Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Barakat II-Settlement of Disputes Concerning Cultural Objects

Barakat II-Settlement of Disputes Concerning Cultural Objects

Uploaded by

Tamara Zelenovic VasiljevicCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5823)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Eucharistic Miracles of The WorldDocument2 pagesThe Eucharistic Miracles of The WorldFrancisco MartinezNo ratings yet

- DIY MAP Your Soul Plan Chart: T/DR Markus Van Der WesthuizenDocument14 pagesDIY MAP Your Soul Plan Chart: T/DR Markus Van Der WesthuizenValentin Mihai100% (4)

- 1 - Investment Banking and BrokerageDocument152 pages1 - Investment Banking and BrokerageLordie BlueNo ratings yet

- 3 Steps To 2000Document240 pages3 Steps To 2000Eduardo APNo ratings yet

- Lesson 5 - Cultural Property Regulation& National and International Heritage Legislation. International Protection of Cultural PropertyDocument16 pagesLesson 5 - Cultural Property Regulation& National and International Heritage Legislation. International Protection of Cultural PropertyTamara Zelenovic VasiljevicNo ratings yet

- Bachelor Degree TimetableDocument20 pagesBachelor Degree Timetablebite meNo ratings yet

- Weller Dispute Settlement II - ADRDocument38 pagesWeller Dispute Settlement II - ADRTamara Zelenovic VasiljevicNo ratings yet

- Cassirer v. Thyssen Bornemisza 9th Cirpdf-Settlement of Disputes Concerning Cultural ObjectsDocument38 pagesCassirer v. Thyssen Bornemisza 9th Cirpdf-Settlement of Disputes Concerning Cultural ObjectsTamara Zelenovic VasiljevicNo ratings yet

- Autocephalous Church-Settlement of Disputes Concerning Cultural ObjectsDocument20 pagesAutocephalous Church-Settlement of Disputes Concerning Cultural ObjectsTamara Zelenovic VasiljevicNo ratings yet

- Wertheimer-Settlement of Disputes Concerning Cultural ObjectsDocument6 pagesWertheimer-Settlement of Disputes Concerning Cultural ObjectsTamara Zelenovic VasiljevicNo ratings yet

- DDI Zonulin WP - R2Document8 pagesDDI Zonulin WP - R2Tamara Zelenovic VasiljevicNo ratings yet

- Arts ManagementDocument46 pagesArts ManagementTamara Zelenovic VasiljevicNo ratings yet

- Tools For Landfill SitingDocument8 pagesTools For Landfill SitingTamara Zelenovic VasiljevicNo ratings yet

- Art 20199983Document3 pagesArt 20199983Devaki SubasriNo ratings yet

- TTL - Lesson Plan - Harvey - IbeDocument12 pagesTTL - Lesson Plan - Harvey - IbeHarvey Kurt IbeNo ratings yet

- Ciep 257 - Turma 1017Document14 pagesCiep 257 - Turma 1017Rafael LimaNo ratings yet

- Damped HoDocument3 pagesDamped Homani kandanNo ratings yet

- Kerala Agricultural University: Main Campus, Vellanikkara, Thrissur - 680 656, KeralaDocument3 pagesKerala Agricultural University: Main Campus, Vellanikkara, Thrissur - 680 656, KeralaAyyoobNo ratings yet

- Data Analytics For Accounting 1st Edition Richardson Solutions ManualDocument25 pagesData Analytics For Accounting 1st Edition Richardson Solutions ManualRhondaHogancank100% (51)

- Worksheet 2.4 Object-Oriented Paradigm InheritanceDocument7 pagesWorksheet 2.4 Object-Oriented Paradigm InheritanceLorena FajardoNo ratings yet

- A La CarteDocument3 pagesA La CarteJyot SoodNo ratings yet

- Metal Finishing 2010 PDFDocument740 pagesMetal Finishing 2010 PDFJuan Ignacio Alvarez Herrera100% (2)

- Unit 7 7.2 Key ConceptsDocument3 pagesUnit 7 7.2 Key ConceptsCésar RubioNo ratings yet

- A Flangeless Complete Denture Prosthesis A Case Report April 2017 7862206681 3603082Document2 pagesA Flangeless Complete Denture Prosthesis A Case Report April 2017 7862206681 3603082wdyNo ratings yet

- PowerSCADA Expert System Integrators Manual v7.30Document260 pagesPowerSCADA Expert System Integrators Manual v7.30Hutch WoNo ratings yet

- Steegmuller - Flaubert and Madame Bovary - A Double Portrait-Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (1977)Document378 pagesSteegmuller - Flaubert and Madame Bovary - A Double Portrait-Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (1977)Jorge Uribe100% (2)

- Partograph 3Document49 pagesPartograph 3Geeta BhardwajNo ratings yet

- ACOSTA, Josef De. Historia Natural y Moral de Las IndiasDocument1,022 pagesACOSTA, Josef De. Historia Natural y Moral de Las IndiasJosé Antonio M. Ameijeiras100% (1)

- MatricDocument91 pagesMatricKhalil AhmedNo ratings yet

- Chapter Vii - Ethics For CriminologistsDocument6 pagesChapter Vii - Ethics For CriminologistsMarlboro BlackNo ratings yet

- NCAA Division IDocument48 pagesNCAA Division IEndhy Wisnu Novindra0% (1)

- DS Dragon Quest IXDocument40 pagesDS Dragon Quest IXrichard224356No ratings yet

- Gpsmap 8500 Installation Instructions: Registering Your DeviceDocument12 pagesGpsmap 8500 Installation Instructions: Registering Your DeviceGary GouveiaNo ratings yet

- Untitled DocumentDocument2 pagesUntitled DocumentPeter Jun ParkNo ratings yet

- Smart Factories - Manufacturing Environments and Systems of The FutureDocument5 pagesSmart Factories - Manufacturing Environments and Systems of The FuturebenozamanNo ratings yet

- TheSun 2009-04-10 Page04 Independents Can Keep Seats CourtDocument1 pageTheSun 2009-04-10 Page04 Independents Can Keep Seats CourtImpulsive collectorNo ratings yet

- Rakeshkaydalwar Welcome LetterDocument3 pagesRakeshkaydalwar Welcome LetterrakeshkaydalwarNo ratings yet

- Accounting Group AssignmentDocument10 pagesAccounting Group AssignmentHailuNo ratings yet

Barakat II-Settlement of Disputes Concerning Cultural Objects

Barakat II-Settlement of Disputes Concerning Cultural Objects

Uploaded by

Tamara Zelenovic VasiljevicOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Barakat II-Settlement of Disputes Concerning Cultural Objects

Barakat II-Settlement of Disputes Concerning Cultural Objects

Uploaded by

Tamara Zelenovic VasiljevicCopyright:

Available Formats

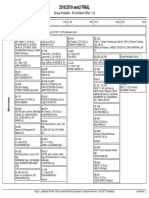

2007 WL 4368237 FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Page 1

2007 WL 4368237 (CA (Civ Div)), [2008] 1 All E.R. 1177, [2007] 2 C.L.C. 994, (2008) 152 S.J.L.B. 29, 1-07-2008

Times 4368,237, [2007] EWCA Civ 1374

countries seeking the return of valuable antiquities

Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran v. The that form part of their national heritage.

