Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jips 17 48

Jips 17 48

Uploaded by

Shahrukh ali khanCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5835)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (350)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (824)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (405)

- Transmigrating Into The Heartthrob's Cannon Fodder - This Concubine Is in ShanyangDocument667 pagesTransmigrating Into The Heartthrob's Cannon Fodder - This Concubine Is in ShanyangLia KaNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Equine Internal Medicine 4th EdDocument1,564 pagesEquine Internal Medicine 4th EdJacky Sieras100% (1)

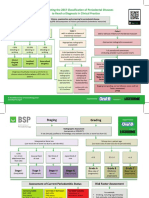

- BSP FlowchartDocument2 pagesBSP FlowchartShahrukh ali khan100% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Evaluationand Comparisonofthe Effectof Different Border Molding Materialson 0 AComplete Denture Retention Aniinvivoi StudyDocument7 pagesEvaluationand Comparisonofthe Effectof Different Border Molding Materialson 0 AComplete Denture Retention Aniinvivoi StudyShahrukh ali khanNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Complete Denture Fabricated by Two Different Border Molding Materials, in Terms of Patients' SatisfactionDocument4 pagesComparison of Complete Denture Fabricated by Two Different Border Molding Materials, in Terms of Patients' SatisfactionShahrukh ali khanNo ratings yet

- Complete Denture IntroductionDocument3 pagesComplete Denture IntroductionShahrukh ali khanNo ratings yet

- Staging and GradingDocument4 pagesStaging and GradingShahrukh ali khanNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Treatment Planning Part 1Document12 pagesDiagnosis and Treatment Planning Part 1Shahrukh ali khanNo ratings yet

- Effects of Ageing On Edentulous Mouth: BoneDocument6 pagesEffects of Ageing On Edentulous Mouth: BoneShahrukh ali khanNo ratings yet

- Dental Bleaching: Presenter: DR Shahrukh Ali Khan Resident R1 Prosthodontics Aga Khan University, HospitalDocument47 pagesDental Bleaching: Presenter: DR Shahrukh Ali Khan Resident R1 Prosthodontics Aga Khan University, HospitalShahrukh ali khanNo ratings yet

- Research ArticleDocument7 pagesResearch ArticleShahrukh ali khanNo ratings yet

- Clinics in SurgeryDocument5 pagesClinics in SurgeryShahrukh ali khanNo ratings yet

- Common Mistakes in Clinical ResearchDocument6 pagesCommon Mistakes in Clinical ResearchShahrukh ali khanNo ratings yet

- FDS Amp 2020Document140 pagesFDS Amp 2020Shahrukh ali khan100% (1)

- Evaluation of Signs, Symptoms, and Occlusal Factors Among Patients With Temporomandibular Disorders According To Helkimo IndexDocument8 pagesEvaluation of Signs, Symptoms, and Occlusal Factors Among Patients With Temporomandibular Disorders According To Helkimo IndexShahrukh ali khanNo ratings yet

- Bloodborne Pathogens Learner Course Guide: Florida Department of HealthDocument30 pagesBloodborne Pathogens Learner Course Guide: Florida Department of HealthShahrukh ali khanNo ratings yet

- Infection Control in DentistryDocument69 pagesInfection Control in DentistryShahrukh ali khanNo ratings yet

- Necrosis and Types of NecrosisDocument2 pagesNecrosis and Types of NecrosisHisham NesemNo ratings yet

- Hieronymus Revised Rate BookDocument323 pagesHieronymus Revised Rate BookPetrut Valentin100% (2)

- Immunity EPIDocument37 pagesImmunity EPIluttomiayvonneNo ratings yet

- Criterios de Clsificacion de Espondilitis AnquilosanteDocument16 pagesCriterios de Clsificacion de Espondilitis AnquilosanteWilkerson PerezNo ratings yet

- VATA DOSHA Edit PDFDocument3 pagesVATA DOSHA Edit PDFAashray KothaNo ratings yet

- Hagan and Brunerx27s Infectious Diseases of DomestDocument2 pagesHagan and Brunerx27s Infectious Diseases of DomestNopparach ManadeeNo ratings yet

- Multiple Disability Original HandoutDocument42 pagesMultiple Disability Original HandoutHabtamu DebasuNo ratings yet

- The Onset of Acute Type A Aortic Dissection Following Recovery of Type B Intramural Haematoma-A Case ReportDocument4 pagesThe Onset of Acute Type A Aortic Dissection Following Recovery of Type B Intramural Haematoma-A Case ReportNguyễn Thời Hải NguyênNo ratings yet

