Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Synchronous Colorectal Cancers: A Review of Clinical Features, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prognosis

Synchronous Colorectal Cancers: A Review of Clinical Features, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prognosis

Uploaded by

Antonio GligorievskiCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- LMCC CDM Sample QuestionsDocument22 pagesLMCC CDM Sample Questionsaaycee100% (2)

- Blood TransfusionDocument59 pagesBlood Transfusionpranalika .................76% (17)

- Health Informatics in The PhilippinesDocument2 pagesHealth Informatics in The PhilippinesLianefhel S. Del RosarioNo ratings yet

- Atlas of Endoscopy With NBIDocument351 pagesAtlas of Endoscopy With NBICosmin Gabriel CristeaNo ratings yet

- Molluscum MedscapeDocument35 pagesMolluscum MedscapeAninditaNo ratings yet

- Metanalisis 2010Document11 pagesMetanalisis 2010Elmer chavezNo ratings yet

- s10151 021 02436 5Document10 pagess10151 021 02436 5Ottofianus Alvedo Hewick KalangiNo ratings yet

- Prentice Et Al. - 2018 - Malignant Ureteric Obstruction Decompression HowDocument11 pagesPrentice Et Al. - 2018 - Malignant Ureteric Obstruction Decompression HowAli SlimaniNo ratings yet

- Loop Vs DividedDocument8 pagesLoop Vs DividedNatalindah Jokiem Woecandra T. D.No ratings yet

- WarshawDocument11 pagesWarshawJuan RamirezNo ratings yet

- Fonc 09 00597Document13 pagesFonc 09 00597Giann PersonaNo ratings yet

- Journal Pone 0255835Document11 pagesJournal Pone 0255835Great CoassNo ratings yet

- Percutaneous Needle Aspiration Versus Catheter Drainage in Treating Hepatic AbscessDocument8 pagesPercutaneous Needle Aspiration Versus Catheter Drainage in Treating Hepatic AbscessRatna TriasnawatiNo ratings yet

- Soft Tissue Sarcoma Asia-PasificDocument13 pagesSoft Tissue Sarcoma Asia-PasificHayyu F RachmadhanNo ratings yet

- MedicinaDocument23 pagesMedicinametadesyana1No ratings yet

- Research Article: Characteristics of Patients With Colonic Polyps Requiring Segmental ResectionDocument7 pagesResearch Article: Characteristics of Patients With Colonic Polyps Requiring Segmental ResectionAkiko Syawalidhany TahirNo ratings yet

- Tanaka 2012Document15 pagesTanaka 2012Veronica Rahayu FsNo ratings yet

- Articulo - Mapeo Ecográfico Preoperatorio Antes de La Fístula ArteriovenosaDocument12 pagesArticulo - Mapeo Ecográfico Preoperatorio Antes de La Fístula ArteriovenosaDidier Javier DuránNo ratings yet

- Learning The Nodal Stations in The AbdomenDocument9 pagesLearning The Nodal Stations in The Abdomentufis02No ratings yet

- Pancreatology: Review ArticleDocument15 pagesPancreatology: Review ArticleRociio Del Carmen GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Shan 2018Document4 pagesShan 2018pancholin_9No ratings yet

- Consenso Italiano PA SeveraDocument70 pagesConsenso Italiano PA SeveraFabrizzio BardalesNo ratings yet

- CT Based Delineation of Organs at Risk in The Head and Neck RegionDocument7 pagesCT Based Delineation of Organs at Risk in The Head and Neck RegionshokoNo ratings yet

- EJSO OTOASORTrial2017Document9 pagesEJSO OTOASORTrial2017akayaNo ratings yet

- Management and Recurrence of Keratocystic Odontogenic Tumor: A Systematic ReviewDocument6 pagesManagement and Recurrence of Keratocystic Odontogenic Tumor: A Systematic ReviewRonal RonNo ratings yet

- 26Li-2019-Leveraging Latent Dirichlet AllocationDocument15 pages26Li-2019-Leveraging Latent Dirichlet AllocationRODRIGO FERNANDO PAUCAR RECALDENo ratings yet

- Long-Term Effects of Everolimus-Facilitated Tacrolimus Reduction in Living-Donor Liver Transplant Recipients With Hepatocellular CarcinomaDocument13 pagesLong-Term Effects of Everolimus-Facilitated Tacrolimus Reduction in Living-Donor Liver Transplant Recipients With Hepatocellular CarcinomaanonNo ratings yet

- ESWL For CholelithiasisDocument25 pagesESWL For CholelithiasisKhildaZakiyyahSa'adahNo ratings yet

- Meta 5 - Song S - 2022Document12 pagesMeta 5 - Song S - 2022matheus.verasNo ratings yet

- Nakata 2021Document15 pagesNakata 2021FlaviusNo ratings yet

- Reviews in Basic and Clinical Gastroenterology and HepatologyDocument13 pagesReviews in Basic and Clinical Gastroenterology and HepatologyJesús MoraNo ratings yet

- Journal Pone 0191786Document9 pagesJournal Pone 0191786tonyhawkNo ratings yet

- 10.1007@s00464 020 07698 yDocument11 pages10.1007@s00464 020 07698 yGabriel RangelNo ratings yet

- Laparoscopic Versus Open Radical Cystectomy in Bladder Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Comparative StudiesDocument14 pagesLaparoscopic Versus Open Radical Cystectomy in Bladder Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Comparative StudiesVinko GrubišićNo ratings yet

- Abdi Et Al 2023 Operative Treatment of Tarlov Cysts Outcomes and Predictors of Improvement After Surgery A Series of 97Document8 pagesAbdi Et Al 2023 Operative Treatment of Tarlov Cysts Outcomes and Predictors of Improvement After Surgery A Series of 97jabarin.hNo ratings yet

- Early Detection Oral CDocument13 pagesEarly Detection Oral CMuhammad Ikhsan ChaniagoNo ratings yet

- Baumann 2016 IJROBP Development Validation of Bladder Contouring AtlasDocument9 pagesBaumann 2016 IJROBP Development Validation of Bladder Contouring AtlaszanNo ratings yet

- J Hepato Biliary Pancreat - 2020 - Ando - Clinical Practice Guidelines For Biliary Atresia in Japan A SecondaryDocument7 pagesJ Hepato Biliary Pancreat - 2020 - Ando - Clinical Practice Guidelines For Biliary Atresia in Japan A SecondaryMONICA BRAVONo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0302283815001578 MainDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S0302283815001578 MainyuenkeithNo ratings yet

- Bladder CancerDocument11 pagesBladder CancerRaisa SevenryNo ratings yet

- Wrist Ganglion Treatment - 2015 (Tema 4)Document16 pagesWrist Ganglion Treatment - 2015 (Tema 4)Carlos NoronaNo ratings yet

- Li 2012Document7 pagesLi 2012selvioNo ratings yet

- Systematic Review The Effect of Right Hemicolectom PDFDocument12 pagesSystematic Review The Effect of Right Hemicolectom PDFMarco NunesNo ratings yet

- Journal of Controlled Release: Alexander Wei, Jonathan G. Mehtala, Anil K. PatriDocument11 pagesJournal of Controlled Release: Alexander Wei, Jonathan G. Mehtala, Anil K. Patriprakush_prakushNo ratings yet

- Review Pancreatic CancerDocument7 pagesReview Pancreatic CancerLauburu CrossNo ratings yet

- Conrad Et Al-2017-Journal of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic SciencesDocument14 pagesConrad Et Al-2017-Journal of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic SciencesAndra CiocanNo ratings yet

- 12 Penile Cancer LRDocument38 pages12 Penile Cancer LRhizfisherNo ratings yet

- Selecting The Best Elements From Previous Kidney Tumor Scoring System To Restructure Efficient Predictive Models For Surgery TypeDocument7 pagesSelecting The Best Elements From Previous Kidney Tumor Scoring System To Restructure Efficient Predictive Models For Surgery TypeMuhammad RifkiNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness and Durability of Ureteral TumorDocument4 pagesThe Effectiveness and Durability of Ureteral TumorAli SlimaniNo ratings yet