Barakat Galleries Limited

Case No: A2/2007/0902/QBENF 2 The unlawful excavation and trafficking of an-

A2/2007/0902(A)/FC3 tiquities has become very big business. In 1970 the

[2007] EWCA Civ 1374 signatories to the UNESCO Convention on

the means of prohibiting and preventing the illicit

Court of Appeal (Civil Division) import, export and transfer of ownership of cultural

CA (Civ Div) property (ratified by the United Kingdom in 2002)

Before: The Lord Chief Justice of England and recognised not only that it was incumbent on every

Wales The Right State to protect the cultural property within its bor-

Honourable Lord Justice Wall and The Right ders against the dangers of theft, clandestine excav-

Honourable Lord Justice Lawrence ation and illicit export, but also that it was essential

Collins for every State to become alive to the moral obliga-

Date: 21/12/2007, Hearing dates: 9th and 10th Oc- tions to respect the cultural heritage of all nations

tober 2007 and that the protection of cultural heritage could

On Appeal from only be effective if organised both nationally and

The Honourable Mr Justice Gray internationally among States working in close co-

TLQ/06/0601 operation (recitals 3, 4 and 7). In the Supreme

Representation Court of Ireland, Finlay CJ said that it was univer-

sally accepted that one of the most important na-

Sir Sydney Kentridge QC , Norman

tional assets belonging to the people is their herit-

Palmer and David Scannell (instructed

age and the objects which constituted keys to their

by Messrs Withers LLP ) for the Appellant.

ancient history; and that a necessary ingredient of

Philip Shepherd QC and David Her- sovereignty in a modern State was and should be an

bert (instructed by Messrs Lane & Partners ownership by the State of objects which constitute

LLP ) for the Respondent. antiquities of importance which were discovered

and which had no known owner: Webb v. Ireland

Approved Judgment [1988] I.R. 353 at 383.

Lord Phillips of Worth Matravers CJ: 3 On this appeal Iran seeks to assert its ownership

of antiquities which are almost 5,000 years old. The

Introduction appeal raises questions which were left unsettled by

Att-Gen of New Zealand v Ortiz [1984] AC 1 (CA

1 This is the judgment of the court, to which all of

and HL) on the recognition or enforcement

its members have contributed, on an appeal from a

of foreign national heritage laws. Since the de-

judgment of Gray J dated 29 March 2007 on a trial

cisions of the Court of Appeal in 1982 and of the

of two preliminary issues in an action brought by

House of Lords in 1983, the United Kingdom has

the appellant ("Iran") to recover antiquities alleged

ratified the UNESCO Convention of 1970 .

to form part of Iran's national heritage. Gray J de-

cided those issues in favour of the respondent 4 The antiquities consist of eighteen carved jars,

("Barakat"). His findings are fatal to the claim. He bowls and cups made from chlorite ("the Objects").

gave permission to appeal because of the import- Iran alleges that they date from the period 3000 BC

ance of the issues not only to Iran but to other to 2000 BC and originate from recent excavations

© 2008 Thomson Reuters/West. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

2007 WL 4368237 FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Page 2

2007 WL 4368237 (CA (Civ Div)), [2008] 1 All E.R. 1177, [2007] 2 C.L.C. 994, (2008) 152 S.J.L.B. 29, 1-07-2008

Times 4368,237, [2007] EWCA Civ 1374

in the Jiroft region of Iran which were unlicensed Iran in relation to the antiquities, such law was a

and unlawful under the law of Iran. The origin of penal or public law and thus one that was not en-

the antiquities is denied by Barakat, but Iran's alleg- forceable in this jurisdiction. As the judge had

ations are assumed to be correct for the purpose of answered the first question in the negative, this

the preliminary issues. question proved to be academic. The judge non-

etheless gave it brief consideration. He concluded

5 Barakat has a gallery in London, from which it that the relevant Iranian law relied upon by Iran

trades in ancient art and antiquities from around the was both penal and public in character and that, ac-

world. It has the antiquities in its possession in cordingly, it could not be enforced in this country

London. It claims to have purchased them in or relied upon to found Iran's claim to relief. This

France, Germany and Switzerland under laws also was a conclusion which the judge described

which have given it good title to them. Iran does (para 100) as "a regrettable one", and added

not accept this. For the purpose of the preliminary (presumably not having been informed that the

issues Iran can advance no title to the antiquities United Kingdom had ratified the UNESCO Con-

other than that of their possession. vention ) that the answer might be the one

given by Lord Denning MR in the Ortiz

6 The preliminary issues that were ordered to be

case, namely an international convention on the

tried were as follows:

subject.

i) Whether under the provisions of Iranian law

pleaded in the Amended Particulars of Claim, the 9 The judge heard evidence from two experts on Ir-

claimant can show that it has obtained title to the anian law. Professor Muhammad Taleghany gave

Objects as a matter of Iranian law and if so by what evidence for Iran and Mr Hamid Sabi for Barakat.

means, and They were agreed as to the relevant statutory provi-

ii) If the claimant can show that it has obtained sions of Iranian law but differed as to their effect.

such title under Iranian law, whether this court Professor Taleghany stated that they reflected the

should recognise and/or enforce that title. fact that the antiquities were owned by Iran. Mr

Sabi stated that they did not. The judge concluded

7 The first question reflected the fact that it was

that Mr Sabi's opinion was to be preferred to that of

common ground between the parties that the ques-

Professor Taleghany. He concluded, accordingly,

tion of title to the antiquities fell to be determined

that Iran had no proprietary title to the antiquities.

according to Iranian law, as being the lex

The judge went on to hold that Iranian law gave Ir-

situs of the antiquities at the time of deriva-

an an immediate right to possession of the antiquit-

tion of such title. Iran's primary case was that Irani-

ies, but that as this was not a proprietary right it

an law vested in Iran a proprietary title to the an-

could not found a claim for conversion or wrongful

tiquities that entitled Iran to recover them in pro-

interference with the goods.

ceedings in England. It developed, however, an al-

ternative case that Iranian law gave Iran an "immedi- 10 By this appeal Iran contends that the judge

ate right to possession" of the antiquities that foun- wrongly failed to hold that Iran has a proprietary

ded a claim in England for conversion or wrongful title to the antiquities that entitles Iran to recover

interference with the goods. Barakat successfully them. Alternatively, Iran contends that its immedi-

challenged both contentions. Accordingly the judge ate right to possession of the antiquities can prop-

answered the first question in the negative "with erly found a claim for conversion or wrongful inter-

some regret" (para 59). ference with goods. Barakat seeks to uphold the

judge's decision for the reasons that he gave save

8 The second question reflected Barakat's conten-

that, by a Respondent's, notice it challenges the

tion that, if Iranian law did confer any right upon

© 2008 Thomson Reuters/West. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

2007 WL 4368237 FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Page 3

2007 WL 4368237 (CA (Civ Div)), [2008] 1 All E.R. 1177, [2007] 2 C.L.C. 994, (2008) 152 S.J.L.B. 29, 1-07-2008

Times 4368,237, [2007] EWCA Civ 1374

judge's finding that Iranian law gives Iran an imme- double liability of the wrongdoer which can arise--

diate right to possession of the antiquities. (a) where one or two or more rights of action for

wrongful interference is founded on a possessory

11 We propose to approach the issues raised by this title, or

appeal in the following order: (b) where the measure of damages in an action

i) What is the interest in moveable property that for wrongful interference founded on a proprietary

a claimant must show in order to found a claim in title is or includes the entire value of the goods, al-

conversion in this jurisdiction? though the interest is one of two or more interests

ii) What, if any, interest in the antiquities does in the goods.

Iran enjoy? (2) In proceedings to which any two or more

iii) Does that right found a cause of action in claimants are parties, the relief shall be such as to

conversion under English law? avoid double liability of the wrongdoer as between

those claimants."

