Professional Documents

Culture Documents

READING TASK Ier in The World

READING TASK Ier in The World

Uploaded by

Thu Thuy NguyenOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

READING TASK Ier in The World

READING TASK Ier in The World

Uploaded by

Thu Thuy NguyenCopyright:

Available Formats

READING TASK

The following passage is an excerpt from the article Interpreters to the world by

Lawrence Elliott, which will give you a better picture of the profession. Read the

text and answer the question on the screen.

Interpreters to the world

At a banquet in 1945, marking the end of a Second World War summit meeting in

Yalta, Stalin rose to propose a toast: "To those whose work is arduous indeed. We

rely on them to convey our every word, so that even tonight, as we relax and enjoy

ourselves they must labour on. Let us drink then to the interpreters. "

These days, as leaders of all nations come together more and more often to

strengthen ties or resolve differences, international spokesmen rely heavily on

expert linguists to transmit - often by simultaneous translation. Like electricity,

a good interpreter is never noticed unless something goes wrong. The pressure is

terrific. One diplomatic interpreter offered a wry description of himself as a man

with a ruined liver and worse nerves.

There are two dozen or so recognized interpreters' schools in Europe and America.

To be admitted to these schools, an applicant must hold a bachelor's degree and be

as proficient in at least two foreign languages as he is in his own. He also must be

equipped with a razor-sharp mind, split-second reactions, the temperament of a

cow and the stamina of a bull, for the two-to four-year course covers the whole

range of subjects, from art to zoology. In the practice class, the students are

bombarded with idioms, clichés, accents, slang and humour of the language, all

intended to make them respond automatically without wasting time mulling over

mere words. Interpretation is not a literal translation of the speaker's words. It is

the meaning that counts, as well as the art of conveying its impact. Delegates

listening to an impassioned orator are never surprised to note that the man in the

glass booth is thrashing his arms with equal fervor.

Nearly all interpreters subscribe to foreign periodicals in order to refresh their

language capability. Some specialize in highly technical fields and become near-

experts. The sole aim of this endless process of self-education is to put the

interpreter on roughly the same cultural level as the man he is translating for. "We

will never be able to perform a heart transplant, "says Miss Danica Seleskovitch,

who is in charge of the interpreter's school at the University of Paris, "but we must

certainly master the terminology well enough to explain it. "

Most interpreters agree that their really unsettling moments come when the

speaker makes a joke involving an untranslatable play on words. "There is hardly

anything people are more sensitive about than the jokes they tell, " Miss

Seleskovitch says, "and it is very uncomfortable for everyone when the speaker is

overcome with laughter at his own humour and everyone stares at him blankly. In

an extreme instance, she once solved this problem by quietly informing the

delegates. "The speaker has just made a pun which cannot be translated. Please

laugh. It would please him very much". To her enormous relief, they did.

It was not until the turn of the ce n t u r y that the interpreting art came into its own.

Previously, exchanges between nat ions were conducted by career diplomats, and

almost always in French. With the end of the F i r s t World War, heads of state and

heads of government met face to face at the peace conference in Versailles and

discovered they could communicate only with great difficulty. Conferences that

should have ended in hours dragged on for days.

Simultaneous translation changed all t hat . The speaker talks into a microphone

linked to a sound-proof booth just off the assembly r o o m floor. There the

interpreter speaking into a second microphone translates the speech for the benefit

of those who don't understand the original language, all of whom wear an ear-piece

no bigger than a hearing aid.

Inside the little booth, however, the atmosphere is invariably charged with tension,

and stress is usually most severe in the German booth. Since the verb comes last in

a German sentence, there is no way of anticipating what a speaker will say. If the

sentence is long and involved, there is no chance of understanding it until many

nerve-racking minutes have passed.

There are those who believe that the age-old problem of how best to translate the

thoughts of men from one language to another will yield to the magic of the

electronic age. In 1966, the US National Research Council published its findings

on the proficiency of translating machine that took ten years to build and cost 8

million pounds. It was, said the report, 21 percent slower than a skilled human.