- Meta 2 - Sofi AA - 2018Document9 pagesMeta 2 - Sofi AA - 2018matheus.verasNo ratings yet

- Gu 2018Document10 pagesGu 2018Dela MedinaNo ratings yet

- Expert Consensus Contouring Guidelines For Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy in Esophageal and Gastroesophageal Junction CancerDocument10 pagesExpert Consensus Contouring Guidelines For Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy in Esophageal and Gastroesophageal Junction CancermarrajoanaNo ratings yet

- 10.1007@s13304 019 00648 XDocument8 pages10.1007@s13304 019 00648 XGabriel RangelNo ratings yet

- Clinical Spotlight Review - Intraoperative Cholangiography - A SAGES PublicationDocument19 pagesClinical Spotlight Review - Intraoperative Cholangiography - A SAGES PublicationMu TelaNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Biliary Anatomy According To Different Classification SystemsDocument8 pagesAn Analysis of Biliary Anatomy According To Different Classification SystemsDiego CadenaNo ratings yet

- Lymph Node Density As A Prognostic Variable in Node Positive Bladder Cancer A Meta-AnalysisDocument10 pagesLymph Node Density As A Prognostic Variable in Node Positive Bladder Cancer A Meta-AnalysisOswaldo MascareñasNo ratings yet

- WJGS 8 376Document7 pagesWJGS 8 376Inamullah FurqanNo ratings yet

- A Meta-Analysis of The Value oDocument18 pagesA Meta-Analysis of The Value osatria divaNo ratings yet

- Primary Duodenal Adenocarcinoma: Mario Solej, Silvia D'Amico, Gabriele Brondino, Marco Ferronato, and Mario NanoDocument8 pagesPrimary Duodenal Adenocarcinoma: Mario Solej, Silvia D'Amico, Gabriele Brondino, Marco Ferronato, and Mario NanoMoises Nuñez VargasNo ratings yet

- Cho Et Al., 2014Document8 pagesCho Et Al., 2014NyomantrianaNo ratings yet

- 2018 SNMMI EANM DMSA Adult GuidelinesDocument11 pages2018 SNMMI EANM DMSA Adult Guidelinesmaliborda11No ratings yet

- ASGE Guideline On The Management of Cholangitis 2021Document29 pagesASGE Guideline On The Management of Cholangitis 2021osamayasser82No ratings yet

- Laparoscopic Gastrectomy for Cancer: Standard Techniques and Clinical EvidencesFrom EverandLaparoscopic Gastrectomy for Cancer: Standard Techniques and Clinical EvidencesSeigo KitanoNo ratings yet

- JRCR - Author & Reviewer Guidelines: Manuscript TemplateDocument8 pagesJRCR - Author & Reviewer Guidelines: Manuscript TemplateAntonio GligorievskiNo ratings yet

- Kjco 14 2 83Document6 pagesKjco 14 2 83Antonio GligorievskiNo ratings yet

- STARD 2015 Flow Diagram PDFDocument1 pageSTARD 2015 Flow Diagram PDFAntonio GligorievskiNo ratings yet

- STARD 2015 Flow DiagramDocument1 pageSTARD 2015 Flow DiagramAntonio GligorievskiNo ratings yet

- Film-Screen Mammography QA: What You Need To Know: ObjectivesDocument13 pagesFilm-Screen Mammography QA: What You Need To Know: ObjectivesAntonio GligorievskiNo ratings yet

- Img 20190521 0001 PDFDocument1 pageImg 20190521 0001 PDFMaelyn FavilaNo ratings yet

- Adult CPR ProcedureDocument3 pagesAdult CPR ProcedureDaniica MacaranasNo ratings yet

- Pe and Health Module - Mapeh 4 2nd SemDocument17 pagesPe and Health Module - Mapeh 4 2nd SemCleofe Sobiaco0% (1)

- Bayi Baru LahirDocument43 pagesBayi Baru LahirBRI KUNo ratings yet

- Dalaodao, Mylen Humss A Reflection PaperDocument1 pageDalaodao, Mylen Humss A Reflection PaperMylen DalaodaoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To EpidemiologyDocument61 pagesIntroduction To Epidemiologycas'perNo ratings yet

- Drug Study ClonidineDocument2 pagesDrug Study ClonidineCezanne CruzNo ratings yet

- Walsh Org Chart MasterDocument3 pagesWalsh Org Chart MasterfatmawatiNo ratings yet

- Intro Neuro MriDocument49 pagesIntro Neuro MriJess RiveraNo ratings yet

- 12 - Ocular Pharmacology - 343 - 64Document37 pages12 - Ocular Pharmacology - 343 - 64ณัฐ มีบุญNo ratings yet

- Ten Paripally1 221113Document52 pagesTen Paripally1 221113Kshitij KumareNo ratings yet

- AFES FINAL Announcement As of 14 SepDocument16 pagesAFES FINAL Announcement As of 14 Sepvanhau24No ratings yet

- ParathyroidDocument24 pagesParathyroidLeonard AcsinteNo ratings yet

- DOLOCAN Dolocem CBD Eczema Cream White Paper - 20190917Document1 pageDOLOCAN Dolocem CBD Eczema Cream White Paper - 20190917Petra MitićNo ratings yet

- EBP PosterDocument1 pageEBP PosterDolani N. AjanakuNo ratings yet

- Gems of Homoepathic Materia Medica J D Patil.01602 2Document6 pagesGems of Homoepathic Materia Medica J D Patil.01602 2Sheetal TingoteNo ratings yet

- Perspective in PharmacyDocument6 pagesPerspective in PharmacyShella Mae Duclayan RingorNo ratings yet

- IMCI Plan C 2013Document51 pagesIMCI Plan C 2013Suhazeli AbdullahNo ratings yet

- Zoonoses 8Document404 pagesZoonoses 8Cagar Irwin Taufan0% (1)

- Specific Criteria Nabl-112 (2012)Document53 pagesSpecific Criteria Nabl-112 (2012)kinnusaraiNo ratings yet

- 10.1177 2192568217717972 PDFDocument4 pages10.1177 2192568217717972 PDFEnrique CalvoNo ratings yet

- DR. NOEL CASUMPANG vs. CORTEJODocument15 pagesDR. NOEL CASUMPANG vs. CORTEJOAngelica de LeonNo ratings yet

- 795 USP Proposed 2019 Revision 2018-05-30Document43 pages795 USP Proposed 2019 Revision 2018-05-30Michael FreudigerNo ratings yet

- PT of The Shoulder PDFDocument573 pagesPT of The Shoulder PDFMuhammad Salman AzimNo ratings yet

- Daftar Pustaka Tumor WilmsDocument2 pagesDaftar Pustaka Tumor WilmshariyatiNo ratings yet

- Hemmingsen-2021-The Expanded Role of ChitosanDocument53 pagesHemmingsen-2021-The Expanded Role of ChitosanISRAELNo ratings yet

Synchronous Colorectal Cancers: A Review of Clinical Features, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prognosis

Synchronous Colorectal Cancers: A Review of Clinical Features, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prognosis

Uploaded by

Antonio GligorievskiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Synchronous Colorectal Cancers: A Review of Clinical Features, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prognosis

Synchronous Colorectal Cancers: A Review of Clinical Features, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prognosis

Uploaded by

Antonio GligorievskiCopyright:

Available Formats

Review Article

Dig Surg 2011;28:379–385 Received: July 8, 2011

Accepted after revision: September 25, 2011

DOI: 10.1159/000334073

Published online: December 8, 2011

Synchronous Colorectal Cancers:

A Review of Clinical Features,

Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prognosis

Jun Yang Jia-Yuan Peng Wei Chen

Department of Surgery, The Sixth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China

Key Words adenomas, since missed lesions can result in additional sur-

Synchronous colorectal cancer ⴢ Colorectal cancer ⴢ gery and poor prognosis, particular attention should be giv-

Adenomas, concurrent en to the high-risk group of older male patients.