- Preoperative Preparation and Postoperative CareDocument103 pagesPreoperative Preparation and Postoperative Carechowhan04No ratings yet

- Dwnload Full Research Methods For Social Work 8th Edition Rubin Test Bank PDFDocument35 pagesDwnload Full Research Methods For Social Work 8th Edition Rubin Test Bank PDFmatte.caudalebvf100% (12)

- RDS DR Idham-Dr RismaDocument38 pagesRDS DR Idham-Dr RismaReynaldo Rahima PutraNo ratings yet

- Drug Study-Nifedipine-BALLON, Karlo C.Document2 pagesDrug Study-Nifedipine-BALLON, Karlo C.Melinda Cariño Ballon100% (1)

- Sabino Rebagay Memorial High SchoolDocument6 pagesSabino Rebagay Memorial High SchoolRina RomanoNo ratings yet

- 2010 Nurse Protocol ManualDocument749 pages2010 Nurse Protocol Manualjeenath justin doss100% (2)

- Malignant Pleural Effusion1Document56 pagesMalignant Pleural Effusion1getnusNo ratings yet

- Dr. Jay Davidson: Let'S "Talk" WithDocument32 pagesDr. Jay Davidson: Let'S "Talk" WithDorian GrayNo ratings yet

- THEORIES of CRIME CAUSATION NOTESDocument12 pagesTHEORIES of CRIME CAUSATION NOTESLombroso's follower100% (1)

- HEALTH TALK of EncopresisDocument15 pagesHEALTH TALK of EncopresisAmit RanjanNo ratings yet

- Hospital Waste ManagementDocument40 pagesHospital Waste Managementamir khanNo ratings yet

- Pharma Module 4Document4 pagesPharma Module 4Chelsy Sky SacanNo ratings yet

- EuphorbiaceaeDocument14 pagesEuphorbiaceaeHaritha V HNo ratings yet

- Jeyakumar Dhileeban Rrroll 41Document34 pagesJeyakumar Dhileeban Rrroll 41Rupesh TamizhaNo ratings yet

- Eva Bolton Haematuria Presentation WebDocument52 pagesEva Bolton Haematuria Presentation WebereczkieNo ratings yet

- LV Systolic FunctionDocument36 pagesLV Systolic Functionsruthimeena6891No ratings yet

- Healing With Light and Color GuideDocument31 pagesHealing With Light and Color GuidemariyastojNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan: Pre-Reading BeginnerDocument15 pagesLesson Plan: Pre-Reading BeginnerMazidah Ida IsmailNo ratings yet

- Shaw 2004Document7 pagesShaw 2004Mouloudi NajouaNo ratings yet

- MedicalCheckUp - Physical Examination PDFDocument3 pagesMedicalCheckUp - Physical Examination PDFCielo Baez ArceNo ratings yet

Jips 17 48

Jips 17 48

Uploaded by

Shahrukh ali khanOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Jips 17 48

Jips 17 48

Uploaded by

Shahrukh ali khanCopyright:

Available Formats

Original Article

Analysis of Helkimo index for temporomandibular

disorder diagnosis in the dental students of Faridabad city:

A cross‑sectional study

Sapna Rani, Salil Pawah, Sunil Gola, Mansha Bakshi

Department of Prosthodontics, Sudha Rustagi College of Dental Sciences and Research, Faridabad, Haryana, India

Abstract Aim and Objectives: The aim of the study was to evaluate the prevalence of temporomandibular

disorder (TMD) by the use of Helkimo’s index (anamnestic [Ai] and clinical dysfunction [Di] component) in

the nonpatient population (dental students) of Faridabad college.

Settings and Design: A questionnaire‑based survey was carried out among students of dental college for

signs and symptoms of TMD and also clinical examination was done. The results were scored and according

to scoring severity of TMD were assessed in the specified population.

Materials and Methods: About 580 students were assessed for TMD by the use of Helkimo’s index

(Ai and Di component). Descriptive statistical analysis was done.

Results: Among the study group, 15% were found to have TMDs. Out of the affected students, 79% females

and 21% males were having symptoms. Out of the signs and symptoms present, 7% students were found to

have sound in temporomandibular joint followed by pain in 3% and fatigue in 2% of students. On clinical

examination, limited mouth opening was found in 6% students followed by locked mandible in 1%, deviation

of jaw in 0.6%, and jaw rigidity of mandible in 0.6% of individual.

