Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Joint Protection: A Critical Review: Philip Palmer and Jane Simons

Joint Protection: A Critical Review: Philip Palmer and Jane Simons

Uploaded by

Xouya SuizenOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Joint Protection: A Critical Review: Philip Palmer and Jane Simons

Joint Protection: A Critical Review: Philip Palmer and Jane Simons

Uploaded by

Xouya SuizenCopyright:

Available Formats

Joint Protection: A Critical Review

Philip Palmer and Jane Simons

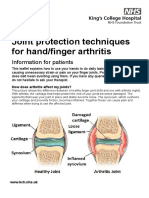

Introduction required when using a gadget or because the gadget facili-

Therapists have included 'joint protection' in their therapy with tates the use of a 'less deforming' position. Agnew5 carried

patients with arthritis since the publication of Cordery's arti- out an electromyographic pilot study recording the activity of

cle in 1965. 1 The principles she described aim to maintain extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU) in five normal subjects while per-

joint integrity and muscle strength, reduce pain and inflamma- forming tasks by a conventional method and when using a

tion in affected joints, and reduce fatlgue.i Many occupational gadget. She chose ECU because it is active in all wrist move-

therapy departments have taken these principles to form the ments and easy to locate for experimental study. She hypothe-

basis for educational programmes. sised that the use of gadgets for turning a key, turning a lock

Therapists at the Guest Hospital have used the principles and using scissors would lead to a reduction in the amount of

listed below in an attempt to relate Cordery's original alms- to force required to complete these tasks. The use of two of tne

activities of daily living: . gadgets did not result in the decreased muscle activity that

1. Avoid gripping too tightly was expected. No comparison was made of patient discom-

2. Balance your rest and activity fort or pain during activities. The results were inconclusive

3. Exercise little and often but, even if gadgets do enable a reduction in the ECU force

4. Watch your weight recruited for a given task, the implications for overall hand

5. Find easier work methods and organise your day use are unclear.

6. Avoid deforming positions Gripping too tightly leads to increased deformity: Corderyi

7. Be aware of posture and joint position at all times advised against strong grip, claiming that this would increase

8. Spread the strain over many joints or one large joint the strain on the collateral ligaments of the metacarpopha-

9. Wear your orthoses - hands and wrists langeal (MCP)joints. She cited the work of Smith et al6 in sup-

10. Listen to your body. port of this hypothesis. The idea that functional patterns of

This article provides an analysis of the evidence support- use exacerbate rheumatoid deformities has gained credence

ing each of these principles. A summary of the evidence over the years but the authors know of no controlled studies

found follows each analysis. that support this.

Gripping too tightly leads to increased joint destruction:

Castillo et al 7 demonstrated a close relationship between the

1. Avoid gripping too tightly degree of physical activity and the development of large cystic

This advice is based on the assumption that greater exertion erosions. Jayson et al8 were able to relate these cysts to

of grip force leads to: increased pain in the wrist and hand; increased intra-articular pressure. Corderyt claimed that pro-

increased deforming force at the soft tissues around the longed grip was contraindicated and that this also had an

joints; and increased joint destruction. effect on wear of the articular surface.

Gripping too tightly leads to increased pain: The pain expe- Summary: On the basis of the above studies, there is

rienced during grip may not be due solely to local inflamma- some evidence to suggest that gripping too tightly leads to

tion. Hart and Husklssons considered pain in rheumatoid increased pain and that it may increase joint destruction.

arthritis (RA) to be a complex of:

(a) Discomfort arising from peripheral inflamed joints 2. Balance your rest and activity

(b) Systemic illness The assumption behind this advice is that too much or too lit-

(c) Depression and anxiety tle of either is detrimental, but that both are important for the

(d) Overtones from drugs RA patient.

(e) Symptoms arising from complications such as peripheral It is felt that taking rest breaks during activity increases

or compression neuropathtes.s overall endurance and allows the person to keep energy in

How close is the correlation between grip force and pain reserve for enjoyable activities later. Furst et 81 9 were able to

experienced? Patients have reported that the provision of gad- show that RA patients can increase their total physical activity

gets can reduce the pain experienced when carrying out a through taking rest periods, with the aid of a workbook-

given activity.3.4 It is not clear if this is because less force is based programme designed to teach 'energy conservation

Philip Palmer, DipCOT, SROT, was formerly Senior Occupational Therapist at Guest Hospital, Dudley, and is now based at the Centre for Human

Communication, Oak Tree Lane Centre, Oak Tree Lane, Birmingham B29 6JA.

Jane Simons, DipCOT, SROT, was formerly Acting Head Occupational Therapist, Sub-Regional Rheumatology Unit, Guest Hospital, Dudley, and is

now working in Ontario, Canada. Address for correspondence: 103 Marlborough Avenue, Kitchener, Ontario NZM 1H7, Canada.

British Journal of Occupational Therapy, December 1991, 54(12) 453

Downloaded from bjo.sagepub.com at East Carolina University on June 5, 2016

behaviours'. Smith and Polley,10 in a review, also suggested Summary: There is some evidence to suggest that too

that there should be a balance between exercise and sys- much exercise can damage the joints and that short periods

temic and articular rest. Tromblyu suggested that patients of isometric exercise can increase muscle strength in the RA

should be encouraged to rest prior to fatigue to avoid a long patient. There is no proof that exercise can prevent the occur-

recuperative period. rence of deformity.

There are case studies which suggest that enforced inac-

tivity following hemiplegia, polio and peripheral nerve lesions

might have inhibited joint destruction in patients who subse- 4. Watch your weight

quently developed rheumatoid arthritis. 12·14 Mills et al,15 how- This advice is based on the assumption that excess weight

ever, were unable to demonstrate a substantial difference places unnecessary strain on load-bearing joints, increasing

between one group of inpatients at rest and another group pain during, for example, transfers and walking, and increas-

allowed activity. Alexander et al 16 suggested that the benefits ing the likelihood of joint damage.

of bedrest were less than expected and recommended careful In the quiescent phase of the disease, RA patients have

selection of patients. This view was supported by Lee et al,17 reported that joint pain is more severe during loading of that

Various authors have given specific advice on rest and joint than at rest. Therefore, an increased load (through obesi-

prone lying. Melvin18 advised patients to rest 10-12 hours out ty) should perhaps be expected to increase the pain experi-

of 24, including a 1-2 hour nap in the afternoon, to allow the enced.

body's restorative processes to help combat disease. She There is no proof that increased loading of joints has a

encouraged prone lying to reduce the risk of contractures.ie .Iong-term detrimental effect on joints diseased by RA. There

It is generally agreed that keeping active facilitates joint is also some doubt about the relationship between

mobility and muscle strength, and too much activity may osteoarthritis (OA) and obesity, although Van Saase et al 23

result in fatigue, increased pain and stress to the joints. were able to demonstrate a positive correlation between knee

Oordery- and Melvin18 advised patients to reduce their activity OA and obesity. However, they were unable to conclude that

if pain persisted for more than one hour afterwards. this reflected a true causal relationship.

