Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Greek Corpus of Aphasic Discourse: Collection, Transcription, and Annotation Specifications

A Greek Corpus of Aphasic Discourse: Collection, Transcription, and Annotation Specifications

Uploaded by

Athanasios N. KarasimosOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A Greek Corpus of Aphasic Discourse: Collection, Transcription, and Annotation Specifications

A Greek Corpus of Aphasic Discourse: Collection, Transcription, and Annotation Specifications

Uploaded by

Athanasios N. KarasimosCopyright:

Available Formats

A Greek Corpus of Aphasic Discourse: Collection, Transcription, and

Annotation Specifications

Spyridoula Varlokosta1, Spyridoula Stamouli1,2, Athanassios Karasimos1,3, Georgios

Markopoulos1, Maria Kakavoulia4, Michaela Nerantzini1,5, Aikaterini Pantoula1, Valantis

Fyndanis1,6, Alexandra Economou1, Athanassios Protopapas1

1

National and Kapodistrian University of Athens

2

Institute for Language and Speech Processing / “Athena” Research Center

3

Academy of Athens

4

Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences

5

Northwestern University

6

University of Oslo

Address: University of Athens, Philology/Linguistics, Panepistimioupoli Zografou, Athens, 15784 Greece.

E-mail: svarlokosta@phil.uoa.gr, pstam@ilsp.gr, akarasimos@academyofathens.gr, gmarkop@phil.uoa.gr,

markak@panteion.gr, nmixaela@gmail.com, a.pantoula@ed.ac.uk, valantis.fyndanis@iln.uio.no,

aoikono@psych.uoa.gr, aprotopapas@phs.uoa.gr

Abstract

In this paper, the process of designing an annotated Greek Corpus of Aphasic Discourse (GREECAD) is presented. Given that

resources of this kind are quite limited, a major aim of GREECAD was to provide a set of specifications which could serve as a

methodological basis for the development of other relevant corpora and, therefore, to contribute to the future research in this area.

GREECAD was developed with the following requirements: a) to include a representative sample of Greek as spoken by individuals

with aphasia, b) to document speech samples with rich metadata, which include demographic information, as well as detailed

information on the patients’ medical record and neuropsychological evaluation, c) to provide annotated speech samples, which encode

information at the micro-linguistic (words, POS, grammatical errors, clause types, etc.) and discourse level (narrative structure

elements, main events, evaluation devices, etc.). In terms of the design of GREECAD, the basic requirements regarding data collection,

metadata, transcription, and annotation procedures were set. The discourse samples were transcribed and annotated with the ELAN

tool. To ensure accurate and consistent annotation, a Transcription and Annotation Guide was compiled, which includes detailed

guidelines regarding all aspects of the transcription and annotation procedure.

Keywords: aphasia, aphasic discourse, annotated corpus

40 years have emphasized the clinical importance of the

1. Introduction study of discourse production (Berko-Gleason et al., 1980;

Aphasia is defined as a language disorder following a focal Lemme, Hedberg & Bottenberg, 1983; Nicholas &

damage to the left cerebral hemisphere caused either by a Brookshire, 1993; Olness, 2006; Olness & Ulatowska,

cerebral vascular accident (CVA), a traumatic brain injury 2011; Saffran, Berndt & Schwartz, 1989; Stark, 2010;

(TBI), an infection, such as encephalitis, or as the result of Ulatowska, North & Macaluso-Haynes, 1981, Ulatowska

the existence or the removal of a brain tumor (De Roo, et al., 1983; Vermeulen, Bastiaanse & van Wageningen,

1999: 1; Mesulam, 2000: 296). Aphasia is typically 1989, see Armstrong, 2000 and Wright, 2011 for an

restricted to language impairments in the absence of any overview of the literature). Since people with aphasia

other general cognitive impairment or dementia (Obler & experience particular difficulties in their everyday

Gjerlow, 1999: 38). Deficits in aphasia can potentially communication, the study of their abilities at the discourse

affect speech production and comprehension in both oral level is considered as a natural and objective method for

and written language forms, and all linguistic levels (i.e., assessing the communicative effectiveness of these

phonological, morphological, syntactic, and semantic individuals in their everyday life. More specifically, the

disorders), to varying degrees depending on the site and the study of discourse production can contribute to the

severity of the brain injury (Harley, 2001: 23); from mild, diagnosis of the type of aphasia, to a more accurate

to moderate and severe disorders. identification of the communication impairments of

