Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Plaintiff's Trial Brief: Estate of Bernice Kekona v. Alaska Airlines, Inc.

Plaintiff's Trial Brief: Estate of Bernice Kekona v. Alaska Airlines, Inc.

Uploaded by

KGW NewsCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Plaintiff's Trial Brief: Estate of Bernice Kekona v. Alaska Airlines, Inc.

Plaintiff's Trial Brief: Estate of Bernice Kekona v. Alaska Airlines, Inc.

Uploaded by

KGW NewsCopyright:

Available Formats

1 The Honorable Suzanne Parisien

Trial Date: February 8, 2021

2

7

IN THE SUPERIOR COURT OF WASHINGTON FOR KING COUNTY

8

9

Estate of BERNICE KEKONA by and NO. 17-2-33240-2 SEA

10 through its Personal Representative, Darlene

Bloyed, PLAINTIFF’S TRIAL BRIEF

11

Plaintiff,

12

v.

13 ALASKA AIRLINES, INC., an Alaska

Corporation,

14

Defendant.

15

16

Plaintiff, by and through her counsel of record, hereby submits her trial brief as requested

17

by the Court in its Case Scheduling Order.

18

Section III below addresses several rulings previously made by Judge Jim Rogers and

19

their impact on the evidence and legal issues at trial.

20

In addition, and further referenced herein, other legal memoranda filed by plaintiff inform

outstanding legal and evidentiary issues in this case, including: Memorandum of Plaintiff Re

21

Burden of Proof (Dkt. 154); Plaintiff’s Memorandum Regarding Huntleigh’s 30(B)(6) Designee,

22

Gary Wolf, Deposition Testimony (Dkt. 171); Plaintiff’s Memorandum Regarding Inapplicability

23

LUVERA LAW FIRM

24 PLAINTIFF’S TRIAL BRIEF - 1 ATTORNEYS AT LAW

6700 COLUMBIA CENTER • 701 FIFTH AVENUE

SEATTLE, WASHINGTON 98104

(206) 467-6090

1 of 14 C.F.R. § 382.29 Relating to Safety Assistants) (Dkt. 172); Plaintiff’s Memorandum Re

2 Relevance of Cognitive Issues (Dkt. 178); and Plaintiff’s Renewed Motion for Order Excluding

3 Evidence of or Reference to Alleged Fault of Family Members, filed 2/3/21.

4 I. INTRODUCTION

5 Darlene Bloyed – acting in her capacity as the personal representative of the Estate of

6 Bernice Kekona – brings this negligence lawsuit against Alaska Airlines, Inc. seeking damages for

7 personal injury and loss of consortium for statutory beneficiaries. The Estate of Bernice Kekona

8 is the plaintiff because Mrs. Kekona died from the injuries suffered from the incident which is the

9 subject of this case.

10 Alaska was required by the Air Carrier Access Act to provide gate-to-gate escort services

11 to Mrs. Kekona, a vulnerable, disabled traveler. Gate-to-gate escort services had been requested

12 by Mrs. Kekona and her family multiple times as documented in Alaska’s computer system.

13 However, Alaska completely failed to communicate those requests to its service provider,

14 Huntleigh USA Corporation; therefore, the services were not offered or provided to Mrs. Kekona

15 upon her arrival in Portland on June 7, 2017. Alaska abandoned Mrs. Kekona inside the Portland

16 International Airport where she attempted to navigate the airport alone in her electric wheelchair.

17 In doing so, Mrs. Kekona took a horrific fall down an escalator, sustaining injuries that eventually

18 led to her death on September 20, 2017.

19 At trial, Ms. Bloyed will present ample evidence for the jury to conclude Alaska was

20 negligent and that such negligence was the proximate cause of Mrs. Kekona’s significant injuries

and eventual death. The Huntleigh employees tasked with providing gate-to-gate escort services

21 at the Portland airport for Alaska were not given the information gathered by Alaska that Mrs.

22 Kekona needed and requested gate-to-gate escort services. That failure to communicate is a breach

23 of the duty owed to Mrs. Kekona.

LUVERA LAW FIRM

24 PLAINTIFF’S TRIAL BRIEF - 2 ATTORNEYS AT LAW

6700 COLUMBIA CENTER • 701 FIFTH AVENUE

SEATTLE, WASHINGTON 98104

(206) 467-6090

1 Following that failure, Huntleigh did not provide the requested gate-to-gate escort service

2 to Mrs. Kekona, but rather directed her to the baggage claim area believing she had completed her

3 travel. That failure to provide the requested gate-to-gate escort service is an additional breach of

4 the duty owed to Mrs. Kekona.

5 These breaches of duty owed by Alaska Airlines and its agent Huntleigh were proximate

6 causes of Mrs. Kekona’s fall down the escalator, which occurred as she attempted to travel

7 unassisted between her gates. It is undisputed that Mrs. Kekona’s fall down the escalator resulted

8 in injuries which led to her death months later, after she incurred substantial pain and suffering.

9 The Estate of Bernice Kekona is entitled to recover reasonable compensation for these injuries and

10 the damages caused by Alaska’s negligence, including the loss of consortium of Mrs. Kekona’s

11 eight children.

12 II. FACTS

13 A. Gate-to-Gate Escort Service was Repeatedly Requested on Behalf of Mrs. Kekona

Prior to Her Arrival in Portland.

14

On March 12, 2017, Mrs. Kekona, with the assistance of her granddaughter, purchased an

15

on-line, round-trip ticket from Alaska for transportation between Spokane and Maui to visit her

16

family. At the time of purchase, they electronically requested Alaska provide Mrs. Kekona with

17

gate-to-gate escort assistance between her connecting flights. Immediately after the on-line

18

purchase, Mrs. Kekona’s granddaughter called Alaska to confirm gate-to-gate service would be

19

provided to Mrs. Kekona. On May 6, 2017, when checking Mrs. Kekona in for her flight to Maui

20

the family again confirmed gate-to-gate assistance with the ticket agent.

On June 6, 2017, the day before Mrs. Kekona’s return to Spokane from Maui, her grandson,

21

who worked at the Maui airport, confirmed for a third time with an Alaska agent that she would

22

receive gate-to-gate assistance in Portland. Lastly, on June 7, 2017, just prior to departure, a

23

LUVERA LAW FIRM

24 PLAINTIFF’S TRIAL BRIEF - 3 ATTORNEYS AT LAW

6700 COLUMBIA CENTER • 701 FIFTH AVENUE

SEATTLE, WASHINGTON 98104

(206) 467-6090

1 different grandson confirmed at the Maui airport counter that Alaska would provide a gate-to-gate

2 escort in Portland. This last confirmation led to the Alaska gate agent placing a custom “need”

3 entry in Mrs. Kekona’s passenger record to “double check” the escort assistance would be provided

4 in Portland. The grandson also had his name and contact number added to the reservation in case

5 any issues arose.

6 Alaska’s records include a Special Services Request (“SSR”) showing two separate

7 requests for gate-to-gate escort assistance:

8 (1) “WCHR ASSIST TO AND FROM GATES AT ALL POINTS;” and

9 (2) “NN ASSISTANCE TO GATES AT ALL POINTS.”

10 Alaska admits these requests required gate-to-gate escort assistance be provided in

11 Portland.

12 B. Alaska Never Informed Huntleigh of Mrs. Kekona’s Need for Gate-to-Gate Escort

Assistance.

13

Huntleigh was Alaska’s agent for providing all wheelchair services at the Portland Airport.

14

However, Alaska never informed Huntleigh that Mrs. Kekona needed gate-to-gate escort

15

assistance in Portland. The Huntleigh dispatch wheelchair log does not show a request for gate-

16

to-gate assistance for Mrs. Kekona’s flight, a request always recorded on the log.

17

C. Huntleigh’s Communications with Mrs. Kekona Did Not Relate to Gate-to Gate

18 Assistance.

19 Huntleigh’s two wheelchair attendants, Nandi Pokhrel and Ruslan Dudko, were only

20 dispatched to perform an aisle chair service for Mrs. Kekona – i.e., transport her from the plane to

her electric wheelchair in a small uncomfortable chair specially designed for airplane aisles. Mr.