Summary: There is some evidence to suggest that balanc- Summary: No firm evidence has been found to support the

ing rest with activity can increase overall endurance and inhib- advice that patients should 'weight-watch'. However, weight

it joint destruction. There is some very specific advice in the control seems sensible with regard to general health and

literature on the amount of rest required. However, there has mobility and is, therefore, encouraged by the authors.

been no study done to support the view that there is a specif-

ic period of rest that is the most beneficial to all RA patients.

The needs of each patient are likely to vary. 5. Find easier work methods and

organise your day

Therapists may be involved in supplying gadgets and giving

3. Exercise little and often advice on alternative methods of carrying out ADL tasks. Is

It is generally agreed that short periods of non-resisted exer- there any evidence that patients benefit from this interven-

cise at the correct time can be beneficial to the RA patient. tion?

This assumes that too much exercise at one time, or during It is thought that the occupational therapist can facilitate

the acute phase, can be detrimental. Trornblyn suggested the the patient's independence in ADL directly through analysing

use of exercise to maintain muscle power in order to help exactly what the problem is and why it is occurring.

maintain joint integrity and alignment, and to maintain or Introduction of the right gadget at the appropriate time may

improve the joint range of movement. Too much exercise may improve independence. Some attempts have been made at

lead to fatigue, joint strain and soft tissue damage, and correlating appropriate gadgets, for example, food preparation

inflammation. Too little exercise may lead to joint stiffness, aids, with patterns of disability and with the degree of pain

risk of contractures, and muscle wasting. experienced in their use. 3,4 Thus, certain gadgets have been

It may not be possible to give instructions on the amount shown to be useful.

of exercise necessary for the RA patient. This will vary Some attempts have also been made at assisting the

between patients because it is usually guided by the amount patient in ADL organisation. Furst et al9 used a new pro-

necessary to bring on fatigue. corcerv- and Melvin18 recom- gramme based on a workbook which emphasised developing

mended that pain or discomfort should not last for more than behavioural awareness and problem-solving skills, enabling

one hour following exercise. patients to make decisions when difficulties arose later.

There has been some discussion on the most beneficial Patients were asked to 'analyse activities according to

form of exercise for the RA patient. Studies have shown that potential energy use' and were given 'training in how to recog-

as few as three isometric contractions per day can significant- nise those activities that may cause pain and/or fatigue and

ly increase muscle strength in RA subjects. 20.21 Isometric how to modify them'. Furst et al9 termed this 'energy conser-

exercise is recommended because it is less painful, in addi- vation' and claimed that, through the use of this programme,

tion to passive or gentle assisted exercise, during the acute patients increased their amount of physically active time and

phase. 2o It has been' suggested that resisted exercises achieved a better balance of rest and physical activity.

should be avoided because they may be deforming due to the Summary: Patients have reported that some gadgets and

alteration of the relationships of tendons to axes of move- advice make their tasks easier. There is evidence that more

rnent.n Castillo et al7 provided some evidence to suggest that intense therapeutic intervention, through 'energy conserva-

'physical activity can lead to joint damage. tion',may be of benefit to the patient.

Patients may benefit from different forms of exercise at

each phase of the disease process. Tromblyu suggested that

as the disease activity subsides, patients should be encour- 6. Avoid deforming positions

aged to increase their active exercises for short periods, with- Patients are taught to avoid placing their joints into positions

in pain limits and balanced with rest. Melvin22 discussed the which are thought to exacerbate the development of deformi-

basic principles of exercise without attempting to describe an ties. corderyi publicised the idea that external and internal

exercise regime which could be generally applied. stresses and their direction influenced the development of

454 British Journal of Occupational Therapy, December 1991, 54(12)

Downloaded from bjo.sagepub.com at East Carolina University on June 5, 2016

deformities in joints. Her advice to minimise these potentially Therapists encourage patients to be aware of posture during

deforming forces in the hands was as follows.t rest, sitting and standing. General advice on maintaining a

(a) Maintain range of movement of shoulder, elbow, forearm good posture during activities is well documented. ll,18,19 No

and wrist because hand function depends on these joints research specifically on posture to support the benefits of

(b) Maintain coordination and balance of intrinsic and extrinsic this advice was found.

muscles

(c) Avoid strain on the collateral ligaments by enlarging the

handles of objects 8. Spread the strain over many joints

(d) Avoid ulnar pressure at the MCP joints; avoid lateral pres- or one large joint

sure at interphalangeal joints; and avoid abduction of the Corderyi emphasised the 'use of the strongest joints avail-

thumb phalanges. able for the job'. Large joints are protected by stronger mus-

The efficacy of these measures in the prevention of cles than the smaller joints. The assumption is that a reduc-

rheumatoid deformities will depend on the causative factors tion in strain will:

involved. Ulnar drift is one of the most common deformities of (a) Reduce pain experienced during the activity

the rheumatoid hand and is therefore singled out for analysis (b) Reducejoint damage over the longer term.

in this section. The level of patient pain/discomfort will determine the suc-

Smith et al6,24 implicated the role of the long flexors in cess of this instruction in the short term. If the patient does

ulnar drift deformity and volar subluxation of the MCP joint not experience significant pain, he/she may be unaware of

and advocated that flexion at this joint during activity should the need to reduce the loading. However, from studies done

be minimised by splinting to reduce deforming forces. They on the use of gadgets there is some evidence to support the

also advocated working splints to inhibit ulnar deviation. idea that spreading the strain does reduce pain experienced

However, Shapir0 25 was able to show that loss of carpal sta- during activity.3,4

bility could lead to radio-metacarpal shift and assumed this to In the absence of pain, patient compliance to this principle

be a causative factor in the development of ulnar drift, the may still be worth attaining if evidence can be found that joint

implication being that the fingers need to move ulnarward in a stress leads to joint damage in the long term. There are sev-

compensatory way to maintain hand function. Support for this eral studies relating handedness to joint erosions. Mody et

view is provided by a study from Pahle and Raunio.26 a136 studied 256 patients and found significantly greater radio-

Taleisnik27 and Wise28 implicated radial/ulnar variations in logical changes in the dominant hand, especially in the middle

intrinsic muscle attachments as causative of ulnar drift. and index fingers. They postutated that the severe involve-