Copyright © 2011 S. Karger AG, Basel

Abstract

Background/Aims: With the development of early diag- Introduction and Methods

nostic technologies, more synchronous colorectal cancers

(SCRCs) can be clinically detected. Although SCRCs are rec- Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common

ognized as a significant clinical entity, their clinical features, gastrointestinal cancers in the world today. Historically,

diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis have yet to be defini- CRC has been relatively rare in Asians, but the recent so-

tively established. In order to obtain a comprehensive un- cioeconomic development and adaptation to a western

derstanding of this disease and to establish an efficient pro- lifestyle in the Asia-Pacific region have been accompa-

file by which to recognize individuals at high risk of develop- nied by a significant increase in the incidence of CRC. In

ing SCRCs, we carried out a review of the relevant literature. addition, synchronous colorectal cancers (SCRCs) [1]

Methods: The PubMed database was searched for publica- have also risen globally, challenging the current treat-

tions of ‘synchronous colorectal carcinoma/cancer/adeno- ment strategies and adversely affecting the overall prog-

carcinoma’ and ‘multiple colorectal carcinomas’. All publica- nosis of CRC.

tions up to January 2011 were considered, and then only ar- The Warren and Gates criteria were established to

ticles in English were retrieved for inclusion in this review. clinically diagnose SCRCs [2] on the basis of pathological

Results: The incidence of SCRCs was found to be higher in findings in CRC biopsies. These criteria are in wide-

older and male patients. The prognosis in patients with spread use and include the following key elements: (1)

SCRCs was equivalent to that in patients with solitary CRC. each tumor must present a definite picture of malignan-

The failure to diagnose synchronous lesions before and dur- cy; (2) each tumor must be distinct; (3) the probability of

ing the operation was associated with repeated surgery. one being a metastasis of the other must be excluded, and

Conclusion: SCRCs possess distinctive features compared (4) the synchronous lesions must be diagnosed simulta-

to solitary CRC. While all colorectal patients should be care- neously or within 6 months of the initial diagnosis [3]. In

fully assessed to rule out the presence of concurrent colon SCRC, the most advanced cancer (as determined by tu-

© 2011 S. Karger AG, Basel Wei Chen

0253–4886/11/0286–0379$38.00/0 Department of Surgery, The Sixth People’s Hospital

Fax +41 61 306 12 34 Shanghai Jiao Tong University, 600 Yishan Road

E-Mail karger@karger.ch Accessible online at: Shanghai 200233 (China)

www.karger.com www.karger.com/dsu Tel. +86 216 436 1349, E-Mail wchen621225 @ yahoo.cn

Table 1. List of major studies on SCRCs

First author, Ref. No. Year of Type Cases Cases with

publication with SCRC, n CRC, n

Oya [4] 2003 nonrandomized, retrospective 42 834

Papadopoulos [7] 2004 nonrandomized, retrospective 26 1,160

Wang [9] 2004 nonrandomized, retrospective 15 1,311

Latournerie [10] 2008 nonrandomized, retrospective 596 14,966

Kaibara [11] 1984 nonrandomized, retrospective 763 23,866

Chen [12] 2000 nonrandomized, retrospective 52 1,728

Passman [15] 1996 nonrandomized, retrospective 160 4,718

Fukatsu [17] 2007 nonrandomized, retrospective 249 2,812

Nosho [29] 2009 prospective, cohort 47 2,021

Dykes [31] 2003 retrospective 77 2,807

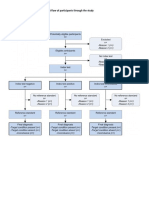

rectal carcinomas’ published up to January 2011. A total

PubMed databases up to January 2011: 71 articles

of 71 articles were identified. This list was restricted to

English-language articles only, resulting in 11 articles be-

Excluded because they were not in English (n = 11)

ing excluded. After retrieval and review of the remaining

articles, 15 more were excluded because upon closer in-

Potentially appropriate articles for more detailed assessment (n = 60)

spection the content was not relevant to this review. The

selection strategy is shown in figure 1. Finally, 45 articles

15 articles excluded after more detailed evaluation

were included in this review, 10 of which are summarized

in table 1.

45 articles were included in this review

SCRC Epidemiology

Fig. 1. Flow chart of article selection.

Prevalence

The prevalence of SCRCs has been reported as ranging

from 2.3 to 12.4% [5, 6]. The estimates of prevalence are

relatively broad due to the fact that there is no consistent

mor TNM staging) is usually designated as the index can- definition of synchronous events which could guide stud-

cer; the less advanced cancers (with lower TNM stage) are ies in the literature. Some studies defined ‘synchronous’

then considered as concurrent lesions of the index cancer. as a second carcinoma diagnosed less than 6 months after

In SCRC cases presenting with two or more lesions at an the diagnosis of the index tumor [3, 7–10], while others

identical pathological stage, the largest lesion is designat- defined it as a carcinoma arising 1 year or more after the

ed as the index cancer [4]. initial diagnosis [4, 11–13]. In addition, the SCRC popula-

Despite the growing incidence of SCRC, very little is tions have varied significantly in size and clinical and

known about its risk factors and prognosis. A compre- demographic characteristics between studies, and the

hensive overview of the SCRC profile, including patient study periods have also been very different.

features, lesion characteristics, treatments, and out- In earlier studies, the concepts of ‘synchronous’ and

comes, will not only help clinicians to more readily iden- ‘metachronous’ had not yet been fully distinguished, and

tify high-risk patients and design more effective treat- as a result the two were often mixed together in the anal-

ment strategies but will help guide researchers’ efforts to ysis, causing an overestimation of the synchronous inci-

elucidate the underlying molecular mechanisms of SCRC dence. Over time, advances in imaging technologies and

pathogenesis. To this end, we reviewed all journal articles diagnostic procedures have led to increased and earlier

in PubMed under the key words ‘synchronous colorectal detection of lesions; for example, colonoscopy is more ef-

carcinoma/cancer/adenocarcinoma’ and ‘multiple colo- fective than barium enema in detecting SCRCs [10], and

380 Dig Surg 2011;28:379–385 Yang/Peng/Chen

Table 2. Gender distribution of patients with SCRCs and CRC in the major studies

First author, Ref. No. SCRCs CRC p

male female male female

Oya [4] 33 (78.6%) 9 (21.4%) 492 (60%) 342 (40%) 0.018

Papadopoulos [7] 15 (57.7%) 11 (42.3%) 645 (55.6%) 515 (44.4%) 0.09

Takeuchi [8] 8 (89.9%) 1 (11.1%)

Wang [9] 11 (73%) 4 (27%)

Latournerie [10] 387 (64.9%) 209 (35.1%) 8,216 (54.9%) 6,750 (45.1%) <0.001

Kaibara [11] 524 (68.7%) 239 (31.3%)

Chen [12] 34 (65%) 18 (35%) 923 (53%) 805 (47%) 0.088

Fukatsu [17] 175 (70.3%) 74 (29.7%) 1,624 (58%) 1,624 (58%) <0.01

Tziris [18] 7 (58.3%) 5 (41.7%) 157 (58.6%) 111 (41.4%)

its widespread application has coincided with increased determined that the male/female ratio of SCRCs was 1.85,

diagnosis. Nonetheless, the most current estimates of in- whereas in CRC it was 1.22 (p ! 0.001). Oya et al. [4] also

cidences are still considered to be inaccurate since not all reported a similar male predominance in SCRC cases, but

tumors are discovered clinically and the amount of re- observed an even higher ratio in their study population

lated population studies is still relatively low. (p = 0.018). Fukatsu et al. [17] further determined that the

lesions of male patients principally occurred in the left

Age colon or bilaterally; however, lesions that occurred exclu-

Previous studies have not reached consensus on the sively in the right colon were not associated with a male

relationship between age and the incidence of SCRCs. or female bias. Their analysis indicated that the male gen-

Several authors indicated that patients with SCRCs were der was a significant risk factor only for those with both

older than those with CRC [6, 14, 15], while others found tumors located in the left colon [17]. Until now, there has

that SCRC was present more often in the younger patients been no obvious explanation for this phenomenon.