21 Pokhrel will testify there was no discussion with Mrs. Kekona about whether she needed gate-to-

22 gate assistance to her next flight. This is because he was never told that gate-to-gate service was

23 requested. Mr. Pokhrel believed Portland was Mrs. Kekona’s final destination and did not know

LUVERA LAW FIRM

24 PLAINTIFF’S TRIAL BRIEF - 4 ATTORNEYS AT LAW

6700 COLUMBIA CENTER • 701 FIFTH AVENUE

SEATTLE, WASHINGTON 98104

(206) 467-6090

1 she had a connecting flight to Spokane. Mr. Pokhrel testified that once the aisle chair service was

2 performed, he believed he had fully accomplished his task.

3 Huntleigh employees are trained to ask passengers after an aisle chair transfer whether they

4 are comfortable. Mr. Pokhrel complied with that training. Mr. Pokhrel specifically identifies that

5 his passing comment to Mrs. Kekona of “you need more help?” related to Mrs. Kekona’s

6 “comfort” in her chair following the transfer, and in no way related to the gate-to-gate services.

7 It is also notable that English is not Mr. Pokhrel’s primary language. He moved from Nepal

8 to the United States in 2009. His strong accent makes it difficult to understand him. Mr. Pokhrel

9 testified that he was not sure if Mrs. Kekona could hear him.

10 If Mr. Pokhrel had been aware Mrs. Kekona requested gate-to-gate assistance, that would

11 have triggered a series of questions and actions such as checking her boarding pass, flight

12 number/gate number, and further conversation with the gate agent, among other actions. Had

13 Alaska informed the Huntleigh agents that there was a contact number on her record, the Huntleigh

14 agents may also have contacted the family.

15 The second Huntleigh wheelchair attendant, Mr. Dudko, filled out a Voluntary Statement

16 on the night of the incident that made no reference to Mrs. Kekona declining assistance or refusing

17 gate-to-gate service in any manner. Mr. Dudko states that he (incorrectly) directed Mrs. Kekona

18 to leave the secured area and exit the airport. Mr. Dudko explains that he provided this incorrect

19 direction because he did not know that she had requested gate-to-gate assistance. Had Alaska

20 communicated to Mr. Dudko that Mrs. Kekona had requested gate-to-gate assistance, he would

have escorted her to her next gate, without question. It is Huntleigh’s practice when providing

21 gate-to-gate assistance to direct the passenger to the elevator and away from the escalators.

22 Huntleigh’s investigation revealed that Mrs. Kekona was only offered direction to

23 baggage/exiting the airport. Huntleigh’s wheelchair log for that night referenced the abbreviation

LUVERA LAW FIRM

24 PLAINTIFF’S TRIAL BRIEF - 5 ATTORNEYS AT LAW

6700 COLUMBIA CENTER • 701 FIFTH AVENUE

SEATTLE, WASHINGTON 98104

(206) 467-6090

1 “GA,” meaning “give away.” If Mrs. Kekona had declined gate-to-gate assistance, Huntleigh

2 would not use the abbreviation GA.

3 D. Huntleigh Wheelchair Attendants Provide Gate-to-Gate Services Without

Questioning When Informed That It Has Been Requested.

4

Alaska and Huntleigh agree it is important for the wheelchair attendants to know gate-to-

5

gate service has been requested. When informed of a gate-to-gate assistance request, Huntleigh

6

has trained its attendants to provide the service without questioning the passenger. Both wheelchair

7

attendants for flight 862 would have escorted Mrs. Kekona to her next gate without questioning

8

her if they had been informed such service had been requested in advance.

9

E. Alaska’s Records Show that Mrs. Kekona Was Never Offered Gate-to-Gate

10 Assistance.

11 In Alaska’s first contact with the family on the night of Mrs. Kekona’s fall, Alaska

12 inaccurately accused the family of not requesting gate-to-gate service. Alaska made the same

13 claim in its first contact with Maui personnel.

14 On the night of the fall, acting Alaska Manager Joy Drechsler assumed responsibility for

15 investigating Mrs. Kekona’s fall. She sent an email that night summarizing her investigation:

16 After speaking with the family and investigating the situation, it appears there was

a request for Meet and Assist at all points (see attached SSR comments) but

17 obviously there was no Huntleigh rep with her at the time. I followed up with the

Huntleigh supervisor who confirmed that a Huntleigh rep was dispatched to help

18 with aisle chair for Mrs. Kekona and the transfer to her scooter. The Huntleigh

rep then asked if she needed assistance down to baggage service (not realizing

19 she was connecting) and she replied “no” so he left. This Huntleigh rep is

supposed to be providing a written statement.

20

Alaska never documented that Mrs. Kekona purportedly declined the service. Alaska’s

own investigation concluded that Mrs. Kekona was only offered help to baggage, and when she

21

said no, the Huntleigh representatives left her. This conclusion is corroborated by Mr. Dudko’s

22

Voluntary Statement on the night of the incident in which he stated he directed Mrs. Kekona to

23

LUVERA LAW FIRM

24 PLAINTIFF’S TRIAL BRIEF - 6 ATTORNEYS AT LAW

6700 COLUMBIA CENTER • 701 FIFTH AVENUE

SEATTLE, WASHINGTON 98104

(206) 467-6090

1 leave the secured area and exit the airport, presumably to baggage. Alaska does not doubt the

2 accuracy of Ms. Drechsler’s investigation or email.

3 That same night, Alaska’s Lead Customer Service Agent Yuko Tacha spoke with gate

4 agent Robert Scarbrough, who told her that nothing out of the ordinary had occurred that evening.

5 After speaking with Mr. Scarbrough, Huntleigh and Ms. Drechsler, Ms. Tacha sent an email to her

6 supervisors at the conclusion of her investigation stating there was a possible service failure and

7 recommended further investigation—which never occurred.

8 Similarly, on the night of Mrs. Kekona’s fall, Lead Customer Service Agent Mahea

9 Kahoana for DGS, Alaska’s agent for ticketing and gate services at the Maui Airport where Mrs.

10 Kekona departed from, investigated what happened to Mrs. Kekona. This investigation occurred

11 during Ms. Kahoana’s shift as Alaska’s agent. Sasha Tabon, Ms. Kahoana’s supervisor at the time,

12 assisted in the investigation and oversaw Ms. Kahoana’s efforts.

13 Ms. Kahoana called Alaska’s “ops center” in Portland and was informed by an Alaska

14 representative that she had spoken with Scarbrough, and “the gate agent did not remember a

15 passenger with a scooter and any details.” Ms. Kahoana was then told by a separate Alaska

16 employee that Mrs. Kekona had been abandoned, which she documented in Alaska’s Passenger

17 Name Record (“PNR”):

18 PAX TRAVELING WITH ELECTRIC SCOOTER. FAMILY CALLED IN ONE

DAY BEFORE THE FLIGHT AND HAD ALL WCHR ASSISTANCE CODES

19 ADDED TO HER RESERVATION. SHE CHECKED IN AT THE OGG [MAUI]

COUNTER AND ONCE AGAIN MADE SURE ALL SSRS WERE IN HER

20 RESERVATION. UPON ARRIVAL INTO PDX SHE WAS LEFT WITH HER

SCOOTER AND NO ONE TO ASSIST HER TO HER CONNECTION GATE.

SHE ATTEMPTED TO GET TO HER CONNECTION GATE HERSELF.

21 This information came from Alaska personnel in Portland on the night of the fall. There

22 was no mention that Mrs. Kekona declined gate-to-gate service. These notes were entered during

23 Ms. Kahoana’s shift as Alaska’s agent through her access to the PNR as part of her employment.

LUVERA LAW FIRM

24 PLAINTIFF’S TRIAL BRIEF - 7 ATTORNEYS AT LAW

6700 COLUMBIA CENTER • 701 FIFTH AVENUE

SEATTLE, WASHINGTON 98104

(206) 467-6090

1 Alaska’s agents are trained to accurately record information in the PNR and to document refusals

2 of special services that are requested in advance. However, Mr. Scarbrough did not document

3 anything in Mrs. Kekona’s PNR.

