea0No ratings yet

- Walsh, S. (2006)Document10 pagesWalsh, S. (2006)ratu erlindaNo ratings yet

- Textbook EvaluationDocument10 pagesTextbook EvaluationMerbai MajdaNo ratings yet

- Spider GroupDocument20 pagesSpider GroupTasi Alfrace CabalzaNo ratings yet

- Teachers' Pedagogical Systems and Grammar Teaching: A Qualitative StudyDocument30 pagesTeachers' Pedagogical Systems and Grammar Teaching: A Qualitative StudyMehmet Emin MadranNo ratings yet

- Language Classroom Assessment: The Electronic Journal For English As A Second LanguageDocument3 pagesLanguage Classroom Assessment: The Electronic Journal For English As A Second LanguageHamda NasrNo ratings yet

- Classroom Observation and ResearchDocument12 pagesClassroom Observation and ResearchVerito Vera100% (1)

- ELT Journal Volume 61 Issue 2 2007 (Doi 10.1093 - Elt - ccm002) Rao, Z. - Training in Brainstorming and Developing Writing SkillsDocument7 pagesELT Journal Volume 61 Issue 2 2007 (Doi 10.1093 - Elt - ccm002) Rao, Z. - Training in Brainstorming and Developing Writing SkillsTamaraNo ratings yet

- Anisa, Iga, Nafis, Siti - Textbook Kel 9 - Makalah PresentasiDocument9 pagesAnisa, Iga, Nafis, Siti - Textbook Kel 9 - Makalah PresentasiNafisatun HasanahNo ratings yet

- Curriculum TextbooxDocument4 pagesCurriculum TextbooxWidyaNo ratings yet

- Focus On Assessment PDFDocument3 pagesFocus On Assessment PDFridwanaNo ratings yet

- Encouraging Self-Monitoring in Writing by ChineseDocument10 pagesEncouraging Self-Monitoring in Writing by ChineseThu PhạmNo ratings yet

- Group 1 Evaluation of MaterialsDocument24 pagesGroup 1 Evaluation of MaterialsTrang DangNo ratings yet

- Borg 1998bDocument30 pagesBorg 1998bmarija12990100% (1)

- What Is Discourse AnalysisDocument2 pagesWhat Is Discourse Analysisfabriciogerig100% (2)

- RELP - Volume 1 - Issue 2 - Pages 49-57Document9 pagesRELP - Volume 1 - Issue 2 - Pages 49-57arinadorosti4848No ratings yet

- Reflective Thinking Through Teacher Journal WritingDocument16 pagesReflective Thinking Through Teacher Journal WritingJo ZhongNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Teachers' Questions in English Language Classroom: A Case Study in Year 10 of SMK N 1 NunukanDocument8 pagesAn Analysis of Teachers' Questions in English Language Classroom: A Case Study in Year 10 of SMK N 1 Nunukanmichelle guillermoNo ratings yet

- Activity 6 - The Teaching ProfessionDocument5 pagesActivity 6 - The Teaching ProfessionShamalyn M. SendadNo ratings yet

- About Action Research: An Intervention ProgramDocument27 pagesAbout Action Research: An Intervention ProgramSehaNo ratings yet

- Methodology Lecture Notes 1Document35 pagesMethodology Lecture Notes 1Chala KelbessaNo ratings yet

- Carry Out Classroom Research and Action ResearchDocument7 pagesCarry Out Classroom Research and Action Research[SAINTS] StandinReffRoZNo ratings yet

- Uow 195704Document3 pagesUow 195704Mohamad MostafaNo ratings yet

- 56-Krastel Lacorte Action ResearchDocument7 pages56-Krastel Lacorte Action ResearchMartín Felipe Durán López LópezNo ratings yet

- Review of Related Literature Matrix: Practical Research 1: QualitativeDocument3 pagesReview of Related Literature Matrix: Practical Research 1: QualitativeSofhia HugoNo ratings yet

- Pep - Observation Form - April 2012Document3 pagesPep - Observation Form - April 2012Maruthi MaddipatlaNo ratings yet

- David NunanDocument15 pagesDavid NunanTrinh Anh MinhNo ratings yet

- 224 425 1 SMDocument8 pages224 425 1 SMfebbyNo ratings yet

- What Is Lesson Study?: Navigation Search Japanese Elementary Education Professional DevelopmentDocument14 pagesWhat Is Lesson Study?: Navigation Search Japanese Elementary Education Professional DevelopmentSahrum Abdul SaniNo ratings yet

- What Can Be Learned From Student-CentereDocument10 pagesWhat Can Be Learned From Student-CentereJorge Carlos Cortazar SabidoNo ratings yet

- Georgopoulou and Griva-2Document7 pagesGeorgopoulou and Griva-21983gonzoNo ratings yet

- Reflective TeachingDocument9 pagesReflective TeachingMustafaShalabyNo ratings yet

- EN The Implementation of The Genre Based ApDocument10 pagesEN The Implementation of The Genre Based ApKyrei OutaNo ratings yet

- Case Study ExamplesDocument8 pagesCase Study ExamplesKhafifah AlfikaNo ratings yet

- Action Research PaperDocument16 pagesAction Research Papersaumya.iNo ratings yet

- Classroom Research: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Şehnaz ŞahinkarakaşDocument18 pagesClassroom Research: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Şehnaz ŞahinkarakaşĐr MôĦàmễd ȘamirNo ratings yet

