Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Employees' Decision Making in The Face of Customers' Fuzzy Return Requests

Employees' Decision Making in The Face of Customers' Fuzzy Return Requests

Uploaded by

Alexandra ManeaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Employees' Decision Making in The Face of Customers' Fuzzy Return Requests

Employees' Decision Making in The Face of Customers' Fuzzy Return Requests

Uploaded by

Alexandra ManeaCopyright:

Available Formats

Sijun Wang, Sharon E.

Beatty, & Jeanny Liu

Employees’ Decision Making in the

Face of Customers’ Fuzzy Return

Requests

Frontline service employees frequently encounter customers’ fuzzy requests, defined as requests that are slightly

or somewhat outside company policy but not completely unacceptable or detrimental to the company. Employees’

compliance decisions can profoundly affect customers, organizations, and employees themselves. However, the

complex decision process in which service employees engage is largely unexplored. The authors draw from script

and motivated reasoning theories, as well as qualitative interviews, to model employees’ responses to customers’

fuzzy requests in a retail setting. The results, which are based on a national survey of retail employees, indicate

that employees with higher customer orientation and higher conflict avoidance tend to handle fuzzy return requests

in a friendlier, more effortful manner, especially when customers demonstrate an affiliative style. In contrast, when

customers display a dominant style, employees engage in motivated reasoning and perceive the request to be less

legitimate, reducing their likelihood of complying. In addition, the employees’ perceived flexibility influences their

compliance decisions, but punishment expectations do not. The authors conclude with some managerial

implications, including better identification of these requests and more training of employees to handle them

appropriately.

T

Keywords: fuzzy requests, compliance, script theory, role theory, motivated reasoning, retail returns, legitimacy

he marketing literature has long recognized the impor- a table with a view. While some requests may be innocent

tant roles of frontline employees in service delivery problems (e.g., returning a failed product bought from the

and recovery (e.g., Bitner, Booms, and Tetreault store), others may involve intentionally taking advantage of

1990; Schneider 1991). According to Langeard et al.’s a service provider (e.g., returning a dress after wearing it for

(1981) Servuction Service Model, the quality of service a special occasion [e.g., Schmidt et al. 1999]).

performance depends on the interaction and performance of In contrast to both the common organization assumption

three key players in the delivery process: the service organi- that customers are always right (e.g., Ringberg, Odekerken-

zation system, the contact employee, and the customer. In Schroder, and Christensen 2007) and the emphasis in cur-

this relationship, customers are motivated to compete with rent literature on problem or fraudulent customers, in which

the firm and its employees to seize control of the service customers or their actions are completely wrong (e.g., Har-

process to increase their utility and personal satisfaction ris 2010), many customers’ requests lie between these

(Bateson 1985). One way customers do this is by asking for extremes. These requests often are somewhat or slightly

special requests that require the employee or the firm to outside company policy, not addressed by company policy,

adapt the service to these requests (Bitner, Booms, and or outside the employee’s job description or job expecta-

Tetreault 1990). tions, but they are not unacceptable or detrimental to the

Some requests greatly deviate from the normal service company. We label these requests as “fuzzy requests,”

scope and employee expectations, while others are routine, implying that how and what employees should do regarding

such as a customer asking the host to seat his or her party at these requests are not always clear.

Although the marketing literature has not identified or

examined employees’ reactions to customers’ fuzzy requests,

their occurrence is unquestionable; many excellent service

Sijun Wang is Associate Professor of Marketing, Department of Marketing

firms, such as Ritz-Carlton and the Mayo Clinic, focus on

and Business Law, College of Business Administration, Loyola Marymount

meeting unconventional or unexpected customer requests

University (e-mail: swang15@lmu.edu). Sharon E. Beatty is Reese Phifer

(Berry and Bendapudi 2003; Michel, Bowen, and Johnston

Professor of Marketing, Department of Management and Marketing, Cul-

2008). Furthermore, several studies indicate the ubiquity of

verhouse College of Commerce and Business Administration, University

these incidents and their challenges to frontline employees

of Alabama (sbeatty@cba.ua.edu). Jeanny Liu is Assistant Professor of

Marketing, College of Business & Public Management, University of La

(e.g., Beatty et al. 1996; Bitner, Booms, and Mohr 1994). In

Verne (e-mail: jliu@laverne.edu). The authors gratefully acknowledge the

contrast to the strong presence of fuzzy requests in the mar-

comments and suggestions provided by the following people on previous

ketplace, a Strativity Group (2008) survey shows that only

versions of this article: Rich Lutz, Mark Arnold, Gianfranco Walsh, and

29% of executives believe that employees have the tools

Mark Leach. In addition, they acknowledge the helpful comments from the

three anonymous JM reviewers.

© 2012, American Marketing Association Journal of Marketing

ISSN: 0022-2429 (print), 1547-7185 (electronic) 69 Volume 76 (November 2012), 69–86

and authority to solve customer problems and to delight reasoning theory (Kunda 1990). Finally, we find that

customers. employee gender and organizational tenure moderate sev-

The current study focuses on a specific type of customer eral key relationships in the model. The findings of this

fuzzy request: fuzzy return requests in a retail context. study offer significant managerial insights for service orga-

While retail returns were reported to reach 8.9% of all nizations with regard to employees’ compliance decisions

goods sold in a year and merchandise returned to stores with customers’ fuzzy return requests. We first discuss our

reached $217 billion in 2011, only 6.6% of these returns qualitative work and literature review; then, the model and

were considered fraudulent returns (National Retail Federa- hypotheses; and finally, the study procedure and findings.

tion 2011). Thus, a significant proportion of customer

return requests are likely to be classified as fuzzy return

requests (i.e., outside policy but not completely unaccept- Theory Building and Hypotheses

able or fraudulent1), as evidenced by 19.7% of returns Qualitative Research and Theory Development

being made without receipts, even though almost every

retailer requires a receipt as proof of purchase (National The qualitative research consisted of 21 in-depth interviews

Retail Federation 2011). When customers present a fuzzy with a group of customer service representatives from a

return request to a contact employee, the employee must variety of retailers, ranging from one-store, family-owned

decide on the spot whether and how to comply with this shops to national chain retailers. In our interviews, we

request, while taking into account several important issues asked informants to recall several return incidents in which

and concerns instantaneously. What drives a contact the customer’s return request was outside the store policy

employee’s approach and decision making when dealing but not completely unacceptable or fraudulent. In the inter-

with such a customer request? What are the important fac- views, informants elaborated on why they chose to comply

tors affecting how he or she chooses to handle these or not comply with these requests. Informants had no trou-

requests and whether he or she decides to bend the rules ble retrieving one or more return incidents falling into our

(i.e., comply or not)? Understanding employee decision definition of a fuzzy request. The average length of the

making regarding these important decisions is critical to interviews was 90 minutes.

firms in their efforts to manage service encounters effec- Following Strauss and Corbin’s (1998) recommendations,

tively (Bitner, Booms, and Tetreault 1990). we first analyzed interview transcripts, preparing memos for

In addressing these questions, our study makes several each. Then, we reviewed and discussed the interviews and

important contributions. First, we model contact employees’ notes extensively. We used open-coding methods to identify

compliance decisions (both compliance process and out- concepts with common properties and dimensions. We then

come) with regard to customers’ fuzzy return requests, the clustered data pertaining to the same category together and

first such attempt in the literature. Noting that compliance developed a set of antecedents relative to employee’s com-

behaviors should be studied from both process and outcome pliance behavior (with a customer’s fuzzy return request).

perspectives, we identify antecedents relevant to the compli- We also conducted an extensive literature review focus-

ance behaviors of frontline employees. In particular, while ing on service quality issues (e.g., Parasuraman, Zeithaml,

much research effort has focused on customers’ reactions/ and Berry 1985), service failure and recovery (e.g., Smith,

perceptions to employee behaviors in service encounters Bolton, and Wagner 1999), organizational behavior (e.g.,