4 F. Mrs. Kekona Was Abandoned in Portland.

5 Mrs. Kekona had accepted and received gate-to-gate assistance on past several airline

6 flights. In 2016, she traveled to Maui and back by herself on Delta Airlines using gate-to-gate

7 assistance without issue or injury. On the trip in question, she also accepted and received gate-to-

8 gate assistance in Seattle on her flight to Maui without incident or injury.

9 Following her injury at the Portland airport, Mrs. Kekona told her daughters Darlene

10 Bloyed and Mary Kekona that the Huntleigh wheelchair attendants put her in her wheelchair in

11 the sky bridge, pointed toward the top of the sky bridge, and when she got to the top of the sky

12 bridge nobody was there to escort her and she became confused. She also told them she mistakenly

13 took the escalator while looking for the elevator. Similarly, Mrs. Kekona told her granddaughter

14 Danielle Kekahuna that after being put in her wheelchair in the sky bridge, the people just pointed,

15 she followed in the direction they pointed and no one was there, and they left. Mrs. Kekona told

16 Danielle she followed the crowd and then got to the escalator thinking it was the elevator.1

17 At no time did Mrs. Kekona ever indicate to any witness that she declined the gate-to-gate

18 service. Instead, she consistently stated that Alaska abandoned her. Without the requested escort,

19 and as demonstrated in the Port of Portland surveillance videos, Mrs. Kekona became confused

20 and began wandering through the airport trying to find her way, stopping at the airport store and

security for directions before ending up on the escalator thinking it was the elevator.

21

1

Mrs. Kekona’s post-incident conversations with her daughters and with plaintiff’s expert Joellen

22 Gill were excluded under the Court’s orders on Defense MIL No. 5, but plaintiff may ask for

reconsideration of that ruling in the context of other evidence presented at trial.

23

LUVERA LAW FIRM

24 PLAINTIFF’S TRIAL BRIEF - 8 ATTORNEYS AT LAW

6700 COLUMBIA CENTER • 701 FIFTH AVENUE

SEATTLE, WASHINGTON 98104

(206) 467-6090

1 G. Mrs. Kekona’s Family Informed Alaska Airlines When Booking Her Flight that Mrs.

Kekona Could Become Confused In Unfamiliar Places.

2

Alaska was informed that Mrs. Kekona could become confused in unfamiliar places, but

3

failed to communicate that to Huntleigh and/or the gate agent in Portland. Mrs. Kekona’s family

4

requested gate-to-gate assistance because she was elderly, diabetic, wore glasses, had trouble

5

hearing, had an amputated leg, had partial paralysis on one side of her body, spoke in broken

6

English and could become confused in unfamiliar places, such as the Portland Airport. Bernice

7

would also have trouble operating her electric wheelchair at times. Immediately after booking Mrs.

8

Kekona’s flight, her granddaughter called Alaska to confirm gate-to-gate service would be

9

provided and told the Alaska reservation agent that Mrs. Kekona could become confused.

10

According to Alaska, the custom special service entry on Mrs. Kekona’s SSR “NN Assistance to

11

gates at all points” indicates that she needed gate-to-gate assistance because she had a potential

12

“cognitive impairment.”

13

H. Alaska’s Inadequate Procedures Regarding Special Services Requests.

14

Alaska provided no training or procedure guidelines to its gate agents on how to correctly

15

or uniformly communicate special service requests to Huntleigh. Alaska had no written policies

16

or procedures requiring that gate agents inform Huntleigh in writing or digitally of special services

17

requested in advance. In fact, Alaska claims it is not required to communicate gate-to-gate requests

18

made in advance to Huntleigh at all--a contention previously rejected by the Court on summary

19

judgment. Further, Alaska provides no training to Huntleigh, its agent, regarding the ACAA,

20

despite Alaska’s nondelegable duty to ensure they meet its requirements as if Alaska itself had

provided them.

21

III. COURT’S EVIDENTIARY AND LEGAL RLINGS

22

Judge Rogers has issued several orders on Alaska’s legal duties and the admissibility of

23

LUVERA LAW FIRM

24 PLAINTIFF’S TRIAL BRIEF - 9 ATTORNEYS AT LAW

6700 COLUMBIA CENTER • 701 FIFTH AVENUE

SEATTLE, WASHINGTON 98104

(206) 467-6090

1 related evidence which are summarized here:

2 1. Court orders Alaska had duty to communicate requested services to contractor

carrying out the service.

3

On September 23, 2019, the Court denied Alaska’s summary judgment motion, finding

4

admissible evidence existed which, if interpreted in plaintiff’s favor, demonstrated “that Alaska

5

allows parties to book with requested gate-to-gate assistance, that Alaska failed to communicate

6

that Ms. Kekona was booked with this request, and that if Huntleigh representatives had known

7

this they would have, without asking the passenger, escorted that passenger to the next gate.”

8

9/23/19 Order Denying Defendants’ Motion for Summary Judgment and Motion to Strike In Part.

9

Alaska sought clarification of the Court’s September 23, 2019 order, arguing it had no duty

10

under the federal regulations to actually communicate gate-to-gate service requests to Huntleigh.

11

The Court granted Alaska’s motion for clarification, but rejected its argument, ordering that once

12

Alaska gathered gate-to-gate requests from passengers (as it did for Mrs. Kekona), Alaska

13

“undertook a duty per the Code of Federal Regulations to communicate that information to its

14

contractor as if Alaska had provided the service itself.” 11/1/2019 order granting Alaska’s motion

15

for clarification/reconsideration. Alaska tried to revisit this issue through its motion in limine No.

16

21, but the Court refused: “Denied. The Court previously ruled on this issue in its Order on Alaska's

17

Motion for Reconsideration/Clarification.” See 1/14/20 order on Alaska’s motions in limine, at 5.

18

Thus, the law of the case is that Alaska owed a duty to communicate Mrs. Kekona’s request to its

19

contracted service provider, Huntleigh.

20

2. Statements by Alaska employees and agents, including Huntleigh, Horizon, and

DSG, are admissible admissions of party opponents.

21 Judge Rogers initially ruled on this issue at the dispositive motion stage and then reiterated

22 his ruling during motions in limine on January 7, 2020:

23 The statements are attributed to Huntleigh’s employees, Horizon employees and

LUVERA LAW FIRM

24 PLAINTIFF’S TRIAL BRIEF - 10 ATTORNEYS AT LAW

6700 COLUMBIA CENTER • 701 FIFTH AVENUE

SEATTLE, WASHINGTON 98104

(206) 467-6090

1 Alaska employees. These are all admissions of party opponents, ER 801(d)(2),

even if they are in multiple levels of hearsay in the emails, see ER 805. They

2 are admissible. It is true that one of the Huntleigh employees is not identified by

name in an email. This goes to weight, not admissibility. Alaska objects that

3 Huntleigh employees’ statements cannot be a “party opponent” admission. The

Court has already ruled that they are.

4

See 1/7/20 Order on Reserved Motions in Limine (emphasis added). Judge Rogers added a

5

footnote:

6

Alaska also argues that a person that works for Horizon cannot make a party

7 opponent statement. That cannot be a serious argument. Alaska owns Horizon and

used a Horizon employee to investigate this Alaska accident.

8

Id.

9

3. Joy Drechsler’s email and Yuko Tacha’s shift summary email are admissible.

10

In the September 23, 2019 Order Denying Defendants’ Motion for Summary Judgment and

11

Motion to Strike in Part, Judge Rogers held:

12

The Court rules that Drechsler’s e-mail is admissible because the multiple

13 layers of hearsay are met through admissions of a party opponent. The

litigation postures of the parties are not relevant now, but relevant at the time the

14 statements were made, and at that time there was no conflict.

15 (emphasis added).