What interest in moveable property founds a

cause of action in conversion under English law? 15 The Act does not define "possessory title" or

"proprietary title" and difficulty in this area of the

12 Iran's claim is brought in conversion, as pre-

law arises because of an overlap between the two.

served by the Torts (Interference with Goods) Act

Originally the common law did not differentiate

1977 . Section 1 of that Act

between possessory title and proprietary title. Pos-

provides:

session of a chattel gave title to it. Where there was

"Definition of 'wrongful interference with goods'

an involuntary transfer of possession, as a result for

In this Act 'wrongful interference' or 'wrongful

instance of loss or theft of the chattel, the person

interference with goods', means--

who had first possessed the chattel would have a

(a) conversion of goods (also called trover),

superior title to the subsequent possessor. The sub-

(b) trespass to goods,

sequent possessor would have good title against all

(c) negligence so far as it results in damage to

the world, save the earlier possessor. Each pos-

goods or to an interest in goods;

sessor could assert against a third party who in-

(d) subject to section 2, any other tort so far as it

terfered with the chattel that he enjoyed an immedi-

results in damage to goods or to an interest in

ate right to possession.

goods."

16 Interests in a chattel can be shared and it is this

13 Section 2 of the Act provides:

fact that has given rise to the distinction between

"Abolition of detinue

proprietary and possessory title. Thus where an

(1) Detinue is abolished.

earlier possessor (the bailor) grants possession to a

(2) An action lies in conversion for loss or de-

subsequent possessor (the bailee) on terms that re-

struction of goods which a bailee has allowed to

serve to the bailor a reversionary interest in the

happen in breach of his duty to his bailor (that is to

chattel, the bailor can be said to enjoy a "propriet-

say it lies in a case which is not otherwise conver-

ary title" and the bailee a "possessory" title in the

sion, but would have been detinue before detinue

chattel. Wrongful interference with the chattel can

was abolished)."

then be detrimental to the interests of both.

14 The Act recognises that it is possible to enjoy

17 Wrongful interference with a chattel used to

different interests in goods. Thus section 7

give rise to two different causes of action, which

provides:

were largely concurrent. Detinue, which was an in-

"Double liability

terference with the proprietary right of the claimant

(1) In this section 'double liability' means the

and conversion, which was an interference with the

© 2008 Thomson Reuters/West. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

2007 WL 4368237 FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Page 4

2007 WL 4368237 (CA (Civ Div)), [2008] 1 All E.R. 1177, [2007] 2 C.L.C. 994, (2008) 152 S.J.L.B. 29, 1-07-2008

Times 4368,237, [2007] EWCA Civ 1374

possessory right of the claimant. Where goods in that a mere contractual right to possess will suffice

possession of a bailee were lost or destroyed as a to sue in conversion, and that the claimant's right of

result of breach of his duty to the bailor, the appro- possession need not derive from a proprietary in-

priate claim, before the 1977 Act, lay in detinue terest in the chattel."

rather than conversion. Where, however, the claim

was brought by the possessor against a third party 21 These propositions receive support from the fol-

wrongdoer a claim would lie either in detinue or in lowing statements in textbooks covering the sub-

conversion. ject:

(1) Salmond, Law of Torts , 21st ed.

18 A person in possession of a chattel can bring an 1996, p. 108: "Whenever goods have been conver-

action in conversion against a person who wrong- ted, an action will lie at the suit of any person in ac-

fully deprives him of that possession. tual possession or entitled at the time of conversion

to the immediate possession of them."

19 Controversy exists as to the position where "A" (2) Winfield and Jolowicz, Tort , 17th

who is in possession of a chattel, or who is entitled ed. 2006, at p. 762 states that a claimant can main-

to immediate possession of the chattel, agrees that tain conversion if at the time of the defendant's act

another ("B") may enter into possession of the chat- he had an immediate right to possess the goods

tel. Can B rely upon his contractual right to imme- "without either ownership or actual possession".

diate possession to found an action in conversion (3) Markesinis and Deakin, Tort Law ,

against C who wrongly interferes with the chattel? 5th ed. 2003, at p.436: "[i]n order to be able to sue

If by the agreement A has transferred to B not [in conversion] the plaintiff must have the right to

merely the right to enter into possession, but the any one of ownership, possession, or the immediate

ownership that A enjoyed, so that B enjoys both right to possess".

proprietary title and an immediate right to posses- (4) F. H. Lawson, Remedies of English

sion, he will be entitled to sue in conversion. If, Law , 2nd ed. 1980, at p. 122: "In eject-

however, A has retained his proprietary title, it is ment and conversion [the claimant] must prove his

not clear that B can rely on his contractual right to title, that is to say that he has a right to the immedi-

enter into immediate possession to found a claim in ate possession of the land or chattel."

conversion. It is Iran's case that he can; it is

Barakat's case that he cannot. 22 These unqualified statements that an immediate

right to possession will suffice to found a cause of

20 The reissue of the 4th edition of Halsbury's action in conversion are to be contrasted with the

Laws of England, volume 45 (2) states: view of the editors of the 19th edition of Clerk &

559. Right of possession and propertyTo sue in Lindsell, Torts (para 17-59:

conversion a claimant must show that he had either "Claimant's right must be proprietaryFor these

possession, or an immediate right to possession, of purposes, it seems that the immediate right to pos-

the chattel at the time of the act in question. Either session on which the owner relies must be a propri-

relationship with the chattel affords the necessary etary right; a mere contractual right will not do."

possessory title to sustain a claim for conversion. If Two authorities are cited in support of this pro-

either is shown, the claimant need not be the owner position, Jarvis v Williams [1955] 1 WLR

of the chattel in order to succeed in conversion; in- 71 ; International Factors v Rodriguez

deed an owner can be liable in conversion to a per- [1979] 1 QB 351 . The judge considered

son who had either possession or the immediate these authorities and held that they supported the

right of possession at the time of the owner's act. passage in Clerk and Lindsell. He concluded (at

... para 71):

560. Contractual right of possessionIt appears

© 2008 Thomson Reuters/West. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

2007 WL 4368237 FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Page 5

2007 WL 4368237 (CA (Civ Div)), [2008] 1 All E.R. 1177, [2007] 2 C.L.C. 994, (2008) 152 S.J.L.B. 29, 1-07-2008

Times 4368,237, [2007] EWCA Civ 1374

"For these reasons I am satisfied that Iran is re- tinued (at 75):

quired in the present case to establish the propriet- "Although it is, no doubt, true in a sense, and

ary nature of its right to possession of the antiquit- certainly in its original medieval conception, that

ies which is required in order for an action in con- when speaking of property in chattels there is in

version or for wrongful interference with goods to mind the right to their immediate possession, never-

succeed. For the reasons which I have already giv- theless the sense of property in chattels is now well

en, this is something which Iran is unable to do." understood. It is involved in the Sale of Goods Act,

1893 , itself. Even though, by contract

23 Jarvis v Williams [1955] 1 WLR 71 in- between himself and Paterson, the plaintiff may

volved a claim in detinue. Paterson ordered some have had a right which, if infringed, could form the

bathroom fittings from the plaintiff, Jarvis. At his subject-matter of an action for breach of contract,

request Jarvis delivered them to the premises of the and though he had a right to go and possess himself

defendant Williams. Paterson did not pay for the of these goods, nevertheless, until he has done so,

goods and agreed that Jarvis could take them back. there was in him according to my construction of

Williams refused to permit Jarvis to collect the fit- the arrangement, no proprietary interest in the

tings and Jarvis brought an action against him. The goods, in the sense in which that term is now, as I

judge held that he had a good claim. The Court of think, commonly understood. It seems to me there-

Appeal reversed this finding. fore, that he had not, on the authorities which I

have mentioned, the necessary foundation on which

24 After reference to the relevant part of the judg-

to sustain an action for detinue against the defend-

ment at first instance, Lord Evershed MR held (at

ant. He, no doubt, could sue Paterson either for the

74):

price of goods or for damages for breach of this ar-

"I take that to mean that the contractual right

rangement for the return of the goods when the de-

which the plaintiff had vis-à-vis Paterson to go and

fendant refused to deliver them over. But I think

collect these goods from Paterson's agent was a

that the rights of the plaintiff as regards these goods

right of a sufficient character to enable the plaintiff

were not such as entitled him to bring an action in

to bring an action in detinue against the agent of the

detinue against the defendant, in whose possession

owner of the property in these goods. But, with all

they were, as agent, at the time, of the person in

respect to the county court judge, I am unable to ac-

whom the property in the goods was then vested."