Conclusion: To summarize, Helkimo index is a well‑founded index to assess TMD in a specified population.

Signs and symptoms of TMD were present among students although low prevalence of TMD was found

in the students.

Key Words: Helkimo index, temporomandibular disorder, temporomandibular joint

Address for correspondence:

Dr. Sapna Rani, House No. 2062, Sector 7D, Faridabad ‑ 121 006, Haryana, India. E‑mail: drsapnadaksh@gmail.com

Received: 02nd May, 2016, Accepted: 13th July, 2016

INTRODUCTION temporomandibular joint (TMJ), masticatory muscles, and

occlusion, with common symptoms such as pain, restricted

Temporomandibular disorder (TMD) is a wide‑ranging term movement, muscle tenderness, and intermittent joint sounds.[1]

used to describe a number of related disorders involving the

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution‑NonCommercial‑ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and

Access this article online

build upon the work non‑commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations

Quick Response Code: are licensed under the identical terms.

Website:

www.j‑ips.org For reprints contact: reprints@medknow.com

How to cite this article: Rani S, Pawah S, Gola S, Bakshi M. Analysis

DOI: of Helkimo index for temporomandibular disorder diagnosis in the dental

10.4103/0972-4052.194941 students of Faridabad city: A cross-sectional study. J Indian Prosthodont

Soc 2017;17:48-52.

48 © 2016 The Journal of Indian Prosthodontic Society | Published by Wolters Kluwer ‑ Medknow

Rani, et al.: Prevalence of temporomandibular disorder

TMDs can also be defined as a collective term for conditions As there is an increase in awareness toward oral health, there is

that involve pain and/or dysfunction of the TMJ and the an increase in demand for TMD. It is therefore important and

related structures.[2,3] valuable to have epidemiological data to estimate the proportion

and distribution of these disorders in the population. Due

The most frequent symptoms of TMD are sound in the area to variability of the complaints, TMD is diagnosed mainly

of the TMJ,[4] a sensation of fatigue in the jaw area, a sensation by signs and symptoms. People should know initial signs

of stiffness of the jaw upon waking up or when opening the and symptoms of TMD that may worsen with time even in

mouth, luxation or locking of the mandible when opening the nonpatient population (dental students).

mouth, pain when opening the mouth, and pain in the region

of the TMJ or in the area of the masticatory muscles. The The rationale of this study was to pay deeper attention to

most frequent signs of TMD include restricted mandibular TMD, especially in students as the stress level is high in the

movement, lower TMJ function, painful mandibular movement, students and stress is a contributing factor in TMD, and also it

muscle pain, and pain in the TMJ.[5] is found in the literature, a high prevalence of TMD in dental

students.[10] The present investigation aims at cross‑sectional

Etiology of TMD has been a conflicting topic for discussion. epidemiological study for TMD signs and symptoms in

Earlier it was suggested that occlusal discrepancies are the dental students of Faridabad through clinical examination and

major culprit for TMD patients, but later on, in the 1960s self‑reported questionnaire.

and 1970s, emotional stress and occlusal discrepancy were

considered as etiology. Further with an increase in research work MATERIALS AND METHODS

in TMD patients, it was found that the etiology may include

Study design

psychosocial, psychological, and physical factors. Dahlström

This descriptive cross‑sectional study was conducted at dental

and Carlsson conducted a systematic review on TMDs, and oral

college of Faridabad. A total number of 580 students with

health‑related quality of life (OHRQoL) and they observed a

the age group of 17–28 years were randomly selected for the

high impact on OHRQoL in TMD patients.[6]

study. Data were collected from February 2016 to April 2016.

TMD is a multifactorial complex disorder and the etiology is Participants were given no time limit to fill questionnaire (in

related to emotional tension, teeth loss, occlusal interferences, days) so as to reduce induced error. Clinical examination was

masticatory muscular dysfunction, postural deviation, internal done only by one expert investigator to minimize error. Ethical

and external changes in TMJ structure, and the various Committee clearance was obtained from the Institutional

associations of these factors.[7] Sound in TMJ area (clicking Review Board.

or crepitus) is most frequent sign in TMD patients. Clicks are Inclusion and exclusion criteria

brief sound in TMJ area associated with disc displacement with Students with all permanent dentition and no history

reduction; though click‑like sounds can also be produced by of orthodontic treatment were included in the study.

