Professional Documents

Culture Documents

From Anatolia To Aceh Ottomans, Turks, and Southeast Asia, Oxford, Oxford University Press

From Anatolia To Aceh Ottomans, Turks, and Southeast Asia, Oxford, Oxford University Press

Uploaded by

Veritrust Academy0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

70 views2 pagesOriginal Title

From Anatolia to Aceh Ottomans, Turks, and Southeast Asia, Oxford, Oxford University Press

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

70 views2 pagesFrom Anatolia To Aceh Ottomans, Turks, and Southeast Asia, Oxford, Oxford University Press

From Anatolia To Aceh Ottomans, Turks, and Southeast Asia, Oxford, Oxford University Press

Uploaded by

Veritrust AcademyCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 2

Revue des Livres/Book Reviews 171

Andrew C. S. Peacock, Annabel Teh Gallop (ed.)

From Anatolia to Aceh: Ottomans, Turks, and Southeast Asia, Oxford, Oxford

University Press (« Proceedings of the British Academy »), 2014, 300 p. ISBN:

9780197265819.

The economical, social, political, religious as well as cultural relations between

Ottomans on the one hand, and maritime Southeast Asia on the other, have a

long and complex history. During the early decades of the sixteenth century,

the connections were strengthened in the commercial domain. Aceh, at that

time was among the most powerful and influential Islamic polities in Southeast

Asia. With the Iberian expansion in the region after the Portuguese conquest

of Malacca, in 1511 and coeval Ottoman arrival to the Red Sea and Persian Gulf,

the balance of power in the India Ocean was reconfigured in favor of the new-

comers. Consequently, two political realms, Anatolia and Aceh, which col-

laborated in the sphere of trade, extended this cooperation to the sphere of

military technology and naval engineering as well as shipbuilding. Since then,

the role and influence of the Ottomans in Southeast Asia expanded into other

spheres which could be witnessed through achievements in the arts and reli-

gion, trade and education. During the period of European colonial expansion

in the nineteenth century, once again Malay states turned to Istanbul for help.

It now appears that these demands for intervention from Southeast Asia may

even have played an important role in the development of the Ottoman policy

of Pan-Islamism, positioning the Ottoman emperor as Caliph and leader of

Muslims worldwide and promoting Muslim solidarity.

Little has been published on the wider context of this relationship. If po-

litical and, although in a lesser quantity, economic aspects of this relation

aroused some interest from the beginning of the twentieth century, a thorough

book encompassing multifarious facets of this relationship had never been

published. A. C. S. Peacock and Annabel Teh Gallop accomplished this task. A

historiographical introduction to the subject and an overview of the research

by Anthony Reed, one of the pioneers of the subject, are followed by three

well-organized parts.

In the first part, The Political and Economic Relationship from the Sixteenth to

the Nineteenth Century, four articles cover a variety of subjects in an unequal

manner. Jorge Alves’ discusses the role played by Jewish and New Christian

Networks in Aceh-Ottoman relations during the 1550s-1570s. Andrew Peacock’s

survey of seventeenth-century economic relations, which deals with both

Ottoman imports from Southeast Asia (spices) and exports (carpets, horses,

coffee) to that region, as well as a survey of the presence of Ottoman visitors and

expatriates. Kathirithamby-Wells concentrates on the role played by Hadhrami

© koninklijke brill nv, leiden, ���7 | doi 10.1163/19585705-12341355

172 Revue des Livres/Book Reviews

merchants through their involvement in Sufi orders, khutba networks, and

pilgrim traffic, or as diplomatic emissaries and claimants of Ottoman protec-

tion against British and Dutch colonial authorities; as well as Isaac Donoso’s

study of Ottomans contacts with the Sulu and Maguindanao Sultanates of the

Southern Philippines.