cept that as a good proposition of law. Certain

classes of persons, as for example bailees, have, no 26 In their skeleton argument, counsel for Iran

doubt, a special right to sustain actions in trover sought to distinguish this case on the basis that it

and detinue, but the general rule is, I think, cor- referred to a claim in detinue, not a claim in con-

rectly stated in the text of Halsbury's Laws of Eng- version. Lord Evershed's citation from Halsbury

land, 2nd ed., vol.33 at p. 62, para. 98. 'In order to suggests that he was drawing no such distinction.

maintain an action of trover or detinue a person Jarvis v Williams is a difficult case to ana-

must have the right of possession and a right of lyse. Both the County Court Judge and the Court of

property in the goods at the time of the conversion Appeal were prepared to proceed on the basis that

or detention; and he cannot sue if he has parted the plaintiff had a contractual right to collect the

with the property in the goods at the time of the al- goods from the defendant, but the precise nature of

leged conversion, or if at the time of the alleged the contract is not spelt out. If a contractual analys-

conversion his title to the goods has been divested is is appropriate, we think that the contract was a

by a disposition which is valid under the Factors conditional contract under which it was agreed that,

Act, 1889 ."' if the plaintiff recovered possession of the goods,

he would receive them in discharge of Paterson's

25 After reference to authority, Lord Evershed con-

© 2008 Thomson Reuters/West. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

2007 WL 4368237 FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Page 6

2007 WL 4368237 (CA (Civ Div)), [2008] 1 All E.R. 1177, [2007] 2 C.L.C. 994, (2008) 152 S.J.L.B. 29, 1-07-2008

Times 4368,237, [2007] EWCA Civ 1374

obligation to pay for them. It was not a contract un- 675 . The relevant issue was whether an

der which Paterson purported to transfer to the equitable title in share certificates could found a

plaintiff his immediate right to the possession of the claim in conversion. The court held that it could

goods. While the passage that we have quoted from not, and disapproved the significance that Sir David

the judgment of Lord Evershed certainly supports Cairns appeared to have attached to the plaintiffs'

Barakat's case, we do not consider that, when the equitable interest in the cheques in that case. Mum-

facts of the case are considered, it can safely be mery LJ expressed the view that this was not neces-

treated as binding precedent for the proposition that sary to the decision. Pill and Hobhouse LJJ agreed.

a contractual right to immediate possession can The latter observed (at 700 and 701):

never found a claim in conversion. "Buckley LJ decided the case on the basis of a

common law possessory title as bailee giving the

27 Iran's skeleton argues that, in so far as Lord immediate right to possession ... For a plaintiff to

Evershed's reasoning extended to the tort of conver- succeed in an action in conversion he must show

sion, it should not be followed because it is in con- that in law he had the requisite possessory title,

flict with more recent authorities. We turn to con- either actual possession or the right to immediate

sider some of these. possession. Where a plaintiff is the legal owner of

the relevant chattel he will normally be entitled to

28 Sir David Cairns purported to follow Jarvis v

sue in conversion even if he was not at the relevant

Williams when giving the leading judgment

time in possession of the chattel. But where there is

in International Factors v Rodriguez [1979] 1 QB

a person who has a subsisting right to the immedi-

351 . That case involved a factoring agree-

ate possession of the chattel, he may sue even the

ment under which the plaintiffs had purchased the

owner of the chattel for wrongfully interfering with

book debts of a company of which the defendant

his right."

was a director. The agreement provided that if any

cheque was paid to the company rather than to the 30 There is thus a conflict between Jarvis v Willi-

plaintiffs, it should be held in trust for the plaintiffs ams and International Factors v Rodrig-

and transferred to them. In breach of this agreement uez , as explained in MCC Proceeds v Leh-

the defendant caused four such cheques to be paid man Brothers . Where the owner of goods

into the company's bank account. The plaintiffs' ac- who has an immediate right to possession of them,

tion in conversion succeeded. Sir David held that albeit that they are in the possession of a third

Jarvis v Williams established that a claimant in party, by agreement transfers his title to a new own-

conversion had to show not merely an immediate er, the new owner can bring a claim in conversion

right to possession but a proprietary interest in the against the person in whose possession they are.

subject matter of the claim. This requirement was, Where the owner of goods with an immediate right

however, satisfied by the plaintiffs' equitable in- to possession of them by contract transfers the latter

terest in the cheques. Bridge LJ stated that he right to another, so that he no longer has an imme-

agreed. Buckley LJ held, however, that the contrac- diate right to possession, but retains ownership, it

tual right of the plaintiffs to demand immediate de- would seem right in principle that the transferee

livery of the cheques sufficed to found a claim in should be entitled to sue in conversion. A

conversion, whether or not an immediate trust at- fortiori if the contract provides that when

tached to the cheques. the transferee enters into possession, ownership

will be transferred to him. We consider that this ac-

29 International Factors v Rodriguez re-

cords with the weight of academic opinion and can

ceived consideration by all three members of the

be reconciled with the facts of Jarvis v Willi-

Court of Appeal in MCC Proceeds Inc v Lehman

ams .

Brothers International (Europe) [1998] 4 All ER

© 2008 Thomson Reuters/West. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

2007 WL 4368237 FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Page 7

2007 WL 4368237 (CA (Civ Div)), [2008] 1 All E.R. 1177, [2007] 2 C.L.C. 994, (2008) 152 S.J.L.B. 29, 1-07-2008

Times 4368,237, [2007] EWCA Civ 1374

31 Contractual transfer of rights is far removed some stage and by some means a transfer to the

from the facts of this case. The judge concluded, on state or government of Iran of property rights previ-

the strength of Jarvis v Williams , that a ously owned by the king, these constitutional provi-

claimant in conversion must demonstrate some pro- sions form no part of Iran's case in these proceed-

prietary right in the goods and that Iran could not ings.

do so. We now turn to consider whether Iran has

any interest in the antiquities and, if so, the nature The Civil Code

of such interest.

36 In chronological order, the first statutory provi-

Iran's interest in the antiquities under Iranian sion which is relied on by Iran is the Civil

law Code by which in and after 1928 the main

civil laws of Iran were codified. The Civil

32 It was common ground that the relevant law is to Code is divided into sections. The provi-

be found in provisions of Iranian statute law. The sions which are said to touch upon the issue of

judge set these out at length and we shall incorpor- ownership of the antiquities are the following:

ate, in his own words, the passages of his judgment

in which he did so. Section 3 On Properties Which Have No Private

Owner

33 The appropriate starting point appears to date

back to what is called the Constitutional Movement ...

which developed in Iran. At paragraph 8 of his ex- Article 26 -- (As amended on 21-8-1370 A.H,

pert report Professor Taleghany says: "Since time equivalent to 12-11-1991) Government properties

immemorial Iran was ruled by absolute monarchs. which are capable of public service or utilisation,

The kingdom of Iran was the king's domain, i.e. his such as fortifications, fortresses, moats, military

estate. It was as such that the kings acquired further earthworks, arsenals, weapons stored, warships and

territories, ceded territories and exchanged part of also government furniture, mansions and buildings,

their kingdom with the neighbouring kings. The last government telegraph wires, public museums and

evidence of the exercise of such power was exhib- libraries, historical monuments and similar proper-

ited in 1893. However, a short while after this date ties and, in brief, any movable and immovable

there was a Constitutional Movement in Iran and properties which may be in the possession of the

the king's domain became the Crown's, or govern- government for public expediency and national in-

ment property. When the Iranian main laws were terest, may not privately be owned. The same ap-

codified in the Civil Code of Iran (section 1 plies to properties that have, in the public interest,

of which was approved in 1928) the internal 'gov- been allocated to a province, county, region or

ernment properties' legally replaced the king's do- town.

main".