joint remodeling and hypermobility. The absence of click does The patients diagnosed as having stomatognathic system

not necessarily imply healthy TMJ. Therapy is indicated when impairment, clinically diagnosed TMD with treatment and

clicking is associated with pain and deviation of mandible. students with any gross pathology of ear were excluded from

Deviation is caused by disc displacement with reduction.[1] the study. Initially, proper instructions were given to the

Deflection of mandible is caused in case of disc displacement participants about the goals and benefits of the study and

without reduction where the translation of mandible is affected. informed consent was signed. Then, the participants were

Nerve endings are found in disc and capsular ligaments and asked to answer the questionnaire, to evaluate the TMD in

retrodiscal tissue. When condyle articulates with retrodiscal undiagnosed cases.

tissue, entrapment of retrodiscal tissue is considered as stimulus

for pain in TMJ.[8] Sample size estimation

The sample size was decided on the basis of the results of

As there are no criteria to attain a numeric value to decide the the other previous studies in which the prevalence was found

severity of TMD, indices play an important role to determine to be 42%.

the prevalence of this disorder in a specified population.

Helkimo was considered as a pioneer in developing index to Sample size = (Z2× [p] × [1 − p])/C2.

measure the severity and pain in TMD patients. Helkimo’s

index was further broken down into anamnesis, clinical, and Where Z = Z value for the confidence level chosen

occlusal dysfunction.[9] (e.g., 1.96 for 95% confidence level).

The Journal of Indian Prosthodontic Society | Jan-Mar 2017 | Vol 17 | Issue 1 49

Rani, et al.: Prevalence of temporomandibular disorder

p = Percentage having a particular disease/problem etc., and Table 1: Questionnaire for anamnestic component

it is expressed as a percentage (generally it is taken as 0.5). Name: _______

Age: _______

Gender: _______

C = Confidence interval (CI) expressed, expressed as a 1 Do you have a sound (clicking or crepitation) in the area Yes No

decimal (generally 0.05). of TMJ?

2 Do you have jaw rigidity during awakening or slow Yes No

movement of mandible?

The minimum sample size required for the study was found 3 Do you feel fatigue in the jaw area? Yes No

to be 374 to obtain CI level of 0.95, at least 80% power for 4 Do you have difficulty while opening mouth? Yes No

analysis and minimal error. Sample size was kept to be 580 as 5 Do you have locked mandible during opening the mouth? Yes No

6 Do you have pain in the TMJ in the area of masticatory Yes No

the students volunteered for the research. muscles?

7 Do you have pain during movement of mandible? Yes No

Questionnaire 8 Do you have luxation of mandible? Yes No

Registration of subjective symptoms applying for the Helkimo TMJ: Temporomandibular joint

Index required a questionnaire‑based survey. Questionnaire

comprised two parts: Anamnestic component which includes Table 2: Clinical dysfunction component

answers to questions in “yes” or “no” [Table 1]. Clinical Mandibular opening

>40 mm

dysfunction part comprised clinical examination such as 30-39 mm

extraoral examination, palpation, and observation of palpebral >30 mm

reflex in all the students [Table 2]. Mandibular deviation during lowering

<2 mm

2-5 mm

Data collection and analysis >5 mm

The data were collected and analyzed for demographic variables TMJ dysfunction

such as gender has been mentioned. Questionnaire was received, No impairment

Palpable clicking

and it was analyzed according to anamnestic scale as follows: Evident clicking

• 0: No symptoms TMJ pain

No pain

• I: Mild symptoms included sensation of the jaw fatigue, Palpable pain

jaw stiffness, and TMJ sounds (clicking or crepitus) Palpebral reflex

• II: Severe symptoms included one or more of the Muscle pain

No pain

following: (a) Difficulty in the mouth opening, (b) jaw Palpable pain

locking, (c) mandible dislocation and its painful movement, Palpebral reflex

and (d) painful TMJ region and/or masticatory muscles.[11] TMJ: Temporomandibular joint

To accomplish the examination of the clinical dysfunction, d. TMJ pain: TMJ was palpated for the presence of pain in

a modified version of Helkimo’s dysfunction index (Di) was TMJ, score 0 – no pain, score 1 – palpable pain, and score

calculated. Clinical examination included opening of mandible, 5 – palpebral reflex

deviation during opening, dysfunction of TMJ, pain in the TMJ e. Muscle pain: Bilateral examination was carried out

and preauricular region, and also masticatory muscles were for muscles of mastication, score 0 – no pain, score

palpated for pain. The clinical assessment was done as follows: 1 – palpable pain, and score 5 – palpebral reflex.