Hakstian and Tubiana29 implicated the MCP joint structure ment of these fingers might be related to their greater use in

and radial/ulnar variations in collateral ligaments. daily activities. Owsianik et al37 demonstrated significantly

All the studies outlined above have used many suojects, greater joint destruction in the dominant hand; this difference

with observation and measurement from in-vitro studies, was seen in all joints, especially the wrists, but with the

cadaverous hands or x-ray examination. By contrast, evidence' exception of the MCPjoint of the thumb.

for the role of functional patterns of use has been largely Summary: There is some evidence that spreading. the

anecdotal. Lush,3o Fearnley31 and Flatt32 postulated a role for strain leads to a reduction in pain experienced during certain

the effects of gravity, disturbed function and pressure of activities. There is also some evidence to suggest that

usage but provided no evidence for this. Vainio and Oka33 increased joint stress in the hand can lead to increased dam-

studied the MCP joints of 292 patients and found double the age in selected joints.37 However, this assumes that the domi-

commonality of ulnar drift in females. They postulated two rea- nant hand is more stressed than the non-dominant hand; if

sons: this is the case, why is the thumb comparatively spared given

(a) There is more delicate bone structure in females its major role during hand function?

(b) Females are often obliged to go on with household work

during the active stage whereas men have more opportuni-

ty for rest. 33 9. Wear your orthoses - hands and

Ellison et al34 postulated that children were least affected wrists

since they had no domestic or economic obligations.

The wearing of orthoses is thought to assist the RA patient in

Hasselkus et al35 attempted to test the concept that joint

the followingways: protection, support, rest and prevention of

stress during daily activity resulted in deformity, by looking at

deformity.

differences in deformities between dominant and non-domi-

Protection: It is thought that MCP joint synovitis may lead

nant hands. They hypothesised that the dominant hand was

to laxity of the capsule and ligaments, encouraging the forma-

subjected to greater stress during daily activities and that this

tion of deformities. Therefore, if therapists protect the joint

would be reflected in their findings. Instead, they found no sig-

structures through splinting during exacerbations, they may be

nificant difference in the incidence of rheumatoid deformities

helping to prolong joint integrity, for example, by rest

between the hands.35 Mody et al36 confirmed the result.

orthoses. Spinner and Keplan38 suggested the early use of

Summary: Many factors have been implicated in the devel-

wrist supports to protect ECU and therefore the stability of

opment of ulnar drift. It is therefore unclear whether or not

the wrist.

there is a single main determining factor. It remains unproven

Support: Patients have reported a reduction in hand func-

that functional patterns of use lead to deformity at the MCP

tion as a result of wrist pain. When the wrist is supported in

joints.

an orthosis, pain is reduced and hand function improves.

Rest: It is thought that joint motion aggravates inflamma-

tion and increases pain. Therefore, to immobilise the joint in a

7. Be aware of posture and joint splint should reduce stress to the capsule and ligaments,

position at all times allow the muscles to relax, eliminate pain with motion and

Tromblyll suggested that patients should be encouraged to reduce inflammation. Partridge and Duthie39 and Gault and

'use each joint in its most stable, anatomical and functional Spyker40 have produced evidence to support this.

plane' and use 'correct patterns of motion' in order to min- Prevention or correction of deformity: Splintage has been

imise pain and protect joints against deforming forces. used to correct or minimise joint contractu res through gentle

British Journal of Occupational Therapy, December 1991, 54(12) 455

Downloaded from bjo.sagepub.com at East Carolina University on June 5, 2016

passive stretching, though no study to show that this is effec- required in all aspects of joint protection. (A summary of the

tive was found. findings is provided in Table 1.) The authors suggest the fol-

Splintage has been used in the management of ulnar drift. lowing items as worthy of further study:

Pahle and Rauni0 26 found evidence to suggest that splinting (a) The relationship between functional patterns of use and

the wrist in ulnar deviation can reduce or eliminate radial devi- rheumatoid deformities

ation as a contributing factor to ulnar drifting of the fingers, (b) Can exercise influence the progression of deformities?

the 'Zig-zag deformity'. (c) Does joint stress lead to joint damage in the long term?

Splintage has been used in the management of MCP joint (d) How effective are orthoses in the prevention of deformi-

subluxation. An ulnar cuff orthosis may be used in an attempt ties?

to minimise the damaging influence of the long finger flexors

Table 1. Summary of findings

on the MCP joints during grasp.> It is suggested that the use

of this orthosis may also discourage the development of fin- No firm

Evidence to Evidence to evidence

ger swan-necking in some patients, by stretching the intrinsics Principle support disclaim found

and encouraging proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint flexion

with the MCP joints blocked in extension, although there is no 1. Avoid gripping too tightly .I

2. Balance rest and activity .I

evidence to support the efficacy of this. 3. Exercise little and often .I

Summary: There is no study to confirm the benefits of 4. Watch your weight .I

wrist supports as reported by patients. No evidence has been 5. Find easier work methods

found to support the view that orthoses are effective in pro- and organise your day .I

6. Avoid deforming positions .I

tection of joints. Studies have indicated that resting joints in 7. Be aware of posture and

orthoses may be effective in reducing inflammation, and joint position at all

patients have reported that they are useful in reducing pain times .I

experienced. 8. Spread the strain over

Pahle and Rauni0 26 have shown how splinting the wrist can many joints or one large

joint .I

influence the progression of ulnar drift in some patients, but 9. Wear your orthoses .I

there is no study on the application of splintage for preventing 10. Listen to your body .I .I .I

other types of deformity.

There is no detailed research on the long-term benefits of

The review has examined the basic principles of joint pro-

splintage, although Karten et al41 suggested that splinting is

tection. However, there are wider issues worthy of discussion,

unlikely to prevent hand deformities if synovitis persists.

and the following questions need to be raised:

- Is it possible to teach joint protection?