16 Joy Drechsler, the author of the email addressed above, was a Horizon manager who

17 investigated Mrs. Kekona’s fall the night of the incident for Alaska (she was the only

18 Alaska/Horizon on duty at the time). The email in question includes, in part, statements from

19 Huntleigh employees whom Ms. Drechsler spoke with while investigating Mrs. Kekona’s fall. In

20 ruling the email admissible, the Court recognized that it is irrelevant that Huntleigh and Alaska

may now blame each other for Mrs. Kekona’s fall. The relevant timeframe in analyzing exclusions

21 from hearsay under ER 801(d)(2) is when the statements were made, and at the time all statements

22 in question were made, Huntleigh and Alaska were aligned.

23 At motions in limine, Judge Rogers revisited the admissibility of Ms. Drechsler’s email

LUVERA LAW FIRM

24 PLAINTIFF’S TRIAL BRIEF - 11 ATTORNEYS AT LAW

6700 COLUMBIA CENTER • 701 FIFTH AVENUE

SEATTLE, WASHINGTON 98104

(206) 467-6090

1 along with the testimony of Yuko Tacha, an Alaska employee, and Ms. Tacha’s shift summary

2 email from the night of the incident. The Court repeated its prior ruling that ER 801(d)(2)—

3 admission by party opponent—applied to statements made by Huntleigh, Horizon, and Alaska

4 employees, meaning such statements were admissible “even if they are in multiple levels of

5 hearsay in the emails,” and even though one of the Huntleigh employee’s name was unknown. See

6 1/7/20 Order on Reserved Motions in Limine, at 4.

7 The Court qualified its prior rulings in two regards, but made clear these limited

8 qualifications only applied to use of the “Drechsler and Tacha evidence as substantive evidence.”

9 Id. First, the Court ruled that the brief summaries of what happened contained in the emails require

10 foundation to be admitted as substantive evidence. The Court acknowledged that Ms. Drechsler’s

11 firsthand knowledge of the accident provides foundation for some portions of her brief summary.

12 Second, the Court ruled the “recommendations for next action” are:

13 opinions not typically admissible. Nor do they appear to be the statement of an

agent on behalf of a principal. Plaintiff must demonstrate relevance here, which

14 has not been done thus far. Once again, for substantive purposes only, these

portions of the statements are not admissible.

15

Id.

16

4. Mahea Kahoana’s testimony and electronic notes are admissible.

17

The Court rules that Mahea Kahoana’s notes are admissible. While she may have

18 entered notes motivated in part by her relationship to the family, the relevant

inquiry is whether she would have acted in the same way in any case in the course

19 of her work. The plaintiff has proffered sufficient foundation to meet this burden

on the prima facie basis.

20

9/23/19 Order Denying Defendants’ Motion for Summary Judgment and Motion to Strike In Part.

Alaska contracted with DSG to provide gate services at the Maui Airport. Ms. Kahoana

21

was a lead customer service agent for DSG. During her shift the night of Mrs. Kekona’s fall, she

22

investigated the incident through phone conversations with Alaska representatives located in

23

LUVERA LAW FIRM

24 PLAINTIFF’S TRIAL BRIEF - 12 ATTORNEYS AT LAW

6700 COLUMBIA CENTER • 701 FIFTH AVENUE

SEATTLE, WASHINGTON 98104

(206) 467-6090

1 Portland. She recorded portions of those calls in typed, electronic notes maintained in Alaska’s

2 Passenger Name Record (PNR) electronic system. As ruled by the Court, those notes are

3 admissible pursuant to ER 801(d)(2).

4 Judge Rogers reiterated his ruling regarding the admissibility of Ms. Kahoana notes when

5 ruling on Alaska’s motions in limine:

6 Ms. Kahoana is a fact witness. Plaintiff cannot ask her hypothetical questions that

border on expert testimony. Ms. Kahoana can, however, testify regarding what she

7 does as part of her employment. To the extent this motion seeks to alter or amend

the Court’s summary judgment order, the motion is denied.

8

See 1/14/20 order on Alaska’s motions in limine, at 4.

9

IV. SUMMARY OF TRIAL ISSUES

10

The issues for the jury to determine in this case are set forth in Plaintiffs’ Proposed Jury

11

Instruction No. 5. In accordance with that instruction, set forth below, Alaska is negligent for

12

breaching any of the below duties imposed under the ACAA, which set forth where and when

13

assistance must be provided to passengers between flights, and the heightened care owed by

14

common carrier with respect to a disabled passenger whose known disabilities increase the hazards

15

of travel:

16

As a common carrier, Alaska Airlines has the following duties under the federal

17 Air Carrier Access Act regarding when and where it must provide assistance to

passengers moving through the airport before, between, and after flights:

18

(1) Alaska Airlines must provide or ensure the provision of assistance requested by or

19 on behalf of a passenger with a disability in transportation between gates to make

a connection to another flight;

20

(2) Alaska Airlines personnel must have awareness and appropriate responses to

passengers with physical, sensory, mental, and emotional disabilities, including

how to distinguish among the differing abilities of individuals with such

21 disabilities; and

(3) Alaska Airlines must ensure that its contractors that provide services to the public

22

comply with the Air Carrier Access Act.

23

LUVERA LAW FIRM

24 PLAINTIFF’S TRIAL BRIEF - 13 ATTORNEYS AT LAW

6700 COLUMBIA CENTER • 701 FIFTH AVENUE

SEATTLE, WASHINGTON 98104

(206) 467-6090

1 In addition, as a common carrier, Alaska Airlines also has the following duties under

Washington law regarding how airline agents interact with passengers with disabilities who

2 request assistance in moving through the airport:

3 (1) Alaska Airlines must exercise the highest degree of care consistent with

operation of its type of transportation and its business as a common carrier

4 to protect its passengers from harm; and

5 (2) When it is aware that a passenger is mentally or physically disabled so that the

hazards of travel are increased as to that passenger, Alaska Airlines must provide

6 that amount of additional care which is reasonably required under the circumstances

consistent with the practical operation of its type of transportation and its business

7 as a common carrier.2

8 The failure of Alaska Airlines to comply with any of the foregoing duties is negligence.

9 In addition to disputing violation of these duties, Alaska denies that their breach caused

10 injury. It has asserted an affirmative defense of fault against Mrs. Kekona for “driving her electric

11 wheelchair onto an escalator”, alleging that act was a superseding cause of her injuries. In addition,

12 Mrs. Kekona has asserted claims of fault against three of her family members who held a durable

13 power of attorney for her at the time of this incident. While the Court reserved ruling on the

14 admissibility of any argument or evidence directed at such fault, plaintiff has filed a renewed

15 motion for resolution of this issue to avoid prejudicial error at trial. See Plaintiffs’ Renewed

16 Plaintiff’s Renewed Motion for Order Excluding Evidence of or Reference To Alleged Fault Of

17 Family Members, filed 2/3/21.

18 V. AIR CARRIER ACCESS ACT

19 The federal Air Carrier Access Act (“ACAA”) prohibits an air carrier’s discrimination

20 against disabled travelers. 49 USC § 41705. The parties agree that the ACAA establishes the

specific duties owed by Alaska to Mrs. Kekona. See, Gilstrap v. United Air Lines, Inc., 709 F.3d

21 995, 1010 (9th Cir. 2013). Violations of Department of Transportation regulations codified at 14

22

2

The authority and analysis supporting this instruction, including application of Washington

23 common carrier standards, is set forth in the citations to this proposed instruction.

LUVERA LAW FIRM

24 PLAINTIFF’S TRIAL BRIEF - 14 ATTORNEYS AT LAW

6700 COLUMBIA CENTER • 701 FIFTH AVENUE

SEATTLE, WASHINGTON 98104

(206) 467-6090

1 CFR § 382 are violations of the ACAA, and no proof of intent to discriminate is required. Rowley

2 v. Am. Airlines, 885 F. Supp. 1406, 1410-11 (D. Ore. 1995).

3 Alaska breached the ACAA established standard of care by failing to provide requested

4 gate-to-gate escort services to Mrs. Kekona, in violation of 14 CFR § 382.91(a), and by failing to

5 communicate the special service requests it gathered from Mrs. Kekona, and her family, to its

6 service provider Huntleigh, in violation of 14 CFR § 382.15.