- Teaching and Learning Second Language Listening: Metacognition in Action (Review)Document4 pagesTeaching and Learning Second Language Listening: Metacognition in Action (Review)DeborahCordeiroNo ratings yet

- Selection of Materials PDFDocument10 pagesSelection of Materials PDFMURSHIDHNo ratings yet

- Current Approaches and Teaching Methods. Bilingual ProgrammesDocument56 pagesCurrent Approaches and Teaching Methods. Bilingual ProgrammesNoeAgredaSr.No ratings yet

- Course-Module - ELT 3 Week 4Document12 pagesCourse-Module - ELT 3 Week 4DarcknyPusodNo ratings yet

- Kearney 2015 Foreign Language AnnalsDocument24 pagesKearney 2015 Foreign Language AnnalsFernanda Contreras CáceresNo ratings yet

- Text Book Evaluation of SAMT Books in IranDocument20 pagesText Book Evaluation of SAMT Books in IranYasser Amoosi100% (1)

- LP - Lecture Notes For M3Document4 pagesLP - Lecture Notes For M3Thảo Trần Hoàng NgọcNo ratings yet

- Classroom Research Proposal - Stefan RathertDocument13 pagesClassroom Research Proposal - Stefan Rathertakutluay100% (1)

- The Official Website of Educator & Arts Patron Jack C RichardsDocument11 pagesThe Official Website of Educator & Arts Patron Jack C RichardsAiman KhanNo ratings yet

- (JOURNAL) Salma Ladina's JournalDocument13 pages(JOURNAL) Salma Ladina's Journalsalmalad13No ratings yet

- Needs Analysis and Curriculum Development in English For Specific PurposesDocument20 pagesNeeds Analysis and Curriculum Development in English For Specific PurposesSafa TrikiNo ratings yet

- Classroom Research and Action Research: Principles and Practice in EFL ClassroomDocument7 pagesClassroom Research and Action Research: Principles and Practice in EFL ClassroomBien PeraltaNo ratings yet

- Aa11549757 17 157-173Document17 pagesAa11549757 17 157-1735211119No ratings yet

- Abdul Aziz (E1D020002) - SFL-Critical ReviewDocument3 pagesAbdul Aziz (E1D020002) - SFL-Critical Reviewabdul azizNo ratings yet

- UNIT-6 Text Analysis and Lesson PlanningDocument12 pagesUNIT-6 Text Analysis and Lesson PlanningRam SawroopNo ratings yet

- Teacher Talk, Pedagogical Talk and Classroom Activities: Another LookDocument18 pagesTeacher Talk, Pedagogical Talk and Classroom Activities: Another LookPrince QueenoNo ratings yet

- Autonomy of English Language Learners: A Scoping Review of Research and PracticeDocument26 pagesAutonomy of English Language Learners: A Scoping Review of Research and PracticeHashmat TareenNo ratings yet

- Articles ReviewDocument21 pagesArticles ReviewAMALIANo ratings yet

- Curriculum MaterialsDocument79 pagesCurriculum MaterialsAklilu EjajoNo ratings yet

- 3rd Assignment AGG 53Document10 pages3rd Assignment AGG 53Dimitra TsolakidouNo ratings yet

- Simon BORG-A Qualitative StudyDocument31 pagesSimon BORG-A Qualitative StudyYasin AlamdarNo ratings yet

- 2 5395786522274301688 PDFDocument10 pages2 5395786522274301688 PDFdunia duniaNo ratings yet

- From Reading-Writing Research to PracticeFrom EverandFrom Reading-Writing Research to PracticeSophie Briquet-DuhazéNo ratings yet

- Tutorial Letter 102 - 2020 - 1 - B PDFDocument5 pagesTutorial Letter 102 - 2020 - 1 - B PDFThandiwe NakediNo ratings yet

- AUDIT PROGRAM No. 01 PlanningDocument2 pagesAUDIT PROGRAM No. 01 PlanningIvan Alvarez100% (1)

- EntrepreneurDocument15 pagesEntrepreneurarungoel1988No ratings yet

- IB Unit Planner - Spanish 3 - El Siglo de Oro de EspañaDocument4 pagesIB Unit Planner - Spanish 3 - El Siglo de Oro de EspañaColin KryslNo ratings yet

- Cross-Cultural CommunicationDocument2 pagesCross-Cultural CommunicationRehma ManalNo ratings yet

- ARTS7Q1DLP5Document2 pagesARTS7Q1DLP5rudy rex mangubatNo ratings yet

- Week-18 - New Kinder-Dll From New TG 2017Document8 pagesWeek-18 - New Kinder-Dll From New TG 2017Marie banhaonNo ratings yet

- The McKinsey 7S FrameworkDocument17 pagesThe McKinsey 7S FrameworkYogendra RajavatNo ratings yet

- Review Articel Communication 3Document2 pagesReview Articel Communication 3rickyNo ratings yet

- Lesson - Charities - StudentsDocument4 pagesLesson - Charities - StudentsMichaell Stevens Malagon MorenoNo ratings yet

- Is The UN Violating International Labour Standards?Document5 pagesIs The UN Violating International Labour Standards?María CeciliaNo ratings yet

- Media Monopoly: Assessing The Current SituationDocument47 pagesMedia Monopoly: Assessing The Current SituationSharmistha PatelNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - General Principles of TaxationDocument23 pagesChapter 1 - General Principles of TaxationErika MoralesNo ratings yet

- Materi Computer Assisted Language Learning and Teaching 2Document102 pagesMateri Computer Assisted Language Learning and Teaching 2ayu suhestiNo ratings yet