10. Listen to your body - Is it necessary to teach it?

Patients are encouraged to be aware of the sensation of pain - Are there more effective ways of influencing disease pro-

as a guide to overuse of the joint (that is, pain avoidance) and gression?

as an indication of joint inflammation necessitating rest. The Patient education groups are widely used in the treatment

degree of pain experienced and the levels of inflammation of arthritis, but there is conflicting evidence about their effec-

present may not be closely correlated because pain is a sub- tiveness.

jectiveexperience influenced by many other factors - psy- There are studies of these groups which indicate that

chological, cultural and emotional.42 Therefore, it has been patient knowledge about the disease does improve44-46.50.51

suggested that therapists should treat pain with reference to and also claiming effectiveness in gaining compllance-e and

a behavioural model rather than in a purely physiological self-reported behaviour change. Furst et al9 claimed to have

way. 2,43 effected significant behavioural change through teaching ener-

Encouraging awareness of joint sensation may influence gy conservation techniques with only six sessions lasting 1 1/ 2

the pain threshold. Parker et al,44 in a study of a joint protec- hours each plus home tasks. Lorig et al,46 in a self-help edu-

tion patient education group, found an increase in pain experi- cational programme taught by laypersons, claimed that sub-

enced by this group when compared with a control group. jects exceeded controls in recommended behaviours at 4

Another study of a similar patient education group found no months after the programme, and that these changes

effect on patient pain.45 Lorig et al46 claimed that patient pain remained significant at 20 months.

in their education group had decreased compared with con- There are studies which indicate that educational groups

trols. Others have claimed similar results on reducing pain have been less effective in reaching their objectives. Cohen et

using group work with various behavioural training pro- al45 compared the relative effectiveness of a patient educa-

grammes.47,48 tion course led by laypersons and a similar course· using

Huskisson and Hart49 found a significantly higher pain health professionals and found that neither was any more

threshold in patients suffering from ankylosing spondylitis effective than non-intervention in improving health behaviour

(AS) compared with RA patients. They postulated as a possi- beyond that of exercise. Hammond52 analysed behaviour fol-

ble explanation •.., the different attitude transmitted by the lowing joint protection education and discovered an obvious

physician to the patient with this disease. They [AS patients] discrepancy between observed and self-perceived joint care

are encouraged to lead normal lives, remain mobile, and take behaviour. She suggested that education leads to attitudinal

up rather than give up. The patient with RA is encouraged to change but behavioural change may require longer and more

rest and protect his joints. '49 targeted input. 52 Before it is possible to evaluate if education

Summary: It is not proven that 'listening to your body' is is effective, there is a need to establish that behavioural

beneficial to the RA patient. There are some studies which change has actually taken place.

suggest that the therapist's intervention may even be detri- Is it necessary to teach 'joint protection'? Callahan and

mental. Pincus53 may have provided a rationale for patient education

(in the widest sense) for the individual with RA. They studied

385 patients and found the poorest results in patients of a

Discussion lower formal education level, and progressively better results

This literature review has shown that further research is in those with a high school education, high school graduates,

456 British Journal of Occupational Therapy, December 1991, 54(12)

Downloaded from bjo.sagepub.com at East Carolina University on June 5, 2016

and those with some college education, but no differences in 8. Jayson MIV, Rubenstein D, St J Dixon A. Intra-articular pressure

those who had attended college or graduated or were post- and rheumatoid geodes (bone cysts). Ann Rheum Dis 1970 29:

496-506.

graduates.53 If this finding is reproducible in the UK, it has

9. Furst GP, Gerber LH, Smith CC, Fisher S, Shulman B. A pro-

implications for the teaching of joint protection techniques; it gramme for improving energy conservation behaviours in adults

suggests a need for more teaching input for low academic with RA. Am J Occup Ther 1987; 41(2): 102-11.

achievers, if only because these are the patients who are like- 10. Smith RD, Polley HF. Rest therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Mayo

ly to be the most severely affected by the disease. ci» Proc 1978; 53: 141-45.

11. Trombly CA. Occupational therapy for physical dysfunction. 2nd

The present approach to joint protection at the Guest ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1983.

Hospital is rather mechanistic: patients are told that if they 12. Kamermann JS. Protective effect of traumatic lesions on RA. Ann

follow the above principles (1-10) it will help to minimise the Rheum Dis 1966; 25: 361-63.

effects of the disease on their bodies. However, this mecha- 13. Bland JH, Eddy WM. Hemiplegia and rheumatoid hemiarthritis.

Arth Rheum 1968; 11: 72-78.

nistic and rather physiologically based approach may not be

14. Glick EN. Asymmetrical rheumatoid arthritis after poliomyelitis.

the best way to prevent disability. There is mounting evidence Br Med J 1967; 3: 26-29.

that the major determinants of disability progression are not 15. Mills JA, Pinals RS, Ropes RW, et al. Value of bedrest in patients

physical but psychological. 54-60 with RA. N Engl J Med 1971; 284: 453-58.

McFarlane and Brooks54,55 have shown that psychological 16. Alexander GJ, Hortas C. Bacon PA. Bedrest, activity and the

inflammation of rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol 1983; 22:

factors predict more of the variance of disability than disease 134-40.

activity. These factors are associated with the tendency to 17. Lee P, Kennedy AC, Anderson J, et al. Benefits of hospitalisation

deny the emotional dilemmas caused by having a chronic ill- in rheumatoid arthritis. Quart J Med 1974; 43: 205-14.

ness, difficulty in accepting doctors' reassurances and clinical 18. Melvin JL. Joint protection and energy conservation instruction.

Rheumatic disease - occupational therapy and rehabilitation. 2nd

depression. McFarlane and Brooks55 showed few significant

ed. Philadelphia: F A Davis, 1982: 351-71.

relationships between duration of illness, disease severity 19. Melvin JL. Positioning and lying prone. Rheumatic disease - occu-

and the psychological measures, but a strong correlation pational therapy and rehabilitation. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: F A

between disability and attitude to illness. Hawley and Wolfe56 Davis. 1982: 393-71. .

showed that the development of depression in RA was associ- 20. Machover S, Sapecky AJ. Effect of isometric exercise on the

quadriceps muscle in patients with RA. Arch Phys Med Rehabil

ated with socioeconomic and not clinical factors, and disease 1966; Nov: 737-41.

activity appeared to have a limited effect on psychological sta- 21. Liverson WT, Asa MM. Further studies of brief isometric exercis-

tus. Frank et al57 showed a significant relationship between es. Arch Phys Med Rehabil1959; Aug: 330-36.

the presence or history of depression and higher levels of 22. Melvin JL. Exercise treatment. Rheumatic disease - occupational

therapy and rehabilitation. 2nd. ed, Philadelphia: F A Davis,

pain. They too found no significant relationship between cur-

1982: 383-91.

rent depression and common indicators of RA activity. 23. Van Saase JLCM, Vanderbrouckle JP, Van Romunde LKJ.

The recent studies referred to above pose a question Valkenburg HA. Osteoarthritis and obesity in the general popula-

which occupational therapists working in rheumatology cannot tion, a relationship calling for an explanation. J Rheumato/1988;

afford to ignore. If the ultimate goal is to reduce disability, 15(7): 1152-58.

24. Smith EM, Juvinall RC, Bender LF, Pearson JR. Flexor forces and

should therapists now be adopting a more psychodynamic rheumatoid metacarpophalangeal deformity. J Am Med Assoc

approach? 1966; 198(2): 130-34.

25. Shapiro JS. Wrist involvement in rheumatoid swan neck deformi·

ty. J Hand Surg 1982; 7: 484.