The second part, namely Interactions in the Colonial Era, covers an in-

depth study of William Clarence-Smith’s on the nature of relations between

the Philippines, the new American overlords and Ottoman emissaries active

there between 1898 and 1919. In two separate and well-informed articles, İsmail

Hakkı Kadı and İsmail Hakkı Göksoy elaborate on the deployment of Ottoman

pan-islamic policies by concentrating on several unpublished sources covering

Southeast Asian rulers appeals to Ottoman protection. The chapters by Amrita

Malhi and Chiara Formichi, on British Malaya and the Netherlands East Indies

respectively, bring into the twentieth century the study of Southeast Asian

interest in the Ottoman Empire as well as that of the contemporary Turkish

Republic.

In the final part, Cultural and Intellectual Influences, Vladimir Braginsky

analyses Turkic influences in the traditional Malay literature, especially that

of Ibrahim al-Kurani (1616-1690). Oman Fathurahman elaborates on a lesser

known figure but an important cultural broker, i.e. Baba Dawud al-Jawi al-

Rumi. In the last and richly illustrated chapter, Ali Akbar examines copies of

Ottoman Qurans in Southeast Asia. This well-prepared and thorough volume

will doubtlessly provide a stimulating reading for researchers working on Asian

diplomacy, cultural transfers, colonialism, connected history, global history art

history in Early Modern as well as Modern period.

Güneş Işiksel

Studia Islamica 112 (2017) 149-174

You might also like

- The Bible Study NT - 4.0 DigitalDocument219 pagesThe Bible Study NT - 4.0 Digitalgoldenhearts100% (3)

- The History of The Somali Peninsula: From The Ancient Times To The Medieval Muslim PeriodDocument33 pagesThe History of The Somali Peninsula: From The Ancient Times To The Medieval Muslim PeriodDr. Abdurahman M. Abdullahi ( baadiyow)100% (2)

- Introduction Business Law IcmDocument49 pagesIntroduction Business Law IcmJoram Wambugu100% (6)

- Ali Uzay Peker - Western Influences On The Ottoman Empire and Occidentalism in The Architecture of IstanbulDocument26 pagesAli Uzay Peker - Western Influences On The Ottoman Empire and Occidentalism in The Architecture of IstanbulpetrospetrouNo ratings yet

- Ottoman AcehDocument19 pagesOttoman AcehAsep Wahyu HidayatNo ratings yet

- Yelda Demirag From Ottomanism To TurkismDocument20 pagesYelda Demirag From Ottomanism To TurkismrodmariamNo ratings yet

- Ottoman Dress and Design in the West: A Visual History of Cultural ExchangeFrom EverandOttoman Dress and Design in the West: A Visual History of Cultural ExchangeRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Makdisi Ottoman OrientalismDocument29 pagesMakdisi Ottoman OrientalismAbdellatif ZibeirNo ratings yet

- The Ottoman's Empire Police System The Ottoman Empire Law Enforcement SystemDocument21 pagesThe Ottoman's Empire Police System The Ottoman Empire Law Enforcement SystemWal KerNo ratings yet

- Emrence, Late Ott Empire (2008)Document23 pagesEmrence, Late Ott Empire (2008)Abdellatif ZibeirNo ratings yet

- Mediating - Boundaries - Mediterranean - Go - Betweens Emrah GurkanDocument22 pagesMediating - Boundaries - Mediterranean - Go - Betweens Emrah GurkanAmanda SantosNo ratings yet

- The Evolution of The Ottoman Seaborne Empire in The Age of The Oceanic Discoveries, 1453-1525Document29 pagesThe Evolution of The Ottoman Seaborne Empire in The Age of The Oceanic Discoveries, 1453-1525Leonardo Vieira100% (1)

- Writing History at the Ottoman Court: Editing the Past, Fashioning the FutureFrom EverandWriting History at the Ottoman Court: Editing the Past, Fashioning the FutureNo ratings yet

- The Renaissance Bazaar - From The Silk Road To MichelangeloDocument33 pagesThe Renaissance Bazaar - From The Silk Road To MichelangeloSamira BullyNo ratings yet