(e.g., Mohr and Bitner 1995; Parasuraman, Zeithaml, and Vecchio 1995), and communication (e.g., Webster and

Berry 1985), our study sheds light on how and what condi- Driskell 1983). This literature review and our qualitative

tions are conducive to contact employees acting in certain research led to the identification of four bundles of ante-

ways toward customers. In the context of fuzzy return cedents important to compliance behavior: customer factors,

requests, which conceptually resemble a service failure or request factors, organizational factors, and several individual

customer complaint encounter, we find that employees with difference factors of the employee (which we simply call

higher customer orientation (CO) and higher conflict avoid- “employee factors”). Appendix A presents the list of con-

ance (CA) tend to handle customers’ fuzzy requests in a structs and example excerpts from the in-depth interviews.

friendlier, more effortful manner, especially when cus- Our model of employee compliance decision making is

tomers demonstrate a more affiliative interaction style dur- a middle-range theory (Merton 1968), which falls between

ing the encounter. In terms of the actual outcome, we find substantive and more formal theories (Glaser and Strauss

that employees are more likely to comply with fuzzy 1967). Our goal was to develop a framework through

requests when they have more flexibility but that punish- grounded theory (Strauss and Corbin 1998) that represents

ment expectations do not influence these decisions. a view of the important variables and their interrelation-

Furthermore, a customer’s dominant style reduces the ships relative to the topic.

employee’s perceptions of the request’s legitimacy and his

or her willingness to comply with it. Differential findings Theoretical Background: Compliance Outcome

regarding customers’ affiliative versus dominant styles and Process

enrich the literature based on script theory and motivated Researchers have paid little attention to compliance behav-

ior in marketing, and the term has widely varying meanings

1We do not include requests outside the employee’s job descrip- (e.g., Joshi 2010; Payan and McFarland 2005). Our study

tion as part of customer return requests, because these requests are examines service employees’ compliance behavior with

likely to be part of the frontline employee’s job description. respect to customers’ fuzzy return requests. By definition,

70 / Journal of Marketing, November 2012

compliance is demonstrated when a party displays “overt Script Theory and Overview of Framework

behavioral adherence” (Brill 1994, p. 212). Overt behav-

Role and script theories explain many frontline employees’

ioral adherence to a customer’s request (e.g., exchanging an

behaviors (e.g., Walker, Churchill, and Ford 1975). In an

item, giving store credit or cash back), which is a compli-

organizational context, an employee’s role is his or her per-

ance outcome, is an important component of service

ceptions of what the role senders expect of the employee.

employees’ reactions to customers’ requests. Moreover, it is

Role senders, such as organizations (e.g., supervisors,

equally important to understand how employees actually

coworkers) and customers, provide input to individuals,

interact (i.e., the compliance process) with the customer

allowing them to understand or interpret their roles more

during service encounters (Bitner, Booms, and Tetreault

accurately. In particular, service firms use service scripts to

1990); however, little research systematically studies what

standardize customer–firm interactions. However, in our

drives these critical behaviors.

study context, organizations have difficulty prescribing

In the service encounter literature, researchers view ser-

vice quality as being composed of two dimensions: the ser- exactly how an employee should handle a customer’s

vice outcome and service process (e.g., Mohr and Bitner request given the variance possible (Hartline and Ferrell

1995; Parasuraman, Zeithaml, and Berry 1985). Broadly 1996). Thus, the compliance process is largely discretionary

speaking, the service outcome encompasses all results or with regard to the employee’s interaction with a customer

consequences associated with a service encounter, while the involving a fuzzy request (Blancero and Johnson 2001).

service process refers to the way service transactions are The employee–customer dyad interaction affects how

accomplished (Mohr and Bitner 1995). Similarly, service the employee handles the return given the proximal one-on-

recovery is understood to include both process and outcome one contact involved. Thus, customer interaction style

variables (e.g., Smith and Bolton 2002; Smith, Bolton, and (affiliation) and several employee factors (e.g., CO, CA)

Wagner 1999). Researchers have connected process variables should jointly determine the employee’s level of effort and

to procedural and interactional justice and outcome variables friendliness with regard to the request (see Figure 1).

to distributive justice. Thus, distinguishing a compliance In contrast to the processing of the return request, the

outcome and compliance process behaviors is important. employee’s decision making with regard to complying with

For our study, “compliance outcome” is the extent to the request (i.e., compliance outcome) is scripted more eas-

which an employee believes that he or she has met the ily and involves less discretionary behavior. Therefore, the

expectations of the customer rather than simply whether the expectations of relevant role senders, including the organi-

return was accepted (e.g., a customer may want a refund but zation and the customer, along with the employee’s percep-

the employee only provides store credit, thus not fully meet- tions of the specific request (and its legitimacy), will jointly

ing the customer’s expectations). Consistent with Mohr and influence the extent to which an employee fulfills the

Bitner’s (1995) broader definition of service process, “com- request (though employee factors will not play a significant

pliance process” is the way the employee handles the return role). Thus, our model indicates that a customers’ interac-

transaction and, for this study, is composed of two key tion style (affiliation), the legitimacy of the request, and

behavioral factors: effort and friendliness. Researchers have several organizational factors (both formal and informal)

consistently suggested that these factors are important com- produce the employee’s compliance outcome. We discuss

ponents of service delivery and/or the recovery process the antecedents for the compliance process and compliance

(e.g., Hui et al. 2004; Mohr and Bitner 1995). outcome next.

Employee effort. According to Mohr and Bitner (1995), Employee Factors

employee effort represents the amount of energy put into a

behavior or series of behaviors. Customers, as observers in As we noted previously, employee factors are important dri-

the service encounter, use employee effort to derive their vers of the discretionary compliance process (Hartline and

attribution of the service experience, as well as their percep- Ferrell 1996). An increasing number of studies consistently

tions of the service quality of the firm and their satisfaction show that employees with certain individual difference

with the experience. As Mohr and Bitner (1995, p. 242) characteristics display common behaviors when delivering

note, “when a service outcome is favorable, a high level of customer service (e.g., Auh et al. 2011). Thus, on the basis

employee effort may enhance satisfaction; on the other of our qualitative work and literature review, two important

hand, when the customer does not get the desired outcome, individual difference variables emerged as important in the

a low level of employee effort may cause additional aggra- context of this study: CO and CA. The following subsec-

vation to an already unsatisfactory encounter.” tions elaborate on these variables.

Employee friendliness. Emotional contagion unques- Customer orientation (CO). Brown et al. (2002, p. 111)

tionably exists in customer–employee encounters. This define employees’ CO as an “employee’s tendency or pre-

theory suggests that employee friendliness is an important disposition to meet customer needs in an on-the-job con-

component of the customers’ overall experience. Indeed, text.” It is positively related to customer satisfaction (e.g.,

research in the communication field indicates that employ- Reynierse and Harker 1992), worker performance (Brown

ees’ friendly, helpful styles elicit greater customer satisfac- et al. 2002), and job responses. Compared with employees

tion with the employee and firm (e.g., Buller and Buller with lower CO, employees with higher CO are more intrin-

1987), and researchers link it to the service recovery sically motivated to make customers happy and to go the

process (Blodgett, Hill, and Tax 1997; Hui et al. 2004). extra mile to meet their needs (Brown et al. 2002). Thus,

Customers’ Fuzzy Return Requests / 71

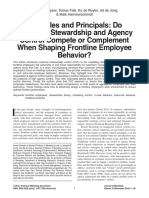

FIGURE 1

Employee Compliance Decision-Making Model

Emp

Employee

loyee F

Factors

actors Compliance

Compliance Be

Behaviors

haviors

• Customer Orientation

• Conflict Avoidance

H1

Compliance

Process

C

Customer

ustomer IInteraction

nteraction S

Styles

tyles

H2

Affiliation

R equest Le

Request gitimacy

Legitimacy

Dominance

H3

• Regulative

O rganizational F

Organizational actors

Factors H4a-c •H3 Normative H5 Compliance

• Cognitive Outcome

H6

• Norm of Flexibility

• !