- M.H. de Young Memorial Museum - African Negro Sculpture (1948)Document140 pagesM.H. de Young Memorial Museum - African Negro Sculpture (1948)chyoung100% (1)

- A Brief History of The TechnocracyDocument4 pagesA Brief History of The TechnocracyBeth100% (2)

- Factors Affecting Students Choices in Pursuing Senior High School StrandDocument19 pagesFactors Affecting Students Choices in Pursuing Senior High School StrandRica Joy RiliNo ratings yet

- Interpretation of StatuteDocument19 pagesInterpretation of StatuteRajeev VermaNo ratings yet

- List of Private Schools (Secondary)Document8 pagesList of Private Schools (Secondary)Jezz TagmaNo ratings yet

- Philippine Politics and Governance Chapter 1 and 2 Summative ExamDocument3 pagesPhilippine Politics and Governance Chapter 1 and 2 Summative ExamCristiano Creed100% (5)

- Depok Mansion-RAB Apartment (27.01.2014) A-Rev PDFDocument4 pagesDepok Mansion-RAB Apartment (27.01.2014) A-Rev PDFtelnetcomNo ratings yet

- Kỳ Thi Học Sinh Giỏi Lớp 12 Thành Phố Hà Nội Năm Học: 2011-2012Document6 pagesKỳ Thi Học Sinh Giỏi Lớp 12 Thành Phố Hà Nội Năm Học: 2011-2012Nhật VyNo ratings yet

- Legal Requirements and Managing Diversity: © 2019 Mcgraw-Hill Ryerson Education Limited Schwind 12Th Edition 4-1Document30 pagesLegal Requirements and Managing Diversity: © 2019 Mcgraw-Hill Ryerson Education Limited Schwind 12Th Edition 4-1ManayirNo ratings yet

- L1 PRJ Pro 009Document39 pagesL1 PRJ Pro 009Kevin KamNo ratings yet

- Host Organisation DescriptionDocument1 pageHost Organisation DescriptionYoncé Ivy KnowlesNo ratings yet

- Sev En02 Rules 15988888706j22HDocument8 pagesSev En02 Rules 15988888706j22HSyed Muhammad NabeelNo ratings yet

Investigating Expertise in Materials Evaluation

Investigating Expertise in Materials Evaluation

Uploaded by

James LomasOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Investigating Expertise in Materials Evaluation

Investigating Expertise in Materials Evaluation

Uploaded by

James LomasCopyright:

Available Formats

A step forward: investigating

expertise in materials evaluation

Keith Johnson, Mija Kim, Liu Ya-Fang, Andrea

Nava, Dawn Perkins, Anne Margaret Smith,

Oscar Soler-Canela, and Wang Lu

This article reports on a study investigating the textbook evaluation techniques of

novice and experienced teachers, which was conducted by the Language Teaching

Expertise Research Group (or LATEX ) within Lancaster University’s Department

of Linguistics and English Language. Three E LT teachers were chosen to evaluate

the student and teacher editions of a newly-released E LT textbook using the

technique of concurrent verbalization. The results of the research add to the

growing body of knowledge on expertise, providing insight into the differences

between the teachers with respect to their various evaluation strategies. They also

point to implications for the development of teacher education and training.

Why this study? In the last several years the number of English-language teaching materials

on the market has grown exponentially, addressing a variety of learner

interests, skill levels, and tastes. Among other features, these materials also

vary in their linguistic design, focus, and objectives, making the choice of

a textbook—an integral part of many E LT classrooms—a seemingly

formidable task. Teachers or those training to become English teachers can

look to a number of sources to help them to make more informed decisions

when evaluation is required. For instance, some teacher training courses

offer instruction in materials evaluation. In addition, there are various

references in the literature that address the topic—Tomlinson (2003) and

McGrath (2002) are two of the more recent books that include chapters on

evaluation—but empirical studies revealing what experienced textbook

evaluators actually do are rare.

In this small-scale case study of textbook evaluation conducted by L ATEX at

Lancaster University, the researchers chose to focus on the practices of

teachers at different stages of their careers to discover what effect this

variable might have on their evaluation styles. This was in the hope that the

conclusions drawn from the research would help point to more effective

means of evaluation, which can thereby be utilized by all teachers who are

required to make informed decisions about choosing a coursebook. The

researchers note that the scale of the study—with three participants—

necessarily limits its generalizability but, nevertheless, it is hoped that

E LT Journal Volume 62/2 April 2008; doi:10.1093/elt/ccl021 157

ª The Author 2006. Published by Oxford University Press; all rights reserved.

Advance Access publication July 21, 2006

the research framework may also serve as a model for future large-scale

research projects focusing on materials evaluation procedures.

Methodology This ‘collective case study’ of the textbook evaluation practices of

Why ‘think-aloud’ experienced and novice teachers was designed to facilitate greater

protocols? understanding of effective and efficient techniques of evaluation with the

aim of ‘theorizing’ about these techniques in general (Stake 2000: 437).

When formulating the design of the case study, the researchers decided that

the technique that would best capture the introspective thought processes of

the participants involved was concurrent verbalization. This is a technique

that has been criticized for possibly distorting thinking processes, especially

when the participants are asked to verbalize their thoughts retrospectively,

or in a language other than their first language, or when they are asked to

analyse their thoughts as they report them. None of these demands were

placed on the informants in this study, nor were any time constraints

imposed. Given the virtual impossibility of obtaining any truly complete

records of complex thought processes, some of which will be hidden from

the thinkers themselves, the use of ‘think-aloud’ protocols offers some

insights that other methods would not be able to reveal. Even pauses in the

verbalization can be revealing, indicating phases when intense thinking

is taking place.