[3, 16]. Three more recent studies, however, concluded

that there was no significant difference in age of individ-

uals with CRC and those with SCRC [4, 12, 17]. It is pos- Pathological Characteristics

sible that in the earlier studies the reliance on basic sta-

tistical approaches limited their ability to determine the Number and Location of the Lesions

association of age with SCRC. When Fukatsu et al. [17] Most SCRCs consist of 2 lesions, but some patients

stratified the 249 SCRC patients in their study by tumor have 3 or even 4. In an exceptional case, Kaibara et al. [11]

location, they found that patients with synchronous le- reported a patient with 7 simultaneous colon cancers.

sions in the right or in both sides of the colon were sig- When making comparisons between locations of SCRCs

nificantly older than those with lesions in the left colon and single carcinomas, most studies have found that

(right/both vs. left: 71.9 8 9.1/69.4 8 9.5 vs. 64.4 8 11.0 SCRCs are more frequently located in the right colon [12,

years, p ! 0.0167). Likewise, when Latournerie et al. [10] 15, 19]. However, Oya et al. [4] and Finan et al. [20] re-

investigated the complex associations of risk factors with ported a predominance in the left colon. Location of the

SCRC by using advanced statistical approaches, includ- index and concurrent lesion is important since it can af-

ing multivariate logistic regression, they found that pa- fect the treatment strategy; for example, if the lesions are

tients aged 75 years and over were more likely than located far away from each other, then a more extensive

younger patients to have SCRCs (odds ratio: 1.31). resection may be required. Passman et al. [15] found that

the majority of patients (63.8%; 102/160) had lesions lo-

Gender cated in different segments of the colon. The study by

As shown in table 2, several studies have found that Kaibara et al. [11], however, found opposite results, with

men are at higher risk of SCRCs [4, 7–12, 17, 18]. As the 62.5% (405/648) of patients having lesions in the same

largest scale study in recent years, Latournerie et al. [10] segment and only 2.3% (15/648) of the lesions were lo-

Synchronous Colorectal Cancers: Dig Surg 2011;28:379–385 381

A Review

cated in completely separate segments. Latournerie et al. Similarly, if both tumors were in the left colon, the adeno-

[10] also found that more of the patients had lesions in the mas tended to occur in the left colon. Evers et al. [3] also

same segment of the colon, but the percentage was not as found that in SCRCs, 52% had adenoma remnants; this

distinctive from those with different segment location result was similar to the findings of Latournerie et al. [10]

(54 vs. 46%, respectively). in a pathological examination, which revealed adenoma-

tous remnants in 24.3% of SCRCs but only 12.7% of single

Characteristics of Synchronous Lesions cancers. These data collectively support the hypothesis

Comparison between SCRCs and CRC of an adenoma-carcinoma sequence in SCRC. Thus, pa-

Oya et al. [4] studied 876 surgically resected primary tients with a history of adenoma or early carcinoma pol-

colorectal carcinomas and their study was the only one to yps should be carefully screened for SCRC upon discov-

specifically compare SCRCs with CRC. They found that ery of new colon lesions, as suggested by Cunliffe et al.

synchronous carcinomas were significantly smaller in [6].

size (p ! 0.001), more frequently located in the left colon

(p = 0.001), penetrated the wall less (p ! 0.001), and were Potential Risk Factors

more common in advanced lesions (p = 0.003) than CRC. A few studies have investigated potential risk factors

for the development of SCRCs. Kimura et al. [16], in par-

Comparison between Index Lesions and Concurrent ticular, explored the relation between the family history

Lesions in SCRCs of cancer and the incidence of synchronous lesions, but

The index lesion is clinically defined as the pathologi- found no significant correlation between the two. Borda

cally most advanced lesion. Four of the studies specifi- et al. [22] explored the potential contribution of body

cally reported on the characteristics that distinguished mass index (BMI) and determined that BMI !21 might

the index lesion from the concurrent lesions [4, 12, 20]. act a protective factor against synchronous lesions. How-

Not surprisingly, the index lesions were usually larger in ever, this correlation was lost in more detailed statistical

size, more frequently moderately differentiated, more analyses when the sexes were stratified, and it was as-

deeply penetrated, and more often ulcerated in morphol- sumed that the overall lower BMI in the females of their

ogy than the concurrent lesions. Moreover, one study re- study population may have influenced the original find-

ported that lymphatic invasion was also more frequent in ing. Tobacco and alcohol consumption have been evalu-

index lesions than in concurrent lesions [4]. ated in several CRC studies, and are considered a risk

factor for CRC. When Borda et al. [22] investigated both

Comparison between Index Lesions of SCRCs habits in relation to SCRC, they found that these habits

and CRC were statistically associated with the male sex but not

Oya et al. [4] made comparisons between the index le- with synchronous lesions. Maekawa et al. [23], however,

sions of SCRCs and CRC to determine if there were dif- reported that if the accumulated amount of alcohol (alco-

ferences in key features of the tumor pathology that hol weekly average multiplied by years of drinking) ex-

would serve as diagnostic or prognostic markers. While ceeded 9,800, the risk of SCRCs was approximately 6.8-

the authors found no differences in size, differentiation, fold higher than in nondrinkers; this association was not

location, pathological stage, morphology, or lymphatic affected by the type of alcohol beverages consumed. The

invasion, they did discover that distant metastasis and biological mechanisms of alcohol-related carcinogenesis

venous invasion were more common in index lesions of are largely undefined, but alcohol intake may render the

synchronous cases. entire colorectal mucosa unstable, making it generally

more susceptible to malignant changes [23].

The Incidence of Concurrent Adenomas

Most studies have reported that the incidence of con- Genetic Analysis

current adenomas was significantly higher in patients The molecular explanation for SCRCs is uncertain.

with SCRCs than in those with solitary cancer [3, 12, 13, The genetic events underlying CRC, however, have been

21]. Latournerie et al. [10] reported that 34.1% of patients thoroughly studied and CRC can be divided into three

with SCRCs had adenomas compared with 19.1% of the distinct phenotypes. Chromosomal instability denotes

single cancers. They also showed that patients with tumors with frequent karyotypic abnormalities and

SCRCs, in which both tumors were in the right colon, chromosomal gains and losses. Microsatellite instability

were likely to have concurrent adenomas in the right side. (MSI) denotes tumors with altered lengths of short nucle-

382 Dig Surg 2011;28:379–385 Yang/Peng/Chen

otide repeat sequences. Finally, the CpG island methyla- 50% failure rate in detecting lesions of SCRCs [33], espe-

tion phenotype (CIMP) denotes tumors in which tran- cially when the tumor is at an earlier histological stage

scriptional inactivation has occurred by the epigenetic [34]. For this reason, full clinical and radiological inves-

mechanism of cytosine methylation in promoters of tu- tigation is essential prior to the operation. In the early

mor suppressor genes. Each of these genetic features has 1970s, examination of patients with large bowel symp-

been demonstrated to play a significant role in patholog- toms was mainly based on barium enema and rigid sig-

ical and biological characteristics of CRC [24]. moidoscopy. Over the past few years, though, there have

One of the most important tumor suppressor genes is been important changes in diagnostic procedures for

p53. This gene is considered to be the most prevalent ge- CRC. Extensive use of preoperative colonoscopy is rec-

netic alteration in human neoplasms. Eguchi et al. [25] ommended in order to thoroughly evaluate the colorectal

found that in SCRCs, the p53 mutations in left-sided and cancer status and promote detection of SCRCs. Kaibara

rectal carcinomas were different from those in right-sid- et al. [11] reported a 60.1% frequency of preoperative di-

ed carcinomas (p = 0.04), supporting the idea that SCRCs agnosis of SCRCs by double-contrast barium examina-

may be of multicentric origin [26]. In addition, Yalcinka- tion or colonoscopy, whereas Takeuchi et al. [8] reported

ya et al. [27] showed that p53 expression in SCRCs was that using both methods resulted in an overall preopera-

strongly associated with aggressiveness and poor prog- tive accuracy of 77.8%. However, neither of these diagno-

nosis; specifically, adenocarcinomas with poor differen- sis rates was optimal and an unacceptable amount of

tiation and deeper invasion had higher expression of p53. SCRCs goes undiagnosed.