Punishment Expectations

employees with higher CO will work harder to please the such as attentiveness, relaxed, open, and friendly styles. In

customer, regardless of the compliance outcome. the context of an employee–customer interaction, “affilia-

tive style” refers to the employee’s perception that a cus-

H1a: There is a positive relationship between an employee’s

CO and his or her friendliness and effort in handling the tomer engages with him or her in a warm, friendly manner.

fuzzy request (i.e., compliance process behaviors). In contrast, “dominant style” refers to the employee’s per-

ception that a customer is trying to control or dominate the

Conflict avoidance (CA). Researchers in psychology interaction. Emotional contagion theory (Hatfield, Cacioppo,

have extensively studied CA, which is an attempt to protect and Rapson 1994) proposes a direct link between employee

the self from conflict, disapproval, and negative attention and customer by affective transfer during interpersonal con-

(Rahim 1983). People who have a CA personality prefer not tact. In the service encounter literature, Dallimore, Sparks,

to assert themselves to preserve rapport and smooth rela- and Butcher (2007) demonstrate that angry customers often

tionships with others (Schroeder 1965). Oddly enough, produce similar facial displays and affective states in ser-

although marketers have studied group CA in the context of vice workers through an emotional contagion process. In an

marketing strategy decision making (Atuahene-Gima and even broader sense, each party of the client–service

Murray 2004), researchers have not linked individual provider dyad influences the other party’s behavior (Ma and

employees’ CA to their handling of customer complaints or Dubé 2011). For example, Webster (2005) finds that a cus-

requests (including return requests). Yet in our qualitative tomer evaluates an employee with a more affiliative style

interviews, informants frequently talked about trying to more favorably and is more satisfied, whereas an employee

avoid arguments with customers if possible. Thus, a posi- displaying more dominance receives less favorable cus-

tomer evaluations (Korsch and Negrete 1972). While cus-

tive relationship between an employee’s tendency to avoid

tomer interaction styles have not been associated with

conflicts and his or her compliance process is likely:

employee reactions to customers, given the dyadic, interac-

H1b: There is a positive relationship between an employee’s tive nature of customer–employee dyads, the findings

CA and his or her friendliness and effort in handling the between employee interaction styles and customer evalua-

fuzzy request (i.e., compliance process behaviors). tions should work in reverse. That is, the employee is likely

to more positively handle the request (i.e., compliance

Customer Interaction Styles process) when the customer approaches him or her with a

The social interaction model (Ben-Sira 1980) identifies two friendly, warm manner.

major interaction styles: affiliation and dominance. An affil- H2: The employee’s perceptions of the customer’s affiliative

iative style parallels Norton’s (1978) communication styles, style are related positively to his or her friendliness and

72 / Journal of Marketing, November 2012

effort in handling the fuzzy request (i.e., compliance ible, desirable, and reasonable. Consistent with Autry, Hill,

process behaviors). and O’Brien (2007) and Krapfel (1988), legitimacy draws

In addition, the employee who perceives that a customer from institutional theory and represents the extent to which

is being friendly and warm is more likely to comply with an employee perceives that a return complies with regulatory,

the customer’s request. This proposition lies in the similar normative, and cognitive expectations (Meyer and Zucker

logic of interdependency between customer and employee 1989). Thus, legitimacy encompasses three dimensions:

(or an echoing effect) as Ma and Dubé (2011) report. This regulative, normative, and cognitive legitimacy. “Regula-

idea follows from the work of Cialdini (2001), who sug- tive legitimacy” refers to the conformance of the request to

gests liking as an important persuasive tool. That is, the established return policies and procedures (i.e., whether the

employee likes the customer more (due to emotional conta- return request falls within the return period, conditions, and

gion) and so may be more willing to comply. terms set by the retailer). This type of legitimacy is closest

to the idea of whether it is or is not a fuzzy request. “Nor-

H3: The employee’s perceptions of the customer’s affiliative mative legitimacy” addresses whether the return request

style are related positively to his or her likelihood to com- conforms to commonly held social values and norms of

ply relative to the customer’s fuzzy request (i.e., his or her

compliance outcome). acceptable behavior. “Cognitive legitimacy” refers to the

appropriateness, interpretability, and comprehensibility of

In contrast, when a customer uses a dominant approach, the return request (i.e., whether it makes sense). The

the employee will need to regulate his or her outward reac- employee must judge the legitimacy of the customer’s

tions to such an approach, reducing the likelihood that he or claim according to the rationale the customer offers when

she will show anger or dismay in the situation. Thus, the returning a product, the condition of the product, and other

echoing effect occurring when the customer uses an affilia- contextual factors, such as price and the resale ability of the

tive approach is not likely to hold when the customer item.

approaches the employee in a dominant manner. Recent Although legitimacy has been studied in the context of

theorizing in dual process models has suggested that people returns in retailing (e.g., Autry, Hill, and O’Brien 2007;

will engage in various defense mechanisms to cope with Krapfel 1988) and other customer–employee interaction

uncomfortable or negative situations. As part of that contexts (e.g., Hui, Au, and Fock 2004a, b), an accurate

process, people rely on selective information and heuristics understanding of legitimacy and its impact on employees’

that help them reach a desirable conclusion while discount- decisions is still missing. For example, Hui, Au, and Fock

ing heuristics that endorse the opposing view (e.g., Giner- (2004a, b) address only cognitive legitimacy, finding a posi-

Sorolla and Chaiken 1997). Researchers refer to this goal- tive relationship between service-return legitimacy and

directed process as “motivated reasoning” (Kunda 1990). In employee compliance intention. In contrast, Krapfel (1988,

our study context, when an employee perceives that a cus- see p. 189), focusing on normative legitimacy, reports a

tomer is displaying a dominant style, which will tend to positive link between return request legitimacy and

make an employee uncomfortable, the employee may be employee attitude toward the customer. Finally, Autry, Hill,

motivated to discount the positive or even objective aspects and O’Brien (2007) and O’Brien, Hill, and Autry (2009)

of the fuzzy request (i.e., engage in biased, motivated rea- use single items for the three legitimacy aspects in their

soning). As a result, the employee will perceive the request studies on retail return episodes and the impact of legiti-

as less legitimate (i.e., farther away from policies and/or macy on employee attitude formation and role conflict.

less acceptable to the company). Such an unfavorable judg- Thus, given the inconsistent findings and weak measure-

ment of the request’s legitimacy allows the employee to ment issues in this area, further examination of the role of

decline the request more easily, which would be more legitimacy in employees’ compliance decisions is worth-

preferable to him or her. In contrast, when a customer while.

adopts an affiliative style, the motivated reasoning process Even though no previous research examines the impact

is not triggered (i.e., legitimacy perceptions are not invoked of legitimacy on actual behavior, it is clear from the previous

as a justification for their behaviors); rather, as we noted research and logic that when an employee calls into question

previously, behavior is directly affected (i.e., the compli- the legitimacy of the request (relative to any aspect), the

ance process and outcome). We now turn to a discussion of employee is less likely to comply with the request. Combin-

legitimacy. ing the previously mentioned arguments and the theory of

motivated reasoning, when a customer engages in a domi-

Legitimacy of the Request nant style in presenting a request, the employee will view

Employees’ judgments of the request’s legitimacy are the request as less legitimate and be less likely to comply

important because their interpretation of the request vis à with the request. Thus, legitimacy perceptions serve as a

vis their interpretation of company policy is the driving mediating mechanism between a customer displaying a

force behind their reactions to these requests. Previous stud- dominant style and the employee’s compliance decision.