The participants In total, three teachers took part in the study (referred to as T1, T2, and

T3); their teaching experience ranged from one year (T1) to 12 years (T3) and

their textbook evaluation training and/or experience ranged from none to

that of the level of curriculum coordinator (see Table 1 for more details).

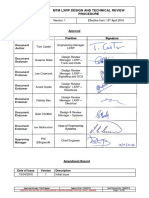

T1 T2 T3

Years teaching 1 year 5 years 12 years

Full- or part-time Part-time Full- and Full-time

part-time

ELT qualifications No Cert T EF L Cert TE SOL , DE LTA , MSc

Previous textbook No No Yes, as part of academic

evaluation training qualifications.

Previous textbook No Yes, selected Yes, served as materials

evaluation experience books for new development coordinator,

table 1

and existing curriculum development

Background and

courses. coordinator, and head of

qualifications of

textbook writing project.

participants

These participants were selected to ensure that they were of the same

nationality and were all working within a similar teaching context. This was

done to lessen the effects of culture as a variable within the study and to aid

the subjects in their ability to associate with the teaching brief presented to

them during the evaluation session. The textbook evaluated was the

Intermediate level Just Right (Harmer 2004), comprising a teacher’s book, a

student’s book, and a mini-grammar booklet containing transcripts of the

listening activities. This coursebook was selected as being suitable for the

teaching environment from which the participants were drawn, although it

158 Keith Johnson et al.

was not in use in the participants’ institution, and therefore all three were

equally unfamiliar with the contents.

Training Another criticism sometimes levelled at think-aloud protocols is that not all

participants are good at thinking aloud, or like doing it, any more than some

teachers like to be observed, or are good at filling in questionnaires. With

this in mind, prior to the start of the individual teachers’ evaluation sessions,

the interlocutor asked each subject to engage in a warm-up activity to enable

them to practise the technique of thinking aloud. The teachers were given

three activities to choose from according to their personal preference: an

anagram, the Tower of Hanoi puzzle, and a partially-completed jigsaw

puzzle; all three chose the jigsaw. The interlocutor then presented the

subjects with a brief containing details of a teaching situation similar to that

within which each was working at the time to help contextualize the

evaluation (see Figure 1 below). The participants were also reminded that

one of the project goals was to gain insight into their thought processes and,

therefore, it was important that they continued to verbalize throughout the

session. The researchers refrained from providing any tips on evaluation.

figure 1

Teaching context

specified in the brief

given to the participants

Analysis The subjects were audio- and video-taped while giving their think-aloud

protocols. The session tapes were then transcribed and the transcripts

distributed to the members of the research team for coding using a

grounded approach. The team also watched the video tapes to explore

coding ideas. Five categories were identified: sequence of evaluation,

teacher preferences, use of terminology, methodological concerns, and

flexibility in usage. Each member of the research group took responsibility

for focusing in depth on one of these categories and analysing the data. The

findings were then discussed by all and recategorized and reanalysed

where necessary. The process continued until the salient features of the data

were brought to light. The rest of this article will discuss two of the key

findings of the study, and the implications of the project.

Findings All the teachers began by looking at the brief provided, and then at the

The sequence of contents pages, and all at some stage looked at all the different components

evaluation of the scheme: the student’s book, the teacher’s book, and the mini-

grammar booklet. However, there was a clear difference among the three

teachers in the route they followed while they were evaluating the textbook.

T1 started at Unit 1, but did not find an activity that she considered to be

suitable for a first lesson (‘a warmer’) and so jumped to Unit 5. This was one

manifestation of her greater concern for classroom logistics than for the

A step forward: investigating expertise in materials evaluation 159

overall evaluation of the textbook. She then opened the teacher’s book and

examined the description of the workbook and the methodological

guidelines. This led her to look for the mini-grammar booklet, by flicking

through the student’s book until she found it (tucked into a pocket in the

back cover). Of the three participants, T1 seemed to be the least familiar with

the commonalities of textbook layout. She then flicked through the mini-

grammar booklet, and kept it to hand while she looked at various aspects of

the student’s book: pronunciation, speaking (including the ‘activity bank’),

functional language, and dictionary work. For each of these areas of

language, she looked at how it was covered in three or four of the units,

using the contents pages to find the appropriate sections. Finally, she

returned to the teacher’s book and looked at the teaching notes in more

detail.

T2 took a more direct approach, though it was not necessarily more time-

efficient. He quickly found all the components of the book, looked at the

front and back covers of the books and then flicked through both the

student’s book and the teacher’s book before returning to the contents

pages. He then looked through every page of the student’s book in turn,

until he reached Unit 13 (of 14). At this stage he referred to the teacher’s book

for Unit 1 and compared it to the student’s book. He repeated this process for

six other units and then returned again to the beginning of the student’s

book and flicked through both books once more, before giving an overall

evaluation of the textbook package.

T3, on the other hand, adopted a more selective approach. He decided early

on to focus on Unit 4, explaining that he expected the textbook to have

‘settled down’ by then. He looked at all the activities in this unit while

referring to the other components of the course. Then he turned to the

teacher’s book and compared it to the student’s book for Unit 4. He then

looked at the methodology notes in the teacher’s book in more detail, before

briefly looking through Unit 8, comparing the student’s book to the

teaching notes.