You might also like

- Through the Language Glass: Why the World Looks Different in Other LanguagesFrom EverandThrough the Language Glass: Why the World Looks Different in Other LanguagesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (244)

- Kato Lomb BookDocument216 pagesKato Lomb BookDearAdlibs100% (2)

- Diary of An InterpreterDocument4 pagesDiary of An InterpreterGlupiFejzbuhNo ratings yet

- LgCont LgDeath (Thomason9)Document13 pagesLgCont LgDeath (Thomason9)Alex AlexNo ratings yet

- Interpreters As Diplomats PDFDocument6 pagesInterpreters As Diplomats PDFDennys Silva-ReisNo ratings yet

- EssayDocument3 pagesEssayDarya DyachkovaNo ratings yet

- Six Fragments of A Theory of Translation As Understanding: Wolfgang KubinDocument11 pagesSix Fragments of A Theory of Translation As Understanding: Wolfgang KubinjbagNo ratings yet

- Issues of UntranslatabilityDocument6 pagesIssues of UntranslatabilityIfrahNo ratings yet

- Polylingualism As Reality and Translation As MimesisDocument20 pagesPolylingualism As Reality and Translation As MimesisKarolina Krajewska100% (1)

- Literal Vs Liberal What Is A Faithful inDocument34 pagesLiteral Vs Liberal What Is A Faithful inMisarabbit NguyenNo ratings yet

- What Is Faithfull in InterpretationDocument34 pagesWhat Is Faithfull in InterpretationBárbara Carrión UrbisagásteguiNo ratings yet

- 232 Relay in TranslationDocument12 pages232 Relay in TranslationShaimaa MagdyNo ratings yet

- Chapter 18 TranslationDocument32 pagesChapter 18 TranslationDina AuliaNo ratings yet

- Baluk-Ulewiczowa, Teresa - Beyond Cognizance - Fields of Absolute Untranslatability PDFDocument10 pagesBaluk-Ulewiczowa, Teresa - Beyond Cognizance - Fields of Absolute Untranslatability PDFE WigmansNo ratings yet

- Conlang Exhibit Master File Text RevDocument73 pagesConlang Exhibit Master File Text RevBorja Rodríguez MelaraNo ratings yet

- A Linguistic Analysis of The Unequal Power Relationship Involved in Trasference of Texts From One Language To AnotherDocument10 pagesA Linguistic Analysis of The Unequal Power Relationship Involved in Trasference of Texts From One Language To AnotherGireesh Kumar K100% (1)

- Proverbs: Practical Work Difficulties in TranslationDocument18 pagesProverbs: Practical Work Difficulties in TranslationRocio MendigurenNo ratings yet

- The Art of Silence and Human Behaviour - Interdisciplinary Perspectives PDFDocument219 pagesThe Art of Silence and Human Behaviour - Interdisciplinary Perspectives PDFsudhir69No ratings yet

- Dancing on Ropes: Translators and the Balance of HistoryFrom EverandDancing on Ropes: Translators and the Balance of HistoryRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (1)

- Zamenhof. The Life, Works and Ideas of the Author of EsperantoFrom EverandZamenhof. The Life, Works and Ideas of the Author of EsperantoRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Different Types of InterpretingDocument3 pagesThe Different Types of InterpretingIntan IzzaNo ratings yet

- Quarterly Essay 52 Found in Translation: In Praise of a Plural WorldFrom EverandQuarterly Essay 52 Found in Translation: In Praise of a Plural WorldNo ratings yet

- Venuti How To Read TranslationDocument4 pagesVenuti How To Read Translationapi-25898869No ratings yet

- A Global LanguageDocument5 pagesA Global LanguagefthtlNo ratings yet

- Translation Today A Global ViewDocument20 pagesTranslation Today A Global Viewtocprashant1962No ratings yet

- Wells - Esperanto - A Joke or A Serious OptionDocument11 pagesWells - Esperanto - A Joke or A Serious Option191300No ratings yet

- Response Paper On Translation and Ideology: Roza Puspita/186332026Document5 pagesResponse Paper On Translation and Ideology: Roza Puspita/186332026Roza PuspitaNo ratings yet

- A Rose by Any Other NameDocument4 pagesA Rose by Any Other NameIleana CosanzeanaNo ratings yet

- The Problem of An International Auxiliary LanguageDocument174 pagesThe Problem of An International Auxiliary LanguageSlavica PetrovskaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document32 pagesChapter 1Lola VidalNo ratings yet