Although in the aphasiological literature many different patients, to the design of a more effective treatment as well

types of aphasia have been described, the most widespread as to the evaluation of patients’ response to treatment.

classification identifies two basic categories: non-fluent Despite the fact that there is a large body of literature on the

aphasia or Broca’s aphasia and fluent aphasia or characteristics of aphasic discourse in many languages,

Wernicke’s aphasia, each one of which has been associated which includes studies following different methodological

with different neurological characteristics, as for the locus approaches, theoretical frameworks, and analytical

and the extent of the lesion, and different linguistic perspectives, there is a considerable lack of available

characteristics. resources to allow the systematic study of aphasic

Studies on speakers with aphasia conducted over the past discourse in a comparable and replicable way across

languages. The available corpora of aphasic discourse etc.), and different elicitation techniques (McNeil et al.,

productions -constructed with the use of corpus linguistic 2007; Menn, Ramsberger & Helm-Estabrooks, 1994,

techniques and providing systematic methods for the Nicholas & Brookshire, 1995; Ulatowska et al., 1983)

transcription, annotation, and analysis- are the Corpus of providing different degrees and types of support to the

Dutch Aphasic Speech (CoDAS, Westerhout & Monachesi, participants. The protocol includes the following tasks:

2006), the Cambridge Cookie-Theft Corpus (Williams et Task 1: unaided production of a personal narrative (“stroke

al., 2010), and the AphasiaBank (MacWhinney et al., 2011, story”)

2012). Each one of them has contributed from a different Task 2: novel story production based on a 6-picture series

perspective to the process of enriching the existing (“the party”)

methods and data for the study of aphasic discourse, and, Task 3: novel story retelling, aided by a 5-picture series

consequently, to the advancement of research in this area. (“the ring”)

The Greek Corpus of Aphasic Discourse (GREECAD) is Task 4: familiar story retelling (“hare and tortoise” Aesop’s

the outcome of a research action under the large scale fable)

multidisciplinary project “THALES-Levels of impairment

in Greek aphasia: relationship with processing deficits, 3. Participants

brain region, and therapeutic implications”. The aim of this The GREECAD corpus contains spoken discourse samples

research action was the collection, annotation, elicited from speakers with mild non fluent aphasia. The

documentation, and linguistic analysis of spoken discourse control group comprises individuals who have suffered a

of Greek speakers with aphasia. heart attack. The choice of these individuals as a control

The development of GREECAD had to meet the following group was made to ensure the comparability of the personal

requirements: a) to include a representative sample of narrative samples (Task 1) in terms of their textual

Greek as spoken by individuals with aphasia, b) to characteristics. Therefore, in accordance to the stroke story

document speech samples with rich metadata, which production by speakers with aphasia, the control group

include demographic information, information on the participants narrated their “heart attack story”. Participants

patients’ medical record as well as their speech and of the control group were matched for age and level of

language therapy and neuropsychological evaluation, c) to education to the aphasic patients.

provide annotated speech samples which encode properties

of speech as well as linguistic information at the No Age Sex Cases

micro-linguistic (words, POS, grammatical, semantic, and range

phonological errors, clause types, etc.) and discourse level M F

(narrative structure units, main events, evaluation devices, Speakers 18 39-67 15 3 Non fluent

etc.). with years aphasia

In this paper, the process of designing the GREECAD aphasia (some with

corpus are presented, regarding data collection, anomic

transcription, and annotation of speech samples. Given that features)

resources of this kind are quite limited, a major aim of the Control 8 43-71 8 0 Individuals

development of GREECAD was to provide a set of group years with a heart

specifications which could serve as a methodological basis attack

for the development of other relevant corpora, and,

therefore, to contribute to future research in this area.