Gonzalo et al. [28] found that the gene promoter meth- The barium enema may fail to make a diagnosis be-

ylation status was associated with SCRCs, particularly in cause visualization of the tumor may be obscured by

MGMT1, MGMT2 and RASSF1A genes. Nosho et al. [29] bleeding or inadequate bowel preparation and retained

also showed that SCRCs more frequently contained mu- feces. The presence of an annular carcinoma may also

tations in the cell cycle signaling gene BRAF (p = 0.0041), interfere with preparative cleansing and passage of bari-

were largely of the CIMP (66/8 methylated promoters um through the lesion, effectively masking proximal le-

using the 8-marker CIMP panel, p = 0.013), and had high sions. With colonoscopy, the quality of the view is better

methylation levels on the long interspersed nuclear ele- in most cases, but good preparation of the large bowel is

ment-1 retrotransposon sequences (p = 0.0072) and on still essential. However, scirrhous cancers may prevent

CpG islands (p ! 0.0001). the passage of the endoscope through the lumen and hin-

Pedroni et al. [30] reported 32% MSI in SCRCs, similar der detection of additional lesions.

to the 32% incidence of MSI reported in the research by There is still some controversy about which examina-

Dykes et al. [31]. Nosho et al. [29] also found that the MSI- tion is better to fully detect SCRCs. Nowadays, virtual

high phenotype, defined as the presence of instability in colonoscopy has become a viable alternative method for

630% of the markers, was more common in SCRCs (p = the evaluation of the whole colon. CT colonography is

0.037). These data suggest that the MSI phenotype is above all of value in those patients with stenosis or colon

more common in SCRC lesions than in those that arise as elongation that leads to incomplete colonoscopy. It is not

solitary lesions. However, Brueckl et al. [32] reported that only useful in the evaluation of the proximal bowel, but

only 10% of patients with SCRCs were characterized as can also provide surgeons with accurate information

MSI. The MSI phenotype, then, may actually describe a about staging and tumor localization [35, 36]. Other tech-

yet unrecognized subtype of SCRC pathology or patients. nical advances, such as magnetic resonance colonogra-

phy [37] and the combination of CT colonography with

PET [38], have been reported as useful tools for the pre-

Diagnosis operative evaluation of SCRCs. Intraoperative endoscopy

is another available method to perform a complete ex-

Preoperative or intraoperative diagnosis of SCRCs is amination of the colon and rectum in cases where a pre-

very important. Failure to diagnose leads to errors in operative colonoscopy is not feasible, such as in emer-

treatment and poor prognosis. It is important to palpate gency situations. While this approach provides sufficient

the entire colon carefully before the end of the operation results, it is time-consuming and makes closure of the

for CRC so that a misdiagnosis of SCRCs can be avoided. abdomen difficult since the bowel becomes distended

Unfortunately, however, such intraoperative palpation is with air [39].

relatively insensitive and associated with a greater than

Synchronous Colorectal Cancers: Dig Surg 2011;28:379–385 383

A Review

Treatment Option and Prognosis The expected 5-year survival rates of patients affected

by SCRCs are still controversial. While one study found

Surgical resection is the primary treatment option for a higher survival in patients with SCRCs [45], others have

SCRCs. Passman et al. [15] recommended that patients demonstrated that patients with single colon primary tu-

with lesions in adjacent segments receive a more exten- mors are more likely to survive [4, 41]. In the first pro-

sive resection, including removal of proximal intestinal spective study carried out to eliminate sources of consid-

regions and local lymph nodes in some cases. There is still erable bias that were inevitably present in retrospective

some controversy on how to best treat synchronous le- case-control studies, Nosho et al. [29] showed that SCRC

sions in separate segments. Some authors have suggested cases were significantly associated with poor prognosis.

that total or subtotal colectomy should be performed [9, Poor prognosis of SCRCs is thought to be due mainly to

14, 40, 41], because if synchronous lesions are overlooked the relatively frequent distant metastasis that occur in

at the time of surgery, the patient may soon have to un- synchronous cases [4]. However, even more studies have

dergo repeated surgery and the lesions are likely to have shown that there is no difference in survival between

advanced in their pathological stage and to be associated SCRCs and CRC when the pathological stages of tumors

with a poorer prognosis [4]. Some authors have suggested were identical and the resections were curative [7, 10, 12,

the utility of extensive procedures such as proctocolec- 15, 16, 19, 21].

tomy with J-pouch ileoanal anastomosis, total abdominal

colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis, and proctosig-

moidectomy with coloanal anastomosis [33]. Conclusion

A more conservative policy consisting of multiple seg-

mental resections which aim to retain the normal colon With the development of early diagnostic technolo-

has been suggested by some [19]. The reasons for such an gies, more SCRCs have been diagnosed. Compared with

approach are that a subtotal colectomy may increase stool the solitary CRC, SCRCs possess distinctive features.

frequency, and synchronous colon anastomoses do not These should be fully investigated in preoperative clinical

appear to be associated with an increased risk of compli- workups to avoid the possibility of accessory lesions being

cations [42]. Based on the available evidence, it appears overlooked and not resected. Older male patients with

that when the patient’s general condition is suitable for concurrent adenomas in the colon are at a particularly

undergoing an operation or when the patient is at an in- high risk of SCRCs and close attention should be paid

creased risk of anastomotic complications, such as in cas- to them. The extent of surgical resection relies on the

es of malnourishment, immunosuppression or sepsis, location and the number of lesions. The resected region

then subtotal colectomy seems a justifiable choice [34, 40, should include enough intestinal length and regional

42]. In some case reports, the authors treated T1 rectal lymph nodes to capture any local spread, thereby guard-

cancer with SCRCs by transanal endoscopic microsur- ing against recurrence or subsequent malignant change.

gery before performing a radical operation for the second Of course, the mechanisms regarding the formation of

lesion [43]. In another report, a single-incision laparo- multicentricity need to be fully elucidated in order to gain

scopic total abdominal colectomy with an ileorectal anas- insight into SCRC genesis and development, which will

tomosis and intraoperative CO2 colonoscopy was suc- ultimately benefit molecular therapies and improve pa-

cessfully performed for a patient with SCRCs of the ce- tient survival.

cum and the sigmoid colon [44].

References

1 Fenger C: I. Surgery of the ureter. Ann Surg 4 Oya M, Takahashi S, Okuyama T, Yamagu- 6 Cunliffe WJ, Hasleton PS, Tweedle DE,

1894;20:257–296. chi M, Ueda Y: Synchronous colorectal car- Schofield PF: Incidence of synchronous and

2 Warren S, Gates O: Carcinoma of cerumi- cinoma: clinico-pathological features and metachronous colorectal carcinoma. Br J

nous gland. Am J Pathol 1941; 17:821–826.3. prognosis. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2003;33:38–43. Surg 1984;71:941–943.

3 Evers BM, Mullins RJ, Matthews TH, 5 Welch JP: Multiple colorectal tumors. An ap- 7 Papadopoulos V, Michalopoulos A, Basda-

Broghamer WL, Polk HC Jr: Multiple adeno- praisal of natural history and therapeutic op- nis G, Papapolychroniadis K, Paramythiotis

carcinomas of the colon and rectum. An tions. Am J Surg 1981;142:274–280. D, Fotiadis P, Berovalis P, Harlaftis N: Syn-

analysis of incidences and current trends. chronous and metachronous colorectal

Dis Colon Rectum 1988;31:518–522. carcinoma. Tech Coloproctol 2004; 8(suppl

1):s97–s100.