7 The source of Alaska's nondelegable duty is 14 C.F.R. § 382.15, which provides in relevant

8 part:

9 (a) As a carrier, you must make sure that your contractors that provide services to

the public (including airports where applicable) meet the requirements of this

10 part that would apply to you if you provided the services yourself.

11 (b) As a carrier, you must include an assurance of compliance with this part in your

contracts with any contractors that provide services to the public that are subject

12 to the requirements of this part. Noncompliance with this assurance is a material

breach of the contract on the contractor's part.

13

(1) This assurance must commit the contractor to compliance with all applicable

14 provisions of this Part in activities performed on behalf of the carrier.

15 ***

16 (c) You remain responsible for your contractors' compliance with this part and

for enforcing the assurances in your contracts with them.

17

14 C.F.R. § 382.15 (emphasis added).

18

Section 14 C.F.R. § 382.91 of the ACAA titled “What assistance must carriers provide to

19

passengers with a disability in moving within the terminal,” imposes a specific nondelegable duty

20

on Alaska with respect to gate-to-gate service requests, mandating that it "provide or ensure" that

a request for gate-to-gate service made by or on behalf of a passenger with a disability, is met:

21

(a) As a carrier, you must provide or ensure the provision of assistance

22 requested by or on behalf of a passenger with a disability, or offered by carrier

or airport operator personnel and accepted by a passenger with a disability, in

23 transportation between gates to make a connection to another flight.

LUVERA LAW FIRM

24 PLAINTIFF’S TRIAL BRIEF - 15 ATTORNEYS AT LAW

6700 COLUMBIA CENTER • 701 FIFTH AVENUE

SEATTLE, WASHINGTON 98104

(206) 467-6090

1 (emphasis added).

2 The ACAA regulations at issue impose a number of non-delegable duties upon Alaska,

3 including providing gate-to-gate assistance to disabled passengers when requested; ensuring AA

4 contractors are “trained to proficiency” on regulations affecting disabled passengers; and ensuring

5 AA contractors meet all ACAA regulatory requirements. 14 C.F.R. § 382.91(a); 382.27(e);

6 382.141(a)(1) and (2). At all times, the carrier remains responsible for contractor compliance. 14

7 C.F.R. § 382.15.3

8 It is worth noting the special services at issue in this case were “requested by or on behalf

9 of” Mrs. Kekona; therefore, the duty to provide gate-to-gate service arises at the time of the request

10 and the offer and acceptance portion of the regulation, which is set off by commas, is not necessary

11 or applicable to this situation. Additionally, 14 CFR § 382.11(a)(2) is not applicable because it

12 relates to forcing disabled individuals to use services “the individual does not request,” and in this

13 case it is undisputed the gate-to-gate escort services had been requested.

14 As a matter of law (and common sense), Alaska cannot “ensure” requested assistance

15 without communicating the request to the employees or agents it has designated to provide them.

16 This duty of reasonable care in handling service requests -- by whatever means received -- is

17 consistent with Alaska's non-delegable duty to ensure service requests are fulfilled. See Gilstrap

18 v. United Air Lines, Inc., 709 F.3d 995, 1010 (9th Cir. 2013) (tort plaintiffs may incorporate the

19 ACAA regulations as describing the duty element of negligence, and rely on state law for “the

20 other negligence elements (breach, causation, and damages); Glass v. Nw. Airlines, Inc., 798 F.

3

Although the Court dismissed plaintiff’s independent “failure to train” claims on summary

21 judgment based on LaPlant v. Snohomish Cty., 162 Wn. App. 476, 480 (2011) (holding that a

claim for negligent hiring, training, and supervision is generally improper where agent’s actions

22 concededly occurred within the course and scope of agency), evidence as to required proficiency

of Alaska’s contractors when dealing with disabled passengers remains relevant and admissible to

23 prove breach of Alaska’s nondelegable duties of performance.

LUVERA LAW FIRM

24 PLAINTIFF’S TRIAL BRIEF - 16 ATTORNEYS AT LAW

6700 COLUMBIA CENTER • 701 FIFTH AVENUE

SEATTLE, WASHINGTON 98104

(206) 467-6090

1 Supp. 2d 902, 912 (W.D. Tenn. 2011) (“Northwest arguably assumed a duty to provide a

2 wheelchair for Glass based on Plaintiff's having requested wheelchair service when she purchased

3 his ticket on August 28, 2011”). In accordance with this authority, the Court has already ruled on

4 summary judgment that Alaska’s solicitation of gate-to-gate requests during the booking process

5 required that those requests be conveyed to its contractors like Huntleigh, and plaintiff has

6 proposed a jury instruction regarding that established duty. Dkt. 65.

7 The ACAA statutory and regulatory language does not directly address a disabled

8 passenger declining special services previously requested. DOT guidance on implication of the

9 ACAA includes detailed guidelines for how airline personnel should interact with persons with

10 disabilities. Air carriers, and their agents, are required to “make a reasonable judgment considering

11 all available information.” Nondiscrimination on the Basis of Disability, 70 FR 41482-01, 41486-

12 87, 2005 WL 1667262 (July 19, 2005). This reasonable judgment includes asking “an individual’s

13 ability to perform specific air travel-related functions, such as…walking through the airport, etc.”

14 Id. at 41489. Examples include, asking the passenger detailed questions such as “Can you walk

15 from this gate to your connecting gate?” Id. This also includes specifically asking a person needing

16 transportation between gates “if the person would prefer to be pushed or not.” Id. at 41506.

17 Airlines are required to train their employees to be aware of passengers with physical and mental

18 disabilities and how to appropriately and effectively communicate with those passengers. Id. at

19 41510. These guidelines substantiate the relevance of the information provided to Alaska by Mrs.

20 Kekona’s family regarding her confusion in unknown environments. See Dkt. 178 (Memorandum

of Plaintiff Re Relevance of Cognitive Issues).

21 It is undisputed that Alaska owed Mrs. Kekona’s duties pursuant to the ACAA, and that a

22 breach of those duties is recoverable through a state negligence action. Ms. Bloyed will establish

23 at trial Alaska’s breach of multiple duties owed to Mrs. Kekona to support the Estate’s claim of

LUVERA LAW FIRM

24 PLAINTIFF’S TRIAL BRIEF - 17 ATTORNEYS AT LAW

6700 COLUMBIA CENTER • 701 FIFTH AVENUE

SEATTLE, WASHINGTON 98104

(206) 467-6090

1 negligence.

2 VI. CAUSATION

3 “A proximate cause is one that in natural and continuous sequence, unbroken by an

4 independent cause, produces the injury complained of and without which the ultimate injury would

5 not have occurred.” Bernethy v. Walt Failor's, Inc., 97 Wn.2d 929, 935 (1982). Proximate cause

6 has two elements: factual “but for” causation and legal causation. Schooley v. Pinch's Deli Mkt.,

7 Inc., 134 Wn.2d 468, 474 (1998). While factual cause is based on an actual connection between

8 an act and an injury, “legal cause is grounded in policy determinations as to how far the

9 consequences of a defendant's acts should extend.” Id. at 478. Proper analysis of proximate cause

10 looks to “whether the result of the act is within the ambit of the hazards covered by the duty

11 imposed upon defendant.” Id.; see Rikstad v. Holmberg, 76 Wn.2d 265, 269 (1969) (It is only

12 necessary that the injury fall within the “general field of danger”).

13 Recently, the Washington Supreme Court discussed proximate cause in detail in the

14 criminal case of State v. Frahm, 193 Wn.2d 590 (2019) and affirmed a finding that a defendant

15 who caused a motor vehicle accident and fled the scene proximately caused the subsequent death

16 of a passerby who was rendering aid and was struck by a different vehicle after the defendant fled.

17 Considering the Supreme Court’s broad application of the proximate cause analysis, Mrs.

18 Kekona’s fall was clearly within the “general field of danger” presented by negligently failing to

19 communicate requested special services and failing to provide gate-to-gate service to an easily

20 confused and potentially cognitively impaired, elderly passenger.