- BiASES in STUDYiNG OTTOMAN HiSTORY PDFDocument3 pagesBiASES in STUDYiNG OTTOMAN HiSTORY PDFMu'adh AbdinNo ratings yet

- 1918 Turks of Central Asia in History and at The Present Day by Czaplicka S PDFDocument246 pages1918 Turks of Central Asia in History and at The Present Day by Czaplicka S PDFBhikkhu KesaraNo ratings yet

- Elizabethan OrientalismDocument20 pagesElizabethan Orientalismanisorange100% (1)

- CROATIAN NOBLE REFUGEES IN LATE 15th AND 16th CENTURY BANAT - Schmitt - The - Ottoman - Conquest - of - The - BalkansRESEE - 003Document171 pagesCROATIAN NOBLE REFUGEES IN LATE 15th AND 16th CENTURY BANAT - Schmitt - The - Ottoman - Conquest - of - The - BalkansRESEE - 003HenohNo ratings yet

- Broad Historical Context The Rise of The Ottoman Empire and The Formation of Muslim Communities in The Balkans As An Integral Part of The Ottomanization of The RegionDocument27 pagesBroad Historical Context The Rise of The Ottoman Empire and The Formation of Muslim Communities in The Balkans As An Integral Part of The Ottomanization of The Regionali0719ukNo ratings yet

- 7 NafiDocument20 pages7 NafiAbdellatif El BekkariNo ratings yet

- MKL - DD-Paco - The Ottoman Empire in Early Modern Austrian History PDFDocument17 pagesMKL - DD-Paco - The Ottoman Empire in Early Modern Austrian History PDFyesevihanNo ratings yet

- Suraiya Faroqhi-Approaching Ottoman History - An Introduction To The Sources (2000)Document273 pagesSuraiya Faroqhi-Approaching Ottoman History - An Introduction To The Sources (2000)Denis Ljuljanovic100% (3)

- IJHSS - Friends, Foes, Allies Ottoman British Relations in The Long Eighteenth CenturyDocument8 pagesIJHSS - Friends, Foes, Allies Ottoman British Relations in The Long Eighteenth Centuryiaset123No ratings yet

- Ottoman Historiography and The SeventeenDocument25 pagesOttoman Historiography and The SeventeenEmri MbiemriNo ratings yet

- Makdisi, Ussama - Ottoman Orientalism PDFDocument27 pagesMakdisi, Ussama - Ottoman Orientalism PDFCüneyt YüceNo ratings yet

- The Image of The Ottomans in Hungarian Historiography (AOASH 61, 1-2, 2008, 15-26)Document12 pagesThe Image of The Ottomans in Hungarian Historiography (AOASH 61, 1-2, 2008, 15-26)hadrian_imperatorNo ratings yet

- The Mongol Empire in World History: The State of The FieldDocument34 pagesThe Mongol Empire in World History: The State of The FieldEdoaru DekanNo ratings yet

- Modernism in The Middle East and Arab WorldDocument8 pagesModernism in The Middle East and Arab WorldmarwaNo ratings yet

- Linda T. Darling DamascusDocument26 pagesLinda T. Darling DamascusFatih YucelNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 102.90.47.174 On Sat, 13 May 2023 23:53:20 +00:00Document16 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 102.90.47.174 On Sat, 13 May 2023 23:53:20 +00:00Adeogun JoshuaNo ratings yet

- 02 01 Political History I-Summary SheetDocument12 pages02 01 Political History I-Summary SheetNour BenzNo ratings yet

- Lịch sử giáo hội Công giáo IndonesiaDocument9 pagesLịch sử giáo hội Công giáo IndonesiaThi NguyenNo ratings yet

- Some Information About The History of The Formation of Historical-Geographical Views About Central Asia in EuropeDocument4 pagesSome Information About The History of The Formation of Historical-Geographical Views About Central Asia in EuroperesearchparksNo ratings yet

- Creating East and West: Renaissance Humanists and the Ottoman TurksFrom EverandCreating East and West: Renaissance Humanists and the Ottoman TurksRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (4)