384 Dig Surg 2011;28:379–385 Yang/Peng/Chen

8 Takeuchi H, Toda T, Nagasaki S, Kawano T, 21 Nikoloudis N, Saliangas K, Economou A, 33 Arenas RB, Fichera A, Mhoon D, Michelassi

Minamisono Y, Maehara Y, Sugimachi K: Andreadis E, Siminou S, Manna I, Georgakis F: Incidence and therapeutic implications of

Synchronous multiple colorectal adenocar- K, Chrissidis T: Synchronous colorectal can- synchronous colonic pathology in colorectal

cinomas. J Surg Oncol 1997;64:304–307. cer. Tech Coloproctol 2004; 8(suppl 1):s177– adenocarcinoma. Surgery 1997; 122: 706–

9 Wang HZ, Huang XF, Wang Y, Ji JF, Gu J: s179. 709, discussion 709–710.

Clinical features, diagnosis, treatment and 22 Borda A, Martinez-Penuela JM, Munoz-Na- 34 Hancock RJ: Synchronous carcinoma of the

prognosis of multiple primary colorectal vas M, Prieto C, Betes M, Borda F: Synchro- colon and rectum. Am Surg 1975; 41: 560–

carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2004; 10: nous neoplastic lesions in colorectal cancer. 563.

2136–2139. An analysis of possible risk factors favouring 35 Kim MS, Park YJ: Detection and treatment

10 Latournerie M, Jooste V, Cottet V, Lepage C, presentation. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2008;100: of synchronous lesions in colorectal cancer:

Faivre J, Bouvier AM: Epidemiology and 139–145. the clinical implication of perioperative

prognosis of synchronous colorectal can- 23 Maekawa SJ, Aoyama N, Shirasaka D, Kuro- colonoscopy. World J Gastroenterol 2007;13:

cers. Br J Surg 2008;95:1528–1533. da K, Tamura T, Kuroda Y, Kasuga M: Exces- 4108–4111.

11 Kaibara N, Koga S, Jinnai D: Synchronous sive alcohol intake enhances the develop- 36 McArthur DR, Mehrzad H, Patel R, Dadds J,

and metachronous malignancies of the colon ment of synchronous cancerous lesion in Pallan A, Karandikar SS, Roy-Choudhury S:

and rectum in Japan with special reference to colorectal cancer patients. Int J Colorectal CT colonography for synchronous colorectal

a coexisting early cancer. Cancer 1984; 54: Dis 2004;19:171–175. lesions in patients with colorectal cancer:

1870–1874. 24 Ogino S, Goel A: Molecular classification initial experience. Eur Radiol 2010; 20: 621–

12 Chen HS, Sheen-Chen SM: Synchronous and and correlates in colorectal cancer. J Mol Di- 629.

‘early’ metachronous colorectal adenocarci- agn 2008;10:13–27. 37 Achiam MP, Holst Andersen LP, Klein M,

noma: analysis of prognosis and current 25 Eguchi K, Yao T, Konomoto T, Hayashi K, Chabanova E, Thomsen HS, Rosenberg J:

trends. Dis Colon Rectum 2000; 43: 1093– Fujishima M, Tsuneyoshi M: Discordance of Preoperative evaluation of synchronous

1099. p53 mutations of synchronous colorectal colorectal cancer using MR colonography.

13 Ueno M, Muto T, Oya M, Ota H, Azekura K, carcinomas. Mod Pathol 2000; 13:131–139. Acad Radiol 2009;16:790–797.

Yamaguchi T: Multiple primary cancer: an 26 Koness RJ, King TC, Schechter S, McLean SF, 38 Kinner S, Antoch G, Bockisch A, Veit-Hai-

experience at the Cancer Institute Hospital Lodowsky C, Wanebo HJ: Synchronous co- bach P: Whole-body PET/CT-colonography:

with special reference to colorectal cancer. lon carcinomas: molecular-genetic evidence a possible new concept for colorectal cancer

Int J Clin Oncol 2003;8:162–167. for multicentricity. Ann Surg Oncol 1996; 3: staging. Abdom Imaging 2007;32:606–612.

14 Slater G, Aufses AH Jr, Szporn A: Synchro- 136–143. 39 Kaibara N, Kimura O, Nishidoi H, Miyano Y,

nous carcinoma of the colon and rectum. 27 Yalcinkaya U, Ozturk E, Ozgur T, Yerci O, Koga S: Intraoperative colonoscopy for the

Surg Gynecol Obstet 1990;171:283–287. Yilmazlar T: P53 expression in synchronous diagnosis of multiple cancers of the large in-

15 Passman MA, Pommier RF, Vetto JT: Syn- colorectal cancer. Saudi Med J 2008;29:826– testine. Jpn J Surg 1982;12:117–121.

chronous colon primaries have the same 831. 40 Easson AM, Cotterchio M, Crosby JA,

prognosis as solitary colon cancers. Dis Co- 28 Gonzalo V, Lozano JJ, Munoz J, Balaguer F, Sutherland H, Dale D, Aronson M, Holowaty

lon Rectum 1996;39:329–334. Pellise M, Rodriguez de Miguel C, Andreu E, Gallinger S: A population-based study of

16 Kimura T, Iwagaki H, Fuchimoto S, Hizuta M, Jover R, Llor X, Giraldez MD, et al: Aber- the extent of surgical resection of potentially

A, Orita K: Synchronous colorectal carcino- rant gene promoter methylation associated curable colon cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2002;

mas. Hepatogastroenterology 1994; 41: 409– with sporadic multiple colorectal cancer. 9:380–387.

412. PLoS One 2010;5:e8777. 41 Enker WE, Dragacevic S: Multiple carcino-

17 Fukatsu H, Kato J, Nasu JI, Kawamoto H, 29 Nosho K, Kure S, Irahara N, Shima K, Baba mas of the large bowel: a natural experiment

Okada H, Yamamoto H, Sakaguchi K, Shira- Y, Spiegelman D, Meyerhardt JA, Giovan- in etiology and pathogenesis. Ann Surg 1978;

tori Y: Clinical characteristics of synchro- nucci EL, Fuchs CS, Ogino S: A prospective 187:8–11.

nous colorectal cancer are different accord- cohort study shows unique epigenetic, ge- 42 Holubar SD, Wolff BG, Poola VP, Soop M:

ing to tumour location. Dig Liver Dis 2007; netic, and prognostic features of synchro- Multiple synchronous colonic anastomoses:

39:40–46. nous colorectal cancers. Gastroenterology are they safe? Colorectal Dis 2010; 12: 135–

18 Tziris N, Dokmetzioglou J, Giannoulis K, 2009;137:1609–1620.e1–3. 140.

Kesisoglou I, Sapalidis K, Kotidis E, Gam- 30 Pedroni M, Tamassia MG, Percesepe A, Ron- 43 Ikeda Y, Koyanagi N, Mori M, Akahoshi K,

bros O: Synchronous and metachronous ad- cucci L, Benatti P, Lanza G Jr, Gafa R, Di Gre- Ueyama T, Sugimachi K: Transanal endo-

enocarcinomas of the large intestine. Hip- gorio C, Fante R, Losi L, et al: Microsatellite scopic microsurgery for T1 rectal cancer in

pokratia 2008;12:150–152. instability in multiple colorectal tumors. Int patients with synchronous colorectal cancer.