a. Opening range: Opening range was determined by asking

the patient to gently open mouth and with the help of Scores assigned for the five symptoms was summed up.

ruler measure the distance between upper and lower central Each individual had a total dysfunction score ranging from

incisor, score 0 – if >40 mm, score 1 – if 30–39 mm, 0 to 25 points. Higher the score, the more acute/serious

and score 5 – if <30 mm the disorder. Depending on the values obtained, the patients

b. Mandibular deviation during lowering: Patient was asked were classified as follows: Di0 – no dysfunction; DiI – mild

to open mouth gently and deviation is noted between dysfunction (1–4 points); DiII – moderate dysfunction

maxillary and mandibular midline, score 0 – if <2 mm, (5–9 points); DiIII – severe dysfunction (9–25 points).

score 1 – if 2–5 mm, and score 5 – if >5 mm

c. TMJ dysfunction: TMJ was examined for clicking, Statistical analysis

locking, and luxation without using stethoscope, score The Cronbach’s alpha was calculated using the SPSS software

0 – no impairment, score 1 – palpable clicking, and score for the validation of the questionnaire. The Cronbach’s alpha

5 – evident clicking, locking, and luxation value was found to be 0.80 which was satisfactory.

50 The Journal of Indian Prosthodontic Society | Jan-Mar 2017 | Vol 17 | Issue 1

Rani, et al.: Prevalence of temporomandibular disorder

RESULTS the questionnaire (89%) was satisfactory as compared to other

studies.[12] Among the study group, only 15% were found to

Out of 650 questionnaires distributed, 580 students responded have signs and symptoms of TMD, whereas 85% students were

to the questionnaire. Among 580 students, 468 (81%) were without any sign or symptom which was in accordance with

females and 112 (19%) were males [Graph 1]. the study done by Mutlu et al.[12] but less than the prevalence

found by Modi et al.[l3] who showed a prevalence rate of 68.6%.

Among the study group, 84 students (15%) were found to have

signs and symptoms, i.e., pain, sound in the TMJ, deviation, and Females were preceeded by males in presenting the TMDs as

limited mouth opening. Four hundred and ninety‑six students shown in previous studies[14] but judgment could not be made

were symptom‑free or without any symptoms that account for about females at an edge over males because of a unequal

85% [Graph 2]. number of males and females included in the study. There is a

Sixty‑six females were affected among symptomatic patients Table 3: Number and sex distribution

who account for 14% of the female population, whereas only Males Percentage Females Percentage

18 (16%) males were having symptoms [Table 3]. With signs and symptoms 18 16 66 14

Without signs and 94 84 402 86

symptoms

Out of the signs and symptoms present, sound in the TMJ Total 112 468

was most common problem (40 students) which accounts

for 7% followed by pain in 20 students (3%) and fatigue in Table 4: Prevalence of signs and symptoms among students

12 students (2%) in TMJ. Components n=580 Percentage

Anamnestic component

On clinical examination, limited mouth opening was found Sound in TMJ 40 7

in 34 students which accounts for 6% followed by locked Pain in TMJ 20 3

Fatigue in TMJ 12 2

mandible (6 students) 1%, deviation (4 students) 1%, and

Clinical dysfunction

jaw rigidity of mandible (4 students) 1% during mouth Limited mouth 34 6

opening [Table 4]. opening

Locked mandible 06 1

Deviation 04 0.6

According to anamnestic component of Helkimo’s index, Jaw rigidity 04 0.6

90% students were free from symptoms, 7% students were TMJ: Temporomandibular joint

found to have mild symptoms, and 3% students were having

severe symptoms. According to dysfunction component, 94% Table 5: Evaluation of Helkimo index components among

students were found to have no dysfunction, 5.7% students students

were having mild dysfunction, and only 0.3% students were Test group

Component n=580 Percentage

having moderate dysfunction, whereas not a single student was

Anamnesis index

having severe dysfunction [Table 5]. Ai0 (free of symptoms) 520 90

AiI (mild symptoms) 40 7

DISCUSSION AiII (severe symptoms) 20 3

Dysfunction component

The present study was conducted to assess the prevalence of Di0 (no dysfunction) 546 94

DiI (mild dysfunction) 32 5.7

TMD in the dental students of Faridabad by the use of a DiII (moderate dysfunction) 2 0.3

self‑reported questionnaire‑based survey. The response rate of DiIII (severe dysfunction) 0 0

Graph 1: Distribution of patients according to gender Graph 2: Prevalence of temporomandibular disorders

The Journal of Indian Prosthodontic Society | Jan-Mar 2017 | Vol 17 | Issue 1 51

Rani, et al.: Prevalence of temporomandibular disorder

discrepancy in the number of males and females participated TMJ area was ranked higher. Further studies are required at

in the study as the number of female students was more in the community level to compare TMD with different age groups

college and more female students volunteered for the study. and different population.