ies on retail returns show the important role of legitimacy in Furthermore, as we noted previously, the customer’s affilia-

employee’s interpretations and reactions, though researchers tive style does not call into question the legitimacy of the

have generally defined and measured it simplistically (e.g., request (i.e., the employee does not engage in motivated rea-

Autry, Hill, and O’Brien 2007; Krapfel 1988). soning); instead, the affiliative style of the customer directly

Unless a return meets all requirements of store policy, influences the employee’s compliance behaviors. The pre-

the employee will need to judge whether the request is cred- ceding discussion leads us to hypothesize the following:

Customers’ Fuzzy Return Requests / 73

H4(a–c): The employee’s perceptions of the customer’s domi- severity increases, the level of illegal behavior should

nant style are related negatively to the employee’s per- decrease. In our study, the employee’s expectations of pun-

ceptions of the request’s (a) regulative legitimacy, (b) ishment capture his or her expectations of the negative con-

normative legitimacy, and (c) cognitive legitimacy.

sequences of complying with a fuzzy request. In the organi-

H4(d–f): The employee’s perceptions of the customer’s affilia- zational behavior literature, reward/punishment systems are

tive style are not related to the employee’s perceptions

of the request’s (d) regulative legitimacy, (e) norma-

strong communicators of desired behavior (Lawler 1987).

tive legitimacy, and (f) cognitive legitimacy. According to control theory, punishment influences and

H5: The employee’s perceptions of the (a) regulative legitimacy, shapes employee behavior (Jaworski 1988). Indeed,

(b) normative legitimacy, and (c) cognitive legitimacy of employees’ punishment expectations have been linked to

the request are related positively to his or her likelihood of reduction in various negative behaviors, such as software

complying (i.e., his or her compliance outcome). piracy, computer abuse, and Internet misuse (Liao et al.

2010; Peace, Galletta, and Thong 2003; Straub 1990).

Organizational Factors H6b: There is a positive relationship between an employee’s

In addition to employees’ personal evaluative beliefs expectations of punishment from complying with a fuzzy

regarding the customer and the request, the organization’s request and his or her likelihood of complying with the

request (i.e., his or her compliance outcome).

formal and informal control systems also affect the

employee’s motivations and behaviors. An organization’s As two interrelated aspects of a service encounter, com-

formal control system is defined as the written procedures pliance outcome and process should also be interdependent.

and policies that direct employee behavior to achieve the From the event order perspective, employees may be likely

organization’s goals and/or detect misconduct (Leatherwood to decide on their compliance outcome (i.e., to what extent

and Lee 1991), whereas an informal system molds employee customer expectations will be met) before they engage in

behavior through common values, beliefs, and traditions the process of compliance. This also follows according to

(Ouchi 1980). The informal control system allows employees self-perception theory (Bem 1967). Therefore, we add a

to develop responses to customers according to a maze of link from compliance outcome to process in the model.

unspoken and/or unwritten rules existing in the organization. Because it is not particularly interesting, this link is a con-

Our qualitative research uncovered both types of orga- trol relationship.

nizational control mechanisms. In particular, the employee’s

perceptions of the firm’s norms of flexibility are part of the Moderating Effects of Employee Gender and

informal control system, while expectations of punishment Organizational Tenure

(for going outside company policy) are part of the formal The preceding discussion presents a set of linear relation-

control system. Interestingly, this organizational classifica- ships to aid in predicting employees’ compliance behavior

tion echoes Homburg and Furst’s (2005) ideas of mechanis- with a fuzzy request. To enhance the managerial implica-

tic versus organic. The expectation of punishment repre- tions of this study, we address two highly relevant and

sents the mechanical guidelines, while the employee’s actionable moderators, employee gender and organizational

perceptions of flexibility provide the organic environment tenure, of some of the previously mentioned relationships.

with regard to the employee’s responses. Employee gender. Researchers often find gender differ-

Perceived norm of flexibility. The norm of flexibility ences in organizational settings, especially for service

involves a management style that gives employees the dis- employees (e.g., Babin and Boles 1998; Iacobucci and

cretion to make day-to-day or case-by-case decisions about Ostrom 1993). Employee gender influences how they inter-

job-related activities (Heide and John 1992) and relates to act with customers, as well as their development and main-

employee empowerment (Bowen and Lawler 1992). tenance of customer relationships (e.g., Fiske and Stevens

Whereas previous researchers have addressed the influence 1993; Iacobucci and Ostrom 1993). The most resilient sex

of empowerment on employee behavior (e.g., Hartline and role difference is a gender-based difference in schema in

Ferrell 1996), we focus on the perceived norm of flexibility which men and women evaluate their own behaviors to reg-

to capture employees’ perceptions of how much freedom ulate their attitudes and behaviors (Bem 1981). Men tend to

they believe they have in handling customer requests day to be assertive, task oriented, dominating, and authoritative

day, including fuzzy return requests. Chebat and Kollias and exhibit independent construal; women tend to be pas-

(2000) note that the increased discretion and flexibility sive, relationship oriented, submissive, and noncompetitive

derived from more empowerment is positively associated (e.g., Fiske and Stevens 1993). Moreover, women tend to

with an employee’s confidence in serving customers. Thus, maintain and nurture the interpersonal aspects of their rela-

employees who believe that they have more flexibility in tionships more than men and attempt to avoid conflicts

their jobs are more likely to comply with fuzzy requests. (Babin and Boles 1998). These sex role differences will

produce differential weights for some antecedents for male

H6a: There is a positive relationship between an employee’s versus female employees’ with regard to their compliance

perceived flexibility in handling customer requests and process and outcome.

his or her likelihood of complying with the fuzzy request

(i.e., his or her compliance outcome). H7a: The relationship between CA and employees’ friendliness

and effort in handling the fuzzy request (i.e., compliance

Expectations of punishment. Deterrence theory (Tittle process behaviors) is stronger for female employees than

1980) posits that as punishment certainty and punishment for male employees.

74 / Journal of Marketing, November 2012

Furthermore, meta-analytic evidence (e.g., Taylor and pliance process behaviors) is stronger for longer-tenure

Hall 1982) suggests gender differences in the saliency of employees than for shorter-tenure employees.

instrumentality in decision-making processes; that is, society H8b: The relationship between CA and an employee’s friendli-

socializes men to value the outcome, focusing more on instru- ness and effort in handling the fuzzy request (i.e., com-

mental behaviors and impersonal tasks and goals (Baird 1976; pliance process behaviors) is stronger for longer-tenure

employees than for shorter-tenure employees.

Rotter and Portugal 1969). In contrast, women tend to focus

on the method used to accomplish a task, suggesting a In addition, as we reasoned previously, longer-tenured

greater process orientation (Hennig and Jardim 1977; employees should have larger resource endowments. These

Iacobucci and Ostrom 1993). Thus, the echoing effect of the endowments should enable them to engage in a more delib-

customer’s affiliative style may have a stronger effect on erate reasoning process (producing greater motivated rea-

what the employee focuses on most (i.e., process for women soning) than shorter-term employees. Thus:

and outcome for men), leading to the following hypotheses:

H7b: Female employees’ perception of the customer’s affilia- H8: The perception of the customer’s dominant style is related

tive style is related more strongly to their friendliness and more strongly to the employee’s perceptions of the

effort in handling the fuzzy request (i.e., compliance request’s (c) regulative legitimacy, (d) normative legiti-

process behaviors) than male employees’ perceptions. macy, and (e) cognitive legitimacy for longer-tenure

employees than for shorter-tenure employees.

H7c: Male employees’ perception of the customer’s affiliative

style is related more strongly to their likelihood to com-

ply with the fuzzy request (i.e., compliance outcome) Control Variables

than female employees’ perceptions.