Table 1: Characteristics of participants

2. Data Collection 4. The GREECAD Corpus

Among the various discourse types that have been studied,

The spoken discourse samples of speakers with aphasia

narrative discourse has attracted more attention in aphasia

and those of the control group were manually transcribed

research, mainly because the abstract narrative schema

and annotated. Speakers with aphasia are currently

provides an objective framework for the analysis of

represented in the corpus with 72 scripts, while the control

speakers’ productions and their comparison to healthy

group with 28 scripts.

controls. Therefore, a protocol of four narrative tasks

The discourse samples are documented with rich metadata

(Kakavoulia et al., 2014) was developed to elicit spoken

which include demographic information about the

discourse samples from Greek speakers with aphasia.

participants, as well as detailed information on the patients’

Previous research (Doyle et al., 1998) shows that the

medical record, including the type of aphasia, and their

discourse produced by speakers with aphasia is influenced

speech and language therapy and neuropsychological

by the characteristics of elicitation tasks, such as the type of

evaluation, including their scores on the Boston Diagnostic

stimuli and the modality of presentation, as well as by the

Aphasia Examination (Greek version: Papathanassiou et al.,

cognitive and linguistic requirements of the tasks,

2008) and the Boston Naming Test (Greek version: Simos,

depending on the particular clinical characteristics of each

Kasselimis & Mouzaki, 2011).

individual. Thus, the protocol includes different narrative

genres (personal narrative, third person narrative, fairy tale,

Scripts Tokens Clauses

N N Mean Min Max N Mean Min Max

(std) (std)

Speakers 72 4.643 64,49 14 117 1.158 16,1 4 36

with

aphasia

Control 28 4.006 143,1 68 208 871 31,1 12 56

group

Total 100 8.649 2.039

Table 2: The GREECAD Corpus

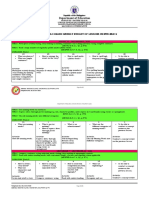

Figure 1 shows tier dependencies of the multi-tiered

5. Transcription and Annotation annotation scheme:

Discourse samples were manually transcribed and

annotated using the ELAN transcription and annotation

tool. Transcription was orthographic using the Greek

alphabet. A transcription protocol was designed as to

encode the necessary information for linguistic analysis,

excluding detailed phonological information. Specific

conventions were used for unintelligible words and

neologisms, while no special symbols were used. The

transcripts were time-aligned with the audio files at

utterance, clause, and word level.

Annotation was carried out to encode linguistic

information of the patients’ spoken discourse at various

levels. A structured, multi-tiered annotation scheme was

designed in order to include all the parameters of spoken

discourse under investigation. These parameters include

speech and non-speech events (e.g. vowel and consonant

lengthening, pauses, filled gaps, coughing, laughter, etc.),

micro-linguistic features (words, POS, grammatical,

semantic, and phonological errors, clauses, etc.), as well as

discourse features (narrative structure units, main events,

evaluation devices).

The annotated corpus is available in XML / EAF format,

which allows the future analysis of data with automatic

computational linguistic techniques. It was based on the

Formal Framework for Linguistic Annotations (Bird &

Liberman, 1999; Ide & Suderman, 2007, 2014) and the Figure 1: Tier dependencies of the annotation scheme

template is governed by token-based, type-based, and

graph-based hierarchy. The particular template with a A set of detailed criteria regarding accurate transcription,

mixture of these hierarchies provides many options and definition of speech segment boundaries (utterances,

advantages. clauses, and words), identification of each annotation

For ensuring accurate and consistent transcription and category and assignment of a valid value at each one were

annotation, a Transcription and Annotation Guide was provided to the annotators. In the following sections, a

compiled (Varlokosta et al., 2013), which includes detailed brief description of the main annotation tiers is provided.

guidelines regarding all aspects of the procedure. All

annotators were trained by experts on Corpus Linguistics, 5.1.1. Patient transcription

This group includes two transcription tiers: the primary or

who were experienced in data collection and processing

“rough” transcription (parent tier) and the secondary,

and in the use of the ELAN tool. Moreover, a pilot phase

processed transcription (child tier). The first one contains

was carried out in order to assess the appropriateness of the

anything which has been uttered by the participant,

established procedures for the transcription and annotation

orthographically transcribed in the Greek alphabet.

of speech samples. The outcome of this procedure was a set

Processed transcription is the result of “clearing” the

of modifications regarding the annotation scheme, the

primary transcription of: a) repetitions: all but the final

annotation guidelines and specific annotation criteria.

occurrence of a repeated word, phrase or segment were

eliminated, excluding repetition for emphasis, b)

5.1 Annotation Scheme self-corrections, c) formulaic phrases, d) one-word replies,

e) parts of discourse irrelevant to the narrative content.