- An Economic and Social History of The OtDocument3 pagesAn Economic and Social History of The OtΑντώνιος ΜαράτοςNo ratings yet

- Ottoman Empire Essay ThesisDocument4 pagesOttoman Empire Essay Thesisirywesief100% (2)

- Middle Eastern Studies and IslamDocument28 pagesMiddle Eastern Studies and IslamAkh Bahrul Dzu HimmahNo ratings yet

- The Ottoman Empire and Europe: Chapter 23Document26 pagesThe Ottoman Empire and Europe: Chapter 23Fatih SimsekNo ratings yet

- Gábor Ágoston, Ottoman Expansion and Military Power 1300-1453Document21 pagesGábor Ágoston, Ottoman Expansion and Military Power 1300-1453jenismoNo ratings yet

- The Rise and Fall of Khoqand 1709-1876 Central Asia in The Global AgeDocument289 pagesThe Rise and Fall of Khoqand 1709-1876 Central Asia in The Global Age220304055No ratings yet

- ArmatoloiDocument266 pagesArmatoloiAnton Cusa100% (1)

- Islamic Alexanders in Southeast AsiaDocument38 pagesIslamic Alexanders in Southeast AsiacelynNo ratings yet

- Agoston, Flexible EmpireDocument10 pagesAgoston, Flexible EmpireeksenNo ratings yet

- HIST106 Lecture Notes PDFDocument61 pagesHIST106 Lecture Notes PDFibrahim inceogluNo ratings yet

- Ottoman Empire Decline ThesisDocument8 pagesOttoman Empire Decline Thesisheatherharveyanchorage100% (2)

- Yeni Metin BelgesiDocument1 pageYeni Metin Belgesiegegurses631No ratings yet

- Lewis Ch2 Silver, Inflation and EconomyDocument19 pagesLewis Ch2 Silver, Inflation and EconomySeungjune MinNo ratings yet

- (2016) KIPROVSKA, M. Ferocious Invasion or Smooth IncorporationDocument29 pages(2016) KIPROVSKA, M. Ferocious Invasion or Smooth IncorporationMariya KiprovskaNo ratings yet

- The Ottoman Scramble for Africa: Empire and Diplomacy in the Sahara and the HijazFrom EverandThe Ottoman Scramble for Africa: Empire and Diplomacy in the Sahara and the HijazRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- History ResearchDocument4 pagesHistory ResearchjfrNo ratings yet

- Eastern & Western Cultures in Cantemir - InalcikDocument3 pagesEastern & Western Cultures in Cantemir - InalcikOkan Murat ÖztürkNo ratings yet

- Ottoman Diplomacy PDFDocument13 pagesOttoman Diplomacy PDFSiraj KuvakkattayilNo ratings yet

- History of The Ottoman Empire and Modern TurkeyDocument367 pagesHistory of The Ottoman Empire and Modern TurkeyMladen Veljkovich100% (3)

- Historian Volume 72 Issue 1 2010 Dionysios Stathakopoulos - Constantinople - Capital of Byzantium - by Jonathan HarrisDocument101 pagesHistorian Volume 72 Issue 1 2010 Dionysios Stathakopoulos - Constantinople - Capital of Byzantium - by Jonathan HarrisBalázs DócziNo ratings yet

- Bilkent University, Ankara: Turkey and Europe:A Historical PerspectiveDocument8 pagesBilkent University, Ankara: Turkey and Europe:A Historical Perspectiveokankaya_35No ratings yet

- In Alc I K Turkey and EuropeDocument27 pagesIn Alc I K Turkey and EuropemahoranNo ratings yet

- Ottoman EmpireDocument8 pagesOttoman EmpireESTHEFFANY RODRIGUEZNo ratings yet

- Geopolitics TriumphDocument17 pagesGeopolitics TriumphAriel RadovanNo ratings yet

- Thomas of Spalato & MongolsDocument28 pagesThomas of Spalato & MongolsstephenghawNo ratings yet