If equal number of male and female population would have

been selected, sample would not be representative of actual Acknowledgment

study population. I want to thank Dr. Sukhvinder Singh for his help in statistical

analysis and students of college and faculty members, for their

It is believed that there is a large psychosocial component of contribution in the study.

this disease. Increased stress levels are believed to result in

poor habits including bruxism, clenching, and even excessive Financial support and sponsorship

gum chewing. These lead to muscular overuse, fatigue and Nil.

spasm, and subsequently pain.[4] Many symptoms may not have

Conflicts of interest

manifestations related to TMJ itself, for example, headache,

There are no conflicts of interest.

earache, sounds, etc., In the present study, TMJ sound (clicking

or crepitus) (7%) was the most common problem which was REFERENCES

in accordance with the study done by Gopal et al.[7] Although

the methods and criteria for recording joint sounds differ in 1. Okeson JP, editor. Etiology of functional disturbances in the masticatory

the various reports apart from natural fluctuations, they are system. In: Management of Temporomandibular Disorders and Occlusion.

7th ed. Rio de Janeiro: Elsevier; 2013.

the possible reasons for the wide range of joint sounds. Sound 2. De Leeuw R, Klasser G, editors. Orofacial Pain: Guidelines for Assessment,

in TMJ was followed by pain (3%) and fatigue in TMJ (2%). Diagnosis, and Management. 5th ed. Chicago: Quintessence Publishing

This notion was in accordance with analysis done by Hegde.[4] Co., Inc.; 2013.

3. Young AL. Internal derangements of the temporomandibular joint: A review

of the anatomy, diagnosis, and management. J Indian Prosthodont Soc

Clinical examination reveals limited mouth opening in most 2015;15:2‑7.

affected students (6%) followed by locking of mandible (1%), 4. Hegde V. A review of the disorders of temperomandibular joint. J Indian

jaw deviation (0.6%), and rigidity (0.6%) of TMJ. Limited Prosthodont Soc 2005;5:56‑61.

5. Helkimo M. Studies on function and dysfunction of the masticatory system.

mouth opening was found in some patients without any II. Index for anamnestic and clinical dysfunction and occlusal state. Sven

symptom of TMD, which was physiologically normal. Students Tandlak Tidskr 1974;67:101‑21.

with TMDs were further treated for the cause. The large 6. Dahlström L, Carlsson GE. Temporomandibular disorders and oral

frequency ranges for signs and symptoms of TMD previously health‑related quality of life. A systematic review. Acta Odontol Scand

2010;68:80‑5.

described in reviews and meta‑analysis are apparently based on 7. Gopal KS, Shankar R, Vardhan HB. Prevalence of temporo‑mandibular

very different samples (e.g., random vs. nonrandom, patient vs. joint disorders in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients: A cross‑sectional

nonpatient, different ages, age ranges, sample size, and ratio study. Int J Adv Sci 2014;1:14‑20.

of gender distribution) and different samples (e.g., kind of 8. Gallo LM, Airoldi R, Ernst B, Palla S. Power spectral analysis of

temporomandibular joint sounds in asymptomatic subjects. J Dent Res

variable, method of data collection). 1993;72:871‑5.