19 Adloff M, Arnaud JP, Bergamaschi R, J Cancer 1999;81:1–5. Surg Endosc 1999; 13:710–712.

Schloegel M: Synchronous carcinoma of the 31 Dykes SL, Qui H, Rothenberger DA, Garcia- 44 Bardakcioglu O, Ahmed S: Single incision

colon and rectum: prognostic and therapeu- Aguilar J: Evidence of a preferred molecu- laparoscopic total abdominal colectomy

tic implications. Am J Surg 1989; 157: 299– lar pathway in patients with synchronous with ileorectal anastomosis for synchronous

302. colorectal cancer. Cancer 2003;98:48–54. colon cancer. Tech Coloproctol 2010;14:257–

20 Finan PJ, Ritchie JK, Hawley PR: Synchro- 32 Brueckl WM, Limmert T, Brabletz T, Guen- 261.

nous and ‘early’ metachronous carcinomas ther K, Jung A, Hermann K, Wiest GH, 45 Copeland EM, Jones RS, Miller LD: Multiple

of the colon and rectum. Br J Surg 1987; 74: Kirchner T, Hohenberger W, Hahn EG, et al: colon neoplasms. Prognostic and therapeu-

945–947. Mismatch repair deficiency in sporadic syn- tic implications. Arch Surg 1969;98:141–143.

chronous colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res

2000;20:4727–4732.

Synchronous Colorectal Cancers: Dig Surg 2011;28:379–385 385

A Review

You might also like

- LMCC CDM Sample QuestionsDocument22 pagesLMCC CDM Sample Questionsaaycee100% (2)

- Blood TransfusionDocument59 pagesBlood Transfusionpranalika .................76% (17)

- Health Informatics in The PhilippinesDocument2 pagesHealth Informatics in The PhilippinesLianefhel S. Del RosarioNo ratings yet

- Atlas of Endoscopy With NBIDocument351 pagesAtlas of Endoscopy With NBICosmin Gabriel CristeaNo ratings yet

- Molluscum MedscapeDocument35 pagesMolluscum MedscapeAninditaNo ratings yet

- Metanalisis 2010Document11 pagesMetanalisis 2010Elmer chavezNo ratings yet

- s10151 021 02436 5Document10 pagess10151 021 02436 5Ottofianus Alvedo Hewick KalangiNo ratings yet

- Prentice Et Al. - 2018 - Malignant Ureteric Obstruction Decompression HowDocument11 pagesPrentice Et Al. - 2018 - Malignant Ureteric Obstruction Decompression HowAli SlimaniNo ratings yet

- Loop Vs DividedDocument8 pagesLoop Vs DividedNatalindah Jokiem Woecandra T. D.No ratings yet

- WarshawDocument11 pagesWarshawJuan RamirezNo ratings yet

- Fonc 09 00597Document13 pagesFonc 09 00597Giann PersonaNo ratings yet

- Journal Pone 0255835Document11 pagesJournal Pone 0255835Great CoassNo ratings yet

- Percutaneous Needle Aspiration Versus Catheter Drainage in Treating Hepatic AbscessDocument8 pagesPercutaneous Needle Aspiration Versus Catheter Drainage in Treating Hepatic AbscessRatna TriasnawatiNo ratings yet

- Soft Tissue Sarcoma Asia-PasificDocument13 pagesSoft Tissue Sarcoma Asia-PasificHayyu F RachmadhanNo ratings yet

- MedicinaDocument23 pagesMedicinametadesyana1No ratings yet

- Research Article: Characteristics of Patients With Colonic Polyps Requiring Segmental ResectionDocument7 pagesResearch Article: Characteristics of Patients With Colonic Polyps Requiring Segmental ResectionAkiko Syawalidhany TahirNo ratings yet

- Tanaka 2012Document15 pagesTanaka 2012Veronica Rahayu FsNo ratings yet

- Articulo - Mapeo Ecográfico Preoperatorio Antes de La Fístula ArteriovenosaDocument12 pagesArticulo - Mapeo Ecográfico Preoperatorio Antes de La Fístula ArteriovenosaDidier Javier DuránNo ratings yet

- Learning The Nodal Stations in The AbdomenDocument9 pagesLearning The Nodal Stations in The Abdomentufis02No ratings yet

- Pancreatology: Review ArticleDocument15 pagesPancreatology: Review ArticleRociio Del Carmen GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Shan 2018Document4 pagesShan 2018pancholin_9No ratings yet

- Consenso Italiano PA SeveraDocument70 pagesConsenso Italiano PA SeveraFabrizzio BardalesNo ratings yet

- CT Based Delineation of Organs at Risk in The Head and Neck RegionDocument7 pagesCT Based Delineation of Organs at Risk in The Head and Neck RegionshokoNo ratings yet

- EJSO OTOASORTrial2017Document9 pagesEJSO OTOASORTrial2017akayaNo ratings yet

- Management and Recurrence of Keratocystic Odontogenic Tumor: A Systematic ReviewDocument6 pagesManagement and Recurrence of Keratocystic Odontogenic Tumor: A Systematic ReviewRonal RonNo ratings yet

- 26Li-2019-Leveraging Latent Dirichlet AllocationDocument15 pages26Li-2019-Leveraging Latent Dirichlet AllocationRODRIGO FERNANDO PAUCAR RECALDENo ratings yet

- Long-Term Effects of Everolimus-Facilitated Tacrolimus Reduction in Living-Donor Liver Transplant Recipients With Hepatocellular CarcinomaDocument13 pagesLong-Term Effects of Everolimus-Facilitated Tacrolimus Reduction in Living-Donor Liver Transplant Recipients With Hepatocellular CarcinomaanonNo ratings yet

- ESWL For CholelithiasisDocument25 pagesESWL For CholelithiasisKhildaZakiyyahSa'adahNo ratings yet

- Meta 5 - Song S - 2022Document12 pagesMeta 5 - Song S - 2022matheus.verasNo ratings yet

- Nakata 2021Document15 pagesNakata 2021FlaviusNo ratings yet

- Reviews in Basic and Clinical Gastroenterology and HepatologyDocument13 pagesReviews in Basic and Clinical Gastroenterology and HepatologyJesús MoraNo ratings yet

- Journal Pone 0191786Document9 pagesJournal Pone 0191786tonyhawkNo ratings yet

- 10.1007@s00464 020 07698 yDocument11 pages10.1007@s00464 020 07698 yGabriel RangelNo ratings yet

- Laparoscopic Versus Open Radical Cystectomy in Bladder Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Comparative StudiesDocument14 pagesLaparoscopic Versus Open Radical Cystectomy in Bladder Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Comparative StudiesVinko GrubišićNo ratings yet

- Abdi Et Al 2023 Operative Treatment of Tarlov Cysts Outcomes and Predictors of Improvement After Surgery A Series of 97Document8 pagesAbdi Et Al 2023 Operative Treatment of Tarlov Cysts Outcomes and Predictors of Improvement After Surgery A Series of 97jabarin.hNo ratings yet

- Early Detection Oral CDocument13 pagesEarly Detection Oral CMuhammad Ikhsan ChaniagoNo ratings yet

- Baumann 2016 IJROBP Development Validation of Bladder Contouring AtlasDocument9 pagesBaumann 2016 IJROBP Development Validation of Bladder Contouring AtlaszanNo ratings yet

- J Hepato Biliary Pancreat - 2020 - Ando - Clinical Practice Guidelines For Biliary Atresia in Japan A SecondaryDocument7 pagesJ Hepato Biliary Pancreat - 2020 - Ando - Clinical Practice Guidelines For Biliary Atresia in Japan A SecondaryMONICA BRAVONo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0302283815001578 MainDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S0302283815001578 MainyuenkeithNo ratings yet

- Bladder CancerDocument11 pagesBladder CancerRaisa SevenryNo ratings yet

- Wrist Ganglion Treatment - 2015 (Tema 4)Document16 pagesWrist Ganglion Treatment - 2015 (Tema 4)Carlos NoronaNo ratings yet

- Li 2012Document7 pagesLi 2012selvioNo ratings yet

- Systematic Review The Effect of Right Hemicolectom PDFDocument12 pagesSystematic Review The Effect of Right Hemicolectom PDFMarco NunesNo ratings yet