- Esperanto (the Universal Language): The Student's Complete Text Book; Containing Full Grammar, Exercises, Conversations, Commercial Letters, and Two VocabulariesFrom EverandEsperanto (the Universal Language): The Student's Complete Text Book; Containing Full Grammar, Exercises, Conversations, Commercial Letters, and Two VocabulariesNo ratings yet

- What Is Translation?: Unit A1Document12 pagesWhat Is Translation?: Unit A1Venere Di TellaNo ratings yet

- National and International Translation OrganisationsDocument18 pagesNational and International Translation Organisationsmariaum69No ratings yet

- Mehmet Özgü Aras-IMT108 Final Assignment PDFDocument6 pagesMehmet Özgü Aras-IMT108 Final Assignment PDFZımbırtı GadgetNo ratings yet

- Mary LP Translation Studies Forum Cultural TranslationDocument18 pagesMary LP Translation Studies Forum Cultural TranslationShalzzNo ratings yet

- Traduccion e InterpretacionDocument31 pagesTraduccion e InterpretacionPedro Mendoza100% (1)

- Uriel Weinreich - Languages in Contact - Findings and Problems (1968, Mouton Publishers) - Libgen - LiDocument161 pagesUriel Weinreich - Languages in Contact - Findings and Problems (1968, Mouton Publishers) - Libgen - LiTatiana B.No ratings yet

- Refraction - The PaperDocument17 pagesRefraction - The PaperDavid KatanNo ratings yet

- Culture, Lang, and TransDocument6 pagesCulture, Lang, and TranssalteneijiNo ratings yet

- To Be Translated or Not To BeDocument67 pagesTo Be Translated or Not To BeAlan SantosNo ratings yet

- A New Theory of Translation: 1. Introduction: The Wider ContextDocument14 pagesA New Theory of Translation: 1. Introduction: The Wider ContextYasemin S. ErdenNo ratings yet

- Claude Piron - Psychological Reactions To Esperanto (1994) - Libgen - LiDocument16 pagesClaude Piron - Psychological Reactions To Esperanto (1994) - Libgen - LirezghozNo ratings yet

- Would You Agree That The Writer and Translator Are Co-Authors of A Work Produced?Document3 pagesWould You Agree That The Writer and Translator Are Co-Authors of A Work Produced?Varshita RameshNo ratings yet

- Translation TheoryDocument2 pagesTranslation TheoryMalika KalykovaNo ratings yet

- Translation Lecture 1Document4 pagesTranslation Lecture 1Nour yahiaouiNo ratings yet

- Journal FourDocument32 pagesJournal FourScott Annett100% (1)

- Uwe Poerksen PLASTIC WORDS The Tyranny of A Modular LanguageDocument135 pagesUwe Poerksen PLASTIC WORDS The Tyranny of A Modular LanguageJaime TorresNo ratings yet

- 304 B (Except Iain Chambers & Shantha Ramakrishnan)Document24 pages304 B (Except Iain Chambers & Shantha Ramakrishnan)Ayushi S.100% (1)

- The Italian Translation of Alan Moore's " V For Vendetta ", A Short CommentDocument34 pagesThe Italian Translation of Alan Moore's " V For Vendetta ", A Short Commentvaleriozed83No ratings yet

- Theory of InterpretingDocument34 pagesTheory of InterpretingHồng NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Article: "Pragmatic Translation and Literalism" Peter NewmarkDocument12 pagesArticle: "Pragmatic Translation and Literalism" Peter NewmarkAtamnaHelloNo ratings yet

- Stanko Nick Use of Language in DiplomacyDocument10 pagesStanko Nick Use of Language in DiplomacyLiliaNo ratings yet

- Week 4Document24 pagesWeek 4detektifconnyNo ratings yet

- Polyglot How I Learn LanguagesDocument216 pagesPolyglot How I Learn Languagesmonamesoeur1088No ratings yet

- Interpreters as Diplomats: A Diplomatic History of the Role of Interpreters in World PoliticsFrom EverandInterpreters as Diplomats: A Diplomatic History of the Role of Interpreters in World PoliticsRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Lesson Plan: Kingdom of Cambodia Nation Religion KingDocument7 pagesLesson Plan: Kingdom of Cambodia Nation Religion KingSeyha PHORSNo ratings yet