We exercise caution with regard to possible spurious and

In addition, known gender differences involving com- attenuating variables that could influence our proposed rela-

munication styles suggest that men tend to demonstrate tionships by incorporating several relevant covariates.

visual dominance and ignore communications of others These covariates include employee demographics (age and

more so than women (e.g., Dovidio et al. 1988). Thus, male education), two company variables (type of retailer and

employees are more likely to engage in dominant styles amount of returns training), and presence versus absence of

themselves, which do not complement customers’ dominant supervisor during the encounter.

styles. Therefore, compared with women, men may react

more negatively and strongly to a customer acting in a dom- Method

inant manner (i.e., butting heads with the employee), thus

causing the male employee to engage in greater motivated Sample

reasoning to decline the request.

The sample consists of employees whose job duties include

H7(d–f): The employee’s perceptions of the customer’s domi- handling customer returns in the retail industry in the

nant style is related more strongly to the employee’s United States. We tested our conceptual framework in the

perceptions of the request’s (d) regulative legitimacy,

context of retail returns because of the ubiquity and rele-

(e) normative legitimacy, and (f) cognitive legitimacy

for male than for female employees. vance of fuzzy requests in retail return encounters; how-

ever, the model could have broad applicability to fuzzy

Organizational tenure. “Organizational tenure” refers to requests beyond a returns situation.

the length of time that an individual employee has worked The researchers recruited a web panel provided by

for the organization. A study of fraudulent consumers Qualtrics, an online survey hosting company that maintains

reports that customers intentionally choose to return items an online panel of approximately 53,000 retail employees in

to younger employees because they believe that they are the United States from all 50 states. For the current study,

less knowledgeable about return policies, less experienced, Qualtrics randomly selected more than 3000 of these pan-

and thus more accommodating to these requests (Harris elists and invited them to answer the first screening ques-

2010). Indeed, previous studies have shown that longer- tion: “Are you currently employed by a retailing company?”

tenured employees have more learning and practice oppor- One thousand sixty-six panelists responded “yes” to this

tunities to engage in serving customers as job-related question. A second question asked, “Is it part of your job to

knowledge increases (Schmidt, Hunter, and Outerbridge handle customer returns?” to which 811 panelists responded

1986). Such improved capacity may enhance their motiva- “yes” and proceeded to the survey. Following the current

tions for customer-oriented tasks, such as organizational cit- best practices of preventing respondent cheating in online

izenship behaviors (e.g., helping customers and making surveys (Rogers and Michael 2009), we dropped 369

constructive suggestions), as evidenced by a recent meta- respondents (i.e., did not allow them to continue responding

analysis (Ng and Feldman 2010). Therefore, longer-tenured to survey questions and eliminated all their answers) due to

employees, who need fewer cognitive resources to perform careless responding to the first attention-checking question,

their jobs, may have more resources available to initiate and we dropped 31 more with the second attention-checking

their own actions and to engage in greater discretionary question. Thus, the final sample included 411 respondents.

efforts (e.g., Wang et al. 2011).Therefore, we hypothesize A wide variety of retailer types appear in the responses

the following: provided by respondents, from image department stores

H8a: The relationship between CO and an employee’s friendli- (23%) to specialty stores (15%), covering almost every cate-

ness and effort in handling the fuzzy request (i.e., com- gory of retailer. The respondents’ job titles were as follows:

Customers’ Fuzzy Return Requests / 75

51% of respondents were sales associates/representatives, methodology used in the main study.2 We used or adapted

35% were managers or supervisors, and the rest did not established scales whenever possible with items and

indicate their position in the company. Approximately 30% sources identified in Appendix B.

of respondents worked less than 30 hours a week (i.e., part- All items contain multiple statements with one excep-

time), and the rest worked full-time. The sample is skewed tion: A single item assesses compliance outcome, or the

in gender (69% female) due to the retail employment real- degree to which the employee believed that he or she met

ity. All age categories (approximately half younger than 40 the customer’s expectations. In this case, a single item is

years old), ethnicity (86% Caucasians), and education lev- justified because the concept is concrete and represents the

els (49% with some college education) are well represented idea well (Bergkvist and Rossiter 2007).

and similar to recent retail statistics (U.S. Census Bureau Recall that the sample involves two groups, those who

2010). With regard to job tenure, 63% had worked for their accepted the return and those who did not.3 Thus, we

current retail firm for fewer than five years, while the rest checked the covariance and structural equivalence before

had worked for the firm for more than five years. pooling the two subsamples for model testing. Following

To aid respondents in identifying a past incident fitting Steenkamp and Baumgartner (1998), we first evaluated the

a fuzzy return request, we presented explanations of three invariance of the factor loadings, factor variances, and

categories of customer return requests to the respondents. covariances across the two groups, finding evidence for the

They included the following: (1) returns that clearly fit equality of the covariances of the two subsamples.4 We then

within the store’s return policy, (2) completely unacceptable evaluated the path coefficient equivalence by comparing the

or fraudulent returns, and (3) somewhat outside the store’s free-estimated model against an equal path coefficient

return policy (e.g., a week or two past the return deadline, model in which the subsamples are forced to have equal

within the return period but without receipt). We then asked path coefficients, as hypothesized in the model. Finding no

respondents to assess the percentage of times they believed significant chi-square change (2(15) = 23.29, p = .08)

that the return requests they received belonged to each of suggests that the measures of the focal constructs and their

these categories. More than one-third of our respondents relationships are not substantively different between the

indicated that more than 20% of the returns they handle fit subsamples, allowing us to pool groups.

into this third category (i.e., “somewhat outside the store’s 2We conducted pretesting with an online survey using Qualtrics

return policy”), exemplifying the relevance of this topic.

with the goals of item reduction and scale purification. Students in

We then asked respondents to recall a recent, memo- several upper-level undergraduate marketing classes at two south-

rable incident falling into this third category (i.e., a fuzzy eastern universities earned extra credit by recruiting nonstudent

return request). To generate variance of the dependent participants for our online survey. We subjected items to exploratory

variable (compliance behavior), we randomly assigned half and confirmatory factor analyses to initially reduce the item pool.

3As we expected, the “accept” group report higher mean com-

the respondents to recall a fuzzy return incident in which

pliance outcome scores (i.e., the extent to which the employee met

they accepted the return, while we asked the other half to the customer’s expectations on a five-point scale; see Appendix A)

recall a fuzzy return in which they did not take back the than that reported by the “not accept” group (4.11 vs. 3.14, p <

item. Researchers typically use this approach in critical .001). However, we found no other contextual and employee dif-

incident technique studies to obtain a broad range of situa- ferences on the basis of t-tests between the groups.

tions (e.g., Bitner, Booms, and Mohr 1994; Holloway and 4We first estimated a baseline measurement model assuming the

Beatty 2008). To aid in more vivid recall, respondents same pattern of fixed and free parameters across the two subsam-

ples. This model fit the data well (2 = 1122.66, d.f. = 760; com-

described the reason for the return, price of the returned parative fit index [CFI] = .97, nonnormed fit index [NNFI] = .96,

item, and time the incident occurred. The top three cate- and root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] = .048).

gories of inappropriate customer return requests were “no Next, we estimated a model that constrained the factor loadings to

receipt” (22%), “beyond the return period” (20%), and “box/ be invariant across groups and found the fit indexes for this model

packaging opened or missing” (10%). In terms of the item to be acceptable (2 = 1149.71, d.f. = 780; CFI = .97; NNFI = .96;

value involved, 35% were valued at less than $25, 26% and RMSEA = .048), with the difference in fit between this model

and the baseline measurement model insignificant (2 = 27.05,

were $25–$50, 20% were $51–$100, and the rest were d.f. = 20, p = .13). Thus, the loadings for all measurement items

higher than $100. With regard to recency, 53% reported that were invariant across samples. The third model estimated specified

the incident had occurred in the past month, 25% of the invariant factor variance and covariances in addition to invariant

incidents occurred in the past one to three months, and the factor loadings. It has acceptable fit indexes (2 = 1188.91, d.f. =

rest more than three months previously. Respondents had 845; CFI = .96; NNFI = .96; and RMSEA = .051), and the differ-

no difficulty recalling such a return request incident. ence in fit between this model and the invariant factor model is not

significant (2 = 39.20, d.f. = 65, p = .99). Thus, all correlational

Measures (covariance) relationships among model constructs, as well as

construct (factor) variances, are equal across samples. Finally, we

Appendix B presents the scales measuring the constructs estimated a fully invariant measurement model (i.e., invariant fac-

central to the study. We achieved content validity through tor loadings, invariant factor variance and covariances, and invari-

an extensive literature search and a thorough analysis of ant item error loadings). Although the indexes indicate adequate fit

(2 = 1447.68, d.f. = 875; CFI = .957; NNFI = .95; and RMSEA =

interview scripts, which allowed us to define the domains of

.057), this model’s fit differed from the fit of the covariances’

constructs of interest and to generate the items. In addition, a measurement model (2 = 258.77, d.f. = 30, p < .001). Still, the

pretest with a convenience sample of retail employees (N = invariance of the factor loadings, factor variances, and covariances

430) provided a thorough assessment of the scales and suggest that pooling the two subsamples is appropriate.