Compared with T1’s ‘back and forth’ approach, T3’s sequence was very

focused and time-efficient. T1 and T2 also showed some systematicity, but

their evaluations appeared to be more superficial because they made only

very brief comments on different parts of the various units, without

achieving T3’s systematic approach at a deeper level. T3 knew what he was

looking for in evaluating a textbook, and he knew where to find it. This

difference could be vital because the great importance placed on textbooks

in language education (e.g. Cunningsworth 1984; Hutchinson and Torres

1994) means that teachers need to know how to evaluate textbooks

efficiently and effectively.

Teacher preferences Not only did the three teachers follow different sequences in evaluating

the textbook, but they also rated the usefulness of its main features

differently.

T1 appeared to evaluate the textbook on the basis of whether it facilitated the

smooth running of the lesson. This meant, in the first place, that she looked

in the textbook for features that could help her ‘find out where she was’. She

thus appreciated the uncluttered layout of the contents page and the clear

160 Keith Johnson et al.

organization of the units and the teacher’s book. Of the tasks and activities

featured in the textbook she judged negatively those that she believed may

lead to problems in classroom management. For example, she did not like

open-ended discussion tasks as she felt they were not particularly suited

to certain groups of students, who, in her experience, are rather reluctant

to interact with each other in English. She was also sceptical about the

usefulness of split information tasks, which may lead to students ‘cheating’

and resorting to their native language. The ‘procedural’ aspect of the

teaching activities is thus what the novice teacher seemed to be most

concerned with. Hardly any attention was paid to the nature of the language

featured in the textbook.

Rather than focusing exclusively on how the tasks and activities might work

in the classroom, T2 seemed to place more emphasis on what learning

outcomes they might have. For example, he preferred tasks where the

student is involved as a prime actor rather than a passive spectator, as well as

opportunities built into the textbook for ‘revisiting’ language introduced

earlier in the book, as he felt that active involvement and recycling of

language would be likely to lead to more thorough learning. He also showed

some awareness of the linguistic content of the activities. Indeed, even

though he did not always use the appropriate terminology to refer to

linguistic phenomena, he identified and judged positively the focus on the

collocational language of some activities. Throughout the evaluation, T2

seemed to be focused on what he perceived as the more immediate needs of

the students. Hence, topical, up-to-the-minute themes, vocabulary, and

functional language were rated particularly highly as being more likely to

be relevant to the students’ everyday needs.

T3 seemed to comment on a wider range of issues than the other evaluators.

In particular, many of his evaluations concerned the book’s linguistic

rationale. For example, he was particularly impressed with the ‘lexical’ slant

of the textbook, and the occurrence of ‘language in chunks’ in many

activities. T3 was also less categorical and more flexible in expressing what

he liked and did not like about the book. That is, he weighed up pros and

cons of different features of the book, activities, and methodological options,

and took great pains in accommodating other people’s (teachers’ as well

as students’) needs and expectations. He was particularly concerned with

the needs of less experienced teachers and the long-term academic needs

of the students. Also, his evaluations often contained references to other

textbooks he was familiar with.

The general impression is that the more teaching experience an evaluator

has (which obviously also involves at least some experience in textbook

evaluation) the more able he or she is to view a textbook with detachment,

and take account of other users’ needs as well as his or her own. T1 equates

the textbook with a script for lessons and prioritizes the teacher’s need for

‘survival’ when evaluating the book. T2 focuses on the student’s needs,

although it is their immediate needs of functioning in an English-speaking

environment that are of greatest concern. T3 manages to consider how the

textbook fits into a long-term programme of preparation for academic study

and how other teachers might relate to it. Also, whereas T1 seems to be

looking for a textbook packed with activities to cut short the search for

A step forward: investigating expertise in materials evaluation 161

supplementary materials, T2, and especially T3, put a high premium on the

‘jumping off’ opportunities that a textbook offers. What for T1 is a lifeline

may seem like a straightjacket for the more experienced teachers.

The results of this study therefore appear to support the point made by

Skierso (1991) that experienced teachers are better equipped than novices

to adapt teaching materials for use according to their own individual style

within particular teaching environments. Beginning teachers, by virtue

of their inexperience in the classroom, require texts that include

supplementary activities and detailed notes describing how they are to be

used, as well as information regarding the pedagogical objectives that

inform their design (ibid: 433).

The implications of Expertise studies, like this one, are revealing from a theoretical point of

this study view, providing insights of interest to the applied linguist. But arguably of

more importance is their value in providing a research-informed basis for

teacher training. For instance, those in training could be given the task of

participating in similar types of materials evaluation studies, producing

think-aloud protocols of the sessions, the transcripts of which they and their

classmates could then analyse for purposes of determining and possibly

improving their own evaluation styles. This suggestion for using data

gathering methods to train teachers was proposed by Westerman (1991)

following her study of teacher decision-making in order to ‘[promote]

reflection for expert teachers as well as for novices’ (ibid: 303). An

empirically-grounded method of teacher training such as this could go a

long way towards helping student teachers to recognize their own textbook

evaluation styles, as well as to learn more about the use of concurrent

verbalization in research.