Processed transcription provides the basis for the linguistic significant event of the story, which, at the same time, is

measurements of participants' discourse (number of independent of the other story events. Main events usually

utterances, clauses, words), as well as for the comprise textual units larger than one clause and include

measurements of verbal flow (words / minute), verbal temporal and causal relationships between events.

disruption, syntactic complexity, and narrative

macrostructure. 5.1.6. Evaluation

The evaluation tier is not embedded in the narrative

5.1.2. Speech and non-speech events structure group of tiers, since evaluative devices might

In this tier the events of speech are annotated, such as cross the boundaries of stories’ structural components.

vowel and consonant lengthening, silence, pauses (longer The category of evaluation includes linguistic devices

than 0,5 sec), noise, filled gaps, etc. The tier of Events which indicate the emotional and cognitive status of the

refers to the primary, “rough” transcription tier. narrator and his attitude towards the story events and

characters. Evaluation expresses the narrator’s

5.1.3. Reformulations involvement in the narrative and constitutes a second

This tier contains: a) self-corrections at word level (e.g. narrative layer, which transforms a simple sequence of

“the next time the next day the hare went to the tortoise”, events to a worth-telling story. In line with previous studies

“the woman shu shut sh, no, stole the ring”), which can be on evaluation of aphasic discourse (Armstrong, 2005;

phonological, lexical or morphological, b) repetitions of a Armstrong & Ulatowska, 2007, 2006; Ulatowska et al.,

non evaluative function (e.g. “at at at night”). 2006, 2011), the following evaluative features are

annotated: a) external evaluation (narrator’s comments,

5.1.4. Utterances sometimes directly addressed to story recipient), b)

This tier includes two child tier groups: clauses and words. repetition of words or phrases for emphasis, c) words and

Utterance is defined using mainly phonological criteria, as phrases indicating emotional state, as well as inherently

the speech section which follows and precedes silence, and evaluative lexical items (e.g. nice, handsome, ugly,

coincides with an intonational curve. However, in the ferocious, serious, funny, etc.), d) metaphors and similes, e)

aphasic speech the intonational curve can be difficult to metalinguistic function (narrator’s comments on his own

identify, since speech is often fragmented and laborious. In speech (e.g. “I cannot find/recall/remember the word”, “I

this case, semantic criteria are also applied to define the know the word but I cannot say it”, “Do you understand

utterance boundaries. The tier of clauses is a child tier to what I’m saying?”), f) reported speech (direct and indirect).

the one of utterances. Clause boundaries are set and each

clause is further annotated as a complete / incomplete and a

grammatical / ungrammatical one, as well as for its type. 6. Conclusion

The tier of words is a child tier to the one of clauses. GREECAD is the first systematic attempt to develop an

Number of words in each clause is indicated and each word annotated corpus of aphasic discourse for Greek. The

is further annotated with respect to its POS and to the speech samples of individuals with aphasia included in the

morphosyntactic, phonological, and lexical / semantic current version of the corpus are being analyzed in terms of

errors it might contain. Regarding word counting, the a set of measures, such as: a) verbal production and verbal

criteria proposed by Nicholas & Brookshire (1993) were flow (number of utterances, sentences and words, MLU,

followed: to be counted as words, lexical items have to be words / minute), b) syntactic complexity and

intelligible in context but not necessarily complete, grammaticality (number of conjunctions / total number of

accurate and relevant to the picture story or to the topic words, number of grammatical clauses / total number of

being discussed. clauses, number of subordinate clauses / total number of

clauses, noun / verb ratio, etc.), c) verbal disruption:

5.1.5. Narrative structure

self-corrections, repetitions, abandoned clauses, gap-fillers,

This group of annotation tiers refers to the analysis of

formulaic expressions, d) narrative structure (number of

narrative discourse at the level of macrostructure. More

main events, narrative structure units, number of clauses /

specifically, it includes: a) a tier where the components of

unit, evaluative devices by category, etc.). It is worth

narrative structure are annotated (“narrative elements”) and

noting that the annotation scheme designed for the

b) a tier where the main informational units of discourse,

development of GREECAD has been proven functional,

the story’s “main events” are annotated (“main events”).

flexible and broad, allowing the extended linguistic

The structural components of the elicited narratives are

annotation of discourse samples in a consistent way.