76 / Journal of Marketing, November 2012

As Bagozzi and Heatherton(1994) suggest, when deal- tomer and the employee (Crosby, Evans, and Cowles 1990)

ing with a large number of scales and items, large scales can (Cronbach’s = .89) and selected the lowest positive corre-

be disaggregated into subscales and the composites of the lation (r = .01) between the MV and other variables to adjust

subscales treated as indicators. Thus, we conceptualize the construct correlations and statistical significance (Lindell

compliance process, composed of employee effort and and Whitney 2001). None of the significant correlations

friendliness, as a higher-order factor. Treating the compli- became insignificant after the adjustment (see Table 1), indi-

ance process as second-order constructs is justifiable con- cating that common method bias is not a serious concern here.

ceptually. First, compliance process is a superordinate con- Covariates. To account for the potential impact of

cept, meaning it is a general concept manifested by its variables not identified in our model on our hypothesized

subdimensions. Moreover, aggregating its subdimensions in relationships, we first regressed all dependent variables

our second-order model also matches its levels of abstrac- (including compliance process, compliance outcome, and

tion with the other concepts in the model (Edwards 2001).5 three aspects of legitimacy) in our model on the covariates

Next, we subjected all measures, including the second- mentioned previously, obtained the residuals (i.e., the items

order construct, to confirmatory factor analyses to assess their with covariate effects parceled out), and used these residu-

psychometric properties; the results indicate a good model als to test our model. Other researchers have adopted this

fit (2 = 721.85, d.f. = 380, p < .01; CFI = .97; NNFI = .97; method in the past (e.g., Ahearne, Bhattachary, and Gruen

and RMSEA = .047). Construct reliability and average vari- 2005). The results and conclusions remain largely

ance extracted were strong for all latent variables (see unchanged, regardless of whether we control for covariates.

Appendix B). In addition, all constructs achieved discriminant The results in Table 2 and subsequent analyses use the

validity as assessed with the variance-extracted test (Fornell residuals of focal constructs in the analysis.

and Larcker 1981). In this test, we compared the variance-

Test of Hypotheses: Main Effects

extracted estimates for the two constructs of interest with

the square of the correlation between the two constructs. Table 1 provides pairwise correlations and descriptive sta-

Two constructs have discriminant validity if their variance- tistics of our main constructs. We derived the full structural

extracted estimates are greater than their squared correlations. model from our hypotheses using the conceptual model pre-

sented in Figure 1. Table 2 presents the standardized path

Common method bias. To assess the potential for common coefficients for all relationships in the structural model. As

method bias, we applied the marker variable (MV) method Table 2 shows, our data support the proposed model (2 =

and used a scale theoretically unrelated to at least one scale 899.35, d.f. = 407, p < .01; CFI = .96; NNFI = .96; and

in the analysis as the MV, which offers a proxy for common RMSEA = .054). The hypothesized model explains 43.6% of

method variance (Lindell and Whitney 2001). We used a the variance in the current compliance process and 44.9%

three-item scale that measured the similarity between the cus- of the compliance outcome variance. Although the negative

impact of expectations of punishment on compliance out-

5Following Hair et al.’s (2009) criterion, we ran a separate con-

come did not materialize (H6b), the analyses support the

firmatory factor analysis second-order model; this model showed other main effect hypotheses.

superior predictive validity over the lower-order factor model.

Compared with the lower-order factor model, the second-order

In addition, to test the hypothesized nonsignificant

model for compliance process (2 = 120.83, d.f. = 72, p < .05) fit effects of the customer’s affiliative interaction style on

the data better; therefore, the subsequent structural model uses the employees’ perceptions of the legitimacy of the request, we

second-order measurement model for compliance process. ran a new structural equation model adding paths from affil-

TABlE 1

Correlations and Descriptive Statistics

Variables 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

1. Compliance process .76 .12** .04 .02 –.05 –.01 –.02 .09 .04 .44 .32**

2. Compliance outcome .13** — .36** –.40** .33** .46** .40** .24** –.18** .06 –.02

3. Affiliation .05 .37** .96 –.65** .16** .33** .45** .06 –.09 .00 –.07

4. Dominance .03 –.39** –.63** .89 –.23** –.42** –.48** –.05 .05 .07 .07

5. Regulative legitimacy –.04 .34** .17** –.22** .93 .32 .17** .00 .08 –.18** –.10

6. Normative legitimacy .01 .47** .34** –.41** .33** .89 .61** .00 .00 –.05 –.11*

7. Cognitive legitimacy –.01 .41** .46** –.47** .18** .61** .88 –.04 .02 .00 –.06

8. Norm of flexibility .10 .25** .07 –.04 .01 .01 –.03 .88 –.40** .16** .17**

9. Expectations of punishment .05 –.17** –.08 .06 .09 .01 .03 –.39** .96 –.03 .08

10. Customer orientation .45** .07 .01 .08 –.17** –.04 .01 .17** –.02 .90 .42**

11. Conflict avoidance .33** –.01 –.06 .08 –.09 –.10* –.05 .18** .09 .43** .87

12. MV (fairness) –.11* –.10* –.03 –.01 .05 .09 .01 –.34** .23** –.23** –.18**

M 5.71 3.62 4.47 4.26 2.49 2.68 2.98 4.97 3.94 6.34 5.65

SD .84 1.41 1.72 1.62 1.52 1.24 1.19 1.35 1.78 .81 1.07

*p < .05.

**p < .01.

Notes: Zero-order correlations are below the diagonal; adjusted correlations for potential common method variances (Lindell and Whitney

2001) are above the diagonal. Bold numbers in the diagonal are average variance extracted for constructs.

Customers’ Fuzzy Return Requests / 77

TABlE 2

Results of Hypothesized Relationships

Main Model Organizational Tenure Moderations

78 / Journal of Marketing, November 2012

Gender Moderations

Standardized Shorter longer

Estimate Male Female (N = 177; (N = 234;

Hypothesized Relationships (t-Value) (N = 127) (N = 284) 2(1) ≤3 Years) >3 Years) 2(1)

H1a: CO Æ compliance process .52 (7.71)** H8a .46 .63 10.33**

H1b: CA Æ compliance process .19 (2.85)** H7a –.11 n.s. .39 7.42** H8b .13 .20 n.s.

H2: Affiliation Æ compliance process .16 (3.09)** H7b .18 .17 n.s.

H3: Affiliation Æ compliance outcome .12 (2.44)* H7c .21 –.09 n.s. 4.28*

H4a: Dominance Æ regulative legitimacy –.27 (–5.04)** H7d –.20 –.30 n.s. H8c –.11 –.41 6.98**

H4b: Dominance Æ normative legitimacy –.52 (–10.43)** H7e –.67 –.46 n.s. H8d –.48 –.56 n.s.