The LATEX study also points to the benefits of training teachers to take an

in-depth approach to evaluation whereby the evaluator

[goes] beneath the publisher’s and author’s claims to look at . . . the kind

of language description, underlying assumptions about learning or

values on which the materials are based or . . . whether the materials seem

likely to live up to the claims that are being made for them. (McGrath

2002: 27–8)

This certainly was the style employed by T3 during the study. Following this

systematic method of evaluation seemed to enable him to take a more

holistic stance in his assessment of the textbook and, in so doing, he was able

to consider what lay behind the textbook’s design and aims.

Thus if we wish to train teachers to evaluate textbooks, we will benefit (one

might argue) from knowing something about how experienced evaluators

operate—what procedures they use and what issues they focus attention on.

Given the limited generalizability of the results from this small-scale study,

it is an overly-ambitious goal to develop any definitive statements with

regard to training objectives. But further research into this area seems likely

to reveal aspects of behaviour which would otherwise be ignored by trainers.

It is true that the precise ways in which expertise studies can inform the

trainer need to be thought about with care. Certainly it would be naı̈ve to try

and teach all the characteristics an expert possesses and think that thereby a

162 Keith Johnson et al.

novice will become an expert; research shows, for example, that teaching

novice chess players to improve their chess memories to be as powerful

as those of a grand master may indeed result in improved memories,

but will not in itself transform novices into grand masters. So, training

implications need to be considered carefully. Nevertheless it seems a

worthy and sensible target to aim for a research-informed basis to

training, and it is this target which provides a rationale for research

projects like the one discussed in this paper.

Received March 2006

References Tomlinson, B. (ed.). 2003. Developing Materials for

Cunningsworth, A. 1984. Evaluating and Selecting Language Teaching. London: Continuum.

ELT Teaching Materials. London: Heinemann Westerman, D. A. 1991. ‘Expert and novice teacher

Educational Books. decision making’. Journal of Teacher Education 42/4:

Harmer, J. 2004. Just Right. London: Marshall 229–305.

Cavendish, E LT.

Hutchinson, T. and E. Torres. 1994. ‘The textbook as The authors

agent of change’. E LT Journal 48/4: 315–28. The Language Teaching Expertise research group

McGrath, I. 2002. Materials Evaluation and Design based within the Department of Linguistics and

for Language Teaching. Edinburgh: Edinburgh English Language at Lancaster University conducts

University Press. original research every year into aspects of teaching

Skierso, A. 1991. ‘Textbook selection and evaluation’ expertise. The personnel of this group, made up of

in M. Celce-Murcia (ed.). Teaching English as a Second students and staff, changes yearly. Further details

or Foreign Language (Second Edition). Boston: Heinle about this group can be found at http://

and Heinle. www.ling.lancs.ac.uk/groups/latex/latex.htm.

Stake, R. E. 2000. ‘Case studies’ in N. K. Denzin and

Y. S. Lincoln (eds.). Handbook of Qualitative Research.

Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

A step forward: investigating expertise in materials evaluation 163

You might also like

- The Defence Manual of SecurityDocument2,389 pagesThe Defence Manual of SecuritySuki100% (6)

- Marketing Strategy Analysis of FabIndiaDocument33 pagesMarketing Strategy Analysis of FabIndiaAman P Jain100% (8)

- American Scholar AnalysisDocument3 pagesAmerican Scholar Analysissdalknranb100% (1)

- FIBA Assist 21Document83 pagesFIBA Assist 21mensrea0No ratings yet

- Walsh, S. (2006)Document10 pagesWalsh, S. (2006)ratu erlindaNo ratings yet

- Textbook EvaluationDocument10 pagesTextbook EvaluationMerbai MajdaNo ratings yet

- Spider GroupDocument20 pagesSpider GroupTasi Alfrace CabalzaNo ratings yet

- Teachers' Pedagogical Systems and Grammar Teaching: A Qualitative StudyDocument30 pagesTeachers' Pedagogical Systems and Grammar Teaching: A Qualitative StudyMehmet Emin MadranNo ratings yet

- Language Classroom Assessment: The Electronic Journal For English As A Second LanguageDocument3 pagesLanguage Classroom Assessment: The Electronic Journal For English As A Second LanguageHamda NasrNo ratings yet

- Classroom Observation and ResearchDocument12 pagesClassroom Observation and ResearchVerito Vera100% (1)

- ELT Journal Volume 61 Issue 2 2007 (Doi 10.1093 - Elt - ccm002) Rao, Z. - Training in Brainstorming and Developing Writing SkillsDocument7 pagesELT Journal Volume 61 Issue 2 2007 (Doi 10.1093 - Elt - ccm002) Rao, Z. - Training in Brainstorming and Developing Writing SkillsTamaraNo ratings yet

- Anisa, Iga, Nafis, Siti - Textbook Kel 9 - Makalah PresentasiDocument9 pagesAnisa, Iga, Nafis, Siti - Textbook Kel 9 - Makalah PresentasiNafisatun HasanahNo ratings yet

- Curriculum TextbooxDocument4 pagesCurriculum TextbooxWidyaNo ratings yet

- Focus On Assessment PDFDocument3 pagesFocus On Assessment PDFridwanaNo ratings yet

- Encouraging Self-Monitoring in Writing by ChineseDocument10 pagesEncouraging Self-Monitoring in Writing by ChineseThu PhạmNo ratings yet

- Group 1 Evaluation of MaterialsDocument24 pagesGroup 1 Evaluation of MaterialsTrang DangNo ratings yet

- Borg 1998bDocument30 pagesBorg 1998bmarija12990100% (1)

- What Is Discourse AnalysisDocument2 pagesWhat Is Discourse Analysisfabriciogerig100% (2)