annotated on the basis of the Labovian model of narrative

The availability of the annotated aphasic discourse samples

structure (Labov, 1972; Labov & Waletzky, 1967), which

to the research community in combination with the rich

includes the following structural units: a) Abstract, b)

metadata that accompany them, are expected to increase

Orientation, c) Complication, d) Resolution, e) Coda.

interest in the linguistic study of aphasia in Greek and to

Furthermore, for measuring the stories’ informational

support the interdisciplinary study of aphasia, thereby

content, the number of “main events” was used as an

contributing to a deeper and broader investigation of the

indicator (Capilouto, Wright & Wagowich, 2006; Wright et

complex phenomenon of aphasia.

al., 2005). Main events are defined as single-clause or

multi-clause units of a story, each one of which refers to a

7. Acknowledgements Doyle, P. J., McNeil, M. R., Spencer, K. A., Goda, A. J.,

This research action was co-financed by the European Cottrell, K. & Lustig, A. P. (1998). The effects of

Union (European Social Fund) and Greek national funds concurrent picture presentations on retelling of orally

through the operational program “Education and Lifelong presented stories by adults with aphasia. Aphasiology,

Learning” of the National Strategic Reference Framework, 12, pp. 561-574.

research program THALES-UOA “Levels of impairment Harley, T. (2001). The Psychology of Language: From

in Greek aphasia: Relationship with processing deficits, Data to Theory (2nd edition). New York: Psychology

brain region, and therapeutic implications” (PI: Spyridoula Press.

Varlokosta). Ide, N. & Suderman, K. (2007). GrAF: A graph-based

We are grateful to Constantin Potagas, Ilias Papathanasiou, format for linguistic annotations. In Proceedings of the

Georgia Kolintza, and Ioannis Evdokimidis for patient Linguistic Annotation Workshop. Stroudsburg, PA:

referral, to Margarita Atsidakou, Eva Efstratiadou, Association for Computational Linguistics, pp. 1-8.

Anastasia Archonti, Ariadni Chatzidaki, Christoforos Ide, N. & Suderman, K. (2014). The linguistic annotation

Routsis, Lina Chatziantoniou, and Dimitrios Kasselimis for framework: A standard for annotation interchange and

clinical testing, to Athina Kontostavlaki for the merging. Language Resources and Evaluation, 48, pp.

development of the project Database, to Eleni Konsolaki 395-418.

for the coordination of the Annotators Team, to Aikaterini Kakavoulia, Μ., Stamouli, S., Foka-Kavalieraki, P.,

Pantoula, Pola Drakopoulou, and Sofia Apostolopoulou for Economou, Α., Protopapas, A. & Varlokosta, S. (2014).

the data collection, and to Christina Alexandri, Sofia A battery for eliciting narrative discourse by Greek

Apostolopoulou, Dimitra Arfani, Kelly Atsali, Alexandros speakers with aphasia: Principles, methodological issues,

Bakogianis, Sofia Banou, Konstantina Daraviga, Vassiliki and preliminary results [in Greek]. Glossologia, 22, pp.

Dechounioti, Evi Doli, Pola Drakopoulou, Martha Drouga, 41-60.

Popi Eldahan-Apergi, Spyridoula Gasteratou, Mariana Labov, W. (1972). Language in the Inner City. Philadelphia:

Georgouli, Aliki Gotsi, Nasia Gouma, Konstantina Goni, The University of Pennsylvania Press.

Chara Gourgouleti, Dimitris Katsimpokis, Giannis Kritikos, Labov, W. & Waletsky, J. (1967). Narrative analysis. In J.

Alexandra Kostaletou, Panayotis Kounoudis, Anna Helm (Εd.), Essays in the Verbal and Visual Arts. Seattle:

Michalaki, Sofia Pagoni, Panagiotis Panagopoulos, University of Seattle Press, pp. 12-44.

Kalliopi Papadodima, Aikaterini Pantoula, Stamatina Lemme, M. L., Hedberg, N. L. & Bottenberg, D. F. (1984).

Remoundou, Maria Saridaki, Alexandros Tsaboukas, and Cohesion in narratives of aphasic adults. In R.H.

Ilias Valaskatzis for their valuable work in the transcription Brookshire (Εd.), Clinical Aphasiology. Minneapolis,

and annotation of the speech samples. MN: BRK, pp. 215-222.

MacWhinney, B., Fromm, D., Forbes, M. & Holland, A.

(2011). AphasiaBank: Methods for studying discourse.