- Rape and AIDS in Prison: On A Collision Course To A New Death Penalty, Suffolk Law Review (1997)Document33 pagesRape and AIDS in Prison: On A Collision Course To A New Death Penalty, Suffolk Law Review (1997)Richard VetsteinNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Seventh CircuitDocument10 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Seventh CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Commercial Dispatch Eedition 9-23-20Document16 pagesCommercial Dispatch Eedition 9-23-20The DispatchNo ratings yet

- Columbus United Methodist Church: in This IssueDocument11 pagesColumbus United Methodist Church: in This IssueColumbusUMCNo ratings yet

- Russia's Gravediggers by Alfred RosenbergDocument41 pagesRussia's Gravediggers by Alfred RosenbergMichael67% (3)

- First Division: PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. ERNIE INCIONG y ORENSE, Accused-AppellantDocument6 pagesFirst Division: PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. ERNIE INCIONG y ORENSE, Accused-AppellantQuazhar PandiNo ratings yet

- Outline Corp LawDocument22 pagesOutline Corp LawFLOYD MORPHEUSNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 107225 Archilles Manufacturing V NLRCDocument3 pagesG.R. No. 107225 Archilles Manufacturing V NLRCRuel ReyesNo ratings yet

- Civil Code 1 - Paras - PersonsDocument1,074 pagesCivil Code 1 - Paras - PersonsjennyMB100% (1)

- Plaintiff: Answer With Affirmative DefensesDocument5 pagesPlaintiff: Answer With Affirmative DefensesReia RuecoNo ratings yet

- Problem Question GuidanceDocument2 pagesProblem Question GuidanceAbdul sami bhuttoNo ratings yet

- DUMLAO, Cheyenne Hope (Assignment #1 in Legal Profession)Document13 pagesDUMLAO, Cheyenne Hope (Assignment #1 in Legal Profession)Chey DumlaoNo ratings yet

- Safeguarding and Managing Risk Across The Lifecourse CompleteDocument8 pagesSafeguarding and Managing Risk Across The Lifecourse CompleteSouvik HaldarNo ratings yet

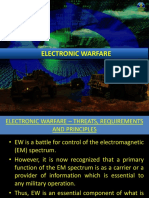

- Ew 1Document91 pagesEw 1saven jayamanna100% (2)

- Civil Procedure NotesDocument22 pagesCivil Procedure Notesjorg100% (2)

- 11e AR ConfirmationsDocument12 pages11e AR ConfirmationsJL Huang0% (1)

- Employment Eligibility Verification: U.S. Citizenship and Immigration ServicesDocument3 pagesEmployment Eligibility Verification: U.S. Citizenship and Immigration ServicesBlanca AgueroNo ratings yet

- Civ Cases Sept 11Document44 pagesCiv Cases Sept 11marites ongtengcoNo ratings yet

- ESA INGLÊS - Ex. - Present Continuous II-1Document20 pagesESA INGLÊS - Ex. - Present Continuous II-1eumilitar341No ratings yet

- United States v. Gasca, 10th Cir. (2007)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Gasca, 10th Cir. (2007)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Postpartum Car1Document11 pagesPostpartum Car1Claire Alvarez OngchuaNo ratings yet

- Role of Youth in Indian SocietyDocument4 pagesRole of Youth in Indian SocietyYokesh SamannanNo ratings yet

- Letter of IndemnityDocument2 pagesLetter of IndemnityAnkit MauryaNo ratings yet

- Women Role in The SocietyDocument1 pageWomen Role in The SocietyProf. Liaqat Ali Mohsin100% (1)

- IndictmentDocument4 pagesIndictmentHayden SparksNo ratings yet

- IEO Class 4Document5 pagesIEO Class 4Kusum PoddarNo ratings yet

- RPD 5-15-24Document4 pagesRPD 5-15-24PostBulltinDocsNo ratings yet

- Kingdoms Live Cheat Sheet v2.5Document20 pagesKingdoms Live Cheat Sheet v2.5Jeje Cuba DuluNo ratings yet