Chapter 2 On Various Rights that

34 By a Royal Proclamation dated 5 August 1906

People May Have in Properties

the so-called "Bases of the Persian Constitution"

were promulgated. They include what are described ...

as "The Fundamental Laws of December 30 1906",

which include Articles dealing with the duties, lim- Section 1 On Ownership

itations and the rights of the National Consultative

Assembly. Article 30 -- Every owner has the right to all

kind of disposal and exploitation of his property,

35 Despite the fact that there would have been at except where the law expressly provides otherwise.

© 2008 Thomson Reuters/West. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

2007 WL 4368237 FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Page 8

2007 WL 4368237 (CA (Civ Div)), [2008] 1 All E.R. 1177, [2007] 2 C.L.C. 994, (2008) 152 S.J.L.B. 29, 1-07-2008

Times 4368,237, [2007] EWCA Civ 1374

Article 31 -- No property may be taken out of its usurper, but if he destroys the said property or

owner's possession except by the order of law. causes its destruction, he shall be liable.

... ....

Article 35 -- Possession indicating ownership is Article 317 -- The owner can claim the usurped

proof of ownership unless the contrary is proved. property or, if it is lost, its equivalent or the value

Article 36 -- Possession which is proved not to of the whole or part of the usurped property from

have derived from a valid title or lawful transfer either from the original or successive usurpers at

shall not be valid. his option.

Chapter 4 On Found Articles and Lost Animals The National Heritage Protection Act 1930

Section 1 On Found Articles 37 Shortly after the enactment of the Civil

Code , a specific Act was passed on 3

Article 165 --Anyone who finds an article in the November 1930 entitled National Heritage Protec-

desert or in a ruined place which is not inhabited tion Act . This Act provides for an invent-

and which is not privately owned, may take owner- ory to be built up by the State including all the

ship of it and there is no need to declare it; unless it known and distinguished items of national heritage

is evident that the article belongs to modern times, of Iran which possess historical, scientific or artist-

in which case it is subject to the rules applicable to ic respect and prestige. Provision is also made for

articles found in an inhabited locality. the registration of both immovable and movable

properties. Article 3 expressly recognises that some

Chapter 5 On Treasure Trove

property registered on the inventory will be

Article 173 -- Treasure trove means valuables privately owned. Articles 4 to 6 inclusive deal with

buried in the ground or in a building and found by immovable property. Article 7 and following deal

chance or accidentally. with movable property. Article 9 obliges the owner

Article 174 -- Treasure trove whose owner is not of a movable property registered in the List for Na-

known is the property of the finder. tional Heritage to inform the pertinent government-

Article 175 -- If a person finds treasure trove in al organisation before selling any such property to

the property of another person, he must inform the another person. According to that Article the state

owner of the property. If the owner of the property possesses what is described as "the pre-emption

claims ownership of the treasure trove and proves right". A person who sells a property registered in

it, the treasure trove belongs to the person claiming the List without notifying the Ministry is liable to a

ownership. fine for as much as the selling price of the property.

Article 176 -- Treasure trove found in ownerless The government is entitled to withdraw the prop-

land belongs to the person who finds it. erty from the new owner on refunding the paid

price to the new owner.

Section 2 On Tortious Liability

38 Amongst the potentially material provisions to

Subsection 1 On Usurpation be found in the 1930 Act are the following:

Article 1 Observing the Article 3 of this Law, all

Article 308 -- Usurpation is the assumption of artifacts, Buildings and places having been estab-

another's right by force. Laying hands on another lished before the end of Zandieh Dynasty in Iran

person's property is also considered usurpation. [late 19th Century], either movable or immovable,

Article 309 -- If a person prevents an owner from may be considered as national heritage of Iran and

possessory treatment of his property without him- shall be protected under the State control.

self assuming control of it, he is not considered a ...

© 2008 Thomson Reuters/West. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

2007 WL 4368237 FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Page 9

2007 WL 4368237 (CA (Civ Div)), [2008] 1 All E.R. 1177, [2007] 2 C.L.C. 994, (2008) 152 S.J.L.B. 29, 1-07-2008

Times 4368,237, [2007] EWCA Civ 1374

Article 9 -- The owner of a movable property -- the objects discovered during a commercial excava-

registered in the List for National Heritage -- Shall tion, what is liable to be kept in museums shall be

be obliged to inform the pertinent governmental or- appropriated, and the rest shall be transacted, by

ganization in writing before selling the property to any means the state deems proper; the State shall

another person. In case the State intends to put the put these properties to auction to be sold. ...

property among its collections of national heritage, Article 16 -- The violators of Article 10, those

it possesses the pre-emption right. ... who perform excavation operations without the

Article 10 -- Anyone who accidentally or by State permission and information, though in their

chance finds a movable property which according own lands, as well as those who illegally take items

to this Law may be considered as an item of nation- of national heritage out of the country shall be fined

al heritage, though it has been discovered in his/her as much as twenty to two thousand Tomans, and the

own property shall be obliged to inform the Min- discovered objects shall be confiscated [in Farsi, "z

istry of Education or its representatives as soon as abt "] in the interest of the State. ...

possible; in case the pertinent State authorities re- Article 17 -- Those who intend to adopt dealing

cognize the property worthy to be registered in the in antiquities as occupation should obtain permis-

List for National Heritage, half of the property or sion from the State. Furthermore taking the an-

an equitable price as considered by qualified ex- tiquities out of the country shall require permission

perts shall be transferred to the finder, and the State from the State. The registered objects in the list for

shall have the authority, at its discretion, to appro- National Heritage if attempted to be taken out of

priate or transfer the other half to the finder without the country without the permission of the State,

recompense. shall be confiscated in the interest of the State ...

Article 11 -- The State has the exclusive right

for land digging or excavation in sites to explore The Executive Regulations

national relics. ...

39 On 19th November 1932 the executive (or ad-

...

ministrative) regulations of the National Heritage

Article 13 -- Excavations in private lands shall

Protection Act of 1930 were approved by

require the owner's consent as well as the permis-

the Council of Ministers. In effect these Regula-

sion of the State ...

tions were designed to implement the provisions of

Article 14 -- During scientific and commercial

the 1930 Act. Movable property is dealt with in

excavations in one location and one season, if the

Chapter 2 (Articles 12 to 17). These in-

State discovers the objects directly, it may appro-

clude :

priate them all, and if the discovery is performed by

Article 17 -- Anyone who accidentally finds a

others, the State may choose and possess up to ten

movable property, even though it has been dis-

items out of the objects of historical artistic value;

covered in his/her own property, shall be obliged to

half of the rest of the objects shall be transferred

immediately inform the Ministry of Education

freely to the discoverer, and the other half shall be

through the nearest representative of the Depart-

appropriated by the State. In case all the discovered

ment for Education or through the Finance officers

objects do not exceed ten items and the state appro-

if there is no Department for Education. After the

priate them all, the expenses of the excavation shall

objects have been examined by the Department for

be refunded to the discoverer. ...