8. Bibliographical References Aphasiology, 25, pp. 1286-1307.

MacWhinney, B., Fromm, D., Holland, A. & Forbes, M.

Armstrong, E. (2000). Aphasic discourse analysis: The

(2012). AphasiaBank: Data and methods. In N. Mueller

story so far. Aphasiology, 14, pp. 875-892.

& M. Ball (Eds.), Methods in Clinical Linguistics. New

Armstrong, E. & Ulatowska, H. K. (2007). Making stories:

York: Wiley, pp. 31-48.

Evaluative language and the aphasia experience.

McNeil, M. R., Sung, J. E., Yang, D., Pratt, S. R., Fossett, T.

Aphasiology, 21, pp. 763-774.

R. D., Pavelko, S. & Doyle, P. J. (2007). Comparing

Armstrong, E. & Ulatowska, H. K. (2006). Stroke stories:

connected language elicitation procedures in person with

Conveying emotive experiences in aphasia. In M. J. Ball

aphasia: Concurrent validation of the Story Retell

& J. S. Damico (Eds.), Clinical Αphasiology: Future

Procedure. Aphasiology, 21, pp. 775-790.

Directions. Hove, UK: Psychology Press.

Menn, L., Ramsberger, G. & Helm-Estabrooks, N. (1994).

Armstrong, E. (2005). Expressing opinions and feelings in

A linguistic communication measure for aphasic

aphasia: Linguistic options. Aphasiology, 19, pp.

narratives. Aphasiology, 8, pp. 315-342.

285-296.

Mesulam, M. M. (2000). Principles of Behavioral and

Berko-Gleason, J., Goodglass, H., Obler, L., Green, E.,

Cognitive Neurology (2nd edition). New York: Oxford

Hyde, M. & Weintraub, S. (1980). Narrative strategies of

University Press.

aphasics and normal-speaking subjects. Journal of

Nicholas, L. E. & Brookshire, R. H. (1995). Presence,

Speech and Hearing Research, 23, pp. 370-382.

completeness and accuracy of main concepts in the

Bird, S. & Liberman, M. (1999). A Formal Framework for

connected speech of non-brain-damaged adults and

Linguistic Annotation. Technical Report

adults with aphasia. Journal of Speech and Hearing

(MS-CIS-99-01). University of Pennsylvania.

Research, 38, pp. 145-156.

Capilouto, G. J., Wright, H. H. & Wagovich, S. A. (2006).

Nicholas, L. E. & Brookshire, R. H. (1993). A system for

Reliability of main event measurement in the discourse

quantifying the informativeness and efficiency of the

of individuals with aphasia. Aphasiology, 20, pp.

connected speech of adults with aphasia. Journal of

205-216.

Speech and Hearing Research, 36, pp. 338-350.

De Roo, E. (1999). Agrammatic Grammar: Functional

Obler, L. K. & Gjerlow, K. (1999). Language and the Brain.

Categories in Agrammatic Speech. Hague: Theseus.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Seventh International Conference on Language

Olness, G. S. 2006. Genre, verb, and coherence in Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2010), pp. 2824-2830.

picture-elicited discourse of adults with aphasia. Wright, H. H. (2011). Discourse in aphasia: An

Aphasiology, 20, pp. 175-187. introduction to current research and future directions.

Olness, G. S. & Ulatowska, H. K. (2011). Personal Aphasiology, 25, pp. 1283-1285.

narratives in aphasia: Coherence in the context of use. Wright, H. H., Capilouto, G. J., Wagovich, S. A., Cranfill,

Aphasiology, 25, pp. 1393-1413. T. & Davis, J. (2005). Development and reliability of a

Olness, G. S., Matteson, S. E. & Stewart, C. T. (2010). “Let quantitative measure of adults’ narratives. Aphasiology,

me tell you the point”: How speakers with aphasia assign 19, pp. 263-273.

prominence to information in narratives. Aphasiology,

24, pp. 697-708.

Papathanassiou, E., Papadimitriou, D., Gavrilou, V. &

Michou, A. (2008). Normative data for the Boston

Diagnostic Aphasia Battery in Greek: Gender and age

effects [in Greek]. Psychology, 15, pp. 398-410.

Saffran, E. M., Sloan-Berndt, R. & Schwartz, M. (1989).

The quantitative analysis of agrammatic production:

Procedure and data. Brain and Language, 37, pp.