Conclusion 26. Pahle JA, Raunio P. The influence of wrist position on finger devi·

ation in the rheumatoid hand. Clinical and radiological study. J

Patients with RA will always have problems with completing

Bone Joint Surg 1969; 51-8: 664-76.

their ADL tasks, so the need for occupational therapists to 27. Taleisnik J. Mechanism of wrist deformity in rheumatoid arthritis.

assess these problems and provide appropriate advice and The wrist. London: Churchill. 1985: 357-63.

gadgets will remain a priority. Many therapists working in 28. Wise KS. The anatomy of the metacarpophalangeal joints. with

rheumatology spend some time teaching joint protection in an observations of the aetiology of ulnar drift. J Bone Joint Surg

1975; 57-8(4): 485-90.

attempt to influence disease progression. Mounting evidence 29. Hakstian RW. Tubiana R. Ulnar deviation of the fingers. The role

for the importance of psychological factors for disease pro- of joint structure and function. J Bone Joint Surg 1967; 49: 299.

gression suggests that therapists may need a new hypothesis 30. Lush B. Ulnar deviation of the fingers. Ann Rheum Dis 1952; 11:

to provide a rationale for a different approach to disease- 219-21.

31. Fearnley GR. Ulnar deviation of the fingers. Ann Rheum Dis

modifying therapy. This new approach may involve an attempt

1951; 10: 126-36.

to influence more directly the psychological factors shown to 32. Flatt AE. Some pathomechanics of ulnar drift. Plast Reconstr

be most disabling to the RA patient. Surg 1966: 37: 295-303.

33. Vainio K. Oka M. Ulnar deviation of the fingers. Ao1n Rheum Dis

References 1953; 12: 122-24.

34. Ellison MR. Flatt AE, Kelly KJ. Ulnar drift of the fingers in rheuma-

1. Cordery JC. Joint protection: a responsibility of the occupational

toid disaese. J Bone Joint Surg 1971; 53-A: 1061-82.

therapist. Am J Occup Ther 1965; 19: 285-94.

35. Hasselkus BR, Kshepakaran KK, Safrit MJ. Handedness and

2. Hart FD, Huskisson EC. Pain patterns in the rheumatic disorders.

hand joint changes in RA. Am J Occup Ther 1981; 35(11): 705-

Br Med J 1972; 4: 213-16.

10 .

.3. Bradshaw ESR. Food preparation aids for rheumatoid arthritis

36. Mody GM, Meyers OL, Reinach SG. Handedness and deformities,

patients. Screw top jar and bottle openers, can openers, veg-

radiographic changes, and function of the hand in RA. Ann

etable peelers, stabilisers. DHSS Aids Assessment Programme.

Rheum Dis 1989; 48: 104-107.

London: DHSS, 1982.

37. Owsianik WDJ, Kundi A, Whitehead IN, Kraag GR, Goldsmith C.

4. Bradshaw ESR. Assessment of cooking utensils for RA patients.

Radiological articular involvement in the dominant hand in RA.

Saucepans, cooking baskets and steamers. DHSS Disability

Ann Rheum Dis 1980; 39: 508-510.

Equipment Assessment Programme. London: DHSS, 1986.

38. Spinner M. Keplan EB. Extensor carpi ulnaris: its relationship to

5. Agnew PJ. Joint protection in arthritis: fact or fiction? Br J Occup

the stability of the distal radio-ulnar joint. cun ortnoo ReI Res

Tber 1987; 50(7); 227-30.

1970; 68: 124-29.

6. Smith EM. Juvinall RC. Bender LF. Pearson JR. Role of the finger

39. Partridge REH, Duthie JJK. Controlled trial of the effect of com-

flexors in rheumatoid deformities of the metacarpophalangeal

plete immobilisation of the joints in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann

joints. Arth Rheum 1964; 7(5): 467-80.

Rheum Dis 1963; 22: 91-99.

7. Castillo BA. EI Sallab RA, Scott JT. Physical activity, cystic ero-

40. Gault SJ, Spyker JM. Beneficial effect of immobilisation of joints

sions and osteoporosis in RA. Ann Rheum Dis 1965; 24: 522-

in rheumatoid and related arthritides: a splint study using

27.

BritiSh Journal of Occupational Therapy, December 1991, 54(12) 457

Downloaded from bjo.sagepub.com at East Carolina University on June 5, 2016

sequential analysis. Arth Rheum 1969; 12: 34-44. 51. Spiegel TM. Knutzen KL, Spiegel JS. Evaluation of an inpatient

41. Karten I. Lee M. McEwen C. Rheumatoid arthritis: five year study RA patient education program. Clin Rheumatol 1987; 6(3): 412-

of rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil1973; 54: 120-28. 16.

42. Charter RA. Nehemkis AM. Keenan MA. Person 0, Prete PE. The 52. Hammond A. Joint protection behaviour of patients with RA fol-

nature of arthritis pain. Br J Rheumato/1985; 24: 53-60. lowing an education programme. Southampton: Department of

43. Pither CEo Treatment of persistent pain. Br Med J 1989; 299: Rehabilitation Studies, University of Southampton. 1988.

1239. 53. Callahan LF. Pincus T. Formal education level as a significant

44. Parker JC, Singsen BH. Hewett JE. et at. Educating patients with marker of clinical status in RA. Arth Rheum 1988; 31: 1346-57.

rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective analysis. Arch Phys Med 54. McFarlane AC. Brooks PM. Determinants of disability in rheuma-

Rehabil1984; 65: 771-74. toid arthritis. Br J Rheumato/1988; 27: 7-14.

45. Cohen JL. Sauter SV, De Vellis RF, De Vellis BM. Evaluation of 55. McFarlane AC. Brooks PM. An analysis of the relationship

arthritis self-management courses led by laypersons and by pro- between psychological morbidity and disease actiVity in rheuma-

fessionals. Arth Rheum 1986: 29: 388-93. toid arthritis. J Rheumato/1988; 15(6): 926-31.

46. Lorig K, Lubeck 0, Kraines RG. Seleznick M, Holman HR. 56. Hawley OJ. Wolfe F. Anxiety and depression in patients with

Outcomes of self-help education for patients with arthritis. Arth rheumatoid arthritis. A prospective study of 400 patients. J

Rheum 1985; 28(6): 680-85. Rheumato/1988; 15(6): 932-41.

47. Parker JC, Frank RG. Beck NC. et at, Pain management in 57. Frank RG, Beck NC. Parker JC. et al, Depression in rheumatoid

rheumatoid arthritis patients. A cognitive-behavioural approach. arthritis. J Rheumato/1988; 15(6): 920-25.