Antiquities, half of the items or half of the commer-

Article 15 -- The share of the state out of the ob-

cial price thereof as evaluated by qualified experts

jects discovered during a scientific excavation shall

shall be transferred to the finder, and the State shall

be kept in State collections and museums, and not

have the authority to possess or transfer the other

be sold; and the discoverer's share shall be his/her

half to the finder.

own property. Among the share of the State out of

© 2008 Thomson Reuters/West. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

2007 WL 4368237 FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Page 10

2007 WL 4368237 (CA (Civ Div)), [2008] 1 All E.R. 1177, [2007] 2 C.L.C. 994, (2008) 152 S.J.L.B. 29, 1-07-2008

Times 4368,237, [2007] EWCA Civ 1374

40 Chapter 3 of the Regulations deals with Excava- ...

tion. The provisions of this chapter include: Article 50 -- In case the State recognises that the

Article 18 -- The State possesses the exclusive registered objects in the List for National Heritage,

rights to land excavation for the purpose of obtain- for which export permission has been requested, are

ing antiquities. beneficial for developing national collections, it

... shall have the authority to purchase the objects in

Article 25 -- Excavation in private lands shall question at the price declared by the owner. Should

require the owner's consent as well as the permis- the owner refrain from selling the objects; export

sion of the State ... permits shall not be granted.

... Article 51 -- The Antiquities intended to be

Article 31 -- The manner of sharing the antiquit- taken out of the country without obtaining proper

ies discovered in a place during a season of com- permission shall be confiscated.

mercial or scientific excavation, between the excav-

ator and the State shall be as follows: The first The Legal Bill of 1979

choice of the objects discovered, up to ten items,

41 On 17 May 1979 a Legal Bill (which is accepted

shall be that of the State, and then the State shall

to have the force of law) was approved. The title of

equally share the remainder with the licence holder.

the Bill is:

Immovable antiquities shall pertain to the State and

Legal Bill Regarding Prevention of Unauthorised

not be divided. In case the discovered objects shall

Excavations and Diggings intended to obtain an-

not exceed ten items the State, by virtue of the au-

tiquities and historical relics which, according to

thority invested in it, shall possess them all and re-

international criteria, have been made or have come

fund expenses that the excavator sustained. The

into being one hundred or more years ago.

holder of the excavator licence may possess his/her

The Bill provides:

share of the antiquities recovered, provided that he/

Considering the necessity of protection of relics

she had been refunded the rental value due to the

belonging to Islamic and cultural heritage, and the

owner ...

need for protection and guarding these heritages

...

from the point of view of sociology and scientific,

Article 36 -- Any person who takes measures vi-

cultural and historical research and considering the

olating the provisions of Article 10 from the law or

need for prevention of plundering these relics and

Article 17 herein, or embark on excavation without

their export abroad, which are prohibited by nation-

securing proper permission at (sic) export antiquit-

al and international rules, the following Single Art-

ies illegally, shall be liable to a fine 20 to 2,000 To-

icle is approved.

mans, and the discovered objects shall be confis-

1 -- Undertaking any excavation and digging in-

cated by the State.

tended to obtain antiquities and historical relics is

...

absolutely forbidden and the offender shall be sen-

Article 41 -- [Provides that certain classes of an-

tenced to six months to three years correctional im-

tiquities are authorised to be traded, i.e. that they

prisonment and seizure [in Farsi "

can be bought and sold.]

zabt "] of the discovered items and

...

excavation equipment in favour of the public treas-

Article 48 -- In case the examination by Depart-

ury. If the excavation takes place in historical

ment for Antiquities proved that some of the ob-

places that have been registered in the National

jects had been illegally obtained, those objects shall

Heritage List, the offender shall be sentenced to the

be seized and confiscated by the State. The owners

maximum punishment provided (in this Section).

and exporters may be prosecuted according to the

2 -- Where the objects named in this Act have

Antiquities Act ...

© 2008 Thomson Reuters/West. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

2007 WL 4368237 FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Page 11

2007 WL 4368237 (CA (Civ Div)), [2008] 1 All E.R. 1177, [2007] 2 C.L.C. 994, (2008) 152 S.J.L.B. 29, 1-07-2008

Times 4368,237, [2007] EWCA Civ 1374

been discovered accidentally, the discoverer is duty covered from usurpers shall be at the disposal of

bound to submit them to the nearest office of Cul- the Islamic government for it to utilise in accord-

ture and Higher Education as soon as possible. In ance with the public interest. Law will specify de-

this case, a committee consisting of the Religious tailed procedures for the utilisation of each of the

Judge, local Public-Prosecutor and the director of foregoing items'. ....

the office of Culture and Higher Education, or their ...

representatives, will be formed with a specialised Article 47 [ Private Property ]

expert attending and who will examine the case and Private ownership, legitimately acquired, is to be

decide as follows: respected. The relevant criteria are determined by

A -- Where the items are discovered in a private law.

property, in the case of precious metals and jewels, ...

they will be weighed and a sum equal to twice the Article 83 [ Property of National

market value of the raw material thereof will be Heritage ]

paid to the discoverer. In the case of other objects, Government buildings and properties forming

half of the estimated price will be paid to him. part of the national heritage cannot be transferred

B -- Where the items are discovered in non- except with the approval of the Islamic Consultat-

private property, a sum equal to half of the discov- ive Assembly; that, too, is not applicable in the case

ery reward, provided for in Section A, will be paid of irreplaceable treasures.

to the discoverer

... 43 The Revolutionary Council of the Islamic Re-

public of Iran issued a decree on 29th February

3 -- Antiquities means objects that according to 1980 which prohibited export of any kind of an-

international criteria have been made or produced tiquities or artistic objects from the country.

one hundred, or more, years ago. In the case of ob-

jects whose antiquity is less than a hundred years, 44 The 5th book of Islamic Punishment Law dated

the discovered objects will belong to the discoverer May 23 1996 deals at chapter 9 with the destruction

after he has paid a fifth of their evaluated price to of historical/cultural properties. This provides, inter

the public treasury. alia:

4 -- Persons who offer the discovered objects for Article 559 -- Any person found guilty of steal-

sale or purchase in violation of the provisions of ing equipments and objects, as well as the materials

this Act will be sentenced to the penalty provided and pieces of cultural- historical monuments from

for in Section 1'. museums, exhibits, historical and religious places

or any other places which are under the protection

The New Constitution and control of the state; or trades in such objects or

conceals them -- knowing that they are stolen --

42 In the same year that the Legal Bill was ap- shall be obliged to return them and condemned to

proved, Iran on 24th October 1979 adopted a new confinement of one to five years, if not subject to

Constitution. Its many provisions include the fol- punishment for theft (as ordained by Islamic reli-

lowing: gion).

Article 45 [ Public Wealth ] ....

Public wealth and property, such as uncultivated Article 561 -- Any attempt to take historical-cul-

or abandoned land, mineral deposits, seas, lakes, tural items out of the country, even if it would not

rivers and other public waterways, mountains, val- be actually exported, shall be considered as illegal

leys, forests, marshlands, natural forests, unen- export. The violator shall be condemned to restitute

closed pastureland, legacies without heirs, property the items, imprisoned from one to three years, and

of undetermined ownership and public property re-

© 2008 Thomson Reuters/West. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

2007 WL 4368237 FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Page 12

2007 WL 4368237 (CA (Civ Div)), [2008] 1 All E.R. 1177, [2007] 2 C.L.C. 994, (2008) 152 S.J.L.B. 29, 1-07-2008

Times 4368,237, [2007] EWCA Civ 1374

fined as twice as the value of the items exported. .... to possession should be a proprietary right. The

Article 562 -- Any digging or excavation inten- judge, after consideration of authority, upheld

ded to obtain historical-cultural properties is forbid- Barakat's submission that the right to possession

den. The violator shall be condemned to undergo a must be proprietary. He held that Iran had failed to

confinement of six months to three years; the dis- establish the necessary proprietary interest, albeit

covered objects shall be confiscated in the interests that Iran did have an immediate right to possession

of The Iranian Cultural Heritage Organisation and of the antiquities which was an immediate right.