440-479.

Simos, P.G., Kasselimis, D. & Mouzaki, A. (2011). Age,

gender, and education effects on vocabulary measures in

Greek. Aphasiology, 25, pp. 492-504.

Stark, J. A. (2010). Content analysis of the fairy tale

Cinderella - A longitudinal single case study of narrative

production: “From rags to riches”. Aphasiology, 24, pp.

709-724.

Ulatowska, H. K., Freedman-Stern, R., Doyel, A. W.,

Macaluso-Haynes, S. & North.A. (1983). Production of

narrative discourse in aphasia. Brain and Language, 19,

pp. 317-334.

Ulatowska, H. K., North, A. J. & Macaluso-Haynes, S.

(1981). Production of narrative and procedural discourse

in aphasia. Brain and Language, 13, pp. 345-371.

Ulatowska, H. K., Olness, G. S., Keebler, M. & Tillery, J.

(2006). Evaluation in stroke narratives: A study in

aphasia. Brain and Language, Special Issue Academy of

Aphasia 2006 Program, 99 (1-2), pp. 51-52.

Ulatowska, H. K., Reyes, Β. Α., Santos, T. O. & Worle, C.

(2011). Stroke narratives in aphasia: The role of reported

speech, Aphasiology, 25, pp. 93-105.

Varlokosta, S., Karasimos, Α., Stamouli, S., Kakavoulia,

M., Markopoulos, G., Goutsos, D., Fyndanis, V.,

Neranztini, M. & Pantoula, A. (2013). Greek Corpus of

Aphasic Discourse. Transcription and Annotation Guide

[in Greek]. Athens: National and Kapodistrian

University of Athens.

Vermeulen, J., Bastiaanse, R. & van Wageningen, B. 1989.

Spontaneous speech in aphasia: A correlational study.

Brain and Language, 36, pp. 252-274.

Westerhout, E. & Monachesi, P. (2006). A pilot study for a

Corpus of Dutch Aphasic Speech (CoDAS). In

Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on

Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2006), pp.

1648–1653.

Williams, C., Thwaites, A., Buttery, P., Geertzen, J.,

Randall, B., Shafto, M., Devereux, B. & Tyler, L. (2010).

The Cambridge Cookie-Theft Corpus: A corpus of

directed and spontaneous speech of brain-damaged

patients and healthy individuals. In Proceedings of the

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5825)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Effectiveness of Gamification and Game-Based Learning in Spanish Adolescents With DyslexiaDocument11 pagesEffectiveness of Gamification and Game-Based Learning in Spanish Adolescents With DyslexiaLeiraNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Oral and Written Language Scales Listening Comprehension and Oral Expression (OWLS)Document13 pagesOral and Written Language Scales Listening Comprehension and Oral Expression (OWLS)alessarpon7557No ratings yet

- ISTAL23 - Psychogyiou & Karasimos v2Document19 pagesISTAL23 - Psychogyiou & Karasimos v2Athanasios N. KarasimosNo ratings yet

- DARIAH-EU - AnnualMeeting2019 - DARIAH-GR v2Document17 pagesDARIAH-EU - AnnualMeeting2019 - DARIAH-GR v2Athanasios N. KarasimosNo ratings yet

- Competition in Infl Ection and Word-FormationDocument334 pagesCompetition in Infl Ection and Word-FormationAthanasios N. KarasimosNo ratings yet

- (15699846 - Journal of Greek Linguistics) Review Article - Morphology in Greek Linguistics - The State of The ArtDocument53 pages(15699846 - Journal of Greek Linguistics) Review Article - Morphology in Greek Linguistics - The State of The ArtAthanasios N. KarasimosNo ratings yet

- Self Empowerment TeachingsDocument138 pagesSelf Empowerment TeachingsRangerItalyNo ratings yet

- Guide For The Development of The Practical Component - Unit 2 - Stage 4 - Simulated Scenario and Research ResultsDocument11 pagesGuide For The Development of The Practical Component - Unit 2 - Stage 4 - Simulated Scenario and Research ResultsNadia TorresNo ratings yet

- Retention CH 5Document4 pagesRetention CH 5Dm VaryaniNo ratings yet

- Pivot 4A Lesson Exemplar Using The Idea Instructional ProcessDocument14 pagesPivot 4A Lesson Exemplar Using The Idea Instructional ProcessJocelyn100% (1)