Had Alaska informed Huntleigh that Mrs. Kekona had requested gate-to-gate assistance,

21 Huntleigh confirms it would have escorted her to her next gate, without question. Even Alaska’s

22 human factors expert believes that Mrs. Kekona’s fall was likely a result of her cognitive

23 limitations. Likewise, Plaintiff’s human factors expert will opine that Mrs. Kekona’s fall, and

LUVERA LAW FIRM

24 PLAINTIFF’S TRIAL BRIEF - 18 ATTORNEYS AT LAW

6700 COLUMBIA CENTER • 701 FIFTH AVENUE

SEATTLE, WASHINGTON 98104

(206) 467-6090

1 other accidents like her fall, were foreseeable. To that end, Plaintiff’s human factors expert JoEllen

2 Gill opined that it was reasonably foreseeable that someone with cognitive and visual impairments

3 who has asked for assistance to travel between gates and is left on her own could drive onto the

4 escalator and get hurt, and that it is reasonably foreseeable, without the assistance of a gate-to-gate

5 escort, Mrs. Kekona would become confused in a large airport she has never been to that requires

6 a change in levels to reach the departure gate, and that Mrs. Kekona did not knowingly and

7 voluntarily encounter the escalator believing it was the elevator. Ms. Gill also opines that the

8 escalator is a reasonably foreseeable mechanism of injury where the elevator is hidden around the

9 corner, that the escalator was not an open and obvious risk to Mrs. Kekona who suffered from

10 cognitive and visual impairments, but instead, a foreseeable risk, and that such failure to properly

11 communicate requested services and provide Mrs. Kekona gate-to-gate escort service caused her

12 injuries.

13 Legal causation is a policy judgment to assure defendant’s conduct is sufficiently related

14 to the injury to justify imposition of responsibility. M.H. v. Corp. of Catholic Archbishop of

15 Seattle, 162 Wn. App. 183 (2011). “Consequently, the existence of legal causation between two

16 events is determined on the facts of each case upon mixed considerations of logic, common sense,

17 justice, policy and precedent.” Skeie v. Mercer Trucking Co., 115 Wn. App. 144, 151 (2003). A

18 major consideration in determining legal causation is whether the conduct of the negligent party

19 was the type of conduct that increased the risk of this particular injury, or whether the connection

20 between the two may be “the merest of chances.” Channel v. Mills, 77 Wn. App. 268, 274 (1995).

Mrs. Kekona’s injuries occurred in close proximity in time and place to Alaska’s

21 negligence. Alaska’s failure to properly communicate requested services to its service provider,

22 and failure to provide the requested gate-to-gate escort, drastically increased the risk that a disabled

23 person, such as Mrs. Kekona, could get injured due to confusion while moving from her arrival

LUVERA LAW FIRM

24 PLAINTIFF’S TRIAL BRIEF - 19 ATTORNEYS AT LAW

6700 COLUMBIA CENTER • 701 FIFTH AVENUE

SEATTLE, WASHINGTON 98104

(206) 467-6090

1 gate to her departure gate. The connection between Alaska’s negligence and the resulting injuries

2 is logical and common sense, sufficient to support legal causation. Anderson v. Dreis & Krump

3 Mfg. Corp., 48 Wn. App. 432, 443 (1987) (“a defendant will not be relieved of responsibility

4 simply because the exact manner in which the injury occurred could not be anticipated”; sequence

5 of events need not be foreseeable).

6 Ms. Bloyed will establish at trial that Alaska’s breach of its duties owed to Mrs. Kekona

7 were proximate causes of Mrs. Kekona’s fall down the escalator and related injuries sufficient to

8 support the Estate’s negligence claim. Because there may be more than one proximate cause of

9 injury, the jury may consider under WPI 15.01 whether Mrs. Kekona’s alleged comparative fault

10 was an additional cause of injury. However, as her fall does not constitute a superseding cause of

11 injury, WPI 15.05 or 15.01.01 should not be given.

12 VII. ALLEGED DECLINATION OF REQUESTED GATE-TO-GATE ESCORT

13 The ACAA statutory language, and enacting regulations, do not address, in any manner, a

14 disabled person declining a previously requested special service. Throughout this litigation,

15 Alaska attempts to expand 14 C.F.R. § 382.11(a)(2) to apply to such a situation, but it does not,

16 because that portion of the regulation specifically references special services “that the individual

17 does not request.” As indicated above in Section IV, the ACAA does directly require that

18 requested special services must be provided, and the failure to do so is an act of discrimination. 14

19 CFR § 382.91(a). Therefore, what amounts to declining a requested special service, so as to

20 alleviate an air carrier from its duties under the ACAA, is not a matter of direct statutory

interpretation, and Alaska’s arguments that service was declined must be considered in the context

21 of the evidence of Alaska’s and its agents’ interactions with Ms. Kekona, the affirmative training

22 duties and the heightened standard owed by a common carrier. See Plaintiff’s Proposed Instruction

23 No. 5 and citations thereto. Jury instructions attempting to define a declination of service are

LUVERA LAW FIRM

24 PLAINTIFF’S TRIAL BRIEF - 20 ATTORNEYS AT LAW

6700 COLUMBIA CENTER • 701 FIFTH AVENUE

SEATTLE, WASHINGTON 98104

(206) 467-6090

1 unsupported by regulation and improperly

2 Guidance on implementing the ACAA from the DOT does encourage air carriers and

3 service providers to dialogue with the passenger in relation to the passenger’s needs. Airlines are

4 required to “make a reasonable judgment considering all available information.”

5 Nondiscrimination on the Basis of Disability, 70 FR 41482-01, 41486-87, 2005 WL 1667262 (July

6 19, 2005). This reasonable judgment includes asking “an individual’s ability to perform specific

7 air travel-related functions, such as…walking through the airport, etc.” Id. at 41489. Examples

8 include, asking the passenger detailed questions such as “Can you walk from this gate to your

9 connecting gate?” Id. This also includes specifically asking a person needing transportation

10 between gates “if the person would prefer to be pushed or not.” Id. at 41506. Airlines are required

11 to train their employees to be aware of passengers with physical and mental disabilities and how

12 to appropriately and effectively communicate with those passengers. Id. at 41510.

13 VIII. CONCLUSION

14 Mrs. Kekona was a lively, loving mother and grandmother who treasured the ability to visit

15 her family in Maui. However, due to her disabilities she required assistance from her air carrier to

16 travel safely. The federal government enacted the ACAA to assure that air carriers provide such

17 assistance, when requested, so that travelers like Mrs. Kekona can enjoy the benefits of air travel

18 in the United States. Sadly, Alaska completely failed to appreciate the requirements of the ACAA,

19 failed to inform its service provider of Mrs. Kekona’s requested gate-to-gate escort service, and

20 failed to provide the needed assistance. Abandoned in the Portland airport by Alaska, Mrs. Kekona

tragically fell down an escalator attempting to make it to her connecting gate. Her injuries from

21 the fall failed to resolve, leading to infection, an amputation, and her death.

22 Ms. Bloyed, the Personal Representative of Mrs. Kekona’s Estate, will present ample

23 evidence at trial that Alaska’s negligence was a proximate cause of Mrs. Kekona’s injuries, and

LUVERA LAW FIRM

24 PLAINTIFF’S TRIAL BRIEF - 21 ATTORNEYS AT LAW

6700 COLUMBIA CENTER • 701 FIFTH AVENUE

SEATTLE, WASHINGTON 98104

(206) 467-6090

1 subsequent death. She will ask the jury to hold Alaska responsible for its blatant violations of

2 federally required assistance to a disabled passenger. She will request an award of significant

3 monetary damages, including, but not limited to, compensation for Mrs. Kekona’s months of

4 horrific pain and suffering, significant medical costs, and the loss of consortium of Mrs. Kekona’s

5 eight children. This was an accidental fall that is so tragic because it so easily could have been

6 avoided if Alaska had simply provided the requested assistance.