- Journal of Controlled Release: Alexander Wei, Jonathan G. Mehtala, Anil K. PatriDocument11 pagesJournal of Controlled Release: Alexander Wei, Jonathan G. Mehtala, Anil K. Patriprakush_prakushNo ratings yet

- Review Pancreatic CancerDocument7 pagesReview Pancreatic CancerLauburu CrossNo ratings yet

- Conrad Et Al-2017-Journal of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic SciencesDocument14 pagesConrad Et Al-2017-Journal of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic SciencesAndra CiocanNo ratings yet

- 12 Penile Cancer LRDocument38 pages12 Penile Cancer LRhizfisherNo ratings yet

- Selecting The Best Elements From Previous Kidney Tumor Scoring System To Restructure Efficient Predictive Models For Surgery TypeDocument7 pagesSelecting The Best Elements From Previous Kidney Tumor Scoring System To Restructure Efficient Predictive Models For Surgery TypeMuhammad RifkiNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness and Durability of Ureteral TumorDocument4 pagesThe Effectiveness and Durability of Ureteral TumorAli SlimaniNo ratings yet

- Meta 2 - Sofi AA - 2018Document9 pagesMeta 2 - Sofi AA - 2018matheus.verasNo ratings yet

- Gu 2018Document10 pagesGu 2018Dela MedinaNo ratings yet

- Expert Consensus Contouring Guidelines For Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy in Esophageal and Gastroesophageal Junction CancerDocument10 pagesExpert Consensus Contouring Guidelines For Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy in Esophageal and Gastroesophageal Junction CancermarrajoanaNo ratings yet

- 10.1007@s13304 019 00648 XDocument8 pages10.1007@s13304 019 00648 XGabriel RangelNo ratings yet

- Clinical Spotlight Review - Intraoperative Cholangiography - A SAGES PublicationDocument19 pagesClinical Spotlight Review - Intraoperative Cholangiography - A SAGES PublicationMu TelaNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Biliary Anatomy According To Different Classification SystemsDocument8 pagesAn Analysis of Biliary Anatomy According To Different Classification SystemsDiego CadenaNo ratings yet

- Lymph Node Density As A Prognostic Variable in Node Positive Bladder Cancer A Meta-AnalysisDocument10 pagesLymph Node Density As A Prognostic Variable in Node Positive Bladder Cancer A Meta-AnalysisOswaldo MascareñasNo ratings yet

- WJGS 8 376Document7 pagesWJGS 8 376Inamullah FurqanNo ratings yet

- A Meta-Analysis of The Value oDocument18 pagesA Meta-Analysis of The Value osatria divaNo ratings yet

- Primary Duodenal Adenocarcinoma: Mario Solej, Silvia D'Amico, Gabriele Brondino, Marco Ferronato, and Mario NanoDocument8 pagesPrimary Duodenal Adenocarcinoma: Mario Solej, Silvia D'Amico, Gabriele Brondino, Marco Ferronato, and Mario NanoMoises Nuñez VargasNo ratings yet

- Cho Et Al., 2014Document8 pagesCho Et Al., 2014NyomantrianaNo ratings yet

- 2018 SNMMI EANM DMSA Adult GuidelinesDocument11 pages2018 SNMMI EANM DMSA Adult Guidelinesmaliborda11No ratings yet

- ASGE Guideline On The Management of Cholangitis 2021Document29 pagesASGE Guideline On The Management of Cholangitis 2021osamayasser82No ratings yet

- Laparoscopic Gastrectomy for Cancer: Standard Techniques and Clinical EvidencesFrom EverandLaparoscopic Gastrectomy for Cancer: Standard Techniques and Clinical EvidencesSeigo KitanoNo ratings yet

- JRCR - Author & Reviewer Guidelines: Manuscript TemplateDocument8 pagesJRCR - Author & Reviewer Guidelines: Manuscript TemplateAntonio GligorievskiNo ratings yet

- Kjco 14 2 83Document6 pagesKjco 14 2 83Antonio GligorievskiNo ratings yet

- STARD 2015 Flow Diagram PDFDocument1 pageSTARD 2015 Flow Diagram PDFAntonio GligorievskiNo ratings yet

- STARD 2015 Flow DiagramDocument1 pageSTARD 2015 Flow DiagramAntonio GligorievskiNo ratings yet

- Film-Screen Mammography QA: What You Need To Know: ObjectivesDocument13 pagesFilm-Screen Mammography QA: What You Need To Know: ObjectivesAntonio GligorievskiNo ratings yet

- Img 20190521 0001 PDFDocument1 pageImg 20190521 0001 PDFMaelyn FavilaNo ratings yet

- Adult CPR ProcedureDocument3 pagesAdult CPR ProcedureDaniica MacaranasNo ratings yet

- Pe and Health Module - Mapeh 4 2nd SemDocument17 pagesPe and Health Module - Mapeh 4 2nd SemCleofe Sobiaco0% (1)

- Bayi Baru LahirDocument43 pagesBayi Baru LahirBRI KUNo ratings yet

- Dalaodao, Mylen Humss A Reflection PaperDocument1 pageDalaodao, Mylen Humss A Reflection PaperMylen DalaodaoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To EpidemiologyDocument61 pagesIntroduction To Epidemiologycas'perNo ratings yet

- Drug Study ClonidineDocument2 pagesDrug Study ClonidineCezanne CruzNo ratings yet

- Walsh Org Chart MasterDocument3 pagesWalsh Org Chart MasterfatmawatiNo ratings yet

- Intro Neuro MriDocument49 pagesIntro Neuro MriJess RiveraNo ratings yet

- 12 - Ocular Pharmacology - 343 - 64Document37 pages12 - Ocular Pharmacology - 343 - 64ณัฐ มีบุญNo ratings yet

- Ten Paripally1 221113Document52 pagesTen Paripally1 221113Kshitij KumareNo ratings yet

- AFES FINAL Announcement As of 14 SepDocument16 pagesAFES FINAL Announcement As of 14 Sepvanhau24No ratings yet

- ParathyroidDocument24 pagesParathyroidLeonard AcsinteNo ratings yet

- DOLOCAN Dolocem CBD Eczema Cream White Paper - 20190917Document1 pageDOLOCAN Dolocem CBD Eczema Cream White Paper - 20190917Petra MitićNo ratings yet

- EBP PosterDocument1 pageEBP PosterDolani N. AjanakuNo ratings yet

- Gems of Homoepathic Materia Medica J D Patil.01602 2Document6 pagesGems of Homoepathic Materia Medica J D Patil.01602 2Sheetal TingoteNo ratings yet

- Perspective in PharmacyDocument6 pagesPerspective in PharmacyShella Mae Duclayan RingorNo ratings yet

- IMCI Plan C 2013Document51 pagesIMCI Plan C 2013Suhazeli AbdullahNo ratings yet

- Zoonoses 8Document404 pagesZoonoses 8Cagar Irwin Taufan0% (1)

- Specific Criteria Nabl-112 (2012)Document53 pagesSpecific Criteria Nabl-112 (2012)kinnusaraiNo ratings yet

- 10.1177 2192568217717972 PDFDocument4 pages10.1177 2192568217717972 PDFEnrique CalvoNo ratings yet

- DR. NOEL CASUMPANG vs. CORTEJODocument15 pagesDR. NOEL CASUMPANG vs. CORTEJOAngelica de LeonNo ratings yet

- 795 USP Proposed 2019 Revision 2018-05-30Document43 pages795 USP Proposed 2019 Revision 2018-05-30Michael FreudigerNo ratings yet

- PT of The Shoulder PDFDocument573 pagesPT of The Shoulder PDFMuhammad Salman AzimNo ratings yet

- Daftar Pustaka Tumor WilmsDocument2 pagesDaftar Pustaka Tumor WilmshariyatiNo ratings yet

- Hemmingsen-2021-The Expanded Role of ChitosanDocument53 pagesHemmingsen-2021-The Expanded Role of ChitosanISRAELNo ratings yet