- RELP - Volume 1 - Issue 2 - Pages 49-57Document9 pagesRELP - Volume 1 - Issue 2 - Pages 49-57arinadorosti4848No ratings yet

- Reflective Thinking Through Teacher Journal WritingDocument16 pagesReflective Thinking Through Teacher Journal WritingJo ZhongNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Teachers' Questions in English Language Classroom: A Case Study in Year 10 of SMK N 1 NunukanDocument8 pagesAn Analysis of Teachers' Questions in English Language Classroom: A Case Study in Year 10 of SMK N 1 Nunukanmichelle guillermoNo ratings yet

- Activity 6 - The Teaching ProfessionDocument5 pagesActivity 6 - The Teaching ProfessionShamalyn M. SendadNo ratings yet

- About Action Research: An Intervention ProgramDocument27 pagesAbout Action Research: An Intervention ProgramSehaNo ratings yet

- Methodology Lecture Notes 1Document35 pagesMethodology Lecture Notes 1Chala KelbessaNo ratings yet

- Carry Out Classroom Research and Action ResearchDocument7 pagesCarry Out Classroom Research and Action Research[SAINTS] StandinReffRoZNo ratings yet

- Uow 195704Document3 pagesUow 195704Mohamad MostafaNo ratings yet

- 56-Krastel Lacorte Action ResearchDocument7 pages56-Krastel Lacorte Action ResearchMartín Felipe Durán López LópezNo ratings yet

- Review of Related Literature Matrix: Practical Research 1: QualitativeDocument3 pagesReview of Related Literature Matrix: Practical Research 1: QualitativeSofhia HugoNo ratings yet

- Pep - Observation Form - April 2012Document3 pagesPep - Observation Form - April 2012Maruthi MaddipatlaNo ratings yet

- David NunanDocument15 pagesDavid NunanTrinh Anh MinhNo ratings yet

- 224 425 1 SMDocument8 pages224 425 1 SMfebbyNo ratings yet

- What Is Lesson Study?: Navigation Search Japanese Elementary Education Professional DevelopmentDocument14 pagesWhat Is Lesson Study?: Navigation Search Japanese Elementary Education Professional DevelopmentSahrum Abdul SaniNo ratings yet

- What Can Be Learned From Student-CentereDocument10 pagesWhat Can Be Learned From Student-CentereJorge Carlos Cortazar SabidoNo ratings yet

- Georgopoulou and Griva-2Document7 pagesGeorgopoulou and Griva-21983gonzoNo ratings yet

- Reflective TeachingDocument9 pagesReflective TeachingMustafaShalabyNo ratings yet

- EN The Implementation of The Genre Based ApDocument10 pagesEN The Implementation of The Genre Based ApKyrei OutaNo ratings yet

- Case Study ExamplesDocument8 pagesCase Study ExamplesKhafifah AlfikaNo ratings yet

- Action Research PaperDocument16 pagesAction Research Papersaumya.iNo ratings yet

- Classroom Research: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Şehnaz ŞahinkarakaşDocument18 pagesClassroom Research: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Şehnaz ŞahinkarakaşĐr MôĦàmễd ȘamirNo ratings yet

- Teaching and Learning Second Language Listening: Metacognition in Action (Review)Document4 pagesTeaching and Learning Second Language Listening: Metacognition in Action (Review)DeborahCordeiroNo ratings yet

- Selection of Materials PDFDocument10 pagesSelection of Materials PDFMURSHIDHNo ratings yet

- Current Approaches and Teaching Methods. Bilingual ProgrammesDocument56 pagesCurrent Approaches and Teaching Methods. Bilingual ProgrammesNoeAgredaSr.No ratings yet

- Course-Module - ELT 3 Week 4Document12 pagesCourse-Module - ELT 3 Week 4DarcknyPusodNo ratings yet

- Kearney 2015 Foreign Language AnnalsDocument24 pagesKearney 2015 Foreign Language AnnalsFernanda Contreras CáceresNo ratings yet

- Text Book Evaluation of SAMT Books in IranDocument20 pagesText Book Evaluation of SAMT Books in IranYasser Amoosi100% (1)

- LP - Lecture Notes For M3Document4 pagesLP - Lecture Notes For M3Thảo Trần Hoàng NgọcNo ratings yet

- Classroom Research Proposal - Stefan RathertDocument13 pagesClassroom Research Proposal - Stefan Rathertakutluay100% (1)

- The Official Website of Educator & Arts Patron Jack C RichardsDocument11 pagesThe Official Website of Educator & Arts Patron Jack C RichardsAiman KhanNo ratings yet

- (JOURNAL) Salma Ladina's JournalDocument13 pages(JOURNAL) Salma Ladina's Journalsalmalad13No ratings yet

- Needs Analysis and Curriculum Development in English For Specific PurposesDocument20 pagesNeeds Analysis and Curriculum Development in English For Specific PurposesSafa TrikiNo ratings yet

- Classroom Research and Action Research: Principles and Practice in EFL ClassroomDocument7 pagesClassroom Research and Action Research: Principles and Practice in EFL ClassroomBien PeraltaNo ratings yet

- Aa11549757 17 157-173Document17 pagesAa11549757 17 157-1735211119No ratings yet

- Abdul Aziz (E1D020002) - SFL-Critical ReviewDocument3 pagesAbdul Aziz (E1D020002) - SFL-Critical Reviewabdul azizNo ratings yet