- Learning Plan Science 7 Fungi BateiralDocument2 pagesLearning Plan Science 7 Fungi Bateiralellis garcia100% (1)

- 3is Simplified Activity Sheet Week 1 No Answer KeyDocument6 pages3is Simplified Activity Sheet Week 1 No Answer KeyRence Kristelle RiveraNo ratings yet

- Tarone 2010Document10 pagesTarone 2010dmsdsNo ratings yet

- Why Should I Share? Examining Social Capital and Knowledge Contribution in Electronic Networks of Practice1Document24 pagesWhy Should I Share? Examining Social Capital and Knowledge Contribution in Electronic Networks of Practice1Afzaal AliNo ratings yet

- Employees' Perception of Performance Appraisal SystemDocument16 pagesEmployees' Perception of Performance Appraisal Systemtamaha25100% (1)

- Elc270 Course BriefingDocument11 pagesElc270 Course BriefingFatin AisyahNo ratings yet

- A Survey of The Impact of Perceived Organizational Support On Organizational Citizenship Behavior With Mediating Role of Affective Commitment (Case Study: Shafa Private Hospital of Sari City)Document6 pagesA Survey of The Impact of Perceived Organizational Support On Organizational Citizenship Behavior With Mediating Role of Affective Commitment (Case Study: Shafa Private Hospital of Sari City)TI Journals PublishingNo ratings yet

- Learning Plan Template For Microteach 3 1 1Document6 pagesLearning Plan Template For Microteach 3 1 1api-300681597No ratings yet

- IntroClin - Pedia IE, CVGHDocument11 pagesIntroClin - Pedia IE, CVGHAnnbe BarteNo ratings yet

- Service Quality and User Satisfaction Questionnaire - Library ContextDocument1 pageService Quality and User Satisfaction Questionnaire - Library ContextRich KishNo ratings yet

- NCPDocument3 pagesNCPCharles Mallari Valdez100% (1)

- Philosophy of EducationDocument2 pagesPhilosophy of Educationhtindall2414No ratings yet

- Job QuestionsDocument6 pagesJob QuestionsAugustaLeighNo ratings yet

- SSU1033 AssignmentDocument23 pagesSSU1033 AssignmentChristy Lu0% (1)

- SKPX 3013 Teori Perkembangan Kerjaya: Pusat Kesejahteraan Manusia & Masyarakat Fakulti Sains Sosial Dan KemanusiaanDocument19 pagesSKPX 3013 Teori Perkembangan Kerjaya: Pusat Kesejahteraan Manusia & Masyarakat Fakulti Sains Sosial Dan KemanusiaanThivanya SivaNo ratings yet

- Helmholtz. The Facts of Perception (1878)Document34 pagesHelmholtz. The Facts of Perception (1878)Blaise09No ratings yet

- Department of Education: Simplified Melc-Based Weekly Budget of Lessons in Mtb-Mle 2Document6 pagesDepartment of Education: Simplified Melc-Based Weekly Budget of Lessons in Mtb-Mle 2Cherryl Virtudazo DaguploNo ratings yet

- Name Someone Who... : Activity TypeDocument2 pagesName Someone Who... : Activity TypeSiti IlyanaNo ratings yet

- Nursing Interview Guide: Prior To The InterviewDocument2 pagesNursing Interview Guide: Prior To The InterviewmiiszNo ratings yet

- The Need Analysis of Module Development Based On Search, Solve, Create, and Share To Increase Generic Science Skills in ChemistryDocument8 pagesThe Need Analysis of Module Development Based On Search, Solve, Create, and Share To Increase Generic Science Skills in ChemistryImam SetiawanNo ratings yet

- Math Syllabus 9th GradeDocument2 pagesMath Syllabus 9th Gradeapi-317614387No ratings yet

- BBE Week 3 P3Document20 pagesBBE Week 3 P3Edufluent ResearchNo ratings yet

- Academic Reading & Writing - Resume WritingDocument33 pagesAcademic Reading & Writing - Resume WritingMuhammad JunaidNo ratings yet

- Letter To Validators .Letter To Respondents. Questionnaire. GROUP 6 12 HUMSS 1Document7 pagesLetter To Validators .Letter To Respondents. Questionnaire. GROUP 6 12 HUMSS 1Ronald Chester LorenzanaNo ratings yet