H4c: Dominance Æ cognitive legitimacy –.60 (–11.74)** H7f –.81 –.52 4.80* H8e –.65 –.56 n.s.

H5a: Regulative legitimacy Æ compliance outcome .24 (5.40)**

H5b: Normative legitimacy Æ compliance outcome .28 (5.94)**

H5c: Cognitive legitimacy Æ compliance outcome .17 (3.26)**

H6a: Flexibility Æ compliance outcome .21 (4.06)**

H6b: Expectation of punish Æ compliance outcome –.06 (–1.22)

Controlled Path:

Compliance outcome Æ compliance process .23 (4.26)**

2

Main model fit: (407) = 899.35, p < .01; CFI = .96; NNFI = .96; and RMSEA = .054. Squared multiple correlation for compliance outcome: 44.9%; squared multiple correlation

for compliance process: 43.6%.

*p < .05.

**p < .01.

Notes: n.s. = not significant. Supported moderation hypotheses are in boldface.

iation to the three aspects of legitimacy to the primary Gender assessments. To test the gender differences pro-

model. We found that all three paths were insignificant posed, we tested a baseline model in which we freely esti-

(standard path coefficients were .03, –.08, and .11, respec- mated all hypothesized parameters for both men and

tively; p > .10) and that this model does not fit better than women. Table 2 shows separate path estimates for hypothe-

the primary model (2(3) = 1.74, p = .63), in support of sized relationships resulting from this analysis in separate

our “no effect” hypotheses (H4d–f.) columns. We then conducted nested structural equation

models in which we constrained the paths corresponding to

Follow-Up Analyses our proposed links to be equal across men and women.

Furthermore, we performed formal tests of mediation to Table 2 presents the resulting chi-square differences with 1

examine the full mediation roles of three aspects of legiti- degree of freedom between each constrained model and its

macy in the negative impacts of dominance on compliance associated freely estimated model. We applied similar

outcome. All correlation coefficients between dominance multigroup analysis procedures to the tenure variable, in

and the legitimacy elements are positive and significant which we divided tenure groups as previously noted.

(.34, .47, and .41, respectively; p < .01). Following the pro- Consistent with expectations, CA is more strongly asso-

cedures for testing full mediation using structural equation ciated with the compliance process for female than for male

modeling, as Iacobucci, Saldanha, and Deng (2007) suggest, employees (women = .39 vs. men = –.11; 2 = 7.42, p <

we first fit the direct and indirect paths simultaneously to .001), while the effect of customer affiliation on the compli-

estimate both the direct and indirect impacts of dominance ance outcome is stronger for men (men = .21 vs. women =

on compliance outcome. We then computed the z-scores for –.09; 2 = 4.28, p < .05), in support of H7a and H7c. In

the indirect impacts and checked the significance of our addition, the customer’s dominant style is more strongly

direct path coefficients. The direct path coefficient from associated with male employees’ judgments of the request’s

dominance to compliance outcome was not significant, and cognitive legitimacy than with female employees’ judg-

the z scores were significant for all hypothesized full medi- ments (men = –.81 vs. women = –52; 2 = 4.80, p < .01),

ations: dominance Æ regulative legitimacy Æ compliance in support of H7f, but the analysis did not reveal differences

outcome, dominance Æ normative legitimacy Æ compliance regarding regulative and normative legitimacy (providing

outcome, and dominance Æ cognitive legitimacy Æ com- no support for H7d and H7e).

pliance outcome. Thus, the analyses support the hypothe- Tenure assessments. Finally, a stronger association

sized full mediation role of legitimacy in the links from between employees’ CO and their compliance process

dominance to compliance outcome, in accordance with exists (longer = .63 vs. shorter = .46; 2 = 10.33, p < .001)

motivated reasoning theory. Finally, Sobel tests confirm and between customer dominance and regulative legitimacy

mediation by showing the significant indirect impact of (longer = –.41 vs. shorter = –.11; 2 = 6.98, p < .01) for

dominance on compliance outcome through regulative longer-tenure employees versus those with less tenure, in

legitimacy, normative legitimacy, and cognitive legitimacy support of both H8a and H8c. However, the proposed tenure

(z-scores were 3.68, 5.16, and 3.14, respectively). differences between the employees’ CA and their compli-

ance process and the effect of customer dominance on cog-

Tests of Moderation Effects

nitive and normative legitimacy did not materialize, provid-

Invariance assessment. Before conducting multigroup ing no support for H8b, H8d, and H8e.

analyses, we first tested whether the measures were invari-

ant across male (N = 127) and female (N = 284) employees

by estimating a hierarchy of multigroup measurement Discussion

invariance models (Steenkamp and Baumgartner 1998). We

carried out a similar procedure for the shorter-tenured Summary of Findings and Academic Contribution

groups (N = 177 with no more than three years of organiza- The current study is a first attempt at addressing the

tional tenure) versus longer-tenured groups (N = 234 with employee decision-making process when facing customers’

more than three years of organizational tenure). Our analy- fuzzy return requests. From a theory-building perspective,

ses support invariance across the groups, allowing for the this study contributes to the literature by fully modeling

subsequent moderation assessments.6 important antecedents to employees’ compliance process

6The first model estimated was a baseline measurement model RMSEA = .047), and the difference in fit between this model and

of the same pattern of fixed and free parameters. This model fit the the invariant factor model is not significant (2 = 47.64, d.f. =

data well (2 = 1163.35, d.f. = 760; CFI = .97; NNFI = .96; and 65, p = .95). Thus, all correlational (covariance) relationships

RMSEA = .051). Next, we estimated a model that constrained the among model constructs, as well as construct (factor) variances,

factor loadings to be invariant across groups and found the fit are equal across samples. Finally, we estimated a fully invariant

indexes for this model to be acceptable (2 = 1182.75, d.f. = 780; measurement model (i.e., invariant factor loadings, invariant fac-

CFI = .97; NNFI = .96; and RMSEA =.050) and the difference in tor variance and covariances, and invariant item error loadings).

fit between this model and the baseline measurement model to be Although the indexes indicate adequate fit (2 = 1313.39, d.f. =

insignificant (2 = 19.4, d.f. = 20, p = .50). Thus, the loadings for 875; CFI = .967, NNFI = .96, and RMSEA = .049), this model’s fit

all measurement items are invariant across samples. The third differs from the fit of the baseline measurement model (2 =

model estimated specified invariant factor variance and covari- 83.0, d.f. = 30, p < .01). Still, the invariance of the factor loadings,

ances in addition to invariant factor loadings. It has acceptable fit factor variances, and covariances suggest that comparing model

indexes (2 = 1230.39, d.f. = 845; CFI = .96; NNFI = .96; and paths across samples is appropriate.

Customers’ Fuzzy Return Requests / 79

behaviors and outcome decisions, including customer, suggesting that men may rely more heavily on motivated

request, employee, and organizational factors. Specifically, reasoning in assessing the request’s cognitive legitimacy,

the analyses support the positive influence of employee CO while their reported compliance outcome choices were more

and CA on employee’s compliance process behaviors, positively affected by the customers’ affiliation style (due to

including friendliness and effort, suggesting the important emotional contagion). Thus, notably, customers’ interaction

role of these individual difference variables. In addition, the styles generally influenced men more than women in their

positive influence of customers’ affiliative style on employee decision making. In contrast, CA had a lower effect on men

reactions (relative to both process and outcome) to fuzzy than women with regard to providing a friendlier, more

return requests indicates that indeed liking begets liking, effortful treatment of customers. Such rich contingency

with positive emotions being contagious or echoed back. views of employee gender differences in the presence of

However, when customers exhibit a dominant style, it fuzzy requests offer valuable management implications.