- UNIT-6 Text Analysis and Lesson PlanningDocument12 pagesUNIT-6 Text Analysis and Lesson PlanningRam SawroopNo ratings yet

- Teacher Talk, Pedagogical Talk and Classroom Activities: Another LookDocument18 pagesTeacher Talk, Pedagogical Talk and Classroom Activities: Another LookPrince QueenoNo ratings yet

- Autonomy of English Language Learners: A Scoping Review of Research and PracticeDocument26 pagesAutonomy of English Language Learners: A Scoping Review of Research and PracticeHashmat TareenNo ratings yet

- Articles ReviewDocument21 pagesArticles ReviewAMALIANo ratings yet

- Curriculum MaterialsDocument79 pagesCurriculum MaterialsAklilu EjajoNo ratings yet

- 3rd Assignment AGG 53Document10 pages3rd Assignment AGG 53Dimitra TsolakidouNo ratings yet

- Simon BORG-A Qualitative StudyDocument31 pagesSimon BORG-A Qualitative StudyYasin AlamdarNo ratings yet

- 2 5395786522274301688 PDFDocument10 pages2 5395786522274301688 PDFdunia duniaNo ratings yet

- From Reading-Writing Research to PracticeFrom EverandFrom Reading-Writing Research to PracticeSophie Briquet-DuhazéNo ratings yet

- Tutorial Letter 102 - 2020 - 1 - B PDFDocument5 pagesTutorial Letter 102 - 2020 - 1 - B PDFThandiwe NakediNo ratings yet

- AUDIT PROGRAM No. 01 PlanningDocument2 pagesAUDIT PROGRAM No. 01 PlanningIvan Alvarez100% (1)

- EntrepreneurDocument15 pagesEntrepreneurarungoel1988No ratings yet

- IB Unit Planner - Spanish 3 - El Siglo de Oro de EspañaDocument4 pagesIB Unit Planner - Spanish 3 - El Siglo de Oro de EspañaColin KryslNo ratings yet

- Cross-Cultural CommunicationDocument2 pagesCross-Cultural CommunicationRehma ManalNo ratings yet

- ARTS7Q1DLP5Document2 pagesARTS7Q1DLP5rudy rex mangubatNo ratings yet

- Week-18 - New Kinder-Dll From New TG 2017Document8 pagesWeek-18 - New Kinder-Dll From New TG 2017Marie banhaonNo ratings yet

- The McKinsey 7S FrameworkDocument17 pagesThe McKinsey 7S FrameworkYogendra RajavatNo ratings yet

- Review Articel Communication 3Document2 pagesReview Articel Communication 3rickyNo ratings yet

- Lesson - Charities - StudentsDocument4 pagesLesson - Charities - StudentsMichaell Stevens Malagon MorenoNo ratings yet

- Is The UN Violating International Labour Standards?Document5 pagesIs The UN Violating International Labour Standards?María CeciliaNo ratings yet

- Media Monopoly: Assessing The Current SituationDocument47 pagesMedia Monopoly: Assessing The Current SituationSharmistha PatelNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - General Principles of TaxationDocument23 pagesChapter 1 - General Principles of TaxationErika MoralesNo ratings yet

- Materi Computer Assisted Language Learning and Teaching 2Document102 pagesMateri Computer Assisted Language Learning and Teaching 2ayu suhestiNo ratings yet

- M.H. de Young Memorial Museum - African Negro Sculpture (1948)Document140 pagesM.H. de Young Memorial Museum - African Negro Sculpture (1948)chyoung100% (1)

- A Brief History of The TechnocracyDocument4 pagesA Brief History of The TechnocracyBeth100% (2)

- Factors Affecting Students Choices in Pursuing Senior High School StrandDocument19 pagesFactors Affecting Students Choices in Pursuing Senior High School StrandRica Joy RiliNo ratings yet

- Interpretation of StatuteDocument19 pagesInterpretation of StatuteRajeev VermaNo ratings yet

- List of Private Schools (Secondary)Document8 pagesList of Private Schools (Secondary)Jezz TagmaNo ratings yet

- Philippine Politics and Governance Chapter 1 and 2 Summative ExamDocument3 pagesPhilippine Politics and Governance Chapter 1 and 2 Summative ExamCristiano Creed100% (5)

- Depok Mansion-RAB Apartment (27.01.2014) A-Rev PDFDocument4 pagesDepok Mansion-RAB Apartment (27.01.2014) A-Rev PDFtelnetcomNo ratings yet

- Kỳ Thi Học Sinh Giỏi Lớp 12 Thành Phố Hà Nội Năm Học: 2011-2012Document6 pagesKỳ Thi Học Sinh Giỏi Lớp 12 Thành Phố Hà Nội Năm Học: 2011-2012Nhật VyNo ratings yet

- Legal Requirements and Managing Diversity: © 2019 Mcgraw-Hill Ryerson Education Limited Schwind 12Th Edition 4-1Document30 pagesLegal Requirements and Managing Diversity: © 2019 Mcgraw-Hill Ryerson Education Limited Schwind 12Th Edition 4-1ManayirNo ratings yet

- L1 PRJ Pro 009Document39 pagesL1 PRJ Pro 009Kevin KamNo ratings yet

- Host Organisation DescriptionDocument1 pageHost Organisation DescriptionYoncé Ivy KnowlesNo ratings yet

- Sev En02 Rules 15988888706j22HDocument8 pagesSev En02 Rules 15988888706j22HSyed Muhammad NabeelNo ratings yet