9. Lima DR, Brunetti RF, Oliveira W. Study of the prevalence of

In the presented study, prevalence of TMDs in students was craniomandibular dysfunction using Helkimo’s index and having as

found to be low as compared to other studies.[13] Different variables sex, age and whether the subjects had or had not been treated

orthodonticaly. Pós Grad Rev Fac Odontol São José Dos Campos

reports on the prevalence of TMDs are due to lack of 1999;2:127‑33.

standardization, different indices used for examination, etc., 10. Hegde S, Mahadev R, Ganapathy KS, Patil AB. Prevalence of signs and

The prevalence of TMD is not still well known and more symptoms of temporomandibular disorders in dental students. J Indian

Acad Oral Med Radiol 2011;23:316‑9.

studies, and comparisons are necessary to allow a better 11. da Cunha SC, Nogueira RV, Duarte AP, Vasconcelos BC, Almeida Rde A.

understanding of the pathological aspects so as to address Analysis of helkimo and craniomandibular indexes for temporomandibular

effective and therapeutic measures. Longitudinal studies are disorder diagnosis on rheumatoid arthritis patients. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol

needed to see the prevalence in the study population and to 2007;73:19‑26.

12. Mutlu N, Herken H, Guray E, Oz F, Kalayaci A. Evaluation of the prevalence

meet the health‑care need of students. of temporomandibular joint disorder syndrome in dental school students

with psychometric analysis. Turk J Med Sci 2002;32:345‑50.

CONCLUSION 13. Modi P, Shaikh SS, Munde A. A cross sectional study of prevalence of

temporomandibular disorders in university students. Int J Sci Res Publ

Results from the aforementioned study analyzed that clinical 2012;2:1‑3.

14. Casanova‑Rosado JF, Medina‑Solís CE, Vallejos‑Sánchez AA,

signs and symptoms were present even in the nonpatient

Casanova‑Rosado AJ, Hernández‑Prado B, Avila‑Burgos L. Prevalence and

population. Most of the cardinal signs were seen in varying associated factors for temporomandibular disorders in a group of Mexican

extent in the study population out of which sound in the adolescents and youth adults. Clin Oral Investig 2006;10:42‑9.

52 The Journal of Indian Prosthodontic Society | Jan-Mar 2017 | Vol 17 | Issue 1

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5835)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (350)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (824)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (405)

- Transmigrating Into The Heartthrob's Cannon Fodder - This Concubine Is in ShanyangDocument667 pagesTransmigrating Into The Heartthrob's Cannon Fodder - This Concubine Is in ShanyangLia KaNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Equine Internal Medicine 4th EdDocument1,564 pagesEquine Internal Medicine 4th EdJacky Sieras100% (1)

- BSP FlowchartDocument2 pagesBSP FlowchartShahrukh ali khan100% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Evaluationand Comparisonofthe Effectof Different Border Molding Materialson 0 AComplete Denture Retention Aniinvivoi StudyDocument7 pagesEvaluationand Comparisonofthe Effectof Different Border Molding Materialson 0 AComplete Denture Retention Aniinvivoi StudyShahrukh ali khanNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Complete Denture Fabricated by Two Different Border Molding Materials, in Terms of Patients' SatisfactionDocument4 pagesComparison of Complete Denture Fabricated by Two Different Border Molding Materials, in Terms of Patients' SatisfactionShahrukh ali khanNo ratings yet

- Complete Denture IntroductionDocument3 pagesComplete Denture IntroductionShahrukh ali khanNo ratings yet

- Staging and GradingDocument4 pagesStaging and GradingShahrukh ali khanNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Treatment Planning Part 1Document12 pagesDiagnosis and Treatment Planning Part 1Shahrukh ali khanNo ratings yet

- Effects of Ageing On Edentulous Mouth: BoneDocument6 pagesEffects of Ageing On Edentulous Mouth: BoneShahrukh ali khanNo ratings yet

- Dental Bleaching: Presenter: DR Shahrukh Ali Khan Resident R1 Prosthodontics Aga Khan University, HospitalDocument47 pagesDental Bleaching: Presenter: DR Shahrukh Ali Khan Resident R1 Prosthodontics Aga Khan University, HospitalShahrukh ali khanNo ratings yet

- Research ArticleDocument7 pagesResearch ArticleShahrukh ali khanNo ratings yet

- Clinics in SurgeryDocument5 pagesClinics in SurgeryShahrukh ali khanNo ratings yet

- Common Mistakes in Clinical ResearchDocument6 pagesCommon Mistakes in Clinical ResearchShahrukh ali khanNo ratings yet

- FDS Amp 2020Document140 pagesFDS Amp 2020Shahrukh ali khan100% (1)

- Evaluation of Signs, Symptoms, and Occlusal Factors Among Patients With Temporomandibular Disorders According To Helkimo IndexDocument8 pagesEvaluation of Signs, Symptoms, and Occlusal Factors Among Patients With Temporomandibular Disorders According To Helkimo IndexShahrukh ali khanNo ratings yet