- Alvin MDocument2 pagesAlvin MRunmel Emmanuel Ramal DampiosNo ratings yet

- NX ToollibraryDocument14 pagesNX ToollibrarypuneethudupiNo ratings yet

- 13 Roscoe Carson Madoc-Jones Narrative Social Work. Conversations Between Theory and Practice PDFDocument17 pages13 Roscoe Carson Madoc-Jones Narrative Social Work. Conversations Between Theory and Practice PDFMateo MateitoNo ratings yet

- The Intellectualization of Filipino - National Commission For Culture and The ArtsDocument5 pagesThe Intellectualization of Filipino - National Commission For Culture and The ArtsElaineManinangNo ratings yet

- The English Latin DictionaryDocument182 pagesThe English Latin DictionaryJOSELUIS HUIZARSANCHEZNo ratings yet

- Note Taking StrategiesDocument2 pagesNote Taking Strategiesq81188118No ratings yet

- Tamil Samayal - Ice Cream 30 VaritiesDocument20 pagesTamil Samayal - Ice Cream 30 VaritiesSakthivel67% (3)

- Devops Training 5 DaysDocument6 pagesDevops Training 5 Daysravindramca43382No ratings yet

- Rhetorical Analysis PrepDocument2 pagesRhetorical Analysis PrepMikeNo ratings yet

- Juliet - ScriptDocument95 pagesJuliet - ScriptElisa MustikaNo ratings yet

- Week 9Document47 pagesWeek 9kinsNo ratings yet

- Dream Variations by Langston HughesDocument2 pagesDream Variations by Langston HughesAkirajane De Guzman100% (1)

- Midterms Reviewer For Purposive CommunicationDocument11 pagesMidterms Reviewer For Purposive CommunicationMicah Danielle S. TORMONNo ratings yet

- Applied Geometry in SulbaSutrasDocument10 pagesApplied Geometry in SulbaSutraskzillaNo ratings yet

- MathDocument9 pagesMathbea sailNo ratings yet

- BỘ ĐỀ THI VAO 10 2018-2019 - 05Document4 pagesBỘ ĐỀ THI VAO 10 2018-2019 - 05Thanh Xuan LeNo ratings yet

- Poesia BiblicaDocument31 pagesPoesia BiblicaPavlMikaNo ratings yet

- Year 9 Pearson English - 20230613 - 0001Document98 pagesYear 9 Pearson English - 20230613 - 0001Alby FernandoNo ratings yet

- Class 7 - Representation of Geographical Features-2Document6 pagesClass 7 - Representation of Geographical Features-2editsnostalgeeNo ratings yet

- Simplified Approach To Oblique Triangles - LAW OF COSINES AND THE LAW OF SINESDocument10 pagesSimplified Approach To Oblique Triangles - LAW OF COSINES AND THE LAW OF SINESJacinto Jr Jamero100% (1)

- Genesis ManualDocument51 pagesGenesis Manual甘逸凱No ratings yet

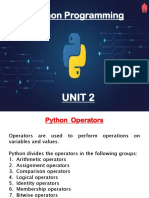

- MCA Python Programming Unit2Document58 pagesMCA Python Programming Unit2Kartik jainNo ratings yet

- Question Bank - Data StructuresDocument7 pagesQuestion Bank - Data StructuresRehan PathanNo ratings yet

- The Monsters of Paracelsus in Beasts HumDocument22 pagesThe Monsters of Paracelsus in Beasts HumMariam DavidoffNo ratings yet

- CH 2 Worksheet On Multiple IntegralDocument3 pagesCH 2 Worksheet On Multiple IntegralSuleiman AhmedNo ratings yet

- SONA Critical Review AssessmentDocument4 pagesSONA Critical Review AssessmentAlexandra MargineanuNo ratings yet

- Parallel and Distributed IrDocument33 pagesParallel and Distributed IrNnNo ratings yet

- Metaphysics An Introduction To Contemporary Debates and Their History 2019Document241 pagesMetaphysics An Introduction To Contemporary Debates and Their History 2019Eugene Salazar100% (1)

- Synopsis: Employee Management SystemDocument4 pagesSynopsis: Employee Management SystemIsurf CyberNo ratings yet