appears to trigger the employee to engage in a motivated In addition, the findings indicate that longer-tenured

reasoning process, with the employee adopting a defensive employees, who need fewer mental resources to engage in

stance and judging the customer’s request to be less legiti- typical task behaviors (given their past practice), have more

mate, thereby reducing his or her likelihood to comply with resources left over to act on their own volition than those

the request. This strong and consistent finding, across all with a shorter organizational tenure. For example, employ-

three types of legitimacy, extends the field’s understanding of ees with longer tenure (vs. shorter tenure) relied more on

employee decision making in customer–employee encoun- their own CO in handling the request (i.e., the process).

ters beyond what emotional contagion theory suggests— Furthermore, a customer’s dominant style had a stronger

namely, that the echoing mechanism primarily operates effect on their assessment of the regulative legitimacy of the

(i.e., customers’ interaction styles directly affect employ- claims. This first finding is similar to Wang et al.’s (2011)

ees’ reactions to the customers). finding that longer-tenured employees allocate more

We also find strong support for the three aspects of per- resources to regulate their service-related emotions and

ceived legitimacy in predicting employees’ compliance out- behaviors in the face of negative customer behaviors.

come choices, which fits with script theory. In addition to Notably, the stronger influence of the dominant customer

assessing the degree to which a fuzzy request violates com- style in our study extends the field’s understanding of

pany rules (regulatory legitimacy), employees also use social employees’ reactions to negative customer behaviors by

norms (i.e., normative legitimacy) and cognitive sense-making showing how longer-tenured employees surreptitiously

(cognitive legitimacy) to judge these requests. Our study achieve their goal of punishing the offending customer (by

provides a more complete picture of this relationship than reinterpreting their view of the situation).7

those offered in previous studies of legitimacy and returns.

In this study, employees’ feelings of empowerment Managerial Implications

(assessed by perceived flexibility) influenced compliance The frequency of fuzzy returns and the percentage of accep-

outcomes as expected, while employees’ expectations of tance of such returns reported by our national sample of

punishment did not affect outcome decisions. This lack of retail employees indicate the significance of this neglected

effect may have occurred because employees believed that phenomenon. While 36% of the respondents indicated that

punishment was not relevant in these types of return situa- at least 20% of their returns belong in this fuzzy request

tions; that is, perhaps they believed they could safely bend category, they chose to accept these types of returns on

the rules with these generally inexpensive return requests or average 48% of the time. Moreover, the importance of this

even that it was worth the risk to treat the customer fairly issue is reflected by the degree to which firms embrace giv-

(e.g., Kennedy and Corliss 2008). ing employees empowerment and flexibility in their jobs

Not only do we offer conceptual and empirical support (e.g., Ritz-Carlton allows its employees to spend up to

for the separation of compliance outcome and process $2,000 to solve a customer’s problem (Michel, Bowen, and

behaviors in this study, we also predict and find a different Johnston 2008). It is evident that employees deal with these

set of antecedents for each. We find that the compliance types of requests and decisions relative to them on an

process, which is more discretionary, is mainly influenced almost daily basis. Employee decisions about whether to

by interpersonal factors (i.e., the customer and the break the rules and how to handle these issues diplomati-

employee factors), while the outcome, a more scripted cally can have a large impact on customer satisfaction, loy-

activity, is influenced by factors pertinent to multiple role alty, and, ultimately, the bottom line. Thus, our findings

senders, including a customer factor (affiliation), a request indicate several important managerial implications.

factor (legitimacy), and an organizational factor (norm of

flexibility). Therefore, this nuanced view of employee 7To exclude the possible confounding effects of longer-term

behaviors enhances the managerial relevance of this study. employees tending to hold supervisory positions, we compared all

Moreover, this work contributes to the service marketing the five differentiated impacts across employees with supervisor

literature by showing that the antecedents of employees’ com- title (N = 133) with those without supervisor title (N = 101) for

pliance outcome and employee process weigh differently for those with more than three years of tenure. We conducted a nested

structural equation model comparison to test whether the relation-

male versus female employees, as well as for employees

ship strengths of the five moderations differ across the supervisor

with shorter versus longer organizational tenure. In particular, and nonsupervisor subgroups. The results indicate that the find-

male employees in our study were more negatively affected ings noted here were not driven by whether the longer-term

by their customers’ dominant style than female employees, employee was a supervisor.

80 / Journal of Marketing, November 2012

First, service firms should recognize that several factors seem to have little impact on employee’s decision making

influence employees’ on-the-spot compliance behaviors relative to these fuzzy requests. Thus, reliance on informal

other than the objective aspects of the requests. Thus, ser- control systems, such as empowerment and flexibility, is likely

vice firms should ensure that the job designs and job to net more positive benefits than more formal control systems.

descriptions of frontline employees accurately reflect what

management wants to accomplish relative to fuzzy requests. Limitations and Directions for Further Research

If employees do not clearly know when and how to imple- Although our study’s cognitive focus is consistent with

ment (or bend) the firm’s policies and procedures, manage- research in social psychology, which indicates that a rational-

ment should train employees in this area. Furthermore, firms cognitive level of analysis explains behavior better than emo-

must understand the types of fuzzy requests employees are tions (Rabinowitz, Karuza and Zevon 1984), the main and

likely to encounter to identify acceptable deviations from interaction effects of employees’ affective or subjective reac-

the rules, as well as to provide ways to help employees tions to fuzzy requests is another fruitful path for exploration.

reject the customer’s claim diplomatically when necessary. Given that frontline employees are emotional laborers

Second, our findings suggest that beyond whether the (Hochschild 1983), further research should investigate the

return violates the rules (regulatory legitimacy), the firm effect that customer requests and employee decision making

should tap into frontline employees’ understanding of nor- relative to these requests have on role ambiguity and role

mative and cognitive legitimacy with regard to these deci- strain, as well as their subsequent effects on employee job

sions. Knowing that employees also attempt to make sense performance and satisfaction (Chung and Schneider 2002).

of the request from social norm (whether it is socially Our model paints the landscape of employee decision

acceptable) and personal norm (whether it is comprehensi- making with regard to customer fuzzy requests without

ble) perspectives suggests that service firms should commu- considering customer reactions to these decisions and

nicate the rationales of the (return) policies from both social process. Further studies should explore customers’ expecta-

logic and sense-making perspectives, as well as provide the tions (e.g., the extent to which they expect the employee to

regulations and rules to follow. break the rules and what criteria they use to develop expec-

The strong effect of the customer’s dominant style on all tations), as well as their reactions to employee compliance

three forms of legitimacy suggests that employees need addi- process and outcome in these situations. Moreover, we do

tional training aimed at not letting their subjective and negative not know the veracity of these retrospective self-reports;

feelings toward a customer’s approach affect their objective customers may have a different perspective on the incident.

assessment of the return’s legitimacy. The strong association Thus, conducting dyadic research could be fruitful.

of CO and CA with employees’ compliance process behav- Our findings should be applicable to other customer–

iors provides insights for training and hiring. That is, even if employee return or complaint situations, as well as to other

the employee cannot comply, he or she can make the process customer request encounters. However, further study is

less painful for the customer. Moreover, this positive treatment needed to establish that claim because retail returns are a

seems enhanced for longer-term employees because they rely unique type of customer request. For example, they fall within

more on CO and for women because they desire to avoid the typical job scope of the employee, while often customer

conflicts. These findings suggest the importance of hiring requests do not fall within this scope (e.g., when a customer

people with high CO (or training for that characteristic) to asks an employee to do something completely unrelated to

reduce the sting of refusing a customer’s return request. his or her job). In addition, our findings rely heavily on self-

With regard to hiring people with greater CA, this reported retrospectives of employees, which may involve

should be done cautiously, considering that the positive role inaccurate recall. Although we took precautions to reduce

of CA in the compliance process was only relevant for social desirability and other biases, it would be worthwhile

female (not male) employees. Moreover, female employees for researchers to use scenario-based and field experiments.

reported delivering compliance more positively than male Employees’ decisions to comply with fuzzy requests

employees (5.78 vs. 5.55, p < .01). These findings suggest have ethical or moral implications; excessively complying