7 DATED this 3rd day of February, 2021.

8 RANDALL | DANSKIN, P.S. LUVERA LAW FIRM

9 /s/ Brook L. Cunningham /s/ Robert N. Gellatly

Brook L. Cunningham, WSBA #39270 Robert N. Gellatly, WSBA #15284

10 Shamus T. O’Doherty, WSBA #43082 Deborah L. Martin, WSBA #16370

601 W. Riverside Avenue, Suite 1500 701 Fifth Avenue, Suite 6700

11 Spokane, WA 99201 Seattle, WA 98104

Phone: 509-747-2052 Telephone: (206) 467-6090

12 Fax: 509-624-2528 Facsimile: (206) 467-6961

blc@randalldanskin.com robert@luveralawfirm.com

13 sto@randalldanskin.com deborah@luveralawfirm.com

Attorneys for Plaintiff Attorneys for Plaintiff

14

AHREND LAW FIRM PLLC

15

/s/_George M. Ahrend__________________

16 GEORGE M. AHREND, WSBA 25160

Ahrend Law Firm PLLC

17 P.O. Box 816

Ephrata, WA 98823-0816

18 Phone: (509) 764-9000

gahrend@ahrendlaw.com

19

Attorney for Plaintiff

20

21

22

23

LUVERA LAW FIRM

24 PLAINTIFF’S TRIAL BRIEF - 22 ATTORNEYS AT LAW

6700 COLUMBIA CENTER • 701 FIFTH AVENUE

SEATTLE, WASHINGTON 98104

(206) 467-6090

1 CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

2

I certify that a true and correct copy of the foregoing was sent to the following parties in

3

the manner indicated below:

4

John Fetters X E-Service

5 Caryn Geraghty Jorgensen X Electronic Mail

Brett MacIntyre

☐ Fax Transmission

6 Stokes Lawrence, P.S.

1420 Fifth Avenue, Ste. 3000 ☐ First Class Mail

7 Seattle, WA 98101 ☐ Messenger Service

john.fetters@stokeslaw.com ☐ Overnight Delivery

8 caryn.jorgensen@stokeslaw.com

brett.macintyre@stokeslaw.com

9

Attorneys for Defendant Alaska Airlines, Inc.

10

I declare under penalty of perjury, under the laws of the State of Washington that the

11

foregoing is true and correct.

12

Executed this 3rd day of February, 2021, in Seattle, Washington.

13

14 /s/ Heather D. Thweatt

LUVERA LAW FIRM

15 6700 Columbia Center

701 Fifth Avenue

16 Seattle, WA 98104

Telephone: (206) 467-6090

17 Facsimile: (206) 467-6961

Heather@LuveraLawFirm.com

18

19

20

21

22

23

LUVERA LAW FIRM

24 PLAINTIFF’S TRIAL BRIEF - 23 ATTORNEYS AT LAW

6700 COLUMBIA CENTER • 701 FIFTH AVENUE

SEATTLE, WASHINGTON 98104

(206) 467-6090

You might also like

- Probable Cause Document - Chantail WilliamsDocument2 pagesProbable Cause Document - Chantail WilliamsKGW NewsNo ratings yet

- Ryan Pownall vs. Larry Krasner Lawsuit Main ComplaintDocument29 pagesRyan Pownall vs. Larry Krasner Lawsuit Main ComplaintVictor Fiorillo100% (4)

- 2023 California Peace Officers' Legal and Search and Seizure Field Source GuideFrom Everand2023 California Peace Officers' Legal and Search and Seizure Field Source GuideNo ratings yet

- Unsafe Building MemoDocument15 pagesUnsafe Building MemoKGW NewsNo ratings yet

- Clark County OIS Final LetterDocument11 pagesClark County OIS Final LetterKGW NewsNo ratings yet

- MGPTaxReturn 2021Document93 pagesMGPTaxReturn 2021KGW NewsNo ratings yet

- Virginia Republicans File Suit Over McAuliffe's Paperwork, Declare ItDocument20 pagesVirginia Republicans File Suit Over McAuliffe's Paperwork, Declare ItABC7NewsNo ratings yet

- JetSmarter v. BensonDocument227 pagesJetSmarter v. BensonJetsmarter LitNo ratings yet

- (Steve Nodine Case) Motion To Dismiss - Prosecutorial MisconductDocument3 pages(Steve Nodine Case) Motion To Dismiss - Prosecutorial MisconductWKRGTVNo ratings yet

- Counterclaim in Bubba SuitDocument10 pagesCounterclaim in Bubba Suit10News WTSP100% (2)

- Judge Neal Biggers Denies Zach Scruggs 2255 Motion To Set Aside Guilty PleaDocument44 pagesJudge Neal Biggers Denies Zach Scruggs 2255 Motion To Set Aside Guilty PleaRuss LatinoNo ratings yet

- Judge David Reader Motion COADocument55 pagesJudge David Reader Motion COALansingStateJournal50% (2)

- 20190301900273130001Document8 pages20190301900273130001KCBD DigitalNo ratings yet

- JoHanna Pratt Estate v. Rainier School - Defendants AnswerDocument10 pagesJoHanna Pratt Estate v. Rainier School - Defendants AnswerRay StillNo ratings yet

- Offer of Judgment in Righthaven Copyright Infringement Lawsuit Against Odds On Racing)Document3 pagesOffer of Judgment in Righthaven Copyright Infringement Lawsuit Against Odds On Racing)www.righthavenlawsuits.comNo ratings yet

- 20 08 12 Petition For ContemptDocument39 pages20 08 12 Petition For ContemptDanny ShapiroNo ratings yet

- Hotfile's Motion in Limine To Preclude Use of Pejorative Terms PDFDocument4 pagesHotfile's Motion in Limine To Preclude Use of Pejorative Terms PDFDevlin HartlineNo ratings yet

- Yomade Aborishade - Statement of FactsDocument3 pagesYomade Aborishade - Statement of FactsEmily BabayNo ratings yet

- US vs. KongDocument18 pagesUS vs. KongJoe EskenaziNo ratings yet

- Proposed InstructionsDocument11 pagesProposed Instructionstmccand100% (1)

- Motion For Summary JudgmentDocument4 pagesMotion For Summary JudgmentJoe DonahueNo ratings yet

- Defense Motion To Exclude Evidence/arguments in Victor Hill TrialDocument10 pagesDefense Motion To Exclude Evidence/arguments in Victor Hill TrialJonathan RaymondNo ratings yet

- CHRO DecisionDocument6 pagesCHRO DecisionThe Valley IndyNo ratings yet

- 131 Master Omnibus and JoinderDocument172 pages131 Master Omnibus and JoinderCole StuartNo ratings yet

- U.S. v. Orlando DennisDocument20 pagesU.S. v. Orlando DennisChristopher Robbins100% (1)

- Attorneys For PlaintiffsDocument16 pagesAttorneys For PlaintiffsEquality Case FilesNo ratings yet

- NFL's Proposed Case Management Plan Filing in Brian Flores LawsuitDocument6 pagesNFL's Proposed Case Management Plan Filing in Brian Flores LawsuitAnthony J. PerezNo ratings yet

- 2012-01-13 ORDER Re Filing Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of LawDocument32 pages2012-01-13 ORDER Re Filing Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of LawJack RyanNo ratings yet

- Hendry County Complaint, SoFlo AG, LLC.Document16 pagesHendry County Complaint, SoFlo AG, LLC.News-PressNo ratings yet

- USA v. Flynn - DOJ - Government Notice of Claims - 10.29.19Document5 pagesUSA v. Flynn - DOJ - Government Notice of Claims - 10.29.19Washington ExaminerNo ratings yet

- Richard Fine 9th Circuit Request For Certificate of Appealability & Immediate ReleaseDocument12 pagesRichard Fine 9th Circuit Request For Certificate of Appealability & Immediate ReleaseLeslie DuttonNo ratings yet

- B242499 - Anti-SLAPP Appellant's Opening Brief (AOB) - Scott C Kandel - FinalDocument65 pagesB242499 - Anti-SLAPP Appellant's Opening Brief (AOB) - Scott C Kandel - FinalScott Kandel100% (1)

- Scan002 Review EssayDocument4 pagesScan002 Review EssayJ Alexander VernonNo ratings yet