Arth Rheum 1988; 31(5): 593-601. 58. Hagglund KJ. Haley WE. Reveille JD. Alarcom GS. Predicting indi-

48. McDaniel LK. Anderson KO. Bradley LA. et al. An observation vidual differences in pain and functional impairment among

method for assessing pain behaviour in RA patients. Reliability patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arth Rheum 1989; 32(7):

and validity. Pain 1986; 24(2): 165-84. 851-58.

49. Huskisson EC, Hart FD. Pain threshold and arthritis. Br Med J 59. Keefe FJ. Brown GK. Wallston KA. Caldwell OS. Coping with

1972; 28 Oct: 193-95. rheumatoid arthritis pain: catastrophismg as a maladaptive strat-

50. Potts M, Brandt KT. Analysis of education support groups for egy. Pain 1989; 37(1): 51-56.

patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Patient Couns Health Educ 60. Crosby U. Stress factors, emotional stress and rheumatoid

1983; 4(3). arthritis disease activity. J Adv Nurs 1988; 13(4): 452-61.

Equipment Review: Adapted Tricycle

Children with cerebral palsy benefit in many ways from the gram). A forward support attached to the saddle provides

ability to be mobile'! It gives them the freedom to explore adjustable anterior and lateral trunk control. A Velcro strap

their environment as well as the opportunity to initiate interac- across the back provides additional security. The anterior

tion with their peers on an equal basis. Independent mobility chest support encourages the trunk weight forwards over the

can be achieved by self-propulsion (crawling, walking, cycling, sitting base and shoulder girdle protraction which allows the

self-propelling wheelchair) or by powered mobility (power arms to come to a forward prop position. Straight handlebars

chair). The former method has the advantage of mobility com- facilitate this position and maintenance of hand grasp. Wrist

bined with active exercise for the child. Many children with supports, footplates and footstraps can be added as appropri-

severe cerebral palsy are unable to walk without assistance ate.

and even with assistance have difficulty achieving a good It is recommended that a cycle safety helmet is worn at all

walking pattern. A tricycle allowing self-propulsion and a good times when the child is cycling.

movement pattern can provide an alternative solution. Catharine Mulcahy. Research Occupational Therapist.

At Chailey Heritage Rehabilitation and Development Teresa Pountney, Research Physiotherapist.

Centre, special adaptations have been made to standard Geoffrey Billington. Medical Technical Officer,

Pashley Pickle and Polo trikes to allow children with severe Chailey Heritage. Rehabilitation and Development Centre,

cerebral palsy to cycle independently. The posture induced on North Chailey, Nr Lewes, East Sussex BNB 4EF.

the trike compares closely to postures achieved with other

types of saddle seating. 2 .3 and carries through the therapeutic Acknowledgements

benefits of this posture with mobility. This Item of equipment was developed in the Rehabilitation

Engineering Unit, Chailey Heritage. as part of a project developing a

The standard saddle is replaced with a special Evazote

total postural management approach for children with cerebral palsy.

saddle, shaped to allow the ischial tuberosities to rest on a The authors are grateful to Action Research for funding this project

flat surface with a narrow raised wedge anteriorly (see dia- and to Mark Edmondson-Shawfor the drawing shown.

A similar review was published in Physio-

therapy 1991; 77(10): 660.

References

1. Trefler E. Marcrum J. Trends in powered

mobility for school aged physically handi-

capped children. Proceedings RESNA 10th

Annual Conference. San Jose. California:

RESNA 1987.

2. Stewart PC. McQuilton G. Straddle seating

for the cerebral palsied child. Physio-

therapy 1987: 73(4): 204-206.

3. Pope PM. Booth E. Gosling G. The devel-

opment of alternative seating and mobility

systems. Physiotherapy Pract 1988; 4: 78-

93.

458 BritiSh Journal of Occupational Therapy. December 1991. 54(12)

Downloaded from bjo.sagepub.com at East Carolina University on June 5, 2016

You might also like

- PL - 840.1 - Joint Protection Techniques For Hand - Finger ArthritisDocument5 pagesPL - 840.1 - Joint Protection Techniques For Hand - Finger ArthritisXouya SuizenNo ratings yet

- MCQ Review 2Document76 pagesMCQ Review 2Kholoud Almaabdi0% (1)

- The Pocketbook For PHYSIOTHERAPISTS 2nd Gitesh Amrohit Masud PDFDocument408 pagesThe Pocketbook For PHYSIOTHERAPISTS 2nd Gitesh Amrohit Masud PDFemil100% (1)

- Effect of Physiotherapy Treatment On Frozen ShoulderDocument6 pagesEffect of Physiotherapy Treatment On Frozen Shoulderalfi putri bahriNo ratings yet

- Alderman ProlotherapyforMusculoskeletalPainPPM 2007Document7 pagesAlderman ProlotherapyforMusculoskeletalPainPPM 2007Zuhri RomiNo ratings yet

- 4.3 Alderman ProlotherapyforMusculoskeletalPainPPM 2007Document7 pages4.3 Alderman ProlotherapyforMusculoskeletalPainPPM 2007Khushboo IkramNo ratings yet

- Exercise For Older AdultsDocument8 pagesExercise For Older AdultsTengku EltrikanawatiNo ratings yet

- Tendon Neuroplastic TrainingDocument9 pagesTendon Neuroplastic TrainingLara VitorNo ratings yet

- Physiotherapy: J o U R N A L o FDocument16 pagesPhysiotherapy: J o U R N A L o FJulenda CintarinovaNo ratings yet

- Effect of Physiotherapy Treatment On Frozen ShouldDocument6 pagesEffect of Physiotherapy Treatment On Frozen ShouldHarshita bansalNo ratings yet

- (2023 - Dhillon) Ankle Sprain and CaiDocument11 pages(2023 - Dhillon) Ankle Sprain and CaiIan ZarceroNo ratings yet

- Short-Term Effects of Strain Counterstrain in Reducing Pain in Upper Trapezius Tender PointsDocument9 pagesShort-Term Effects of Strain Counterstrain in Reducing Pain in Upper Trapezius Tender PointsKatrien BalNo ratings yet

- 291-297 Jopct1Document7 pages291-297 Jopct1efi hudriahNo ratings yet

- Clinical App Worksheet-Elbow-Wr-Hand 1Document5 pagesClinical App Worksheet-Elbow-Wr-Hand 1api-669451419No ratings yet

- Tendon Neuroplastic Training Changing The Way We Think About Tendon RehabilitationDocument8 pagesTendon Neuroplastic Training Changing The Way We Think About Tendon RehabilitationfilipecorsairNo ratings yet