the equipments of the excavation shall be confis-

cated by the state .... Ownership of the antiquities

Note 1.Whoever obtains the historical/cultural

47 The judge started from the uncontroversial posi-

properties, that are the subject of this Article, by

tion that determination of Iranian law was a ques-

chance and does not take (the necessary) steps to

tion of fact; and that when faced with conflicting

deliver the same, according to the regulations of the

evidence of foreign law, he had to look at the effect

State Cultural Heritage Organisation, will be sen-

of the foreign sources on which the experts rely as

tenced to the seizure of the discovered (found)

part of their evidence in order to evaluate and inter-

properties.

pret that evidence and decide between the conflict-

...

ing testimony: Bumper Development Corp Ltd v

The judge's findings on title to the antiquities Commissioner of Police for the Metropolis [1991] 1

WLR 1362 , at 1368-1369. As we have said,

45 After considering the various statutory provi- the judge was assisted by expert evidence from Pro-

sions relied on by Iran, of which the Legal Bill of fessor Muhammad Taleghany on behalf of Iran and

1979 was particularly relied upon, the judge con- from Mr Hamid Sabi on behalf of Barakat. Profess-

cluded, as he put it, "with some regret" that Iran or Taleghany was a Professor of Law at Teheran

had not discharged the burden of establishing the University until 1984, when he moved to London.

ownership of the antiquities under the law of Iran. In London he was the legal adviser of the Iranian

He said (at para 59) Bureau for International Legal Services until 1994,

"I readily accept that Iran has gone to some since when he has been a consultant on Iranian law.

lengths to list and secure protection for its natural Mr Hamid Sabi was a member of the Iranian Bar.

heritage and to penalise unlawful excavators and He practised law in Iran until 1979, when he moved

exporters. But the enactments relied on by Iran fell to London, since when he has practised as a con-

short in my judgment of establishing its legal own- sultant on Iranian law. Both experts have consider-

ership of the antiquities. I am not persuaded that able experience of giving evidence on Iranian law

those enactments are in certain respects consistent in English courts.

with State ownership but, even if all of them were,

that would still in my opinion not be enough to 48 There was no judicial or academic authority on

have the effect of vesting ownership in the State, as the central question, namely whether the effect of

it were, by default of as a matter of inference." the Iranian legislation, and in particular the 1979

Legal Bill, was to vest ownership of antiquities in

The judge's finding in respect of Iran's claim the Iranian State. In choosing between the experts

based on immediate right to possession on this question, and preferring the conclusions of

Mr Sabi, the judge was not making a judgment on

46 Barakat accepted that a person with an immedi- credibility, or expertise, or any of the other matters

ate right to possession could bring a claim in con- which are normally taken into account when choos-

version or for the tort of wrongful interference with ing between expert evidence. He expressly recorded

goods subject only to the requirement that the right that he was satisfied that both experts did their best

© 2008 Thomson Reuters/West. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

2007 WL 4368237 FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Page 13

2007 WL 4368237 (CA (Civ Div)), [2008] 1 All E.R. 1177, [2007] 2 C.L.C. 994, (2008) 152 S.J.L.B. 29, 1-07-2008

Times 4368,237, [2007] EWCA Civ 1374

to assist him. tiquities, as this concept is understood by the law of

England, in Iran. Iranian law prohibits anyone other

49 In deciding whether the Republic has ownership than the Government of Iran from seeking to excav-

under Iranian law, it is important to bear in mind ate antiquities. Iranian law prohibits anyone who

that it is not the label which foreign law gives to the unlawfully excavated antiquities from acquiring

legal relationship, but its substance, which is relev- any title to them. Antiquities excavated by the Gov-

ant. If the rights given by Iranian law are equivalent ernment are owned by the Government as are an-

to ownership in English law, then English law tiquities that are excavated by anyone else. Those

would treat that as ownership for the purposes of who find antiquities by chance have to hand them

the conflict of laws. The issue with which we are over to the Government. The effect of all these laws

concerned is whether the rights enjoyed by Iran in is that the government owns the antiquities.

relation to the antiquities equate to those that give

standing to sue in conversion under English law. 54 These submissions require a detailed analysis of

the relevant provisions of Iranian statutes. We ap-

50 What the judge did was to look at the legisla- proach these having regard to two principles that

tion, and decide what its effect was by testing the are common ground. The statutes should be given a

expert evidence against its language and context. purposive interpretation and special provisions

We propose to adopt the same course. dealing with antiquities take precedence over gen-

eral provisions.

51 It was Professor Taleghany's opinion that the an-

tiquities formed part of the national heritage which The Civil Code

was originally owned by the King or Shah and

which subsequently became owned by the Republic 55 Among the provisions relied upon by Professor

of Iran. He asserted that this accorded with all the Taleghany was Article 26 of the Civil Code

relevant statutory provisions. It was Mr Sabi's opin- . The judge, preferring the evidence of Mr Sabi,

ion that ownership of the antiquities was governed held that movable antiquities did not fall within the

by express provisions of the Iranian Civil description "historical monuments and similar prop-

Code . These vested ownership of the an- erty", nor within the description "in use by the Gov-

tiquities in the finders. These provisions remained ernment for the service of the public". In any event,

binding unless expressly altered by subsequent stat- Article 26 deals only with properties in the

utory provisions. There were no such provisions. possession of the government. We endorse these

conclusions.

52 The debate before the judge focussed on the ef-

fect of the statutory provisions. The judge found 56 The judge observed that it was clear from provi-

that some of these were incompatible with Profess- sions of Chapter 2 that Iranian law both recognised

or Taleghany's opinion although he rejected the and respected private ownership. That proposition

suggestion that this opinion had not been object- has not been in issue. He commented that Article

ively formed. He held that Iran had failed to dis- 35 created a presumption in favour of the

charge the burden of proving that, under Iranian possessor as to the ownership of property. He did

law, the antiquities were property of the Republic. not comment on Article 36 . It does not

Mr Philip Shepherd QC for Iran supports the seem to us that that Article bears directly on wheth-

judge's conclusions. er the antiquities are vested in Iran, although it is

not readily reconciled with the proposition, ad-

53 For Iran Sir Sydney Kentridge QC submits that vanced by Mr Sabi, that someone who finds an-

the cumulative effect of the relevant Iranian stat- tiquities in the course of unlawful excavation ob-

utory provisions is to vest ownership of the an- tains title to them.

© 2008 Thomson Reuters/West. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

2007 WL 4368237 FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Page 14

2007 WL 4368237 (CA (Civ Div)), [2008] 1 All E.R. 1177, [2007] 2 C.L.C. 994, (2008) 152 S.J.L.B. 29, 1-07-2008

Times 4368,237, [2007] EWCA Civ 1374

57 It is common ground that the antiquities do not 61 Article 14, as explained by Article 31 of the

constitute treasure trove. The judge nonetheless re- Regulations, appears to us to vest the State's share

marked that both Article 165 and Articles 174- in the State as owner, rather than mere possessor.

176 lent some support to Barakat's assertion This is also to be inferred from the reference in Art-

that the Civil Code provided for the finder icle 15 to the discoverer's share being "his/her own

of an article to become its owner. We agree with property". Article 14 gives the State the right to "ap-

that general proposition. propriate" all the objects that it discovers directly.

This might suggest that until appropriation the State

The National Heritage Protection Act 1930 does not own them.

58 The judge observed that the provisions of this 62 In summary there is a lack of clarity in these

Act were incompatible with Professor Taleghany's provisions about precisely how and when the State

broad proposition that all antiquities were owned by becomes the owner of its share of antiquities that

the State. We agree. Article 9 expressly deals with are discovered in lawful excavations. Overall we

movable property that is registered as part of the think the provisions more consistent with Mr Sabi's

National Heritage but which is privately owned. evidence that the finder is the owner unless and un-

Articles 10, 14 and 15 make provision for the State til antiquities are transferred to the State. We do not

to share with the finder antiquities that are found by consider that these difficult provisions are directly

chance or discovered during lawful excavations. relevant. We have some sympathy with Sir

Sydney's submission to us that "the State was com-

59 The judge remarked that these provisions could

ing pretty near to ownership but it is rather difficult

not be construed as conferring title to movable as-

to work out just what rights it has and what rights it

sets on the government and that they were incon-

does not have". The significance of the provisions

sistent with the government having ownership of

is that they qualify the effect of Article 165

movables. These general observations call for some

where antiquities are concerned. They vest some of

qualification.

these in the State in accordance with their terms.