- SupCo Eric DeanDocument36 pagesSupCo Eric DeanWest Central TribuneNo ratings yet

- Williams Brief Against Judge RecusalDocument5 pagesWilliams Brief Against Judge RecusalIgor BonifacicNo ratings yet

- U.S.A. V DARREN HUFF (ED TN) - 119 - MOTION in Limine To Require The GovernmentDocument6 pagesU.S.A. V DARREN HUFF (ED TN) - 119 - MOTION in Limine To Require The GovernmentJack RyanNo ratings yet

- (Proposed) Order To Change Venue 15CV000014 4-08-16Document2 pages(Proposed) Order To Change Venue 15CV000014 4-08-16L. A. PatersonNo ratings yet

- Micky Rife Motion To SuppressDocument20 pagesMicky Rife Motion To SuppressJohn WeberNo ratings yet

- People v. OrticelliDocument19 pagesPeople v. OrticelliJim OstrowskiNo ratings yet

- Order Granting Defendants' Motion To Dismiss, July 29, 2013.Document5 pagesOrder Granting Defendants' Motion To Dismiss, July 29, 2013.Rahim JivrajNo ratings yet

- Memorandum Supporting Motion For ReconsiderationDocument35 pagesMemorandum Supporting Motion For Reconsiderationleo_donofrio2000No ratings yet

- Pugh Sentencing MemorandumDocument46 pagesPugh Sentencing MemorandumWmar WebNo ratings yet

- In The Court of Appeal of The State of California: AppellantDocument4 pagesIn The Court of Appeal of The State of California: AppellantCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasNo ratings yet

- 20050211a in Re Hamilton Taft - Motion To Recall Mandate Filed by CCADocument6 pages20050211a in Re Hamilton Taft - Motion To Recall Mandate Filed by CCASamples Ames PLLCNo ratings yet

- New York City Motion To Vacate Judgment in Stop and Frisk CaseDocument471 pagesNew York City Motion To Vacate Judgment in Stop and Frisk CaseGeorge ConkNo ratings yet

- Lockwood Complaint & Jury DemandDocument12 pagesLockwood Complaint & Jury DemandMark KlekasNo ratings yet

- Carlos Moore PetitionDocument13 pagesCarlos Moore PetitionAnthony WarrenNo ratings yet

- Minnesota Judicial Training Update: "Judicial Landmines" 20 Common Mistakes Every Judge Should AvoidDocument6 pagesMinnesota Judicial Training Update: "Judicial Landmines" 20 Common Mistakes Every Judge Should AvoidNhu Mai NguyenNo ratings yet

- Kidd Motion For Summary Judgment Case 2:20-cv-03512-ODW (JPRX)Document26 pagesKidd Motion For Summary Judgment Case 2:20-cv-03512-ODW (JPRX)Red Voice NewsNo ratings yet

- Thomas Trent Lewis WebDocument4 pagesThomas Trent Lewis Webaloc904160No ratings yet

- 29 ALR Fed 7Document104 pages29 ALR Fed 7jlaszloNo ratings yet

- Petition To InterveneDocument4 pagesPetition To InterveneCrains Chicago BusinessNo ratings yet

- 1279 Motion For Acquittal and Mistrial (DS)Document194 pages1279 Motion For Acquittal and Mistrial (DS)Stephen LemonsNo ratings yet

- Manual on the Character and Fitness Process for Application to the Michigan State Bar: Law and PracticeFrom EverandManual on the Character and Fitness Process for Application to the Michigan State Bar: Law and PracticeNo ratings yet

- California Supreme Court Petition: S173448 – Denied Without OpinionFrom EverandCalifornia Supreme Court Petition: S173448 – Denied Without OpinionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Order Denying Alaska's Motion To DismissDocument8 pagesOrder Denying Alaska's Motion To DismissKGW NewsNo ratings yet

- Richard Allen - MTN Transcripts PDFDocument2 pagesRichard Allen - MTN Transcripts PDFMatt Blac inc.No ratings yet

- Motion For Transcript - Judge GullDocument5 pagesMotion For Transcript - Judge GullMatt Blac inc.No ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument4 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Declaration of Evan BariaultDocument11 pagesDeclaration of Evan BariaultBen WinslowNo ratings yet

- Relator's Motion For Leave To ReDocument4 pagesRelator's Motion For Leave To ReMatt Blac inc.No ratings yet

- Multnomah County Prosecutor's Memo On Jean Descamps' DeathDocument2 pagesMultnomah County Prosecutor's Memo On Jean Descamps' DeathKGW NewsNo ratings yet

- Disability Rights Oregon Vs Washington CountyDocument61 pagesDisability Rights Oregon Vs Washington CountyKGW NewsNo ratings yet

- Multnomah County's Report On Homeless Deaths in 2022Document28 pagesMultnomah County's Report On Homeless Deaths in 2022KGW News100% (1)

- Statement To Jo Ann HardestyDocument1 pageStatement To Jo Ann HardestyKGW News100% (1)

- Lawsuit Against Alaska & Horizon AirDocument30 pagesLawsuit Against Alaska & Horizon AirKGW News100% (1)

- School Meal Map - Portland Teachers StrikeDocument1 pageSchool Meal Map - Portland Teachers StrikeKGW NewsNo ratings yet

- Measure 114 RulingDocument44 pagesMeasure 114 RulingKGW News100% (1)

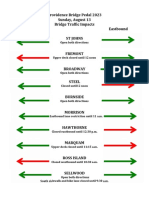

- Bridge ImpactsDocument1 pageBridge ImpactsKGW NewsNo ratings yet

- Portland Parks and Recreation's Summer Free For All Events CalendarDocument4 pagesPortland Parks and Recreation's Summer Free For All Events CalendarKGW NewsNo ratings yet

- Probable Cause Moses Jacob LopezDocument1 pageProbable Cause Moses Jacob LopezKGW NewsNo ratings yet

- Madision High School Rennovation PlansDocument85 pagesMadision High School Rennovation PlansKGW NewsNo ratings yet

- Measure 114 Federal Judge RulingDocument122 pagesMeasure 114 Federal Judge RulingKGW News100% (2)

- MGPTaxReturn 2020Document64 pagesMGPTaxReturn 2020KGW NewsNo ratings yet

- 205 Sunnyside, LLC V. Clackamas County Court DocumentsDocument38 pages205 Sunnyside, LLC V. Clackamas County Court DocumentsKGW NewsNo ratings yet

- Portland Police Association Final OfferDocument15 pagesPortland Police Association Final OfferKGW NewsNo ratings yet

- Probable Cause Document Attempted Bar RobberyDocument7 pagesProbable Cause Document Attempted Bar RobberyKGW NewsNo ratings yet

- City of Portland Final OfferDocument13 pagesCity of Portland Final OfferKGW NewsNo ratings yet

- Cities Vs Oregon Environmental Rules Lawsuit, Petition For Judicial ReviewDocument157 pagesCities Vs Oregon Environmental Rules Lawsuit, Petition For Judicial ReviewKGW NewsNo ratings yet

- Motion - Stay Previous JudgmentOrderDocument396 pagesMotion - Stay Previous JudgmentOrderKGW NewsNo ratings yet

- Federal Judge Ruling On Measure 114Document43 pagesFederal Judge Ruling On Measure 114KGW NewsNo ratings yet

- Attorney General Letter To The CourtDocument3 pagesAttorney General Letter To The CourtKGW NewsNo ratings yet

- Affidavit For Aidan Michael MurrayDocument4 pagesAffidavit For Aidan Michael MurrayKGW NewsNo ratings yet

- MGPTaxReturn 2019Document49 pagesMGPTaxReturn 2019KGW NewsNo ratings yet

- Prentice Rader Signed VerdictDocument3 pagesPrentice Rader Signed VerdictKGW NewsNo ratings yet

- Oregon National EV InfrastructureDocument141 pagesOregon National EV InfrastructureKGW NewsNo ratings yet

- Kalama Fire Evacuation MapDocument1 pageKalama Fire Evacuation MapKGW NewsNo ratings yet