- 209 FullDocument23 pages209 FullMarta MontesinosNo ratings yet

- Indeks WomaxDocument7 pagesIndeks WomaxRizalNo ratings yet

- Abhijit Dand GeetanjaliDocument8 pagesAbhijit Dand GeetanjalijunedyNo ratings yet

- PhysicalTreatments v4n1p25 en PDFDocument9 pagesPhysicalTreatments v4n1p25 en PDFFadma PutriNo ratings yet

- Tendon Neuroplastic TrainingDocument8 pagesTendon Neuroplastic TrainingFrantzesco KangarisNo ratings yet

- A Comparative Study To Find Out The Effects of Capsular Stretching Over Muscle Energy Technique in The Management of Frozen ShoulderDocument50 pagesA Comparative Study To Find Out The Effects of Capsular Stretching Over Muscle Energy Technique in The Management of Frozen ShoulderjojiNo ratings yet

- To Study The Effects of Muscle Energy Technique With Conventional Treatment Along With Cellular Nutrition in Patients With Knee OsteoarthritisDocument5 pagesTo Study The Effects of Muscle Energy Technique With Conventional Treatment Along With Cellular Nutrition in Patients With Knee OsteoarthritisZickey MaryaNo ratings yet

- 0 No Muscular Limit StretchingDocument5 pages0 No Muscular Limit StretchingGeraldi ContrerasNo ratings yet

- Clinical App Worksheet Knee Foot AnkleDocument8 pagesClinical App Worksheet Knee Foot Ankleapi-676469437No ratings yet

- Management of Osteoarthritis of The Knee in The Active PatientDocument11 pagesManagement of Osteoarthritis of The Knee in The Active PatientAmalia RosaNo ratings yet

- Low Back PainDocument9 pagesLow Back PaintamiNo ratings yet

- Scapular Muscle Rehabilitation Exercises in Overhead Athletes With Impingement SymptomsDocument10 pagesScapular Muscle Rehabilitation Exercises in Overhead Athletes With Impingement SymptomsTheologos PardalidisNo ratings yet

- Heavy-Load Eccentric Calf Muscle Training For The Treatment of Chronic Achilles TendinosisDocument8 pagesHeavy-Load Eccentric Calf Muscle Training For The Treatment of Chronic Achilles TendinosisburgoschileNo ratings yet

- Pubalgia 1Document11 pagesPubalgia 1Carlos Alberto Mac-kay VillagranNo ratings yet

- Effect of Graded Plank Protocol On Core Stability in Sedentary DentistsDocument5 pagesEffect of Graded Plank Protocol On Core Stability in Sedentary DentistsVizaNo ratings yet

- The Evolution of Eccentric Training As Treatment For Patellar Tendinopathy (Jumper's Knee) : A Critical Review of Exercise ProgrammesDocument7 pagesThe Evolution of Eccentric Training As Treatment For Patellar Tendinopathy (Jumper's Knee) : A Critical Review of Exercise ProgrammesCarlos Ismael EspinozaNo ratings yet

- Pas Chos 2013Document6 pagesPas Chos 2013Hari25885No ratings yet

- Pain and Effusion and Quadriceps Activation and StrengthDocument6 pagesPain and Effusion and Quadriceps Activation and StrengthЯнь НгуенNo ratings yet

- Eccentric or Concentric Exercises For The Treatment of TendinopathiesDocument11 pagesEccentric or Concentric Exercises For The Treatment of TendinopathiesAnonymous xvlg4m5xLXNo ratings yet

- PTJ 1275Document12 pagesPTJ 1275Taynah LopesNo ratings yet

- Individual Distribution of Muscle Hypertrophy Among Hamstring Muscle Heads - Adding Muscle Volume Where You Need Is Not So SimpleDocument10 pagesIndividual Distribution of Muscle Hypertrophy Among Hamstring Muscle Heads - Adding Muscle Volume Where You Need Is Not So SimpleSandro LemosNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of A 12 Week Exercise Programme in Hip Osteoarthritis A Randomised Controlled TrialDocument6 pagesThe Effectiveness of A 12 Week Exercise Programme in Hip Osteoarthritis A Randomised Controlled TrialHerald Scholarly Open AccessNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Sprain DiscolationDocument7 pagesJurnal Sprain DiscolationMuhammad IrfanNo ratings yet

- Schuster Case Report2 Draft 4 - Brief For PortfolioDocument47 pagesSchuster Case Report2 Draft 4 - Brief For Portfolioapi-528037163No ratings yet

- Adams 2013Document9 pagesAdams 2013marcus souzaNo ratings yet

- The Management of Tennis ElbowDocument6 pagesThe Management of Tennis ElbowPutu OkaNo ratings yet

- ORIG Garrett1996 Muscle Strain InjuriesDocument8 pagesORIG Garrett1996 Muscle Strain InjuriesAlejandra Botero EscobarNo ratings yet

- Jurnal FleksibilitasDocument8 pagesJurnal FleksibilitasYudi HoeromadonNo ratings yet

- Aerobic Excercise CompleteDocument25 pagesAerobic Excercise CompleteWACHRISNo ratings yet

- Ijspt 12 1150 IliopsoasDocument13 pagesIjspt 12 1150 Iliopsoasnikhilmascarenhas07No ratings yet

- PNF Ombro 04Document10 pagesPNF Ombro 04Isaias AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- Hamstring Tendinopathy ASTYM PDFDocument5 pagesHamstring Tendinopathy ASTYM PDFNicolás Ayelef ParraguezNo ratings yet

- Nunes2020 (1) - 221113 - 142622Document10 pagesNunes2020 (1) - 221113 - 142622Black BeltNo ratings yet

- Does Stretch Training Induce Muscle Hypertrophy in Humans? A Review of The LiteratureDocument9 pagesDoes Stretch Training Induce Muscle Hypertrophy in Humans? A Review of The LiteratureDavid PucheNo ratings yet

- Medicine: The Effect of Lumbar Stabilization and Walking Exercises On Chronic Low Back PainDocument10 pagesMedicine: The Effect of Lumbar Stabilization and Walking Exercises On Chronic Low Back Painmatiinu matiinuNo ratings yet

- Peterson, 2012 PDFDocument1 pagePeterson, 2012 PDFPablo fernandezNo ratings yet

- Scientific Research Journal of India (SRJI) Vol-2 Issue-2 Year-2013Document71 pagesScientific Research Journal of India (SRJI) Vol-2 Issue-2 Year-2013Dr. Krishna N. SharmaNo ratings yet

- Beaulieu 1981Document9 pagesBeaulieu 1981degohe5609No ratings yet

- A 67-Year-Old Woman With Knee Pain CmajDocument4 pagesA 67-Year-Old Woman With Knee Pain CmajM.DalaniNo ratings yet