- Bloodborne Pathogens Learner Course Guide: Florida Department of HealthDocument30 pagesBloodborne Pathogens Learner Course Guide: Florida Department of HealthShahrukh ali khanNo ratings yet

- Infection Control in DentistryDocument69 pagesInfection Control in DentistryShahrukh ali khanNo ratings yet

- Necrosis and Types of NecrosisDocument2 pagesNecrosis and Types of NecrosisHisham NesemNo ratings yet

- Hieronymus Revised Rate BookDocument323 pagesHieronymus Revised Rate BookPetrut Valentin100% (2)

- Immunity EPIDocument37 pagesImmunity EPIluttomiayvonneNo ratings yet

- Criterios de Clsificacion de Espondilitis AnquilosanteDocument16 pagesCriterios de Clsificacion de Espondilitis AnquilosanteWilkerson PerezNo ratings yet

- VATA DOSHA Edit PDFDocument3 pagesVATA DOSHA Edit PDFAashray KothaNo ratings yet

- Hagan and Brunerx27s Infectious Diseases of DomestDocument2 pagesHagan and Brunerx27s Infectious Diseases of DomestNopparach ManadeeNo ratings yet

- Multiple Disability Original HandoutDocument42 pagesMultiple Disability Original HandoutHabtamu DebasuNo ratings yet

- The Onset of Acute Type A Aortic Dissection Following Recovery of Type B Intramural Haematoma-A Case ReportDocument4 pagesThe Onset of Acute Type A Aortic Dissection Following Recovery of Type B Intramural Haematoma-A Case ReportNguyễn Thời Hải NguyênNo ratings yet

- Preoperative Preparation and Postoperative CareDocument103 pagesPreoperative Preparation and Postoperative Carechowhan04No ratings yet

- Dwnload Full Research Methods For Social Work 8th Edition Rubin Test Bank PDFDocument35 pagesDwnload Full Research Methods For Social Work 8th Edition Rubin Test Bank PDFmatte.caudalebvf100% (12)

- RDS DR Idham-Dr RismaDocument38 pagesRDS DR Idham-Dr RismaReynaldo Rahima PutraNo ratings yet

- Drug Study-Nifedipine-BALLON, Karlo C.Document2 pagesDrug Study-Nifedipine-BALLON, Karlo C.Melinda Cariño Ballon100% (1)

- Sabino Rebagay Memorial High SchoolDocument6 pagesSabino Rebagay Memorial High SchoolRina RomanoNo ratings yet

- 2010 Nurse Protocol ManualDocument749 pages2010 Nurse Protocol Manualjeenath justin doss100% (2)

- Malignant Pleural Effusion1Document56 pagesMalignant Pleural Effusion1getnusNo ratings yet

- Dr. Jay Davidson: Let'S "Talk" WithDocument32 pagesDr. Jay Davidson: Let'S "Talk" WithDorian GrayNo ratings yet

- THEORIES of CRIME CAUSATION NOTESDocument12 pagesTHEORIES of CRIME CAUSATION NOTESLombroso's follower100% (1)

- HEALTH TALK of EncopresisDocument15 pagesHEALTH TALK of EncopresisAmit RanjanNo ratings yet

- Hospital Waste ManagementDocument40 pagesHospital Waste Managementamir khanNo ratings yet

- Pharma Module 4Document4 pagesPharma Module 4Chelsy Sky SacanNo ratings yet

- EuphorbiaceaeDocument14 pagesEuphorbiaceaeHaritha V HNo ratings yet

- Jeyakumar Dhileeban Rrroll 41Document34 pagesJeyakumar Dhileeban Rrroll 41Rupesh TamizhaNo ratings yet

- Eva Bolton Haematuria Presentation WebDocument52 pagesEva Bolton Haematuria Presentation WebereczkieNo ratings yet

- LV Systolic FunctionDocument36 pagesLV Systolic Functionsruthimeena6891No ratings yet

- Healing With Light and Color GuideDocument31 pagesHealing With Light and Color GuidemariyastojNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan: Pre-Reading BeginnerDocument15 pagesLesson Plan: Pre-Reading BeginnerMazidah Ida IsmailNo ratings yet

- Shaw 2004Document7 pagesShaw 2004Mouloudi NajouaNo ratings yet

- MedicalCheckUp - Physical Examination PDFDocument3 pagesMedicalCheckUp - Physical Examination PDFCielo Baez ArceNo ratings yet