60 Article 10 sets out circumstances in which the They provide background to the all important pro-

State has or acquires title to movable property. It visions of the Legal Bill of 1979.

provides that "half of the property or an equitable

The Legal Bill of 1979

price as considered by qualified experts shall be

transferred to the finder". It is implicit that if the 63 The judge observed that it was Mr Malek's case

latter option is adopted the State becomes (or re- for Iran that the Legal Bill of 1979 was the "clinch-

mains) the owner of the property in question. The ing statutory provision" and Sir Sydney adopted the

section further gives the State the option "to appro- same stance. Early in his submissions (Day 1, p 17)

priate or transfer the other half to the finder without he set out very clearly the way that he put Iran's

recompense". This gives the State the option of be- case:

coming (or remaining) the owner of the other half. "The question of whether someone is owner is

The words that we have placed in brackets reflect decided by looking at what rights that person has,

the fact that it is perhaps arguable that the language for example the right of exclusive enjoyment, the

is sufficiently imprecise to accommodate the pos- right of alienation, the right of recovering posses-

sibility that antiquities vest in the State when they sion. ... Those are the elements of ownership and it

are found -- see Article 17 of the 1932 Regulations is our submission that whatever language is used in

where the language, or perhaps the translation, of the Iranian statute -- and certainly in the Iranian

the relevant provisions is a little different. statute there is no clause which uses the term that

the antiquities vest in the Government -- nonethe-

© 2008 Thomson Reuters/West. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

2007 WL 4368237 FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Page 15

2007 WL 4368237 (CA (Civ Div)), [2008] 1 All E.R. 1177, [2007] 2 C.L.C. 994, (2008) 152 S.J.L.B. 29, 1-07-2008

Times 4368,237, [2007] EWCA Civ 1374

less if one examines what rights the Government like the comparable provisions of the 1930 Act,

had and that no one else had, what the Government only come into play when the criminal court im-

had amounted to what we would regard as owner- poses penalties following conviction. Paragraph 2

ship" imposes an in personam obligation on

the discoverer to submit discovered items to the

64 Applying this approach to the 1979 Legal Bill, nearest office of Culture and Higher Education.

he submitted that this replaced the provisions of the Paragraph 3 also affects ownership but only in rela-

1930 Act and the 1932 Regulations. The discoverer tion to objects less than 100 years old.

of antiquities no longer had any claim to ownership 55. I accept the evidence of Mr Sabi and the Bill

of them. The most that he could receive was a dis- does not address wider questions of ownership of

coverer's reward. It was impossible for anyone oth- undiscovered antiquities. If that had been the inten-

er than Iran to become the owner of antiquities to tion, it would have been clearly spelt out in the le-

which the Legal Bill applied. gislation."

65 The judge's findings in relation to the 1979 Leg- 66 In considering these findings we propose to start

al Bill, accepting Mr Sabi's evidence and the sub- by considering whether, under the 1979 Legal Bill,

missions made on behalf of Barakat, were as fol- it is possible to identify anyone other than Iran as

lows: the owner of antiquities that are discovered. This is

"53. ... I have been unable to find any provision a question that the judge did not expressly address,

prior to the 1979 Bill which confers ownership of although his concluding observation in the passage

antiquities on the state. To the extent that Professor that we have just quoted suggests that he accepted

Taleghany is asserting that the 1979 Legal Bill does the correctness of Mr Sabi's analysis.

so, I cannot agree with him. As Mr Sabi points out,

the Bill has on its face the limited objective of pre- 67 It was Mr Sabi's evidence that the 1979 Legal

venting the plundering of relics. It is, as Mr Sabi Bill did not affect the application of Article 165 of

says, principally at least, a criminal statute. There is the Civil Code . Ownership of antiquities,

no express vesting of title to antiquities in Iran nor whether illegally excavated or found by accident,

any declaration that all antiquities are vested in the vested in the finder. The illegal excavator was li-

state. I find it difficult to see how the provisions 're- able to have them seized in criminal proceedings,

flect the fact' of state ownership. As Mr Sabi rightly but until that happened he remained the owner. The

says, the draftsman could so easily have provided accidental finder was under an in personam

for state ownership of all antiquities if such had obligation to hand them over to the Office of Cul-

been his intention. It seems to me that, given the ture and Higher Education, but unless and until he

historical background to the Bill's enactment, its did so he remained the owner. We do not think that

purpose was to criminalise the widespread pillaging it was open to the judge to accept this analysis of

of antiquities which was then taking place and not the 1979 Legal Bill.

to make provision for state ownership of antiquit-

ies. 68 It is helpful to start with article 3. The judge re-

54. Under the 1979 Bill ownership is only af- marked, somewhat cryptically, that this "also af-

fected when, by virtue of paragraph 1, seizure in fa- fects ownership but only in relation to objects less

vour of the public treasury takes place upon convic- than 100 years old". It is hard to reconcile the

tion of an offender in a criminal court for undertak- wording of article 3 with the proposition that the

ing unlawful excavation or digging or where, by finder of objects whose antiquity is less than one

virtue of paragraph 4, discovered objects are hundred years old becomes the owner of them be-

offered for sale or purchase. Paragraphs 1 and 4, fore he has paid to the treasury one fifth of their

worth, although the Article does not state who is

© 2008 Thomson Reuters/West. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

2007 WL 4368237 FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Page 16

2007 WL 4368237 (CA (Civ Div)), [2008] 1 All E.R. 1177, [2007] 2 C.L.C. 994, (2008) 152 S.J.L.B. 29, 1-07-2008

Times 4368,237, [2007] EWCA Civ 1374

the owner until this payment is made. "Ownership consists of innumerable rights over

property, for example rights of exclusive enjoy-

69 article 2 deals with the person who accidentally ment, of destruction, alteration and alienation, and

finds antiquities. There is no way in which the Leg- of maintaining and recovering possession of the

al Bill permits him to benefit from his discovery property from all other persons. Those rights are

other than by obtaining the statutory reward. In the conceived not as separately existing, but as merged

first place he is under a positive obligation to hand in one general right of ownership."

them in to the nearest office of Culture and Higher Under the Legal Bill of 1979 the finder of an-

Education 'as soon as possible'. He is not entitled to tiquities enjoys none of these attributes of owner-

offer them for sale. If he purports to sell them, no ship.

title will be transferred to the buyer by reason of

Article 36 of the Civil Code . Furthermore 74 We turn to the position of Iran. Iran is entitled to

he will be guilty of a criminal offence under Article immediate possession of any antiquities found, for

559 of the Punishment Law of 1996. The antiquities the finder is required to hand them over "as soon as

will be subject to seizure. possible". There has been no dispute that once the

antiquities are handed over, they become the prop-

70 Article 1 deals with the position of the erty of Iran. If they are not handed over, but are

person who finds antiquities as a result of illegal transferred by the finder to a third party, the third

excavation. The judge found that he could be in no party will get no title and the antiquities will be

better position than the accidental finder under Art- subject to "seizure".

icle 2 and this finding has not been challenged. Fur-

thermore he will have been guilty of a criminal of- 75 Where the antiquities are discovered in the

fence by virtue of the excavation itself. course of illegal excavation, they will be subject to

"seizure" by Iran, whether they remain in the pos-

71 Having regard to the obligations and restrictions session of the finder or are transferred to a third

that are placed upon the finder of antiquities we do party. It follows that, apart from the right of the ac-