- Mike ReinoldDocument20 pagesMike ReinoldVikas Kashnia0% (1)

- Continued Sports Activity, Using A Pain - Monitoring Model, During Rehabilitation in Patients With Achilles TendinopathyDocument10 pagesContinued Sports Activity, Using A Pain - Monitoring Model, During Rehabilitation in Patients With Achilles TendinopathyMichele MarengoNo ratings yet

- Impact of Exercise On The Functional Capacity and Pain of Patients With Knee Osteoarthritis: A Randomized Clinical TrialDocument7 pagesImpact of Exercise On The Functional Capacity and Pain of Patients With Knee Osteoarthritis: A Randomized Clinical TrialSunithaNo ratings yet

- Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness (DOMS) in Athletes: Mechanisms, Prevention and Amelioration - A Critical ReviewDocument9 pagesDelayed Onset Muscle Soreness (DOMS) in Athletes: Mechanisms, Prevention and Amelioration - A Critical ReviewAlec NetheryNo ratings yet

- Giray 2019Document13 pagesGiray 2019Felix LoaizaNo ratings yet

- Levine - Rehabilitation After Total Hip and Knee ArthroplastyDocument6 pagesLevine - Rehabilitation After Total Hip and Knee Arthroplastyma_zinha_22No ratings yet

- The Role of Core Strengthening For Chronic Low Back Pain: Point/CounterpointDocument7 pagesThe Role of Core Strengthening For Chronic Low Back Pain: Point/CounterpointVictor Andrés Olivares IbarraNo ratings yet

- Sports Hernia and Athletic Pubalgia: Diagnosis and TreatmentFrom EverandSports Hernia and Athletic Pubalgia: Diagnosis and TreatmentDavid R. DiduchNo ratings yet

- Summary of True to Form: by Eric Goodman | Includes AnalysisFrom EverandSummary of True to Form: by Eric Goodman | Includes AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Hypothermia and Energy Conservation: A Tradeoff For Elderly Persons?Document11 pagesHypothermia and Energy Conservation: A Tradeoff For Elderly Persons?Xouya SuizenNo ratings yet

- Effects of An Energy Conservation Course On Fatigue Impact For Persons With Progressive Multiple SclerosisDocument9 pagesEffects of An Energy Conservation Course On Fatigue Impact For Persons With Progressive Multiple SclerosisXouya SuizenNo ratings yet

- The Effect of A Joint Protection Education Programme For People With Rheumatoid ArthritisDocument9 pagesThe Effect of A Joint Protection Education Programme For People With Rheumatoid ArthritisXouya SuizenNo ratings yet

- Rheumatoid ArthritisDocument19 pagesRheumatoid ArthritisElvisNo ratings yet

- Block H Proff 2021 by MMCDocument23 pagesBlock H Proff 2021 by MMCmuhammadshayan416No ratings yet

- Immunol Res, 60, 289-310Document5 pagesImmunol Res, 60, 289-310HAIDAR RACHMANNo ratings yet

- Question Quide Aswan - Med - Surg - 21Document41 pagesQuestion Quide Aswan - Med - Surg - 21Husseini ElghamryNo ratings yet

- Cyclosporine PDFDocument6 pagesCyclosporine PDFFazdrah AssyuaraNo ratings yet

- A Study On Subcutaneous Nodules in Rheumatoid ArthritisDocument20 pagesA Study On Subcutaneous Nodules in Rheumatoid ArthritisMinilik TimothyNo ratings yet

- Spondyloarthropathy OverviewDocument3 pagesSpondyloarthropathy Overviewagnes trianaNo ratings yet

- Braddom RheumatologyDocument22 pagesBraddom RheumatologynesNo ratings yet

- IM RheumatologyDocument56 pagesIM RheumatologySujoud AbuserdanehNo ratings yet

- Pharmacotherapeutics-II Question Bank 3rd Pharm DDocument11 pagesPharmacotherapeutics-II Question Bank 3rd Pharm DAnanda Vijayasarathy100% (3)

- Chapter 4. Approach To The Patient With ArthritisDocument16 pagesChapter 4. Approach To The Patient With ArthritisJose luis MendezNo ratings yet

- Rheumatoid ArthritisDocument29 pagesRheumatoid ArthritisvijitajayaminiNo ratings yet

- A Guide To ArthritisDocument12 pagesA Guide To ArthritisConsidraCareNo ratings yet

- Cardiovascular Disease in Rheumatoid Arthritis: Single-Center Hospital-Based Cohort Study in FranceDocument15 pagesCardiovascular Disease in Rheumatoid Arthritis: Single-Center Hospital-Based Cohort Study in Francemarisa isahNo ratings yet

- Approach To Case of ArthritisDocument53 pagesApproach To Case of ArthritisdrsarathmenonNo ratings yet

- ArthritisDocument69 pagesArthritisKavya sriNo ratings yet

- Rheumatoid HandDocument67 pagesRheumatoid HandSayantika DharNo ratings yet

- Approach To A Patient With PolyarthritisDocument29 pagesApproach To A Patient With PolyarthritisMd ImamuddinNo ratings yet

- Insider'S Guide Special Topic: The FDM Approach To Auto-Immune ConditionsDocument56 pagesInsider'S Guide Special Topic: The FDM Approach To Auto-Immune Conditionssam100% (1)

- Sample Test Questions: Krok 2Document41 pagesSample Test Questions: Krok 2kjkNo ratings yet

- Scale For Ranking Family Health Problems Accdg To PrioritiesDocument3 pagesScale For Ranking Family Health Problems Accdg To PrioritiesArthur Brian Panit100% (1)

- Rhelax RFDocument3 pagesRhelax RFcesiahdezNo ratings yet

- YOKDIL1 Ingilizce SaglikbilimDocument29 pagesYOKDIL1 Ingilizce SaglikbilimSüleyman DoğanNo ratings yet

- CS236 Homework Help 3Document4 pagesCS236 Homework Help 3Akun mobile LegendNo ratings yet

- Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (Jia) : IAP UG Teaching Slides 2015-16Document15 pagesJuvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (Jia) : IAP UG Teaching Slides 2015-16KathirNo ratings yet

- RF Latex Test Kit: Intended Use PrecautionsDocument2 pagesRF Latex Test Kit: Intended Use Precautionsces8bautistaNo ratings yet

- Rehabilitation in Rheumatic DiseasesDocument5 pagesRehabilitation in Rheumatic DiseasesShahbaz AhmedNo ratings yet

- RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS DR DON J SCOTT BERIN G BHMS (MEDICAL OFFICER) PDFDocument6 pagesRHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS DR DON J SCOTT BERIN G BHMS (MEDICAL OFFICER) PDFDr-Don JamesScott BerinGraceNo ratings yet